ABSTRACT

House is a socio-cultural milieu that is strongly connected to its residents’ lifestyles; thus, any change in their way of living could be reflected in its layout. This research aimed to highlight the impact of socio-cultural factors on the internal layout of public housing residences, especially with the absence of a clear policy that defines the framework of their flexibility or the scope of transformation. In order to develop a comprehensive understanding of this relation, six variables were addressed: social role, social network, hospitality, gender segregation, safety, and privacy. The researchers adopted a mixed-method approach involving a questionnaire survey of 202 residents and 35 face-to-face interviews along with documentation of transformed layouts. The results showed that gender segregation, privacy, social network, and safety are significant socio-cultural factors affecting internal layout transformations. The findings underline the need for a public housing policy incorporating design guidelines which suit a wide range of residents to enhance the adaptability of future projects and, consequently, promote residents’ satisfaction.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Housing is a major investment for families, especially since most people spend most of their time inside their homes. Thus, it is essential to design houses in an innovative way that respects their residents’ needs. Unfortunately, this is hard to achieve in Jordan as there is a general mismatch between housing costs and household income, which makes housing a challenge for people of middle and low income in specific (Jbarat et al. Citation2021; Al-Homoud and Is–haqat Citation2019). Therefore, the Jordanian government established the Housing and Urban Development Corporation (HUDC) to provide Jordanians with affordable housing while maintaining a balance between supply and demand, where it succeeded in delivering 360 housing projects since its inception, including 130,114 housing units distributed in major cities (Al-Homoud and Is–haqat Citation2019).

Under the umbrella of HUDC, several housing projects were constructed and distributed all over the country according to a mass production strategy (Al-Homoud and Is–haqat Citation2019). Although this strategy succeeded in filling the need for shelter, it didn’t pay much attention to the residents’ preferences, values, and perceptions, leading to static home layouts. Such layouts have minimal flexibility, which hinders the possibility of adjusting them to suit individuals’ functional and personal comfort and promotes their satisfaction at different levels (Salama Citation1996; Maina Citation2013). So, it would be beneficial to understand layout transformation in the context of public housing, identifying transformation patterns, their significance, and driving forces.

Layout transformation can be identified as a series of changes in a home layout that takes place over time and varies from rearrangement of furniture and room colour to structural transformations like addition or demolition of some parts of the housing units (Popkin et al. Citation2012; Afifi Citation1991; Salama Citation1996). In other words, layout transformation is related to any type and size of changes, including extensions and/or alterations conducted on the unit’s exterior and/or internal layout (Salama Citation1996). These changes could be a reflection of the physical, behavioural, environmental, social, and cultural aspects of the residents’ needs. Accordingly, a better understanding of this phenomenon will be provided by shedding light on the relationship between the motivational factors of human needs and the housing unit (van Griethuijsen et al. Citation2015; Makachia Citation2015).

In general, home layout transformation is a noticeable phenomenon whose dynamics require identification in terms of cause and effect. Several researchers discussed layout change in terms of adaptation to the physical and environmental aspects within different regions (Avogo, Wedam, and Opoku Citation2017; Mirmoghtadaee Citation2009; Rapoport Citation1969; Shapely Citation2017). Moreover, some studies highlighted the role of cultural values and beliefs in shaping home layouts in western and eastern regions (Aduwo, Ibem, and Opoko Citation2013; Collen and Hoekstra Citation2001; Erdoğan Citation2018; Zadeh and Jamshidi Citation2017). On the other hand, public housing was discussed thoroughly in terms of policy and economy within different contexts (van Dijk Citation2019; Jbarat et al. Citation2021). However, a few researchers attempted to investigate home transformation in public housing. For instance, Aduwo (Citation2011) stated that home transformation could take place due to the designs’ rigidity and minimal flexibility obstructing accommodation to the changing human needs. In the same vein, Avogo, Wedam, and Opoku (Citation2017) emphasized that public housing transformations are inevitable as a natural part of life. Hence, it is essential to set out a strategy that addresses the shortfalls associated with the physical design, especially with regard to living spaces and rooms’ sizes. Likewise, Tipple (Citation2000) confirmed that limited space in public housing is the main reason residents resort to layout transformation.

To summarize, housing units become unsuitable for their residents’ needs in certain situations, leading to diverse types of layout transformation. However, most studies in this context were limited to highlighting the inadequacy of physical layout and the gap between residents’ needs and the specifications provided by the government. Accordingly, there is a need to include social and cultural aspects, as non-physical motivational factors, in measuring residents’ satisfaction and assessing the suitability of public housing units’ internal layout. Many pieces of research have been dedicated to exploring this relation, focusing on the socio-cultural dimension (Rapoport Citation1998; Shapely Citation2017). For instance, Rapoport emphasized the correlation between culture and layout with an extensive volume of illustrations from across the globe. These illustrations confirmed the effect of cultural components (values, beliefs, meanings, standards, norms, and expectations) on shaping the built environment. Similarly, the concept of culture and its applications appear not only in people’s values and beliefs, perceptions, norms, and behaviours but also in the physical environment, houses, neighbourhoods, and cities (Malkawi and Al-Qudah Citation2003). Therefore, the internal layouts can be either supportive or disruptive of their residents’ culture (Rapoport Citation2016).

