ABSTRACT

Post-independence architects of Sri Lanka practicing after 1948 reinterpreted outdoor transitional spaces such as verandahs and courtyards integral to traditional houses, which were multifunctional living and circulation spaces that created physical and social interactions and thresholds. This paper considers four selected precedents: two case studies of single-unit urban house designs of pioneering Sri Lankan architects with modernist influence as examples for 1950s and 60s houses in comparison with two case studies of traditional house types. The study explores the change in spatial patterns through graphical analysis of plan forms to understand the shift in socio-spatial role. In post-independence Sri Lankan modernist houses, the multifunctional role of semi-outdoor spaces common to traditional houses changed to a single function in most spaces with fewer connections to other living areas. Outdoor spaces, previously free and undefined, were incorporated in the house with designated functions from gardens to lightwells to utility. Compared to the traditional typologies, the modernist influenced urban house examples exhibit a considerable change in spatial patterns affecting the socio-spatial role of outdoor transitional spaces.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research aims and significance

Post-independence period in Sri Lanka witnessed new housing policies and ideas. The post–World War II era coincided with an important milestone in Sri Lankan history – Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) gained independence from British rule in 1948. Architects practising in Sri Lanka during this time mainly were Western-educated Sri Lankans or foreign nationals. Until 1961, an architecture course was unavailable in Sri Lanka; in 1971, a degree in architecture was offered by the University of Ceylon. Post-independence nationalist movements saw the reinterpretation of tradition in art, music, drama and literature. However, early examples in residential architecture did not follow this trend; Sri Lankan architectural historians and scholars attribute this to the architects’ educational background and exposure to the western world and modernist thinking popular at that time (N. de Silva, personal communication, 18 January 2021). Architects needed to break from colonial house typologies imported from abroad and inspired by European culture, which were considered unsuited to Sri Lankan living patterns and climatic conditions. They were eager to experiment with new designs that represented the newly formed social classes and urban living of independent Sri Lanka.

This paper explores modernist and postmodernist influences on the design of outdoor transitional spaces in Sri Lankan houses during the early post-independence period (1948–1970). Modernist-inspired early buildings in urban areas were considered a creative, modern approach to single-unit urban house design for limited plot sizes. This approach was the antecedent for space organisation in contemporary urban houses designed by practising architects as well as architecture students. Understanding how different spatial types and spatial relationships were introduced to Sri Lanka will pave the way for evaluating the spatial patterns and socio-spatial role of outdoor transitional spaces in contemporary urban houses. This information will help architects understand the usability of specific spaces, recognise spaces that generate social interaction and minimise redundant spaces.

1.2. Research methods

Outdoor transitional spaces like verandahs and courtyards were present in traditional Sri Lankan residential buildings since the third century BCFootnote1 and continued throughout the colonial period with some adopted typologies. These spaces responded well to the climate and addressed Sri Lankans’ living patterns and social structure: “traditionally, people of Sri Lanka lived around the house and not inside the house” (N. de Silva, personal communication, 18 January 2021). Verandahs were also used as tools for zoning within the house according to the social structure and the occupants’ living patterns; verandahs played a significant role as a social threshold and acted as mostly used primary living space (Coomaraswamy Citation1956; de Silva Citation1990; Lewcock, Sansoni, and Senanayake Citation2014; Perera Citation1996). Oliver’s (Citation2003) study on vernacular architecture and Rapoport’s (Citation1969, Citation2005) investigations on environment behaviour studies highlight different cultures’ social structure, traditions and living patterns expressed through their domestic spaces. Considering these key concepts, this study focuses on the plan form of house typologies to explore the change in socio-spatial role of outdoor transitional spaces. Based on Oliver’s and Rapoport’s writings, the social and cultural use of a space is considered as the socio-spatial role of that space for this research.

This study evaluates the influence of modernist and postmodernist theories and approaches to post – World War II housing strategies in the western world. It highlights the key concepts and works that influenced the creation of outdoor transitional spaces. Understanding this background influence is important since the Sri Lankan pioneering architects of 1950s and 60s had their education and work exposure in the western world. Through a survey of the historical literature, the basis of Sri Lankan historical typologies was established as an ideal solution to address the climate and represent sociocultural norms. The early work and inspirations of pioneering post-independence architects are explored through interviews with the architects and their written memoirs; other scholars’ interpretations of the architects’ work are studied through interviews and their writings.

A comparative graphical analysis is carried out on the plan form of four single-unit house types to examine their spatial patterns and resulting socio-spatial role. Two main historical typologies of traditional houses established by scholars (Coomaraswamy Citation1956; de Silva Citation1990; de Vos Citation1988) were chosen as the starting point for post-independence experiments. Two early post-independence examples of urban houses by pioneering architects Minnette De Silva and Valentine Gunasekara provided examples of the approaches to modern regional architecture (De Silva Citation1998; Pieris Citation2007; Robson Citation2015). A graphical analysis of plan form on the use of space, number of connections and spatial connection patterns of outdoor transitional spaces are considered to explore the socio-spatial role generated.

1.3. Historical background

Two main house typologies can be detected in traditional pre-colonial houses in Sri Lanka based on their geographic location and climatic conditions: the extroverted verandah house in warm and humid lowland areas and the introverted courtyard house in the hilly, central region with a cooler climate. In the central region, where the climate was cooler and wet, the open space was brought inside the house as a courtyard with verandahs opening to the courtyard, creating semi-outdoor living spaces.

