ABSTRACT

This paper compares the changes in the production of wooden houses after WWII in Jeollanamdo in South Korea and Okinawa Prefecture in Japan. This study finds that wooden house production shares the following similarities in both locations: (1) traditional wooden post and beam houses were constructed by local carpenters using local wood; (2) following WWII, houses came to be constructed of concrete blocks or reinforced concrete instead of wood; (3) in the 1980s and the 1990s, the number of light-frame wood houses increased; and (4) in the 1990s and the 2000s, wooden post and beam houses increased.

This paper examines two case studies conducted in Jeollanamdo and Okinawa Prefecture, respectively, to better understand the current status of wooden post and beam house construction. Jeollanamdo initiated a Happiness Village Project in 2007. This initiative increased the construction of post and beam houses by addressing the shortage of experienced contractors. Starting in the 1990s in Okinawa, the adoption of precut lumber increased the construction post and beam houses, negating the need for traditionally skilled carpenters. However, due to there being few experienced contractors, factories producing precut lumber supported small-scale contractors through training and additional services.

Chemical modification of respiratory complex I. The author focuses on structural features of the binding pocket of quinone/inhibitors in complex I.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

In response to the sustainability movement, wooden houses, and other timber buildings have recently regained popularity in several Asian countries. Following WWII, many regions where people had traditionally lived in wooden houses rapidly transitioned to building structures out of different materials, such as concrete. This paper focuses on Jeollanamdo in South Korea and Okinawa Prefecture in Japan (), both of which replaced wood construction with concrete block or reinforced concrete (RC) construction after WWII. Whereas the whole of South Korea underwent this change, other prefectures in Japan besides Okinawa did not undergo such changes. Due to a decrease in wooden house construction and a move away from the excessive use of forest resources, the number of carpenters decreased and stocks of local lumber diminished. Moreover, wooden house construction became expensive and more difficult. However, despite this shortage of both lumber and skilled workers, the construction of post and beam houses in South Korea began increasing after 2000 (Gondo et al. Citation2013). In Jeollanamdo particularly, the construction of wooden post and beam houses was promoted by the local government (Kim et al. Citation2014). Okinawa Prefecture also witnessed an increase in the construction of wooden post and beam houses beginning in the 1990s (Gondo, Uehashi, and Matsumura Citation2010). The accumulated knowledge and experience of both regions can also be applied to other regions or countries attempting to support the construction of wooden buildings.

Table 1. The Location and Basic Information concnering Jeollanamdo and Okinawa Prefecture

Despite many similarities, there are also many difference separating Jeollanamdo and Okinawa Prefecture concerning the construction of wooden post and beam houses, such as the characteristics of wooden post and beam houses in each region and the distinct practices of wooden home contractors. However, no research comparing the production systems of wooden house construction in Jeollanamdo and Okinawa Prefecture has been conducted. This paper employs the term “production system” to refer to the matrix of contractors, working conditions, material supply, laws and regulations, and building systems, all of which effect the construction of wooden houses.

1.2. Purpose

This paper aims (1) to clarify the similarities and differences in the reemergence of wooden house production systems following WWII in Jeollanamdo in South Korea and Okinawa Prefecture in Japan. In particular, this study focuses on the recent growth of wooden post and beam construction and (2) elucidates the current status of and challenges facing wooden post and beam house production systems in both regions.

1.3. Method

We conduct a literature review and analyze statistical data to examine the reemergence of wooden house production systems in South Korea and Okinawa Prefecture following WWII. In the case of South Korea, we considered the decrease and subsequent increase in wooden house construction following WWII across the entire country, not just Jeollanamdo. However, such country-wide trends are not observable in Japan, so our analysis was limited to Okinawa Prefecture.

Second, through interviews with government officials, wooden house contractors, architects, carpenters, and lumber mill employees in Jeollanamdo and Okinawa Prefecture, the authors clarified the current situation of and problems facing wooden house construction. In order to provide a comprehensive understanding of these matters, we explored: (1) factors influencing the increase of wooden post and beam houses, (2) the characteristics of wooden post and beam houses and (3) the practices of wooden house contractors. Wooden house contractors are defined as construction firms that design and build wooden houses under contract with a customer. In interviews with wooden house contractors, we asked about their general business practices, the material and design characteristics of houses, and the condition of workers.

We interviewed 17 wooden house contractors, three architectural firms, several government officials, and multiple employees from five lumber mills between 2012 and 2013 in Jeollanamdo. Fifteen of the 17 contractors were registered as contractors for Happiness Village Project (HVP) by the Jeollanamdo local government in 2012 (28 contractors in total, as described in 4.1 (3)). The remaining two builders also constructed traditional Korean hanok (meaning, “Korean house”) as part of the HVP.

Between 2008 and 2009 in Okinawa, we interviewed 16 wooden house contractors, employees from four architectural firms, government officials, and employees from four lumber mills producing precut lumber, among others. These 16 wooden house contractors built approximately 100 wooden houses in 2007, which comprised approximately 70 percent of all wooden house built in Okinawa Prefecture that year (“housing starts” according to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure). In addition, the four precut lumber mills at which we interviewed employees had been mentioned by wooden house contracts in the interviews.

Therefore, the number or the market share of interviewees of the wooden house contractors in each area was assumed to occupy over 50 % at the survey time. In addition, although the time of the survey in each area differed approximately four to five years, the author put the importance of the actual situations occurring in the increase of wooden post and beam houses.

