ABSTRACT

The rotating sutra-case cabinet is a wooden revolving bookshelf used for storing sutras in Buddhist temples, introduced from China into Japan during the Japanese medieval period. Besides the extant examples, specifications of sutra-case-cabinets can also be found in the architectural technic books of both countries, such as the Yingzao fashi (營造法式) of the Chinese Northern Song dynasty and the kiwari shō (木割書) of the Japanese Edo period. In this paper, the author discovers the design modules and dimensional plans of the rotating sutra-case cabinets by analyzing the specifications in the architectural technic books. The paper uncovers different methods used for designing the rotating sutra-case cabinets in China and Japan. A parallel constitution in dimensional plan is found in the Yingzao fashi, while in the Japanese kiwari shō the dimensional plans present a pyramid-shaped constitution. Furthermore, it is presumed that the differences between the Yingzao fashi and the kiwari shō are due to the editorial backgrounds and organizations.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The rotating sutra-case cabinet is a wooden, revolvable bookshelf used for storing scriptures in Buddhist temples. It is said that a celebrated layman named Fudashi (傅大士) from the Chinese Liang dynasty (A.D. 502–557) first invented the rotating sutra-case cabinet. The rotating sutra-case cabinet is not only used for storing books, but also as be equivalent to reading the Buddhist scriptures by revolving it. In this way, the common people, even without any knowledge of Buddhism, are supposed to be taught and blessed by the Buddha (Zhang Citation2000). Although used as a bookshelf, the rotating sutra-case cabinet also imitates the shape of the real carpentry architecture. Therefore, it serves not only as a kind of wooden furniture, but also an architectural model that is full of carpentry architectural elements. This makes the rotating sutra-case cabinet a special type among buildings in Buddhist temples.

The rotating sutra-case cabinet became extremely prevalent in the Chinese Song (AD 960–1279) and Yuan dynasties (AD 1271–1386) (Kanai Citation2008). It was introduced into Japan in the middle 13th century, along with the spread of Zen Buddhism and the printed Chinese Buddhist canon (Otuka Citation2013). Currently, examples of surviving rotating sutra-case cabinet exist in these two countries, with a total of around 10 in China, and around 130 in Japan (Yu and Koiwa Citation2017) ().

Figure 1. Examples of rotating sutra-case cabinet in China and Japan. (a) Zhuanlunzang of Longxing Temple (隆興寺) China; (b) Rinzō of Onjōji Temple (園城寺), Japan (Photo by author).

Besides the examples, records of the rotating sutra-case cabinets can also be found in the architectural technic books in both China and Japan, such as the Yingzao fashi (營造法式) of the Chinese Northern Song dynasty, and several books among the kiwari shō (木割書) of the Japanese Edo period ().

Table 1. Specifications of rotating sutra-case cabinet seen in Chinese and Japanese architectural technic books.

The rotating sutra-case cabinet has attracted the attention of both Chinese and Japanese scholars. Takejima (Citation1997) conducted a textual research on the full text of the Yingzao fashi, including the interpretation and the sketch restoration of the rotating sutra-case cabinet. Guo (Citation1999) examined the context of the rotating sutra-case cabinet provided by the Yingzao fashi, and introduced several typical examples of it in China and Japan. Zhang (Citation1999) conducted a comparative research on the rotating sutra-case cabinets of China and Japan and explained the origins, development and forms of the cabinets in these two countries. Chen (Citation2011) analyzed the specifications of the 6-type interior architectures in the Yingzao fashi and concluded that they are designed by the unit length of 100 fen。 – the length between the axes of the two intercolumnar brackets (Chen Citation2011).

However, many questions remain unanswered. On the one hand, although previous researchers have interpreted the specification in the Yingzao fashi, the analysis of design methods from the documentation has not been employed. On the other hand, the specifications in the Japanese architectural technic books have not received enough scholarly attention. Furthermore, in terms of the issue in comparing rotating sutra-case cabinets between China and Japan, the previous researches focused mostly on their shapes and styles, while the design methods of the miniature architecture have not been paid attention to.

