ABSTRACT

This study investigated the projects recorded in The Architectural Heritage of Modern China: Shenyang and documents of protected historical and cultural sites published by the Shenyang government from 1985 to 2020. According to fieldwork and a literature search, an original database with 153 heritage sites of industrial modernization in Shenyang was developed. For further investigation, the projects in this database were categorized by architectural function and structural type. According to historical development and changes in administration, the history of modernization in the designated era falls into four phases, and the core study area can be divided into four subareas. In this study, ArcGIS was used to make an entire distribution map, which was combined with the results of the categorization to analyze areas and obtain an overall picture of the distribution characteristics of Shenyang’s heritage of industrial modernization. The characteristics of the research objects were identified after categorization analysis of their age, function, structure, and spatial distribution in the database. Based on these results, a new evaluation of this heritage can be pursued, which can provide a basis for the future preservation and utilization of such heritage.

1. Background

In 1636, NurhachiFootnote1 established the capital of the Later Jin Dynasty (1616–1636) in the central part of Shenyang and named it Mukden City. After the capital was moved to Beijing, Mukden City became a provisional capital. Since 1840, Yingkou, which is a city near Shenyang, opened its port, and the region began to receive the influence of foreign cultures. The modernization process of Shenyang City was completed mainly by the construction and colonial activities of Tsarist Russia and Japan. Among them, it was especially affected by Japan for a relatively long time. Japan began to colonize China’s northeastern region in the early 20th century, accompanied by construction and modernization. In 1932, the Japanese government established Manchukuo (1932–1945) in the northeastern provinces of China. Shenyang was identified as an important industrial city, and the first modernized urban planning was implemented there. From the perspective of urban development, the regional scope of Munkden City took the form of a traditional Chinese city (walled city), while the modern urban area formed by foreign forces hardly overlaps with the traditional urban area. This fact gave Shenyang both traditional and modern city features, standing out from other colonial cities of the Manchukuo of a similar historical background.

According to the data analysis in the documents of protected historical and cultural sites published by the Shenyang government (Citation2020), the total number of registered historical and cultural protection sites is 238, and 127 of them were built in modern times, accounting for more than half of the total. The central city has retained and adopted the land zoning from that time on a large scale. However, due to the negative impression created by colonies, there were always various concerns and political considerations in the protection and utilization of this heritage of industrial modernization. As a result, their value is unclear, and awareness for protection is inadequate.

In recent years, China’s economy has developed rapidly, and the process of urbanization has intensified. However, in the process of urban renewal, many urban heritage sites have not received enough attention or been protected well enough. In 2015, a report entitled Cultural protection cannot catch up with demolition, nearly 400 old buildings in Shenyang have disappeared in 23 years (Pan Citation2015) was published in China Workers’ daily. It described the dilemma of heritage preservation in Shenyang and the public’s weak awareness of urban cultural heritage protection. Based on this background, it is urgent and important to deepen the research on the heritage of the industrial modernization of Shenyang. At the same time, this research was not aimed at the analysis and research of individual buildings but the analysis of the potential historical development motivation and interrelated cultural connotation of this heritage from the urban scale. The purpose was to improve the individual value judgment of this heritage and contribute to urban regional cultural inheritance and urban development opinions in the future.

2. Research objects

This study focuses on modern industrial heritage, which is an important part of cultural heritage. The industrial revolution completely changed the traditional urban pattern in the 18th century, and this industrial heritage played an extremely important role in forming current urban space and cultural identities (Wicke, Berger, and Golombek Citation2018). Industrial heritage is also a record of human memory and customs. Compared with other types of cultural heritage, it has greater scientific and aesthetic value (TICCHI Citation2011). Industrial heritage in urban spaces is an important part of urban transformation and planning practice (Oeverman and Mieg Citation2015), especially for cities like Shenyang, which have an important position in industrial history. With the development of relevant research and practice, we identified the importance of industrial heritage in the commercial world in areas such as the tourism sector. Its enormous potential has been appreciated in cultural inheritance and sustainable development (Bazazzadeh et al. Citation2020). Especially in developing countries, flexible conservation and utilization of industrial heritage is a wise solution for achieving sustainable urban development (Samadzadehyazdi et al. Citation2020).

The concept of modern industrial heritage has different definitions in various fields. In the field of world heritage, the terms industrial heritage or 20th-century architecture are generally used (UNESCO Citation1994). The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH)—which is dedicated to the study of industrial archaeology and the protection, promotion, and interpretation of the industrial heritage – also uses the term industrial heritage, and defined it as “the remains of industrial culture which are of historical, technological, social, architectural or scientific value” (TICCIH Citation2003). This definition also includes machinery and ancillary transportation equipment in addition to architecture. The Agency for Cultural Affairs in Japan uses the term modernization heritage, which is defined as buildings and structures related to the end-stage of the Shogunate (Kamei Citation1997). Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI), meanwhile, uses the term heritage of industrial modernization, which includes buildings, structures, and other objects (including machines, design drawings, and incident locations), from the end of the Edo period to the end of World War II (Nagata Citation2009). However, the formal definition corresponding to this concept has not been determined in China. This type of heritage is usually lumped together with the category of related terms such as historical buildings (Wang Citation2001) or protected historical and cultural sitesFootnote2 of industrial heritage (Wang Citation2006).

Here, the objects of research are mostly historical constructions, including a few incident areas (monuments) and urban public spaces (e.g., a square with symbolic meaning), which correspond with the definition of the heritage of industrial modernization from Japan’s METI – that is, heritage sites of industrial modernization, including buildings, structures, and other related material objects created from the late 19th century to the end of World War II.

This research aimed to clarify the state of preservation and make an original database based on the results of fieldwork and a literature search on the heritage sites of industrial modernization in Shenyang. The characteristics of historical changes of the research objects were identified after a categorization analysis of their age, function, structure in the database. In addition, the geospatial information data were input into ArcGIS for further analysis to clarify the spatial distribution characteristics of the research objects in each research area and pursue a panorama of this heritage. The above research and analysis results reveal the internal connection of these heritage sites and provide basic materials for future in-depth research. At the same time, they can also provide a basis and positive influence for regional preservation, utilization, and value judgment of such heritage sites.

