ABSTRACT

This research aims to analyze and synthesize the aspects of traditional Sundanese architecture relevant to the need for the creative adoption of early child-friendly school designs and to develop a design model for early child-friendly schools based on the adoption of Sundanese architecture. Furthermore, the descriptive qualitative method and the research design method were used to develop design models for early child-friendly schools. Also, ethno-architectural and qualitative approaches were used in observing, analyzing, and qualitatively interpreting the local-traditional Sundanese architecture. In addition, these models were further explored for creative adoption designs in developing architectural designs for early childhood friendly schools through the DBR (Design Based Research) method. The results are in the form of parameters, design principles, and architectural adaptation and adoption frameworks, which are then applied to early child-friendly schools based on Sundanese architecture on centralized land using the Gajah Palisungan pattern and the Masagi-Ngariung form.

1. Background

Early childhood is the golden age when children’s education begins, and they are sensitive to environmental stimuli. The sensitive phase is characterized by a functional, psychological, and physical maturity that readily reacts to the stimuli provided by the environment (Breiner, Ford, Gadsden, Citation2016; Lee Citation2013; Machfudzoh, Purwoko, Yani, Citation2020; Thomas, Michael., Johnson, Mark H., Citation2008). Therefore, the environment must be conditioned to positively and optimally support exploring children’s sensory, motor, cognitive, language, social, psychological, and religious values (Yamin and Sabri Citation2013; Musyarofah Citation2017).

The first and most important environment of a child is undoubtedly the immediate family. Furthermore, the natural parental model of the family environment will largely determine the stages and conditions for optimizing the growth and development of children (Mahak Citation2019). The next environment is school (Kaulina, Barliana, Megayanti, Citation2020), including Early Childhood Education schools (PAUD), which occupies a strategic position plays a significant role in supporting growth and development. It means that early childhood education schools must be conditioned and well developed to have high-quality curriculum, teachers, counseling services, learning processes, and educational facilities.

The reality is that there are several difficulties faced with early childhood education in Indonesia. In addition to minimal and non-standardized educational institutions, early childhood education lacks standard teacher qualifications and competencies because only 23.06% have undergraduate education. Also, the poor quality of institutional programs; and family involvement in ways inconsistent with these programs has stunted the growth of this form of education.

Furthermore, low service coverage has left only one-third of children aged 3–6 years receiving childhood education.

Moreover, the primary goal of Early Childhood Education, which is intended to develop attitudes and character, is still primarily focused on learning how to read and write with an academic nuance.

This research focuses on the quality of school facilities and infrastructure. Hence, schools should meet the required physical standards and be friendly enough for early childhood education.

From some of the research works derived from local/traditional architectural wisdom regarding child-friendly school architecture, much evidence suggests that conventional local architecture has many advantages, including responsiveness to nature, sensitivity to diversity, the intensity of social space, sensitivity to emotional feelings, and attachment, and identifying with the place (Barliana, Citation2014; Salura Citation2008; Cahyani, Citation2020).

Furthermore, amid globalization of information alongside foreign cultural pressures, it is also essential to introduce the local context, place identity, and local cultural roots to children early. Thus, local/traditional architecture is an effective vehicle that supports these efforts. Based on this background, this research aims to develop principles and design models for early childhood friendly schools based on the creative adoption of traditional Sundanese architecture.

This theoretical research is based on the concept that since early childhood is the initial period of human development, it is crucial in developing multi-intelligence. It is also an exploration period where they develop various interests and the ability to adapt through observing their surrounding environment (Watson Citation2016). Therefore, the environment strongly influences children’s mental strength and character traits. Additionally, all the information and environmental stimuli received by children are quickly absorbed; this could significantly impact their lives (Laurens Citation2004). Children use schema, assimilation, accommodation, organization, and equilibration to actively understand their world. With this ability, toddlers will explore their surroundings and make it the foundation for further knowledge about the world, which turns into more advanced and complex skills. (Murniarti Citation2020).

Therefore, child-friendly schools are essential in supporting the growth and development of early childhood. On that basis, The Children Friendly School (CFS) model was developed by UNICEF (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund), using the child-friendly concept to provide safe and protected schools, trained educators, adequate resources, and a suitable learning environment. The women’s empowerment and child protection ministry defined child-friendly schools as formal, non-formal, and informal education that is safe, clean, healthy, caring, and has the environment’s culture. It should also be capable of guaranteeing, fulfilling, and respecting children’s rights while protecting them from violence, discrimination, and other ill-treatment. Furthermore, it should support children’s participation, especially in planning, policy, learning, monitoring, and complaint mechanisms related to fulfilling children’s rights and protection in education. Kementrian PPPA (Citation2015).

