ABSTRACT

In recent decades, increasing numbers of families with children are living in apartments in Australian cities; negotiating family life in dwellings not designed for their specific needs. This paper describes indirect participatory design research, involving architects and researchers acting as intermediates of end users, identifying how architects see that apartment design guidelines could be reconciled with the needs of families with children. Architects in Victoria, Australia, participated in a design workshop that elicited their views on child and family needs elucidated by research with families, explored Australian and international apartment design guidelines in relation to families, and which asked in light of this evidence – what needs to change in design guidelines to inform family-friendly apartment designs? Findings reveal important similarities and critical differences between architects’ and users’ views on apartment design for families with children. The paper concludes by discussing how these differences might be reconciled to ensure future apartment designs that suit a more diverse mix of households, including families with children. The challenges are also highlighted of using indirect participatory design when direct participatory design is not possible, including sacrificing the design consensus arising from architects and end users working together.

1. Introduction

Unlike in most Asian countries, Australian cities are still in the process of normalising apartment living. While apartments have historically been a temporary step towards the suburban housing market, families in Australia are now increasingly raising their children in apartments. Inner city renewal, employment opportunities close to city centres, housing costs, commuting times, and the increasing attractiveness of city entertainment and recreational offerings are among the many factors influencing families to choose apartment living. The strength of these drivers varies between and across cities and is also related to affordability, with many apartments in the middle ring of Sydney, for example, being built for those with limited means – detached housing being increasingly unaffordable – while apartments closer to the central business districts of Australian cities can be for those with much higher means (Randolph and Freestone Citation2012). The research also indicates debate about children in higher density housing that goes consumer preferences or affordability to encompass ideas about international investment and the ethics of housing supply (Raynor Citation2018). For example, the media and built-environment professionals have been seen to point to the direct influence of financing arrangements and investment decisions on the design and composition of apartments, an argument that “positions housing development as a reflection of investor appetite and reactions to risk rather than a consideration of occupier desires” (Raynor Citation2018, 1222).

The numbers of families raising children in higher density, inner city municipalities in Australian capital cities has increased from 50,000 in 2011 to 79,000 in 2016 (Szafraniec and Finney Citation2017). Families with children thus made up almost 44% of all family households living in apartments in 2016 (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2016). Despite this demographic shift, families with children living in apartments confront and are confronted by the long-held Australian perception and expectation that the ideal place for a family is the suburban single-family home (Birrell and Healy Citation2013; Raynor Citation2018). The legacy of this perception is a dominance of apartments which have been, and continue to be, designed and built for young professionals or empty nesters (Fincher Citation2007), with Whitzman and Mizrachi arguing that apartment designs “virtually ignore the needs of children and families” (Whitzman and Mizrachi Citation2009a, Citation2009b). While apartment living has many benefits for families, design that does not consider children as residents can create daily challenges for family functioning and wellbeing (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Easthope and Tice Citation2011). Indeed as Kerr, Klocker, and Gibson (Citation2020) note, many families expend a great deal of emotional energy and work in trying to ensure that their apartments mesh with the cultural norms associated with the creation of a “home” for themselves and their children.

This research builds and draws upon previous international evidence exploring parents’ experiences of raising children in apartment settings (Andrews and Warner Citation2019; Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Appold and Yuen Citation2007; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Dockery et al. Citation2013; Easthope and Tice Citation2011; Fincher Citation2007; Heenan Citation2017; Karsten Citation2015; Lilius Citation2014; Warner and Andrews Citation2019; Whitzman and Mizrachi Citation2009a, Citation2009b) by consulting with architects about designing apartments for families. It addresses an absence of industry perspectives in the literature by relating the lived experiences of residents with architects’ understanding of their needs. The research asks, how do architects see that apartment design guidelines can be reconciled with the needs of families with children? To answer this question, a form of indirect participatory design is followed.

User participation in design (otherwise known as participatory design) – a process which gives opportunities to both designers and users to express their ideas – is seen as essential for ecologically sustainable housing (Gustavsson and Elander Citation2016), facilitates users involvement in essential design decisions, and helps them express their living needs (Lee and Li Citation2011). Such participation can happen in the planning, design, construction or evaluation phases (Saleh Citation2006). Participatory design is “just as much about design – producing artifacts, systems, work organizations, and practical or tacit knowledge – as it is about research. In this methodology, design is research” (Spinuzzi Citation2005, 164), whereby the emerging design is iteratively constructed via co-interpretation “by the designer-researchers and the participants who will use the design” (Spinuzzi Citation2005, 164). Despite the importance of user participation, the absence of the user’s view in housing development is commonplace (Lee and Li Citation2011), reflecting the difficulty and complexity of conducting such research. As user participation is especially difficult in the current system of mass housing design and delivery, a role has been identified for indirect user participatory design processes to accommodate user needs, whereby “the identification, structuring, analysis, rationalization, and translation of user values is translated into relevant design attributes” (Moghimi et al. Citation2017, 77). This project uses such a process whereby data on families’ experiences is collected for translation to design attributes by architects and researchers.

Here it is important to briefly differentiate indirect from “direct” participatory design, the latter of which brings designers and users together to equalise power relations (through situation-based actions, mutual learning, tools and techniques, and alternative visions about technology), leading to expressions of equality and democratic practices (Luck Citation2018). In this project, end users are not directly involved in the evaluation of design choices. Instead, their voices are translated by researchers who are aiming to bridge power relations and thus help families with children move towards a position of greater equality in the design process. However, as we shall discuss, mutual learning is sacrificed here without the direct participation of the end user, for while the designers can “learn the realities of the users’ situation,” users are not able to “articulate their desired aims and learn appropriate technological means to obtain them” (Robertson and Simonsen Citation2012, 2).

Our findings reveal important similarities, but also critical differences, between architects’ and users’ views that elucidate better apartment design for families with children. These improvements can be categorised according to four scales of design issues: apartment, building, the city, and the planning process. While the research was conducted in Australia, the findings are informative for other locations with a similar apartment design legacy and might directly inform planning policies and design decision-making to ensure future apartments suit a more diverse mix of households.

First, this paper summarises the information presented to the architects participating in the research: previous research on Australian parents and their apartment living experiences – to generate a set of indirect user insights and an overview of existing design guidelines. This includes a brief review of international child and family-friendly apartment design guidelines. Next is described the process and findings of primary data collection undertaken via a design workshop with the architects, before the similarities and differences between resident’s and architect’s views are explained. Relating these findings to the best of international apartment design guidelines, the discussion concludes by identifying key opportunities for action.

2. Research context

The design workshop was introduced by a presentation summarising our detailed analysis of the literature. This analysis had two components: (1) review of international peer-reviewed and grey literature, published between 2000 and 2020, which revealed a range of design features that families raising children in apartments found challenging; and (2) a review of apartment guidelines globally that sought to highlight good practice in child- and family-friendly design. While a full description of these two spheres of review is beyond the scope of this paper, we include a summary here.

