ABSTRACT

Local traditions have been the critical considerations in the current project of iterating architectural modernities outside of the West. Situated in these emerging debates, this article investigates an underrepresented artistic architectural modernity created by Liu Jipiao in the late-1920s China and re-evaluates the relationships among the past, tradition, and modernity. It recovers the method Liu used and how he used it to address the “past,” invent “tradition,” and create an “artistic modernity.” Moreover, it adopts the concept of collective identity to interrogate the way in which Liu harnessed the contemporary Chinese architectural zeitgeist to promote both his chosen method and the artistic modernity. Two related desires – the desire for designing tradition and the desire to define what it is to be both “Chinese” and an “architect” – had interwoven together, creating the artistic architectural modernity.

This article thus explores the possibilities of China’s multiple architectural modernities, investigating more diverse positions for the past and tradition than previous research has revealed. Meanwhile, the article’s use of the concept of collective identity unveils more perspectives on Chinese architects’ longstanding desire for tradition in building Chinese modernity and avoids simplifying the motivation for this desire into a political stance on national identity.

1. Introduction

In the current worldwide critical debate on the project of architectural modernity outside of the West, the conversation between tradition and modernity is extremely significant and active. The positions of vernacular building traditions as well as the Western precedence have addressed many critical considerations in the investigation of alternative modernities or other modernities outside the Western. For instance, Mark Crinson researched on the interaction between the Western architecture and the Middle Eastern buildings in terms of the relationship between modernism, traditionalism, and globalization (Crinson Citation1996, Citation2003). Sibel Bozdoğan and Reşat Kasaba argued for the complexities of the historical evolution of modernization in Turkey’s experience responding to the global debate on the universal project of modernity (Bozdogan and Kasaba Citation1997). Maha Samman and Yara Saifi investigated the vernacular roots as well as the aesthetic and ideological characteristics of the modern idiom and the contribution of the local peasants to the influence of modernity on residential buildings in East Jerusalem (Samman and Saifi Citation2021). Even in research on a classical Western modernity in Italy [2010] and its relationship with that in neighbouring continents [2010], the modern legacy of vernacular traditions has been examined, creating the refreshing notion of a “hybrid modernity” (Sabatino Citation2010; Lejeune and Sabatino Citation2010).

Recent research has begun to rethink China’s multiple architectural modernities as well. Duanfang Lu, whose research interests mainly include contemporary architectural and urban theories in China (from 1949 to the present) (Lu Citation2006, Citation2007a, Citation2010a) and third-world modernism (Lu Citation2007b, Citation2010b), has argued for positing multiple architectural modernities and other modernities at the level of epistemology, and for legitimatising different knowledges based on connectivity and dialogue. Edward Denison’s research, Architecture and the Landscape of Modernity in China before 1949, explored China’s encounter with architecture and modernity and investigated the heterogenous origins of Chinese modernity in its own traditions and in the unique Chinese political, social, and historical context (Denison Citation2017). Denison’s study was one of the earliest to use the theory of multiple modernities to research China’s architectural modernity and challenge the singular notion of modernism derived from the West.

China’s experience with architectural modernity and its local traditions are unique and deserve more consideration. Firstly, China has one of the world’s longest uninterrupted building traditions, which should have provided multifarious possibilities for Chinese architectural modernity. Second, as China has been exposed to dramatically complex multi-external powers, building in a distinctly Chinese tradition that honours the Chinese past has been a strong collective intention among Chinese architects, despite China’s embrace of modernity in many areas since the beginning of the twentieth century. As far as we know, the first propagandist article on this topic was published in 1919 in the English language Far Eastern Review by William Chaund, a Chinese architect who had studied at the Armour Institute of Technology. He advocated that Chinese architecture should be modern architecture modified by local traditions (Chaund Citation1919). Since then, Chinese architects’ desire and endeavour to incorporate tradition into modern buildings have endured in China for more than a century, exemplified by the 2012 Pritzker Prize-winning architect Wang Shu’s contribution to modern architecture in a Chinese context (Denison and Ren Citation2012; Lai Citation2012). Li Hua, in an article reflecting on the implications of Chinese modern architectural research for contemporary theory and practice, admitted that the relationship between the past and the modern is one of the core questions that emerged from modernity and is still alive in architecture today (Li Citation2020, 104).

This article’s contribution is thus to highlight how the desire for tradition has informed multiple possibilities of architectural modernities in China by investigating an underrepresented case in late- 1920s China. This architectural modernity was created by Liu Jipiao, a French-educated artist and architect. Previous studies related to this case have provided material evidence of Liu’s participation in some famous events (Kao Citation1972; Clunas Citation1989; Sullivan Citation1996; Ercums Citation2014; Denison Citation2017; Fei Citation2007; Xu Citation2010; Fei Citation2011; Wong Citation2013; Weng Citation2014; Lu Citation2018). However, most of these studies have concluded that Liu’s efforts to promote “artistic architecture” arose from his personal taste and from French influence under the heroic perspective of modernity. Some studies (Zheng Citation2013; Gao and Peng Citation2017) that have taken this stance have treated Liu’s practice as a personal experiment that failed because of its minority position and his lack of successors.Footnote1 The good news is that research has started to position his contributions as essential moments in a wider historical and cultural context. For instance, Xing (Citation2018) argued for the significant role of art exhibitions in establishing the identity of the Chinese architect and concentrated on the indispensable role of Liu Jipiao’s identity as both artist and architect. Furthermore, Sun (Citation2021), using architectural drawing as both subject and method, investigated how Liu Jipiao employed the power of drawing to establish the identity of the modern Chinese architect in China’s entangled political and historical contexts.

Nevertheless, a further comprehensive uncovering of what this architectural modernity consisted of, and how and why it was established, is still urgently required. Thus, this study considers the following research questions: What was the past Liu addressed, and what was the tradition he invented? What methods did he use, and how did he use these methods? Why was he motivated to create such a modernity? This research contributes to the configuration of China’s multiple architectural modernities.

2. Methodology

The primary methodology used in this study to provide a critical perspective on Chinese multiple architectural modernities examplified by Liu Jipiao’s work was the employment of the theory of multiple modernities. This theory, rather than obediently envisioning a hegemonic Western modernity, recognizes the vital role played by domestic traditions in shaping local iterations of modernity. It challenges the singular, linear, and Eurocentric conceptions of modernity and avoids the conventional perspective of Western hegemony and transmission (Eisenstadt Citation2000). Using the lens of multiple modernities, this article interprets the interaction between the Western precedence and the Chinese traditions in shaping Chinese architectural modernity. Moreover, this article distinguishes between the two terms “past” and “tradition” (Shils Citation1971; Hobsbawm and Ranger Citation2012); the former refers to the historical material Liu Jipiao consulted, and the later refers to the modern invention of a “tradition” that echoed this past. This article therefore is dedicated to rediscovering Liu’s creation of modernity by locating, through historical analysis and critical discussion, the past Liu has referenced and the tradition he invented.

These analyses and discussions constitute the following three sections of this article. The first section investigates France as the site where Liu subscribed to the collective intention of creating Chinese architectural modernity and honouring the Chinese past. This section describes the intercourse between French modernity – the specific Western precedence in this case – and the Chinese architectural modernity Liu created. The other two sections address the research questions through respectively examining two developmental stages of his architectural practice. The first demonstrates the methods he embraced and his initial experimental practice in France, and the second discusses how he transformed these methods in the Chinese context and why he did so. The what and how facets of the research questions are interrogated through analysing the visual languages and historical contexts of two sets of designs and drawings that are representative works executed by Liu Jipiao. The first set is Liu’s design of the Chinese pavilion (Section de Chine) at the Exposition internationale des arts decoratifs et industriels modernesFootnote2 (the Paris exposition) in 1925. The second set is the drawings for the entrance gate of the West Lake Exposition in 1929 in Hangzhou, China.

