ABSTRACT

This study employed a three-layer urban fabric analysis method based on Space Syntax techniques to analyze the spatial distribution of the Zhengyi 正一 Namo Daoguans (Nahm-mouh Daoist halls 喃呒道馆) in Guangzhou City during the Republic of China era in quantitative and qualitative ways. We investigated their relationships with physical geographic elements, population numbers, the spatial distribution of local temples, cultural practices, and urban topological spaces, which reflected the complexity and flexibility of their distribution patterns, as well as the marginal, commercial nature of the ritual industries they operate. Meanwhile, compared to other influencing urban factors, the Normalized angular choice (NACH) of urban streets plays a decisive role in the spatial distribution of most Namo Daoguans. The locations of Namo Daoguans were mainly chosen on the streets that people passed through most often, and the travel distance within 750 meters (about 10 minutes walking distance) could nearly encompass all Namo Daoguans. Finally, we summarize the logic and pattern of site selection for the Namo Daoguans in Guangzhou at that time. These new findings deepen the current understanding of related knowledge and provide a basis for future planning and design assessment of related spaces.

1. Introduction

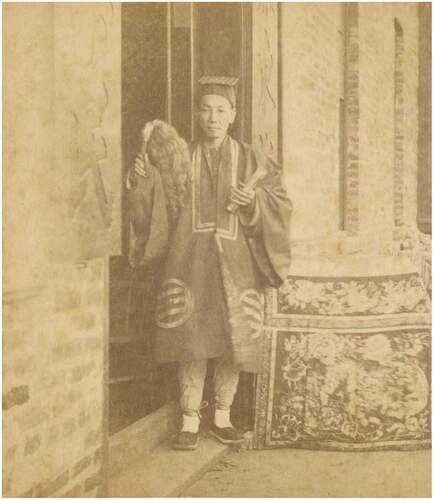

Chinese Taoism is broadly divided into the Quanzhen 全真 school and the Zhengyi 正一 school (Xitai Citation1996), compared to the Quanzhen school, which maintains and perfects the higher level of mysticism in Taoism through its strict precepts and clear regulations, but leads a life separate from the world, the Zhengyi school, on the other hand, supports local temple organizations and mainly serves the wider local population(Tim Citation2007). The Daoist priests who undertake various religious services or rituals in the Zhengyi school are called “at-home Daoist masters (Huoju Daoshi 火居道士)”(Zinan Citation2012), and most of the Zhengyi Huoju Daoshi in modern China come from rural areas (Li Citation2015). They are commonly referred to as “ Nahm-mouh xin san “ in Cantonese, as shown in . When people celebrate marriages, festivals, conduct funerals, ghost avoidance, or treat illness, they would be invited to the Taoist temples or go to people’s residence to perform various religious services or rituals, such as Zanxing 赞星, Tuohe 脱褐, Lidou 礼斗, Wangtu 旺土, Rangzai 禳灾, Dazhai 打斋, and Zuoxunqi 做旬七, etc. (Tim Citation2002), which are closely related to the needs and beliefs of the people. Since the Yuan and Ming dynasties, due to war, local government policies, and the merging of Taoist priests from temples, the number of Huoju Daoshi gradually increased and widely existed in emerging immigrant cities in China such as Shanghai, Hankow, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Fujian, where the spiritual distress caused by the unprecedented social changes made the demand for religion of the common people increase dramatically (Li Citation2015). In Guangdong, the Cantonese proverb “the bells are all thrown away 铃铃喳喳都掉埋” refers to the fact that Huoju Daoshi even threw away the bells used to exorcise ghosts and subdue demons, to describe people’s wretched or miserable appearance (Ouyang Jueya and Bingcai Citation2010), which also proves from one side that the Huoju Daoshi were very common at that time.

Figure 1. A Huoju Daoshi standing in front of his Namo Daoguan in the Guangdong area in the first years of Emperor Guangxu of the Qing Dynasty (Source: by Shuzhen Liu).

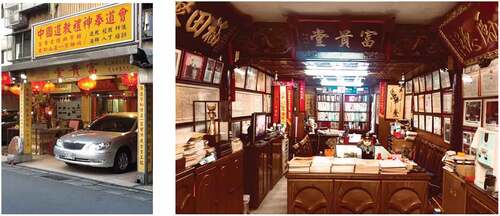

As a combination of religion and business, the character of Namo Daoguan is fundamentally different from that of the perceived Taoist temple. It has a great deal to do with the nature of the profession of the Huoju Daoshi. At that time, all acts with service were socially recognized as a profession, for example, the people needed the Huoju Daoshi to provide ritual services for their weddings and funerals ceremonies, and the Huoju Daoshi were happy to accept invitations in order to solve their livelihood problems (Yingning Citation2000). According to the archives, they called themselves Professional Daoist 业道士 in their file submissions to the government (Li Citation2015). Thus, in order to have a unique location to accept invites to conduct Daoist rituals, the Namo Daoguan was created in Guangzhou as a store front, which inevitably had a strong commercial character. The Daoguan itself is mainly used as a place to receive invitations to perform rituals, and since the Huoju Daoshi do not have a fixed place for religious activities and are mostly invited to set up a new place for rites called Daochang 道场 in other place, most of the rituals are not held in the Daoguan, so the Namo Daoguan are usually ordinary houses owned or rented by the Huoju Daoshi with the signboard of the Daoguan, as shown in . In Guangzhou, there are two types of Namo Daoguans, “Zhengyi Daoguan”正一道馆 and “Praying Daoguan”祈福道馆 (Pan Zhixian Citation2000). The types of rituals they receive correspond to the two categories of Yang and Yin that are closely related to people’s lives in the Taoist tradition. The signboards of the Daoguan are usually their surnames plus the word Daoguan, but without religious symbols, as shown in . Many Namo Daoguans are also engaged in the Daoist business of offering funeral paper and meritorious rituals, so their signboards take their own names, such as Yueshenglou papier-mache offerings 悦生楼纸扎 or Moushantang 务善堂, etc. (Tim Citation2002). In addition, the Huoju Daoshi generally have their own monopoly business territory, generally will not do business in the disciples of others, this monopoly territory is generally called “portal map”(Li Citation2015).

Figure 2. The picture shows the facade as well as the interior of the modern Hong Kong Zhengyi Namo Daoguan Fugui Hall. It inherits the tradition of the Huoju Daoshi in Guangdong Province and still provides ritual services such as praying for blessings and eliminating disasters for the city. (Source: photo by Author).

Figure 3. The plaque of Wu Daoguan in Macau and the portrait of its founder Wu Qingyun (Source: Government Information Bureau of the MSAR).

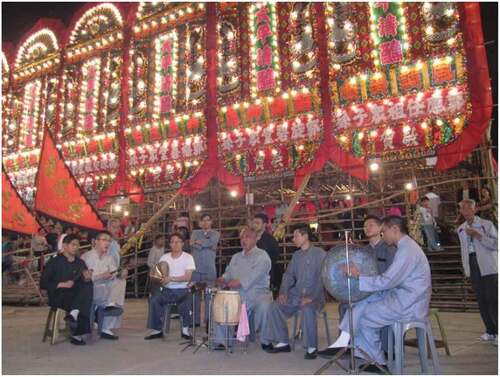

However, in the 25th year of the Republic of China, the Guangzhou Municipal Government considered the commercial Zhengyi and Praying Daoguans as making money from the gods and engaging in superstitious activities, similar to witchcraft, and ordered all police stations to ban them (Tim Citation2014). Since then, the Zhengyi and Praying Daoguans in Guangzhou City have suffered a heavy blow. In 1940, the city of Guangzhou fell to the Japanese, and some of the Taoist priests relocated to Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and other areas in Southeast Asia that were influenced by Chinese culture, such as Singapore, to continue their practice to this day (Li Citation2015; Tim Citation2008; Yuantai Citation2011), as shown in . However, in mainland China, subsequently under the implementation of the relevant religious policies of the People’s Republic of China’s People’s Government, Zhengyi gradually lost its basis of existence due to the lack of a fixed Taoist temple (Pan Zhixian Citation2000). Around 1956, the respective independent and scattered activities of the Zhengyi Taoist temple were closed one after another, and the Zhengyi Huoju Daoshi turned to social employment (Pan Zhixian Citation2000), so that at present only the Quanzhen school of Taoism is spreading in Guangzhou.

Figure 4. Master Liang Zhong led a group of disciples to perform in the open air during the Jiao-festival of the Lotus Land in Pat Heung. (Source: by Shujia Zhou).

