ABSTRACT

New designs in historic precincts often spark considerable discourse, but there has been limited research into quality and relational aspects that allow communities to perceive the new architectural objects. A lack of understanding of these concepts, a preference for certain conservation principles, a misapplication of design approaches, and misconceptions about the character of a historic precinct can disrupt historic coherence. This paper explores conservation principles, and design approaches to form enhanced policy and design tools for coexisting new and old within historic precincts. The study employs discourse analysis, content analysis, and inductive methods to probe the matter further. The study results indicate that conservation agencies tend to pay more attention to quality indicators than relationship factors of design, leading to an overemphasis on contextual-based designs and an under-emphasis on other possible design styles. In response, the study offers policy and design-enhancing tools such as introducing a six-ranking system for conservation principles, proposing six novel design approaches, and formulating three hypotheses. These new tools can help designers, researchers, and urban planners plan, and manage historic precincts and make informed decisions, and design future interventions.

1. Introduction

The city historically has a poetic texture that reflects human existence. Its visual tissues evolve rhythmically with age. Different people with different identities and cultures live there, work there, and die there, leaving their traces. Architectural objects inevitably play a mythical role when architects have control over their literal design stories, but their impact on an environment attracts a variety of interpretations beyond just function and aesthetics. The ongoing debate about adding new layers to the historical context is conceptualized in this paper as a relationship between new and old that is polarized by several factors. Existing literature has identified the use of complex jargon, cramped design methods, a linear preference for regulatory principles, and a myopic philosophical disposition toward design that is often misunderstood in traditional settings.

Based on these technical implications, the Historic Buildings Preservation Society (Citation2021) reaffirms that all historic environments have inherent social, cultural, educational, and spiritual significance. They provide a sustainable foundation for inner-city upgrading and architectural creativity. These sets of inputs related to valorization, injecting neighborhood livability, and innovation are inseparable from the interests of urban sustainability (European Environment Agency Citation2021). Diversity and inclusivity are two terms that better describe the historical situation of this type (heterogeneous or homogeneous). Diversity represents the autonomous existence of urban structures (Karimi and Motamed Citation2003), but they live entirely as ecosystems, pointing to their integration on that scale (Swensen Citation2012). Mehr (Citation2019) suggested that cultural properties have recreational value, but their receptivity and vulnerability expose them to external and internal manipulative energies. Some scholars refer to such forces as urban tensions (Rahbarianyazd Citation2017; Ukabi Citation2016). These forces, whether unevenly or evenly stratified, influence the way sites undergo life processes similar to those of living organisms.

However, looking back at previous branding projects for some cities in historic locations, their relationship with the existing historical context has been twisted. Some architects advocate building on Outstanding Universal Values, while others propose an entirely new language (Abdel-Kader Citation2019). These two opposing modes of argument in historical precincts reflect existing conservation legal structures and designers’ attitudes, which serve as a contextual design schema for a purported end while passively inhibiting other viable human-centered design strategies. Contextualizing this from a conservation perspective suggests that physical, economic, and social changes within and around historic urban areas require control to avoid a continuous loss of cultural identity (Tiedell, Oc, and Heath Citation1996). This essay backed Toprak and Sahil’s (Citation2019) views on the nature of the new designs as communicating cultural and environmental dynamics rather than the illogical replication of old expressions. The latter has repeatedly reduced the historical urban fabric in various historic towns with heterogeneous characters. Normally, regulations aim to pave the way for high-quality design outcomes and to address other social pathogens like demolition, displacement, and the architectural ubiquity of building designs that violate historic limits (Jokilehto Citation2007, 33; Ukabi Citation2016). Similarly, May and Griffiths (Citation2015) revealed that to meet the contemporary needs of the community and accommodate new functions, altering, adapting, or adding to historic buildings and precincts nowadays represents an existential phenomenon. In response, the Getty Conservation Institute (Citation2013) organized a discussion with four panelists made up of experienced urban thinkers and practitioners, whose prepositions embolden this discourse. They concluded that cities make time visible, architecture is a scene, design has many layers, and change or continuity must be open to dialogue. The established premise is a means to discover various loopholes in current regulatory documents regarding contemporary works in the historical environment and correlate them with design typologies used by architects to add new layers in the same context.

Based on this background, the purpose of this paper is to explore conservation guidelines and the numerous design typologies used by architects to add new layers to historic precincts in order to provide extra enhancing tools for the union. The objectives of the study are: 1) to assemble quality and relationship improvement tools; 2) to encourage built heritage layers’ continuity; 3) to identify patterns of inclusive insights that will enhance the existing phenomena; and 4) to identify new directions for further study. The study will contribute to the general discourse on contemporary architecture in the historical environment as well as built heritage and Integrated sustainable conservation. The newly formed tools, like classification of design approaches and ranking of conservation principles, will assist designers and regulators during the preliminary design stage of projects in historic precincts to resolve quality and relationship matters.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Existing theoretical discourse on new and old in historic precincts

2.1.1. Regulation narratives on new and old

The ability of the conservation legal framework to absorb additional generational changes and adapt new perspectives on urban preservation (Dudzic-Gyurkovich Citation2017) would increase inclusivity and environmental sustainability in accordance with UNESCO (Citation2011). The Royal Commission for Fine Arts (Cantacuzino Citation1994), for instance, raised an earlier scenario where the Town Planning Act of 1947 was ignored by designers because of the criteria specified for regulating contemporary works in historical contexts. Its impact produced unsustainable imitations of urban rehabilitation projects. This body has encouraged the use of an inwards-outwards approach to design in blending new and old fabrics without placing a high emphasis on architectural styles, materials, and construction techniques. Their suggestion seems to represent a one-way of thinking, as if all precincts’ situations are the same. This preference and other related ones surrounding the discourse on new and old lead to the following questions, but not the only ones: What about the outward-inward approach? Is it logical to generalize design approaches as causal? How do design approaches respond to the regulatory guidelines criteria?

The pertinence in some historic cities today is the lack of appropriate sustainable intervention schemes and policies that increase historic artifact hierarchies quantitatively. To arrive at such desired outcomes, then, recognition of specific types of environments, either heterogeneous or homogeneous, would constitute the bedrock for the intervention framework. Tendencies that overlooked the observed variables in different historic cities with medieval cultural traces ended as pastiche. Examples of such historic precincts are Lithuania (Navickiené Citation2012), Safranbolu in Turkey (Birlik Citation2013; Toprak and Sahil Citation2019), and the Silesia region of Poland (Łakomy Citation2019). Contrary to popular belief, creativity is stimulated by dynamic historic settings, but fragile historic precincts present a difficult design scenario due to a lack of “appropriate urban vision” (Alderson Citation2006). This concept challenges the potency of each intervention design plan through the lens of a particular historic landscape type. However, this aspect has been inadequately addressed within existing international and national conservation principles.

Although large findings were published that focused on the analysis of architectural objects in the discourse of new designs in a historical context, documentary evidence shows that scanty research has been conducted on the evaluation of the regulatory document’s stance and logical exploration of design approaches on this issue. This scenario formed the study’s background for this paper. First (Abrar Citation2019), whose work included 21 legal instruments, concentrated on a 20-point guideline mechanism. That study focused on a framework for evaluating contemporary structures using international principles of heritage, but the use of two architectural terms, “criteria” and “approach,” pushes our imagination toward design typologies rather than principles. This made it difficult to distinguish between regulatory guidelines and design criteria. Abrar’s research shows that the international instrument’s attitude toward new designs in its historical context unifies with the Athens Charter of 1931 as the primary instrument encouraging principles to guide new works.