Finally, this article uses the concept of collective identity to investigate Liu’s ultimate motivation for promoting his design method and for using the past in creating his architectural practice (why). The concept of collective identity has been used in many subject areas, and a definition from social psychology can help clarify its use in this article. “Collective identity is an interactive and shared definition produced by a number of individuals (or groups at a more complex level) concerning the orientation of their action and the field of opportunities and constraints in which such action is to take place” (Melucci Citation1996, 70). It is an analytical tool for understanding collective action through which we can read reality, rather than an essence with an arguably “real” existence (Melucci Citation1996, 77). In this research, collective identity is used as the social mechanisms for understanding early Chinese architects’ collective intention to assimilate tradition into the modern; in the process of carrying out this intention, they established themselves as a cohort that distincted from both craftmen and engineers.

3. French connections: Liu Jipiao and the desire for tradition

Liu Jipiao’s formal and close exposure to the collective intention of early Chinese intellectuals – the desire for tradition in creating the modern – came through the manifesto set forth by Cai Yuanpei at two expositions – the Exposition chinoise d’art ancient et modernFootnote3 (the Strasburg exposition) in 1924 and the Paris exposition in 1925 in France. The manifesto was addressed three times in the two prefaces to the catalogues of the two exhibitions,Footnote4 as well as in a speech given at the opening ceremony of the Strasburg exposition (Li Citation1924).Footnote5 Although these two expositions had different themes and scopes, they had close affinity. The Chinese committees and the participants of the two expositions were drawn from the same groups of artists, the Association of Chinese Artists in FranceFootnote6 and the Chinese Society of Decorative ArtsFootnote7 in Paris. These groups comprised Chinese students who mainly studied in Paris, and exhibited objects were shared between the two expositions. The writings and the speech revealed during the two exhibitions were consistent and coherent and stressed to the same manifesto. The manifesto was a significant part of the cultural modernity and national salvation programme, based on aesthetic education and art, which Cai promoted after the May Fourth Movement in 1919, stimulated by the relative failure of political, industrial, and military modernization (Gao Citation2011).

The manifesto revealed two significant pairs of reconciliations that would define Chinese modern art: reconciling Chinese tradition with modern Western artistic principles, and reconciling art and science. Among those four general and abstract terms, “modern” and “science” were treated as representing the weaker side of Chinese art, while traditional Chinese art was highly appraised and promoted. Cai mentioned that Chinese art was able to retain its characteristic qualities despite the influence of foreign civilizations, for more than 4,000 years. In terms of how to generate and promote modern Chinese art, Cai said, “There are two conditions which are necessary for a national civilization to exist and radiate on the world: firstly, original and national civilization is the foundation; secondly, assimilating another nation’s civilization is the nutrient.”Footnote8 The other nation in that context primarily referred to France.

However, the blending of Chinese tradition into the modern was still merely at a stage of propaganda at this moment. The manifesto generally described Chinese tradition as the arts of the past. How to use this traditional past and blend it with the modern therefore became the task of the artists. The artworks of those Chinese students in Paris were methodological experiments in this blending, while Liu’s acknowledgement of the Chinese past in his interior design in the Paris exposition was the architectural outcome of the same process, a significant nod to the manifesto. Just as Lin Wenzheng mentioned in the introduction to the catalogue of the Paris exhibition, due to the chaotic situation in China at that time, China did not participate in the Paris exposition with a building of grandeur; rather, the Chinese pavilion was finished by installing the exhibited objects in some rooms with great interior decoration. However, this limitation nevertheless gave Liu Jipiao, a student of decorative art in Paris at that time, a great opportunity to experiment with his own “decorative” way of addressing the Chinese past.

4. Method finding: decoration and interior design as vanguard methods

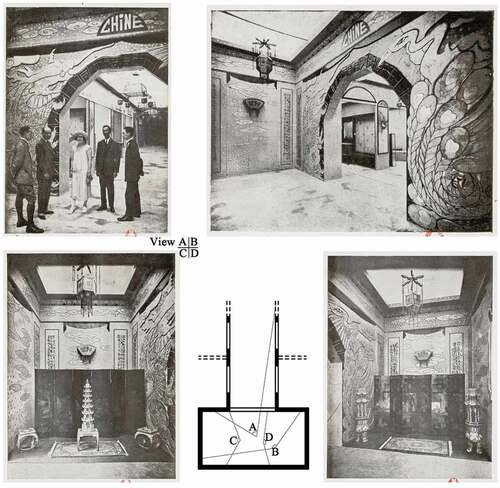

Four images in the catalogue of the Paris exposition reveal the interior design and the installation of the Chinese pavilion (). Although the rooms alongside the aisle were also Chinese exhibition rooms, judging from the artifacts, the main room in was the one that displayed Liu’s contribution of blending Chinese ancient art with his modern interior design.Footnote9

Figure 1. The interior design of the Chinese pavilion in the 1925 Paris Exposition (The plan is reconstructed by the author).

The interior design creatively used decorative motifs that recalled China’s past. Two pairs of traditional Chinese motifs, which usually appear in the decoration of Han shrines and caves, are transformed, but the prototype can still be recognized. The pairing of a dragon and a phoenix is transformed into a graphic pairing of a dragon and a peacock, situated alongside the entrance respectively; the pairing of the sun and the moon is surrounded with abstract cloud and is located on the rear wall. The conjugated pairs of motifs (the dragon and phoenix, and the sun and moon) recall typical motifs of the cosmological mythology associated with the Queen Mother (Xi Wang Mu) and the King Father (Dong Wang Gong) in the Han Dynasty (BC 202–220). The installation of the room follows the arrangement of the space in a typical Chinese room with its characteristics of bilateral axial symmetry along the central entrance and corresponding furnishings. The upper shape of the entrance to the room is formed with polygons rather than with a round or segmental arch. This kind of arrangement and setting in buildings is very often applied in Chinese religious caves and ceremonial shrines ().

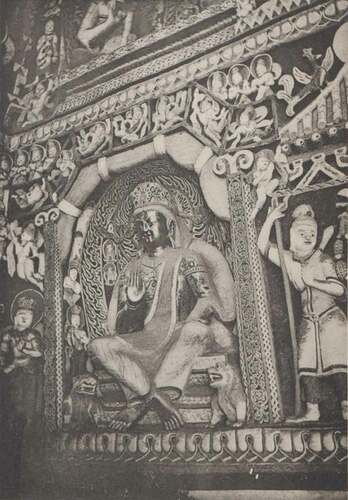

Figure 2. An image of Yun Gang grotto from the book Archaeological Mission in Northern China, published by Édouard Émmannuel Chavannes (1865–1918) in 1909. Image reproduced from (Chavannes Citation1909, PL.CXIV NO. 219).

The way Liu created the decorative motifs in his design reveal his design method, which echoes the two art trends of Art NouveauFootnote10 and Art Deco, the latter of which the Paris Exposition helped spawn.Footnote11 The flowing curves in his graphic design of the motifs are examples of one of the most important characteristics in Art Nouveau art. The dense decorative elements echo the preference for floating forms, including coloured seaweed bladdersFootnote12 and balloons (Hillier Citation1968, 61), that, in the twenties, became part of the aesthetic language of Art Deco. Art Nouveau and Art Deco alternately dominated new art trends in FranceFootnote13 in the first decades of the twentieth century. The Art Nouveau movement was in its heyday, while the successive art trend – later defined as Art Deco – was gaining approbation when Liu Jipiao and his fellow artists were studying in France.

