ABSTRACT

The Li Canal has a reach that extends from Huai’an to Yangzhou, lying between the Yangtze River and Huaihe River. Moreover, this region divides China geographically and climatically into north and south. It can also be considered as an intersection where cultures from the north and south meet and integrate. Running through the north and south of China, the Grand Canal has become an important channel of cultural integration. Vernacular buildings aren’t an exception, as they are simultaneously affected by architectural styles from the north and south. This paper exhaustively studies the characteristics of the vernacular dwellings in the Li Canal reach across Huai’an and Yangzhou, from the perspective of layout, structural style and construction approach. Influenced by architectural cultures of the north and south, dwellings at both these places possess features of the north and south, and have created their own unique architectural styles. This paper attributes climatic conditions, customs, and regional culture as the fundamental reasons for these styles. Meanwhile, the paper further proves this conclusion by comparing features of vernacular dwellings in Huai’an and Yangzhou based on geographical nuances.

1. Introduction

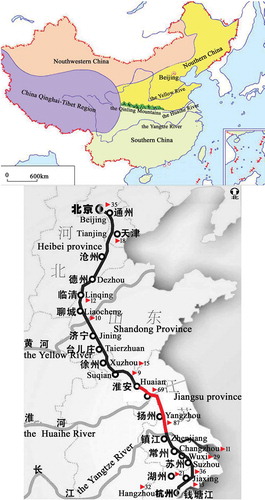

In 486 BC, King Fuchai, the Kingdom of Wu in ancient China, ordered a canal of approximately 300 li (150 km) to be built on the Hangou River to link it with the Yangtze River and Huaihe River. The Li Canal thus became the first artificial waterway of the world. As the longest and oldest man-made canal in the world, and the only north-to-south waterway across China, the Grand Canal, just like the Great Wall, is an ancient Chinese engineering miracl (Zhao. Citation2013). On June 22nd, 2014, the Grand Canal was listed by UNESCO as one of the World Cultural Heritage Sites, becoming the first “Existing and Linear Cultural Heritage” still in use in China. Extending from Beijing in the north to Hangzhou in the south, the 1,794 km long canal stretches across six provinces and two municipalities, and links five water systems – the Haihe River, the Yellow River, the Huaihe River, the Yangtze River, and the Qiantang River. As the first section of the Grand Canal, the 190 km long Li Canal links the Huaihe River and Yangtze River. It flows to Yangtze through Qingjiang Pu at Huai’an and

Guazhou Ancient Ferry at Yangzhou. Both cities are located in Jiangsu Province.

The Grand Canal fueled the riverside economy while also impacting the cultural heritage. The Grand Canal was the main artery, as well as the most important waterway connecting north and south in ancient China. Numerous historical and cultural heritage sites are dotted along the Canal, proving that the Canal lived up to its true name, the cultural corridor of ancient China. Along the culture corridor, Huai’an and Yangzhou are the shining stars. The Li Canal runs through the bustling old downtown areas of Huai’an and Yangzhou, where cultures from the north and south intersect, rendering these places with the most number of cultural achievements, and the most number of cultural relics and sites. Historically, Huai’an and Yangzhou along with Suzhou and Hangzhou were the Four Greatest Riverside Cities. From the birth of the Grand Canal, both cities shared the same fate as the Canal with which they came into being, they prospered and then eventually declined.

