ABSTRACT

The development process of global tropical architecture in the middle and late 20th century is investigated in this study. The architectural shading practices of Le Corbusier and Hsia Changshi in the same period are compared. The similarities and differences between the tropical architectural practices in the Lingnan area of China and the global tropical architectural movement are discussed. Since the 1930s, Le Corbusier explored the method of “brise soleil” in the hot climates of Africa, South Asia, and Latin America, exerting an essential influence on the tropical architectural forms in these areas. Similar forms of shading were widely used in architectural practice by Hsia Changshi in the Lingnan region of China. A hybrid feature in his architectural exploration was related to his early experience of studying abroad and working with Le Corbusier. The study presents the shading design practices of two architects, Le Corbusier and Hsia Changshi, in the tropical climate environment, and extends the architectural development in the regions where their respective works are located. The presentation and comparison of architectural history in this period deepen the understanding of the internal relationship between tropical architectural forms in different regions from a global perspective.

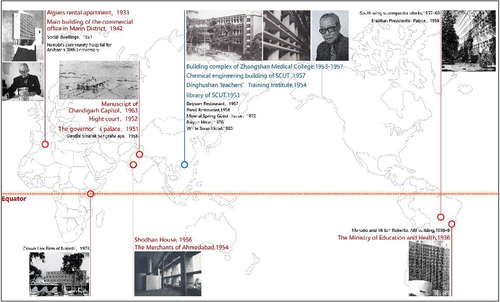

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The adjective “tropical” is generally employed to describe the characteristics of a region or climate. The tropics occupy a vital part of the Earth’s surface, while the architecture here receives relatively little attention. Tropical regions are broadly distributed throughout the world, including the far-flung Caribbean islands, India, Southeast Asia, and much of Australia, Africa, and Central and South America. Regardless of their different cultures, they share similar climatic and ecological characteristics, as well as common post-colonial conditions and the pressures of modernization in the era of globalization. The way the architects respond to the tropical context is as varied as the landscape itself. Tropical architecture indicates an area with similar climatic conditions. Buildings with characteristics resulting from this climatic zone are generally called tropical architecture. Nevertheless, the tropical architecture discussed in this paper carries with it a certain complexity: it is global and cross-cultural, rather than tropical. The concept of “Tropical Architecture” originated in the British Empire in the 1930s. It was initially led by healthcare engineers. Architects adopted the accumulated knowledge of tropical climate and hygiene to develop architecture suitable for colonies. Around the middle of the 20th century, many Western modernist architects, who worked for former colonies, promoted Modernism in Tropical countries and regions and fused it with the climate, culture, and history of the tropics, stimulating the global development of “Tropical Modernism” (Chang and King Citation2011). Tropical modernism, rather than a fixed concept, is a phenomenon of cultural integration, a result of the collision of civilizations, and a process of the discourse turning of tropical architecture not (Veronica and Huaqing Citation2019; Dunster Citation2002). Particularly, tropical modern architecture features simple forms, bare-leak concrete, building layouts for hot climates, and sun-shading facades. Le Corbusier’s shading practice discussed in this study is essential in this architectural movement.

Around the 1930s, the architectural ideas and forms created by the Western Modernism movement gradually spread around the world. Different from the situation in developed countries such as Europe and America during the same period, the spread of modernism in Asian, African, and Latin American countries is inextricably linked to the form of the political economy dominated by colonies. Modernism demonstrates strong adaptability by connecting with local hot climates, cultures, and ideologies. In the mid-20th century, this idea and form became even more critical with the fading of the colonial wave and the independence of emerging nations (Curtis Citation1996; Duanfang Citation2011; Shaopang Citation2019). An architectural practice known as “Tropical Modernism” was recognized and actively involved in the reconstruction process of Third World countries and regions. Since the 1930s, Le Corbusier first proposed the concept of “brise soleil” and explored a series of architectural shading methods: a concrete sunshade and canopy designed based on the motion of the sun, in response to the hot climate of tropical countries. He had a profound impact on the development of modern architecture around the world. However, the evolution of tropical architecture was vague. On the contrary, tropical architecture, which has always been engaged in political discourse, nationalism, and global impact, exhibited the mixed characteristics of the post-colonial era and gradually layered into an extremely complex cultural landscapeFootnote1

The Lingnan region of China is located on the edge of tropical Asia with a hot and humid climate, and the practice is a vital part of global tropical architecture. In the 1950s, Lingnan architecture displayed a general trend of “transplantation” of tropical modernism – horizontal lines, sunscreens, and free planes, which corresponded to the economic environment and productivity level at that time. During this period, Hsia Changshi, a Lingnan architect who returned home after European education, explored the shading form of Lingnan’s modern architecture. In the late 20th century, nonetheless, Lingnan’s modern architecture turned to the exploration of regionality and culture, and its “tropical features” became blurredFootnote2

In this study, the shading practices of Le Corbusier and Hsia Changshi are sorted out, and their simultaneous exploration of tropical architectural forms is compared, so as to clarify the spread of modernism in tropical countries and regions.