There were two significant reasons for Liu to use decorative interior design. The first is that Chinese modern art’s respect for tradition, as evidenced in Cai’s manifesto, and its inspiration drawn from the multiplicity of the past, as evidenced in Liu’s interior design, were two significant methodologies that Chinese modern art shared with Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Although the earlier Art Nouveau style proposed extreme modernism and a rejection of historicism, the style actually never really succeeded in ignoring the past (Selz and Constantine Citation1972, 12). The Art Deco style in France, exemplified in the 1925 exposition, embraced history and the national past, unlike many other modern manifestations of movements in other countries, which rejected the past (Goss Citation2014, 3–4).

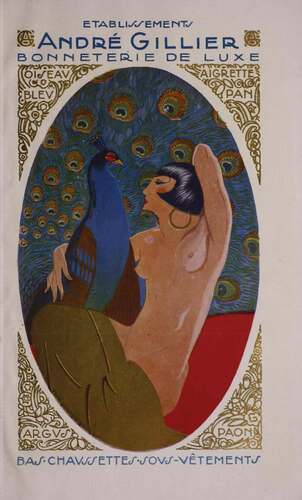

The transformative way Liu paired a peacock, instead of a phoenix, with a dragon is the clearest indication that, on the one hand, he drew motifs from China’s past to correspond with the manifesto of the Chinese aesthetic ideology, while, on the other hand, he was willing to embrace the methodology of French decorative art. The peacock was one of the most important animal iconographies used in Art Nouveau. It is notable that the official catalogue of the 1925 Paris Exposition has one coloured illustration inside, with a naked woman and a peacock (). Although later the swan surpassed the peacock in popularity (Selz and Constantine Citation1972, 16), it is evident that it is much more suitable to pair a peacock rather than a swan with a dragon both in terms of volume and of contour. As popular iconography, the prevalence of peacocks in Art Nouveau was closely associated with the French interest in an exotic past, and in the Asian artistic past in this particular case. The most renowned event promoting the use of the peacock was the design and installation of Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room () in London in 1876–1877. The Peacock Room of 1876–1877 was entirely decorated in a design inspired by Japanese interiors, and the most pronounced elements were decorative peacocks and porcelain. One of the dominant designers of the room was James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), an American artist based primarily in the United Kingdom and among the first Western painters inspired by Japanese art. His famous painting La Princesse du Pays de la Porcelaine of 1863–1864, which was influenced by Japanese painting, was also hung in the room. The peacock was therefore a popular icon that exemplified the Western exotic interest in Japanese art, or represented of Eastern art more broadly.

Figure 3. Female and peacock from an advertisement in the official catalogue of the 1925 Paris Expo.

The image of a peacock is also commonly depicted in traditional Chinese paintings and decorative drawings on Chinese porcelain. Liu also depicted a peacock accompanying the ladies in one of his paintings exhibited in the Strasburg exhibition in 1924 (). The modern use of the traditional Chinese motifs may have indicated that Chinese art could be one of the representative Asian pasts that modern art could address and build on. Liu’s transformative way of using a peacock in the Paris Exposition’s Chinese pavilion can therefore be seen as an expressly modern way of representing traditional motifs invoking the resonance of French art and artists in Chinese design in the early twentieth century and promoting Chinese art to occupy a place in modern art.Footnote14

The other reason Liu chose the method of decoration and interior design was due to his deep association with French modern art trends; he positioned himself as a vanguard figure between both the art and architectural arenas. Although the term “decoration” today has long lost the prominence it was given at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, decorative art or applied art was born in that period as a style that could accommodate the vanguard artistic ideology of many new art trends. The new art movements in France interrogated the boundary of art, redefined the identity of artists, and explored the relationship between art and industry (Hillier Citation1968, 15–17). Hillier (Citation1968, 10–11)also mentioned, “By this period the phrase ‘decorative art’ is itself question-begging, as most scholars now acknowledge that Art Nouveau had done much to blur the old distinction between ‘fine art’ and ‘applied’ or ‘decorative’ art; while artists of the twenties and thirties thought they had eliminated it altogether – enshrining the new art philosophy in the monstrous word ‘beautility.’” Fern (Citation1972, 29), in criticising Maurice DenisFootnote15 and his associates’ work, mentioned that “Decoration as we use the word today, tends to be a term of deprecation. For Denis and his associates it was precisely the opposite, signifying the highest degree of unity and beauty possible in a work of art.”

Artists working with “decoration” subscribed to the new idea of the “unity” of all art and life since the Arts and Crafts Movement and the comprehensive design of the house were very prominent (Selz and Constantine Citation1972, 7–8; Goss Citation2014, 7–9). The professional interior designer was called the ensemblier at that time. Goss (Citation2014, 7) argued that the “[ensemblier’s] creations – conceived as total works of art- encompassed not only the traditional components of interior design such as furniture and objects, carpets, textiles, and lighting, but often decorative architectural features, paintings, and sculptures as well, with the idea that such artistic expressions were integral to the aesthetic unity of a particular scheme.” The most famous representative of ensemblier at that time was E.-J. Ruhlmann. Clunas (Citation1989) has mentioned that Liu’s interior design referenced Ruhlmann’s design.

Liu Jipiao deeply acknowledged decorative interior design and the related vanguard artistic concepts. He had been a talented artist since he was a young boy, and he chose the subject of painting at the beginning of his studies in Paris. He enrolled in the Section de Peinture at L’Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts whose education was known for its support of “classical modernity.” However, he decided to transfer to Architecture and Interior Design in 1923 (Wong Citation2013). Although remaining at the same school, Liu embarked on the journey of expressing his interpretation of “modernity” rather than merely adopting heritage. One of Liu’s closest friends, Sun Fuxi,Footnote16 wrote that Liu changed his educational speciality from painting to architecture due to an inner struggle; he found architecture to the better projection of his ideology (Sun Citation1928, 5). Heynen (Citation1999, 111) has criticized that “Art nouveau represents the last attempt of European culture to mobilize the inner world of the individual personality to avert the threat of technology … It is in the interior that the bourgeois registers his dreams and desires; in it he gives form to his fascination for the other – for the exotic and for the historical past.” In his personal struggle, Liu empathised with the international bourgeoisie, and he projected this into his decorative interior design as many artists did then.

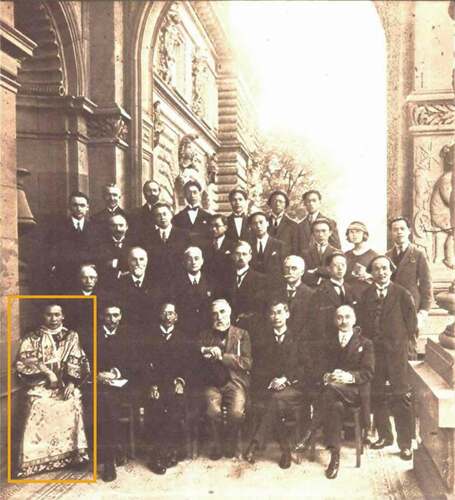

Liu profoundly applied this method into his design in France and perfectly expressed the significant aesthetic concept of unity stressed at that time to show his deep acknowledgement of decorative design as a vanguard artist. What Liu did to the Chinese pavilion is what an ensemblier does. He not only designed the graphic surface decoration of the interior but also participated in installing the furniture, rugs, porcelain, and other objects to produce a room unified by Chinese characteristics.Footnote17 This role was reinforced by Liu’s extreme behaviour at that time. At the opening ceremony of the 1924 Strasburg exposition, Liu dressed in an elaborately embroidered woman’s gown (Clunas Citation1989, 102), a Chinese traditional female costume as shown in a photograph of him with other participants (). Although there is no evidence documenting the installation of the 1924 Strasburg Exposition, as the same artist cohort participated in the Strasburg and Paris events, and the exhibits shared themes and exhibited objects, Liu’s interior design at the Strasburg Exposition likely used the same Chinese characteristics as his design at the Paris Exposition. A woman wearing a gown matched with a room’s interior design was considered to perfect the unity of the entire design at that time. For example, “Henry van de Velde and Hector Guimard followed William Morris by actually designing their wives’ costumes so that the very gesture would become an integral part of the environment” () (Selz and Constantine Citation1972, 8). Clunas (Citation1989, 102) mentioned that Liu’s behaviour was a way of executing exoticism; however, there is a strong possibility that Liu wore a woman’s costume to echo other designers’ gestures toward achieving this unity of design.