3. Research method

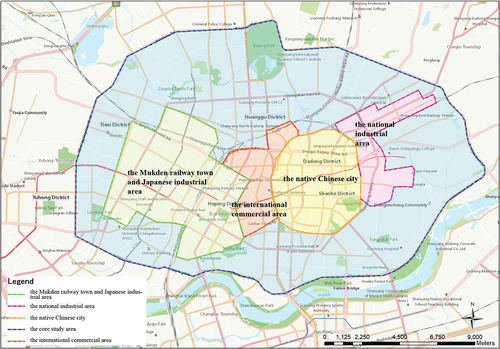

The methodology and workflow of this study is shown in . This study summarized and sorted out the materials of historical documents in the period of Manchukuo and research materials published after the World War II, such as the History of Japanese in Mukden, Manchukuo (Fukuda Citation1976), and History of Manchukuo (Manchurian Nation History Editing Publication Society Citation1976), and the local chronicles of Shenyang city, especially the important matters related to urban development in Shenyang City Annals vol.2: Urban Construction (Citation1989). According to the literature investigation, the history of modernization in the designated era falls into four phases: the beginning of foreign influence (ca. 1840–1895); development under the Russo-Japanese War (ca. 1896–1911); competition between Japanese and national capital (ca. 1912–1931); and Manchukuo and wartime policy (1932–1945). Moreover, the spatial development process of Shenyang City was clarified by studying historical maps in modern times. According to these studies, the core study area sets a scope for the main area of the first urban planning in the region formulated by Japan in 1931 (within Shenyang 2nd Ring Road). According to the historical development and changes in administration, the core area can be divided into four subareas: the Mukden railway town (the Japanese concession) and Japanese industrial area; the international commercial area (the foreign settlement); the native Chinese city (the walled city); and the national industrial area (Section 5).

In this study, a database containing 153 heritage sites of industrial modernization in Shenyang was established by investigating projects recorded in The Architectural Heritage of Modern China: Shenyang (Chen et al. Citation1995) and documents related to protected historical and cultural sites published by the Shenyang government from 1985 to 2020. The database contains information such as construction age, structure, facility function, and location, and a series of quantitative categorization analysis was carried out based on these attributes.

Categorization analysis of heritage sites is helpful for discovering the characteristics and significance of architectural and urban space, which is conducive to the formulation and implementation of conservation planning regulations and measures. This database can also have a positive effect on risk assessment for future urban renewal (Santos et al. Citation2013) and the formulation of preservation policy (González and Pozas Citation2018).By analyzing the types of facility functions, urban spatial properties can be seen, while structure analysis can help to identify the construction technology level. Through quantitative categorization analysis of heritage function and structure, combined with the historical background literature, the context of the urban planning process and the development of construction technology can be determined (Section 6.1), and the characteristics and causes of urban architectural culture can be explored (Zhang et al. Citation2004). In this study, ArcGIS was used to visualize the distribution characteristics of the heritage sites (Section 6.2). The results of the statistical analysis can clarify the urban style and peculiarities of each area by examining the structural and functional proportion of heritage elements in each area (Mollo et al. Citation2020; Xue et al. Citation2020). The causes of these statistical results were discussed, and the modern architectural features of each area were elucidated with reference to the historical materials.

4. Previous research

It is generally accepted that research on the heritage of industrial modernization began with the emergence of industrial archaeology in the 1950s and the birth of the Association for Industrial Archaeology. Afterward, western countries began to study industrial heritage sites one after another. At the Third International Conference on the Conservation of Industrial Monuments held in Sweden in May 1978, TICCIH was officially established. Since 2003, TICCIH has successively issued three international consensus documents: The Nizhny Tagil Charter for the Industrial Heritage (Citation2003), The Dublin Principles (Citation2011), and The Taipei Declaration for Asian Industrial Heritage (Citation2012), and gradually established the protection subject, the concept of industrial heritage, and the policy of development and utilization. Among them, TICCIH’s 15th international congress was held in Taipei in 2012 and issued the Taipei Declaration to promote the conservation of Asian industrial heritage. In the selected papers published at the congress, most of the papers were the latest research on the industrial heritage of Asian countries such as China, Japan, and Korea. Among them, a study on the existing water towers dependent on the Chinese Eastern Railway pointed out the problems in the protection of the industrial heritage of the colonies and hoped to draw enough attention from society by evaluating the artistic and technological characteristics of this heritage (Liu Citation2012). In addition, there was case research on selective interpretation of industrial heritage in Shenyang that pointed out that in the interpretation of this heritage, an open attitude toward history should be adopted (Fan Citation2012). Stuart SmithFootnote3 (Citation2012), who also presented an essay on the Japanese colonial empire and its industrial legacy at the congress, said that in the process of modernization in Taiwan, China, and Korea, the Japanese colonial empire, modeled on British colonial idea, played a successful role in transmitting advanced western ideas and technology until militarism prevailed in Japan. These points of view served as great inspiration for this study (pp. 208–218).

However, as the first country in Asia to research industrial heritage, Japan established the Japan Industrial Archaeology Society in 1977 and carried out an investigation and research focusing on the heritage, which was completed after the Meiji era (1868–1912). Japan also carried out an investigation and research on the industrial heritage of modernization in the fields of economics, geography, architecture, and urban planning. For example, in the management and utilization of industrial heritage, researchers such as Fukui took eight textile mill heritage sites in Osaka and Hyogo as cases to clarify the establishment process of the program for conservation and management of the heritage and its related achievements (Fukui, Abe, and Hashitera Citation2013). As for the cultural inheritance of industrial heritage, Shiroki took 10 modern buildings in Hokkaido as the research objects to discuss their value in protection from the perspective of architectural technology history and regional cultural inheritance (Shiraki, Kubo, and Ohgaki Citation2008).

China’s industrial heritage of modernization began in the 1950s. The most pioneering example of research in this area is a paper named Chinese Architecture In Recent 100 Years, which was completed by Liu (Citation1956) under the guidance of Liang SichengFootnote4, and The History of Chinese Modern Architecture (Citation1959), which was published by the China Academy of Building Research. In the following 20 years, owing to the great changes in Chinese society, relevant research works have been suspended one after another. In the 1980s, Tsinghua University and Tokyo University launched an investigation on modern architecture in important cities in the modern history of China, including Shenyang, and finally completed a series with 16 volumes of investigation reports named The Architectural Heritage of Modern China. The Shenyang chapter is also one of the basic materials used in this study. Since then, research on the heritage of industrial modernization has developed rapidly. From the research results, in addition to the above investigation and research on modern architecture, an example is Li and Gao’s comprehensive research on the history of modern urban planning in China (Li Citation2008). As for research on single cities, there has been research on urban construction in Shanghai and Tianjin completed by Zhang (Citation1990) and Luo (Citation1993). In terms of the research of industrial heritage, in addition to the subject of heritage protection, more research results on the development and utilization strategies of industrial heritage have been published in recent years. It can be seen from the above research results that the relevant research in China has gradually developed from combining architectural and urban history to the methods and strategies of heritage conservation and utilization.

