ABSTRACT

In 1975, the Japanese government introduced Important Preservation Districts as a new category of cultural properties to preserve, enabling a preservation workflow that requires a balance between the establishment of designation criteria and decision-making by the central government and a legal framework that guarantees strong landowner rights. This paper explores how different local management models sought to establish such a balance, within a context of strong community self-organisation that pre-dates 1975. In addition, this paper aims to explain the role of scholars as independent subsidiary agents for preservation management as well as the outcomes of each management model. It concludes that the management style has evolved from a purely top-down model to one in which there is cooperation between top-down and horizontal structures, in order to respond to an increasingly broader definition of the values that are maintained via town preservation. Such evolution is rooted in the specificities of the Japanese approach to urban preservation, which might contribute to the exploration of new solutions in an international context. Finally, the study highlights areas for future improvement, such as the integration of scholarly knowledge into management practices.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research context

The category of Important Preservation Districts for Groups of Traditional Buildings was introduced in Japanese legislation in the 1975 amendment to the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties under the official name jūyō dentōteki kenzōbutsugun hozon chiku. Also known as denken chiku (Ye et al. Citation1998; Mori Citation2014) or jū-denken chiku (Saio and Terao Citation2014), the shortened term found in English texts is Important Preservation Districts, or IPDs (Hohn Citation1997). This was the first national law to confer the category of ‘cultural property’ on districts defined by municipalities and thereby provide access to monetary grants from the Agency for Cultural Affairs (hereafter, the ACA). The preservation of values present in old urban structures and concerns about modern urban planning affecting them appeared in Japan at the same time as in Europe (Bandarin and Van Oers Citation2012) and the USA (Jacobs Citation1992), and Japanese legislation on town preservation is contemporary to the first laws in European countries (France in 1962, the UK in 1967, Italy in 1973). However, the Japanese approach to the matter has consistently been described as specific to Japan.

When comparing the Japanese approach to urban preservation planning and management to international standards, two specificities have been consistently highlighted by professionals. First, Japanese urban planning at the level of local government is described as weak towards both the central government and private proprietors. The central government has controlled urban planning and building since the enactment of the first City Planning Law of 1919 and the Building Standards Law of 1950. Barrett and Therivel (Citation1991) described planning policies in Japan as highly centralised and often dependent on ministries with conflicting interests. Around the time that town preservation became an issue of public concern in Japan, the central government delegated planning powers through the new City Planning Law of 1968 and the 1970 amendment to the Building Standards Law; however, as Sorensen (Citation2002) pointed out, the central government maintained dominance through legal and financial control. In addition, these laws introduced zoning categories with regulations in terms of land use and floor-area ratios that proved unsuitable for the standards of traditional areas (Koide Citation1999). Regarding proprietors, regulation over private property was considered an agency-delegated function (i.e., a function exclusive to the central government that local governments perform under supervision) by the 1952 amendment to the Local Autonomy Law. Therefore, local ordinances could not regulate private land (Sanbe Citation1999) until agency delegation ended and the City Planning Law was amended accordingly in 2000 (Ishida Citation2000). Thus, local governments tended to use manuals (shidō yōkō) more often than ordinances (jōrei) as their preferred tool for management during the 1970s and 1980s (Uchiumi Citation1999). Such manuals were meant for guidance and could not constitute a norm, so their contents had to be negotiated with landowners and tenants.

Consequently, local governments in Japan could not rely solely on planning and detailed ordinances for town preservation. Instead, they focused on the management of specific preservation efforts for certain structures, always seeking consensus with landowners and local citizens. This is the origin of the second specificity of Japanese preservation planning and the major focus of this paper: preservation has often been achieved through formal and informal interactions between different governmental, citizen-based and scholarly agents. The interactions between agents that took place in the period between 1950 and 1975 have been studied to explain the origin of the IPD category. Mori (Citation2014) explained the process that led to the implementation of a nationwide town preservation system as being driven by scholars first and the government later. The Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties, which came into force in 1950, provided the chance to preserve traditional dwelling architecture, and scholars pushed to extend protection to entire sites with such dwelling types. The government would then take over the debate, defining the Areas of Environmental Preservation around historic sites and founding the ACA in 1968 to lead the research and evaluation process that culminated in the 1975 amendment. However, Kariya (Citation2011) described the process that led to the implementation of the IPD category as arising from civil protests during the 1960s against the construction of disruptive elements such as high-speed railroads and high-rise buildings. These protests were followed by ground-breaking community-led urban operations such as the acquisition of the land surrounding Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine in Kamakura in 1964, and by anti-establishment movements in defence of existing living environments that, according to Satoh (Citation2019), are the origin of machizukuri (a term to describe a heterogeneous group of bottom-up initiatives to improve living environments). Citizens in depopulated areas also started valuating local vernacular architecture, after some such architectural works were moved from their location to various open-air museums, called minkaen. The success of such museums motivated citizen groups to preserve their dwellings as possible sources of revenue from cultural tourism. Finally, research on specific cases – such as Siegenthaler’s (Citation2003) study of Tsumagojuku – showcase how different narratives of when, how and by whom the movement to preserve the site was promoted co-exist, with each of those narratives having some basis.

Regardless of who launched the series of events that led to the passage of the 1975 amendment, it is clear that the application of this law in the IPDs necessitated the participation of governmental, citizen-based and academic agents at different levels. On the one hand, while the law as it stands in 2021 dictates that any IPD within a City Planning Area must be regulated by the local town plan and a local preservation ordinance, the ACA is still as exclusively in charge of designations and monetary grants as it was in 1975. On the other hand, management at a local level also requires collaboration with the local community. In addition, while scholars were heavily involved in the first initiatives for preservation and are now seen as indispensable advisors, it remains debatable whether their influence as agents is as strong as that of the government or local community groups.

Previous studies mention the evolution from top-down management models to collaborative management between the government and communities (Saio and Terao Citation2014), but there remains much to learn about the specifics of such collaborative management models and the agents participating in management (i.e., who did what, for what reason and to what effect) to explain precisely how that evolution occurred. In addition, it is also necessary to understand the response of such management models to what Choay (Citation2007) called the expansion of the concept of heritage in its typological, geographical and chronological range, which occurred alongside the expansion of values attributed to the environmental, social and immaterial aspects of urban heritage. In an international context, paradigms such as the Historic Urban Landscape have been formulated as a response that can deal with such complex values while addressing the interaction between an area’s historic fabric and new urban development (Bandarin and Van Oers Citation2012). However, some studies reflect on how such paradigms have raised new questions but also new problems when put together with current models of government which prioritise the scientific or political over the social (Azpeitia Santander, Azkarate Garai-Olaun, and De la Fuente Arana Citation2018). In the Japanese case, although earlier studies have addressed how the ACA designation criteria became increasingly complex over time (Alvarez Citation2017), how local management models evolved in relation to the evolution of values and criteria determined by the ACA remains unexplained.