2. Review

A number of research studies have analyzed construction of post and beam houses in South Korea and Okinawa Prefecture. However, few studies have focused on the interrelationships between workers, contractors, and material suppliers in the process of constructing wooden post and beam houses. In the 1990s, the construction of wooden houses began increasing in South Korea. Subsequently, a significant number of studies focusing on the wooden house market (Park M. J. et al. Citation1991) and wooden house building systems (Lee Citation1992) were conducted. Starting in the 2000s, research on wood construction began focusing on environmental aspects, such as carbon dioxide reduction and sick building syndrome (Chang Citation2003). Following the implementation of initiatives to support traditional hanok construction by local governments in the late 2000s, there has been an increase in research focusing on the planning and development of the mass production of traditional hanok (Kim Citation2006). Such studies incorporate information technologies (Jeon Citation2009a) and the standardization of building parts (Park et al. Citation2012b). However, there are difficulties in applying industrializing technologies to hanok construction. For example, Lee (Citation2010) points out difficulties associated with the industrialization and standardization of large circle section column construction, such as cracking and twisting during drying. However, few studies have focused on contemporary wooden house production systems (Bang et al. Citation2010), particularly in the context of carpenters and wooden house contractors.

Starting in the 1980s, several studies in Japan have focused on wooden house production systems in a number of regions. Fujisawa et al. (Citation1983) and Ando et al. (Citation1982) identified a small network of builders and analyzed the rationale informing the adoption of these building systems in several areas of Japan. Beginning in the early 2000s, Sumikura and Matsumura (Citation2011) and other scholars attempted to clarify the relationship between the practices of small wooden house contractors and wooden post and beam house building systems. However, few studies have considered these questions in the context of Okinawa Prefecture. Ogura et al. (Citation1988) analyzed RC house production systems in the context of small architecture firms. Meanwhile, Fukushima et al. (Citation1986) studied traditionally skilled workers, including carpenters who construct wooden houses. However, these studies do not account for the increase in wooden post and beam house production beginning in the 1990s. As an exception, Gondo, Uehashi, and Matsumura et al. (Citation2010) focused on the increase of wooden post and beam construction after 1990.

Several studies have compared historical changes in styles, methods, and materials used in the construction of houses in South Korea and Japan. For example, Tomii et al. (Citation1988) examined the influence of traditional hanok design, local climate, and Japanese public housing on public housing in South Korea since the 1930s. Suzuki et al. (Citation1986) compared the modernization of houses in South Korea and Japan by conducting surveys in suburban and urban areas in both countries. Choi et al. (Citation1997) analyzed the construction of apartment buildings in South Korea from the1960s to the 1990s, considering housing quality and housing policy. These previous studies have clarified the similarities and differences of South Korean and Japanese housing production systems from several viewpoints. However, this study adds to existing literature by focusing on the revival of wooden post and beam house construction from the viewpoint of production system including workers, materials, among others, and the process to the revival in these two countries after the end of WWII.

3. Housing production systems in Okinawa Prefecture and South Korea after WWII

3.1. Traditional wooden house production

In South Korea and Okinawa Prefecture, traditional houses were wooden post and beam structures built by carpenters using local lumber.

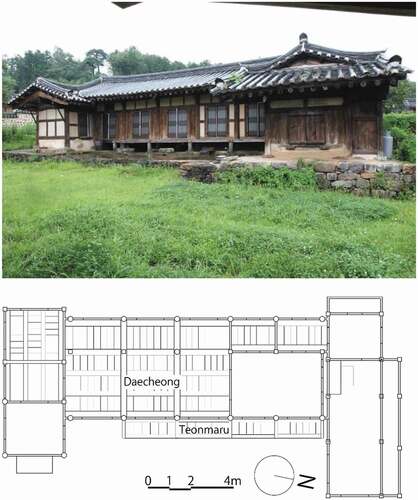

In South Korea, traditional post and beam houses are generally referred to as hanok. The term hanok came into usage as a word defined in opposition to yangok (meaning, “Western house”), which entered the Korean language in the nineteenth century (Song Citation2006). There are several classifications of hanok, including giwa-zip (giwa meaning “roof tile”; zip meaning “house”; see ) and choga-zip (choga meaning “thatch”). Although common people historically lived in choga-zip, beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, giwa-zip became more common in urban areas. (Yoon Citation2011). Jeon (Citation2009b) has developed an alternative classificatory scheme, identifying “cultural hanok,” “legitimate hanok,” “contemporary hanok (new-hanok; urban-hanok),” “hanok-like buildings,” and “Korean buildings.” So-called “cultural hanok” and “legitimate hanok” have generally been constructed by carpenters known as moksu. In addition, Park et al. (Citation2005) pointed out that 57 percent of important wooden cultural buildings use Korean pine, 27 percent use zelkova, and 4 percent use sawtooth oak.