This is in contrast to other expert publications (Iamandi Citation1997; Navickiené Citation2012), whose findings identified monument integrity and authenticity of character as the driving forces during this period. The emphasis on compatibility with monumental value certainly reduced the perceived number of pragmatic, new-quality designs. The second source (Toprak Citation2020) explored the limits of designing new buildings with modern features without harming the historical context. In the process, engaged 15 renowned contributors on approaches and forums and 22 international conservation legal documents, leading to the extraction of 10 criteria deemed appropriate for designing new buildings in historic locations around the world. Analyze the principle preferences across the selected criteria and created a guideline for determining the limit. Their findings first demonstrated that the designers’ strategy emerged as a function of the new structure and had to be appropriate for the entire context (carrying roughly 53% of the 10 points examined).

In contrast, the principle of “the new is necessary” cuts across the charter’s broad scope. The degree of preference given by ICOMOS and UNESCO to “not harming” an existing context shows a secondary interest, different from Toprak’s first results, in that the “new must be compatible with the whole,” which dominates the perception of the regulatory instruments. Based on that inference, further criteria were suggested for designing new buildings in historic cities, which, from a logical perspective, are context-bound. A reconsideration of existing design approaches used by designers is required when fine-tuning the future direction of the three relationships discussed.

Several scholars have written about the communicative potentials of architecture, among them Taraszkiewicz (Citation2002), who states that each generation seeks its own identity in symbols. Architecture is such a symbol because it represents both creative and aesthetic aspects. This interface demonstrates a preference for certain design approaches by designers. As a form of design thinking, Smith (Citation1975) raises the premise that, in times when continuity is hard to create, monumental buildings can connect cities and build bridges between the past, present, and future. This was a common slogan during the 20th century. As part of the design experiments for designing in sensitive environments, in this case historical locations,Sanoff (Citation1988) formulated a “best-fit rule” for evaluating infill developments. Their results use visual evaluation criteria based on an Impressionist approach.

A related conceptual framework was developed by Groat (Citation1988), focusing on infill contextual design strategies. Similarly, Carmona et al. (Citation2003, 187) generated the Continuum for evaluating contextual harmony based on three specific outcomes: uniformity, continuity, and juxtaposition. From the perspective of comprehensive planning, better city planning would delineate liveliness and real continuity when it captured the past and present material culture of a historic city for future transformation (Burtenshaw, Bateman, and Ashworth Citation1991). However, it is quite problematic when preservation and restoration interventions in the physical structure of the historic precinct become susceptible to false designs and misrepresentations of historical continuity as original approaches (Yeomans Citation1994, 167). At the urban landscape level, Baytin (Citation2003) undeniably posited that modernization is a new-age wave in which contemporary ideas and material innovations flow and are now integrated.

In reality, Stavreva (Citation2017) reemphasized that the city is a playground where new architectural objects are intermixed with existing buildings, thereby giving rise to a fusion of the new and the old. The historic layer is a microcosm of the city’s history, which means that not only does new construction impact historic areas, but it also interacts with the city as a whole. It breathes life into the area and is a sustainable strategy to use to build courage in the new generation that is relocating. This indicator demands more than just nostalgia for cultural and environmental perceptions. A recent example of value-based and cultural-based design was illustrated by Hawkins and Brown Architectural Firm (Citation2021) when they adapted the historic Plumstead Library into the Plumstead Center in Greenwich, London. Their creative design scenario states that the new civic center represents “the boundary between the old and the new” by inserting a glazed transitory space between two historic blocks, thereby creating a new ambiance for the community.

2.1.2. Design approaches for adding new designs to historic precincts

From the collation of design approaches used by designers to add new designs in historic areas, the polarization between historicization and modernization seems to be nurtured by design ideologies. Several scholars like Eleishe (Citation1994) grouped them into replication and contrast. The historicized design was imagined by Baytin (Citation2000) calling it a stylistic approach by combining localism and historicism to form a prescriptive approach whose qualities depended upon regulation. In a similar narrative, Skerry (Citation2012), using the visual scale technique, concluded three general approaches for designing new infills in historic districts historicized, hybrid (flexible), and modernist approaches. Sotoudeh and Abdullah (Citation2013) later demonstrated the degree of replication and contrast in preserving cultural values which followed the formalism and symbolism of the design of the new infills. The preferences of scholars who categorize design approaches fall into 11 contextual design types, .

Table 1. Contextual-based design approaches direction (authors, 2022).

The limits of new design additions to context strategies restrict other design possibilities. Such box-like adaptation is unsustainable given the multiplicity of historical tissues. This shortfall manifested the negligence of eight design strategies not referenced in any of the existing classifications in the literature. The missing approaches include a philosophical approach (Ruskin Citation1890), a spatial approach (Fontana Citation1946), a “Collage” city approach (Rowe and Koetter Citation1978), a strategic approach (Doratli Citation2005, 753–754; Hunt Citation1996; Rodwell Citation2003, 65), a participatory approach (Basarir, Saifi, and Hoskara Citation2016; Khalaf Citation2015), a partitioning approach (Abdelwahab Citation2018; James Citation1992; Zonouz Citation2018), picturesque design strategy (Elsea Citation2021), and humanistic approach (Abdelsalam Citation2021).

2.1.3. Examples of historic precincts with an internalized relationship of new and old

The narratives that configure the urban heritage constitute a spatial order that manifests culturally and materially at different periods as a form of cultural value multiplicity viewed sequentially (Pawlicki Citation2015). The Polish context played a pivotal role in the cultural and procedural development of the various charters from 1931 (Athens Charter) to now with technical representation. Considering this onus, localized urban heritage from a Polish perspective allows for co-creating new architectural layers without abandoning the rich historical and cultural heritage of the surrounding areas. They also chaired the Krakow Charter (Citation2000) which emerged as the second regulatory instrument with wider guidelines for contemporary architectural inputs in historic precincts. They borrowed from the words of Gustavo Araoz (ICOMOS President from 1955–2009) – The drivers of the heritage sector would be “assets of the future” and extracting an adage from the Polish constitution “toward the common good” to set forward the first and second Polish Resolutions.

The concept can be re-articulated as embracing potential discord by treating change as a creative process to advantageously safeguard and maintain monuments. However, Furtak (Citation2015) debated that modern architecture, particularly in the postwar era, as interpreted via COP (emblematic of Polish architecture), exhibited measured urban creativity that also accommodated the needs of the local community during the 19th century. Predominantly, such attributes were dictated by modern movement advocates, where in some global scenarios, an “apartment machine” replaced ornamentation, often regarded as a transgression. This notional labeling, which evidently strips historic locations of their sustainable resources, subsequently opens another void, which further draws attention to and ignites controversy over the preservation of high-quality modernist structures in conservation dialogues.

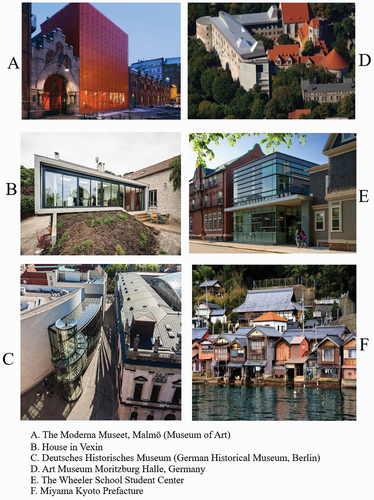

The guiding principles of safeguarding historical cultural heritages and implementing innovative urban designs consistently dictate the progression of every civilization from antiquity to the present day (Kosiński Citation2015). This suggests that traditional and contemporary elements can indeed coexist, despite the inherent challenges in navigating the competing interests, the aggregation, and contraction of architectural endeavors. illustrates examples of how this has been successfully achieved across various applications and locations.

