ABSTRACT

This study explores urban forestry as a maintenance practice capable of enhancing more-than-human commons in the city. Focusing on the places associated with tree care, the methodology takes as a case study the Tokyo Metropolitan Parks, conducting quantitative and qualitative analysis through the means of immersive field work and questionnaires, to reveal how urban forestry practices materialize within the parks. Regarding the spatial relations between humans and/or non-humans with resources, different Urban Forestry Elements (UFE) have been found, as well as their collection in groups within the parks forming Urban Forestry Assemblages (UFA). The paper creates a comprehensive framework that reveals these places for urban forestry as important beacons for urban commoning.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Walking through a park in Tokyo one can encounter various modes of matter at different stages. A pile of leaves in the process of becoming compost, mysterious pavilions that shelter tree branches under corrugated steel roofs, logs scattered along the paths, sudden patches of overgrown grass secured by a thin rope, ultra-tall sheds housing a collection of ladders or small trolleys filled with brooms, buckets, dustpans and wooden chunks. This collection of seemingly unrelated things are the physical traces of urban forestry, the practice that centers on the maintenance of trees in metropolitan areas (Konijnendijk et al., Citation2006).

Urban forestry differs greatly from conventional forestry in that its goal is not to transform extracted wood into a commodity but to care for city trees. Precisely because it is not an industrial productive activity, its material outcomes are usually discarded as waste. Yet, being situated in an urban context, with a high population density, expands the possibilities of participation of diverse actors, as well as the use of resources resulted from tree management – not only logs, but also leaves, branches or fruits. The value that underlies urban forestry is not a marketable one, but that of the relationships it creates (Martín et al., Citation2020)

In spite of this possibility, places for urban forestry activities are often occult, being located on the margins, camouflaged behind a dense group of trees. This maintenance inaccessibility implies the assumption of the citizen as a spectator, who behaves passively in a ready-made park – one that only offers the typical imaginary of freshly mown grass and flowers in bloom. However, existing urban forestry traces show glimpses of the disorderly entanglements of tree care, a practice capable of enriching the connections between humans and non-human beings in the city, or in other words, to foster urban commoning (Derya& Büyüksaraç, Citation2020). The aim of this study is to establish a framework that can reveal these hidden places for urban forestry as important beacons for constructing more-than-human commons by investigating their relations within Tokyo Metropolitan Parks.

1.1. Theoretical background: caring for more-than-humans

Urban forestry can be understood as a practice of care, following recent studies that have reconfigured its understanding to include multi-species concerns (Metzger, Citation2018). Following this line of thought, care is a work of repair and maintenance that recognizes the agency of different actors (humans, living beings or things) (Puig de la Bellacasa, Citation2017). In spatial planning Jonathan Metzger engenders this sensitivity towards non-humans with the concewpt of “caring for place”, as “territorial attachments” that are “geographically proximate and related” (Metzger, Citation2014). This implies a change of focus to understand the complex relationships that constitute a place (Barad, Citation2003). Jane Bennett also includes “non-human bodies as members of a public” that participate in “conjoint action” and not as merely as passive context (Bennett, Citation2010). Following this vital materialist approach, Bennett defines “assemblages” as “ad hoc groupings of diverse elements” that possess emergent properties. Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing gives a similar definition of assemblages as “open-ended gatherings” that hold “latent commons”, forming various coalitions between humans and non-humans (Lowenhaupt Tsing, Citation2015).

Patrick Bresnihan reviews the theory of commons – with Elinor Ostrom pioneering the logic of scarcity (Ostrom, Citation1990)- to advance that “more-than-human commons means making an intellectual leap into contexts where social and material resources are already immediately and intimately shared between humans and non-humans” (Bresnihan, Citation2015).

From these approaches, urban forestry can be redefined as a practice capable of building more-than-human commons. By exposing the material relationships that extend between trees and humans in the city, the sites for urban forestry form an ecological whole, an assemblage.

1.2. Relevant literature on urban forestry

Following the notion of urban forestry as commons, the field of ecological economics has discussed the “urban green commons” based on their capacity to contribute to the resilience of cities in times of vulnerability and uncertainty. Indicating that, due to urbanization patterns and lack of management models, there is a “mismatch between cultural and ecological diversity”. The two tend to be seen as inversely proportional, yet many cities emerge in natural ecosystems with rich biodiversity (Colding & Barthel, Citation2013). Other studies record the importance of partnerships between public, private, and community sectors for successful urban forestry projects, reminding those social relationships are as crucial as the urban environment’s physicality (Jones, Citation2005).

In geography and sociology, these commoning practices are used as an analytical lens for looking at the peri-urban context. Attending to conservation efforts, they give agency to the displacement of plants across territorial boundaries to blur the control over land conservation in private property. Cooke and Lane recommend to “positioned humans and more-than-humans as collective subjects, as opposed to a more traditional resource management-oriented relationship” (Cooke & Lane, Citation2018).

In the Japanese context, research on community-based forest management by neighborhood associations is developing on the concept of iriai (commons) and the ecology of satoyama, however is been applied mostly in rural settings (Yamashita et al., Citation2009). An exception to this trend is the group of “matsutake crusaders” located in suburban or peri-urban areas. They involve neighbors and enthusiasts in association to recreate the conditions that allow matsutake, a type of mushroom, to grow in the forest. Despite focusing solely on production, the study concludes that as care for the entire ecosystem increased, so did the resources, activities and actors involved. Satsuka notes that “the new commons demonstrate that the revitalization of natural ecology is inseparable from social ecology” (Satsuka, Citation2014).