Figure 1. Exterior and floor plan of a traditional wooden house in South Korea (18 C. Yang Cham-sa In Hwasun, latitude: 34.98, longitude: 126.91, traced from Michuhol Architect’s Office, Inc. Citation2011)

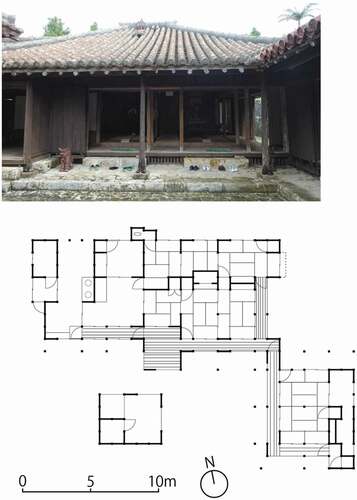

In Okinawa, traditional houses called nuchija were wooden post and beam structures () primarily inhabited by the ruling classes. These houses were built from Okinawan inumaki (Buddhist pine) or other regional lumbers. These traditional houses feature a roof with long eaves covered in red tiles and are built by carpenters or local residents of the community (yui). Okinawan carpenters are known as ogimi daiku (daiku meaning “carpenter”; while ogimi is Okinawan regional titles) (Fukushima et al. Citation1986).

Figure 2. A traditional wooden house in Okinawa Prefecture (Nakamura-ke, 18 C, latitude: 26.29, longitude: 127.80, traced from Research Institute of Architectural Thought Citation1991)

3.2. Housing shortages and decreases in wooden house production

Following WWII, housing shortages occurred in South Korea and Japan. In South Korea, the population increased by approximately 25 percent from the end of WWII in 1945 to the start of the Korean War in 1950. Moreover, by the outbreak of the Korean War, 18 percent of housing had been destroyed, exacerbating the housing shortage (Park et al., Citation2012a). Additionally, WWII and the Korean War decimated South Korean forests. Indeed, by 1960, growing stocks in forested areas had decreased to 9.55 m3/ha. In 1961, the South Korean government implemented a forest protection policy and began reforesting the country, initiating a tree planting program in 1973 (Park Citation1998). Due to rapid urbanization, cement building construction – such as those using RC and concrete block flats – became common. The South Korean government supported the RC industry, particularly the cement industry (Kim Citation1992). Unsurprisingly, the number of building permits for wooden structures decreased from roughly 10,000 in 1970 to less than 1,000 in 1980, dropping sharply again to 481 in 1994 (See ; Statistics on Annual Wooden Building Permission, MLTM).

Figure 3. Wooden buildings permitted for construction in South Korea (non-wooden buildings vs wooden buildings). Data: Statistics on Building Permission, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport of Korea (the statistics are divided according to building type (house, public, other) and materials (wood, RC, and steel, masonry, other). However there are no statistics on wooden houses)

At the outset of WWII, there were approximately 126,000 houses in Okinawa. However, roughly 100,000 houses were destroyed as a consequence of the war (Tanoue Citation2003, 41). Following WWII, the Okinawan government, which at the time was under the control of the United States, constructed roughly 80,000 temporary wooden houses. These modestly constructed houses were not resistant to termites or typhoons (Kinjo and Ogura Citation2018) and as a result Okinawans gained the impression that wooden houses are not durable. Furthermore, despite the need to reconstruct cities after the war, only a small stock of lumber was available for building houses, as it had been greatly diminished by the war. Concurrently, the United States military bases were being constructed in Okinawa at this time. Indeed, a significant number of concrete block and RC houses were constructed for US military use, which contributed to the development of the concrete block and RC industry in Okinawa. In addition, the Okinawan government incentivized to build concrete block and RC houses by providing low-interest rates to finance the building of fireproof houses which used concrete block and RC. According to the funding scheme established by the Okinawa government in 1950, the loan period for wooden houses was eight years and was subsequently extended to 15 years. Likewise, the loan period for conceret block houses was 10 year, which was later extended to 20 years (Kohatsu Citation2005). As a result of these historical circumstances and government initiatives, concrete block, and RC houses largely replaced wooden houses in Okinawa. Indeed, by 1961, the number of non-wooden houses had eclipsed that of wooden houses. In 1981, only 40 wooden houses were built in Okinawa (Okinawa Prefecture Citation1996). As a consequence of the market for wooden houses shrinking significantly, the number of carpenters in Okinawa decreased drastically and the shortage of lumber continued. This change mirrors the situation in South Korea.

3.3. An increase in light-frame wood construction

An increase in the construction of light-frame wooden houses has been observed in South Korea and Japan, particularly in Okinawa Prefecture. Light-frame wood construction methods were imported from North America and Europe. Light-frame wooden houses use dimensional lumber and light-frames or panels cut to specific dimensions (e.g., 2 in. x 4 in.). This differs greatly from post and beam construction, which consists of linear components, such as posts and beams. Starting from the 1980s in Okinawa Prefecture and the 1990s in South Korea, light-frame wooden houses became more common. Light-frame wood construction was authorized by the Japanese Ministry of Construction in 1974, resulting in its wide-scale implementation across the country. By the late 1970s and 1980s, several contractors in Okinawa began building light-frame wooden structures. According to interviews with two contractors who began building light-frame wooden structures in the 1980s, many Okinawa inhabitants saw light-frame wooden houses while traveling abroad, inspiring them to have light-frame wooden house of their own built. Statistics on Japanese construction (“Housing Starts” by Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism) reveal that in 1988, 36 light-frame wooden houses were built in Okinawa Prefecture. By 1999, this number increased to 145. Moreover, the ratio of light-frame wooden houses to wooden detached houses was over 50 percent between 1993 and 1999, excluding 1995. In this regard, Okinawa is clearly an exception within Japan as a whole, where the same ratio has remained at 10 to 15 percent.

