ABSTRACT

This study aims to propose a design method to promote the flexibility of a floorplan of an apartment building. Areas which permit the change of floorplan are assigned and demarcated in some part of a floorplan to evade the conjunction with physical structures of a building. These assigned areas for change can act as a mediator to extend the range of flexibility of floorplans. The former part of this study speculate the definition of design vocabularies composing the design methods of mass-housing flexibility. The flexibility of an apartment floorplan cannot but be restricted when compared to that of a detached house. Admitting this limitation, we could limit the aim of the flexibility design to accommodate a few design themes which residents would want most among diverse alternatives. The later part of the study examined variations of a Korean apartment plan. With four different design themes, the plan variations were sketched to demonstrate the process of the flexibility design.

1. Introduction

This study aims to propose a design method to promote the flexibility of a floorplan of an apartment building. As a design vocabulary for floor plan flexibility, areas that permit the change of floorplan are assigned and demarcated in some part of a floorplan to evade the conjunction with the physical structures of a building. These assigned areas for change can act as a mediator to extend the range of flexibility of floorplans. The former part of this study speculated the definition of design vocabularies composing the design methods of mass-housing flexibility. Especially the “margin”, which has not been focused, is ruminated and its typological variations are demonstrated. The flexibility of an apartment floorplan cannot but be restricted when compared to that of a detached house. Admitting this limitation, we could limit the aim of the flexibility design to accommodate a few design themes which the residents would want most among diverse alternatives.

This study proposes a design method for a flexible floorplan of an apartment. With a few design themes, presumed plan variations can be generated. To accommodate and guarantee the changes of physical elements, “sector margins” illustrated in detail can be used as a medium of coordination. To demonstrate the benefit of this proposal, the later part of this study examines a Korean apartment plan with the net area of 59. Plan variations are generated with two types of margins; one is the current margin and the other is the proposed margin.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. The definition of supports

N.J. Habraken proposed the concept of “Supports” as a kind of diagram which can be used as baselines in the design process of a mass housing. He regarded that the production of mass housing without any room for residents’ participation is an emergency measure adopted in the first place because of its productivity potential (Habraken Citation1999, 33). He argued that it is one of the natural human right to have a control over one’s own environment, thus, residents of mass housing should have the opportunity to actively participate in its design process.

To develop a design method and its process, he distinguished non-bearing infills from bearing structures and endowed controls over them to different relevant subjects. He applied his design method to the existing works to see its possibility to be developed into a holistic design theory. His method is well explained in the design studies and projects examples by Habraken (Citation2010) and Bosma et al. (Citation2000).

His mass housing design method is composed of void spaces such as zones, margins, and sectors. The dimensions of their forms correspond to each other (see ). The zones represent the spatial characteristics of the corresponding area, and the most prominent factor is a natural lighting condition (Bosma et al. Citation2000, 224). The zones are drawn in linear strips which parallel each other. The strips follow the perimeter of urban streets. The zone which is naturally sun-lighted is named as α zone or otherwise β zone.

On this zoning band, architectural components are arranged to form a configuration of spaces and a structural framework mediated with the pattern of zones. It is a different approach from modern architects in the early twentieth century that emphasized the independency of those two components. Between zones there is a margin in which residents can organize their own spatial configuration. The margin is a spare area where the adjacent space units can vary in size. Their physical components are movable to change the size.

Figure 1. Types of supports in the SAR methodology; Twin, Bijlmernner, and Longitudinal (Edited based on the original source: Habraken Citation2010. 132, 122, 152)

The zoning band appears to represent the functional differences of urban blocks in the 1960s. In the layout plan of Berlin-Hauptstad (1958) by Smithsons, there are three types of lattice strips resembling a slightly wrinkled tartan check in the 3 km diameter range (Bosma et al. Citation2000, 59; Banham Citation1966), with the interlocking of greens and vehicle roads. Each strip represents different functions endowed to it. Being interested in mediating gradual transitions between the public and the private, the Smithsons designed a zoning band to accommodate this characteristic transition of spaces. In the Golden Lane project (1952) and Robin Hood Garden (1972), they vertically expanded the band-shaped intermediate zone, which was called streets in the air. This prominent feature was used to decorate the elevation of many Korean apartments in the 1970s.