A.The Moderna Museet, Malmo (a Museum of Art), designed by Tham and Videgard Architekter (Citation2010), and Photo by Lindman (Citation2010) – Combined reconstruction with adaptation. B. House in Vexin designed by Jean-Philippe Doré, France in 2014 (Designrulz Citation2015) – Horizontal extension. C. Deutsches Historisches Museum (German Historical Museum), Berlin was designed by I. M. Pei in 2003 (DHM/BerlinOnline Citation2023) – New building. D. Art Museum Moritzburg Halle, Germany designed by Nieto Sobejano Arquitos (Badalge Citation2018) – rooftop addition and a horizontal extension. E. The Wheeler School Student Center completed in Rhode Island, 2011 was designed by Ann Beha Architects and photograph by David Lamb (Meinhold Citation2011) – New infills. F. Miyama Kyoto Prefecture (Japan Experience Citation2018) – New insertion

From above, example “A” presents a new layer added to an existing historic context or cultural heritage with its scale displayed. It allows for the reading of the old layers into a fully contemporary expression without forgery of visual imagery. “B” integrates three historic homes with a modern extension. The traditional feel of the structures was maintained and a minimalist geometric block in composite colors and a bold glass facade is added with a contemporary character. The new horizontal extension is kept within the limits of the traditional context while exhibiting the present age’s stamp.

“C” is a new building that incorporates a new semicircular glass and steel structure opposite and in proximity to the historic Baroque arsenal building as a visual transition between the new exhibition building and the existing structure and it diffuses the contrast intensity of the new while also serving as a strong visual connector despite the physical setback. In “D,” the introduction of the new roof and tower did not mimic the traditional appearance of the historic Gothic Castle. Instead, the design puts forth a modern architectural solution that expanded the exhibition space.

Moving on to “E,” the new addition is a combination of glass and green roofs, establishing a bridge between two historic buildings of the Wheeler School – the Alumnus House and the Student Union. This modern addition infuses the historic school with a sense of “forward momentum,” as embodied in the horizontal glazed curtain wall (Meinhold Citation2011). Consequently, this transparent layer allows for a clear view of the underlying old brick Colonial Revival stylistic buildings.

Finally, “F,” Miyama Kyoto Prefecture, exemplifies the use of modern architecture in an urban context. The village depicted is a typical rural mountain locale, delineated by traditional thatched houses, known as Kayabuki (Japan Experience Citation2018). A modern, geometric square block has been integrated using brownish hip roof tiles and a white envelope. Importantly, it aligns with the environmental hierarchy of the settlement and the orientation of the riverside street.

Other European historic cities like Lisbon opened up to new approaches to the conservation of heritage by understanding the contemporary forces that energize today’s urban functioning and development-Knowledge, creativity, technology (Dudzic-Gyurkovich Citation2017), and big data. The principle of multiple layering can only materialize when the various layers are unhinged for urban sustainability. Another paradigm that has emerged today is the displacement of art by the designer’s preference for “beauty,” which aligns with the premise injected by Eco and de Michele (Citation2005, 415). These possibilities were exemplified in the “restored and new Market Halls in Barcelona” (Węcławowicz-Gyurkovich Citation2019), where all the new hierarchical layers revived a desirable market culture and urban ambiance. Unsustainable is the lack of cohesive policy on modernization projects and planning principles that led to the spatial uniformity that was co-created in Katowice, Silesia, based on individual restoration efforts of their domestic buildings (Łakomy Citation2019).

2.1.4. The European quality principles for interventions

Advancing quality principles (Articles 3–5 of ICOMOS Citation2020):

Cultural assets should be used in respectful ways, to safeguard their meanings and values and to become an inspiration for local and heritage communities and future generations,

Recognition of cultural heritage as a common good and responsibility should be a precondition of quality. Cultural heritage conservation should be understood as a long-term investment for society

Cultural values should be safeguarded when assessing the overall costs and benefits of an intervention, and considered at least on an equal footing with financial value.

Under design, taking from (Articles 15–19 of ICOMOS Citation2020), the principles laid down are:

New project proposal should provide a complete SWOT analysis of the existing cultural heritage status and its context,

Additions of new elements or new uses should ensure balance and harmony in its dialogue with the existing values,

New functions should respect and be compatible with the heritage site, meet community needs, and be sustainable,

Projects planning and maintenance should involve the local communities,

Reconstruction actions would require extra scrutiny and conformity to the selection criteria of this Quality Principle, and EU values and treaties.

2.2. Research methods

The research methods adopted for this qualitative research are discourse analysis, content analysis, and inductive approaches. They are techniques that deal with text (Hodges Citation2015) in its broadest sense as intertwined with visual data sources (Blommaert Citation2005, 3). Because discourse is made up of many definitions, this study connects with the one described as a set of texts that fabricate an object (Foucault Citation1972, 49). They also align with the objectives of the study, which seeks to explore the current state of conservation principles and design approaches used to add new layers to historic precincts with the intent of discovering extra tools to improve their bonding process. By implication, contextualizing these linguistic and social research methods in the built heritage domain is critical at a time when we are witnessing multidisciplinary discourses concerning interventions in the historical context.

The complexity of knowledge-based regulatory criteria, design typologies, and various modes of inter-textual linkages and interpretations are additional characteristics of the study. They are investigated and analyzed in order to recognize and classify logically relevant existing ideas and patterns in relation to new designs. The ideas from Elkad-Lehman and Greensfeld (Citation2011) on intertextuality are also built upon because of their suitability for describing an object’s character or a textual pattern. Research on related topics that applied any of the adopted methods above includes Waterton et al. (Citation2006), who engaged Critical Discourse Analysis to discuss how heritage narratives are dominantly represented using the Burra Charter as a case study. Discourses about the collective housing architectural forms of 20th-century Paris were used to show the relationships between openings and closures created by basic urban components (Han Citation2015).

Furthermore, Taher Tolou Del et al. (Citation2020) used content analysis to identify the significant semantic values that affected the process of architectural conservation and to rank each value according to the published literature. Bakri et al. (Citation2006) used the inductive method to investigate the relationship between local communities and their cultural heritage in Malaysia’s George Town World Heritage Site. Norton (Citation2018) used it to highlight the issues with English building craftspeople and the demand for heritage preservation in site construction. Synthesizing the three qualitative methods above to explore conservation guidelines and design approaches could open up new logical reasoning and the discovery of new tools.

2.3. Research design

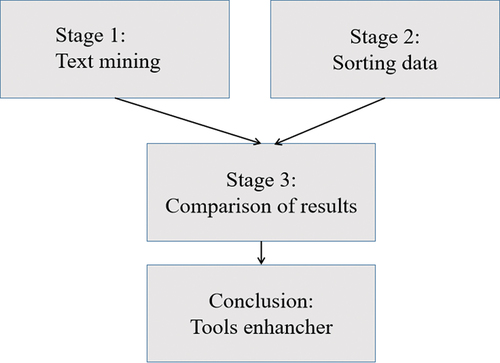

Based on this context, a three-phase research design was devised to guide the overall research process and simplified conceptually to foster its adaptability and transfer-ability by other researchers. Thus, the first stage is the “Text” mining stage (denoted as T), the second stage is the “Sorting” of data (abbreviated as S), and the third stage is the “Comparison” of results (named as C). An integration of the stages represents the TSC-Methodical design, .