As a physical intermediary between the general population and Taoism, the Namo Daoguans interpenetrates with folk culture through daily rituals and responses to folk beliefs, and the ideas of the Tao Te Ching that it helps to disseminate also play a role in edification (Zhongjian Citation2000). Thomas DuBois suggests that Chinese religions can be considered as “spatial” religions in nature, and the rituals are used to reproduce and construct identities within the family and national systems (Du Bois Citation2016). Thus, the spatial distribution of Namo Daoguans, which mixes religion and business, may represent the beliefs and cultural norms of the people living at the time, and has a great historical study value. Furthermore, we believe that, prior to the dramatic changes in the Namo Daoguans’ spatial distribution, the study of its spatial distribution pattern in the urban area of Guangzhou with a population of more than one million not only has significant archaeological significance, but also provides a basis for the planning, design, and evaluation of the Daoguans’ existing space in cities such as Hong Kong and Singapore, which follow the Guangdong tradition, and helps to improve the related functional system of urban services. We also hope to use this article to rediscover their value in contemporary society. In addition, one of the focuses of our research is to make a comparison between the distribution of Daoguans and temples for further discussion in the academic community on the interdependence of the Zhengyi school of Taoism and local temples.

At present, there are studies that focus on the relationship between the state and religion in Guangzhou City, such as the study by Shuhua Pan of the Chinese University of Hong Kong on how the policies of the Kuomintang government changed the role and development of the Zheng Yi Daoist temple and traditional Chinese temples in the 1920s and 1930s (Poon Citation2011). There have also been restorative studies of relevant historical events, such as Guangzhou University scholar Guo Huaqing’s examination of the entire historical events surrounding the two phases of the censorship and banning of Namo Daoguans by Guangzhou city authorities in the 1930s (Huaqing Citation2007). At present, most of the domestic and international studies on the Namo Daoguans are based on qualitative research methods of archival documents and field reports. The studies related to the Namo Daoguans’ spatial distribution mainly focus on qualitative analysis; for example, Lai Chi Tim of the Chinese University of Hong Kong used population numbers and temple distribution to find the spatial distribution pattern of Namo Daoguans in Guangzhou (Tim Citation2014). The author also used the same method to study the spatial distribution of Namo Daoguans in the Qing Dynasty (Tim Citation2016). A similar study on the spatial distribution of religion in urban space was conducted by Song Dejian of the Hakka Research Institute of Jiaying College, who studied the geospatial distribution of Tianhou Temple in Meizhou, eastern Guangdong Province, in relation to social functions (Dejian Citation2013).

In some similar but limited quantitative studies, scholars mostly use digital tools such as GIS and Google Maps to open up research topics on the related effects of urban space on the spatial distribution of religion. For example, Peiyao Zhang conducted an empirical analysis of the distribution and changes of temples in Beijing in the 1920s and 1930s, and explored its relationship with population, industry and trade, guilds, and church patterns of and its interaction with population, industry and trade, guilds, and church patterns (Zhang et al. Citation2016). Ding Hesheng and Zheng Zhenman conducted a comprehensive examination of temples in Putian, Fujian (Dean and Zheng Citation2010). However, the use of qualitative and quantitative methods to study the distribution model of Namo Daoguans, which combines religious space and commercial space, is almost blank. In this article, we use a three-layer urban fabric analysis method based on Space Syntax technology to deeply explore the urban factors that affect the distribution pattern of 231 Namo Daoguans.

2. Objectives and scope

The main questions addressed in this paper are: (1) what messages related to the ritual profession operated by the Huoju Daoshi can be seen in the distribution pattern of the Zhengyi School of Namo Daoguans in the ancient city of Guangzhou during the Republican period? (2) what is the relationship between their distribution and the area where the citizens of Guangzhou lived at that time? (3) from the perspective of geography, cultural practices, economy, or spatial topological factors, the business distribution of the Zhengyi Namo Daoguans in Guangzhou city was more or less influenced by these environmental factors, so which factors could have a decisive influence on its spatial distribution? (4) Can Space Syntax provide additional or different insights into the distribution of Namo Daoguans?

From the middle of the Qing Dynasty until the early years of the Republic of China, historical research on local Huoju Daoshi has been scarce, and most of the research on local Daoism has been obtained from fieldwork investigations by scholars. Fortunately, Lai Chi Tim, an associate professor from the Department of Religion of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, found a copy of the “Survey of Divination, Astrology, Witchcraft, and Geomancy in Guangzhou 广州市卜筮星相巫觋堪舆调查表” published in April of the 18th year of the Republic of China (Citation1929) (Tim Citation2014), in which 680 related practitioners in detail, including the business names and addresses of 274 Zhengyi Daoguans, as well as the names of 297 Daoguans’ Huoju Daoshi. Many of the studies in this paper are based on this archive.

In this study, Section 3 describes the data sources used in this study and briefly reviews the chosen spatial analysis methods and tools. Section 4 will show the results of the study and the analysis of them. The last section is a summary of the results of our research on the spatial distribution patterns of Namo Daoguans in Guangzhou.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Data sources

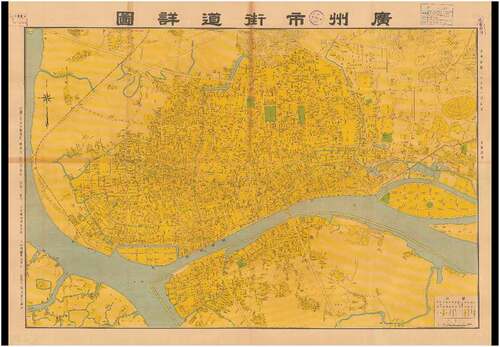

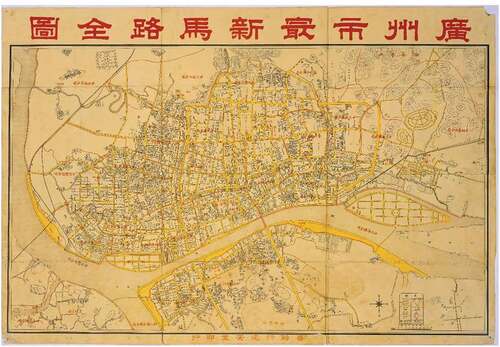

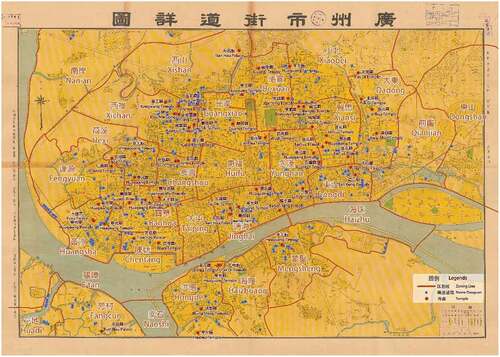

In this study, the spatial alignment and digitization of the map information of the urban area of Guangzhou were carried out with the assistance of several programs, including AutoCAD, Adobe Illustrator, and Adobe Photoshop, using the “Detailed Street Map of Guangzhou 广州市街道详图”. This map was published in January 1948 at the 37th year of ROC and was used as the base map, as shown in Figure A13. Later, the boundaries of the 29 subdistricts of Guangzhou were mapped according to the “Newest Complete Map of Guangzhou City 广州市最新马路全图” printed by the publisher Yuan’an Tang in the 26th year of the ROC (i.e., 1937), as shown in Figure A14. Moreover, the population and the geographical location of the 274 Namo Daoguans in each subdistrict were based on the “Survey of Divination, Astrology, Witchcraft, and Geomancy in Guangzhou 广州市卜筮星相巫觋堪舆调查表” that was issued by the Guangzhou Public Security Bureau in April 1929. Eleven of the addresses cannot be found on the “Detailed Street Map of Guangzhou City”, and 12 of them are in the Xinzhou 新洲 area, which is already outside the scope of the “Detailed Street Map of Guangzhou City”. Therefore, this study finally completes the labeling of 251 Namo Daoguans on the map. As for the 64 temples in Guangzhou, and due to the overwhelming information, this study refers to the research on the location of the related temples by Lai Chi Tim of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Tim Citation2014), combined with the “Survey of Temples in the City 本市庙宇调查” that was conducted by the Guangzhou Social Bureau on 18 March 1938, which is kept by the Guangzhou Municipal Archives Bureau, and also the study refers to the “A Brief Description of Guangzhou’s Suburbs 广州市郊简述” that was published by the South China Working Group in 1949. Three temples were not found on the spatially aligned map of the Guangzhou City Street Map, including the Sanshan King Temple 三山国王庙at No. 1 Lin Tian Gu Dao, the Tian Hou Temple天后庙 at Lian Rang Li, and the Tian Hou Temple at Xin Xi Nanyue 新溪南约, while the Huang Daxian Temple 黄大仙祠 at Hua Di 花地 was not included in the geographical area of the Guangzhou City Street Map. Therefore, the analysis of the spatial distribution of temples in Guangzhou in the 27th year of the ROC performed by this study can only be based on the spatial data of 60 temples. The final collected information is shown in , .

