ABSTRACT

Taking the localization of Mitchell’s Building Construction in Shanghai as a case study and a starting point and discussing British polytechnics, construction teaching and construction textbooks, this paper examines the transmission of technical knowledge to Chinese builders in Modern Shanghai. The paper provides the first systematic examination of Mitchell’s professional biography and the first review of the editions of his Building Construction textbooks. The paper shows that Mitchell’s textbooks built on rapidly evolving scientific knowledge in building technology in Britain, and how their success was attributed to the time, his construction pedagogy, their constant updates and their remarkable contribution to the building industry. A comparative analysis between Mitchell’s books and Du’s technical Dictionary and Yingzao Xue from an educational perspective, reveals Du’s insights into Mitchell’s powerful pedagogical tools of construction textbook writing, bridging different construction cultures – terminology learning, visual learning, and adaptive knowledge learning. Drawing from one of the most successful models of construction textbooks, Du’s contribution was to create a wholly new work – a distinct mixture that filled in the gaps and created a new discourse of Chinese Building Construction for the new global-local building industry in Shanghai

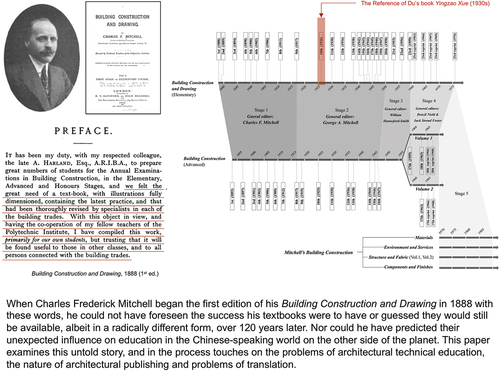

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

1.1. Research background

The Chinese builders not only played a crucial role in the construction of British Settlement in Shanghai since the mid-19th century; they also turned their city into the most prosperous building market in Republican China and the most modern city of China today. Those seemingly “most conservative” Chinese craftsmen, who kept up two thousand years of construction traditions, were the same builders who would transform the city completely. How did outside influences affect Chinese practice and to what extent did it change the way Westerners transformed Shanghai?

Current scholarship of modern Chinese architecture has paid considerable attention to the transformation in the physical fabric of buildings and the contributions of Western and Chinese architects and engineers, while the significant part that the Chinese builders played has been largely left unexplored. This research explores one essential but neglected aspect of the Modernization process of the building industry: modern construction education. It addresses how the Chinese builders adapted to the new building methods under Western influence in Shanghai.

Mitchell’s Building Construction and its impact in Shanghai make a good case study and a starting point of exploration. Due to the rich Sino-British relations of that period and the success of the British polytechnics and English building construction textbooks, the British experience had a significant influence on the formation of the discipline and on the content of early building construction textbooks in China. Therefore, the authors believe that a comparative historical study of the relationship between British and Chinese Modern construction education could fill the historiographic gap and make contributions to the fields of both British and Chinese construction history.

1.2. Literature review

The foundation of this research area was laid in the groundbreaking Chinese architectural history research on the Modernization of Chinese architecture by Wu (Citation1997), Sha (Citation2001), Li (Citation2004), Lai (Citation2007), and Xu (Citation2010), in which they have addressed foreign influences on modern Chinese architectural education from a variety of angles, and all agreed on the general Westernization of the building practice and architectural education. Cody (Citation1997)’s “Teaching Construction in China, 1926–1937” was the first attempt to examine English-speaking construction education in China, but his paper concentrated only on two educators – the American missionary engineer Sam Dean and the British carpenter Alfred Emms – and on a relatively late period.

Within the field of construction history, the earliest discussion of construction knowledge transfer emerged in the studies focusing on early Chinese building books and Western-influenced construction methods. Coomans (Citation2014, Citation2016) investigated the transmission of Western techniques to Chinese workers in church construction in Northern China, based on a detailed examination of a rare French building handbook in 1926. A previous study by the authors of this paper (2015) demonstrated for the first time how the earliest Chinese Building Construction textbook Zhang (Citation1910) was compiled based on the 19th-century English architect Joseph Gwilt’s An Encyclopedia of Architecture (9th edition, Citation1888), showing that the implied process of writing the Chinese books, to some extent, reflects the fact that Modern Chinese buildings are the works of deconstructed and re-collaged Western knowledge of architecture into a new self-consistent whole. Shu (Citation2018) focused on Shanghai brickwork and emphasized the significant role that textbooks, handbooks and manuals had played as “a new, and powerful means for the dissemination of technical knowledge in modern China”.

The academic interest in Du’s (Citation1935–1937) – another influential Chinese Building Construction book in the early 20th century – has been in the air for some time. Zhao (Citation2010)’s Chinese paper was the first attempt to examine the building methods and technical representation in Yingzao Xue and found a general British influence in this book. Based on an extensive search of English building construction books published between 1840 and 1940, the authors of this paper revealed for the first time that Yingzao Xue is largely drawn from the 10th edition of Mitchell’s Building Construction and Drawing published in 1926 (Pan and Campbell Citation2015). Although both Shu (Citation2018) and Ye and Fivet (Citation2018) touched on the biography of Yangeng Du, his English-Chinese, Chinese-English Architectural Dictionary, and early industrial schools in Shanghai, Shu (Citation2018) provided a more detailed comparison between Shanghai brickwork and Mitchell’s texts and illustrations. However, none of the existing studies investigated the writing of Yingzao Xue and its English originals from an educational perspective.

Although each of the above studies has made its respective contribution to current scholarship on Western construction knowledge transfer in China, a synthesized, panoramic understanding of the relationship between British and Chinese Modern construction education has not been provided in the prior literature. More specifically, following questions still need to be addressed:

In England, how did Modern technical education in Building Construction develop in its particular social, economic and technical context?

In China, how did this new mode of construction education integrate into the local community of Shanghai?

At the intersection of British influence and local practice, to what extent does the localization of Mitchell’s Building Construction in Shanghai explain or demonstrate the more theoretical question of “hybridity”?

1.3. Methodology

To tackle the research questions raised, this paper follows three lines of investigation. The first line analyses Mitchell’s Building Construction textbooks and their origin in vocational evening classes provided as Polytechnic education in London. The second line provides a historical survey of British-inspired Polytechnic education for building construction in Shanghai in 1870–1937. Finally, the convergence of the first two lines of investigation leads to an in-depth comparative analysis between Mitchell’s Building Construction books and Du’s technical dictionary and construction textbook Yingzao Xue. Collectively, on the basis of Mitchell’s case as a starting point of exploration, and through a discussion of British polytechnics, construction teaching and construction textbooks, this paper examines the British-Chinese transmission of technical knowledge to Chinese builders in Modern Shanghai.

Historical methods have been mainly used for this study. In particular, this study focuses on the examination and representation of historical data, paying attention to the evidence for historical processes. Overall, this paper adopts a chronological and comparative narrative to represent this history. In this process, two major source criticism methods – “Internal criticism” and “external criticism” – were employed to gain a deeper understanding of “by whom, for whom, when, why, and how” these English and Chinese building construction textbooks were produced. This paper also engages in the construction and explanation of these historical processes, paying attention to meaning and theoretical interpretation. In this process, Homi K. Bhabha’s post-colonial theory is employed in the discussion to balance different perspectives and prevent biased interpretations.

While the breadth of the topic covered herein inherently prevents its exhaustive treatment within the space of a single study, the present research provides fresh insights into the relationship between British and Chinese Modern construction education. However, much remains to be researched. Future projects following this study might include: a compilation of a bibliographical index for Chinese building construction textbooks in China; further case studies on early pioneers of construction teaching in Shanghai; and further studies on the training of particular building methods in Shanghai.

