ABSTRACT

This paper aims to clarify Charlotte Perriand’s (1903–1999) formation of the notion of the “vacuum” through a reading of The Book of Tea written by Kakuzo Okakura in 1906, using the French version of The Book of Tea, which Perriand possessed, and her articles that quoted this book. It is certain that her multifaceted and ethnological interests in other cultures allowed her to accept the unfamiliar notion of the “vacuum”. However, Perriand’s interpretation of the “vacuum” was characteristic. Her main interest concerning Okakura’s notion of the “vacuum” was the question of the human “gesture”, and she developed this through her direct experience of Japan. The metaphysics of the “vacuum” as before “space”, as defined by Okakura, was examined by Perriand using the question of the possibility of the unknown “gesture” in a physical “space”.

1. Introduction

This paper aims to clarify Charlotte Perriand’s (1903–1999) formation of the notion of the “vacuum” from the viewpoint of architectural theory. As a French architect and interior designer, Perriand was not only influenced by Le Corbusier with whom she collaborated temporarily (Sendai Citation2019), but also through her direct experience of living in Japan. Concerning Japanese philosophy, The Book of Tea written by Kakuzo Okakura in 1906, had a very deep impact on Perriand (Barsac 2008, 22–23). The Book of Tea was gifted to Perriand in 1932 by Junzo Sakakura who had also been engaged at Atelier Le Corbusier and was cited in her most significant article, “The Art to Live in”, in 1950 ().

Accordingly, this study analyses Perriand’s formation of the “vacuum”, using her conserved copy of The Book of Tea,Footnote1 which she filled with several notes and her articles that used quotations from this book.Footnote2

It is certain that the notion of “the vacuum” in English, which Okakura discussed, and « le vide » in French, which Perriand interpreted, were not the same. This is neither simple acceptance nor a misunderstanding of the philosophy. In this hypothesis, the formation of her notion of the “vacuum” can be dealt with using cross-cultural architectural modernism.

However, almost all of the studies on Perriand are an analysis of her interior design and furniture arising from her collaboration with Le Corbusier (McLeod Citation1987; Rüegg Citation2012; Pitiot 2015), or historiographies on relations with Japan (Barsac 2008; Barsac Citation2015). Compared with analyses on the influence that modern architects such as Bruno Taut or Frank Lloyd Wright had on Japan (Meech Citation2001; Speidel Citation2003), discussions on Perriand lose this wide span view of architectural theory because her work was limited to the context of being a ‘furniture designer or “Le Corbusier’s disciple”. Hence, this paper attempts to focus on the architectural theory that Perriand developed, paying attention to the notion of the “vacuum”.

2. Before The Book of Tea

Perriand’s knowledge of Japanese architecture did not begin with The Book of Tea given to her by Junzo Sakakura in 1932. When determining when her acquisition of information on Japanese architecture began, various deductions are possible. In 1927, she began her collaborations with Le Corbusier, a young Japanese architect, Kunio Mayekawa, joined the Atelier in 1928, and then in 1931, Junzo Sakakura also joined the Atelier. It is easy to imagine that they provided her with information about Japanese architecture and, additionally, Le Corbusier studied Japanese architecture (Le Corbusier and Jeanneret Citation1929, 21). However, according to Masami Makino who also belonged to Atelier Le Corbusier at that time, Le Corbusier did not know about the Japanese tatami, a module system with a standard mat of approximately 900 mm × 1800 mm.

‘He [Le-Corbusier] establishes all standards for the size of windows, height of the ceiling, the size of the entrance, etc., and he adopts them for any buildings. Full-size drawings, detailed drawings of doors, and window are common in any sort of building. This spirit of mass production must come from his own theories, but as it happens, it coincides with the reality of Japan for the last 300 years. When I explained the tatami mat or the Japanese inner measurement system, it is natural that he admired them because, for more than 300 years, Japanese people have already done what the European modernist Le Corbusier proposes as his newest theory. He responded: ‘Japan is an amazing nation” (Makino Citation1929, 68).

Makino’s testimony suggests that up until then Japanese architecture was not talked about very much in the Atelier. However, in 1929, Perriand studied the prototype housing project, Maisons Loucheur after being inspired by a book on Japanese architecture gifted by Mayekawa to Le Corbusier (Barsac Citation2015, 18–19).Footnote3 It appears that the placement of sanitary facilities, lavatories and kitchens, and the unitised furniture

We may discover the sliding doors of the Maisons Loucheur are similar to the shoji systems of traditional Japanese houses.Footnote4

However, Perriand’s interests were not only in Japanese architecture. According to one staff from Atelier Le Corbusier, she was interested in vernacular buildings in various regions and re-evaluated them in the modern context (Sert Citation1956). In her 1935 article, “Family Housing”, she analysed the physical conditions of the ‘human plan’Footnote5 in various anonymous spaces of the traditional family life in the world and intended to learn from them (Perriand Citation1935, 25). It is certain that in this article, a section drawing of a Japanese farmhouse with a caption was based on the knowledge that she had received from Sakakura about unknown Japan. However, Japan was only one of the examples she used for the consideration of the fundamental “human plan”, and at the time she did not have experience of the Japanese architectural space on site.Footnote6