This paper takes the architectural technic books as the research material to compare the design methods of the rotating sutra-case cabinets in China and Japan. A total of 15 books were collected, containing records of the rotating sutra-case cabinets from the open access Japanese kiwari shō. These books, along with the Yingzao fashi, were assigned as the materials to analyze the design methods of the rotating sutra-case cabinets in this paper (). It should be noted that there is a 6-century time span between the Yingzao fashi and kiwari shō and there is no solid evidence that proves any link between the two. The construction of rotating sutra-case cabinets reached its peak in the late Northern Song dynasty (end of the 11th century) in China and the middle Edo period (end of the 17th century) in Japan corresponding to the editions of the Yingzao fashi and kiwari shō. Therefore, the specifications for the rotating sutra-case cabinets in the Yingzao fashi and kiwari shō are possibly a result of their popularityFootnote1. Therefore, the comparison between the Yingzao fashi and kiwari shō is meaningful in understanding the uniqueness of the design methods especially when the rotating sutra-case cabinet was in its popular periods. Additionally, among the various kinds of miniature architectures, the rotating sutra-case cabinet is the only case recorded in both Chinese and Japanese architectural technic books. Therefore, the study of its design methods is also an important part of the study for the Sino-Japanese architectural technology exchange history.

The design rules of the rotating sutra-case cabinets were interpreted in the Chinese Yingzao fashi and the Japanese kiwari shō. Subsequently, the designing modules were illustrated from the design rules and summarized into design methods for the Chinese and Japanese cabinets. Furthermore, dimensional plans were discussed in order to figure out the logical association among all kinds of design methods in each book.

Comparisons between the Yingzao fashi and kiwari shō were subsequently conducted under the view of combining the analysis of the literature and design methods. Additionally, the design methods of the rotating sutra-case cabinets were also compared with those of the carpentry architectures in architectural technic books to identify the characteristics of the design methods of miniature architecture. The differences were assumed as a conclusion under the context of the comparative history.

2. Rotating sutra-case cabinets in the architectural technic books

In the Yingzao fashi, the design rules of the structure and dimensions of the rotating sutra-case cabinet are recorded in Chapter 11 (卷十一 小木作制度六 轉輪經藏), and an elevation is illustrated in Chapter 32 (卷三十二 小木作制度圖樣二十一 轉輪經藏).

Up to 100 components of the rotating sutra-case cabinet are measured out in the Yingzao fashi. According to the measurement in Chapter 11, the rotating sutra-case cabinet in Yingzao fashi consists of three parts: the outer-ring frame (waicao 外槽), the inner-ring frame (licao 裏槽), and the rotating wheel (zhuanlun 轉輪). People can only rotate the central wheel by opening the doors of the inner-ring frame since there is a separate structure for the interior wheel and the exterior frames. The items of components’ measurements are also listed according to the sequence mentioned above. Each item is defined by section and elevation. In each part, the exterior ornamental components are specified first, followed by the instruction of interior structural components ().

Figure 2. The Yingzao fashi’s “Zhuanlun jingzang” (Tao version). (a) Chapter11 “Zhuanlun jingzang” measurement text; (b) Chapter32 “Zhuanlun jingzang” illustration (Li Citation1954); (c) Structure of “Zhuanlun jingzang” (Illustrated by author).

The Shōmei and Shokishū are technic books written by the Heinouchi family (平内家), known as the carpenters of “Shitennōji School” (四天王寺流) (Kawata, Fumoto, and Naito Citation1990). Both books concern about the regulation of an octagonal rotating sutra-case cabinet that demonstrates the structure of double-rings with a seatFootnote2 ().

Figure 3. Rotating sutra-case cabinet in Shitennōji-School kiwari shō. (a) Shōmei (Owned by The University of Tokyo); (b) Shokishū (Owned by Seikadō Bunko); (c) Structure of rotating sutra-case cabinet in Shokishū (Illustrated by author).

The Shōmei only makes simple specifications that focus on the overall sizes and crucial components. However, the Shokishū records much more detailed specifications of the components by the sequence of the seat, the inner ring, and the outer ring.

The Kenninjiha kadenshō (建仁寺派家伝書) and Kōramuneyoshi denrai mokuroku (甲良宗賀伝来目録) are two typical technic books written by the carpenter family of Kōra (甲良家), known as the “Kenninji School” (建仁寺流)Footnote3. Up to 40 items are mentioned in the Kenninjiha kadenshō, containing the measurements of overall sizes and design rules for all kinds of components, providing the most detailed information regarding the rotating sutra-case cabinets within Japanese kiwari shō. The Kōramuneyoshi denrai mokuroku (甲良宗賀伝来目録) followed the text of the Kenninjiha kadenshō but added elevation and section drawings.