In the Japanese academia, most of the studies framed urban forestry as a productive activity based on quantitative data. For example, Satoshi and Takaguchi analyse the amount of annual bio-debris produced in Tokyo’s 23 wards from parks and streets. They indicate that excluding the amount that is diverted to landfills or incinerators, 81% of bio-debris is recycled, most commonly into woodchips and compost. They suggest reducing travelling distances by including processing facilities within the parks (Sugisaki & Takaguchi, Citation2007).

Other studies on Tokyo focus on biomass from tree pruning, indicating that CO2 emissions in sports facilities could be reduced by 50% (Kohama et al., Citation2010). There are cases where the energy used to heat the showers in the sports fields is generated by a biomass boiler using woodchips from the park’s trees (Onishi et al., Citation2016). The use of woodchips as a construction material in particleboard has also been examined to build panels in dry environments under light loads Kobayashi et al., Citation2001).

Although these studies present an indispensable research base, there is still a need to deepen the ability to connect natural resources and citizens in relation to design. A recent example is that of Cyntia Santos Malaguti, who in exploring the use of urban wood in São Paulo indicates the need for a systemic design approach to this wasted resource (Malaguti de Sousa, Citation2019). This article follows this line of thought, contributing to advance these notions by focusing on one of the world’s largest metropolises, Tokyo.

2. Urban forests in Tokyo

2.1. Current status of urban forestry practice in Japan

The historical evolution of the forestry industry in Japan, a forest archipelago where wood has been the building material par excellence, has been widely addressed by several scholars (Totman, Citation1989). From the role of forests as “commons” (iriai) managed collectively by rural communities; the formation of the timber industry during the Edo period to provide construction material cities; the exponential growth of this industry during the postwar decades, and the resultant environmental transformations (Iwai, Citation2002).

However, the concurrent growth of urban forests in Japanese cities although studied from an ecological point of view (Cheng et al., Citation1999), remains a gap in the existing literature as assemblages which harbor untapped potentials for weaving connections between natural resources and citizens (Hotta et al., Citation2015). As explained above, conventional forestry practice finds a different meaning when situated in the urban environment. Although urban green commons have been studied in other countries (Colding & Barthel, Citation2013), it is necessary to discover its intersection with the Japanese context.

Urban forestry, the maintenance of urban forests, is a practice that is bound up with the life cycle of trees, and for that reason it does not cease. It consists of repetitive actions in a dynamic and open-ended process that is in constant regeneration (Darlan Boris, Citation2012). The spatial and temporal rhythms of green management and its material flows are always variable. In fact, Tokyo’s humid subtropical climate favors tree growth and, together with the presence of seasonal typhoons that increases the number of fallen trees, makes urban forestry a year-round activity that produces large amounts of diverse natural resources.

Nevertheless, tones of byproducts resulted from this tree maintenance process are labeled as waste. While sometimes they found material afterlives, as in the case of the transformation of logs into woodchips or energy, they are usually discarded (Kohama et al., Citation2010). This highlights the subjectivity in what constitutes waste and how biodebris is perceived. (Ibañez, et al. Citation2019) This sorting practice is generally carried out by professionals within park facilities without the participation of local residents. What is decided to be kept as resource continues its cycle of transformation, and what is catalogued as disposable is removed from the park as “industrial waste”. (.)

A typical day’s work in urban forestry is linked to the flow of resources as they are sourced, extracted and transformed within the park. Workers often gather at the service center, pick up tools, walk or drive small carts, prune trees and accumulate the resulting material, which is then transferred to the biodebris yard for further processing into wood chips or disposed as waste. The invisibility of these activities is facilitated by the series of fences, signs to stay-out or not to trespass. They are only accessible to workers in the facility.

In Tokyo Metropolitan Parks urban forestry activity is mainly performed by hired professionals, and any left resource that could present a potential danger for the visitors is removed from the premises. The urban forestry workers navigate the park riding bicycle or a mini truck, wearing a wide trouser coveralls, a helmet, a pair of jika-tabi shoes, and a thick belt packed with pruning tools. A towel around the neck and a hanging katori-senko (incense to repel mosquitoes) are added to the outfit to bear the hot and humid Japanese summer.

Despite being recognized for their significant role in supporting the welfare of citizens as vital voids for decompressing densely populated neighborhoods (Jonas & Rahmann, Citation2014), parks have been dismissed as resourceful grounds that have the capacity to foster interspecies commons. Parks are ecological patches of forests on a city scale, constituting a meta-assemblage in the urban realm, capable of intertwining connections between resources, humans and living beings in the city.

2.2. Parks as urban forestry sites

In Edo – the old name for Tokyo during the feudal regime – entertainment in the ordinary life of most of the urban population was not related to green areas. Commoners lived in only 20% of the territory with a population density five times higher than in the current 23 wards. The urban forests were in the 65% of the land occupied by the wealthy elites and in the 15% of the religious property. When the imperial restoration ended the Tokugawa Shogunate, the domains of the feudal lords (daimyo), the residences of the wealthy warriors (samurai), and the grounds of the temples and shrines, went from private to state ownership (Fujita & Kumagai, Citation2004). Many of the urban forests resulting from this expropriation became accessible to commoners, by their transformation facilitated by the Tokyo Grand Council Parks of 1873.

In this way, the contemporary definition of parks as public spaces finds its roots in the Meiji era (1868–1912) following Western ideologies of civic culture. In their early stages they were conceived as places that served the purposes of the state, which sought to improve environmental, hygienic, ornamental and recreational conditions in crowded residential areas, as well as to portray a modernized society. When Tokyo was devastated by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, green spaces transcended their beautification status to become places of survival. In the following decade, more urban parks were created to act as effective firebreaks in crowded built-up areas.