Because Shenyang was once an important city of Manchukuo, the relevant research on the heritage of industrial modernization of Shenyang should be reviewed from the literature of Manchukuo. After World War II, various Japanese research groups represented by Manshikai began to sort out and study all kinds of relevant materials of Manchukuo. The representative publications are The Forty-year History of Manchukuo Development (Manshikai Citation1964) and The History of Manchukuo (Manchurian Nation History Editing Publication Society Citation1976), which provide a comprehensive description of that period. Moreover, Koshizawa (Citation2002) and Nishizawa (Citation2008) researched the history of urban planning in Manchuria and northeast China and have discussed the significance and typicality of architectural technology and urban planning designed by Japan for Northeast China, including Shenyang. In terms of Chinese literature, recognized authoritative works are The History of Manchurian Railway, written by historian Su Chongmin (Citation1990), and The Attached Land of Modern Northeast Railway (Cheng Citation2008), published by the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. These works show the establishment of the Manchurian Railway and the modernization construction process centered on the railway in the cities of Manchuria in Northeast China. Moreover, scholars from the Harbin Institute of Technology and Shenyang Jianzhu University have published research on the industrial heritage in Northeast China (Gao Citation2018; Huo and Li Citation2016; Lei Citation2012), including that based on the activities of Japanese architects and urban planners in China.

From the literature mentioned above, it can be seen that the relevant research on the heritage of industrial modernization, including Shenyang, was profound. However, China only began to show genuine academic research in the 1980s. Compared with other countries, the theoretical research and methodology are not sufficient. Research on Shenyang’s heritage of industrial modernization has been profound in architectural history, urban planning history, and the protection strategies of individual buildings, but there have been fewer studies on the preservation and distribution of the architectural heritage group from the urban scale. This study investigated the establishment of the database of the heritage of industrial modernization in Shenyang, using ArcGIS to establish visual map data to grasp the distribution characteristics of the heritage of industrial modernization from the whole city. At the same time, combined with the historical background, the potential connection of the heritage and their regional spatial characteristics was clarified. In addition, the establishment of a database will be significant to provide an information basis for future investigation and research.

5. Modernization and development in Shenyang

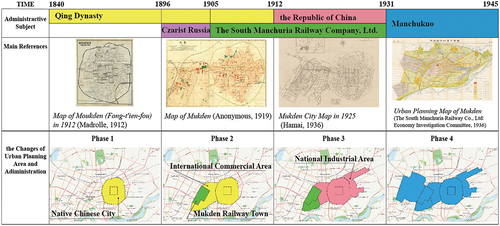

This study divides the modernization process in Shenyang into four phases, based on the extraction of important historical events as nodes according to local chronicles and historical books(). These four phases are considered separately in this section.

Figure 2. Urban development process and changes of administration (Madrolle, Citation1912; Anonymous, Citation1919; Hamai, Citation1939; The South Manchuria Railway Co., Ltd, Citation1936).

5.1. Phase 1: beginning of foreign influence (ca. 1840–1895)

Since the Opium War (1840), China was governed by the Qing dynasty and had passively accepted the influence of Western modernization. In 1858, Yingkou, the area neighboring Shenyang, was forced to open as a trading port because of the Treaty of Tientsin (Xiao Citation2010). Shenyang and the whole Northeast gradually began to accept the influence of foreign forces. The main construction activities during this phase were churches and other religious facilities built by foreign missionaries. During this period, the main area of Shenyang was roughly the same as Mukden City (built in 1657), which included a square palace area surrounded by the traditional urban layout like other capital cities in China, and the administrative body was still the Qing dynasty government.

5.2. Phase 2: development under the Russo-Japanese War (ca. 1896–911)

For joint defense, Japan, China, and Czarist Russia signed the Li – Lobanov Treaty in 1896 and established the Chinese Eastern Railway Company to start building railways (Chen and Rong Citation1993). At the same time, Russia also obtained a concession for land attached to the railway, then planned and constructed an urban area along the railway line and the attached land near Mukden station. In 1904, the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) broke out; Japan won and signed the Treaty of Portsmouth with Russia in the following year (Perez Citation2009). The interests belonging to Russia in Northeast China – including the management of the railway – transferred to Japan. In 1906, the South Manchuria Railway Company (or the Mantetsu) was established as a semi-governmental corporationFootnote5 in charge of railway construction and the management of railway attached land. From 1908, Mantetsu started planning and building the largest Mantetsu town near Mukden station (Nishizawa Citation2015, 77–80). Shenyang opened its doors as a trading port in 1903 (Jiao Citation2016). To coordinate the relationship between the old city (the walled city) and the railway subsidiary, the Qing government established an international commercial area between the two, where foreigners were permitted to settle.

5.3. Phase 3: competition between Japanese and national capital (ca. 1912–1931)

The Republic of China (1912–1949) was established in 1912, and China officially stepped into modern society and away from a feudal society. However, the various forces within China were not unified, and the management and administration of each region remained divided. Concerning Shenyang, the government centered on the Fengtian cliqueFootnote6, which served as a substitute for the Qing government and invested a large amount of capital in the area to compete with Japanese investment. This was a period of vigorous development for various industries in Shenyang. The Fengtian clique controlled the jurisdiction of the old city and international commercial area, and at the same time established new industrial areas (i.e., Dadong and Fenghai Industrial Zone) to the east of the old city to compete with the Japanese asset industry (Wang and Li Citation2017, 136–139). Due to the expansion of the Mantetsu, part of the international commercial lands fell into the scope of the Mantetsu Town. Although the Qing government had established an international commercial port area, it had not implemented effective urban planning policies, so most of the urban pattern and architectural heritage in this area were built by the Mantetsu and the Fengtian clique government.

5.4. Phase 4: Manchukuo and wartime policy (1932–1945)

After the Mukden IncidentFootnote7 in 1931, the Japanese military had essentially taken control of the entire area of Shenyang (Kato Citation2006, 118–121). In 1932, the State of Manchuria was established, and Shenyang was positioned as an important industrial city. The Fengtian Capital City Project (Japanese: 奉天都邑計画) was formulated and implemented (The South Manchuria Railway Co., Ltd: Economy Investigation Committee Citation1935), and this became the first complete and comprehensive modern urban plan in Shenyang. The new construction area during this period was the Tiexi Industrial Zone to the west side of the Mantetsu town. Because of the benefits of the policy, Zaibatsu at that time mostly built factories in this area, and it is still an important industrial zone in Shenyang today.

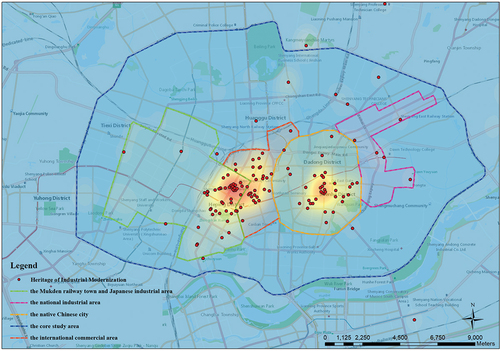

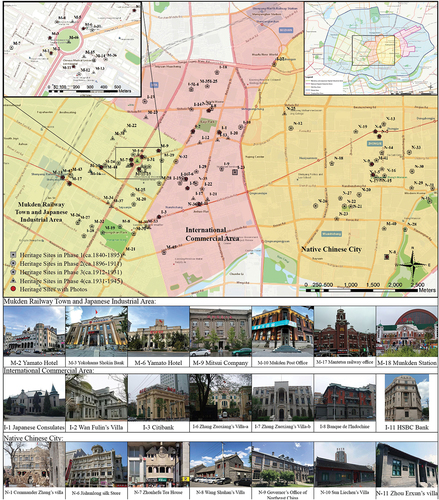

Based on these findings, the spatial scope of this study is set as the central area of the Fengtian Capital City Project, including the area within the scope of the Shenyang 2nd Ring Road (, within the blue line).According to the site’s historical development and changes in administration, the core study area has been divided into four subareas to enhance the categorization of the research: the Mukden railway town and Japanese industrial area, the international commercial area, the native Chinese city, and the national industrial area.

