?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study is to verify that apartment complexes influence social capital in Seoul. We collected the proportion of apartment complexes in autonomous districts and social capital variables such as cooperation with neighbors, community trust, and altruism of vulnerable people through the Seoul survey data for five years. The main results are as follows. First, as the ratio of apartment complexes increased, the level of social capital of community residents around the apartment decreased. In other words, the higher the proportion of area occupied by apartment complexes, which are gated communities in South Korea, the lower the level of social capital of the local community. Second, as the ratio of apartment complexes increased, the level of social capital of apartment complex residents increased. That is, as the area ratio of apartment complexes increased, the social capital level of the community residents decreased, while the social capital level of apartment complex residents generally increased. Third, as the size of the apartment complex grew, the negative impact on the social capital of residents in the community increased. It means that as the size of the apartment complex increased to 500 and 1000 households, the extent of the decline in social capital increased.

1. Introduction

In Korea, the preference for apartments is far higher than for other types of houses (Jun Citation2013). According to the Korea National Statistical Office, as of 2019, 58.2% of all households in Seoul live in apartments. The apartment complex in Seoul has community facilities such as sports facilities, playgrounds, senior citizens’ homes, and libraries (Sonn and Shin Citation2020), and internal surveillance is thorough with 24-hour security patrols. As the majority of residential areas are occupied by high-rise and high-density apartments, the proportion of apartments in the urban landscape of Seoul is substantial (Hwang and Kim Citation2020; Sonn and Shin Citation2020). The phenomenon whereby apartments occupy an overwhelmingly large portion of Korean cities was described by a French geographer as the “Republic of Apartments” (Oppenheim Citation2009). As this expression suggests, Seoul is overwhelmed with apartments.

Apartment complexes are a kind of gated community with respect to the surrounding single-family and multi-family households (Gelézeau Citation2008; Hwang and Kim Citation2020). Residents of apartment complexes that form their community within a specific boundary are spatially neighbors with single and multi-family housing residents, but not socially unless they are neighbors. As a privatized space, large-scale apartment complexes form a clear boundary with high landscape trees and fences and take on a physical form that induces various spatial discrepancies and incompatibility with the surrounding area (Hwang and Kim Citation2020). The entrance and access of outside strangers are controlled, and the internal facilities are provided only for the community. The apartment complex’s characteristics, which focus on social exchanges inside the complex, resemble many of the characteristics of gated communities.

A gated community is a residential complex created to control outsiders’ access at the entrance and provide a safe living environment free from crime (Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004; Low Citation2001). Resident amenities such as recreational facilities and community amenities are provided within the gated community, and the community facilities contribute to the improvement of internal social cohesion (Bible and Hsieh Citation2001; Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004; Townshend Citation2002). The gated community privatizes the internal space and has a low interest in exchanges with the external community, negatively affecting the quality of social relations across the local community (Blakely and Snyder Citation1997; Higley Citation1995; Lang and Danielsen Citation1997; Marcuse Citation1997; Vesselinov, Cazessus, and Falk Citation2007). Though these gated communities’ characteristics are similar to those of apartments, few studies have analyzed apartment complexes from the gated community perspective (Vesselinov, Cazessus, and Falk Citation2007).

Although existing studies have described hypotheses and mechanisms for the negative impact of gated communities on social capital, few studies have empirically examined the gated community’s effects on the local community’s social capital. In particular, apartment complexes in Seoul are a type of gated community that is common in dense urban centers like South Korea. However, there is a research gap on how apartment complexes relate to local social capital. Thus, the purpose of this study is to verify whether apartment complexes have a negative influence on the social capital in their region. In particular, this study analyzed how neighbors’ social capital varied by the proportion of apartment complexes in residential areas. The social capital was measured using variables for cooperation between neighbors, trust in the community, and altruism for vulnerable persons through the items of the Seoul survey data. As for the apartment complex variable, the ratio of the area occupied by the apartment complex in the residential area was measured for each autonomous district. The analysis method was a pooled cross-sectional logit model using five years of data, and this model calculated the odds ratio and analyzed the influence relationship between variables.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social capital characteristics and categories

Social capital intends to an individual’s close relationship with community members, and the level of social capital is measured by factors such as trust, reciprocity, participation, and cooperation. According to Coleman (Citation1990), an early sociologist who formally defined social capital, social capital consists of some aspect of social structure and facilitates certain actions of individuals who are within the structure. Social capital exists in the form of valuable social organizations, information channels, and these resources function positively (Coleman Citation1988, Citation1990). Putnam (Citation2000) explained that the core of social capital is that social solidarity and networks have usable values. He emphasized that the accumulation of social capital affects productivity, whether individual or group (Putnam Citation1993, Citation2000). Social capital is based on the degree of connectedness and the quality and quantity of social relations in a community (Harpham, Grant, and Thomas Citation2002). As a result, social capital means the level of social exchanges between individuals and individuals or communities.

Social capital is divided into bonding social capital and bridging social capital (Gittell and Vidal Citation1998; Szreter and Woolcock Citation2004). Bonding social capital means the social relationship within the same community, and bridging social capital means the social relationship between different communities (Narayan Citation1999). Interactions within communities of similar backgrounds or classes are bonding social capital, and interactions within communities of different backgrounds or classes are bridging social capital (Berkman, Kawachi, and Glymour Citation2014). In addition, social capital includes two components, a structural component and a cognitive component (Subramanian, Kim, and Kawachi Citation2002). Structural elements intend to social capital related to actual actions such as participation and exchange. Cognitive elements intend to social capital related to an individual’s attitudes, thoughts, and perceptions, such as trust, sharing, and reciprocity (Harpham Citation2008; Harpham, Grant, and Thomas Citation2002). Researchers need to separate what people did and what they felt when in relation to studying social capital (Harpham, Grant, and Thomas Citation2002).