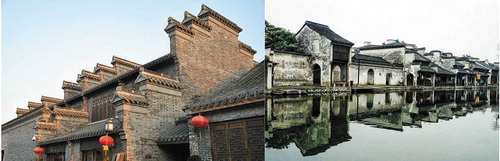

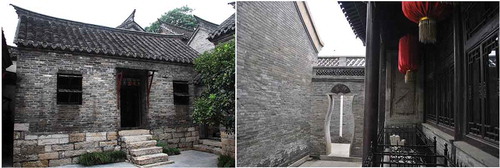

For more than 2,500 years, through Huai’an and Yangzhou, the Li Canal promoted culture exchange across the Yangtze River. Both cities developed their own unique regional culture thanks to the cultural interpenetration between the north and south. This has resulted in numerous vintage towns with rich cultural features along the Canal(Zhang and Liu Citation2008). In ancient China, Yangzhou and Huai’an had once been the water transport hubs for grain and salt. Traders from all over China established themselves in Xincheng in Yangzhou, and Hexia in Huai’an. They were eager to live here, and built fine and elegant private courtyards, and splendid houses in keeping with the times. As a result, they left tremendously valuable cultural heritage for both towns. Traditional vernacular dwellings in Huai’an and Yangzhou are all built with gray bricks, have gray-tiled roofs, are simple and functional, and are characterized by the firmness of the north and delicate elegance of Jiangnan (south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River) (). Professor Chen Congzhou concludes, “The residential architectural style of Yangzhou highlights its clean lines, even as it is comfortably wedged between the north and south (Chen Citation1978) .”

Different climates and regional cultures brought about great differences in vernacular dwellings in the north and south in terms of layout, structural form, construction approaches and facade styles. However, as a part of traditional Chinese houses, dwellings whether from the north or south interpenetrate and interact. All these can be clearly seen along the Grand Canal from the north to the south, particularly at Huai’an and Yangzhou, the interface of the north and south cultures.

This paper mainly discusses architectural features of riverside residential buildings by studying the existing residential buildings in the banks of the Li Canal, and investigating their layouts, structures and characteristics. The focus will be on the role they played in the transition process of the north and south style, and the unique style displayed by traditional residential buildings in Huai’an and Yangzhou.

2. Regional analysis

Due to the vast territory in China, the climates in the north and south are very different. The Yangtze River is typically considered the dividing line between North China and South China. In fact, the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River Line is the geographical line that divides Mainland China into the north and south. This line also serves as the demarcation for climate, rainfed agriculture and irrigated agriculture. Huai’an enjoys the benefits of the Huaihe River running through its hinterland, and Yangzhou lies just on the north bank of the Yangtze River. Located between the Yangtze and Huaihe, both cities stand on the line demarcating North China and South China ().

The flow waters of the Grand Canal are also responsible for the exchange of various cultures. Such exchange required Huai’an and Yangzhou – the waterway hubs, to be open to various cultures. The openness ensured that the culture around the Li Canal was simultaneously affected by North China and South China. This favorable geographic position contributed greatly to the unique architectural style and culture in the Li Canal reach. Traditional dwelling styles from the north and south interacted through the canal. As the Li Canal is located at the transition zone between the north and south, the architectural styles of this area were simultaneously affected by both sides. This formed a buffer zone, and acted as a connecting link between the north and south.

3. Research methods and case distribution

Feudal customs, climate and regional culture play a decisive role on layout, function, structure and construction of vernacular dwellings. As a result of the long history of being ruled by a central authority, most buildings in China have been influenced by the same feudal customs. As the Huaihe River and Yangtze River are the geographical and climatic dividing lines of north-south China, this paper divides the Grand Canal into three segments – the Li Canal reach (stretching between Huaihe River and Yangtze River), the north segment of the Canal (north of Huaihe River), and the Jiangnan Canal segment (south of Yangtze River). Totally, 397 cases of typical vernacular dwellings were selected in three parts,Footnote1 as the study subjects. Among them, there were 99 samples from the north segment, 156 from the Li Canal reach, and 142 from the Jiangnan segment (). Furthermore, another 76 cases were selected from south Zhejiang (South-East China) and South Anhui (East China) as control samples. These cases are distributed along both banks of the Grand Canal. The chosen dwellings were mainly constructed during the Qing Dynasty and the Republican Period. All selected cases were investigated by field works.

The law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of Cultural Relics stipulates that unmovable cultural relics, that is, historic relics, are divided into three levels in accordance with their historical, artistic and scientific values, namely,the national key cultural relic protection units, the provincial cultural relic protection units,and the municipal/county cultural relic protection units. The protection levels of selected dwelling houses are from higher to lower levels. And most studied cases in the paper belong to provincial levels or above, and the preservation is better. Only a few cases don’t fall under the cultural relics protection units, so it can be reckoned that these picked up are representatives of typical local houses.Even though the selected vernacular dwellings are limited in number, they are typical and can still be regarded as representative of local houses.

The main research method of this paper is on the basis of field investigation, using literature research method, analytical method, multidisciplinary intersection method, quantitative and qualitative analytical method, and comparative research method, among which field investigation and comparative study are the most important research methods.

