ABSTRACT

Recently, there has been a phenomenon wherein smartphones have begun to serve as substitutes for televisions in domestic spaces. However, there have been few studies of investigating the relationship between smartphone use and domestic spaces. To obtain a deeper understanding, this study intends to investigate how smartphone use has influenced the behaviors of residents within their domestic spaces. In particular, this study first aims to examine the interrelation between smartphone use and the domestic spaces of single-person student households. To this end, this study conducted on-line surveys and semi-structured interviews based on non-probability purposive sampling. The research participants were asked about their media technology use and the behavioral characteristics of their single-person households, the differences in their preferences between watching television and using their smartphones, and relationships between smartphone use and the physical environment of single-person households. The findings of this study suggest that participants often lose interest in the vertical walls of their domestic spaces due to the postures they maintain while using smartphones. Instead of paying attention to vertical walls, smartphone screens have become versatile places wherein people can communicate with others and enjoy leisure activities. Based on these findings, this study proposes three design suggestions.

1. Introduction

Since the 2010s, two phenomena – the increased use of smartphone technology and the rise of single-person households – have emerged, and they continue to generate a great deal of attention in Korean society. These phenomena were deeply embedded in the Seoul International Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2017, which explored a new paradigm of urban architecture, “Imminent Commons.” This paradigm allows every individual to concretize his/her interest in what and how to share in metropolitan cities such as Seoul, Beijing, Tokyo, Shanghai, London, Paris, and New York. The co-directors of the Seoul International Biennale 2017 posited that today’s constantly evolving media technologies and high concentration of single-person households were the primary factors causing them to reconsider the roles of modern architecture, the local community, and the city.

Specifically, media technologies have changed the Korean lifestyle as well as the ways in which people connect and collaborate in the social context, both at work and at home. They have also played a crucial role in helping normalize the Korean public education system, which has suffered heavily during the current COVID-19 pandemic. Smartphones hold the top position of present-day media technologies. On January 9th, 2007, Steve Jobs, the late co-founder of Apple introduced the iPhone as the world’s first smartphone. Jobs told the audience at Macworld, “Every once in a while, a revolutionary product comes along and changes everything.” Since the iPhone’s release on January 29th, 2007, the smartphone has affected each and every area of society, politics, the economy, and culture, as well as individual lifestyles. Moreover, over the last decade, smartphones have functionally replaced a variety of media technologies, such as newspapers, maps, calendars, bankbooks, electronic organizers, GPS navigation, computers, and televisions. Let us consider some examples of how smartphones function in our daily lives: After waking up to a smartphone alarm, we usually check the date, time, and weather conditions, after which we search for the latest news, current traffic information, and trends on social media. In our free time, we enjoy surfing the web, playing games, watching videos, and listening to music. In the workplace and other public environments, we mostly use our smartphones for things like meetings, marketing, social commerce, public services, big data, and financial transactions. Smartphones allow us to stay connected anytime and anywhere, and they have thereby become media platforms for accessing a wide variety of data and information in real time. According to a 2017 report on internet usage, single-person households with residents under the age of 40s use smartphones via wireless internet more often than cable TV and landline phones, which are generally used by those in their 60s and over (Ju et al. Citation2017, 161).Footnote1 Of these younger single-person households, 70% prefer to consume their desired content whenever they want via their smartphones and have completely gotten rid of televisions in their homes (Lee Citation2020, 8).Footnote2

This situation necessitates research into the impact of smartphones on the domestic spaces of single-person student households. Since the late 1970s, televisions have allowed people to gather in the living rooms or other main rooms of dwellings, and televisions have defined the characteristics of those rooms. We can assume that, like television usage, the near-ubiquitous use of smartphones since the late 2010s has changed such dwelling spaces. Specifically, in this study, I hypothesize that this media technology has led to changes in ways of being, thinking, behaving, and dwelling among residents in domestic spaces as well as the rest of their everyday lives. Statistical figures related to digital media may already reflect this trend.

Beyond the superficial results represented by the statistical figures, this study intends to meticulously observe and analyze how smartphone usage influences the ways in which residents utilize the domestic spaces of single-person households, or how it has changed their domestic spaces. Since it is recognized as a constant but subsidiary factor, the smartphone, unlike the television, may not be understood and observed in terms of its effects on the domestic spaces of single-person households. Therefore, this study examines how smartphones have influenced the ways in which the residents of single-person households perceive and use architectural spaces, similar to how television have previously influenced the same.

In sum, this study delves into the impact of a media technology specifically, smartphones on the domestic areas of single-person student households in terms of residents’ spatial behaviors and perceptions, as well as their methods of spatial organization. In other words, this study investigates how the college students of single-person households who actively use smartphones treat floors, walls, and ceilings as physical elements to perceive and recognize architectural spaces, as well as how they reorganize the domestic spaces formed by these boundaries. Based on this investigation, three design suggestions are provided for the domestic spaces of single-person households.

2. Research methodologies

The methodological approaches used in this study fall into three categories: 1) theoretical framework and literature review, 2) on-line surveys and semi-structured interviews, and 3) design implications. First, the theoretical framework lays the groundwork to analyze the impact of media technologies on the domestic spaces of single-person households and the literature review focuses on previous studies related to media technologies in their domestic spaces. Second, the on-line surveys and semi-structured interviews are designed and conducted to understand the smartphone use of single-person student households and its impacts on the domestic spaces of single-person student households. The results obtained from the information collected through the surveys and interviews are discussed, and then the stated hypothesis is verified. Third, the design implications are drawn from the results and discussion. Therefore, this study proposes three suggestions for improving the domestic spaces of single-person households, based on several considerations associated with such households. Then, conclusions, limitations, and future studies are presented.

3. Theoretical framework and literature review

3.1. Theoretical framework

This theoretical framework first explains the transition from modern residential areas in which the television was previously enormously influential to the current domestic areas of single-person households where the smartphone is now considered not only a part of daily life, but also a basic necessity. This study suggests that the transition of the media technologies leads to a change in residents’ attitudes toward their domestic spaces.

An early attempt to explain domestic spaces through media took the form of a seminal essay entitled, “The exhibitionist house,” which was written by Beatriz Colomina (Citation1998). In this essay, Colomina asserted that the house was the most important means of studying the architectural ideas of the twentieth century, adding that its domestic spaces have been changed by various media technologies. Using several concrete examples, Colomina also illustrated how the introduction of new media led to a reorganization of the domestic spaces of the twentieth century. At the center of this reorganization is the television. First, avoiding glare or reflection on the television screen was an essential condition in domestic spaces. To meet this essential condition, the television needed to be placed away from all window walls and therefore came to replace the fireplace, which had previously occupied the center of the domestic space. Thus, the central position of the fireplace gave way to that of the television. What was worse, since the fireplace was typically not placed near a wall with windows, it eventually was moved further and further away from the center of the domestic spaces. Second, the television transformed the domestic spaces into a type of theater. This transformation established a new relationship between the public and private areas of the home. In other words, the television invaded the public sphere of the domestic space, thereby changing it into a private sphere. It appears that the privatization of public space caused by the smartphone of today began with the changes brought about by television in the twentieth century.