3. Reading of The Book of Tea (1932–1939)

Sakakura, who introduced Perriand to Japanese architecture, was very influential on Perriand. In 1932, Sakakura gave her The Book of Tea by Kakuzo Okakura,Footnote7 which first edition was written in English in 1906, published as the Iwanami Publishers library in 1929 and became known to many Japanese. It is likely that, apart from collections of drawings and photographs, she read The Book of Tea more than other books about Japan before her first trip to Japan in 1940.Footnote8 In 1940, she wrote a letter to Sakakura to request his private consent for temporary work in Japan as an adviser as follows:

“I had just reread my Book of Tea. … finally, I realize that after so many years with you, I have learned nothing of ‘material’ [real Japanese life]”.Footnote9

As we shall see, just before her visit to Japan in August 1940, Perriand attempted to understand various Japanese manners and customs as a result of reading The Book of Tea again. She felt that she had no knowledge of the reality of Japan and this means that intuitively, she understood the importance of The Book of Tea as a document representing something essential of Japan.

Most of her annotations in the book () were vertical lines to highlight an important paragraph or sentence, and multiplex lines for more important points. As she read the book many times, time gaps exist in her annotations. However, the method and handwriting of her annotations were in order, starting from when she first received it from Sakakura. By organizing them, we can extract some key words that overlap with the citations in the articles she will write later. That is, “harmony”, “gesture”, and “vacuum”, and most of these handwritings occupied from chapter one “The Cup of Humanity”, chapter two “The School of Tea”, Chapter three “Taoism and Zennism” and Chapter four “The Tea-Room” in The Book of Tea. After chapter four, the fifth chapter, “Art Appreciation”, the sixth chapter, “Flowers”, and the seventh chapter, “Tea-Masters”, were all detailed explanations or supplements of the discussions in the first four chapters.Footnote10 In fact, Perriand’s vertical lines were also a repetition of the themes in the fourth chapter.

Table 1. Marks and notes of the sentences in Okakura-Kakuzo, tr. Gabriel Mourey, Le livre du thé, André Delpeuch, Éditeur, Paris, 1927 By Perriand Made by the author.

4. Appearance of “ambiance” by “harmony”

4.1. Interest in “harmony”

The Book of Tea was Okakura’s final book before he died, and it was the consideration of a universal “beauty” rather than a search for the specificity of the Oriental compared with the West.Footnote11 The first chapter as an introduction to this book, “The Cup of Humanity”, was the most important part of the book (Wakamatsu Citation2013, 33–34, 75). Perriand noted the opening of this chapter using a red line and these sentences formed the basis of her interest

“The Philosophy of Tea is not mere aestheticism in the ordinary acceptance of the term, for it expresses conjointly with ethics and religion our whole point of view about man and nature. It is hygiene, for it enforces cleanliness; it is economics, for it shows comfort in simplicity rather than in the complex and costly; it is moral geometry, inasmuch as it defines our sense of proportion to the universe. It represents the true spirit of Eastern democracy by making all its votaries aristocrats in taste.”Footnote12 (Okakura Citation1927, 24)

Okakura explained that tea exalted ordinary life, and denied the conventional thoughts on the tea ceremony. As a factor that introduced beauty, he cited the “moral geometry” or the “sense of proportion”, which was easy to understand as a Western philosophical concept.Footnote13 However, “Teaism” represented the unique relationship between “man and nature” in the Orient at the same time. He explained this using the word “harmony” in the last chapter of his book, but the question of the world generation was difficult logic (Okakura Citation1927, 155–156).Footnote14 In later texts by Perriand, “harmony”, “harmony with a thing and a man”, or “harmony with man and nature” appeared quite frequently (Perriand Citation1950, 85).

4.2. 4.2. “Ambience”

Perriand reffered to “harmony” in the last section “ambience” in the above mentioned “The Art to Live in”.

“Even if this habitat is the city or in the countryside, its architecture having resolved all material needs, must go beyond and unconsciously give a feeling of calm and a fullness, make rhythm, the determination of the light of day and night, color, harmonic relations of its volumes, its fullness, of its vacuum, of the game of its materials. The harmony is a whole, the elements have their own value, but side by side, they react, the one and the other, in agreement or in opposition: walls, floor, furniture, objects, colors, volume, and materials.” (Perriand Citation1950, 85)Footnote15

Perriand’s interest, like Okakura, was not in the constant characteristics of a certain space. She described the spatial variability or the possibility of the spatial generation using the interactive “agreement and opposition”. Whether the physical “vacuum” can come out, finally, was not a question for her.Footnote16 In using clothes as an example, the comfort was not due to the clothes themselves, but from wearing clothes (Perriand Citation1950, 85). Moreover, people do not wear the same clothes all the time. Therefore, the “fullness (clothes)” and the “vacuum (body)” were not alternative problems. The “harmony of the fullness and the vacuum”, in other words, the phantasmagoric “ambience” was her goal concerning “utility walls” (Perriand Citation1950, 33).