4. The grand canal and cities in the Li Canal reach

Water played an important role in the formation and development of ancient Chinese cities. Ancient city sites were selected based on proximity to water, and they were constructed to facilitate urban transport, defense and water supply for production and living. Hence, ancient Chinese cities are almost all close to places with well-developed water systems. Lying between the Yangtze River and Huaihe River, Huai’an and Yangzhou boast strong geographic advantages, and are with brimming rivers and lakes. These not only helped in creating a canal system, but also provided a key basis for the future development of the Grand Canal. The development of the Grand Canal is inextricably bound to the evolution of riverside cities.

Since its completion, the Grand Canal played an important role in politics and economy. Grain and salt were transported by the Canal to the capital in feudal times, laying a solid foundation for the political and economic roles of Huai’an and Yangzhou, turning both cities into not just regional economic centers, but also transfer hubs for grain and salt from Huai’an. A colorful Huaiyang culture emerged, thanks to the flourishing business and prosperity. The unobstructed Grand Canal was fundamental towards propping up the development of Huai’an and Yangzhou. Towards the late Qing Dynasty, grain began to be transported by ocean instead of by waterway transport, and this resulted in a rapid decline in both cities. This goes to prove the importance of the river to both cities (Yang Citation2015).

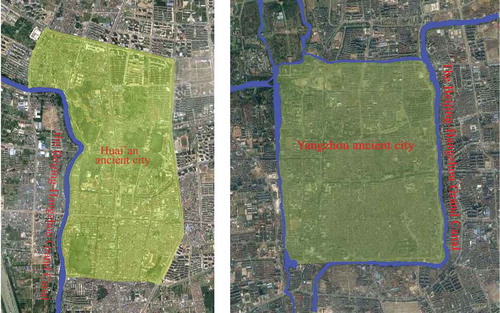

Huai’an and Yangzhou were the center of national water transport for grain and salt, and it was this culture that shaped the urban texture, and planning and future direction of both cities. The direction of the canal, aided the development direction of the towns. Thanks to the Grand Canal, the urban layout and development of Huai’an and Yangzhou were all along one side of the Canal, and not on both sides. The reason lies in the defense requirements of the cities, which used the Canal as natural moats for one or both sides (). Dwellings were built close but at a certain distance from the Canal. This was for two reasons. The first reason was flood control. The Grand Canal connected with other water systems, and one of the functions of each river was flood protection, and so it was with the Canal. The waterway was flanked with wide banks, and the buildings lay beyond the dikes. The second reason was safety. The primary function of the Grand Canal was the transport of grain and salt for the royal family. During the Qing Dynasty, Emperor Qianlong visited Jiangnan seven times, all by river. To maintain the safety of the vessels, dwellings were not allowed too close to the canal.

Various buildings were arranged along one side of the Canal. These buildings were meant to support the water transport of grain and salt, and met the demands of such transport to the maximum extent. Vernacular dwellings, guild halls, academies, courtyard buildings, etc., were meant for the physical and spiritual needs of the workers involved in the water transport. Shops, hotels, and waterway constructions such as ports, bridges and water gates were utilized by large numbers of grain and salt water transport workers. Government offices, tax offices, and post offices served the administrative authorities to handle the innumerable ships, boats, barges and other vehicles.

As water transport was risky, workers involved in the grain and salt water transport had high religious and spiritual requirements. They were constantly seeking ways to gain the blessings and protection of gods and goddesses. Therefore, a large number of religious buildings such as ancestral halls, temples and memorial archways, came up along the Canal in Huai’an and Yangzhou (Chen Citation2015). The existence of such buildings is the most profound reflection of the grain and salt water transport culture, and their remains are considered the most valuable heritage of water transport. The Grand Canal has a north-south orientation, and so is the case with traditional buildings in China. This is the reason most riverside dwellings don’t face the Canal although there are some exceptions. For example, there is a west-east channel at Huai’an, where buildings along the bank face the Canal, and their minimum distance from the river is merely 30 meters. These riverside buildings provided a variety of services for the people traversing between the north and the south.