1.4. Historical sources

Literature surveys, archival surveys, edition surveys, and architectural surveys are the primary means adopted to gather historical data for this study. Specifically, nine types of primary sources were used: 1) Mitchell’s family records, preserved in the UK government archives; 2) the archives of Regent Street Polytechnic, London; 3) documentary records of early industrial or vocational schools in Shanghai; 4) Shanghai Society of Engineers and Architects (SSEA) Proceedings, preserved in the Institution of Civil Engineers, London; 5) English books on building construction, published in the UK between 1840 and 1940; 6) Chinese modern manuals, textbooks and research articles on building construction published in China between 1840–1940; 7) early English building periodicals published in England before 1940; 8) early building periodicals and magazines published in China before 1949; 9) surviving Shanghai buildings from 1840–1940. This paper concentrates on primary sources, backed up by site visits to Shanghai buildings.

The archival survey involved the first systematic examination of Mitchell’s family history and professional trajectory. Access to government data in the form of birth certificates, census records, marriage certificates, and death certificates now available online has enabled this study to be undertaken in a way that was not possible before. This data has been essential and used extensively in this paper, providing us with a much clearer understanding of Mitchell’s life and background than would otherwise have been possible. The edition survey of Mitchell’s Building Construction books is grounded in an exhaustive search and cross-verification of the bibliographic records in T.M. Russell’s bibliographic index on building books (Citation1982), the Main Catalogue of the British Library, the iDiscovery of the Cambridge University Library, WorldCat, and OPAC. The edition study is based on a thorough examination of each of the different editions and was conducted mainly in the Rare Books Room of the Cambridge University Library.

2. British polytechnics and mitchell’s building construction

The contribution of Mitchell to British construction history is significant, but surprisingly his biography (Glew et al. Citation2013; Pan Citation2016; Shu Citation2018; Pan Citation2020) has not been looked at in detail. The first line of investigation sets out to provide the first proper biography of Mitchell and how his Building Construction textbooks came about and developed. The main sources comprise UK government archives, archives of Regent Street Polytechnic, and a thorough survey of different editions of Mitchell’s Building Construction textbooks.

2.1. Evening classes

In order to understand Mitchell’s engagement in evening classes and make sense of what the subject of his book “Building Construction” was, it is necessary to first distinguish the three sibling disciplines: “Architecture”, “Engineering”, and “Construction”. Architecture was generally concerned with the aesthetic aspects of building design and its study was through books on architectural composition, the orders and architectural history. Engineering involved the calculation of structures and an understanding of the mechanical principles necessary for ensuring that the buildings stood up and that their services operated properly. A knowledge of construction was essential for civil engineers, architects, and those entering the building trades.

Architects, engineers, and builders traditionally learned their trades through pupilage or apprenticeship in Britain and China. In the last two decades of the 19th century, the Polytechnic Movement across Britain witnessed the transition of construction teaching from an apprenticeship system to a modern technical education with lectures, textbooks, and laboratories. In the 1880s there were no full-time architecture courses in Britain and evening courses were the only formal option. In the late 19th century pupilage was still the standard way to train as an architect in Britain, supplemented by evening classes where they were available (Saint Citation2007).

The importance of these evening classes is too easily overlooked. They provided working men from all walks of life with the chance to better themselves, meanwhile allowing many architects and engineers who toiled in offices during the day to acquire their technical knowledge in the evenings. Mechanics Institutes had appeared in the late 18th century in cities across Britain to provide such classes (Hennock Citation1990; West and Mays Citation2007). In London, the foundation of the Regent Street Polytechnic in 1882 increased their provision.

It is in this context that the discipline of “Building Construction” was developed and formalized in Britain. This discipline mainly dealt with the choice of materials, the principles in making different building components, the tools and working process, and the aspects of comfort and hygienic living. Mitchell’s Building Construction textbooks, written specifically for the Regent Street Polytechnic’s courses, were one of the most successful series of textbooks on building construction ever published in Britain.

2.2. Charles Frederick Mitchell

Charles Frederick Mitchell (Citation1859–1916) () joined the Polytechnic teaching staff in 1882. He was born in London in 1859, the fifth son of Alfred and Elizabeth Mitchell. His father Alfred Mitchell (1825–1890) was a Metropolitan police officer whose only claim to fame was that he had been charged with Prince Albert’s security until the latter’s death in 1861. He had ten children: eight sons and two daughters ().

Little is known about Charles’s early life and education. At the age of 21, he was still living with his parents and was working as a carpenter, as reported in the 1881 census.Footnote1 The Polytechnic listed him as such when he joined the staff in 1882, but in 1890 he joined the Society of Architects and in the 1891 census he described himself as an architect.

In 1885 he married Alice Louise Wheeler, daughter of Thomas Wheeler (deceased) in St John the Evangelist, Fitzroy SquareFootnote2 and she bore him a son, Harold (1886–1950),Footnote3 but Alice died in 1892 at the age of 31,Footnote4 leaving Charles to look after the child alone. Four years later, in 1896, he married again. His new wife was the 27-year-old Constance Emily Alice Cox, daughter of Charles Cox, who worked for the Inland Revenue.Footnote5 Together they had a daughter, Constance, in 1899 and the family lived together in a number of addresses in central London, leading what appeared to be a comfortable middle-class existence.Footnote6

A surprising number of Charles’s family members were involved in the Polytechnic. The key figure was his elder brother Robert Mitchell (1855–1933) (Wood Citation1934). Robert attended Quentin Hogg’s Young Men’s Christian Institute and became its Secretary during the period that Hogg purchased the Royal Polytechnic Institution in Regent Street and re-founded it as the Regent Street Polytechnic. Robert Mitchell was actively involved in its formation (Glew et al. Citation2013). The Polytechnic aimed to provide the lower middle classes with technical education and stimulating evening classes for personal betterment and recreation. Robert became its Director of Education in 1891 and held that post until he retired in 1922, when he was made Vice President and a Governor. For his services to the Red Cross and Ministry of Pensions in the First World War he carried the rank of Major and was given a CBE (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire). Robert was instrumental in setting up the technical classes in the Polytechnic.

There can be little doubt that it was due to his elder brother’s involvement that Charles was recruited to teach. He was initially appointed in 1882 as an assistant instructor under A. Harland on the Building Construction (Elementary, Advanced, and Honors) Courses, and under H. J. Spooner on Practical Plane & Solid Geometry (Elementary, Advanced, and Honors).Footnote7 He was later to become a registered teacher of the Science and Art Department and City and Guilds of London Institute. He was obviously an extremely gifted teacher. Over the years the number of courses he was involved in was impressive. The Home Tidings and The Polytechnic MagazineFootnote8 listed seventeen of them covering a wide variety of subjects ranging from hydraulics and mechanics, through graphic statics to surveying and building construction. His broad interests in construction included drainage engineering and water supply, which led to him becoming an associate of the Sanitary Institute and eventually the first Head of the Polytechnic’s Technical School.

Charles was not the only member of the school whom Robert managed to persuade to teach. Their younger brother George Arthur Mitchell (1868–1952) was also an architect and he joined the architectural staff of the Polytechnic in 1890. In 1916, he took over as Head of the Architecture School. Their younger sister Matilda Maria Mitchell (1861-c.1947), who never married, was the founder of the Polytechnic School of Domestic Economy and a teacher of cookery (Glew et al. Citation2013: xi). The family tradition was continued with subsequent generations attending and teaching in the Polytechnic.

2.3. Books and writing

Although many textbooks on building construction had been written for the French Academy of Architecture centuries before, Britain lacked full-time architecture courses and comparatively few such books had been written in Britain. There were good books available on all the various building crafts – on carpentry, on bricklaying, on plastering, and on stonework – but they were not aimed specifically at students and were not written as classroom aids. The last two decades of the 19th century were the turning point. As evening classes opened up, their teachers supplemented their incomes by producing textbooks to support their courses. What was required were concise textbooks aimed at preparing students for the examinations and this is precisely what Mitchell produced. He completed his Building Construction and Drawing in 1887, which was first published in 1888 (Mitchell, Citation1888).

