ABSTRACT

Following the rapid pace of urbanisation, Chinese cities have launched a new wave of large-scale infrastructure, including cultural building construction. From 1998 to 2015, more than 360 grand theatres were built (or renovated) together with libraries, museums and children’s palaces. The number of newly built theatres may have been more than the total sum built in Europe over the past 70 years. No country in the world has built so many theatres in such a short time. To demystify the phenomenon, the authors have collected materials of all completed grand theatres in China, and compiled a database. Through analyzing the database, one can see the trend and characteristics of grand theatre design in China. The authors find that the rapid growth of cultural facilities epitomises the ambition and strong implementation of Chinese (and Asian) governments in the wave of urbanisation and globalisation. The research reveals the trend of constructing public buildings in Asia in the 21st century.

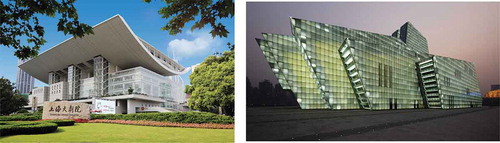

With the opening ceremony held on 27 August 1998, Shanghai Grand Theatre marked the beginning of a unique movement of theatre construction in China. Until 2018, the number of new theatres including new additions is 364, in which over 100 theatres are new constructions with an auditorium of 1,200 seats or more (Sun Citation2019).

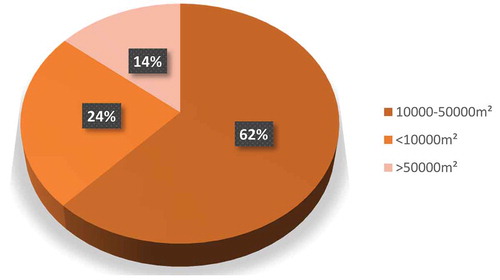

The Chinese name “grand theatre” (da ju yuan) first appeared at a performing art center in 1989 in Shenzhen, a special economic zone bordering Hong Kong. In 1994, an international design competition of “grand theatre” was held in Shanghai. Four years later a French designed theatre clad with crystal clear glass and flying roof monumentally stood at the People’s Square-the heart of Shanghai. The design of Shanghai “Grand Theatre” was selected through international design competition – its quality and image were well worth and admired as “grand” by people of Shanghai and China. Since then, grand theatres were planned and built in various Chinese cities, from coastal metropolis to provincial city, from prefecture city to rural town center. “Grand theatre” in this context is not only an auditorium. It usually contains an opera house, a concert hall and a multi-functional theatre. Most of these grand theatres have a gross floor area between 10,000 and 50,000 sq. m., and the total construction cost is about RMB 100 billion yuan (around 16 billion USD).Footnote1

Why and how have so many grand theatres been built so quickly in China? How were those designs selected in the process of decision making? What is the design language of the grand theatres? How do these theatres influence the ambience of a city, and how do they provide public space and amenities for a vibrant civic life? Cultural buildings are being busily constructed, cement, steel and materials are quickly consumed, but few serious studies have been carried on the heat of cultural building construction in China.

This article attempts to answer these questions by establishing a basic database, which will include all grand theatres built in China from 1998 to 2018. The authors are convinced that only by clearly grasping the facts of construction can one make further analyses on this phenomenon.

1. Literature review

Performing art is part of entertainment activities of the human being. Conventional study of theatre concentrates on theatrical technology, sightline and acoustics (Izenour Citation1996; Cheng Citation2015). After the 19th century, theatres have been built more for city’s pride, symbol and confidence. When Garnier’s opera house was built in Paris in 1861, it was a high-class venue of performance and social life. Its Baroque image was part of the Parisians’ pride (Cheng Citation2015).

In the 1950s, the city of New York cleared slum area in Manhattan and built Lincoln Center, with three high-end theatres, several concert halls and more than 70 museums and libraries nearby. This lifted New York from a financial center to a cultural metropolis. Sydney Opera House stood on Bennelong Point of Sydney Harbor in 1973, Utzon’s shell-shape design made it far more than a theatre for the city (Murray Citation2004). After that, municipal leaders and people began to learn how a cultural landmark had helped promoting the image of a city significantly. In France, President de Gaulle believed that bringing high culture to the masses would contribute to creating a more educated and productive society (Grenfell Citation2004). In the 1980s, Mitterrand’s state projects in Paris revitalized this economic and cultural capital of Europe. The old facilities were rebuilt, like the Louvre; and new facilities were constructed, like opera house in Bastille and the national library (Enright Citation2016). In 1997, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain greatly revitalized the originally derelict industrial town, population around 250,000, and attracted more than one million tourists annually, creating the so-called “Guggenheim effect” (Jencks Citation2004). In Asia, Singapore determined to become a Renaissance City or “global city for the arts”, creating a “saleable tourism product” on the one hand, while providing an “environment for living and working” on the other (Chang Citation2000). Cultural buildings and theatres have always been strongly tied with progression of urbanism and city status. Such cultural flagship projects and icons helped cities to create positive urban images, attract economic investment, develop their tourism sector and enhance their competitiveness (Kong, Ching, and Chou Citation2015; Klingmann Citation2007; Featherstone and Lash Citation1999; Short Citation2004; Owens Citation2013).