5. Potential of “gesture”

5.1. Interest in “gesture”

Perriand’s vertical lines that marked the following chapter show traces of how a Westerner was learning about the historical facts and knowledge behind the tea ceremony. She drew a single vertical line and added a bookmark in the last part of the second chapter, “The School of Tea”:

“Tea with us became more than an idealisation of the form of drinking; it is a religion of the art of life.”Footnote17 (Okakura Citation1927, 57)

“The art of life” by Okakura evokes “the art to live in”, which later became Perriand’s keywords.Footnote18 “The art of life” was not simply a technique for humanity to control the environment unilaterally, but rather it is for humanity to reform by corresponding with its surroundings and establishing an interactive relationship with them (Okakura Citation1927, 70).Footnote19 Okakura pointed out that such a physical behaviour “movement” embodied the naturalness of the human body corresponding with the naturalness of the environment. Perriand paid attention to this assertion and drew a double vertical line:

“Not a color to disturb the tone of the room, not a sound to mar the rhythm of things, not a gesture to obtrude on the harmony, not a word to break the unity of the surroundings, all movements to be performed simply and naturally … ”Footnote20 (Okakura Citation1927, 58)

Okakura’s “movement” or “gesture” was the word to explain the relationship of the pre-established “harmony” with humanity and nature, from the side of humanity.

5.2. Quotation of “gesture”

Another important article where Perriand quoted The Book of Tea was “An Alive Tradition” published in L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui in 1956 (). It was a short essay, where she wrote about Japanese houses from the same period, but it was an important article for the fact that the publication medium was a well-known architectural magazine with an extensive readership.

Figure 2. Meal in a Japanese traditional space presented in “An Alive Tradition” (Perriand Citation1956, 14).

All the sections of The Book of Tea where Perriand had drawn a vertical line were quoted without omission, and the text below is from the same article:

“There is always a vacuum that can be filled according to the moment, the mood, and his fantasy, always changing, subtly felt during the course of the seasons of life. One could also talk about a great sweetness of the things of this world, which are visible and invisible. All the gestures express this philosophy. The architecture is designed to immerse man in this euphoria” (Perriand Citation1956, 15)Footnote21

Perriand’s interest in the “vacuum” moved away from the spatial aspect of “The Art to Live in” from 1950 more and more and approached the question of the “gesture” that she read about in The Book of Tea. Moreover, the “gesture” could be neither predicted nor created, as far as it related to the changes in nature. Perriand’s “vacuum” contained the unknown variability of the “gesture” more than the pre-established harmony of the “gesture” in Okakura’s aesthetics.Footnote22 Just after she left Japan, Perriand explained the use of the tatami mat to help improve the flexibility of space, making reference to Le Corbusier’s “standard” (Perriand Citation1942, s.p.). However, in this article in 1956, she used the tatami mat as the cardinal point of this variability of the “gesture” (Perriand Citation1956, 15). She considered that the tatami mat was not only a module for creating material variableness according to circumstances or natural season but also the device of the “vacuum” to accept the ever-changing “gesture”.

6. “Vacuum” and “wall”

6.1. Interest in “vacuum”

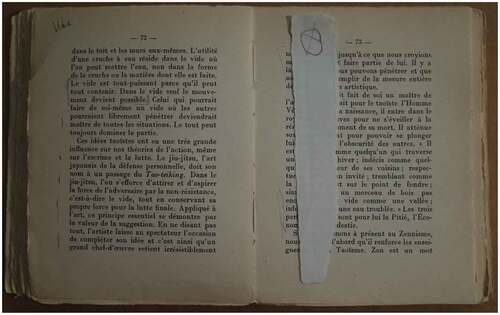

The “movement” or the “gesture” by Okakura was the word to explain the relation of the preestablished “harmony” with man and nature from the side of man. Conversely, the “vacuum” was the indication of its relation from the side of nature, which was the central theme of Perriand’s interpretation in the third chapter entitled “Taoism and Zennism”. In the following sentences from the third chapter, she drew four vertical lines and added a bookmark with the word “Zero” on it, which had a relatively philosophical tone ():

Figure 3. Annotation of The Book of Tea by Perriand concerning the Theory on “Vacuum” (Okakura Citation1927, 72–73).

“ … The conception of totality must never be lost in that of the individual. This Laotse illustrates by his favourite metaphor of the vacuum. He claimed that only in the vacuum lay the truly essential. The reality of a room, for instance, was to be found in the vacant space enclosed by the roof and walls, not in the roof and walls, not on the roofs and walls themselves.”Footnote23 (Okakura Citation1927, 71–72)

According to Okakura, the “vacuum” was the possibility of gestures, not material emptiness. Okakura’s ‘vacant space’Footnote24 was the notion before physical “space” surrounded by the walls, and the “space” and the “vacuum” were in different dimensions theoretically.Footnote25 Perriand’s degree of interpretation cannot be measured using only these vertical lines, but at least, she did not attach an annotation to the metaphysical theories, in which Okakura argued that humanity was the “vacuum” (Okakura Citation1927, 72–73).

In the fourth chapter, “The Tea-Room”, with specific examples of the “vacuum” Okakura describes the aesthetics of tea masters and the form of “the abode of vacancy (Sukiya)”, and because of the physical theme, Perriand added many annotations to this chapter. She paid the most attention to the following sentences in this chapter, and she drew four vertical lines and left a bookmark with the word “tea”:

“It is an Abode of Vacancy inasmuch as it is devoid of ornamentation except for what may be placed in it to satisfy some aesthetic need of the moment. It is an Abode of the Unsymmetrical inasmuch as it is consecrated to the worship of the Imperfect, purposely leaving something unfinished for the play of the imagination to complete. The ideals of Teaism have since the sixteenth century influenced our architecture to such degree that the ordinary Japanese interior of the present day, on account of the extreme simplicity and chasteness of its scheme of decoration, appears to foreigners almost barren.”Footnote26 (Okakura Citation1927, 82–83)

Okakura might have argued that space without decoration was the “vacuum” through a formal example. However, he did not deny the decoration. He argued that the method of decoration, or the concept itself of decoration, was different from the Western notion. It was the ‘simplicity of ornamentation and frequent change of decorative method’Footnote27 (Okakura Citation1927, 100–101), ‘everything else is selected and arranged to enhance the beauty of the principal theme’Footnote28 (Okakura Citation1927, 61). That is why he did not mention the tea service sets themselves, which were indispensable for tea ceremonies (Kumakura2007, 104–105).