The motivational factors of transformations extended to include social components such as family structure, social networks, and kinship relations since they affect and are affected by the spatial layout of homes (Mullins, Western, and Broadbent Citation2001; Ke and Hui Citation2015; Askarizad Citation2017). The social and cultural aspects could be linked to the development of the housing design, which is a significant determinant of residents’ satisfaction (Makinde Citation2015). The lack of socio-cultural considerations reduces residents’ housing satisfaction, which leads them to change their homes’ layouts to create more efficient, suitable, and personalized spaces. Based on the previous studies, socio-cultural factors are an integral part of units’ internal layout formation. These factors include the following: a) The Social Role, which entails an organized behavioural pattern where residents’ act as active members in their community who also engage in collective social activities (Benamar, Balagué, and Ghassany Citation2017; Maslow Citation1954; Xie and Hui Citation2015; Erdoğan Citation2018). b) The Social Network, introduced by Maslow, refers to the social ties which evolve a sense of solidarity and belonging among community members. The Social network consists of four elements: membership, influence, the fulfilment of needs, and shared emotional connection (Maslow Citation1954; Sarason Citation1974; Chavis et al. Citation1986; Benamar, Balagué, and Ghassany Citation2017). c) Hospitality is making guests feel comfortable and welcomed and treating them well. It is not only a sign of individuals’ solid social network, but also a trait that is deeply rooted in Arab culture and an essential part of Jordanian’s cultural values and beliefs (Erdoğan Citation2018; Al-Mohannadi Citation2019; Malkawi and Al-Qudah Citation2003). d) Gender Segregation is related to the degree of segregation between males and females, whether within the same family or between family members and guests. It is connected to privacy concerns, especially in conservative countries. e) The safety of individuals, family members, and the neighbourhood as a whole; namely, a sense of protection experienced by residents of a particular area (Okunola and Amole Citation2018; Isah, Khan, and Bn Ahmad Citation2015; Maslow Citation1954). f) Privacy stems from human’s natural need for visual, physical, and psychological space. Usually, it is an outcome of individuals’ cultural and religious beliefs (Jabareen and Carmon Citation2010; Fallah, Khalili, and Rasdi Citation2015; Rapoport Citation2016; Tomah, Ismail, and Abed Citation2016).

Despite the fact that concept of house transformation and public housing were discussed within the Jordanian context, they have been rarely investigated combined. Therefore, this research focused on the phenomenon of house layout transformation of public housing in Jordan to identify its forms and highlight the motivational factors of the internal layout transformations. This study is hoped to contribute to proposing design policies, guidelines, and strategies that suit a wide range of residents and, consequently, improve the adaptability and life quality of HUDC’s future projects.

2. Materials and method

The research problem was investigated in Zebdeh-Farkouh that was selected after general observation for housing projects of HUDC in Irbid City. It was selected according to occupancy level in terms of percentage of occupancy, length of residency, and ownership status. Zebdeh-Farkouh, located in Al-Rabya district that constructed and designed between 1980–1984. It has (126) building, which classified into three types of housing units; A includes (54) units, B includes (26) units, C includes (46) units. Prototype A and B share a similar spatial configuration but vary in terms of entrances locations as shown in ). Each building prototype consists of three-floor levels to include (378) units. Over a period of thirty years, the layout of the housing units has been subject to a series of transformations, as shown in and .

Table 1. Transformation forms.

Figure 1. (a) Internal plans of housing units, (b) Zebdeh-Farkouh public housing master plan, (c) Different forms of layout transformations.

The researchers adopted a mixed-method approach including the following stages: 1) The qualitative stage was built upon general observations of Zebdeh-Farkouh apartment buildings and interviews with residents to identify the common forms of housing units transformations and motivational factors. 2) The quantitative stage was represented by a printed-form questionnaire survey completed by residents of Zebdeh-Farkouh public housing apartments to understand the impact of socio-cultural factors on the units’ internal layout in addition to assessing residents’ satisfaction with the units’ layout.

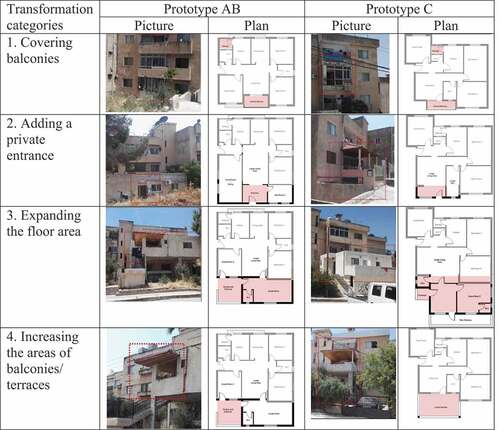

1) Qualitative Stage: Field observations of Zebdeh-Farkouh public housing were made to explore and document the housing units’ transformations. The alterations for (269) housing units were documented through sketches and photographs. Afterward, based on the evident architectural alterations primarily associated with socio-cultural reasons, the transformations were classified into four main categories (, and ). These categories are: (1) covering balconies, (2) adding a private entrance, (3) expanding the floor area either from the living room or the kitchen side, and (4) increasing the areas of balconies/ terraces. The commonality of each transformation category was assessed and illustrated by determining their percentages compared to the total number of housing units. Also, (35) face-to-face interviews were conducted with the residents who have and have not made changes to their houses. This helped to understand the spatial organization and explore the motivational factors for such transformation. The interviews were administrated by the researchers through touring and observing transformations.