According to interviews with two contractors in South Korea who began building light-frame wooden structures in approximately 1990, after the deregulation of overseas travel in 1988, South Koreans began traveling abroad where they observed light-frame wooden houses and subsequently began building their own such houses in suburban areas. One of these contractors studied light-frame wood construction in Sweden; the second contractor was educated in the United States. In 1990, an exhibition of light-frame wood construction was held in Seoul, South Korea. The American Forest and Paper Association (No Citation2001) established a South Korean office to promote the growth of light-frame wood construction.

There are several common factors influencing the increase in light-frame wood construction in both South Korea and Okinawa Prefecture. Indeed, as our interviews revealed, the popularity of light-frame wooden houses increased after Korean and Japanese people saw them while traveling abroad. Moreover, as several contractors indicated, due to a lack of lumber and carpenters, light-frame wood construction held several advantages over post and beam construction, which requires skilled carpenters who can fashion wooden joints by hand. In addition, wooden post and beam construction requires lumber cut to specific dimensions. Therefore, junior carpenters were often trained only in light-frame wood construction. In some cases, lumber was imported from Western countries. Additional building supplies necessary for light-frame wood construction were also imported alongside lumber, as they could not be sourced domestically in either South Korea or Okinawa Prefecture. This method is referred to as “packaging imports.”

3.4. An increase in wooden post and beam houses

By the 2000s, the ratio of wooden buildings in South Korea remained small; however, this ratio started to increase in the 2000s. No statistics related to wooden house construction in South Korea exist prior to 2001. The number of newly built wooden houses was 481 in 2002. This figure increased to 6,425 by 2011 (). In 2010, the ratio of newly built detached wooden houses to existing detached houses was 9.85 percent (“Annual Wooden House Commencement Work,” MLTM (The Ministry of Land, Transport and Maritime Affairs of Korea)). However, these statistics only record wooden construction in general, and do not differentiate between light-frame wood construction and post and beam construction. Thus, it is difficult to prove an increase in wooden post and beam houses in South Korea.

Figure 4. Wooden buildings and house construction in South Korea (“Statistics of Housing Construction,” The Ministry of Land, Transport and Maritime Affairs of Korea)

The MLTM and local governments in South Korea – including the local government of Jeollanamdo – began promoting the construction of post and beam houses, particularly those which utilize a hanok design. The MLTM began promoting hanok-style post and beam construction in 2009. In the same year, the National Hanok Center was established under the authority of the Architecture and Urban Research Institute (AURI). The National Hanok Center began industrializing the construction of hanok in an attempt to reduce construction costs and to improve planning and construction design. As part of this initiative spearheaded by the MLTM, the HVP was introduced in Jeollanamdo. Several hanok preservation projects preceded these attempt to industrialize and expand hanok production. Since approximately 2000, governments and associations have pursued the preservation of hanok in the urban areas of Seoul and Jeonju. Since 2001, authorities have been attempting to preserve the many hanok in Bukchon village that were built in the 1930s. In 1998, Jeonju City initiated a hanok preservation program and constructed additional hanok structures in order to attract tourists. In contrast to these preservation projects, the National Hanok Center and the Jeollanamdo government focused on advancing “contemporary hanok,” for people to actually purchase and live in.

In Okinawa Prefecture, instances of newly constructed wooden houses were significantly less when compared to Japan as a whole. In 2010, only 10.2 percent of newly built detached houses were wooden. In all of Japan, this ratio was 86.6 percent. In Okinawa, 62.7 percent of these were RC houses (“Housing Starts”by Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport). This small ratio of wooden post and beam houses resulted in a shortage of skilled carpenters and a reliable lumber supply in Okinawa. In contrast, the number of newly built post and beam houses has recently increased (). From the 1990s up until 2005, approximately 100 wooden post and beam houses were built in Okinawa each year. This figure began increasing since 2005, reaching 692 in 2016. This increase in wooden post and beam houses is a result of the growth of precut lumber construction, as explained in section four.

Figure 5. The ratio of wooden houses, post and beam houses, and wooden light-frame houses in Okinawa (annual building statistics “Housing Starts” provided by Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism). Wooden houses are divided to wooden light-frame houses, wooden prefabricated houses, and other. The number of post and beam houses are calculated by subtracting the number of wooden light-frame houses and wooden prefabricated houses from the total number of whole wooden houses

4. Contemporary wooden post and beam housing production systems in the two regions

4.1. Case Study 1: the HVP in Jeollanamdo

4.1.1. An increase in hanok in Jeollanamdo

The Jeollanamdo provincial government (JPG) initiated the HVP in 2007 with the objective of promoting hanok construction as a tourism resource and a tool for revitalizing rural populations.

In 2005, the JPG issued an ordinance supporting the project and published a hanok construction plan for June 2005, titled “Hanok Construction Manual” in 2006. In addition, in September 2006, the JPG established a task force to oversee the project. In 2007, a pilot project was launched, with a public contest being held in 2008. However, problems concerning the quality and durability of hanok construction arose, prompting the JPG to introduce an alternative designated contractor system in 2010.