The first stage, which is the text mining phase of the research process, followed a parallel reading of published works that focused on the discourse of the two main concepts at a general level. On the one hand, to capture what other studies have asserted concerning the state of regulation and design aspects of bonding new and old and give a clear vision of the corpus. The sorting of data was handled in stage two, where all the data sourced in stage one was sorted to spot patterns and compress their bulky status into meaningful versions that are logical to analyze. Still with the inputs of translating qualitative data inductively into numerical data that aids scientific findings, representation, and understanding using Wondershare EdrawMax. The comparison of results in the third stage provides an overview of the relationship between the concepts and variables and inserts interpretation according to the behavior of the results. Trying to illuminate the probable connections or disconnections between them, to create new ways of knowledge and hypotheses for continuity, and to further studies.

2.4. Research procedures and data specification

We first segmented the discussion at a random sampling of sources into four basic sub-themes for coherence and to take notes on the key scenarios: a) Regulation narratives on new and old; b) Design approaches for adding new designs to historic precincts; c) Examples of historic precincts with an internalized relationship between new and old; d) The European Quality Principles for Interventions. The reading of texts was narrowed down (focus reading) on conservation principles and design approaches to drive the objectives of the study through a content analysis.

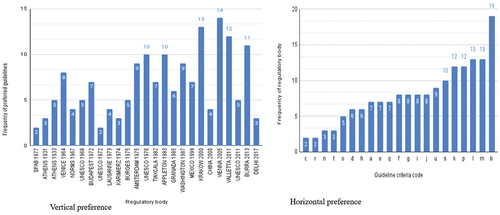

On the conservation principles inventory, a total of 25 regulatory instruments were selected and examined. The selection criteria for these agencies were based on: 1) the ones that dealt with new designs as a type of conservation action in cultural heritage; 2) the ones with international or national recognition, such as the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the Council of Europe (CoE), 3) titles like charters, recommendations, reports, declarations, resolutions, or memoranda; 4) Attention was given to the document’s themes, definitions, policy statements on contemporary architecture, and design-related quality statements by each regulatory body. 21 guidelines criteria were identified for the next-stage conservation principle’s preferential check, : vertical preference and the horizontal preference integrated.

Table 2. Regulatory bodies preference (authors, 2023).

On the design approaches inventory, a random search of works that discussed design issues concerning new designs in the historical precincts was conducted in renowned databases and repositories. The search was limited to 2021, the year this study started to have a defined direction from a broader research project on “New and Old Relationships in a Heterogeneous Historic Environment.” The selection criteria followed: a) All synonyms of new designs – new architecture, contemporary design or architecture, modern addition, new buildings, insertions, or new in-fills, free-standing buildings, and extensions at both architectural scale (single architectural heritage building) and urban scale (group of buildings, context, setting, place, site, etc.) – were embraced. b) Titles, abstracts, methodologies, and definitions of design typologies provided by various researchers were considered. c) Adaptation, which appears as a design typology, has been included but excluded when applied as a conservation principle. From this collation, the design types found in the literature exploration came to 43, including the ones that previous studies failed to capture. d) Design terms that actually represent grouping were excluded, for example, contextual design approaches, etc., as shown in .

Table 3. Design approaches new classification (authors, 2023).

The data for this study was mostly from documentary sources like books, published articles, book chapters, and dissertations/theses sourced from renowned databases and repositories online, conservation bodies’ dossiers, and institutes involved in built heritage conservation. As well as visuals from online architectural discourse platforms, designers’ websites, museums’ portals, Webinars, and travel blogs. Although the study is qualitatively structured, the conversion of qualitative data into quantitative data logically supported the handling of the findings, concrete results, and interpretations.

3. Results

The data from above provide two sets of results under the conservation regulatory bodies in accordance with the gauge introduced by the two mean values of equal or greater than 7 for the vertical preference and equal or greater than 8 for the horizontal preference. The vertical preferences depict how each body is compared against the 21 guidelines. On the horizontal preference chart, each of the 21 guidelines coded (a-u) is plotted across the 25 regulatory bodies and their stances. The vertical preference is chronologically arranged according to the year the principle was enacted, whereas the horizontal preference data was visualized in ascending order to simplify the understanding of the results. Any regulatory body that scores about the vertical preference mean value and above (7) is selected as a key promoter on the one hand, and on the other hand, those guideline criteria represent the most preferred group. The horizontal preference average mark of (8) possesses a similar application to that of the vertical preference but provides a check and balance to ascertain the most preferred guideline criteria, .

Figure 3. Regulatory bodies’ guidelines criteria preferential treatment (authors, 2023). The 21 guideline criteria are coded as (a-u): a.New work should avoid forgery approaches. b.Protection of monuments’ character/surroundings, historic values and not demolish. c.Demolition of slums surrounding monument for greenery and situation removal of buildings. d.Permit use of modern materials, advanced techniques and sciences. e.Styles of all periods should be represented/respected. f.Rigorous scrutiny of contemporary proposals/new materials by specialists. g.Permit change of function/modifications as urban evolution/continuity. h.Avoid distortion or conjecture but maintain consistency. i.New must be distinct and bear contemporary stamp (mark of our age). j.Valorization of cultural heritage as tools for progress. k.New role/adaption of the “historic groups” and authenticity/integrity should be regarded. l.Contemporary architecture as part of town-planning scheme for future development demands administrative resources. m.Avoid new uses that rip residents’ liveliness and historic condition. n.Contemporary architecture/change must add or be of high quality. o.Contemporary interventions should consider social costs. p.New should be harmonious/contextualize with its surroundings/whole town. q.Continue to use traditional crafts and methods (contemporary vernacular architecture) r.Homogeneous groups of historic and architectural areas should continue unchanged. s.Safeguarding the natural or man-made environment as umbrella concept for heritage care (activities and interventions). t.Urban context analysis should precede new construction. u.Duplicate Venice Charter principles

From above, the results show an order of the regulatory bodies’ interest regarding the introduction of new designs in historical precincts in both axes analyzed. From the vertical preference, Vienna 2005 came in highest with 14 points, which means it contains approximately 24% of the guidelines criteria identified as quantified above. Next is Krakow 2000 with 13 counts, which equals 22%. Valletta 2011 follows the order with 12 points, which translates to approximately 20.2%. Next in line is the Burra 2013 with 11 points, which means 18.5%. UNESCO (Citation1976) and Appleton 1983 both scored 10 points (17%). Amsterdam 1975 and Washington 1987 both came out with 9 points (15%). Venice 1964 featured 8 points (13.4%). While the ones at the starting average mark of 7 points (12%) are Budapest 1972, Tlaxacala 1982, and Mexico 1999. The vertical preference results also show regulatory bodies’ interest in new designs in the historical precinct started to gain significant ground around the 20th century.

The results of the horizontal preference were another order of the most preferred guideline criteria. A total of 11 guidelines criteria met or passed the average mark out of the 21 evaluated. Code‒a with 19 points, represents the most emphasized principle, and 19 regulatory bodies contributed to it. The next on the list is codes‒l, m scored 13, which implies 13 bodies gave their consent to it. Another pairing occurred, with code‒k, and p scoring 12 points as the sum of 12 regulatory instruments. Code‒s appear with 10 points, which means 10 conservation bodies supported them. Code‒u followed with 9 points in that sequence. The codes at the bottom of the range are f,g,i, and j which came out with 8 points, indicating lower momentum from the regulatory bodies. It is this order of preference with the help of the frequency that led to the conceptualized ranking of guidelines criteria into 6 ranks as 1st–6th and provides the evidence to why some criteria appeared isolated while others came in clusters in .

