ABSTRACT

Rapid urbanization during the past decades have turned southeastern coastal China from traditional brick settlements into concrete forests. However, studies in Putian Plain reveal that apart from the physical appearances, local popular religion welcomed repercussions in these decades, even during the pandemic years. This paper looks at contemporary ritual practices and points out how social, cultural and ecological system of a unique ritual alliance system (Qijing) actives. Through practicing a ritualized everyday life, local communities managed to maintain certain indolence in different political and economic circumstances and achieve cultural resilience through various challenges brought by urbanization.

1. Introduction

With the emergences of climate change, the economic crisis and pandemics, the responsiveness of social space systems has attracted more attention (Hill, Wial, and Wolman Citation2008), and China’s appeal for social and cultural resilience is growing (Xu, Zhao, and Wen Citation2017; Zhai et al. Citation2018). In particular, the pandemic years (2020–2022) highlighted such a declaration in China, and people began to pay more attention to the enlightenment of the resilience of traditional culture on modern life (Zhai and Xia Citation2021; Zhai et al. Citation2022).

In the context of rapid urbanization, traditional village culture in China are generally facing the threat of extinction (Long et al. Citation2016; Zhang and Wu Citation2015). Advocates calling for respect and protection of traditional villages are growing (Ruan, Shao, and Lin Citation2002; Verdini, Frassoldati, and Nolf Citation2016; Ye and Liu Citation2020). The historical spatial form and evolution of traditional villages are widely valued (Yang et al. Citation2018; Zhang, He, and Deng Citation2020). However, research shows that the space of traditional villages evolves with changes in political, economic and social factors (Hu et al. Citation2019; Saleh Citation2001). This shift means that the study of traditional villages can no longer be conducted with a single linear disciplinary thinking, and more attention should be given to the application of multidisciplinary and new methods (Zhang, Chen, and Zhou Citation2017), from the material level to the inner layer of culture, from “objects” to “people” (Xu Citation2003), and from architecture to anthropology, history, geography and other multidisciplinary thinking (Xiong Citation2017). The tradition of “one” village makes it difficult to summarize regional or Chinese cultural characteristics, which not only ignores the traditional links between villages but also treats local traditions in isolation at the spatial level. The study of settlements has also changed from a single village to a regional study (Xu, Wen, and Liu Citation2020). Recent years, the idea of “cultural resilience” was brought up to discuss how communities can deal with and overcome adversities and growing risks (Clauss-Ehlers Citation2010; Holtorf Citation2018).

Current studies have analyzed the evolution characteristics of traditional settlements from the macro level of regional integration and have also analyzed the evolution of settlements from the micro level of villages. Therefore, it is necessary to connect the individual village with the whole region historically from the perspective of anthropology and history and analyze the traditional regional culture from the perspective of dynamic change. The development of traditional villages is the result of the interaction of regional material culture, spiritual culture and environment. Taking the Nanyang Plain area in Putian, Fujian Province, China as an example, this paper analyzes the evolution and connection of the settlement space in the Nanyang Plain region from the perspective of anthropology and history by consulting ancient codes and records, ethnography and other research materials and conducts a specific field survey of one of the settlements, points out the persistence of local traditions, reveals the resilience of traditional cultural flexibility to modern rapid urbanization, and guides and inspires the research and development of traditional villages.

2. Study area and methodology

2.1. Study area

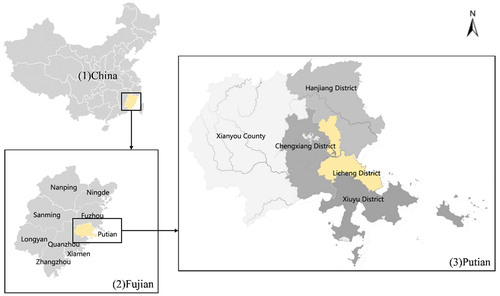

The irrigated Putian Plain in southeast China covers an area of approximately 464 square kilometers. It is situated along Xinghua Bay to the east of Putian city (). It could be seen as reclaimed land organized alongside the irrigation system. Putian is one of the smallest city administrations in Fujian; it has the most active and creative cultural tradition and the largest overseas migrations. Once seashores, the Putian plain was shaped by Mulan Creek for over a thousand years and correspondently formed impressive views of traditional settlements, spectacular architectural styles, and active ritual traditions. There are over thousands of temples dispersed in the Putian Plain worshipping hundreds of different local gods. Some gods migrated from other regions, but most of them came from local historical celebrities.

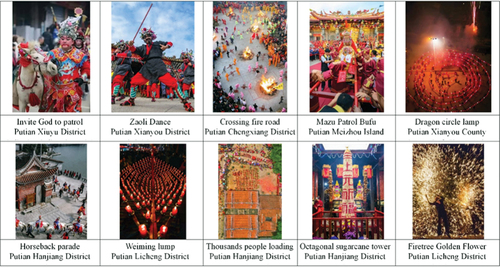

The local tradition in the Putian Plain was never fully disrupted during the past centuries, not even during the Cultural Revolution in 1960s-70s. In particular, in cities and towns, China has experienced political control, rapid economic transformation, and secularization since the 1950s. Due to strict official policies regarding religious activity, most previously temples and ritual activities closed or museumified. However, the situation was very different in rural areas. Village temples in various China practice mix and secular religious life, usually known as “popular religion” (Feuchtwang Citation2001), which is not included in the five officially recognized religions of China (Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism). Many village temples survived by being transformed into other functional buildings, such as schools, barns or even venues for political events. After the 1980s, with economic development across the country, a massive resurgence and reinvention of local ritual traditions took place (). Thousands of temples rebuilt, local ritual traditions restored or even constantly reinvented accommodation to contemporary political discourse and villagers’ everyday life.