In a 1956 article in Dissent, “The world as phantom and as matrix,” Gunther Anders discussed the real and fictional (or virtual) issues on television, centering not on the content but on the form that was dealt with by television as a media technology. Anders (Citation1956) posed that the world seen through television was a world which was half-present and half-absent, both real and imaginary, and made up of being and appearance (20). In other words, television is a media technology that can recreate the existential ambiguities of the world. The media technology does not merely convey the real world to domestic spaces, but also changes the actual reality of residents in those spaces as well as their understanding of reality. However, television use stops TV viewers from interacting with the media, thereby inducing them to be passively involved in images transmitted by the media (Shim Citation2012, 108). The invasion of the media technology into their personal spaces also deprives them of their spare time. Thus, the television which occupied the center of domestic spaces dominated the twentieth century, during which it imposed restrictions on residents’ views and experiences and their corresponding activities.

As the 2010s progressed, various media technologies emerged and evolved, and the smartphone absorbed and replaced an increasing number of the critical functions of previous media technologies, specifically television, in domestic spaces. Apparently, television and smartphones continue to coexist; however, the former cannot continue to exert its dominance over the domestic spaces of single-person households and, moreover, it has even been removed from many of the spaces of single-person student households. The smartphone has filled the void left by the television in the domestic spaces of college students living in single-person households.

In the era of the smartphone, which began in the 2010s, the smartphone has come to provide incessant and deeper immersion than the television, partially due to its interactivity. The widespread use of smartphones has led to a breakaway from typical media technologies (e.g., radio, telephone, or television) through which users passively consume content that is provided unilaterally (Lee Citation2015, 88). The smartphone actively supports a new mode of consumption called “the simultaneous use of media.” In a 2012 consumer study by Google, 77% of those surveyed reported simultaneously using other screens while watching television. In addition, a 2015 Accenture report showed that 87% of consumers employed second screens while watching television (Mann et al. Citation2015, 6). The second screens used in domestic spaces include smartphones, tablets, laptops, desktops, and others. The smartphone is the dominant form of second screen because it is the most convenient and easily accessible. In a work entitled, “The future of content,” Sang-Woo Lee (Citation2015) argued that media multi-tasking reflects a new trend in media consumption (89). Media multi-tasking became a widespread phenomenon over the last decade (Neate, Jones, and Evans Citation2016, 42).

With this phenomenon, the transition in preference from television to smartphone became the general condition of today’s digital society. This study assumes that this general condition is also involved in some behavioral changes in domestic spaces. The view of this study, which maintains that media technologies are closely connected to spatial changes, is essentially dependent upon Marshall McLuhan’s contention that “All media are extensions of some human faculty – psychic or physical” (McLuhan and Fiore Citation1967, 26). Further, in Understanding media: The extensions of man, McLuhan (Citation1964) suggested, “With television came the extension of the sense of touch or of sense interplay that even more intimately involves the entire sensorium” (289–90). After half a century of the dominance of television, the current ubiquity of smartphones leads to open questions: Which senses have been extended? How are those extended senses engaged with domestic spaces? To respond to these questions, we need to closely observe domestic spaces and investigate the patterns of residents’ behaviors and the architectural elements in those spaces.

3.2. Literature review of previous studies

Over the last decade, studies on new media technologies and single person households have been actively conducted in diverse areas. These studies cover a broad range of subjects ranging from new technologies to communication and residential trends. However, the studies examining the relationships between media technologies and domestic spaces have been insufficient to reveal the impact of media technologies on the domestic spaces of single-person households.

To examine the impact of media technologies on the domestic spaces of single-person households, a systematic literature review of articles was conducted that included the keywords “television”, “smartphone”, “media technology”, and “single-person household” and that searched for studies published within 5 years starting from January 2017, using two online databases: Google Scholar and AURIC (Architecture and Urban Research Information Center). 823 articles were retrieved, and 53 of them were found to be suitable for this literature review for the topic in question. These 53 articles were classified into three categories – media technology use, single-person household, and their combination organized by publication year ().

Table 1. List of keywords of articles on media technology and single-person household published since 2017.

The 6 articles that fell into the first category – media technology use – deal with issues on smartphone usage by elderly people (Seo et al. Citation2020), the impact of the smartphone use on commuting workers’ behaviors (Jang Citation2018), and an analysis of the contributors to smart TV use (Lee Citation2021), and TV consumption patterns. These articles show several patterns in media technology consumption by the user’s class; however, they did not link the media technologies to domestic spaces. The 18 articles in the second category – single-person household – the shared several common features associated with communication and interaction with others in a shared space (Liu et al. Citation2020), efficient designs under the conditions of cramped spaces (Ryu and Chu Citation2020; Lee and Kim Citation2018a; Lee, Hwang, and Kim Citation2017; Choi and Yoo Citation2017), and their residential needs reflecting the lifestyle of single-person households (Lee and Mo Citation2021; Lee and Kim Citation2018a; Shin and Lee Citation2018; Lee and Eom Citation2018). Interestingly, several articles in this category have attempted to explain the connections between preferred domestic spaces and lifestyle factors, which include home security, attachment to home, digital smart devices, and social activity (Kim Citation2020, 24–26). In the third category combining media technology use with single-person household, the 29 articles mostly focus on the emerging smart home technologies, smart home security, smart residential environment, and smart health (Jeon and An Citation2020; Khaliun and Han Citation2019; Park and Yeoun Citation2019; Chang and Nah Citation2018; Lee and Kim Citation2018b). In the articles, the meanings of “smart” can be categorized into four values of life: convenience (smart home automation), safety (smart home security), economy (smart green home), and entertainment (smart TV home) (Kim Citation2019, 1). However, the articles in the third category focus too much on the applications to new technologies to single-person households. In other words, they appear to overlook questions the relationships between new technology and domestic spaces. Nobody can tell how new technologies will influence residents and their domestic spaces. Thus, this study intends to first understand the impact of media technologies on the domestic spaces of single-person households and then suggest the applications of media technologies to their spaces.