Social capital correlates with various environmental factors such as neighborhood environment, social segregation, and crime. Social capital has a close relationship with the neighborhood environment, and in particular, it showed a positive relationship with accessibility, walkability, diversity, and design factors (Mazumdar et al. Citation2018). Another critical factor of the neighborhood environment related to social capital is stability and crime rate. Social control of crime and disorder is strongly associated with social capital (Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls Citation1997; Sampson et al. Citation2005). Local crime and instability play an important role in forming and maintaining neighborhood social capital (Mazumdar et al. Citation2018). In addition, social segregation also shows a negative relationship with social capital. The level of social interaction is low in regions with severe socioeconomic segregation regarding race and income, resulting in unequal social capital (Briggs Citation2005). In other words, when the degree of residential segregation increases, it means that the level of bridging social capital would decrease.

2.2. Gated community physical and social characteristics

A gated community generally refers to a residential complex surrounded by physical barriers such as walls, fences, landscaping, and access restricted to private houses and streets, sidewalks, and nearby amenities in the district (Low Citation2003). The gated community was the first site formed for middle-class retirees in the United States until the late 1960s and 1970s. In the 1980s, real estate development accelerated, and gated communities were built around golf courses for leisure and were monopolized by the middle class (Guterson Citation1992; Low Citation2001). These gated communities are expanding toward providing stable and comfortable housing complexes for families with children in suburban and suburban development (Guterson Citation1992; Lofland Citation2017).

The key to developing a gated community is to control outsider access to the inside. A critical feature of the gated community is that a committee elected by the autonomous homeowners’ association oversees the common property and establishes contracts, rules, and restrictions (Blakely and Snyder Citation1997; Judd Citation1995; Vesselinov, Cazessus, and Falk Citation2007). The gated community provides an environment that relieves fear from crime, reduces the chances of mingling with unwanted neighbors, and creates a sense of belonging to the village community (Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004; Helsley and Strange Citation1999). The gated community is equipped with recreational facilities and community amenities to provide services only for the internal community (Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004). As a result, the gated community provides residents with a sense of community, community identity, security, and convenience facilities and increases property values (Bible and Hsieh Citation2001; Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004; Townshend Citation2002).

The gated community is spatially related to disadvantages such as social stratification and mass production, disconnection of exchanges with residents outside the community, and increasing socioeconomic inequality. The gated community is a residential area separated from the outside of the gated (Vesselinov, Cazessus, and Falk Citation2007). In various cases, residents of the gated community have shown low interest in the population outside the wall (Breitung Citation2012). Residents of the gated community tend to avoid contact with the public and are less interested in the sense of community with neighbors (Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004; Low Citation2001). The gated community realizes a physical environment that is divided into wealthy and poor areas (Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004; Vesselinov, Cazessus, and Falk Citation2007) and promotes the separation of social dwellings (Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004) and spatial stratification (Vesselinov, Cazessus, and Falk Citation2007).

2.3. Typology of gated community and Seoul’s apartment complex

Gated communities can be classified into three types according to their primary purpose: lifestyle communities, prestige communities, and security communities (Blakely and Snyder Citation1997; Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004). Lifestyle communities focus on leisure activities, including recreational facilities, amenities, and services, and are often constructed in retirement villages, golf and leisure facilities, or suburban new towns. Prestige communities symbolize the wealth and status of residents who value image, privacy, and control, and the quality of a gated community depends on their level of wealth. The main features of prestige communities are Beautiful scenery and perfect security, and the communities usually have no common amenities. Due to fear of outsiders, the security community features preventing access of non-residents and requesting protection from local authorities in extreme cases. Though lifestyle and prestige communities show security features, security communities are characterized by the residents’ participation in building barriers themselves actively (Blakely and Snyder Citation1997).

Types of gated communities are distinguished by security, barriers, amenities, characteristics of the occupants, location, and size (Blakely and Snyder Citation1997). Walls and gates are gated communities’ physical, economic, and social symbols and are selected according to community preferences. Security is achieved by blocking the motive of strangers’ trespassing through walls and gates and controlling the entry of outsiders with a security system. Community amenities have the most significant impact on internal residents’ social integration and exchange. Although gated communities’ location is primarily in the suburbs around the city (Blakely and Snyder Citation1997), the communities also would appear in rural areas or rural suburbs (Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004). Consequently, gated community residents can be isolated from residents and strangers outside the community by their own choices.

Korean apartment complexes are one of the types of gated communities that would appear in densely populated urban areas. According to the types of gated communities defined by Blakely and Snyder (Citation1997) and Grant and Mittelsteadt (Citation2004), in South Korea, especially Seoul’s apartments complexes are similar to gated communities in the characteristics of high barriers, the residence of specific classes, and controlling outsiders through entrances, whereas the characteristic of being located to the external community closely is different. Apartment complexes in Seoul interrupt outside access with structures such as fencing, planting, and topography around the site and control outsiders at the main entrance (Hwang and Kim Citation2020). Inside the apartment complex, various services are provided to enhance the bond between inside residents, from a gym, leisure facilities, and library to a swimming pool, sauna, and indoor golf course (Sonn and Shin Citation2020). In addition, apartment communities are mostly socio-economically homogeneous and pursue the purpose of strong privacy protection (Hwang and Kim Citation2020). On the other hand, apartment communities in Seoul are placed nearby other outside communities in dense downtown rather than being alone in the surrounding downtown. In other words, the difference between apartment complexes in Seoul and gated communities in the West is that Seoul’s apartment districts are relatively adjacent to other neighborhoods.