Mitchell was not the first to write such textbooks. He had been beaten to it by Ellis Davidson, Science and Art Lecturer of the City of London Middle-Class Schools, who had produced his The Elements of Building Construction and Architectural Drawing in 1869. That had been closely followed by the publishers Rivingtons, who had produced their Notes on Building Construction arranged to meet the requirements of the syllabus of the Science and Art Department of the Committee of Council on Education in 1875. Edward J. Burrell, Second Master of the People’s Palace Technical Schools in London, produced his Elementary Building Construction and Drawing, which appeared in 1889, shortly after Mitchell’s textbook. Many similar volumes followed. While the aforementioned textbooks went to many editions, none matched the success of Mitchell’s textbooks, which were simply extraordinary. By 1902, Mitchell’s textbooks had been not only recommended by the Examining Bodies in Britain but also by the International Examiners of the Y.M.C.A. of New York. In the 1920s, they even had the unique record of being the best seller in connection with fiction and other books.Footnote9

Mitchell’s first volume covered the Elementary level. In 1894, following its huge success and positive reviews,Footnote10 he wrote a second volume covering the Advanced level and Honors level, this time assisted by his younger brother George A. Mitchell. These two volumes became collectively known as the Mitchell’s Building Construction series (Elementary, Advanced, and Honors). Both volumes were continually updated by the Mitchells with over 20 editions for more than 70 years. () Mitchell’s Building Construction series became not only the standard textbooks for many years in the Regent Street Polytechnic in London, but also the most popular series of textbooks on building construction ever published in Britain.

In the early years, Charles enjoyed the large number of textbooks sold and diligently revised his volumes to keep them up to date, new editions being produced every 2–3 years. This undoubtedly contributed to their success. However, the real reason was simply that they were the best volumes on the market, providing students with everything they needed to pass their examinations. The key was the illustrations on which all construction books were heavily dependent. These were time-consuming and costly to produce and update. There were 1000 illustrations in the Elementary book and 600 in the Advanced one. The cost of illustrations encouraged publishers to stick to a well-tried format and to reprint volumes rather than commission new ones. However, keeping these volumes up to date meant adding new drawings and redrawing existing ones, which required substantial time and effort, hence Charles calling on the help of his younger brother to create the second volume.

Charles’s younger brother, George A. Mitchell, had joined the full-time Polytechnic staff in 1892 (Holbrow Citation1933; Glew et al. Citation2013). He would also become the official architect of the Polytechnic. He was in charge of the extensive rebuilding scheme in 1910 and other projects, including the Polytechnic Boat-house and the Ladies’ Pavilion. During WWI, he was appointed as Commanding Officer (1914–1919) of the Polytechnic Cadet Corps, officially the 1st Cadet Battalion, 12th City of London Regiment, which was the strongest school corps in the London area.

Charles and George seemed to have worked well together. In 1904 they produced Brickwork and Masonry: A Practical Text Book for Students, and those engaged in the Design and Execution of Structures in Brick and Stone, which included nearly 600 illustrations. Although they revised it for a second edition in 1908, it was not reprinted after that.

There seems little doubt that Charles would have continued to update his books himself but in 1916 he was taken into hospital and died.Footnote11 After the unexpected death of his elder brother, George took over as Head of the Day and Evening Departments of the School of Architecture and held these posts until his retirement in 1933. He also took over the revision of Charles’s textbooks. In 1926 he engaged his son Alexander Millar Mitchell (1900–1946)Footnote12 and A.E. Holbrow, another lecturer at the Polytechnic. When his son died, George continued to update the work until finally in 1950 William Hanneford-Smith (1878–1954) – an engineer by training and one of the directors of Batsford, who were the book’s publishers – took over. Although Hanneford-Smith had brought radical revisions to the new editions since 1950, George A. Mitchell’s name was retained as the first in the author list of the books.

The Elementary and Advanced books were revised in 1959 by Denzil Neild (Elementary and Advanced Vol. 1) and Jack Stroud Foster (Advanced Vol. 2) and the volumes were completely reformatted since 1970 to become the Mitchell’s Building Construction Series. The volumes in this Series were larger in format but slimmer and the contents were redistributed into different books: Jack Stroud Foster produced two volumes on structure; Peter Burberry provided one on services; and Alan Everett produced volumes on materials and on components and finishes. The Series, much revised, retained the name “Mitchell’s” and is still in print today.

The Mitchell brothers’ success led to their name being indelibly associated with textbooks on building construction. They likely never imagined that their volumes would live on. However, more surprising was the effect that their books had thousands of miles away, where their original volumes became the source for teaching building construction all over the world. This can be seen by examining one particular and peculiar example: the reception of Mitchell’s textbooks in China.

In summary, this line of investigation has shown that in the late 19th century, promoted by the Polytechnic Movement across Britain and taught largely in evening classes, “Building Construction” was gradually formalized into a discipline, becoming a central part in the practical education of architects and engineers and practical men in Britain. Aimed at students and intended as classroom aids, Mitchell’s Building Construction textbooks were first published in 1888 and continuously updated for over a century, becoming one of the most successful series of textbooks on building construction ever published in Britain. Even after the decease of the Mitchell brothers, Mitchell’s name was retained in the book title. In this regard, “Mitchell” is no longer an individual but the synonym of a tradition of British construction textbook writing. Building on advanced scientific knowledge in building technology that evolved rapidly in Britain, the success of Mitchell’s textbooks was attributed to Mitchell’s construction pedagogy, and the constant updates of the textbooks and their remarkable contribution to science popularization in the building industry. Undeniably, however, it is Mitchell’s special era and the changing nature of construction teaching (the transition from apprenticeship to technical education), not only in Britain but also in East Asian countries like China that had completely different construction cultures, that made the impact of Mitchell’s Building Construction textbooks reach new heights.

3. Integration of polytechnic education in Shanghai

The second line of investigation traces how the new mode of construction education – British-inspired Polytechnic education – was integrated into the local community of Shanghai. In particular, it examines the development of British-inspired polytechnic education in Shanghai with two major examples in different decades: the Chinese Polytechnic Institution and Reading Room (1874–1914) and the Henry Lester Institute of Technical Education (1934–1944). The investigation draws from both primary and secondary sources in Chinese and English, including documentary records of early industrial or vocational schools in Shanghai, alumni memoirs, and Shanghai Society of Engineers and Architects (SSEA) Proceedings.

3.1. The first books for expatriates wanting to build

To understand why Mitchell’s textbooks were found in China at all, we need to begin from the developments occurring in China from the middle of the 19th century, when there was no concept of the discipline of “Building Construction”. For the sake of illustration, in 1851, the English Architect Edward Ashworth (1814–1896) wrote an article on the building of a new Western-style house in Hong Kong (1844–45), in which he described the differences encountered between the English expatriates with their scientific understanding of construction and the local craftsmen working in the Chinese building tradition (Ashworth Citation1851; Pan Citation2014). Ashworth’s analysis described the process of building in Western terms using concepts such as building specification, house plan, foundations, brick walls, verandahs, columns, and fireplaces, each reflecting his structured knowledge of Building Construction. His criticisms of the details of Chinese work under his supervision were also based on comparisons with the contemporary building construction in England that he continually used as a reference. He was as mystified by the Chinese ways of working as the Chinese builders were with his attempts to describe what he wanted.

The knowledge divide between Western architects working in China and local builders, as exemplified by Ashworth’s account, reflects the general challenge that Western architects faced when supervising building projects in China. Further, many Westerners supervising such projects in 19th-century China were often not architects or engineers, given the general lack of such professionals in East Asia at the time. This determined a clear demand for practical books that the colonists could use to train the local builders as well as the Western supervisors in building construction.

A special type of pocket manuals appeared to meet this demand, designed to instruct the uninitiated on how to build. Such manuals included the English architect Robert Scott Burn’s The Colonist’s and Emigrant’s Handbook of the Mechanical Arts, first published in 1854 (Burn Citation1854, Citation1860), and the much later French Handbook published by Jesuit missionaries in Xianxian, entitled Le missionaire constructeur, conseils-plans (The Missionary-Builder: Advice-Plans), designed to instruct French-speaking missionaries in Northern China to build church buildings (Coomans Citation2014; Coomans et al. Citation2016). Importantly, these manuals were intended for self-study, i.e., they were not generally used in formal educational settings.

