ABSTRACT

This study seeks to identify the significant characteristics of the traditional Najdi courtyard in Saudi Arabia in order to comprehend the typology and applicability of courtyard patterns in Najdi dense urban neighborhoods. The study includes a literature review that investigates the socio-cultural influences on courtyard typology and the typological implications of courtyard residences at both the building and urban scales. The study also includes a case study of six Najdi courtyard residences in three settlements in the central region that analyzes the patterns, characteristics, and spatial qualities of these courtyards. The ethnographic approach is used to observe and document a culture, society, or other phenomenon related to the study objectives through participant observation and interviews, as well as making use of the Space Syntax “justified access graphs” method to understand and examine the organization and spatial order of the traditional dwelling. The study indicates that the courtyard acts as a holistic space and place within the home; however, the features of individual courtyards may vary based on geographical and environmental setting. The conclusion of the research is that courtyard typologies have the capacity to satisfy the enduring cultural, social, and climatic demands of residents and hence might be implemented in contemporary urban contexts. The findings of this research suggest that courtyard typology has the potential to create an environment of comfort, privacy, and special efficiency for modern urban households.

1. Introduction

The courtyard, derived from the Latin word “cohors,” which means “enclosure,” is an open space within a building or group of buildings (Nelson Citation2014). In hot, dry climates such as the Middle East, North Africa, and Southern Europe, the courtyard is an essential component of vernacular architecture (Hakim Citation1986). It is typically enclosed by walls or structures on all sides, which creates a microclimate that can be managed to satisfy the needs of its users in terms of both the environment and social interaction (Memarian and Brown Citation2003). Due to its multipurpose functions, which include passive cooling, natural ventilation, daylighting, and social interaction, the courtyard has become a popular feature in both residential and public buildings (El-Shorbagy Citation2010).

Courtyard space has been an integral part of traditional dwellings for centuries. It is a place where families can come together and enjoy the privacy of their own home while still being connected to the outdoors. The layout of these spaces is designed in such a way that it provides a sense of security and comfort to its inhabitants. Thus, courtyard spaces are often seen as an outdoor extension of the family’s home, providing them with a place to relax and spend quality time with each other. The courtyard also serves as an important element in the overall layout of a dwelling, allowing for ventilation and light into the interior spaces while still maintaining visual privacy.

As an architectural element, the courtyard is often seen as a transitional space between the public and private domain. It serves as a reflection of the cultural traditions of inhabitants, providing a physical representation of their values. However, defining traditions can be controversial, as cultural traditions description is a bridge to set of various ideas that are constantly evolving, and formally influence our daily decisions. It is controversial to the point of being critical to have a definite concept as each discipline approaches the term from a different perspective. However, UNESCO defines “intangible cultural heritage” as traditions which are usually transmitted and expressed in physical forms “the totality of tradition-based creations of a cultural community, expressed by a group or individuals and recognized as reflecting the expectations of a community in so far as they reflect its cultural and social identity” (UNESCO Citation2001). It is critical as through time, the traditions begin to evolve and take different steps and merge with other traditions in a society to form a hybrid of different and newly introduced traditions. Therefore, traditions can be both diverse and dynamic, and thus it is important to understand how this diversity contributes to the unique cultural identity of a society. We can say that traditions are “dynamic” rather than steadfast and static, and by understanding this dynamism, it becomes crucial to the assessment and development of the architecture of a given society.

Beyond the courtyard architectural advantages, this space also offers a range of social and psychological benefits that can enhance the quality of life for inhabitants, these benefits may include privacy, social interaction, outdoor living, connection to nature, and cultural identity. According to Bekleyen and Dalkil (Citation2011), the privacy of Turkey courtyards provided a sense of enclosure for its inhabitants, separating the private realm of the home from the public realm of the street. This contributed to creating a sense of security and comfort for occupants in the courtyard space, particularly in densely populated urban environments. This led the space to serve as communal areas where residents can gather, socialize, and engage in various activities (Lee and Park Citation2015). This fosters a sense of community and social cohesion among neighbors, promoting a sense of belonging and well-being.

To understand the role and importance of the presence of the courtyard space in the traditional dwelling, we need to look at both the tangible and intangible dimensions in order to comprehend the process of making the built environment. Also, we need to evaluate the multiple layers of building processes that a built environment passed through to arrive at its current state. To appreciate a built environment’s final shape, we must appreciate the traditions of its inhabitants, as well as its inhabitants themselves. Despite the use of modern building techniques, until the year 1960 the central region, still relied on local materials in the traditional environment in its construction. This reliance was, in part, because of the economic constraints that people faced and the need to rely on locally available resources. That is why the walls (in most floors and roofs) came to be solid and compact to preserve the privacy of its inhabitants and to encompass the necessities of social and religious beliefs in the region. The courtyard, therefore, became the central space that connected the solid structure of the dwelling to the surrounding environment and its inhabitants.

Due to a contract negotiated in 1968 with an international consulting firm to develop a master plan for Riyadh City, the downfall of courtyard houses in the central region was a clear result. The master plan was implemented four years later, covering an area of 304 square kilometers. It radically altered the nature of the city and laid the groundwork for a new, modern Riyadh which intentionally eschewed the development of courtyard dwellings, among other aspects of the plan. The master plan proposed the segregation of the city into land use zones, redeveloping traditional family dwelling units into more “modern” built forms, and (in sum) offering a more efficient and metropolitan way of life. Despite this rapid shift in urban planning, much of old Riyadh was spared initially. Indeed, the traditional architectural style of the residential districts (inspired by the architecture of the traditional Nadji settlements) was kept far into the 1960s, and a few winding streets lined with mud dwellings may still be seen today. Even so, the implementation of the new master plan irrevocably changed the nature of Riyadh, modernizing the city and reducing or outright eliminating much of its cultural (heritage) architecture that had defined it for decades, if not centuries.

This study suggests that understanding the composition of the traditional Saudi dwelling (overall) is a prerequisite to studying the role and importance of the courtyard space in the traditional Saudi dwelling’s formation. By understanding the composition of the traditional Saudi dwelling, we can gain insights into how the courtyard space contributes to the dwelling’s overall architectural design and spatial formation. This understanding is essential to modern Saudi architectural practice and urban design in the Kingdom in order to ensure that traditional elements of the Saudi home, such as the courtyard, are not lost and are instead incorporated into modern home design in both a functionally-efficacious and culturally-relevant way.

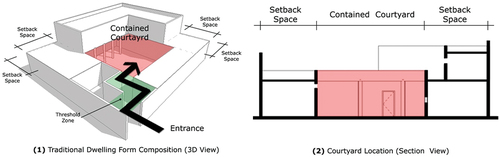

The placement of the courtyard is not spontaneous, and its placement is not necessarily in the center of the house. The courtyard’s placement incorporates several considerations: the dwelling’s position within the surrounding built environment, the dwelling’s shape, its spatial organization, its physical features, and (crucially) socio-cultural influences (). Therefore, this study examines the several factors that shaped the traditional courtyard space in different traditional settlements within the central region of Saudi Arabia; i.e., the “Najd” region’s traditional settlements. The objective is to examine the physically (tangible) and culturally (intangible) significance of the courtyard space in the Najdi traditional dwelling.

2. Literature review

Traditional architecture refers to all buildings from the past that have survived to the current day (Oliver Citation1989). Traditional structures are those with historical connections (Bourdier and Alsayyad Citation1989). They are considered to be a constructed representation of heritage that is passed down from generation to generation, typically the work of ordinary people without professional assistance (Edwards et al. Citation2006; Noble Citation2007). As a result, traditional architecture provides us with an understanding of how past societies and cultures created a sense of identity and belonging.

A “courtyard” is commonly defined as an area enclosed on the sides and open on top that is located in the center of a structure or collection of structures. In his book “Dwellings: The House Across the World,” Paul Oliver reports that courtyard dwellings have deep roots in history, and examples have been unearthed in Kahun, Egypt, that are thousands of years old, some as far back as 2000 B.C (Oliver Citation2007). As one of the oldest architectural components, architects have shown an appreciation for courtyards for a variety of reasons. The courtyard plan provides inhabitants with an important space solution, while it also provides a sense of cultural continuity.