As goods were shipped through the Canal, buildings serving grain and salt transport could not be too far from the Canal. Such a linear development restricted the spatial scale and dimensions of the cities. Furthermore, the water transport of grain and salt, brought with it innumerable merchants, ships, boats and vehicles, which helped create an economic boom and dense population in riverside towns and cities.

5. Block complex and courtyards

Traditional Chinese architecture uses supporting material such as timber, and its strength and length limited the height and span of buildings. This meant each building could not be too high (it had to be less than three stories). To make things worse, the number of bays (one bay referred to the space enclosed by four columns) in each building was also limited. Only royal buildings were allowed to be as wide as nine bays, while others were allowed just five or seven bays. Vernacular dwellings could be three bays wide at the most. This resulted in a smaller planar layout. This is a better explanation for the architectural complexes that were prevalent in traditional buildings in China, barring a few gardens embellished with isolated pavilions, terraces and towers, thereby leading to the emergence of one of the biggest features of traditional buildings in China – courtyards. A number of enclosed dwellings formed a courtyard, and a couple of courtyards constituted a building group, mostly along a north-south axis.

Any traditional dwelling group could be considered symmetrical along a central line, with main buildings located in the mean axis, and secondary buildings on both sides. Such architecture highlighted the left-right symmetry, clear-cut main buildings and secondary dwellings, and showcased good order. Hence, a multi-row configuration became viable. Larger-scale courtyards extended not only along the north-south axis, but also in the east-west direction, forming multi-axis courtyards (). The spatial layout of all traditional Chinese dwellings was centered around a courtyard. This practice created one of the most outstanding and charming characteristics of traditional Chinese buildings, and can be regarded as its most distinguishing difference from its western counterparts. Chinese dwellings valued groups, plane, and commonness or social aspects, while their western counterparts stressed on individuality, facade and uniqueness (Liu Citation2014).

5.1. Courtyards

In the transition from the north to south, there was an obvious change in courtyards. Such change starts from courtyards in the north to patio-typed courtyards in the south (). Such a change is deeply embodied in the vernacular dwellings at Huai’an and Yangzhou, as both these places are a transition area between the north and the south.

Northern residential dwellings have courtyards. Houses enclosing a courtyard were characterized by the fact that each building was separate, with or without corridors connecting them. As each building was disconnected, and as the wing rooms could not block the main rooms, almost the entire east-west length of the courtyard was bigger than the length of the main rooms. The aspect ratio of the entire yard was almost 1:1 ((Left)). Enclosed courtyards were much bigger and wider than their counterparts in the south. Residential houses in the south had courtyards, but each building was closely connected with overlapping roofs. (Middle, Right) indicate the close connectivity between the buildings. The reason for this difference is due to high latitude and cold winters in the north, where usually one-story dwellings needed more sunshine. Thus, in the north, courtyards were generally big and wide.

In the lower latitude south, summers are hot, so keeping away from sunshine becomes the main issue. Patio-typed courtyards were smaller and enclosed, and they curtained off the strong sunlight in the summer. In such a layout, the wing rooms connect the main rooms, and rooms in the west and east wings envelop the end rooms of the main rooms. This led to smaller, closed and more private courtyards. Such a layout ensured that the two end rooms of the main rooms, were not exposed to sunlight at all. Daylight and ventilation are essential for dwellings, but they were totally neglected. Due to lack of natural lighting, the two end rooms of the main rooms were dark, even during day time. To make matters worse, the windowless rooms had poor ventilation and resulted in foul smell.