According to the deputy minister for child development under the Kementrian PPPA (Citation2015), the establishment and development of the child friendly school are based on the following principles: Non-discrimination, best interests of the child; life, survival, and development; respect for children’s views; and, good management.

The study of the development of traditional architecture, specifically, Sundanese architecture, still exists in traditional villages. Furthermore, it is one of the manifestations and expressions of community culture that has been around for a long time. According to Barliana, Cahyani (Citation2014), traditional villages are resilient enough to withstand various changes with diverse local knowledge and wisdom.

Local wisdom as a cultural heritage must be explored and examined continuously. This exploration of cultural roots and local wisdom is essential in gaining knowledge of traditional architecture’s values, cultural patterns, and characteristics. This exploration preserves the heritage and cultural inheritance and is also creatively adapted for contemporary culture development. (Dwidayati, Barliana, Cahyani, Citation2020). It also includes adopting Sundanese architecture’s values, patterns, and characteristics to develop architectural and interior designs for early Childhood-friendly schools.

In general, the concept of traditional architecture emphasizes nature as its centerpiece. Cosmologically, traditional societies live together with nature and the invisible world. Therefore, most of the basic concepts of conventional architectural buildings (in the form of regional arrangements, spatial planning, building forms, etc.) come from nature, which is reflected through myths, taboos, symbolism, and tradition (Barliana, Cahyani, and Mardiana Citation2020).

Traditional architecture is a manifestation of cultural elements that grow and evolves along with the tribe and eventually become the identity of the tribe (Rahmansah and Rauf Citation2014). Additionally, traditional Sundanese architecture has the basic concept of blending with nature, which the Sundanese people regard as a potential or strength that must be respected and utilized appropriately in everyday life (Suharjanto Citation2014).

In terms of village patterns, the topography of Sundanese villages is divided into longitudinal or linear settlements, centralized settlements, and downhill settlement Patterns (Kustianingrum et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, a linear settlement pattern is a group of settlements built in a flexible line, depending on the natural surroundings or the prevailing community system. Usually, the houses are positioned in a pattern following the flow of the river, the highway, the shoreline, etc.

Furthermore, the centralized settlement pattern is a collection of settlements surrounding a large and dominant centralized area. In this case, settlements surround a square, village halls, open fields, and other public spaces that unite existing houses. Meanwhile, a horizontal settlement pattern is a residential group that combines linear and centralized patterns. Here, houses are built along the perimeter of the road with their design adapted to the needs, functions, and conditions of the natural environment. In addition, the pattern of houses is usually elongated along a flexible line but has a center point in the direction of the line.

The characteristics of the natural environment of the Sundanese Tatar give the traditional Sundanese people a poetic idea of classifying village lands that are good enough for inhabitation. Additionally, Murtiyoso (Citation1989), mentioned six land typologies that are good for inhabitation, includes Galudra Ggupuk (Cupping Eagle Wings), Pancuran Emas (Golden Showers), satria lalaku ((Adventorous Knight), Kancah Nangkub (Pan Facedown), Gajah Palisungan (Elephant Sitting), and Bulan Purnama (Full Moon). These land are perceived to bring safety, health, prosperity, and honor. On the contrary, the three other typologies, including galagah katunan, cagak gunting, and jalan ngolece, were considered unsuitable for living because they bring misery, disease, and other forms of distress. Additionally, Galudra ngupuk, as shown in , is a term for a village between two hills or two mountains. Traditional Sundanese people believe that this form of land brings enormous wealth.

Pancuran emas is a term for a village located on a hillside or mountain slope whose building orientation is southwest. The illustration is shown in below:

Satria lalaku is a term for a village located on the slopes of a hill or mountain whose building orientation is to the southeast.

The representation can be seen in .

Kancah Nangkub or upturned pan, is a term for a village located on a hill, and its visualization is presented in .

Gajah palisungan is a term for a village located on a hill, where the land is flat, and its depiction is exhibited in .

Bulan purnama or the full moon is a term for a village located in a river valley. The pattern can be observed in below:

2. Research method

This research uses two approaches, namely the qualitative descriptive and research design method, to develop the design model. Also, the ethno-architecture qualitative approach is used for observation, analysis, and qualitative interpretation of local-traditional Sundanese architecture. Furthermore, this approach was further explored for creative adoptive designs in developing architectural plans for early child-friendly schools through the DBR (Design-Based Research) method.