All those foreign landmarks, events and city spectacles have been inspiring China when the country got away from political turmoil and returned to normal life in the 1980s. Before 1980, the occasional performing art buildings were linked with power and Unitarian rules, for example, Great Hall of the People in Beijing and some provincial cities (Xue Citation2006, Citation2019; Xue and Ding Citation2018; Xue and Zhou Citation2007). The movement of constructing grand theatre in China is accompanied and fueled by continuous economic growth, rapid urbanization, new town construction and old town renewal. The newly built grand theatres in China may outnumber the sum of similar buildings constructed in Western hemisphere since World War II (Gates Citation2014). No other country has constructed so many grand theatres and cultural buildings in such a short period, which raises a number of issues of general concern, as listed in the previous session.

2. Methodology

What is “grand theatre”? In China, this term usually means a complex of performing art building with 2–3 halls. According to China’s building regulation issued by Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, a hall with 1200–1500 seats and more than 1500 seats can be categorized as large and extremely large-scale, respectively (Code for Design of Theatre Building JGJ 57 Citation2016). Therefore, we adopt this standard and collect a total of 104 cases. The cases are collected from project reports in professional journals, public media and relevant websites of cultural facilities. The authors have travelled to more than 10 major cities to investigate these theatres on site and interview the theatre management. Based on the materials collected, we further categorize and analyse in the following session, on the location of buildings, completion years, designers and design languages. The method is chart plus analysis. “Mosaic” in the title of this article means that descriptions are carried on from various facets, which globally compose a panorama of grand theatre construction.

Through the database, we can tell several aspects of grand theatres.

The distribution of grand theatres in China shows that some areas and cities will accommodate more cultural buildings and consumptions.

Distribution by completion year indicates how constructions fluctuate with years when China’s economic progress was relatively slow or fast.

Division by location shows where exactly these theatres are located in old city or new town, in high-density urban fabric or in landscaped area.

Distribution by scale shows usually how big the theatres are and what functions these theatres can undertake.

Who designed the buildings categorizes designers from China and abroad. This can indicate the dominant design force in China.

For foreign design firms, where are they from? This can further analyse the cultural origins of designers in a global market.

In design language, the authors try to tell the design method and strategies adopted to satisfy the clients’ demand.

Public space of theatres shows how the indoor/outdoor public spaces are used. We can see if the usage of public space realizes the design promise.

“Top designers” highlights design firms which have secured four or more theatre designs.

By looking into these nine aspects, we hope to delineate an urban and architectural perspective of grand theatres in China in the 21st century.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Distribution of grand theatres geographically in China

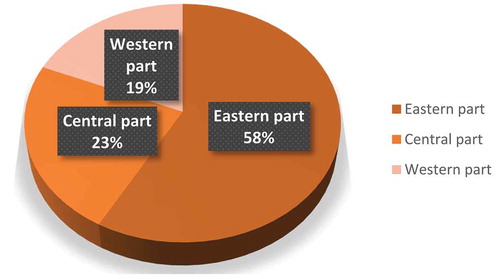

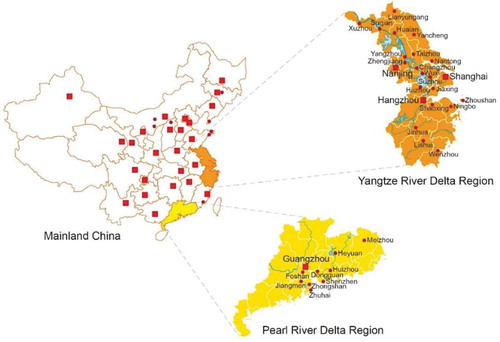

Geographically, China is divided into eastern, central and western parts. Eastern part is mainly coastal cities; central part is hinterland and the western part mainly made of mountain and desert. Population concentrates in the east and central parts, and immigrant trend is towards the coastal and southern cities.Grand theatre is part of the cultural facilities in city. It needs performers, cultural workers and audience (Bourdieu Citation1984). Only cities with sufficient population and money can feed the theatre (Ministry of Culture Citation2007). simply points out the disparities of grand theatre building between three parts of China. From , one can see that most of the grand theatres concentrated in coastal cities towards the east coast. Those parts with more theatres are obviously the richest in China. According to the statistics of 2018, the cities which have high ranking in GDP are Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Chongqing, Tianjin, Suzhou, Chengdu, Wuhan and Hangzhou (China Statistic Bureau Citation2019). Most prominent grand theatres are built in the top 20 cities of economic development. In Shanghai, there have been eight grand theatres which each possesses several halls, built since 1998. Beijing has various performing art venues for particular types, for example, Tianqiao Theatre for ballet and Capital Theatre for drama. More new cultural buildings are being planned or constructed in the city. After two rounds of cultural building construction, Shenzhen launched the third wave in 2018. More theatres and libraries will be built in the district level, but their scale and quality are not less than those in the municipal level. Pearl River Delta, or Great Bay Area, has major nine cities plus Hong Kong and Macau, with a population of 66 million. Each city has one or several grand theatres. Outside this Bay area, the other parts of Guangdong Province are quite poor and backward, not alone decent performing art buildings.