Figure 6. Van de Velde: Dress (C.1986) (Selz and Constantine Citation1972, 9).

Figure 7. Liu Jipiao wearing traditional Chinese female costume in the Strasburg Exposition in 1924. (Feng Citation1924, 40).

Revealing the influence of the Chinese aesthetic manifesto, the new art movements in Paris, and the rising prominence of decoration, Liu’s interior design became the representative practical design that answered the Chinese manifesto of blending Chinese tradition (mainly the arts of the past) with Western modern art. It also functioned as an experimental way of creating modern Chinese design in architecture as well as being an international artwork created by a Chinese artist under the methodology of modern French new arts. The ideology of pursuing the past, which was manifested in both new Western methodologies and the Chinese aesthetic manifesto, and the possibility of fulfilling both a social responsibility and his own subjectivity as a vanguard artist, prompted Liu to use the past and create tradition continuously in his design and drawing, not only when he was in Paris but also when he went back to China.

5. Practice in China: Designing the artistic architectural modernity

5.1. The building past and the artistic tradition

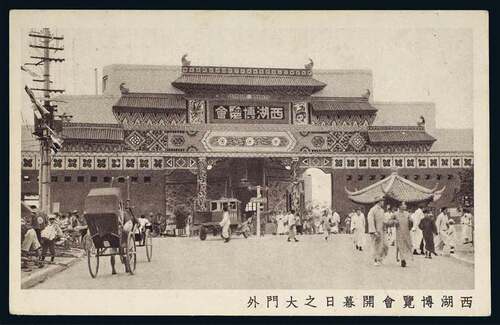

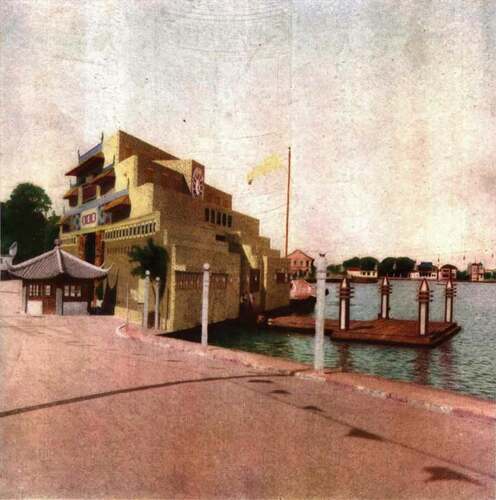

In 1929, Liu had completed the entrance building for the West Lake Exposition () in Hangzhou, east China. The building can be interpreted as being the most representative of his methodology of designing an artistic architecture. He continued to use the decorative method and designed an elaborate elevation for this building (). The elevation was created as a two-dimensional image fixed to the plain surface of the building. To make the image stand out, the other part of the building functioned as the backdrop (). It was constructed using a simple and geometrical box in light yellow. Apparently, the way Liu used and transformed motifs had slightly changed. He appears to have favoured the geometrical forms akin to Art Deco more than curvaceous shapes of Art Nouveau, a preference that mirrored global trends at that time.

Figure 8. The east elevation of the entrance building (Liu Citation1929b).

Figure 10. A photograph of the south-east view of the entrance building(Liu Citation1929d).

Besides a preference for the stylised and invariably symmetrical geometry of Art Deco, the design of this elevation reveals new references to buildings from China’s past and to Liu’s more mature thoughts on the kind of tradition that modern Chinese architects should draw on. The entrance building has an elaborate elevation designed in the image of a transformed traditional Chinese gateway. The Chinese gateway was the architectural genre that was historically used as the entrance into a main building compound, such as to the imperial tombs in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Such gateways were also used many times in modern expositions representing Chinese traditional architecture, including the1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in the United States, 1910’s South Sea Exposition, China’s First World’s Fair, and 1915’s Panama World Exposition. Liu’s design continued the tradition of using the Chinese gateway as an entrance, as the West Lake Exposition inherited the legacy of earlier commodity spectacles (Ercums Citation2014, 190). Nevertheless, Liu used the Chinese gateway in an exceptionally symbolic way. Other newly designed and constructed gateways of that time in most cases directly imitated real ancient buildings in three dimensions and were barely distinguishable from their ancient counterparts except in their construction methods and use of modern materials. However, Liu Jipiao totally rejected the traditional expressions of the gateway and creatively kept its symbolic function as an entrance while rejecting its physical form.

The volume of the traditional Chinese gateway was left out, and what remained was a transformed image of a gateway, which retained only the symbolic function of a gate. A traditional gate’s real function, as a path, was instead carried by the path that can through the whole building. The light-yellow colour and the simple geometric volume weakened the existence of the building behind this image as well. In one of the photos (), the building almost seems to disappear, leaving the image of the gate as the most significant visual element with its exquisite details and strong vivid colours. Liu, in one of his drawings of this elevation (), only drew the gateway without the volume of the building behind it, which reveals his emphasis on this symbolic image. While accommodating the necessary volume required by other utilities in a modern entrance building, the decorative image on the elevation creatively maintained the function of the traditional gateway in a modern symbolic way.

Furthermore, the image is not a direct projection of the elevation of a traditional Chinese gateway, as in an orthogonal drawing. Rather, it keeps the basic contour of the structure of the building and carries out the abstract transformation of the motifs from three dimensions to two dimensions using the decoration inside the contour. The only element that keeps its volume is the tiled roof projecting from the plain surface, while other components are reduced to abstract geometrical two-dimensional images.

The transformed motifs were inspired by two types of art found in ancient Chinese gateways. One was the architectural painting (建筑彩画jian zhu cai hua) on buildings, and the other was the most typical component of ancient Chinese buildings, the bracket (斗栱dou gong). Architectural painting was originally two-dimensional images painted on the surface of a building’s structure; however, it usually involved representational images or scenes, especially on components with a relatively large surface, such as on beams. Abstract images do exist but usually were used as a frame for a representational image or on components with a relatively small surface, such as each wooden piece used to construct a bracket. In Liu’s image of the gateway, he used only abstract and geometrical elements that could remind the audience of decorative motifs in ancient Chinese art. The transformed image of the bracket furthermore significantly illustrated the abstraction and symbolism of Liu’s transformed way of using ancient motifs. The brackets in ancient Chinese buildings were their most expressive components and functioned in both structural and decorative ways. Here, the bracket only kept its imaginative and decorative function, similar to all the other elements in this image. Liu transformed it into a series of inverted triangles stacked together. This transformation kept the kernel of the composition of the bracket in two dimensions. The inverted triangle symbolised the growing components of the bracket from the bottom to the top. The layers of the stacked triangles coincided with the brackets growing layer by layer. The transformed dou gong (or bracket) motifs () were not only used in this entrance, but also in the design of other buildings, such as in the façade of the Martyrs Shrine () and the interior design of the Corridor of the Central Party Headquarters (). In the latter two instances, the shape of the dou gong is transformed into a stepped shape. Liu realized the significance of the dou gong to ancient Chinese buildings.