2.2. Data sources

The historical data of the Putian Plain were obtained from the Chongkan Xinghua fuzhi (Zhou & Huang, Citation2007) and Putian Xianzhi (PTXDFZBZWYH Citation1994) and research on Dean and Zheng in the 1990s-2010s regarding the population, principal lineages, temples and ritual celebrations (Dean and Zheng Citation2009a, Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Zheng Citation1989, Citation1995). The dates of the large-scale investigation related to folk belief activities were mainly from the research report of the Fujian Provincial Department of Ethnic and Religious Affairs (Fan and Lin Citation2002; FPDERA Citation2002; Xi Citation2008). The interpretation of Putian historical political system were obtained from Historians and Anthropologists’ Research on the Political System of the Ming and Qing Dynasties (Du Citation2016,; Tong Citation2019; Zhang Citation1974; Zheng Citation1989). The historical records of water conservancy in Putian are derived from the Putian Water Conservancy Annals and related research (Cheng Citation1875; He Citation2019). The current status of temples and the environmental elements, Fangming Stele (Stele with the fragrant names of those who made gifts on the occasion of the god’s birthday at the Temple that Surmounts the Clouds), Hongbang Xiwen (issue proclamations), and other current information of Jindun QiJing was obtained through the field work of the authors.

2.3. Research methodology

Regional studies on Chinese Han settlements mainly include the theory of clans (Ebrey and Watson Citation1987; Freedman Citation1958, Citation1979, Citation2004), which regards clans as the cornerstone of Chinese (Fujian and Guangdong) society; the marketing system (Skinner Citation1964), which regards rural fairs as a way to understand the distribution of Chinese settlements and the living space of residents; the magnetic attraction theory, which emphasizes cultural differences from the “cultural Qiqu” phenomenon (Crissman Citation1972); and the theory of sacrificial circles from the perspective of folk beliefs and festival rituals (Yuzuru Citation1938).

In view of the frequent and active festival rituals in Putian, this study adopts the theory of sacrificial circles as a method to analyze the distribution and composition of Putian Nanyang Plain settlements. The theory of sacrificial circle first appeared in the ethnological study of Han people in Taiwan. Japanese scholar Okada Qian initially studied Han people in Shilin Street, Taipei State, and found that the distribution of Han people’s families or relatives, as well as the scope of marriage, had something in common with their scope of sacrificial activities. In 1938, he published a paper, “Sacrificial Circle of Villages in Northern Taiwan” (Yuzuru Citation1938). For 40 years, the theory and method of the sacrificial circle have not been considered by the Taiwanese academic community. Research on the Han sacrificial circle by Taiwanese native scholars began in the 1970s, when Li Yiyuan and Wang Songxing conducted field trips to Quanzhou Cuo, Shengang Township, Changhua County, and the Han communities on Guishan Island. In 1970, the “Comprehensive Scientific Research Plan for the Turbid Water and Dadu River Basins” (“Turbid Plan”) was implemented. Shi Zhenmin and Xu Jiaming took the Han settlements in the Changhua Plain as their main research objects. Shi Zhenmin was an early scholar in Taiwan who defined the concept of the “sacrificial circle”: “sacrificial circle is a regional organization model based on the main god and religious activities.” Xu Jiaming stated, “Sacrifice circle refers to the regional unit where believers jointly hold sacrifices with a main god as the center. Although Zhuang Yingzhang did not clearly put forward the concept of a sacrificial circle, he believed that the sacrificial circle was formed based on a natural system, water conservancy system and transportation factors. (Zhuang Citation1973) Its members are limited to the residents within the regional scope of the property under the name of the main god.” Lin Meimei has been focusing on Caotun Town for a long time and is actively committed to improving the theory and method of the “sacrificial circle”. He summarized three elements, including “main gods” (“main gods”). The common sacrifice refers to a certain geographical scope (Lin Citation1986). Zheng Zhenman continued the discussion on sacrificial circle theory in Taiwan and found through field research that the sacrificial circle was not a unique product of Taiwan’s immigrant society; at least, it still existed in the southeastern coastal areas of China. Taking the temple cult organization in the Putian Jiangkou Plain as an example, he believed that the temple cult organization in the history of the Jiangkou Plain was not only a religious organization but also a community organization, so it had a richer connotation than the sacrificial circle (Zheng Citation1995; Dean & Zheng, Citation2009a).

This study constructs a research idea from the perspective of sacrificial circle theory. On the basis of Zheng Zhenman’s research on the villages and rituals of the Putian ritual alliance, this study selects Jindun QiJing in the twelve townships of Quqiao in the Putian Nanyang Plain as the key research object. At the same time, based on the evolution process and characteristics of the architecture, streets, forms and boundaries of traditional village space, this study analyzes the formation process, spatial evolution characteristics and evolution factors of Putian Nanyang Plain settlements. This paper probes into the cultural resilience and the repercussions of tradition in urbanization.