4. Design and implementation of surveys and interviews

4.1. Participants and sampling

Due to the interdisciplinary nature of the subject matter, an approach combining an on-line survey and semi-structured in-depth interviews was conducted in July 2020 and August 2021 to collect quantitative and qualitative information. In July 2020, an on-line questionnaire was first set up using Google forms, and this was distributed to on-line survey and interview participants recruited through non-probability purposive sampling. These participants of the on-line survey and interviews were a) undergraduate and graduate students aged between twenty and twenty-nine years, b) who have grown up with their smartphones as a constant companion, and c) who have lived in one-person households (Choi and Jeon, Citation2015). With these selection criteria, this study recruited 146 undergraduate and graduate students (N = 90 female, N = 56 male), whose demographic characteristics are listed in .

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the first on-line survey and interview participants.

To supplement the quantitative and qualitative information, another set of on-line surveys and in-depth interviews was carried out in August 2021, which was based on the previous set of surveys and interviews conducted in July 2020. For the second set of surveys and interviews, this study recruited 23 students (N = 13 female, N = 10 male), using non-probability purposive sampling under the same selection criteria. The demographic characteristics of these students are listed in .

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of the second set of survey and interview participants.

4.2. Material

For the two on-line surveys and interviews, this study first composed a questionnaire with four sections and 31 questions in total. The first section comprised questions on the demographic characteristics of the research participants. The second section was made up of questions on participants’ behavioral characteristics in single-person households according to media technology. The third section contained questions on the differences between and preferences of watching televisions and using smartphones. The fourth section consisted of questions on the relationships between the use of smartphones and the participants’ physical environment in single-person households. presents a copy of the list of on-line survey and interview questions.

Table 4. List of survey and interview questions.

4.3. Procedures

To understand the impact and consequences of smartphone use on the living spaces of undergraduate and graduate students residing in single-person households, this study conducted surveys and interviews with students attending college or university, living in single-person households, and who often use smartphones. In particular, this study focused on the link between smartphone usage and people’s perceptions of the physical environment of their single-person households. Therefore, this study targeted college or university students in their twenties.

As already mentioned above, on-line surveys and semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted in July 2020 and August 2021, respectively. The first on-line questionnaire was distributed to 146 college or university students who expressed an interest in this study and who satisfied the three selection criteria and 146 completed questionnaires were returned. Based on the survey results, one-on-one follow-up interviews were conducted to obtain additional information. The participants who provided verbal consent were interviewed in person. They were advised that their voices would be recorded and that their recorded voices would remain confidential and be anonymized. All interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide that enabled participants to discuss the experiences of their smartphone usage and their single-person households (Galletta Citation2013).

However, the results of the interviews needed to be supplemented. Therefore, an additional survey and interviews were carried out on the topic in August 2021. Twenty-three on-line questionnaires were distributed to eligible participants who could represent the target population, and all 23 were returned. Then, the participants who provided verbal consent were interviewed either in person or using the video conferencing application Zoom. Prior to the interview, each participant was advised that his/her voice would be recorded and that the recorded data would remain confidential and be anonymized. All interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide that helped participants talk freely about the experiences of their smartphone usage and their single-person households.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Results of survey and interview findings

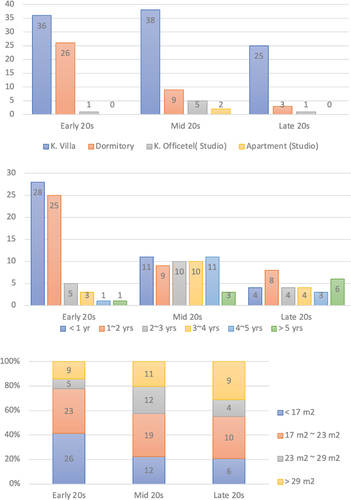

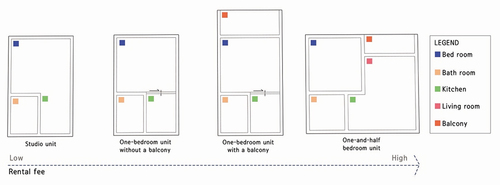

The first section of the online survey questionnaire concerns the demographic characteristics of the research participants, such as their gender, age, province of residence, housing type, length of residence, and size of residence. The first survey, conducted in July 2020, showed that approximately 68 percent (n = 99) of research participants live in Korean villas and 66 percent (n = 96) rent compact houses under 23 square meters in size (). Due to external factors, particularly the intractable economic limitations, most single-person households in their 20s reside in small housing types, such as Korean villas (a type of small apartment), Korean officetels (multipurpose buildings), and dormitories. Among these housing types, Korean villas, especially studio units, are the most affordable for those in their 20s ().Footnote3 In cramped studio unit, they even experience unstable housing conditions, such as short-term two-year.

Figure 1. Housing type (top), length of residence (middle), and size of residence (bottom) of research participants living in single-person households.

Figure 2. Housing type (top), length of residence (middle), and size of residence (bottom) of research participants living in single-person households.

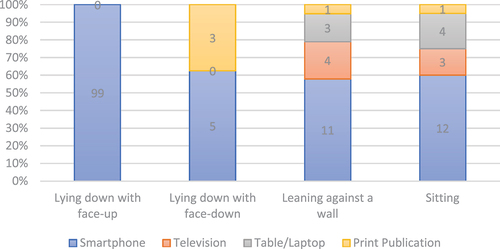

In the second section, when asked about their cramped studio units, the participants mentioned that their inactive behaviors were associated with their living spaces. Specifically, when inside their own homes, they were unintentionally forced to refrain from active behaviors and spent more time on sedentary or inactive behaviors including resting, sleeping, or watching various forms of digital media (). This pattern of behaviors may reflect their ambivalence toward the expansion or contraction of the domestic spaces of single-person households. Relevant examples include the kitchen space, the living room space, and the bathroom, which the participants wished not only to expand, but also to reduce: While 20 percent (n = 29) of participants want to expand their kitchen, 18 percent (n = 26) of them want to reduce the same space. Further, while 34 percent (n = 49) of them want to expand their living room, 13 percent (n = 19) of them want to reduce the same space. While 14 percent (n = 20) of them want to expand their bathroom, 8 percent (n = 11) want to reduce same space. This means that the participants have adjusted their behaviors as much as possible to fit within their minimal residential areas. In addition, when asked to list one thing that they were reluctant to share with others in such a cramped space, 31 percent (n = 45) of survey participants chose a bathroom (toilet), 27 percent (n = 40) chose a resting and sleeping space (bed linen, pillow, and wardrobe), 21 percent (n = 31) chose a bathroom (shower utilities), 8 percent (n = 12) chose a living space (television, table/laptop, and washing machine), 6 percent (n = 8) chose a kitchen space (refrigerator and sink), and 2 percent (n = 3) chose a balcony space (). These responses indicate that they were repulsed by the idea of sharing furniture and fixtures directly connected to personal hygiene. In other words, how much physical contact is involved in their domestic spaces represents a primary concern.