2) Quantitative Stage: A structured questionnaire was used to assess the relationship between units’ internal layout and socio-cultural factors. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: i) Section 1 included respondents’ demographic information; family structure, occupation, and education. ii) Section 2 covered the dependent variables and discussed the internal layout measures (factors), including the internal layout’s functionality (ILF) and residents’ satisfaction (ILS). iii) Section (3) contained questions that assess the socio-cultural factors (independent variables). These factors include the social role (SR), social network (SN), hospitality (HO), gender segregation (GS), safety (SF), and privacy (PR).(Figure 4). The definition of each socio-cultural factor includes several aspects, which were all covered through a set of questions. Each variable was measured using five-point Likert scales in which (1 is strongly disagree, while 5 is strongly agree). Dependent and independent variables were identified through a review of the literature, theories, and prior research. summarizes the research variables, their operational definitions, and the corresponding questions.

Table 2. Dependent and independent variables.

Research Sample: To generalize the results to the selected housing case study, the sample of this study represented nearly 50% of the population with a 95% confidence level and 5% confidence interval. Since there are three prototypes of housing units, the sample of each prototype were nearly 50% of the whole prototype population, which means that the sample size is 82 units from prototype A, 39 units from prototype B (increased then to 50 for validity reasons), and 70 units from prototype C. So, 202 responses were collected from residents of housing units via stratified random probability sampling.

The research sample included 62% females, and more than 80% of the respondents were married, and the family size of 52% of which ranged from three to six members. In addition, most of the respondents were educated; this can explain why (74%) of the heads of households and (62%) of their spouses were employed in public and private sectors. The majority of respondents owned their housing units and have been living in their apartments for more than five years, while only 6% of the participants have been living in their apartments for less than five years.

Research Hypotheses:

H1: There is a significant relationship between socio-cultural factors and the functionality of the internal layout (ILF)

H2: There is a significant relationship between socio-cultural factors and residents’ satisfaction with the internal layout (ILS).

Each hypothesis included six sub-hypotheses considering each of the socio-cultural factors (i.e., social role, social network, values, and beliefs that contain hospitality and gender segregation, safety, and privacy).

2.1. Measurement scale analysis

This section discusses the measurement scale analysis steps:

The reliability analysis was performed for each set of variables according to Pallant’s (Citation2020) four levels of the reliability scale: excellent (0.90 and above), high (0.70 to 0.90), moderate (0.50 to 70), and low (0.50 and below). The accepted value of Cronbach’s alpha is 0.7 and above (Taber Citation2018). Nevertheless, according to Taber (Citation2018), values above 0.6 are also accepted. The findings showed that all items exceeded 0.60, which means that all alpha values were reliable. Also, Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.613 for Social Network and 0.860 for Privacy. Finally, the total correlation of each item exceeded 0.3. Thus, the reliabilities indicated adequate convergence and good internal consistency.

Spearman correlation coefficient measures the strength and direction of the linear relationship between the variables.

Assessment for Regression assumptions was checked before the analysis stage to decide whether the data followed or violated any of the regression assumptions. These assumptions include:

Sample size: Pallant (Citation2020) stated that the sample size should be larger than 50 + 8 M (M = number of independent variables). Accordingly, the sample size of this study (n = 202) was acceptable; larger than (50 + 8*6) = 98.

Multi-collinearity: the correlation between the independent variables was less than 0.474. Thus, none of the variables was excluded from the regression analysis.

Outlier The study did not include any problematic outlier for the following reasons; 1) large sample size; 2) only three cases fell outside the standardized residual range, below 1% for the normality distributed sample (Pallant Citation2020); 3) the maximum value of Cook’s Distance was below 1 (0.042); and 4) the residual value, in a case-wise diagnostic table, is of a small value. Therefore, all cases were maintained (n = 202).

Normality: According to the histogram and scatterplot results, there was no contravention. The histogram presented the data in a normal distribution, and the standard deviation value was below (0.995). The scatterplot of the standardized residuals showed an obvious pattern, where the residuals were distributed roughly, with the highest of the scores found to be concentrated around zero points.

Linearity: The results showed that the scatterplot lies uniformly around the regression line, indicating a linear relationship between variables and no violation of the linearity assumption in this study.

Homoscedasticity: since homoscedasticity and normality assumptions are related, it has been acknowledged that all constructs are within a normal cigar shape scatterplot distribution range, and there was no violation of the homoscedasticity assumption in this study.

3. Results

The descriptive analysis was conducted to determine the mean value (M) and standard deviation (SD) for all variables. The results indicated that among the six independent variables indicating the motivating factors influencing spatial layout transformation, gender segregation received the highest mean score (M = 4.12, SD = 0.49), followed by privacy (M = 4.05, SD = 0.52), hospitality (M = 3.94, SD = 0.46), social role (M = 3.91, SD = 0.52), social network (M = 3.77, SD = 0.37) and Safety received the lowest mean score (M = 3.70, SD = 0.38). In respect to the dependent variables, residents’ satisfaction scored (M = 3.83, SD = 0.44), and the functionality of the internal layout scored (M = 4.17, SD = 0.44). The high mean value of internal layout indicates that units’ spaces suit the activities performed within them.

Correlations coefficient was used to measure the strength and direction of the linear relationship between the dependent and independent variables. In general, the correlation findings presented statistically positive significant relationships between variables at level (p < 0.01). The highest correlations were between GS and ILF (rs = 0.634) and between PR and ILF (rs = 0.629). On the other hand, the results indicated a high positive correlation between SN and SU (rs = 0.537).