In 1939, the Tokyo Green Space Planning Commission launched a proposal for a green belt for the capital to limit suburban expansion. This “green space” (ryokuchi) was also conceived as a fertile area with forests and farmland. During World War II, urban forests were used as emergency shelters that could provide essential resources such as food or timber. The parks became productive land for growing vegetables or rice, using tree logs for firewood. They also housed many barrack-style dwellings, and even today, urban forests still serve as shelter for the needy (Havens, Citation2011).

Post-war legal frameworks, such as the 1956 City Parks Law or the 1968 City Planning Law, ensured the creation of parks, establishing that only 2 percent of the total area could be devoted to facilities – 5 percent when these were cultural – and providing funds to transform sites formerly devoted to military defense, scientific research or industry into green spaces. The demand for housing construction was so pressing that the Japan Housing Corporation began building in the planned greenbelt area. However, groups of citizens concerned about the environmental impact demanded the protection of urban forests, raising awareness of their beneficial role. Between the 1970s and 1990s, the number of parks in Tokyo tripled, with different public-private coalitions helping to plant trees and new decrees such as “tree contracts” that reduced inheritance taxes for those who allowed the public to use their private green spaces (Havens, Citation2011).

Amendments to the 1992 City Planning Law and the 1993 Basic Environmental Law facilitated the inclusion of non-bureaucratic stakeholders in design planning, as well as civic participation (machizukuri). Academic critics, such as historian Kimura’s Shōzaburō, encouraged broadening the perspective of civic reconstruction beyond social and economic aspects, addressing community sustainability as “no longer human-centered but nature-centered”(Shōzaburō, Citation1990). However, the current management of the parks, including the activities of participation of the neighbors, still maintains an anthropocentric vision oblivious to the non-humans, this study argues that is possible to advance towards contemporary environmental concerns through the practice of urban forestry.

3. Methodology

Minding that the present study focuses on urban forestry within the park, and not general park management, the framework is established addressing only the relations around resources that derive from tree maintenance, based on the understanding of urban forestry as a practice of care capable of constructing more-than-human commons, that is, of mutualistic relationships between humans (workers, citizens) and/or non-humans (forest).

Park design has been extensively studied according to the spatial composition of its facilities and landscape features. In this case, spatial analysis following geometrical arrangement (such as symmetry from a particular axis) is relevant because it is catering to visitors’ sight. As posed in this article, Urban Forestry Elements’ presence follows ecological relations between resources and More-Than-Humans. One of this study’s objectives is to reveal that Urban Forestry Assemblage patterns comprise a hidden, latent layer within the urban parks.

Different case study-based methodologies, which can be found in numerous investigations on metropolitan parks, are combined to elaborate this research. A first methodological group uses publications and historical maps to trace the evolution of specific el elements (Nagano & Ariga, Citation2012) and supplemented with a field survey of the current situation (Zhang & Zhang, Citation2009). However, they differ in being focused on spatial composition studies (Hiraoka, Citation2009). The second methodological set establishes the user’s perspective through questionnaires, (Akamine et al., Citation2003) focusing on the spatial practices that are performed in the parks (Tomori et al., Citation2005). Some studies go further into the user profile through in-depth interviews (Shimpo et al., Citation2019), which in this report it did not apply since we focus on an extensive collection of cases.

This study uses quantitative and qualitative data to advance the understanding of the current state and the spatial consequences of urban forestry practice within Tokyo parks. Urban forestry practice occurs in large urban forests within the dense urban fabric of Tokyo. Therefore, those parks within the 23 special wards and directly managed by the Metropolitan Government are selected as case study. As well as some representative cases of major urban forests managed by the Central Government, the Imperial House or Meiji Jingu. ()

First, data on the urban forest that constitutes the parks is obtained by collecting information from different sources in online publications and maps from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Second, immersive fieldwork is done by conducting on-site surveys to observe and document their spatial characteristics. Last, a questionnaire is sent to the park management staff asking about sorting practices, places for tree maintenance, outsourced activities and collaborations in order to better understand the urban forestry work.

Additional up-to-date data from contemporary sources such as satellite and street view images have been used to complement the one published by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Aerial and satellite images from several decades have been employed to confirm the park’s evolution through time. All the cases were also visited virtually with Google Street View, which allows walking along the main paths as an interactive panorama from a person’s perspective. For contrasting and expanding these data sets, the authors visited every park from July to September 2021, documenting exhaustively with photographs and sketches. This urban forestry’s systematic documentation is original, composing a reliable, consistent, and comprehensive material for the study.

As previously introduced, conventional urban forestry is centered around the maintenance of trees by professional workers, as a result, this activity produces a great amount of forestry resources such as leaves, branches or logs that are normally discarded as waste. Therefore, this study introduces the term Urban Forestry Element (UFE) as those places related to such resources – either actively when they are being used directly, or in a latent way, when they could be used but remain still untapped – being an Urban Forestry Assemblage (UFA) the collection of urban forestry elements within the park.