Western practitioners often relied on the books they brought with them from home or purchased from travelers. The Hungarian architect László Edward Hudec (1893–1958) left us an account of the architectural books he purchased on his trips between Shanghai and Europe (Poncellini et al. Citation2013). The availability of these Western works is shown by the number of original copies and local reprints that can still be found in libraries or secondhand bookstores in China today.

3.2. Chinese Polytechnic Institution and Reading Room

The demand for training in building construction in 19th-century China also led to the creation of evening classes. In Shanghai, George Strachan (1821–1899), a Scottish architect, set up the first construction school to help local building workers from Ningbo when he practiced in Shanghai from 1849 to 1854 (Shu Citation2018). All such courses run by expatriates were inevitably constrained by their lengths of stay.

The Chinese Polytechnic Institution and Reading Room [格致书院] was more long-lasting. Initiated by John Fryer [傅兰雅] (1839–1928), it was founded in the International Settlement in Shanghai in 1874 as a joint venture between the British Consulate and the Taotai of Shanghai and was run by a Committee consisting of both expatriate and Chinese members (Biggerstaff Citation1956). The lectures were held in Chinese, consistent with the purpose of the Institute “to bring the Sciences, Arts, and Manufactures of Western Nations in the most practicable manner possible before the notice of the Chinese” (Fryer et al. Citation1875).

John Fryer was the son of a missionary and was born and brought up in Kent, England. In 1861, he found passage to Hong Kong with a job in St Paul’s College and two years later he left for Beijing and joined the Interpreters’ College, before moving to Shanghai. He was a brilliant linguist and became a translator of scientific books for the Chinese government – hired as the English Director of the Translation Department of the Kiangnan Arsenal [江南机器制造总局] in 1868–96 (Wright Citation1996; Feng Citation2013).

By giving lectures, Fryer disseminated Western scientific knowledge through evening classes to the local audience in Shanghai. Following its establishment in 1876, Fryer’s Chinese Polytechnic Institution and Reading Room began recruiting students in 1879 and advertised for teachers to give regular lectures on scientific technology, trading business, and internal and external politics in Chinese (Shi Citation2001). In 1895 Fryer initiated six Classes in Chinese on Saturday evenings on the following technical subjects: “Mining”, “Electricity”, “Survey”, “Engineering”, “Steam Engines”, and “Manufacturing” (Zhu Citation1986).

Fryer’s teaching at the Chinese Polytechnic Institution capitalized on his extensive translation and writing work on scientific subjects. Between 1876 and 1892 Fryer acted as Chief editor of Gezhi Huibian (Chinese Scientific Magazine), which is regarded as China’s first scientific journal and later circulated throughout the country (Lai et al., 2016a: 583, 588–90, 593). In this capacity, he edited a large number of Chinese articles covering broad scientific subjects, including publications on construction such as Western Brickmaking Methods [西国造砖法] (), Sanitary Engineering of Houses [居宅卫生论], Survey Instruments [测绘器图说], Bridge Construction in Western Countries [西国造桥略论] (Fryer et al., Citation1992). Although Fryer was largely self-taught, his work was valued at the time, and his Chinese articles usefully explained construction topics showing a depth of scientific detail and drawing parallels between contemporary practice in Britain and China. Through his active engagement in Gezhi Huibian and activities in the Chinese Polytechnic Institution and Reading Room, Fryer played an important part in science popularization in late-19th-century China.

Figure 4. John Fryer’s Chinese article titled “Western Brickmaking Methods”. (Source: .Xu et al. (Citation1901)

Fryer’s pioneering work in translation and education highlighted the need for standardization of the Chinese technical terminology. He became the Chief Editor and Executive Chairman of the earliest education association in China – the “School and Text Books Series Committee” (by Christian missionaries in China).Footnote13 The issue of standardization of the Chinese technical terminology was hugely important. The Chinese language had no words or characters for a vast range of technical terms used in industry and science for which there was no local equivalent. Consequently, where a word had been needed, it had been made up locally with usages differing from place to place. The lack of a phonetic alphabet made the simple adoption of foreign terms more complicated. Unification of terminology became the main focus of the Committee for the benefit of future scientific book writers, and Fryer set about collecting and editing Chinese technical terms concerning science, engineering, and manufacturing.

After the establishment of Treaty Ports, which brought sizeable Western communities to China, Fryer was part of a small number of bilingual individuals who mediated between Chinese and Western languages. In his own words, he belonged to the small number of “Foreign Residents” with interest “in the improvement of the Chinese” (Fryer et al. Citation1875). There was in this both a genuine philanthropic motivation and a wish to promote the colonial cause. There is no doubt that this vision carried a sense of Western cultural and scientific superiority, but equally he was genuinely enamored of Chinese culture. Fryer described how he saw the Polytechnic he created in Shanghai as a seed that he hoped would lead to “the establishment of branch Institutions by the natives themselves, in different parts of the Empire.” (Fryer et al. Citation1875)

In 1896 Fryer left China and moved to the USA, becoming the University of California’s first Professor of Oriental Language and Literature at Berkeley. He went on to lead a distinguished academic career until his retirement in 1913.

To a certain extent, Fryer’s dreams came true: not only did institutions similar to his Shanghai Polytechnic spring up elsewhere in China by the end of the 19th century, but also more and more Modern schools specializing in particular scientific and technical areas developed rapidly in the early 20th century, among them the Henry Lester Institute, one of the most successful technical schools in Shanghai.

3.3. Henry Lester Institute of Technical Education

The Henry Lester Institute of Technical Education [雷氏德工业职业学校] was a Sino-British experiment aiming to adapt the British polytechnic education to the context of Shanghai. It was founded in 1934, following the will of the English architect Henry Lester (1839–1926). Lester spent his approximately sixty-year-long career as a successful English architect practicing in Shanghai. This experience made him easily see the merits of applied education for professional work, and focus on an Institute for, among other useful and scientific subjects, the study of Civil Engineering and Architecture.

Lester’s vision was to set up a model of British Polytechnics in Shanghai to promote local technical education. Following this vision, both the core faculty and its teaching facilities were constructed according to British standards. The first Principal of the Lester Institute was the British Civil Engineer Bertram Lillie (1901–1939). Under his leadership, a seven-member core teaching team of varied expertise was recruited by Lillie directly from Britain in 1934 (Zheng Citation1988, 184). In the same year, a teaching building was built, which outwardly exhibited British neo-gothic and art-deco elements, and inwardly replicated the typical arrangement of a British college. In addition, state-of-the-art laboratoriesFootnote14 were equipped with Western machinery and tools imported from abroad (Pan and Campbell Citation2018).

The Lester Institute was virtually the equivalent of a British Polytechnic college with a distinctly scientific and practical character. It had a three-year (four-year since 1938) program in “Civil Engineering and Building” in English (from the age of 17). The syllabus included Physics, Mathematics, Chemistry, Geology, Engineering Drawing, Building Construction, Building Science, Electrical Engineering, Hydraulics, Public Works Engineering, Strength of Materials, Theory of Structures, Surveying, Architecture, Carpenters’ Shop, and Laboratory (Fang Citation2007, 252–3). The Night Classes were also established, with attendants being mainly technicians with core roles in industry, who had rich practical experience and were motivated to acquire theoretical knowledge (Fang Citation2007, 92, 144). The close connection between the Lester Institute and the British system was reflected by the inclusion of the Lester Institute – the only one in the Far East except for the Hong Kong University – in the University of London External System (Fang Citation2007, 119–20). The good reputation that the Lester Institute gained in the local industry – i.e., big companies, enterprises, and factories – illustrates its success in the context of Shanghai.

Although the Lester Institute followed the British Polytechnic tradition, the teachers were aware of the differences in the building tradition and the context of construction in the Shanghai setting. For the sake of illustration, the teachers prepared their own lecture notes instead of using textbooks by other institutes (Fang Citation2007, 202–3), as they recognized the impracticality of the latter.