Therefore, the courtyard space is distinguished by its plan structure and the interaction of masses with one another, and it is an important component of the spatial arrangement of a home that can be on the side, in the front, or ensconced centrally within the home (Erarslan Citation2020). This arrangement of masses plays a significant role in giving the courtyard its unique identity and character, creating a sense of space and place that determines how the user interacts with the space, making it both a public and private area, depending on the context (Zhang Citation2020). In essence, the courtyard is more than just a physical space; it is an open environment in which its users can interact, relax, and appreciate their surroundings.

Rapoport characterizes regional architecture as devoid of organizational or aesthetic sense of superiority, in connection with the landscape and climate. Being in sync with other structures in terms of the respect shown to the surroundings as a whole and being open to change within a specific framework (Rapaport Citation2007; Rapoport Citation1969). This respect for nature and local culture is encapsulated in Rapoport’s notion of regional architecture, which focuses on the buildings’ integration with the landscape, their functional appropriateness to the climate, and their harmonious relationship with existing structures. It is a form of architecture that is context-specific, emphasizing building techniques and materials derived from the local environment, as well as considerations such as the use of space and scale in alignment with various socio-cultural values (Sthapak and Bandyopadhyay Citation2014).

Courtyards are classified as “transitional space”, which is a sort of architectural space which make them “in-between” spaces in the final formation of the dwelling (Taleghani, Tenpierik, and van den Dobbelsteen Citation1986). These transitional spaces can be broadly classified based on the dwelling location within the built environment, where different types may emerge “in-between” to support courtyard functionality, such as serving as an arcade, patio, corridor, etc., allowing them to provide a variety of functions that vary depending on the context in which they exist (Al-Hafith et al. Citation2017). Thus, it is a meaningful space within dwellings that can bridge the gap between indoors and outdoors.

2.1. Courtyard space in the Saudi context

In Islamic society, the dwelling courtyard is a multi-functional place that caters to the many social and cultural needs of the residence (Alnaim Citation2006). As the public and private worlds were intertwined in Islamic culture, the courtyard allowed for a balance between privacy and socialization (Akbar Citation1982). Thus, it serves as the focal point of family gatherings that provides a link between the family and the community, functioning as outdoor space while also allowing interaction with private visitors. These important functions led the courtyard to be a crucial part of Islamic family life and culture.

In general, traditional dwellings in Saudi Arabia in the Nadji region form homes adjacent to one another and are compacted, conveying a sense of housing clusters, where the closeness is considered one of the main characteristics of the traditional settlements in the desert environment. Cities usually consist of residential blocks where each residential block consists of several houses, and because the buildings are adjacent in each block, the residents form a binding agreement through common and shared walls and how these walls are used and built (Akbar Citation1998; Husin Citation2016). Thus, social factors played a prominent role in shaping the dwelling and the built environment around it, as the tribal social system led to the adhesion and dialogue of the buildings and their convergence. Also, the layout of each traditional dwelling was directed completely inward, with the courtyard as the main inner private space of the dwelling (Alnaim et al. Citation2023).

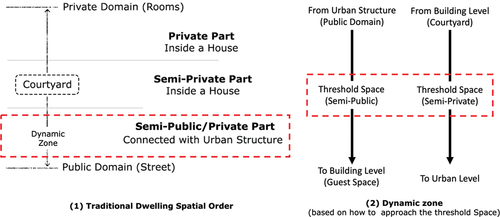

The traditional dwelling in such a context is divided into three main parts (private, semi-private, and semi-public) in order to provide high levels of privacy among the various functional components of the dwelling. Thus, the traditional Saudi dwelling often consists of the following elements: Firstly, the presence of an entrance corridor (threshold), which is a space that functions to link the semi-private and semi-public spaces of the dwelling to provide a certain degree of privacy (which is expected in Saudi society) while entering the dwelling. This space is often covered and connects several main spaces in the dwelling, such as the courtyard and the men’s guest room. Another architectural element is the men’s guest room. Its location within the dwelling is very intentional: it’s often linked with the corridor and close to the entrance of the dwelling to be closer to the outside realm to preserve the privacy of the dwelling and its occupants during male social activities. Therefore, the entrance, the corridor and the men’s guest room are considered a semi-public zone in the traditional dwelling because this part of the dwelling is more linked to the public realm and the outer built environment. Through this configuration, the inner courtyard is the heart of the traditional dwelling, where most of the room openings open to it. The presence of the corridor element is intended to increase the depth of the courtyard into the inner spaces of the house by segregating the courtyard from the entrance’s direct visual contact. This is due to the core function of the courtyard: providing privacy for the family, while also providing shade, protection from dusty winds, as well as functioning as a source of natural light and ventilation. This makes the other functional components of the dwelling as supportive complements to reach the courtyard its main function within the house.

As a result, front, middle, and back are the three sections that encompass the traditional house components (Alnaim Citation2021). The courtyard area is mostly located in the center (middle) of the dwelling and is referred to as the “tummy” (Arabic: batn al-hawi) by Najdi locals. Residents set aside this area for their personal and family use. Locals referred to this area as the “core space” because of its central location and primary purpose. One of the courtyard’s most essential features is its capacity to naturally ventilate and cool adjoining interior spaces while also providing natural lighting without the need for exterior openings (e.g., street-facing windows). This is especially important since the length of “the typical dwelling” external façade is significantly constrained by the condensed urban form. Windows to the outside are scarce in this situation, and where they do exist, inhabitants turn the windows away from one another to prevent any potential visual corridors (Ragette Citation2012). As a result, the courtyard acts as a hub that regulates and provides for the adjacent interior spaces, satisfying social, cultural, and environmental needs.

In addition to being used to support natural environmental factors, the courtyard is significant because it provides a space for a variety of family and social activities. As the courtyard is used for both public and private social events, privacy is a crucial factor in the design of traditional buildings.Footnote1 The family’s multifunctional rooms are connected by a courtyard that controls the flow of individuals through the house during the day and at night. As a result, by keeping the courtyard in the center and encircling it with various interior spaces, the residents were able to determine the finest solutions for their family’s activities without interfering with the outside world by retaining the courtyard in the center and enclosing it with other interior “setback” spaces. Because they offered a semi-private space where the entire family could congregate and develop close bonds, courtyards are therefore inferred to have served as a focal point of family life and unity.

Despite sharing roads, fields, and souq (market) areas, Al-Hussayen observes that women are “restricted from outside to within the home” in such a setting. Due to the restrictions placed on women that are intended to preserve privacy, he notes that the courtyard and the roof are the areas that women use the most (Al-Hussayen Citation1996). Therefore, the courtyard serves as a place for maintaining the privacy standard of the living area inside the traditional dwelling. Although some privacy could be maintained through the use of the courtyard and roof, there was still a clear restriction placed on women. Therefore, Al-Hissayen was persistent and mentioned that residents could ensure that the house’s position and layout satisfied the privacy concerns of the family and society by understanding how it related to other nearby dwellings.

Studying internal threshold areas and their physical components in the traditional settlement communities was crucial to developing a deeper understanding of the courtyard as an architectural element because it showed that the inhabitants had already figured out how to provide their homes with some degree of seclusion. The “hidden meaning” of this space, which helped control the internal spatial order of the traditional home, kept the family’s seclusion from the (majlis) semi-private area (Mortada Citation2016; Rabbat Citation2010). Residents viewed the courtyard as an area that could divide the semi-private areas from the house’s private portions (family multipurpose rooms). The courtyard, in reality, functions as a “threshold” for female guests and family members. As previously mentioned, the family utilized the adaptable/flexible rooms for a variety of activities both during the day when they were open and at night when they were quite limited spaces. As a result, the courtyard contributes to the control of this dynamic use while maintaining the high adeptness of the nearby areas. Thus, the courtyard functions as a threshold for family and female guests by providing a unique place that connects the house’s semi-private spaces with private rooms.