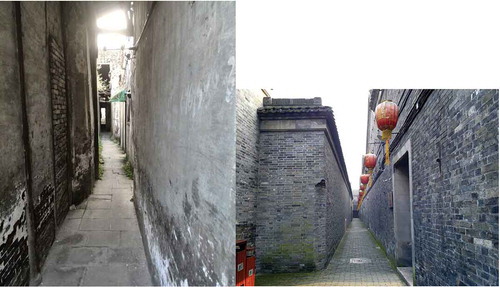

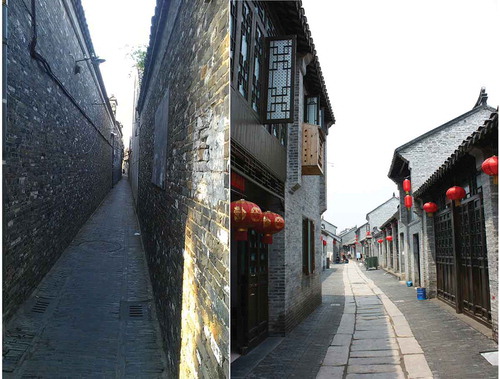

In patio-typed courtyards, dense dwellings were connected with each other, creating fire prevention and traffic problems between each axis. Such a layout directly led to creation alleys, which are called Huoxiang or fire lanes in Yangzhou, and Beinong in Suzhou (). These lanes acted as passages to any two axes of dwelling groups as well as to each row of a courtyard. They also connected different functional spaces of a courtyard. They connected front porches and living rooms in each row, through doors. Each row of the dwellings was separated by courtyards, while each axis of the buildings was linked by lanes.

Best cases of such a change can be seen both in Huai’an and Yangzhou. In all the study cases, only three are patio-typed courtyards in Huai’an, which is geographically closer to the north, and most are the same in the north, featuring disconnection between wing rooms and main rooms. On the contrary, most yards in Yangzhou are smaller-sized patio-typed courtyards. The climate in the Li Canal reach is characterized by hot summers, and wet and cold winters. This is why these two different styles of courtyards appeared in such areas. However, the reason why there is such a vast difference in courtyard proportion is due to their geographical location. Most of the merchants in Yangzhou, which is much closer to Jiangnan, were from Huizhou (an old region in Anhui Province, Southeast China). Hence, the styles of courtyards in this city were greatly influenced by Jiangnan culture, especially the vernacular dwellings of Huizhou. While construction practices at Huai’an were influenced more by vernacular dwellings from the north.

5.2. Plan

There was strict hierarchy in that a vernacular dwelling in the north consisted of three main rooms at the most, while side rooms could be added if the main rooms were insufficient. In vernacular dwellings in the South, the three-room layout prevailed. Such a layout characterized a connection between main rooms and wing rooms. In the main rooms, only the central one had natural lighting, while the two end rooms connecting the wings, did not. Occasionally, there would be a layout of five rooms with three facing the south and two connecting the wings. The main reason was that this layout ensured there was natural lighting for as many rooms as possible. Courtyards in Huai’an were influenced more by northern-style buildings. Most were one-story individual dwellings, and there were only a few two-story residential houses. Despite the number of stories, each individual dwelling was not connected, resulting in a wide courtyard.

In vernacular dwellingsin Yangzhou, wing rooms were connected to the main rooms, forming a patio. This kind of structure, where three main rooms connected to two wing rooms prevailed in Yangzhou. Individual buildings here had one or two stories. A number of these houses were enclosed, forming a patio. The enclosure ensured the buildings looked stronger than those in the north. The patios in Yangzhou were almost identical to the vernacular dwellings in Jiangnan, except, the former were much longer and wider. These characteristics made them look more like northern courtyards. ().

6. Façades and construction

Façades of vernacular dwellings in the Li Canal reach were influenced by both, the northern and southern architecture, but comparatively more from the south. Architectural appearance of traditional vernacular dwellings in the Li Canal reach were highlighted by their neatness and straight lines, as a result of the materials for the exterior walls and roofs, and the construction methodology. Most traditional vernacular dwellings in the Li Canal area were made of simple exterior walls, elegant gray rubbed bricks with firm joints, and gray tile-covered roofs. Such houses generally created an impression of a steel-gray hue, had a simple and solid appearance, and resembled stocky and serious northern vernacular dwellings (). The exterior walls of most vernacular dwellings in Jiangnan were coated with white lime, and roofed with gray-black tiles, leaving a fresh and elegant impression ().

6.1. Exterior walls

The most basic form of gabled walls in the Li Canal reach are Chinese gabled roofs, generally consisting of roof ridges, bargeboards of square bricks and walls. The shape of gables in vernacular dwellings in the Li Canal reach embodied more explicitly the integration of architectural styles of the north and south. The gabled roof was generally made with brick bargeboards, a typical northern practice (), while fireproof gable walls, fluctuating screen walls and Kwan-yin-dou (upside tuck-net shaped) gables are typical of southern style building practices ().