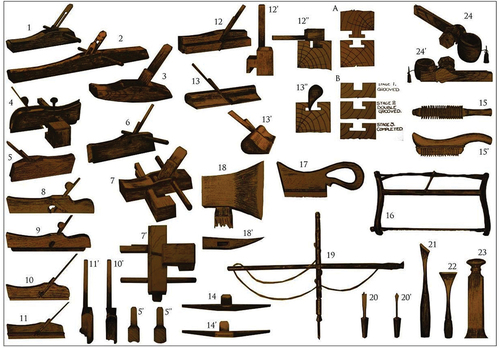

Alfred Emms gave a good example of a Lester Institute teacher who digested various sources of information when he approached teaching construction in a different context. Emms was trained through a seven-year apprenticeship in Britain and firstly worked as a carpenter in Bradford, England in the early 1920s, before turning to teach carpentry and joinery at the London Institute’s Technical College in the early 1930s (Cody Citation1997). As he moved to Shanghai to become an instructor in charge of the courses “Carpentry and Joinery” and “Carpenters” Shop’ at the Lester Institute (Fang Citation2007, 93, 166–7), Emms was interested in comparing the differences between the British modern technical education and the traditional Chinese apprenticeship in Shanghai at the time (Emms Citation1937). He carried out in-depth surveys of the Chinese carpenters’ tools, timber, and working methods by visiting local carpenters’ workshops and construction sites. () His role as a British construction educator in Shanghai let him see the need to bridge between Western and Chinese practical education in Shanghai through understanding the history of Chinese construction. His study entitled “The Practice of Joinery and Carpentry Amongst the Chinese of the Yangtsze Valley” was published in the proceedings of the “Shanghai Society of Engineers and Architect” (SSEA) in 1937. The reader interested in further details on Emms’s background, teaching methods, and his observations regarding Chinese tools may consult relevant studies in the literature (Cody Citation1997; Pan and Campbell Citation2018).

Figure 5. Alfred Emms’s drawings of Woodworking tools of Shanghai, 1937 (Source: Emms Citation1937, compiled by author).

The Lester Institute and the Chinese Polytechnic Institution and Reading Room are good examples of British endeavors in science popularization, standardization of technical terminology, and the development of adaptive knowledge. Inevitably, however, the Chinese efforts in this direction had a more lasting effect on technical education than these comparatively modest Western ventures. The resistance to Western dominance was driven by a rising number of Chinese engineers, architects, and industrialists, who began creating their own networks with the aim of forming a new Chinese building industry (Pan Citation2019).

One of the challenges was training ordinary building practitioners and the mass of Chinese building craftsmen to work in the new building industry. Various building associations set up their own technical schools for this purpose. One example was the “China Vocational School” in Shanghai established by the China Vocational Education Association, which treated the Lester Institute as a hostile competitor (China Vocational School Citation1935; Tang Citation2013) but reflected the general influence of the British Polytechnics in many ways – e.g., program, syllabus, and textbooks.

Just as the teachers at the Lester Institute faced the challenge of developing adaptive and up-to-date teaching materials for the students, the teachers in the rising Chinese technical schools were confronted with the same difficult task. However, the Chinese technical schools based on teaching in Chinese faced an additional obstacle: The Western dominance in science had resulted in the idea that “Chinese scientific books were inferior to Western ones”, which discouraged Chinese instructors from writing their own (Du Citation1935). To an outsider visiting these schools, it looked as if English had become the language of the modern building practice in China (Tang Citation1934). However, many noted at the time that the use of English textbooks imposed a considerable burden on the Chinese students, especially apprentices and draftsmen from poor educational backgrounds, and much of the content of the books was, in any event, irrelevant to the Chinese context (Du Citation1935). There was both practical urgency and a patriotic desire to develop a Chinese scientific discipline of Building Construction. Yangeng Du’s English-Chinese, Chinese-English Architectural Dictionary [英华, 华英合解建筑辞典] and his building textbook Yingzao Xue [营造学] are important attempts in this direction.

In summary, in a pattern that mirrored shifts in Britain, construction teaching in Shanghai moved from an apprenticeship system in the 19th century to technical education in the early 20th century, with textbooks being written by teachers to help their students. The second line of investigation has shown that this was a slow change. The earliest building construction books brought to China were not for students, but for expatriates wanting to build. John Fryer was among the first to standardize technical terminology and disseminate scientific knowledge in Chinese. His teaching and writing touched on the issues of building construction. Further, the Lester Institute was a Sino-British experiment aiming to adapt British polytechnic education to the context of Shanghai. Alfred Emms set an example of how to approach adaptive construction teaching through the investigation of indigenous building traditions in Shanghai. Although the rising local technical schools questioned the legitimacy of foreign schools such as the British-initiated Lester Institute as a consequence of growing nationalism, these Chinese-led technical schools already received and showed the general influence of Western technical education in building construction.

4. Localization of Mitchell’s building construction in Shanghai

Having individually examined the technical education in Britain and China, we now look at how, at the intersection of British influence and local practice, the writing of construction textbooks was approached in China, with a focus on how Mitchell’s Building Construction and Drawing was used by the Chinese writer Yangeng Du as the basis of his technical dictionary and building textbook. Specifically, it explores how the British experience influenced Du’s experiments in promoting a Building Construction discipline in the Chinese context. This investigation is based on a close comparison between the 10th edition of Mitchell’s et al.’s (Citation1926) and Du’s Dictionary (1933–1936) and Du (Citation1935–1937).

4.1. Yangeng Du

The Chinese author Yangeng Du [杜彦耿] (1896–1961), was a contractor, lecturer, and journal editor. He was born in Chuansha, a town today inside the Shanghai Metropolitan area. While assisting his father in operating their family construction firm, he taught himself English and studied Western building techniques. On 28 February 1931 the Shanghai Architectural Association (1931–1937) was founded, aimed at researching the arts of architecture, improving the building industry in Shanghai, and promoting Eastern architecture. Du played a significant role throughout the Association’s short existence. He taught Building Techniques and English at the Association’s Zhengji Night School (Ye and Fivet Citation2018).

As Executive Commissary in charge of research and publicity, Du set up the Association’s monthly magazine Jianzhu Yuekan [建筑月刊] (literally, the “architecture monthly magazine”), acting as its Chief Editor throughout (November 1932 – April 1937) (Lou and Xue Citation2011). The magazine was also given the official English name “The Builder”, reflecting the inspiration it drew from the homonymous original English magazine in Britain first published in 1843.

The Association also established a library, with a collection of hundreds of building books for the members to borrow. A catalog of the loan books on offer was published in Jianzhu Yuekan in 1934 (Vol.2, No. 8). It listed 38 Chinese and Japanese books, including the English-Japanese Building Dictionary by the Architectural Association of Japan; 23 types of Chinese and Japanese architectural magazines; 14 types of English architectural magazines, including the original English magazine “The Builder”; and 14 English building books, including Building Construction (Elementary & Advanced) by the Mitchells.Footnote15 We will see later why, among so many English and foreign reference books, Du chose Mitchell’s works as his main source.

Du’s special status within the Shanghai Architectural Association provided him with comparatively rich resources and convenience for his construction writing: he had great control over both the collection of reference books and the publishing media. Du clearly understood the value of the architectural magazine as an effective publicity tool and ideal medium for teaching. The publication of his Dictionary and textbook first in serial form in Jianzhu Yuekan gave his construction writing and teaching exposure to a very wide audience in the building industry of Shanghai and across China. While Du’s Dictionary was eventually published as a standalone 400-page book in 1936, his textbook was never finished and published as a single volume due to the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937. Having been published first in serial form, however, most of his construction writing had spread around effectively, leaving a unique legacy.

4.2. Terminology learning

Technical terminology is one of the most challenging aspects of the discipline of building construction. In addition to the general language challenge inherent in the use of foreign textbooks in technical schools, students and teachers in 1930s China still faced the lack of many building construction terms in Chinese equivalent to the foreign counterparts – the same problem that John Fryer had tried to solve for basic science but had never been dealt with for building construction.