3. Formation of the Putian Nanyang Plain Ritual Alliance

3.1. The evolution of the Putian Plain

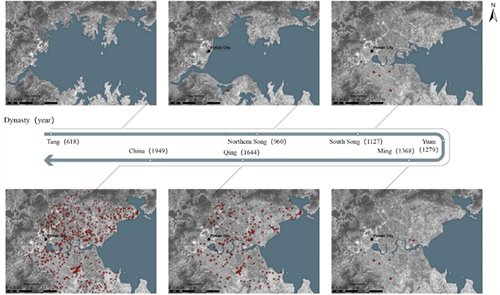

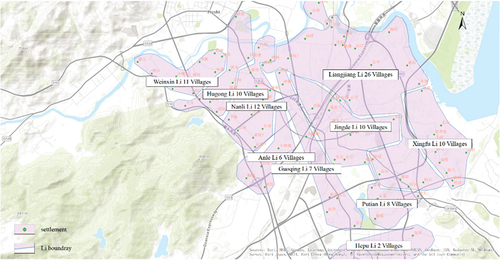

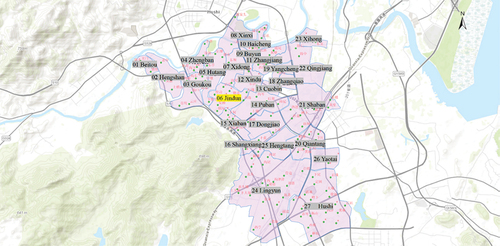

Putian Nanyang Plain refers to the Putian Plain to the south of Mulan Creek. There are more than 200,000 residents, approximately 100,000 mu (1 mu = 0.0667 hectares) of arable land, and approximately 100 administrative villages or neighborhood committees. From the late Tang Dynasty to the middle Ming Dynasty (9-16th century), the ancestors developed the Putian Plain (also known as Xinghua Plain), turning Xinghua Bay into a land of plenty and the richest place in Putian () (Dean & Zheng, Citation2010). The development of the Putian Plain requires not only reclamation and salt washing but also irrigation. Putian is close to the mountain and faces the sea. There are three streams, Mulan Creek, Yanshou Creek, and Qiulu Creek, which flow through the plain and into the sea in the east. Through the painstaking efforts of local ancestors, four weirs built on these three creeks, dug countless ditches on the plain, built large and small culvert gates along the coast and other places, solved the tailrace problem, established a perfect drainage and irrigation system, and perfectly solved the irrigation problem of the Putian Plain. Three creeks and four ponds irrigated the Putian Plain. The Putian Plain has been divided into administrative divisions since the Song Dynasty, called “Li” (). The Putian Nanyang Plain has been built from sea reclamation and water conservancy systems for generations, and local settlements have gradually grown from the foot of Hugong Mountain to Xinghua Bay. According to the local architectural age and historical records of the villages, the Putian Nanyang Plain can be divided into four cultural areas. It can be found that the closer the area is to Mulanbei, the more perfect the cultural heritage ().

3.2. The establishment of the Putian Nanyang water conservancy system

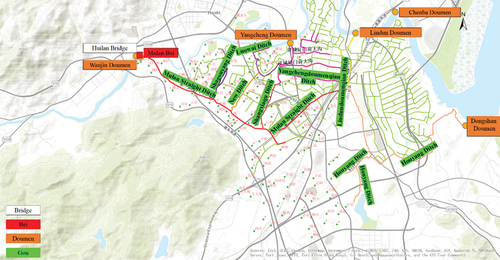

Putian Nanyang Plain is mainly irrigated by Mulan Bei (), with an irrigation area of 165,000 mu. Mulan Bei is a significant water conservancy project to remove salt water and store fresh water and a precious world heritage of irrigation projects. The Nanyang Water Conservancy System is composed of three parts of water conservancy projects, namely, Bei, Doumen, and Gou (). There are water diversion facilities at the diversion of the main ditches (Cheng Citation1875).

Bei is a dam built on a stream. The pivot of the Nanyang Water Conservancy System is the Mulanpo Water Conservancy Project, which was founded in the eighth year of Xining in the Northern Song Dynasty (in 1075). The depth of the dam is 8.3 m, and the length is 116.7 m. According to Putian Water Conservancy Annals Pond by Chen Chiyang of the Qing Dynasty (Cheng Citation1875), Mulan Bei covers 10 Li, including Putian Weixin Li, Hugong Li, Nanli Li, Guoqing Li, Anle Li, Putian Li, Jingde Li, Lianjiang Li, Xingfu Li and Hepu Li, with a total of 102 villages. Li is an ancient local administrative organization that contains several villages, probably equivalent to a modern township in ancient times. These ten li are located in Nanyang, Xinghua Plain, and belong to the four villages and towns of Huangshi, Xindu, Watshi and Beigao. In the second year of Yuan Yanyou’s reign, the Wanjin Steep Gate was opened, and Mulan Creek was combined with Yanshou Creek to irrigate Beiyang, benefiting 92 villages in Xitianwei and Wutang towns, Chengxiang District and Hanjiang District. According to Putian City Annals, Mulanbei has an irrigated area of 165,000 mu.

The Doumen is the gate for flood discharge and waterlogging drainage. In Nanyang, there are 5 sea gates, including 3 large duomen, Yangcheng Doumen in Guoqing Li, Lindun Doumen in Lianjiang Li, and Dongshan Doumen in Xingfu Li, which have the dual functions of water storage and waterlogging drainage. Two small Doumen, Wanjin Doumen and Chenba Doumen, are mainly used for drainage.

Gou is the ditch on the plain that diverts water from ponds and creeks to irrigate farmland. There are 7 large ditches and 109 small ditches in Nanyang, with a total length of 113 kilometers, which can store 17 million cubic meters of water. According to the horizontal height of these ditch systems, they can be roughly divided into upper, middle and lower sections: the upper section includes Mulan Bei Zhixiadagou and two small ditches in Weixinli, Shagou Yangdagou and four small ditches in Hukm, and New Ditch in Nanli Li; the middle section includes the Shangxiaqu Ditch and 6 small ditches, Luowai Ditch and 7 small ditches in Nanli Li, Yangcheng Doumenqian Ditch and 4 small ditches in Guoqing, and 3 small ditches in Hengtang and Xintang of Anleli; the next section includes the big ditch and 17 small ditches in front of Doumen in Yangcheng County from Guoqing Li to Putian Li, the big ditch and 9 small ditches in front of Doumen in Lintun County from Lianjiang Li, the big ditch and 38 small ditches in Houyang County, as well as 9 small ditches leading to the Wulong area in Jingdeli, 4 small ditches leading to the Nantian area in Hepuli, and 6 small ditches leading to the Doumen area in Dongshan County in Xingfuli. The large ditches mentioned above are original seaports, while the small ditches are excavated manually (Dean & Zheng, Citation2010a).

