ABSTRACT

Social changes are reshaping play affordance patterns and redefining the concept of play space fences. This study explores this shift by examining four “childcare support bases” in Setagaya ward, Japan. We provided a historical overview of play affordances and explored how fences reflect the contemporary understanding of new play affordances. We categorized the play environment into new designated play spaces (NDPS) and carved-out play spaces (CPS). These were observed from the perspectives of both operators and users. We conducted four unstructured interviews to understand the operator’s viewpoint. From the user’s perspective, we interpreted fences perceived through social media phenomenologically, drawing on Merleau-Ponty’s concept of “perception through embodied experience.” The study sites in Setagaya ward encompass NDPS created and operated through new play affordances. Each NDPS forms a flexible cluster of play spaces by generating temporary CPS around it. Institutionalized play assistants facilitate an alliance between NDPS and CPS, acting as a non-physical fence permeable to the city and expandable through CPS. By reinterpreting fences in the context of new play affordances, we envision the integrated use of DPS and CPS in urban space planning, transcending the traditional conflict between them. This study offers a comprehensive examination of these concepts together.

1. Introduction

The play space in Setagaya ward, Tokyo, Japan serves as a network hub that guarantees the unity and welfare of the city while also suggesting a space formation method for a new city in which children are raised. Discussions on children’s play spaces thus far have criticized playgrounds, which are public spaces, specifying their overly detailed use and raising issues that their boundaries are too solid and closed off, thereby limiting free entry into and out of the city (Aitken Citation2005; Cunningham and Jones Citation1999; Kylin and Bodelius Citation2015). Studies have long been conducted with emphasis on urban forms that encourage children’s voluntary play and enable exploration away from isolated playgrounds (Chawla Citation2002; Frost Citation1992; Hart Citation1979; Jacobs Citation1961; Loebach and Cox Citation2020; Moore Citation1986; Tranter and Doyle Citation1996). Led by Frost (Citation1992), many researchers (Chatterton and Hollands Citation2002; Woolley Citation2007) have adopted the playscape concept and discussed the acceptability of play in the holistic urban environment. Researchers of urban space affordances argued the need for children’s free use of urban space by claiming unstructured free play in everyday life (Davison and Lawson Citation2006; Hart Citation1979; Heft Citation1989; Kyttä Citation2004). As an urban space that actualizes this theory, Jacobs (Citation1961) set the street as a play environment early on and noted the possibility of free and daily play. Aldo van Eyck scattered small playgrounds with weakened physical boundaries in various parts of the city and included them in everyday city life (Lefaivre Citation2007). He alleviated the age specificity of play equipment and designed it to embrace the affordances of citizens of various ages, blurring the physical boundaries between the city and play space. Scandinavian researchers including Fjørtoft and Sageie (Citation2000) thought that incorporating nature as a play environment into the city can destroy the boundaries of playgrounds and give freedom and abundance to children’s play (Bang, Braute, and Kohen Citation1989; Grahn Citation1991). They all suggested alleviating the physical fences of the play space and absorbing them into the city as a less structuralized space (Moore Citation1986; Nicholson Citation1971). They thought that this would increase the possibility of stimulating the creativity of urban residents, including children, by increasing the city’s play affordances and providing more chances for free play.

However, modern cities are gradually changing into a denser and more complex social and physical environment. Thus, the vision of children playing freely all over the city streets (Jacobs Citation1961) seems akin to an urban fantasy considering the increase in vehicles and pedestrian traffic as well as other nonsocial factors (Ball et al. Citation2004; Gill and Jack Citation2007; Jutras et al. Citation2003; McNeish and Roberts Citation1995; Moorcock Citation1998). According to Moore (Citation1989), fences are indispensable elements for children’s spaces along with carpets and kits. Fences originated for the purpose of protecting children from the city’s risk factors as well as the realistic intention to remove children from certain public spaces where they may be an inconvenience (Day and Wager Citation2010). However, Solomon (Citation2014) mentioned the renewed possibility of fences and emphasized the additional role of parents in children’s spaces while criticizing the Kit(play apparatus), Fence(boundary), and Carpet(floor) (KFC) formula mass-produced as a standardized environment that cannot provide freedom, which is the essence of play (Woolley Citation2008).

The recent diversification of local policy programs and the development of social media have replaced and dissolved physical fences by formalizing and specializing the role of parents in the play space. In a modern city, local policies and social media act as new play affordances, producing a new type of fence in the solid city and serving as a transformative force that changes the city. We observe the play space sets in Setagaya ward, Japan, as new play affordance settings and highlight the change of fences in the play space. The fence model, based on new play affordances, reveals that urban spaces are formed through human social activities. The transformative power of place based on urban ecology theory (Nassauer Citation2012) includes related systems, feedback loops, and spatial reflections as the keys to understanding the relationship between social programs and physical play spaces.

2. Methodology

This study aimed to advance existing theories on play spaces. Initially, our goal was to discover and define new forms of play spaces that ensure the safe control of children’s play. To achieve this, we conducted a theoretical analysis of the literature, which provided historical insights into the two primary contrasting perspectives on play control. Building on this analysis, we developed a new perspective.

The new perspective was validated through observations conducted at four play spaces in Setagaya, Japan. Data collection at the case sites involved a multifaceted approach, including the examination of government documents, field observations, unstructured interviews, and analysis of social media images. The documents referred to include the Tokyo government’s “Next Generation Fostering Support Measure Action Plan (2015–2024)” and Setagaya ward’s “Children’s Plan 2nd Period (2015–2024),” “Children and Childrearing Support Business Plan (2020–2024),” and “Outside Play Policy (2015 Onward).” Additionally, public reports, meeting minutes from various Setagaya ward divisions (such as the Urban Renewal Policy Department’s Urban Renewal Division, Children/Youth Department’s Children Division, Children/Youth Department’s Family Division, and Public Relations Division) as well as relevant documents and books were consulted.

Field observations were carried out in July 2018, during which we visited four new designated play spaces (NDPS) and 26 carved-out play spaces (CPS). The categorization of these two place-based concepts, NDPS and CPS, was supported by the analysis of 1,005 directly captured photographs, 21 drawings, and 48 sets of field notes.