2.4. Social capital according to the gated community

The gated community surrounded by walls, gates, and guards is a threat to social capital, social interaction, and the building of social networks (Davis Citation1992; Devine Citation1996; Etzioni Citation1995; Low Citation2001). The purpose of the gated community, privatized with clear physical boundaries, is to control exchanges with outsiders and exclude outsiders from passing through. This exclusion is intended to fundamentally prevent strangers’ access and access to internal community facilities by neighbors. The substantial privatization of the gated community consequently threatens the level of altruism and integration of the region and promotes regional fragmentation as a protruding new layer of the area (Vesselinov, Cazessus, and Falk Citation2007).

The gated community is physically disconnected and socially disconnected from neighbors and tends to form a community unrelated to social problems and conflicts of external residents (Engle Citation1993). Lemanski’s study of Cape Town emphasized that residents of the gated community and residents outside the fence tend not to regard each other as neighbors (Lemanski Citation2006). As a result, the gated community has social distance as well as the physical distance between them and their neighbors, and there is no tendency to pursue social mixing (Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004).

In urban and residential areas, barriers and boundaries form “landscapes of exclusion,” affecting neighbors’ contact across borders (Cresswell Citation1996; Sibley Citation1995). The boundary distinguishes insiders from outsiders regarding social connection and could act as an influential factor that hinders interaction quality between neighbors. These boundaries form their own identity for each zone and affect intergroup interaction and residential segregation (Dixon Citation2001). As a result, “crossing the line” is regarded as an act that threatens the inner realm of insiders, causing anxiety (Dixon Citation2001; Sibley Citation1995). In this way, the regional boundaries and barriers formed by the gated community have an important influence on social exchanges beyond the meaning of simple physical boundaries.

In the case of Seoul’s apartments, complexes are isolated communities in the area and have a possibility to act as a threat to the social capital of that area. Apartment complexes in Seoul are residential areas that systematically control access to outsiders and are residential districts separated from the surrounding area (Gelézeau Citation2008; Hwang and Kim Citation2020). Seoul’s apartment complexes are equipped with facilities and services to increase the community bonds for the inner residents (Jun Citation2013; Sonn and Shin Citation2020). In addition, apartment prices in Seoul are somewhat higher than those of single-family and multi-family houses in the vicinity due to the brand value of the apartment and various infrastructure related to transportation and convenience facilities (Jun Citation2013). Therefore, Seoul’s apartment complexes are a type of housing mainly occupied by upper and middle classes due to their high prices and are a type of housing that causes residential segregation in the region (Hwang and Kim Citation2020; Jun Citation2013). As such, apartment complexes in Seoul can act as a factor that causes community separation and social capital retreat due to the characteristics of a certain socioeconomic class isolated physically and socially in some districts.

3. Research framework

3.1. Study hypothesis

Though existing studies have specifically explained the negative relationship between gated communities and social capital, few studies are related to verification through empirical statistical analysis. In particular, Seoul’s apartment complexes are kinds of gated communities that can appear in dense cities like South Korea, and understanding of apartment complexes is very limited. Therefore, this study analyzes whether apartment complexes reduce social capital similar to the negative effect of gated communities. We analyzed based on three hypotheses. The first hypothesis is that the higher the proportion of apartment complexes in the area, the lower the level of social capital in the community. The second hypothesis is that the higher the proportion of apartment complexes in the area, the higher the social capital level of the apartment complex residents. The third hypothesis is that as the size of the apartment complex increases, the negative relationship between the apartment complex and the community’s social capital would increase.

3.2. Study area

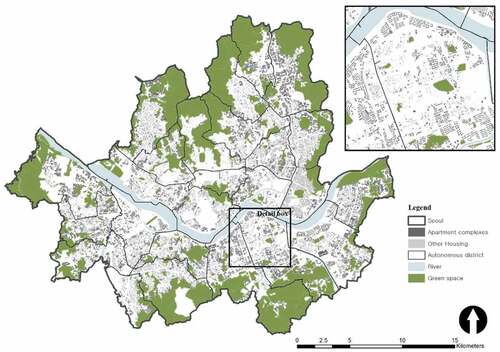

As of 2019, the proportion of households living in apartments in Seoul is 58.2%, and high-rise and high-density apartment complexes have become distributed throughout residential areas. The apartment complex creates a unique urban landscape in Seoul, rising partially around low-rise multifamily houses (). The supply of apartment complexes in Seoul began in the 1950s–1960s for post-war recovery and housing supply. After the 1970s, the government provided a modern lifestyle with housing supply to the middle class by supplying large apartment complexes. Apartments are currently a significant housing type in Seoul and are constantly increasing (Shin and Kim Citation2016).

Since the spread of apartments, the proportion of households living in apartments in Seoul has been steadily increasing. According to the Korea National Statistical Office statistics, the total number of apartments was 974 thousand (50.8%) in Seoul in 2000. As of 2019, the total number of apartments had continuously increased to 1,720 thousand (58.2%). The average number of households in an apartment complex in Seoul is 628, and the maximum number of households is 9,510. Since apartments are a convenient urban infrastructure and have a rather higher demand than other houses (Jun Citation2013), this rapid increase is expected to continue. The current distribution of apartments and single/multi-family homes in Seoul is shown in below.