6. Distribution and characteristics for heritage of industrial modernization in Shenyang

The 153 projects recorded in The Architectural Heritage of Modern China: Shenyang, as well as in the protected historical and cultural site documents published by the Shenyang government, were arranged and categorized. The categorization was based on the method of classifying projects by function, structure, and completion time, divided into four phases. This process yielded the following charts.

6.1. Changes in the heritage of industrial modernization in Shenyang

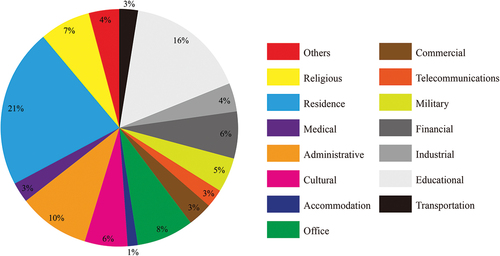

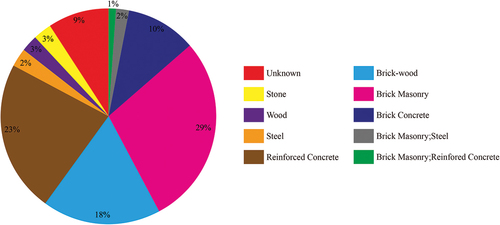

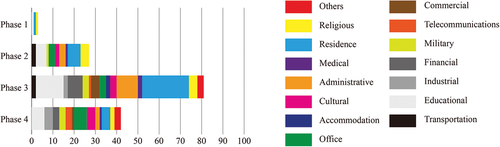

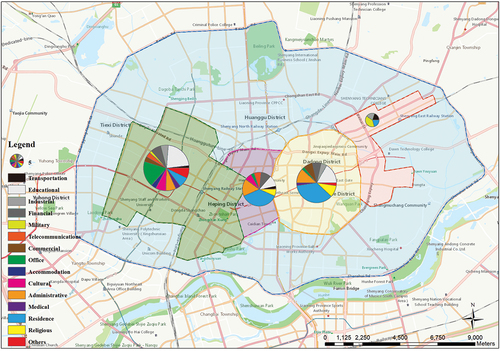

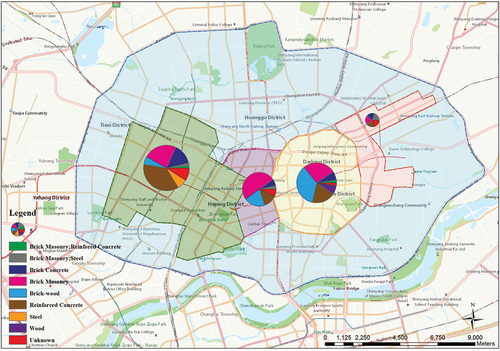

Overall, the number of existing heritage sites of industrial modernization in Shenyang increased rapidly from phase 2, peaking in phase 3 and falling back down in phase 4. Among them, the most functional types were residential (21%) and educational (16%) facilities, followed by administrative (10%) and religious (7%) facilities(). In terms of structural types, brick masonry (29%), reinforced concrete (23%), and brick-wood (18%) structures dominated().

shows the changes in the function of the heritage of industrial modernization. The heritage from phase 1 is relatively sparse lacking in diversity, mainly comprising religious buildings. With reference to the historical background from Section 5, the external influence of missionaries in this period is generally accepted. The functional categories showed a diversified development trend in phase 2. The functional types were mainly related to community construction, such as residential and educational facilities, which account for 40% of the total in this period. Administrative and office facilities were for next, accounting for 22%. In the early stage of phase 2, the heritage of industrial modernization, mainly including stations and other railway-related facilities, were developed by Tsarist Russia. Large-scale modernization construction was not initiated until Mantetsu was settled. Residence and educational facilities were the first problems to be solved to make life easier for employees in foreign countries. This has also been verified in the existing heritage types. Second, Mantetsu has built a large number of public service facilities, such as administrative infrastructure and hospitals, to meet the high standards of modern city life and prepare for further colonial activities. As in phase 3, residential and educational heritage also accounted for more (35 sites, 43% of this period). It is worth noting that the number of financial and commercial facilities increased significantly, with 70% of such heritage sites built in this phase. The construction of phase 3 was completed under the competition of the Mantetsu and Fengtian clique, and the modernization construction of Shenyang ushered in an era of prosperity. The heritage of industrial modernization of this period was also the largest (81 sites, 53% of the total). The Fengtian clique, based in northeast China and Shenyang, became their political and military center. At the same time, they vigorously developed industry by learning western advanced modernization construction ideas and technology, and gradually became the biggest competitor for the development of Mantetsu. Their series of policies and measures to encourage industry attracted talents and investment. Therefore, a large number of financial and commercial heritage sites, such as banks and stores, increased significantly during this period. The composition of the functional types in phase 4 was relatively balanced, showing the trend of diversified development in this period, but in comparison, the increase of industrial and military heritage (total seven sites) was obvious. After the establishment of Manchukuo in 1932, owing to the construction of the Tiexi Industrial Zone, Shenyang developed plenty of Japanese enterprises. In contrast, the release and implementation of The Fengtian Capital City Project gave Shenyang unified ideological guidance on urban planning. Therefore, from the perspective of the functional types of heritage, this phase showed the characteristics of diversification and balance. However, the growth of heritage sites decreased sharply, because much of the planned construction was not completed owing to the outbreak of World War II.

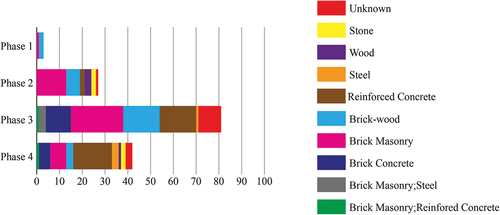

Structural changes in the heritage of industrial modernization in Shenyang are shown in . It can be seen that the brick-wood structure runs through the whole modern period of Shenyang. According to our investigation, the brick-wood structure was widely used in various facilities, such as residential buildings, educational buildings, and commercial buildings.