Sri Lanka had three colonial periods according to various rulers starting with the PortugueseFootnote2 (from the early sixteenth century to the mid-seventeenth century), then the DutchFootnote3 (from the mid-seventeenth century to the late eighteenth century), and finally the BritishFootnote4 (from the late eighteenth century until independence in 1948). The colonials mostly continued the traditional house forms but reinterpreted the layouts to suit their lifestyles. During the British period, more compact versions were introduced to cater for the increasing demand for smaller houses on smaller plots. Public Works Department (PWD) bungalowsFootnote5 built to house British government workers introduced a new foreign typology: “a compact and self-contained box with steep-hipped roof and incorporated service spaces” (Pieris Citation2013, 122). These imported house types were not addressing climatic or socio-cultural requirements of the country. This was one of the reasons for modernist influenced architects of early post-independence to explore designs for new urban house types with traditional outdoor transitional spaces re-interpreted to suit the time and context.

2. Postwar architecture, urban theories and transformation of city social spaces

2.1. Postwar reconstruction in the Western World

The end of World War II in 1945 left many cities in ruins and reshaped the geopolitical map. The immediate, enormous task to rebuild the cities, reinvigorate a shaken international community and restart the economy of affected nations defined the new sociocultural background. In the aftermath of the war, there was tension between urgent reconstruction and the necessity for planning, especially in Europe (Benevolo Citation1971).

The architectural and urban theories developed from the early 1920s were permeated with strong social reform intent, refined and codified at the various meetings of the Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) during 1928–1933. This work sets the theoretical agenda for the Modern Movement’s influential design language. Key radical concepts were diffused and emerged as distinctive features of architectural and urban design. Le Corbusier’s fixation on the idea of tabula rasa in redesigning old districts and the rejection of historical styles and decorations in architectural forms exemplified the rejection of history and local traditions (Hughes Citation1991, 188). There was a predilection for the unadorned and pure shapes taken from an infatuation with the mechanical world and industrial production of goods and new material. There was an emphasis on new building types and the mass production of standardised construction elements for the large-scale mass housing complexes. The new style was characterised by providing a healthy environment with green spaces open to the air and the sun and a sense of order, lightness and efficiency.

Modern architecture became the primary language of architects from the late 1940s. However, Europe and the United States (US) took modern architecture in different directions due to their different political conditions. The welfare state economy was predominant in Europe, and private agencies in the US pursued aggressive liberalism less bound by ideological drives (Colquhoun Citation2002).

In the US, which escaped the destruction of its cities during WWII, modernism became a celebration of the corporate capitalist system, expressed in new urban office skyscrapers and other commercial and administrative buildings (Ghirardo Citation1996). The modernist forms introduced by European masters who fled Europe before WWII were freed from any social and revolutionary intent; they expressed in architectural language the values of large capitalist corporations. The US federal government increased its spending on new infrastructures (e.g., interstate freeways and highway networks) and the launch of extensive programmes for the urban renewal of old downtowns in its major cities. Built around the idea of integrating personal freedom and mobility, automobile ownership (at the expense of public transport) and mass motorisation became the distinctive elements of the modern American urban and regional landscapes. Consequently, the spatial form of cities and towns was drastically transformed into urban sprawl. Suburbanisation and dispersion became features of American urbanisation. This sprawl was driven mainly by the economic stimulus for infrastructure improvements, subsidised housing projects following the veterans’ return and the mass production of consumer goods by the reinvigorated industrial system.

On the European continent, postwar urban reconstruction was driven by the urgent need to rebuild cities and restore local economies. Welfare states undertook centralised planning for public works for new infrastructure and mass housing. Construction relied on innovative technologies for prefabricated construction systems to produce residential units as social housing. Designs reflected the research undertaken in the prewar years mainly by a generation of architects that embraced rationalism. In this period, architectural design and urban theories were characterised by a robust socio-ideological stance focused on collective housing typologies.

However, there was growing controversy concerning preserving older structures versus fulfilling the needs for new urban spaces and housing stocks. The loss of neighbourhoods with their consolidated social fabrics and the demolition of historical buildings, erasing local memories and temporal continuity, alarmed the most sensible representatives of the architectural practice. Many questioned key principles of modern city design embodied in the four urban functions prescribed in the Athens Charter (1944). The dullness, abstractness and monotony of the architectural form of many new housing complexes, paired with their disregard for the population’s needs and the social interaction of urban dwellers, prompted vocal criticism. Attentive observers and activist professionals such as Jane Jacobs in the US and members of Team 10 in Europe asked for architecture with a sense of surprise, variety and human scale expressing the complexity of the city, and pervaded by a sense of belonging and identity.

2.2. Team 10 and the focus on social places in the city

In the early postwar years and the 1950s, with the collapse of the British Empire, British architects and planners engaged in the design and development of several new towns. This development was an unprecedented attempt to decentralise urban activities and functions and disperse the population at a regional scale, following Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City ideas. Multiple vast slum clearance projects resulted in the demolition of old buildings, the destruction of entire social networks and the erasure of centuries of history. The lack of character, the sameness of the built urban environment and the upsurge in social problems in the new collective housing developments prompted a significant reaction from Team 10 (the group that organised the tenth CIAM meeting in Dubrovnik in 1956). These young architects established a new research agenda for change, mobility, cluster and growth that influenced international architecture and urban planning discourse in subsequent years.

The contribution of founding members of the Team 10 group, the young British architects Peter and Alison Smithson, was particularly notable. They later promoted the language of New Brutalism and innovative paradigms for smaller-scale community design responsive to people’s way of life as liberation from the strict canons of the International Style. Formerly affiliated with the Modern Architecture Research Society (MARS), the English branch of the CIAM, the Smithsons progressively dissociated themselves from the orthodoxy of modernism and promoted different ideas on city design. Their research shifted attention from urban form designed according to the four canonical CIAM functions of living, circulation, working and entertainment towards the importance of social community and the need for human connections in architecture inspired by the concept of “human relations” (Smithson Citation1968, 76–79). In their installation Re-identification Grid and Golden Lane project (Citation1953), the Smithsons overcame the abstract organization of the plan typical of Modernist design and instead focused on the network of human associations in the city. Their hierarchical system of “House, Street, District and City” indicated concrete defining elements for designing the physical urban form and was a new source of architectural design inspiration.

The Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck, another member of the Team 10 group, also pursued research focused on mutual relationships among single elements within larger and more complex built systems. He regarded the nature of social association as a fundamental tool for structuring the space beyond the rigid compositional forms of the functional division of the built environment posited by modernism. Clarifying the meaning of sense of place in architecture, as a spatial configuration with significance and meaning, van Eyck’s research on the social meaning of urban areas was progressively refined during years of designing playgrounds, the favourite urban location of children within the community. The Nagele Village Grid (1956) and the Amsterdam Municipal Orphanage (1955–1960) projects epitomise his attention to human scale, calibrating sequence of spatial units and public space for social aggregation to foster human association and interaction aligned to his notion of integrated space with “labyrinthine clarity” (Frampton Citation2007, 276). In these inherently social projects, where the design considers the inhabitants’ actual use of the space (whose activities generate the physical form), van Eyck combined a hierarchical spatial organisation structured on the precise positioning of communal areas interconnected with more private corners. The designs incorporated calibrated sequences of areas between spaces, defined by clear edges and thresholds, that worked together to form and support a greater sense of place. In many subsequent projects, van Eyck conceived a house like a small city to highlight the importance of responsive and dedicated communal areas for social interaction and circulation. He transplanted this vision to the design of high-density housing complexes and within the organization of the apartment’s unit. In particular, van Eyck stressed the vital function of the spatial edges connecting neighbourhoods and the in-between spaces of public areas and private buildings. He saw boundaries as key elements for regulating the relationships within architectures and urban spaces and defining the sense of place.

The work of van Eyck and the Smithsons reflected the broader influence of structuralism in architecture and urban planning, which arose in the 1950s and 1960s and was rooted in linguistics and anthropology. Structuralism concerned the laws regulating the functional and spatial relationships among units in larger systems and their interconnections linking the totality and parts. Structuralist architects understood large-scale and complex architectural and urban design not as static and deterministic processes but in terms of structuring and regulating the functional and spatial systems formed by the relationship between built elements in time and space. Form was separated from the plain function, and polyvalent form was introduced to integrate physical buildings and the sociocultural networks populating them (Luchinger Citation1980, 67). Structuralists conceded that the social structure mainly generated the design process and the organisation of the urban forms. The design process was affected by multiple agents and conditions linked to the physical habitat, local climate, cultural context and historical human environment. The rediscovery of the importance of local traditions and specific cultures and acknowledgement of their role when designing the built environment prompted a major shift from modernist paradigms and the transition towards regionalist architectural and urban planning in the decades that followed within Europe and beyond.

3. Western exposure and interpretation of modernism in Sri Lanka

3.1. MARG magazine in India and connections to CIAM meetings

Developments in architecture in non-Western countries were never a concern for CIAM or Team 10; however, they contributed towards debate in the late 1950s and 1960s.Footnote6 The Indian magazine MARG was founded in 1946 by the Modern Architectural Research Group (which modelled itself on the British MARS group). Marg means “pathway” in Hindi. MARG endorsed international modernism in architecture as the way to achieve better living conditions for all Indians () published the Athens Charter and gave substantial coverage to Le Corbusier’s design for Chandigarh in its issues from 1953 to 1963 (Marg Citation1946, 7−16; Lee and James-Chakraborti Citation2012, 9–10). Sri Lankan architect Minnette De Silva, a founding member and an architectural editor of MARG, introduced and presented the publication at the CIAM meeting in 1946 (). Another founding member of MARG, the architect and planner Otto Koenigsberger (a native German working in India) developed low-cost architecture that suited the specific place, derived from the local cultural needs, responded to environmental conditions, and used existing building materials and forms. Sri Lankan architect Minnette De Silva worked with Koenigsberger in India. Her approach to architecture in Sri Lanka displayed Koenigsberger’s thinking of being responsive to local climatic, economic and social needs and also reflected ideas of Team 10 on sense of belonging and identity. MARG featured De Silva’s Karunaratne House and described it as “an experiment in modern regional architecture in the tropics” (De Silva Citation1953, 4). At CIAM meetings from 1946 to 1957, De Silva called herself the delegate representing India and Ceylon (Lanka) (De Silva Citation1998).

Figure 1. Excerpts from Marg Magazine.

3.2. Modernist propagations of London’s Tropical School of Architectural Association

The pioneering modernist architects of Sri Lanka, Minnette De Silva, Geoffrey Bawa and Valentine Gunasekara, were products of the Architectural Association (AA) School of Architecture in London. The approaches to teaching architectural design of the academics who joined the AA in London, like Ranjith Alahakoon and Chris de Saram, influenced the younger generation of architects in Sri Lanka.

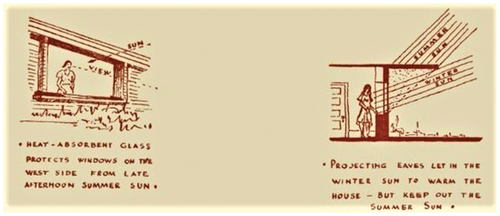

After World War II, the AA became internationalised. AA staff, including leading young British modernists such as Peter Smithson, formed the Department of Tropical Architecture in 1954 (the Department of Tropical Studies from 1961). The department was believed to offer more opportunities to practice modernism in colonies with tropical climates. Otto Koenigsberger led the department and founded climatically responsive architecture (AA Archives Citation1851). In the 1950s, the teaching and conferences of AA’s Department of Tropical Architecture defined tropical architecture as climate-responsive design practice: “Architects debated the efficacy of simple low-impact technologies and vernacular architecture. Koenigsberger developed Tropical Architecture as a critique of Euro-centric architectural and planning paradigms” (Baweja Citation2008, 133). Sri Lankan architects Bawa and De Silva applied the department’s teachings in their approach to architecture – they explored vernacular architecture for responding to climate and living patterns. Although Gunasekara did not propagate taking vernacular as a reference, he extensively used outdoor and semi-outdoor spaces in his house designs.