2. Extension and Alienation: Le Corbusier’s Tropical Architectural Heritage

2.1. Le Corbusier’s architectural shading practice in tropical countries

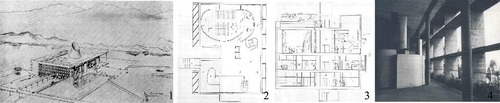

Since the 1930s, buildings in tropical countries and regions such as India, Brazil, and North Africa have been subjected to different degrees of modernization. These movements establish a connection with the local hot climate, presenting a tendency to transplant modern architecture. During this period, Le Corbusier first came into contact with projects in tropical countries, where he continued to draw up urban plans for Algiers in North Africa. In the house, a “brise soleil” adapted to the local hot climate was designed, and the ground floor of the building was elevated for good ventilation. In 1938, Le Corbusier designed a “glass wall + concave balcony” in a commercial office building planned for the Marin District. Regrettably, none of these plans were implemented () (Boesiger Citation1995b vol 2,3). However, members of the ATBAT design team formed in 1951 to build apartments in Marseilles later came to Morocco to design and build a series of social dwellings, which demonstrated the advancement of shading and ventilation measures in high-density housing. Since the 1950s and 1960s, the modern architectural practices of Ernst May from Germany and Amyas Douglas Connell from the UK have considered the special local climate in East Africa under the influence of Le Corbusier’s ideas. Connell’s vertical shading in Nairobi’s community hospital designed for Arkham’s 50th anniversary blends concrete style with the environment.

Figure 1. Le Corbusier's shading scheme in Africa.

When Le Corbusier first visited Brazil in 1929, he exerted a strong influence on the work of Lucio Costa and many others. It was a two-way street, Le Corbusier and his Brazilian colleagues borrowed much from each other at a time when modernist principles were undergoing refinement. Lucio Costa persuaded the Ministry of Education and Health, Gustavo Capanema, to appoint Le Corbusier as a consultant on the design of the health building for the Ministry of Education and Health (Nobre, Xing, and UNICAMP Citation2015, 30–31). Le Corbusier visited Rio de Janeiro in June 1936 for four weeks to discuss plans. Oscar Niemeyer became Le Corbusier’s de facto translator, translating his design ideas for other team members. Le Corbusier was able to perform experiments for the first time with movable “brise soleil” in a tropical climate. In the design of the Ministry of Education and Health, a movable shading system has been used to precisely control the indoor light environment. In the early development of the design, Costa made a sectional diagram indicating how the moveable louvers would relate to the diurnal passage of the sun – as the sun reaches different heights. A lever can adjust the angle of the three louvers independently in each egg-crate module, so as to best shade a given room in the interior() (Almodovar et al. Citation2008; Barber Citation2020).The legendary team worked for about one month, and the implementation plan was finally completed by a group of young architects, including Oscar Niemeyer, Afonso Eduardo Reidy, Carlos Leao, Ernani Vasconcelos, and Jorge Moreira. For the most part, Le Corbusier’s first visit to Rio de Janeiro was crucial in developing a dialogue between Brazil and Europe on the subject of modern architecture. It provided Le Corbusier with a wealth of imaginative material. Since then, Brazil had gradually become the center of global modernist history. Le Corbusier’s use of bare-leaky concrete structures and adjustable “brise soleil” in the Ministry of Education and Health is a fusion of modernism and Brazilian history. A group of modern Brazilian architects such as Lucio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer are firm followers of Brazilian modernist architecture with this feature. They created many architectural masterpieces, shaped Brazil’s new national symbol in the construction of Brasilia, and formed the Rio (Carioca) School of Architecture, significantly contributing to the development of modern architecture. This is the golden age of modern architecture in Brazil, but also in Latin America. After the 1990s, a new generation of Brazilian architects brought a more diverse landscape to Brazilian architecture. The discourse system of Brazilian contemporary architecture is complex, with a stronger global rather than local character. Brazilian contemporary architecture can still find inspiration in nature, climate, and culture () (Mindlin and Giedion Citation1956; Williams Citation2009). Indian architecture embraced modernist ideas in the 1950s, and Le Corbusier experimented with shading in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad once again. Notably, both two permanent shading elements, “canopy” and “brise soleil”, were employed in the Chandigarh courthouse and parliament building simultaneously and became an essential form of architectural expression. This “canopy” appears in many of Le Corbusier’s projects (such as High court, The governor’s palace, Shodhan House, The Merchants of Ahmedabad, and Centre Le Corbusier) () (Boesiger Citation1995b vol 6; Boesiger and Girsberger Citation1971; Sendai Citation2012, Citation2005; Prakāsh and Khan Citation2002).