Perriand did not show any interest in the formal characteristics of the space without decoration,Footnote29 and there is no indication that she paid attention to Okakura’s general explanation of the non-symmetry of the tea ceremony room. Rather, she turned her eyes to “the principal theme”, as the driver of the decoration according to circumstances: ‘the freedom that lay in the expanse beyond’Footnote30 (Okakura Citation1927, 56). However, in Perriand, it was “freedom” as physical behaviour (Perriand Citation1998, 250),Footnote31 and it was not the metaphysical spirit toward the beauty in accordance with Okakura’s logic.

6.2. “Utility walls”

It was the 1950 “The Art to Live in” where Perriand first mentioned Okakura in a published article. This was the most important of her articles that described her own theories on creation systematically, and she proposed the main themes from its beginning:

“It must here take a position. Are we going to make the fullness or the vacuum? This question, apparently ridiculous, has its importance. For someone, the vacuum is the nil or the indigence, for others the possibility to think and move.” (Perriand Citation1950, 33)Footnote32

Perriand’s consistent theme in this article was the modern “harmony of the habitat”, and her article did not discuss the tea-ceremony rooms or Sukiya buildings that she had learned about from Okakura and experienced in Japan. Nevertheless, the logical frame of the “fullness” and the “vacuum” reflected her understanding of the architectural space based on Okakura’s theory of “vacuum”.

In addition, Perriand quoted one paragraph from The Book of Tea as a reference for Okakura’s theory on “vacuum”. The following text is a part where Perriand drew four vertical lines (partially dotted lines) in The Book of Tea that she conserved from 1932 and the underline by the author is the quotation from her article in 1950:

‘ … The conception of totality must never be lost in that of the individual. This Laotse illustrates by his favourite metaphor of the Vacuum. He claimed that only in vacuum lay the truly essential. The reality of a room, for instance, was to be found in the vacant space enclosed by the roof and walls, not in the roof and walls, not on the roofs and walls themselves. … Vacuum is all potent because it is all containing. In vacuum alone motion becomes possible. One who could make of himself a vacuum into which others might freely enter would become master of all situations. The whole can always dominate the part.

These Taoists’ ideas have greatly influenced all our theories of action, even to those of fencing and wrestling. Jiu-jitsu, the Japanese art of self-defence, owes its name to a passage in the Taoteiking. In jiu-jitsu, one seeks to draw out and exhaust the enemy’s strength by non-resistance, vacuum, while conserving one’s own strength for victory in the final struggle. In art, the importance of the same principle is illustrated by the value of the suggestion. In leaving something unsaid, the beholder is given a chance to complete the idea, and thus a great masterpiece irresistibly rivets your attention until you seem to become actually a part of it. A vacuum is there for you to enter and fill up to the full measure of your aesthetic emotion.’ (Okakura Citation1927, 71–73)Footnote33

Perriand’s quotation from The Book of Tea was an essential part of the notion of the “vacuum”, namely the possibility of the human gesture. It can be said that her quotation was the precise extract of Okakura’s interpretation of Taoism.

Nevertheless, in her article, the text following the quotation from The Book of Tea is a return back to the first question of the “fullness” and the “vacuum” in the physical space in order to create modern habitation. That is, through “a widely open facade” (Perriand Citation1950, 33)Footnote34 and “inside, equipment creating the vacuum” (Perriand Citation1950, 33),Footnote35 she tried to grasp the question of the “vacuum” that of the “utility walls” (Perriand Citation1950, 33).Footnote36 This was not necessarily the same as philosophical aspect of Okakura’s theory on “vacuum”: “not in the roof and walls, not on the roofs and walls themselves” and she deleted this sentence by Okakura in “The Art to Live in”.

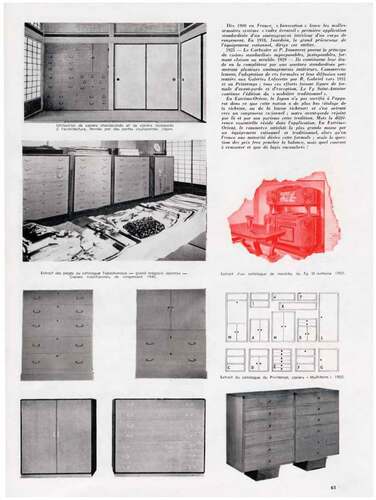

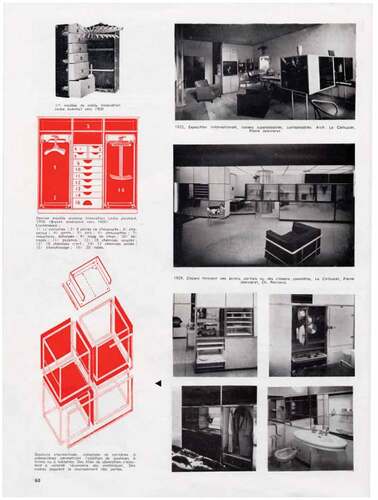

In “The Art to Live in”, after the indication of the above-mentioned theme for creation, in eight chapters, Perriand analysed examples of interior space from the Orient to the West, and from traditional houses to modern houses. In one of these chapters, “Arrangement”, the word “vacuum” is used quite frequently. Here, the physical “vacuum” can only be acquired by creating “utility walls” that store daily objects as densely as possible ().Footnote37 The illustrated “utility walls” also includes a closet closed by bran and a chest of drawers inserted between the pillars of a Japanese house, so that Perriand’s “utility walls” are not an architectonic “wall” as a skeleton structure.