3.3. Data resource and variable specification

Social capital and demographic characteristics were used from the Seoul Survey data. The Seoul Survey data has been investigating the contents of individuals’ residential environment, economy, and society to grasp Seoul citizens’ life and social perceptions annually. It contains various social capital-related contents and diverse demographic items such as income, occupation, health, and pedestrian environment. This study used cooperation with neighbors, trust of regional society, and altruism for a vulnerable person as dependent variables for measuring social capital.

The previous studies mainly measured social capital through social trust, participation, cooperation with neighbors, norms, and so on (Harpham, Grant, and Thomas Citation2002; Won and Lee Citation2020). This study measured the level of social capital through cooperation with neighbors, trust of regional society, and altruism for a vulnerable person in the Seoul Survey. The more cooperative an individual is with the community, the more they can get various information and benefits from the community, and they want to belong to the community (Kiwachi, Subramanian, and Kim Citation2008). For the measure of cooperation with neighbors, respondents answered on a 5-point Likert scale of “very low” to “very high” question to “how much do you help and receive from your neighbors?” Based on the study of Harpham (Citation2008) and Subramanian, Kim, and Kawachi (Citation2002), as the structural component of social capital is the actual behavior and connection, the cooperation with neighbors is the structural component.

Community trust is a collective property, a resource capable of collective action, and a valid measure of social cohesion (Kiwachi, Subramanian, and Kim Citation2008). As a measure of trust for regional society, respondents answered the question “How much trust do you have in your family, neighbors, and public institutions?” based on a 5-point Likert scale from “very low” to “very high.” Altruism is an important indication for diagnosing the level of social capital because people with good social networks spend more time and money on charity and volunteering for the community than those who are isolated (Putnam Citation2000). As the measure of altruism for a vulnerable person, respondents answered the question “How considerate are you toward the disabled, the elderly, and women?” based on a 5-point Likert scale from “very low” to “very high.” Based on the study of Harpham (Citation2008) and Subramanian, Kim, and Kawachi (Citation2002), as the cognitive component of social capital is perception and thought, trust and altruism are the cognitive components.

As a demographic and socioeconomic control variable associated with social capital, this study included gender, age, education, homeownership, and job (Harpham, Grant, and Thomas Citation2002; Kang and Koo Citation2020; Putnam Citation2000). The study of Putnam (Citation2000) showed that the perception and level of social capital differed by age and gender through various graphs. Factors such as educational attainment are highly correlated with physiological stress and access to community resources (Lindström Citation2008). Regional and individual economic differences cause differences in community bonds due to inequality in investment in programs and services related to social capital (Lindström Citation2008). For this reason, this study included the household income, employment status, and the average apartment price of the region as individual and regional economic factors. Families have characteristics such as high-density networks and collective support, and family composition is associated with people’s social and interdependent relationships (Widmer Citation2006). Thus, we included family composition and marital status as control variables. Homeownership is a variable related to local settlement, and the neighborhood with the high rate of homeownership is the basis for social capital formation (Yamamura Citation2011). Finally, as the length of residence is related to the degree of interaction with neighbors, the factor is connected to social capital (Kan Citation2007; Yamamura Citation2011).

The Seoul apartment data used the apartment current situation data provided by the city of Seoul and the housing transaction price of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. This study collected the total area of apartment complexes in the autonomous district by the number of households and year through the apartment current situation data. Besides, we used the housing transaction price data from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport to calculate the housing price in the autonomous district from 2015 to 2019.

Under the assumption that there might be a different influence of the apartment district on social capital according to the size of the apartment complex, the apartment size is subdivided based on the number of households. This study measured the scale of apartment complexes over 500 households in medium-size and over 1,000 households in large-size complexes. The apartment complex variable was calculated as the ratio of the apartment complex areas to the residential area in the autonomous districts. In other words, it is the ratio of the total apartment complex area to the entire residential area of the autonomous district ().

Table 1. Variable description and data source.

3.4. Method

Because the dependent variables, cooperation, trust, and altruism, are concepts that are separated as structural and cognitive components, we analyzed them separately for each dependent variable element, not for multivariate regression. This study applied the ordered logit method to data in which the dependent variable, social capital, responded sequentially. When the ordinary least square (OLS) analysis method is applied to a model in which the dependent variable is ordinal, the model might produce bias or inconsistent analysis results (Blanchflower and Oswald Citation2004; Finkelstein, Luttmer, and Notowidigdo Citation2009). Therefore, this study utilized ordinal logit analysis with maximum likelihood estimation. In addition, this study constructed the area ratio of apartment complexes and individual social capital variables and employed pooled cross-sectional data through five years of the Seoul Survey data conducted annually for an unspecified number of subjects. The apartment area ratio might include regional characteristics according to regional surveys and temporal characteristics according to yearly surveys. Therefore, to consider the local heterogeneity and temporal heterogeneity not observed in the data in the model, this study analyzed a location fixed-effect and a time fixed-effect.

To verify the research hypothesis, we analyzed models by apartment complex size and compared coefficient values of apartment complex ratio between models. Although comparison of coefficient values is possible through standardized coefficients, the calculation of standardized coefficients is impossible in logistic regression analysis. As an alternative, according to the study of Bauer (Citation2009), it was emphasized that standardization or rescaling of variables should be a prerequisite for coefficient value comparison in logistic analysis. Based on this alternative, we first unified the unit of the apartment complexes ratio, which is a variable for comparison, into the percentage ratio. Second, samples, time, and variables were set identically to enable analysis under the same conditions between models. In other words, we analyzed to compare the apartment complex ratio variables according to apartment complex size under the identical conditions as the sample and the variable.