Figure 2. Details of shading design in the Ministry of Education and Health.

Figure 3. Shading practice in modern architecture in Brazil.

Figure 4. A section of Le Corbusier’s “canopy” form.

In the Millowners’ Association, built in 1957, Le Corbusier calculated the depth and angle of the sunshade following the latitude characteristics and the solar operation law of Ahmedabad. Meanwhile, he detached the shading frame from the wall to strengthen ventilation and set up pools and gardens on the roof to cool down. These designs exhibit the passive adjustment mechanism for the extreme climate in modernist architecture () Curtis and Le (Citation1986).

Figure 5. Le Corbusier's shading practice in India.

Le Corbusier’s 20 years of modern architectural practice have become a prelude to the modernist movement in major tropical countries and regions around the world and have inspired local architects to explore the climatic adaptability and cultural transmission of modern architecture (). Between 1907 and 1947, Le Corbusier produced numerous books, articles, interviews, lectures, and letters. He devoted himself to publishing and distributing his works to promote his architectural ideas (Boyer Citation2011; Danting Citation2019)Footnote3 Concurrently, modernist ideas spread rapidly under the support of local governments.

Table 1. Two types of architectural shading design by Le Corbusier.

2)Louvers and louver-adjustment system at the Ministry of Education and Health(Source: Barber Citation2020, 70–71).

2.2. Multi-landscape of modern tropical architecture

From a global perspective, tropical architecture after the 1950s and 1960s has undergone alienation” to varying degrees owing to the reconstruction of national identity in the postcolonial era. This is accompanied by a paradoxical acceptance of globalization and internationalism. Tropical African architecture has gradually absorbed the economic (low cost, rapid construction, standardization) and practical (shading, ventilation) characteristics brought by modernism in the long-term integration of European culture. However, this trend rapidly shifted to exploring regional and structural manifestations along with the strengthening of political independence. In the Crown Law Firm of Nairobi, built in 1979, Cornell combines modern architectural forms with African traditional decorative languages to illuminate the regional imagination of new African buildings (Folkers and Buiten Citation2019; Yuanzhao Citation2016). Charles Correa and Balkrishna Doshi were also aware that a mere response to climatic modernism can lead to a lack of regional culture. In the 1960s, they explored the cultural expression of India in the designs of the Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya and the Institute of Indian Studies separately to transform the “function, form, and space” concerned by modern architecture into a new Indian spirit of “native, traditional, and regional”. Although the germination and development of modern architecture in Brazil have the nature of cooperation between native and western countries, the core has always been rooted in the tropical soil of Latin America, and its trajectory has become complicated since the 1950s. After collaborating on the Ministry of Education and Health with the Le Corbusier-style——the typical honeycomb shading design and the bare-leak concrete facade, Costa and Niemeyer continued their exploration of tropical climate adaptation in the Brazil Pavilion at the New York World Expo, which was beyond focusing on “shading”. From the 1950s to the 1970s, the diversified performance of concrete was reached by the improvement of formwork and technology. Niemeyer translated the plasticity of concrete into the cultural expression of freedom and elegance in Brazilian architecture and reinterpreted tropical modernism in Brazilian architecture () (Papadaki Citation1960; Zhao and Ruxin Citation2019; Yunlong and Xiangning Citation2019).

Crown Law Firm of Nairobi,1979. (Source:Yulin Citation2005:141).

Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya,1958.(Source:Ashram 1995:56).

Institute of Indian Studies,1959 (Source: Yuan 2021:23).

Brazilian Presidential Palace,1958 (Source: Papadaki Citation1960, 81).