3. Materials and methods

This study uses an ethnographic approach to better understand the societal value of Najdi residents and how they built their traditional dwellings. Ethnographic is a type of social research method used to observe and document a culture, society, or other phenomena through participant observation and interviews (Nurani Citation2008). In architectural studies, the ethnographic approach entails investigating how people use and interact with buildings and spaces, as well as the cultural and social contexts in which these interactions occur. This approach is rooted in anthropology and entails using qualitative research methods such as participant observation, interviews, and focus groups to gain a thorough understanding of people’s relationships with their built environments (Flynn Citation2010). Furthermore, the ethnographic method can be used to investigate the social and cultural significance of buildings and spaces. Examining the symbolic meanings attached to buildings and spaces, as well as the power dynamics and social relationships embedded in them, can be part of this. Overall, the ethnographic approach is a valuable tool for architects and designers who want to create more thoughtful and responsive designs that are grounded in a knowledge of the people and communities they serve (Curran Citation2012; Foth and Tacchi Citation2004).

The ethnographic approach is used in this study to inform the design process by providing insight into how architectural design can accommodate and support people’s needs and behaviors. To inform architects, how they can create more functional and meaningful designs that are tailored to the needs of specific communities by understanding how people use and perceive buildings and spaces.

3.1. Informal interviews

It was critical for this study to collect data on the characteristics of the Najd constructed courtyard environment, as well as how the built environment served the demands of prior residents. To support the ethnographic approach, the informal interview method is used to gather information and insights from individuals in a non-structured, conversational manner (Ahmadi and Habibi Citation2023). Unlike other types of interview’s methods, the informal one is a method to help researchers generate ideas and insights in combination with methods such as this study observation, and ethnography to provide the study with more comprehensive understanding of related topics (Wimpenny and Gass Citation2000).

Therefore, the interviews were conducted with locals during the observation and fieldwork visits targeting topics related to the study’s objectives. Six open-ended questions the participants were asked informally to encourage them to talk about their experiences, opinions, and perspectives, which were as follows:

What are the benefits of having a courtyard space in the house, and how does it enhance the overall living experience?

How is the courtyard space designed/placed to maximize its potential and to create a functional and breathing outdoor area, especially in a compacted and preserved environment such as Saudi Arabia?

What impact can a courtyard space have on the environmental quality of the house, and how did it contribute to the eco-friendly living environment?

What role does a courtyard space play in promoting social interactions and creating a sense of community within a household or neighborhood?

How did the courtyard space used for various activities such as gardening, relaxation, entertainment, and outdoor family social gathering, and how the space was contained to ensure comfort living experience?

What are the cultural and historical significance of courtyard spaces, and how did it contribute to the overall typology of Najdi dwellings?

As the informal method is more of a non-structured conversation type of interview, summarizing the interviewees’ opinions, thoughts, knowledge, experiences, and values regarding the courtyard space is essential. Therefore, a keyword interview-based word cloud graph was generated to formulate relevant ideas during the study observation and site visits with locals. The word cloud seen in () identifies the numerous sub-areas of interest in the courtyard, where the size of a word indicates the number of consistency and repeatability.

3.2. Observation

Observation is a research method used in academic research to collect data about a particular phenomenon or behavior (Urquhart Citation2015). In this method, the researcher systematically observes and records behaviors, events, or interactions that occur in a natural setting. According to Ciesielska, Boström, and Öhlander (Citation2018), fieldwork entails active looking, enhancing memory, informal interviewing, creating extensive field notes, and, most significantly, patience.

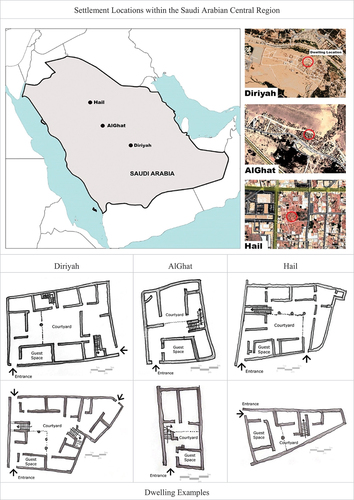

Therefore, during an interval in 2021–2022, we conducted a dwelling observation in three traditional Najdi settlements (Diriya, AlGhat, and Hail) (). Participant observation is the method deployed where the researcher became part of the group being observed to observes their behaviors, events, or interactions from the inside. This approach led the study to focus on practices related to the use of the courtyard, as well as the meaning-making of the courtyard as a family gathering area in relation to the dwelling location within the built environment. We used a variety of methods to collect data, as is common in this type of method, such as conducting observations (three hours, once a week) for each case, recording them as field notes, conducting informal interviews with the elderly and residents, and gathering a variety of documents, including archival data, images, and architectural plans and sections.

3.3. The justified access graph technique (space syntax)

Hillier and Hanson developed several analytical tools that can be used to analyze various architectural qualities (Hillier and Hanson Citation1988). Space syntax methods commonly convert or abstract specific features of spatial arrangement into syntactic characteristics and discrete models to understand architectural space (Bafna Citation2003). Hillier and his colleagues defined several fundamental concepts of space syntax analysis, one of which is used in this study: the “justified access graph,” which is a technique to identify the hidden patterns topology of a building floor plan as a depth diagram from any chosen point such as from the main building entrance or from an inner room (Hillier et al., Citation1976; Turner et al. Citation2001). Overall, space syntax techniques have been widely adopted to comprehend the relationship between spatial configuration and human behavior, such as pedestrian mobility and social interaction.

The first stage in creating a justified access graph is observing and comprehending the spatial relationships of the given spatial arrangement (Ostwald Citation2011). The spatial arrangement is then translated into linkage graphs, which explain the relationship between spatial hierarchy, permeability, and integration/segregation. The justified access graph approach is used in the study to represent these linking syntactic graphs. Thus, the use of justified access graphing analysis allows the researchers to use an analytical comparison technique to not only detect the similarities and differences of architectural aspects, but also to comprehend the social behavior and meanings underlying these various layouts and space linkages (See Elizondo Citation2022; Mustafa, Hassan, and Baper Citation2010).

As a result, this study uses justified access graph analysis to produce a graph or several graphs for a certain spatial configuration analysis. This technique’s graphs aid in understanding spatial hierarchy, permeability (interconnections between areas), depth, and integration/segregation. These variable depth graphs are essential because they are used as a presentation tool to examine the depth and connectedness of distinct patterns among different houses. Through deploying this technique, space configuration can provide a framework for understanding how people interact with the built environment by examining the correlation of different spaces using the justified access graph. The technique is effective for abstractly capturing the topological description of any spatial layout, emphasizing spatial links and accessibility above spatial shape, size, or form.

4. Results: Examining the Najdi courtyard space

This part of the analysis is divided into four stages in order to properly understand the courtyard space and its critical functional role in structuring the internal spaces’ spatial order and increasing the degree of solitude in innately private areas. The four stages are interconnected, focusing on examining the courtyard dynamic, its significance, its environmental aspect, and its role within the dwelling and the surrounding built environment in fostering relationships of inhabitants. This analysis is conducted by observing where the courtyard is located in various traditional homes and how it connects to other inner rooms. Also, using building sections to study a number of nearby courtyards to see how each residence preserved its own courtyard’s seclusion with respect to that of its neighbors. These four stages revealed how the courtyard satisfied the family’s need for privacy and highlighted that the courtyard is an important factor in determining the spatial order of a traditional home’s inner spaces, as it functions to create a connection between the semi-public areas of the home and its more private spaces.

4.1. The dynamism of courtyard space

The courtyard in the center of the dwelling generates an introverted situation that is shielded from outsiders’ visual encounters, making it a suitable location to open to the sky and entertain the family. This allowed the family’s domain to engage with the guest area while also allowing the courtyard to play an essential role in carefully managing entrance to the house. This observation aligns with Roderick Lawrence (Citation1987) and Mohammed Alnaim’s (Citation2021) findings when they examined the hierarchy of the physical arrangement of the traditional house’s internal spaces. Both noted that in traditional houses, the family courtyard served as a physical buffer between guest spaces and private family areas. Therefore, the courtyard’s introverted nature gave it a unique dynamic in traditional houses: on the one hand, it provided a semi-public area “threshold” for entertaining guests without infringing upon the family’s privacy, and on the other, it created a semi-private intimate space for the family.