Brick-wood structures accounted for a large proportion in phase 1 and phase 2. However, brick masonry structures dominated and accounted for 48% in phase 2. The reason is that Mantetsu has introduced the new material of red brick into Shenyang (the local traditional buildings in Shenyang use green brick). Red brick has durability and a certain heat and sound insulation effect owing to its porosity. Therefore, it has been quickly popularized in Shenyang, with the cold climate, and has become a symbolic structure of the heritage of industrial modernization. Brick concrete and reinforced concrete structures increased in phase 3. It should be noted that 68% of the brick concrete structures and 45% of the reinforced concrete structures were constructed in Phase 3. As reinforced concrete is a new structure emerging in modern times, the cost of materials and technology required was high at that time. In the investigation, it was found that this structure was used in large public infrastructure, such as banks, hotels, offices, and factories. Reinforced concrete structures were mostly constructed by foreign capital, such as Japan, while the reinforced concrete structures produced by national capital were mostly mixed structures with brick concrete. The year-on-year increase in reinforced concrete structures was greatest in phase 4, accounting for 40% of the total in this period. Few steel structures (three sites), which were relatively rare at that time, were preserved in this period. From the composition of structural types, as can be observed that the construction level of this period was higher, a relationship to the establishment and construction of Tiexi industrial zone can be inferred.

6.2. Distribution for the heritage of industrial modernization in Shenyang

As shown in , we used the kernel analysis tool of ArcGIS to analyze the distribution of 132 heritage sites within the core study area. There are two clusters: one at the junction of Mantetsu town and the international commercial area (around Zhongshan Square), and the second at the center of the native Chinese city (around the Shenyang Palace Museum).

The heritage sites near Zhongshan Square include the Yamato Hotel (Japanese: ヤマトホテル), Bank of Korea (Japanese: 朝鮮銀行), Yokohama Shokin Bank (Japanese: 横浜正金銀行), and Fengtian Police Station (Japanese: 奉天警察署). Most are urban public facilities and have retained their architectural function and remain in use. The area surrounding the Shenyang Palace Museum is represented by Commander Zhang’s villa (Chinese: 张氏帅府), the Governor’s office of Northeast China (Chinese: 东三省总督府), and the Fengtian Commerce villa (Chinese: 奉天商会). It contains mostly residential and administrative buildings, indicating that it was the political center of the Fengtian clique at that time. It is also worth mentioning that the industrial heritage sites in the east and west industrial zones are relatively small and scattered, which may be due to the need for industrial development as many factories have been rebuilt, but these two areas still retain the attributes of an industrial zone.

Through the functional categories in each area (), we can find that the concentration of existing heritage sites of industrial modernization (from more to less) ranges from the Mukden railway town and Japanese industrial area, the native Chinese city, and the international commercial area, to the national industrial area.

The heritage of industrial modernization in the Mukden railway town and the Japanese industrial area was not only large in quantity, but also diverse and comprehensive. Educational and office facilities accounted for 22% and 18%, followed by residential buildings. Financial and cultural facilities accounted for 7%. During the period of the Mantetsu administration, the administrative areas were mainly concentrated in Mukden station (Shenyang station now) and the Grand square (Zhongshan Square now). Later, during the Manchukuo period, this area hosted the key administrative facilities area of the Kwantung Army (Japanese armed forces in Manchukuo). Public service facilities, such as the Mantetsu railway office, Mukden police office, and Mukden post office, were settled in this area, forming a modern administrative facilities cluster. Most of these facilities have been used as urban infrastructure until today. In addition, during the construction period of the Mukden Railway town, Mantetsu continuously attracted Japanese immigrants and investment with favorable conditions, and gradually formed a new business district in Kasugacho (Taiyuen Street now). Therefore, a large number of commercial and financial heritage sites of industrial modernization exist in this area. In addition to Yokohama Specie Bank (Japanese: 横浜正金銀行) and Bank of Korea (Japanese: 朝鮮銀行), there are also office buildings of Osaka Shosen Kaisha Lines (Japanese: 大阪商船ビルディング), Mitsui company (Japanese: 三井ビルディング), and other office and commercial heritage sites. As for the educational heritage sites, five facilities on the Nanman Medical College (Japanese: 南満医学堂) campus, including the affiliated hospital, auditorium, and other office buildings, have been completely preserved and are now continuously used by China Medical University. Moreover, the heritage sites of schools ranging from elementary education institutions such as the Aoi elementary School (Japanese: 葵尋常小学校) to higher education institutions such as the Manchuria Educational Specialized School (Japanese: 満州教育専門学校) are preserved.

As for the functional composition of the international commercial area, residential facilities accounted for 37% at most, followed by administration and finance, accounting for 17% and 10%, respectively. The international commercial area is an area that is automatically opened for foreigners to live and trade. In 1911, Shiyiwei Road, the most important street in the international commercial area, was built (Wang and Li Citation2017, 76). It connected the Daxi Road in the native Chinese city area to the east and the Chiyoda Dori (now Zhonghua Road) in the center of the Mukden railway town to the west. Amid modernization, this area has gradually become a buffer area for the two political forces of Fengtian clique and Mantetsu. A prosperous financial street has been formed along the Shiyiwei Road. Now, the sites of Citibank, HSBC Bank, and Banque de l’Indochine remain. In terms of administrative heritage, it is worth discussing the heritage of the consulate. Owing to the land usage of the international commercial area, in modern times, seven countries, including Britain, the United States, France, and Germany, settled and established consulates, and the existing consulates in this area are German and Japanese. In addition, there are supporting administrative facilities, such as the Mukden Customs House. As residential heritage sites, with the development of international commercial areas, Chinese and foreign political and business celebrities have gradually gathered here to buy houses and lands, whereas occidental classical residential houses prevailed among Chinese upper-class figures at that period. The more representative ones are Wan Fulin’s villa (Chinese: 万福麟公馆) and Zhang Zuoxiang’s villa (Chinese: 张作相公馆).Footnote8

The functional composition of the heritage of industrial modernization in the native Chinese city area is similar to that in the international commercial area. The proportion of residential properties has risen to 37%, followed by educational and administrative facilities, accounting for 17% and 12% respectively. This area is a traditional Chinese capital city that was formed in the 15th century. Therefore, the development in modern times is relatively slow and conservative, mostly comprising some small-scale residential buildings and 2–3 story administrative heritage sites of industrial modernization. There was no occidental architectural complex until the Fengtian clique settled in. Commander Zhang built his official mansion (five buildings remain) in the southeast of this area, and gradually formed the political power center of the Fengtian clique warlords around there. In addition, compared with others, there are more commercial heritage sites in this area (accounting for 7%), as modernization has prompted some traditional businesses to expand their industries and build new shops, such as the Zhonghefu Tea House (Chinese: 中和福茶庄) and the Jishunlong Silk Store (Chinese: 吉顺隆丝坊) on Zhongjie Street. Zhongjie Street remains a well-known commercial street in Shenyang.