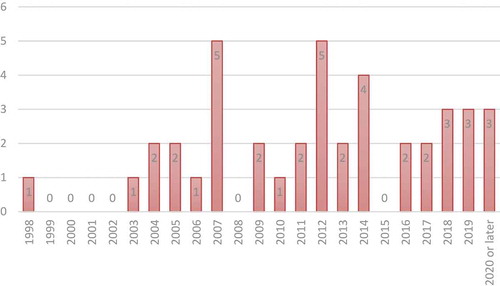

3.2. Distribution by completion years

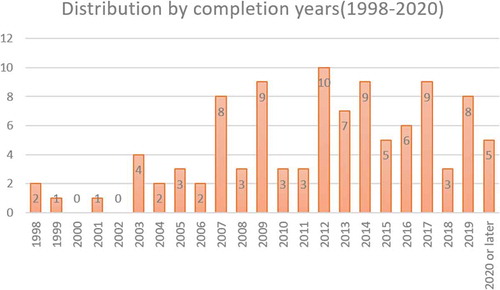

From , we can see that most number of grand theatres is completed in 2007–2019. A construction of building in this scale in China needs at least 3 years. China’s economic blueprint is made every 5 years. This is a legacy of the planned economy model, for example, 10th Five-year Plan is from 2001 to 2005 and 11th Five-year Plan from 2006 to 2010. After 20 years’ economic growth and entering the 21st century, China gradually got rid of poverty, and people in cities live in a well-to-do life. During this period, the economic planning of the country and provinces aims to “enhance the international competitiveness” and “improve the economy by encouraging people’s consumption.” Competitiveness includes soft power – high culture and art. Consumption consists of people’s education and cultural entertainment. This situation is similar to Singapore in the new millennium (Chang Citation2000). These forces push the demand for high-quality libraries, museums and grand theatres. By building these beautiful landmark buildings, the provincial and municipal leaders can demonstrate their achievements of leadership and climb up in career ladder. When city A builds such cultural facilities, city B in the same precinct will compete to build a better one, at least they will not lose face in this aspect. The competition among cities makes the construction tide even higher.From , we can see that 2012 sees most theatres completed. These theatres were usually prepared 4–5 years ago, around 2007–2008. That is the year of China’s running the Olympic Games. The whole country was heated by infrastructure reconstruction and new public buildings.

3.3. Division by location (old city or new town)

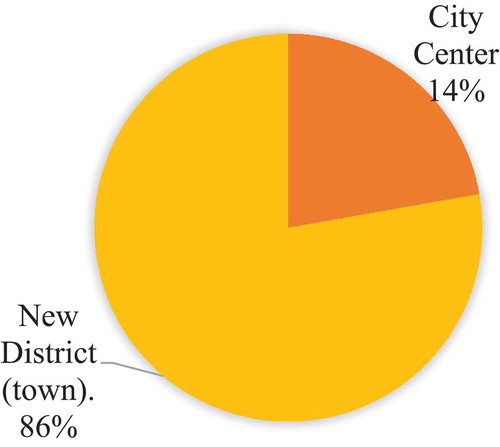

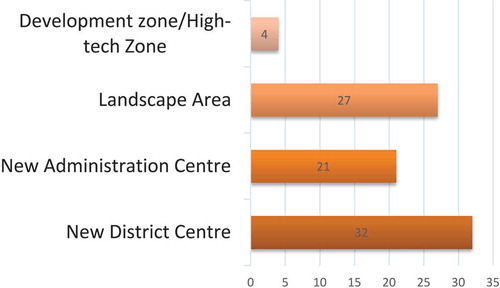

From , one can see that majority of grand theatres are built in new town. The old city areas enjoy easy public traffic and accessibility for most residents. However, it is usually difficult to find a land plot for grand theatre. Even one hall theatre needs a minimum site of 100 × 120 meter, not alone that most such theatres are closing to library, museum, and form the so-called “cultural district”, or “cultural cluster”. further indicates where these grand theatres stand. Of course, they are the brainchildren of municipal leaders, and naturally stand proudly in new district center, central business district (CBD) or administration center, like grand theatres in Hangzhou, Guangzhou, Taiyuan, Tianjin and Zhengzhou. If geographical conditions allow, they will be planned in landscape, particularly waterfront, so that reflection in water can better show the beautiful profile of cultural masterpieces, for example, theatres in Zhengzhou, Chongqing, Fuzhou and Wuxi. If there is no water, an artificial lake will be dug, like in Suzhou. The man-made waterscape is most profitable for land and property speculation ().