2.1. The impacts on families and children of high-density apartment living

The literature supports a growing interest in apartment living for families with children, highlighting its benefits in terms of affordability, proximity to parent’s employment and better work/family balance as well as access to services, facilities, and transport options (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Carroll et al. Citation2015; Ergler et al. Citation2015; Karsten Citation2009; Whitzman and Mizrachi Citation2012). Nevertheless, there are a range of apartment design features that are reported as being less supportive of family life.

Kitchens and bathrooms were particularly problematic; with families reporting limited space for preparing family meals (Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011), limited facilities for bathing young children and inadequate laundry facilities (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Easthope and Judd Citation2010). The sizes of living spaces were at times inadequate for a family (Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Karsten Citation2015; Nethercote and Horne Citation2016; Warner and Andrews Citation2019) and storage facilities insufficient (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Brydon Citation2014; Nethercote and Horne Citation2016; Scanlon Citation1998). While families recognised that private outdoor space was always going to be limited with apartment living, they were often disappointed with the design and useability of private balconies (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011).

Poor soundproofing was another reported problem, which caused stress for families both in terms of noise being a disturbance for their children’s sleep, as well as their children’s play disturbing their neighbours (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Kerr, Gibson, and Klocker Citation2018; Kerr, Klocker, and Gibson Citation2020; Warner and Andrews Citation2019; Whitzman and Mizrachi Citation2009a, Citation2009b).

Communal outdoor space was at times absent or unusable for children (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Whitzman and Mizrachi Citation2012). Beyond private and communal spaces in the apartment building, families also highlighted missed opportunities for community engagement resulting from the poor design on the ground floor interface between their complexes and the wider community (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Scanlon Citation1998; Tavakoli Citation2017).

The literature also highlighted potentially dangerous design features for families with young children; including window and balcony design, along with the design of car parking and drop off zones (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Easthope and Judd Citation2010; Istre et al. Citation2003). Finally, families argued for their apartment complexes to be located close to green space, shops and schools (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll et al. Citation2015; Enns Citation2010; Ergler, Kearns, and Witten Citation2013; Karsten Citation2009; Smith and Kotsanas Citation2014; Tavakoli Citation2017).

It is important to note some limitations with the literature. First, while cultural differences are evident in parents’ ways of dealing with children at home, more similarities than variation have been found between Caucasian, African American, Hispanic and Asian American parenting (Julian, McKenry, and McKelvey Citation1994). While the “family with children” model is clearly not homogeneous (Baker Citation2012), reflected by varying habits, opinions and ways of living, the implications of these differences on dwelling design are not well understood or evidenced. Recognising that families with children have diverse needs between families is important, but as Kalantari and Shepley’s review of the psychological and social impacts of high-rise buildings concludes, further research is needed to identify cultural preferences in relation to effective apartment design (Kalantari and Shepley Citation2020).

Further, it is worth noting that most studies focus on parent’s perspectives and thus children’s views are largely absent in terms of “understanding what is necessary to create inclusivity and towards addressing the inequity faced by young children in their environments” (Nordstrom Citation2010; Smith and Kotsanas Citation2014, 187).

2.2. Child- and family-friendly design guidelines

There has recently been an increase in the number of cities around the globe adopting child-friendly policies. Most focus on safety, play, and independent mobility in public streets and spaces rather than dwelling design. A small number of child-friendly city policies engage with or influence apartment design. For example, the Mayor of London’s supplementary planning guidance Shaping Neighbourhoods: play and informal recreation (Citation2012) specifies minimum site and neighbourhood requirements for play spaces and recreation amenities to be integrated into urban housing developments). So too the City of Toronto, Canada’s Draft Urban Design Guidelines – Growing Up: Planning for Children in New Vertical Communities (City of Toronto Citation2017) – which is applied City-wide to all new multi-residential mid-rise and tall building development applications that include 20 units or more – presents a collection of best-practices that accommodate people of all ages and abilities.

Institutions from other countries have also produced extensive documentation on the theme of apartment design for varied household profiles. In France, for instance, the praxis of producing academic research on housing together with architecture firms and developers dates from the 1980s; giving rise to design competitions that sought to bring about new ideas and create conditions for building the awarded projects. Out of this movement, Europan – a platform and tool that brings together academics, designers, and other industry stakeholders – holds biennial competitions for young architects to design innovative housing schemes for sites across Europe. Europan 10, for example, was won in 2009 by the project Garden>Hof: A Grid a Gardens (Europan Europe Citation2021), which was designed around notions of scale, diversity, individuality, and space. The scheme reflects debate around the respect for the individuality of children, adolescents, and elderly people spending more time at home.

While our research recognised the importance of neighbourhood and city guidelines in the creation of child-friendly cities, our primary focus was on guidelines for the design of apartments and the communal amenities they share. We noted that guidelines could be divided into four types (); those: (1) specific to child- and family-friendly apartments (e.g., (City of Toronto Citation2017; City of Vancouver Citation1992)); (2) with child- and family-friendly features (e.g. (City of Emeryville Citation2010; DHPLG (Republic-of-Irelend) Citation2018); (3) produced by Social and Community Housing Providers (e.g., (Government of South Australia Citation2016); and (4) with alternative approaches to minimum space standards (e.g., (NSW Department of Planning and Environment Citation2015; Woolcock, Gleeson, and Randolph Citation2010). In addition, key features of good practice were identified in relation to: (1) design scales, (2) type (descriptive, prescriptive, and/or performance based), (3) minimum dwelling size and space standards; (4) dwelling type and size diversity, (5) flexibility, and (6) accommodating behaviours and their needs.

Table 1. Selected family-friendly international and Australian apartment design guidelines.

From this review of the international literature on design standards, a range of dimensions and models of best practice were distilled:

2.3. Design scales

Housing satisfaction in apartments is multi-scalar, with most literature referring to a three or four level design scale ranging from the city to the apartment. The guidelines that best embrace the needs of families take a holistic approach rather than targeting a single metric for change; provided guidance across design scales and avoided reinforcing distinctions between private sites and the public spaces between them.

2.4. Type (descriptive, prescriptive, and/or performance based)

Guidelines are either prescriptive (stating required space or utility dimensions), descriptive (indicating an intention or describing a desired qualitative outcome) or performance-based – which “outline the objectives to be achieved, often paired with guidance to help realise the objectives, but where innovative design solutions may be applied to satisfy the ‘qualitative intent’ of the objective” (Foster et al. Citation2020, 3). While prescriptive guidelines effectively avoid poor outcomes but seldom promote innovation in design, performance-based guidelines are more likely to promote best practice. Best practice might be a combination of prescriptive and performance-based guidelines.

2.5. Minimum dwelling size and space standards

While some design guidelines implement minimum dwelling sizes, those with clearer focus on user needs prioritize the accommodation of activities which are both essential to and enrich residents’ lives in apartments over the provision of minimum space dimensions, and recognise that the spatial needs of living, dining and kitchen vary with numbers of occupants. Design flexibility might also recognise the different sleeping and recreation space requirements of different aged children by accommodating these changes over time.