Furthermore, we investigated both operators’ and users’ perception of play space fences. To gain insight into the operator’s perspective, we conducted four unstructured interviews with key stakeholders involved in shaping the play environment, including local authorities, educators, parents, and non-profit organizations. Three of these interviews were conducted in person, while one was carried out via phone. To understand the user’s viewpoint, we employed phenomenological analysis techniques to interpret their perceptions of the fences. This interpretation drew upon Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s concept of “perception through embodied experience” in the context of new play affordances, focusing on the role of social media in the contemporary city. Through the phenomenological interpretation of the fences of study sites visualized through the lens of social media, user perception of these fences can be understood.

3. New-play affordance in the city

3.1. Acquisition of play in a new-play affordance city

Architectural environment researchers occasionally use “affordances” to refer to an individual’s physical, social, technological, or behavioral dependence on the environment (Voorhees et al. Citation2013). In particular, they limit the term to “play affordances” with a focus on play, which is universal among young children before they reach adolescence (Clerkin and Gilligan Citation2018). “affordances” are the essence of ecological psychology, defined as physical opportunities and risks perceived by organisms when acting in a certain environment (Gibson Citation2014; Heft Citation1997). According to Gibson (Citation1979), the affordances of a place allow individuals to weigh the possible actions there and the consequences of those actions. However, Gibson’s opinion connotes the danger of presuming that the individual is a passive receiver of the environment. In this regard, Kyttä (Citation2002) distinguishes “actualized” from “potential” affordances in the environment (Heft Citation1989) in which an individual perceives, utilizes, or shapes the affordances. According to these researchers, the potential affordances inherent in the environment are infinite, but only some are revealed depending on individual abilities and capabilities. Benjamin (Citation1986) also stated that how a place is perceived in a particular situation or environment depends on differences in cultural values and attached importance to the social ecosystem surrounding the place. This socioecological approach (Bronfenbrenner and Evans Citation2000) can help understand new play affordances according to changes in modern society.

Smartphones and social media have dramatically increased the ability to acquire and produce information specific to individual situations. Therefore, play affordances of individuals vary depending on their ability to acquire information about play and places that accommodate it. Considering that children’s play occurs under excessive parental supervision and that play in a place controlled by fences is negatively perceived (Solomon Citation2014), new play affordances may contribute significantly to research on play affordances for both children and their parents or guardians. Developmental science in the late 1990s raised the need to discuss individual functioning that responds to the physical environment at multiple levels, from inborn heredity to social networks, community, and culture (Cairns, Jane Costello, and Elder Citation1996). New information acquisition methods of modern society and the institutional support of each community are influential resources that affect the play area choices and play behaviors of parents and children. New play affordances are differentiated from conventional play affordances due to the dominant role of social media that affects the guardian’s interpretation of the physical environment as well as the institutional differences of individual communities.

3.2. Play provision in a new-play affordance city

New play affordances have also changed the way in which play is provided in the city. Both the interactive communication method of social media and the meticulous policy program in the region have become new-play affordances, thereby supplying a new fence to enable play in the city. Until now, cities have been classified by overly specified functions, and children’s play spaces were no different. Changes in the socioeconomic structure since the Industrial Revolution sectionalized land use and defined the use of facilities (Woolley Citation2007). Haydn and Temel (Citation2006) stated that mono-functional, static spaces were planned for the capitalist economy to maintain the city as a product. This idea categorized the division of not only space but also the human life cycle into numbers. According to Olwig and Gulløv (Citation2003), the “Child Employment Act” (Heseltine and Holborn Citation1987) stipulates that childhood is a stage that is clearly separate in an individual’s life. In addition, special places were to be planned to accommodate this distinct age group, and above all, the need to protect children from the dangers of industrialization led society to strengthen the social and spatial separation of children (Kinchin and O’Connor Citation2012). By arranging places in fixed locations with predetermined goals, programs, and organizational structures, the concepts of childhood and adulthood were structuralized in urban space. Children are separated in the “archipelago of normalized enclosures” (Stavrides Citation2015), and playgrounds have represented the urban spaces that embody such heterogeneous spatiality. Not only the structures (traffic and facilities) of adult cities but also social fears such as crimes, bullying, and deviance (McNeish and Roberts Citation1995) have become reasons for the strong control over children in the city. In particular, the development of media contributed to the moral panic of parents (Valentine Citation1997) by easily providing information about various social risks, increasing the possibility of adults underestimating children’s ability to manage their own safety.

This phenomenon strengthened the perceived need for the separation of play spaces with fences but, at the same time, resulted in strong resistance (Atmakur-Javdekar Citation2016; Carroll et al. Citation2019; Cunningham and Jones Citation1999; Jacobs Citation1961; Matthews Citation1995; Thomson Citation2003, Citation2005; Woolley Citation2007). Many researchers studied play in CPS or “non-designated spaces” away from official playgrounds (Beazley Citation2000; Hill and Tisdall Citation2014; Matthews, Limb, and Taylor Citation2004; Rasmussen Citation2004), and others took a holistic approach to play and the city by referring to the city as a playscape (Chatterton and Hollands Citation2002; Woolley Citation2007). Gospodini and Galani (Citation2006) analyzed spaces where children can find “affordances” as the possibility of play, although not especially designed for children, in order to analyze play in urban spaces aside from specific play facilities (Gibson Citation1979). On the other hand, adventure playgrounds in the UK have introduced play leaders that are trained as childcare teachers as a social element that strengthens the fences of play spaces, starting with the Emdrup Junk Playground in 1943 (Allen Citation1968). This approach has been widespread in areas with playgrounds where parents and residents already have strong ties and can voluntarily participate in operation. However, the number of adventure playgrounds with such a bottom-up utopian ideal decreased rapidly, inevitably handing over the status as the mainstream urban play space to equipment playgrounds formalized with fences and play equipment. Nonetheless, the increasing concerns over children’s safety in modern society and the related social systems that are becoming more compact accordingly as well as the emergence of social media have shed new light on the importance and sustainability of the role of the “play leader and supporting committee” of the past.

Fences that seem incompatible with the attributes of free play are being disrupted and changed by new play affordances. Social media, a product of modern technology, enables the participation of diverse groups by allowing immediate and interactive communication. Moreover, play-based social programs operate as a public policy that helps promote and organize play from a comprehensive policy perspective, including childcare, leisure, and education. As such, these new social conditions serve as play affordances, keeping play from being neglected while also not being confined to a specific place.