3.4. Distribution by scale

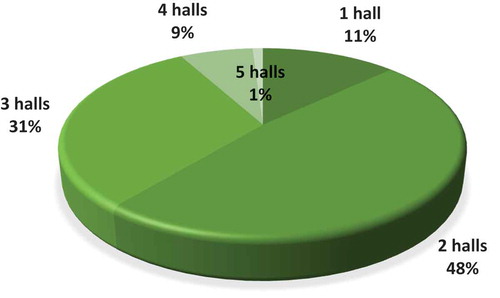

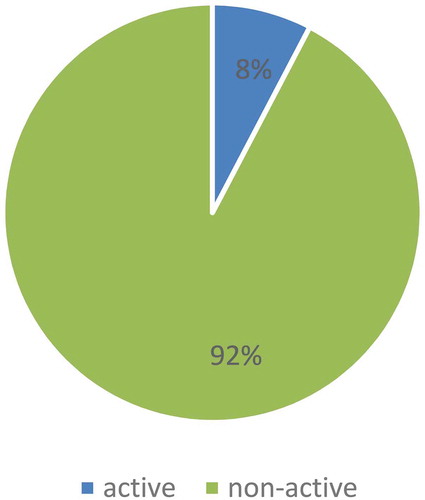

and are obtained from calculating 364 theatres completed during 1998–2015, the number includes newly built, added from the old structure and renovated. It shows that three quarters of theatres are larger than 10,000 sq.m. in gross floor area (GFA). A theatre of 10,000 sq.m. GFA can accommodate an auditorium of 1,200 seats, plus a small hall. Most provincial level grand theatres, which contain three halls, have a floor area of 50,000 sq.m. or more, for example, Oriental Art Center of Shanghai, Grand Theatres in Changsha and Jiangsu. further demonstrates that 80% grand theatres have 2–3 performing halls. According to our investigation, only theatres in the first-tier cities can have full capacity of performance. In many second or third-tier cities, 2–3 halls could hardly stage a performance in a month (Xue Citation2019). The Cultural Development Statistics Bulletin in 2016 published by the Ministry of Culture of the People’s Republic of China further reveals the problem. 1,265 performing venues, run by cultural departments at all levels, held overall 68.1 thousand performances in 2016, in other words, each venue only offered 54 performances a year on average. Compared with the normal performance level of around 200 a year, there is room for improvement. Unlike cities such as Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou and Shenzhen which see high cultural spending and commercial application, some small cities are working to achieve their primary goal, that is, letting residents know it is worthwhile to enjoy a show in theatres, and children should not cry during the performance. The low usage is a waste of tax-payers’ money.

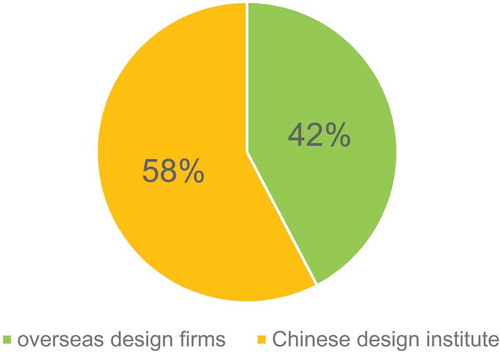

3.5. Pie of designers, China and foreign architects

In 104 grand theatres (performing arts center) newly built after 1998, 60 were designed by Chinese design institutes, and 44 by oversea design firms (). Since the running of international design competition in Shanghai Grand Theatre in 1998, almost all cultural landmark buildings open to the design competition (Xue Citation2010). This is the government regulation that any project of public fund must be got by bidding. The jury members are made mainly by Chinese architects and artists, with occasional international ones. The jury will usually recommend up to 2–3 schemes, and based on that, the client or government makes the final decision. In the shortlist of those design competitions, majority were international design firms from foreign countries. In some cities (for example Shenzhen), the government even regulates that the bidder must be a joint venture by Chinese and international firms.Encouraged by the client, the building forms and their symbolized meaning were highly emphasized, for example, the astonishing image of CCTV headquarters designed by OMA; “sun and moon” (convention center and grand theatre) in Hangzhou designed by Carlos Ott; and “two pebbles”- Guangzhou Opera designed by Zaha Hadid. This trend was especially obvious in the turn of the new millennium. The client and government treasure the projects and see them as an effective way to enhance the city’s branding and status. The metaphor “story” can be long lasting in media and mouth of public.

Facing the competition of international and starchitects, Chinese firms were inferior and had to act as local architects for documentation, submission and site supervision. They learnt a lot of experiences in this process. Under the fierce competition, Chinese architects could usually win in the third and fourth-tier cities. After 2010, a couple of Chinese firms had opportunity to win landmark design commitments in the second tier cities, for example, MAD’s design of Harbin Grand Theatre, DDB (Xiang Bingren)’s design of Hefei Grand Theatre and East China institute’s design of Jiangsu grand theatre. They are fast learning and growing individuals and firms.

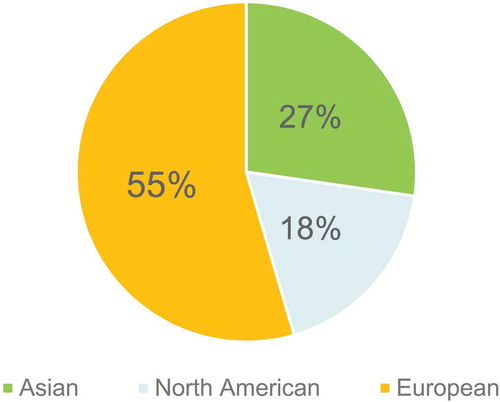

3.6. In foreign architectural firms, division by continents

In the 44 grand theatres designed by foreign architects, 12 are from Asian, 8 from North American (the US and Canada), and 24 from European countries (). Europe is the home of opera and symphony. Many famous operas and concert halls first appeared in European countries in the 19th century. The European architects swept up trophies in the first cohort of international competition in cultural landmark buildings. French architects won most of the design. In the psychology of Chinese people including municipal leaders, French is long associated with “romantic” and “artistic”. European, or more exactly, French design, is seen as a gift of high culture (Xiao, Wan, and Xue Citation2019). This psychology, to some extent, enabled French architects to display more in several coastal cities. Those foreign designers’ names appear in the theatre promotion pamphlets and media, and show the “internationalization” of the city and clients.Japanese architects entered China in the late 1970s together with Japanese investment and aid project. Japanese architects were successful in designing office, factory and hospital buildings. They are generally regarded to be precise, functional and economical (worth for money). In the first 10 years of grand theatre construction, very few Japanese architects won in the competition.