2.6. Dwelling type and size diversity

Multiple researchers evidence the social benefits for all residents, including children and families, of diverse household types in developments (Barros et al. Citation2019; Karsten Citation2015; Martel et al. Citation2013). Guidelines towards this purpose can be advisory, prescribed, or incentivised, and should promote a diversity of dwelling types, consider incentives to encourage family-sized units, and establish mechanisms or guidance to encourage building above the minimum standard.

2.7. Flexibility

To be child- and family-friendly, guidelines encourage design flexibility that is adaptable to changing life stages and allow for the design of less specific spaces.

2.8. Accommodating behaviours and their needs

To be child- and family-friendly, design guidelines will ideally: be conscious of the activities likely to be undertaken by residents in different spaces and ensure these can be appropriately accommodated, recognise that resident activities extend across all design scales, and ensure prescriptive guidelines, where used, reflect the spatial needs of residents’ activities and behaviours.

Thus, after analysis of families’ experiences of apartment living, and a selection of apartment design guidelines, an array of practices emerged; some that might be considered good practice, and others less attuned to the needs of families. These practices and user experiences were then presented to our sample of Victorian architects, in the context of this state’s specific design guidelines, to be evaluated with the researchers against current design practice in a process of indirect user participatory design. Here, convergences and divergences emerged between the architects and families, partly reflecting, as we shall discuss, the distance in the methodology between users and designers.

3. Method

Primary data collection was undertaken in Melbourne, Australia, in 2020. A design charrette was originally planned using collaborative graphic communication activities to stimulate the exchange of ideas. However, restrictions imposed by COVID-19 required adaptation to an online format. The 3-hour session was structured by a series of four activities with visual material used to prompt interaction and design discussion. The design workshop was facilitated by a three-person research team representing and able to synthesise the cross-disciplinarity of the issues under consideration: one from the field of health (specifically healthy built environments), one from planning and the other from architecture (who had previously practiced as an architect).

Seven architects (four women and three men) were recruited who are highly experienced in the design and development of Victorian apartment buildings and who are considered leaders in their field willing to push the boundaries of conventional apartment design. The participants have each led the design and delivery of apartment buildings in Australia through a variety of procurement processes. They were selected after a call for designers in the area willing to challenge design norms. While a reputation for design innovation was key to the selection of these architects, diversity was also important so that their views had cross-sectional currency. Thus, they included diversity of time in the industry, architects from large and medium practices, a sex balance, and architects with cultural backgrounds from other countries or minorities (Australian, European, and Asian). As the aim of the research was to explore architect’s professional stance on child-friendly design, participants were not required to have children themselves.

While the data collected from only seven architects cannot be said to constitute a representative sample of industry opinion, participants were able to provide diverse expert and thought-provoking reflection and opportunity identification. Three participants had experience of being residents and parents and another spent their childhood in a culture where apartment dwelling families are the norm. These experiences were heightened by the timing of the workshop following a period of atypical occupation of dwellings due to COVID-19, with work-at-home protocols and home-schooling in place across Victoria. The session was audio and video recorded and transcribed using a digital conferencing tool, with organisational ethics approval given. One of the research team undertook an initial analysis of the transcript. Findings were then discussed and further analysed with the two further members of the team who had helped to run the workshop to arrive at consensus regarding the key research findings. The first of the four activities – Family Apartment Life- Professional Perspectives – sought the architects’ perspectives on user experiences of family apartment life. The later three activities focused on (2) impacts of the regulatory context for apartment design, (3) reflections on global good practice, and (4) suggestions for change towards more family-friendly apartments.

3.1. Family apartment life- professional perspectives

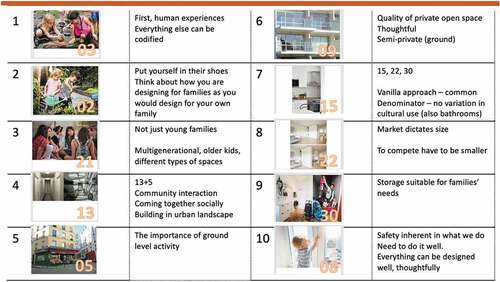

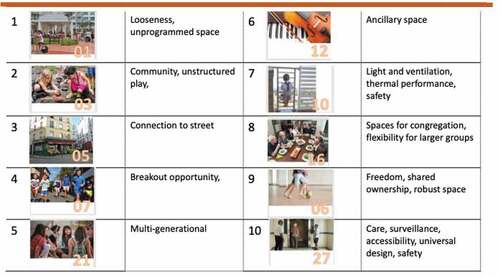

The first activity was undertaken in two concurrent groups and commenced with the sharing of 35 images selected by the researchers to represent the end-user experiences of family apartment life as identified through the literature review. Participants were shown the numbered images without commentary or explanation of the resident experiences from which they were drawn, leaving room for interpretation and discussion. After viewing all images participants were asked to identify those which they saw as representing the most important aspects of family living in apartments and state why. This continued until 10 images were selected by the group. The selected images were then “ranked” from most to least important, a process requiring discussion and exchange of opinions between participants, eliciting both individual and collective views. The result of the image selection and ranking are included in . It is notable that each set of rankings is quite different; a result we shall return to in our discussion.

3.2. Impacts of the regulatory context for apartment design

The second activity sought to elicit the participants’ views on the regulatory design context for apartment design in Victoria in relation to children and families and was conducted in two groups.

3.3. Reflections on global good practice

This activity introduced the participants to features of international good practice for child- and family-friendly apartment design guidelines. The international examples included guidelines specific to family-friendly apartment design (e.g. in Canada; Toronto (City of Toronto Citation2017) and Vancouver (City of Vancouver Citation1992) alongside others which are more general but include child and family friendly components (e.g., The Republic of Ireland (DHPLG (Republic-of-Irelend) Citation2018) and Emeryville, USA (City of Emeryville Citation2010). The guidelines were described in relation to four key characteristics: design scale, guideline type, conceptualisations of minimum space standards (including internal and external communal amenities), and requirements for dwelling type and size diversity. The participants were asked to express their views on the guidelines, including comparison with current Australian guidelines.

3.4. Suggestions for change

The final workshop activity sought to summarise the outcomes of the workshop and asked participants to identify additional issues.

4. Results

Participants indicated that selecting the “most important” aspects of families living in apartments (Activity 1) was a challenge as they preferred to conceptualise how these issues work together in combination. In the process of ranking the images the following observations were made by participants:

Safety is an inherently considered prerequisite to the design process as it is part of professional responsibility in all scenarios, not just relative to families in apartments;

The most important design considerations are those regarding human experience, but these can be some of the hardest things to retain through the value management phase of development. Images selected were relatively equally distributed between issues related to use and issues related to design; and

Very few items relative to unit design were selected: “we are prioritising things outside the apartment” noted one participant. This is worthy of comment in that design guidelines relate to the dwelling configuration alone whereas life does not.