3.3. Urban play space sets: new designated play spaces (NDPS) and carved-out play spaces (CPS)

Established research and assertion on the value of CPS, where free play in everyday life is possible, led to a misunderstanding and criticism of DPS with fences. Maxey (Citation1999) referred to the playground as a typical DPS, “a place where children can play and be safe under the control of regulations and surveillance of adult eyes and cameras.” On the other hand, Opie and Opie (Citation1969) observed children playing in various spaces and expanded the concept of the play space to “where children are is where they play.” Later, various other studies focused on the diverse spaces of the architectural environment for children, that is, CPS (Christensen and O’Brien Citation2003; Cunningham and Jones Citation1999; Hart Citation1979; McKendrick Citation2000; Moore Citation1986; Woolley Citation2007).

However, risk-averse societies (Gill and Jack Citation2007) generated fear for children’s safety in parents (Jutras et al. Citation2003), fear of litigation in providers (Moorcock Citation1998), and fear of accidents and risks (Ball et al. Citation2004), resulting in hesitation about changes in DPS that still guarantees safety. “Risk-taking is an essential feature of play provision” (Play Safety Forum 2002), but it is even more essential to safely protect children. Thus, the opinion that fences are important as an archetypal element of the play space and must be reinterpreted in the context of social change is convincing. McKendrick (Citation1999) questioned the social attitude that children should play in DPS. He claimed that providing a “standardized playscape in a similar environment” is self-righteous, lacking the participation of children and the extensive cultural expression of childhood, and stated that DPS can become creative and flexible, moving beyond standard and uniform, by having children participate in the generation of a playscape. Moreover, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) interprets the fence as the support, guidance, or supervision of adults in the process of determining how lottery proceeds must be used for play in the UK. The DCMS defines play as “what children do when they naturally follow their own ideas and interests,” claiming that play is an activity led by children but that at the same time, the role of adults may help provide the most successful play (DCMS Citation2003). This leads to the debate about free play and directed play. According to Moyles et al. (Citation1989), free play is related to opportunities in the environment where one can explore and investigate the materials and situations for oneself, whereas directed play is related to a specific environment in which adults tell children what to do with available materials. Moyles suggests that there may be play spirals that return to more abundant free play, inspired by directed play. Therefore, the city’s play environment must consider spaces that can embrace both free play and directed play at the same time.

In this study, DPS are defined as officially controlled play spaces enclosed by fences that are established to ensure children’s safety during play. CPS represent everyday urban spaces run by variety of operators that offer the potential for children’s play but are generally non-designated and formed temporarily. They offer the possibility of a wide range of play rather than using a designed apparatus. NDPS, on the other hand, can be defined as DPS that have been transformed or newly created and derive CPS around them due to the influence of social media and play-based social programs, as previously mentioned, as a new play affordance in contemporary urban settings.

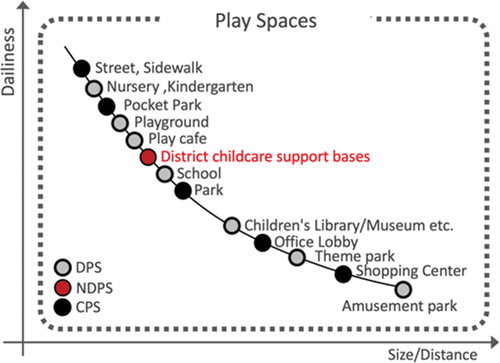

classifies play spaces into DPS, NDPS, and CPS based on Park’s (Citation2019) list of play spaces.

We observed the DPS distributed in Setagaya ward, among which those deriving CPS due to new play affordances were classified as NDPS. Four study sites enclosed by physical fences were selected as examples of NDPS, generating 26 CPS. In this research, NDPS and CPS are discussed as emerging forms of contemporary urban spaces that collaborate to establish a perceptual play enclosure.

4. Fences around the play space sets in Setagaya ward, Japan

4.1. Research sites as NDPS from the perspective of the operator

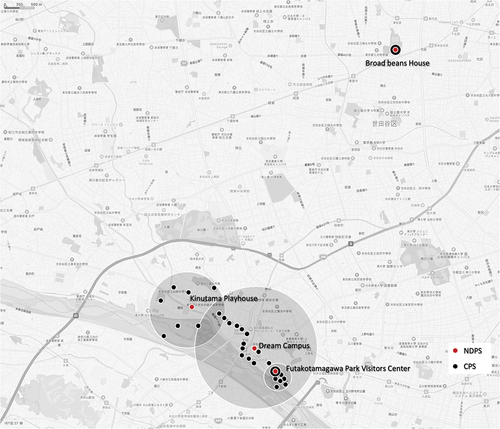

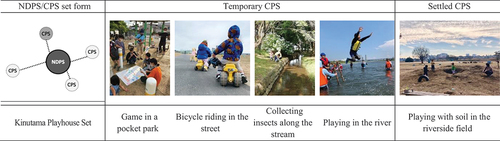

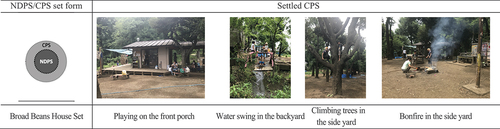

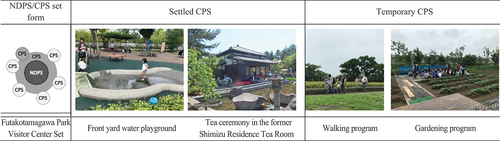

This study attempts to understand the play fences newly revealed in the city of Setagaya ward, Japan, through the cases of four district childcare support bases. Kinutama Playhouse, Broad Beans House, Futakotamagawa Park Visitors’ Center, and Dream Campus can be considered NDPS designated by the community. They operate CPS discovered in neighboring cities. shows the sites divided into NDPS and CPS. summarizes the operating subjects, activity spaces, and actions of the sites. From the perspective of various operating subjects, identifying the play space perceived by them is significant, as it defines its character and helps access the position of that space in the existing playground genealogy.

Table I. Operating subjects and play programs of NDPS/CPS sets in Setagaya ward.

Each play space is operated with the support of the local government and residents as well as multiple entities such as nonprofit organizations, nearby universities, and private companies that play active roles in collaboration. The various entities provide a wide spectrum of play, from special to free play, by planning, running, managing, or funding programs. The research sites can be considered the official city DPS that receive policy support from the public sector (government/local governments). In this respect, they are different from traditional DPS.