According to Amiel and Reeves (Citation2008), the DBR stages are:

Problem identification and analysis.

Solution design.

Iterative test cycle and design refinement.

Reflection to produce design and implementation principles.

Preliminary studies were conducted in three Early Childhood Education schools, namely SBB Al-Hikmah (West Bandung), Mutiara Integrated Islamic Kindergarten (Cimahi), and Lab school UPI Kindergarten (Bandung).

The adoption of Sundanese architecture is limited to aspects of processed location or master plan, zoning, space, architectural forms, and structures. The following are six techniques used in adopting architectural design (Roesmanto, Citation2007; Nugraha Citation2019):

Give a similar impression.

Replicate the characteristics of the reference architecture

Take the same meaning

Explore architectural forms and spaces.

Combine building forms and structures.

Use a similar concept.

3. Research results and discussion

The results were presented and developed as a tool for adapting and adopting traditional Sundanese architecture into contemporary architecture for child-friendly schools. The aspects examined include land pattern (), building layout (), roof shape (), building structure (), and spatial organization ().

Table 1.. Adaptation and design adoptive techniques: land pattern.

Table 2. Design adaptation and adoption techniques: building layout.

Table 3. Design adaptation and adoption techniques: roof form.

Table 4. Design adaptation and adoption techniques: building structure.

Table 5. Design adaptation and adoption techniques: space organization.

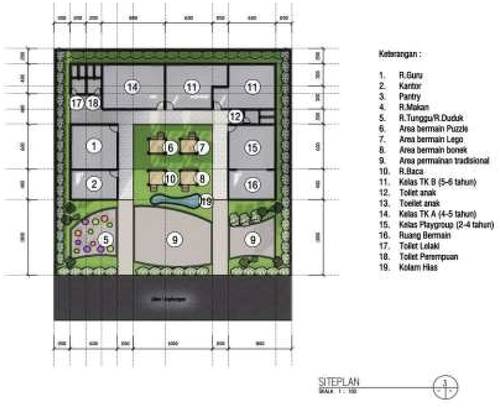

This research has also developed school design for three early child-friendly schools based on traditional architecture, including schools on centralized land with the Gajah Palisungan pattern and MasagiNgariung (Surounding-Square) form, schools on centralized cand with Nangkub or Galudra Ngupuk pattern and Buleud Ngariung form, and schools on organic land with Satria Lalaku or Pancuran Emas pattern. Therefore, only one school design model will be presented in this paper: the Early Child friendly school based on Sundanese architecture on centralized land with the Gajah Palisungan pattern and the MasagiNgariung form.

Gajah Palisungan (Elephant sitting) is a village with flat land on a hill. According to the concept of environmental conservation laws closely related to Sundanese customs, this land pattern does not require excessive land engineering, except for land clearing. Subsequently, the layout pattern of ngariung (gathering), adapts well to the Sundanese community; who are a sociable population because it provides space for social interaction (See: ). Moreover, the pattern of Masagi (square or rectangle) aligns with Sundanese philosophy, which is the phrase “Hirup kudu masagi” (life must be solid or perfect) or “jadi jelema masagi” (be solid or perfect human) (Natawisastra Citation1979). It signifies that people must be versatile, possess many abilities, and have no shortcomings in their living.

Figure 7. Masterplan with a centralized pattern on the Gajah Palisungan land and the Masagi-Ngariung form.

The zoning pattern and building space holy, clean, and dirty areas. These three areas organization in the master plan adapt are divided into administrative, academic, Sundanese cosmology on a horizontal scale, support, and service areas (See: ).

Including the front, middle, and back areas;

The administration area consists of the principal/deputy principal’s office, management staff, and teacher’s offices. The academic area consists of a playgroup class (2–4 years old), a kindergarten A class (4–5 years old), a kindergarten B class (5–6 years old), reading room, puzzle play area, doll-play area, lego-play area, and traditional-game area. The supporting areas are the dining room, sitting room/waiting house, and ornamental fish pond. The service area consists of a pantry, boys’ toilets, girls’ toilets, male staff/teacher toilets, and female staff/teacher toilets.

The roof shape of the main building adapts and adopts the form of the atak Julangngapak, which is distilled and modified. (See: ) In comparison, the shape of the playroom takes the form of a jure or parahu kumureb. In terms of structure, the main building uses a depok or ngupuk structure, while the play area uses a stage structure. The stage structure follows the cosmology of the Sundanese community, about the upper world (where God, the creator resides), the middle world/stage (where humans live), and the underworld/hollow (place of the animal, dirty, and death area).