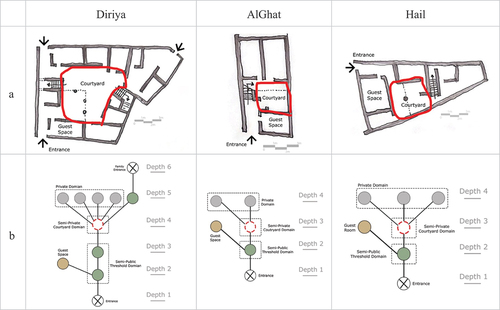

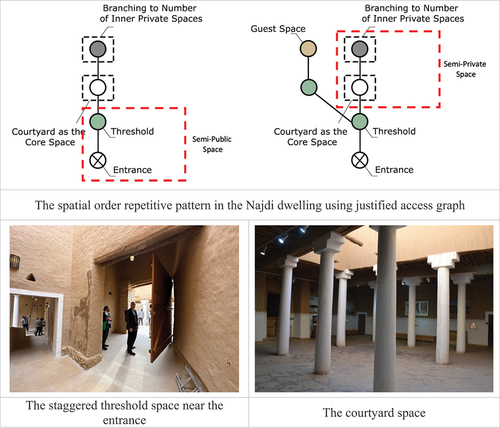

Due to the creation of threshold space and its staggered formation, it segregated the dwelling entry from the courtyard space; thus, the space is not immediately accessible when approaching the house from the entry which creates a dynamic spatial order zone. This threshold zone is changeable in traditional houses based on from which part the courtyard is approached (urban part or building part) and acts as an ideal buffer between the outdoor and interior spaces, adding depth to the family’s space and separating them from the semi-public zone (guest space) (: 1). The threshold area, for example, accommodates the guest room (majlis) or a small shop, which is crucial since it separates the family members and their related private inner areas from such public spaces throughout the day. This provided the family with privacy while also allowing the courtyard area to function as an intermediary space between their home and public life outside. Thus, the courtyard’s dynamic character distinguished it from other types of buildings by utilizing the threshold area as a regulated mechanism between semi-public and semi-private zones (: 2). This is similar to what Nibedita Das et al., (Citation2006) noticed in North African courtyard homes, where a wide range of daily activities, from food preparation, sleeping, working, playing, entertaining guests, and even keeping animals, were traditionally carried out in the courtyard.

After passing through the entry threshold going through the deep private areas, a second spatial arrangement is provided where the user must first reach and go through the courtyard space. As a result, the courtyard serves as a gathering place for the family, connecting various private internal sections of the dwelling. Because it is located in the midst of the semi-private and private areas, the courtyard space integrates various family shared activities (such as family meetings, children’s play, cooking, etc.) while protecting the privacy of surrounding inner spaces. The inhabitants established dynamic spatial ordering to assist the activities of the two realms (public and private) within their dwellings. Therefore, the family’s social and religious needs had an impact and contributed to the development of the two spatial orders to assess various cultural constraints in the traditional dwelling. The desire to keep men’s activities outside of the home and the activities of the family’s within led to the creation of a number of supportive architectural components. These components made sure that the organization of the spatial layout is to separate the many activities inside the Najdi traditional house, to work and enhance its physical formation. This separation was based on the dichotomy between the public and private, masculine and feminine realms. Thus, this dichotomy between the public and private spheres was an essential part of traditional Najdi culture, as it enabled both sexes to be able to maintain their own distinct roles within the household.

Therefore, this study needed to grasp the importance of the spatial arrangement of inner areas in a typical Najdi dwelling in order to appreciate the implicit function of the courtyard space. Examining the courtyard location, two hidden spatial mechanisms were observed, and they appear to strengthen the link between spatial hierarchy and the physical order of internal space placement within the house. As a result, rather than existing as a physical form within the built environment by itself, the dwelling (physical form) exists as a component that promotes spatial integration to formulate the Najdi urban masses. This was observed in the study when traditional house occupants established a method of interacting with the public sphere by maintaining the seclusion of the interior spaces while having a semi-public “threshold” space between the entrance and the courtyard inside the house.

By delving deeper into the role of physical form within urban mass, it is possible to draw conclusions about how traditional houses interact with their surroundings and influence social dynamics within a built environment. Because of their socio-cultural and land space constraints, Najdi residents were forced to rely on the courtyard as the only location that provided access to the vast majority of the house’s components. To keep the courtyard hidden from neighbors, they also enclosed it with “setback” private internal rooms. This resulted in generating a multi-layered and dynamic space that served different functions for the occupants and as a depth space to control and regulate the house’s spatial order. To put this observation to the test, the study’s second stage is focused on understanding the location of various components that improved the courtyard space’s solitude.

4.2. Courtyard’s significance

To comprehend the significance of the courtyard placement, Mohammed Alnaim (Citation2020a) contends that a threshold space typically exists in most traditional Saudi dwellings, revealing that this space offered the appropriate distance for the courtyard to be separated from the dwelling entry and visually hidden from the public domain. The courtyard in this case is situated between the threshold space and the house’s inner isolated zones. The position is crucial since it surrounded the courtyard with its identifiable private inner rooms (: 1). Since all rooms opened to the courtyard, inner private spaces had to operate as a cover from all sides to offer the courtyard’s need for solitude (: 2). This was an essential factor for the well-being of a family living in these dwellings, as it ensured that they had their own personal space to which they could retreat.

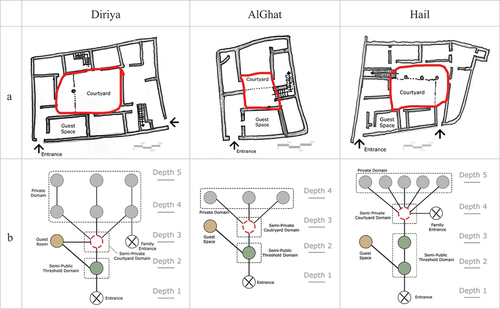

The study looked at various dwellings from the three communities’ courtyard locations to further test this study’s premise. Viewing the floor plan (: A) we were able to separately comprehend the hidden mechanisms that were implemented in the courtyard to control the central portion of the dwelling. Two mechanisms were identified. The first mechanism entails comprehending three phenomena: (1) how the courtyard location is used as an indoor-outdoor environment, (2) how it added depth to the spatial arrangement of internal rooms, and (3) how it controlled the accessibility of various portions of the building. The second mechanism relates to comprehending how the interior private areas of the house served as a cover to safeguard and enhance the courtyard’s privacy from its surrounding neighboring courtyards. The spatial organization of internal spaces was examined by making use of the Space Syntax “justified access graph” approach. The positioning of the courtyard in the hierarchy of indoor spaces may be understood and appreciated thanks to this analytical technique (: B).

It is possible to obtain an understanding of and insight into the courtyard placement inside the traditional house design, as well as the different linkages of the courtyard space inside the house, by analyzing the house layouts and using the created justified access graph analysis. The graphs illustrate that the courtyard is typically located between two significant spaces (the house threshold entrance and the inner private space) (: B). This means that the courtyard is always surrounded by two layers of depth spaces to maintain privacy from both the outside and the inside of the house. As a result, the internal private areas are always reached from the courtyard, according to the graphs, and in some cases, the study revealed another transitional space (the threshold), which served to raise the depth even further. By understanding the spatial relationship between the courtyard and other indoor spaces, one can appreciate how it creates a sense of privacy from its neighboring courtyards, as well as its accessibility.

Therefore, the justified access graph analysis supports previous statements that the courtyard is usually located in the center of the home and functions as a hub that links various rooms inside it, ranging from semi-public to private spaces (). As previously noted, the location is crucial and related to the socio-cultural requirement for household members to participate in their everyday social activities without worrying about invasions of privacy. This is accomplished so that the courtyard space can be physically confined within the very safe internal private spaces. Care is taken to prevent neighboring roofs from making visible contact. Several architectural features were produced and installed to help preserve and heighten the courtyard’s level of privacy. In order to further maximize the courtyard’s privacy, several elements of design were implemented to enhance the courtyard’s functionality and respond to several socio-cultural concerns, which will be further examined in the following sections.