3.1. Definition of urban forestry elements

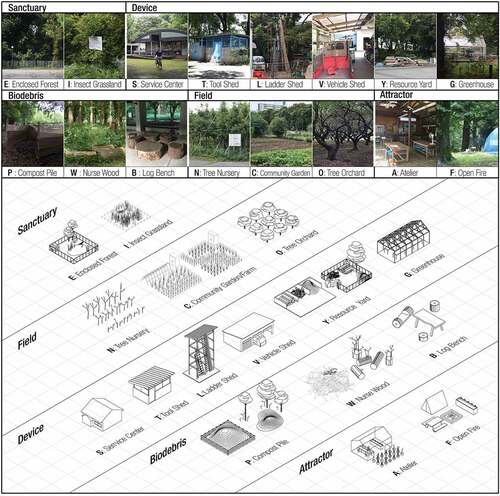

All the parks indicated in the case study list were visited and urban forestry elements of several types were distinguished across all the park surface. () Sanctuary are enclosed patches of forest (E) or fenced grasslands prepared for different insects to thrive (I), where forestry resources fall naturally onto the ground, being consumed, decomposed or nurtured by different beings that transform them into rich soil, allowing the forest ecosystem to self-maintain. Field are patches of land that utilize the power of the soil to grow and reproduce trees or plants that could benefit from the resources generated in the park. These are open-air tree nurseries (N), where seeds and saplings are nurtured; tree orchards (O), community gardens and farming grounds (C) where daily productive activities occur.

Device are constructions of different sorts that allow the workers to undertake the necessary tasks for the maintenance of trees. These are the service center (S) that behaves as the park staff headquarters; the tool shed (T) and ladders shed (L) that house various instruments necessary for dealing with trees; vehicle shed (V) where different means of transport such as carts, cars, trucks and cranes are parked; greenhouse (G) where the workers reproduce tree saplings; and the resource yard (Y) where different urban forestry by-products are sorted and stored before being sent away as waste.

Biodebris are leftovers of tree maintenance that find diverse afterlives inside the park. These are piles of leaves gathered for making compost that fertilize the same park grounds (P); piles of wood that nurture the emergence of certain living beings (W); and log sections reshaped as park benches (B). Attractor are constructions prepared for citizen enjoyment that could potentially utilize forestry resources in the park. These are the places for open fire (F) where wood from tree pruning could be utilized as fuel; and ateliers (A) for conducting workshops and educational activities where urban forestry resources could be transformed.

3.2. Analysis example

In order to be able to compare all the case studies, the UFE discovered during the site visits are noted for all the parks, complementing this information with temporality and urban forest composition. Temporality, in which the year of establishment is indicated, and the previous stages to becoming a park, these being Agriculture (Ag), Disaster Prevention (Di), Industry (Id), Housing (Hs), Infrastructure (If), Imperial (Im), Landfill (Lf),

Military (Mi), Forest (Fo), Old Settlements (Os), Daimyo Residence (Rd), Religious (Rg), Research (Rs), Sports (Spt), Storage (Str). The date of establishment is relevant to know the historical context of each park as well as the different program changes because, as commented in the introduction, it is an urban typology that was introduced with the Meiji modernization experiencing different stages in time.

Urban Forest Composition, in which the shape, area of the park, number of trees, density of trees per hectare are noted; bodies of water being: Beach(Bc), Fountain (Ft), JabuJabu (Jb), Moat (Mt), Ocean (Oc), Pond (Pd), Large Pond (PdL), River (Rv), Spring (sp), Stream (St) Sewage (Sw) Tidal Flat (Tf); and type of ground: Artificial topography (Af), Natural topography (Nt), Landfill (Lf), Flatland (Fl). As for the shape, there are three types, compact (Co) when they do not have a predominant direction, elongated (El) when they have a predominant direction and fragmented (Fr) when it is divided by significant boundaries.

Once the previous data is collected for all the cases, a drawing is made of each park mapping its perimeter, the forested areas, the paths and the water bodies, as well as the location of the urban forestry elements discovered during the visits. In the case of Rinshinomori, no. 36, () the table shows that it was established as a park in 1989 after having gone through the stages of agriculture (Ag), center for forestry research (Rs), housing after WWII (Hs) and again research institution (Rs). It is characterized as an elongated park with 12 ha, more than 6100 trees and a canopy density of 505 tree/ha, which means one tree every 4.5 m. It has water bodies of jabu-jabu pond (Jb) – Japanese water playground–, water spring (Sp) connected to a pond (Pd) and a rich natural topography (Nt). There are many urban forestry elements throughout the park, with a distinguishable core of Device elements composed by service center (S), tool shed (T), ladder shed (L) and vehicle shed (V), that has an Atelier (A) attached to it. An additional aggrupation is formed by another tool shed (T), resource yard (Y) and Open Fire (F). Spread throughout the surface and attached to the main paths is possible to find other elements such as nursery (N), insect grassland (I), tree orchard (O), community gardens (C) and nurse wood (W), while piles of compost (P) are located inside the forested areas.

4. Discussion

We can find studies developed in several parks under perspectives that are specific to each case. A study on fire resistance by tree species distribution in Hibiya park (no. 4) similarly maps a hidden, latent layer. (Hukusima & Kadoya, Citation1989) A paper on the evolution of Meiji Jingu Gaien (no. 7), centered around the stadium and how the rest of the facilities orbited depending on visual and programmatic composition (Kon & Hashimoto, Citation2018). Or an investigation of social issues such as the occupation of Toyama Park (No. 18) by homeless people in the late 1990s (Sugitomo & Goto, Citation1999). Connections can be found with those previous works. The research presented also unfolds the hitherto unexplored latent perspective of urban forestry, locates those related programs and spatial elements, and records those practices where humans and non-human agents are involved. However, there is a need for a methodology that registers a large number of case studies to establish the basis of urban forestry at the city scale. Only then itwill be possible to extract patterns and lessons to redefine this practice through the found similarities and variations.

All the information from the 39 cases is compiled into a comprehensive table. (). The first analysis is conducted considering the totality of the parks, to understand what are the general characteristics as a whole. Regarding temporality, from the 1920s to the 1990s there was a gradual and constant creation of parks, with the 1960s being the decade when most of them were opened. It has been proven that their activities have changed several times in their location, demonstrating their adaptability, adjusting to social perception over time. Two thirds of the parks have more than one previous stage, and it is very common to have changed their use between 2 and 3 times, but it can be as many as 6 times. The most repeated use is that of residence, samurai and imperial grounds, followed by industrial and storage facilities.