3. Transplantation: Hsia Changshi’s Exploration of Lingnan architecture

In southern China, Lingnan architecture is mainly distributed in Guangdong and Guangxi China. Influenced by the hot and humid climate, Lingnan architecture draws on the “environmental concept” of traditional Chinese architecture. Specifically, courtyards, patios, and shading systems are employed to adapt the building to the environment. The Lingnan modern architecture before the 1950s combined the characteristics of tropical modern architecture with a distinct passive climate adaptation(Shao Sun 2013).

Hsia Changshi’s study in Germany in the 1920s and his brief experience of working with Le Corbusier in Paris (K□gel and Liyan Citation2010, 23–24) were critical reasons for adopting the language of modernism in his architectural practice in 1950sFootnote4 Similar to the shading practices in modern architecture in Brazil and IndiaFootnote5, Hsia Changshi utilized horizontal, vertical, or net sunshades in the design of the biochemical building of the Zhongshan Medical College to wrestle with the intense sunshine in the Lingnan area and improve ventilation, demonstrating the hybrid characteristics of modernism and hot climate. Hsia Changshi’s representative sunshade design method was mainly used in many of his architectural works from 1951 to 1966.His architectural career was closely related to China’s political environment. From 1966 to 1972, he was involved in the political movement, subjected to political criticism, was imprisoned, and lost the opportunity of architectural creation and practice, and his unique sunshade design method was subsequently interrupted (K□gel and Liyan Citation2010, 27–28; Jian and Xiaoling Citation2012). Although I returned to Guangzhou in 1982 to participate in and guide architectural design, this shading design method was no longer applicable to the social environment at that time.With the involvement of a group of overseas architects in political events in the late 1960s, Hsia Changshi’s “shading design” was interrupted (Rui Citation2010). This Lingnan architectural practice with the characteristics of tropical modernism could not be sustained.

The practices of tropical architecture in the Lingnan region are in sync with the global tropical countries and regions. After the 1960s, Lingnan architecture wandered among modernity, nationality, and regionality. Mo Bozhi and She Junnan extended the modern practice of Lingnan architecture to the environmental dimension and integrated the Lingnan garden space with regional characteristics (Yiqiang Citation2015). After the reform and opening up in the late 1970s, Lingnan architecture was affected by the introduction of new materials such as glass curtain walls, enclosed space forms such as indoor atriums, new building types such as super high-rise buildings and large shopping malls, and new technologies such as air conditioning systems into the Chinese construction market. The most prominent influence is that the architectural forms of Lingnan architecture become more diversified, with a considerably huge number of large public buildings and commercial buildings with indoor atriums as spatial patterns, as well as “glass curtain wall buildings” isolated from the urban environment (Baiyun Citation1977; Delin, Jiang, and Subin Citation2016). The types, Spaces, materials, and structures of Lingnan architecture are becoming more diverse, and the regional characteristics of its integration with the environment are gradually lost, while the international style dominates. The influx of new ideas and technologies pushed Lingnan Architecture into a more diverse and open global vision.

3.1. Shading: Hsia Changshi’s practice of tropical modernism in the Lingnan region

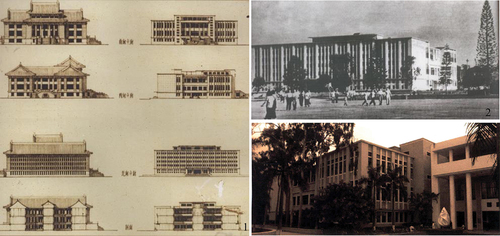

Due to the changeable social environment and complex construction background, the styles and forms of modern Chinese architecture exhibit a “mixed” feature, especially in the Lingnan area with frequent foreign exchanges. As a crucial role in the modern architecture movement in Lingnan, Lin Keming’s architectural design in the 1930s manifests a fierce confrontation of self-contradiction. In the design of National Zhongshan University and Xiangqin University, Lin Keming adopted two completely different architectural styles (the Chinese traditional style and the “Modern” style) and did not involve climate issues.

An essential change in architectural vision began to emerge in the early 1950s. The imperative changes of architectural vision emerged in the early 1950s. The design and construction of the South China National Exhibition and Exchange Conference in 1951 is a concentrated reflection of Lingnan’s modern architecture at the climate level. Architects comprising Lin Keming, Hsia Changshi, and Chen Boqi participated in the planning and design of 12 exhibition halls. This batch of architecture weakens the classical composition and traditional roof form and combines the architectural form with the Lingnan climate by adopting the modernist language of the flat roof, thin column, free plan, and free facade.