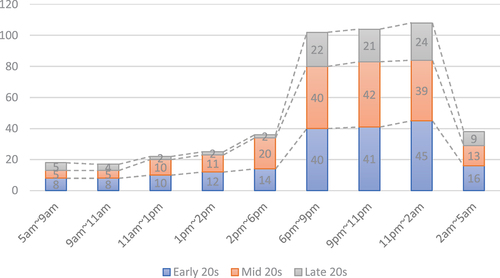

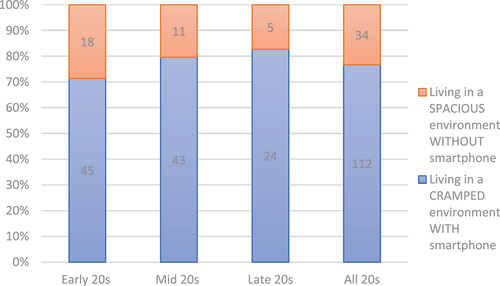

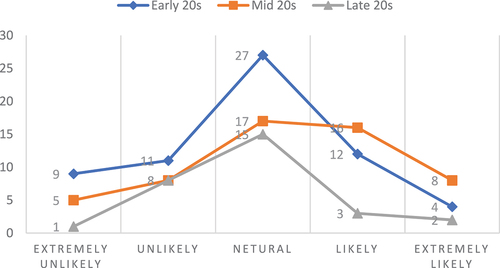

In the third section, the questionnaire asked about the media technology-related preferences of the survey participants as well as when, where, and how they used their preferred media technology. When given a choice between the television and smartphone, 92 percent (n = 135) of research participants in their 20s preferred the latter to the former.Footnote4 In particularly, participants in their early 20s, called Generation Z,Footnote5 showed marked differences in their preference for the latter over the former. Their early access to smartphone technology may have resulted in unconscious changes in the participants, since smartphones serve as a type of “lean-forward media” – that is, a media technology in which users can be fully immersed (Jansz Citation2005, 222), unlike the television.Footnote6 The participants in their 20s showed a specific temporal pattern of smartphone consumption: There were three sets of peak smartphone usage hours: between 6 and 9 pm, between 9 and 11 pm, and between 11 pm and 2 am. This shows that the participants continued using smartphones until 2 am, and their usage slightly increased at this late hour (). In an in-depth interview, the participants explained that they intentionally or habitually used their smartphones to mitigate the feelings of loneliness and emptiness that they were struck by in their dwelling spaces after school or work. Therefore, as illustrated in , participants in their 20s mostly reported that they would prefer living in a cramped space with a smartphone to living in a roomier space without a smartphone.

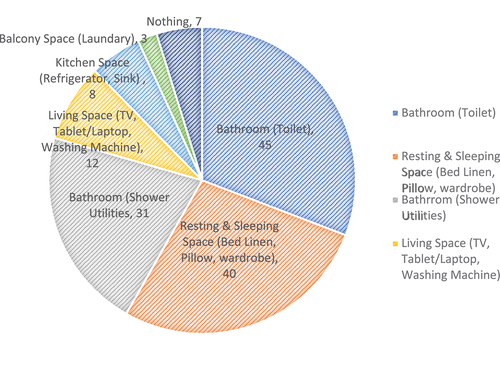

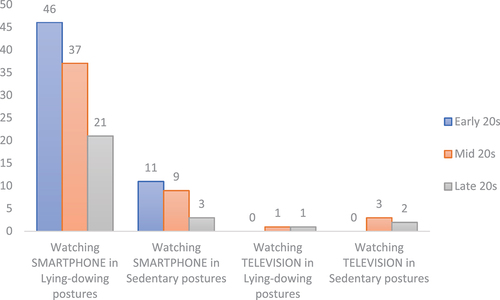

When designing this section of the questionnaire, the author wondered what types of multitasking the survey participants do while using their smartphones at home. The participants reported that, because their smartphones are portable and can be accessed anywhere, almost all behaviors, from watching television to taking showers, doing household chores, and having meals, can be performed while using a smartphone. Interestingly, the participants used their smartphones even while watching televisions. In in-depth interviews, several interviewees responded that using their smartphone helped break the boredom of watching television while allowing them to search for information they need while watching television or multitask in some other way. This phenomenon may be thought of as a defining feature of Generation Z, who typically want to watch short video clips. In addition, the participants’ answers to a question on the relationship between their preferred media technology and their physical posture while using the media technology revealed that those in their 20s preferred using smartphones while in lying-down postures to watching television while in sedentary postures (). Interestingly, regardless of their postures, they reported mostly using their smartphones and even becoming accustomed to watching TV shows on their smartphones.

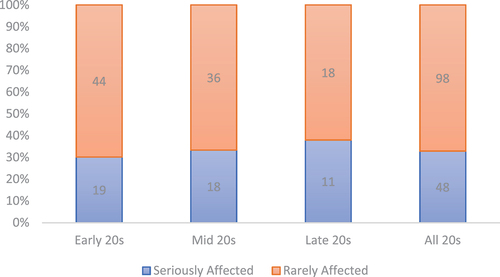

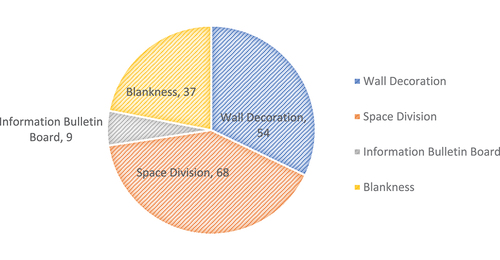

The questions in the fourth section of the questionnaire are generally focused on the extent to which digital technologies dominate the participants’ living environments, specifically how smartphones have affected participants’ behaviors in their dwelling space (or a single room) and how they have changed the participants’ attitudes toward the vertical walls as the physical boundaries of that space. First, while using smartphones, how much do people physically experience the size of the space in which they live, or how much are they personally influenced by the size of their enclosure? The participants indicated that they were not much affected by the size of their living space or their enclosure while using smartphones (). For participants in their 20s, their excessive immersion in their smartphones far outstrips any recognition of their physical space. This result indicates that, while using smartphones, they became not only desensitized to, but also uninterested in their surroundings. By the same token, the participants in their 20s responded that they often employed their interior walls as a space-dividing element (n = 68) or as a decoration surface (n = 54), or they left them as blank as possible (n = 37) (). In the in-depth interviews, participants mentioned that, even when they used the walls as decoration surfaces, they simply posted several pictures of their friends on them.

Figure 9. The extent to which residents are affected by their physical environments while using their smartphones.

Figure 10. Participants’ practical ways of utilizing interior walls in domestic spaces (multiple-choice options).

