ABSTRACT

The changing state-market interests and civic-health relations in advancing and consuming the healthcare industry have reshaped urban development strategies in China. Hospitals, universities, and tech offices are integrated into the “medical city” as a new scheme for producing urban spaces. In comparison to “eds and meds” in the United States, this study proposes the medical-university-industry linkage framework to offer insights into the medical city in China. It argues that despite the new features, the medical city is a product of profit-driven real estate speculation camouflaged by healthcare businesses. The paper uses the Peking University Healthcare City as a case study to examine the strategies that the public and private actors deployed to justify land and legitimize place-making in the medical-university-industry linkage. Based on that, the research also proposes an optimized medical-university-industry linkage that capitalizes on knowledge production and consumption in the healthcare industry, which could serve as the guide for future medical cities.

1. Introduction

The healthcare business has long transcended its pure function of providing care. The knowledge-intensive activities associated with the provision and consumption of healthcare services and advanced medical education and research have been deemed important drivers for urban development. Particularly in the United States, universities, medical schools, and hospitals act as anchor institutions in their threefold work of cutting-edge biomedical and clinical research, medical education, and innovative health business practices (Berg and Klink Citation1996; Winant Citation2021). They participate in local and national markets, employ workers, and purchase from other businesses (Porter Citation2016). This method is characterized as “eds and meds” and is widely found in American cities including Washington, Philadelphia, San Diego, and Baltimore (Harkavy and Zuckerman Citation1999). “Eds and meds” have transformed the urban landscape in the United States, producing dense urban areas driven by the healthcare industry. Famous places include the University of Pittsburgh Medical Centre in Pittsburgh, the Longwood Medical Area in Boston, and the Texas Medical Centre in Houston (Simpson Citation2019).

With the rapid social transformations underway in China, the healthcare industry has similarly taken an increasingly important role in China’s urbanization process. However, the healthcare business is a localized strategy for producing the “medical city” in China’s real estate speculation. On the one hand, the state has promoted the healthcare industry to address demographic transformation, industrial reorganization, and healthcare reform. The policy initiatives have encouraged the private sector to gradually shift to healthcare businesses. On the other hand, the urban development process in China is essentially land-dependent and speculation-driven (He and Lin Citation2015; Lin and Zhang Citation2015). Large urban projects are “place-making” strategies to facilitate land development and the consumption of space (He and Wu Citation2009; Wang Citation2014). It is inevitable to see the eventual convergence between the healthcare industry and real estate speculation in the new urban typology of the medical city. Bearing the convergence forces, the medical-university-industry linkage emerged as a critical framework to enable real estate speculation in the healthcare industry.

This study thereby investigates how China’s healthcare industry is integrated with real estate speculation in the medical city, and the study proposes the medical-university-industry linkage as a framework to understand the specific strategies deployed in the production of space. Conceptually this study attempts to explore how developers navigate through the state and market interests in the healthcare industry and argues that the healthcare business is a “chameleon-like” strategy to justify land appropriation and legitimize profit-seeking place-making (Chien Citation2013a; Li, Li, and Wang Citation2014; Wu Citation2015). Methodologically this study collects evidence from the case study of Peking University Healthcare City, which is an assemblage of hospitals, commercial office development, and biopharma tech offices. The investigation focuses on the programmatic and spatial strategies that establish the medical-university-industry linkage which camouflages real estate speculation with healthcare businesses. Following that, the paper also proposes an optimized medical-university-industry linkage that guides future medical city development based on the knowledge economy as a result of the healthcare industry.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1. Real estate speculation in China’s transforming urbanism

Scholarship has attempted to conceptualize real estate speculation in China’s transforming urbanism. Since the market-oriented reforms in the late 1970s, the Chinese state has seen a transformation towards neoliberal governance. Particularly after the tax-sharing reform in 1994 which reshuffled central-local fiscal relationships, the central government recentralized its control over fiscal allocation, which limited tax revenue at the local level significantly (Jin, Qian, and Weingast Citation2005). The fiscal responsibility of local governments was strengthened with greater decision-making autonomy and growth-oriented targets to drive local economic growth (Walder Citation1995). This fiscal decentralization, together with other complementary reforms, provided an institutional foundation for a “Chinese-style federalism” (Montinola, Qian, and Weingast Citation1995), or “local state corporatism” (Oi Citation1992). Interlocal competitions have driven local states to ally with the private sector to promote speculative urban development (He and Wu Citation2005, Citation2009; Lauermann Citation2018). City building has thereby become a competitive enterprise for local governments who seek to outdo each other in “place-making”, both to attract investments and to conjure up trophy projects (Wang, Potter, and Li Citation2014). Therefore, speed is prioritized by local states since urban growth is a city-based accumulation strategy (Chien and Woodworth Citation2018).

As a result, speculative urban development has been a major force in the spatial production of post-socialist Chinese cities (Wu Citation2015). Driven by the aspiration for economic growth, the entrepreneurial local states financially rely on the private sector and form coalitions (Wu Citation1999, Citation2002; Zhu Citation2004). The local states hence actively mobilize and deregulate the market (He and Wu Citation2009), and invite the private sector to interact in the processes of producing and consuming urban spaces (He and Lin Citation2015). Furthermore, the expanding housing market and the increased financialization of the built environment have made the real estate industry a shortcut to growth (Theurillat and Bideau Citation2022; Theurillat, Lenzer, and Zhan Citation2016; Zhang Citation2005). Local governments have since the late 1990s devoted themselves to developing residential properties by extracting revenue from land (He and Wu Citation2005; Lin and Zhang Citation2015). The urbanization process in China has thereby been driven by large-scale real estate speculative projects (Lichtenberg and Ding Citation2009; Wu Citation2015), which are based on consumption activities such as housing, shopping, tourism, and megaevents (Hsing Citation2010; Wu Citation2015; Zhao et al. Citation2017).

At the same time, the state-market coalition in China should be distinguished from a “retreat of the state” in the West. Scholars have characterized China’s interventionist state as proactively using market instruments to maximize the state’s interests (Wu Citation2018, Citation2020). The state has de facto the right to deregulate the market and perform administrative restructuring, both enable the private sector during the process of producing new urban spaces driven by profit accumulation (Chien Citation2013b; He et al. Citation2018). For example, Zhang (Citation2002) and He and Wu (Citation2005) identified the local government’s pro-growth policies in the coalition with real estate developers in the process of urbanizing Shanghai. Su and Qian (Citation2020) use Ordos City’s master plan to articulate the role of state deregulation in facilitating speculative real estate overbuilding. Under the eco-state restructuring network, Chang, Leitner, and Sheppard (Citation2016) argued that China’s eco-city is a product of the state’s shifting interests in the environmental sector and the devolution of governance to the non-state actors.