1.2. Goals and methodology

Considering the above, this study aims to shed light on three topics related to Important Preservation Districts: the context, mechanisms and outcomes of management processes. First, regarding context, the study describes the evolution of the agents participating in town preservation and the goals to be achieved through the preservation of IPDs. In this paper, ‘agent’ refers to any individual or organisation (governmental, citizen-based or other) that plays an active role in the management and execution of works on structures or public infrastructures and actions related to the preservation of an IPD. To this end, it is also necessary to clarify whether scholars constitute independent agents with their own goals, or whether their role is subsidiary to that of local governments. Second, regarding mechanisms, the study aims to clarify the distribution of tasks among agents as well as their means of communication and coordination. Correspondingly, this paper attempts to explain how values such as new economic initiatives from tourism or the incorporation of community as a preservation-worthy value are applied to specific projects or policies. Third, considering the two previous topics, this study aims to explain the outcomes of the management models for each district and discuss the current state of both the IPDs and agent groups to discern the potential challenges they may face in the near future.

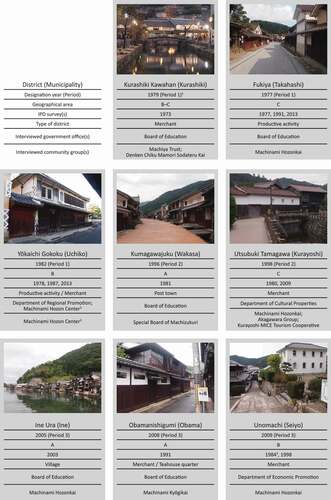

For these purposes, this study was divided into three stages. The first stage consisted of an extensive examination of different regions of Japan to verify the existence of agents and social structures related to town preservation. This provided the information to make further selections for detailed surveying. The second stage was a document search limited to eight districts with verified social networks that were totally or partially willing to collaborate in the survey. This stage included the study of past survey reports and preservation plans as well as publications by scholars, local governments, community groups and the press in order to understand the topics included in the preservation activities and the values that were the focus of preservation. The number of selected districts corresponds to the above-mentioned need for detailed research on management processes and allows for the establishment of comparisons that go beyond the mere presentation of a case study and help grasp the entire picture of the IPD system. The criteria for the selection of districts include their designation in different time periods and their location in specific geographical regions, in order to compare the different dynamics within and between networks in districts in different locations and periods. Based on existing literature, this study divided the history of the IPD system into 3 periods: period 1 (1975–1990), a period of early implementation of the IPD system; period 2 (1990–2004), as the year 1990 marked the beginning of a new period for the development of local rights (Sorensen Citation2007) and national policies regarding IPDs (Hohn Citation1997); and period 3 (2004–2020), which is defined by an expansion of preservation towards the humanised landscape as a result of the Landscape Law of 2004 (Alvarez Citation2017). Three geographical areas were also selected () area A, which contains recent IPD designations; area B, which combines early and recent IPD designations; and area C, which contains early-designated districts.

The third stage consisted of interviews of government agent representatives (i.e., civil servants and internal or external scholars) and community groups (). Interviews were semi-structured, with a list of topics regarding context, mechanisms and outcomes () that was explained to interviewees in advance. Due to the comparative evaluation-process nature of this research, where new topics were raised in different cases (such as when discussing foreseen or unforeseen outcomes of management actions), some iterations were necessary to verify whether the new topics raised were scalable or not. A coding process was required to compare the qualitative data across all the cases. Finally, outcomes were verified through an in-situ inspection of the preserved districts, considering the same topics regarding outcomes as in .

2. Findings

2.1. Agents participating in preservation management and their goals for preservation

This section explains the context in which each district defined its preservation goals, as stated in its research reports and preservation plans. It then enumerates the agents who defined such goals, considering their nature (governmental, citizen-based or scholarly) and their composition (individuals or groups). For the definition of agents, two periods are considered: before the district’s designation as an IPD and from the designation to the present time. Previous research has shown that some designation processes took over a decade (Kobayashi and Kawakami Citation2003), and the involvement of agents predates the creation of the IPD system itself.

Previous research suggests that the first preservation initiatives in the 1960s had two goals: the extension of protection from single buildings to groups of buildings (kenzōbutsugun), supported by architects and scholars (Hohn Citation1997; Henrichsen Citation1998; Mori Citation2014), and the above-mentioned reaction of citizens condemning environmental destruction and supporting old townscapes as tourism assets. The first goal is reflected by the term kenzōbutsugun, which was adopted by the ACA to define the IPD category. In this study, the stated goals of the three earliest-designated districts focus on the value of structures as cultural properties and oppose their destruction or replacement by modern structures (). It is only after 1990 that districts also began to state goals related to the comprehensive preservation of the living environment, as preservation of communities became considered nationwide as a key factor for town preservation.

Table 1. Agents and goals at the beginning of preservation actions

The advocacy for preservation in early districts was led by one or a few individuals, either local or coming from outside the district, who belonged to academia or the local government (). Kurashiki had the Ōhara family as its patrons as well as Kurashiki Toshibi Kyōkai, a group of experts in folk studies founded in 1949 (Kurashiki Toshibi Kyōkai, ed Citation1990). They would lay the groundwork for determining the future protected urban landscape, called bikan chiku (a term coined in the City Planning Law of 1919, originally meant for the design of new urban centres). Uchiko had its leader figure in Okada Fumiyoshi, who at the time was a public worker in the Tourism Department of the local government. Fukiya was studied by architect Takahara Ichirō, whose research resulted in the 1977 IPD survey, and its preservation was proposed by Okayama Prefecture (Nariwa Town Board of Education Citation1977). Meanwhile, in Kumagawajuku, researcher Fukui Uyō discovered the district worth preservation and unsuccessfully pushed for candidacy to designation as an IPD in 1975 (Kaminaka Town Citation1982; Wakasa Kumagawajuku Machizukuri Tokubetsu Iinkai Citation2007). Thus, scholars led many of the early preservation efforts as independent agents.

However, at the time of designation of the rest of the districts, cases in which scholars took a leading role were in the minority and were met with local opposition. In most cases, scholars were hired by local governments to conduct research when needed, resulting in scholars being external advisers who had contact with the district only during the execution of the research. During the 1990s and thereafter, scholars would also be hired by community groups – or community members would establish research groups themselves – to research topics related to their living environment. All in all, it is not suitable to talk about scholars as independent agents after the IPD category was defined by law, but rather as external advisors working for either the local government or community.