Table 4. Ranking of key guidelines criteria (authors, 2023).

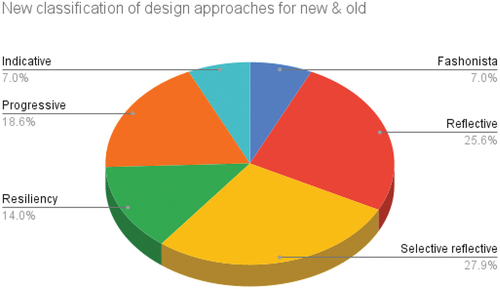

On the aspects of design approaches, the sorting in above provides an inductive technique of inclusion and avoids any form of reduction in order to develop a more reliable classification. According to the understanding gained from reading the definitions provided by various authors, there are six major classes of design approaches conceptualized. In each case, a set of design typologies serves as the measurement for the frequency. The results show selective-reflective with 12 design typologies as the most highly used approaches. Next to it is the Reflective approach, with 11 design typologies. The Progressive approaches came in eight design typologies. The resiliency approaches appeared in six design types. While the indicative and fashionista approaches both had three design typologies each, The data shown in is simplified visually with a chart in for emphasis.

The results displayed in indicate that the sum of selective-reflective and reflective approaches occupied approximately 53.5% of the design approaches used by designers to add new designs in historical precincts. While the other four design approaches – indicative, resiliency, progressive, and fashionista – took up the remaining 46.5% of applications.

4. Discussion

In the literature explored, attempts to classify design approaches aligned with the 11 contextual approaches collated (see ). Such a claim was supported by the eight design typologies left out by previous studies. The discourse also identified six out of many successful new design projects globally (see ), and on the other end of the range are some intervention examples that ended in unhealthy replications. They showcased different applications of new designs at diverse historic precincts to communicate the dynamic qualities of design through the successful interventions. This evidence could change our perception of objectively declining new designs in historic precincts as a threat without a thorough assessment. The unhealthy design outcomes were traced to control measures that over-stressed on principles that nursed only the existing artifact’s value in the new as a kind of predetermined design solution. The successful ones allowed the historic situations to determine the endpoint while interconnecting the principles responsible for their union.

When missing design types in the existing classification of design approaches were added to the data samples on design sorting, they influenced the outcome of the classification process. The scope of sub-grouping (design typologies) was expanded, providing the opportunity to regroup them in a more inclusive manner without discarding any design types that fall outside the linear context approach. We have observed that most of the design typologies that constitute the ones frequently used by designers belong to the Selective-reflective and Reflective design approaches. They relate broadly to the contextual design approaches identified in the literature (see ).

The commonly used design approaches emerged because conservation agencies overemphasized the monument’s value during the formative phases of the regulations, which influenced most subsequent principles. For this reason, the Venice Charter of 1964 doctrine is referenced in almost all the agencies after that year, but the application of its content has been challenging. It was not until the 20th century that the discourse on reconsidering the contributions of new designs to the historic surroundings began to gain momentum. Today, conservation agencies such as Docomomo International, the Getty Conservation Institute, Historic Heritage England (formerly English Heritage), and others has taken on the challenge of bridging this built heritage dichotomy. Another example of good practice is Polish heritage management, which conceptualized using cultural resources for the “common good,” as shown by the Krakow Charter of 2000.

The findings show that existing technical standards celebrate contextuality above other guidelines criteria nuances. In the process of applying the guidelines criteria dominantly preferred by regulatory bodies (see and ), especially the ones ranked from 1st to 3rd. They passively influenced the design course to approaches that satisfy two design ideologies: a) Approaches that reflect previous character and patterns of the old; b) New development selects certain elements or components of the old as preference (see ). At its core, design is recognized for its many layers, an idea reinforced during the Symposium conducted by the Getty Conservation Institute. While there is consensus on this concept, there is disagreement over the inside-outside design method that was exclusively suggested by the Royal Fine Arts Commission for designing in historical areas.

Their design strategy suggestion can fit with intervention actions like adaptive reuse or adaptation but cannot manage intensive ones like new additions, etc. Such idea resembles the widely criticized modernist notion that “form follows function.” In reality, certain functions have taken on the familiar forms of other functions without creating chaos in different contexts globally (e.g., some historic spiritual worship forms have been adapted for restaurant use while still keeping the original form unchanged). Drawing from the SWOT Analysis of the area, several studies, including ours, have highlighted that the design solution can embrace either of the two primary methodologies (inside-outside or outside-inside) or even a combination of both. This is what truly exemplifies the creative process of designing an appropriate place.

As a result, the essence of incorporating principles and elements of design when designing in historically significant areas arguably constitutes a key-point in the design scheme. Besides, fulfilling the set criteria of quality and relational indicators does not necessarily mean diluting the design solution for our historical precincts. In this regards, quality and relationship matters are compared from the perspective of conservation regulatory agencies’ principles ranking on design. Approximately 73% (b,l,m,k,s,g,i,j) of the guidelines criteria focus on quality aspects. Yet, 9% (p) of the guideline criteria ranking specifically emphasized relationships. At the center of the provisions, 18% (f,p) of them emphasized both quality and relationship.

When these interpretations are compared to the European Quality Principles, it becomes clear that two of the principles (Articles 17, 16) correspond to the second through third rankings given by the findings. Still, Article 19 corresponds to the sixth rank and simultaneously speaks to both quality and relationships. While two (Articles 15 and 18) of the principles, although necessary, were below the average benchmark set for analyzing the principles in this paper. The numerical limit and the methodical process differentiated this study from the previous studies of Naeem Abrar and Gizem Toprak who focus on only the conservation guidelines. Nevertheless, observing the results shows that the sixth rank is where the defining characteristics of new designs flesh out (see ); however, it is troubling that in some situations or new developments, the sixth rank guidelines criteria are occasionally disregarded or given less attention, which in turn compromises design creativity in terms of quality and relationship.

Based on this evidence and their interconnection, this study offers a further interpretation that the EU principles explicitly enhance quality as a central theme in this discourse, but the other theme of relationship aspects was given less attention. This interpretation is consistent with the current state of the conservation principles, as shown by the ranking of guideline criteria (see ). That uneven preference could contribute to the contention surrounding the outcome of the new architectural objects in historic precincts. Although these two terms possess a common root, their syntax differs. In the regulatory documents the keywords for quality are expressed as distinction, distinguishable, authenticity, identity, etc whereas relationship terms are reputed as compatibility, harmony, etc. Again, in the literature explored, only a few studies concentrated on quality (Abrar Citation2019; Khalaf Citation2016) and relationships (Khalaf Citation2016; Franco, Citation2016; Semary et al., Citation2016).

5. Conclusion

The goal of this paper was to explore conservation principles and the various design approaches employed for the coexistence of new designs and old architecture in historic precincts in order to develop enhanced policy and design tools. Based on this aim and objectives, it became clear that most past research arguing to classify design methods simply added more design types, except for the considerably preferred contextual approaches. The six-ranking system of regulatory guideline criteria showed the focus of conservation agencies on particular principles. These preferences heavily influenced the design process and final architectural outcomes in historic precincts when designers strictly adhered to them. As a result, the design approaches utilized by designers notably reacted to the guidelines established by regulatory bodies, supporting the existing historic image and its reflective features while disregarding current age values.