Under such a state-led coalition, the private sector has invented strategic instruments to justify land appropriation for real estate speculation, which is the fundamental capital for the state and market to orchestrate “land-driven urbanization” (Lin and Zhang Citation2015; Yeh and Wu Citation1996; Zhu Citation2005). The local states and developers have invented various types of “chameleon-like” projects to justify land appropriation and place-making thus legitimizing profit-accumulation (Lin and Zhang Citation2015; Wu Citation2015). For example, “eco-cities” are the results of land-speculation-driven local entrepreneurialism (Chang, Leitner, and Sheppard Citation2016; Chien Citation2013a). “University towns” are the land-centered, profit-driven strategies orchestrated by the university, the local state, and financial institutions against centralized land use controls (Li, Li, and Wang Citation2014; Ruoppila and Zhao Citation2017; Shen Citation2022). “New towns” that are usually located at the urban fringe are the land-centered investment and financing platforms that camouflage the expansive urban expansions to sustain agglomeration and alleviate the hyper-concentration of central cities (Governa and Sampieri Citation2020; Theurillat and Bideau Citation2022; Zou Citation2021).

Against this theoretical backdrop, the conceptualization of large urban projects in China is often rooted in the fundamental principles of real estate speculation. The local states and developers often seek and partner with industries that are favored by state deregulation to legitimize profit accumulation based on land development. The healthcare industry has recently received civic attention and state preferential policies. However, the understanding of the healthcare industry in China’s urbanization processes demands a different perspective from other countries because the healthcare industry in China is state-orchestrated. This study, therefore, introduces the medical-university-industry linkage framework to investigate the roles of the healthcare industry in China’s transforming urbanism.

2.2. The medical-university-industry linkage and the medical city

“Eds and meds” in the United States is an international precedent that represents how the healthcare industry has driven urban and economic development. “Eds and meds” as an urban development strategy is present in many American cities including Washington, Philadelphia, San Diego, and Baltimore (Harkavy and Zuckerman Citation1999). Universities, together with their medical schools and affiliated teaching hospitals, act as anchor institutions and participate in local and national markets, employ workers, and purchase from other businesses (Porter Citation2016). In such an arrangement, universities and hospitals become the land developer in their threefold work of patient care, medical education, and biomedical research (Bartik and Erickcek Citation2008; Berg and Klink Citation1996). Accompanied by the privatization and commercialization of health care (Erickson, Gavin, and Cordes Citation1986), the healthcare industry in the United States has transformed the urban landscape and economic structure in American cities (Winant Citation2021), and produced dense urban areas characterized as “medical cities” (Simpson Citation2019). Famous examples include the Texas Medical Center in Houston, the Longwood Medical Area in Boston, and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pittsburgh. In these medical cities where hospitals and medical professionals are concentrated, cutting-edge biomedical and clinical research is conducted, advanced medical education is delivered, and innovative health business practice is offered.

However, the healthcare industry in China’s urbanism is localized by institutional specificities. On the one hand, healthcare in China is a rising industry driven by the state’s interests in addressing rapid demographic, industrial, and social transformations. The increasingly aging population in China demands advanced healthcare services and long-term care (Feng et al. Citation2011). In response, the State Council of China (Citation2013a, Citation2019b) has prioritized the establishment of the healthcare and long-term care industry (yi yang jie he). Since 2013 the state has encouraged the private sector to build residential care facilities by providing preferential policy treatments including tax breaks and land allotment or leasing (Feng et al. Citation2020). The “Healthy China 2030” Planning Outline also promotes the integration of healthcare, tourism, and real estate development (State Council of China Citation2019a). Furthermore, driven by the aspiration for hi-tech self-reliance, China has prioritized biotechnology to advance its international competency (State Council of China Citation2013b). Under the new five-year period “145” (2021–2025), biotechnology is strongly supported by the government through tax breaks and government purchase deregulation (Schmid and Xiong Citation2021). These policy incentives have encouraged the private sector to gradually shifted to healthcare businesses.

On the other hand, the rise of the healthcare industry is rooted in the state’s interests in healthcare reforms. In the state-dominant era, China had a public medical system fully funded by the government (Luk Citation2017, 29). However, driven by the neoliberal reforms since the 1980s, healthcare was seen as a consumption activity rather than a fundamental right. The Chinese state radically cut back its role in funding health services (Duckett Citation2011), and hospitals operated income-earning services based on selling medicines for kickbacks and ordering fee-for-service charges (Yip and Hsiao Citation2015; Yip et al. Citation2010). As a result, since the mid-1990s, Chinese people increasingly experienced difficulty in accessing affordable healthcare (Yip and Hsiao Citation2015). In response, the 2009 reform prioritized addressing the social issues in healthcare. Between 2008 and 2012, the new multi-layered public health insurance system covered above 95% of China’s population (Dou, Wang, and Ying Citation2018). However, the system relied heavily on baseline insurance under government programs and co-insurance by individuals out of their savings. Inflating health expenditure emerged because there is little private insurance coverage and providers operate with low margins (Yip et al. Citation2019). China thereby launched its new cycle of reform in 2013, which encourages private health insurance to supplement the basic social health insurance and to set up private healthcare facilities (Xinhua News Agency Citation2014). The privatization of healthcare also aims to use competition to stimulate changes in the hospital system which is characterized as for-profit and delivering wasteful, inefficient, and low-quality medical services (Yip and Hsiao Citation2015).

As a result, the demographic, industrial, and social transformations in China have given rise to the healthcare industry, which at the same time also gives development opportunities for the real estate industry. However, different from the United States, the healthcare industry in China is state-orchestrated. Integrating the healthcare industry in urban development requires developers to invent innovative strategies to address the state’s interests in the promotion of specific healthcare businesses such as long-term care, private specialty care, and life science research. In addition, due to the land-dependent and speculation-driven nature of China’s urban transformation (He and Lin Citation2015; Lin and Zhang Citation2015), the local states and real estate developers coalesce to use these healthcare businesses to camouflage land-dependent profit-seeking real estate speculation projects. This has yielded a very different type of medical city compared to the medical cities in the United States.