Therefore, the agents that act independently are government or citizen agents. Regarding the organisation of local government as an agent – according to the ACA (Citation2002), the Board of Education of each municipality is in charge of the management and coordination of the preservation plan, including preservation work on structures, under the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties. Meanwhile, the IPDs on urban soil are delimited by the local government (without specifying the office in charge) in their urban planning as in any other district (old or new), under the City Planning Law. As for the relation between offices in the same municipality, previous studies have clarified that not only do the office in charge of Town Planning and the Board of Education act independently regarding preservation, but they also depend on national programs administered by different ministries (Hohn Citation1997). As a result, a district designated by the ACA as an IPD might or might not match with the district division assigned by the municipal Office of Town Planning.

In the studied districts, the Board of Education, or a specific Office for Cultural Properties within the Board, is in charge of registering and preserving any cultural property in the town, with a few exceptions (). In Uchiko, Machinami Hozon Centre was established in 2000 with former workers of the Board of Education, Tourism Office and Office for Regional Promotion in order to solve problems related to the above-mentioned task division. Likewise, the Office for the Traditional District in Unomachi is within the Department of Regional Promotion, purportedly because of their proximity – both geographically and ideologically – to Uchiko. In both cases, these specifically created offices have competence only inside the IPD. In Kurashiki, the Office of Town Planning is in charge of the planning and management of urban infrastructure in the bikan chiku (which is larger than the area designated by the ACA as an IPD), while the Kurashiki Tourism Office is in charge of tourism information and the management of tourism facilities.

Table 2. Governmental offices and community groups involved in town preservation

As for citizen movements with an active role in preservation management, all studied districts have specific community groups that are regarded as citizen representatives by the local government and are consulted on the majority of topics related to the IPD. The term ‘community’ has been criticised as being excluding and less democratic than ‘citizenship’ (Hertz Citation2015), and others have used more open terms such as ‘community of urban users’ (Bandarin and Van Oers Citation2012). However, research on the Japanese case has revealed the long tradition of closed community groups circumscribed to neighbourhoods which worked under a ‘desired appearance of unanimity’ (Steiner Citation1965, 211) and are thus exclusive and not internally democratic. Sorensen (Citation2002, 211) stated that these groups ‘served primarily as a means of communicating information and demands downwards from local government to the people’ until the 1960s, when they started to make demands themselves. This changed after the passage of the Non-Profit Organisation (NPO) Law in 1998, which conferred NPO status to community groups and in turn resulted in new, less-exclusive trust-like groups (Takao Citation2006). Takao states that local governments favoured the institutionalised participation of citizens by providing such groups with spaces for political participation.

In seven of the studied districts, these groups were founded in the 1990s or the 2000s and their composition is different from that of early citizen movements that appeared in some districts during the 1960s and 1970s, founded either through the initiative of the local government (Sanada Citation2011) or by the above-mentioned scholar leaders along with local inhabitants interested in the preservation of the town (Kurashiki Toshibi Kyōkai, ed Citation1990; Enkakushi Henshū Iinkai Citation2001; Unomachi Machinami Hozonkai, ed Citation2015). Most districts have one community group, which is usually denominated Machinami Hozonkai (‘town preservation assembly’). They claim to gather people living, owning property and, in some cases, doing business within the district, but involvement in the groups is open and non-compulsory. Kurashiki has two groups operating in different quarters of the district and with different goals: Denken Chiku Mamori Sodateru Kai and Machiya Trust. In Kurayoshi, besides the Machinami Hozonkai run by residents, the local chamber of commerce has also run since 1997 the Akagawara Company and Akagawara Group, which work primarily on the adaptive reuse of structures. Uchiko uses a different approach, called ‘government-led machizukuri’ (Suzuki Citation2009), in which the aforementioned Machinami Hozon Centre is in charge of the local Machinami Hozonkai and creates and dissolves citizen groups for specific purposes in successive machizukuri plans every few years. A split approach is used in Unomachi: their Machinami Hozonkai is led by local citizens, but their office is officially located in local government offices inside the IPD. As in Uchiko, the local government is involved in the creation of networks and groups when necessary.

Despite the similar composition of the groups, differences can be found in their foundational motivations (). Community groups from early-designated districts focused on two goals: 1) valuation of and awareness towards structures and 2) cultural tourism as an important new economic activity. After 1990, groups worked on the creation of community networks centred around common safety and economic activities that benefit local daily life, while tourism might or might not have been included among such activities. In the more recently designated districts, the living environment – including the surrounding territory, natural resources and immaterial culture of districts – are given priority as necessary supports of local life, and their communities are more centred on self-sufficiency and a locally oriented economy. Some communities delayed their IPD designation until the local government approach evolved to suit their needs.

Table 3. Foundational motivations of existing community groups

In conclusion, management of preservation was primarily in the hands of local governments from 1975 to 1990, but local communities became increasingly involved in the 1990s once preservation began to consider their needs and values as goals. These values comprised their entire living environment, including the territory and immaterial culture, which became the main concern in the districts designated after 2004. However, as neither immaterial culture nor territorial scale was considered by IPD planning regulations at the national level, they must be addressed by specific management and execution tasks at the local level; these are the subject of the next section.

2.2. Task division and communication between agents

This section explains the current division of tasks between the local government and citizens. The main role of local governments is putting national policies and local circumstances together. All the above-mentioned local government offices in charge of IPDs (i.e., the municipal Board of Education or the office specifically created for the preservation of the IPD) are in charge of the permits and grants for preservation work on structures, both public and private (). Money for grants is jointly provided by the ACA and municipal government, who contribute different proportions depending on the town. To gain access to these monetary grants, any work that alters the present state of a structure (genjō henkō) must meet the criteria established by the ACA and the corresponding municipal government. These criteria often establish different categories of interventions with different conditions that need to be met. Three of the most common categories are the restoration of a traditional building (shūri), harmonisation of a non-traditional building to its environment (shūkei) and any other work permitted for the sake of liveability (kyoka or permit). The former two categories allow the promoter of the work to obtain a public grant, while the latter does not. In the districts designated after 1990, and regardless of the category a certain project is applying for, detailed historical research – supervised by a local government office – is requisite to establishing the specific intervention criteria for the structure to be altered.

Table 4. Task division and communication between agents

The other task shared by the majority of local governments’ main offices is the execution of public works on urban space and infrastructure. These public works can include parks and rest areas, paved streets, trees, walls, terraces, sewage and waterworks, electric lines or equipment for fire protection. In Kurayoshi, the local government stated that the community fixed the urban sewage network at their own expense once, but since then all public works have been the responsibility of the local government. In Ine, the government executes public works but the community decides on the schedule thereof.