Regression analysis was performed to test the impact of socio-cultural factors on the internal layout of the Zebdeh-Farkouh housing project in Irbid, Jordan. This objective was sub-divided into two main hypotheses H1 and H2, with Hypothesis 1 (H1) investigated the relationship between socio-cultural factors and the functionality of the internal layout, and Hypothesis 2 (H2) investigated the relationship between socio-cultural factors and residents’ satisfaction with the internal layout.

H1: The relationship between socio-cultural factors and the functionality of the internal layout: The regression analysis results () revealed that Social Role (R-square = 0.169, p < 0.01), Social Network (R-square = 0.253, p < 0.001), Hospitality (R-square = 0.203, p < 0.01), Gender Segregation (R-square = 0.402, p < 0.001), Safety (R-square = 0.198, p < 0.01), and Privacy (R-square = 0.396, p < 0.001) significantly affect the functionality of internal layout. In comparison to other factors, gender segregation seems to have a greater impact on the internal layout, with 40.2% in the variability in participants’ responses to the functionality of the internal layout can be explained by the participants’ desire for gender segregation. In short, the regression study of the first hypothesis (H1) revealed that the six socio-cultural factors had a considerable effect on the functionality of internal layouts, with association percentages ranging from 16.9% to 40.2%.

H2: The relationship between socio-cultural factors and residents’ satisfaction with the internal layout: The regression analysis results () revealed that Social Role (R-square = 0.155, p < 0.01), Social Network (R-square = 0.289, p < 0.001), Hospitality (R-square = 0.138, p < 0.01), Gender Segregation (R-square = 0.241, p < 0.001), Safety (R-square = 0.204, p < 0.01), and Privacy (R-square = 0.224, p < 0.001) significantly affect the residents’ satisfaction with internal layout considerations. In comparison to other factors, social network seems to have a greater impact on the residents’ satisfaction, with 28.9% in the variability in residents’ satisfaction with internal layout considerations can be explained by the participants’ desire for social network. The regression analysis of the second hypothesis (H2) found that the six socio-cultural factors had an influence on inhabitants’ satisfaction with interior layout, although at a low association rate of 13.8 percent to 28.9 percent. Both hypotheses H1 and H2 confirmed that socio-cultural factors are positively related to internal layout and resident’s satisfaction.

Table 3. Regression analysis for the impact of socio-cultural factors.

Additionally, the research examines the disparities in participants’ reactions to the influence of socio-cultural factors in three prototype units that reflect the housing community. According to the ANOVA results, there were no significant mean differences between the dependent variables of the three prototypes (). On the other hand, the ANOVA test revealed no significant differences in participants’ evaluations of the variables (SR, SN, HO, SF, and PR), with the exception of GS, which revealed significant mean differences across groups. The analysis indicated that occupants of prototypes A and B are, on average, more conservative and expressed a preference for gender segregation when altering the units’ spatial layout. Prototypes A and B has a larger size than prototype C as shown in . This motivate units’ transformation to achieve gender segregation for users (family members and guests).

Table 4. Result analysis based on units’ prototype.

Finally, stepwise regression analysis was used to determine which driving factors substantially influenced perception to the internal layout. presents the four models that emerged from the stepwise regression analysis and arranged based on their predictive power for internal layouts and layout transformations. All the regression models are statistically significant, with p values less than 0.05 and r-square value ranging from 0.402 (model 1) to 0.562 (model 4). Moreover, all variables associated with the functionality of the internal layout (GS, PR, SN, and SF) in each model were statistically significant with a p-value is less than 0.05. The stepwise first model suggests that the four most significant socio-cultural factors affecting the internal layout are -in order of importance- gender segregation (GS), privacy (PR), social network (SN), and safety (SF), respectively. The first model revealed that gender segregation accounted for 40.2% in variations of participants’ perceptions of their internal units’ layout functionality. This predictive value grows when each of the factors PR, SN, and SF are added in each model, as shown by the r square change values in . The predictive power improves to 56.5% in the final model.

Table 5. Stepwise model summary.

summarizes the stepwise regression model for residents’ satisfaction with the internal layout. According to the findings, the four most influential socio-cultural factors impacting residents’ satisfaction are social network (SN), Gender Segregation (GS), Safety (SF) and Social Role (SR) respectively. The first model has an r-square of (0.289), the second model has an r-square of (0.379), the third model has an r-square of (0.411), and the final model has an r-square of (0.434). All models are statistically significant, and the socio-cultural variables (SN, PR, SF, GS, and SR) together account for 43.4 % of the variation in residents’ satisfaction with the interior layout. According to statistical study, socio-cultural factor influence both the functionality of internal layout and residents’ satisfaction, with a greater effect on internal layout functionality. Additionally, the findings indicate that one or a combination of socio-cultural factor might operate as predictors of internal layout transformations changes and residents’ satisfaction.