Figure 4. Examples of the interior space composition of a traditional Japanese house with storage cabinets presented in “The Art to Live in” (Perriand Citation1950, 61).

7. Conclusion

Perriand’s interest in The Book of Tea induced by Junzo Sakakura was not simple exoticism. Her multifaceted and ethnological interests in other cultures allowed her to accept the unknown notion of the “vacuum”. However, she not only understood the “vacuum” as metaphysics but also interpreted it as a creative idea and a question on the phenomenon of the “vacuum” is the conclusion to the question on the creation of the “fullness” in the “vacuum” and its variable relationship. It is certain that for Perriand, the “vacuum” was a physical notion and this is not the same as Okakura’s theory, and Okakura himself did not discuss the Japanese kanewari measurement system, which is on of the primary concepts in tea rooms and Teaism.

Perriand’s coherent interest in the “vacuum” was the subject of “harmony” between humans and nature presented by Okakura. In such a harmonious environment, the “gesture” that captured her was open to variable and unknown movementsFootnote38 the metaphysics of the “vacuum” defined by Okakura has been opened to the question of the possibility of the unknown “gesture” in a physical “space”. This is the very denial of the “gesture” as pre-established harmony. Perriand did not believe in the ideal harmony she should aim for, nor did he stick to Japan alone.

The “utilities walls” is an architectural hypothesis and a vehicle of “vacuum”. After returning to France, according to her comprehension of this concept of “vacuum”, she has studied as cabinets named “cloud” (). The “cloud” that could be hung on the wall was first exhibited in the “Proposal for the Integration of Art” exhibition organized by Perriand in 1955, and since then, she has studied various variations and adapted them to residential and office buildings (Barsac Citation2017, 38–75). The “cloud” does not partition the space like the box-shaped “cabinet” of Le Corbusier (). She has prepared a variation that allows us to move furniture around the space more freely and gives the space openness as “vacuum”.

Figure 5. Arrangement of private rooms in the Mexican Pavilion with clouds and desks in 1955 (Barsac Citation2015, 409).

Figure 6. “Cabinet” proposed by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand in 1929 (Perriand Citation1950, 60).

The idea of such furniture, whose contours are not defined, was to be studied in the low wooden table series named “free form tables” (Barsac Citation2014, 422–437) as “free form which gives rhythm to a space and highlights objects” (Perriand Citation1998, 294). In this way, Perriand Inspired by Okakura, she developed a new “gesture” on both the vertical and horizontal axes of space.

In reading The Book of Tea, Perriand may have developed a superficial understanding or even misunderstanding. However, the essential notion of Okakura’s “vacuum” stimulated the interest of Perriand in Paris, and deepened as a creative theory through her experience in Japan. The process of the reading and Perriand’s interpretation of The Book of Tea shows that her receptivity of the other was a creative “question” itself.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 It is unknown exactly when Perriand read The Book of Tea, or whether Perriand read it repeatedly. Judging from her autobiography and other evidence it is assumed that she read the book just after Junzo Sakakura gave it to her. For the version of Periand’s The Book of Tea, see https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6579649f/f9.item.

2 Perriand published an autobiography just before her death (Perriand Citation1998). In the autobiography, quotations from The Book of Tea were in eight parts (Okakura Citation1927, 155, 156, 156-158, 160, 406, 408). Apart from quotations on the general knowledge of Taoism and the history of Japanese art, almost all of her quotations concern the variability of a space. However, this memoir may not reflect the process of her thinking at the time. In this paper, her autobiography was used secondarily.

3 Perriand noted the measurement in the book of the Fifty-three Stages of the Tokaido (Tokaido-chu-Gojyusantsugi) presented by Mayekawa to Le Corbusier (conserved in Foundation Le Corbusier). Her interest was the module system in Japanese space.

4 cf., FLC23134; FLC18253. Maisons Loucheur adopted sliding doors, which Le Corbusier did not use until then. An analysis presumes that this adoption was because of the influence of Kayekawa’s idea. cf., Barsac (Citation2014, 122).

5 « un plan humain ». It might be influenced by the Le Corbusier’s folklore lessons, “a plan proceeds from the inside out” « un plan procède du dedans au dehors » (Le Corbusier Citation1923, 146–150).

6 On the other hand, Perriand sketched, photographed, filed, and collated information about anonymous buildings in various places such as the Spanish island Ibiza in 1932, the French farm village Bessans in 1934, and Bandol in 1935. Several of these documents are published in Barsac (Citation2014, 294–297).

7 The first edition of The Book of Tea was published in English in 1906. The Book of Tea that Perriand possessed was the French version. cf., Okakura (Citation1927).