In selecting images, participants commented that some of the images were about human behaviour and expectations, not directly about dwelling or building design. One workshop group explicitly observed they had not selected images about changing people’s perceptions of living together, such as noise and pets, as they are about behaviour and expectations; not design. The outcomes from Activity 1 are collated in .

Table 2. Most important items of family life in apartments from the perspective of design architects.

In combination the second and third activities provide insight from the participant’s professional experiences of working with apartment design guidelines, with this being further informed by their responses to suggestions for change provided in the final activity. Participants described the introduction of State apartment design guidelines as, overall, a positive intervention to counteract low design standards, and agreed that their presence is an improvement on when there were no such standards in place. Reflecting on past and current projects, participants shared their experiences of how the regulatory context for apartment design has influenced design, both to the benefit and detriment of how built outcomes meet the needs of families. In general, however, the participants expressed frustration with the rigidity of the guidelines regarding minimum room and space dimensions. They expressed preference for greater flexibility to enable apartment designs that can address changes in social norms and behaviours, give capacity for modifications of layouts over time and allow for a re-balancing of space between sleeping and living activities. They also challenged the requirements for private open space, typically small balconies lacking usefulness, proposing an option for well-designed communal spaces and generally more shared amenity.

The international design guidelines introduced to the participants provided examples of how these challenges, and others, have been approached in different locations. One feature of the guidelines that received strong responses from participants was that of design scales and how these relate to policies and guidelines in different locations. They suggested embracing a gradient of stringency across scales, commencing with highly prescriptive policies at the neighbourhood scale (to reduce uncertainty for landowners and developers) and progressing toward less prescriptive at the unit or apartment scale to allow for personalisation and changes in social norms. On the importance of ancillary spaces to apartment living, participants expressed caution about placing excessive demands on individual developments for communal amenity.

Having discussed both Australian and international apartment design guidelines, participants reinforced the importance of guidelines in informing good design and amenity while also recognising that guidelines often set minimum standards which developers seldom exceed. Participants acknowledged that in relation to apartment development in Australia there are currently two distinct markets, the non-resident investor (or landlord) and the owner occupier. The needs of the larger market, the non-resident investor, are targeted by developers and, as one participating architect suggested “what is best for an investor (or landlord) is not suitable for families.” While it might be countered that design appealing to families would surely increase the demand for investors’ properties, the architects’ views here echo a market that to date has not been focused on families. However, as the owner-occupier segment of the market is increasing, it is essential apartment design guidelines avoid stifling innovation or restricting the ability for apartment design to evolve to respond to changing market demands.

Participants supported the inclusion of objectives specifically for families and children living in apartments, with clear preference for inclusion in general apartment design guidelines and policies rather than as separate documents. Four key suggestions were arrived at via consensus:

Local governments can instigate change by determining the most appropriate sites for family apartments, such as overlooking a park, and provide compensation or incentives for including family-friendly apartments on these sites;

Recognising efficiencies of scale, the architects saw the need for a threshold for development sizes above which any family- and child- friendly guidelines, such as dwelling diversity requirements or communal facilities, should apply;

The provision of outdoor communal amenity should apply to all apartment buildings, not just large developments, as smaller communities appeal to families and these can ensure that passive surveillance as well as play spaces become available to the children who occupy the building; and

In pursuit of flexibility and adaptability, apartment design guidelines should:

set an overall area for an apartment which can be planned and divided by the designer rather than specify minimum room sizes. This would allow, for example, reductions in bedroom sizes if the space is returned to the net total of the floor area, allowing communal areas of apartments to be more generous;

recognise developments with a high level of good quality interior and exterior communal facilities, offer residents amenity advantages such that overall floor areas of individual dwellings can be appropriately reduced; allowing layouts which do not comply with the prescribed standards provided it can be demonstrated that standards can be met without major modification if desired in the future;

be less specific about function of individual rooms to allow them to be used in different arrangements over time; and

outline a procedure for assessing the quality and amenity of alternative design propositions, recognising a suitable knowledge base is necessary to do so.

The workshop concluded by the architects providing additional thoughts. These were mainly concerned with aspects beyond their control, emphasising the need to challenge the current system of supply by showcasing exemplars of innovative, affordable, high density, family-friendly living.

5. Discussion

While it is widely recognised that the existing apartment stock in countries such as Australia, with a limited history of apartment living, does not meet the needs of parents with children, to our knowledge the views of architects have not been sought on this problem. Here, we discuss the priorities expressed by the architects in our workshop via a reconciliation of design practice and guidelines with the experiences of families. The comparison focuses on three areas: the similarities and differences of architects’ and residents’ views, how these key issues manifest in the research and design guidelines, and how they might be reconciled. We then discuss the limitations of the research, relating the findings to the indirect nature of the participatory design process followed.

5.1. Comparing architects’ and residents’ views

Overall, we found there was a degree of congruence between architects’ views on what constituted a family-friendly apartment design and parents’ experiences. This may reflect the architects’ experiences in the design and delivery of more innovative apartment buildings, as well as the fact several were raising young children in apartments themselves. This congruence was clear in the desire for designs that foster community interaction within apartment complexes and, especially, with the wider neighbourhood context. For example, both parents (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019) and architects identified the need for complexes to include functions at the ground floor complex/street interface that enhance interaction among residents and between residents and their surrounding neighbours (e.g., open space, cafes, restaurants, general stores). To facilitate this integration, the architects stressed the need to design apartment complexes in relation to their location, neighbourhood character and facilities. Similarly, parents wanted apartment complexes to be close to parks, shops, and schools (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll et al. Citation2015; Ergler et al. Citation2015; Karsten Citation2009; Smith and Kotsanas Citation2014).

A further area of congruence was the need for flexibility to allow for personalisation of space to support diverse needs. Lack of flexibility was highlighted by architects and parents alike as resulting in the spatial and storage constraints that plague families in apartment buildings (Andrews and Warner Citation2019; Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Nethercote and Horne Citation2016). Thus, the architects called for guidelines offering greater flexibility around minimum room sizes and room allocation to allow use in different arrangements over time. There was also an opportunity recognised for architects to learn directly from families’ modifications to their apartments to better support their everyday life.

There were, however, key areas of dissonance between families and architects’ perspectives. For example, although architects identified safety in design features as one of their priorities for child-friendly apartments, there was an assumption that this was “inherent”. Unfortunately, parents identified that this was not always the case. For example, while regulations might stipulate window locks, these could be overridden to overcome poor apartment ventilation (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019). There has also been research to indicate the importance of safe spaces for children to play, within the apartment building and close by, in particular those that can be overlooked by ground floor apartments (Easthope and Tice Citation2011). Lack of detailed consideration of children here is an example of where pure compliance falls short of the demands of family life. Furthermore, an area not highlighted by architects was the issue of sound proofing; a key issue for parents raising young children in apartments in the literature (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Kerr, Gibson, and Klocker Citation2018; Kerr, Klocker, and Gibson Citation2020; Whitzman and Mizrachi Citation2009a, Citation2009b). Tellingly, the architects noted that images illustrating noise issues were about changing people’s perceptions of living together, thus relating to adapting resident behaviour and expectations, rather than to adapting design to resident needs. In sum, two key points of congruence (desire for community interaction and for flexibility) and two points of dissonance (safety and noise) were found. Here we relate these to the research literature and to Australian and international apartment design guidelines.