As southern dwellings were more densely arranged, the gables stood higher than the roofs to prevent fire spreading to neighboring houses. These gables are called fire gables. Fire gables of vernacular dwellings in the south had mainly horse-head walls (or corbie gables), wave-topped walls, and Kwan-yin-dou gables (). Such fire gables were neither present nor necessary for vernacular dwellings in the north, as households in the north were not directly linked, were not densely arranged, and only accessible via lanes. Corbie gables originated from the Huizhou region, while construction methods for fire protection walls in the Li Canal region greatly differed from the ones at Huizhou, but were similar to the ones at Jiangnan. Corbie gables are characterized by sedate and unsophisticated facades, and straight ends with squared fretwork or swastikas. Their lower parts were usually fixed with wooden-beam like rubbed-brick modeling, and their plain walls were not white washed. Corbie gables of vernacular dwellings in Huizhou were generally built in the shape of magpie tails and have slightly raised ends. The bargeboard heads, buttress heads and corners were all coated with white lime and decorated with frescoes.

The walls have a white finish coat, and they look graceful and elegant (Wang Citation2012) . This is a clear indication of regional culture differences (). These types of gable walls are typical in vernacular dwellings along the Li Canal, and became one of the characteristic features of Yangzhou dwellings due to their intensive use. Even when vernacular dwellings were dense in Huai’an, fire division walls were rare. In all the study cases, flush gable roofs prevailed. There were only a handful of other cases – one wave-topped gable, two corbie gables, and one Kwan-yin-dou gable. The main reason why fire division gables vary in Huai’an and Yangzhou is due to their geological locations. The former was influenced more by vernacular dwellings from the north as it is closer to the north, while the latter was influenced more by Jiangnan, as it is closer to the south.

Both the north and south have a couple of similar construction methods for exterior walls. However, rowlock cavity walls can only be found in the south, and not in the north. When rowlock cavity walls were built, bricks were placed at both sides, and sometimes broken bricks were stuffed in the hollow space. Please refer to . for the bricklaying method. From the point of modern architectural science, such walls highlight sound insulation, heat insulation and were economical due to their air-filled hollow layer. However, in the past, such knowledge was not known to the people of the cold northern area, where such walls were not prevalent. Rowlock cavity walls were widely used in the Li Canal reach.

Stucco is vulnerable to rain water, so the structural strength of the walls in the south is reduced during the rainy season. The exterior walls of the vernacular dwellings in Jiangnan were coated with lime as protection against rain. As the north is dry, all the walls were laid using plain bricks. The weather in the Li Canal area is almost identical to Jiangnan, however, all the vernacular dwellings there are plain brick-walled. It is obvious that the construction approach of exterior walls in the Li Canal area was greatly affected by the vernacular dwellings of the north.

6.2. Roof

It is cold in the north, hence roof of vernacular dwellings there was heavy. In such places, a layer of roof boarding or reed matting was laid on the rafters, followed by straw or mats, and finally there was a layer of plaster for the tiles. As it is hot in the south, roof of vernacular dwellings was light, and straw and mats were unnecessary. Furthermore, as timber is vulnerable to frequent rain, roof boarding was rare. Rafters were laid with sheathing tiles, which were then covered with roof tiles. In some vernacular dwellings, roof tiles were directly laid on rafters, without sheathing tiles. Such a change is clearly reflected in the vernacular dwellings in Huai’an and Yangzhou.

Vernacular dwellings in Yangzhou have rafters laid with sheathing tiles (sometimes substituted with reed mats under the influence of northern residential houses). Roof tiles here were laid without plaster. Similar to the plaster-applied concave tiles of the north, vernacular dwellings in Huai’an feature three-layer roof. First, the rafters were laid with roof boarding and sheathing tiles, then coated with plaster, and finally covered with roof tiles. In existing vernacular houses, the application of the two types of roof is almost proportional. Dwellings applying plaster under roof tiles may result in growth of weeds if they are in disrepair for a long time ().