In response to the characteristics of the hot and humid climate, Hsia Changshi respected the original design layout and spatial pattern while continuing the construction of the library of the South China University of Technology (SCUT) in 1951, and improved the internal ventilation by adding a patio and widening the corridor. Vertical shading panels and corridors are employed to reinforce the shading effect. The characteristics of environmental regulation with vertical sunshades have not been revealed owing to the continuation of the original building. Its facade is more reflected as a “decorative” composition using the continuation of vertical lines, which cannot obtain the ontological representation in structural form () (Song and Minghua Citation2013). In just a few years since then, nonetheless, the climate-responsive design performed by Hsia Changshi in the architectural practice of Zhongshan Medical College and the South China University of Technology reflects the “climate” turn of Lingnan modern architecture. Moreover, this form developed to grapple with the hot and humid climate has been characterized by distinctive “tropical modernism” from the beginning.

Figure 7. South China University of Technology library materials.

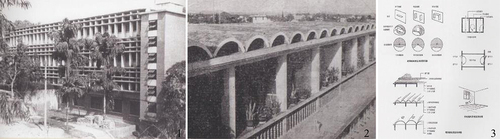

In a paper entitled “Cooling Problem of Subtropical Buildings – Shading, Heat Insulation, and Ventilation”, published in the Journal of Architecture in 1958, Hsia Changshi studied the law of solar azimuth and radiation angle in the Lingnan area and summarized the cooling measures such as shading and heat insulation widely used in several buildings (such as Zhongshan Medical College, Dinghushan Teachers’ Training Institute, and South China Institute of Technology) in the 1950s () (Changshi Citation1958; Anhai Citation2010). In the “shading experiment” during this period, Hsia Changshi always tried to seek a balance among shading performance, ventilation, engineering cost, and facade integrity, and conducted a series of adjustments and optimizations on the adaptability of facade shading components. Additionally, the concrete integrated sunshade eaves used in the Biochemical Building of Zhongshan Medical College (1953) protruded 1 meter from the wall, with a large shadow range and strong compositional integrity, so as to ensure the shading effect. However, the number of horizontal sunshades is too dense. As a result, the size is too thick, and the protruding wall is too far. Despite a certain distance between the integral component and the wall, it still exerts a bad impact on sunlight and ventilation and causes the visual effect of an overweight facade. Subsequently, the Drug Building of Zhongshan Medical College (1954) adopted a simplified combination of double-layer horizontal sunshades and vertical structural columns, enabling the façade to be stretched and light and the cost to be appropriately reduced. Nevertheless, it lacked vertical sunshade measures. This contradiction has been tackled in the expansion of the pathological anatomy building of Zhongshan Medical College (1953). In Hsia Changshi’s design, horizontal precast slabs and longitudinal brick walls are combined to make the facade of the building show lightness. In the expansion of the chemical engineering building of SCUT (1957) and the foundation building of Zhongshan Medical College (1957), the “individual comprehensive” shading formed by the combination of vertical hollow brick and horizontal louver has been developed and exhibits a three-dimensional facade ().

Figure 8. Hisa Changshi's architectural shading practice.

Table 2. Comparison of Facade Components of “Hsia’s Shading”.

Since the 1950s, the practice of Lingnan architecture based in Guangzhou has been explored from the aspects of environment, layout, shape, and elevation. Hsia Changshi’s shading exploration from 1953 to 1958 is a crucial clue in Lingnan’s modern architecture. Under the relatively relaxed social environment in Guangzhou at that time, Lingnan architects were able to turn their vision to the climate issue from the group of Chinese architects who were deeply troubled by the ideology of “form” and “style”. It was driven by Hsia Changshi’s transplantation of modernism in the Lingnan area after accepting the influence of the modern architectural movement in Germany (Changxin Citation2010). The “tropical modernism” characteristic of Hsia Changshi’s works allowed the Lingnan architectural to be part of the global tropical architectural movement after the end of World War II and established a connection in concept, form, and technology.

3.2. Towards regionalism: The continuation of the tropical architecture in Lingnan

The “tropical” practice of Lingnan architecture is influenced by shifting political winds and ideologies even from the climatic perspective of modern architecture established. In 1967, Hsia Changshi was politically criticized, and all the construction projects he had undertaken were forced to terminate. Since then, the vision of Lingnan’s modern architecture has been subjected to another shift in a short period of time.