In these theatres designed by international architectural firms, some are well-known international starchitects, for example, Zaha Hadid, Tadao Ando and Isozaki Arata. The clients and municipal leaders are eager to lend their shining names, legendary designs and masterpieces. Other architects are either good in cultural building design or make their works known in China. Their design monographs were published in China and read by professionals and students. Their built works in China sent statements back to their home countries and strengthened their portfolios. Partly depending on these works in China, some designers gradually become “international” masters, like Paul Andreu, whom will be discussed later.

Actually, theatre design and construction will naturally involve many international consultants and suppliers, for example, auditorium and acoustic design, stage and lighting facilities. They contribute to the shinning of city’s cultural crowns in various angles. But in the age of icon and digital communication, general public is more interested in building form and legendary image (Xue and Zhou 2007).

shows the completion year of foreign architects’ design. It is basically compatible with the tendency in . When there are more theatres completed, more foreign architects are involved. It reflects that foreign architects are generally motivated in the 21st century, and the quantity of their designs keeps stable.

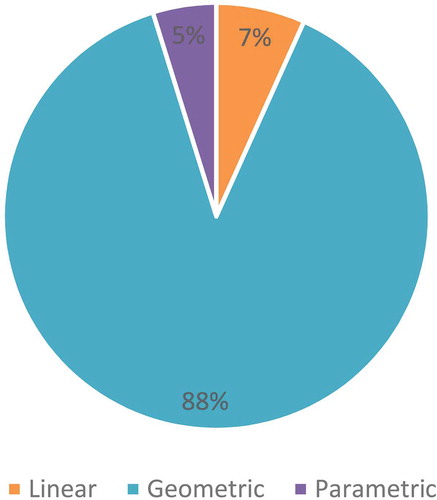

3.7. Division of design language (linear, geometric or radical)

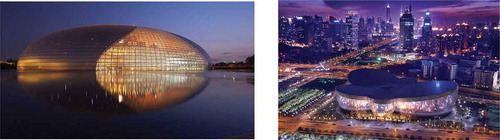

An architect design with his/her routine or strategic methodology, varied with situation and location. From the prevailing trend of design, we tentatively divide the design language as linear (orthogonal), geometric (circle, square and their combination in conventional drawing protocol) and parametric (or say radical). Linear form was prevailing in China in the 1980s, as the rectangular lobby, stage and side stage are most useful, economical and fitting into the city fabric. To break through the monotonous “match box” form, architects tried polygon, curvilinear forms and their combination. These combinations can be easily drawn by hand or conventional drawing tools/software (). Most construction companies are confident to build this kind of forms. However, radical form needs parametric design with special software. Some firms can skillfully grasp the techniques and produce drawings. However, manufacturing according to drawings of parametric design is still a bottleneck in China. The stone cladding in Guangzhou Opera House could hardly follow the subtle change of surface. The cost to build such buildings will be high ( and ).3.8. Public space of grand theatres: active and non-active

For a grand theatre building, government usually invested around a billion yuan RMB (around 160 USD million in 2018) for construction in the 21st century. In their operation, most theatres assume a self-reliant mode and run on incomes from box office and sponsorship, without government’s further subsidy. Those cultural buildings consolidated Chinese cities’ status in the region, province or even in the world. Can these buildings contribute to an active civic life of people?In our investigation, all new grand theatres’ designs have considered ample indoor and outdoor space for public activities. The lobbies are usually fabulously designed with flowing high-low space, curtain wall and high-class cladding materials on wall and floor. However, most of these indoor spaces only open an hour before the performance for ticket holders (). For example, Shanghai Grand Theatre often appears in postcard and leaflets of tourist information (Shanghai Grand Theatre Citation2017). However, an iron fence surrounds the outdoor grassland. Passers-by can only appreciate the crystalline sculpture-like theatre at a distance. Many residents in the surrounding areas never have a chance to enter the theatre. The management has explained that there are too many people in the square. If the theatre removes the fence, tourist buses will park in front and damage the pavement. Opening the lobby to the public is unthinkable.Footnote2 In Tianjin, the waterfront grand theatre seldom opens lobby unless in some important events. Even in performance days, audience members have to enter from side door, instead of waterfront grand gate.

The good examples are only seen in Shanghai Symphony Orchestra concert hall, which opens to the public their lobby and exhibition gallery, where musical instruments and interactive sound devices are displayed. The location is in the historic French concession area, where street life is lively and intimately taking place. In Suzhou Cultural and Art Center, the lobby is open, because art gallery, cinema and theatre share the same lobby.