This first question led to a follow-up question about whether and how the participants feel online spaces through their smartphones as private spaces or public spaces. In response to this question, 78 percent (n = 114) of the participants felt that online spaces that they access with their smartphones were private. In a similar vein, this study went on to ask participants how much they feel that they psychologically and virtually belong to the space of the digital media they access while using smartphones. This study surmised that, due to smartphone usage, participants in their 20s appeared to experience the offline space enclosed by vertical walls and horizontal ceilings not just as a barrier to their physical selves, but also as a shelter for their virtual selves, which extended into the digitally-networked online spaces. However, the survey result showed that 40 percent (n = 59) of the participants took a middle ground () and stated that, although they had been immersed in watching their smartphones, they felt that they still appeared to be outside of the digitally-networked online spaces. In the in-depth interviews, the interviewees said that smartphones did not serve as a gateway to connect between offline spaces and online spaces, since it only satisfied their visual needs, and not their other perceptual needs. Thus, they appeared to think of online and offline spaces as being separate spaces. Only 9.6 percent of the participants (n = 14) strongly felt that the online and offline spaces were interconnected ().

5.2. Discussion of survey and interview findings

In the process of examining the relationship between the use of media technologies and residents’ behaviors in the domestic spaces of single-person households, this study obtained a result showing that their preferred media technology, specifically smartphone, was used as a tool to not only help them adjust to their cramped living conditions, but also to mitigate the feelings of loneliness and emptiness that struck them in their living spaces.

Due to the confined nature of their living conditions, the residents of single-person households reported spending most of their time sitting or lying down on their beds. One of the survey results showed that 29 percent (n = 42) of the survey participants agreed that, if possible, their bedroom space needed to be extended. While agreeing on the result, interviewees explained that, in their bedroom space, their bed had become a place on which they spent a lot of time, either for relaxing their body and mind or for using media technologies. This means that they often lie down on their bed while using their smartphone, which is the most suitable device for their sedentary or lying-down postures. There was another reason that smartphones became the most significant media technology in their cramped spaces. In the August 2021 interviews, several interviewees mentioned that, since the spaces of single-person households were rarely soundproofed, they were always careful not to make noise in their living spaces. Therefore, they preferred using their smartphones to other media technologies, while wearing wireless earphones. As evidenced by the result that 78 percent (n = 114) of the participants feel that the online spaces they access using their smartphones are private, the privatization of space that occurs while using a smartphone takes place not merely in public spaces, but also in their private dwellings. In the semi-structured interviews, one of the interviewees said that, through the feeling of privatization in their living spaces while using their smartphones, the residents of single-person households can temporarily alleviate their feelings of loneliness and emptiness. However, although using their smartphones has allowed them to adjust their given living conditions, they still wish to improve their living spaces.

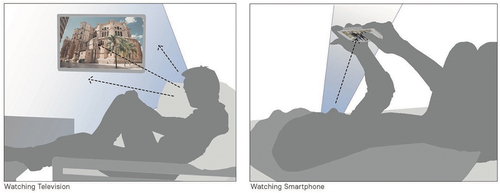

In addition to the examination, this study continued to investigate the impact of the preferred media technology use on residents’ behaviors in the domestic spaces of single-person households. Today, two types of media technology – the television and the smartphone – have come to dominate our domestic spaces, and interestingly, these have led to different postures and behaviors of residents in domestic spaces (). A television is typically set up against a vertical wall, and it requires the viewer to maintain a certain distance. Thus, residents not only keep their posture parallel to the television screen, but they also keep their attention on the vertical walls of their dwelling space. In other words, in addition to the television screen, they tend to see the walls as well as the various types of visual media hanging on the walls. However, since the smartphone requires a greater degree of immersion, it is kept within arm’s reach. Smartphone users keep the smartphone’s screen horizontal (or tilted) to prevent or minimize any inconvenience to their hands. Thus, they maintain a variety of typical postures, such as having their heads lowered, lying flat on their back, or lying with their faces down, to keep their eyes parallel to the screen. For this reason, their eyes are typically directed toward the ceiling or floor; nevertheless, they do not see the ceiling or floor. During this time, they may continuously attempt to connect, disconnect, or reconnect with online networks. However, the interviewees expressed that the limited size of the smartphone screen prevented them from immersing themselves in the online networks, and that the visually-oriented nature of a smartphone cannot serve as a psychological and technological gateway to connect between offline and online spaces.

Given the different postures and behaviors according to the media technologies being employed, the residents of single-households appear to have obvious preferences between television and smartphone usage. Compared to the television, the smartphone is more suitable for residents to live, enjoy, and relax with in a cramped environment. In cramped environments, they have continued to find the most comfortable and stable postures to use their smartphones, as they have preferred: lying-down postures within arm’s reach.

6. Design implications for the domestic space of single-person households

The results and discussion presented above allow us to recognize the role and impact of a digital media technology – the smartphone – on the domestic space of single-person households. There is no denying the role of smartphones in our daily lives. As mentioned in the results and discussion of the survey and interviews, members of generation Z are less aware of their physical environments when consuming content on their smartphones. Like the television, which has allowed the older generation to travel all over the world from their living rooms in the 1900s, the smartphone has shaped the experiences and subsequent attitudes of the younger generations in the 21st century. Average daily smartphone screen time has already surpassed television screen time in the domestic spaces of single-person households. Some spaces of single-person households do not even have any space in which to place a television.

In addition, understanding the attitudes of residents towards the inner vertical walls of single-person households will provide a new practical angle to inform the design of domestic spaces in such households. Therefore, this chapter will propose three designs for improving such design.

6.1. Three design considerations for the space reconfiguration of single-person households

Based on the understanding of the changing media technology conditions and the behavior of residents in single-person households, this study suggests three design considerations for the space reconfiguration of single-person households.