Table 1. Urban forestry assemblages.

Regarding composition, the most common area is between 10 and 20 ha, with a great diversity of sizes distributed homogenously between the minimum range of 1 ha and the maximum of 96 ha. As for the shape, there is a similar number of cases for each type (compact, fragmented and elongated). These factors indicate a great diversity in the morphological character of Tokyo Metropolitan Parks. Considering the number of trees, the inclination is to have between 2000 and 10,000 trees, the minimum being 1000 and the maximum 36,000. Trees/ha is important parameter to know the density of the urban forest, from a minimum of 50 to 800 trees/ha. The tendency being 200 to 300 trees/ha, assuming one tree every 5.5 m. Most of the park incorporate an artificial water body, being the most common the pond. More than half have a relation with a natural body of water like streams, springs or rivers. Regarding the ground most of them have remarkable topography, both naturally existing and artificially created. Half of them have a human intervened ground, either to create the landscape topography or to make the ground by the means of landfill.

4.1. Urban forestry elements (UFE)

Reading the table considering all the parks reveals the tendencies of each UFE. Device are the most common elements, being present in all the parks. Service center, tool shed, vehicle shed and resource yard appear in the vast majority of cases, constituting the core elements of typical tree maintenance. More than half of them have specialized tall sheds for stairs and long tools. Biodebris appears in 25 cases, more than half, the most common being compost piles which are only missing in 4 cases, followed by nurse wood which constitutes just under half of the cases. Log benches are the least common with only 9 cases. Field are the second most common elements, presenting 30 cases. Most of them are nurseries, followed by community gardens and orchards, often appearing only one type of field per park. Attractor are the scarcest elements, appearing in 13 cases. Only in three cases more than one Attractor is present. They always appear together with Biodebris and often when there is Field. The least common of all the elements is the Atelier with only 7 cases. Sanctuary appears in 20 cases, with the enclosed forest being the predominant case – there is only one without it – and usually accompanied by insect grassland.

Also, when considering the combination of all UFE, distinct inclinations can be observed. It is noteworthy that once an element of Biodebris is found, it usually appears with other types, having a variety of combinations. It is also remarkable that while Biodebris and Attractor appear whenever there are Fields, Fields can appear independently. Likewise, although the Sanctuary may appear alone, in the vast majority of cases they do so in combination with the other three types of elements. The Atelier only acts together with the Sanctuary, showing a relationship in parks that have an especially natural character.

When looking at Temporality and Urban Forest Composition, different park characteristics are revealed together with the UFE. Attending to the year of establishment, all the parks established in the 1960s and 1970s have the elements Biodebris and Field, with open fire only appearing from the 1960s onwards. Regarding previous stages, it is found that Atelier only appears when there is an institution that is carrying or has carried out research. All the Sanctuary elements rarely appear in fragmented shape parks. This may indicate that the enclosed forest where different species thrive, although not accessible, is usually adjacent to the rest of the park.

When Field element exist, parks tend to be larger than 10 ha. Similarly, regarding Biodebris, two thirds of the parks that present it are bigger than 20 ha. The number of trees is also a determining factor for Biodebris, exceeding 5,000 trees, with half of the parks presenting above 10,000 trees, being the tendency in terms of density 200 trees/ha. Finally, running bodies of water and natural topography tend to appear with Field element.

4.2. Urban forestry assemblages (UFA)

The UFE presented in the previous section enable different degrees of resource accessibility. Firstly, those corresponding to Device, are only used by workers, being very difficult to access by citizens, as they require the necessary knowledge to operate with tools and perform the most professional tasks. Then, those corresponding to Biodebris imply an active use of resources that already exist in the parks, and although are generated by the workers, they present latent commons for diverse members to participate. Field and Attractor are the ones that most easily connect citizens and resources, such as those that are operated by workers but are open access (Nursery, Orchard) and those that are prepared for citizens but do not yet use the resources produced in the park (Community Garden, Open Fire, Atelier). Finally, Sanctuary is exclusively for non-human use, since in this element specifically restricts human access. By analyzing the collection of UFE in each park, namely the Urban Forestry Assemblage, regarding this accessibility aspect different characters can be commented on distinguishing five types of assemblages (.):

Professional Care are those assemblages where workers center exclusively in tree and gardening care, e.g. Hibiya Park. It is the most standard group, presenting a collection of elements only of the Device type. Although it is essential for the health of urban trees, it does not present specific elements that deal with resources, thus reducing the possibility of collaboration between diverse members. All of them were created before 1950, and in the previous stages were residences of wealthy elites. Their shape is mainly compact and their size is small in relation to the rest of the parks, having less than 10 hectares, artificial topography, no more than 5000 trees and presenting different canopy density.

Self-maintained Patch are those assemblages where urban forestry is carried out by workers, but also present parts where the forest regenerates without human intervention, e.g. Odaiba Marine Park. This group is similar to the previous one, but although the resources are discarded as waste in most of the park, the presence of the Sanctuary element indicates that resources are used by non-humans in the areas of restricted access. For example, if a tree falls, it naturally decomposes to provide nutrients for the creatures that inhabit the urban forest. Its characteristics are also compact, less than 10 hectares and no more than 5000 trees.