The findings of these elements were aided by several non-continuous site visits between 2021 and 2022 and interviews with residents of Diriya, AlGhat, and Hail. Participants in the AlGhat and Hail interviews recounted their experiences and explained how the courtyard’s central location met the daily requirements of the residents. The courtyard is the busiest area in the house because all private rooms can be accessed from one location thanks to its central location. Interview participants concluded that because internal areas have diverse functions throughout the day and at night, the positioning of the courtyard made it easier to accommodate different activities in these spaces. This may also explain why the study discovered that traditional houses come in different sizes, as the locals developed a creative way to make the most of their small inside areas.

Similarly, when locals from Diriya who had firsthand experience with the traditionally built environment were questioned, they claimed that the elements attached to the courtyard had been added to boost the space’s level of solitude. These elements were primarily found in courtyard walls and building roofs, according to the study. They claimed that although these components weren’t necessary, locals created them to achieve privacy and address the spatial order of the various components of the dwelling ().Footnote2 Therefore, the study highlighted how various elements were implemented by inhabitants to improve privacy, as the walls increased the height of a property, and the building roofs created an additional layer between neighbors. This was especially true for female occupants, as the extra privacy meant that they could enjoy more open-air activities, such as hosting social gatherings in the courtyard or spending time outside. Through observation, it was found that these elements were able to be implemented after addressing the spatial order of the dwelling components; thus, the order provided improved safety and security for both male and female occupants.

Al-Mohannadi studied the courtyard in Qatar’s traditional built environment and claimed that it “physically” and “socially” resembled the housing unit’s nucleus. The researcher observed that the spatial inner layout of the Qatari house is influenced by the hospitality factor, reflecting the social divisions of family members and their deeply embedded way of life in Arab culture (Al-Mohannadi Citation2019). According to Bekleyen and Dalkil, traditional Turkish courtyards are widespread in hot and arid climates and symbolize rigorous territoriality as well as attempts to provide private space for introversion (Bekleyen and Dalkil Citation2011). While both Al-Mohannadi and Bekleyen & Dalkil point to hospitality and territoriality as factors impacting the spatial form of Arab dwellings, it is also possible that these courtyards reflect an increased level of social organization and status. This idea of hospitality and the formation of private space is echoed in traditional Arab dwellings, with many believing that the traditional courtyard serves as a testament to this. Thus, both the observations of Al-Mohannadi and Bekleyen & Dalkil support the study’s findings in that there are similar trends in the formation of traditional courtyards in such regions as Qatar and Turkey.

The courtyard, in addition to serving a vital function in managing the spatial order of inner spaces, offers a layer of depth to regulate accessibility (Alnaim Citation2020b). This is consistent with what was described earlier: locals positioned the courtyard in the center of the house to regulate the use of other interior spaces. As a result, women who frequent the courtyard and spend the day inside have a very clear view of all of the other private places in the home from this one location. Although it cannot be said that this was the only motivation for the courtyard, it can be said that this was one of its primary objectives. By being able to see who was coming and going in the household, women could have a greater sense of autonomy, control, and privacy.Footnote3 Thus, the courtyard created an ideal balance between privacy and visibility that allowed women to protect themselves while being able to move freely throughout the home.

4.3. The courtyard’s relationships

In order to understand how a particular courtyard interacts with other indoor areas in the home in terms of connectedness and visual disengagement, it was important to look at individual courtyards. The closeness of the Najdi towns affected the development of some components to guarantee the fulfillment of particular requirements connected to neighborly seclusion. Because of this, it was previously considered that certain courtyard features were created by locals to meet specific needs. It is worth noting that it has been found that many of the components found in Najdi courtyards are found in other courtyard designs throughout the world (Al-Hussayen Citation2015; Baiz and Fathulla Citation2016; Gupta and Joshi Citation2021; Markus Citation2016). Although these similarities have been observed, it is still possible that the closeness of the towns and their cultural proximity to one another played a role in the development of similar courtyard features.

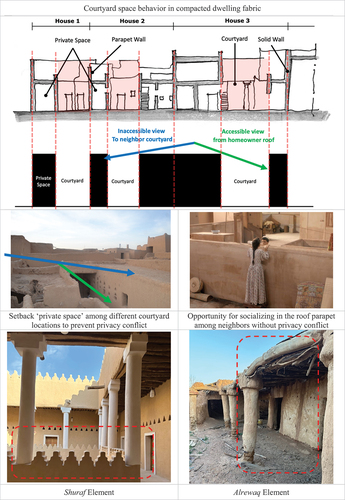

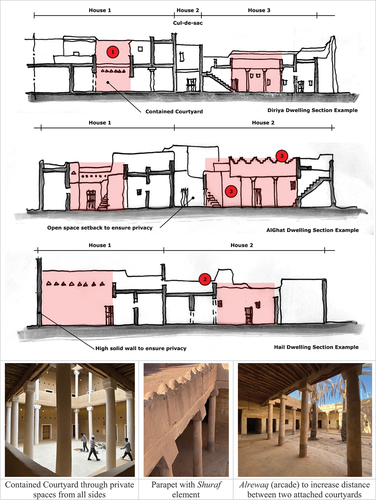

The study attempted to assess surrounding courtyards in neighboring houses using architectural section views in order to determine what sorts of architectural components and spaces are related within the house in order to maintain the courtyard’s isolation and inner spaces in general. The investigation examined two or three adjoining houses to see what features of the house physical form guaranteed that each courtyard was isolated from its neighbors. Also, the study analyzed the existence of several architectural components and their socio-cultural role in maintaining house privacy.

Three elements struck out when studying the courtyard through the section view: the roof walls (parapet), the high walls, and the variety of shapes connecting to inner rooms comprising the courtyard space (). To maintain solitude, each component within the house has a specific position and purpose. This observation is related to Ali Bahamman’s explanation of Saudi Arabian home architectural plans for privacy. The courtyard, according to Bahamman, is more than simply a climatic and cost-effective architectural solution; it is also an architectural device for producing isolation and a pleasant semi-outdoor extension of the home (Bahammam Citation1987). For decades, the concept of utilizing architecture to control privacy has been an important aspect of Saudi culture.

For instance, it is noticed that tall walls in the courtyard serve to obscure views of rooms on the roofs of the buildings, as well as roof parapets among two nearby residences that serve a similar objective. The roof parapet is used to mark the boundaries of a house’s roof. The parapet can be tall to provide more seclusion or short to offer visibility across bordering roofs, allowing women living next door to speak and socialize with their neighbors. Roof parapets and high walls function as cohesive components since they both heighten the physical enclosure of the courtyard. On the other hand, private rooms and their exterior walls are used to fence the courtyard by expanding the depth among to bordering house roofs, incorporating architectural features (e.g., a roof parapet, called shuraf), or positioning them such that the view is restricted or increased (e.g., (an arcade, called alrewaq)).Footnote4 All of these components developed to play a role in shaping the social experience and physical environment in which women interact with each other.

As previously discussed, the courtyard is positioned in the center of the house. However, some houses may be unable to situate their courtyards between private space owing to space constraints (for example, the house’s plot size). In this approach, courtyard-related features produced to enhance the effect of privacy and to get around the inevitable circumstances. For instance, the houses in AlGhat and Hail have this inescapable circumstance. The home’s courtyard is in the middle of the structure, but with no private spaces, and it is attached to a neighbor’s home. To ensure that the courtyard and roof of these homes were never exposed to the second house, the first house had to implement a number of architectural features presented earlier.Footnote5 These components, even though they have aesthetic features, have as their main objective to improve the seclusion of each house and safeguard the courtyards of both neighbors, which had an impact on the privacy of attached homes. As a consequence, inhabitants developed and implemented these components not just to benefit the courtyard specifically, but also as architectural components that establish an interaction with nearby buildings. This connection process shaped the physical form of the house and influenced the building masses of surrounding homes.