Three districts have different policies about public works. In Kurashiki, public works are conducted by the Office of Town Planning instead, while Uchiko and Unomachi continue the custom of locals taking care of the street space and infrastructure in front of their houses. In Uchiko, however, the local government has collaborated with the community on works such as the opening of public rest areas, establishment of disaster prevention works or burying of electric lines (Miyazawa Citation1991).

Communication with local community groups is led by the government office in charge of the IPD in Kurashiki, Fukiya and Uchiko, but community groups lead communication in the more recently designated districts by organising periodic formal meetings and deciding the topics to discuss. Some local governments assist community groups with communication by working as their contact office. Most governmental offices also maintain some direct channel to communicate with local individuals, from informal visits to each household to more formal periodical surveys or manuals containing legal or technical information regarding preservation (). In addition to the manuals, local governments in rural and sparsely populated municipalities have recently started providing direct technical assistance to locals, due to community members reporting difficulties in finding competent professionals to renovate their private properties.

The tasks most frequently conducted by the community groups involve communicating with authorities, other communities and scholars and raising awareness in local citizens as well as visitors and possible newcomers (). All groups visit other districts and create regional collaborative networks, and some of them join national networks – such as Zenkoku Machinami Hozon Renmei, founded in 1974 – to share experiences and goals. Through Hozon Renmei, community groups worked with ICOMOS Japan on the Machinami Charter of 2000, which acknowledged preservation of the daily life of residents as a key goal of town preservation (ICOMOS Japan Citation2000). Community groups also maintain formal or informal communication with citizens, whether through one-on-one consultations or publications and events such as maintenance works and fire-prevention drills. Visitor information and tourism promotion are also managed by community groups, with the exception of the Kurashiki Tourism Office and the Ine Tourism Cooperative, a Destination Marketing Organisation (DMO) managed by workers and volunteers from outside the community.

The second most numerous tasks are related to the management of work on structures and their subsequent use, which also includes work on public spaces, facilities and infrastructure in the districts designated after 2004. In addition, most community groups conduct, or have conducted in the past, tasks related to the management and repurposing of empty structures, including actions to attract new residential or business tenants. In Kurayoshi, the headquarters of the local community group is a repurposed private building. Akagawara Company also repurposes old storehouses as multipurpose pavilions. They then run some of the repurposed structures themselves while ceding the others to partners, such as a structure currently used as a tourism information point which has functioned in the past as both a job-hunting information point for young people and a cafe managed by vocational college students (City and Regional Development Bureau Citation2006). In Unomachi, the old sake brewery Ikedaya was repurposed in the early 2000s – by its owner on his own initiative – as a pavilion that young people could rent to organise events and concerts.

Finally, community groups also conduct research activities related to two topics: the recovery of local crafts to be used as techniques for preservation works and as an economic asset linked to traditional jobs; and the study of successful management experiences in other IPDs through the above-mentioned visits to and from other districts, which have been documented in all the studied districts, and through other events such as symposia. The degree to which a community group is involved in research activities is greater in the communities that decide on the schedule of preservation works and lead communication with the local government.

In conclusion, the local government widely assumes responsibility for tasks related to the planning of public space and infrastructure, as well as coordination with the central government on regulations, preservation criteria or monetary grants for preservation works. However, the studied cases also showcased a trend towards community-led management and communication models. Community groups work on the maintenance and subsequent use of structures, the revitalisation of community life and the raising of awareness towards the value and needs of their districts. This task division is broadly characteristic of the studied districts regardless of their year of designation. Thus, while the motivations of later groups were broader in scope, the tasks related to these motivations have also been assumed by earlier groups more recently. However, this broader range of tasks is becoming increasingly difficult for community groups in rural areas with decreasing populations to accomplish. Consequently, some community groups have required assistance from the government for certain tasks since the latter half of the 2000s.

2.3. Outcomes of preservation activities

This section aims to clarify the outcomes of management activities in each studied district with regard to its functional network, social structures, town environment and town structure. Regarding functional network, two topics were addressed in the interviews: the adaptation of public facilities and services to communities’ needs and transformations on private urban soil. Five out of eight districts have access, on foot, to every type of public facility (). In the cases of Kurashiki and Uchiko, in which the Town Planning Office plays an active role in the management of the preserved district, the closure or replacement of a facility is compensated for by town planning, such as the new hospital constructed in Uchiko (as noted in Ehime Shinbun, 23 January 2013). The districts of Kurayoshi, Unomachi and Obama maintain a central position in the urban structure and are therefore well connected to public facilities. The other three cases are characterised by a lack of facilities in the vicinity of the IPD, with some having moved to locations not reachable on foot: Fukiya and Kumagawajuku lost their centrality when they were merged into larger municipalities, and Ine was also scheduled to be merged. This, in turn, prompted all three municipal Town Planning Offices to restructure facility networks, moving them away to new areas of centrality or to hubs near new bypass roads. To provide access to these public facilities, local governments increased the number of bus lines and public car parks. However, in some districts, private landowners also transformed their properties into car parks, purportedly because public car parks were insufficient or inconveniently located.

Table 5. Transformation of urban functions on public and private property

As for functional transformations on private property, most districts have recovered unused structures by repurposing them as tourism assets such as local museums or visitor centres (often implemented in conjunction with an increase in tourism-oriented businesses in the vicinity); as local-oriented businesses run by new tenants; or as community facilities for different purposes, such as research, safety drills, and events to attract young people. However, these cases are in the minority, while vacant properties and properties that are suitable only for dwelling have increased significantly. Overall, the positive impact of tourism on land use seems insufficient to counteract the negative impact of unused structures, but this balance is better in those districts in which new local businesses were opened.

The current state of social structures in the studied districts appears to be linked to the state of the functional networks. Five out of eight districts reported that their populations were declining faster than those in surrounding areas, and lack of employment and limited access to the necessities of modern living (i.e., fully equipped houses in quarters with a functional road network, car parks and public facilities) were reported as the first and second most frequent causes of these declines. The exceptions are Kurashiki (population currently increasing), Kurayoshi (at a standstill) and Ine (decreasing, although slower than the other districts in the municipality). Community groups in all three districts reportedly succeeded in their measures to create jobs through the founding of new businesses or the recovery of old crafts and merchandise. However, according to data from municipal governments, the impact of such measures on the recovery of the population residing in the districts is limited. Kurashiki and Kurayoshi successfully attracted young business people who put empty structures to new use; however, the above-mentioned initiatives meant to attract young people to Kurayoshi had limited impact, as the young people paid only occasional visits. In Ine, the recovery of the traditional fishing industry helped to recover only male-oriented jobs, while the lack of jobs for young females was reported by the local government to be a problem in ensuring the future of the community.