The use of public space in China’s theatres contrasts sharply with the scenario in Hong Kong. For example, the Hong Kong Cultural Center, a complex with a concert hall, lyric theatre, studio theatre and exhibition gallery, was completed in 1989 and is much more modest than the fashionable grand theatres in the Chinese mainland. It hosts more than 600,000 guests per year (Hong Kong Cultural Centre Citation2017). Its lobby consists of a box office, waiting hall, coffee shop, toilets and an exhibition booth and links the commercial street to the Tsim Sha Tsui waterfront. From morning to midnight, it is open to the public and is always full of people chatting, waiting, enjoying free weekend performances, buying tickets and drinking coffee. The newly completed Xiqu (Chinese folk drama) Centre lifts the auditorium in above, the first three floors are open circular space, where cafe, restaurant, exhibition, seminar rooms are open to the public, and attract many people.

Compared to the huge investment they require, the magnificent space and prominent status they present in the city, and the citizens’ high expectations, Chinese theatres’ social functions need to be better and more fully displayed.

(9) The top designers: firms won four grand theatre projects each in China are as shown in .

Table 1. The most successful foreign firms in designing grand theatres in China

Among foreign architects’ firms, four have won most number of grand theatre projects: Paul Andreu from France, Carlos Ott from Canada, gmp from Germany and Isozaki Arata from Japan.

Paul Andreu (1938–2018) started his career from designing airport with adpi Paris. In 1998, his “duck egg” shape national grand theatre was appreciated and hand-picked by the top Chinese leaders. His following schemes of grand theatre and office/convention centers in other cities continued the route of symbolizing shape – arrayed petals of flower. Those shapes are beautiful and meaningful when looked from master plan and model, but people in eye-level can only feel bulky volumes. Many spaces are not well elaborated. In some buildings, he used metal net skin to clad the external wall. However, the dense metal net blocks sightline from inside. Outside China, Andreu designed a cultural pavilion in Japan. His most successful achievements were made in China (Andreu Citation2015). ()

Figure 3. Paul Andreu’s design – National grand theatre, Beijing, 2007 and Oriental Arts Center, Shanghai, 2005 (courtesy of Fu Xing)

Carlos Ott (1946-) made his debut in Bastille Opera in Paris in 1983, defeating the other 743 entries. Since then, he has gradually established his international portfolio by designing works in many countries. But only in China, he designed most number of grand theatres. His designs in China mostly use curvilinear or circular shape. This can, on one hand, add dynamics to the form and lobby part, and on the other hand, bring metaphor stories like “sun and moon”, “ballet dancer”, and “ancient musical instrument”. Ott’s designs recycled his earlier form and crafted new one for different sites. The attached stories are far-fetched, but can be imagined and spread. Ott’s design language is simple geometry, which could win in several cities in the first 10 years of building grand theatre. His design is easily learnt by China’s firms, and trains more competitors. In the second 10 years, parametric design replaced the simple geometry. Ott’s design had little chance to win ().

Figure 4. Carlos Ott’s design, Henan Arts Center, Zhengzhou, 2008; and Yulan Theatre, Dongguan, 2005

Isozaki Arata (1931-) participated the design competition of national theatre in Beijing in 1998, and entered the short list. His first built work in China is Shenzhen Cultural Center, which includes a concert hall and library, completed in 2008. Arata has been famous for his changing face/method since the 1970s and is categorised among the “post-modernists”. He has been active in China since the 1990s. After winning the first job in China – Shenzhen Cultural Center, he designed the art gallery for the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing (2008), Himalaya Center in Shanghai (2011), Shanghai Symphony Orchestra Concert Hall (2013) and Harbin Concert Hall (2016), and most of these works were implemented from his Shanghai studio organised by his partner Hu Qian. His postmodernist method appeals to the clients’ eagerness of creating a new image. In Shenzhen Cultural Center, he designed “golden tree” for the lobby of concert hall, and “silver tree” for library. However, the complicated shape of skylight suffers from frequent rain water leakage.Footnote3 Arata continuously explores the relationship of building, material, technology and context. In designing concert hall, he highly respected the expertise of structural, mechanical engineers and acoustic consultants. This rational spirit has moved many clients and made high quality works ().

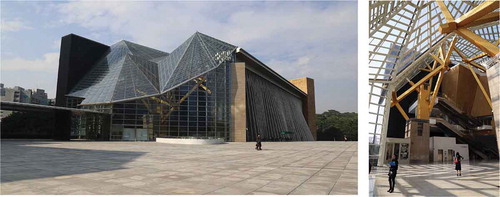

gmp began their design works in Berlin and Hamburg in 1965. Firmly believing in “simplicity, structural order, diversity and unity, and distinctiveness”, gmp never pursues any fashionable trend, but keeps their own design philosophy. Their uniqueness comes from simplicity and skilful structure. In several design competitions with architects who were fond of radical form, gmp won with its linear form grand theatre in Chongqing, Qingdao, Tianjin and Nanning. Made by delicate material details and streamlined connections, the linear form contains order, space, volume, opening, air and natural light. No matter in the sculpture location or sitting together with other buildings, gmp pays high attention on the city context. In addition to four grand theatres, more than 150 buildings designed by gmp were completed in China in the 21st century, including high-speed train stations, national museum, stadiums and office towers. It is arguably the most successful foreign design firm in China. gmp’s success demonstrates that when a radical form can usually attract most of the attentions, a well-designed linear form, with consideration of city context, has its own life and charisma to convince the decision-makers and public ().