Figure 11. Shape of dou gong and Liu’s two transformed dou gong motifs. (The left-hand images are reproduced from (Jie Citation1933, 178); the one on the upper right is the shape of the symbolic motif used in ; the one on the lower right is the shape of the symbolic motif used in ).

Figure 12. Façade of the Martyrs Shrine (Liu Citation1928b).

Figure 13. Corridor of the Central Party Headquarters (Liu Citation1929a).

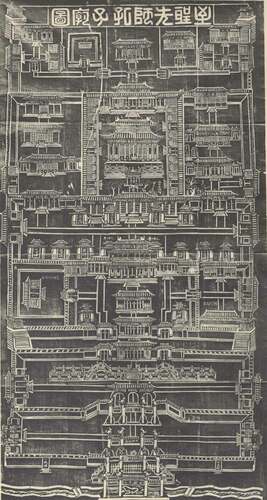

More interestingly, archival evidence has indicated that Liu may not simply have creatively designed the transformed images but also used them as references to the Chinese past. The evidence comes from the book Archaeological Mission in Northern China, published by Édouard Émmannuel Chavannes (1865–1918) in 1909 (Chavannes Citation1909). Chavannes’ books were the French sinology works in which Liu was most likely to have found references to Chinese ancient art. Chavannes published his research on Chinese ancient arts and religious art in two famous publications, the aforementioned book and Stone Carving in China at the Time of the Two Han Dynasties,Footnote18 published in 1893 (Chavannes Citation1893). Both books revealed many images of sculptures and stone inscriptions. The former book included an image of a stone rubbing documenting the engraving of a stone steal (). In this image, the brackets on the buildings are engraved using a triangular shape () similar to the one Liu used in his designs. This detail shows that Liu may not only have created modern motifs for the buildings he designed following the modern art trends that influenced him, but the abstract and modern forms of his motifs may also have been directly inspired by Chinese ancient art.

Figure 14. Image in (Chavannes Citation1909, PI.CCCXCVI. NO. 867).

5.2. The motivation: being a “Chinese” “architect”

Liu was dedicated to using the Chinese past to create a modern abstract and symbolic artistic tradition inspired by those he had imbibed from the world’s artistic trends, especially French decorative trends. Decoration became the most important methodology he used to express architectural modernity in his practice. This section investigates Liu’s motivation for promoting this methodology and artistic modernity from the perspective of the collective identity that he helped establish in the Chinese context.

Before this project of designing the entrance building for the West Lake Exposition in 1929, Liu had discussed “How should Chinese new architecture be designed” theoretically in the article How to Organize Chinese New ArchitectureFootnote19 (Liu Citation1927). He invoked the term “artistic architecture” (mei shu jian zhu) and stated that this genre of buildings should combine both science and art. Later, Liu (Citation1928a) mentioned three facets of architectural principles required to discuss and define architecture: function (zuo yong 作用), harmony (xie he 谐和), and style (zuo feng 作风).Footnote20 Liu (Citation1929c) argued that the architect who was a master in artistic architecture should have three abilities: science (ke xue gen di 科学根底), pattern and decoration (tu an Zhuang shi 圖案装饰), and style (zuo feng 作风).

Although Liu explicitly used decoration as his method for creating an artistic architecture, it only occupied a secondary position of the importance in this endeavour. Liu used the adjective “artistic” to describe the architecture he promoted, but he did not only or dramatically emphasise the artistic side of building. Instead, he always addressed the significance of science in modern architecture. He even addressed the sequence of the three abilities the architect needed to master: science first, pattern and decoration second, and lastly style. Why did Liu in his practice stress the method of decoration in such a distinctly dominant manner? This situation was related to an unspoken question.

Liu named the modern architecture he promoted “artistic architecture” not merely to answer the question of what modern architecture is. The question he did not ask directly, yet which was urgent in that period, was, “What is the modern architecture built by the modern architect?” The connotative definition of artistic architecture is the genre of buildings with characteristics that mark them as being designed by an architect. Liu (Citation1929c) pointed out that the counterpart of artistic architecture is engineering architecture, which yields purely utilitarian structures such as industrial buildings, military buildings, bridges, and so on. The separation of these two types of architecture was an urgent issue in Chinese architecture at that time. Chinese architectural theory had done little to address this separation before the appearance of Liu’s theory and practice. The primary requirement for construction in the gradually industrializing country was utility. Modern trained engineers who had mastered utility and structure more than beauty, participated in building the architectural landscape and had chronological and numerical advantages over architects. Those two factors helped create an environment in which modern Chinese architecture built by the newly emerged professional architects was barely discussed until the advent of Liu’s architectural theory. When Liu stepped in with his interest and ability in the arts, the need for distinguishing artistic architecture from engineering architecture became an urgent and central question.

In terms of how to design artistic architecture, the two factors of science and style (among Liu’s three architectural abilities) were not the main focuses of his own practice. Although science is the first and most significant factor in modern architecture, it is not a factor that could distinguish artistic architecture from engineering architecture. The third ability, style, without doubt, is specific to the architect rather than the engineer and is the necessary factor for building excellent artistic architecture. Liu mentioned the importance of style in almost all his articles that address architectural theories. Creating a modern Chinese architectural style rather than adopting Western architectural style or ancient Chinese style was Liu’s ultimate pursuit (Liu Citation1929c, 4). In his article The Past and Future of China Architecture (Liu Citation1930, 138), he used satirical language to clearly object to the three prevalent Chinese architectural styles of his time, which included one that completely imitated ancient Chinese buildings, one that completely imitated Western buildings, and one that brutally combined parts from both ancient Chinese and Western buildings.Footnote21 He raised the bar and challenged architects to harmoniously absorb inspiration from both Chinese and Western buildings to create a new style for modern Chinese architecture.

However, Liu seemed to have had no well-prepared or presupposed vision for the style of modern Chinese architecture. Instead, he said the only thing the architect can do is experimental design (Liu Citation1930, 138–139). Apart from science and the unforeseen style of the future (Liu Citation1930, 138),Footnote22 his practice ultimately drew on pattern and decoration, the latter being the second of his stated abilities. To Liu, the epitome of artistic architecture in those years was design and decoration, “tu an zhuang shi” (圖案装饰) in Chinese, which he used to create buildings that were representative works of architecture and experimental practice for future style.

The four Chinese characters “tu an zhuang shi” suggested Liu’s theoretical methodology of design and decoration. The term “zhuang shi” is the general translation for “decoration” in Chinese, while the term “tu an” carries three interrelated meanings: design, drawing, and decoration. “Tu an” are the two Chinese characters used to translate the English term “design” and were adopt from the characters in the Japanese translation of “design.” Then, in the 1920s and 1930s, “tu an” was commonly used to refer to both the new idea of design and the meaning “drawing,” which was comparable to the single character “tu.” One of the significant books on architectural drawing edited by Ge Shangxuan in 1920 was titled Jian Zhu Tu An (建筑圖案, Architectural Drawing). Several international competitions for the architectural design of national projects used “tu an” in their names, such as the competition for the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum in 1925. Parcy Ash’s 1931 book Theory of Architectural Design was translated as “Jian Zhu” (architecture) “Tu An” (design) “Fa” (theory) in Chinese in 1941. That “tu an” was used to represent the two meanings of drawing and design had both an English etymology and a Chinese one. “Tu” in Chinese has a long history of referring to drawing.