According to Sachiko Uehara, a representative of the Waterside Design Network, a non-profit corporation that runs Kinutama Playhouse, one of the four research cases, “We support local children and parents being embraced by the community. Therefore, we collaborate with everyone. While operating regular, stable indoor programs for children and adults indoors, we create adventurous small playgrounds in the surrounding outdoor space. It is more enjoyable because it is created by different opinions; it is ephemeral and unpredictable. This place provides an opportunity to experience more urban spaces as play. Moreover, there are not many complaints from nearby residents, as the play does not take place continuously in one place.” In her opinion, the site meets the stability of indoor spaces and the activity of outdoor spaces and provides the possibility of designated and free play. It is interpreted as a new play space in the city that can accommodate various types of play (Loebach and Cox Citation2020) that often struggle to coexist in the same space.

Furthermore, according to Professor Mari Yoshinaga of Showa Women’s University, chairperson of the Setagaya ward’s Play Outside Policy Committee (since 2015), “Although the contribution of sites to social connection is very high, it is evaluated that the ability to control the play space can be higher than that of the traditional playgrounds. To support outdoor play in a dense city, a new playground should be created. District childcare support bases (see ) can act as a playground. However, their role is different from the previous playgrounds, as they are more controlled and more actively connected to the cities and children.” As she mentioned, the four sites are different from the spaces we have defined as DPS in the past. Although the contribution of the sites to social connection is higher than before, the ability to control the play spaces can be higher than that of the previous DPS’s fence.

Figure 3. Diagram of the children and caregiver support system, utilizing both DPS and CPS as interactive local spots for comprehensive care at the community level; refer to Setagaya ward children’s plan (phase 2) report (Setagaya Ward Citation2015b).

According to Fujita, a parent of a third grader at Futako Tamagawa Elementary School, who volunteers at Dream Campus, one of the four sites, “This is a play base. We meet people here and see the kids play. When there is an event planned by us nearby, we go there, and the children play there too. If you spread event information on social media, urban spaces quickly become playgrounds … Moreover, when my child participates in program development as a volunteer, they get points from the school.”

Sites serve as independent play spaces; additionally, they are discussion hubs that temporarily insert play programs by discovering CPS nearby, flexibly expanding the zone for play. Moreover, it can be inferred that the institutional device that encourages participation also plays the role of play affordance in this city.

According to Nawa, Setagaya ward’s Urban Renewal Policy Department, “In urban renewal projects, links are currently strengthening with children-related departments, such as the Children/Youth Department’s Children, Family, and Public Relations Divisions. Each department plans various programs and promotes them through social media to attract public participation. This can lead to interest in urban space from many ages.”

Establishing a closer relationship between children and the city can increase interest in urban spaces among child-rearing community members and young people, suggesting a new role for the social system and social media as play affordances.

4.2. Observation of the fences in the research site as a set of NDPS/CPS

4.2.1. Fences of research sites revealed in policy

The policy of Setagaya ward reveals an environment for children that includes the concept of play assistances as an interactive care tool that is closest to local residents. By providing NDPS planned by policies and forming resident participation, Setagaya ward provides an expandable play space that is likely to create a new regional policy and urban space. The system in which residents can act as the region’s play space providers themselves enables top-down and bottom-up interactive play provision, thereby promoting social and physical changes in the city.

The guidelines for creating play spaces for children appearing in Setagaya ward’s laws and within the local government’s housing development regulations indicate a change toward an interactive provision of recipients and providers (Davison and Lawson Citation2006) and provide the basis for residents to evaluate the environment themselves by creating the “City Evaluation Criteria to Make Children Healthy” (Senda Citation2016). Moreover, the local government council is actively expanding the movement to legislate the ordinance for children’s play space and supporting an interactive play space provision model within the Landscape Act or the policy system. Setagaya ward’s “Action plan to support raising the next generation” classifies the beneficiaries by age from the unborn to adults aged 39 and directs that conceiving and caring for them are to be included in the children’s environment policy. These developments provide detailed guidelines, perceiving children’s environment not just as being for children of certain ages but as a base that forms a local fence that is free of alienation and where safety is guaranteed. The plan includes instructions on how to utilize local facilities for the childcare community at the village level. The outdoor play policy presents ways to form the childcare community around the play base and utilize the urban space for play (Setagaya Ward Citation2015a). Here, social media and platforms providing play information provide individualized and optimized play space options as new play affordances of the modern city that form the basis of the outdoor play policy and even share the spaces experienced, thereby discovering and developing new urban spaces for play. This study focuses on NDPS as the local base that provides play in the region based on such new play affordance resources. DPS, which had been symbolized by a closed fence that separated children from the city in the past, is now changing into spaces for participatory observation.

Through , it is possible to estimate the new role of DPS pursued by the urban policy of Setagaya ward. Traditional DPS at the closest level, such as playgrounds, nurseries, kindergartens, and schools, have been transformed into bases for local welfare policies and provide welfare services related to various play programs. A new base of play (new BOP) and regional conference room were established within the facility, and the infirmary was transformed into a place for flexible play, allowing local residents to plan and provide programs. In addition, a separate children’s center was established to lead local children’s policies (Yoshinaga, Kinoshita, and Terauchi Citation2009). Moreover, the play bases of the district are more compactly inserted through a relief hut and parenting salon/plaza serving as a regional childcare support base. These places serve as play generators that generate various other play spaces in the district in association with the public government and nonprofit organizations based on new play affordances. At the same time, they form the fences of the epistemic community (Thurmaier and Wood Citation2002) by providing programs mediated by play, such as counseling, childcare, lecture, dining, publicity, and local product sales ().

4.2.2. Fences of research sites exposed on social media

Social media is becoming the play affordance of the modern era. Through the phenomenological interpretation of the fences of research sites visualized through the lens of social media, user perception of those fences can be understood. The city’s various spaces allowed children’s play to be revealed through representations on social media, which are reproduced by operators and guardians of children. If empiricists see that raw sensory materials exist outside of us and we passively accept them, Merleau-Ponty’s (Citation2004) concept of “Perception through embodied experience” suggests that our perceptions actively form, signify, and interact with the objects. It was seen that he interacted with the objects while shaping and signifying them. As our body is not a neutral machine, even a single vision does not grasp the character of a pure object but already gives meaning. For example, a non-moving wheel on the ground and a moving wheel, a body at rest and a body tensed up, all have different meanings despite being the same visual object. Things that were considered objective properties have different meanings and values in the experience of perception. This meaning shows that perception has a close relationship with one’s personal history.