As seen in (), the Najdi built form’s compactness strengthened the physical form’s homogeneity. Even if there are two to three compacted houses visible in the architectural section views, their land borders are still unclear, and they are physically indistinguishable. This is significant because the argument makes the point that these three architectural components are not intended to separate different houses but rather to protect the privacy of inhabitants and improve the compactness and connectivity of various physical forms. As a result, female inhabitants can interact more closely and more efficiently, even though the Najdi house’s characteristics are meant to provide them with high privacy space.

In fact, this is the result of the spatial order developed by inhabitants that led the Najdi built environment to build cohesive urban masses that allowed for household separation and joining based on religious principles (e.g., the Islamic principles of “neighbors” rights’ and “easement rights” (see Al-Hathloul Citation2010) and the Islamic principle of “do no harm” (see Alnaim Citation2021)). The significance of the developed spatial order is to give the female inhabitants the ability to create a strong sense of community and interaction. Therefore, any new components produced by locals were derived from the spatial order, which aimed to preserve the built environment’s uniformity and meet socio-cultural demands.

4.4. The courtyard’s environmental aspects

In hot, dry countries like Saudi Arabia, the requirement for sustainable building design solutions that improve climatic conditions is critical. As previously noted, courtyards have long been an important aspect of vernacular design in such conditions, bringing several environmental and social benefits. Consequently, courtyard spaces have long been incorporated into traditional building methods in this region as a means of moderating the harsh environmental conditions, giving residents with a comfortable microclimate and a variety of social and psychological benefits (Rashid and Ara Citation2020).

One of the key advantages of courtyard spaces is their capacity to improve building thermal efficiency, decreasing the demand for mechanical cooling systems and, as a result, cutting energy consumption. Courtyard spaces achieved this through a variety of methods, including shading, ventilation, thermal mass, and evaporative cooling, as demonstrated and observed in three study cases ().

Table 1. Summary of significant design method related to courtyard environmental factors.

As we have showcased earlier, the placement and layout of a courtyard play a crucial role in optimizing its passive cooling potential. That is why we noticed that adjacent courtyards are rarely observed as this due to design principle to minimize direct solar exposure and maximize natural ventilation through having the courtyard contained between inner private structures (: A).

Table 2. Summary of the Najdi courtyard environmental design principles.

Even though the courtyard should be oriented to face the prevailing winds, which promotes air movement and enhances natural ventilation. Not all Najdi dwellings have this capability due to the compacted urban form and high restriction on privacy issues. Therefore, inner private structures contain and surround the courtyard and to be arranged in a staggered manner, with openings carefully positioned to create a wind tunnel effect, thus increasing air movement through the space (: B). Such a solution is developed to overcome the several socio-cultural constraints deployed on how dwellings are shaped and positioned.

While examining the courtyard spaces in Riyadh, Faisal Mubarak (Citation2007) asserts that the size and proportion of the courtyard have a significant impact on the space passive cooling performance. He concluded that larger courtyard allows for more air movement and better ventilation, while a smaller courtyard can trap heat and become uncomfortable. Observing the study cases, it is found that the courtyard space proportion always depends on the size of dwelling, which means that locals understood this principle and tried to accommodate the courtyard in their dwellings to reach maximum efficiency (: C). However, to reach the optimum size of a courtyard depends on various factors, and not always feasible including the surrounding buildings’ height, and the occupants’ needs. In general, we could say that the three cases had their courtyard’s width between one to two times the height of the surrounding walls to balance shade provision and air movement.

Overall, courtyard spaces have played a significant role in providing thermal comfort and enhancing the quality of life in Najdi residents. The architectural features of these spaces, such as their orientation, layout, and materials, contribute to their passive cooling benefits by promoting natural ventilation, reducing heat gain, and maintaining comfortable indoor temperatures. By better understanding these features and strategies, architects and urban planners can incorporate courtyards into modern building design to create more sustainable and energy-efficient environments in hot dry climates.

5. Discussion

Najdi architecture is a type of traditional Saudi Arabian architecture that developed in the Najd region of the Arabian Peninsula. This style is characterized by its use of the courtyard space, which was used to create intimate and cool spaces in the hot desert climate. The traditional compact planning system contributed to enhancing the productivity of the Najdi dwelling by covering two sides of the residential unit to provide privacy organically and contributed to accommodating and adapting the backyard in a way that does not greatly infringe upon the privacy of the adjacent neighbors. As for the courtyard, other openings and windows open towards it is mostly from the family one. The courtyard space contributed to raising the efficiency of the thermal performance of the residential unit due to the desire for the natural cooling process resulting from protection/isolation from direct sunlight. Protection from direct sunlight in hot areas is a design principle enabled by adopting a compact solution as well as isolation. Isolation is accomplished by increasing the distance between two courtyard spaces through having an arcade element within the house. Such design principles contributed to creating an opportunity for the application of ventilation openings overlooking the inner courtyard, an important tool for the provision of natural ventilation and direct cooling to other rooms of the dwelling without breaching privacy requirements.

As we have showcased in this study, courtyard spaces have played a significant role in the social and cultural life of communities. They served as a nexus for social interaction, community identity, and cultural expression. The space became a common space for residents to interact with one another. This interaction took various forms, such as communal meals, or shared activities like informal gatherings. The courtyard thus becomes a focal point for social life, fostering a sense of community and belonging among its users.

The shared nature of courtyard spaces was identified to encourage cooperation and collaboration among community members. This is evident in the collaborative design processes that encouraged the organization of courtyard-based events and activities, which influenced how to implement and place the courtyard space in the traditional dwelling. As a result, the courtyard served as a platform for community building and social bonding. Therefore, understanding the social and cultural implications of these spaces can provide insights into the importance of preserving and reintegrating courtyard design into modern architecture.

The traditional courtyard generally adheres to four key criteria that guarantee user privacy and affect the spatial arrangement of the home. First, residents always moved the courtyard back and entered it through the threshold area, adding depth to the home’s entry. Second, to assure solitude from all sides and to be surrounded by private interior spaces, the courtyard is situated in the center of the house or on one of its sides. Third, the study observed that, in most cases, if the house only has one floor, the outer partition walls are located above eye level on the roof to safeguard the interruption of visual corridors among neighbors’ while on the roof. Fourth, it is important to avoid placing two courtyards from different houses next to one another. Instead, inhabitants of traditional settlements created a barrier between the two courtyards by adding courtyard components or interior private spaces. These guidelines ensured that the cultural setting of the inhabitants of traditional settlements was preserved, governing the use of the courtyard in such a context, and established an agreed upon arrangement of the dwelling inner spaces’ spatial order. As a result, by understanding these courtyard design guidelines used by traditional settlement inhabitants, it is possible to create spaces in new developments that not only ensure privacy, but also promote social interaction between neighbors. It is also important to consider the contextual information of a particular location when designing courtyards.

Therefore, () presents the typological and socio-cultural of the courtyard space in traditional Najdi architecture is based on a number of aspects, including:

Table 3. Summary of the study typological and socio-cultural aspects of the Najdi courtyard.

It is recommended that in order to develop the Najdi courtyard home in contemporary architecture in Saudi Arabia, it is necessary to use new materials and technology while retaining the influence of the traditional building’s basic shape and character. The Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs (MMRA) enacted a partial building control regarding the home size and plot, which unquestionably have affected the shape of the residential fabric and limited the possibility of implementing courtyard spaces as a result of setback policies between neighbors. Therefore, the use of concrete and steel can offer a structural underpinning for the construction of new extensions and additions while retaining the home’s original features. Additionally, shading strategies should be carefully considered and further developed to ensure an environmentally friendly and cost-effective way to cool the dwelling. This ensures that modern dwellings meet current comfort and energy efficiency standards while retaining the traditional appearance.