Disconnected Cooperation are those assemblages that, even though contain elements that could trigger citizen participation through resource utilization, the forestry resources are disregarded as waste, e.g. Nakagawa Park. Like the previous type, in this group only the combination of another element appears together with Device. In this case Field elements do not currently use resulting resources from urban forestry– they are lost as residues– but it could potentially be used, as for example organic matter as fertilizer. According to the establishment date, three subgroups can be observed: those opened in Meiji, which were previously religious grounds; those before the war, which were residences; and those after the 1980s, which were industrial sites prior to becoming apark. There is adiversity of shapes and sizes, most commonly they tend to be small with less than 12 ha, but there are two very large parks of 25 and 50 ha. They do not have many trees, less than 5000, but they present in almost all the cases running water bodies having different topographical features.

Resourceful Interaction are those assemblages with prolific urban forestry practices where resources are being transformed and could be further utilized through citizen participation, e.g. Kiba Park. In this group appears for the first time the element Biodebris, implying the active use of resources in the park and presenting the latency of diversifying the members involved in the maintenance of trees together with the Field and Attractor. This assemblage presents a critical threshold, tending to be over 10 ha, have more than 5000 trees, and a density of more than 200 trees/ha. Their establishment date is mainly post-war. Other characteristics are a tendency to be fragmented, to have running water and a flat ground.

Diverse Participation are those assemblages that foster care interdependences between workers, trees, citizens and resources through all the combination of every UFE type, presenting the greatest potential of urban forestry for more-than-human commons, e.g. Mizumoto Park. This group contains all types of elements, and therefore the maximum accessibility. It is characterized by a great concentration of parks created in the post-war period. Those that are prior to the 1940s were residences that have varied their use through several stages. It is the group where the research phase prior to being establish as a park is more common, being the only group where the Attractor Atelier appears. As for shape, there are elongated and compact, being few fragmented. They are all very large, tending to have more than 30 ha and more than 10,000 trees. The most common density is between 200 and 300 trees/ha. However, in this case the water and the ground are not determining, since they present a diversity of types.

5. Park staff questionnaire

A questionnaire was sent to all the 39 case studies to learn exactly how and to what extent each of these parks was dealing with their resources. The staff who answered the survey are municipal employees responsible for managing the day-to-day operations of the park, working in the permanent offices within its premises. Twenty-four parks responded, and the remaining ones either did not reply or refuse to respond, indicating that urban forestry activity is not evident to visitors or is even hidden. The questions sent consisted of three themes: 1) how the park behave regarding the management of urban forestry resources, 2) who performs the urban forestry work, and 3) what kind of activities are open to outsiders. (Table 2)

In all the case studies, organic matter resulting from tree maintenance work is thrown away as “industrial waste” through the disposal of bio-debris in off-site dumping facilities. But it is also noted that almost all of them use at least one type of resource. The most common is woodchips, with more than half of the parks spreading them on the ground. For the rest of the resources, the number of cases that present utilization is similar. Leaves for making compost and logs for crafting urban furniture appears in 8 of the parks, branches are used mainly for enhancing the habitat of living beings in 7 parks, while fruits and seeds are collected in 6 of the cases.

The number of regular park workers is usually between 5 and 15, except in very large parks that have more personnel. In 16 cases, they externalized urban forestry duties to other companies. The most commonly outsourced works are pruning and cleaning the leftovers, with 13 and 14 cases respectively. Other tasks such as mowing or repairing the equipment needed for tree maintenance are carried out in collaboration with subcontracted employees in 11 and 10 cases. This shows that there is a system already in operation for external agents, professionals belonging to companies, to deal with resources in a public-private partnership model. As for the collaboration of non-professional entities, comprised of individual citizens such as neighborhood associations, schools or NGOs, there is participation in 14 of the cases. These are mainly groups of volunteers who carry out cleaning activities in 5 cases, being the most frequent involvement community gardening in 10 cases, or educational programs to learn about the different plant and animal species that inhabit the park in 11 cases. It is also observed, that the absence of outsourced work results also in a lack of citizen participation.

6. Conclusion

After conducting field visits in 39 Tokyo Metropolitan Parks, specific places related to urban forestry resources were found, being named in this study as Urban Forestry Elements (UFE) and catalogued as: Device, Biodebris, Field, Attractor and Sanctuary. When comparing the relevant characteristics of all the parks, they showed a wide diversity of sizes, shapes and urban forest compositions. In terms of temporality, these facilities display a capacity to adapt by absorbing new uses or by being reconfigured throughout history. This suggests that the park typology could continue to evolve in the future, adapting to a value-based approach that includes the perspective of commons through a novel understanding of the interaction with non-humans in the city.

By observing the set of cases as a whole, different tendencies were revealed according to the existence and combinations of UFE. Device elements were present in all the case studies, constituting the fundamental component in tree maintenance. Although Sanctuary and Field can appear independently with Device, it is noteworthy that in the vast majority UFE do so in combination with other elements. In this sense, Biodebris has a critical role, since it displays a chain of correlations, always appearing together with Field, as well as Attractor elements that only exist when Biodebris is present. At the same time, Atelier only appears together with Sanctuary, showing a direct link to parks that have protected areas and where research has been in place, either in the present or in previous stages. On the other hand, Field elements tend to emerge in parks larger than 10 ha with flowing water bodies.

As for the collection of UFE in each park, denominated Urban Forestry Assemblage (UFA), they were examined considering the different degrees of resource accessibility allowed by each UFE, revealing five UFA characters, which organized from restrictive to inclusive accessibility are: Professional Care, Self-maintained Patch, Disconnected Cooperation, Resourceful Interaction, and Diverse Participation. By crossing these patterns with other morphological characteristics of the parks, critical thresholds were discovered in the ones that present broader accessibility. In terms of size, the parks with the greatest diversity have more than 10 Ha of surface area, as far as urban forest composition is concerned, more than 5000 trees and a canopy density of more than 200 trees per hectare ensures the appearance of certain UFE which help diversify the participants in urban forestry.