Addressing the complexities in China’s medical city, this paper introduces the medical-university-industry linkage as the framework to study the healthcare industry in China’s transforming urbanism. The medical-university-industry linkage highlights the three-fold processes of promoting the healthcare industry, legitimizing real estate speculation, and consuming urban spaces. Therefore, it is different from the “triple helix” model of university-industry-government for knowledge generation (Etzkowitz Citation2008), or the “industry-university-research” (chan xue yan) for research commercialization (Zhang and Wang Citation2022). This research aims to bridge the healthcare sector and China’s urbanism. It argues that in the medical-university-linkage, the healthcare business in the medical city serves as a “chameleon-like” strategy to justify land appropriation, facilitate place-making, and legitimize profit-seeking real estate speculation. This study then uses the case study of Peking University Healthcare City (PHC) to test the hypothesis and articulate the process of establishing the medical-university-industry linkage.

3. The Peking University health city: case materials and methods

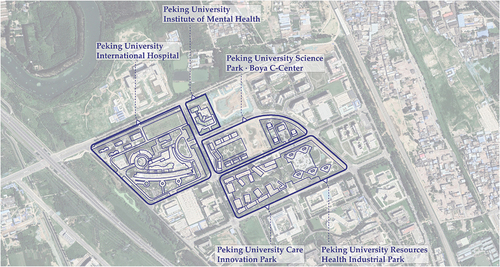

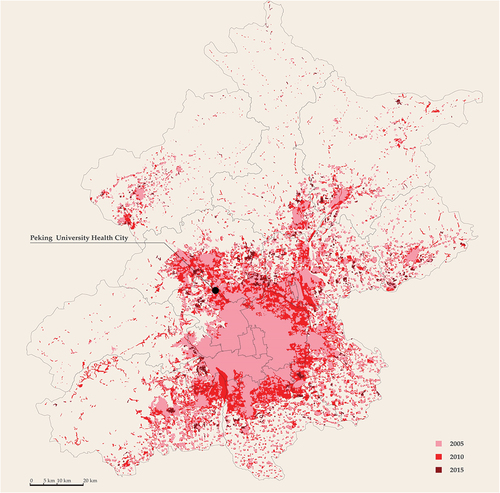

The PHC is a 1,000,000 m2 urban complex located in Changping District on the northwestern side of Beijing. The location was determined by the Beijing municipal government through a free land allotment of A-type administrative and M-type industrial lands (Xu Citation2010). The lands are not entitled to be listed on the land market and the land was given to the PHC for the tax return, talent training, and economic development. illustrates the location of the PHC in Beijing. The core area of Beijing has been almost fully occupied by 2005, leaving little room for development. Thus, land in Beijing is extremely scarce, and it is unlikely to acquire large pieces of land for large development because an equal amount of land could be directly sold to real estate developers which brings a quicker capital return. However, the land is abundant in the Changping District, which is located at the urban edge of Beijing. Its location strategy of developing abundant land at the urban fringe resembles the development strategies of the “new town” and “new city” developments, which are essentially profit-driven speculative land development strategies (Chien Citation2013a; Li, Li, and Wang Citation2014; Lin and Zhang Citation2015).

Figure 1. The built area of Beijing metropolitan region, 2005, 2010, 2015.

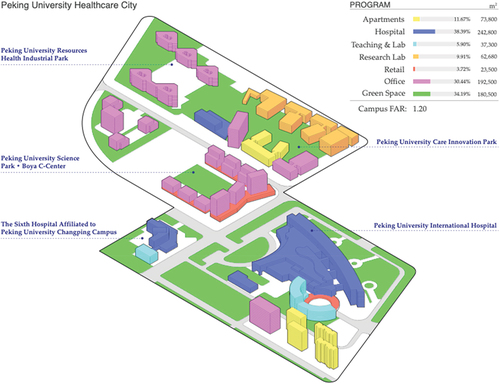

The PHC is an aggregate of five megaprojects. These projects are the Peking University International Hospital, the Peking University Institute of Mental Health (the Sixth Hospital Affiliated to Peking University Changping Campus), the Peking University Science Park • Boya C-Centre, the Peking University Care Innovation Park, and the Peking University Resources Health Industrial Park (). captures the spatial and development information of the five projects in PHC. As a case study, the PHC has unique characteristics. Firstly, among the five projects, except for the Peking University Institute of Mental Health, the other four projects are all developed by the subsidiary private companies of Peking University,Footnote1 and two of them are for-profit commercial office developments. Secondly, the PHC was initiated and driven by Peking University and was expected to become “a station for converting research to industrial products, and a provider for incubation and innovation” (Huaxia Network Citation2017). Therefore, Peking University, Peking University International Hospital, and life science offices coalesced the medical-university-industry linkage. In this linkage, the PHC also provides evidence for profit-driven real estate speculation camouflaged by healthcare businesses.

Table 1. The projects inside the Peking university healthcare city.

Responding to the research question, the case study investigates the programmatic and spatial strategies that integrate the healthcare industry into real estate speculation through the medical-university-industry linkage. The case study is based on multiple sources of primary and secondary materials. Primary materials are collected from the author’s site survey and observation. This is supplemented by secondary materials that are sourced from online articles, datasets, reports, and policy documents published by the government. Based on these materials, the author firstly investigates the differences between the branded uses and actual uses of the individual projects in the PHC to examine the strategies employed by the developers to use healthcare businesses to justify land acquisition and place-making, and camouflage profit-driven real estate speculation. The author then further studies the programmatic and spatial organizations of the PHC to reveal how the medical-university-industry linkage is orchestrated by public and private actors. This is accompanied by a critique of the current form of medical-university-industry linkage and a reimagination of an optimized form of the linkage that could guide future medical city development.

4. Real estate speculation via the medical-university-industry linkage

4.1. Real estate speculation with healthcare businesses

The Peking University International Hospital is the anchor institution (). This 1800-bed general hospital is a private, non-for-profit development. It targets affluent domestic citizens or foreign expatriates including medical tourists who have private insurance or are willing to pay out-of-pocket. Professionals at the PKU International Hospital were recruited from other public and private medical institutes. To compensate for working at a non-public hospital for a non-state-funded job (fei shi ye bian), a higher salary is provided as a financial incentive. However, beneath the medical function, the Peking University International Hospital is a decoy that enables land appropriation and market legitimacy for real estate speculation. As the Chinese state is interested in the development of the healthcare industry and biotechnology self-reliance, Peking University used healthcare businesses to justify free land allotment. The hospital is developed by PKU HEALTHCARE, which is owned by PKU Founder, a private company owned by Peking University. According to You Li, the former CEO of PKU Founder, the hospital was not built for profits. It was built to brand the development as “health care driven” while using Peking University’s brand to profit from other healthcare-related businesses such as pharmaceutical development, medical device, insurance, and senior housing development (Good Fellow Healthcare Citation2014). As shown in , the Peking University International Hospital has operated on deficits. This is because the hospital was not meant to make profits. Instead, it bands healthcare businesses that legitimize real estate speculation.