Every village in the Putian Plain is connected with a specific ditch system, dikes, Doumen and other water conservancy facilities. Each creek has its own scope of benefit. It uses ditches to form an irrigation system as dense as a spider net, covering the entire Nanyang Plain, with sufficient water supply. The distribution of water resources is related to the success or failure of reclamation. The abundance or decline of agriculture has had a direct impact on people’s lives and has been a major event since ancient times. The irrigation of the Putian Plain also has the problem of water resource allocation. The water diversion facilities are fixed and remain unchanged from generation to generation. In ancient times, different approaches were adopted to solve the problem of water distribution. There are mainly the following: 1. Water rules (establishing gates and setting the height as the standard for water discharge to irrigate the fields inside and outside the seawall); 2. Control the size of inlet culvert; 3. Discharge water by turns (He Citation2019).

3.3. Settlement alliance and Putian Nanyang ritual alliance system

Even though the Putian Plain has such a complete water conservancy system, the shortage of freshwater resources and the instability of the climate still led to many droughts and floods in Putian throughout history () (He Citation2019). It is still very common for the local people to engage in conflict due to the distribution of water. The local small villages have aligned with the surrounding villages one after another. At the same time, under the dispute of Putian’s local administration and belief ritual, a stable social relationship gradually formed during this process. Several or dozens of natural villages have combined to form different forms of regional communities. Dean and Zheng conducted a survey in the 1990s-2010s of the population, principal lineages, temples and ritual celebrations and documented 724 villages gathered into 153 ritual alliances situated on the Putian plain (Dean & Zheng, Citation2009a). Ritual Alliance refers to groups of villages that “perform regular common rituals, share a higher order village in the alliance, and organize annual (or longer temporal cycles) processions of the gods through each of the villages in the alliance”. The local term for this ritual alliance is QiJing, literally “sevenfold alliance of ritual territories”. The term Jing means a ritual unit. It could designate to a single village or more. Each ritual unit (Jing) celebrates common rituals and processions at a collectively owned and managed main temple. The ritual alliances were generally shaped from the 16th through the 18th century based on irrigation cooperation among different lineages and villages. Over the centuries, the ritual alliances took on social responsibilities such as irrigation system maintenance, local displays of power in ritual events, local infrastructure (roads, bridges, and village sanitation), charity, education, and local defense. The information of some QiJing near Hugong Mountain in the Putian Nanyang Plain is as follows ().

Table 1. Drought and flood disasters situation in Putian’s history (Cheng Citation1875; He Citation2019).

The production, life, ritual activities and management of the village are closely related to the formation of the QiJing community by building temples through common beliefs and jointly holding rituals. However, the Qijing communities will also fight with each other for water resources. For the sake of local stability and management, the Qijing communities also began to communicate and cooperate, set up a higher level General Palace, and formed a higher level ritual alliance through the joint ritual of the General Palace and mediation of disputes. The village alliance has an obvious hierarchical relationship: village—Qijing—high-level ritual alliance (). Most festival rituals are organized and operated by the unique ritual alliance system of Putian, with temples as the core. The central temple in the Nanyang Plain was originally the Xieying Temple built on the south bank of Mulanpo. It was dedicated to the worship of Elder Li, the hero of Jianpo, accompanied by Qian Siniang, Lin Congshi, and Li Di. The worship ritual was overseen by the fourteen Shuinan clans who were responsible for managing the Mulanpo water conservancy system. Later, several first-class central temples gradually formed, mainly including Xiangshan Palace in the thirteen towns of Goutou, Xiangyun Palace in the twelve towns of Quqiao, Beichen Palace and Gucheng Palace in the twenty-four Pavilions of Huangshi, Lingyun Palace in the thirty-six towns of Lingyun and Hongyun Palace in the twenty-eight towns of Watshi. Jindun Qijing, the key research object of this study, is located in the ritual alliance system of Quqiao Twelve Villages (Dean & Zheng, Citation2010b).

The rituals in Putian include village and ritual alliance celebrations held during yuanxiao (the celebration the Lantern Festival, or the full moon of the first lunar month) throughout the first month of a Chinese lunar year (CLY), and other annual communal festivals shendan (the celebration of Gods’ birthday) celebrated communally occur throughout the year. Dean and Zheng documented a total number of approximately 4,200 regularly scheduled annual ritual events, over 360 per month (). This frequency of ritual activity shows that the ritual of popular religion in the Putian Plain is an intensification of everyday life. Some villages could attend rituals over 250 days out of a year. This number does not include occasional rites or private worship that can be sponsored by individuals or communities at any time at the over 2,500 temples of the 724 villages of the Putian plains. The Yuanxiao celebration lasted through the first month of the lunar year. During the festival all the gods are celebrated together. Major villages in a Qijing celebrate closer to Yuanxiao Day (the Lantern Festival, January 15th of CLY), while smaller villages are scheduled on other days. Yuanxiao is a compulsory event. Every household should contribute to the event and have at least one male member participate in the procession (Dean & Zheng, Citation2010b). The birthdays of individual gods are celebrated in different temples throughout the year, sometimes lasting for several days. As the alliances are organized with hierarchy. Higher-order temples are called zumiao (literally, home temples). During the celebration, the gods of the home temples are borrowed by smaller temples and touring around in processions around the villages to receive worship and sacrifice from villagers.

Table 2. Annual ritual events Monthly frequency (Zhou & Huang, Citation1503; Dean & Zheng, Citation2009a).