The fences of the four research sites as NDPS seem clear (). However, NDPS reproduced through social media expands the viewer’s perception beyond the fence. Concomitantly, the fence perceived by the subject who captures it as an image and reproduces it on social media also seems faint. The images capturing various CPS and the text displaying information, such as their place and time, are listed on social media with the image of NDPS, dissolving the fence of NDPS in the perception of the viewer.

Figure 5. The fence of NDPS revealed on SNS; from the left, Kinutama Playhouse (facebook.com/kinutama.asobimura), Broad Beans House (facebook.com/Playpark.Setagaya/photos/4823699877671859), Futakotamagawa Park Visitor center (twitter.com/yumecampus_tcu), and dream campus (instagram.com/p/CiMp69MpuaI/).

On social media, the Futakotamagawa Park Visitors’ Center is fragmented with scenes of various CPS and play activities, such as play program meetings in the indoor standing space, rest and classes in the indoor seating area, observation of organisms in rotten trees on the concrete floor in front of the building, and water play in nearby green spaces. Then, they are reproduced as a new image for the viewer (). In addition, informational texts and imaged program introductions provide objectified information so that various spaces in the city can be accessed as play. The viewer perceives the image as “Perception through embodied experience” by imagining and interpreting images in combination based on their experiences (about the place and action revealed). The fragmented release of urban space and play information on social media makes it possible for the viewer to rearrange the space as a sequence of selective combinations, away from accepting the space as a designated unit. Therefore, each subject, a guardian accompanied by a child, interprets and selects images provided based on personal experience, participates in physical space, and represents the experience on social media again. Through this, children and guardians can experience transformative power (Sarkar Citation2014) as beneficiaries and producers of social media and achieve imagination and realization of new urban spaces.

5. Interpreting the fence of NDPS/CPS sets

5.1. Formalizing the role of “parents” as the social fence

NDPS in Setagaya, Japan, bring the voluntary participation pursued by adventure playgrounds of the UK into the policy system and formalize “implicit activism,” revealing the potential for a new social fence in the city. According to Horton and Krafti (Citation2009), securing a safe play space in the city can be seen as a clear manifestation of “implicit activism,” which is a “small scale, personal” behavior rooted in “everyday practices.” It often stems from household experiences involving childcare, food, and housing (Jupp Citation2017). Considering the influence of social media mentioned by Tayebi (Citation2013) and Douglas (Citation2012), social media and new systems can be seen to exert influence over the implicit activism of parents and affect daily play and urban design. The NDPS observed in Setagaya are spaces where implicit activism is manifested, and the parents’ involvement in children’s play space is included as a peripheral actor of public management network models (Thurmaier and Wood Citation2002). This officially stipulates the existence of guardians in the play space and not just as the biological parents of children. Thus, “parents” as the social fence are specified as play assistances that substitute parents; the social network comprised of public officials, experts, local residents, guardians, and the social programs produced also belong to the broad category of “parents.” This concept is different from the playworker that was present in the UK over 60 years ago. While a playworker was “someone who helps create a space where all children and adolescents can play” (PPSG Citation2005), “parents” are play assistants who guide children, coordinate play with others, and protect them. This has now established itself as a specialized policy system with new play affordances (). Therefore, the public sector (central/local governments) can change the method of providing and utilizing play in the city, and it adequately unites and manages groups by acknowledging, reinterpreting, and formalizing the existence of parents in the play space.

5.2. The permissive fence of NDPS as a discussion place

Social media provides a foundation for dismantling and reconstructing the traditional fences of the play space by changing the way children perceive, play, and reimagine urban places. On the premise of smooth interactive communication in modern society, the public sector (central and local governments) strives to ensure the diversity of play spaces by planning the urban play space as a social welfare system instead of serving only as a provider of the prescribed play spaces. NDPS provided this way serves as a play space by itself as well as a place for discussion that creates the basis for providing various play programs and new spaces in the city at the same time. Kinutama Playhouse, Broad Beans House, Futakotamagawa Park Visitor Center, and Dream Campus are the district childcare support bases () that constitute the region’s type closest NDPS. They are play spaces that are maintained with public support, operation of nonprofit organizations, and resident cooperation, and they unite the community by providing play to the region, supporting play assistants, and operating play-based programs (NPO Kinuta Tamagawa Play Village Citation2017).

Unlike DPS, NDPS are Lefebvre-style spaces that embrace various social dynamics by providing an indefinite indoor space. The spaces of the research sites are spaces where the building type is not determined and thus are not limited to place but freely accommodated by the region, thereby easily disturbing stability and creating change (). While the existing DPS is a “conceived space” that is specialized, instrumental, clearly aesthetic, and separated from the city using a fence, NDPS observed in Setagaya ward are integrated spaces. Lefebvre theorizes space with a dialectic (triple dialectic) between three different forces in The Production of Space in 1991 (Lefebvre Citation2014). The first force is what he refers to as “conceived space,” which is the power play of capital and the state. The second is “lived space,” which is the desire, dream, and memory of the residents. The third force is “perceived space,” which is how residents actually use the space. In other words, what Lefebvre refers to as space is the dynamics between top-down planning, bottom-up experience, and the negotiations between them. As in Marxist dialectics with a conflicting thesis, Lefebvre’s image of space also has forces that constantly move, fight, dominate, subjugate, deny, and turn the struggles into synthesis. Therefore, what Lefebvre refers to as space is characterized by constant social dynamism.

Figure 7. Spaces not regulated as a specific building type: Kinutama Playhouse (local housing rental), Broad Bean House (temporary building), dream campus (office unit rental), Futakotamagawa Park Visitor center (independent building).

The cases of Setagaya embrace what Lefebvre refers to as social dynamics by attending to the implicit spatial rules that constitute play, which is a human activity that is often overlooked within the social context as NDPS. NDPS weakens the fence, which is one of an archetypal elements of playgrounds represented by KFC (Woolley Citation2008) so that they smoothly permeate into the city, and then formalizes the existence of parents criticized by Solomon (Citation2014) instead, thereby increasing the diversity and control of play. Through this, the original role of play for children was not weakened while making play a basis for community solidarity and the utilization of urban space in a changing society. The weakened KFC and formalized “parents” allowed NDPS to be free, without place constraints. These “parents” operate and expand space as officially commissioned play assistants as well as social programs. Flat, clean floors where children can lie down or play, movable teaching aids, and simple play furniture are common spatial elements revealed in many NDPS, showing the minimum physical space composition for play while also not limiting the users of space to specific ages. Each case of NDPS found in Setagaya can be seen as a multipurpose space publicized on social networks and operated by the “parents.” Although these spaces state the official use as “play,” the physical forms of the fences are different.