The formula of social capital according to region j and time t of each respondent i is as follows. For a ordinal logit model ,

is the probability of response

.

is the dependent variable of respondent i at region j and time t, and the dependent variable is a measure of cooperation, trust, and altruism as social capital.

is the ratio vector of the apartment complex, which is the ratio of the region of the apartment complex at time t in the j area, and

is the characteristic socioeconomic vector of individuals, which is the characteristic value of the respondent.

is the model considering the heterogeneity characteristic of the region as a fixed effect.

is a dummy variable having a value of 1 if it corresponds to the j region and 0 otherwise.

is the model considering the heterogeneity characteristic of time as a fixed effect.

is a dummy variable having a value of 1 if it corresponds to the year t and 0 otherwise.

4. Empirical results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

The basic statistics of variables from 2015 to 2019 are as follows (). The number of data points for the social capital and individual characteristics variables used in this study is about 45,000 each year, for a total of 220,622 for five years. As social capital, the variable for cooperation with neighbors has an average of 3.66 and shows a roughly normal distribution. The community confidence score averaged 3.35, which is approximately normal. The altruism for vulnerable people is modest, with an average of 3.17. Regarding cooperation with neighbors, trust in the community, and altruism for vulnerable people, the level of cooperation is somewhat high, and the altruism level is relatively low.

Table 2. Summary of statistics.

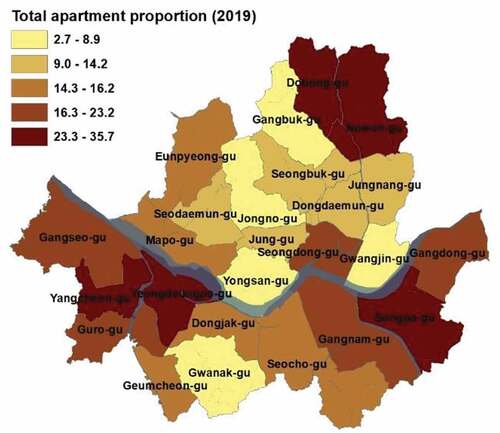

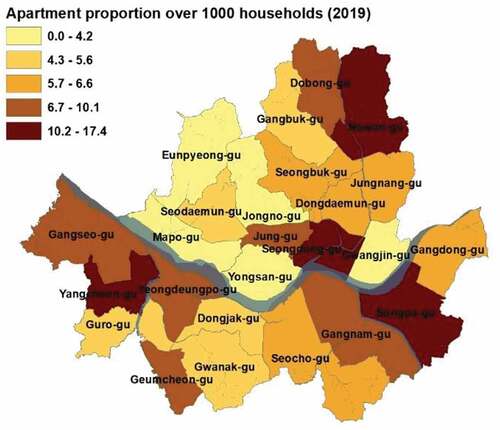

The basic statistics of the apartment complex area ratio as the primary variable of this study are as follows (). The number of samples of 25 autonomous districts over five years was 125, and the average ratio of total apartment complex area to a residential area was 7.3%. However, the smallest autonomous district was 2.6%, and the largest number of autonomous districts was 38.6%, with a wide gap between autonomous districts. The ratio of medium-sized apartments with 500 households or more to the residential area is 5.5% on average. The minimum ratio for autonomous districts is 1.7%, and the maximum ratio for autonomous districts is 29.4% (). Lastly, the proportion of large-scale apartments with 1,000 households or more to the residential area averages 4.2%. However, some autonomous districts do not have apartments with 1,000 or more households, and some autonomous districts account for 19.1% ().

Figure 4. Apartment district ratio over 1000 households in Seoul, South Korea.

The basic statistics of socio-economic attribute variables are as follows (). The proportion of women is 48.1%, with a slightly larger sample of men. The age group ratio is the most, with 22.8% in their 60s or older, followed by 19.8% in their 50s and 19.8% in their 40s. The academic background is 34.0% university graduates, and the average total income is 4.85 million won. The minimum and maximum values of the regional economic level are 350 and 1,492, respectively, with a large difference. The distribution of number of family members is 32.3% for a family of 3 and 32.2% for a family of 4. The percentage of homeownership is 59.6%, and the period of residence for less than 10 years makes up the most significant portion with 65.6%. The proportion of marriages is 66.6%, and the ratio of having a job is 86.4%.

4.2. Result of relation between apartment complex and social capital

For residents of single and multifamily housing, the perceptions of social capital according to the area ratio of apartment complexes are as follows (column of single and multifamily housing in ). Residents of single-family and multifamily housing in areas with a high apartment complex ratio had low levels of cooperation with neighbors, community trust, and altruism for vulnerable people at 2.6%, 1.2%, and 1.7%, respectivelyFootnote1 In addition, all factors related to social capital were statistically significant. Among the social capital factors, the level of cooperation with neighbors was the lowest, altruism for vulnerable people was second, and the decrease in community trust was the least. In other words, the larger the area ratio of the apartment complex, the lower the social capital level of the residents of single-family and multifamily housing, who are residents outside the apartment complex.

Table 3. Result for total apartment district ratio of each housing type.

Regarding the social capital of the residents living in the apartment complex, the characteristics are more apparent. For apartment complex residents, the internal residents’ perception of social capital according to the apartment complex ratio is as follows (column of an apartment complex in ). In areas with a high percentage of apartment complexes, the level of cooperation with neighbors and altruism for vulnerable people were higher at 1.0% and 1.9%, respectively. Although the statistical significance of community trust was low, this was 0.8% higher. In other words, as the area ratio of apartment complexes increased, the social capital level of single and multi-family residents decreased, while the social capital level of apartment complex residents generally increased.