Figure 5. The centerline of a street road in the 37th year of the ROC. It can be seen that the layout of Guangzhou city and its surroundings, the density of the road network in different areas varies, the shape varies, and there is a large difference between areas. (Source: Drawn by author).

Figure 6. Distribution of Namo Daoguans and temples in Guangzhou during ROC period. From the map, we can see the number of Namo Daoguans and temples distributed under different partitions and the distribution relationship. We can also see the relationship between the distribution of Daoguans and waterways. (Source: Drawn by author).

Figure 7. A Framework for the study of spatial distribution of Namo Daoguans (Source: Drawn by author).

3.2. Spatial analysis of the of Namo Daoguans’ spatial distribution using the Space Syntax method

The main method used in this paper is Space Syntax, developed by Bill Hillier and colleagues at University College London (Hillier et al. Citation1976). Space Syntax is a set of techniques for quantitative analysis of urban space based on a mathematical perspective that helps to describe the spatial characteristics of cities. Unlike other spatial analysis techniques, it combines tangible factors (movement and land use) and intangible factors (cognition and behavior) (Yamu, van Nes, and Garau Citation2021). Meanwhile, Space Syntax has proven its validity and reliability in analyzing historical urban space through mathematical means, which has been successfully used across the world, including America (Major Citation2018), Asia (Yu Bo Citation2021), Africa (ADDIN EN.REFLIST Baumanova, M Citation2020), etc., while some scholars have pointed out that it also creates new hermeneutical possibilities (Griffiths Citation2012). It can reveal the inner spatial knowledge and logic of the city, which cannot be measured and understood by other means, including qualitative analysis. For example, Griffiths has used Space Syntax to describe the spatial distribution of cutters and metalworks in Sheffield, England, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Griffiths Citation2005), while Craane used Space Syntax in explaining the distribution of retail functions in medieval Dutch towns and their relationship to those towns (Craane Citation2013). The advantages of the interdisciplinary nature of Space Syntax and its strong relevance to architecture and archaeology match the research objectives of this paper.

The Space Syntax has been developed over a long period, and four mathematical models have been generated: Convex space, Axial line, Isovist fields, and Segment map. In this study, the Segment map is used to analyze the urban space as a linear spatial network structure, and the georeferenced road centerline is used as the network model for generating streets. In the angular segment analysis, the most effective variables for measuring street network accessibility are angle and depth under the radius constraint (Sayed et al. Citation2016). Due to the edge effect of the Space Syntax calculation (Hillier Citation2007) and the limited scope of the map used in this study, the data are insufficient to form an adequate spatial buffer around the survey area, the Space Syntax analysis of the roadhouses located at the map boundaries was not considered in this study. Therefore, there were 231 Namo Daoguans that participated in the Space Syntax analysis. In addition, the depthmapX software defines the search radius as a circular range obtained by taking the center of a road network and the set threshold as the radius, and the Space Syntax calculation results under different search radii are highly variable (Gu Hengyu, Tiyan, and Xiaoling Citation2019). Thus, this study selected a more scientific metric radius for the analysis radius in the software; thus, the boundary effect caused by the partition formed by a set of pre-selected streets can be avoided (Turner Citation2001). In this study, multiple empirical radii were selected for the calculation of Space Syntax. According to the provision of reference reasonable radius (Sayed et al. Citation2016), and considering that pedestrian is the basic condition of the site, the radius mainly used in this study is within 10 minutes of pedestrian traffic (i.e., within 750 m), and the small-scale radius: n (unrestricted radius); 50; 100; 250; 500; 750.

For different variables, depthmapX analysis software can give different weights to the line segment analysis. One of the most valuable weighting methods is segment length weighting. This is mainly because the longer the segment is, the more blocks and entrances are adjacent to it, and thus the higher the probability of social activity occurring on this line segment. This method works better for pedestrian-scale activities (Sayed et al. Citation2016).

Therefore, this study will analyzes the distribution pattern of the Namo Daoguans in Guangzhou through Space Syntax by using depthmapX analysis software and the segment analysis method, selecting the angular analysis mode with a reasonable radius, applying NAIN and NACH algorithms and applying weighting to the line segments.

3.3. Analysis of the Namo Daoguans’ spatial distribution using the three-layer analysis of urban fabric

Space Syntax measures spatial relationships, not positional identity, which means that the form and meaning of construction cannot be explained by space syntactic analysis. Therefore, it is not adequate to use Space Syntax to measure the distribution pattern of Namo Daoguans (Yamu, van Nes, and Garau Citation2021). At the same time, Space Syntax operates independently of urban contexts, so it can be applied to all types of built environments in the past, present, and future, and to all types of built environments on a global scale. Therefore, in the face of such characteristics, Bill Hillier argues that although the theories and methods of Space Syntax make a positive contribution to the historical research, they should not be limited to a single “model” of space analysis, but should be integrated within a multifaceted research framework (Hillier Citation2007). Thus, Bill Hiller argues that at the spatial level, the urban fabric consists of three layers; the topological layer, the cultural layer and the geographical layer, all three of which contribute to the specific urban form of a given town (Hillier Citation2007). This study will build on Bill Hillier’s approach by analyzing the three layers of the urban fabric to examine whether there is an identifiable pattern to the distribution of Namo Daoguans in Guangzhou, and if that’s the case, how it is achieved, how it is explained, and to explore the phenomena it reflects. Furthermore, these layers will be discussed in reverse order, starting with the most specific geographical layer, which will be divided into a physical geographical layer (including watercourses and river distribution factors) and a human geographical layer (including population numbers, number of households, number of merchants, and economic factors), followed by a general cultural layer (including temple distribution and cultural practices factors), and finally a topological layer of general significance, which will be quantitatively analyzed using the means of Space Syntax. It has been argued that this ranking order is more beneficial for researchers to find relevant patterns through the urban structure topology studies (Craane Citation2013). In analyzing the data, regression analysis, as well as buffer zone, was applied in this paper in order to strengthen the scientific nature of the analysis findings. In addition, the results of the analysis will be compared with the results from its previous sections in order to verify whether using Space Syntax can help clarify the spatial distribution patterns of Namo Daoguans while complementing each other’s conditions. Thus, the article research framework is summarized in .

However, the limitations of our chosen method should also be acknowledged. The first is the limitation of relevant historical data. Since the mid-Qing period until the early Republic of China, historical research materials on local fire dowsers are extremely scarce, and conducting the analysis within extremely limited resources is likely to have some impact on the results. In addition, the level of detail of historical maps is limited, which may likewise affect the analysis. In addition to this, some limitations of the spatial syntactic approach should be noted. The planar analysis of Space Syntax does not consider the influence of three-dimensional geography on its spatial distribution. In the historical maps of this study, the influence of waterways is difficult to weight appropriately. Although centerlines can be used to cover the river space, it is still an open question how to distinguish the different relationships between river routes and ordinary street centerlines.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Geographical layer: physical geographical layer