This paper introduced six novel design categories: indicative, reflective, selective-reflective, resiliency, progressive, and fashionista. These approaches contain several subcategories of design typologies (styles) based on their connections to each other and their visible properties. The policy-related and design-related tools established in this paper present promising prospects for vibrant outcomes for prospective designers, researchers, and other agents involved in managing historic precincts. They could help steer away from the current practice of only using contextual design strategies and creating false historic design expressions in future historic projects. Most crucially, these readily available policy and design tools should be incorporated at the preliminary stages of the design process to enhance new designs. This should interact with treating the historic precinct according to its character type, whether heterogeneous or homogeneous. Besides, regardless of the design approach utilized, favorable outcomes can be reasonably achieved when handled logically, as demonstrated in this paper and other successful projects.

These quality and relationship aspects brought about the formulation of three hypothetical statements:

Regulatory guideline criteria have a direct impact on the design approaches used for crafting new designs in historic precincts.

Design approaches are embedded with qualities that can be explored in various ways within a distinctive historical precinct. This allows the formation of a design dialogue between the new and old.

Specific design approaches are compatible with specific types of historic precincts and in contrast, certain design approaches can fit within all types of historic urban settings.

In view of these developments, the following suggestions have been made to both designers and other agents dealing with the management of historic precincts: 1) Urban development control units, antiquities departments, and other regulatory authorities based on the country’s by-laws should work together in the issuing of permissions and approvals to developers. Ensure new project proposals reflect quality and relationship aspects. 2) Architects should broaden their understanding of design approaches and carefully tailor them to the historic situation at hand while interacting with other available resources. 3) All sorts of interventions should target increasing layers of hierarchy for heterogeneous historical environments and maintaining ambiance for homogeneous contexts.

5.1. Limitations and future perspective of the study

This study limited text mining to 2021, which means all design typologies that appear after this time-frame are out of touch with the design categorization analyzed, assuming they present fresh design types. 25 International and National regulatory bodies were studied, and it did not isolate the national regulatory bodies from the international ones. The mean values used to analyze the preferential attitudes of regulatory bodies were another limitation of the study.

A future study can focus on analyzing how various design approaches and typologies have historically responded to changing times. The localization of conservation principles in the local context through the analysis of case studies. A comparative study of international and national regulatory bodies to identify their intersections and differences and develop more tools for coexisting, new and old. Implications of regulatory principles and design approaches on historic precincts’ historic identity. Interviewing designers of successful new designs in historic places to ascertain the type of principles followed and to measure their motivation for the design framework. Last but not least, testing the three hypotheses raised from the perspective of conservation principles and design approaches.

Competing Interest

We herewith declare that this research did not received any funding any sort. Therefore, there is no known conflict of interest with any organization.

Ethical approval and consent

Ethical approval is not required for this research because no human or animal participants were involved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ejeng Bassey Ukabi

Ejeng Bassey Ukabi is currently a lecturer at the Faculty of Architecture, Design and Fine Arts, Girne American University, North Cyprus, and a PhD candidate at the Department of Architecture, Near East University, North Cyprus. His research area connects architecture and urbanism-architecture as an interface, historic environment conservation, architecture in context, ideology and architecture, identity and spatial scalability.

Ayten Özsavaş Akçay

Ayten Özsavaş Akçay is an Associate Professor at the Department, of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture, Near East University. Her research fields include architectural identity, culture, new designs and extensions in historical environments, and the reuse of historical buildings.

References

- Abdel-Kader, Z. F. 2019. “Infill Design in Heritage Sites Study of Experts’ Preferences and Attitudes.” Journal of Engineering and Applied Science 66 (4): 451‒463.

- Abdelsalam, T. 2021. “New Architectural Intervention in Historically Sensitive Contexts: Humanistic Approach in Historic Cairo.” Journal of the Housing and Building National Research Center 17 (1): 41‒59. https://doi.org/10.1080/16874048.2020.1863745.

- Abdelwahab, M. 2018. A Reflexive Reading of Urban Space. New York: Routledge.

- Abrar, N. 2019. “Contemporary Architecture in Historical Context (Guidelines from Important International Charters).” In E-Proceedings –Space International Conference 2019 on Architectural Culture and Society, edited by G. K. Erk, K. Cengiz, M. E. Leary-Owhin. Docklands Academy London.

- Alderson, C. R. 2006. “Responding to Context: Changing Perspective on Appropriate Change in Historic Settings.” APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology 37 (4): 22‒33.

- Alfirevic, D., and S. S. Alfirevic. 2015. “Infill Architecture: Design Approaches for In-Between Buildings and “Bond” as Integrative Element.” Arhitektura i Urbanizam 41 (41): 24‒39. https://doi.org/10.5937/a-u0-8293.

- Allies, and M. Urban Practitioners. 2021.“'Citymakers-Pragmatics of the Picturesque: Observations on the Picturesque.' Talk, Organized in London.” https://www.alliesandmorrison.com/talks/citymakers-pragmatics-of-the-picturesque-observations-on-the-picturesque.

- Badalge, K. “A New Roof by Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos Turned This Ancient German Castle into an Enlarged Exhibition Space.” ArchDaily. Accessed April 9, 2018. https://www.archdaily.com/892010/a-new-roof-by-nieto-sobejano-arquitectos-turned-this-ancient-german-castle-into-an-enlarged-exhibition-space.

- Bakri, A. F., N. Q. Zaman, and H. Kamarudin. 2006. “Understanding Local Community and the Cultural Heritage Values at a World Heritage City: A Grounded Theory Approach.” IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science 1067 (1): 012006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1067/1/012006.

- Basarir, H., Y. Saifi, and S. Ö. Hoskara. 2016. “A Debate on the Top-Down Approach to Architectural Interventions in Conflicted Historic Cities: Jerusalem’s Museum of Tolerance.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 33 (3): 235‒250.

- Baytin, C. 2000. ““Architectural Concepts in the Design of New Buildings in Old areas.” [Mevcut Cevrelerde Yeni Yapi Tasariminda Mimari Yaklasimlar].” Yapi 229:51‒58.

- Baytin, C. 2003. “4 Cities + 4 New Buildings: Revitalization of Old Urban spaces.” [4 Kent + 4 Yeni Yapi: Eski Kent Mekanlarin Canlandirilmasi].” Mimarist 3 (10): 75‒79.

- Bekar, E. 2018. “The Design of New Buildings in Historical Urban Context: Formal Interpretation as a way of Transforming Architectural Elements of the Past.” Master’s thesis, Middle East Technical University.

- Birlik, S. 2013. “Design within the Historic Environment: A Survey on Administration Preferences.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 106:807‒813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.092.

- Blommaert, J. 2005. Discourse: A Critical Introduction, 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brolin, B. C. 1980. Architecture in Context: Fitting New Buildings with Old. Michigan: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Burtenshaw, D., M. Bateman, and G. J. Ashworth. 1991. The European City: A Western Perspective. London: David Fulton Publishers.

- Cantacuzino, S. 1994. “What Makes a Good Building? An Inquiry by Royal Fine Art Commission (RFAC).” In Urban Reader, edited by S. Tiesdell, M. Carmona, 18‒48. London: eBook.

- Carmona, M., T. Heath, T. Oc, and S. A. Tiesdell. 2003. Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design. 1st ed. Oxford, UK: Architectural Press.

- Charter, K. 2000. “Principles for Conservation and Restoration of Built Heritage.” Available from http://smartheritage.com/wpcontent/uploads/2015/03/KRAKOV-CHARTER-2000.pdf.

- Congress Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM). 1933. “La Charte d’Athenes or the Athens Charter, 1933.” In J. Tyrwhitt (Trans) 1946, Paris: The Library of the Graduate School of Design, Harvard University.