6.3. Roof ridges

There were many construction methods for main . Ridges of hollow types. He Garden, Yangzhou ridges in the south. For example, one variation is to lay ridges with laminar tiles, then tier them with vertical ridge tiles ((a)). The two ends become upturned, looking like Aojian or turtle heads. In the case of Aojian, there are many variations as well (). A splitter wall built in the middle of the ridge tiles is called a Yaohua, a kind of brick carving. On the contrary, construction methods for main ridges were much simpler in the north, where bricks were piled. Such ridges are called tile and brick ridges. The main ridges highlight elephant-trunk-like ends, pantiles with simple modeling, Hunzhuan in the middle, and Watiao/Danggou at the bottom (Liu Citation2000) (). There are even cases without ridges. Ridges of vernacular dwellings are higher at the Li Canal reach. This is one of the most distinguishing traits from dwellings in other places. Ridges can be classified into solid and hollow types ().

Solid ridges of vernacular dwellings in Yangzhou are similar to the ones at Jiangnan and were formed by queuing vertical tiles closely, but having straight ridge ends with squared fretwork or swastikas (The ancient craftsmen called this style “ten thousand volumes of books”), and leaving notches in the middle. While solid ridges of vernacular dwellings in Huai’an were formed by queuing tilted ridge tiles loosely, having upturned ridge ends, and decorating with Yaohua in the middle (). At Huai’an, there are 51 cases of ridges decorated with Yaohua, however, Vernacular dwellings inYangzhou do not have Yaohua. Existing cases prove that construction approaches of ridges of vernacular dwellings in the Li Canal reach were affected more by the south than by the north, and developed their own style ().

7. Structures

Wood construction of traditional Chinese vernacular dwellings can be classified into three types – post and lintel construction, column and tie construction, and composite construction of the above two types. Vernacular dwellings in the north were all post and lintel constructions, and did not have column and tie construction, while all three constructions could be found in vernacular dwellings in the south. The column and tie construction and composite construction were dominant; the former was mainly used for bed rooms, and the latter for column-free halls, but their occurrence was rare ().

Column and tie construction was more economical thanks to less wood consumption. Another key reason lies in the hot summer and warm winter in the south. Thin wood siding walls or sandwich soil walls were applied to the interior wall connecting the column and tie construction and the columns, by using penetrating ties, which were used as an economical framework for the wood siding wall. Another highlight of the wood siding wall is its convenient disassembly. People from the south were considered to be so hospitable that they attached great impetus on customs, and would hold large-scale events in halls. In such cases, wood siding partitions ensured interior walls could be temporarily dismantled (). Many halls did not have partition walls, and the exterior walls were also wooden partition boards,They can also be removed when needed (). The north is cold, hence, the interior and exterior brick walls were thick. Some of the northern vernacular dwellings had thick sill walls in the lower part of the front façade, and the sill window was made at the top of the sill wall. The other facades were still thick brick walls (). This indicates that column and tie construction was not suitable for the north. Structural styles of vernacular dwellings at Huan’an and Yangzhou were similar to Jiangnan. Wood siding walls were used for most vernacular dwellings in Huai’an and Yangzhou, while sometimes sandwich soil partitions were also used ().

8. Conclusion

The Li Canal region is situated in the Lixiahe Plain. This is a place with the lowest average altitude in China, dense population, and centralized architectural layout. Close courtyards were arranged in an orderly manner. These courtyards were enclosed by streets and lanes, creating a neat impression (Lu and Yang Citation2004) . Most alleys were so narrow, winding and deep that only two to three people could pass side by side (). Vernacular dwellings in the Li Canal reach are all similar in terms of spatial planning, overall style, construction approaches and structural shapes.

By carefully analyzing the difference of vernacular dwellings inHuai’an and Yangzhou, it can be seen that buildings in both places are all deeply influenced by the north and south, and the development trends of traditional vernacular dwellings can be clearly delineated from the north to the south and vice versa. The most important difference in vernacular dwellings between the two places lies in the following three aspects: courtyard space, construction approach of the roof, and the type of gable. Traditional Chinese vernacular dwellings changed greatly from the south to the north (). Climate and regional culture played a decisive role in the change. While Huai’an and Yangzhou share almost the same climate and regional culture, geographical nuance contributed to the variation in architectural styles of the two places. More specifically, Huai’an, is geographically closer to the north, and was influenced more by northern architecture, while Yangzhou, is geographically closer to the south, and was influenced more by southern buildings.

Table 1. The differences between the south and north dwellings.