Two types of rotating sutra-case cabinets are recorded in these two books. One presents the same shape of the rotating sutra-case cabinets as in the Shōmei and Shokishū (), while the other one displays the shape of a single ring with an exposed central pillar ().

Figure 4. Two types of rotating sutra-case cabinets in Kenninji school kiwari shō. (a) Type I- with seat; (b) Type II- exposed central pillar (Kawada Citation1988, revised by author).

The Kashiwagike hidenshō(柏木家秘伝書) is a technic book written by the carpenter family of Kashiwagi, who served as the Kobushingata (小普請方)Footnote4 during the Edo period. The specifications of the rotating sutra-case cabinet in this book consist of drawings for section, elevation and plan, along with textual descriptions. The rotating sutra-case cabinet in Kashiwagike hidenshō also has double rings along the seat. The text mainly focuses on the scale dimensions, and mentions the bracket sets and rafters. The dimensions of the components are marked in the elevation and plan ().

Figure 5. The Kashiwagike Hidenshō’s “Rinzō.”(Owned by Takenaka Carpentry Tools Museum, revised by author).

The kiwari shō of Nakagawa Naomichi kiwarimonjō (中川直道木割文書) was written by Nakagawa Naomichi, who served as a part of the carpenter group of the Daitokuji temple (大徳寺), Kyoto. This book contains drawings of elevation, plan as well as textual description. The shape of single ring with a seat is seen in the cabinet. The appearance of the sketches closely resembles the rotating sutra-case cabinet of the Daitokuji temple (大徳寺). It is possible to consider that the records in this book were results of a measuring survey of the rotating sutra-case cabinet in Daidokuji temple ().

Figure 6. The Nakagawanaomichi Kiwarimonjo’s “Rinzō.”(a) The text; (b) The drawing of plan; (c) The drawing of section (Owned by Tokyo Metropolitan Library).

The Shodo no zu (諸堂之圖), Mongai jyunanashu (門外十七種), Shichidosaku hinagata dojidori (七堂作雛形同地取), and Tendai shinon shichido hinagata (天台真言七堂雛形) are four books written in the late Edo period but without any authorial information. The rotating sutra-case cabinets in these books are all recorded through section drawings, as well as design rules. Regarding the shapes, the Shodo no zu demonstrates a shape of double rings with an exposed central pillar, the Shichidosaku hinagata dojidori and Tendai shinon shichido hinagata demonstrate a shape of double rings with a seat, while the Mongai jyunanashu presents both shapes mentioned above ().

3. Design methods and dimensional plans for rotating sutra-case cabinets in architectural technic books

3.1. Design methods for rotating sutra-case cabinets in architectural technic books

Design rules for defining the position, dimensions, and styles of the components are analyzed according to the records in the technic books. Based on this, all kinds of design rules are summarized into the various types of design methods.

In the Yingzao fashi, four types of design methods are concluded in the rotating sutra-case cabinet specification: the height module, the pedal module, the cai-fen。 system, and fixed sizes.

The principal design method of the rotating sutra-case cabinet is the height module, which is defined through the following text:

“其名件廣厚,皆以逐層每尺之高積而為法” (The height and width of all components, are proportionally defined by the height of each layer).

The rotating sutra-case cabinet is separated into several structural units through elevation, called “layer” (層) in the text above. The dimensions of the components of each unit are provided using proportional coefficients. Therefore, the real sizes of the components are calculated by multiplying the unit’s height with the corresponding percentage. For instance, the outer ring pillar is defined as:

“帳身外槽柱長視高,廣四分六厘,厚四分.” (The outer ring pillar: height is equal to the body (帳身), width is 4 fen and 6 li, thickness is 4 fenFootnote5 )

Since the body height is recorded as 12 chi, the dimensions of the pillar are calculated as below:

The width of pillar: 12*0.046 = 0.552 chi

The thickness of pillar: 12*0.04 = 0.48 chi

This method is used in the specifications for all kinds of miniature architectures in the Yingzao fashi, such as the Fodaozhang (佛道帳), the Yajiaozhang (牙腳帳), the Jiujixiaozhang (九脊小帳) and so on, being the universal design method for the small-scale carpentry work part in this book.