The JPG had planned to construct 3,152 houses by 2014. By November 2011, 648 houses had been constructed in 90 villages. In addition, 1,281 houses were confirmed to be constructed (, Data from “Present Condition of promoting HVP” by JPG website). An average of 256 houses were constructed per year, comprising 34 percent of the total building permits granted for the construction of wooden houses in Jeollanamdo (as per 2010 numbers). In South Korea, hanok are generally more expensive to build than RC houses. Thus, JPG issued an ordinance to provide low-interest loans for houses constructed using RC. The JPG provided individual low-interest loans of 20 million KRW at an annual interest rate of 2 percent. At the start of the project, the South Korean government supported all eligible construction projects. However, since 2008, the JPG has supported only groups of dwellings comprising 10 houses or more in order to reduce construction costs and increase the efficiency of the HVP. In addition to this, the JPG and the provincial office are providing 150 million KRW annually for the development of the infrastructure of villages of HVP.

Table 2. The number of hanok completed as part of the Happiness Village Project (HVP). (Data from “Present Condition of promoting HVP” by JPG website (http://happyvil.jeonnam.go.kr, 2013.5 access). HVP consists of three types, adding new hanok to existing village (Development), constructing several hanok as newly village (Construction) and registering hanok existing area as Happiness Village (Maintenance)

4.1.2. Characteristics of hanok in the HVP

During the early stages of the HVP, no legal definition was in place for clarifying the meaning of hanok. In 2006, the JPG subsequently adopted a legal definition of the term, as well as design () and construction standards for hanok (). These regulations stipulated that hanok must be constructed using traditional techniques. Moreover, primary structural components such as columns and girders must be constructed using hardwood. In addition, the HVP established guidelines for the promotion of environmentally friendly construction. Accordingly, projects must generally avoid environmentally harmful building materials, such as concrete, in the construction of hanok.

Table 3. Hanok construction standards

Figure 6. Floor plan of a standard hanok design for the HVP. Traced from HVP website (http://happyvil.jeonnam.go.kr/, accessed on 10. 4. 2020)

Lumber from large-diameter Douglas firs is generally used for columns and girders, as it is similar in color to yuksong (South Korean red pine). Douglas fir is directly imported from the United States without the involvement of international trade intermediaries. However, for small-diameter lumber, South Korean larch is used instead of yuksong to reduce cost. is an example of a hanok built as part of the HVP and designed by one of the architecture firms we interviewed. The structure uses 300 mm diameter columns at the corners and 270 mm diameter columns elsewhere.

Figure 7. An example of a hanok for the HVP. Traced from the plans and sections from one of the interviewees (latitude: 35.21, longitude: 127.02)

In interviews, most contractors stated that they purchased South Korean larch directly from lumber dealers, wooded land owners, and forest associations in Kangwon Province. However, a representative of lumber mill J stated that it is difficult to find high-quality lumber when purchasing from forest associations. Additionally, other lumber mill representatives and contractors expressed that they were reluctant to buy from forest associations as they were expensive. When buying domestic lumber, most contractors attempt to buy enough lumber an entire year between November and March, as they consider lumber bought during this season to be the highest quality.

4.1.3. Contractors

Upon the commencement of the HVP, the JPG was declared responsible for selecting villages; however, it was not responsible for overseeing contracts between contractors and residents. Hanok structures built as part of the HVP are smaller than 661 m2. As such, there was no need to obtain a construction license for hanok construction as per the “Framework Act on the Construction Industry, Article 41” (Restrictions on Executors of Construction Works). For this reason, there was considerable competition among contracts bidding to win projects. The participation of contractors without valid construction licenses resulted in poorly constructed buildings. Thus, the JPG established a designated contractor system to address these quality issues.

At the start of each year, the JPG inspects contractors’ bid applications based on specific criteria. Beginning in 2010, a list of contractors who have satisfied the JPG’s requirements for registration from February to the February of next year are published on the website of the HVP. In 2010, 54 construction firms located in Jeollanamdo submitted applications. In 2011, in order to enhance building quality, this was limited to applicants in possession of an expert wooden building construction license. Nonetheless, up to 60 companies registered. Since 2012, registration criteria have become stricter; only construction companies employing two experts or more are able to apply for projects. Additionally, contracts will be annulled if the contractor has constructed less than five houses within the last two years. The contract will also expire or be annulled if residents complain more than twice about construction quality. As a result of these new rules, the total number of registered contractors decreased to 28 in 2012.

4.2. Case Study 2: recently constructed post and beam houses in Okinawa Prefecture

4.2.1. An increase in post and beam construction

As noted in section 3.4, wooden post and beam construction has increased over the past several decades in Okinawa. This increase was caused by the use of precut lumber from southern Kyushu in housing construction beginning in the early 1990s. “Precut” refers to a type of lumber used in post and beam construction where the joints are cut to specific dimensions in advance. Prior to adopting the precut method, Japanese carpenters used chisels to create post and beam joints.

In 2009, we interviewed 16 post and beam contractors and one architectural firm in Okinawa. Sixteen of the interviewees used precut lumber, with only one contractor stating that they did not use precut lumber. According to interviews, 13 contractors and one architectural firm that previously had no experience in post and beam construction were able to successfully construct post and beam buildings by applying the precut method. In Okinawa, post and beam construction had been impractical due to the scarcity of skillful carpenters and the high price of lumber. However, precut lumber made skillful carpenters redundant, as they were no longer needed for post and beam construction.