“Design” in English comes from the Italian term disegno, which means drawing (Hill Citation2005, 285). Catherine Wilkinson has argued that the concept of design is the symbol of the artist-architect in the Renaissance Italian tradition, writing “This tradition was founded on the belief (well rooted by the fifteenth century) that any artist could design a building since it was the conception of the work that mattered rather than the construction. This conviction derived from the custom of treating the three arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture as three branches of the same art of design, and it is probably very old in Tuscany” (Wilkinson Citation2000, 134). In English, by the seventeenth century, “design” was routinely used for the drawings of the architect. Adrian Forty argued, “When modernism appropriated ‘design’ in the 1930s, it was able to capitalize upon these already existing meanings. ‘Design’ fulfilled modernism’s need for a term that enabled one to distinguish between a work of architecture in its materiality, as an object of experience, and a work of architecture as the representation of an underlying ‘form’ or idea” (Forty Citation2000, 136). Design distinguished the materiality of architecture from its underlying form or the ideas of architects. “Tu” plus “an,” which means “pattern” in Chinese, became a new term used to refer to both drawing and design.

In addition to the meaning of “design” carried by the term “tu an,” Liu Jipiao also translated the English term “decoration” and the French term “decoratifs” into “tu an” in his article “Hope for Department of Decoration in the National Art Academy” (Liu Citation1928c). He directly referenced “decoration,” using the English word, after the term “tu an” in Chinese at the very beginning of the article. In his translation of “decoratifs” in the name of the Ecole Nationale Des Arts Decoratifs, he used “tu an.” In his explanation of the meaning of decoration, he stressed the artistic inclination in decoration without doubting that decoration also carries the meaning of design that distinguishes materiality from artistic ideas. This assimilation between decoration and design was generally acknowledged when decoration became a representative art trend at the vanguard of the progressive art movements in France.

Etymologically, Liu associated decoration with design in the term “tu an,” or the more complex “tu an zhuang shi.” In this way, the abstract concept of the design in his theory was directly associated with the more practical methodology of decoration using drawing as the intermedium. Meanwhile, this theoretical and practical association filled the gap in the newly established Chinese architectural landscape, which lacked systematic architectural theory and practice, and responded to the question of what modern Chinese architecture by Chinese architects should be.

6. Discussion

This article has uncovered a comprehensive picture of Liu Jipiao’s architectural modernity centering on the interaction between modernity and local traditions. It has analysed three aspects of his artistic modernity: the manifestation of the past he addressed and the tradition he invented (what), the method he used (how), and the motivation (why) for creating such a modernity ().

The three layers interacted together to form an artistic modernity, and the relationship between and among them witnessed a developmental Chinese artistic modernity rooted and matured in the Chinese context. The past Liu addressed and the tradition he invented were closely associated with the method he used. The international trend of emphasizing decoration that Liu had identified with the modern art ideology and the methodology of progressive French art trends determined how he incorporated the traditional into the modern. He preferred the motifs from the Han dynasty’s art in his design in France. However, he chose to use the past in his design in a modern way to create decoration by artistically transforming its motifs rather than producing them as strictly correct representations of the past. After returning to China, he started to use the past by referencing ancient buildings more in his design, showing his intention to value these buildings in his work as a professional architect in contrast to his use of the past in his work as an interior designer in France. He still had no strong intention to address the “pure” building past or the “coherent” building past of any particular dynasty. Rather, he preferred motifs from the past that could express abstract and symbolic characteristics, no matter whether they were from buildings or paintings, or were synchronous or asynchronous. He designed abstract and geometric motifs that symbolized the components of ancient buildings, rather than copying the appearance of these buildings. For example, on his entrance gate for the West Lake Exposition, a pair of motifs situated on both sides of the horizonal board with the characters xi hu bo lan hui (“the West Lake Exposition”) still kept a trace reference to Han art ().

Although the past Liu used slightly changed from his French period to his Chinese stage, he retained the use of decoration as his method for using the past to create the artistic tradition. This article has examined the reason why Liu’s preferred decoration as the coherent vanguard method for creating artistic architecture in China from the perspective of collective identity. As an architect, Liu urged solving the essential question of what kind of modern architecture a modern architect should do and provided a possible answer – the artistic architecture that valued design and decoration. Liu promoted the modern Chinese concept of design, used the method of decoration, and associated these two using drawing as an intermedium. Decoration and design became the vanguard method for distinguishing the Chinese architect from other professions, especially from the engineer, who built engineering architecture without enough consideration for “design.”

By looking at the development of Liu’s use of the past, his continued use of decoration as a method for its use, and his reasons for doing that, this research argues that China’s artistic modernity referenced its encounter with both its Western predecessor (French artistic modernity) and its local traditions. More importantly, the local receptional ground for Chinese architectural modernity in the entangled historical and cultural contexts of Liu’s day determined the formation and the development of this artistic modernity. This is the reason why decoraton could function as a progressive method and advanced the establishment of the identity of the Chinese architect and created an artistic modernity that was well accepted in 1920s China. Such contexts shaped this unique artistic modernity that showed different inclination to the Western modernism which adopted a different mode of representation by rejecting decoration under the influence of Adolf Loos’ treatise. From this critical perspective, a brutal comparison between Chinese modernity and its Western counterpart can be avoided.

7. Conclusion

This article has re-evaluated the everlasting relationship between tradition and modernity in the Chinese architectural landscape by adopting the perspective of multiple modernities. It has recovered the association between the “minor” figure Liu Jipiao (and his way of using the past) and the entangled historical contexts that inspired his work. In doing so, it has expanded the understanding of the relationship between the past, tradition, and Chinese architectural modernity, which previously has largely been constrained by a relatively narrow mainstream perspective. Over the past century, the existing historiography, carried out under a singular and heroic view of modernity, has been dominated by designs that attempted to incorporate the traditional into the modern by blending elements, forms, or orders directly inspired by ancient buildings. Research not only on significant individual projects (Steinhardt Citation2004; Lai Citation2007a, Citation2007b, Citation2014) but also on the general history of Chinese architecture (Su Citation1964; Fu Citation1993; Rowe and Kuan Citation2004; Wang Citation2009; Zhu Citation2009; Cody, Steinhardt, and Atkin Citation2011; Steinhardt Citation2011; Lai, Wu, and Xu Citation2016; Denison Citation2017) has focused on this way of using the past. The representative buildings of this style include the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum designed by Lu Yanzhi in 1925, the National Central Museum designed by Xu Jingzhi in 1935, and Great Mock Jian Zhen Memorial Hall designed by Liang Sicheng in 1963. Architects who helped to evolve or promote this style with their designs, such as Lu Yanzhi, Dong Dayou, Yang Tingbao, Liang Sicheng, etc., have become renowned architects in China.

In Liu’s artistic modernity, the past he used was a symbol of and a response to the present, a simulation of tradition rather than a representation of actual ancient buildings. This case helps show that the ways in which the collective intention among early Chinese architects to value tradition was actually fulfilled in history are much more complicated than previous scholarship has noted. The past occupied diverse positions in modern Chinese architectural design and traditions were incorporated into buildings in varied ways. Because this collective intention not only significantly shaped but also continues to shaped Chinese architectural modernity, this research, which expands multiple understandings of the past, tradition, and modernity, is of great value.

This research argues that the collective identity of being both “Chinese” and an “architect” can explain Liu’s motivation to create an artistic modernity, a motivation that was not only related to the desire for tradition but also to the methodology the architect had ever used. The perspective of collective identity has expanded the understanding of the motivation for Chinese architects’ desire for tradition, both from a national identity perspective but also, more critically, from a professional perspective, as “architects” distinguished from their other professional counterparts. Therefore, this perspective challenges the binary opposition that has built a boundary between Chinese architects and their Western counterparts, an opposition that has been overemphasized by scholars attempting to explain the desires for tradition and that has shaped the discourse on Chinese architects’ collective intention to honour the Chinese past. As an inspiration for Chinese architects and future architectural practice, this article posits that building Chinese modernity should not only focus on what architecture is “Chinese” architecture, but also on what architecture an “architect” should do.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lina Sun

Lina Sun is now a lecturer at Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture. This article is part of her PhD research at The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL.