In order to support the findings of statistical studies the interviews were done. The interviews revealed that demographic variable along with socio-cultural aspect have a significant influence on layout transformation. Demographic variable includes family structure, income level, and ownership. The respondents’ comments concentrated on two main topics, namely privacy and cultural values, as social and cultural factors influencing the unit layout transformations. According to the interviews, the demographic profile of the respondents who made transformations in the units’ layout had a large family size, with around 88% of them has more than five members in their families. It was noted that over 60% of the households that underwent transformations had a decent income, with both the head of household and spouse are employed. The fact that they were closing balconies, installing additional entrances, or even enlarging the floor space was attributed to their family’s expansion or an improvement in their financial status, according to some of their remarks. A similar point was made by others, who said that property ownership motivates inhabitants to do more investments in their homes, which is connected to increasing the quality of life and so contributing to the stability of the family.

Similarly, interviewees’ responses emphasized the substantial influence of privacy, with inhabitants attempting to change the spatial layouts and establish hierarchical relationships between areas. This was substantiated by the majority of transformations instances as covering balconies and adjustments from the kitchen side. Additionally, cultural values related with social networks and hospitality revealed as key determinants of house transformations, including the inclusion of private entrances and the expansion of public areas in altered units.

4. Discussion

The study revealed that the socio-cultural factors play a significant role in determining units’ layout transformation and residents’ satisfaction with their units. Moreover, the socio-cultural factors may explain residents’ preferences and the reasons that lead them to change their houses’ internal layout. The quantitative analysis showed that the four most influential factors are gender segregation (GS), privacy (PR), social network (SN), and safety (SF), respectively. This was supported by interviews that highlight the significance of privacy and cultural values that are associated with social networks and hospitality. Furthermore, previous studies revealed that homes layout transformations might take different forms based on residents’ dissatisfaction with the condition of their units which they refer to as “housing deficits” (Mohit, Ibrahim, and Rashid Citation2010; Collen and Hoekstra Citation2001). Furthermore, residents tend to change the layouts of their homes over time to balance between the layout they had in mind and the existing layout (Mirmoghtadaee Citation2009; Aduwo, Ibem, and Akunnaya Opoko Citation2013). Hence, the lack of socio-cultural considerations in designing houses’ internal layout limits residents’ satisfaction (Makinde Citation2015).

The Housing units’ transformations associated with socio-cultural factors yield different architectural forms. The present study includes the following socio-cultural factors:

The Social Role (SR): This concept has been widely investigated in different fields of research (Benamar, Balagué, and Ghassany Citation2017). It is defined as an organized pattern of behaviour regarding the way residents act as community members, respond to the surrounding environment, and engage in social activities. The questionnaire represented the SR factor through four items (), measuring individuals’ social role and participation in social events. Even though the mean values of these items ranged between 3.88 and 3.93 with a total mean of 3.91, their impact on houses’ internal layout turned out to be weak. This could be attributed to the extreme variation in housing units’ designs, such as the used materials, openings’ shapes, and other architectural elements. However, the social factor is closely related to layout transformations conducted to reflect residents’ social status and prestige, like the addition of a private entrance and the expansion of public zones. In other words, the high involvement of family members in social events and gatherings entails a prestigious social status that requires them to make home transformations that reflect this status. Also, major transformation was associated with stability, where people who owned the housing units had more freedom to conduct transformations and then improving their satisfaction level.

Social Network (SN): The sense of community and belonging was first introduced by Maslow (Citation1954), who placed love and belonging in the third tier of the hierarchy of needs. Similarly, Sarason, Sarason, and Pierce (Citation1990) proposed the sense of community theory consisting of four items: membership, influence, the fulfilment of needs, and shared emotional connection (Benamar, Balagué, and Ghassany Citation2017). These four items were included in the questionnaire to assess the SN factor, namely, the strength of the social ties that connect neighbours.

d) Gender Segregation (GS): This factor could be seen as an outcome of the main norms of society, such as privacy, cultural values, and beliefs. Of all the socio-cultural factors, gender segregation had the highest mean value (4.12), confirming that this factor is highly influential in layout design and transformation, especially in conservative societies (Al-Mohannadi Citation2019). Six items () were included in the questionnaire to assess the GS factor by identifying the degree of segregation between males and females, either between family members or between family members and guests. The analysis showed a positive relationship between this factor and internal layout, as the items’ mean values ranged from 4.07 to 4.15. The results of stepwise regression analysis also showed that gender segregation directly affects the internal layout. The strength of this factor was clearly observed in the quantitative results and reflected in the units’ internal design. The four transformation categories can be explained through the interpretation of this factor. GS is demonstrated in Jordanian society by the use of separate guest rooms. This has resulted in adding private entrances, extending the floors area, and covering the balconies close to the living room to increase its capacity for hosting female guests so that the main guest room could be dedicated for male guests. This was confirmed by interviewed residents who assured the importance of having separate entrance and guestroom since they belonged to conservative society, where the cultural values sanctify woman and protect their privacy.

Safety (SF): is another integral requirement of home design and internal transformations (Okunola and Amole Citation2018; Isah, Khan, and Bn Ahmad Citation2015). According to the motivational theory, safety as a general concept occupies the second tier of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow Citation1954). The perception of safety reflects residents’ quality of life in different cultural settings (Jolanki and Vilkko Citation2015). Four items () were included in the questionnaire to assess the SF factor. The analysis showed a positive relationship between the SF factor and the internal layout, as the items’ mean values ranged from 3.58 to 3.76, with a total mean of 3.70. A note worth mentioning is that security cameras and alarm systems were not spotted during the observations, which can be attributed to the Jordanian cultural values which consider watching out for neighbours’ properties and protecting them from intruders a must. The analysis showed that the sense of safety has influenced the housing units’ layout resulting in covering balconies and adding new entrances.