4.3. Relation between apartment complex and social capital according to apartment complex scale

We compared the perception of social capital according to the size of the apartment complex by judging that the larger the apartment complex, the greater the negative correlation with social capital. The results of this study are as follows (). As the ratio of the total area of the apartment complex, the size of the apartment complex of 500 units or more, and the size of apartment complexes of 1000 units or more increased, the level of cooperation with neighbors decreased by 2.6%, 5.2%, and 12.8%, respectively. Regarding social trust, as the ratio of the total area of the apartment complex, the size of apartment complexes of 500 units or more, and the size of apartment complexes of 1000 units or more increased, the level of social trust decreased by 1.2%, 2.1%, and 3.9%, respectively. Regarding the altruism for vulnerable people, as the ratio of the total area of the apartment complex, the size of the apartment complex of 500 units or more, and the size of apartment complexes of 1000 units or more increases, the level of altruism for vulnerable people decreases somewhat by 1.7%, 2.5%, and 2.7%, respectivelyFootnote2 As a result, the larger the size of the apartment complex, the more significant the negative correlation it had on social capital, and among the social capital variables, the extent of the decline was most noticeable in cooperation with neighbors.

Table 4. Result for apartment district ratio of middle and large scale.

5. Discussion and conclusion

First, this study showed that apartment communities in Seoul, especially substantial apartment complexes, negatively impact the social capital of neighboring communities, similarly to gated communities: As the area ratio occupied by apartment complexes in an area increased, the level of social capital perception of single-family and multi-family residents around the apartment complex was lower. In contrast, the level of social capital perception of apartment complexes was higher. These results corroborate those of studies that explored whether apartment complexes have similarities to the gated community (Gelézeau Citation2008; Hwang and Kim Citation2020). In particular, this study revealed that social features are similar, unlike the two studies above. Therefore, although not covered in the existing types and case studies of the gated community (Blakely and Snyder Citation1997; Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004), the apartment community in Seoul has similar characteristics to those of gated communities.

To become a healthy local community, the apartment complex should not be an isolated island, but rather should form a community with the surrounding detached and multi-family houses. This study highlights that a system that strictly divides the interior and exterior of an apartment complex as it is now is negative for social capital and harmful for the whole community. We must bear in mind that the current apartment complex plan is favorable for internal social capital, although dangerous for ties with external residents. As a result, apartment complexes need to be considered more deliberately so as to establish housing policies that promote links with neighboring residents through various services for internal solidarity.

Second, this study revealed that the influence of apartment communities on social capital differs for each element of neighbors’ social capital. Existing studies have determined through qualitative literature review and case analysis that the gated community tends to negatively influence social exchanges (Breitung Citation2012; Low Citation2001). This study categorizes social capital by element and demonstrates that apartment complexes are correlated with the social capital of local community residents. Specifically, we analyzed social capital by subdividing it into cooperation with neighbors, community trust, and altruism for vulnerable people. As a result, negative correlations with apartment complexes were different for each type of social capital. Neighbors’ perception of social capital around apartment complexes decreased more for cooperation with neighbors than for community trust or altruism and more negatively affected the altruism for vulnerable people than community trust. As a result, this study supports the conclusions of earlier qualitative research on the negative social effects of the gated community (Davis Citation1992; Etzioni Citation1995; Low Citation2001; Vesselinov, Cazessus, and Falk Citation2007).

Third, this study also showed that the negative correlation of apartment complexes with social capital varies according to the size of apartment complexes. This result adds information on the scale characteristics related to social capital highlighted in research on the effects of the size of the gated community (Grant and Mittelsteadt Citation2004). According to the results of this study, as the size of the apartment complex increased to 500 or more and 1,000 or more, the negative correlations of cooperation with neighbors, community trust, and altruism for vulnerable people were strong. In particular, cooperation with neighbors increased negatively by more than 10% in the model applied to large-scale apartment complexes of 1000 households or more than in the model of all apartment complexes, indicating that the larger the apartment complex, the more negative the social capital of the local community.

It was found that the extent of social capital reduction varied depending on the size of the apartment complex. In particular, among social capital factors, cooperation with neighbors decreased by 5.5% for apartments with 500 or more units and by 12.9% for apartments with 1,000 units or more. In other words, we should recognize that the larger the scale of an apartment complex, the more negatively it impacts the social capital of the surrounding residents. Based on these studies, there is a need for urban planning discussions to induce the construction of apartment complexes below a specific size or to appropriately separate large-scale apartment complexes to relieve physical boundaries.

Furthermore, when apartment complexes dominate residential areas like Seoul, policies and support are needed to improve the sense of community for single and multi-family densely populated areas. As expected through this study, the proportion of apartment complexes will continue to increase, and the social capital of residents living alone or in multiple households will contract accordingly. Besides, apartment complexes supplied by private construction companies will continue to provide community facilities for residents inside the apartment, much as they do now. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss urban planning elements and housing policies that enhance the sense of community and promote social exchange among residents in multi-family residential areas.

This study analyzes neighbors’ perception of social capital according to the area ratio of apartment complexes. However, as a limitation of this study, we did not verify whether the spatial scope of social capital perception of the Seoul Survey coincides with the spatial area of this study. In other words, since the spatial scope of this study was the autonomous district level, the Seoul Survey’s social capital perception might not be based on the autonomous district. There might thus be spatial discrepancies in the data used in this study. Therefore, future research needs a detailed analysis of the social capital of apartment complexes and neighbors through more sophisticated data.