Notes

1 This part of review on previous research of Liu Jipiao has been published in a relevant article by this author. (Sun Citation2021)

2 International exhibition of modern decorative and industrial arts.

3 The Chinese exhibition of ancient and modern art.

4 Copies of the two catalogues are in the National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, pressmark 5.D.55 and 5.C.19.

5 Li Feng’s article in 1924 documented this speech.

6 The French name of this organization is the Association des artistes chinois en France; the Chinese name is Huopusi Hui.

7 The French name of this organization is the Societe chinoise des Arts decoratifs a Paris; the Chinese name is Meishu Gongxue She.

8 This text is translated from French. The original French version is in the Catalogue of the Strasburg Exposition.

9 Separate images are from the catalogue of the Paris Exposition. The deductive plan is drawn by the author.

10 “The term Art Nouveau comes from S. Bing’s shop in Paris opened late in 1895, the corresponding German term Jugendstil from a journal which began to appear in 1896.” (Pevsner Citation1968, 43)

11 The term Art Deco derived from the title of the 1925 Paris exhibition, Exposition internationale des arts decoratifs et industriels modernes, which marked the rise of the Art Deco trend, although this title was not officially coined until the 1960s by Bevis Hillier.

12 This term was used in (Hillier Citation1968, 61).

It refers to the bubbles of air enclosed in seaweed. It can be understood as the bubble-shaped motif preferred by the decorative art.

13 Both of the names referring to these art movements were established later than the real prevalence of the movements themselves. No one can chronicle the exact date of the rise of Art Deco; there was an uneasy interregnum between the two movements. See (Hillier Citation1968, 22)

14 Image is download from https://asia.si.edu/object/F1904.61/. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

15 Maurice Denis (1870–1943) was a French painter, decorative artist, and writer who was an important figure in the transitional period between impressionism and modern art. (Selz and Constantine Citation1972, 29–31)

16 Sun Fuxi was very close to Liu Jipiao. In several of Liu’s writings published in journals at that time, Chun Tai (春苔), Fuxi’s written name showed up often in Liu’s social activities. In Liu’s family archive, Sun Fuxi’s portrait was kept, and it was sent to Liu after his exile to the United States.

17 S.T.F, Director of the Law, mentioned in the introduction to the catalogue, “Mr. Liou, the architect and decorator of the Chinese Section, in a relatively short time, with the collaboration of Mr. Tsen-Y-Lou, decorator artist, and Mr. Lin-Fon-Ming, President of the Section Jury, designed and produced this pretty and characteristic Chinese Gallery.” Introduction in the Catalogue. Text in English is translated from French by the author.

18 French title: La sculpture sur pierre en Chine au temps des deux dynasties Han.

19 How to Organize Chinese New Architecture (Liu Citation1927) was his first theoretical article. It became one of the foremost articles written by a professionally- trained architect and published in a mainstream periodical (Wang Citation2009, 232).

20 He included the English words as well as his Chinese interpretation in his article.

21 The original Chinese text is “第一式是古人遗下的几块烂布, 到底模仿也不是时代艺术。第二式是外国人的东西。模仿祖宗的遗迹虽然没有艺术价值可言, 算是可以挂住保存国粹的牌子。现在强把他人的肥股当作自己的脸孔, 未免太把古大文明的架子给弄糟了。第三式是不中不西的调和式, 仔细一看, 实在尚未达到调和的地步。一个西式房子硬戴上一个中式屋顶, 恰似一位欧洲新到中国的洋大人戴上一顶瓜皮小帽, 帽的尖端还有一颗黑呢缨子, 滑稽而且生硬。

22 The original Chinese text is “目前中国的调和派不能成派, 或者可作将来新作风萌芽的预兆。所以中国的建筑有将来而无现在。”

References

- Selz, P., and M. Constantine, eds. 1972. Art Nouveau: Art and Design at the Turn of the Century. New York: Museum of Modern art.

- Cody, J. W., N. S. Steinhardt, and T. Atkin, eds. 2011. Chinese Architecture and the Beaux-Arts. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Hobsbawm, E., and T. Ranger, eds. 2012. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lai, D., J. Wu, and S. Xu, eds. 2016. National State: Modernity and Nationality of Chinese City and Architecture (民族国家——中国城市和建筑的现代化与国家性). Beijing: Chinese Architecture Industial Publishing.

- Bozdogan, S., and R. Kasaba. 1997. Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Chaund, W. H. 1919. “Architectural Effort and Chinese Nationalism.” Shanghai. The Far Eastern Review 15: 533–537.

- Chavannes, E. 1893. La Sculpture Sur Pierre En Chine Au Temps Des Deux Dynasties Han. Paris: Ernest Leroux, Editeur.

- Chavannes, E. 1909. Mission Archeologique Dans La Chine Septentrionale. Paris: Ernest Leroux, Editeur, Rue Bonaparte.

- Clunas, C. 1989. “Chinese Art and Chinese Artists in France (1924-1925).” Arts asiatiques 44 (1): 100–106. doi:10.3406/arasi.1989.1262.

- Crinson, M. 1996. Empire Building: Orientalism and Victorian Architecture. London: Routledge.

- Crinson, M. 2003. Modern Architecture and the End of Empire. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Denison, E., and G. Y. Ren. 2012. “The Reluctant Architect: An Interview with Wang Shu of Amateur Architects Studio.” Architectural Design 82 (6): 122–129. doi:10.1002/ad.1506.

- Denison, E. 2017. Architecture and the Landscape of Modernity in China before 1949. New York: Routledge.

- Eisenstadt, S. N. 2000. “Multiple Modernities.” Daedalus 129: 1–29.

- Ercums, K. I. 2014 Exhibiting Modernity: National Art Exhibitions in China during the Early Republican Period, 1911-1937 . . TheUniversity of Chicago https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/exhibiting-modernity-national-art-exhibitions/docview/1524723117/se-2?accountid=14511.

- Fei, W. 2007. “Research on the Design of 1929 Westlake Exposition.” Master, Nanjing Art Academy.

- Fei, W. 2011. “Grafting “Decorative Art”, Blooming the Flower of “Fine Art Architecture”: Discussion on Architectural Design of Designer Liu Ji Piao.” Journal of Nanjing Arts Institute(Fine Arts & Design) 2 137–141.

- Fern, A. M. 1972. “Graphic Design.” In Art Nouveau: Art and Design at the Turn of the Century, P. Selz, and M. Constantine, edited by. New York: Museum of Modern art 18–45 .

- Forty, A. 2000. Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson London).

- Fu, Z. 1993. Chinese Classic-Style New Buildings: A Historical Research of the Official New Buildings of China in 20th Century. Taibei: Nantian Publisher.

- Gao, M. 2011. Total Modernity and the Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Chinese Art. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Gao, X., and N. Peng. 2017. “The Concept and Practice of “Fine Art Architecture” at the Hangzhou National Art College the Chinese Adaptation of French Modern Painting.” Time + Architecture 5: 142–149.

- Goss, J. 2014. French Art Deco. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Heynen, H. 1999. Architecture and Modernity: A Critique. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Hill, J. 2005. “Criticism by Design: Drawing, Wearing, Weathering.” The Journal of Architecture 10 (3): 285–293. doi:10.1080/13602360500162386.

- Hillier, B. 1968. Art Deco of the 20s and 30s. London: Herbert: Rev.