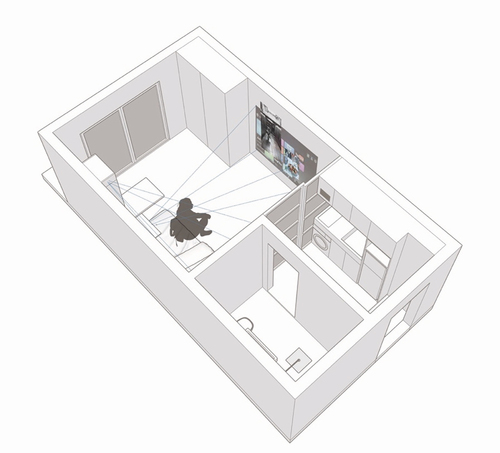

The first consideration relates to the physical locations in which the television and the smartphone are deployed and in which they play a pivotal role in the domestic spaces of single-person households. The television is typically placed against a wall at an appropriate viewing distance to make watching it more convenient for domestic residents.Footnote7 This television watching space has become a primary design constraint for a general living room. While the television functioned as a household fixture in the living rooms of the twentieth century, the smartphone has emerged as a personal ubiquitous technology in the domestic space of the twenty-first century. This technology has reduced the opportunities for family gatherings in living rooms and increased the opportunities for media consumption in private bedrooms. Therefore, the role of a living room as an area between two walls occupied by a television and sofas should be reconsidered. The second consideration relates to the typical postures maintained by smartphone users. Unlike a television, a smartphone is typically held with one or both hands, and the relative position of the smartphone varies depending on the body postures of the smartphone user.Footnote8 Users’ body postures are largely classified into three categories: standing, sitting, and lying down. Among these postures, the lying down posture is the most preferred, according to the analysis presented in the previous chapter. This posture can be subdivided into lying face-down on the floor, lying face-up towards the ceiling, and lying on one’s left/right side facing a vertical wall. All of these postures naturally face horizontal or vertical surfaces. However, using smartphones in these postures at home reduces the user’s awareness of the presence of the surfaces in the room because they are immersed in their phones. Moreover, their attitudes towards walls while in the standing and sitting postures are almost the same as their attitudes while in the lying down posture. The third consideration relates to the extended roles of the smartphone and the reduced roles of walls. As mentioned in the previous chapters, smartphone platforms already function as digital substitutes for the conventional types of analogue media, such as pictures, posters, newspapers, clocks, and calendars, which are posted on vertical walls. Thus, the roles of inner walls have been altered; the walls simply serve to divide and decorate spaces. Due to this trend in the function of interior walls, their roles need to be redefined. As the current smartphone technology has advanced, smartphones have taken on a critical role in the IoT-based home environment where everything in the home can be interconnected via Wi-Fi tethering technology.

6.2. Three proposed designs for single-person households

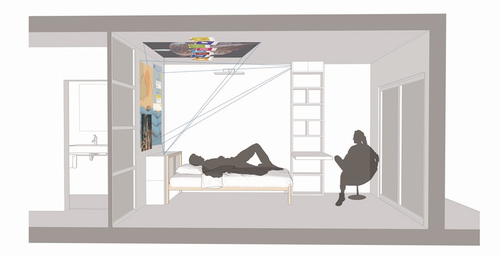

Based on these considerations, the first design suggestion involves the installation of interior media walls ( and ). In general, existing media walls for marketing and branding are typically installed on the exterior envelope or interior hall of a building. Such media walls can also be customized for the domestic spaces of single-person households and controlled by smartphones using the Wi-Fi tethering technology. This design suggestion cannot yet be realized in practice, as there are limitations involving inadequate technology, high cost, and high maintenance requirements. Thus, a more efficient and realistic way to create such interior media walls is to use a beam projection system that not only displays interactive images onto floors or walls, but that also allows the user to change the sizes of the images being displayed ( and ). Due to this the beam projection system, the interior walls function as a structural element, a physical boundary, and a projection screen, and they thereby provide an environment in which the domestic spaces of single-person households are optimized for screen media consumption. If a projection screen is to be applied in this manner, then one should avoid covering the interior walls with textured wallpapers and finishing materials. In so doing, this design idea will assist the residents of single-person households to extend not only beyond the level at which smartphones allow for a visual extension of physical space, but also to perceive interior physical walls as a personal gateway for virtual space.

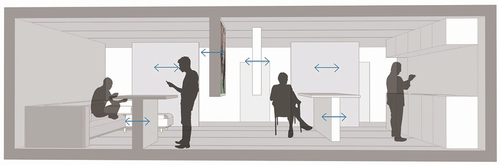

The second design suggestion involves the installation of movable walls (). Movable walls can accommodate the need to expand or reduce the available space with little cost or labor. Specifically, movable walls allow a studio unit to be customized according to the particular needs of the residents. To secure a larger bedroom within the studio unit, residents have generally been willing to give up their living rooms. Thanks to smartphones, their living rooms no longer need to function as a space for gathering and watching television. However, they may still hope to make the remains of bedrooms and kitchens into a flexible space for activities such as meditating, reading, playing games, watching videos, web surfing, and home training, without a focal point for the television. In other words, the flexible space in the studio unit will allow residents to not only live their lives, but also take part in various online and offline activities. Movable walls are a cheap and effective way of creating this type of multi-purpose flexible space in single-person households.

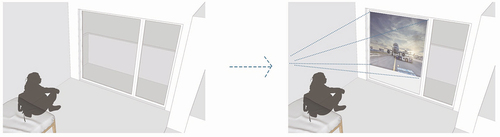

The third design suggestion involves the installation of smart glass walls ( and ). These smart glass walls are one of the most effective ways of establishing or erasing visual boundaries between inner and outer spaces. With electricity, light, or heat, the smart glass walls morph from opaque to transparent and vice versa. Current switchable smart glass technologies include electrochromic, photochromic, thermochromic, suspended-particle, micro-blind, and polymer dispersed liquid crystal (PDLC) devices. PDLCs are the most widely used of these smart glass technologies. Specifically, PDLC screens, a type of smart film that is easy to bend or roll, are often used in inner and outer spaces for privacy control. As the degree of transparency of PDLCs can be changed, these switchable smart glass devices can function not only as partitions or blinds, but also as digital projection screens. This type of smart glass wall is even more effective in combination with a media wall and movable wall. In particular, when applied to windows, a camped studio unit can be visually and psychologically expanded by using media walls.

7. Conclusions, limitations, and future studies

7.1. Conclusions

This study leads to three conclusions. These conclusions provide an opportunity to reconsider the role of digital media technologies, specifically smartphones, in the domestic spaces of single-person households, and they complement the findings of previous studies examining the residents of single-person households and their spaces.

First, the residents of single-person households have stopped paying much attention to the walls that enclose them in their dwelling spaces. Today, the physical walls of single-person households are considered to be blank or vacant. Several decades ago in South Korea, unprivileged families lived together in a single tiny room. The four interior walls of the single room functioned as a bulletin board on which the dreams and daily lives of each family member could be posted. In 2019, the domestic spaces of single-person households already surpassed those of a family of four (Korean Statistical Information Service Citation2020, 5). These domestic spaces became individual, private spaces free from the interference of others. However, the residents of these intimate domestic spaces often do not post calendars, pictures, scribbles, or even phrases that they like on their walls. Instead, they extend their own intimate spaces through the social networking services installed on their smartphones. Analogue media has been absorbed into smartphones, which users then reorganize on the virtual walls of their digital spaces, instead of the physical walls of their single-person households.