Figure 3. The Peking University international hospital.

Table 2. The financial performance of the PKU international hospital, 2014–2019.

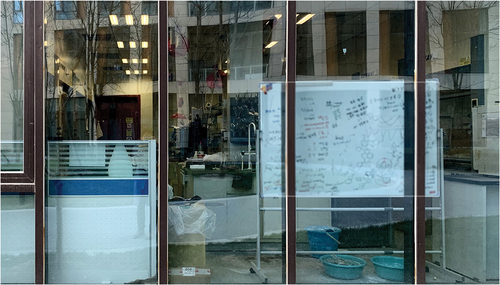

The Peking University Science Park • Boya C-Center (Boya CC) was developed by the Peking University Resources Group, which is also owned by PKU Founder. shows the phase one development. The Boya CC is branded as a life science tech office that integrated conventional offices with “management services” that include technology transfer or leasing services that help the tenants commercialize their research outcomes into marketable products (Sina Real Estate Citation2012). However, although named as a science park that facilitated innovative and entrepreneurial activities, Boya CC is in fact a class-A for-sell commercial office development. According to the real estate agent website, the unit price was 20,000 CNY per square meter (Fangxun Citation2018; Park-China Citation2020). There have even been legal disputes that some of the lands might be illegally used for housing development (Xu Citation2010). The author made multiple visits to the Boya CC between 2019 and 2021 and observed that the vacancy rate is high, and most floor spaces are occupied by non-tech small offices such as K12 education or professional training.Footnote2 The Boya CC has not attracted tech-driven tenants as branded or expected (). Boya CC is therefore a for-profit speculative development disguised under healthcare businesses.

Figure 4. The street view of boya c-center phase 1 development.

Figure 5. The tenants in the podium and office space of the boya CC.

PKU Resources Group also developed the PKU Resources Health Industrial Park (), which recently opened in September 2019. The PKU Resources Health Industrial Park has five buildings which total 59,400 m2 of development on the 58,400 m2 of land. Among the five buildings, two buildings (10,700 m2 and 10,800 m2) will be used as the “headquarters of medical and health service enterprises.” The other three buildings (88,000 m2, 9,200 m2, and 8,300 m2) are headquarters for international pharmaceutical companies. The PKU Resources Health Industrial Park is advertised by PKU Resources Group as a megaproject that “integrates medical care, long-term care, medical teaching, life science research, and incubation.” Similar to Boya CC, although the PKU Resources Health Industrial Park is advertised and branded as a life science tech office complex, it is in fact listed by the real estate agent as a class-A for-rent commercial office development (Park-China Citation2020). Both Boya CC and the PKU Resources Health Industrial Park are developed by PKU Resources Group under a similar strategy – using healthcare businesses to camouflage the real intention of for-profit real estate speculation. This is because the “City-Industry Integration” core business of PKU Resources Group is essentially real estate development (Liu, Liao, and Yu Citation2019). The healthcare business justifies subsidized acquisition of, for example, M-type industrial land,Footnote3 which is usually granted to developers for free or at a substantially subsidized price to build for the tax return, talent training, and economic development.

The PKUCare Innovation Park () was originally named the PKUCare Industrial Park, and the developer was PKUCare Industrial Park Technology Company, which is again established and partially owned by PKU HEALTHCARE thus PKU Founder and Peking University. PKU Founder invested 1.75 billion CNY in 2013 to develop the industrial park, and later PKUCare Industrial Park Technology Company established its fully owned subsidiary company, the PKU Innovation Park Company, to develop the PKUCare Industrial Park. The name of the industrial park was then changed to the current PKUCare Innovation Park. The PKUCare Innovation Park is different from Boya CC and the PKU Resources Health Industrial Park. It is an actual tech office complex for biopharma firms. The author observed ongoing healthcare research activities at the labs during site visits in December 2019 and November 2020 (). The incubation strategy of the PKUCare Innovation Park is to incubate and foster several selected companies to grow into leading firms in the healthcare industry, which then expand their business through mergers and acquisition of other firms and thus become the headquarters for regional growth (Wang Citation2019). It was developed by PKU HEALTHCARE together with the Peking University International Hospital and was expected to take advantage of the reputation and patient and care capacity of the hospital to develop life science research and later-stage research commercialization businesses.

4.2. Establishing the medical-university-industry linkage

The medical-university-industry linkage is reflected in the university- and hospital-led, healthcare-dependent, and real estate-driven strategies of the PHC, where combined forces from various public and private actors have interacted. Firstly, the linkage was established by Peking University (university), which conceived the Peking University International Hospital (medical) driven by the potential of the healthcare industry in China (industry). Specifically, in March 2002, the leadership of Peking University, including the former party secretary Weifang Min, the former president Zhihong Xu, and the former deputy vice-president Qide Han, petitioned the Beijing municipal government for the construction of the hospital (Huaxia Network Citation2017). The construction began in 2002 and the hospital opened in 2014. In 2018, the hospital formally affiliated with the medical school of Peking University and is now known as the 8th Clinical Medical College of Peking University. With this hospital-university affiliation, the international hospital is enabled to run clinical research and apply for research grants. By 2018, the hospital has established more than 120 research projects worth 150 million CNY (MedSci Citation2019). In other words, the healthcare industry (industry) enabled Peking University (university) and the Beijing local government to initiate the hospital (medical), which in return also legitimizes Peking University in the healthcare industry.