3.3. Post-Independence Sri Lankan architecture from 1948

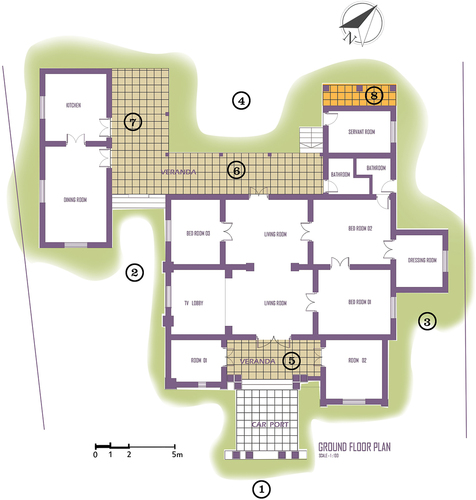

During the 1950s and 1960s, the internationalism of modernism was considered a tool for resisting the prevailing colonial British styles. Sri Lankan architects were conscious of traditional living patterns; however, their inspiration from modernism provided endless opportunities to create architectural masterpieces that sometimes overshadowed society’s sociocultural needs. After studying and working in the US, Valentine Gunasekara came to Sri Lanka and used American sources for his inspiration. Californian modernism was his point of origin with its freedom of spaces and modular articulation (Pieris Citation2007, 13). Gunasekara introduced the roof terrace into his house designs – a new space in the Sri Lankan context. He believed that a roof terrace as a habitable space would open the views of the sky, including sunrise and moonrise. Gunasekara encountered Richard Neutra and worked in Eero Saarinen’s office. Neutra’s house at Silver Lake, which maximised the views and extended the architectural space into the landscape, appealed to Gunasekara (Pieris Citation2007). Believing that the steep pitch of the traditional roof obstructed the views, he used low-pitched or flat roofs, opening the house into surroundings. Gunasekara’s urban houses expressed blank facades to the street to create privacy. He made garden spaces into courtyards with horizontal pergolas to secure them and protect them from the sun and rain. Gunasekara’s Illangakoon House, Colombo 7 (1969), was designed as a sculpture inside a square box. Rather than organising spaces around a central courtyard, with his modernist influence, he designed it as a free volume wrapping around multiple courtyards interrupted by vertical and horizontal connections (Pieris Citation2007, 63−66; Robson Citation2016, 177) (). Contrary to this, his Jayakody House in Nawala, Colombo suburb (1959–1960), was designed as an elongated two-storey pavilion with full height, glazed folding windows making the whole façade open into the garden (). According to Pieris (Citation2007, 54), “it was also symptomatic of the renewed interest in Japanese architecture at that time”. The house did not include semi-outdoor transitional spaces but created the option to fully open the living areas to the garden to simulate semi-outdoor living.

Figure 4. Plans of Illangakoon House (1969) by architect Valentine Gunasekara in Colombo 7.

Figure 5. Courtyard with pergola on top - Illangakoon House (1969).

Figure 6. Plans of Jayakody house (1959–60), by architect Valentine Gunasekara in Nawala, Colombo suburb.

Figure 7. View of living area – Jayakody house (1959–60).

Senior architect and academic Ranjith Alahakoon explains that his exposure to architecture in Denmark in the 1960s and his travels in Europe influenced his approach to the outdoor and semi-outdoor spaces of the houses he designed (R. Alahakoon, personal communication, 26 January 2021). He recalls visiting Jørn Utzon’s housing complexes in Denmark and states that this exposure would have influenced him subconsciously. Two of Utzon’s housing developments, the Kingo Houses (1956) and the Frendensborg Houses (1959–1965), were designed as courtyard houses, showing his exposure to Chinese courtyard houses (Chiu et al. Citation2020). In response to small plot sizes and climate, Alahakoon incorporated courtyards as garden spaces into the house by extending the building envelope to the boundary wall and opening them completely into internal spaces to provide more light into the house. However, he states, “Whether I answered the lifestyle here, I am not sure” (R. Alahakoon, personal communication, 26 January 2021).

Andrew Boyd (British) and Ulrik Plesner (Danish) were two architects whose work introduced new approaches to house design in Sri Lanka. Plesner’s projects reflected subtle references to Sri Lankan vernacular traditions based on his ideas of humanization of architecture and also the simple abstract functionalism of Scandinavia (Pieris Citation2013; Robson Citation2007). In his twin houses in Colombo, Boyd introduced new design elements to create compact functionalist houses with continuous first floor balconies and asymmetric roofs with clerestory ventilation (Robson Citation2015). Balconies with large windows opening into them and short eaves, representing Western modernist influence, did not provide protection from tropical climatic conditions as given by steeply pitched traditional roofs with their long eaves – this affected their usability as living spaces.