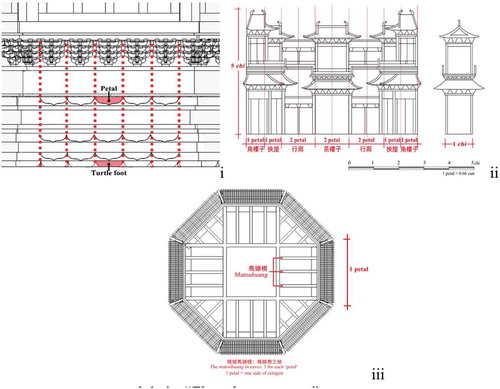

The second is the design method of petal (ban 瓣) module. The term “petal” originally represents the lotus petal-shaped ornament on the seat of the miniature architectures called the “Furong ban (芙蓉瓣).” The length of a petal set is 6.6 cun, which is used as the unit length to define certain dimensions. The petal module is mainly adopted in three ways. One is to align the turtle foot (guijiao龜腳) and the bracket sets on the elevation (). Another is to define the length of the celestial palaces (Tiangong louge 天宮樓閣) (). Besides, one side of the octagon is also termed petal in “Zhuanlun jingzang.” Here the petal is used to arrange the components inside the seat or eave by defining numbers of elements used within the space on one side (). Therefore, the petal can be recognized as one of character metaphorsFootnote6 used to define certain parts of the interior architectures in the Yingzao fashi.

Figure 8. The petal module in “Zhuanlun jingzang.”(a) Petal module used for aligning turtle foot and bracket set; (b) Petal module used for defining Tiangong louge; (c) Petal module used for arranging numbers (Illustrated by author).

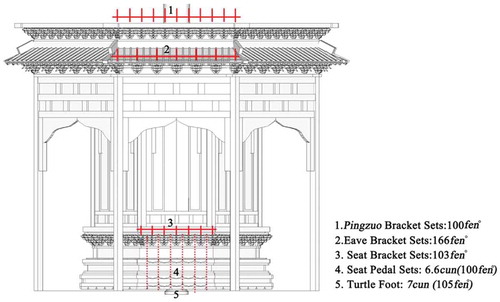

Third, is the cai-fen。 (材分) system. Being the most prominent design method among the carpentry works in the Yingzao fashi, it occurs only in the bracket sets’ specifications of the rotating sutra-case cabinet. The rotating sutra-case cabinet bracket sets use cai-fen。 of 1*0.66 cun for the main body, and 0.5*0.33 cun for the celestial palaces. It is already emphasized by Chen Tao that the length of 100 fen。 is used as a hidden unit length in the Yingzao fashi interior architectures (Chen Citation2011). In the case of the rotating sutra-case cabinet, 100 fenFootnote7 , with a length of 6.6 cun, is the same with the pedal set and the 1/10 of outer ring’s side length, indicating the relationship between the cai-fen。 system and other design methods. Furthermore, the intercolumnar bracket set (補間鋪作) are arranged at nine sets on the outer ring pingzuo (平坐), and five sets on the inner ring. The bracket sets’ intervals are calculated and found to be extremely close to the length of 100 fen。. Due to this, the intercolumnar bracket sets are arrayed densely on the elevation. Therefore, it is presumable that the 100 fen。 is used as a hidden design module ().

Certain kinds of components are regulated directly in fixed sizes such as the door and boards. It is difficult to calculate the proportional coefficients from the height as these components are so low in thickness. The sutra case placed in the wheel is also defined by fixed sizes.

Although differing from each other in content, the Japanese kiwari shō present similar characteristics in terms of design methods.

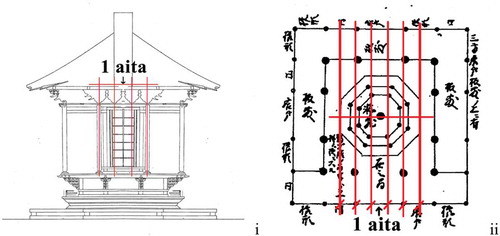

A typical feature of the design methods for the kiwari shō is that the items are defined from the whole to parts, where successive steps of proportional calculations are used. The diameter of the body is usually defined in the first sentence of the whole text, functioning as the most important dimension of the rotating sutra-case cabinet. The dimension of the octagon’s sides can thus be calculated from the body’s diameter. The pillar’s diameter often comes in after the body’s diameter, which is defined based on the side dimension (also the span of bay) by the proportional coefficient, using the presentation of the “bun kazoe (分算/分計).” Afterwards, various components of the rotating sutra-case cabinet are defined in proportional coefficients based on the column diameter.