4.2.2. Characteristics of houses

Unlike Jeollanamdo, Okinawa Prefecture did not implement rules regulating the design of post and beam houses. In Okinawa, financial support was provided for the construction of post and beam houses with red-tile rooftops only. However, the use of red-tile roofing has been limited (Morita et al. Citation1993). In addition, financial support for traditionally designed houses is only available to houses located in areas designated as traditional preservation areas (The Okinawa Development Finance Corporation Citation2017).

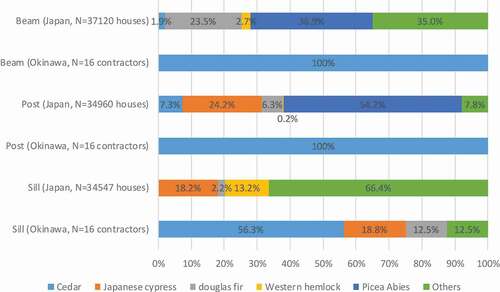

shows the ratios of wood species used by contractors in Okinawa as per our interviews with 16 contractors. Compared to other regions in Japan, a higher ratio of contractors in Okinawa use cedar. In particular, cedar is used in the construction of beams and sills. Many structural elements used for wooden posts and beam houses are precut in southern Kyushu, which produces a large amount of cedar. This is, in turn, reflected in the construction of wooden houses in Okinawa.

Figure 8. The ratio of wood species used by contractors in Okinawa. Okinawa data was gained from interviews with 16 contractors. Data related to Japan was sourced from the.Wooden Home Builders Association of Japan (Citation2005)

4.2.2. Contractors

Despite the introduction of the precut method, several problems related to post and beam construction remained in Okinawa. First, although structural materials are precut in factories, contractors are still required to assemble the pieces on site, which demands additional workers. Six of the contractors we interviewed in Okinawa used panel carpenters employed by RC construction firms to assemble precut lumber. In order to increase the number of wooden houses being constructed in Okinawa, precut lumber mills dispatched skillful carpenters from southern Kyushu to Okinawa and invited Okinawan carpenters to southern Kyushu for training.

Second, components used in post and beam houses, such as metal joints and ventilation systems, were not available in Okinawa. Therefore, precut factories began distributing these building parts alongside precut lumber. This distribution strategy is similar to the “package import” method used in light-frame wooden house construction. These building parts are, however, widely available in other areas of Japan where wooden post and beam construction is prevalent.

Third, most of the wooden house contractors in Okinawa are small firms with minimal experience in wooden house construction. Eleven of the16 contractors interviewed had constructed less than 10 houses in 2007. As a result, they struggle with multiple tasks besides construction, such as making structural calculations and developing sales strategies. Therefore, all four precut lumber mills interviewed also provide construction firms with structural calculation support. Moreover, provincial governments in southern Kyushu have made sales support programs available.

5. Discussion

5.1. Similarities

As mentioned in section three, several similarities exist concerning the construction of wooden houses in South Korea (including Jeollanamdo) and Okinawa Prefecture in Japan (). First, traditional houses in both regions were historically wooden post and beam structures. These houses originally used regional lumber and were constructed by local carpenters. Second, due primarily to a housing shortage after WWII, as well as rapid reconstruction efforts, urbanization, the adoption of new fuel sources, and lumber shortages, wood was replaced by concrete as the primary material for house construction. Third, the number of concrete block and RC houses increased. The governments of both South Korea and Okinawa supported the concrete industry for economic reasons. Fourth, beginning in the 1980s in Okinawa Prefecture and the 1990s in South Korea, the construction of light-frame wood construction increased. Although wooden houses grew in popularity, only a small number of carpenters were skilled enough to build them. Also, the lumber needed for these light-frame wooden houses had to be imported from Northern America and Europe. Finally, primarily beginning in the 1990s in Okinawa Prefecture and the 2000s in South Korea, the number of wooden post and beam houses once again increased. However, there was a lack of skilled carpenters and contractors with sufficient experience in wooden post and beam construction. There was also a shortage of lumber that could be used for wooden post and beam construction. Therefore, following WWII, both South Korea and Okinawa first experienced a decline in wooden house construction, followed by a subsequent decrease of carpenters and lumber supply. Thus, in the process of revitalizing wooden post and beam construction, such shortages presented considerable challenges. Therefore, light-frame wood construction increased first, followed by an increase of wooden post and beam construction. In Jeollanamdo, both forms of construction benefited from the support of local government. In Okinawa Prefecture, these forms of wood construction benefited from the introduction of precut lumber.

Table 4. Comparison of the Transition Process of House Production Systems in Jeollanamdo and Okinawa Prefecture

5.2. Differences

Several differences can be observed between Jeollanamdo and Okinawa Prefecture. First, particularly concerning regulations set up by the HVP, Jeollanamdo required construction projects to use traditional housing designs. In Okinawa Prefecture, the design of post and beam houses was the choice of each resident, contractor, or architectural firm. This difference is a result of the different players promoting post and beam houses in South Korea and Okinawa. In the case of the HVP, the local government was responsible for promotion. The JPG created regulations demanding adherence to traditional hanok designs. In the case of the HVP, the need to follow traditional South Korean designs made it difficult to industrialize the production of wooden post and beam houses, as traditional designs require large circle section columns, as Lee (Citation2010) points out. In contrast, wooden post and beam house construction in Okinawa has employed industrialized precut lumber from the beginning. In Okinawa, the government did not incentivize to the construction of traditional wooden post and beam houses; therefore, precut lumber mills were able to ignore traditional design.