3.4. Minette De Silva and modern regional architecture

Architecture historian and critic Frampton (Citation1983, 148) noted that “critical regional expression is not only sufficient prosperity but also a strong desire for realising an identity”. Frampton (Citation1983, 149) discussed Catalonian nationalist revival as an example, where the group led by J. M. Sostres and Oriol Bohigas was obliged to revive the rationalist, anti-fascist values and procedures of GATEPAC (the prewar Spanish wing of CIAM). According to Lara (Citation2009, 48), “in Latin America, and Brazil in particular, modern architecture achieved a distinct identity”. Architects such as Oscar Niemeyer, Carlos Leao, Affonso Reidy and Burle Marx took the tropical offspring of modernism to a different level to create an identity with their adaptation of modern elements applied in middle-class houses during the 1950s and 1960s (Lara Citation2009, 43). Although there were no specific activists promoting modern regionalism, Sri Lankan architect Minnette De Silva propagated parallel ideas at CIAM meetings and explored them through her work from the 1950s.

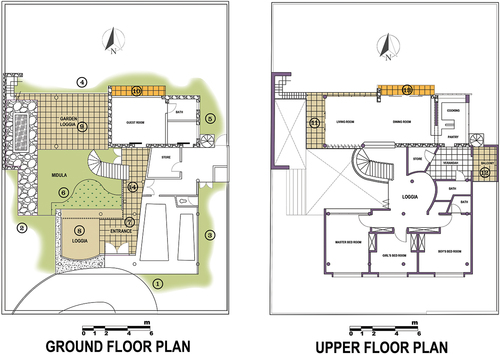

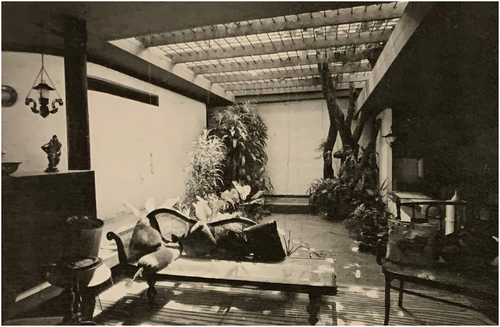

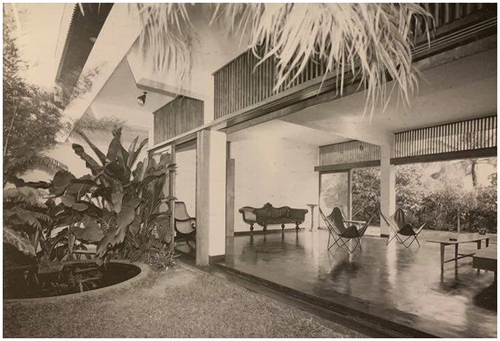

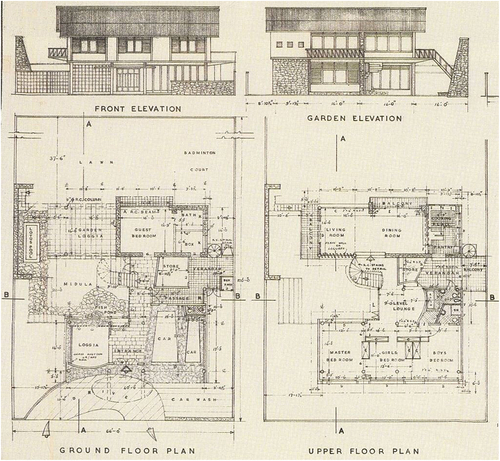

In her approach to architecture, De Silva (Citation1998, 117) responded to the tropical climate and the local lifestyle: “we are a gregarious people, hence space must be expandable”. Combined with modernist principles, she introduced flexible open-plan interiors with moveable walls. She called her approach to architecture Modern Regional Architecture. From her exposure at AA in London, de Silva considered climate responsiveness a prime architectural concern. Pieris House, built 1952–1953, is representative of her interpretation of an urban house with high walls enclosing the garden, courtyards (midulas) becoming open-air rooms, garden areas as extensions of the house, a place for games, a place for sitting outside and an enclosure for open-air bathing – all spaces integrated into one. The house’s main living areas were raised from the ground on pilotis, creating semi-outdoor living areas on the ground level termed loggia (). In this regard, De Silva may have been influenced by her close associate Le Corbusier. De Silva responded to the social needs of people and this concern was shown in her Watapuluwa housing scheme in Kandy, of which she said, ‘I was determined to place primary emphasis on the “users” of the scheme” (De Silva Citation1998, 207).

Figure 8. Floor Plans of Pieris house, Colombo 7 (1953), by architect Minnette De Silva.

Figure 9. Photo of the Loggia of Pieris house (1953).

3.5. Tropical modernism and Sri Lankan interpretations

Tropical modernism applied modernist design principles while responding to the tropical climate. According to le Roux (Citation2003, 337), “tropical architecture has been represented as a form of critical regionalism”, presenting a language to suit tropical climatic conditions. Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa, also a product of AA, is considered an original proponent of tropical modernism in Sri Lanka. He took a close interest in the discussions in the Tropical School promoted by Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew (Robson Citation2002). Inspired by architect Mies van der Rohe, Bawa’s Upali Wijewardene House (1959) is a simple modernist structure comprising a framework and brick infill panels with living spaces built on the first floor around internal courtyards and access to an upper floor terrace (Robson Citation2007). Senior architect, architectural historian and academic Channa Daswatte, who worked extensively with Geoffrey Bawa, noted that Bawa’s early house designs followed a functional plan, no decoration other than the materials he used and a concrete frame structure to create free spaces below (C. Daswatte, personal communication, 9 February 2021). According to Daswatte, Bawa turned the courtyard from the traditional utilitarian space into a social space and reinterpreted the verandah as a living space rather than a threshold.