Incorporating basic tools and natural components into the design process enables a courtyard space in contemporary homes to be achieved while preserving traditional concepts. Using an open-air courtyard instead of an enclosed one, for instance, provides much-needed natural ventilation and a sense of connection with nature in the living areas. In addition, wood, stone, and even clay can be utilized to produce a classic appearance and feel. These materials should also be supplemented with plants and foliage to create an ambiance characteristic of a traditional courtyard. By designing a place that is both aesthetically pleasing and functional, homeowners may enjoy their courtyard without compromising privacy.

6. Conclusion

In addition to its architectural merit, the traditional courtyard dwelling formation is an efficient way of combining indoor living space with outdoor access while providing privacy and protection from outside elements. It also allows for a communal area where family members can spend time together or entertain guests while taking advantage of natural ventilation and light that would otherwise be difficult to achieve in more traditional building types. This is particularly significant in cultures where family privacy is strongly valued, as it is in Saudi Arabia. Although this study highlights the rectangular and square shapes of the courtyard, alternative formations such as the U and L shape may emerge on rare occasions to overcome constraints such as site restrictions, building orientation, building size or to facilitate certain functions within the dwelling. However, it has become clear that courtyards in the Najdi region are a form of vernacular architecture that follows a certain set of regulating principles and socio-cultural standard features, despite slight variations due to local customs or context. The study’s results demonstrate that, no matter where the courtyard was located, many of the same architectural features were used to keep the inside and outside worlds separate. Regardless of the configuration, the main goal was to keep the family’s privacy contained, which resulted in the overall shape of the traditional Najdi dwelling’s characteristics.

Building new residences is understandably one of the most apparent approaches to demonstrate modernization today. Only recently have Saudis begun to ask whether these recently constructed residences should be so Westernized, and, more crucially, how contemporary architecture might retain the subtle characteristics of the old mud houses they left behind. Understanding the importance of courtyards in architecture in the Saudi context or in other places around the world can provide insights into how such a space can be used to create meaningful transitions between public and private areas in the modern era. Architects can use this cultural knowledge to create modern courtyards that are both aesthetically pleasing and socially meaningful. Therefore, we must ask: can new architectural projects absorb traditional ideas? Does the literal transfer of traditional ideas express originality and local identity in modern projects? A question to be answered for future studies is how understanding the embedded meanings of several traditional concepts may enhance the quality of local architectural identity.

Date Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the study settlements who were willing to be interviewed and observe their houses to inform this paper. We also appreciate individuals for their help in conducting the field research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mohammed Mashary Alnaim

Mohammed Mashary Alnaim, Architect and academic (assistant professor) of engineering at the University of Hail. Architectural/cultural heritage and social studies are areas of expertise. Holds a Ph.D. in Design and Planning from the University of Colorado at Denver, focusing on vernacular architecture & sociocultural theories and practices with a minor focus on urban morphology. The topics of research include cultural heritage, urban morphology, vernacular studies, sociocultural studies, and urban design. As a practitioner, I worked in several roles, including designer, data analyst, design & technical reviewer, documentation & report writer, QA (quality assurance) & QC (quality control), and lead consultant on various projects. With theoretical knowledge and practical experience in hand, I am able to provide more robust best practices and strategies in the academic and professional fields.

Notes

1 In Najdi architecture, the courtyard is used for Eid festivities, weddings, family gatherings, playground activities, etc. Traditional courtyards derive their significance from facilitating private social activities and serving as a hub for the family.

2 Focus groups were held in Hail and AlGhat between 2021 and 2022.

3 Focus groups were held in Hail, Diriya between 2021 and 2022.

4 An interview with Hail’s elderly community between 2021 and 2022.

5 Focus groups were held in Hail and AlGhat between 2021 and 2022.

References

- Abdulkareem, H. A. 2016. “Thermal Comfort Through the Microclimates of the Courtyard. A Critical Review of the Middle-Eastern Courtyard House as a Climatic Response.” Procedia-Social & Behavioral Sciences 216:662–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.12.054.

- Ahmadi, S., and M. Habibi. 2023. “Concept of Dwelling in Informal Settlements Located in Metropolitan Areas of Iran Case Study: Morteza Gerd.” Morteza Gerd GeoJournal 88 (2): 2083–2100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-022-10735-z.

- Akbar, J. 1982. Courtyard Houses: A Case Study from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia’. The Arab City: Its Character and Islamic Cultural Heritage, Proceedings of a Symposium. KSA: Madina, pp. 162–176.

- Akbar, J. 1998. Crisis in the Built Environment: The Case of the Muslim City. Netherlands: Concept Media Pte Ltd, A Mimar Book.

- Al-Hafith, B., K. Satish, S. Bradbury, and P. De Wilde. 2017. “The Impact of Courtyard Compact Urban Fabric on Its Shading: Case Study of Mosul City, Iraq.” Energy Procedia 122:889–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.07.382.

- Al-Hathloul, S. 2010. Arabic Islamic Cities: The Effect of Legislation in Shaping the Urban Environment. Umran, Riyadh: Saudi Arabia (Arabic).

- Al-Hussayen, A. 1996. Women and the Built Environment of Najd. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- Al-Hussayen, M. 2015. “Significant Characteristics and Design Considerations of the Courtyard House.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 12 (3): 240–258.

- Al-Mohannadi, A. 2019. Socio-Cultural Factors Shaping the Spatial Form of Traditional and Contemporary Housing in Qatar: A Comparative Analysis Based on Space Syntax. Academia, Proceedings of the 12th Space Syntax Symposium, Beijing, China, 285, pp. 1–19.

- Alnaim, M. 2006. The Home Environment in Saudi Arabia and Gulf State: Growth of Identity Crises and Origin of Identity. Milano: Crissma.

- Alnaim, M. M. 2020a. “The Concept of Access and the Mechanisms of the Threshold Space in Arab Traditional Built Environment: The Case of Najd, Saudi Arabia.” Global Journal of Science Frontier Research 20 (A9): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.34257/GJSFRAVOL20IS9PG1.

- Alnaim, M. M. 2020b. “The Hierarchical Order of Spaces in Arab Traditional Towns: The Case of Najd, Saudi Arabia.” World Journal of Engineering and Technology 8 (3): 347–366. https://doi.org/10.4236/wjet.2020.83027.

- Alnaim, M. M. 2021. “Dwelling Form and Culture in the Traditional Najdi Built Environment, Saudi Arabia.” Open House International 46 (4): 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1108/OHI-01-2021-0015.

- Alnaim, M. M., G. Albaqawy, M. Bay, and A. Mesloub. 2023. “The Impact of Generative Principles on the Traditional Islamic Built Environment: The Context of the Saudi Arabian Built Environment.” Ain Shams Engineering Journal 14 (4): 101914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2022.101914.

- Bafna, S. 2003. “Space Syntax: A Brief Introduction to Its Logic and Analytical Techniques.” Environment & Behavior 35 (1): 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916502238.

- Bagasi, A. A., and J. K. Calautit. 2020. “Experimental Field Study of the Integration of Passive and Evaporative Cooling Techniques with Mashrabiya in Hot Climates.” Energy and Buildings 225:110325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110325.

- Bahammam, A. 1987. Architectural Patterns of Privacy in Saudi Arabian Housing. Unpublished PhD Thesis, McGill University, Montreal: USA.

- Baiz, W., and S. Fathulla. 2016. “Urban Courtyard Housing Form as a Response to Human Need, Culture and Environment in Hot Climate Regions: Baghdad as a Case Study.” International Journal of Engineering Research and Applications 6 (9): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.9790/9622-0609011019.

- Bekleyen, A., and N. Dalkil. 2011. “The Influence of Climate and Privacy on Indigenous Courtyard Houses in Diyarbakır, Turkey.” Scientific Research and Essays 6 (4): 908–922.

- Bourdier, J. P., and N. Alsayyad. 1989. Dwellings, Settlements: Cross-cultural Perspectives, 5–25. New York: University Press of America.

- Ciesielska, M., K. W. Boström, and M. Öhlander. 2018. Qualitative Methodologies in Organization Studies Methods and Possibilities. Vol. 2, 33–52. London: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65442-3_2.

- Curran, J. 2012. Ethnography Design. London: Royal College of Art.