5.2. Safety and noise

The research on noise transmission impacting family life relates to activities taking place either outside or inside apartments. Noise emanating externally from the balconies of other residents has been identified as disturbing children’s sleep (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019) while, conversely, studies have documented issues with parents needing to manage the noise created by children due to poor apartment soundproofing (Kerr, Gibson, and Klocker Citation2018; Kerr, Klocker, and Gibson Citation2020). A UK study found some design features could assist in these issues, with effective insulation, solid walls and considered design resulting in low noise transmission (Mulholland Citation2003). Design to address noise transmission also included positioning hallways and kitchens to abut party walls, with living rooms and bedrooms situated further away. However, it was the combination of these design features that were most effective. The ability to use communal areas was also found to be curtailed by the noise generated by play (Scanlon Citation1998). In particular, the central positioning of communal areas in courtyards or atria can create an “echo chamber” for noise (Scanlon Citation1998).

As indicated by the architects in our study, the regulatory hierarchy of construction standards over apartment design guidelines with regards to noise is generally reflected in Australia and globally by lack of enforceable internal transmission performance standards in apartment guidelines. While architects see these construction standards as sufficient, the feedback from families living in apartments would suggest that this is an issue requiring much further attention.

The architects in our study were clear that the safety of children is inherent to the design processes and is part of their professional responsibility in all scenarios, not just relative to families in apartments. Indeed, in Australia and internationally, design for all buildings must comply with codes and standards on safety. However, the safety of children and the proximity of other residents is arguably most challenging in the apartment context. In some instances, contradictions between codes and standards can compromise the effectiveness of each to achieve their intent. One example is when windows required for ventilation are compromised by the need to install opening limiters to prevent falls. Clearly, windows should enable adequate ventilation without having to circumvent window locks or leave doors open, which compromises safety. Perhaps uniquely amongst the apartment guidelines reviewed, the City of Emeryville, California, Emeryville Design Guidelines, makes specific childhood safety recommendations, stating that units should be designed “with infant and toddler safety in mind (e.g., stairs that easily accept toddler gates, no glass room dividers, and ability to add child safety devices or window locks to prevent toddlers from climbing out of windows)” (City of Emeryville Citation2010, 69). The concern of parents for child safety during play, preferably within the building precincts was only noted in passing by the architects. It is also something that is not often considered within design guides with only the South Australian social housing guidelines specifying that passive surveillance should be built into the location of large, ground floor apartments overlooking open spaces (Government of South Australia Citation2016).

The architects’ collective blind spot here about families’ needs in relation to soundproofing and safety is worth comment, for it may reflect a hierarchy of their own knowledge over user experience that is clearly unchallenged by a participatory design process that does not directly involve families.

5.3. Design for community interaction

The architects firmly agreed with parents that the design of apartments should foster community interaction. Consistent with research on social isolation in apartments, the architects suggested that community interaction should be considered at the building and the neighbourhood scale. They also suggested changing guidelines so that the provision of outdoor communal amenity should apply to all apartment buildings, not just large developments.

At the building scale, Krysiak (Citation2019) found that large corridors with natural light, ventilation and lobbies with study nooks increased a sense of community for families living in apartments. A Canadian study (Tavakoli Citation2017) supported this finding, adding centrally positioned elevators, external walkways, space for storage, and space for sharing of children’s toys, books or camping equipment also increased social connection. Additionally, allowing personalisation of these spaces, through artwork for example, increased a feeling of community ownership (Krysiak Citation2019). Further, the importance of well-designed communal areas to increase perceptions of community, privacy, safety and friendliness was highlighted for families living in Australia, the UK and Canada (Krysiak Citation2019; Mulholland Citation2003; Tavakoli Citation2017). Features that facilitated this included multiple communal spaces, as well as spaces large enough for public and private events and for children to play. Outdoor covered spaces were also found to be particularly successful for promoting a sense of community if they were connected to a larger outdoor courtyard and enabled the passive surveillance of children (Krysiak Citation2019). These studies stressed the need for greenery and playable elements within these spaces to encourage social connections (Krysiak Citation2019; Tavakoli Citation2017).

At the neighbourhood scale, families can feel cut-off from the outside world in apartments that have no relation to their surrounding neighbourhoods. This is supported by observations that access to indoor public spaces, such as cafes, appear to be important ways for families with children in apartments to socialise. A Canadian study evidenced this, finding the incorporation of business within the building, such as a coffee shop or grocery store, and other intentional spaces, such as dog or bike washing stations and workshops, promoted social connection between families and neighbours (Tavakoli Citation2017). These features also appealed to children living in Melbourne (Whitzman Citation2010).

Most child- and family- friendly apartment guidelines do not address the scale of the neighbourhood, acting predominately within the boundaries of the given site. Globally, a number of cities have adopted Child-friendly City policies in recent years which do address design, interactions and (safe) play on public streets and in public places (see for example London (Mayor of London Citation2012, Citation2019), and Rotterdam (City of Rotterdam D.Y.E.S., Citation2010)), but do not address building or dwelling design directly. In relation to encouraging social interaction, building and apartment design scales remain relatively unaddressed, missing the many opportunities that exist at the building level to support and enrich community and family life in apartments. In Australia, the notion of community interaction within an apartment complex and between them and the wider neighbourhood context is largely neglected.

5.4. Flexibility of design to support diversity

The architects firmly agreed with parents that greater guideline flexibility might inform design that is more inclusive of the needs of families with children. For example, the architects identified the need to provide both indoor and outdoor family-friendly communal spaces that were unstructured, flexible and able to accommodate a diversity of age groups; thus supporting the findings on parents’ views on outdoor space (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011; Karsten Citation2015; Whitzman & Mizrachi, Citation2012). Poor design of private space was a further area of congruence. Parents highlighted that balcony space was often unusable due to overlooking (Andrews, Warner, and Robson Citation2019; Carroll, Witten, and Kearns Citation2011), with architects arguing the need for quality and flexible balcony space.

The challenges of spatial and storage constraints were highlighted by both architects and parents, with architects identifying the need for flexibility in design to allow for personalisation of space to support a diversity of apartment residents. This included changes to the guidelines in relation to minimum room sizes and allocation of functions to better facilitate changes of use over time. Obstacles to change identified by the architects here included lack of stakeholder knowledge about exemplars or design that breaks the norm. An example highlighted by one architect described a “capsule bedroom at one end and a huge, open flexible space for the rest of the apartment.” However, while such exemplars are known to architects, evidence of their efficacy is limited in the research literature. While Iranian examples have been highlighted, with spaces that combine and separate from each to offer different degrees of privacy (Shabani et al. Citation2010), and in Korea flexible living room cabinets have been proposed that can be adapted according to life styles and furniture uses (Jang and Kim Citation2007), there is no user evaluation of these and the vast majority of other precedents. Vernacular examples too can be drawn on that through centuries of iteration might be said to be user validated. For example, traditional Malay housing, associated with social, cultural patterns and religious values, is characterised by inherent spatial flexibility (Rahim and Hassan Citation2011), and traditional courtyard housing in Iran is recognised as adaptable to family requirements over time (Arjmandi et al. Citation2010; Shabani et al. Citation2010).