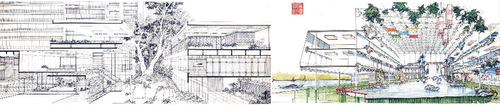

Beginning in the 1960s, the climatic response of Lingnan’s modern architecture presented a combination of modern functions, diverse shapes, and “tropical garden” spaces, concentrated in several leisure, dining, and hotel buildings at that time. The architectural practice of Mo Bozhi and She Junnan is continuous and diverse. In small buildings such as Panxi Restaurant, Beiyuan Restaurant, and Mineral Spring Guest House, they combined garden space with functional rooms and placed empty corridors (). In the design of foreign-related hotel architectures, the low-rise gardens can participate in climate regulation while serving as a “transition” form to reconcile the relationship between body shape and environment. During this period, the intervention of tropical gardens made Lingnan buildings present a rich and cascading compositional relationship (Shaopang Citation2011).

Figure 9. The practice of Lingnan architecture in Mo Bozhi and She Junnan.

Active air-conditioning technology was adopted in a small amount in the 1960s and 1970s, while its extensive use in large and medium-sized hotel buildings represented by the White Swan Hotel in the 1980s demonstrated a “revolutionary” meaning. Specifically, open garden space is gradually replaced by an enclosed inner courtyard equipped with a full air-conditioning system. The “Hometown Water” courtyard on the east side of the White Swan Hotel, built in 1983, is covered with a “Tibetan-style” glass skylight, and the air-conditioning system is employed to precisely control the temperature and wind environment of the 30-meter-high atrium space (). The facade of the tower strengthens the sense of volume through the light and dark relationship of the slanted small balconies but not the horizontal sunshade. The Overseas Chinese Hotel, which was completed in the same year, has a split-level indoor atrium integrating landscape gardens and commercial functions. The tropical language of Lingnan architecture was weakened during this period. This trend becomes more significant in public cultural buildings that emphasize more modeling expression and highly rely on artificial cooling.

Figure 10. The change of environmental regulation mode of Lingnan Building Atrium.

4. Conclusions

During the 20 years before and after the mid-20th century, the discourse of modernity spread into a gradually flourishing landscape in tropical countries and regions around the world. The shading practice of Le Corbusier, rather than a complete picture of modern architecture in tropical countries, reveals the possibility of combining modernism born in Europe with tropical countries. First, his “Shade” explores a path on how modernist universal materials and forms can be properly used in a tropical climate. Second, climate, health, and comfort become the next crucial puzzle in the discourse system of modern architecture. The cognition and definition of tropical architecture have been expanded in the increasing research on tropical architecture. In the current post-modern context, heterogeneity and pluralism are better than homogeneity and singleness. Nowadays, researchers should overstep the concept of tropical architecture as an architectural image, an architectural style, or an architectural feature based on the physical attributes and environmental and cultural background of the tropical region. The concept of tropical architecture is not only a homogeneous western concept in the post-colonial context but is also rooted in the idealization of such a context. Briefly, it is regarded as a complex network of physical matter and architecture, diverse thoughts and languages, competing cultural imaginations, and ideologies (Veronica and Huaqing Citation2019).

Given China’s heavy traditional constraints and complex social background, Hsia Changshi’s shading practice is a more unique exploration. His practical significance is to present a possibility of cultural hybridization rather than bringing a specific architectural form. Although it only existed for a short period of 10 years, Hsia Changshi’s shading practice is a vital dialogue between Lingnan architecture and global tropical architecture, as well as a far-reaching dissemination of modernism in the Lingnan region. The complexity of eliminating geospatial constraints and placing Lingnan architecture in a global tropical architecture case study is that Lingnan in China is located in the offshore area of the Asian continental plate, and its modernity of “compatibility and mutual learning” is an inevitable manifestation of its geography. However, it is difficult to identify the exploration of Lingnan tropical architecture in the late 20th century regarding the transitional climate between tropical and subtropical renders. Moreover, the ontology discourse of Lingnan modern architecture has not been formed ascribed to several changes in domestic political trends since the 1950s. Consequently, it has been engaged in architectural innovation driven by regional introspection and globalization. Based on this complexity, the tropical architectural cues presented in this paper are a selected chain, instead of a holistic description across time periods.

The similarity and almost synchronous development track with global tropical architecture suggest that Lingnan modern architecture becomes a unique sample of the tropical architecture system. Whether it is cross-cultural and retrospective historical research on this architectural practice from the perspective of genealogy, or the practical needs of contemporary architectural environment issues, the practice of Lingnan modern architecture is an essential tropical heritage to be excavated, combed, and reconstructed.