After carrying out a questionnaire with the personnel of the park, it has been verified that leftovers from tree maintenance are always dismissed as industrial waste. But also, that almost all the parks are already utilizing some forestry resources. Moreover, there are existing collaborations to undertake urban forestry work by outsource companies, but this assistance is exclusively professional and without social links. Although currently disconnected from the direct care of the trees, there is citizen participation within the parks, and therefore, there is the potential to connect it through the use of the various resources generated by this activity.

The degree of accessibility within city parklands means that diverse users could participate more actively in their care, helping to strengthen mutual relations with the non-human territory. The organic matter that is now perceived as waste is precisely the one that connects several members, however, this kind of relation remains untapped. All the above tendencies reveal Tokyo Metropolitan Parks as Urban Forestry Assemblages that allow the conjoint action in the use of urban forestry resources, holding the latency of constructing more-than-human commons in the city.

This study can also assist other significant cities in East Asia, where parks should be designed as UFA to encourage interspecies interactions and citizen community-building activities and events. Tokyo’s case has demonstrated that it is possible to adapt the mindset towards urban forestry in parks, which have changed their social perception over time. Naturally, the existence of a favorable climate for tree growth is desirable. Physical parameters such as park area, number of trees, and canopy density were discovered as factors that facilitate Urban Forestry’s appearance. However, the first step is to recognize the capacity of urban forestry resources to connect diverse members.

Furthermore, to breach the gap between the maintenance staff and the citizens, it is needed to fulfill the sequence of resource sourcing, extraction, and transformation within the park premises, linking different isolated Urban forestry elements. Special attention should also be given to areas where access to humans is restricted, creating sanctuaries where the natural ecosystem metabolizes forest resources. Another possibility is to reinforce existing local woodworking networks by imagining how urban parks can become a gathering place to gather timber and recirculate it for neighbors to utilize.

Through the suggestions and opportunities provided, relevant stakeholders can design following a relational, entangled understanding of urban forestry resources’ possibilities. For this reason, not only the field of architecture or urban planning would benefit from this analysis, but also landscape, arboriculture sciences, as well as policymakers and citizens’ organizations. Suppose the urban forestry mindset proposed in this research was incorporated into the design of parks and applied to case studies in other geographies. In that case, these could be reconfigured, thinking from the perspective of care and considering how diverse agents’ inclusive participation can regenerate them.

This research challenges the city to weave non-capitalist relationships with non-humans, which could be applied to other productive networks, where the circular economy is central to their practice. In Tokyo’s case, we can continue to explore the networks that exist around wood craftsmanship. Deepening into the current issue of akiyas -abandoned houses-, reformulating their material value of salvaged timber from those structures as a latent urban forest. Urban forestry assemblages trigger discussions about the role of urban matter in a future climate crisis scenario. This issue can be further traversed with the consequences it would have on the net of CO2 emissions by exploring other materials in their trans-scalar character, from the construction site’s behavioral properties to their vast network of territorial consequences.

Dislcosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the MEXT Scholarship for supporting this research, to the Tsukamoto Laboratory members at the Tokyo Institute of Technology for their continuous help, and to the Tokyo Metropolitan Parks Association for their cooperation in answering the questionnaire. Also, we would like to extend our gratitude to the reviewers for their accurate feedback, which we believe has substantially improved this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akamine, R., K. Funahashi, T. Suzuki, M. Kita, and B. Li. 2003. “A Study on Use of Open Spaces at Osaka Amenity Park (Oap) and in Its Neighborhood.” Journal of Architecture and Planning 68 (566): 71–79. doi:10.3130/aija.68.71_2.

- Barad, K. 2003. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.”Signs 28 (3): 801–831. doi:10.1086/345321.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Bresnihan, P. 2015. “The More-than-human Commons: From Commons to Commoning.” In Space, Power and the Commons: The Struggle for Alternative Futures, edited by S. Kirwan, L. Dawney, and J. Brigstocke, 93–112. New York: Routledge.

- Cheng, S., J. R. McBride, and K. Fukunari. 1999. “The Urban Forest of Tokyo.” Arboricultural Journal 23 (4): 379–392. doi:10.1080/03071375.1999.9747253.

- Colding, J., and S. Barthel. 2013. “The Potential of ‘Urban Green Commons’ in the Resilience Building of Cities.” Ecological Economics 86: 156–166. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.10.016.

- Cooke, B., and R. Lane. 2018. “Plant–Human Commoning: Navigating Enclosure, Neoliberal Conservation, and Plant Mobility in Exurban Landscapes.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (6): 1715–1731. doi:10.1080/24694452.2018.1453776.

- Darlan Boris, S. 2012. “Urban Forest and Landscape Infrastructure: Towards a Landscape Architecture of Open-endedness.” Journal of Landscape Architecture 7 (2): 54–59. doi:10.1080/18626033.2012.746089.

- Derya, Ö., and G. B. Büyüksaraç. 2020. Commoning the City. Empirical Perspectives on Urban Ecology, Economics and Ethics. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Fujita, N., and Y. Kumagai. 2004. “Landscape Change and Uneven Distribution of Urban Forest in Center of Tokyo.” Landscape Research Journal 67 (5): 577–580. doi:10.5632/jila.67.577.

- Havens, T. R. H. 2011. Parkscapes: Green Spaces in Modern Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Hiraoka, N. “Design Principle of the Garden of Mont Des Arts Seen from City Axis and Vista.” Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan 44-3: 2009. 895–900. doi:10.11361/journalcpij.44.3.895 in Japanese.