Second, a smartphone functions as a versatile screen, not a personal gateway, in the domestic spaces of single-person households. As mentioned above, the physical walls of their domestic spaces no longer function as a place to dream about their future, but as a boundary to define their spaces. Instead of the physical walls, their smartphone screens become versatile places for communicating with others, watching video clips, collecting data, searching for information, and purchasing products. However, smartphone still fail to function as personal gateways connecting between physical space and virtual space or between offline space and online space. This is because smartphones cannot overcome the limitations associated with their visually-oriented nature that cannot completely cover other senses. Therefore, the residents of single-person households use the smartphone not as a personal gateway, but as a personal tool to allow them to adjust to their cramped domestic spaces.

Third, this study examined how media technology profoundly influences residents’ behaviors and their use of the domestic walls in single-person households. Based on the examination results, this study offers three design suggestions respectively employing media walls, movable walls, and smart glass walls. Undoubtedly, these design suggestions will not be the final outcomes. Many follow-up studies need to be conducted, since the current domestic walls of single-person households may not completely reflect the behaviors of generation Z, who are immersed in smartphones. By understanding their behaviors towards the interior walls of single-person households, this study provides a new and practical perspective for the design of such domestic spaces. In other words, when commissioned to design the spaces of single-person households or to propose apolitical alternatives, architectural experts such as architects, government officials, and scholars should suggest new and practical ways to change domestic spaces by focusing on the existing walls of such spaces.

7.2. Limitations and future studies

This study has some limitations. First, since all the samples were collected through a purposive sampling technique, there is a possibility of bias which may influence the decision. Although best efforts were made to collect relevant data from online surveys and interviews, they may not have been sufficient to represent the general population. Due to these limitations, further research needs to be conducted with a larger sample across the country to introduce keen insights. Second, this study was focused on the specific population groups of people in their 20s. Thus, future studies can explore various population groups by age, region, education level, and other demographic characteristics. This study is merely the first step toward studying the interrelationship between new media technologies and domestic areas as well as the changed behaviors in the areas. Third, this study was also focused on specific cases and references from the Republic of Korea because it aimed for a limited understanding of thinking that the topic of this research is particular to the Republic of Korea. Therefore, future studies should consider these limitations by using a larger and randomly selected sample size of participants. In addition to future studies derived form these limitations, future works should examine the behaviors of the new generation using advanced digital technologies and their behaviors in a new type of domestic space or shared space, rather than in conventional domestic spaces.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hoyoung Kim

Dr. Hoyoung Kim is Assistant Professor of Architecture at Hanbat National University, where he works on visual representation in architectural media and its relation to human psychology and aesthetics. He is currently working on a research project on 3d digital modelling and printing.

Notes

1 This report was co-published by the Ministry of Science and ICT and Korea Internet & Security Agency. The report provides an in-depth analysis of the internet usage pattern of single-person households.

2 This finding is derived from the KISDI STAT report published on the fifteenth of June, 2002. The report analyzed the use of online motion pictures (OTT) by the types of subscriptions to multichannel television services.

3 First, the studio unit is based on an open plan enclosed only by external unit walls, without inner partition walls. The rental cost of this studio unit varies according to season, standard and location, but it is usually less costly than the other subtypes. Since the IMF crisis in South Korea, many more Goshiwons (the cheapest rental housing for examiners) have been built and developed into studio units; these are still reported as Goshiwons in the architectural register (Lee Citation2006, 29–30). Second, the one-bedroom unit without a balcony is based on a divided plan in which a partition wall is installed between the bedroom and kitchen areas. Compared to the studio unit, this one-bedroom unit provides a more comfortable residential environment due to improved hygiene and reduced noise. Third, the one-bedroom unit with a balcony has its own private open space for drying clothes, storage, and resting. Since it functions as a layer in between the indoor and open-air areas, the balcony space may considerably reduce the cost of cooling and heating this unit. Lastly, the one-and-half bedroom unit is an improvement upon the divided one-bedroom plan in which the bedroom area is separated from the combined kitchen and living-room area. Therefore, this study aims to focus on the Korean villa, and classifying this housing type into four subtypes: 1) studio unit, 2) one-bedroom unit without a balcony, 3) one-bedroom unit with a balcony, and 4) one-and-half bedroom unit.

4 In May 2017, a report published by the Korea Information Society Development Institute (KISDI) visualized the possession and usage of digital media in single-person households through statistical figures and graphs. According to the 2017 KISDI report, the rate at which those in single-person households viewed programs shown through ground-wave broadcasting systems was 10 percent lower than that of other types of households. The report also notes that, among those who watched the programs, the dwellers of single-person households were an active audience group, usually employing smartphones rather than televisions. Furthermore, an investigation of the media essential to single-person households showed that, while the older age group still prefers television, about 90 percent of those under 30 prefer to use smartphones. What is remarkable in this report is that people who choose to use smartphones have more control over what they watch. In other words, the function of the television has been subsumed by the smartphone; this includes diverse functions such as information, entertainment, and social networking.

5 Generation Z experienced political, economic, and social changes that were completely different from the social turmoil which baby boomers went through in the 1980s and the early 1990s. The baby boomers have lived in an age of uncertainty and were forced to accept many crises, such as an economic recession, company mergers and restructuring, and youth unemployment as a given condition; they went through the Korean financial crisis of 1997, the neo-liberal policies of the late 1990s, and the global financial crisis of 2008. They also felt that they were in unstable positions due to the development of information and communication technologies.

6 Television makes watchers more likely to be passive rather than active. Jeroen Jansz defined the television as a type of “lean-back media” – that is, a medium available even when the distance between the eye of the watcher and the screen of the television is relatively far (Jansz Citation2005, 222). Thus, television can be watched even in a state of mental, psychological, and physical relaxation (Kang et al. Citation2007). These studies recognize that a constant distance between the eye of the watcher and the screen of the television has been established in most dwellings. When arranging several pieces of furniture in a living room, people have usually set the television and sofa against opposite walls to leave an appropriate distance between them (at least ~ 2 meters). In consideration of its characteristics, it is necessary to watch a television from a distance. The distance can also depend on screen size.

7 Published in October of 2019, the International Telecommunication Union Regulations (ITU-R, Citation2019) recommended that the preferred viewing distance is about six times the height of the display screen in an at-home environment (64).

8 Eardley et al. (Citation2018) published an article on conference proceedings entitled, “Investigating how smartphone movement is affected by body posture.” The authors described several ways of using smartphones: “When standing for example, the smartphone rests on top of the hands, while a ‘lying on the back’ posture means the hands cannot be placed in front, blocking the screen, even to stop the smartphone from falling. Furthermore, smartphone support for all body postures is affected by the grip used” (unpaged).