4. Typologies of traditional Sri Lankan single-unit houses

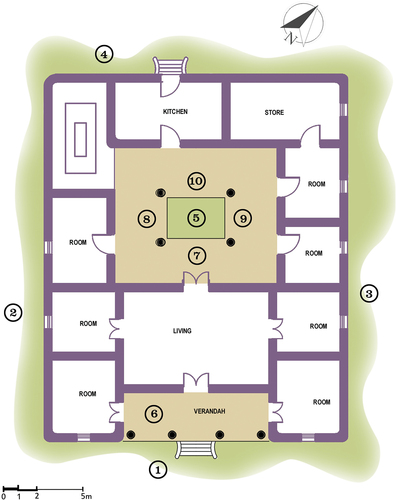

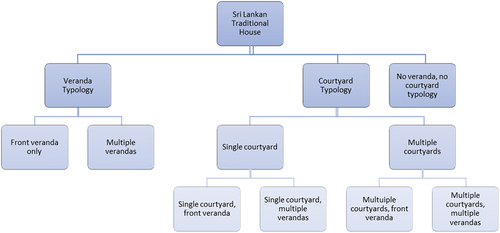

As established previously, there were two main generic traditional house typologies based on outdoor transitional spaces in Sri Lanka – the extraverted verandah house and the introverted courtyard house. There was a minor third typology with no verandah and no courtyard that was only found in clergy residences. There is no clear evidence about their origins but may date back to early civilizations in third century BC. Following diagram () shows the variants of two main typologies.

Figure 10. Variants of Sri Lankan traditional house based on outdoor transitional spaces.

Traditional house types in Sri Lanka included front, back and internal verandahs wide enough to be living spaces. Houses had single or multiple courtyards depending on family size and the owner’s social ranking (Perera Citation1996). Astrological beliefs of different pada (parts of a land with meanings) were a basis for house layouts. The centre of the house is on Brahma pada, which is not meant for people. Therefore, the centre was kept open and became a courtyard for light and ventilation not meant for permanent living (). Outdoor areas around the house were free and multifunctional and created opportunities for casual social interactions.

Figure 11. Plan of a traditional courtyard house from 18th century - Mipola Walawwa, Matale, Central region of Sri Lanka.

Figure 12. Section X-X of Mipola Walawwa.

European colonial rulers adapted traditional house types to suit their living patterns before introducing imported type plans. The introduction of the sala, the living room, brought living and entertaining activities into the house. Sleeping was removed from the verandah; however, the verandah continued as a place for relaxing and entertaining guests. The rear verandah was a service and a utility space used mainly by household staff.

Some suburban houses during colonial period followed the traditional verandah typology, with the front verandah partially covered with newly introduced trellis work or a porch (used as a carport) providing more privacy. The plan forms adopted “U” and “L” shapes with rear verandahs opening into a service yard ().

Figure 13. Plan of an extroverted verandah house typology with British influence (rebuilt in 1920s) - Wijayatunge House in a highly urban context of Kiribathgoda, outskirts of Colombo.

5. Evaluations and conclusions

5.1. Graphical analysis

Background research elaborates how the Sri Lankan pioneering architects of 1950s and 60s were exposed to the architectural debates and themes of western Post–World War II era. Architects like Minnette De Silva were actively involved with the debates that took place at CIAM meetings. They were eager to use modernist design principles to create new spatial experiences. However, being familiar with the Sri Lankan climate and socio-cultural needs, they explored already prevailing traditional house typologies for spatial requirements. Sometimes endless design possibilities of modernist architecture overtook the societal needs. The roof forms changed, and the houses looked modern and very different from traditional typologies. An important question that needs to be answered is whether the spatial patterns of outdoor transitional spaces changed, and this affected the socio-spatial role of those spaces.

In order to answer the above, a comparative study has been carried out using four case studies of houses – two traditional and two modernist influenced to explore the change in spatial patterns of outdoor transitional spaces using a graphical analysis of the plan form. The contribution of the outdoor transitional space to living patterns, connectivity, use of space and its role as a threshold is examined.

The two selected case studies of traditional houses are a courtyard house typology with external and internal verandahs () and a verandah house typology with British colonial influence (). These are considered as important examples since they were the precedents used by modernist architects while exploring new designs to suit the climatic and socio-cultural needs of the country (De Silva Citation1998; Robson Citation2002).

There were many modernist-inspired houses designed by pioneering architects in 1950s and 60s. The following list in outlines some of the most known examples built in Colombo, the capital city of Sri Lanka.

Table 1. List of some most known modernist houses built in Colombo in 1950s and 60s designed by pioneering architects of that period.

Two modernist houses are selected as case studies from the above list. Both are urban houses built in Colombo, where outdoor transitional spaces are actively used. De Silva’s Pieris house was taken as one case study since it is one of the earliest modernist houses in Colombo (). Gunasekara’s Illangakoon house is taken as the second case study as the house is designed following spatial experiences used by modernist architects ().

Four Case Studies

House 1: Mipola Walawwa, Matale (eighteenth century), an introverted traditional courtyard house typology from the central region in Sri Lanka ()

House 2: Wijayatunge House (rebuilt in the 1920s), an extroverted verandah house typology with British colonial influence from a highly urban setting in Kiribathgoda, outskirts of Colombo ()

House 3: Pieris House (1952–1953), a post-independence, modernist-influenced house, designed by architect Minnette De Silva, in Colombo 7 prime residential area ()

House 4: Illangakoon House (1969), a post-independence, modernist-influenced house, designed by architect Valentine Gunasekara, in Colombo 7 prime residential area ()

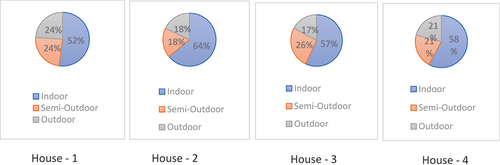

Although Houses 2, 3 and 4 have fewer outdoor and semi-outdoor spaces, they are within equal range to House 1 (see ). The two post-independence houses although have different plan configurations, they too followed the concept of providing outdoor and semi-outdoor spaces as integral parts of the house.