The number of heritage sites in the national industrial area is relatively small, but there are a few military facilities. According to the literature research, military sites were scattered in the Tiexi District and the periphery of the main research area. Most were built during phase 4, the period of military control after the establishment of Manchukuo.

reveals the results of the analysis of the structural categories in various regions.

From high to low, the main types of structures in the Mukden railway town and Japanese industrial area are reinforced concrete structures (36%), brick masonry structures (24%), brick concrete structures (15%), and steel structures (7%). Red brick is the most widely used, represented by Mukden station and Mantetsu railway office buildings. The color of red brick material is fully utilized and plays the role of decoration and beautification. The appearance of red brick buildings creates a completely different modern urban atmosphere in Shenyang from the green bricks used in construction materials before modern times. In fieldwork, we found that when locals describe Japanese architecture, they usually use the phrase “red brick building”. This also reflects the impact of this architectural form on local architecture. A reinforced concrete structure is undoubtedly a more advanced form of architectural structure in modern times. As mentioned above, concrete and construction technologies were mainly introduced by Mantetsu. Many large-scale heritage sites of industrial modernization in Mukden railway town and the Japanese industrial area were made of reinforced concrete structures. As early as 1906, a multi-story Japanese-built public building known as the Shichifukuya department store (Japanese: 七福屋百貨店) (Fukuda Citation1976, 61) adopted the reinforced concrete structure. It was the largest department store in Shenyang at that time, and it was also the first large-scale building in Shenyang. Subsequently, reinforced concrete structures were widely used in representative buildings in Mukden railway town, such as the Yamato Hotel and Oriental Development bank (Japanese: 東洋拓殖銀行). Mantetsu has not only promoted the development of reinforced concrete structures in Shenyang, but also promoted the development of large-scale infrastructure.

Half of the heritage sites of industrial modernization in the international commercial area are brick masonry structures, followed by brick-wood and reinforced concrete structures, at 20% and 13%, respectively. It can be seen from the above that the heritage of industrial modernization of the region represents a mixture of different types owing to the input of multinational cultures. Brick is widely used as the main building material in this area. From , it can be seen that functional types with a larger proportion in this area are residential and administrative heritage sites. Unlike Mukden railway town, the facilities in this area are small, and brick materials are economical and fully embrace the stylish occidental architecture form, which is why it is widely used in this area. Brick is also widely used in both national and foreign properties. Brick-wood structures are mostly national capital facilities, such as Daguan Tea House (Chinese: 大观茶园) and Beishi Theatre (Chinese: 北市剧场).

In the native Chinese city area, brick-wood structures account for 36%, followed by brick masonry structures and reinforced concrete structures, accounting for 26% and 19%, respectively. This is also an area where brick materials are widely used. However, compared with international commercial areas, bricks in this area are mainly used in commercial buildings with small volumes. When used in residential buildings, they are often combined with wood structures to create brick-wood structures (e.g., the former site of Wang Shuhan’s villa, Chinese: 王树翰寓所). Moreover, it is worth mentioning that most of the bricks in this area are traditional green bricks. Researching historical materials, it appears that the native Chinese city did not implement large-scale modern urban planning, and its urban texture retained the characteristics of a traditional city. Some wooden buildings have been preserved in this area including Sun Liechen’s villa (Chinese: 孙烈臣公馆) and Zhou Erxun’s villa (Chinese: 赵尔巽公馆), which represent the Chinese traditional style of architecture.

7. Conclusion

7.1. Distribution characteristics over time

From the perspective of historical development, the birth and development of Shenyang’s Heritage of industrial modernization were undoubtedly completed under the influence of foreign influences. Combined with the analysis of historical background and literature survey, it can be said that the heritage sites present the characteristics of the development of modernization in Shenyang from the changes of the function and structure of the industrial heritage of modernization in Shenyang. Throughout the modern urban development of Shenyang, it has been seen that from the birth to every step of promotion of the heritage of industrial modernization in Shenyang, foreign influence has been significant. According to the analysis of functional and structural changes to the heritage of industrial modernization, these changes present the characteristics of modern development in Shenyang.

In phase 1 (the beginning of foreign influence), there were few heritage sites of industrial modernization, but mainly occidental regional facilities using local materials and traditional brick-wood structures that are distributed in the surrounding counties and villages. It can be seen that the modernization construction activities in this phase did not have a large-scale impact on the architectural form in Shenyang.

In phase 2 (development under the Russo-Japanese War), the colonial activities of the Mantetsu produced a localized but complete modern urban plan. Mantetsu stimulated and promoted modernization development in Shenyang during this phase.

In phase 3 (competition between Japanese and national capital), the modernization of construction reached its peak, and the number of heritage sites in this period was also the largest, accounting for 52% of the total. In this phase, the development of reinforced concrete structures also explained the significant increase in heritage sites.

In phase 4 (Manchukuo and wartime policy), since the Fengtian Capital City Project was completed and implemented, Shenyang had a more substantial and unified modern planning theory. Meanwhile, the growth of various heritage sites in this period was relatively average. Even so, due to the onset of World War II, many of the planned projects were not carried out. This is also part of the reason for a decrease in the growth of heritage sites in phase 4 ().

Table 1. Characteristics of each phase.

7.2. Characteristics of spatial distribution

Throughout the modern urban development of Shenyang, due to the changes and confrontations of administrative subjects, the uneven development of various regions in the city presents a fragmentation of the urban texture. The distribution of heritage sites of industrial modernization in Shenyang City appears sparse around the periphery and concentrated at two clusters at the junction of Mantetsu town and the international commercial area, and the center of the native Chinese city, which corresponded to the two competing power centers at that time (i.e., the South Manchuria Railway Company and the Fengtian clique). The heritage of industrial modernization of each research area was formed under a specific social background and conditions, and its development context determines the different cultural foundations. There is a deep-rooted accumulation of Shenyang’s traditional culture in the native Chinese city area, while the Mukden railway town and Japanese industrial area are dominated by Japanese modern culture. In the international commercial area controlled by Fengtian clique warlords, however, as a place for international trade development, multiple forces from diverse cultures can be seen.

Compared with other areas, the Mukden railway town and Japanese industrial area have the largest number of heritage sites of industrial modernization, with a high degree of diversity. From the richness of the heritage of industrial modernization functional types, this area has complete urban functions, which make it less interdependent with other areas, and intensifies the separation between areas.

The international commercial area has relatively more commercial heritage sites, as well as more brick masonry structures. In terms of functional types, the proportion of administrative and financial heritage sites, including consulates and foreign banks, is relatively high. Reinforced concrete buildings in this area were mostly built by foreign assets; in contrast, national assets prefer to use traditional brick-wood structures with a relatively low cost and low technical content. From the application of structural types, it can be seen that the differentiation of the international commercial area is obvious.