Aldo van Eyck paid attention to their transitional zoning band and imbued a metaphysical meaning to it. He termed the concept of “configurative design” which acted as a counter-form of human association for each and for all, in Forum (1962) (McCarter Citation2015, 118). In his works, the wind mill pattern of breathing squares repeatedly makes an interwoven pattern of threshold spaces. The Dutch Structuralists influenced by Saussure and Levi-Strauss considered an architectural design as a process of making relationships between components. Therefore, they developed their design language for open-ended building structures employing repeated building elements, which facilitated multiple use and further transformations of the elements.

Habraken (Citation2010) introduced this zoning band into an interior of a household unit. The SAR 65 design method is based on the zoning bands named, respectively. Each Greek letter from α to δ indicates the band of different environmental and social characteristics, and margins between the zones accommodate the formal change of space units anchored in the zones.

The efforts to generalize the formal relationships of spatial vocabularies continued after Habraken, however, their focus has been changed. In the 1990s, finding a robust form of a building was important to accommodate versatile changes of programs of blocks in an urban context (Bentley et al. Citation1990). In the 2000s, various types of buildings were represented in an abstract form of zones or strip patterns (Steadman Citation2003; Steadman and Mitchell Citation2010). The viewpoint that the natural lighting and ventilation conditions make the form of a building led the typological change was investigated. Since the mid-2000s, studies on floorplan flexibility were focused on the estimation of life-cycle cost and its feasibility, aiming to design buildings easy to repair, predict the capacity of functional changes of buildings, and suggest the amount of budget for renovation (Geraedts and Prins Citation2016; Geraedts et al. Citation2014). The physical components were categorized into multiple levels according to their life-cycle and itemized as indicators to analyse their correlation with the capacity of a building. This approach aimed to quantify the efficiency between the physical form of a building and its long-term cost. Yet, it was not appropriate for housing buildings which were typical in the construction method but varied widely in form.

2.2. The definition of a margin

When Habraken conceived of the concept of a margin as a design vocabulary, it was a spare area between zones accommodating the changes in the size of space units. It mediated two different zones and had both characters of them (Habraken Citation2010, 46–48). Because the sun-light zones were linear-shaped and parallel to the perimeter of its urban blocks, the margin between them was also linear and parallel. The changes of the space boundary imply that the size of a space is not restricted by its structural framework. The size of the space is determined first and then its boundary is enclosed with furniture and non-bearing walls. In margins, non-bearing walls were movably arranged for residents, and bearing walls were allocated not to interrupt their change.

The idea of an autonomously-changing space was mentioned by Kahn as well (Wiseman Citation2007). He referred to this autonomous space as Room and applied it to his design works, although his rooms were combined with physical structures. The predetermined sizes of spaces were coupled with the physical structures as a set. On the other hand, Habraken kept the autonomy of space units from the physical structures. He described their relationship as loosely connected to each other. The form of spaces was influenced by the structural framework, while the structural framework did not determine the form. The spatial buffer margin offered a gap between space units and the structural framework.

3. Another type of margins

The characteristics and functions of margins are circumstantial rather than intrinsic to the shape of supports.

3.1. Types of supports

The configuration of spaces and a structural framework can be categorized into the following types: (see ). All of them have parallel zones and margins between the zones. The “Twin” type has bearing walls perpendicular to longitudinal direction of the zones. The zones of “Bijlmernner” type are similar to the “Twin” type except for the structural elements of columns. The bearing walls of the “Longitudinal” type parallels with the zoning bands without structural elements in the zones, which allows freer relocation of the functional spaces relative to other two types (Habraken Citation2010, 160).

In the longitudinal supports, there is another type of margins besides the in-between one allowing the variations in the configuration of infills (see ), which illustrates the plan variations of longitudinal supports. With the absence of bearing walls in the zoning band, boundary infills for bedrooms can be relocated freely. The infill walls can be relocated in the area of small band of which the width accords with the exterior wall between windows. These areas are the margins of the supports that appear in the zoning bands not between them. Small margins included in a zoning band would be termed as sector margins.