It should be noted that more detailed aspects of flexibility were not discussed, such as: initial or permanent flexibility, the necessary durability of architectural elements and construction components that can limit or facilitate flexibility during the building’s life cycle, or possibilities through furniture design or by reconfiguring spaces. If these issues are related to personal design references, and if technical, construction or cost imperatives, for instance, are considered, perhaps the consensus around flexibility would be less clear.

In sum, architect and user experiences align to suggest the useful addition in guidelines of a focus on the diverse array of residents that live in apartments – singles, couples, groups, families with children and multigenerational households – which aims to maximise useability of built environments for all people without the need for specialised design. This finding aligns with similar calls for more inclusive design, for example through a greater focus on women’s needs so that planners, developers and other professionals are given impetus “to look beyond the investor driven stock currently provided to ensure sustainable and liveable housing options” (Reid, Lloyd, and O’Brien Citation2017, 16).

6. Conclusion and limitations

As with all research, there are limitations to the study. First, the study had to modify a face-to-face design process to an online workshop due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, this medium proved a useful method for rich data collection as well as being convenient for participants. Second, the study employed a small sample of architects that while diverse cannot be said to represent a profession in general that has widely divergent opinions of how design might meet user needs. Similarly, while the findings highlight congruencies and dissonances between architects and residents, the methodology was not able to reflect the fact that both groups are not homogeneous. This weakness highlights the need for future research with a wider audience of architects, as well as the inclusion of other disciplines such as planners in fine-tuning policy and practice to better support families raising children in apartments.

Lastly, while our findings address a knowledge gap relevant to practice and to the academic community, since families’ experiences were made available through indirect sources, with the researchers acting as intermediates to and facilitators of architects’ reflections on these experiences, the opinion of these seven architects might be considered more of a provocation to inform change rather than a scientific contribution. Moreover, the indirect nature of the participatory design process employed points to other methodological limitations. Participatory approaches with architects and users are difficult in housing contexts, and this is especially so when the context is general – i.e., on the guidelines for designing all apartments rather than on the design of an apartment complex for known users. In such a context, user experiences can only be representative of families in general and so cannot reflect the diverse and nuanced needs of individual families. However, the lack of direct communication between designers and users is reflected in the dissonance between opinions that we highlight; differences that might have been better resolved through a process of consensus. Indeed, lack of consensus is even reflected in the difference of opinions between two groups of architects on what might be most important for families (). With such subjectivity so apparent in design, these findings suggest that while indirect participatory design has its place in a generalised enquiry when end users cannot directly participate in the design process, it cannot and should not replace participatory design between architects and users. For without users, a key benefit of the participatory design process – mutual learning – is lost. Without mutual learning, users lose the opportunity to learn appropriate means to obtain their needs, and both parties miss out on arriving at equitable design outcomes through a process of design consensus.

Thus, subsequent work to the design workshops reported in this paper has developed the project findings to inform an international competition design brief for future apartment design better able to address the diverse needs of residents now and into the future. The research team is consulting with the competition winners and aims to evaluate the resultant designs via participatory design, by helping the teams co-design and co-evaluate the built outcomes with potential and then actual residents.

In conclusion, this paper reported on an indirect participatory design process involving a workshop with a group of Australian architects that explored child and family needs in apartment living, and Australian and international apartment design guidelines in relation to children and families. The study asked: how do architects see that apartment design guidelines can be reconciled with the needs of families with children? Findings indicated a degree of congruence between architects’ views on what constituted a family-friendly apartment design and parents’ experiences, especially in relation to design that fosters social interaction and the need for design flexibility. Notable areas of dissonance around soundproofing and safety related to architects’ views that these issues were inherent to design. There is therefore scope for change around the ways in which soundproofing is considered – not only between buildings and their environment but within the apartment complex and individual units – as well as safety, with issues around windows, car movement, passive surveillance and accessing adjacent areas highlighted as needing more consideration in guidelines. Architects embraced several features from international exemplar guidelines, supporting the inclusion of objectives specifically for families and children living in apartments, with a preference for inclusion in general apartment design guidelines and policies rather than as separate documents. Finally, architects highlighted the need to work across disciplines to achieve these outcomes. The need for future research is identified: with a wider audience of stakeholders, on clarifying the impact of cultural differences, and on co-design and co-evaluation with families. The importance is also highlighted of participatory design, where users and architects work together to build consensus.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard Tucker

Professor Richard Tucker has published approaching 100 outputs on sustainable and universal design, urban design, and relationships between health, accessibility and inclusivity in built environment design.Richard is a director of the HOME Research hub; an interdisciplinary group of 30 Deakin researchers that works with local communities, to co-design solutions to complex housing problems.His work is founded on the efficacy of cross-disciplinary teamwork; research with over 80 colleagues from seven academic institutions and a dozen industry partners. His research is focused on transdisciplinary approaches for built environment research; at the intersection of sustainable design, planning, health and housing.

Fiona Andrews

Dr Fiona Andrews, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer at Deakin University, School of Health and Social Development, Co-Leader of the Deakin Research Hub HOME, and a member of the Centre for Health through Action on Social Exclusion (CHASE). She has research interests and publications on the relationship between neighbourhoods, housing, health and families, with a particular focus on parents of preschool-aged children. She lectures on healthy cities; family health and well-being; health, place and planning.

Louise Johnson

Professor Louise Johnson is an Honorary Professor at Deakin University and Honorary (Professorial Fellow) at the University of Melbourne. She taught for over 40 years in Australian and New Zealand universities and has a solid record of research, policy development, leadership and community activism. A human geographer, she has researched Geelong’s textile industry, displaced car industry workers, women in the service sector, the growth of the creative industries and most recently analysed the city’s economic resilience and socio-spatial disadvantage. As well as generating over 120 publications, this work has informed policy development and underpins her role in Northern Futures and on the City’s Affordable Social Housing Advisory Committee. In 2011 she received the Institute of Australian Geographers Australia and International Medal for her contribution to urban, social and cultural geography.

Jasmine Palmer

Dr Jasmine Palmer with a background in architecture practice, Jamine’s teaching and research are both framed by an ongoing interest in the generation of 'sustainable urban futures,' a broad-reaching agenda which embraces multiple scales and disciplines. Having studied in the fields of Arts, Architecture, Design Science, Sustainability, and Social Sciences, she takes a multi-disciplinary view of sustainability challenges. She is currently extending my research in the field of self-organised housing, employing actor-network theory, visual mapping, and comparative analysis to understand complex systems of housing provision and appropriate means of disrupting existant, dominant housing regimes. Her ambition is to provide knowledge which contributes to a more equitable and sustainable housing future for all.