These ritual events are organized by local communities through the leaders of village temples without involvement or interference from local governments. However, they also creatively adapt state institutions and ideas to the practices. Often involved spirit medium or spiritwriting of the god, leaders of village temples and ritual specialists constantly creating ritual practices mixed with local cults, state regulations and contemporary lifestyle. Sometimes the village temple leaders or committee members could even be retired officials who are familiar with the state policies. In a way, these temple committees could be understood as a nongovernment or even “a second government” (Dean & Zheng, Citation2009b) to local communities, which respond more rapidly and effectively to local needs than the local government. Ritual alliance is a mechanism of social cooperation that often transcends competition and conflicts and maintains social order by using the belief of gods and sacrificial rites. The ritual system is the most important social network. The identity, status, rights and obligations of all people should be defined through temples and ritual systems.

4. Analysis of the evolutionary factors of ritual alliance settlements in the Putian Nanyang Plain

4.1. Geographical factors of mountains, rivers and seas

The restriction of geographical factors is key to the evolution of Putian ritual alliance settlement. From the current geographical position of the Putian Nanyang Plain, we can see that the west is Hugong Mountain, the north is Mulan Creek, and the east is Xinghua Bay, which faces the sea. Mountains, water and the sea are the main geographical factors influencing the settlement evolution of the Putian Nanyang Plain. Hugong Mountain blocks the way for local people to expand to the west. Land from sea reclamation is an important guarantee for local people to live on. Freshwater resources are the key to crop harvest. Mulan Creek, as the only large river on Putian Nanyang Plain, feeds the entire Nanyang Plain and is the key to everything. During ancient times, land reclamation also expanded from Hugong Mountain to the east coast, and the settlements on the plain gradually developed from the upper reaches of Mulan Creek to Xinghua Bay.

4.2. The persistence of folk beliefs

In Fujian, various folk gods are mixed during ancient and modern times, including natural gods, ancestral gods, saints and sages, folk gods, etc. According to incomplete statistics, there are more than 1000 kinds. As early as 2002, Fujian Provincial CPPCC Organization and Fujian Provincial Department of Ethnic and Religious Affairs issued a survey report on Fujian folk beliefs (FPDERA Citation2002). The report of the FPDERA pointed out that almost “every village in Fujian has a temple, and there is no village without a temple”. The survey report organized by the Fujian CPPCC pointed out that there are 25,102 folk belief venues with a building area of more than 10 square meters in the province, including approximately 3000 in Putian City (FPDERA Citation2002).

Throughout history, the temples in Putian have been destroyed, and the ritual alliance in Putian still operates as a living belief system. For example, Putian in the middle of the Ming Dynasty began to launch the campaign of “destroying pornographic temples”, and the temples built by the rural settlements collectively gathering money were destroyed on a large scale. The temple worship activities carrying folk beliefs were threatened by the official. The local regional cultural elements conflict with the official system, and the bottom-up public will as well as the top-down official will confront each other. Some temples survived through “renaming”. The Hanjiang Longjin Society was changed to “Hall of Martyrs”, and the Holy Concubine Palace was changed to “Shouze Academy”. Some temples have been hard to survive through constant destruction and reconstruction. Fang Wanyou wrote a detailed description of the reconstruction process of Xiaoyi Lishe (Zheng Citation2001) in his book Rebuilding Xiaoyi Lishe.

Under Putian’s existing urban planning regulations (Putian Goverment and Putain Citation2010), many villages’ temples were destroyed during the process of urbanization, but there are still building types such as Xialin Community to meet the needs of ritual life (). Temples and squares are built on the roof of the commercial complex, while the stage and theater square are transferred to the community and used together with the basketball court, which is a new building type in Putian. In addition, in the wider Chinese circle, such types of buildings have been constantly produced (Wong and Chan Citation2017).

The past “destruction of folk temples” and the current rapid urbanization movement are not only the destruction of the temple building entity but also the destruction of the local “cultural network of power” (Duara Citation1988) proposed by Prasenjit Duara, which is formed by the combination of relationship, hierarchy and power and the destruction of the settlement organization relationship familiar to the population. With the support of the gentry, Xiaoyi Lishe resumed the ritual activities of Lishe with the temple building as the center. The reconstruction of the temple building on the material level and the revival of the ritual activities relying on the temple building on the spiritual level rebuilt the original organizational relationship and spatial form of the settlement ethnic groups. The case of Putian shows that folk belief and ritual life have the “habitat system” pointed out by Pierre Bourdieu (Bourdieu and Nice Citation1977). The cultural elasticity of the settlement itself can withstand the impact of external forces of the settlement and inherit and continue the traditional cultural customs and lifestyle in modern life.

4.3. The grassroots self-management function of “She”

“She” originated from the pre-Qin era and was the hierarchical privilege of the noble class to establish a society and worship gods. In the Tang and Song Dynasties, the content and form of “She” changed significantly, laying a path for the development of rural society, on which the political system and local power bodies were launched (Du Citation2016). The government of the Ming Dynasty paid special attention to the folk religious association, legislated to restrict the folk religious association, prevented the formation of folk religious power, threatened the rule, and replaced it with “Li She”, bringing the folk belief into the official sacrifice system. “She” has gradually become the symbol of the official administrative region and an important part of the urban and rural governance system. The “She” is built according to the “interior”, and the scope of the “interior” determines the setting of the “society”. Many “households” in different “li” combine with each other to form a “She” organization. The establishment of “She” gradually moves down from “li”, and village and ethnic communities rise (Tong Citation2019). The “She” bears the function of assembly during busy farming hours and the function of enlightenment during slack farming hours. As an architectural entity symbol of a dual track system formed by top-down administrative organizations and bottom-up nongovernmental organizations, the “community” has gradually developed into a gathering place for local people’s grassroots autonomy (David, Citation2007). Most of the events between settlements have to complete a series of rituals in the “She”.