Figure 2. The floorplan variations of the longitudinal type of supports and their sector margins (Edited based on the original source: Habraken Citation2010, 160)

3.2. The supports of Korean apartments

Supports in are those of European mass housing designed in the tradition of perimeter block housing with a court yard in the centre. The typical form of perimeter block housing has developed since the Middle Ages and went through the urbanization in the seventeenth century. Plots distributed to each entry became narrower to accommodate more entry facing the urban streets. The depth of plots became deeper to secure the usable areas. Residential blocks in Paris were architecturalized in a similar way under the influence of Latin culture. In the twentieth century, the perimeter block housing was built in Germany and the Netherlands developed into the modernized version. The urban plan of Amsterdam south (1915) is one of the examples. Berlage planned a semi-public park and green areas inside the block to afford amenity space for pedestrians in the urban context (Sohn Citation2000, 287).

The major form of Korean apartments is different from the European perimeter block housing. The building does not enclose a block and the width of a building is limited by law for air circulation and natural lighting. With the development of construction industry of apartments, the form of apartment buildings has continued to change, while its floor plan has hardly been influenced by the block size or shape.

Although the majority of Korean apartments are built in high-rise reinforced concrete structure, the lighting condition of interior spaces resembles the Korean traditional housing, Hanok, rather than the European perimeter block housing (Kim Citation2016, 116). Koreans prefer houses facing the south due to the advantages in natural lighting and air circulation. Floor plans of the Korean apartments have developed to meet this environmental conditions similar to Hanok for a half century.

3.3. The margins in Korean apartments

Kim (Citation2016) drew the margins of apartments in the second development of Dongtan New Town. Dongtan New Town is one of the representative urban development projects in Korea, which was planned as a site for housing development in 2001, with the apartments presold in 2004 and 2012. It was the largest site for housing development in Gyeonggi province for over 15 years. The selected apartment plan for the study is the 84㎡-plan, which occupied the majority of the households (47%, 5285 households).

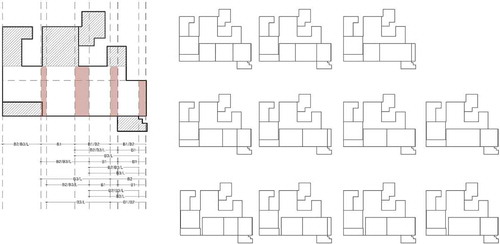

A sector in the SAR methodology indicates a vacant area without any physical element that could hinder spatial deployments (Habraken Citation2010, 60). The possible number of plan variations produced from a supports is influenced by the bay of the vacant area. Arranging the functional programs on sectors, one can generate and count the number of plan variations. This is the most direct method to check the flexibility of a support, named as sector analysis (Habraken Citation2010, 60–83).

First, for the sector analysis, the determination of fixed elements which do not change their forms was conducted. There were a few non-changeable elements by law such as bearing walls, bearing columns, and fire escape rooms. Also, exterior windows, the relevant fixtures, and their pipe ducts, for example, kitchen and air-conditioning plant room, were designated as fixed elements.

Second, the size of functional spaces was defined. Two types of data are shown in . One is the statistics of room-sizes of Korean apartments since the 1970s, and the other is the drawing dimensions of each functional space equipped with available furniture layouts. The second data was necessary to ensure that the dimensions of the rooms in the statistics were applicable to new design works of planning household units. Each functional space had a range of dimensions from minimum to maximum; the minimum dimensions were mainly chosen from the second data to exclude small sizes which do not accommodate reasonable layouts of furniture. The maximum dimensions were chosen from the first statistical data to include the diversity of plans. Most of the functional spaces had the minimum dimensions in the statistics, because the rooms were actually in use and did not allow the available layouts for their use.