Privacy (PR): Al-Bishawi, Ghadban, and Jørgensen (Citation2017) stated that privacy is essential to Jordanians as it is an indispensable element of their cultural values and religious beliefs. Moreover, the study revealed that privacy affects not only houses’ layout design and transformations but also several other architectural aspects of people’s daily lives, including the way they interact with their surrounding environment. Privacy is translated into hierarchical physical levels. Furthermore, the use of space and how privacy was achieved differ notably among cultures worldwide, resulting in different house forms (Jabareen and Carmon Citation2010; Xie and Hui Citation2015; Rapoport Citation2016). Additionally, the quantitative and the qualitative analysis results emphasized the role of privacy as a significant factor influencing homes’ internal layout. The questionnaire assessed privacy through seven items (), including residents’ desire to avoid visual contact between rooms. The analysis showed a positive relationship between the privacy factor and the internal layout, as the items’ mean values ranged from 3.91 to 4.12, with a total mean of 4.05. The results of the stepwise regression analysis also showed that privacy directly affects units’ internal layout and residents’ satisfaction. In addition, the field observations and interviews revealed that residents make changes in their home layout to adjust privacy levels. On the one hand, some residents resorted to adding private entrances along with the expansion of the living or guest rooms’ area. On the other hand, to emphasize the privacy concept, some residents adjusted their housing units by adding different types of covers or various kinds of landscape to minimize the visibility of the internal spaces, which require additional privacy.

Since the transformation of housing units aims to improve adaptability and life quality, there is a serious need to review HUDC’s design policies to be culturally responsive and respectful of residents’ desires by offering them different layout options that ensure units’ appropriateness and suitability to the end-users. In addition to providing residents with the opportunity to participate in planning/designing during the early design stages. This highlights the need to ensure civic engagement and community participation in HUDC’s designing process leading to diversifying units’ layouts in terms of size, function, and spatial arrangement in alignment with the prominent demographics. Moreover, taking the socio-cultural factors into consideration could lead to more flexible designs and facilitate the inevitable future rearrangement/expansion of internal space.

5. Conclusion

An effective urban and housing policy requires a deeper understanding of the housing parameters, especially in small countries like Jordan, where the population is expanding at breakneck speed (Alnsour Citation2016). There is a growing interest in understanding the way individuals perceive their house’s design and its impact on their lives (Al-Betawi et al. Citation2021). This research revealed that the transformation of individual housing units is driven by social and cultural factors relevant to the residents. Moreover, house transformations take various forms, leading to a better layout that suits the residents’ needs in terms of composition, appearance, and size. Thus, housing should be seen as an ongoing process of transformation, with the interventions of families reflecting their values, ambitions, and requirements. The “Human Development Theory” dictates that families need to be empowered to take control over various aspects of their lives by allowing them to participate in making decisions (Barreiro and Cecilia Citation2006), which is mirrored in home design decisions which would enhance individual’s satisfaction with their lives (Jones-Rounds, Evans, and Braubach Citation2014).

The housing authorities responsible for developing public housing units in Jordan often offer limited choices of housing unit design which overlook the residents’ diverse social and cultural characteristics (Al-Homoud and Is–haqat Citation2019). In light of the study findings and the design of public housing projects in Jordan, it can be said that the implementation of comprehensive multi-scale design and planning processes is a long way off. However, it does open genuine possibilities for policies and small-scale interventions within the early stages of work plans. It is worth noting here that Jordan is implementing the 2025 Jordan program vision (Housing and Urban Development Corporation Citation2020). In this regard, the study results may provide planners and policymakers working on action plans with recommendations that promote the development of responsive housing layouts. This may take the shape of updated design rules, emphasizing the socio-cultural elements and incorporating them in the design process to create feasible solutions. So, flexible design guidelines and strategies will be a good to balance between individuals’ differences and general aesthetics of public housing. Otherwise, residents would conduct transformation activities on their own as informal activities.

In general, the research findings provide constructive insight into socio-cultural factors explaining internal layout design and transformations. However, this study has some limitations as follows: 1) Results of the cross-sectional data analysis limit the generalization of findings to other regions. However, longitudinal surveys create better results for long-term planning and future forecasting. 2) The relatively small sample size (n = 202) was adequate for this study, but also generalizability of findings to the whole region is still a major concern. Therefore, the validity of current study findings is limited to the selected HUDC case only in the region of Irbid city in Jordan. 3) It is expected that some internal transformations relating to changes in space functions was not recorded for this study due to resident’s privacy issues. This can be suggested for future research to advance knowledge and provide better understanding for layout transformation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amal Abed

Amal Abed, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the College of Architecture and Design at Jordan University of Science and Technology. She received her B.S. and M.Sc. degree in Architecture from Jordan University of Science and Technology in 1999 and 2002 respectively. In 2006, she obtained a second M.Arch. in Architecture from Texas A & M University. Her Ph.D. work was in the area of Urban Planning and Environmental Policy from Texas Southern University, 2012. Dr. Abed had gained professional experience through Morris Architects, USA. Also, she is LEED AP (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design - Accredited Professional) certified from GBCI (Green Building Certification Institute), TX. Her research interests are in the areas of Sustainable Development; Social Sustainability, Housing Neighborhood, and Affordable Housing.