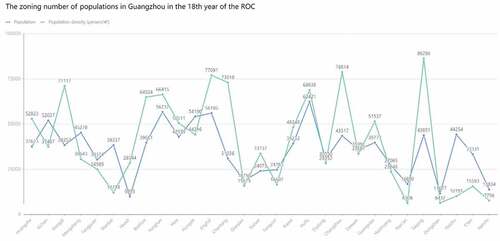

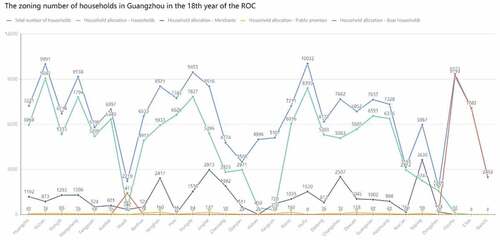

The most important geographical feature of Guangzhou is its location at the confluence of the Xijiang, Beijiang and Dongjiang rivers, with a dense network of water. Therefore, water use and management play an important role in the urban structure of Guangzhou. Haizhu 海珠, E’tan 鹅潭, and Nanshi 南石 districts are the most special regions among the 29 regions of Guangzhou, because they are mainly zoned in the area surrounded by waterways on the surface of the Pearl River. Therefore, these districts are dominated by boat-dwelling households (Danmin 疍民). According to the data shown in , the number of households’ distribution in these three districts, where boat households are more prominent, accounts for 98.5%, 99.97%, and 99.9% of the total number of households, for Haizhu, E’tan, and Nanshi, respectively. This explains why the number of Namo Daoguans in these regions is zero. Certainly, this does not mean that the people who reside near water do not need to hire Huoju Daoshi to perform auspicious celebrations or rites for the dead in their boats. Wu Ruilin mentioned that the people of Shanan boat-dwellers believe in Hung Shing Tai Wong 洪圣大王, Wah Kwong Tai Tai 华光大帝 and Tin Hau Yuen Kwan 天后元君; they all put Tin Kuan 天官 at the bow of their boats and Dragon God 龙神 at the stern of their boats, and when there is a divine festival, they usually hire a Huoju Daoshi to perform related rituals from morning to night to prevent disasters and bad luck when there is a religious festival (Ruilin Citation2010). Lai Chi Tim, a scholar from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, also discussed the great demand for the Huoju Daoshi to provide Daoism services in the Haizhu district, which led to an increase in the number of Namo Daoguans in the Dongdi 东堤 district (Tim Citation2014). Therefore, the same is true for the other districts, which explains why the number of Namo Daoguans in the overall layout of the two shore areas of these regions is distributed more than that of the central district. In addition, the data of “household distribution – boat households” shown in for Huadi 花地, are also prominent with boat households accounting for 63.9% of the total number of households. The geographical condition of half waterway and half land makes the boat-dwelling people, as well as the land residents, craving to the service of the Huoju Daoshi, which explains why Huadi is surprisingly ranked seventh in the number of the Namo Daoguans, despite having the smallest total population of all the regions. However, the distribution of Namo Daoguans in the rest of the regions is not much associated with the river, and shows that most of the Namo Daoguans do not like to be located near the water, the reasons for which need further research and exploration.

4.2. Geographical layer: human geographic layer

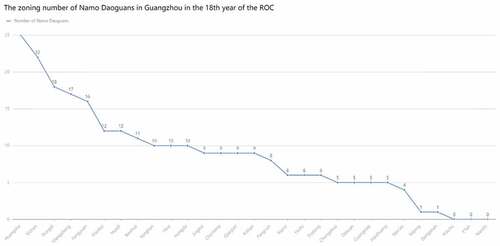

It has been a long-standing tradition for the Zhengyi Huoju Daoshi to live in partnership with the secular world. Therefore, to operate Daoguans and to undertake Daoist rituals, the auspicious and funeral ritual services provided by Zhengyi Daoguans are not only integrated with the belief practices of the local population; but also, it is reasonable to believe that their distribution in a city should be somewhat related to the number of people, households, and businesses in that area. As confirmed by the population zoning table data, shown in , when removing the areas influenced by the geographical factors, the water-dominated Haizhu, E’tan, and Nanshi districts, the half-land, half-water Huadi district, and the areas near the waterfront such as Dongdi and Fengyuan 逢源, the remaining areas, basically follow a linear pattern; as the number of population purposes decreases, the corresponding number of Namo Daogguan decreases as well, with a few exceptions for some special cases.

The five districts of Huangsha 黄沙, Xichan 西禅, Dongdi, Mengsheng 蒙圣, and Fengyuan are the five sub-districts with the highest number of Namo Daoguans operating in Guangzhou, with a total of 98, accounting for 36% of the 274 Namo Daoguans and 20% of the total population, the reason why the numerical percentages are not very close is because there are a few exceptions. The Huangsha district has the largest number of Daoguans, but is only the 16th most populous in the city (population 37,623), while the Dexuan 德宣 district, which is 17th in population, has only five Namo Daoguans, which some scholars speculate is closely related to the fact that Huangsha district provided various rituals services for the many fishing boats that go to sea (Tim Citation2014).

In addition, the five areas of Taiping 太平, Jinghai 靖海, Yonghan 永汉, Hongde 洪德, and Huifu 惠福 have a large population compared to other areas, accounting for 26.2% of the population, yet the number of Namo Daoguans is only 13%. According to Chen Daiguang’s scholarly description, since the Ming and Qing dynasties, the four areas of Taiping, Jinghai, Yonghan, and Dongdi, which belong to the so-called new urban areas, have become the central commercial areas along the river in the south of the city, with numerous docks and merchant ships nearby, the areas were prosperous and densely populated (Daiguang Citation1996). The number of Namo Daoguans in the Dongdi area has been discussed previously and is related to the demand of the boat-dwelling people in the nearby Haizhu district, while Taiping, Jinghai, and Yonghan districts all have a very prominent number of merchants as shown in , with Taiping district accounting for the largest number of merchants among the 29 sub-districts in Guangzhou, to the extent that there is only one Namo Daoguans. This indicates that there should not be much need for the Daoist ritual trades provided by the Namo Daoguans in these commercial areas. Moreover, for business purposes, and due to the small number of residents, the business of the Namo Daoguans to undertake the Daoist services would not be very good. The Hongde area is located on the south bank of the Pearl River and has a population of 54,190, ranking fourth, yet there are only 10 Namo Daoguans, which is nearly half as many as the 17 Daoguans in Meng Sheng, which also has 45,278 people on the south bank, and according to the population zoning table, the number of merchants is similarly more prominent, thus I presume it is also related to the commercial economy. Therefore, based on previous discussion, a conclusion can be drawn that, in general, the distribution of Namo Daoguans is positively correlated with the number of people and negatively correlated with the number of merchants in the area.

However, Huifu district has the largest population of 62,421 people in the entire subdistrict, and although the number of merchants is also prominent, there are only six Namo Daoguans distributed, which is still not explained by the number of population and merchants alone, as will be discussed in the next section of this study. In addition, the Excel data analysis tool was used in this study to perform regression analysis on the number of population and the number of Namo Daoguans in the corresponding subdistricts. The x–value was set as the independent variable for the number of populations in the subdistrict, and the y-value was set as the dependent variable for the number of Namo Daoguans in the subdistrict. Considering the interference of special areas on the correlation, the second measurement removes Haizhu, E’tan, Nanshi, Huadi, Huangsha, Dongdi, Taiping, Jinghai, Yonghan, Hongde, and Huifu districts, and the resulting value of the correlation coefficient (Multiple R) is 0.5750. By definition, the Multiple R values range from −1 to 1. The closer the absolute value is to 1, the stronger the correlation is, and the closer the value to 0, the weaker the correlation is (Faraway Citation2002). This indicates that 57.5% of the Namo Daoguans distribution can be explained by the population size.

At the same time, according to the observation of , and based on the regional orientation, the 29 districts divided in 1933 can be further distinguished into four major areas, including the old city center, Xiguan 西关, Dongshan 东山, and Henan 河南(Committee, Citation1929). According to the Guangzhou Yearbook published in 1929, the old city center was divided into seven subdistricts, including Dexuan 德宣, Guangxiao 光孝, Huifu, Yonghan永汉, Xiansi贤思, Jinghai and Dongdi, and had a total population of 328,611, which represent around 30% of the entire Guangzhou city, and had a total of 52,021 households, which represent around 29.3% of the entire Guangzhou city. In the Xiguan District, there were eight districts, including Xishan 西山, Xichan 西禅, Hexi 荷溪, Changshou 长寿, Fengyuan 逢源, Baohua 宝华, Chentang 陈塘 and Huangsha, and the total population of these eight districts was 298,011, which represents around 28.3% of the entire Guangzhou city, while the total number of households was 54,719, which represent around 28.5% of the entire Guangzhou city (Committee, Citation1929). According to the “Survey of Divination, Astrology, Witchcraft, and Geomancy in Guangzhou” in the 18th year of the ROC, the distribution of the 274 Namo Daoguans of Guangzhou was 59 Namo Daoguans in the seven subdistricts of the old city but 107 in the eight districts of Xiguan, with similar percentages of population in the two regions. Thus, the difference in Daoguans was nearly half. To explain this distribution trend, it is necessary to analyze another spatial attribute of the 274 Namo Daoguans operating in Guangzhou city, starting from factors other than the population, such as the number of temples in each district.

4.3. Cultural layer

The cultural layer is one of the three layers that make up the urban fabric of the town. For the Huifu district mentioned above, and according to historical records, Huifu district was the area where the soldiers of the eight Manchurian banners were stationed and where their families lived. The district was called the “banner territory 旗境”, and was the center of political and military activities in the old Guangzhou city (Shan Citation1992). From this information, it is clear that the Huifu district has the characteristics of Manchu history and culture, and there is naturally a great estrangement from the ritual traditions of the Daoist Zhengyi school, and it is also obvious that there is not much demand for the Namo Daoguans would be in this district. Thus, cultural aspects can also have a significant impact on the distribution of Namo Daoguans. The same is true for the religious culture. According to the field research led by Lai Chi-Tim, many Huoju Daoshi would often undertake the rituals for the celebration of sacred festivals held at many local temples, and the Daoist rituals associated with temple festivals are actually very extensive and diverse(Tim Citation2009). In addition, the Huoju Daoshi were not only associated with the rites of the temple festivals, but whenever the local temples were rebuilt and completed, the earth gods were installed and the statues were blessed, they would be invited by the temple priests to go to the temple and perform the Daoist rites in order to reward the gods(Tim Citation2014). Thus, we can assume a close relationship between the Huoju Daoshi and the temple’s religious activities, and the distribution of the Namo Daoguans where they performed rites may be related to the distribution of the local temples.