Most traditional vernacular dwellings in the Li Canal area were made of simple exterior walls, elegant gray rubbed bricks with firm joints, and gray tile-covered roofs. Such houses generally created an impression of a steel-gray hue, had a simple and solid appearance. Structural style of vernacular dwellings in both places coincides with their counterparts in Jiangnan, with main halls using post and lintel construction, while bedrooms use the column and tie construction and composite construction. The type of gables in Huai’an are almost identical to the walls in Yangzhou.

Vernacular dwellings in the south pursue coziness and privacy. In addition to the climate, houses in Yangzhou identify with their Jiangnan counterparts, with linked main rooms and wings, forming patios. However, the courtyards were bigger than northern dwellings. Most vernacular dwellings in Huai’an resemble northern houses, disconnecting main rooms and wing rooms. This ensured that the yards were more spacious. Such a scattered layout not only eased traffic, but also minimized fire hazards. On the contrary, the patio-typed layout is inconvenient for traffic and fire control. This led to creation of fire lanes in Yangzhou. Vernacular dwellings in Huai’an are similar to northern ones, highlighting heavy roof, upturned ridge ends, plastered roofs, and decorating with Yaohua in the middle, while houses in Yangzhou feature light roof, straight ridges, straight ridge ends with squared fretwork or swastikas, plaster-less roof, and leaving notches in the middle. The number and variations of existing fire proof gable walls in Huai’an are much less than Yangzhou. Most dwellings in Huai’an use flush gable roofs, the same as northern houses. Southern culture attaches more importance to customs. This influenced construction of interior walls in vernacular dwellings in the Li Canal reach. The interior walls here are all wood siding walls, resembling the practice followed in southern houses.

Keeping in mind the panoramic view of the flowing waters of the Grand Canal, the Li Canal played a transition role in introducing southern culture to the north, and northern culture to the south. Thanks to its unique geographical location, this placed played an irreplaceable role. This is the place where cultures from the north and south integrated, and then both cultures spread farther north and farther south. Architectural culture is no exception. Hence, traditional vernacular dwellings in the Li Canal reach are not only embodied by architectural styles of the south and the north, but also portray distinct regional cultures resulting from the shipment of grain and salt.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fei Qiao

Fei Qiao is an architect and urban planner. He has more than 18 years of teaching experience in architecture design and architectural history. Fei Qiao, PHD Candidate, Department of Architecture, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

Chih-Ming Shih

Chih-Ming Shih, Professor, Department of Architecture, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

Notes

1 397 cases of dwellings were studied in this paper;their locations and quantities are as follows:

- the north segment of the Grand Canal(99):Beijing 35, Tianjin 18, Linqing 12, Liaocheng 10,Xuzhou 15,Suqian 9

- the Li Canal reach(156):Huaian 69,Yangzhou 87

- the Jiangnan Canal segment (142):Changzhou 11,Wuxi 29, Suzhou 36,Huzhou 21,Jiaxing 13,Hangzhou 32.

References

- Chen, C.Z. 1978. “Yangzhou Gardens and Houses.” Social Science Front 3: 207-223.

- Chen, R. 2015. “Determination of Huai'an-Yangzhou Architectural Style and Cultural Value Cognition“. Planners 31(suppl.):280-284.

- Liu, S. 2014. Civilization of Construction -chinese Traditional Culture and Traditional Architecture. BeiJing:Tsinghua University Press.

- Liu, Z. P. 2000. Chinese Building Types and Structures. BeiJing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Lu, Y. D., and G. S. Yang. 2004. Vernacular Architecture. BeiJing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Wang, X. Q. 2012. A Comprehensive Research on Morphological Characteristics of the Architectural Heritage in the Old City of YangZhou. WuXi: Doctoral Dissertation of JiangNan University.

- Yang, J. H. 2015. Studies on the Evolutionary History of Yangzhou and Its Spatial Morphology in the Ming Qing Dynasties. Guangzhou: Doctoral Dissertation of South China University of Technology.

- Zhang, J. X., and Y. P. Liu. 2008. “Research on The Spatial Development Of Areas along The Beijing-hangzhou Canal.” Economic Geography 28 (1): 1-5.

- Zhao., P. F. 2013. Comprehensive Research on Traditional Buildings along the Shandong Canal. TianJin: Doctoral Dissertation of TianJin University.