Second, in Jeollanamdo and Okinawa, there was a lack of contractors with experience constructing post and beam houses, as the market for wooden post and beam houses has been historically small. In South Korea, several problems were posed by this lack of experience, requiring the Jeollanamdo government to implement a registration program for contractors desiring to build contemporary hanok, which required skilled carpenters and contractors in contrast with the western post and beam houses or precut post and beam houses. Furthermore, the Jeollanamdo government published a standard plan that included construction manuals. In Okinawa, precut lumber mills supported contractors by training carpenters working for small firms, providing structural calculation, and supplying building parts in addition to lumber. Therefore, there are clear difference in the source and type of support provided to small contractors.

6. Conclusion

Our study comes to the following conclusions. First, wooden house production systems in Jeollanamdo (and the whole South Korea) and Okinawa Prefecture shared various commonalties at several stages of development. Following WWII, the decline of wooden house production caused the number of wooden house carpenters and contractors to decrease alongside lumber production. In addition, a shortage of workers and resources needed for the construction of wooden post and beam structures made it difficult to revitalize the wooden post and beam construction industry. Indeed, this is reflected in the fact that light-frame wood construction began to increase before wooden post and beam construction. Second, several obvious differences exist between South Korea and Okinawa Prefecture concerning the factors effecting the increase in wood construction. In Okinawa Prefecture, precut lumber made it possible to undertake post and beam construction in areas that lacked skilled carpenters. In contrast, the South Korean government and local governments, including Jeollanamdo, began promoting wooden post and beam houses using traditional designs in a bid to elevate traditional culture and support environmentally friendly lifestyles. Third, according to surveys conducted in Jeollanamdo and Okinawa Prefecture, in addition to a shortage of skilled carpenters and lumber, there was also a shortage of experienced wooden house construction contractors. Therefore, in Okinawa Prefecture, precut lumber mills provided contractors with other building materials in addition to lumber while also providing training and other services for carpenters. In Jeollanamdo, the local government initiated a robust support system that included educational programs for workers and a registration system for contractors. Thus, in Jeollanamdo and Okinawa, different actors supported the revitalization of wooden post and beam construction after its near disappearance following WWII.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 238484.

An early draft of this paper was presented at the “The 9th International Symposium on Architectural Interchanges in Asia.”

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tomoyuki Gondo

Tomoyuki Gondo is a Project Associate Professor at the graduate school of Faculty of Engineering at the University of Tokyo. He got Ph.D from the University of Tokyo. Before working at the University of Tokyo. He worked at Shibaura Institute of Technology and Tokyo Metropolitan University.

Sunwook Kim

Sunwook Kim is an associate professor at Civil Engineering and Architectural Design Course, Hachinohe College, Japan. He received Ph.D. degree in 2015 from the university of Tokyo. He worked for Korea Institute of Construction Safety Technology and Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties. His research interests are the transformation of local building production systems and technology.

References

- Ando, M., H. Ishikawa, K. Ohno, Y. Fujisawa, S. Funo and S. Matsudome. 1982. “Regional Wooden House Production System, Survey on 10 Regions (Part 1–5).” Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, 1451–1460. Tokyo: AIJ. (In Japanese).

- Bang, S. J., S. J. Lee, C. Y. Park and J. J. Lee. 2010. “Study of Establishing Wood Construction as Specialty Construction Business for Guaranteeing the Quality of Wood Structural Work in Korea.” Journal of Architecture and Structure, AIK 26 (11): 119–127.

- Chang, K. K. 2003. “Environment-friendly Wood House.” Review of Architecture and Building Science, AIK 37 (5): 33–36.

- Choi, I., and H. C. Cho. 1997. “A Comparative Study between Korean and Japanese Apartment Housing.” Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea, AIK 13 (5): 95–106.

- Fujisawa, Y., M. Ando, S. Fukao, S. Funo, S. Matsudome, T. Yashiro and T. Yoshida. 1983. “Study on Regional Housing Productive Organization (Part 1–6).” Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, 1551–1562. Tokyo: AIJ. (In Japanese).

- Fukushima, S., N. Ogura, Y. Yabiku and M. Yamazato. 1986. “Research on Carpenter’s Skill and Transmission in Okinawa.” Journal of the Housing Research Foundation 12: 385–394. Housing Research Institution. (In Japanese).

- Gondo, T., S. Kim, Y. Kim and H. Kanisawa. 2013. “Wooden House Production System in Recent Korea –wooden Post and Beam House Production after 2000s-.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ 78 (688): 1347–1354. doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.78.1347.

- Gondo, T., Y. Uehashi and S. Matsumura. 2010. “Wooden House Production System in Recent Okinawa Prefecture.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ 75 (647): 193–200. (In Japanese). doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.75.193.

- Jeon, B. H. 2009a. “Strategy for Establishing a New Hanok Archives.” Review of Architecture and Building Science, AIK 53 (9): 62–66.

- Jeon, B. H. 2009b. “Recent Situation and Problems toward the Spreading Market of New-hanok.” Journal of Achitectural History, KAAH 18 (5 (66)): 151–159. (In Korean).