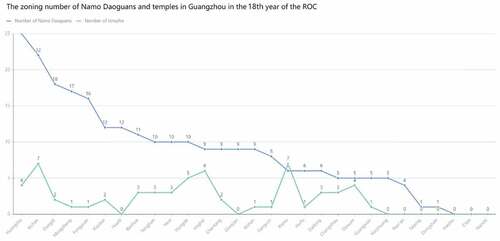

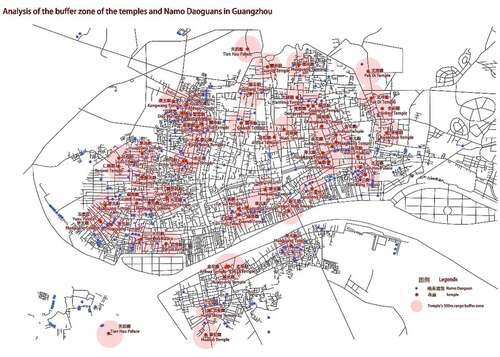

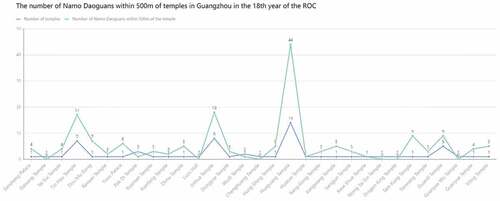

According to the data shown in , the Xichan district area has seven temples, which is one of the highest number of temples among all subdistricts and also has the district also has the second-highest number of Namo Daoguans in the entire subdistrict. However, it is hard to explain why the Xiansi district also has the highest number of temples (i.e., seven) but only six Namo Daoguans. The line graph of the number of Namo Daoguans and the number of temples shown in also has a poor fit. A regression analysis was also performed on the data shown in , with the independent variable x set to the number of temples and the dependent variable y set to the number of Namo Daoguans, and the final result was a Multiple R-value of 0.4328. This would indicate that 43.3% of the distribution of Namo Daoguans can be explained by the number of temples. However, it is obvious that the distribution of some of the Daoguans shown in is based on the distribution of temples. Therefore, the ArcGIS software, one of the more important spatial analysis functions of GIS, was used to construct a method to measure the distance in the two-dimensional Cartesian plane using the Euclidean buffer (buffer zone analysis). It was used with an appropriate parameter setting of 500 m to investigate the distribution of Namo Daoguans and temples more deeply, as shown in . Also, in order to clarify whether the distribution of Namo Daoguans in the buffer zone is related to their corresponding temples, and also to exclude the situation that Namo Daoguans “happen” to be distributed near the temples, a line graph has been made based on the number of Namo Daoguans within 500 m of various types of temples and the number of corresponding temples. The Namo Daoguans located in two or more temples simultaneously are processed superimposed, as shown in . To understand the distribution pattern of the data, a regression analysis was performed with the x–value independent variable set to the number of temples in each category and the y-value dependent variable set to the number of Namo Daoguans within 500 m of the temple corresponding to the partition. The value of Multiple R is 0.9296, meaning that 93.0% of the distribution of Namo Daoguans located within 500 m of a temple has an extremely strong positive correlation with the number of temples. In addition, a total of 115 Namo Daoguans located within 500 m of temples were evident according to , which is only 45.81% of the total 251 marked points on the figure, which in turn explains why the overall distribution of Namo Daoguans in the previous exploration yielded a low correlation coefficient (Multiple R) with the distribution of temples. From this, it can be concluded that although there are partial Namo Daoguans that do correlate strongly with the distribution of temples, the overall correlation is poor, so there must be other factors that “guide” the distribution of Namo Daoguans.

Figure 11. The zoning number of Namo Daoguans and temples in Guangzhou in the 18th year of the ROC (Source: Drawn by author).