References

- Anders, G. 1956. “The World as Phantom and as Matrix. On Work and Play in Industrial Society.” Dissent 3 (1): 14–24.

- Chang, M., and K. Nah. 2018. “A Study on the Interaction of Single - Person Household and Smart Device Based on the Context.” Journal of the HCI Society of Korea 13 (1): 21–28. doi:10.17210/jhsk.2018.02.13.1.21.

- Choi, D., and J. Yoo. 2017. “A Study on the Integrated Spatial Function of Households considering One-person Household Characteristics.” Journal of Korea Institute of Spatial Design 12 (5): 165–178. doi:10.35216/kisd.2017.12.5.165.

- Choi, J., and S. Jeon. 2015. Poll from the Beginning to the End. Paju: Freedom Academy.

- Colomina, B. 1998. “The Exhibitionist House.” In At the End of the Century: One Hundred Years of Architecture, edited by R. Ferguson, 126–167. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Eardley, R., A. Roudaut, S. Gill, and S. Thompson 2018. “Investigating How Smartphone Movement Is Affected by Body Posture.” In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2018), Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

- Galletta, A. 2013. Mastering the Semi-structured Interview and Beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication. New York University Press.

- Google. 2012. “The New Multi-Screen World: Understanding Cross-Platform Consumer Behavior.” Google. Accessed 10 August 2020. http://goo.gl/xdbOe1

- International Telecommunication Union. 2019. Recommendation ITU-R BT.500-14 (10/2019) Methodologies for the Subjective Assessment of the Quality of Television Images. Geneva: Electronic Publication.

- Jang, J. 2018. “Analysis of the Impact of Smart Devices on Worker’s Commute Behaviors.” Journal of Korean Society of Transportation 36 (4): 251–262. doi:10.7470/jkst.2018.36.4.251.

- Jansz, J. 2005. “The Emotional Appeal of Violent Video Games for Adolescent Males.” Communication Theory 15 (3): 219–241. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00334.x.

- Jeon, J., and S. An. 2020. “A Study on the Application of Detached House, Smart Home Service for One-person Households.” Journal of Korea Contents Association 20 (1): 180–191.

- Ju, Y., K. Lee, Y. Choi, and E. Youn. 2017. Survey on the Internet Usage. Naju: Korea Internet & Security Agency.

- Kang, M., et al. 2007. Digital Mania and Phobia. Seoul: Communication books.

- Khaliun, E., and H. Han. 2019. “A Study on the Application of Smart Furniture Development through the Satisfaction of Residents in Small Sized Apartment.” Proceedings of Korean Institute of Interior Design 21 (3): 135–140.

- Kim, J. 2019. “The Direction of Smart Residential Environment for Single Households.” Journal of Korea Furniture Society 30 (1): 1–10.

- Kim, N. 2020. “A Study on the Preference of Residential Space and Direction of Development of Service Design by Lifestyle Factors of Single Households by Age.” Unpublished master’s thesis, Hanyang University.

- Korean Statistical Information Service. 2020. “Single-Person Households in Statistics.“ Accessed 8 December 2020. http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/1/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=386517

- Lee, J. 2006. “A Study on Production and Reproduction of City Poverty.” Unpublished master’s thesis, Sungkonghoe University.

- Lee, J., and J. Mo. 2021. “An Analysis of Single-person-household’s Residential Space Situation and Space Demand by Age.” Proceedings of Korean Institute of Interior Design 23 (2): 50–54.

- Lee, S. 2020. “Analysis on the Usage of Online Motion Pictures by the Types of Subscriptions to Multichannel Television Services.” KISDI STAT Report 20-11.

- Lee, S., and J. Kim. 2018a. “A Study on the Development of Creative Design Method for the Residential Space of A Single Person.” Journal of the Korean Institute of Interior Design 27 (5): 101–113. doi:10.14774/JKIID.2018.27.5.101.

- Lee, S., and S. Eom. 2018. “An Analysis on the Housing Needs for Young Adults Living Alone.” Journal of Korean Institute of Interior Design 27 (2): 77–85.

- Lee, S., Y. Hwang, and J. Kim. 2017. “A Study of the Spatial Expansion of Furniture in Single-person Residential Environments.” Journal of Korea Institute of Spatial Design 12 (6): 79–90. doi:10.35216/kisd.2017.12.6.79.

- Lee, S. 2021. “An Exploratory Analysis of Contributors to Smart TV Usage.” Journal of the Korea Contents Association 21 (6): 524–532.

- Lee, S. 2015. “The Future of Content.” In Humans Live in the Hyper-connected Society, edited by D. Kim, 88–107. Seoul: Communication books.

- Lee, U., and S. Kim. 2018b. “A Study on Smart Home Service Plan for Single-households: Focusing on the 20s and 30s.” Journal of the Korea Convergence Society 9 (5): 129–135.

- Liu, T., S. Moon, S. Shin, and Y. Hwang. 2020. “A Study on the Communication Characteristics of Single-person Households Co-housing.” Journal of Korea Institute of Spatial Design 15 (8): 499–511.

- Mann, G., F. Venturini, R. Murdoch, B. Mishra, G. Moorby, and B. Carlier 2015. “Digital Video and the Connected Consumer.” Accenture Tech. Rep., 1–9.

- McLuhan, M., and Q. Fiore. 1967. The Medium Is the Message. New York: Touchstone books.

- McLuhan, M. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extension of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Neate, T., M. Jones, and M. Evans. 2016. “Interdevice Media: Choreographing Content to Maximize Viewer Engagement.” Computer 49 (12): 42–49. doi:10.1109/MC.2016.375.

- Park, J., and M. Yeoun. 2019. “A Proposal of the Smart Hubs Scenarios of Smart Home Users in the Near Future Based on the Use Patterns.” Journal of Integrated Design Research 18 (3): 25–42. doi: 10.21195/jidr.2019.18.3.002.

- Ryu, J., and B. Chu. 2020. “A Study on the Status of Sharehouse Space Composition for Single Household Living Facilities.” Journal of Architectural Institute of Korea 36 (6): 55–61.

- Seo, J., S. Oh, S. Oh, Y. Lee, S. Cha, J. Ho, and M. Kim. 2020. “Silver Mobilian, an Application for Solving the Digital Alienation of Senior Generation.” Proceedings of Korea Information Processing Society 27 (1): 310–313.

- Shim, H. R. 2012. The Media Philosophy of the Twentieth Century: From Analogue to Digital. Seoul: Greenbee.

- Shin, H., and J. Lee. 2018. “A Study on Housing Design Characteristics Reflecting Lifestyle Changes.” Journal of Korea Institute of Spatial Design 13 (4): 119–121. doi:10.35216/kisd.2018.13.4.119.