In addition, structural transformations, especially those that imply the replacement of traditional businesses, have visible effects on street space. In Kurashiki, the west area of the district, which has been the most transformed by tourism activity, contains many structures that are used as shops and are therefore empty at night; the Office of Town Planning and community groups installed street lighting to avoid a sense of emptiness and unsafety in this area. In contrast, the east area attracted new inhabitants who opened shops related to local industries in the same structures into which they moved; consequently, the area is inhabited day and night. Kurayoshi has a similar problem regarding differences between day and night: according to the local government, around 30 buildings are being used as newly established shops but the new tenants live elsewhere. In addition, the feeling of emptiness has reportedly increased due to the increasing number of properties demolished to open car parks.

Regarding the current state of the town environment, IPD regulations in the districts designated before 1990 are limited to the colours and materials of the visual environment or machinami (lit. ‘street row’), while other environmental considerations such as the living environment and natural resources are managed through separate actions. Local governments create catalogues of typical-like architectural elements that look like they belonged in the past, while the elements considered visual burdens, such as electrical lines, are removed from the street space. Consequently, the visuals in these districts consistently convey the image of ‘typical’ traditional streets; in some cases, this is even accomplished by adding corrective measures to non-traditional buildings (Yōkaichi Gokoku Machinami Hozon Centre Citation2013).

As for the preservation of the community’s living environment, the earliest attempt to include it in IPD regulations in any of the studied districts was seen in Uchiko in 1986. The local government attempted to extend preservation to the internal courtyards of properties but met local opposition (Uchiko Town Citation1987). Since then, many of the initiatives regarding preservation of the living environment in Uchiko have been outside the IPD. One example is the muranami network, which aimed to extend preservation from the town centre to rural areas, including their natural resources, their productive activities and the buildings and structures related to them. In the 1990s, preservation plans in Kumagawa and Kurayoshi were agreed upon between the government and the community and comprised the preservation of spaces considered as part of the living environment, such as fields, terraces, courtyards and annexes. Traditional architectural elements are allowed to be recovered only if their existence can be verified through research and they are compatible with current requirements regarding use, accessibility and safety. Design innovations in interior spaces are allowed in order to make houses comfortable and appealing for modern dwellers. After 2004, modernisation of elements such as windows, home equipment or sewage became increasingly accepted and encouraged to guarantee the use of structures and the feasibility of their inclusion as a part of the modern living environment, as long as such changes did not alter the relation between internal spaces and the street. However, this focus on use also brought unwanted consequences such as structures and private land plots being demolished or severely altered to construct garages or other infrastructure.

Regarding the preservation of town structure, IPDs designated before 1990 determined the area of the districts to preserve based on three parameters: their archetypal condition as Japanese towns, their main activity or function and their historical prime time in the past, in which the traditional economic activities of the town were at their peak and brought about the area’s full urban development and to which interventions would aim to return (). As for each individual structure, the period of peak value could be wider, provided that some structures built later than the prime time were built in a way that respected the town structure. In contrast, the districts designated after 1990 were defined in research reports as being the result of several historically valuable layers, including the present. Progressively, more modern structures and western-style structures were considered valuable. Interventions to recover the typical shape of each structure at its prime have also been replaced by individualised projects, and historical research on the structure in question is conducted by several municipalities as a requisite to gain access to monetary grants. Regulations have evolved towards a more comprehensive model in which exteriors are more loosely regulated and, instead, non-compulsory guidelines for accessibility, structural safety (e.g., against earthquakes) and fire safety are published. As a result, the interventions in the districts designated after 1990 increasingly avoided historical forgeries such as the introduction of typical-like elements that never actually existed; at the same time, the above-mentioned design innovations in interior spaces were developed as practical examples of the integration of old and new.

Table 6. Regulations and philosophies on the preservation of historical town structure

This shift in structural interventions was reported to be a consequence of increasing community involvement in the management of structural preservation. However, the historical research regarding structures, traditional uses of the urban space and the link between the public and private, which has been increasingly included in the research reports of both early and recently designated districts, is conducted by local governments alone. The results of such research do not always reflect the actual works, because the communities often focus on private structures while external spaces receive the least attention – especially external areas which are private property yet are part of the collective space as a buffer between private and street spaces. This is the case for areas such as the open spaces facing the bay in Ine, which are typically located between private and public land and which research reports state were once spaces for trading and communication with outsiders as well as for different civil and religious celebrations; these spaces remain underused and only regain their importance during festivals. Likewise, the Uchiko moon-viewing festival or Unomachi firefly-lamp festival make use of buffer spaces next to shopfronts, but only during a limited period every year. In Obama, the local government conducted excavations to research the historical significance of the greens surrounding temples and opened them to the community, but thus far no intervention has been planned to confer significance to these spaces.

3. Discussion

The agents participating in preservation management, as well as their roles, specific actions and works, have evolved over time. summarizes the main agents and works as presented in each area’s bulletins and reports and puts them in a national context. The early stage of IPDs (i.e., districts designated in the period 1975–1990) is characterised by strong leader figures inside local government or academia, along with a number of plans (general or district plans) based on the City Planning Law that coexist with preservation plans based on the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties. In the context of the development of both laws, municipalities implemented a management model that relied strongly on planning tools controlled by local governments; however, survey reports and plans often mention the necessity of evolving towards a model that incorporates greater involvement of local communities. Okada from Uchiko stated two major reasons why it is convenient to transfer the leading role to the community as early as possible (Nishimura Citation2007; Machiya Shinshiroku Citation2013). On the one hand, management of public workers in Japan prioritises mobility over specialised professional profiles, and it is a common practice for workers to be transferred every few years. Such practices were specifically criticised even in districts that were not designated as IPDs due to local opposition: Unomachi Hozonkai stated that personnel transfers hinder communication and the establishment of common goals between the government and citizens (Unomachi Machinami Hozonkai, ed Citation2015). On the other hand, community members have what might be the only home they own in their lifetime inside the district. In fact, most of the studied survey reports included a questionnaire distributed to locals, who showed concern about the possibility of being unable to assume the cost of strict regulations imposed on their houses. Depopulation, a lack of job opportunities and the increase in unused structures were also mentioned by citizens as threats to their living environment, while governmental plans were more focused on stating the scholarly value of the area to achieve an IPD designation. These differences in goals resulted in opposition by communities to preservation policies during the 1980s, hindering the transfer of the leading role to the community.