- Kim, H. S. 1992. “Dialectical Development of Korean Wooden Architecture Aesthetics in Production History of Material Wood.” Review of Architecture and Building Science, AIK 36 (4): 20–32.

- Kim, J. M. 2006. “Development of Continual Plan Type of Korean Folk House.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIK 22 (3): 211–218.

- Kim, S. W., T. Gondo, Y. Kim, and H. Kanisawa. 2014. “Institutions and Housing Characteristics of Promotion Programs for Wooden Houses in Jeollanamdo, Korea, Study on Wooden House Production System in Happiness Village Project Part 1.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ 79 (697): 755–761. doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.79.755.

- Kinjo, H., and N. Ogura. 2018. “The Plan and Supply of the Standard Prefabricated House in Okinawa Postwar Reconstruction.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ 83 (744): 307–314. (In Japanese). doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.83.307.

- Kohatsu, S. 2005. Okinawa no Seizogyo Shinko Goju nen [The Fifty Year’s Development of Manufacturing Industry in Okinawa]. Okinawa: Takushinkai.

- Lee, B. T. 1992. “Wood Frame House Construction Technics.” Review of Architecture and Building Science, AIK 36 (4): 107–119.

- Michuhol Architect’s Office, Inc. 2011. Report on the Recoding of Traditional House in Korea 37. Daejeon: Daejeon Cultural Heritage Administration. (In Korean).

- Ministry of Land, Transport and Maritime Affairs of Korea Home Page. Publications. Accessed 10 March 2012. http://stat.mltm.go.kr

- Morita, D., T. Tokashiki, and N. Maeshiro. 1993. A Study on Okinawa’s Roof Tile Houses under Additional Loan Incentive, 33–36. Tokyo: Urban Housing Sciences. March. (In Japanese).

- No, C. B. 2001. “Introducing The Western Wooden Houses.” Unpublished master’s dissertation, f Dongkuk University, 20–32.

- Ogura, N., S. Fukushima, and H. Tonoshiro. 1988. “Study on the Characteristics of Building Production in Okinawan Cities: Part 1.” Production Network of Detatched Houses, Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, 767–768. Tokyo: AIJ. (In Japanese).

- Okinawa Prefecture. 1996. Regional Wooden House Supply Plan. Okinawa. (In Japanese).

- Park, B. S., S. H. Jung, D. J. Jung and J. W. Seo. 2005. Wood Species of Major Wooden Architectural Heritages, 34–40, 121–128. Seoul: National Recreation Forest Managment Office. 12.

- Park, C. G., S. Y. Gwon, M. Sakong and S.Y. Lee. 2012a. Policy for the Construction and Supply of Affordable Housing in Korea, 16–17. Sejong: KSP, KRIHS.

- Park, J. D., and J. Y. Kim. 2012b. “A Study on the Categorization System of the BIM-Library for Wooden Structure of the Korean Traditional Buildings.” Journal of Architecture and Structure, AIK 28 (5): 119–126.

- Park, M. J., W. J. Kim and K. J. Han. 1991. “Housing Market and Opportunities for Wood Frame Housing in Korea.” Journal of the Korean Wood Science and Technology, KSWST 19 (3): 45–52.

- Park, T. S. 1998. History of 50-year Forest Policy in Korea, 182–183. Seoul: Korea Forest Service.

- Research Institute of Architectural Thought. 1991. Nakamura-ke, the Typical Traditional House in Okinawa, “Architectural Culture of Southern Island, Okinawa” Separate Volumu of Jutaku Kenchiku. Vol. 40. Tokyo

- Song, I. H. 2006. The Definition and Concept Establishment of Hanok. Sejong: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. (In Korean).

- Sumikura, H., and S. Matsumura. 2011. “The Production Mechanism from the Viewpoint of Resource Selection and Arrangement: Study on Production System of Wooden Custom-built Housing by Small Housing Builders Part 2.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ 76 (659): 123–130. (In Japanese). doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.76.123.

- Suzuki S., J. Oyaizu, S. Hata, M. Hatsumi, R. Ariduka, H. Tomoda, S. Nagasawa, Y. Sone, Y. Kasashima and S. Kikuchi. 1986. “Comparative Study of Modernization Process of Houses in Japan and Korea.” Journal of the Housing Research Foundation 13: 349–362. Housing Research Institution. (In Japanese).

- Tanoue, K. 2003. “Study on Planning Margin for Establishing Dwelling Environment.” Doctoral thesis, University of Tokyo. (In Japanese).

- The Korean Society of Wood Science and Technology. 2010. Development of Standard Model of Hanok Using Korean Lumber. Daejeon: Korea Forest Service.

- The Okinawa Development Finance Corporation. 2017. Specification for Houses Loaned by the Okinawa Development Finance Corporation. Okinawa (In Japanese).

- Tomii, M., N. Suzuki, T. Shibuya and K. Kawabata. 1988. “Research on Houses of Chosen Housing Administration (1).” Journal of the Housing Research Foundation 15: 125–134. Housing Research Institution. (In Japanese).

- Wooden Home Builders Association of Japan. 2005. The Recent Situation of Pre-cut in Japan. Tokyo: Wooden Home Builders Association of Japan (In Japanese).

- Yoon, J. H. 2011. The Evolution of Hanok, 29–36. Anyang: AURI.