Bushra Obeidat

Bushra Obeidat is an assistant professor at Jordan University of Science and Technology. Obeidat holds a Ph.D. in Architecture. She is interested in evidence-based design and the ways in which spatial layouts may promote human experience and organizational goals, as well as how designers might create such spaces. Due to her academic and professional architecture experience, she is well-versed in analytical and empirical methods for comprehending space and its occupants.

Islam Gharaibeh

Islam Gharaibeh, received her BSc and MSc degree in Architectural engineering from Jordan University of Science and Technology in 2017 and 2021 respectively. Her MSc thesis was in the area of public housing internal layout transformations. Gharaibeh had worked as a freelance architect in Jordan and Saudi Arabia skilled in architectural design. She had also worked in the academical field of architecture as a teaching assistant and a part-time lecturer in different universities in Jordan. Her research interests are in the areas of Residential Architecture; Housing Design, Social Housing, and Internal Spatial Analysis.

References

- Abidin, N. Z., M. Isa Abdullah, N. Basrah, and M. Nazim Alias. 2019. “Residential Satisfaction: Literature Review and a Conceptual Framework.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Chulalongkorn University, Malaysia. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/385/1/012040.

- Aduwo, B. E. 2011. Housing Transformation and Its Impact on Neighbourhoods in Selected low-income Public Housing Estates in Lagos, Nigeria. Ogun State, Nigeria: Covenant University. Accessed 17 September 2020. http://theses.covenantuniversity.edu.ng/bitstream/handle/123456789/83/Main

- Aduwo, B. E., E. O. Ibem, and P. Akunnaya Opoko. 2013. “Residents’ Transformation of Dwelling Units in Public Housing Estates in Lagos, Nigeria: Implications for Policy and Practice.” International Journal of Education and Research 1 (4): 5–20.

- Afifi, E. H. A. 1991. “Informal Modifications to Formal Public Housing. Case Study: Ein El Sira Public Housing Project, Cairo-Egypt.”

- Al-Betawi, Y. N., M. Tawfiq, A. A. Abu-Ghazzeh, A. Husban, A. Safa, and A. Husban. 2021. “Disparities in Experiencing Housing Quality: Investigating the Influences of Socioeconomic Factors.” Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 32 (3): 283–307. doi:10.1080/10911359.2021.1895020.

- Al-Bishawi, M., S. Ghadban, and K. Jørgensen. 2017. “Women’s Behaviour in Public Spaces and the Influence of Privacy as a Cultural Value: The Case of Nablus, Palestine.” Urban Studies 54 (7): 1559–1577. doi:10.1177/0042098015620519.

- Al-Homoud, M., and H. Is–haqat. 2019. “Exploring the Appropriateness of the Royal Initiative for Housing for the low-income Group in Jordan.” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, Malaysia. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/471/7/072001.

- Al-Mohannadi, A. S. M. A. 2019. “The Spatial Culture of Traditional and Contemporary Housing in Qatar. A Comparative Analysis Based on Space Syntax.”

- Alnsour, J. 2016. “Affordability of Low Income Housing in Amman, Jordan.” Jordan Journal of Economic Sciences 3 (1): 65–79. doi:10.12816/0029857.

- Askarizad, R. 2017. “Influence of Socio-Cultural Factors on the Formation of Architectural Spaces (Case Study: Historical Residential Houses in Iran).” Creative City Design 1 (3): 44–54.

- Avogo, F. A., E. Akiweley Wedam, and S. Mensah Opoku. 2017. “Housing Transformation and Livelihood Outcomes in Accra, Ghana.” Cities 68: 92–103. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.05.009.

- Barreiro, C., and I. Cecilia. 2006. Human Development Assessment through the human-scale Development Approach: Integrating Different Perspectives in the Contribution to a Sustainable Human Development Theory. Spain: Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. http://hdl.handle.net/10803/5924

- Benamar, L., C. Balagué, and M. Ghassany. 2017. “The Identification and Influence of Social Roles in a Social Media Product Community.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22 (6): 337–362. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12195.

- Chavis, D. M., J. H. Hogge, D. W. McMillan, and A. Wandersman. 1986. “Sense of Community through Brunswik’s Lens: A First Look.” Journal of Community Psychology 14 (1): 24–40. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<24::AID-JCOP2290140104>3.0.CO;2-P.

- Collen, H., and J. Hoekstra. 2001. “Values as Determinants of Preferences for Housing Attributes.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 16 (3–4): 285–306. doi:10.1023/A:1012587323814.

- Erdoğan, N. 2018. “How Do Social Values and Norms Affect Architecture of the Turkish House?” In Socialization: A Multidimensional Perspective, 171. London, UK: IntechOpen. doi:10.5772/intechopen.74166.

- Fallah, S. N., A. Khalili, and M. Tajuddin Bin Rasdi. 2015. “Cultural Dimensions of Housing Entrance Spaces: Lessons for Modern HDVD Housing.” JApSc 15 (2): 173–183.

- Housing and Urban Development Corporation, HUDC. 2020. “General Introduction on HUDC.” Accessed September, 1. https://t.ly/8PxI

- Isah, A. D., T. H. Khan, and A. S. Bn Ahmad. 2015. “Design Implications: Impact of Socio-Physical Setting on Public Housing Transformation in Nigeria.” Journal of Management Research 7 (2): 55. doi:10.5296/jmr.v7i2.6925.