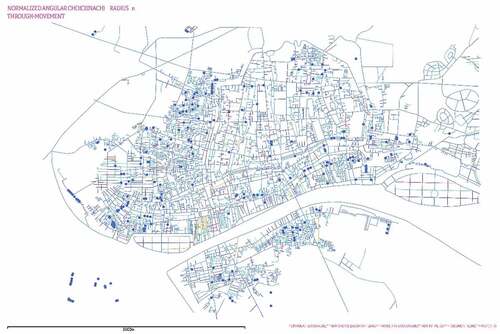

4.4. Topological layer and Namo Daoguans site selection logic

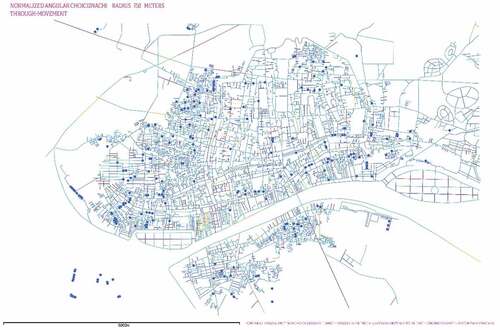

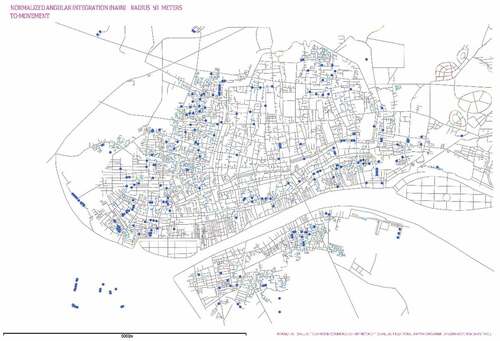

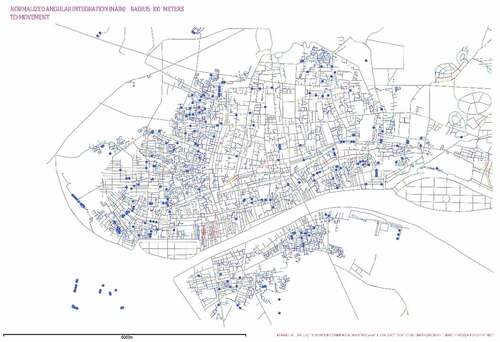

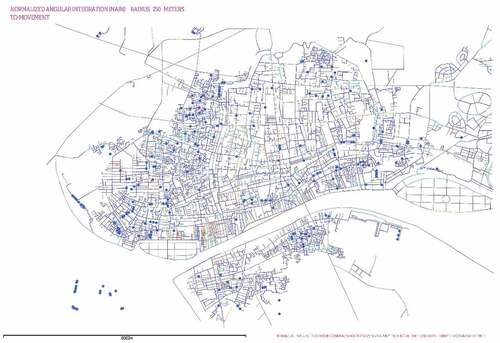

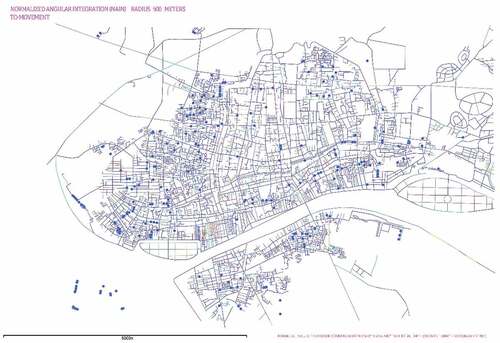

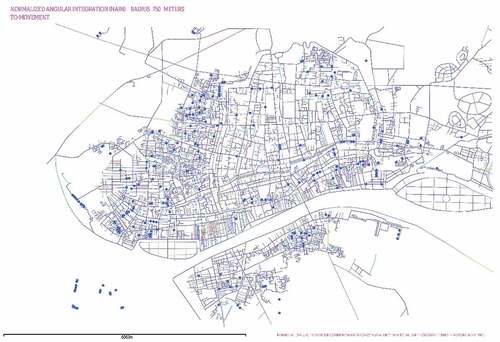

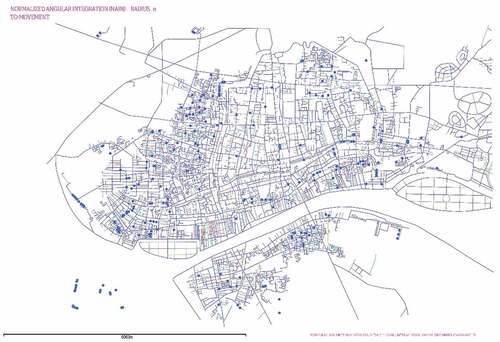

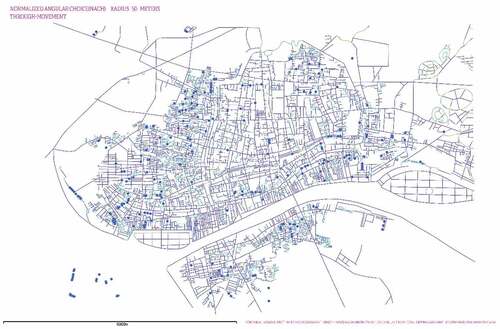

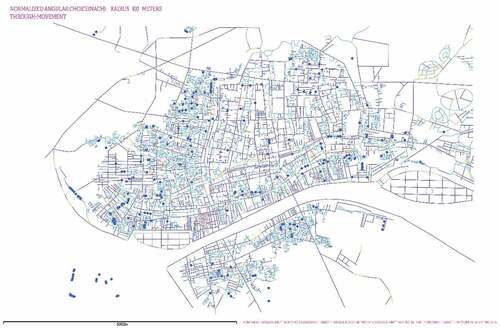

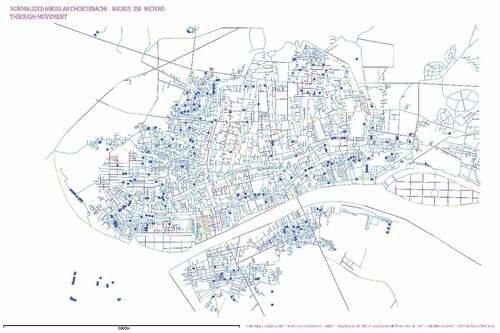

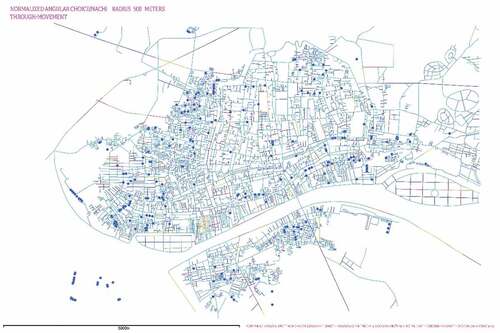

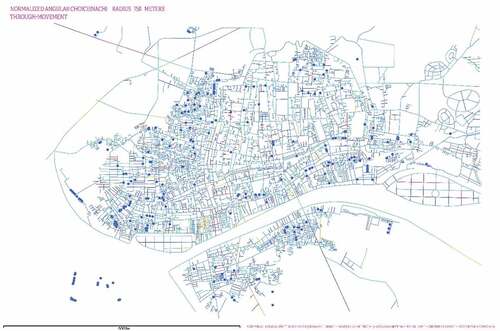

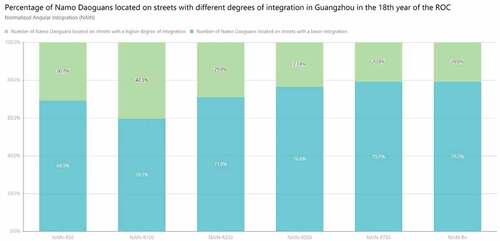

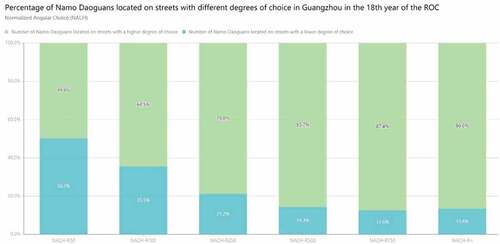

The last layer that needs to be discussed is the topological layer, which mainly uses the segment analysis method, with a reasonable radius: Rn (unrestricted radius); R50; R100; R250; R500; R750. It also applies the NAIN and NACH algorithms to analyze the urban area of Guangzhou in the 37th year of the ROC, after which the use Adobe Illustrator was used to overly the Namo Daoguans distribution map, temple distribution map, and subdistrict distribution map to analyze the distribution pattern of Namo Daoguans with the Space Syntax, as detailed in Figure A1 through Figure A12. The NAIN shows which street is the most likely destination “To-Movement” when one walks through from any starting point. The most likely destination – and the most complete destination – is the red line, while the least likely destinations – and the most segregated destinations – are the dark blue and gray segments, while the orange, yellow, grass-green, and bright blue segments are in the middle. On the other hand, the NACH shows which street segment people are most likely to pass through when traveling from any origin to any destination, reflecting the potential of that street segment as a Through-Movement. Red segments are the most frequently chosen routes, while dark blue segments are the least frequently chosen routes, with orange, yellow, grass-green, and bright blue segments also in the middle. The number of Namo Daoguans distributed on the dark blue line segment (with lower values) was counted under different radii values, and the results were as follows: for the NAIN analysis, R50 (160), R100 (138), R250 (164), R500 (177), R750 (183), Rn (183); and for the NACH analysis, R50 (116), R100 (82), R250 (49), R500 (33), R750 (29), Rn (31). The number of Daoguans values was divided by the total number of Namo Daoguans markers on the (i.e.,231) after removing the markers at the edges to better see the correlation between Namo Daoguans and integration and choice at different radii, and organized into percentage histograms, The results are shown in

Figure 14. Percentage of Namo Daoguans located on streets with different degrees of integration in Guangzhou in the 18th year of the ROC (Source: Drawn by author).

Figure 15. Percentage of Namo Daoguans located on streets with different degrees of choice in Guangzhou in the 18th year of the ROC (Source: Drawn by author).

The NAIN histogram shown in shows that as the radius R increases, the number of Daoguans with higher integration increases as well, showing a positive correlation. However, at the critical value of R100, the number of Daoguans with higher integration decreases as the radius R increases, showing a negative correlation. In addition, even though the analysis radius is 100 m, the number of Daoguans located with higher integration is the highest among all radii (i.e., 113), yet its percentage is only 40.3%, which means that of all the destination streets that people are most likely to reach within 100 m, only 40.3% of Daoguans are located on such streets. In addition, to show more clearly where the city center, which is the area with the highest integration in the entire city, is located, and to make it comparable to the distribution of Namo Daoguans, the formula Angular Integration = NC^1.2/TD for global integration with radius n was used. This algorithm can better show the location of the city center, although its data of NC are overly strengthened compared to the NAIN, but for the study of the overall layout relationship, it does not need such high accuracy, and the results are shown in . In the 37th year of the ROC, the city center area is still located within the old city center (i.e., the seven subdistricts of Dexuan, Guangxiao, Huifu, Yonghan, Xiansi, Jinghai and Dongdi). However, as already explored in the human geographic layer, compared to the eight districts of Xiguan with 107 Namo Daoguans, there are only 59 in the old city center. Therefore, for the analysis of integration, it can be safely concluded that the distribution of Namo Daoguans has a negative correlation trend with both local integration and global integration in general. In fact, it is not difficult to understand that places with a high degree of urban integration generally have a strong ability to attract coming traffic and are more likely to gather people: thus, in general, such areas are also more commercially developed, and as mentioned above, there is no much need for the Daoist ritual industry provided by the Namo Daoguans in such commercial areas.

As for the NACH histogram analysis shown in , it is clear that as the radius R increases, the number of Daoguans located in streets with higher choice increases as well, showing a positive correlation. However, at the critical value of R750, as the radius R increases, the number of Daoguans located in streets with higher choice decreases instead, showing a negative correlation. When the analysis radius is 750 m, there are 202 Daoguans, which accounts for 87.4%. In other words, a total of 87.4% of the Daoguans are located in the streets that people are most likely to pass through or use as route choices within 750 m, as shown in the . The distribution of the remaining 29 Daoguans is likely to be related to the distribution of temples; thus, the remaining Daoguans’ distribution locations were compared with , and the results are shown in . In , it is evident that only 10 of the 29 Daoguans are not within the 500 m buffer zone of temples, accounting for 34.5%, which indirectly proves that the Namo Daoguans explored in the previous section are indeed related to the distribution of temples. By removing these 10 Daoguans data, within the total number of 231 Daoguans, the ratio of the number of Daoguans located on streets with high NACH is 91.4%. By also comparing the ratios of the number of population, the number of merchants, and the spatial distribution pattern of temples and Namo Daoguans explored in the previous section, it can be safely concluded that the spatial distribution of Namo Daoguans in Guangzhou in the 37th year of the ROC was mainly related to the degree of street NACH, and their placement locations were mainly chosen on the streets that people passed through frequently.

Table 1. Results of comparing the location of the remaining Namo Daoguans with the buffer zone analysis map (Source: Drawn by author).