Figure 4. Timeline of principal agents and actions as published in their reports and bulletins (excluding periodical and/or continuous events such as regular visits to other districts or periodical reports)

Management in these early-designated districts had three common traits. First, a top-down workflow relying on town planning tools, which allowed for coordination between district facility plans and preservation plans, often resulting in public facilities being close to preserved districts. Second, a preservation policy that only included the street space and the properties that had high value by themselves, according to the ACA’s expectation that IPDs occupy the minimum necessary area for preservation. Ye et al. (Citation1998) explained how buffer areas defined by town planning around preserved districts became common in Japan in the second half of the 1980s as an alternative way to extend preservation. Such complementary plans are present in the bikan chiku in Kurashiki, the scenic preservation plans in several districts and the muranami network in Uchiko. Third, an approach based on the idea of a ‘living museum’ (Nariwa Town Board of Education Citation1977, Citation1991; Comprehensive Regional Planning Office, ed Citation1983; Kurashiki Toshibi Kyōkai, ed Citation1990), developed through a number of works and plans focused on tourism (). Local governments and scholars presented tourism as a way to raise self-awareness in communities through external valuation; the ‘living museum’ approach was a means, not a final goal in and of itself. This idea was present in the cases of Kurashiki, Fukiya and Uchiko, as well as in other early failed attempts that met local opposition, such as in Unomachi or in the plans to enlarge the IPD area of Uchiko in 1987. Hohn (Citation1998) showcased how communities in some IPDs around Japan showed divided opinions about the negative environmental impact of tourism. In the 1980s, a few municipalities in Japan implemented bottom-up machizukuri initiatives to find a balance between local development and the transformations caused by tourism (Nishiyama Citation1990); however, the spread of such initiatives might have been slow at that time, as the districts studied here present very few similar initiatives.

Thus, preservation was heavily focused on the aesthetic of the street space, with most works consisting of the removal of visual burdens such as modern materials on facades or electricity poles on the street. However, this focus on street space limited the number of sightseeing places available for tourists, since only the street space and a few structures were open to the public; this, in turn, resulted in reports describing a ‘walk-and-watch’ fast-paced tourism. Such tourism results in little return to the community, with only a few buildings hosting businesses and the majority serving as dwellings. The sole – and only partial – exception is Kurashiki, which established its own network of museums and tourism facilities in the western half of its preserved district starting from the 1950s. However, Kurashiki is an example of what Jacobs (Citation1992, 241) defined as ‘the self-destruction of diversity' caused by the one predominant economic activity, tourism in this case, which is the foundational motivation of the Mamori Sodateru Kai community group.

The 1990s brought several changes that facilitated the introduction of cooperative management models. First, as Sorensen (Citation2007) explained, local governments grew aware of the limitations of planning under the strict control of the central government and progressively sought legitimation of their policies through citizen participation in machizukuri initiatives. Such initiatives sought coordination at a national level after the Great Hanshin Earthquake (Satoh Citation2019). This resulted in new legislation and tools for community participation (). Second, the composition of communities changed. Yamamoto (Citation2017) clarified that the transformation of communities away from large urban areas happened from the late 1980s onward because the natural growth rate became negative, while the net migration rate grew every year. This migrant generation, called the ‘UJI-turn generation’, comprised people who moved back to their hometowns or other rural areas after retiring or losing their jobs in large cities after the Japanese economic bubble burst in 1990. Their interest in preservation was purportedly to maintain their town’s lifestyle as it had been in their childhood (Saio and Terao Citation2014). Finally, the governmental goals of preservation progressively included the claims of the local community; this is apparent in the districts designated in 1990–2004 that were included in this study. In Kumagawajuku, the government faced local opposition during the 1980s and the Machizukuri master plan predates IPD ordinance (); in addition, one of the first works after IPD designation was the intervention on Old Henmi Kanbei House as a practical example of the adaptability of town houses to modern needs and design. In Kurayoshi, interventions in structures began in the 1980s with the restoration of warehouses facing the Tama River instead of the facades of the main street, in accordance with the concerns expressed by citizens; these storehouses and the river area would remain a central part of the area’s preservation after IPD designation.

Thus, management evolved towards the preservation of the ‘living space’ of the community, while the types of actions executed for preservation evolved to a case-by-case study and adaptive preservation of each structure. Preservation policies also widened their scope to include not only street space but also pre-existing urban networks such as paths, water supply lines, sewage or electric networks and, on private land, entire structures including secondary buildings and land plots. In some cases, the private courtyards of repurposed buildings were made publicly accessible so that they could be regarded as public space. In addition, new tools allowed the extension of preservation to interiors and family spaces. The 1996 amendment to the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties introduced a new category of preserved structures, called tōroku bunkazai or Registered Cultural Properties, which allowed a broader scope of residential and industrial buildings to be preserved by claiming their historical value. Furthermore, the internal structure of buildings was argued in cases such as Kurayoshi and Kumagawajuku to be a necessary supporting element of the external aspect, and governments used diverse tools such as fire prevention plans to preserve such structures.

These circumstances defined a model of preservation focused on the use of structures and spaces. This model solved some of the shortcomings seen in previously preserved districts, such as community opposition and the lack of available spaces for the community or newcomers to conduct activities. These activities included tourism, although not prominently, and often stressed the need for sustainability and compatibility with local community development. However, other negative outcomes appeared as the focus on use left those structures that had not been repurposed vulnerable. In addition, the community only shared with the government the goal of revitalising their district, leaving the government in charge of any historical study. This has been explained as the gap between academic and practical knowledge that hinders the ability of communities to establish a comprehensive and long-term view of preservation (Alvarez Fernandez Citation2018).

At a national level, the criteria established by the ACA for designation evolved during the 1990s, if only partially. Kurayoshi was rejected for designation by the ACA in 1981 and designated only partially in 1998, before achieving designation of the entire district in 2010. This process required the redefinition of what a ‘valuable town’ was from the 1990s onward, but these criteria affected designations rather than planning in designated districts because legislation regarding the preservation tools available for municipalities had not changed significantly. Consequently, many of the new concepts surrounding preservation were introduced during the 1990s by complementary plans (e.g., scenic preservation plans, fire prevention plans, machizukuri plans) or specific management actions that complemented IPD preservation plans. For instance, all the measures designed to deal with depopulation, such as attracting new inhabitants or repurposing structures, were locally managed. Among such management actions, the successful ones became a subject of study in research conducted by community groups during the 2000s.

In the 2000s, several legislative changes influenced town preservation policies. First, the end of agency-delegated functions in 2000 allowed municipal governments to reorganise their tasks in more flexible ways; in the case of districts such as Uchiko and Unomachi, they created new offices with comprehensive goals within the IPDs. In addition, the Landscape Law was passed in 2004 along with another amendment to the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties, which included cultural landscapes as a new category of preserved properties. Later, the 2008 Law on the Maintenance and Improvement of Historical Landscape in a Community established ‘priority zones’ of different categories, one of which was ‘zones within or surrounding the Important Preservation Districts for Groups of Traditional Buildings’ (Art.2.1.2). These enabled towns to develop new tools to preserve their environments at different scales, from street space to an entire municipality. Thus, during the 2000s, the humanised landscape became officially considered as part of the ‘living environment’ and a material support of immaterial culture.