8 Perriand might have read an article about Japan written by the architect Bruno Taut who had already visited Japan in 1933. It can be supposed that she read Taut’s essay on his Villa Hyuga in Japan and Katsura’s article on an imperial villa in the French Magazine, L’Architecture d’Aujoud’hui. cf., Taut (Citation1937).

9 cf., AChP, letter from Charlotte Perriand to Junzô Sakakura, 1940.2.24:

« Je venais justement de relire mon Livre du thé. … enfin, je m’aperçois qu’après tant d’années auprès de toi, je n’ai rien appris de “matériel”. »

10 This is another interpretation, focusing on the chapter “Flowers”, as Okakura’s personal aesthetics (Arata Isozaki, “Space as Vacuum”, in Watari-um Art Museum (2007, 52).

11 Kinoshita interpreted the core essence of Okakura’s “beauty” as a state of perfect selflessness away from all thoughts (Kinoshita Citation2015, 282–286). It was natural that Perriand as a Westerner could not understand Okakura’s contemplation based on Orient aesthetics easily.

12 « La philosophie du thé n’est pas une simple esthétique dans l’acceptation ordinaire du terme, car elle nous aide à exprimer, conjointement avec l’éthique et avec la religion, notre conception intégrale de l’homme et de la nature. C’est une hygiène, car elle oblige à la propreté; c’est une économie, car elle démontre que le bien-être réside beaucoup plus dans la simplicité que dans la complexité et la dépense; c’est géométrie morale, car elle définit le sens de notre proportion par rapport à l’univers. Elle représente enfin le véritable esprit démocratique de l’Extrême-Orient en ce qu’elle fait de tous ses adeptes des aristocrates du goût. »

13 Okakura’s aesthetic originality was based on Hegelian idealism through Ernest Fenollosa. For example, Okakura said that the subject of the “proportion” was the universe as transcendental existence, by adapting the logic of European ontology (Ohkubo Citation1987, 247–248).

14 The single vertical line by Perriand:

« Celui-là seul qui a vécu avec la beauté mourr en beauté. Les derniers moments des maîtres de thé étaient aussi pleins de raffinement et s’exquisité que l’avait été leur vie. Cherchant toujours à se tenir en harmonie avec le grand rythme de l’univers, ils étaient toujoura prêts à entrer dans l’inconnu. »

“Only he who has lived with the beautiful can die beautifully. The last moments of the great tea masters were as full of exquisite refinement as had been their whole lives. Seeking always to be in harmony with the great rhythm of the universe, they were ever prepared to enter the unknown.”

15 « Que cet habitat soit à la ville ou à la campagne, son architecture ayant résolu tous les besoins matériels, doit aller au-delà et donner inconsciemment une sensation de calme et une plénitude, faite de rythme, du dosage de la lumière de jour et de nuit, de couleur, de rapports harmoniques de ses volumes, de ses pleins, de ses vides, du jeu de ses matériaux. L’harmonie est un tout, les éléments ont leur valeur propre, mais, cote à cote, ils réagissent les uns et les autres, en accord ou en opposition: murs, sol, meubles, objets, couleurs, volume, matériaux. »

16 In fact, in her article Perriand did not quote the “Abode of Vacancy” paragraph by Okakura, inasmuch as it is devoid of ornamentation.

17 Perriand’s single vertical line:

« Le thé devint chez nous plus qu’une idéalisation de la forme de boire: une religion de l’art de la vie. »

18 cf., Perriand (Citation1998, 248):

« Corbu avait remplacé les mots « Art décoratif » par « Équipement de l’habitation », je les remplaçai par « Art d’habiter », qui est devenu plus tard un « Art de vivre », titre de mon exposition au musée des Arts décoratifs en 1985. En tête de cette revue de 1950, j’avais placé ma définition de l’« Art d’habiter » »

“Corbu had replaced the words ‘decorative art’ with ‘housing equipment’, I have replaced them with ‘art to live in’, which later became ‘art to be alive’, the title of my exhibition at the Museum of Decorative Arts in 1985. At the beginning of this review in 1950, I used my definition of the ‘art to live in.’”

19 The triple vertical line by Perriand:

« … l’Adaptation, c’est l’Art. L’art de la vie consiste en une réadaptation constante au milieu. »

“… Adjustment is Art. The art of life lies in a constant readjustment to our surroundings.”

20 The double vertical line and the bookmark inscribed with “No color” by Perriand:

« Nulle couleur ne venait troubler la tonalité de la pièce, nul bruit ne détruisait le rythme des choses, nul geste ne gênait l’harmonie, nul mot ne rompait l’unité des alentours, tous les mouvements s’accomplissaient simplement et naturellement, – …. »

21 « Il y toujours un vide que chaque être peut remplir au gré du moment, de l’humeur, et de sa fantaisie, toujours changeant, subtilement senti au au cours des saisons de la vie. On pourrait dire également une grande douceur des choses de ce monde visible et invisible.

Tous les gestes expriment cette philosophie. L’architecture est conçu pour plonger l’homme dans cette euphorie. »

22 For example, « harmonie avec le grand rythme de l’univers » “harmony with the great rhythm of the universe” in the gestures of the tea master (Okakura Citation1927, 95, a single vertical line by Perriand).