In his Preface of Du (Citation1935), Du wrote that 20 years before (i.e., in 1915) he had read Mitchell’s Building Construction and Drawing (likely the 8th edition published in 1911). It is interesting to note that when Du started to write his own book two decades later, he decided to base it on the same book, but he managed to obtain an updated edition. Clearly, Mitchell’s textbooks had something different from other Western building construction textbooks and this strongly appealed to Du. It is also clear from his Preface that, among the several reasons behind the long delay in his writing plan, technical terminology was an important one and Du decided that he first had to systemically tackle the translation and explanation of important Western construction terms by compiling a dictionary.

Our comparative study reveals that Du first used Mitchell’s textbooks as one of the key references for his Dictionary, and later fully imported Mitchell’s method of presenting technical terminology into Yingzao Xue. The merits of Mitchell’s terminology-learning system make it easy for us to understand Du’s choice today. Mitchell’s textbooks, after many years of updating, had developed into a mature textual system: each paragraph started with a technical term emphasized in italic, followed by an explanation, thereby guiding the students to focus on the learning of these technical terms. Therefore, Mitchell’s textbook could also be used as a descriptive glossary of building construction, as the technical terms were arranged according to the theme (e.g., Masonry) while taking into account the alphabetical order. ()

Du’s decision to first develop a dictionary of technical terms reflected his appreciation of Mitchell’s pedagogy of construction teaching, specifically its emphasis on the teaching of technical terminology. () While highlighting technical terms in bold or italic in construction books was not Mitchell’s invention (other British writers before Mitchell such as Davidson had done so), Mitchell had the merit of optimizing this method to make the construction textbook equally effective as a technical glossary.

Figure 6. Technical terms on Masonry highlighted in italic in Mitchell’s textbook (Mitchell et al. Citation1926).

Table 1. Translation of Mitchell’s technical terms in Du’s Dictionary and in the Masonry chapter in Du’s Yingzao Xue.

Du had other ambitions: his Dictionary was not only about translating technical terms and explaining their meanings, but also about creating a unified terminology. Given the lack of technological standards at that time, terminological inconsistency had to be tackled. This was an extra challenge that Mitchell did not face. Although Du brought notable improvements to the standardization of technical terms for the Sino-English building trades, some terms in Du’s terminology showed connections with the craftsmen’s language. For instance, Du translated “key (keystone)” in Western masonry into “laohupai”, meaning “tiger plate”, the term used for the same element in local craftsmen’s language. Essentially, Du standardized and encouraged one of the many terms, choosing in each case probably what was the most commonly used term in the Shanghai region at the time. In this respect, Du’s Dictionary is an epitome of the transition of technical terminology from an apprenticeship system to technical education in Modern China.

Affected by the growing nationalism in the 1920s-30s, Du’s intention to promote Eastern architecture can also be clearly seen in his terminology. Examples of Du deliberately using old-fashioned terms for China’s traditional architecture include his translation of “section” into chuangongyang, meaning cross-palace drawing, “plan” into dipanyang, and “King Post” into zhengtongzhu. This attempt was most immediately demonstrated by the title of his book Yingzao Xue, named after Yingzao Fashi and Yingzao Xueshe, with “Yingzao” meaning construction with “artisan’s wisdom”, an old-fashioned word from classical Chinese associated with traditional craftsmanship.

Du’s English-Chinese, Chinese-English Architectural Dictionary, published since 1933, was the first architectural dictionary ever published in China. The unprecedented achievement of Du’s Dictionary was appreciated by the famous Chinese architectural historian Sicheng Liang in 1935 (Liang Citation1935). Its influence can be seen in various construction documents at the time – e.g., the Chinese edition of Shanghai Building Regulations published in 1934 – which were consistent with Du’s terminology. Therefore, the impact of Mitchell’s Building Construction textbooks in Chinese construction teaching firstly relates to the fact that Mitchell’s works inspired and contributed content to the earliest architectural Dictionary in China.

4.3. Visual learning

It is important to note that, in addition to the outstanding advantages of Mitchell’s terminology learning system, Mitchell’s textbook contained abundant construction drawings, which corresponded to the technical terms providing supplementary visual explanations. Mitchell’s Building Construction and Drawing is the only English textbook that Du drew heavily on. There may be multiple reasons behind such a choice, but Du’s appreciation of Mitchell’s pedagogy in visual learning was surely one of the most important. This was particularly helpful for the Chinese students practicing in the Western-led building industry in the early 20th century, because the written language was sometimes insufficient to fully and accurately describe the shape, feature, and relationship of unfamiliar Western building components. This also explains why Du’s Dictionary contained plentiful illustrations: wherever Du needed drawings to clarify the technical terms related to construction details, in many instances he copied the drawings directly from Mitchell’s Building Construction textbooks. ()

Figure 7. An illustration in Du’s Dictionary (1936a) copying one from Mitchell’s textbook (see ) with the annotations still in English.

Mitchell had paid great attention to illustrations from the first edition in 1888, which was also the aspect that he had received the most praise for. Firstly, Mitchell’s illustrations had been carefully designed, with the aim to effectively communicate the essence of the construction problem. Some illustrations reflected the relationship between the parts and the whole; some others contained dynamic connotations (e.g., exploded-view axonometric drawings of timber joints), reflecting the assembly process. Secondly, Mitchell’s illustrations provided various technical solutions for comparison. This helped students select, combine, and develop their own construction solutions in the face of actual construction problems. Thirdly, each of Mitchell’s illustrations corresponded to one or a group of technical terms, so the illustrations and text in Mitchell’s textbooks worked together, forming a self-contained and cross-referenced teaching system. This can explain why Du closely followed Mitchell not only in the text but also in the illustrations. Indeed, according to our careful comparison, five out of every six illustrations in Yingzao Xue were copied directly from Mitchell’s Building Construction and Drawing almost line for line, with only the captions and annotations changed into Chinese. ()

Figure 8. Illustrations about masonry on page 137 of the Building Construction and Drawing (Mitchell et al., 1926: 137) .

Figure 09. Illustration about masonry in Yingzao Xue. (Source: Du Citation1936b, 36).

Why did Du draw so abundantly from Mitchell’s illustrations, instead of producing his own? This can be readily understood if one considers that a chief problem facing any author setting out to write a textbook on building construction is the need to prepare a large number of illustrations. Indeed, Du must have realized the challenge that illustrations were time-consuming and costly to prepare and needed to be drawn by someone who understands them fully. Specifically, the cost of producing new illustrations – rather than merely changing a few when required – provided a considerable barrier for a new book to enter the market. Consequently, copying illustrations has been a common practice throughout the history of building construction books around the world, although Du may not necessarily have known this. We have previously shown elsewhere that the illustrations of the stability of walls found in Jianzhu Xinfa were directly derived from Gwilt’s Encyclopedia of Architecture (Pan and Campbell Citation2015), which can itself be further traced back to earlier European sources such as Rondelet (e.g., see ). In consideration of this, it is easy to see why Du chose to use Mitchell’s Building Construction and Drawing as the main source for the illustrations in Yingzao Xue, especially given the tremendous success of Mitchell’s textbook and its well-developed illustrations that had been refined over its many editions.

Figure 10. Illustrations about the stability of walls by Rondelet (Citation1828) (top), Gwilt (Citation1842) (middle), and Zhang (Citation1910) (bottom) .

4.4. Adaptive knowledge learning

4.4.1. Organization

While Du abundantly copied Mitchell’s illustrations and text, he adapted his book to the Chinese context. One merit of Building Construction and Drawing is that Mitchell’s structure was easy to follow. It also made it easy for Du to add new sections on China’s particular circumstances (i.e., building industry, building classification, history and methods of brickmaking, hollow bricks, stone making and Chinese masonry). These new topics conveniently fit into the existing structure, without a particular need to have separate chapters. ()

4.4.2. Illustrations

Of the illustrations in Yingzao Xue that were not copied from Mitchell’s textbook, many were from contemporary Chinese sources. For example, Yingzao Xue used a hand drawing of xumizuo [须弥座] (a decorative stone footing of Eastern architecture or sculptures) by Sicheng Liang.(Liang Citation1984) () This drawing frequently appeared in later significant history textbooks in Chinese architectural institutes, including Chinese Architecture History (Pan Citation1982). Perhaps such Chinese traditional motifs were included in a practical, modern building construction textbook thanks to the inspiration of the British “Edwardian Free Style”. In the 1920s, the Edwardian style in Britain combined historical detailing from many different periods to produce a decorative whole (Service Citation1977). Classical masonry was still being shown in the 1926 edition of Building Construction and Drawing. Through shadowing Mitchell’s textbook, Du’s inclusion of Chinese traditional motifs can be read as an intention to construct a new style reflecting its Chinese lineage.