The basic principles that accompany the design model of the school are based on five things. First, the master plan is designed with compact mass processing. Also, the origin of Sundanese architecture is generally located in an extensive area. However, the land has become increasingly limited and expensive in today’s contemporary environment. Additionally, the master plan is compact but still provides an open public playful space relevant to the Sundanese and child-friendly architecture characteristics. Also, the available space and playroom will be filled with varieties of engaging, exploratory, and interactive traditional Sundanese games. Secondly, the playroom areas’ land zoning pattern and stage structure follow the desacralized cosmological trilogy about a horizontal scale, namely the sacred, clean, and dirty areas, and a vertical scale, namely the upper world, the middle world, and the underworld. These trilogies are physically and aesthetically adapted that their symbolic and cosmological meaning is no longer the primary reference.

Education School Area

Thirdly, the stage structure in the playroom and reading room area was designed with the safety of early childhood in mind. Also, the height level is relatively low, and a transparent fence/barrier is created. Therefore, the character of Sundanese architecture does not limit the space for movement and exploration of early childhood.

Fourthly, the roof’s main structure adapts to the typical shape of the Sundanese julangapak, and reacts to the tropical climate. The combination of steep and sloping roof levels gives the building an elevated appearance, making the school an easily recognizable landmark.

Finally, suppose the curriculum is on a higher macro-level and not limited to the structure or learning program; in that case, the parental factor is part of the unseen curriculum in early childhood schools. Therefore, Schools should provide space that serves as a waiting room for parents to have conversations and initiate productive activities. In addition, parents should have access to the reading rooms, or take part in learning using traditional game media.

Therefore, the developed design model has shown that traditional architecture, especially Sundanese architecture, remains relevant and can be explored and adapted to contemporary architectural design. (See: ). Early child-friendly school designs, based on traditional Sundanese architecture, can be conditioned to positively and optimally support the exploration of childrens’ sensory, motor, cognition, language, social, psychological, and religious values.

4. Conclusions and recommendations

a. Conclusion

This research has produced a tool for adapting and adopting traditional Sundanese architecture to contemporary architecture for early child-friendly schools. The aspects examined include land patterns, building layouts, roof shapes, building structures, and spatial organization.

Furthermore, the design model developed has shown that traditional architecture, especially Sundanese architecture, remains relevant and can be explored and adapted for contemporary architectural design. Early child-friendly school designs, based on traditional Sundanese architecture, can be conditioned to optimally and positively support the exploration of childrens’ sensory, motor, cognition, language, social, psychological, and religious values.

b. Recommendation

The revival of the wealth of traditional architecture and policymakers, such as educational officers, can promote school infrastructure by adapting and adopting the design principles and values of Sundanese architecture. Additionally, architects should be encouraged to design child-friendly schools and explore the wealth of traditional architecture. Finally, school leaders, teachers, and students can appreciate and implement an early child-friendly school based on traditional architecture.

Acknowledgments

The authors consisting of: M. Syaom Barliana, as a Professor at Architectural Education Departement and Expert Commitee and Researcher at CoE of Technical and Vocational Education and Training Research Center (TVET RC), Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia; Mirna Purnama Ningsih as Lecturer at Home Economic Education, Faculty of Technology and Vocational Education, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia; Indah Susanti, as Lecturer at Architectural Education Departement, Faculty of Technology and Vocational Education, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia. The authors are grateful to the Chairperson of the Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia for funding this research work. We are also thankful to the owners, principals, deputy principals, and school teachers of Early Childhood Education who became informants and respondents for this research. The schools are SBB Al Hikmah (West Bandung), Integrated Islamic Kindergarten Mutiara (Cimahi), and UPI Lab school Kindergarten (Bandung).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amiel, T., and T. C. Reeves. 2008. “Design-Based Research and Educational Technology: Rethinking Technology and the Research Agenda. Educational Technology & Society. Vol. 11, No. 4 (October 2008).” International Forum of Educational Technology & Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/

- Barliana, M. S., and D. Cahyani. 2014. “Learning Pattern of Inheritance Tradition of Sustainable Architecture: From Ethnoarchitecture to Ethnopedagogy.” Tawarikh Journal.

- Barliana, M. S., D. Cahyani, and R. Mardiana. 2020. “Creative Adoption of Sundanese Traditional Architecture for Architectural and Campus Interior Design Development. IOP Conf.” IOP Publishing. 830: 022064. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/830/2/022064.