Secondly, the medical-university-industry linkage is enabled by both the healthcare and real estate businesses. PKU Founder and its subsidiary companies, which are established and owned by Peking University (university), tied the Peking University International Hospital (medical) with real estate speculation (industry). Specifically, PKU Founder uses healthcare businesses to disguise real estate speculation. PKU Founder established PKU HEALTHCARE to finance and develop the Peking University International Hospital and the PKUCare Innovation Park, which are healthcare-driven developments. PKU Founder also established PKU Resources Group to finance and develop Boya CC and the PKU Resources Health Industrial Park, which are for-profit real estate speculative developments. With the healthcare businesses at Peking University International Hospital and the PKUCare Innovation Park and the “claimed” healthcare businesses at Boya CC and the PKU Resources Health Industrial Park, PKU Founder was able to acquire subsidized M-type industrial land and justify government preferential policies, which are essential for attracting critical early investors (Lerner Citation2015, 157). Particularly for the PKUCare Innovation Park, preferential policies including tax exemption, government subsidies, rewards, and special support for Initial Public Offering were given to the tech tenants (Ministry of Science and Technology Citation2006; PKUCare Industrial Park Citation2013a, Citation2013b, Citation2013c). These policies help the healthcare companies grow, which then further justifies real estate speculation in the urban complex.

Furthermore, shows the spatial organizations of the PHC. Firstly, the Peking University International Hospital consists of spaces for providing care, conducting research, accommodating faculty and student, and hosting administration. Secondly, both the Peking University Science Park • Boya C-Center and the Peking University Resource Health Industrial Park are for-profit commercial office properties developed by PKU Resources Group. On the contrary, the PKUCare Innovation Park is more comprehensive in its program and resembles a research-driven industrial park. It has research labs, office space for incubators, a building occupied by the Peking University Rehab Hospital, and apartments for researchers. It is, therefore, not surprising to observe that the hospital and office spaces each occupy 40% and 30%, respectively, of the total built areas in the PHC urban complex. In the medical-university-industry linkage, the hospital is the decoy that uses the brand of Peking University to make profits from other healthcare-related businesses such as pharmaceutical development, medical device, insurance, and senior housing development (Good Fellow Healthcare Citation2014). Therefore, this spatial organization under the medical-university-industry linkage reflects the “chameleon-like” strategies that justify land appropriation and place-making thus legitimizing profit-accumulation (Chien Citation2013a; Lin and Zhang Citation2015; Wu Citation2015).

Therefore, the medical-university-industry linkage in the PHC is distinct from the conventional production linkages in industrial parks where related industrial production activities concentrate spatially (Gordon and McCann Citation2016), or the conventional real estate speculation based on consumption activities (Hsing Citation2010; Wu Citation2015; Zhao et al. Citation2017). The medical-university-industry linkage embedded in the programmatic and spatial organizations of the PHC integrates the healthcare industry with real estate speculation, while the former contains both production and consumption components. Healthcare embraces the provision of care, medical education, and knowledge generation simultaneously. At the same time, healthcare businesses are used to decoy the profit-driven consumption of spatial production and land in real estate speculation since the state is interested in promoting the healthcare industry that addresses emergent social transformations in China. Together, these dynamic forces in the medical-university-industry linkage yield the medical city as a new form of urbanism. It demands the state, public institutions (hospitals and universities), and developers to collaborate and thus mobilize land, capital, and policy for real estate speculation. Specifically, the university, its medical school, and the hospital together laid the basis for the healthcare industry in the medical city, with which the developers justify land and capital for real estate speculation. At the same time, due to the state’s interests in the healthcare industry, the state also deregulates land supply and grants preferential policies to the developers.

Despite the real estate speculation-driven strategies in the PHC, a similar knowledge- and research-driven nexus that resembles “eds and meds” emerged in the medical-university-industry linkage. The healthcare services provided at the Peking University International Hospital attract patients. The patient volume guarantees clinical research that is reliant on randomized trials. The research capacity attracts more tech-driven tenants, which establishes a supply and demand chain that amplifies the healthcare businesses. This agglomeration of the knowledge economy translates into industrial relatedness that promotes knowledge generation and firm survival (Boschma, Heimeriks, and Balland Citation2014; Guo, Zhu, and He Citation2018), which begets healthcare-driven urbanism. Based on the implications, presents a conceptual diagram for the future medical-university-industry linkage. It highlights the collaboration among universities and research institutions, hospitals, and private companies for knowledge production.

Firstly, the core is the conceptual space for research, which is supported by collaborations among the medical (hospitals), university (and the medical school), and industry (private companies). This space facilitates knowledge-production among different actors. Secondly, the anchoring space at the second ring highlights the knowledge-consumption, which allows the industry and university to commercialize research outcomes into marketable products, which then are consumed at the medical institutions. At the same time, the medical and university institutions together also train talents and professionals for the (healthcare) industry. Thirdly, the peripheral ring is the production space where pharmaceutical and manufacturing plants are located. They produce the marketable products from the anchoring space in a scaled economy and sell them to the larger regional or global markets. Such medical-university-industry linkage optimizes the knowledge-production and knowledge-consumption processes among the public and private actors and thus could serve as the conceptual diagram for the future healthcare-driven urbanism in China.

5. Conclusions

Drawing from the international experience of “eds and meds” in the United States, this research studies the medical city in China’s urban transformation. This research proposes the university-medical-industry linkage as the framework to investigate the roles of the healthcare industry in real estate speculation in the medical city. Due to the land-dependent and speculation-driven nature of the urban development process in China (He and Lin Citation2015; Lin and Zhang Citation2015), large urban projects are “place-making” strategies to facilitate land development and the consumption of space (He and Wu Citation2009; Wang Citation2014). This paper thereby argues that the healthcare industry in China is a localized “chameleon-like” strategy to justify land appropriation and legitimize speculative place-making (Chien Citation2013a; Li, Li, and Wang Citation2014; Wu Citation2015). To test the argument, an empirical investigation is carried out on the case study of Peking University Healthcare City, which is an assemblage of hospitals, for-profit office development, and biopharma tech offices.

The case study suggests two important findings under the medical-university-industry linkage framework. Firstly, the medical-university-industry linkage is the result of the combined forces of Peking University, its subsidiary private companies, and the Peking University International Hospital. These public and private actors orchestrate the linkage to justify subsidized land and the state’s preferential policies. Secondly, the linkage uses healthcare businesses, which stem from the Chinese state’s interests in orchestrating a healthcare industry that addresses emergent demographic, industrial, and social transformations, to legitimize profit-driven place-making and real estate speculation. Specifically, the Peking University International Hospital and the PKUCare Innovation Park brand healthcare businesses in the PHC and camouflage PKU Resources Group’s for-profit commercial projects.