Table 1. Sizes of functional spaces in the 84㎡-apartments (units: mm)

However, living room space was an exception. The minimum dimensions of living rooms in the statistics were larger than the furniture layouts. Given the Koreans’ preference of a large living room, the minimum dimensions in the statistics were chosen instead of the furniture layouts. This is a matter of a decision whether to consider an unfamiliarly small living room accommodating a functional layout of the minimal furniture as a Korean-style living room. The dimensions of a house means more than their functions. Rather than the functional dimensions of exceptions, general dimensions, in spite of being entirely functional, were chosen to define the space units of a house. The general idea of the dimensions of space units in a house can be understood in the cultural contexts.

Figure 3. Generation of floorplan alternatives (Edited based on the original source: Hwaseong City Citation2012)

There were more rules to follow to generate floorplan alternatives as follows: 1) access route, 2) number of rooms, 3) hierarchy among rooms, 4) location of rooms, and 5) size of windows. The rule on the access route is that all the bedrooms and living rooms should be able to be accessed directly from an entrance and not be hindered by another bedroom. For example, in , any room allocated in the sector 6 can be accessed through a room of the sector 4. Thus, it cannot but be an affiliated room to the sector 4. If the sector 4 is occupied by a living room and the sector 6 is large enough to accommodate a bedroom, then a room in the sector 6 can be an independent room. The rule on the number of rooms is that a non-bedroom space is allocated once under the assumption of one household per a unit. Otherwise, the floorplan variations include only one living room and one dining room.

The rule on the hierarchy among rooms is that the largest bedroom is considered as a master room, and others are planned as a single room or a double room. The regulations on window size are not applied. Exterior openings for windows determine the adequateness for the predetermined functions so that every dimension of the exterior openings indicates its function of the corresponding space in the original floorplan. Nevertheless, it was neglected to generate floorplan alternatives in this study.

Figure 4. The variations of 22 floorplans (Edited based on the original source: Hwaseong City Citation2012)

The margins where the boundaries of space units vary are shown in the floorplan variations (). The shape of margins can be categorized into the following two types: the longitudinal band and transversal band. In the peripheral zone inside the southern exterior bearing wall, the longitudinal bands appear where the non-bearing walls are moveable. Moreover, the transversal bands appear where the master room size can be changeable. The transversal band is included in 15 floorplans among 22 samples, and the longitudinal bands are drawn in every samples. In case a dress room is partitioned with bearing walls restricting the changeability of the room size, the transversal band does not appear.

The margins in the sample floorplans have the width of 600 ~ 1200 mm and a tendency to be deployed parallel according to the southern lighting zone, which is contrast to the configuration of a margin in Twin supports in . Compared to the three supports of Habraken margins of Korean apartments are similar to the longitudinal supports, because the supports of Korean apartments do not have fixed elements in the southern zone to supply wide open sectors passing through them (see ).

Figure 5. The pattern of sector margins of Korean apartments (Edited based on the original source: Hwaseong City Citation2012)

3.4. The pattern of margins

The 22 floorplans of samples are same in the floor area, and all of them have four rooms in the southern lighting zone. This kind of floorplans is called as 84 four bay plan in Korea. The depth of floorplans is approximately 12 m without much deviation. Every bedroom is deployed in the southern lighting zone and a dress room, dining room, and utility room are located at the northern side of a unit. The 22 floorplans of samples are also similar in their configurations of functional spaces.

As represented in the SAR method, the diagram of these floorplans is a simple rectangle with two southern and northern lighting zones. Between them, there is no β zone or a margin. The supports diagram of SAR explains the similarity of spatial composition grouping spaces into a higher level. The floorplans of a similar supports diagram can be considered to have the same spatial composition. According to their spatial characters, the supports diagram represents the similarity of the spatial compositions regardless of the physical forms of architectural plans.

On the other hand, to generate the floorplan alternatives is an attempt to find the differences of the latency of each support in its spatial compositions. In other words, it confirms the possibility of variations in the spatial compositions of each support. With the functional definition of spatial units which are autonomous from the physical forms of architectural elements, the possibility of morphology can be visualized. It is interesting that, even though the sizes and the locations of margins are different, the overall configuration or the pattern of their deployment is similar. Drawing margins performed to give an overview of the possible variations reaffirms the typological similarity ().