Besides, several components are defined in fixed sizes, such as the roof slope and the sutra case. The aita (アイタ) module can also be found in the rotating sutra-case cabinet specifications, which is a unit length used to define the span of bay and combine the rafters and bracket sets in the dimensions for the Japanese Zen-style architectures (Kawada Citation1988). The aita module is found in the books of the Kenninji school kiwari shō and in the Kashiwagike hidenshō for the rotating sutra-case cabinet. In the Kenninjiha kadenshō, one set of aita equals 1/3 the length of an outer ring’s side that defines the arrangement of intercolumnar bracket sets ((a)). However, in the Kashiwagike hidenshō, the length of the cabinet’s eave edge is divided equally into five parts to define the aita, which controls the scale of the sutra hall ().

Figure 9. Design methods of the rotating sutra-case cabinet in Yingzao fashi (Illustrated by author, the celestial palaces are omitted).

Figure 10. Aita (アイタ) module in rotating sutra-case cabinet. (a) Kenninji school kiwari shō (Kawada Citation1988, revised by author); (b) Kashiwagike hidenshō (Owed by Takenaka Carpentry Tool Museum, revised by author).

3.2. Dimensional plans for the rotating sutra-case cabinets in architectural technic books

Dimension system diagramsFootnote8 are introduced to examine the characteristics of the dimensional plans for the rotating sutra-case cabinets in both the Yingzao fashi and kiwari shō texts. The items defined as fixed sizes form the first class in the diagram. The items defined by those in first class form the second class. The items defined by those in the second class form the third class, and so on and so forth ().

In the Yingzao fashi, the dimensions of the components are calculated proportionally, by the height of each layer. In other words, the dimensions of height serve as the matrix defining the components’ sizes in most cases. The connection between the height and the components’ sizes forms the main system of the dimensional plan. Besides, the pedal module and the cai-fen。 system also define the sizes of certain components, which form the sub-systems in the dimensional plan.

However, apart from the proportional relationship between heights and components, further proportional connections cannot be identified among the components. Thus, among the four design methods, merely two classes are separated in the conversion relationship (). Design methods in the Yingzao fashi present a planar graduation, although connections among design methods exist in certain circumstances (). Therefore, despite the large number of items, the dimensional plan in the Yingzao fashi is based on simple equations between matrixes (height and other design modules) and all kinds of dimensions, which presents a parallel relationship in constitution ().

The kiwari shō differ in specificity in terms of the contents of rotating sutra-case cabinets. However, they present similar organizations with regard to the dimensional plans. The dimension systems originated from the octagonal diameter in the Japanese kiwari shō as shown in . This is identified as the first class of the whole dimension system, serving as the matrix for other dimensions. The bay of side and the height of body are usually defined directly by the diameter, which composes the second class of the dimension system. The pillar diameter, hood of eave, and interval of bracket sets, are defined by the span of bay, which forms the third class in the dimension system. The dimensions of detail components are usually defined by the pillar diameter, forming the fourth class in the dimension systemFootnote9. Therefore, the specifications of the rotating sutra-case cabinets present the basic principles of the kiwari techniqueFootnote10 (木割術), which is common among the carpentry architectures in the kiwari shō. In addition, there are several specifications with fixed sizes in the kiwari shō apart from the four-class system above, such as the dimensions of the sutra case and the roof slope. Therefore, it needs three-times calculation from the body diameter to dimensions of components. A progressive graduation can be summarized with the sequence of “octagonal diameter-span of bay-pillar diameter-component dimensions,” presenting a vertical relationship among the design methods (). In conclusion, the dimensional system in the kiwari shō presents a pyramid-shaped constitution ().

Figure 13. Dimensional systems of kiwari shō (Illustrated by author)Footnote11 (a) Shōmei; (b) Shokishū; (c) Kenninjiha kadenshō- Type I; (d) Kenninjiha kadenshō- Type II; (e) Kashiwagike Hidenshō; (f) Ideal model.