Here is a list of Le Corbusier's important works:

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Wei Yuan

Wei Yuan is a PhD candidate in architecture at South China University of Technology in Guangzhou. His research focuses on modern architecture, both western and Chinese. He received his bachelor's degree from Changsha University of Science and Technology in 2016 and his master's degree from South China University of Technology in 2019. He has studied and worked in several architectural design studios, including the Architectural Design and Research Institute of Hunan University and the Architectural Design and Research Institute of South China University of Technology.

Yang Ni

Yang Ni is a Chinese master of engineering survey and design (2010), president and chief architect of Architectural Design and Research Institute of South China University of Technology, doctoral supervisor and researcher of School of Architecture. He is a Visiting Fellow at the Harvard School of Design (GSD) and an honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, RIBA. He is also the president of the Guangdong Registered Architects Association, the executive director of the 14th Council of the Architectural Society of China, the executive deputy director of the Lingnan Academic Committee of the Architectural Society of China, and the vice president of the Urban Design Branch of the China Survey and Design Association. He received his bachelor's, master's and Doctor's degrees from the Department of Architecture at South China University of Technology. He is mainly engaged in the design and research of public cultural buildings, exhibition buildings, super high-rise buildings and climate-resilient green buildings.

Notes

1. See (Veronica Wu, Huang Huaqing. Asian Tropical Architecture. World Architecture, 2019(3):6).

2. The term ”tropical character” indicates the common features of modern tropical architecture worldwide between 1930 and 1960 – simple forms, bare concrete, clear structural relationships, building layouts for hot climates, and sun-shading facades (window holes, sun shields). These features are the result of Western architects blending the language of modernism with the climate, culture, and history of tropical countries and regions. The climate of the Lingnan region is close to a tropical climate. Architect Hsia Changshi’s works around 1950 have a strong ”tropical character”.

3. Between 1907 and 1947, Le Corbusier produced numerous books, articles, interviews, lectures, and letters. Le Corbusier devoted himself to all matters related to the publication and distribution of his works, and designed the layout and covers of most of his books himself.In letters and articles, Le Corbusier was good at using original words and expressions to communicate while combining paintings and tables to clarify his ideas. Generally, the artistic thought of Le Corbusier spread in Europe, South America, Asia, and other places mainly through the following ways: 1) the direct influence of Le Corbusier’s works; 2) the influence of Le Corbusier’s theories. His works have been translated into English, Japanese, Chinese, and other languages, becoming the number of architects must read. Concurrently, Le Corbusier’s speeches around the world are also a critical method to spread his artistic thoughts. 3) The architects who once worked in Le Corbusier’s office continued to develop Le Corbusier’s design concept after leaving the office or returning to their respective countries, allowing the modern architecture of Le Corbusier to exert a lasting influence.

4. According to his memoirs, Hsia Changshi worked briefly in Le Corbusier’s Paris studio from the summer of 1928 to the end of 1929. At the time, Le Corbusier was busy designing the Villa Savoy and the Villa Mandelot.

5. The ”Practice of shading in modern architecture in Brazil” indicates the ”brise soleil” design represented by the Ministry of Education and Health – adding concrete shades to the facade to regulate sunlight and ventilation. Costa, Niemeyer, and other Brazilian modernist architects have adopted various forms of concrete sunshades in many projects

References

- Almodovar, M., Jose. 2008. “Nineteen Thirties Architecture for Tropical Countries: Le Corbusier′s Brise–Soleil at the Ministry of Education in Rio de Janeiro.” Journal of Asian Architecture & Building Engineering 7 (1): 10–11. doi:10.3130/jaabe.7.9.

- Anhai, S. 2010.Outstanding Modern Architecture in Lingnan. Volume 1949~1990 [M]. China Architecture and Construction Press:80–81.

- Baiyun Hotel Design Group. 1977. “Guangzhou Baiyun Hotel.” Journal of Architecture (2): 18–23+17–53.

- Barber, D. A. 2020. Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning. Princeton University Press.

- Boesiger, W. 1995a. “Le Corbusier - Œuvre complète.” 2: 1929–1934. Birkhäuser Architecture:154.

- Boesiger, W. 1995b. “Le Corbusier - Œuvre complète.” 3: 1965–1969–5352–53. Birkhäuser Architecture.

- Boesiger, W., and H. Girsberger. 1971. Le Corbusier 1910–65. Le Corbusier 1910–65 (degruyter.com). Boston: Birkhäuser Verlag 288

- Boyer, M. C. C. 2011. Le Corbusier homme de lettres. Princeton Architectural Press.