The heritage of the native Chinese city includes most residential facilities, and there tend to be more brick-wood and wood-structured buildings, reflecting the characteristics of traditional Chinese architecture. The proportion of brick concrete structure and reinforced concrete structure is small because of the requirement for new building materials, such as concrete, which cannot achieve self-sufficiency. Compared with other areas, the native Chinese city is the area least affected by modernization.

The national industrial area has fewer preserved heritage sites. However, land use as an industrial estate has not changed. Although many facilities have been demolished and rebuilt, some of the factory sites remain. Urban texture has also been partially preserved ().

Table 2. Characteristics of each phase.

Through the analysis of the database of Shenyang’s heritage of industrial modernization, the context of modernization in Shenyang was described in this study. Through analysis of the characteristics of spatial distribution, the regional development characteristics and preservation status of the heritage of industrial modernization in Shenyang was grasped. From these results, we can not only see the panorama of Shenyang’s heritage of industrial modernization, but we can also show their historical and potential cultural connection.

Compared to other cultural heritage, the heritage of industrial modernization in Shenyang has long been neglected. In recent years, with the intensive study and introduction of protection policies, many heritage sites have been registered as historical and cultural sites, which offered instant protection and encouraged the immediate completion of rescue protection activities. For cities like Shenyang, however, where the modern industrial heritage is densely distributed, it is far from enough to protect individual buildings. Through the analysis of categorization and spatial distribution, the panorama of Shenyang’s heritage of industrial modernization can be seen, and the historical and cultural connection of these heritage sites can be considered when exploring future protection, utilization, and renovation methods for the heritage of industrial modernization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Nurhachi (1558–1626) was a Jurchen chieftain considered to be the founding father of the Manchu state in China, later known as the Qing dynasty (1644–1912).

2 Protected Historical and Cultural Sites (Chinese: 文物保护单位) is the general term for immovable cultural relics identified as objects for protection in mainland China.

3 Stuart B Smith is the general secretary of the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage, UK.

4 Liang Sicheng (Chinese: 梁思成; 1901–1972) authored the first modern history of Chinese architecture and was the founder of the Architecture Department of Northeastern University in 1928, and of the same department at Tsinghua University in 1946.

5 This mainly refers to the institutions – half government, half private companies – set up by the Japanese government to control materials and capital during the Sino-Japanese War (1895) up to World War II.

6 The Fengtian clique (Chinese: 奉系军阀) was one of several opposing military factions that constituted the early Republic of China during its Warlord Era.

7 This was an event staged by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

8 The information on heritage sites in refers to Appendix A..

References

- Bazazzadeh, H., A. Nadolny, K. Attarian, B. Safar Ali Najar, and S. S. Hashemi Safaei. 2020. “Promoting Sustainable Development of Cultural Assets by Improving Users’ Perception Through Space Configuration; Case Study: The Industrial Heritage Site.” Sustainability 12 (12): 5109. doi:10.3390/su12125109.

- Cheng, W. R. 2008. Jin Dai Dong Bei Tie Lu Fu Shu Di [Modern Northeast Railway Annex]. Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press.

- Chen, Z. H., and Z. L. Rong, Eds. 1993. Zhong Guo Jun Shi Shi Ci Dian [Dictionary of Chinese Military History]. Wuhan, China: Hubei People’s Press.

- Chen, B. C., F. H. Zhang, S. Murumatsu, and Y. Nishizawa. 1995. Zhong Guo Jian Zhu Zong Lan: Shen Yang Pian [The Architectural Heritage of Modern China: Shenyang]. Beijing: China Architecture Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.

- Editorial Committee of Chinese Modern Architectural History. 1959. The History of Chinese Modern Architecture. Peking: China Academy of Building Research.

- Fan, X. (2012). Selective Interpretation of Chinese Industrial Heritage Case Study of Shenyang Tiexi District. In Selected Papers of the XVth International Congress of the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage Taipei, 161–168.

- Fukuda, M. 1976. Man Shu Ho Ten Ni Hon Jin Shi [History of Japanese in Mukden]. Tokyo: Kenkosha.

- Fukui, M., H. Abe, and T. Hashitera. 2013. “A Primary Contractor’s Role in Conservation of Industrial Heritage.” The Architectural Institute of Japan’s Journal of Architecture and Planning 78 (687): 1067–1076. doi:10.3130/aija.78.1067.

- Gao, F. 2018. ”Research on Value Evaluation of The Chinese Eastern Railway Industrial Heritages from Perspective of Heritage Corridor.” Doctoral diss., Harbin Institute of Technology.

- González, F. J., and B. M. Pozas. 2018. “Housing Building Typology Definition in a Historical Area Based on a Case Study: The Valley, Spain.” Cities 72 (A): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.07.020.

- Hamai, M. 1936. Dai Hoten Zen Hakari [Mukden City Map in 1925] (Map Data). Mukden, China: Osakaya Go Shoten.

- Huo, W., and C. Li (2016). Shenyang Shi yi ban xing li shi jian zhu de bao hu yu li yong yan jiu [Study on Protection and Utilization of General Historical Buildings in Shenyang]. In The 19th Annual Conference of National Architecture Institute of China Proceedings Peking, 51–66.

- Jiao, N. 2016. “Kai Bu Tong Shang Dui Jin Dai Fengtian Gong Shang Ye Fa Zhan De Ying Xiang Qian Xi (1906-1931) [Brief Analysis of the Influence of Opening Trading Port on the Development of Industry and Commerce in Modern Mukden].” Literature Life (Trimonthly Publication) 1: 155–156.

- Kamei, N. 1997. “Kindaika Isan [Heritage of Industrial Modernization].” Nogyo Doboku Gakkaishi [Journal of the Agricultural Engineering Society, Japan] 65 (11): 1123.

- Kato, K. 2006. Mantetsu Zenshi: Kokusaku Gaisha no Zembo [The South Manchuria Railway Co., Ltd. Complete History: The Total Picture of the Semi-Governmental Corporation]. Tokyo: Kodansha Gakujutsu Bunko.

- Koshizawa, A. 2002. Manshukoku no Shuto Keikaku [The Capital Planning of Manchurian]. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo Ltd.

- Lei, J. Y. 2012. ”Architectural Heritages Study of The Southern Branch of Chinese Eastern Railway.” Doctoral diss., Harbin Institute of Technology.

- Li, B. 2008. Zhong Guo Jin Dai Cheng Shi Gui Hua Yu Wen Hua [Urban Planning and Culture in Modern China]. Peking: Hubei Education Press.

- Liu, J. 1956. ”Chinese Architecture in Recent 100 Years.” Doctoral diss., Tsinghua University.

- Liu, T. (2012). An Analysis on the Existing Water Towers in Dependency of Chinese Eastern Railway. In Selected Papers of the XVth International Congress of the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage Taipei, 103–112.