4. Conclusion

According to the analysis above, the similarities and differences between the Yingzao fashi and kiwari shō can be summarized as follows.Footnote11

Concerning the specifications contents, the Yingzao fashi and kiwari shō can both be divided into three parts, records of the scale, components and the sutra case. However, in the Yingzao fashi, almost all the components are defined in three dimensions – length, width and thickness. This makes it feasible to restore the rotating sutra-case cabinet completely. On the contrary, in the kiwari shō, the components are merely defined in terms of dimensions in elevation, while the dimensions of sections are ignored. Moreover, the kiwari shō essentially focuses on the exterior components, but pretermits the specific descriptions regarding the frameworks underlying the roof and the interior rotating devices. Thereby, a complete restoration is inconceivable.

A noteworthy point in terms of category is that the Yingzao fashi’s “Zhuanlun jingzang” is attributed to the category of small-scale carpentry works (小木作), along with the fittings, the temporary wooden structures, and other types of miniature architectures. However, in the Japanese kiwari shō, the records of rotating sutra-case cabinet are attached to specifications of the sutra hall (経堂), which are arranged under the category of Buddhist architecture, distinguishable from the Jintō architecture, the domestic architecture.

Regarding the design methods mentioned in Chapter 3, the similarity between the Yingzao fashi and kiwari shō is the use of the design modules, basic unit and proportional method, other than defining the rotating sutra-case cabinets in real sizes. It is also interesting to find that similar presentations in proportional coefficients are used in the Yingzao fashi and kiwari shō. However, if compared to specifications for carpentry architectures, the height module used as the principal design method in the Yingzao fashi “Zhuanlun jingzang” cannot be found in the chapters of carpentry works, where the cai-fen。 system is the major method overwhelmingly used. Conversely, in the kiwari shō, methods of progressive proportional calculations and considering the pillar’s diameter as the basic unit, common in the specifications for rotating sutra-case cabinets, share the same characteristics as the carpentry architectures.

It is possible to make an assumption that the causes of the differences mentioned above are related to the editorial background and working organization.

The Yingzao fashi was identified to be a technic book edited by the Chinese Northern Song government. The book was edited with the aims of standardizing the building process and consolidating national control in terms of government policies and with the economical purposes of “providing sumptuary regulations for engineering agencies” (Guo Citation1998). Thus, Yingzao fashi was divided into chapters in terms of various architectural works, adapting the labours division in the central government.Footnote12

Carpenters in various regions were encouraged to learn the techniques from the Yingzao fashi, since the book was used for distributing the standard architectural techniques settled by the central government. The components of rotating sutra-case cabinet were recorded in extremely detailed items. Thereby, the local carpenters could build a rotating sutra-case cabinet referring to the book, without even seeing a real example. Moreover, if the distinction of the carpentry architectures is taken into consideration, it indicates that the specializations had been established between carpentry workers and small-scale carpentry workers in the late Northern Song dynasty.

On the other hand, the Japanese kiwari shō listed in are all manual books handed down through carpenter groups, known as kaden shō (家伝書). Thus, these architectural technic books were edited with the purposes of recording and summarizing the architectural techniques of a carpenter group, aiming at inheriting the group’s proud techniques from generation to generation.Footnote13 Under such circumstances, the kiwari shō books were written based on the carpenter’s rich experience in building practices and the memorandums were used as drafts in the edition (Naito Citation1960). The kiwari shō handed within the carpenter families only recorded the key points of design rules and building techniques, rather than be comprehensive records of architectures. Various types of structures were recorded in illustrative texts and sketches to enable the next generation carpenters to be accustomed to the family’s architectural techniques suggesting the cause of un-recreatability of the rotating sutra-case cabinet in the kiwari shō. Besides, concerning the labour division, it is conceivable that the carpentry work and small-scale carpentry work had not been separated when these kiwari shō were edited. In other words, the carpenter groups were responsible for both work. As a result, it is predictable that the carpenters perceived the rotating sutra-case cabinet to be subordinating to the sutra hall in terms of being helpful in gaining construction efficiency. Thereby, the rotating sutra-case cabinet was designed along the lines of the entire planning of a Buddhist temple, which explains the presence of the same design techniques between the rotating sutra-case cabinet and the carpentry structures.