- Das, N. (2006). Courtyards houses of Kolkata: Bioclimatic, typological and socio-cultural study (Doctoral dissertation, Kansas State University).

- Diz-Mellado, E., V. P. López-Cabeza, C. Rivera-Gómez, C. Galán-Marín, J. Rojas-Fernández, and M. Nikolopoulou. 2021. “Extending the Adaptive Thermal Comfort Models for Courtyards.” Building and Environment 203:108094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108094.

- Edwards, B., M. Sibley, M. Hakmi, and P. Land. 2006. Courtyard Housing: Past, Present and Future. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Elizondo, L. 2022. “A Justified Plan Graph Analysis of Social Housing in Mexico (1974–2019): Spatial Transformations and Social Implications.” Nexus Network Journal 24 (1): 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-021-00568-7.

- El-Shorbagy, A. 2010. “Traditional Islamic-Arab House: Vocabulary and Syntax.” International Journal of Civil and Environmental Engineering 10 (4): 15–20.

- Erarslan, A. 2020. “The Concept of Regionalism in Architecture as Interpreted in Contemporary Architecture: The Element of the “Courtyard“ in the Architecture of Turgut Cansever and Cengiz Bektaş. Contemporary Studies in Sciences, edited by Efe Recep, and Cürebal, Isa, 196–222. UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Flynn, P. 2010. Ethnographic approaches. In Handbook of Translation Studies, Gambier Yves, and Doorslaer, Luc van. Vol. 1, 116–119. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Foth, M., and J. Tacchi. 2004. “Ethnographic Action Research Website.” In Profiles and Experiences in ICT Innovation for Poverty Reduction, edited by I. Pringle and S. Subramanian, 27–32. New Delhi: UNESCO.

- Gupta, R., and M. Joshi. 2021. “Courtyard: A Look at the Relevance of Courtyard Space in Contemporary Houses.” Civil Engineering and Architecture 9 (7): 2261–2272. https://doi.org/10.13189/cea.2021.090713.

- Hakim, B. S. 1986. Arabic-Islamic Cities: Building and Planning Principles. London, UK: Kegan Paul International.

- Hillier, B., and J. Hanson. 1988. The Social Logic of Space. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hillier, B., A. Leaman, P. Stansall, and M. Bedford. 1976. “Space Syntax.” Environment & Planning. B, Planning & Design 3 (2): 147–185. https://doi.org/10.1068/b0301.

- Husin, Z. 2016. “The Role of Domestic Courtyard in Islamic Teachings and Practices: Oman as a Case Study.” Journal of Education & Social Sciences 4 (June): 225–234.

- Izadpanahi, P., L. M. Farahani, and R. Nikpey. 2021. “Lessons from Sustainable and Vernacular Passive Cooling Strategies Used in Traditional Iranian Houses.” Journal of Sustainable Tropical Agricultural Research 3 (3) 1–23.

- Lawrence, R. J. 1987. Housing, Dwellings and Homes: Design Theory, Research and Practice. London: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Lee, M. S., and Y. Park. 2015. “The Courtyard as a Microcosm of Everyday Life and Social Interaction.” Architectural Research 17 (2): 65–74. https://doi.org/10.5659/AIKAR.2015.17.2.65.

- Markus, B. 2016. “Review of Courtyard House in Nigeria: Definitions, History, Evolution, Typology, and Functions.” AFRREV STECH: An International Journal of Science and Technology 5 (2): 103–117. https://doi.org/10.4314/stech.v5i2.8.

- Memarian, G., and F. E. Brown. 2003. “Climate, Culture, and Religion: Aspects of the Traditional Courtyard House in Iran.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 20 (3): 181–198.

- Mortada, H. 2016. “Sustainable Desert Traditional Architecture of the Central Region of Saudi Arabia.” Sustainable Development 24 (6): 383–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1634.

- Mubarak, F. A., King, P.D. 2007. Cultural Adaptation to Housing Needs: A Case Study, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. In IAHS Conference Proceedings, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 1–7.

- Mustafa, F. A., A. S. Hassan, and S. Y. Baper. 2010. “Using Space Syntax Analysis in Detecting Privacy: A Comparative Study of Traditional and Modern House Layouts in Erbil City, Iraq.” Asian Social Science 6 (8): 157. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v6n8p157.

- Nelson, R. 2014. “The Courtyard Inside and Out: A Brief History of an Architectural Ambiguity.” Enquiry the ARCC Journal for Architectural Research 11 (1): 10–10. https://doi.org/10.17831/enq:arcc.v11i1.206.

- Noble, A. G. 2007. Traditional Buildings: A Global Survey of Structural Forms and Cultural Functions. London: I.B.Tauris. https://doi.org/10.5040/9780755604166.

- Nurani, L. M. 2008. “Critical Review of Ethnographic Approach.” Journal Socioecology 7 (14): 441–447.

- Oliver, P. 1989. Dwellings Settlements and Tradition: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Handed Down Architecture, eds. Bourdier, J. P. and Alsayyad, N, 54–75. New York: University Press of America.

- Ostwald, M. 2011. “A Justified Plan Graph Analysis of the Early Houses (1975-1982) of Glenn Murcutt.” Nexus Network Journal 13 (3): 737–762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-011-0089-x.

- Paul Oliver. 2007. Dwellings: The Vernacular House Worldwide. Incorporated, USA: Phaidon Press.

- Rabbat, N. 2010. The Courtyard House: From Cultural Reference to Universal Relevance. London: Routledge.

- Ragette, F. 2012. Traditional Domestic Architecture of the Arab Region, 296. UAE: Edition Axel Menges.

- Raof, B. Y. 2018. “Developing Vernacular Passive Cooling Strategies in (Kurdistan-Iraq).” International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research 7 (3): 13–20.

- Rapaport, A. 2007. “The Nature of the Courtyard House: A Conceptual Analysis.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 18 (2): 57–71.

- Rapoport, A. 1969. House Form and Culture. Englewood Cliffs, London: Prentice Hall, Inc.

- Rashid, M., and D. Ara. 2020. Building in Hot and Humid Regions: Historical Perspective and Technological Advances. In Building in Hot and Humid Regions, edited by Napoleon Enteria, Awbi Awbi, and Santamouris, Mat, 137–150. London, UK: Spring.

- Soflaei, F., M. Shokouhian, and S. M. M. Shemirani. 2016. “Investigation of Iranian Traditional Courtyard as Passive Cooling Strategy (A Field Study on BS Climate).” International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment 5 (1): 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsbe.2015.12.001.

- Sthapak, S., and A. Bandyopadhyay. 2014. “Courtyard Houses: An Overview.” Recent Research in Science and Technology 6 (1): 70–73.

- Taleghani, M., M. Tenpierik, and A. van den Dobbelsteen. 1986. “Environmental Impact of Courtyards—A Review and Comparison of Residential Courtyard Buildings in Different Climates.” Journal of Green Building 7 (2): 113–136. https://doi.org/10.3992/jgb.7.2.113.

- Turner, A., M. Doxa, D. O’Sullivan, and A. Penn. 2001. “From Isovists to Visibility Graphs: A Methodology for the Analysis of Architectural Space.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 28 (1): 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1068/b2684.

- UNESCO. (2001). Intangible Cultural Heritage – Working Definitions. International Round Table, Piedmont: Italy, Retrieved from: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/00075-EN.pdf. on January 28, 2023

- Urquhart, C. 2015. “Observation Research Techniques.” Journal of EAHIL 11 (3): 29–31.

- Wimpenny, P., and J. Gass. 2000. “Interviewing in Phenomenology and Grounded Theory: Is There a Difference?” Journal of Advanced Nursing 31 (6): 1485–1492. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01431.x.

- Zamani, Z., S. Heidari, and P. Hanachi. 2018. “Reviewing the Thermal and Microclimatic Function of Courtyards.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 93:580–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.05.055.

- Zhang, D. 2020. Courtyard Houses around the World: A Cross-Cultural Analysis and Contemporary Relevance. In New Approaches in Contemporary Architecture and Urbanism,edited by Nia Hourakhsh, 23–44. İstanbul, Turkey: Cinius Yayinlari Publication.