4. Conclusion

Chinese cities are experiencing an unprecedented tide of urban construction, including cultural mega-structures (Lu et al. Citation2019). Grand theatre is one type of the cultural mega-structure, and jewel in the crown of the cities. No other country in the world has built so many cultural mega-structures in such a short period. In the modernisation process, these cities have always followed the experiences of emerging advanced cities, like Singapore and Sydney, to prioritize from hardware to the software by creating spectacle images.

This article briefly scans 364 theatres (built or remodeled), particularly 104 new “grand theatres”, during 1998–2018. Comprehensive thinking about the situations of various cities in Mainland China, the construction of grand theatres has begun to take shape, the depth and breadth of the construction, reflecting China’s regional economic development level and the level of opening, as well as mapping out the degree of spiritual civilization and people’s living standards in different regions (Shen et al. Citation2016). However, rapid construction without theoretical guidance has exposed a lot of problems. Through analyzing the database, we can see that cultural buildings are densely built in the east and coastal cities, this phenomenon is highly compatible with the development level of provinces and cities in China. Years 2007–2018 saw most of the buildings completed, as in the 21st century, Chinese cities are more aware of the importance of cultural buildings in the global and national economic competitions. Huge capitals are pumped into the urbanization process for cultural buildings and facilities, especially for grand theaters (performing art center.) The fast-growing economy raised people’s living standards, and entertainment consumption demands more on performing art and cultural space.

To build large scale cultural buildings and clusters, cities have to find central locations in new towns, as the cultural facilities best demonstrate the city’s soft power and create a peaceful and artistic atmosphere. Urban context has changed greatly. The top-level cultural building designs become the arena of international design firms. Architects from Europe have won most number of grand theatre design, they enjoy an opportunity which is rare in their home continent. Foreign architects’ methods, especially in the beginning of the 21st century, were remote from the Chinese routine. Chinese architects are learning quickly in this process and picking up steadily. Linear, geometric and radical forms all find their usefulness and acceptance in the clients and municipal leaders. The selected designs reflected the taste of decision makers in a particular period. Isozaki Arata and gmp’s winning schemes after 2010 demonstrate the maturity of clients and government.

At the end, cultural buildings should facilitate people’s civic life. Chinese cities and their people deserve more enjoyment and sharing of cultural facilities and their affiliated public space. In the end, governments should be held accountable for the use of taxpayers’ money, a public building should serve people, and a city should make people’s lives better.

In February 2017, the Ministry of Culture published The National Plan for Cultural Development and Reform in the 13th Five-Year Planning Period, which mentions that the “13th Five-Year Plan” period is the decisive stage in building a moderately prosperous society, and actively promoting the government of all levels to place cultural construction on an important position, improving the network of public cultural facilities, and enhancing the efficiency of public cultural services (Ministry of Culture of the people’s Republic of China Citation2017). The realization of the above objectives rests upon the reasonable spatial layout of cultural facilities and the diversified, human-oriented design and management of public space (Gou and Lau Citation2016). Based on the construction of cultural mega projects in China over the recent two decades, it is easy to find that the variety becomes increasingly complete, and has met citizens’ demand for the number of cultural facilities. However, the spatial quality of cultural buildings is inadequate. Cultural building and number of seat per capita are lower than that of developed countries.

Meanwhile, China is now in the accelerated period of urbanization, along with the reform of China’s administrative system of culture. This will inevitably change the design and shape of grand theatres/cultural buildings. The national and global competition for resources and attentions are continuing. Cultural buildings will definitely be used as a physical means of bidding the fame. What has happened in the Chinese cities will give a timely lesson for the other countries who strive to embark on the way towards modernization and globalization in the 21st century.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of a study supported by the Research Grant Council, Hong Kong government, Project No.: CityU 11658816. The authors heartily thank the valuable opinions from Professor Alexandra Harrer and anonymous reviewer.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Charlie Qiuli Xue

Dr. Charlie Qiuli Xue has published 12 books, includingBuilding a Revolution: Chinese Architecture since 1980 (HKU Press, 2006), Hong Kong Architecture 1945-2015: From Colonial to Global (Springer, 2016), A History of Design Institutes in China: from Mao to Market (Routledge, 2018, with G. Ding), and Grand Theater Urbanism: Chinese cities in the 21st century (Springer, 2019, ed.). He has published more than 100 research papers in professional and international refereed journals. His research focuses on modern architecture in China and design strategies for high-density environments.

Cong Sun

Cong Sun is a Ph.D. candidate and also works as a research assistant at the City University of Hong Kong with interests in the linkage of cultural facilities distribution and urban expansion, the tension between urban policy and architectural practice. She has published research papers in international refereed journals. Before joining CityU, she had worked in a global architecture firm for more than 3 years and had been involved in many large projects both in Hong Kong and Mainland China.