Therefore, this research offers insights into the roles of the healthcare industry in China’s urban transformation. The changing state-market interests and civic-health relations in China require new approaches to urban development that are fundamentally different from the conventional approaches to production-driven industrial parks or consumption-driven real estate development. This yields the medical city as a new urban typology. However, there are limitations to this study. Firstly, the empirical evidence is based on one case study, and the findings may not be generalized and applied to other medical cities. Future studies could be based on more case studies in China and other Asian countries for comparative analysis. Secondly, the method is primarily programmatic and spatial analyses. It is not yet known the specific strategies that developers employ in the making of the medical-university-industry linkages. This could limit our understanding of the public-private interests in the making of the medical city.

To conclude, although real estate speculation has driven urban development and city-making in China for decades and produced miraculous urban spectacles, the emergent demographic, industrial, and social transformations in China highlight the roles of the healthcare industry. However, beyond legitimizing real estate speculation, the healthcare industry could lead to knowledge economy-driven urbanism. This paper further proposes an optimized medical-university-industry linkage that highlights the knowledge-production and consumption linkages, which resemble “eds and meds” and thus could guide future healthcare-driven urbanism in China. This urban future in China requires the state and market, as well as public and private institutions to collaborate, however, beyond real estate speculation.

Acknowledgments

The paper is based on one chapter of Xuanyi Nie’s doctoral dissertation “The Civic Value and Economic Promise of Medical Cities in the United States and China.” The author is grateful to the committee members’ encouragement, guidance, and feedback along the way.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xuanyi Nie

Xuanyi Nie is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and an adjunct lecturer at the Department of Architecture at the National University of Singapore. He obtained the Doctor of Design in urban planning and design from the Harvard Graduate School of Design where his research looked at how cities are related to medical institutions and the healthcare industry in producing specific forms of urban development. His research interests include governing the healthcare industry in urban spaces, urban environments and well-being, neighborhood and community development, and place-making for aging in place and aging well.

Notes

1 The Peking University Institute of Mental Health is a state-funded extension of the Sixth Hospital of Peking University in Haidian District, which is state-funded state-government public hospital. The Peking University Institute of Mental Health is built to improve the provision of healthcare services in Changping District, which is relatively remote from Beijing city center. The state policy document requires a minimum bed number of 270 at the Peking University Institute of Mental Health, while the bed number of the Sixth Hospital of Peking University in Haidian District to limited to 30 (Beijing Municipal Health Commission Citation2020).

2 The author made four visits in total: one in June 2019, one in December 2019, one in November 2020, and the last one in December 2020.

3 In the Code for Classification of Urban Land Use and Planning Standards of Development Land (GB50137-2011), type M industrial land is usually allocated for free or at a substantially subsidized price for 50 years of use.

References

- Bartik, T. J., and G. Erickcek. 2008. The Local Economic Impact of ‘Meds and Eds’: How Policies to Expand Universities and Hospitals Affect Metropolitan Economies. Washington: The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/metropolitan_economies_report.pdf

- Beijing Municipal Health Commission. 2020, May 25. “Beijing Municipal Health Commission Approval on Increasing the Place of Practice in the Sixth Hospital of Peking University.” Documents of Beijing Municipal Health Commission. http://wjw.beijing.gov.cn/zwgk_20040/fgwj/wjwfw/202005/t20200526_1908828.html

- Berg, L. V. D., and H. A. V. Klink. 1996. “Health Care and the Urban Economy: The Medical Complex of Rotterdam as a Growth Pole?” Regional Studies 30 (8): 741. doi:10.1080/00343409612331350028.

- Boschma, R. A., G. Heimeriks, and P.-A. Balland. 2014. “Scientific Knowledge Dynamics and Relatedness in Biotech Cities.” Research Policy 43 (1): 107–114. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.07.009.

- Chang, I.-C.-C., H. Leitner, and E. Sheppard. 2016. “A Green Leap Forward? Eco-State Restructuring and the Tianjin-Binhai Eco-City Model.” Regional Studies 50 (6): 929–943. doi:10.1080/00343404.2015.1108519.

- Chien, -S.-S. 2013a. “Chinese eco-cities: A Perspective of land-speculation-oriented Local Entrepreneurialism.” China Information 27 (2): 173–196. doi:10.1177/0920203X13485702.

- Chien, -S.-S. 2013b. “New Local State Power through Administrative Restructuring – A Case Study of post-Mao China county-level Urban Entrepreneurialism in Kunshan.” Geoforum 46: 103–112. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.12.015.

- Chien, -S.-S., and M. D. Woodworth. 2018. “China’s Urban Speed Machine: The Politics of Speed and Time in a Period of Rapid Urban Growth.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42 (4): 723–737. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12610.

- Dou, G., Q. Wang, and X. Ying. 2018. “Reducing the Medical Economic Burden of Health Insurance in China: Achievements and Challenges.” BioScience Trends 12 (3): 215–219. doi:10.5582/bst.2018.01054.

- Duckett, J. 2011. The Chinese State’s Retreat from Health: Policy and the Politics of Retrenchment. London: Routledge.

- Erickson, R. A., N. I. Gavin, and S. M. Cordes. 1986. “The Economic Impacts of the Hospital Sector.” Growth and Change 17 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2257.1986.tb00929.x.

- Etzkowitz, H. 2008. The Triple Helix : University-industry-government Innovation in Action. New York: Routledge.

- Fangxun. 2018, August 17. “Peking University Science Park Boya C-Center.” Fangxun Offices. http://www.funxun.com/fczy/office/118513_1.html

- Feng, Z., E. Glinskaya, H. Chen, S. Gong, Y. Qiu, J. Xu, and W. Yip. 2020. “Long-term Care System for Older Adults in China: Policy Landscape, Challenges, and Future Prospects.” The Lancet (British Edition) 396 (10259): 1362–1372. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32136-X.

- Feng, Z., H. J. Zhan, X. Feng, C. Liu, M. Sun, and V. Mor. 2011. “An Industry in the Making: The Emergence of Institutional Elder Care in Urban China.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS) 59 (4): 738–744. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03330.x.

- Good Fellow Healthcare. 2014, December 31. “Li You, the CEO of PKU Founder: The Peking University International Hospital Is the Foundation for Profits.” Good Fellow Hospital News. http://www.gf-healthcare.com/hospital_news.php?classid=26&viewid=1150

- Gordon, I. R., and P. McCann. 2016. “Industrial Clusters: Complexes, Agglomeration And/or Social Networks?” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 37 (3): 513–532. doi:10.1080/0042098002096.