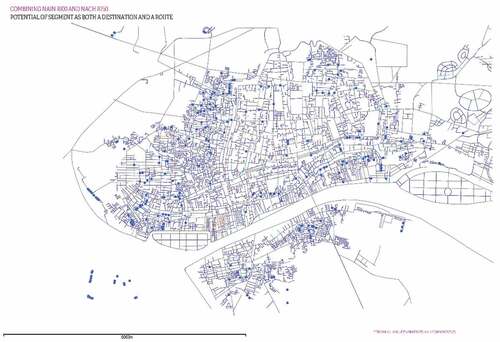

Subsequently, the NAIN and NACH were combined to form a composite variable for the analysis, i.e., the streets that fit both high integration and high choice were analyzed and compared to the distribution of the Namo Daoguans. The depthmapX software was used to select the radius with the best fit to the actual Daoguans’ distribution (i.e., the NAIN at R100 and the NACH at R750), and set the algorithm formula in the software as the value (“NAIN R100”) *value (“NACH R750”) to get the result, as shown in . After counting, there are only 26 Namo Daoguans located above the streets that meet the high Integration and high Choice, which accounts for only 11.26%, and with 12 of those Namo Daoguans are being located within 500 m of the nearby temples. Therefore, this proves that the distribution of Namo Daoguans is less related to the degree of integration and mainly related to the degree of street choice.

To answer the question why the Huoju Daoshi like to open their Daoguans in areas with low Integration but with high Choice, it is important to consider that the Huoju Daoshi themselves are not monks, and the Daoguans are just the ordinary houses they own or rent with a Daoguan signboard, as shown in . Therefore, it is too costly and not cost-effective to choose a commercial or central area with high integration and especially high prices in terms of location. In addition, the Daoguans’ main service population is the residents, a high number of commercial tenants means a low number of residents, it is hard to perform business, and their Daoist rituals will not have much need in the commercial area. The reason why the Daoguans do not choose remote areas or areas that are out of the city center, but rather choose to be in the more traveled streets, is that their activities are mostly for livelihood purposes. Moreover, although they are related to religious rituals, they are also strongly commercial in nature, so they choose the streets that people are most likely to pass through to maximize business. In addition, 750 m is about a ten-minute walking distance, which is generally close to the reasonable limit of the walking distance (Wang Ning Citation2015), and any further distance would require the use of some means of transport. Certainly, the commercial nature of the Namo Daoguans is close to that of a witch for the commercial profit, and it is no wonder that the local government of Guangdong at that time regarded these people as wizards rather than religious people, and thus outlawed these non-productive Namo Daoguans (Huaqing Citation2007). At the same time, we can tell from the Namo Daoguans’ site selection features that there was some marginality in the distribution pattern of the Namo Daoguans. Despite the fact that activities of Huoju Daoshi were closely related to the people, the Republican government’s oppressive attitude toward them prevented them from obtaining a better socio-political, economic, and cultural status through normal channels, resulting in the marginal nature of their work and the distribution of their residence, which also exemplifies the strong characteristics of the era in which the distribution patterns of Namo Daoguans were investigated.

By applying the Space Syntax analysis method, this study was able to uncover the spatial elements hidden in the topological space of the historic city streets that influenced the layout of the Namo Daoguans, which is contributing to the existing field of research in a way that has never been achieved before. Moreover, the results of the analysis derived through Space Syntax technique coincide with the more qualitative and interpretive findings of the previous research studies, which in turn can confirm the scientific nature of its analysis. Thus, Space Syntax is also verified once again in this paper for its ability to provide scientific additional or different insights into the distribution of the historic space.

Finally, we summarize the logic and pattern of site selection for the Namo Daoguans in Guangzhou during the Republican period by synthesizing the three layers of urban fabric analysis, as shown in . It can be found that the distribution of Namo Daoguans did not only exist in a single pattern. Due to the influence of the geographical environment, different religious and cultural regions, and different service recipients, the distribution of Namo Daoguans also changed and were highly flexible, which is related to the identity of the Zhengyi Huoju Daoshi as a “household-type religious service provider”. The characteristics of Huoju Daoshi who are free from the system and provide corresponding ritual services and related interpretation systems for different individuals, families and communities determine the complex nature of the distribution pattern of the Namo Daoguans. However, it is also clear that the Namo Daoguans provided a platform for the Huoju Daoshi to support the religious life of the local community and the organization of temples, and to provide rituals services to the people, which constituted an important part of the rich religious and spiritual life of the grassroots people.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we break through the limitations of a single analysis of Space Syntax in terms of research tools and adopt a more integrated approach between it and historical disciplines, using the three-level urban fabric analysis proposed by Bill Hillier to make a more in-depth comparative analysis of the spatial distribution patterns of 231 commercial Namo Daoguans scattered in the urban areas of Guangzhou during the Republican period. We found that geographic elements have a decisive influence on three of the districts in Guangzhou city: Haizhu, E’tan and Nanshi districts (mainly zoned on the Pearl River) and Huadi district, (within half land and half waterway). However, the Namo Daoguans distribution in the rest of the districts is not much associated with the river. Secondly, the study of the human geography layer reveals that the number of its distribution in the sub-district is positively correlated with the number of population, households and businesses in the sub-district, except for a few exceptions, yet it still does not play a decisive role. Subsequently, the cultural layer was explored in this study, and certain Namo Daoguans’ distribution was found to have a strong correlation with the temple distribution; however, the overall correlation is still relatively low. Finally, for the topological layer, Space Syntax techniques was used in the analysis. On the one hand, and in terms of local and global integration, it was found that they are, in general, negatively correlated with the distribution of Namo Daoguans. That is, there are fewer Namo Daoguans in street areas that are more likely to attract coming traffic, more likely to gather people and more commercially developed. On the other hand, however, it was found that the spatial distribution of Namo Daoguans was determined by the degree of choice of urban streets. In other words, they are located mainly in the streets that people pass by most often, and within 750 m, or about 10 minutes of walking distance, which can almost cover all the Namo Daoguans.

This study contributes to the existing literature in a number of ways. Using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods, we have integrated a three-level urban fabric analysis to derive the site generation logic and influencing factors for the selection of Namo Daoguans in Guangzhou, expanding the understanding of the Zhengyi school of Huoju Daoshi and their Daoguans. Furthermore, the research in this paper also confirms the grassroots nature of Huoju Daoshi from the side, and the study of the influence of multiple urban elements on the distribution of Namo Daoguans provides a new perspective for understanding the Zhengyi school of Huoju Daoshi. At the same time, we compare the relationship between the distribution of temples and Namo Daoguans, which provides new clues for the exploration of the interdependence between the Zhengyi school of Taoism and local temples in the academy.

Our study advances the understanding of the relationship between Namo Daoguans and Guangzhou towns. We found that the distribution of the combined commercial and religious Namo Daoguans, in addition to their own marginality and strong commerciality as reflected in the study results, their distribution patterns vary according to geography, cultural region, and the people they serve, and are highly flexible, closely related to the nature of the ritual profession of the Huoju Daoshi. Therefore, urban planners should not just think of Namo Daoguans as commercial stores or religious spaces, but also consider their category, the people they serve, and the characteristics of the way they operate.

In addition, this paper also brings new knowledge about the determinants affecting Namo Daoguans. Although there are a small number of Namo Daoguans that are more closely associated with regional divisions and temples due to their own business purposes and the different clients they serve, our study found that the distribution of most Namo Daoguans is in fact primarily influenced by topological spatial relationships, being located far from urban centers and on the streets that people pass through most often. Therefore, future research and policy should consider how to integrate such spaces into the broader field of urban planning and design, and more research is needed to further investigate the ecology of the ritual profession of Huoju Daoshi. At the same time, there is a need for more research as the planning and development patterns of the cities in which Namo Daoguans exist vary around the world.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Associate Professor Duan Wei for his strong support for this research work. At the same time, I would like to thank the three reviewers for their insightful suggestions and careful reading of the manuscript. Finally, I would like to thank Li Wang Wang for her contributions for this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Haoxian Cai

Cai Haoxian is currently studying for a master's degree in the Department of Architecture at Beijing Forestry University. His research interests include urban public space, Space Syntax, spatial composition and evolution, and rural architecture. Dr. Duan Wei is an associate professor of Landscape Architecture at the School of Landscape Architecture at Beijing Forestry University where he teaches architecture history and theory courses.

Wei Duan

Cai Haoxian is currently studying for a master's degree in the Department of Architecture at Beijing Forestry University. His research interests include urban public space, Space Syntax, spatial composition and evolution, and rural architecture. Dr. Duan Wei is an associate professor of Landscape Architecture at the School of Landscape Architecture at Beijing Forestry University where he teaches architecture history and theory courses.

References

- ADDIN EN.REFLIST Baumanova, M. 2020. “Sensory Synaesthesia: Combined Analyses Based on Space Syntax in African Urban Contexts.” African Archaeological Review 37 (1): 125–141. doi:10.1007/s10437-020-09368-9.

- Committee, G. Y. C. 1929. Guangzhou Yearbook. Guangzhou, China: Guangzhou Yearbook Compilation Committee.