The 22 unit plans in Dongtan have a similarity in their configuration of margins and their result of plan variations: It is possible to change the number of bedrooms, but the spatial relation of the living room, kitchen, and bedrooms hardly change.

4. A case study of a flexible floorplan design

Habraken’s open housing theory is meaningful to let residents participate in the design and leave the space of autonomy and transformation. This case study starts from the assumption that the compositional difference of spaces for transformation, margins would cause a difference in the result of plan variations. And the plan variations of a floorplan were expected to accompany 3 ~ 4 kinds of lifestyles which are generally demanded in the housing market.

4.1. Material

A floorplan for the case study was that of an experimental building for long-life housing by Land & Housing Institute. The building was scheduled to be built in 2019 and a design competition was held in September 2018 for the ideas of unit flexibility. The net area of the unit plan is 59㎡ which is smaller than the cases of Dongtan New Town, but the spatial structure of them are similar in the two layers of lighting zones and the four southern bedrooms.

4.2. Method

Plan variations are generated with two types of margins; one is the current longitudinal sector margins which is explained in previous section, and the other is the proposed variations of margins. And the characters of the plan variations will be compared at the end of this section. The following deals with the design process of planning the proposed margins.

4.3. Design Process of a floorplan flexibility

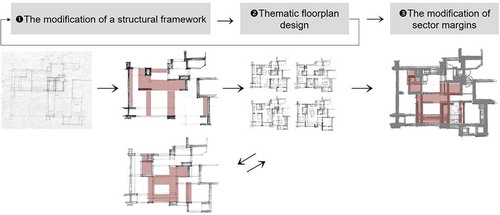

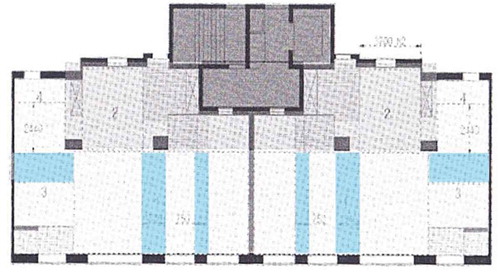

The range of floorplan flexibility can be extended if supports can take in several floorplans designed for different themes. This approach is reasonable from a viewpoint that designers of apartment floorplans have to pursuit an optimized solution for variations under the limited range of freedom. The cases in this study show the flexible floorplans of 59㎡-Korean apartments. The design process of the flexible floorplan is as follows (see ).

First, the floorplan variations with the margins for formative changes were drawn. These areas should not be too large to handle the construction cost for remodelling and simultaneously should be extended to encompass the available changes. All of the results of formative changes should meet the needs of individual residents. The aim of the changes should be clear to become a designer’s design themes.

Four design themes of floorplan variations were planned. In every plan, the locations of walls were different, which led to the adjustment of the lines of bearing walls of the previous margins. Based on the modified structural framework, the four floorplans were set again to examine their fitness. After two modifications of floorplan and structural framework, the design of a flexible floorplan was completed.

Plans in are the plan variations of a unit of 59m2-apartment with four different design themes. The presumed design themes included a three-bedroom type, home-office type, detachable type, and a courtyard type. The three-bedroom type represented a typical Korean apartment plan. The home-office type plan had a separate entry for an office located at the northern side of a unit with kitchen. A bathroom for the office was placed next to a master bedroom so that the wall of the bathroom could not be enclosed with bearing walls to make it accessible to the office too. The detachable type plan housed two households with separate entries, bathrooms, and kitchens. The original master bathroom was slightly moved to the periphery to make public access easier. The courtyard type plan was planned with a centre where a dining and living room converged, and an adjacent bedroom with a floated wooden floor, maru, was open to the centre. Another floated wooden floor, toenmaru surrounded the court area and provided a space for a sitting or leaning position instead of sofas.