- Council of Europe. 1985. “Granada Convention‒Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe.” European Treaty Series. No. 121. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/second-european-conference-of-ministers-responsible-for-the-architectu/16808fde12.

- Davies, M. 2019. “Design in the Historic Environment. Cathedral Communications Limited.” Reproduced from the Building Conservation Directory, 2003 by Cathedral Communications Limited. Retrieved from https://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/design/design.htm.

- Demiri, K. 2013. “New Architecture as Infill in Historical Context.” Architecture & Urban Planning 7:44‒50. https://doi.org/10.7250/aup.2013.005.

- Designrulz. (2015). “Modern House in Vexin by Jean-Philippe Doré.” Designrulz. Retrieved from https://www.designrulz.com/design/2015/01/modern-house-vexin-jean-philippe-dore/.

- DHM/BerlinOnline. “German Historical Museum.” Accessed August 14, 2023https://www.berlin.de/en/museums/3109892-3104050germanhistoricalmuseum.en.html.

- Doratli, N. 2005. “Revitalizing Historic Urban Quarters: A Model for Determining the Most Relevant Strategic Approach.” European Planning Studies 13 (5): 749‒772. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310500139558.

- Dudzic-Gyurkovich, K. 2017. “Forming of Public Spaces of Lisbon: History and the Present Day.” Teka Komisji Urbanistyki I Architektury Pan Oddział W Krakowie XLV:387‒404.

- Eco, U., and G. de Michele, edited by 2005. Historia Piękna (History of Beauty), 415. Poznań: Rebis.

- Eleishe, A. M. 1994. “Contextualism in architecture: A comparative study of environmental perception.” PhD diss., The University of Michigan, pp. 63‒75.

- Elkad-Lehman, I., and H. Greensfeld. 2011. “Intertextuality as an Interpretative Method in Qualitative Research.” Narratives Inquiry 21 (2): 258‒275. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.21.2.05elk.

- Elsea, D . edited by. (2021, October 7) “Pragmatics of the Picturesque: Strategies for the Contemporary City”. CitymakersVol. 3. London: Allies and Morrison Urban Practitioners. Retrieved from https://user-volbuqj.cld.bz/CITYMAKERS-MAGAZINE-2021-FINAL-digital.

- European Environment Agency. 2021. Urban Sustainability: How Can Cities Become Sustainable? Retrieved from https://www.eea.europa.eu/downloads/ad534d6b69c849c7a6709b202cb44cca/1678887524/urban-sustainability.pdf.

- Fontana, L. 1946. Manifesto Blanco. White Manifesto). Milano: Galleria Appollinaire.

- Foucault, M. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge, 49. London: Tavistock.

- Franco, G. 2016. “'Contemporary Architecture in Historical Contexts: For a System of Values.'.” Techne 12: 182‒189.

- Furtak, M. 2015. ““Issues of the Central Industrial Industrial District Architecture” Conservation.” Teka Komisji Urbanistyki I Architektury Pan Oddział W Krakowie XLIII:39‒55.

- Gambassi, R. 2016. “Identity of Modern Architecture in Historical City Environments.” Architecture and Engineering 1 (2): 27‒42. https://doi.org/10.23968/2500-0055-2016-1-2-27-42.

- Getty Conservation Institute. (2013, May 21). “Minding the Gap: The Role of Contemporary Architecture in the Historic Environment.” Online Symposium. The J. Paul Getty Trust. Retrieved from https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/public_programs/conferences/minding_gap_sympos.html.

- Groat, L. N. 1988. “Contextual Compatibility in Architecture: An Issue of Personal Tastes?” In Environmental Aesthetics: Theory Research and Application, edited by J. Nasar, 228‒253. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511571213.023.

- Han, J. 2015. “Transformation of the Urban Tissue and Courtyard of Residential Architecture: With a Focus on the Discourses and Plans of Paris in the 20th Century.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 14 (2): 435‒442. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.14.435.

- Hawkins and Brown Architectural Firm. Plumstead Center. ArchDaily. Accessed September 21, 2021. https://www.archdaily.com/968792/plumstead-centre-hawkins-brown.

- Hodges, A. 2015. Intertextuality in Discourse. eds. Tannen, D, Heidi E. Hamilton, H. E.D, Schiffrin. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hunt, C. M., edited by 1996. Strategic Planning for Private Higher Education. New York: Haworth Press.

- Iamandi, C. 1997. “The Charters of Athens of 1931 and 1933: Coincidence, Controversy and Convergence.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 2 (1): 17‒28. https://doi.org/10.1179/135050397793138934.

- ICOMOS. 1931. “The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments.” Adopted at the First International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, Athens 1931. Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/en/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments.

- ICOMOS. 1965. “International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites.” (The Venice Charter 1964). 2nd International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, Venice, 1964. Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf.

- ICOMOS. 1972. “Resolutions of the Symposium on the Introduction of Contemporary Architecture into Ancient Groups of Buildings.” At the 3rd ICOMOS General Assembly. Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts/180-articles-en-francais/chartes-et-normes/383.

- ICOMOS. 1973. “Resolutions of the Symposium Devoted to the Study of the Streetscape in Historic Towns.” Lausanne. Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/publications/lausanne1973/lausanne1973-10.pdf.

- ICOMOS. 1975. “The Amsterdam Declaration- Congress on the European Architectural Heritage.” 21‒25 October 1975. France: ICOMOS. Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/en/and/169-the-declaration-of-amsterdam.

- ICOMOS. 1987. “Washington Charter‒ Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas.” Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/en/participer/179-articles-enfrancais/resources/charters-and-standards?start=22.

- ICOMOS. 2013. “The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance.” Australia ICOMOS, Australia. Retrieved from http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2145/.

- ICOMOS. 2017. “Delhi Declaration on Heritage and Democracy.” Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/GA2017_DelhiDeclaration_20180117_EN.pdf.

- ICOMOS. 2020. European Quality Principles for EU-Funded Interventions with Potential Impact Upon Cultural Heritage. France: ICOMOS.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation. (2021, July 22). “Conservation of Historic Environment.” Designing Buildings. Retrieved from https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Conservation_of_the_historic_environment.

- James, S. 1992. Architecture for a Changing World. London: Academy Editions.

- Japan experience. (2018, December 20). Historic Streetscapes Preservation Districts in Japan. Japan Experience. Retrieved from https://www.japan-experience.com/plan-your-trip/to-know/traveling-japan/preservation-areas.

- Jokilehto, J. 2007. “International Charters on Urban Conservation: Some Thoughts on the Principles Expressed in Current International Doctrine.” City & Time 3 (3): 2.

- Karimi, K., and N. Motamed 2003. “The Tale of Two Cities: Urban Planning of the City of Isfahan in the Past and Present.” Paper presented at the 4th International Symposium for Space Syntax, London, November 21-24.

- Khalaf, R. W. 2015. “The Reconciliation of Heritage Conservation and Development: The Success of Criteria in Guiding the Design and Assessment of Contemporary Interventions in Historic Places.” International Journal of Architectural Research 9 (1): 77‒92. https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v9i1.504.

- Khalaf, R. W. 2016. “Distinguishing New Architecture from Old.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 7 (4): 321‒339. https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2016.1252492.

- Kosiński, J. 2015. “A Showcase of the Ideas and Implementations in the Field of Historical Conservation Design in the 21st Century, Based on a Selection of Examples.” Teka Komisji Urbanistyki I Architektury Pan Oddział W Krakowie XLIII:167‒194.