The Kinutama Playhouse is like a playroom in any other family home. This case shows the everyday fence in which play is accepted. Kinutama Playhouse, which operates by renting a general house, surrounds the wide central floor with low bookshelves laid out along the walls as well as play furniture and piles of teaching aids to define the inner space as play. The low-height furniture and teaching aids that surround the space are the closest fence that limits the space where children in early childhood can play. Conversely, Broad Beans House is a temporary structure that assists the adventure playground located in the park, and the fence itself serves as play equipment. Swings, slides, water swings, stairs, wheelchair ramps, and porches surrounding the boundary of the playhouse and attached to the building are occasionally replaced with new ones and turn the entire building into play equipment. Here, the building’s boundary is not a fence that limits activities but a physical medium that allows children to start their first adventure outside the surroundings. The Futakotamagawa Park Visitor Center connects the redevelopment site on the third level and the park on the first level, thereby connecting the boundaries of the two areas with play and rest. The fence of this play space selectively internalizes outdoor play by being completely open to the surrounding land. The third level faces the pedestrian plaza of the redevelopment site, serving as a rest area that is accessible to the public, and the first level is wide open to a children’s playground in the park on the opposite side, connecting the playground to the inner floor where shoes are taken off. This variable fence allows the architectural space to function as a shelter and playground that increases the continuity of young children’s outdoor play. Next, Dream Campus is a play-based social network field located in a high-rise office unit in a high-density development complex downtown. Only the colorful chairs placed in the vast open plan space inside reveal that this space is not an ordinary office but a play space. The downtown office provides a projective fence that views the city from above, which has never been experienced by children in the city before. The projective cladding of the façade that blurs the boundary of space provides the thrill and spectacles of a bird’s-eye view and allows children to estimate the physical form of the city ().

Figure 8. Various fences of NDPS: (from the left) fence as low play furniture/teaching aids in Kinutama Playhouse, fence as play equipment in Broad Beans House, variable fence at Futakotamagawa Park Visitor center, and projective fence overlooking the city at dream campus.

There were no formal constraints on the shape of the NDPS fence revealed through observation. Therefore, children’s space could freely permeate into adults’ space in the city without being restricted to a specific facility category. The physical fence of NDPS freely and safely sets boundaries from the outside in various forms without a certain prototype; thus, children are provided with an environment where they can communicate with the world and experience social dynamics through NDPS. At the same time, NDPS is becoming a permissive fence that provides the opportunity for adults to enter the children’s world. Various facilities of the city that had been forbidden to children before are now open to them through NDPS.

5.3. The expandable fence of CPS as a testing ground

NDPS not only encourages children’s exposure to various social programs as a playground where play assistants are present at all times but also serves as a permissive fence that more extensively allows children’s use of urban space. It provides an opportunity for all local residents as well as children and caregivers to think about and practice ways to use and manage urban space by generating temporary CPS nearby. Based on the concept of a “temporary autonomous zone” formulated by Bey (Citation1991), Harvie (Citation2013) explains that the urban possibility of temporary occurrence socially connotes micro-utopian potential. Temporary occurrence is a method that can politically intervene in the way people see and experience the world, and it refers to a temporary, tactical, multiplex, decentralized, and creative intervention. The temporary activity places of the city contribute to the expansion of play in the city by becoming a testing and production ground that challenges existing structures and customs and encourages the emergence of alternatives. At the same time, the liberating potential of play is increasingly expanding its influence in urban discourse about temporary occurrence (Mariani and Enrico Citation2014). In an article, Ohnishi and Yoshinaga (Citation2017) suggested that the temporary play space contributes to local space production as a testing ground for outdoor play as well as a community-based participatory research field. The aforementioned cases of the four play space sets in Setagaya confirm the possibility of places for play in the city and expand the realm of play by discovering CPS based on NDPS and generating temporary play.

Social media enables an impromptu and temporary play provision model by connecting users with CPS that appear in a guerrilla format without a fixed time and place. The four cases of Setagaya show different expansion patterns of CPS within the city derived from NDPS (). In the case of Kinutama Playhouse, CPS is mostly formed by the waterside due to the rare regionality that has served as a waterside amusement park for Tokyo residents for a long time as it is adjacent to the Tama River. Play assistants consisting of NPO corporation Kinuta and Tama River Play Village, parents of local elementary schools, and researchers from local universities use NDPS as a base to discover nearby CPS. CPS gradually penetrates into various spaces of the city in spots such as wild waterfront spaces and wetlands, nearby kindergarten yards, pocket parks, and streets. CPS mostly occur on the pedestrian-accessible streets of NDPS, function temporarily, and then disappear, but some continue to exist, providing more lasting transformations to the city. Pits for campfires formed in riverside fields, floor mounding for play, and flat leveled floors are types of settled CPS. Settled CPS is a new space produced in a way different than before in the city by serving as an independent play space ().

Figure 9. NDPS-based CPS distribution pattern.

Broad Beans House, located in a large park, becomes a play structure by itself and expands CPS to the surrounding space in terms of face. It is a 20-m2 playhouse in Japan’s first-generation adventure playground located in Hanegi Play Park (Sakamoto Citation2017), which was the epitome of an anarchist temporary playground. It has maintained the typicality of an adventure playground as a children’s space, encouraging adventurous outdoor play by using an indoor base and external boundary spaces. However, the typicality of children’s space is weakened by the new play affordances of modern society, and it is turning into a place for exchange and the integration of multiple generations. Based on new play affordances, Play Park Setagaya, which is a nonprofit organization active in Setagaya, has begun to play an active role, and this space is being reproduced, expanded to other regions, and officially operated as a local community space in collaboration with the local government. The relationship between NDPS and CPS revealed through the Broad Beans House is not only the physical conditions of the architectural boundary that accommodates play but also the active use of SNS to help connect users with social programs. The porches and decks surrounding the four sides of the building connect the outside to the inside, allowing children to experience adventurous play without breaking away from the boundaries of the building; thus, it is suitable for even young children that have difficulty with voluntary action to participate in play. Social media serves as a window for individuals of various ages to gain the opportunity to participate in children’s play, which facilitates the maintenance and utilization of NDPS/CPS. Eyck et al. (Citation2008) explained that the boundary of a house is the “in-between” point, where children first encounter the world, and emphasized that the city’s potential for change starts from that point. Broad Beans House replicates the in-between point provided by children’s homes in urban space and expands children’s activity area to the outside world. CPS revealed here is a manifestation of in-between that blurs the boundaries between architecture and city. At the same time, new NDPS/CPS sets are replicated in other regions and expanded in certain spots ().