References

- Andrews, F., and E. Warner. 2019. “‘Living outside the House’: How Families Raising Young Children in New, Private High-rise Developments Experience Their Local Environment.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability. doi:10.1080/17549175.2019.1696387.

- Andrews, F., E. Warner, and B. Robson. 2019. “High-rise Parenting: Experiences of Families in Private, High-rise Housing in Inner City Melbourne and Implications for Children’s Health.” Cities & Health 3 (1–2): 158–168. doi:10.1080/23748834.2018.1483711.

- Appold, S., and B. Yuen. 2007. “Families in Flats, Revisited.” Urban Studies 44 (3): 569–589. doi:10.1080/00420980601131860.

- Arjmandi, H., M. Tahir, A. Che-Ani, N. Abdullah, and I. Usman. 2010. “Application of Transparency to Increase Day-Lighting Level of Interior Spaces of Dwellings in Tehran-A Lesson from the Past.” Selected Topics in Power Systems and Remote Sensing 297–307.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016. “Census of Population and Housing.” https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/Home/Census?OpenDocument&ref=topBar

- Baker, K. K. 2012. “Homogenous Rules for Heterogeneous Families: The Standardization of Family Law When There is No Standard Family.” University of Illinois Law Review 319.

- Barros, P., L. N. Fat, L. M. Garcia, A. D. Slovic, N. Thomopoulos, T. H. de Sá, … J. S. Mindell. 2019. “Social Consequences and Mental Health Outcomes of Living in High-rise Residential Buildings and the Influence of Planning, Urban Design and Architectural Decisions: A Systematic Review.” Cities 93: 263–272. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.05.015.

- Birrell, B., and E. Healy. 2013. Melbourne’s High Rise Apartment Boom. Melbourne: Centre for Population and Urban Research, Monash University.

- Brydon, A. 2014. Families in the City. University of Melbourne, Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning.

- Carroll, P., K. Witten, and R. Kearns. 2011. “Housing Intensification in Auckland, New Zealand: Implications for Children and Families.” Housing Studies 26 (3): 353–367. doi:10.1080/02673037.2011.542096.

- Carroll, P., K. Witten, R. Kearns, and P. Donovan. 2015. “Kids in the City: Children’s Use and Experiences of Urban Neighbourhoods in Auckland, New Zealand.” Journal of Urban Design 20 (4): 417–436. doi:10.1080/13574809.2015.1044504.

- City of Emeryville. 2010. “Emeryville Design Guidelines.” Retrieved from San Franciso, CA: https://www.ci.emeryville.ca.us/DocumentCenter/View/1193/Design-Guidelines-05192015?bidId=

- City of Rotterdam D.Y.E.S. 2010. Child Friendly Rotterdam. Retrieved from Rotterdam, Netherlands:.

- City of Toronto. 2017. “Growing Up: Planning for Children in New Vertical Communities Guidelines.” https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2020/ph/bgrd/backgroundfile-148362.pdf

- City of Vancouver. 1992. “High Density Housing for Families with Children Guidelines.” https://guidelines.vancouver.ca/H004.pdf

- DHPLG (Republic-of-Irelend). 2018. “Sustainable Urban Housing: Design Standards for New Apartments.” Retrieved from Dublin: https://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/publications/files/design_standards_for_new_apartments_-_guidelines_for_planning_authorities_2018.pdf

- Dockery, A. M., R. Ong, S. Colquhoun, J. Li, and G. Kendall. 2013. Housing and Children’s Development and Wellbeing: Evidence from Australian Data. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Melbourne.

- Easthope, H., and A. Tice. 2011. “Children in Apartments: Implications for the Compact City.” Urban Policy and Research 29 (4): 415–434. doi:10.1080/08111146.2011.627834.

- Easthope, H., and S. Judd. 2010. Living Well in Greater Density: Shelter NSW.

- Enns, C. 2010. Child and Youth Friendly Housing & Neighbourhood Design. Abbotsford: City of Abbotsford.

- Ergler, C., K. Smith, C. Kotsanas, and C. Hutchinson. 2015. “What Makes a Good City in Pre-schoolers’ Eyes? Findings from Participatory Planning Projects in Australia and New Zealand.” Journal of Urban Design 20 (4): 461–478. doi:10.1080/13574809.2015.1045842.

- Ergler, C., R. Kearns, and K. Witten. 2013. “Seasonal and Locational Variations in Children’s Play: Implications for Wellbeing.” Social Science & Medicine 91 (91): 178–185. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.034.

- Europan Europe. 2021. “1000 Housing through a Collaborative Process Projet-process Video - E10 Wien (At) Garten>hof.” https://www.europan-europe.eu/en/think-tank/1000-housing-through-a-collaborative-process

- Fincher, R. 2007. “Is High-rise Housing Innovative? Developers’ Contradictory Narratives of High-rise Housing in Melbourne.” Urban Studies 44 (3): 631–649. doi:10.1080/00420980601131894.

- Foster, S., P. Hooper, A. Kleeman, E. Martino, and B. Giles-Corti. 2020. “The High Life: A Policy Audit of Apartment Design Guidelines and Their Potential to Promote Residents’ Health and Wellbeing.” Cities 96: 102420. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.102420.

- Government of South Australia. 2016. “Design Guidelines for Sustainable Housing & Liveable Neighbourhoods.” Retrieved from Adelaide: https://renewalsa.sa.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/2.4-environmental-sustainability.pdf

- Gustavsson, E., and I. Elander. 2016. “Sustainability Potential of a Redevelopment Initiative in Swedish Public Housing: The Ambiguous Role of Residents’ Participation and Place Identity.” Progress in Planning 103: 1–25. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2014.10.003.

- Heenan, R. 2017. Healthy Higher Density Living for Kids- the Effects of High Density Housing on Children’s Health and Development: A Literature Review to Inform Policy Development in Western Sydney. Parramatta: NSW Goverment: City of Parramatta.

- Istre, G. R., M. A. McCoy, M. Stowe, K. Davies, D. Zane, R. Anderson, and R. Wiebe. 2003. “Childhood Injuries Due to Falls from Apartment Balconies and Windows.” Injury Prevention 9 (4): 349–352. doi:10.1136/ip.9.4.349.

- Jang, J.-H., and M.-H. Kim. 2007. “A Design Suggestion for Flexible Livingroom Cabinets at Apartment.” Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Korean Institute of Interior Design Conference.

- Julian, T. W., P. C. McKenry, and M. W. McKelvey. 1994. “Cultural Variations in Parenting: Perceptions of Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, and Asian-American Parents.” Family Relations 43 (1): 30–37. doi:10.2307/585139.