23 « … la conception de la totalité ne doit jamais se perdre dans celle de l’individualité. Et Laotsé le démontre par sa métaphore favorite du vide. Ce n’est que dans le vide, prétendait-il, que réside ce qui est vraiment essentiel. L’on trouvera, par exemple, la réalité d’une chambre dans l’espace libre clos par le toit et les murs, non dans le toit et les murs eux-mêmes. »

24 “The vacant space” in the original text was translated as “the free space (« l’espace libre »)” in French.

25 Frank Lloyd Wright understood the “vacuum” in The Book of Tea as a sort of “space” in his “organic architecture” (Wright 1955, 80–81). On the other hand, Bruno Taut read the metaphysical “large form” beyond the formal emptiness (Taut Citation1923, 128). In fact, he found the “vacuum” as the high order in Japanese houses, especially in the alcoves where sacred art and ordinary life coexist. His dialectic understanding of art and ordinary life was opposed to Perriand’s understanding that both were impartible in life (Taut Citation2007).

26 « C’est aussi la Maison du Vide en ce qu’elle est dénuée d’ornementation et que l’on peut, par suite, d’autant plus librement, n’y placer que de quoi satisfaire un caprice esthétique passager. C’est, enfin, la Maison de l’Asymétrique en ce qu’elle est consacrée au culte de l’Imparfait, quelque chose d’inachevé que les jeux de l’imagination achèvent à leur gré. Les idéaux du Théisme ont exercé sur notre architecture, depuis le seizième siècle, une si grande influence que les intérieurs ordinaires japonais d’aujourd’hui font l’effet aux étrangers d’être presque vides, à cause de la simplicité extrême et de la pureté de leur système de décoration. »

27 Perriand’s double vertical line:

« la simplicité ornementale et aux changements de décore fréquents »

28 Perriand’s single vertical line (partial underline):

« L’on y apporte, à l’occasion, un objet d’art particulier et l’on y choisit et dispose tout en vue de faire valoir la beauté du thème principal. »

29 In contrast, Bruno Taut discovered the formal non-decorativeness in Japanese traditional residences (Taut Citation1924, 19).

30 Perriand’s single vertical line:

« la liberté qu’elle sent habiter hors d’elle-même, au delà. »

31 « L’extrême normalisation des maisons japonaises, qui ne provoque pas pour autant l’uniformité, intégrant totalement les corps de rangement à l’architecture, créant l’ordre et le vide dans le logis, m’obsédait. Pourquoi l’industrialisation de nos casiers normalisés en 1928 n’avait-elle jamais vu le jour? Pourquoi, même à l’intérieur de l’atelier Le Corbusier, ne furent-lis jamais retenus, à l’exception d’un projet en Argentine, la maison de Victoria Ocampo en 1930? Il y avait certainement des raisons: chaque architecte préférait-il marquer son œuvre par sa propre création, virus à l’occidentale communiqué depuis lors au Japon? Mais Corbu? Le module du rangement était-il trop grand? Ou bien ne laissait-il pas suffisamment de liberté dans la plasticité, dans la plasticité, dans le renouvellement des programmes? »

“The extreme normalization of Japanese houses, which does not provoke uniformity, totally integrating storage units with architecture, creating order and vacuum in the house, obsessed me. Why did the industrialization of our standardized cabinets in 1928 never come into realization? Why, even in the interior of the Atelier Le Corbusier, were they never selected, with the exception of a project in Argentina, Victoria Ocampo’s house in 1930? There were certainly reasons: each architect preferred to mark his work by his own creation, a Western virus communicated since then in Japan? But Corbu? Was the storage module too large? Or did he not leave enough freedom in the plasticity, in the renewal of the programs?”

32) « Il faut ici prendre position. Allons-nous faire du plein ou du vide ? Cette question, apparemment ridicule, a son importance. Pour certains, le vide c’est le néant ou l’indigence -, pour d’autres, la possibilité de penser et de se mouvoir. »

33 « … la conception de la totalité ne doit jamais se perdre dans celle de l’individualité. Et Laotsé le démontre par sa métaphore favorite du vide. Ce n’est que dans le vide, prétendait-il, que réside ce qui est vraiment essentiel. L’on trouvera, par exemple, la réalité d’une chambre dans l’espace libre clos par le toit et les murs, non dans le toit et les murs eux-mêmes. … Le vide est tout-puissant parce qu’il peut tout contenir. Dans le vide seul le mouvement devient possible. Celui qui pourrait faire de soi-même un vide où les autre pourraient librement pénétrer deviendrait maître de toutes les situations. Le tout peut toujours dominer la partie.

Ces idées taoïstes ont eu une très grande influence sur nos théories de l’action, même sur l’escrime et la lutte. Le jiu0jitsu, l’art japonais de la défense personnelle, doit son nom à un passage du Tao-teiking. Dans le jiu-jitsu, l’on s’efforce d’attirer et d’aspirer la force de l’adversaire par la non-résistance, c’est-à-dire le vide, tout en conservant sa propre force pour la lutte finale. Appliqué à l’art, ce principe essentiel se démontre par la valeur de la suggestion. En ne disant pas tout, l’artiste laisse au spectateur l’occasion de compléter son idée et c’est ainsi qu’un grand chef-œuvre retient irrésistiblement notre attention jusqu’à ce que nous croyions momentanément faire partie de lui. Il y a là un vide où nous pouvons pénétrer et que nous pouvons remplir de la mesure entière de notre émotion artistique. »

34 « une façade largement ouverte. »

35 « A l’intérieur, un équipement créant le vide. »

36 « murs utilitaires. »

37 However, on the other hand, Perriand denied the constant stability of such a “wall”.

« Car le mur japonais, comme la feuille de l’arbre est éphémère. Pleins et vides se remplacent les uns les autres en quelques instants, au grè des panneaux coulissants, qui s’ajoutent ou se retirent selon les caprices des nuages et les hasards de la température. » (AChP, Charlotte Perriand, L’habitation japonaise, 1949)

“Because the Japanese wall, as the sheet of the shaft is ephemeral. Fullness and vacuum replace each other in a few moments, by the sliding panels, which add to or withdraw according to the whims of the clouds and the hazards of the temperature.”