Futakotamagawa Park Visitor Center () is a visitor facility and play shelter in a large, resident-participatory municipal park run by the local government, and it integrates the entire walking space with play. Like Broad Beans House, it is a facility within a large park and has the form of CPS expanded in terms of face from the boundary of NDPS. However, the visitor center is not typical of a children’s play facility, as its name suggests. The entire park is selectively operated as CPS that citizens of all ages can enjoy through the operating method that involves resident participation. Residents regularly hold meetings at the visitor center and plan and experiment with various social programs in the park. Play assistants who stay there permanently plan resident participation and operate, promote, and manage the selected programs but do not go out to the city to discover or create new play spaces as in the case of Kinutama. Resident participation experiments are repeated to change this park that is already elaborately provided into a better space that meets the needs of the community. The abundant outdoor spaces, such as the plaza, rooftop garden, and planned landscape area connected to the visitor center by pathways, are experiments as background spaces for new play-based social programs through which the form of a park suitable for the community is discovered.

Dream Campus () is a branch campus of Tokyo City University and is located in an office unit of a large-scale redevelopment complex. The large pedestrian plaza or event hall in the district is used as CPS. Due to the nature of the location, there are various large-scale attractive spaces nearby connected by walking. Thus, there is a greater variety of programs that can be accommodated by CPS compared to the previous cases. At the same time, CPS are found throughout the city regardless of the distance from NDPS, which is related to the influence of the operating body as well as the highly attractive location of NDPS. Dream Campus is a base for regional participation event projects for which Tokyo City University serves as a play assistant, and it is a place that extensively supports education and research, collaborative activities with the region, and children’s play activities. These projects are carried out in collaboration with universities as well as related private and public institutions. Due to the nature of the location, where there is a massive floating population, the events held by them in the city have a great influence. Therefore, the physical distance limit for NDPS against the derived CPS is small compared to other cases. The influence of an organization encourages the marketization of the organization and facilitates collaboration with companies. In this case, play is revealed in the language and behavior of income generation. For example, there is an event in which children make and play with robots together in an outdoor plaza, which is hosted by Manabi Daisuki, a nonprofit corporation that holds outdoor events, in collaboration with Tokyo City University and VIVITA, a private company that produces science tools for children. From the perspective of potential income generation, the locational characteristics of the condensed and attractive commercial city where Dream Campus is located essentially guarantee the success of temporary events by ensuring capital through the participation of companies. These temporary play events engage a broader community of adults connected to children, encourage them to ask questions about future events, and interact with public spaces to quickly reconstruct them. Through this, the CPS of Dream Campus can contribute to the public while increasing its sustainability and exerting influence over a more extensive area.

The above CPS distribution examples were derived from NDPS with different operating entities and uses such as a small community base, playhouse, visitors center, and university campus. However, all of the cases discussed here show the common nature of discovering, experimenting, and expanding urban space that can be used more positively through play. Each of the NDPS/CPS sets was temporarily broadening the area of the city that can be enjoyed by urban residents of all ages and expanding the sense of safe play, which had been provided by children’s playground fences in the past, in everyday life (). This not only expands the realm of physical play but also reveals a flexible and solid new play fence in the world of new play affordances.

6. Significance of the change in the fence paradigm

The permissive and expandable fences revealed in the NDPS/CPS model based on new play affordances show a new space production method using play in a modern city. In the cases of Setagaya ward, many of the CPS functioned only temporarily, but a few CPS were validated and settled, bringing physical changes to the urban space. This reveals that the interactive space production process is both bottom-up and top-down. NPDS is a discussion place in which various subjects gather together to plan a space, and CPS is a testing ground to test and validate that space. In the process of testing and validation, it is decided whether the space will be restored (extinct) or remain transformed (settled; ). This process is shared by interactive social media and carried out with the participation of local residents of various ages. Therefore, the newly created space connotes the opportunity for everyone, regardless of age, to reproduce their imagination in the local space.

7. Conclusion

This study questioned the strong criticism of separating children’s environment from the city with a fence and focused on the need for a new fence. This study defined new play affordances in modern society as the interactive media environment of modern society and various social programs provided by the private and public sectors with participation as the resource. The purpose is to discover the physical/non-physical forms of fences changed by new play affordances and help plan future urban architectural environment plans that embrace citizens of various ages. By observing these cases, we discovered a set of NDPS and CPS as new play spaces revealed in a modern city and reviewed the physical and social forms of fences shown in the new play space of a modern society. Fences in a modern society can be interpreted as “surrounding with a collective sense” instead of dependence on the physical fence. The social and spatial requirements for the formation of the sense of fence can be summarized as follows.

First, institutionalized play assistants create a social fence in the play space. They are formalized and specialized within a policy system, taking on the role of parents in the play space and acting as a non-physical boundary. Despite parents traditionally playing a crucial role in mediating children’s play and ensuring safety, they have been mentioned as a potential limiting factor in play. The child and caregiver support system outlined in Setagaya’s policy lays the groundwork for using play assistants as a new play affordance in the city and as a valuable resource for interactive and comprehensive regional care at the residential level. This also holds significance as it could also contribute significantly to job creation in the area.

Next, by providing social programs that are operated based on play but are not limited to a specific age, the burden of using urban space for a specific purpose of children’s play is reduced, and all local residents can participate and use the space. NDPS allow children’s play to be more naturally integrated into everyday life in the city.

Finally, CPS is expandable as a temporary fence that pursues social transformation of urban space through free play. Furthermore, the newly observed CPS were different from the original CPS claimed by existing researchers in that they have attributable NDPS. While the existing CPS was a concept related to everyday urban space permitting free play away from the fence and formed by the denial of DPS, the CPS found in Setagaya have a controlled fence within the system as a set with NDPS. Their urban influence is differentiated from the sporadic and one-time intervention of existing individual initiatives in that they are planned based on NDPS and undergo constant experimentation. Therefore, unlike the CPS that were generated and disappeared independently, CPS generated from NDPS may bring a more lasting and permanent change to the city.