- Breiner, H., M. Ford, and V. L. Gadsden, editors. 2016. Parenting Matters: Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0-8. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

- Cahyani, D., A. Sudikno, and B. Fauzy. 2020. “Examining The Spatial Pattern In Indonesia’s Villages For The Globalization Mechanism Of Survival.” Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Special Issue on AASSEEEC2020, December 30 - 38. School of Engineering, Taylor’s University.

- Dwidayati, K. H., M. S. Barliana, D. P. Cahyani, I. Susanti, and T. Ramadhan. 2020. “Acculturation of Colonial and Traditional Sundanese Architecture on the Facades of Educational Buildings as Formers of Identity and Visual Character in UPI Purwakarta Campus.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Volume 738, The 20th Sustainable, Environment and Architecture 10 November 2020, Indonesia

- Kaulina, Q., M. S. Barliana, and T. Megayanti. 2020. “Development Of Architectural Design Principle Of Autism Student’s Classroom At Inclusion School.” International Conference. The 6th UPI Tvet Conference 2020 In Conjunction With The 5th ICIET RMUTT, Bandung, Indonesia.

- Kementerian-PPPA. 2015. Panduan Sekolah Ramah Anak Deputi Tumbuh Kembang Anak.

- Kustianingrum, D., O. Sonjaya, and Y. Ginanjar. 2013. “Kajian Pola Penataan Massa Dan Tipologi Bentuk Bangunan Kampung Adat Dukuh Di Garut Jawa Barat.” 1 (3): 1–13.

- Laurens, J. M. 2004. Arsitektur Dan Perilaku Manusia. Jakarta: PT Grasindo.

- Lee, P. 2013. “Cognitive Development in Bilingual Children: A Case for Bilingual Instruction in Early Childhood Education.” Bilingual Research Journal 20 (3): 499–522. doi:10.1080/15235882.1996.10668641. May 2013.

- Machfudzoh, L. F., B. Purwoko, and M. T. Yani. 2020. “The Effect of Expression Box Media on the Ability to Express Language and Self-Confidence in Group B Children in AR Rasyid Kindergarten Sidoarjo.” International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 10 (1, January): 97100. doi:10.29322/IJSRP.10.01.2020.p97100.

- Mahak, A. 2019. “Factors that Affect Growth and Development in Children.” Avalliable at: https://parenting.firstcry.com/

- Murniarti, E. 2020. “Bahan Ajar.” Invertebrate Neuroscience: IN 20 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1007/s10158-019-0234-x.

- Murtiyoso, S. 1989. “Klasifikasi Lahan Pada Masyarakat Sunda Kuno, Majalah Sasakala LSAI.”

- Musyarofah. 2017 June. “Pengembangan Aspek Sosial Anak Usia Dini Di Taman KanakKanak Aba Iv Mangli Jember.” INJECT: Interdisciplinary Journal of Communication 2 (1): 99–122.

- Natawisastra, M. 1979. Saratus Paribasa Jeung Bababsaan III. Jakarta: Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

- Nugraha, A. 2019. “Perkembangan Pengetahuan Dan Metode Seni Dan Desain Berbasis Kenusantaraan: Aplikasi Metoda ATUMICS Dalam Pengembangan Kekayaan Seni Dan Desain Nusantara.” In Seminar Nsional Seni Dan Desain: ‘Reinvensi Budaya Visual Nusantara, 25–34. Surabaya: Fine Art and Design Departement,Universitas Negeri Surabaya.

- Rahmansah, and B. Rauf. 2014. “Arsitektur Tradisional Bugis Makassar.” Jurnal Forum Bangunan 12: 56–63.

- Roesmanto, T. 2007. Pemanfaatan Potensi Lokal Dalam Arsitktur Indonesia. Semarang: Fakultas Teknik Universitas Diponegoro.

- Salura, P. 2008. Menelusuri Arsitektur Masyarakat Sunda. Bandung: PT. Cipta Sastra Salura.

- Suharjanto, G. 2014. “Konsep Arsitektur Tradisional Sunda Masa Lalu Dan Masa Kini.” CornTech 5: 505–521.

- Thomas, M., and M. H. Johnson. 2008. “New Advances in Understanding Sensitive Periods in Brain Development.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 17 (1, February): 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00537.x.

- Watson, M. 2016. “Career Exploration and Development in Childhood, Career Exploration and Development in Childhood.” doi:10.4324/9781315683362.

- Yamin, M., and S. J. Sabri. 2013. Panduan Pendidikan Anak Usia Dini. Jakarta: Gaung Persada Press Group.