- Governa, F., and A. Sampieri. 2020. “Urbanisation Processes and New Towns in Contemporary China: A Critical Understanding from A Decentred View.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 57 (2): 366–382. doi:10.1177/0042098019860807.

- Guo, Q., S. Zhu, and C. He. 2018. “Industry Relatedness and New Firm Survival in China: Do Regional Institutions and Firm Heterogeneity Matter?” Post-communist Economies 30 (6): 735–754. doi:10.1080/14631377.2018.1443253.

- Harkavy, I., and H. Zuckerman. 1999. Eds and Meds: Cities Hidden Assets. Washington: The Brookings Institution.

- He, S., and G. C. S. Lin. 2015. “Producing and Consuming China’s New Urban Space: State, Market and Society.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 52 (15): 2757–2773. doi:10.1177/0042098015604810.

- He, S., L. Li, Y. Zhang, and J. Wang. 2018. “A Small Entrepreneurial City in Action: Policy Mobility, Urban Entrepreneurialism, and Politics of Scale in Jiyuan, China.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42 (4): 684–702. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12631.

- He, S., and F. Wu. 2005. “Property-led Redevelopment in post-reform China: A Case Study of Xintiandi Redevelopment Project in Shanghai.” Journal of Urban Affairs 27 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/j.0735-2166.2005.00222.x.

- He, S., and F. Wu. 2009. “China’s Emerging Neoliberal Urbanism: Perspectives from Urban Redevelopment.” Antipode 41 (2): 282–304. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2009.00673.x.

- Hsing, Y.-T. 2010. The Great Urban Transformation: Politics of Land and Property in China. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Huaxia Network. 2017, September 18. “Peking University Health City: A New Example of Medical Industry Ecological Cluster.” China Net. http://www.huaxia.com/tslj/flsj/fw/2017/09/5473110.html

- Jin, H., Y. Qian, and B. R. Weingast. 2005. “Regional Decentralization and Fiscal Incentives: Federalism, Chinese Style.” Journal of Public Economics 89 (9): 1719–1742. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.11.008.

- Lauermann, J. 2018. “Municipal Statecraft: Revisiting the Geographies of the Entrepreneurial City.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (2): 205–224. doi:10.1177/0309132516673240.

- Lerner, J. 2015. “Entrepreneurship, Public Policy, and Cities.” In The Urban Imperative: Towards Competitive Cities, E. L. Glaeser, A. Joshi-Ghani, & World Bank (Eds.) New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press. p. 149–172.

- Lichtenberg, E., and C. Ding. 2009. “Local Officials as Land Developers: Urban Spatial Expansion in China.” Journal of Urban Economics 66 (1): 57–64. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2009.03.002.

- Li, Z., X. Li, and L. Wang. 2014. “Speculative Urbanism and the Making of University Towns in China: A Case of Guangzhou University Town.” Habitat International 44: 422–431. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.08.005.

- Lin, G. C. S., and A. Y. Zhang. 2015. “Emerging Spaces of Neoliberal Urbanism in China: Land Commodification, Municipal Finance and Local Economic Growth in prefecture-level Cities.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 52 (15): 2774–2798. doi:10.1177/0042098014528549.

- Liu, J., Z. Liao, and X. Yu. 2019. “Duoyuanhua Chengdu Yu Neibu Ziben Shichang Peizhi Xiaolv Guanxi Yanjiu - Yi Fangzheng Jituan Weili [Research on the Relationship between the Degree of Diversification and the Allocation Efficiency of Internal Capital Market: A Case Study of Founder Group].” Kuai Ji Zhi You (Friends of Accounting), no. 4: 101–107.

- Luk, S. C. Y. 2017. Financing Healthcare in China: Towards Universal Health Insurance. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge.

- MedSci. 2019, January 23. “Building the Model of Integration of Industry, University, and Research through PKU HEALTHCARE.” MedSci. https://m.medsci.cn/index.do

- Ministry of Science and Technology. 2006, December 12. “Measures for the Identification and Management of Science and Technology Business Incubators (High Tech Entrepreneurship Service Center) GuoKeFaGaoZi [2006] No. 498.” Special Column of Detailed Planning Policies. http://www.most.gov.cn/ztzl/gjzctx/ptzckjcx/200802/t20080222_59218.htm

- Montinola, G., Y. Qian, and B. R. Weingast. 1995. “Federalism, Chinese Style: The Political Basis for Economic Success in China.” World Politics 48 (1): 50–81. doi:10.1353/wp.1995.0003.

- Oi, J. C. 1992. “Fiscal Reform and the Economic Foundations of Local State Corporatism in China.” World Politics 45 (1): 99–126. doi:10.2307/2010520.

- Park-China. 2020, January 2. “The PKU Resources Health Industrial Park.” Industrial Parks. http://www.park-china.com/plus/view.php?aid=684

- PKUCare Industrial Park. 2013a, August 27. “Interim Measures for Patent Subsidies and Awards in Changping District.” PKUCare Industrial Park. http://www.pkucarepark.com/second/content.aspx?nodeid=17&page=ContentPage&contentid=282

- PKUCare Industrial Park. 2013b, August 27. “Opinions on Encouraging Enterprises to Cooperate with Universities and Scientific Research Institutes in Beijing.” PKUCare Industrial Park. http://www.pkucarepark.com/second/content.aspx?nodeid=17&page=ContentPage&contentid=260

- PKUCare Industrial Park. 2013c, August 27. “Zhongguancun National Independent Innovation Demonstration Zone Supporting Enterprise Restructuring and Listing Subsidy Fund Management Measures.” PKUCare Industrial Park. http://www.pkucarepark.com/second/content.aspx?nodeid=17&page=ContentPage&contentid=234

- Porter, M. E. 2016. “Inner-City Economic Development: Learnings from 20 Years of Research and Practice.” Economic Development Quarterly 30 (2): 105–116. doi:10.1177/0891242416642320.

- Ruoppila, S., and F. Zhao. 2017. “The Role of Universities in Developing China’s University Towns: The Case of Songjiang University Town in Shanghai.” Cities 69: 56–63. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.05.011.

- Schmid, R. D., and X. Xiong. 2021. “Biotech in China 2021, at the Beginning of the 14th five-year Period (“145”).” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 105 (10): 3971–3985. doi:10.1007/s00253-021-11317-8.