Figure 12. Illustration of Song style and Qing style xumizuo in Yingzao Xue (Du Citation1936c, 25), which is an identical copy of Sicheng Liang’s drawings.

English influences brought Edwardianism to Shanghai in the first couple of decades of the 20th century. A considerable number of ‘Edwardian Free Design’ buildings were built in Shanghai between 1900 and 1910. Then, a tide of European Free Style appeared, drawing its inspiration from all over Europe, and this was followed by Chinese Free Style design in Shanghai. Before Du’s textbook was published, the American architect of Chinese origin Poy G. Lee (Nellist Citation1933) had used xumizuo in his design for the Young Women’s Christian Association (Y.W.C.A.) Building in Shanghai (). Erected in 1933, it combined Art-Deco style in a simplified and bold monumental manner with Chinese classical detailing. Perhaps this inspired Du to introduce Chinese architectural vocabulary into his textbook. At the time, developing a discrete modern architectural style that China could call its own was one of the top concerns among the rising elite Chinese architects. Du did show the new spirit appearing among Chinese architects in the proposed contents of his later chapters, which sought to promote Eastern architecture, not only through historical concepts in research and education but also in design practice.

The development of Chinese building construction textbooks can be seen as a history of exploration of how to address the uniqueness and peculiarity of Chinese traditions using Western knowledge of scientific construction. Du dealt with this problem through the retention and replacement of particular content. For instance, in the Masonry chapter in Yingzao Xue, Du copied almost all the construction drawings, but replaced the illustrations of English instruments with the Chinese tools and factories. This shows that the Chinese workers could now work to the same details as the English elementary textbook instructed, although the materials, labor organization, and tools were different. Chinese peculiarity, therefore, was preserved by adapting Chinese construction to meet the requirements of Western methods and new materials. These changes of drawings signal a transition in the understanding of British building construction, from passive copying to active innovation with a clear purpose.

4.4.3. Text

Du wrote in his Preface that “Books that address the circumstances of other countries should not be simply translated for our usage. They could be used as references, but the primary sources of our books should be based on local circumstances and collected locally”. Descriptions of “work to be done” or “Labors” belong to the category of information that tended to have to be changed to suit local traditions. In an example about stonework quoted from Building Construction and Drawing below, while Mitchell specified the commonly-used types of British stones in the Masonry chapter, such as “a Bath or soft limestone” or “Portland or York”; Du chose not to address any particular type of stones. Instead, he deliberately adapted the text, to apply to any kind of local stone that might be available.

The use of different types of timber in China had been addressed in the earliest Chinese Building Construction textbook Zhang (Citation1910). In the 1930s, the phenomenon of using imported timber continued to manifest itself through the replacement of Mitchell’s passage on timber joints, binders and girders with Du’s own words. It is interesting to note that “northern pine/Scotch fir/yellow deal” and “pitch pine” in Building Construction and Drawing were changed to be “Chinese fir”, “Chinese pine” and “Oregon pine” in Yingzao Xue (Du Citation1936d, 31).

Another notable feature is the relationship of the content to “building control” in Du’s Yingzao Xue. Accounts of fire prevention, ventilation, and structural stability in Zhang (Citation1910). The inclusion of such content in Jianzhu Xinfa coincided with the time when most Chinese cities were striving to bring in mandatory building regulations to ensure safety and basic hygiene. Jianzhu Xinfa dealt with these issues by giving Western examples as references. By contrast, Du’s Yingzao Xue shows details taken from local practice and provides references to Chinese building regulations and laws. By this time, building regulations had been introduced in the principal cities in China.

In summary, the authors have shown that Mitchell’s Building Construction books had an important place in the development of Chinese construction teaching in Shanghai and beyond. Mitchell’s works influenced China’s earliest architectural Dictionary published since 1933 by Du in Shanghai. Both Du’s technical dictionary and Yingzao Xue were disseminated widely, through being first published in serial form in architectural magazines. Although Yingzao Xue is an unfinished work and the publication time is not the earliest (i.e., 1910), these shortcomings cannot obscure its glitter. Yingzao Xue was possibly the most ambitious building construction textbook of the time. Unlike previous Chinese construction textbooks, Du’s Yingzao Xue reveals his insights into the well-developed British tradition of construction textbook writing. Du understood Mitchell’s methods in Building Construction and Drawing: focusing on the teaching of “technical terms”, emphasizing “visual learning” through abundant illustrations, and developing “adaptive knowledge” to bridge in-class teaching and actual practice. This understanding was turned into action, as can be seen through the way how Du based on Mitchell’s books to develop his own works. In this context, Mitchell’s Building Construction books found a new and unexpected role in a context very different from the one they were written for and in a way the author could never have predicted.

5. Conclusion: “Hybridity” in construction education

This paper has shown that building construction textbooks from the 19th and 20th centuries in Britain and China provide a unique legacy in modern construction education. They constitute a rich source for understanding the tremendous evolution of building construction at the time and the changing nature of construction teaching from apprenticeship to technical education in both countries. Furthermore, given the mixing of features of the modern building industry in Shanghai, building construction textbooks also serve as significant evidence of the more theoretical question of “hybridity”, i.e., the interaction of indigenous traditions and Western imports in China.

This paper has shown that Du’s writing of Yingzao Xue is not simply a problem of language translation. Du was linking two different construction cultures. This paper has demonstrated the knowledge gaps Du was confronted with, and his task to help Chinese builders to adapt to the different way of thinking building technology in the Western-led modern building industry. It was not a passive, but active effort. What Du needed was certainly not only language knowledge, but much more. The linguistic theorist Newmarks defined translation as: “a craft consisting in the attempt to replace a written message and/or a statement in one language by the same message and or statement in another language”. Similarly, Du’s “cultural translation” of Mitchell’s Building Construction in Shanghai can be interpreted as a process consisting in the attempt to replace a discourse of building construction in the building industry of Britain by the equivalent discourse in the building industry in Shanghai. Du’s contribution was to create a wholly new work – a special mixture that filled in the gaps and created a new discourse of Chinese Building Construction for the new global-local building industry in Shanghai. Consequently, this history helps us to see a meaningful process: how an earlier, more homogeneous understanding of building technology affected the construction of a knowledge system, and how new perspectives and voices enriched people’s understanding of others’ and their own building traditions, providing a driving force for the reformation of the existing knowledge system.7

This paper has also shown that, in the educational context, behind the achievement of Du’s Yingzao Xue, it is Mitchell’s three powerful pedagogical tools (i.e., terminology learning, visual learning, and adaptive knowledge learning) that facilitated the transmission of technical knowledge of building construction in a new cultural setting. Terminology learning was not simply an issue of vocabulary. Due to different building traditions and different ways people thought about their buildings, terminology learning came first as a conceptual tool to communicate the new ways of thinking about building technology. Due to the nature of construction as an ensemble of technical solutions that were difficult to express simply in verbal language, visual learning had to accompany terminology learning to illustrate construction solutions, and also to make up for the masters’ on-site demonstration as part of the previous apprenticeship system. Therefore, terminology learning and visual learning were essential instruments for technical representation and communication in modern technical education. Further, adaptive knowledge was essential for keeping up with the rapidly evolving construction knowledge or adapting to particular local circumstances. Adaptive knowledge can be provided by integrating local examples as in the case of Du, and by making constant updates as in the case of Mitchell. These two-plus-one tools were synthesized to make an open framework with high adaptability, and therefore, it was a pedagogical system with great vitality. Just as a century ago, Du learned from Mitchell’s model to develop his Yingzao Xue. Today, in the context of voluntary internationalization processes, this pedagogical system could still guide us in the evaluation and development not just of good textbooks but also the creation of virtual learning platforms for building construction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Census Returns of England and Wales, 1881. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA): Public Record Office (PRO), 1881, available online at <https://search.ancestry.co.uk/> [accessed 12 August 2019].