38 However, Perriand could not capture the “type” of the Japanese gesture in Teaism, which introduced the achievement of spiritual freedom or “mindlessness” (Minamoto 1989) because Okakura himself did not discuss it. In contrast, Le Corbusier prescribed the gesture as “type” (Le Corbusier Citation1930, 113).:

References

- Barsac, J. 2014. Charlotte Perriand, Complete Works, Volume 1 1903–1940. Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess.

- Barsac, J. 2015. Charlotte Perriand, Complete Works, Volume 2 1940–1955. Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess.

- Barsac, J. 2017. Charlotte Perriand, Complete Works, Volume 3 1956–1968. Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess.

- Barsac, J. 2018. Charlotte Perriand et le Japon. Paris: Norma Éditions.

- Kinoshita, N. 2015. Okakura Tenshin. Kyoto: Minervashobo.

- Le Corbusier. 1923. Vers une Architecture [Toward a New Architecture]. Paris: G. Crès et Cie.

- Le Corbusier. 1930. Précision sur un État Présent de L’architecture et de L’urbanisme [Precision on the Present State of Architecture and City Planning]. Paris: G. Crès et Cie.

- Le Corbusier, and P. Jeanneret. 1929. Œuvre complète 1910–1929 [Complete Work 1910–1929]. Zurich: Girsberger.

- Makino, M. 1929. “Talking about Le Corbusier, I Refer to Japan.” In Kokusai Kenchiku [International Architecture], 67–76.

- McLeod, M. 1987. “Furniture and Femininity.” The Architectural Review 1079: 43–46.

- Meech, J. 2001. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Art of Japan: The Architects Other Passion. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Ohkubo, T. 1987. Tenshin Okakura, Vacuum Full of Wonderful Light. Tokyo: Ozawashoten.

- Okakura, Kakuzo. 1927. Le Livre du Thé [The Book of Tea]. Translated by Gabriel Mourey. Paris: André Delpeuch, Éditeur.

- Perriand, C. 1935. “L’habitation Familiale, Son Développement Économique et Social [Family Housing, Its Economic and Social Development].” In L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui [The Architecture of Today], 25–32.

- Perriand, C. 1940a. Calepin Vert Japon [Green Notebook Japan]. Paris: AChP.

- Perriand, C. 1940b. Carnet Écru [Raw Notebook]. Paris: AChP.

- Perriand, C. 1942. “Contact Avec l’Art Japonais [Contact with Japanese Art].” Conference at the University in Indochina, published by the Secretariat of Intellectual Relations with neighboring countries of Indochina. Indochina: s.p.

- Perriand, C. 1949. L’Habitation Japonaise [Japanese Habitation]. Paris: AChP.

- Perriand, C. 1950. “L’art d’Habiter [The Art to Live In.” In Techniques et Architecture [Technique and Architecture], 9–10.

- Perriand, C. 1956. “Une Tradition Vivante [An Alive Tradition].” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui [The Architecture of Today 65: 14–19.

- Perriand, C. 1998. Une Vie de Création [A Creative Life]. Paris: Éditions Odile Jacob.

- Rüegg, A. 2012. Le Corbusier, Meubles Intérieurs 1905-1965 [Le Corbusier, Interior Furniture 1905–1965]. Zurich: Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess.

- Sendai, S. 2019. “The Conception of “Equipment” by Charlotte Perriand: Cross-over between Le Corbusier and Japan.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 18 (5): 430–438. doi:10.1080/13467581.2019.1678473.

- Sert, J. L. 1956. “Charlotte Perriand.” ‘Aujourd’hui, Art et Architecture [Today, Art and Architecture] 7: 58.

- Speidel, M. 2003. “Bruno Taut in Japan.” In Bruno Taut, Ich Liebe die Japanische Kultur: Kleine Schriften über Japan [Bruno Taut, I love the Japanese culture: Small writings about Japan], edited by M. Speidel, 7–39. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag.

- Taut, B. 1923. “Baugedanken Der Gegenwart [Building Thoughts of the Present].” In Bruno Taut in Magdeburg [Bruno Taut in Magdeburg]. Magdeburg: Landeshauptstadt Magdeburg.

- Taut, B. 1924. Die Neue Wohnung, Die Frau als Schöpferin [The New Apartment, the Woman as Creator]. Leipzig: Verlag Klinkhardt & Biermann.

- Taut, B. 1937. “‘Une Habitation Japonaise [Japanese Habitation].” In L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui [The Architecture of Today], 65–68.

- Taut, B. 2007. [Forgotten Japan]. Edited by Hideo Shinoda. Tokyo: Chuokoron-shinsha.

- Wakamatsu, E. 2013. [Reading of the Book of Tea by Tenshin Okakura]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten/.