Above all, according to a comparison between the Yingzao fashi and the kiwari shō, the design methods are clarified and characteristics of the design techniques are observed on the rotating sutra-case cabinets. It is also predictable that the discrepancies between the two lie in the differences of the editorial backgrounds and working organizations. Further consideration will be required to discuss the design methods and dimensional plans of the rotating sutra-case cabinet examples, and to compare those with the specifications in the architectural technic books of China and Japan. This will be helpful for gleaning an exhaustive understanding of the design techniques for the rotating sutra-case and identifying the uniqueness of the design methods of both countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Concerning the age distinction, construction of the rotating sutra-case cabinets in China was thought to become popular in the late Northern Song dynasty, and reached its peak during the Southern Song and Yuan dynasties. It declined dramatically during the Ming and Qing dynasties. In Japan, the rotating sutra-case cabinet was introduced at around the 13th century and the construction of it was under the management by the nobility and Samurai, before the Edo period. In the late 17th century, the rotating sutra-case cabinet swiftly spread and became popular. Despite the time difference, the popularity of the cabinet in both countries was related to the publication and spreading of Buddhist canon and the secularization of Buddhism (Yu and Koiwa Citation2017).

2 The rotating sutra-case cabinets in China and Japan was divided into three types. The first type involves a separate structure between the rotating wheel and the outside rings. The second demonstrates a unified shape with a seat that conceals the central pillar at the bottom, and the cabinet can be rotated entirely. The third demonstrates a unified shape but with the central pillar exposed on the outside. Both the second and third types can be divided into double and single ring phases (Yu and Koiwa Citation2017).

3 The carpentry family of Kora served as the Daitōryō (大棟梁) during the Tokugawa shogunate government. There are a series of architectural technic books that were edited by the family or show features of the Kora family’s design technique. Kawada Katsuhiro named the series of books the “Kenninji school kiwari shō” and divided the books into two types. One is the mainstay books, which are books with systematized content and written or edited by the Kora family members. The Kenninjiha kadenshō and Kōramuneyoshi denrai mokuroku are two books with the most specific records among the mainstay books. The other is the evolutional books, which are the books copied or edited under strong influence of the mainstay books, the architectural technic books listed as No.7~No.11 in all belong to the category of evolutional books. (Kawada Citation1988).

4 Kobushingata: A position under the Kobushingyō. Kobushingyō was one of the jobs offered during the Edo shogunate, responsible for the architectural projects during that period.

5 The fen here refers to the sub-unit of cun. The length of a fen is 1/10 of cun, and the length of a li is 1/10 of a fen.

6 Feng Jiren analysed the terms of the bracket sets and pointed out that there were botanic metaphors used to define the components, such as branches, flowers and petals. (Feng Citation2012).

7 The fen。 here refers to a basic unit length that is widely used in the Yingzao fashi. In the measurement of carpentry work, the cross section of the basic timber material has the ratio of 3:2, with 1 cai in height and 10 fen。 in width. 1 fen。 equals 1/10 of cai in size. There are 8 grades for the sizes of the cai that are used for various rankings of the buildings.

8 The dimension system diagram is a modern tool used for concluding and presenting the logical organization of the design rules in the architectural technic books. Ito Yotaro first used the tool early in 1949, to compare the dimensional plans between the various volumes in the Shōmei (Ito Citation1949). The dimension system diagram is drawn into the organization chart that focuses on the combination of the dimensions through specification texts, especially on the proportional relations between the dimensions of items. Nakagawa Takeshi developed the dimension system diagram by dividing the design methods in the kiwari shō into the main system and the sub-system. The main system refers to the design methods most used in a group of design rules, conversely, the rest of the design methods form the sub-systems (Nakagawa Citation1985).

9 It should be noted that not all the kiwari shō present the four-class system. For example, Shōmei only has a three-class system since there are no records for the components’ dimensions. On the other hand, the Kashiwagike hidenshō presents a five-class system since the components of the outer ring are defined by the outer pillar diameter which is determined by the inner pillar diameter. Nonetheless, an ideal model can be settled on as a four-class system to show the similarity within the kiwari shō.

10 Kiwari technique: A technique for measuring the components in a building. Usually the diameter of the pillar is taken as the basic unit, and the dimensions of the other components are calculated proportionally, from the basic unit. The technique was issued during the late medieval period, and was standardized in the Edo period.

11 The components’ dimensions include dimensions of nuki (貫penetrating tie beams), nageshi (長押non-penetrating tie beams), kasharanuki (頭貫head-penetrating tie beams), daiwa (台輪top plate), gagyo (丸桁eave purlin), en-ita (縁板floor board) and so on..