- Kalantari, S., and M. Shepley. 2020. “Psychological and Social Impacts of High-rise Buildings: A Review of the Post-occupancy Evaluation Literature.” Housing Studies 1–30. doi:10.1080/02673037.2020.1752630.

- Karsten, L. 2009. “From a Top-down to a Bottom-up Urban Discourse: (Re) Constructing the City in a Family-inclusive Way.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 24 (3): 317–329. doi:10.1007/s10901-009-9145-1.

- Karsten, L. 2015. “Middle-class Households with Children on Vertical Family Living in Hong Kong.” Habitat International 47: 241–247. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.01.023.

- Kerr, S.-M., C. Gibson, and N. Klocker. 2018. “Parenting and Neighbouring in the Consolidating City: The Emotional Geographies of Sound in Apartments.” Emotion, Space and Society 26: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2017.11.002.

- Kerr, S.-M., N. Klocker, and C. Gibson. 2020. “From Backyards to Balconies: Cultural Norms and Parents’ Experiences of Home in Higher-density Housing.” Housing Studies 1–23.

- Krysiak, N. 2019. Designing Child-friendly High Density Neighbourhoods: Transforming Our Cities for the Health, Wellbeing and Happiness of Children. Sydney, Australia: Cities for Play.

- Lee, J.-H., and T.-C. Li. 2011. “Supporting User Participation Design Using a Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process Approach.” Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 24 (5): 850–865. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2011.01.008.

- Lilius, J. 2014. „Is There Room for Families in the Inner City? Life-Stage Blenders Challenging Planning.“ Housing Studies 29 (6): 843–861.

- Luck, R. 2018. “What Is It that Makes Participation in Design Participatory Design?” Design Studies 59: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2018.10.002.

- Martel, A., C. Whitzman, R. Fincher, P. Lawther, I. Woodcock, and D. Tucker. 2013. “Getting to Yes: Overcoming Barriers to Affordable Family Friendly Housing in Inner Melbourne.” Paper presented at the Sixth state of Australian Cities Conference (SOAC), Sydney.

- Mayor of London. 2012. “Shaping Neighbourhoods: Play and Informal Recreation. Supplementary Planning Guidance: 2012 (9781847815187).” Retrieved from London: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/osd31_shaping_neighbourhoods_play_and_informal_recreation_spg_high_res_7_0.pdf

- Mayor of London. 2019. “Making London Child-Friendly, Designing Places and Streets for Children and Young People.” Retrieved from London: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/ggbd_making_london_child-friendly.pdf

- Moghimi, V., M. B. M. Jusan, P. Izadpanahi, and J. Mahdinejad. 2017. “Incorporating User Values into Housing Design through Indirect User Participation Using MEC-QFD Model.” Journal of Building Engineering 9: 76–83. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2016.11.012.

- Mulholland, H. 2003. Perceptions of Privacy & Density in Housing. Design for Homes Popular Housing Research. London: Popular Housing Group.

- Nethercote, M., and R. Horne. 2016. “Ordinary Vertical Urbanisms: City Apartments and the Everyday Geographies of High-rise Families.” Environment and Planning A 48 (8): 1581–1598. doi:10.1177/0308518X16645104.

- Nordstrom, M. 2010. “Children’s Views on Child-friendly Environments in Different Geographical, Cultural and Social Neighbourhoods.” Urban Studies 47 (3): 514–528. doi:10.1177/0042098009349771.

- NSW Department of Planning and Environment. 2015. “Apartment Design Guide.” http://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/Policy-and-Legislation/Housing/Apartment-Design-Guide

- Rahim, A. A., and F. Hassan. 2011. „Study on Space Configuration and Its Effect on Privacy Provision in Traditional Malay and Iranian Courtyard House, IIUMPress.“ International Islamic University Malaysia (2011): 115–119.

- Randolph, B., and R. Freestone. 2012. “Housing Differentiation and Renewal in Middle-ring Suburbs the Experience of Sydney, Australia.” Urban Studies 49 (12): 2557–2575. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26151019

- Raynor, K. 2018. “Social Representations of Children in Higher Density Housing: Enviable, Inevitable or Evil?” Housing Studies 33 (8): 1207–1226. doi:10.1080/02673037.2018.1424807.

- Reid, S., K. Lloyd, and W. O’Brien. 2017. “Women’s Perspectives on Liveability in Vertical Communities: A Feminist Materialist Approach.” Australian Planner 54 (1): 16–23. doi:10.1080/07293682.2017.1297315.

- Robertson, T., and J. Simonsen. 2012. „Participatory Design.“ In Routledge international handbook of participatory design, edited by Jesper Simonsen and Toni Robertson. New York: Routledge.

- Saleh, A. 2006. Participatory Design, Theory and Techniques (Evaluation of Al-Maageen Housing in Nablus). In: MSc. Palestine: An-Najah National University.

- Scanion, E. 1998. „Low-income homeownership policy as a community development strategy.“ Journal of Community Practice 5 (1–2): 137–154.

- Shabani, M., M. Tahir, H. Arjmandi, N. Abdullah, and I. Usman. 2010. “Achieving Privacy in the Iranian Contemporary Compact Apartment through Flexible Design.” Selected Topics in Power Systems and Remote Sensing 285–296.

- Smith, K., and C. Kotsanas. 2014. “Honouring Young Children’s Voices to Enhance Inclusive Communities.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 7 (2): 187–211.

- Spinuzzi, C. 2005. “The Methodology of Participatory Design.” Technical Communication 52 (2): 163–174.

- Szafraniec, J., and B. Finney. 2017. “The Changing Face of Apartment Living.” https://www.sgsep.com.au/publications/insights/the-changing-face-of-apartment-living

- Tavakoli, A. 2017. Supporting Friendlier, More Neighbourly Multi-unit Buildings in Vancouver. Vancouver, Canada: City of Vancouver.

- Warner, E., and F. Andrews. 2019. ““Surface Acquaintances”: Parents’ Experiences of Social Connectedness and Social Capital in Australian High-rise Developments.” Health & Place 58: 102165. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102165.

- Whitzman, C. 2010. “Can Tall Buildings Be Child-friendly? The Vertical Living Kids Research Project.” CTBUH Journal 2010: 18–23.

- Whitzman, C., and D. Mizrachi. 2009a. Vertical Living Kids: Creating Supportive High Rise Environments for Children in Melbourne, Australia. Melbourne: University of Melbourne.

- Whitzman, C., and D. Mizrachi. 2009b. “Vertical Living Kids: Creating Supportive High Rise Environments for Children in Melbourne, Australia.” A report for the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. Retrieved from Melbourne:

- Whitzman, C., and D. Mizrachi. 2012. “Creating Child-friendly High-rise Environments: Beyond Wastelands and Glasshouses.” Urban Policy & Research 30 (3): 233–249. doi:10.1080/08111146.2012.663729.

- Woolcock, G., B. Gleeson, and B. Randolph. 2010. “Urban Research and Child-friendly Cities: A New Australian Outline.” Children’s Geographies 8 (2): 177–192. doi:10.1080/14733281003691426.