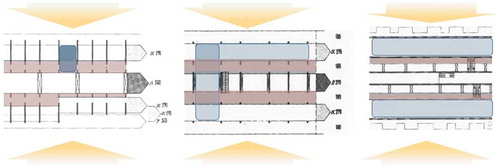

4.4. Redrawing sector margins

Similar to the sector margins in the longitudinal supports in , the four different plans were explored, and the sector margins were drawn in the area where the formative changes of physical elements occurred (see ). To enhance the readability, the parts of were simplified by removing movable furniture, and then each plan was coloured with red, green, purple, and blue. The coloured plans were overlaid serially using layer blending option to highlight the non-changeable area. The highlighted area changed its colour into light blue, light green, and yellow. Yellow indicated the non-changeable area.

Figure 8. Redrawing sector margins: physical elements overlapped in four floor plans are highlighted in yellow, which do not need to be flexible elements. On the other hand, elements with its original colour are overshadowed with grey areas, which need to be reserved not to be hindered with bearing walls for flexibility

The area with formative changes of the physical elements had its original colour; these areas scattered like a parallel pattern of margins in . However, the margins in could be categorized according to the rationale of generation.

First, there were three longitudinal margins with moveable non-bearing walls. These were identical to the linear sector margins in . Second, there were two transversal sector margins. One of them was in the middle of a plan, reflecting the size of a living room varying with the changes of the composition of a living room and dining room. The other transversal margin in the southern end of the zone also reflected the size of a living room varying with the size of a balcony. Third, there were rectangular-shaped sector margins where the sizes and the locations of bathrooms varied. Last, kitchen furniture, entry doors, utility room doors, and splits of floor levels made other forms of variations.

4.5. Result

To illustrate the diversity of floorplans, plan variations are generated with two types of margins: parallel longitudinal margins and various rectangular sector margins. The floorplan had four linear margins in the southern zone. presents the schematic plan variations with the original linear margins. The non-bearing walls located at the left or right edge of the four margins yield eleven variations. However, the wall location is freely moveable in the margins so that the possible number of variations increases, even though the spatial organizations of floorplans are not different as much as the possible number of variations. The only difference is the number of rooms.

On the other hand, the plans in are different in the number of households and the layouts of kitchens and dress rooms. The rectangular margins in the northern zone change the pathway to bedrooms so that the character of an interior space changes accordingly.

5. Discussion

5.1. The necessity of redrawing margins

Like water and oil, margins and fixed elements of supports cannot be mixed with each other. Based on the provisional baselines for these two, floorplans with different design themes were planned. The areas with formative changes were determined first, and then plan variations were designed. In this regard, the process of drawing margins was not purely inductive.

The area where the formative changes occurred could be roughly predetermined because the form of the fixed elements of supports was generally preconditioned by its typical solution. The constraints that determined the form of the fixed elements are as follows: the minimum section of bearing walls should be deployed within a maximum span. Also, bearing walls were better to be set as the walls enclosing pipe ducts to maximize usable floor area. Furthermore, non-bearing walls did not need to be separate channels if supported by bearing walls. To deal with the issues of the fixed elements and margins and the relevant constraints, optimizing balance between the fixed elements and margins rather than minimizing either of them was required.

The margins were reserved at their locations prior to having concrete forms. However, the process of confirming the exact shapes of them was necessary for overlapping the plan variations. If a single person designed all the plan variations, he or she could make different forms deviating from the predetermined baselines. In case of a collaborative work involving multiple designers, such deviations would increase. To predict and control the extension of formative changes, the process of drawing margins is necessary.

5.2. The pattern of sector margins

The current Korean apartments have linear margins in the longitudinal and transversal directions. The margins in are different from the current one in that a new type of margin in a rectangular shape appears and the transversal margin is relocated to the centre of a unit and merges with the longitudinal direction to form a pattern. Otherwise, the formative type of margins increased and a hierarchical level also increased in their configurations. In the current apartments, the margins are dispersed in a zone, while, in the plan in , the margins are grouped to form their own shapes. The pattern of the margins surrounding a living room represents the possibility of the bidirectional changes of forms in the area.