- Local Chronicle Compilation Office of Shenyang Municipal People’s Government. 1989. Shen Yang Shi Zhi [Shenyang City Annals Vol.2]. Shenyang, China: Shenyang Publishing House.

- Luo, S. 1993. Jin Dai Tian Jin Cheng Shi Shi [Modern Urban History of Tianjin]. Peking: China Social Sciences Press.

- Madrolle, C. Plan of Native Chinese City of Mukden. 1912. Madrolle's Guide Books: Northern China (Korea: Hachette & Company).

- Manchurian Nation History Editing Publication Society. 1976. Man Shu Koku Shi [History of Manchukuo]. Tokyo: Kenkosha.

- Manshikai. 1964. Man Shu Kai Hatsu Yon Ju Nen Shi [Manchuria Development History of 40 Years]. Tokyo: Kenkosha.

- Map of Mukden. 1919. ”Shenyang Archives.”

- Mollo, L., R. Agliata, L. M. Palmero Iglesias, and M. Vigliotti. 2020. “Typological GIS for Knowledge and Conservation of Built Heritage: A Case Study in Southern Italy.” Informes de la Construcción (Online) 72 (559): 1–7.

- Nagata, K. 2009. “Sangyo Isan Kanren Joho: Keizaisangyosho no Kindaika Sangyo Isan Gun 33 ni tsui te [Industrial Heritage Related Information: About 33 Heritage Constellations of Industrial Modernization].” Sangyo Isan Kenkyu [Research of Industrial Heritage] 16: 97–102.

- Nishizawa, Y. 2008. Nihon Shokuminchi Kenchiku Ron [Theories of Japanese Colonial Architecture]. Nagoya, Japan: The University of Nagoya Press.

- Nishizawa, Y. 2015. Zusetsu Mantetsu : Manshu No Kyojin [Illustrated Manchuria: Giant of Manchuria]. Tokyo: Kawade Shobo Shinsha.

- Oeverman, H., and H. Mieg. 2015. Industrial Heritage Sites in Transformation Clash of Discourses Routledge Studies in Heritage. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Pan, Y. 2015, December 14. ”Cultural protection cannot catch up with demolition, nearly 400 old buildings in Shenyang have disappeared in 23 years.” China News. http://www.chinanews.com/sh/2015/12-14/7669413.shtml

- Perez, L. G. 2009. “The Treaty of Portsmouth and Its Legacies.” The Journal of Japanese Studies 35 (2): 424–426. doi:10.1353/jjs.0.0102.

- Protected Historical and Cultural Sites Department of Shenyang. 2020, December. ”List of protected historical and cultural sites in Shenyang.” www.shenyang.gov.cn/

- Samadzadehyazdi, S., M. Ansari, M. Mahdavinejad, and M. Bemaninan. 2020. “Significance of Authenticity: Learning from Best Practice of Adaptive Reuse in the Industrial Heritage of Iran.” International Journal of Architectural Heritage 14 (3): 329–344. doi:10.1080/15583058.2018.1542466.

- Santos, C., T. M. Ferreira, R. Vicente, and R. M. da Silva. 2013. “Building Typologies Identification to Support Risk Mitigation at the Urban Scale – Case Study of the Old City Centre of Seixal, Portugal.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 14 (6): 449–463. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2012.11.001.

- Shiraki, R., K. Kubo, and N. Ohgaki. 2008. “A Study on the Spreading of Community Development Starting from the Renovation of Historical Buildings.” The Architectural Institute of Japan’s Journal of Architecture and Planning 73 (625): 601–609. doi:10.3130/aija.73.601.

- Smith, S. 2012. ”The Japanese Colonial Empire and Its Industrial Legacy.” In Selected Papers of the XVth International Congress of the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage Taipei, 208–218.

- Su, C. M. 1990. Man Tie Shi [History of the Mantetsu]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.

- The South Manchuria Railway Co., Ltd: Economy Investigation Committee. 1935. Hoten Toshi Keikaku Heimenzu [Mukden Urban Planning Map]. Dalian, China: South Manchuria Railway: Economy Investigation Committee.

- TICCHI. 2011. ”The Dublin Principles.” In Conservation of Industrial Heritage Sites, Structures, Areas and Landscapes. https://ticcih.org/about/about-ticcih/dublin-principles/

- TICCIH. 2003. “The Nizhny Tagil Charter for the Industrial Heritage.” TICCIH XII International Congress 169–175.

- TICCIH. (2012). Taipei Declaration for Asian Industrial Heritage. https://ticcih.org/about/charter/taipei-declaration-for-asian-industrial-heritage/.

- UNESCO. 1994. ”Report of the Expert Meeting on the ‘Global Strategy’ and Thematic Studies for a Representative World Heritage List.” https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/1570

- Wang, J. H. (2001). ”Lun Li Shi Wen Hua Yi Chan Bao Hu De Ceng Ci [A Study on the Levels of Historical and Cultural Heritage Protection].” In Zhong Guo Cheng Shi Gui Hua Xue Hui 2001 Nian Hui Lun Wen Ji [Proceedings of the Annual Conference of China Urban Planning Association in 2001] Peking.

- Wang, Y. L. 2006. “Wen Wu Bao Hu Dan Wei Gai Nian Ji Qi Ying Yong Chu Tan [Preliminary Study on the Concept and Application of Historical and Cultural Sites of Protected].” Zhong Guo Wen Wu Ke Xeu Yan Jiu [China Cultural Heritage Scientific Research] 4: 34–35. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-9677.2006.04.009.

- Wang, J., and B. H. Li. 2017. Shenyang Jin Dai Cheng Shi Gui Hua Li Shi Yan Jiu [Study on the History of Shenyang Modern City Planning]. Jinan, China: Shandong People’s Publishing House.

- Wicke, C., S. Berger, and J. Golombek, eds. 2018. Industrial Heritage and Regional Identities. London: Routledge.

- Xiao, Y. Q. 2010. “The Conclusion and Enforcement of the Clause Concerning Russians’ Missionary Privileges in China in the Tianjin Treaty.” Journal of Fujian Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 5: 132–138.

- Xue, G., Y. Tang, C. Li, C. Liu, and Y. Fu. 2020. “Cheng Du Li Shi Jian Zhu Lei Xing Hua Fen Yu Kong Jian Fen Bu Yan Jiu [Research on the Categorization and Spatial Distribution of Building Heritage in Chengdu].” Journal of Leshan Normal University 35 (7): 26–31.

- Zhang, Z. 1990. Jin Dai Shang Hai Cheng Shi Yan Jiu [Urban Study of Modern Shanghai]. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House.

- Zhang, Q. L., J. P. Wu, Y. Zhen, and J. Shu. 2004. “A GIS-Based Gradient Analysis of Urban Landscape Pattern of Shanghai Metropolitan Area, China.” Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology 28 (1): 78. doi:10.17521/cjpe.2004.0012.

Appendix Appendix A.

Information of heritage sites in