The Ming and Qing Dynasties had a significant influence on the existing settlement form and the grassroots administrative system in Putian. During the early Ming Dynasty, the government controlled the grassroots society and established the Yellow Book Li-Jia system. The Li-Jia system, with the nature of grassroots political power, is a household management system that combines population and property. Li-Jia organization not only has the function of grassroots political power but is also the basic unit of local cultural life. The combination of Li-Jia organization and “She” has led to the emergence of “Li She” local grassroots organizations with “She” as the core. The rise of “Li She” has accelerated the alliance and development of Putian Nanyang Plain settlements. Through the “Li She” grass-roots organization system, rural space becomes the carrier, and the county government, the gentry’s class and the villagers interact with each other. Through different spatial behaviors, they compete and play games for space power, which is the dual track system of the township governance system in the Ming and Qing dynasties pointed out by Fei Xiao tong (Hsu, Citation1954) (). In local society, local organizations led by the gentry and imperial powers represented by county government officials interact with each other and work together in rural society. To achieve the grassroots infiltration of state power and the control of rural resources, it is also conducive to the rational distribution of resources and common development.

5. Conclusion: Urbanization and cultural resilience

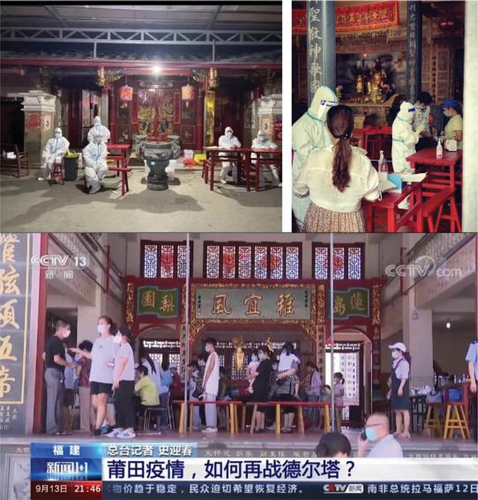

The ritual alliances’ function of local self-management can be traced over time. Zheng points out that the rise of regional ritual alliances may be the result of “ecological feedback” from collective cooperation to form “irrigation communities” in the Putian Plain approximately five centuries ago (Dean & Zheng, Citation2009b). The network constantly spread to the whole region in the following centuries and gradually evolved into a local autonomy nongovernment institution. In addition to the celebrations, the temples also function as community centers under different political and era conditions. It includes schooling children for the imperial examination system by the early 20th century, mobilizing villagers during the land reform movement, the collectivization of farms, the development of communes, and the Cultural Revolution in the Communist China Period, providing places for elderly gathering, childcare, and even nucleic acid testing during the pandemic period ().

Evolving ritual alliances have historically been an important factor in social organization in the Putian Plain, and they continue to play a crucial role in this area in contemporary China. They function across time as community management venues and tools of everyday life. It is a result of the development of a multilayered syncretic ritual field. To explore and understand how culture is a tool one can explore everyday politics. Some clues of such institutions have also been observed in some other cities of Fujian, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Hainan and Taiwan (Lin Citation2015), although they have been damaged by modernization during the past decades (Seligman et al. Citation2008). In contrast, in Putian, these temples continuously negotiate the forces of capitalism and nationalism and manage to preserve a vibrant space for the celebration of local cultural differences (Szonyi Citation2017).

Inevitably, urbanization and urban renewal since the 1980s have eliminated a large amount of traditional architecture, not only by developers or the government but also by villagers who want to upgrade their quality of life. The new concrete apartment blocks replace vernacular houses built of brick and broad highway and railway tracks cut through the center of traditional settlements. However, temples are often the last buildings left standing in a bulldozed village. With the backing of gods, temple leaders drew out negotiations overcompensation and new sites for the temples if they had to be torn down. In the case of Kuokou village, six temples of the village were moved and built in a row between banks of apartment buildings. In the Yanshou Weir area, eight temples were moved up the mountainside, arrayed in a row. In Nanmen village, newly rebuilt temples stand in between apartment blocks.

The ritual alliances in Putian managed to survive the challenge of urbanization and present a repercussion of local tradition by constantly recreating itself and bringing in contemporary discourse. Currently, in the urban and rural areas of Putian, there is evidence of local collective experimentation with new ritual traditions. Although originally based on indigenous myths and legends, they are all innovative adaptations of state ritual forms and ideas. This experimentation will undoubtedly enlighten the current urban planning and architecture, break through the disciplinary barriers, deepen the understanding of the history and culture of ancient villages, and build wisdom and social relations from the perspective of history and anthropology. It will help to integrate the traditional lifestyle and living environment with modern society, maintain the place identity (Proshansky Citation1978) and customs of local people, develop and plan places from a dynamic perspective, and reflect the resilience of local traditions, which will be the research direction of the development of traditional villages in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jing Zheng

Jing Zheng, Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture, School of Urban Design, Wuhan University. She teaches architectural history, theories, and design studios with a focus on cultural heritage. Her research interest is to study architectural heritage from the perspective of politics, social and cultural impulses by employing a historical-anthropology approach. She has published widely in Chinese, American, and Japanese academic journals.

Heng Huang

Heng Huang is a master student in the School of Urban Design, Wuhan University. His interests and practical activities range from architectural anthropology, architectural heritage, and vernacular architecture.

References

- Bourdieu, P., R. Nice, translated by. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice (Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812507.

- Cheng, C. Y. 1875. Putian shuili zhi:Guangxu yihai zhongqiu qin.Taibei. Cheng Wen Publishing Co., Ltd (in Chinese). https://books.google.fr/books?id=HYdEAQAAMAAJ.

- Clauss-Ehlers, C. S. 2010. “Cultural Resilience.” In Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural School Psychology, edited by C. S. Clauss-Ehlers. Boston: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-71799-9.

- Crissman, L. W. 1972. “Marketing on the Changhua Plain, Taiwan.” Economic Organization in Chinese Society 3:215. https://scholar.google.cz/scholar?hl=cs&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Marketing+on+the+Changhua+Plain%2C+Taiwan&btnG=.