The transversal margins in the centre of a unit transform the character of the pathway passing through a living room. In the plan of the courtyard type, a hall way is shortened and the pathway surrounds a dining table at the centre of a large living room. Entries to adjacent rooms can exist in the middle of a roundabout. In Korea, it is common that sliding doors and a floated wooden floor face a semi-public space, which resembles the structure of Hanok with anchae, a room for a housewife, and daechung, a wooden floor, facing its courtyard (Yoon Citation2011). This kind of living room is not a place to simply pass by but a place where family members gather together.

6. Conclusion

The process of mass housing design involves various stakeholders, and forms of apartment buildings need to be changed according to their lifecycle. However, when it comes to new attempts in formative renovations of buildings, it is hard to make consensus among diverse stakeholders with different points of view and interests. To persuade them, designers of mass housing projects usually rely on good precedents rather than creating a whole new plan, which, consequently, results in conservative plans.

This dilemma is a key issue in mass housing design. Architectural design is not a process of finding a unique solution but a process of making formative variations in given conditions and constraints. In mass housing, variations constantly occur in a lifecycle of a building due to numerous residents. Therefore, the most important issue of mass housing design is to manage the needs of formative changes suggested by various stakeholders. The aim of mass housing design should not be finding a single fixed form but finding a way of extending or managing the possibilities of formative variations. Planning sector margins providing floorplan variations can be an excellent compromising solution.

Although it is impossible to predict all the possibilities of floorplan variations, drawing sector margins can visually help the process of accommodating the needs of design themes suggested by the residents; in this process, planning sector margins restricts the extent of variations. However, it assures the minimum extent for formative changes and can leave a room for further changes.

Sector margins of this study offered more diverse configurations of margins as the comparison of demonstrates. Margins in are different from that of the precedent diagram of SAR. They deploy several types of margins: the longitudinal, transversal, and rectangular types implying concrete formative changes and extending the possibilities of floorplan compositions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marie Kim

Marie Kim is a researcher in Department of Archictecture of Ewha Womans University.

Chaeshin Yoon

Chaeshin Yoon is a professor in Department of Archictecture of Ewha Womans University.

References

- Banham, R. 1966. The New Brutalism Ethic or Aesthetic?, 83–84. London: Architectural Press.

- Bentley, I., et al. 1990. Responsive Environments; a Manual for Designers. Translated by Kim, K. Seoul: Kukje books.

- Bosma, K., et al. 2000. Housing for the Millions. Belgium: NAi Publishers.

- Geraedts, R., et al. 2014. “Adaptive Capacity of Buildings; a Determination Method to Promote Flexible and Sustainable Construction.” In UIA 2014 Architecture Otherwhere, edited by A. Osman, G. Bruyns, and C. Aigbavboa. Durban.

- Geraedts, R., and M. Prins 2016. “FLEX 3.0; An Instrument to Formulate the Demand for and Assessing the Supply of the Adaptive Capacity of Buildings.” CIB World Building Congress 2016, Intelligent Built Environment for Life May 30-June 3, 2016, Tempere, Finland

- Habraken, N. J. 1999. Supports. U.K: International Press.

- Habraken, N. J. 2010. Themes and Variations. Translated by C. Yoon, et al. Seoul: CA Press.

- Hwaseong City, Gyeonggido, Korea. 2012. The Business Approval of the Second Development of Dongtan New Town. Hwaseong, Kyunggido, Republic of Korea.

- Kim, M. 2016. “A Study on the Future Direction of Flexibility in Korean Apartments”, PhD diss., Ewha Womans University.

- McCarter, R. 2015. Aldo Van Eyck. New Haven, NY: Yale University Press.

- Sohn, S.-K. 2000. A History of Urban Housing. Seoul: Youlhwadang Publisher.

- Steadman, P. 2003. “How Day-lighting Constrains Access”. 4th International Space Syntax Symposium, London.

- Steadman, P., and L. J. Mitchell. 2010. “Architectural Morphospace: Mapping Worlds of Built Forms.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 37: 197–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/b35102t.

- Wiseman, C. 2007. Louis I. Kahn, beyond Time and Style. New York, NY: W.W.Norton & Company.

- Yoon, C. 2011. The Evolution of Hanok. Anyang, KR: Architecture & Urban Research Institute.