- Shen, J. 2022. “Universities as Financing Vehicles of (Sub)urbanisation: The Development of University Towns in Shanghai.” Land Use Policy 112: 10467. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104679.

- Simpson, A. T. 2019. The Medical Metropolis: Health Care and Economic Transformation in Pittsburgh and Houston. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Sina Real Estate. 2012, August 10. “Peking University Science Park • Boya C-Center International Opening Ceremony.” Leju Maifang. https://m.leju.com/news-bj-5905659428983845703.html

- State Council of China. 2013a, September 13. “Opinions on Accelerating the Development of Aged Care Services [2013] No. 35.” Documents of the State Council. http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2013-09/13/content_2487704.htm

- State Council of China. 2013b, October 18. “Opinions on Promoting the Development of Health Service Industries GuoFa [2013] No. 40.” Documents of the State Council. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2013-10/18/content_6067.htm

- State Council of China. 2019a, July 9. “Healthy China Action (2019-2030).” Healthy China action Promotion Committee. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-07/15/content_5409694.htm

- State Council of China. 2019b, April 16. “Opinions on Promoting the Development of Aged Care Services GuoFa [2019] No. 5.” Documents of the State Council. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-04/16/content_5383270.htm

- Su, X., and Z. Qian. 2020. “Neoliberal Planning, Master Plan Adjustment and Overbuilding in China: The Case of Ordos City.” Cities 105: 102748. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2020.102748.

- Theurillat, T., and F. G. Bideau. 2022. “China’s Extended Urbanization Driven by the “Consumption City” in the Context of Financialized Ecological Civilization.” Transactions in Planning and Urban Research 1–15. doi:10.1177/27541223221101720.

- Theurillat, T., J. H. Lenzer, and H. Zhan. 2016. “The Increasing Financialization of China’s Urbanization.” Issues and Studies - Institute of International Relations 52 (4): 1640002. doi:10.1142/S1013251116400026.

- Walder, A. G. 1995. “Local Governments as Industrial Firms: An Organizational Analysis of China’s Transitional Economy.” The American Journal of Sociology 101 (2): 263–301. doi:10.1086/230725.

- Wang, L. 2014. “Forging Growth by Governing the Market in reform-era Urban China.” Cities 41 (b): 187–193. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2014.02.008.

- Wang, F. 2019, July 26. “Highlight the Strategy of Science and Technology Innovation to Serve the PKUCare Innovation Park and Focus on a ‘New Start’.” CN-HealthCare. https://www.cn-healthcare.com/article/20190726/content-521835.html

- Wang, L., C. Potter, and Z. Li. 2014. “Crisis-induced Reform, state–market Relations, and Entrepreneurial Urban Growth in China.” Habitat International 41: 50–57. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.06.008.

- Winant, G. 2021. The Next Shift : The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Wu, F. 1999. “The ‘Game’ of Landed-Property Production and Capital Circulation in China’s Transitional Economy, with Reference to Shanghai.” Environment & Planning A 31 (10): 1757–1771. doi:10.1068/a311757.

- Wu, F. 2002. “China’s Changing Urban Governance in the Transition Towards a More Market-oriented Economy.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 39 (7): 1071–1093. doi:10.1080/00420980220135491.

- Wu, F. 2015. Planning for Growth: Urban and Regional Planning in China. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wu, F. 2018. “Planning Centrality, Market Instruments: Governing Chinese Urban Transformation under State Entrepreneurialism.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 55 (7): 1383–1399. doi:10.1177/0042098017721828.

- Wu, F. 2020. “The State Acts through the Market: ‘State Entrepreneurialism’ beyond Varieties of Urban Entrepreneurialism.” Dialogues in Human Geography 10 (3): 326–329. doi:10.1177/2043820620921034.

- Xinhua News Agency. 2014, August 27. “Li Keqiang Chaired a State Council Executive Meeting and Determined to Accelerate the Development of Private Health Insurance.” Xinhua News. http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2014-08/27/c_1112255755.htm

- Xu, G. 2010, March 24. “Land for Scientific Research ‘Changes Face’.” Sina. http://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/20100324/21207626129.shtml

- Yeh, A. G.-O., and F. Wu. 1996. “The New Land Development Process and Urban Development in Chinese Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 20 (2): 330–353. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.1996.tb00319.x.

- Yip, W., H. Fu, A. T. Chen, T. Zhai, W. Jian, R. Xu, J. Pan, et al. 2019. “10 Years of Health-care Reform in China: Progress and Gaps in Universal Health Coverage.” The Lancet (British Edition) 394 (10204): 1192–1204. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32136-1.

- Yip, W., and W. C. Hsiao. 2015. “What Drove the Cycles of Chinese Health System Reforms?” Health Systems & Reform 1 (1): 52–61. doi:10.4161/23288604.2014.99500.

- Yip, W., W. C. Hsiao, Q. Meng, W. Chen, and X. Sun. 2010. “Realignment of Incentives for health-care Providers in China.” The Lancet (British Edition) 375 (9720): 1120–1130. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60063-3.

- Zhang, T. 2002. “Urban Development and a Socialist Pro-Growth Coalition in Shanghai.” Urban Affairs Review (Thousand Oaks, Calif.) 37 (4): 475–499. doi:10.1177/10780870222185432.

- Zhang, X. 2005. “Development of the Chinese Housing Market.” In Emerging Land and Housing Markets in China, edited by C. Ding and Y. Song, 183–198. Cambridge, Mass: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Zhang, S., and X. Wang. 2022. “Does Innovative City Construction Improve the industry–university–research Knowledge Flow in Urban China?” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 174: 121200. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121200.

- Zhao, S. X., J. L. Ching, Y. He, and N. Y. M. Chan. 2017. “Playing Games and Leveraging on Land: Unfolding the Beijing Olympics and China’s Mega-event Urbanization Model.” Journal of Contemporary China 26 (105): 465–487. doi:10.1080/10670564.2016.1245896.

- Zhu, J. 2004. “Local Developmental State and Order in China’s Urban Development during Transition.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28 (2): 424–447. doi:10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00527.x.

- Zhu, J. 2005. “A Transitional Institution for the Emerging Land Market in Urban China.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 42 (8): 1369–1390. doi:10.1080/00420980500150714.

- Zou, Y. 2021. “Capital Switching, Spatial Fix, and the Paradigm Shifts of China’s Urbanization.” Urban Geography, ahead-of-print ahead-of-print 1–21. doi:10.1080/02723638.2021.1956111.