- Craane, M. (2013). “Spatial Patterns: The late-medieval and early-modern Economy of the Bailiwick of’s-Hertogenbosch from an Interregional, Regional and Local Spatial Perspective.”

- Daiguang, C. 1996. Guangzhou chengshi fazhan shi 广州城市发展史 [History of Guangzhou City Development]. Guangzhou, China: Jinan University Press.

- Dean, K., and Z. Zheng. 2010. Ritual Alliances of the Putian Plain. Vol. 4. Guangzhou, China: Brill.

- Dejian, S. 2013. “The Geospatial Distribution and Social Functions of Temples-A Study of Religious Geography on Devotion to the Queen of Heaven in Meizhou County, Guangdong Province.” Journal of Jiangxi Normal University(Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 46 (4): 127–132.

- Du Bois, T. D. 2016. “Local Religion and Festivals Jan Kiely, Vincent Goossaert, and John Lagerwey.” Modern Chinese Religion II: 1850-2015 (2 Vols.), 367–400. Brill.

- Faraway, J. J. 2002. “Practical Regression and Anova Using R.” 168 (University of Bath Bath) http://cran.r-project.org/doc/contrib/Faraway-PRA.pdf.

- Griffiths, S. 2005. Historical Space and the Practice Of” Spatial History”: The spatio-functional Transformation of Sheffield 1770-1850, 656–667. University College London, UK.

- Griffiths, S. (2012). “The Use of Space Syntax in Historical Research: Current Practice and Future Possibilities.” Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Eighth International Space Syntax Symposium Santiago de Chile .

- Gu Hengyu, H. D., S. Tiyan, and Q. Xiaoling. 2019. “Space Syntax Model Verification and Application in Urban Design with Multi-source Data.” Planners 5: 67–73.

- Hillier, B. 2007. Space Is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture. London, UK: Space Syntax.

- Hillier, B., A. Leaman, P. Stansall, and M. Bedford. 1976. “Space Syntax.” Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design 3 (2): 147–185. doi:10.1068/b030147.

- Huaqing, G. 2007. “Minguo shiqi Guangdong de daojiao zhengce lunxi- yi guangdong difang zhengfu chajin Guangzhou ”namo daoguan” shijian wei zhongxin de kaocha 民国时期广东的道教政策论析——以广东地方政府查禁广州”喃呒道馆”事件为中心的考察 [An Analysis of Taoist Policies in Guangdong during the Republican Period: An Examination Focusing on the Incident of the Guangdong Local Government’s Banning of the ”Namo Daoguans” in Guangzhou].” Studies in World Religions (3): 14.

- Li, M. 2015. “Min guo cheng shi zheng yi huo ju dao shi qun ti yan jiu - yi han kou wei zhong xin 民国城市正一火居道士群体研究——以汉口为中心 [A Study of the Zhengyi Huoju Daoist Community in the Republican City - Centered on Hankow].” Studies in World Religions (1): 87–96.

- Major, M. D. 2018. The Syntax of City Space: American Urban Grids. New York, America: Routledge.

- Ouyang Jueya, Z. W., and R. Bingcai. 2010. Guangzhou hua suyu cidian 广州话俗语词典 [Guangzhou colloquial dictionary]. Guangzhou, China: Guangdong People’s Publishing House.

- Pan Zhixian, Y. H. 2000. “Guangzhou daojiao xianji gouchen 广州道教仙迹钩沉 [The Daoist Immortal Trail in Guangzhou].” China Taoism 3. doi:10.19420/j.cnki.10069593.2000.03.008.

- Poon, S.-W. 2011. Negotiating Religion in Modern China: State and Common People in Guangzhou, 1900-1937. Guangzhou, China: Chinese University Press.

- Ruilin, W. (2010). “Minguo Guangzhou de danmin, renlichefu he cunluo: Wu Ruilin shehuixue diaocha baogao ji 民国广州的疍民, 人力车夫和村落: 伍锐麟社会学调查报告集 [Dwelling People.” Rickshaw Drivers and Villages in Guangzhou, Republic of China: A Collection of Sociological Investigation Reports by Rui-Lin Wu]: Guangdong People’s Publishing House.

- Sayed, K. A., A. Turner, B. Hillier, S. Iida, A. Penn, S. Gao, and T. Yang. 2016. “Segment Analysis & Advanced Axial and Segment Analysis: Chapter 5 & 6 of Space Syntax Methodology: A Teaching Companion.” Urban Design 32–55.

- Shan, C. 1992. Zhu yue baqi zhi 驻粤八旗志 [The Eight Banners in Guangdong]. Guangzhou, China: Liaoning University Publishing House.

- Tim, L. C. 2002. “History of ”Nahm-mouh Daoist Halls” in Early Republican Canton.” Bulletin of the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica(37) 1–40. doi:10.6353/BIMHAS.200206.0001.

- Tim, L. C. 2007. Guangdong Local Daoism: Daoist Temple, Master, and Rutual. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

- Tim, L. C. (2008). “Hong Kong daojiao zhaijiao zhong de ”jiyou” yishi yu xiandai shehui de yiyi guanxi 香港道教齋醮中的” 祭幽” 儀式與現代社會的意義關係 [The meaningful relationship between the rituals of the ”sacrificial priests” in the Hong Kong Taoist rituals and modern society].” Paper presented at the 2002 nian daojiao jiaoyi yu xian dai shehui guoji xueshu yantao hui 2002 年道教教义与现代社会国际学术研讨会 [2002 International Symposium on Taoist Teachings and Modern Society].

- Tim, L. C., Ed. 2009. Aomen Wuqingyun Daoyuan de lishi bianqian: Shijiu shiji yilai Aomen Zhengyipai huoju daoshi yanjiu 澳門吳慶雲道院的歷史變遷:十九世紀以來澳門正一派火居道士研究 [A study of the Daoist alter of Wuqingyun in Macau: History of Zhengyi Daoists in Macau since the nineteenth century]. Hong Kong: Hong Kong.

- Tim, L. C. 2014. “A Spatial Analysis of the Distribution of Popular Zhengyi Daoist Halls in Early Republican Guangzhou: Temples, Population and Daoist Ritual.” Hanxue Yanjiu (Chinese Studies) 32: 4.

- Tim, L. C. 2016. “Spatial Analysis of the Temples in Guangzhou during the Daoguang Period and Its Meaning: A Case Study of the Guangzhou Shengcheng Quantu.” Journal of Chinese Studies 63 151–201.

- Turner, A. (2001). “Angular Analysis.” Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 3rd international symposium on space syntax.

- Wang Ning, D. Y. 2015. “Resident Walking Distance Threshold of Community.” Transport Research 1 (2): 20–24+30. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/10.1323.U.20150821.0957.004.html

- Xitai, Q. 1996. China Daojiao shi (xiuding ben) di san juan 中国道教史 (修订本) 第三卷 [History of Chinese Taoism (Revised) Volume 3]. Chengdu, China: Sichuan People’s Publishing House.

- Yamu, C., A. van Nes, and C. Garau. 2021. “Bill Hillier’s Legacy: Space syntax—A Synopsis of Basic Concepts, Measures, and Empirical Application.” Sustainability 13 (6): 3394. doi:10.3390/su13063394.

- Yingning, C. (2000). “Dao jiao yu yang sheng 道教与养生 [Taoism and health preservation].” 道教与养生.

- Yuantai, X. 2011. 中华传统宗教信仰在东南亚的蜕变: 新加坡的道教和佛教研究= Transformation of traditional Chinese religious beliefs in South-East Asian society: A case study of Taoism and Buddhism in Singapore. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University.

- Yu Bo, G. P. 2021. “Research on the Spatial Form of Taiding Historic District in Anshan City Based on Space Syntax.” Housing Science 41 (11): 13–16. doi:10.13626/j.cnki.hs.2021.11.003.

- Zhang, P., H. Lin, N. Chitty, and K. Cao. 2016. “Beijing Temples and Their Social matrix–A GIS Reconstruction of the 1912–1937 Social Scape.” Annals of GIS 22 (2): 129–140. doi:10.1080/19475683.2016.1158735.

- Zhongjian, M. 2000. “Guan yu sheng huo dao jiao de si kao 关于生活道教的思考 [Reflections on Living Taoism].” China Taoism 2, no. 2: 54–55.

- Zinan, S. 2012. Yi Lin Hui Kao 艺林汇考 [Take an examination of art circles remit]. Vol. 12. Shanghai, China: Eastern Publishing Co.

Appendix

![Figure 16. INTEGRATION [SEGMENT LENGTH WGT]-Rn (Source: Drawn by author).](/cms/asset/6739b0e3-33eb-483f-9151-c032878eb3a9/tabe_a_2160209_f0016_oc.jpg)