Community groups in late-designated IPDs launched activities related to community development and preservation of immaterial culture (fishing activity in Ine, teahouses in Obama, educational facilities in Unomachi), in some cases decades before their IPD designation. Management of preservation efforts became increasingly community-led, regulations concerning facades were more flexible (especially with the kyoka category) and works were proposed as future-focused adaptive interventions that responded to the future needs of local life. This helped recover and update not only structures but also the activities traditionally linked to them, such as traditional fishing in Ine coexisting with fish farming, or teahouses in Obama converted into cafes. Such an approach would also be adopted in earlier-designated districts: Uchiko’s muranami network increasingly included community-led works and facilities, such as a new market and rural lodgings, to preserve traditional agricultural production and the structures connected with it in rural areas. In Kurashiki, Machiya Trust encouraged the recovery of activities related to the textile industry in their search for tenants for empty properties.

However, late-designated districts have also encountered new problems. The last generation to have lived in the districts before their transformation in the 1960s is disappearing without replacement. Yamamoto (Citation2017) explains that the process of absorption of small villages into larger municipalities in 2005 caused a decrease in civil servant jobs and made it difficult for young families to remain in these areas. These absorptions also resulted in public facilities being concentrated in new central areas, away from the IPDs. In addition, while the latest IPD surveys increasingly include topics such as landscape, the natural environment and traditional economic activities, and while historical studies of individual preserved buildings have also improved, these studies remain in the academic and governmental domains. The community is increasingly in charge of management tasks but has no access to such studies; consequently, they focus on what they perceive as immediate problems, i.e., disaster prevention or the preservation of traditional activities and some private buildings, which are included in initiatives such as machizukuri plans. In addition, communities often struggle when dealing with open spaces, especially those which are between public and private areas, as none of the agents has defined measures for the preservation or resignification of such spaces or the activities thereof in the districts studied in this paper.

From an international viewpoint, IPD management in Japan has seen the expansion of the concept of heritage, with a wider set of values which transform into a wider range of policies and active agents. This was reflected in the Japanese legislation reforms at the turn of the century, which acknowledged the importance of such values and agents. However, the Japanese specificities of weak planning power and a long tradition of community structures help to explain how the IPD system greatly expanded only after the 1990s, when values shared by the community were given priority and the community became actively involved through organised groups. This, in turn, was reflected in actions and works focused on what Lynch (Citation1972) called the management of change, i.e., by interventions geared towards adaptive preservation that surpassed the cosmetics of the visual environment. These examples can help to find solutions to the governance problems of new preservation paradigms discussed in the introduction of this paper. However, the disconnect between academic and practical knowledge needs to be addressed, in order to confer significance to collective urban spaces through specific works and actions.

4. Conclusions

This paper explained the evolution of management agents, goals and actions in Japanese IPD preservation, as well as its specificities in an international context. The findings presented here clarified how the government and community have been active agents in the preservation management of IPDs. However, this management has evolved from being government-led to being cooperative or even community-led, as the values for preservation have increasingly matched communities’ priorities and the communities have taken charge of more diverse tasks. For their part, scholars have increasingly assumed a subsidiary, external role, and the contents of their research have not always been reflected in preservation works, which have focused more on one-time interventions or events and less on long-term visions. Finally, the outcomes of preservation now involve more aspects of community life than they did in 1975. However, challenges remain, including the lack of a next generation to assume the community role and infrequent use of knowledge obtained through research to preserve and confer significance on common urban spaces.

Disclosure statement

The author declares having no conflicting interests with the topic of research presented in this paper.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jon Alvarez Fernandez

Jon Alvarez Fernandez MSc in Architecture (Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2006), MSc in Restoration and Comprehensive Management of Built Heritage (Universidad del País Vasco, 2013), Doctor of Architecture (Waseda University, 2018). Working on research projects on built heritage since 2003, including research on groups of monumental buildings, traditional districts and 20th century housing districts. Currently giving lectures as an External Visiting Lecturer for the Masters Degree on Architecture by the Department of Architecture of Waseda University (Tokyo), and contributing to the Research Group on the History of Diffusion of Japanese Architecture in the West, within the Laboratory of Architectural History of the same Department.

References

- ACA (Agency for Cultural Affairs). 2002. Invitation to the System of Preservation Districts for Groups of Historic Buildings. Tokyo: Government of Japan

- Alvarez Fernandez, J. 2018. “Management of Knowledge as an Urban Preservation Tool in Japan Rural Areas.” Proceedings ISAIA 2018 The 12th International Symposium on Architectural Interchanges in Asia, Pyeongchang, AIK, 1114–1117.

- Alvarez, J. 2017. “Significance of Tourism and Local Communities: A Study on the Shift of Valuation Criteria of Japanese Protected Townscapes.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 82 (736): 1619–1629. doi:10.3130/aija.82.1619.

- Azpeitia Santander, A., A. Azkarate Garai-Olaun, and A. De la Fuente Arana. 2018. “Historic Urban Landscapes: A Review on Trends and Methodologies in the Urban Context of the 21st Century.” Sustainability 10 (8): 2603. doi:10.3390/su10082603.

- Bandarin, F., and R. Van Oers. 2012. The Historic Urban Landscape. Managing Heritage in an Urban Century. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Barrett, B. F. D., and R. Therivel. 1991. Environmental Policy and Impact Assessment in Japan. London: Routledge.

- Choay, F. 2007. Alegoría del Patrimonio. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

- City and Regional Development Bureau. 2006. “Jirei Bangō 111: Hito to Shizen to Bunka Ga Tsukuru Haruka Na Machi Kurayoshi (Tottori-ken Kurayoshi-shi).” Urban Regeneration Works Database. www.mlit.go.jp/crd/city/mint/htm_doc/pdf/111kurayoshi.pdf (accessed 4 August 2019)

- Comprehensive Regional Planning Office, ed. 1983. Uchiko No ‘Hikari’ Wo ‘Mi’ Naosō: Uchiko Chō Kankō Shinkō Keikakusho. Uchiko: Uchiko Town.

- Enkakushi Henshū Iinkai, ed. 2001. Uwa Kyōdo Bunka Hozonkai Enkakushi. Uwa: Uwa Kyōdo Bunka Hozonkai.

- Henrichsen, C. 1998. “Historical Outline of Conservation Legislation in Japan.” In Hozon: Architectural and Urban Conservation in Japan, edited by S. R. C. T. Enders and N. Gutschow, 12–16. Stuttgart: Axel Menges.

- Hertz, E. 2015. “Bottoms, Genuine and Spurious.” In Between Imagined Communities and Communities of Practice: Participation, Territory and the Making of Heritage, edited by N. Adell, R. F. Bendix, C. Bortolotto and M. Tauschek, 25–57. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen.