Figure 21. Analysis of number of outdoor, semi-outdoor and indoor spaces as a percentage of total number of spaces.

As shows, there are considerable differences in the use and connections of semi-outdoor spaces in Houses 3 and 4 compared with Houses 1 and 2. The use of space and the number of connections in Houses 1 and 2 are similar, with almost all acting as multipurpose living and circulation spaces. Most spaces in Houses 3 and 4 have only one function, which varies from living to circulation to utility to a climate-responsive element; this demonstrates the introduction of a new living style and change in the socio-spatial role. Some semi-outdoor spaces of House 3 have fewer connections, which may affect their usability. However, House 4 has high connectivity in most spaces making them highly usable.

Table 2. Analysis of relationships based on use and connections of semi-outdoor spaces.

shows that all four houses used semi-outdoor spaces for zoning. In Houses 1 and 2, all semi-outdoor spaces are primarily connected to living or activity spaces and, therefore, acted as a threshold. In Houses 3 and 4, many semi-outdoor spaces are connected to separate circulation spaces thus, shifting its multifunctional role and transferring the role of being a threshold to another space. Following traditional patterns, semi-outdoor circulation spaces act as thresholds in House 4 and contribute to the zoning of the household workers’ area. However, they are not wide enough to be living spaces.

Table 3. Boundaries: zoning and threshold.

The initial analysis showed that although the general spatial patterns of outdoor transitional spaces of Houses 3 and 4 changed, some patterns continued. The number of outdoor and semi-outdoor spaces provided remained in the same range and semi-outdoor living spaces were reinterpreted generating a new living style but highlighting the continuation of traditional concept of living around the house.

5.2. Conclusion

Since the national independence in 1948, Sri Lankan architects have explored and implemented modernist theories while responding to local climate and sociocultural needs. Government-initiated housing schemes and some private developments continued with colonial prototypes, albeit with reduced sizes to suit the smaller plots. However, pioneering architects explored outdoor transitional spaces for space organisation in urban houses by incorporating and redefining traditional elements such as courtyards and verandahs.

Reinterpreting the traditional spaces in a modern way introduced new types of outdoor and semi-outdoor spaces adapted from Western countries and considered more suitable for urban living. These adaptations included flat roofs as roof terraces, courtyards as internal gardens, upper floor balconies and terraces functioning as verandahs, open-plan houses opening into courtyards and verandahs converted to loggia. All such adaptations were new to Sri Lanka. Some were sensitive to Sri Lankan living patterns and cultural norms, whereas others reflected modernist interpretations that required changes to living patterns. In traditional houses, semi-outdoor spaces were multifunctional living and circulation spaces that also acted as thresholds. Modernist houses exhibited a different socio-spatial role to traditional houses. The major difference in modernist interpretations was that the semi-outdoor space tended to have a single function as either a living or a circulation space and did not always act as thresholds.

It is true that some limitations of Modernism lessons transplanted in Sri Lanka resulted often in a critical adoption of rational and pure geometrical forms and a widespread anti-traditional stance expressed as insensitivity to local culture and history. This in turn encouraged the design of buildings that looked uniform and alien to the context, replicating an approach that was largely present in other neo-independent nations at the time of the end of colonial rule. Nevertheless, it can be argued that modernity of architectural expression as a unifying element representing the progress of newly independent nations was the catalyst for economic and social modernization of postcolonial ear. In Sri Lanka, it generated a welcoming shift for the newly formed urban socio-economic classes. While this study has highlighted some important considerations on the outdoor transitional spaces in Sri Lankan houses such as its connectivity, use, position and resulting socio-spatial role, further research exploring spatial patterns will pave the way to understanding the usability of newly introduced and reinterpreted spaces and their suitability for urban living in Sri Lanka.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Deepthie Perera

Deepthie Perera is currently a PhD candidate at School of Built Environment, University of New South Wales (UNSW Sydney), Australia. She holds an MSc and a PG Dip in Architecture from the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, UK. Previously, she has been a lecturer at Schools of Architecture in Manila, Philippines and Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Raffaele Pernice

Raffaele Pernice is an architect and senior lecturer at the University of New South Wales (UNSW Sydney), Australia. He received a PhD in Architecture from Waseda University in Tokyo and an M.Arch from the University IUAV of Venice in Italy. Dr Pernice has extensive research and teaching experience in Australia, East Asia and the Middle East. His interests and activities lay at the nexus of architecture and urbanism, ranging from design practice through to the theory and history of architecture and city planning.

Notes

1 Evidence of earliest residential buildings in Sri Lanka found in two large monastic complexes of Jetavana and Abayagiri in Anuradhapura dates to third century BC. The complexes consisted of individual monks’ units (kuti) arranged around a central court; they had a square plan built on a podium, which acted as a small verandah (pila) (Nakagawa Citation1991; Prematilleke Citation1994).

2 The first Portuguese contact with the Sri Lankan kings of Kotte Kingdom (near Colombo) occurred 1505–1506; the Portuguese established their rule in the coastal belt of Sri Lanka (de Silva Citation2014).

3 Negotiation conducted between the Dutch and then powerful King Rajasimha II of Kandyan Kingdom concluded in 1638, with the primary objective of expelling the Portuguese. The Dutch took over the coastal bases held by Portuguese and ruled for approximately 150 years (de Silva Citation2014).

4 The British gained control of Dutch possessions in Sri Lanka in 1795 (de Silva Citation2014). Kandyan Kingdom was captured by the British in 1815, and they subsequently ruled the country.