- Dean, K., and Z. M. Zheng. 2009a. Ritual Alliances of the Putian PlainVol. One. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004176027.i-437.

- Dean, K., and Z. M. Zheng. 2009b. Ritual Alliances of the Putian Plain Vol. Two. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004176010.i-1062.

- Du, Z. Z. 2016. “She as the Belief, Local System and Folk Lore in Regional Society—— Rethinking the Studies on Southeast Shanxi in Recent Ten Years.” Academic Monthly 12:149–160. in Chinese. https://doi.org/10.19862/j.cnki.xsyk.2016.12.016.

- Duara, P. 1988. Culture, Power, and the State: Rural North China, 1900–1942. Stanford, USA: Stanford University Press. https://www.sup.org/books/extra/?id=2583&isbn=0804718881&gvp=1.

- Ebrey, P. B., and J. L. Watson. 1987. “Kinship Organization in Late Imperial China, 1000–1940. Edited by Patricia Buckley Ebrey and James L. Watson. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986. Studies on China, Vol. 5. Xvi, 319 Pp. Tables, Maps, Figures, Plate, Glossary, Index. $40.00.” The Journal of Asian Studies 46 (4): 903–904. https://doi.org/10.2307/2057109.

- Fan, Z. Y., and G. P. Lin. 2002. “Dividing Spirit, Pilgrimage Between Taoist Palace and Buddhist Temple in the Fujian and Taiwan Provinces and Its Cultural Significance.” Studies in World Religions 3:131–144. in Chinese. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-4289.2002.03.014.

- Faure, D. 2007. Emperor and Ancestor: State and Lineage in South China. Stanford, USA: Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.11126/stanford/9780804753180.001.0001.

- Feuchtwang, S. 2001. Popular Religion in China: The Imperial Metaphor. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003173410.

- FPDERA (Fujian Provincial Department of Ethic and Religious Affairs). (2002). Investigation Report on “Strengthening the Management of Folk Belief Activity Places in Our Province”. Printed manuscript (in Chinese). http://mzzjt.fujian.gov.cn/.

- Freedman, M. 1958. Lineage Organisation in South-Eastern China. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003135296.

- Freedman, M. 1979. “The Politics of an Old State: A View from the Chinese Lineage.” In Choice and Change: Essays in Honour of Lucy Mair, edited by J. Davis. London: Routledge. 2004. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003135906.

- Freedman, M. 2004. Chinese Lineage and Society: Fukien and Kwantung Volume 33. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003136569.

- He, Y. C. 2019. Reclamation and Irrigation:Researching on History of Farmland Water Conservancy in Ancient Putian (627-1850). Doctoral Dissertation, Nanjing Agricultural University(inChinese).https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFDLAST2022&filename=1022018517.nh.

- Hill, E. W., H. Wial, and H. Wolman. 2008. Exploring Regional Economic Resilience. hdl:10419/59420 [Handle]. Berkeley, Calif: Univ. of California, Inst. of Urban and Regional Development.

- Holtorf, C. 2018. “Embracing Change: How Cultural Resilience is Increased Through Cultural Heritage.” World Archaeology 50 (4): 639–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2018.1510340.

- Hsu, K., and F. L. 1954. “China's Gentry: Essays in Rural-Urban Relations by Hsiao-Tung Fei, with Six Life-Histories of Chinese Gentry Families by Yung-Teh Chow.” Margaret Park Redfield. American Journal of Sociology 59: 5. https://doi.org/10.1086/221416.

- Huang, Z. Z., Y. Zhou, (1503), and Chongkan Xinghua fuzhi. 2007. Compiled by Zhou Ying and Huang Zhongzhao in 1503, reprinted in 1871, reprinted in 1871, edited by Cai, Jinyao. Fuzhou: Fujian Renmin Press. ( In Chinese). https://books.google.fr/books?id=dIJGAQAAMAAJ.

- Hu, X. L., H. B. Li, X. L. Zhang, X. H. Chen, and Y. Yuan. 2019. “Multi-Dimensionality and the Totality of Rural Spatial Restructuring from the Perspective of the Rural Space System: A Case Study of Traditional Villages in the Ancient Huizhou Region, China.” Habitat International 94:102062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102062.

- Lin, M. R. 1986. “The Religious Sphere as a Form of Local Organization: A Case Study from Tsaotun Township.” Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology Academia Sinica 62:58. in Chinese https://twstudy.iis.sinica.edu.tw/Han/Paper/mazu/JiSiViewCaoTun.htm.

- Lin, W. P. 2015. Materializing Magic Power: Chinese Popular Religion in Villages and Cities. Cambridge, USA: Harvard University Asia Center. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1dnn9gs.

- Long, H. L., S. S. Tu, D. Z. Ge, T. T. Li, and Y. S. Liu. 2016. “The Allocation and Management of Critical Resources in Rural China Under Restructuring: Problems and Prospects.” Journal of Rural Studies 47:392–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.03.011.

- Proshansky, H. M. 1978. “The City and Self-Identity.” Environment & Behavior 10 (2): 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916578102002.

- PTXDFZBZWYH (Putianxian difangzhi bianzhuan weiyuanhui). 1994. Putian Xianzhi. Beijing: Zhonghua book company Press (in Chinese). https://books.google.fr/books?id=zaZzAAAAIAAJ.

- Putian Goverment, and Putain, G. 2010 Putian City Master Plan(2008-2030). PZ [2010] No. 34(in Chinese). https://www.putian.gov.cn/zwgk/ptdt/ptyw/200909/t20090914_76783.htm.