This study has several limitations. As a first limitation, this study did not include factors such as participation, network, and sense of belonging, which are mainly used in measuring social capital. Therefore, the follow-up study would discover more meaningful implications through the aforementioned social capital factors. Second, we could not analyze social capital by dividing it into bonding social capital and bridging social capital as raw data did not separate by type. Thus, it would be worth analyzing social capital according to the social capital types above. Lastly, this study has a method limitation in comparing coefficient values between models in analyzing the relationship between the apartment complex ratio and social capital. When comparing coefficient values, standardized coefficients should be used in one model. However, this study compared coefficient values between models because of the high multicollinearity and the impossibility of calculating standardized coefficients in logit regression analysis. In the future, empirical analysis is needed to supplement these points based on a more sophisticated analysis model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The robustness test results show that the odds ratio is unchanged, and there is a slight change in the standard error and p-value (see Appendix A).

2 The robustness test results show that the odds ratio is unchanged, and there is a slight change in the standard error and p-value (see Appendix B).

References

- Bauer, D. J. 2009. “A Note on Comparing the Estimates of Models for Cluster-Correlated or Longitudinal Data with Binary or Ordinal Outcomes.” Psychometrika 74 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1007/s11336-008-9080-1.

- Berkman, L., I. Kawachi, and M. M. Glymour. 2014. Social Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bible, D. S., and C. Hsieh. 2001. “Gated Communities and Residential Property Values.” The Appraisal Journal 69 (2): 140–145.

- Blakely, E. J., and M. G. Snyder. 1997. Fortress America: Gated Communities in the United States. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Blanchflower, D. G., and A. J. Oswald. 2004. “Well-Being over Time in Britain and the USA.” Journal of Public Economics 88 (7): 1359–1386. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(02)00168-8.

- Breitung, W. 2012. “Enclave Urbanism in China: Attitudes Towards Gated Communities in Guangzhou.” Urban Geography 33 (2): 278–294. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.33.2.278.

- Briggs, X. 2005. Social Capital and Segregation in the United States. Desegregating the City: Ghettos, Enclave, and Inequality, 79–107. New York, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Coleman, J. S. 1988. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120. doi:10.1086/228943.

- Coleman, J. S. 1990. Foundations of Social Theory. Massachusetts, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cresswell, T. 1996. In Place-Out of Place: Geography, Ideology, and Transgression. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Davis, M. 1992. “Fortress Los Angeles: The Militarization of Urban Space.” In Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space, edited by M. Sorkin, 154–180. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

- Devine, J. 1996. Maximum Security: the Culture of Violence in Inner-City Schools. Illinois, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Dixon, J. 2001. “Contact and Boundaries: Locating the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations.” Theory & Psychology 11 (5): 587–608. doi:10.1177/0959354301115001.

- Engle, M. S. 1993. “Mending Walls and Building Fences: Constructing the Private Neighborhood.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 25 (33): 71–90. doi:10.1080/07329113.1993.10756443.

- Etzioni, A. 1995. Rights and the Common Good: The Communitarian Perspective. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- Finkelstein, A., E. F. Luttmer, and M. J. Notowidigdo. 2009. “Approaches to Estimating the Health State Dependence of the Utility Function.” American Economic Review 99 (2): 116–121. doi:10.1257/aer.99.2.116.

- Gelézeau, V. 2008. “Changing Socio-Economic Environments, Housing Culture and New Urban Segregation in Seoul.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 7 (2): 295–321. doi:10.1163/156805808X372458.

- Gittell, R. J., and A. Vidal. 1998. Community Organizing: Building Social Capital as a Development Strategy. New York, NY: Sage Publications.

- Grant, J., and L. Mittelsteadt. 2004. “Types of Gated Communities.” Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design 31 (6): 913–930. doi:10.1068/b3165.

- Guterson, D. 1992. “No Place, Like Home.” Harper’s Magazine, November.

- Harpham, T., E. Grant, and E. Thomas. 2002. “Measuring Social Capital within Health Surveys: Key Issues.” Health Policy and Planning 17 (1): 106–111. doi:10.1093/heapol/17.1.106.

- Harpham, T. 2008. “The Measurement of Community Social Capital through Surveys.” Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S.V., Kim, D. eds. In Social Capital and Health. New York, NY: Springer 51–62 .

- Helsley, R. W., and W. C. Strange. 1999. “Gated Communities and the Economic Geography of Crime.” Journal of Urban Economics 46 (1): 80–105. doi:10.1006/juec.1998.2114.

- Higley, S. R. 1995. Privilege, Power, and Place: The Geography of the American Upper Class. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hwang, S. W., and H. J. Kim. 2020. “The Intensifying Gated Exclusiveness of Apartment Complex Boundary Design in Seoul, Korea.” Planning Perspectives 35 (4): 719–729. doi:10.1080/02665433.2020.1770623.

- Judd, D. R. 1995. “The Rise of the New Walled Cities.” In Spatial Practices: Critical Explorations in social/spatial Theory, edited by H. Liggett and D. C. Perry, 144–166. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Jun, M. J. 2013. “The Effects of Housing Preference for an Apartment on Residential Location Choice in Seoul: A Random Bidding Land Use Simulation Approach.” Land Use Policy 35: 395–405. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.06.011.

- Kan, K. 2007. “Residential Mobility and Social Capital.” Journal of Urban Economics 61 (3): 436–457. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2006.07.005.