- Hohn, U. 1997. “Townscape Preservation in Japanese Urban Planning.” The Town Planning Review 68 (2): 213–255. doi:10.3828/tpr.68.2.c317v54555039853.

- Hohn, U. 1998. “Important Preservation Districts for Groups of Historic Buildings.” In Hozon: Architectural and Urban Conservation in Japan, edited by S. R. C. T. Enders and N. Gutschow, 150–155. Stuttgart: Edition Axel Menges.

- ICOMOS Japan. 2000. Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Settlements of Japan. The Machinami Charter. Tokyo: ICOMOS Japan. December.

- Ishida, Y. 2000. “Local Initiatives and Decentralisation of Planning Power in Japan.” 9th International Conference of the European Association for Japanese Studies, Lahti: EAJS.

- Jacobs, J. 1992. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books.

- Kaminaka Town. 1982. Wakasa Kaidō No Shukuba Kumagawa: Fukui Ken Dentōteki Kenzōbutsugun Chōsa Hōkokusho. Kaminaka: Kaminaka Town.

- Kariya, Y. 2011. “La Conservazione Urbana e dei Centri Minori.” In Il Restauro in Giappone: Architetture, Città, Paesaggi, edited by G. Gianighian and M. Dario Paolucci, 83–89. Florence: Alinea Editrice.

- Kobayashi, F., and M. Kawakami. 2003. “Policies Implemented in the Application Process of Preservation Districts for Groups of Historic Buildings (In Japanese).” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 68 (567): 87–94. doi:10.3130/aija.68.87_1.

- Koide, K. 1999. “Denken Chiku No Jōrei: Nara-ken Kashiwara-shi Imai-cho.” In Chihō Bunken Jidai No Machizukuri Jōrei, edited by S. Kobayashi, 73–90. Tokyo: Gakugei Shuppansha.

- Kurashiki Toshibi Kyōkai, ed. 1990. Jitsuroku Kurashiki Machinami Monogatari. Okayama: Techōsha.

- Lynch, K. 1972. What Time Is This Place? Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Machiya Shinshiroku. 2013.DVD. Directed by Y. Itō. Produced by Group Gendai

- Miyazawa, S. 1991. Uchiko Chō No Minka to Machinami. Uchiko: Uchiko Town.

- Mori, T. 2014. “Preservation Concepts of Villages in the Policy Establishing Process of Preservation Districts for Groups of Traditional Buildings (In Japanese).” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 79 (702): 1839–1844. doi:10.3130/aija.79.1839.

- Nariwa Town Board of Education. 1977. Bicchu Fukiya: Machinami Chōsa Hōkokusho. Nariwa: Nariwa Town.

- Nariwa Town Board of Education. 1991. Dentōteki Kenzōbutsugun Hozon Chiku Minaoshi Chōsa Hōkokusho. Nariwa: Nariwa Town.

- Nishimura, Y. 2007. Shōgen: Machinami Hozon. Kyoto: Gakugei Shuppansha.

- Nishiyama, U. 1990. Rekishiteki Keikan to Machizukuri. Tokyo: Toshi Bunkasha.

- Saio, N., and Y. Terao. 2014. “A Study of Sustainability of Habitation in the Historical Preservation Areas (In Japanese).” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 79 (695): 131–139. doi:10.3130/aija.79.131.

- Sanada, H. 2011. “Denken-gun À Kurayoshi.” Colloque Franco-Japonais sur le Paysage à Kurayoshi Oct.1–3, 2011, Tokyo/Kurayoshi.

- Sanbe, N. 1999. “Jōrei Seitei Wo Meguru Hōteki Mondaiten.” In Chihō Bunken Jidai No Machizukuri Jōrei, edited by S. Kobayashi, 13–16. Tokyo: Gakugei Shuppansha.

- Satoh, S. 2019. “Evolution and Methodology of Japanese Machizukuri for the Improvement of Living Environment.” Japan Architectural Review 2 (2): 127–142. doi:10.1002/2475-8876.12084.

- Siegenthaler, P. 2003. “Creation Myths for the Preservation of Tsumago Post-town.” Planning Forum 9: 29–45.

- Sorensen, A. 2002. The Making of Urban Japan: Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge.

- Sorensen, A. 2007. “Changing Governance of Shared Spaces: Machizukuri in Historical Institutional Perspective.” In Living Cities in Japan: Citizens’ Movements, Community Building, and Local Environments, edited by A. Sorensen and C. Funck, 56–90. London: Routledge.

- Steiner, K. 1965. Local Government in Japan. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Suzuki, S. 2009. “Chiisana Jichitai No Chōsen. Ehime Ken Uchiko Chō No Machizukuri No Tokuchō.” Zaisei to Kōkyō Seisaku 31 (1): 2–9.

- Takao, Y. 2006. “Co-Governance by Local Government and Civil Society Groups in Japan: Balancing Equity and Efficiency for Trust in Public Institutions.” The Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 28 (2): 171–199. doi:10.1080/23276665.2006.10779321

- Uchiko Town. 1987. Uchiko Muikaichi-Yōkaichi Gokoku Chiku. Dentōteki Kenzōbutsugun Hozon Chiku Hozon Taisaku Chōsa Hōkokusho. Uchiko: Uchiko Town.

- Uchiumi, M. 1999. “Shidō Yōkō to Machizukuri Jōrei No Jittai.” In Chihō Bunken Jidai No Machizukuri Jōrei, edited by S. Kobayashi, 22–34. Tokyo: Gakugei Shuppansha.

- Unomachi Machinami Hozonkai, ed. 2015. Symposium Unomachi No Machinami Wo Kangaeru: Kako Kara Mirai He. Seiyo: Unomachi Machinami Hozonkai.

- Wakasa Kumagawajuku Machizukuri Tokubetsu Iinkai. 2007. Saba Kaidō Kumagawajuku Katsuseika Moderu Chōsa. Wakasa: Research report.

- Yamamoto, T. 2017. Jinkō Kanryū (U-turn) to Kaso Nōsanson No Shakaigaku. Tokyo: Gakubunsha.

- Ye, H., S. Asano, Y. Yoshida, and K. Tonuma. 1998. “A Study on the Present State and Change of Designation of Districts for Preservation Districts for Groups of Historic Buildings (In Japanese).” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 63 (506): 111–118. doi:10.3130/aija.63.111_2.

- Yōkaichi Gokoku Machinami Hozon Centre. 2013. Shūri Shūkei Kiroku. Uchiko Chō Yōkaichi Gokoku Dentōteki Kenzōbutsugun Hozon Chiku. Uchiko: Uchiko Town.