Lujia Zhang

Lujia Zhang is a Ph.D. candidate at the City University of Hong Kong. She obtained her master degree in architecture from the South China University of Technology in 2016 and bachelor degree of architecture from Zhengzhou University in 2013. She is interested in contemporary Chinese architecture practice and criticism. She participated in several design practices and research projects during her study periods in Guangzhou and Hong Kong.

Notes

1 The data is collected and calculated by the authors.

2 The management situation is taken from the interview of general manager Ms. Zhang Xiaoding, engineer Wu Zhihua and executive officer Pan Lan on 3 July 2017.

3 The situation of Shenzhen Concert Hall is learnt from the authors’ interview of the managers Li Shunchao and Yang Qingxi on 30 November 2016.

References

- Andreu, P. 2015. Archi Memories. Beijing: CITIC Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Chang, T. 2000. “Renaissance Revisited: Singapore as a ‘Global City for the Arts’.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24 (4): 818–831. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00280.

- Cheng, Y. 2015. Contemporary Performing Arts Architecture in the Multidimensional Perspective. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press.

- China Statistic Bureau. 2019. China Statistic Yearbook. Beijing: China Statistic Press.

- Enright, T. 2016. The Making of Grand Paris. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Featherstone, M., and S. Lash, eds. 1999. Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World. London: Sage.

- Gates, B. 2014. “Have You Hugged a Concrete Pillar Today?” Gatesnotes: The Blog of Bill Gates, June 12. https://www.gatesnotes.com/Books/Making-the-Modern-World

- Gou, Z., and S. Lau. 2016. “Contextualizing Green Building Rating Systems: Case Study of Hong Kong.” Habitat International 44: 282–289. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.07.008.

- Grenfell, M. 2004. Pierre Bourdieu: Agent Provocateur. London: Continuum.

- Hong Kong Cultural Centre. 2017. Annual Report of Hong Kong Cultural Centre, 2014–2016. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Cultural Centre.

- Izenour, G. C. 1996. Theatre Design. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Jencks, C. 2004. The Architecture of the Jumping Universe: A Polemic: How Complexity Science Is Changing Architecture and Culture. London: Academy Editions.

- Klingmann, A. 2007. Brandscapes: Architecture in the Experience Economy. New York: MIT Press.

- Kong, L., C. Ching, and T. Chou. 2015. Arts, Culture and the Making of Global Cities – Creating New Urban Landscape in Asia. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Lu, Y., Y. Yang, G. Sun, and Z. Gou. 2019. “Associations between Overhead-view and Eye-level Urban Greenness and Cycling Behaviors.” Cities 88: 10–18. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.01.003.

- Ministry of Culture. 2007. Wenhua Shiye Fazhan Jiuwu Jihua He 2010 Nian Yuanjing Mubiao Gangyao. (Development Plan of Cultural Affairs and the Vision of 2010). Beijing: Ministry of Culture.

- Ministry of Culture of the people’s Republic of China. 2017. “The National Plan for Cultural Development and Reform in the 13th Five-Year Planning Period.” http://zwgk.mcprc.gov.cn/auto255/201702/t20170223_491392.html

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. 2016. Code for Design of Theater Building JGJ 57-2016. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Murray, P. 2004. The Saga of the Sydney Opera House: The Dramatic Story of the Design and Construction of the Icon of Modern Australia. New York: Spon Press.

- Owens, P. 2013. World Cities Cultural Report. Shanghai: Tongji University Press.

- Shanghai Grand Theatre. 2017. 2015–16 Annual Report. Shanghai: Shanghai Grand Theatre.

- Shen, L., W. Lu, and B. Wang. 2016. “Strategic Thinking on the Cultural Spatial Planning of Shanghai Towards a Global City.” Urban Planning Forum 3: 63–70.

- Short, J. R. 2004. Global Metropolitan: Globalizing Cities in a Capitalist World. London: Routledge.

- Sun, C. 2019. “Appendix I, “Database of Grand Theatres in China: 1998–2018.” In Grand Theatre Urbanism – Chinese Cities in the 21st Century, edited by C. Xue, 75. Singapore: Springer.

- Xiao, Y., Y. Wan, and C. Xue. 2019. “Performing Art Buildings in Taiyuan – A Cultural Building History in a Second-tier Chinese City.” Frontiers in Architectural Research 8 (2, May): 215–228. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S209526351930024X?via%3Dihub

- Xue, C. Q. L. 2006. Building a Revolution: Chinese Architecture since 1980. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Xue, C. Q. L. 2010. World Architecture in China. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing Ltd.

- Xue, C. Q. L., ed. 2019. Grand Theatre Urbanism: Chinese Cities in the 21st Century. Singapore: Springer.

- Xue, C. Q. L., and G. Ding. 2018. A History of Design Institutes in China: From Mao to Market. London: Routledge.

- Xue, C. Q. L., and M. Zhou. 2007. “Importation and Adaptation: Building “One City and Nine Towns” in Shanghai, a Case Study of Vittorio Gregotti’s Plan of Pujiang Town.” Urban Design International 12 (1): 21–40. doi:10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000180.

- Zukin, S. 1993. Landscape of Power: From Detroit to Disney World. Berkeley: University of California Press.