- Ruan, Y. S., Y. Shao, and L. Lin. 2002. “The Characteristics, values and the Preservation Planning of the Towns in Jiangnan Water Region.” Urban Planning Forum 1:1–4. in Chinese. https://doi.org/10.CNKI:SUN:CXGH.0.2002-01-000.

- Saleh, M. A. 2001. “The Decline Vs the Rise of Architectural and Urban Forms in the Vernacular Villages of Southwest Saudi Arabia.” Building & Environment 36 (1): 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1323(00)00025-1.

- Seligman, A. B., R. P. Weller, M. J. Puett, and B. Simon. 2008. Ritual and Its Consequences: An Essay on the Limits of Sincerity. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195336009.001.0001.

- Skinner, G. W. 1964. “Marketing and Social Structure in Rural China, Part I.” The Journal of Asian Studies 24 (1): 3–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/2050412.

- Szonyi, M. 2017. The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77k06.

- Tong, X. 2019. “State and Society: Li-She System and Rural Order in Ming and Qing Dynasties——Investigation of Huizhou“society”as a Clue.” Journal of China Agricultural University(social Sciences) 36 (6): 43–52. in Chinese. https://doi.org/10.13240/j.cnki.caujsse.2019.06.005.

- Verdini, G., F. Frassoldati, and C. Nolf. 2016. “Reframing China’s Heritage Conservation Discourse. Learning by Testing Civic Engagement Tools in a Historic Rural Village.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (4): 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2016.1269358.

- Wong, Y. C., and J. K. H. Chan. 2017. “Civil Disobedience Movements in Hong Kong: A Civil Society perspective.Asian Education and Development Studies.” Asian Education and Development Studies 6 (4): 312–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-11-2015-0056.

- Xi, W. Y. 2008. “A Brief Discussion About the Contemporary Folk Beliefs in Fujian Province.” Studies in World Religions 2:117–126. in Chinese. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-4289.2008.02.015.

- Xiong, M. 2017. “Research Progress and Disciplinary Approach of Chinese Traditional Dwellings.” City Planning Review 41 (2): 102–112. in Chinese. https://doi.org/10.CNKI:SUN:CSGH.0.2017-02-019.

- Xu, C. G. 2003. “Thoughts on Building Ancient Village Historic and Cultural Conservation Area.” Zhejiang Social Sciences 3:149–152. in Chinese. https://doi.org/10.14167/j.zjss.2003.03.032.

- Xu, C., T. Z. Wen, and S. Y. Liu. 2020. “Review on Urban and Regional Resilience Research in China.” City Planning Review 44 (4): 106–120. in Chinese. https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:CSGH.0.2020-04-014.

- Xu, C., Z. C. Zhao, and T. Z. Wen. 2017. “Resilience: Conceptual Analysis and Reconstruction from Multidisciplinary Perspectives.” Journal of Human Settlements in West China 5:59–70. in Chinese. https://doi.org/10.13791/j.cnki.hsfwest.20170509.

- Yang, L. G., H. L. Long, P. L. Liu, and X. L. Liu. 2018. “The Protection and Its Evaluation System of Traditional Village Culture: A Case Study of Traditional Village in Hunan Province.” Human Geography 33 (3): 121–128+151. in Chinese. https://doi.org/10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2018.03.015.

- Ye, C., and Z. Liu. 2020. “Rural-Urban Co-Governance: Multi-Scale Practice.” Science Bulletin 65 (10): 778–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2020.02.021.

- Yuzuru, O. 1938. “臺灣北部村落に於ける祭祀圏.” 民族學研究 4 (1): 1–22. in Japanese. https://doi.org/10.14890/minkennewseries.4.11.

- Zhai, G. F. 2018. “How Can Cities Become Resilient.” City Planning Review in Chinese 42 (2): 42–46+77. https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:CSGH.0.2018-02-008.

- Zhai, G. F. 2022. “Scientific Planning to Improve Resilience.” City Planning Review in Chinese 46 (3): 29–36. https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:CSGH.0.2022-03-004.

- Zhai, G. F., and C. H. Xia. 2021. “Strategic Emphasis on the Construction of Resilient Cities in China.” City Planning Review 45 (2): 44–48. in Chinese. https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:CSGH.0.2021-02-028.

- Zhang, Y. Y. 1974. Ming Hiatory. Beijing: Zhonghua book company (in Chinese). https://books.google.fr/books?id=XJxCAAAAYAAJ.

- Zhang, H. L., J. Chen, and C. S. Zhou. 2017. “Research Review and Prospects of Traditional Villages in China.” City Planning Review 41 (4): 74–80. in Chinese. https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:CSGH.0.2017-04-013.

- Zhang, X., Y. He, and W. Deng. 2020. “Multi-Mode Research on Conservation and Development of Historic and Cultural Village in Urban Fringe: Taking Qiqiao Village, zhenhai District,Ningbo City as an Example.” City Planning Review 44 (4): 97–105. in Chinese. https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:CSGH.0.2020-04-013.

- Zhang, Y., and Z. Wu. 2015. “The Reproduction of Heritage in a Chinese Village: Whose Heritage, Whose Pasts.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (3): 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2015.1114505.

- Zheng, Z. M. 1989. “明清福建的里甲户籍与家族组织.” Journal of Chinese Social and Economic History 2: 38–44. in Chinese. https://doi.org/10.13469/j.cnki.zgshjjsyj.1989.02.006.

- Zheng, Z. M. 1995. “神庙祭典与社区发展模式──莆田江口平原的例证.” Historical Review (01): 33–47+111, in Chinese.

- Zheng, Z. M. 2001. Family Lineage Organization and Social Change in Ming and Qing Fujian. Honolulu, USA: University of Hawaii Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780824842017.

- Zhuang, Y. Z. 1973. “Temples, ancestral Halls and Patterns of Settlement in Chushan.” Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology Academia Sinica 36: 113–140. http://lawdata.com.tw/tw/detail.aspx?no=220723.