2 London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754–1932 available online at https://search.ancestry.co.uk/ [accessed 12 August 2019].

3 Baptism 17 October 1886 Parish Register, London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: p90/jne1/011; available online at https://search.ancestry.co.uk/ [accessed 12 August 2019].

4 An Alice Louisa Mitchell was buried in Kensington and Chelsea on 8 January 1892 The central database for UK burials and cremations. Deceased Online. https://www.deceasedonline.com/: [accessed 12 August 2019].

5 London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: p80/ste/015, available online at https://search.ancestry.co.uk/ [accessed 12 August 2019].

6 Census Returns of England and Wales, 1901& 1911. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives, 1901; available online at https://search.ancestry.co.uk/ [accessed 12 August 2019].

7 Home Tidings, August 1884, p.240; Home Tidings, September 1884, pp.267–68.

8 Based on all the available timetables published in the Polytechnic’s monthly magazines: Home Tidings (1879–1888) and The Polytechnic Magazine (1888–1960). But the latter one stopped providing the class timetables after 1903.

9 PM, June 1926, p.102.

10 “Opinions of the Press and Others on Building Construction by C. F. Mitchell” in Mitchell’s Building Construction and Drawing, 2nd edn (1889), p.250; Preface of 3rd edn (1894); Preface of 6th edn (1902); Preface of 7th edn (1906); Preface of 8th edn (1911).

11 PM, August 1933, p.136; C. F. Mitchell was removed to a nursing home on 28 January 1916 for an operation but passed away without warning. A large number of past and present students and masters went to his funeral at St. Saviour’s Church in Ealing on Wednesday 2 February 1916. PM, February 1916, p.1.

12 Birth see: England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. London, England: General Register Office, available online at https://search.ancestry.co.uk/ [accessed 12 August 2019]; Death see: General Register Office. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. London, England, Volume: Brentford Middlesex, 5e; Page: 155 available online at https://search.ancestry.co.uk/ [accessed 12 August 2019].

13 It was reconstituted into “the Education Association of China” in 1890 and renamed “China Christian Education Association” in 1916.

14 “The new teaching building built in 1934 contained a Material Testing Laboratory with modern machines capable of testing structural steel-work and building materials; a large Engineering Workshop equipped with the latest pattern lathes, drilling machines, grinders, etc.; Metal Workshop and Forge; Carpentry Workshop; and Woodwork Machinery Workshop on the ground floor; Lectures Rooms and Administrative Offices on the first floor; and classrooms, student” Common Room, Dining Room, and Library on the second floor’. The Lester School and Henry Lester Institute of Technical Education Shanghai Prospectus 1940–41.

15 Jianzhu Yuekan, Vol.2, No. 8 (1934), the 13th page of advertisements (without page number).

References

- Ashworth, E. 1851. “How Chinese Workmen Built an English House.” Builder 456: 686–688. November 1.

- Biggerstaff, K. 1956. “Shanghai Polytechnic Institution and Reading Room: An Attempt to Introduce Western Science and Technology to the Chinese.” Pacific Historical Review 25 (2): 143. doi:10.2307/3635292. (May), 127-49.

- Burn, R. S. 1854. The Colonist’s and Emigrant’s Handbook of the Mechanical Arts. 1st edn ed. London: William Blackwood and Sons.

- Burn, R. S. 1860. Handbook of the Mechanical Arts Concerned in the Construction and Arrangement of Dwelling-houses and Other Buildings. 2nd edn ed. Edinburgh; London: W. Blackwood & Sons.

- Cody, J. W., 1997. “’Results from Junk’ Teaching Construction in China, 1926-1937”. In: Proceedings of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) European Conference, Berlin, pp.32–36.

- Coomans, T. 2014. “A Pragmatic Approach to Church Construction in Northern China at the Time of Christian Inculturation: The Handbook ‘Le Missionnaire Constructeur’, 1926.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 3 (2): 89–107. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2014.03.003.

- Coomans, T., et al. 2016. Building Churches in Northern China. A 1926 Handbook in Context. Beijing: Intellectual Property Publishing House.

- Du, Y. 1935. “Yingzao Xue.” Jianzhu Yuekan 3 (2): 37.

- Du, Y. 1936a. English-Chinese, Chinese-English Architectural Dictionary, 258. Shanghai: Shanghai Architectural Association.

- Du, Y. 1936b. “Yingzao Xue (Chap.3, Sec.1.” Masonry). Jianzhu Yuekan 4 (5): 36–38.

- Du, Y. 1936c. “Yingzao Xue (Chap.3, Sec.1.” Masonry). Jianzhu Yuekan 4 (6): 25.

- Du, Y. 1936d. “Yingzao Xue (Chap.6, Floors).” Jianzhu Yuekan 4 (11): 31.

- Emms, A. 1937. “The Practice of Joinery and Carpentry Amongst the Chinese of the Yangtze Valley.”, Proceedings of the Society and Report of the Council 1936-1937, pp.1–78. Shanghai Society of Engineers and Architect: Shanghai.

- Fang, Y., ed. 2007. Bequest & Memory: Henry Lester, Henry Lester Institute and Her Students. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

- Feng, J. 2013. “The Regulation of Reorganizing the Translation House Drafted by John Fryer.” Shanghai Archives & Records Studies 15: 155–159.

- Fryer, J., and W. H. Medhurst, 1875. “First Report of the Chinese Polytechnic Institution and Reading Rooms, Shanghai, from March 1874 to September 1875.” North-China Herald Office, Shanghai, pp.5–7.

- Fryer, J., et al. 1992. Ge zhi hui bian (Vols 1-6). Nanjing: Gujiu shudian.

- Glew, H., A. Gorst, M. Heller, and N. Matthews. 2013. Educating Mind, Body and Spirit: The Legacy of Quintin Hogg and the Polytechnic, 1864-1992. London: University of Westminster Press. 10.16997/book9.

- Gwilt, J. 1842. An Encyclopaedia of Architecture: Historical, Theoretical, & Practical. Longmans, 398. London: Brown, Green, and .

- Gwilt, J., and W. Papworth. 1888. An Encyclopaedia of Architecture: Historical, Theoretical, & Practical. new edn ed. London: Longmans, Green, and .

- Hennock, E. P. 1990. “Technological Education in England, 1850–1926: The Uses of a German Model.” History of Education 19 (4): 299–331. doi:10.1080/0046760900190403.

- Holbrow, A. E., 1933. “Polytechnic Magazine (PM)” Aug., p.136.

- Lai, D. 2007. Studies in Modern Chinese Architectural History. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press.

- Li, H. 2004. The Modernization of Chinese Architecture. Nanjing: Southeast University Press.

- Liang, S. 1935. “Book Review: An English-Chinese, Chinese-English Architectural Dictionary.” Bulletin of the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture 6 (3): 186–194.

- Liang, S. 1984. Liang Sicheng Wenji, Vol.2 (Collected Works of Liang Sicheng), 229. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press.

- Lou, C., and S. Xue. 2011. Architects and Master Builders of 100 Years from Shanghai, 186. Shanghai: Tongji University Press.

- Mitchell, C. F. 1888. Building Construction and Drawing. London: B.T. Batsford.

- Mitchell, C. F., and G. A. Mitchell. 1926. Building Construction and Drawing. 10th edn ed., 204. London: B.T. Batsford.

- Nellist, G. F., ed. 1933. Men of Shanghai and North China, 209–211. Shanghai: Oriental Press.

- Pan, G. 1982. Zhongguo jianzhu shi (Chinese architecture history), 157. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Pan, Y. 2014. “Revealing a History of Construction behind the Western Façade: Based on an Architect’s Memoir of an English House Project Published in 1851.” Jianzhushi 170 (4): 117–126.

- Pan, Y., 2016. Local Tradition and British Influence in Building Construction in Shanghai (1840-1937). Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.