- Jabareen, Y., and N. Carmon. 2010. “Community of Trust: A socio-cultural Approach for Community Planning and the Case of Gaza.” Habitat International 34 (4): 446–453. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.12.005.

- Jbarat, A., T. Mahmmoud Muhammad, S. Mori, and Rie. 2021. “A Review on Housing Affordability and Housing Policy Application in Neglected Border Cities in Jordan.” Journal of Civil Engineering Nomura, and Architecture 15: 156–166.

- Jolanki, O., and A. Vilkko. 2015. “The Meaning of a “Sense of Community” in a Finnish Senior co-housing Community.” Journal of Housing for the Elderly 29 (1–2): 111–125. doi:10.1080/02763893.2015.989767.

- Jones-Rounds, M. L., W. E. Gary, and M. Braubach. 2014. “The Interactive Effects of Housing and Neighbourhood Quality on Psychological well-being.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 68 (2): 171–175. doi:10.1136/jech-2013-202431.

- Maina, J. J. 2013. “Uncomfortable Prototypes: Rethinking socio-cultural Factors for the Design of Public Housing in Billiri, North East Nigeria.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 2 (3): 310–321. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2013.04.004.

- Makachia, P. 2015. “Influence of House Form on dweller-initiated Transformations in Urban Housing.”

- Makinde, O. O. 2015. “Influences of socio-cultural Experiences on Residents’ Satisfaction in Ikorodu low-cost Housing Estate, Lagos State.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 17 (1): 173–198. doi:10.1007/s10668-014-9545-6.

- Malkawi, F. K., and I. Al-Qudah. 2003. “The House as an Expression of Social Worlds: Irbid’s Elite and Their Architecture.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 18 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1023/A:1022445803525.

- Maslow, A. H. 1954. “The Instinctoid Nature of Basic Needs.” Journal of Personality 22 (3): 326–347. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1954.tb01136.x.

- Mirmoghtadaee, M. 2009. “Process of Housing Transformation in Iran.” Journal of Construction in Developing Countries 14 (1): 69–80.

- Mohit, M. A., M. Ibrahim, and Y. Razidah Rashid. 2010. “Assessment of Residential Satisfaction in Newly Designed Public low-cost Housing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.” Habitat International 34 (1): 18–27. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.04.002.

- Mullins, P., J. Western, and B. Broadbent. 2001. “The Links between Housing and Nine Key Socio Cultural Factors: A Review of the Evidence Positioning Paper.” AHURI Positioning Paper No 4 19–34.

- Okunola, S., and D. Amole. 2018. “Explanatory Models of Perception of Safety in a Public Housing Estate, Lagos, Nigeria.” Journal of ASIAN Behavioural Studies 3 (6): 74–82. doi:10.21834/jabs.v3i6.239.

- Pallant, J. 2020. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS. London, UK: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003117452.

- Popkin, S. J., M. J. Rich, L. Hendey, C. Hayes, J. Parilla, and G. Galster. 2012. “Public Housing Transformation and Crime: Making the Case for Responsible Relocation.” Cityscape 14: 137–160.

- Rapoport, A. 1969. “House Form and Culture.” In London-University College, edited by Foundations of cultural geography series, 73. New Delhi: Prentice-hall of India Private.

- Rapoport, A. 1998. “Using “Culture” in Housing Design.” Housing and Society 25 (1–2): 1–20. doi:10.1080/08882746.1998.11430282.

- Rapoport, A. 2016. Human Aspects of Urban Form: Towards a man—environment Approach to Urban Form and Design. Elsevier Science, USA: Elsevier.

- Salama, R. K. 1996. “User Transformation of Government Housing Projects: Case Study, Egypt.”

- Sarason, S. B. 1974. The Psychological Sense of Community: Prospects for a Community Psychology. London, UK: Jossey-Bass.

- Sarason, B. R., I. G. Sarason, and G. R. Pierce. 1990. Social Support: An Interactional View. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Shapely, P. 2017. The Politics of Housing: Power, Consumers and Urban Culture. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Taber, K. S. 2018. “The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education.” Research in Science Education 48 (6): 1273–1296. doi:10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2.

- Tipple, A. G. 2000. Extending Themselves: User-initiated Transformations of government-built Housing in Developing Countries. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press.

- Tomah, A. N., H. Bani Ismail, and A. Abed. 2016. “The Concept of Privacy and Its Effects on Residential Layout and Design: Amman as a Case Study.” Habitat International 53: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.10.029.

- van Dijk, W., J University of Chicago Kenneth C. Griffin Department of Economics job market paper, 0–46 i–xi. 2019. “The socio-economic Consequences of Housing Assistance.” 36.

- van Griethuijsen, A. L. F. Ralf, M. W. van Eijck, H. Haste, P. J. den Brok, N. C. Skinner, N. Mansour, A. Savran Gencer, and S. BouJaoude. 2015. “Global Patterns in Students’ Views of Science and Interest in Science.” Research in Science Education 45 (4): 581–603. doi:10.1007/s11165-014-9438-6.

- Xie, K., and S. Hui. 2015. “How Social Factors Affect the Design of New Urban Residences.” 5th International Symposium on Knowledge Acquisition and Modeling (KAM 2015), London, UK.

- Zadeh, N. F., and H. Jamshidi. 2017. “Identifying Non-material Factors Determining the Shape of the House.” Journal of Architectural Engineering Technology 6 (200): 2.