5 The PWD built bungalows in different plan configurations based on designs to house British civil servants. These houses were more enclosed, surrounded by a garden, and verandahs were treated more like windowless rooms (Pieris Citation2013, 121–123).

6 One of the main concerns of Team 10 was to reconsider the relationships of people and their living styles (Charitonidou Citation2019).

References

- AA Archives. 1851. “Records of the Architectural Association Inc.” Great Britain. Architectural Association Archives. https://www.aaschool.ac.uk/aaschool/

- Baweja, V. 2008. “A Pre-History of Green Architecture: Otto Koenigsberger and Tropical Architecture, from Princely Mysore to Post-Colonial London.” PhD Diss., University of Michigan, USA.

- Benevolo, L. 1971. History of Modern Architecture. Translated by H. J. Landry, 3rd ed, Vol. 2. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press.

- Charitonidou, M. 2019. “An Action Towards Humanization. Doorn Manifesto in a Transnational Perspective.” In Paper Presented at the Revisiting the Post-CIAM Generation: Debates, Proposals and Intellectual Framework. Porto, Portugal: FCT

- Chiu, C.-Y., P. Goad, P. Myers, and C. Yilgin. 2020. “Ideas and Ideals in Jorn Utzon’s Courtyard Houses: Dwelling, Nature, and Chinese Architecture.” The Journal of Architecture 25 (5): 513–557. doi:10.1080/13602365.2020.1788115.

- Colquhoun, A. 2002. Modern Architecture. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Coomaraswamy, A. K. 1956. Mediaeval Sinhalese Art. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Pantheon Books Inc.

- De Silva, M. 1953. “A House at Kandy, Ceylon.” Marg 6 (June): 4–11.

- de Silva, N. 1990. “The Sri Lankan Tradition for Shelter.” The Sri Lanka Architect 100 (July–August): 2–11.

- De Silva, M. 1998. The Life & Work of an Asian Woman Architect. edited by M. D. Silva, A. D. Vos, and S. Siriwardana. Kandy, Sri Lanka: George E. De Silva and Agnes Nell De Silva Trust.

- de Silva, K. M. 2014. A History of Sri Lanka. 4th Sri Lanka ed. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Vijitha Yapa Publications.

- de Vos, A. 1988. “Some Aspects of Traditional Rural Housing and Domestic Technology.” The Sri Lanka Architect 100 (September–November): 8–16.

- Frampton, K. 1983. ”Prospects for a Critical Regionalism.” Perspecta 20: 147–162. doi:10.2307/1567071.

- Frampton, K. 2007. Modern Architecture. A Critical History. 4th ed. London, UK: Thames & Hudson.

- Ghirardo, D. 1996. Architecture After Modernism. London, UK: Thames & Hudson.

- Hughes, R. 1991. The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change. Revised 1991 ed. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Lara, F. L. 2009. ”Modernism Made Vernacular: The Brazilian Case.” Journal of Architectural Education 63 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1111/j.1531-314X.2009.01027.x.

- le Roux, H. 2003. “The Networks of Tropical Architecture.” The Journal of Architecture 8 (3): 337–354. doi:10.1080/1360236032000134835.

- Lee, R., and K. James-Chakraborti. 2012. ”Marg Magazine: A Tryst with Architectural Modernity: Modern Architecture as Seen from an Independent India.” ABE Journal: Architecture Beyond Europe 1: 1–20. https://journals.openedition.org/abe/

- Lewcock, R., B. Sansoni, and L. Senanayake. 2014. The Architecture of an Island: The Living Heritage of Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Barefoot (PVT) LTD.

- Luchinger, A. 1980. Structuralism in Architecture and Urban Planning. Stuttgart, Germany: Kramer Verlag.

- Marg. 1946. ”Architecture and You.” Marg 1: 7–16, October.

- Nakagawa, T. 1991. “Ancient Architecture in Sri Lanka: Studies on Planning and Restoration of Temple Architecture in the Late Anuradhapura and Pollonnaruva Period.” Unpublished Report, Department of Architecture, Waseda University, Tokyo.

- Oliver, P. 2003. Dwellings: The Vernacular House Worldwide. Revised ed. London, UK: Phaidon Press Limited.

- Perera, A. 1996. ”Traditional Court-Yard Houses in Matale District.” In Historic Matale, edited by Editorial Board of Historic Matale, 67–96. Sri Lanka: Matale Book Publication Board.

- Pieris, A. 2007. Imagining Modernity: The Architecture of Valentine Gunasekara. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Stamford Lake (Pvt) Ltd & Social Scientists Association.

- Pieris, A. 2013. Architecture and Nationalism in Sri Lanka: The Trouser Under the Cloth. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Prematilleke, L., eds. 1994. The Cultural Triangle of Sri Lanka: International Campaign. Colombo, Sri Lanka: The Central Cultural Fund.

- Rapoport, A. 1969. House Form and Culture. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Rapoport, A. 2005. Culture, Architecture and Design. Chicago, IL: Locke Science Publishing Company, Inc.

- Robson, D. 2002. Geoffrey Bawa: The Complete Works. London, UK: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

- Robson, D. 2007. Beyond Bawa. London, UK: Thames & Hudson.

- Robson, D. 2015. “Andrew Boyd and Minnette De Silva: Two Pioneers of Modernism in Ceylon.” Matter Retrieved 13 November 2020 https://thinkmatter.in/2015/03/04/andrew-boyd-and-minnette-de-silva-two-pioneers-of-modernism-in-ceylon/

- Robson, D. 2016. The Architectural Heritage of Sri Lanka: Measured Drawings from the Anjalendran Studio. London, UK: Talisman Publishing Pte Ltd.

- Smithson, A. 1968. Team 10 Primer. edited by A. Smithson. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.