12 As is recorded in the government documents, the governmental construction ministry, Jiangzuojian (将作监), contained a department termed the Tijuzaijing Zhusikuwusi (提挙在京諸司庫務司) in the late Northern Song dynasty. Under this department, there were sub-departments such as the Tiju Xiuneisi (提挙修内司), the Bazuosi (八作司), the Tidian Xiuzaosi (提点修造司), and so on. Among these, the department of Bazuosi, which was responsible for the national architectural projects in the capital, was divided into sections such as stone work (石作), tile work (瓦作), mud work (泥作) and so on. Thus, the chapter division in the Yingzao fashi is supposed to be an adaptation due to the central government’s labors division, since Li Jie (李誡) – who served as the head of Jiangzuojian – was responsible for this edition of the book.

13 For example, in the postscript of the Kenninjiha kadenshō, the words of “自祖及今代代令相傳者矣” (The architectural techniques, from the ancestor until now, should be transported to the later generations) are written to demonstrate the purpose of the book.

References

- Chen, T. 2011. “A Study on the Design Modulus of Shrines and Cabinets in Yingzao Fashi.” In Chinese Architectural History, edited by W. Guixiang, Vol. 4, 238–252. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press.

- Feng, J. 2012. Chinese Architecture and Metaphor: Song Culture in the Yingzao Fashi Building Manual. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Guo, Q. 1998. “Yingzao Fashi: Twelfth-Century Chinese Building Manual.” Architectural History 41: 1–13. doi:10.2307/1568644.

- Guo, Q. 1999. “The Architecture of Joinery: The Form and Construction of Rotating Sutra-Case Cabinets.” Architectural History 42: 96–109. doi:10.2307/1568706.

- Ito, Y. 1949. “Kiwari ni Tsuite no Kōsatu 1- Shōmei Gokan no Kakukan ni Okeru Kiwari Hōhō no Hikaku.” [Discussions to Kiwari 1- The Comparison for Kiwari Methods among Shōmei 5 Volume.] Nihon Kenchiku Gakkai Kenkyu Hōkō 4: 351–360.

- Kanai, N. 2008. “Sōdai Tenrinzō to Sono Shinkō.” [Rotating Sutra-Case Cabinets of Song Dynasty and its Religion.] The Historical Reports of Risshō University 104: 1–18.

- Kawada, K. 1988. Source Books of Japanese Architecture. Vol. 3. Kyoto: Dairyudo Shoten.

- Kawata, K., K. Fumoto, and A. Naito. 1990. “Bibliography and Composition on Mainstay Books in the Architectural Reference Books of Shitennoji School.” Journal of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Engineering (Transactions of AIJ) 412: 109–117. doi:10.3130/aijax.412.0_109.

- Li, J. 1954. Yingzao Fashi. Beijing: Commercial Press.

- Naito, A. 1960. “Daiku Gijutsushō Nitsuite.” [About the Carpenter Technique Manuals.] Kenchikushi Kenkyu 30: 1–5.

- Nakagawa, T. 1985. “Kiwari No Kenkyu.” [The Research on Kiwari.] PhD diss., Waseda University.

- Otuka, N. 2013. “Medieval Ages Temples and Shrines and the Rinzō: A Reception and Expansion of Chinese Culture.” In Studies in the Political & Social History of Medieval Japan: Bulletin of the Department of Japanese History Faculty of Letters, edited by Laboratory of Japanese History, Graduate School of Humanity and Sociology and Faculty of Letters, The University of Tokyo, 29–43. Tokyo: University of Tokyo.

- Takejima, T. 1997. Eizōhōshiki No Kenkyu [Research on Yingzao fashi]. Tokyo: Chūōkōronbijutsu Publishing.

- Yu, L., and M. Koiwa. 2017. “A Typological Study on RINZŌ of Japan and China –On the Base of Examples and Architectural Technic Books-.” Journal of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Engineering (Transactions of AIJ) 740: 2701–2711.

- Zhang, S. 1999. “Zhongri Fojiao Zhuanlun Jingzang De Yuanliu Yu Xingzhi.” [The Origin, Development and Form of Chinese and Japanese Zhuanlun Jingzang.] In Jianzhushi Lunwenji, edited by Z. Fuhe, Vol. 11, 60–71. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press.

- Zhang, Y. 2000. Fu Dashi Yanjiu [Research on Fudashi]. Chengdu: Bashu Publishing.