- Chang, J., and A. D. King. 2011. “Towards a Genealogy of Tropical Architecture: Historical Fragments of power‐knowledge, Built Environment and Climate in the British Colonial Territories.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 32 (3): 283–300. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9493.2011.00434.x.

- Changshi, H. 1958. “Cooling Problem of Subtropical Buildings – Shading, Heat Insulation and Ventilation.” Architectural Journal 10: 36–39+42.

- Changxin, P. 2010. “Regionalism and Realism: Hsia Changshi’s Conception of Modern Architecture.” Southern Architecture (2): 36–41.

- Curtis, W. 1996. Modern Architecture Since 1900. 3rd ed. Phaidon Press.

- Curtis, W., and C. Le. 1986. Le Corbusier: Ideas & Forms. Phaidon Berlin.

- Danting, S. 2019. “Le Corbusier Artistic Thought Research [D].” Wuhan University of Technology 213-237: 289–297.

- Delin, L., W. Jiang, and X. Subin. 2016. History of Modern Chinese Architecture (Volume 4). China Architecture and Construction Press.

- Duanfang, L. 2011. “Third World Modernism: Architecture, Development and Identity.” Architectural Research Quarterly 15 (4): 374.

- Dunster, D. 2002. Architecture and Modernity: A Critique of Hilde Heynen. The MIT Press.

- Folkers, A. S., and B. Buiten. 2019. “Modern Architecture in Africa: Practical Encounters with Intricate African Modernity.”

- Jian, T., and T. Xiaoling. 2012. Architect Hsia Changshi, 172–177. South China University of Technology Press.

- K□gel, E., and Y. Liyan. 2010. “Between Innovation and Modernism: Hsia Changshi and Germany.” Southern Architecture 2: 23–28.

- Mindlin, H. E., and S. Giedion. 1956. Modern Architecture in Brazil. New York: The USA and Canada reinhold publishing corporation.

- Nobre, A. L., F. Xing, and UNICAMP. 2015. “Lúcio Costa Today.” The Architect 06: 30–33.

- Papadaki, S. 1960. Oscar Niemeyer.G.Braziller:81.

- Prakāsh, V., and A. R. Khan. 2002. Chandigarh’s Le Corbusier: The Struggle for Modernity in Postcolonial India[m]. Mapin Publishing.

- Rui, L. 2010. Hsia Changshi Chronology and Hsia Changshi Bibliography. China Academic Journal Electronic Publishing House.

- Sendai, S. 2005. “Idea of Environment and Architectural Form in India by Le Corbusier: On the Creation of Villa Shodhan at Ahmedabad.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 4 (1): 37–42. doi:10.3130/jaabe.4.37.

- Sendai, S. 2012. “Realization of The roof Garden in Ahmedabad by Le Corbusier - on the Creation of Villa Sarabhai -[J].” Journal of Asian Architecture & Building Engineering 11 (1): 17–23.

- Shaopang, Z. 2011. Mo Bozhi’s Architectural Creation Process and Thought Research. South China University of Technology.

- Shaopang, Z. 2019. “A Preliminary Exploration of Some Clues in the Practice of Tropical Modernism in the 20th Century.” Southern Architecture 3: 6.

- Song, S., and Q. Jansong. 2013.Lingnan Modern Architecture,1949-1979[M]. South China University of Technology Press.

- Song, S., and S. Minghua. 2013.Lingnan Modern Architecture [M]. South China University of Technology Press.

- Veronica, W., and H. Huaqing. 2019. “Asian Tropical Architecture.” World Architecture 3: 6.

- Williams, R. J. 2009. “Brazil: Modern Architectures in History. Reaktion Books.”

- Yiqiang, X. 2015. “Regional Genealogy of Lingnan Modern Architecture School and Its Influence.” Times Architecture 5: 6.

- Yuanzhao, H. 2016. African Modern Architecture Before and After the National Liberation Movement (1950s). China Academic Journal Electronic Publishing House. Part II.

- Yulin, W. 2005. The regional development of modern architecture movement (Ph.D. Dissertation, university of tianjin):141.

- Yunlong, Y., and L. Xiangning. 2019. “Cooperative Modernism: Brazilian Architecture and the Formation of the “New State” (1930-1940s).” Journal of Architecture, no. 007: 109–114.

- Zhao, P., and W. Ruxin. 2019. “Two Historical Constructions in Brazilian Modern Architecture.” Journal of Architecture 5: 5.

- Zhaozhang, L. 1997. Manuscript of Lin Zhaozhang’s Architectural Creation. International Culture Publishing Company.