- Kang, S., and J. H. Koo. 2020. “Distribution Characteristics and Correlation between Regional Inequality and Social Capital, Seoul, Korea.” Seoul Studies 4 (21): 223–238.

- Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S.V., Kim, D. et al. 2008. “Social Capital and Health: A Decade of Progress and beyond.” Kiwachi, I., Subramanian, S.V., Kim, D. eds. In Social Capital and Health, 1–26. New York, NY: Springer.

- Lang, R. E., and K. A. Danielsen. 1997. “Gated Communities in America: Walling Out the World?” Housing Policy Debate 8 (4): 867–899. doi:10.1080/10511482.1997.9521281.

- Lemanski, C. 2006. “Spaces of Exclusivity or Connection? Linkages between a Gated Community and Its Poorer Neighbour in a Cape Town Master Plan Development.” Urban Studies 43 (2): 397–420. doi:10.1080/00420980500495937.

- Lindström, M. 2008. “Social Capital and Health-Related Behaviors.” Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S.V., Kim, D. In Social Capital and Health, 215–238. New York, NY: Springer.

- Lofland, L. H. 2017. The Public Realm: Exploring the City’s Quintessential Social Territory. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Low, S. M. 2001. “The Edge and the Center: Gated Communities and the Discourse of Urban Fear.” American Anthropologist 103 (1): 45–58. doi:10.1525/aa.2001.103.1.45.

- Low, S. M. 2003. Behind the Gates: life, Security, and the Pursuit of Happiness in Fortress America. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Marcuse, P. 1997. “The Enclave, the Citadel, and the Ghetto: What Has Changed in the Post-Fordist US City.” Urban Affairs Review 33 (2): 228–264. doi:10.1177/107808749703300206.

- Mazumdar, S., V. Learnihan, T. Cochrane, and R. Davey. 2018. “The Built Environment and Social Capital: A Systematic Review.” Environment and Behavior 50 (2): 119–158. doi:10.1177/0013916516687343.

- Narayan, D. 1999. Bonds and Bridges: Social Capital and Poverty. 2167 vols. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Oppenheim, R. 2009. “Valérie Gelézeau, Ap’at’ǔ Konghwaguk [On the Republic of Apartments].” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal 3: 137–145.

- Putnam, R. 1993. Making Democracy Work: civic Traditions in Modern Italy. New Jersey, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone: the Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Sampson, R. J., S. W. Raudenbush, and F. Earls. 1997. “Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy.” Science 277 (5328): 918–924. doi:10.1126/science.277.5328.918.

- Sampson, R. J., D. McAdam, H. MacIndoe, and S. Weffer-Elizondo. 2005. “Civil Society Reconsidered: The Durable Nature and Community Structure of Collective Civic Action.” American Journal of Sociology 111 (3): 673–714. doi:10.1086/497351.

- Shin, H. B., and S. H. Kim. 2016. “The Developmental State, Speculative Urbanisation and the Politics of Displacement in Gentrifying Seoul.” Urban Studies 53 (3): 540–559. doi:10.1177/0042098014565745.

- Sibley, D. 1995. Geographies of Exclusion: Society and Difference in the West. London: Routledge.

- Sonn, J. W., and H. B. Shin. 2020. “Contextualizing Accumulation by Dispossession: The State and High-Rise Apartment Clusters in Gangnam, Seoul.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 110 (3): 864–881. doi:10.1080/24694452.2019.1638751.

- Subramanian, S. V., D. J. Kim, and I. Kawachi. 2002. “Social Trust and Self-Rated Health in US Communities: A Multilevel Analysis.” Journal of Urban Health 79 (1): S21–S34. doi:10.1093/jurban/79.suppl_1.S21.

- Szreter, S., and M. Woolcock. 2004. “Health by Association? Social Capital, Social Theory, and the Political Economy of Public Health.” International Journal of Epidemiology 33 (4): 650–667. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh013.

- Townshend, I. J. 2002. “Age-Segregated and Gated Retirement Communities in the Third Age: The Differential Contribution of Place-Community to Self-Actualization.” Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design 29 (3): 371–396. doi:10.1068/b2761t.

- Vesselinov, E., M. Cazessus, and W. Falk. 2007. “Gated Communities and Spatial Inequality.” Journal of Urban Affairs 29 (2): 109–127. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00330.x.

- Widmer, E. D. 2006. “Who are My Family Members? Bridging and Binding Social Capital in Family Configurations.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 23 (6): 979–998. doi:10.1177/0265407506070482.

- Won, J., and J. S. Lee. 2020. “Impact of Residential Environments on Social Capital and Health Outcomes among Public Rental Housing Residents in Seoul, South Korea.” Landscape and Urban Planning 203: 103882. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103882.

- Yamamura, E. 2011. “How Do Neighbors Influence Investment in Social Capital? Homeownership and Length of Residence.” International Advances in Economic Research 17 (4): 451–464. doi:10.1007/s11294-011-9318-z.

Appendix A.

Results of ordered logit model for robustness test

shows the results of the apartment complex ratio and social capital robustness test for community residents and apartment dwellers. As a result of this robustness test, there was no change in the odds ratio, and there was a slight change in the standard error and p-value.

Table A1. Result of robustness test for total apartment district ratio of each housing type.

Appendix B.

Results of ordered logit model for robustness test by apartment complex scale

shows the robustness test results between the apartment complex ratio and the social capital by apartment district size. As a result of this robustness test, there was no change in the odds ratio, and there was a slight change in the standard error and p-value.

Table B1. Result of robustness test for apartment district ratio of middle and large scale.