- Łakomy, K. 2019. “Villa Architecture in Katowice After 1914 (Problems of Conservation, Modernisation and the Architectural and Landscape Context).” Teka Komisji Urbanistyki I Architektury Pan Oddział W Krakowie XLVII:297‒311.

- Lindman, Å. E. 2010.“'Moderna Museet Malmö / Tham & Videgård Arkitekter.'“ https://www.archdaily.com/55428/moderna-museet-malmo-tham-videgard-arkitekter.

- Manifesto, S. P. A. B. 1877. “The Manifesto of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.” London. Retrieved from https://www.spab.org.uk/about-us/spab-manifesto.

- May, N., and N. Griffiths. 2015. “Planning Responsible Retrofit of Traditional Buildings.” In Sustainable Traditional Buildings Alliances. UK: Jenny Searle Associates.

- Mehr, S. Y. 2019. “Analysis of 19th and 20th Century Conservation Key Theories in Relation to Contemporary Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings.” Heritage 2 (1): 920‒937. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2010061.

- Meinhold, B. 2011, March 06). “The Wheeler School Student Center is a Green-Roofed Glass Gem.” INHABITAT. Retrieved from https://inhabitat.com/the-wheeler-school-student-center-is-a-green-roofed-glass-gem/.

- Navickiené, E. 2012. “Infill Architecture: Chasing Changes of Attitudes in Conservation of Urban Heritage.” Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development, Barcelos: GreenLines Institute, Porto, June 19‒22.

- Norberg-Schulz, C. 1979. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. New York: Rizzoli International Publications.

- Norton, S. 2018. Heritage conservation and the building crafts: a Yorkshire case study. PhD diss., University of York.

- Pawlicki, B. M. 2015. “Differences in the Theory and Practice of the Preservation of Monuments and the Protection of Cultural Heritage Sites (100 Years of Zamość Protection).” Teka Komisji Urbanistyki I Architektury Pan Oddział W Krakowie XLIII:65‒81.

- Rahbarianyazd, R. 2017. “Sustainability in Historic Urban Environments: Effect of Gentrification in the Process of Sustainable Urban Revitalization.” Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs 1 (1): 1‒9. https://doi.org/10.25034/1761.1(1)1-9.

- Riza, M., and N. Doratli. 2015. “The Critical Lacuna Between New Contextually Juxtaposed and Freestyle Buildings in Historic Settings.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 32 (3): 234‒257.

- Rodwell, D. 2003. “Sustainability and the Holistic Approach to the Conservation of Historic Cities.” Journal of Architectural Conservation 9 (1): 58‒73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556207.2003.10785335.

- Rogers, R. 1988. “Belief in the Future is Rooted in the Memory of the Past.” Royal Society of Arts Journal 136 (5388): 873‒884.

- Rossi, A. 1982. The Architecture of the City. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

- Rowe, C., and F. Koetter. 1978. Collage City. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Ruskin, J. 1890. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Orpington: George Allen.

- Sachner, P. M. 1987. “Hansen House, Wilmette, III.” Architectural Record 175 (5): 104.

- Sanoff, H. 1988. “Residential Infill: A Fabric Design Strategy.” Architecture Australia 77 (1): 36‒39.

- Semary, Y. E., B. A. Kamel, and A. M. Amin. 2016. “'In Pursuit of Compatibility in Urban Context: An Analytical Study with Special References to Contemporary Local Contexts in Cairo.'” International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research 5 (10): 485‒494.

- Semes, S. W. 2007. “Sense of Place: Design Guidelines for New Construction in Historic Districts.” Philadelphia: Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia 1–53.

- Skerry, A. D. 2012. “Interpreting the standards: design professional and historicized design.” Master’s thesis, Roger Williams University.

- Smith, P. F. 1975. “Conservation Myths: “Facadism” Used to Be a Dirty Word.” Built Environment 1 (1): 77‒80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43456949.

- Sotoudeh, H., and W. Abdullah. 2013. “Contextual Preferences of Experts and Residents: Issue of Replication and Differentiation for New Infill Design in Urban Historical Context.” World Applied Sciences Journal 21 (9): 1276‒1282.

- Stavreva, B. 2017. “New vs Old: New Architecture of Purpose in Old Settings.” Master’s thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- Swensen, G. 2012. “Integration of Historic Fabric in New Urban Development—A Norwegian Case-Study.” Landscape and Urban Planning 107 (4): 380‒388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.07.006.

- Taher Tolou Del, M. S., B. Saleh Sedghpour, and S. Kamali Tabrizi. 2020. “The Semantic Conservation of Architectural Heritage: The Missing Values.” Heritage Science 8 (70): 1‒13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00416-w.

- Taraszkiewicz, L. 2002. “The Role of a Critic in the Dialogue Between History and the Present Day.” In MiastoHistoryczne w Dialogu ze Współczesnością, edited by J. Bogdanowski, 1–454. Gdańsk: Baltic Sea Cultural Centre.

- Tawab, A. A. 2014. New Urban Development and the Historic Environment. Deutschland: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- Tham and Videgard Architekter. 2010. “Tham & Videgård Moderna Museet Malmö.” Divisare Journal. https://divisare.com/projects/129616-Tham-Videg-rd-Arkitekter-Moderna-museet-Malm-.

- Tiedell, S., T. Oc, and T. Heath. 1996. Revitalizing Historic Urban Quarters. London: Architectural Press.

- Toprak, G. K. 2020. “A Guideline Proposal for Determining Design Criteria of New Building Designs in Historical Cities: ICOMOS and UNESCO.” Social Science Development Journal 5 (22): 95‒116. https://doi.org/10.31567/ssd.284.

- Toprak, G. K., and S. Sahil. 2019. “International Agreements on Designing New Buildings in Historic Cities.” Journal of Science, PART B: Art, Humanities, Design and Planning 7 (4): 471‒477.

- Ukabi, E. 2016. “Harnessing the Tension from Context-Duality in Historic Urban Environment.” Journal of Sustainable Development 9 (1): 77‒87. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v9n1p77.

- UNESCO. 1968. “Meeting of Expert’s to Co-Ordinate, with a View to Their International Adoption, Principles and Scientific, Technical and Legal Criteria Applicable to the Protection of Cultural Property, Monuments and Sites.” Paris: United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/archive/1968/shc-cs-27-7e.pdf.

- UNESCO. 1972. “Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage.” Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf.

- UNESCO. 1976. Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas. Nairobi. https://www.icomos.org/publications/93towns7o.pdf.

- UNESCO. 2005. “Vienna Memorandum on World Heritage and Contemporary Architecture–Managing the Historic Urban Landscape.” Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, World Heritage Centre. Retrieved from http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-47-2.pdf.

- UNESCO. 2011. “The UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Paris. Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2365#. Accessed November 20, 2021.

- Waterton, E., L. Smith, and G. Campbell. 2006. “The Utility of Discourse Analysis to Heritage Studies: The Burra Charter and Social Inclusion.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 12 (4): 339‒355. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250600727000.

- Węcławowicz-Gyurkovich, E. 2019. “Restored and New Market Halls in European Cities.” Teka Komisji Urbanistyki I Architektury Pan Oddział W Krakowie (Urbanity and Architecture Files) XLVII:51‒62.

- Yeomans, D. 1994. “Rehabilitation and Historic Preservation: A Comparison of British and American Approaches.” Town Planning Review 65 (2): 159‒178. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.65.2.28083u181mn1r121.

- Zonouz, H. K. 2018. “Partitioning (Facade) and Identity in the Historical Context Case of Zonouz City.” Journal of Sustainable Development 11 (6): 71‒81. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v11n6p70.