- Jie, L. 1933. Ying Zao Fa Shi (3). Beijing: TheCommercial Press.

- Kao, M. M. 1972. China’s Response to the West in Art, 1898-1937. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Palo Alto.

- Lai, D. 2007a. Chinese Modern: Sun Yat -sen’s Mausoleum as a Crucible for Defining Modern Chinese Architecture. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Lai, D. 2007b. “Designing a Ideal Chinese-style Modern Building: Liang Sicheng’s Architectural History Writing and Liao Song Style of Nanjing National Central Museum Design (设计一座理想的中国风格的现代建设——梁思成中国建筑史叙述与南京国立中央博物院辽宋风格设计再思).” In Studies in Modern Chinese Architectural History. Beijing: Qinghua University Press 331–362 .

- Lai, D. 2012. “Wang Shu and the Revival and Development of Chinese Literati Architectural Tradition (中国文人建筑传统现代复兴与发展之路上的王澍).” Architectural Journal 5 1–5 .

- Lai, D. 2014. “Idealizing a Chinese Style: Rethinking Early Writings on Chinese Architecture and the Design of the National Central Museum in Nanjing.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 73 (1): 61–90. doi:10.1525/jsah.2014.73.1.61.

- Lejeune, J.-F., and M. Sabatino. 2010. Modern Architecture and the Mediterranean: Vernacular Dialogues and Contested Identities. London: Routledge.

- Li, F. 1924. “First Chinese art Exhibition of Chinese in Europe. Strasbourg Exhibition (旅欧华人第一次举行中国美术展览大会之盛况).” Eastern Miscellany 21: 30–36; 40–43.

- Li, H. 2020. “Modernity: A Perspective to the History of Architectural Knowledge (现代性——一个建筑知识史的视野).” The Architect 1: 103–109.

- Liu, J. 1927. “How to Organize Chinese New Architecture (中国新建筑应如何组织).” Eastern Miscellany 24: 81–84.

- Liu, J. 1928a. “Architectural Theories (美术原理).” Contribution: The Special Number for Liou Kapaul 3 6 : 27–35.

- Liu, J. 1928b. “Façade of the Martyrs Shrine (烈士祠).” Contribution: The Special Number for Liou Kapaul 3 6 .

- Liu, J. 1928c. “Modern: Hope for Department of Decoration, National Institute of the Arts (摩登:对于国立艺术院图案系的希望).” Special Issue of Central Daily News 1: 71–72.

- Liu, J. 1929a. “Corridor of Central Party Headquarters (中央党部回廊图).” China Traveler: The Special Number for Liou Kapaul Esq 3 4 .

- Liu, J. 1929b. “The Entrance Gate of the West Lake Exposition - Frontal Elevation in Chinese Palace Style (西湖博览会大门口用宫殿式正面图).” China Traveler: The Special Number for Liou Kapaul Esq 3 4 .

- Liu, J. 1929c. “Fine Arts Architecture and Engineering (美术建筑与工程).” China Traveler: The Special Number for Liou Kapaul Esq 3 4 .

- Liu, J. 1929d. “The Main Entrance of West Lake Exposition (西湖博览会大门之壮观).” China Traveler: West Lake Exposition Number 3 7 : cover.

- Liu, J. 1930. “The Past and Future of China Architecture (中国美术建筑之过去与未来).” Eastern Miscellany 27: 133–139.

- Lu, D. 2006. Remaking Chinese Urban Form: Modernity, Scarcity and Space, 1949-2005. London: Routledge.

- Lu, D. 2007a. “Architecture and Global Imaginations in China.” The Journal of Architecture 12 (2): 123–145. doi:10.1080/13602360701363411.

- Lu, D. 2007b. “Third World Modernism.” Journal of Architectural Education 60 (3): 40–48. doi:10.1111/j.1531-314X.2007.00094.x.

- Lu, D. 2010a. “Architecture, Modernity, and Knowledge.” Fabrications 19 (2): 144–161. doi:10.1080/10331867.2010.10539662.

- Lu, D. 2010b. Third World Modernism: Architecture, Development and Identity. London: Routledge.

- Lu, Y. 2018. “Modern Architecture: Image and Imagination in the Mass Media of Early Modern Shanghai (现代建筑的图像传播与中国想象——以近代上海的大众媒体为例).” Architectural Journal (建筑学报) 3: 18–24.

- Melucci, A. 1996. Challenging Codes: Collective Action in the Information Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pevsner, N. 1968. The Sources of Modern Architecture and Design (London: Thames and Hudson).

- Rowe, P. G., and S. Kuan. 2004. Architectural Encounters with Essence and Form in Modern China. Cambridge: Mit Press.

- Sabatino, M. 2010. Pride in Modesty: Modernist Architecture and the Vernacular Tradition in Italy. London: University of Toronto Press.

- Samman, M., and Y. Saifi. 2021. “Adapting Modernity: Designing with Modern Architecture in East Jerusalem, 1948–1967ʹ.” Journal of Design History 34 (2): 129–148. doi:10.1093/jdh/epab006.

- Shils, E. 1971. “Tradition.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 13 (2): 122–159. doi:10.1017/S0010417500006186.

- Steinhardt, N. S. 2004. “The Tang Architectural Icon and the Politics of Chinese Architectural History.” The Art Bulletin 86 (2): 228–254. doi:10.2307/3177416.

- Steinhardt, N. S. 2011. “Chinese Architecture on the Eve of the Beaux-Arts.” In Chinese Architecture and the Beaux-Arts, edited by J. W. Cody, N. S. Steinhardt, and T. Atkin. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press 3–22 .

- Su, G.-D. 1964. Chinese Architecture, past and Contemporary. Hongkong: Sin Poh Amalgamated (HK).

- Sullivan, M. 1996. Art and Artists of Twentieth-Century China. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Sun, F. 1928. “The Ripples on the Water Heads for Infinity (水面上的园痕向着无穷扩大).” Contribution: The Special Number for Liou Kapaul (贡献:刘既漂建筑专号) 3: 1–5.

- Sun, L. 2021. “Drawing the Identity of Architect: Liu Jipiao as an Artistic Architect in the Late 1920s China.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 10 (3): 584–597. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2021.03.004.

- Wang, Y. 2009. Exploring the Chinese Style: Modern Chinese Architecture’s Thinking Pattern and Design Practice, 1900 – 1937 (探求一种“中国式样”——近代中国建筑中民族风格的思维定式与设计实践1900-1937). Shanghai: Tongji University.

- Weng, T. 2014. “Study on Design Works and Theoretical Thinking of Liu Jipiao (刘既漂设计思想及其作品研究).” Master, Tongji University.

- Wilkinson, C. 2000. “The New Professionalism in the Renaissance.” In The Architect: Chapters in the History of the Profession, edited by S. Kostof. Oakland: University of California Press 124–160 .

- Wong, J. 2013. “The Chinese Art Deco Architect of the 1925 Paris Expo’-My Grandfather.” The Newsletter section The Studt.

- Xing, P. 2018. “Involvement of Arts and Identity of Architects in China Early Architecture Exhibition (中国早期建筑展览会中艺术的介入与建筑师的身份认同).” Decoration (装饰) 2: 80–83.

- Xu, S. 2010. The Born of Chinese Modern Architecture (近代中国建筑学的诞生). Tianjin: Tianjin University Press.

- Zheng, H. 2013. “Blending China and West to Create Chinese New Architecture:Liou KiPaul’s ‘Art Architecture’ and Its Interpretation (调和中西以创中国新建筑之风——刘既漂的“美术建筑”之路及其解读).” South Architecture 6 77–85.

- Zhu, J. 2009. Architecture of Modern China: A Historical Critique. London: Routledge.