- Hotta, K., H. Ishii, and K. Kuroda. 2015. “Urban Forestry: Towards the Creation of Diverse Urban Green Space.” Journal of the Japanese Society of Revegetation Technology 40 (3): 505–507. doi:10.7211/jjsrt.40.505.

- Hukusima, T., and K. Kadoya. 1989. “On the Study of Fire Resistance by Tree Species and Their Distribution in Urban Parks.” Japanese Journal of Forest Environment 31(2): 35–45. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110008146573/en/

- Ibañez, D., J. Hutton, and K. Moe. 2019. Wood Urbanism: From the Molecular to the Territorial. Barcelona: Actar Publishers.

- Iwai, Y. 2002. Forestry and the Forest Industry in Japan. ed. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Jonas, M., and H. Rahmann. 2014. Tokyo Void: Possibilities in Absence. Berlin: Jovis.

- Jones, N. 2005. “The Role of Partnerships in Urban Forestry.” In Urban Forests and Trees, edited by C. C. Konijnendijk, K. Nilsson, T. B. Randrup, and J. Schipperijn , 187–205. Berlin: Springer.

- Kobayashi, J., T. Tochigi, C. Tadokoro, amd R. Onoda. 2001. “Production of Particleboard Utilizing Spiral Chips Processed from Urban Woody Residue.” Journal of Agricultural Science Tokyo, University of Agriculture 46 (3): 191–195.

- Kohama, S., M. Kawasaki, and H. Takaguchi. “Study on the Introduction of Wooden Biomass Energy Using Prune Branches in Tokyo 23 Wards.” Conference on Air Conditioning and Sanitary Engineering in Japan, Yamaguchi (2010): 987–990. (In Japanese).

- Kon, K., and T. Hashimoto. 2018. “The Study on the Spatial Placement of the Meiji Jingu Gaien Stadium.” Journal of Architecture and Planning 83 (746): 795–803. doi:10.3130/aija.83.795.

- Konijnendijk, C. C., R. M. Richard, A. Kennedy, and T. B. Randrup. 2006. “Defining Urban Forestry – A Comparative Perspective of North America and Europe.” Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 4 (3–4): 93–103. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2005.11.003.

- Lowenhaupt Tsing, A. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Malaguti de Sousa, C. 2019. “Waste Valuing from Wood Management through Design: Ideas from the Case of São Paulo.” International Journal of Architecture, Art and Design 6: 228–239.

- Metzger, J. 2014. “Spatial Planning And/as Caring for More-than-human Place.” Environment and Planning 46: 1001–1011. doi:10.1068/a140086c.

- Metzger, J. 2018. “Taking Care to Stay with the Trouble.” Architectural Theory Review 22 (1): 140–147. doi:10.1080/13264826.2018.1417663.

- Nagano, S., and T. Ariga. 2012. “A Study on the Influence on Park System by Converting Former Military Lands into Parks and Green Lands.” Journal of Architecture and Planning 77 (675): 1077–1086. in Japanese. doi10.3130/aija.77.1077.

- Onishi, T., M. Hayashi, and T. Terada 2016. “Wood Energy Utilization in a Large Urban Park: Case Study in Oi Central Seaside Park, Tokyo, Japan.” The 15th International Lanscape Architectural Symposium of Japan, China, and Korea. Tokyo, Japan, October 30.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge [England]; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Martín Sánchez, D., Y. Tsukamoto, and N. Gómez Lobo. 2020. “Pavilions Revealing the Possibility of Urban Forestry as Commons.” Architectural Institute of Japan, Journal of Technology and Design 26 (64): 1230–1235.

- Satsuka, S. 2014. “The Satoyama Movement: Envisioning Multispecies Commons in Postindustrial Japan.” Asian Environments: Connections across Borders, Land- Scapes, and Times 3: 87–94.

- Shimpo, N., A. Wesener, and W. McWilliam. 2019. “How Community Gardens May Contribute to Community Resilience following an Earthquake.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 38: 124–132. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2018.12.002.

- Shōzaburō, K. 1990. Machizukuri No Kokoro: Miryoku Aru Chiiki Bunka No Sōzō. ed. Tokyo: Gyōsei.

- Sugisaki, S., and H. Takaguchi. “A Study on the Amount Roadside Trees and Parks and Their Effective Utilization in the 23 Wards of Tokyo.” Architectural Institute of Japan, Kanto Branch Research Report Collection. 4045 (2007): 581–584 (In Japanese).

- Sugitomo, G., and H. Goto. 1999. “A Study on Park Occupation by Homeless and the Mechanisms in Toyama Park Tokyo.” Journal of Architecture and Planning 64 (517): 215–222. doi:10.3130/aija.64.215_1.

- Tomori, A., H. Suzuki, and M. Urayama 2005. “A Comparison Study on Users’ Characteristics and Recreational Activities between A Park with Reservoir and Another without Reservoir: Characteristics of Recreational Activities at Reservoir’s Waterfront Area.” Journal of Architecture and Planning 70 (598): 87–94. doi:10.3130/aija.70.87_6.

- Totman, C. 1989. The Green Archipelago: Forestry in Preindustrial Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Yamashita, U., K. Balooni, and M. Inoue. 2009. “Effect of Instituting ‘Authorized Neighborhood Associations’ on Communal (Iriai) Forest Ownership in Japan.” Society & Natural Resources 22 (5): 464–473. doi:10.1080/08941920801985833.

- Zhang, A., and J. Zhang. 2009. “Study On The Transformation Process Of Spatial Composition Of Luxun Park In Shanghai And Its Characteristics.” Journal Of The Japanese Institute Of Landscape Architecture 72 (5): 595–600. doi:10.5632/jila.72.595.