This study discovered that play affordances in modern society have changed substantially from the past, changing the form of the fences in the urban play space. NDPS/CPS in which institutionalized play assistants are involved were significantly changing the way in which non-institutional time and public space were used in play as a coexistent relationship rather than conflicting concepts. This study has significance in that it defined NDPS as an institutionalized participatory play space based on the new communication technology of modern society. At the same time, it is significant that CPS was studied as an alliance with NDPS, not just a temporary play space developed by various initiatives as in previous studies. We further discovered a new urban space creation method through the CPS that are connected to NDPS. However, this study has limitations in that it did not carefully validate the operation method of social media and social programs as new play affordances, which must be supplemented in follow-up research.

Disclosure statement

We hereby declare that the disclosed information is correct and that no other situation of real, potential, or apparent conflict of interest is known to us.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Soram Park

Soram Park research interest focuses on architecture and urban design for children, human behaviour and Architecture Theory.

Hyejin Jung

Hyejin Jung is an assistant professor in the Department of Architecture, College of Engineering, Inha University, Korea. Her research interests concern architectural and urban design, spatial characteristics, and the theory of placeness.

Sangeun Oh

Sangeun Oh is an associate professor at Myongji University School of Architecture in Korea, and her research focuses on integrated spatial generation, spatial characteristics, and materiality.

References

- Aitken, S. C. 2005. The Geographies of Young People: The Morally Contested Spaces of Identity. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Allen, L. H. 1968. Planning for Play. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Atmakur-Javdekar, S. 2016. Children’s Play in Urban Areas. Play and Recreation, Health and Wellbeing. Singapore: Springer.

- Ball, S. J., C. Vincent, S. Kemp, and S. Pietikainen. 2004. “Middle Class Fractions, Childcare and the ‘Relational’ and ‘Normative’ Aspects of Class Practices.” Sociological Review 52 (4): 478502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00492.x.

- Bang, C., J. Braute, and B. Kohen. 1989. The Nature Playground. A Place for Play and Learning. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Beazley, H. 2000. “Street Children’s Sites of Belonging.” In Children’s Geographies: Playing, Living, Learning, edited by S. L. Holloway and G. Valentine, 167. Vol. 8. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Benjamin, W. 1986. Illuminations. Vol. 241, No. 2. New York: Random House Digital, Inc.

- Bey, H. 1991. T.A.Z: The Temporary Autonomous Zone. New York: Autonomedia.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and G. W. Evans. 2000. “Developmental Science in the 21st Century: Emerging Questions, Theoretical Models, Research Designs and Empirical Findings.” Social Development Theory 9 (11): 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00114.

- Cairns, R. B., E. Jane Costello, and G. H. Elder Jr. 1996. The Making of Developmental Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carroll, P., O. Calder-Dawe, K. Witten, and L. Asiasiga. 2019. “A Prefigurative Politics of Play in Public Places: Children Claim Their Democratic Right to the City Through Play.” Space and Culture 22 (3): 294–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218797546.

- Chatterton, P., and R. Hollands. 2002. “Theorising Urban Playscapes: Producing, Regulating and Consuming Youthful Nightlife City Spaces.” Urban Studies 39 (1): 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980220099096.

- Chawla, L. 2002. “Insight, Creativity and Thoughts on the Environment: Integrating Children and Youth into Human Settlement Development.” Environment and Urbanization 14 (2): 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624780201400202.

- Christensen, P., and M. O’Brien. 2003. Children in the City: Introducing New Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Clerkin, A., and K. Gilligan. 2018. “Pre-School Numeracy Play as a Predictor of Children’s Attitudes Towards Mathematics at Age 10.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 16 (3): 319–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X18762238.

- Cunningham, C. J., and M. A. Jones. 1999. “The Playground: A Confession of Failure?” Built Environment 25 (1): 11–17.

- Davison, K. K., and C. T. Lawson. 2006. “Do Attributes in the Physical Environment Influence Children’s Physical Activity? A Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Behavior Nutrition & Physical Activity 3 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-3-19.

- Day, R., and F. Wager. 2010. “Parks, Streets and “Just Empty space”: The Local Environmental Experiences of Children and Young People in a Scottish Study.” Local Environment 15 (6): 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2010.487524.

- DCMS, A. 2003. Strategic Plan 2003–2006. London: DCMS.

- Douglas, G. 2012. Do-It-Yourself Urban Design in the Help-Yourself City. Architect-Northbrook. 43.

- Eyck, A. V., V. Ligtelijn, and F. Strauven. 2008. The Child, the City and the Artist: An Essay on Architecture: The In-Between Realm. Amsterdam: Sun.

- Fjørtoft, I., and J. Sageie. 2000. “The Natural Environment as a Playground for Children: Landscape Description and Analyses of a Natural Playscape.” Landscape and Urban Planning 48 (1–2): 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(00)00045-1.

- Frost, J. L. 1992. Play and Playscapes. New York: Delmar Publishers.

- Gibson, J. J. 1979. The Theory of Affordances. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. The People, Place And, Space Reader, 56–60. New York: Routledge.

- Gibson, J. J. 2014. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: Classic Edition. New York: Psychology Press.

- Gill, O., and G. Jack. 2007. Child and Family in Context: Developing Ecological Practice in Disadvantaged Communities. London: Russell House.

- Gospodini, A., and V. Galani. 2006. “Street Space as Playground: Investigating Children’s Choices.” Environment and Behavior 1 (3): 353–362. https://doi.org/10.2495/SDP-V1-N3-353-362.

- Grahn, P. 1991. “Landscapes in Our Minds: People’s Choice of Recreative Places in Towns.” Landscape Research 16 (1): 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426399108706326.

- Hart, R. 1979. Children’s Experience of Place. New York: Irvington.

- Harvie, J. 2013. Fair Play: Art, Performance and Neoliberalism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Haydn, F., and R. Temel. 2006. Temporary Urban Spaces: Concepts for the Use of City Spaces. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Heft, H. 1989. “Affordances and the Body: An Intentional Analysis of Gibson’s Ecological Approach to Visual Perception.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 19 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1989.tb00133.x.

- Heft, H. 1997. “The Relevance of Gibson’s Ecological Approach to Perception for Environment-Behavior Studies.” In Toward the Integration of Theory, Methods, Research, and Utilization, edited by G. T. Moore and R. W. Marans, 71–108. Boston: Springer.

- Heseltine, P., and J. Holborn. 1987. Playgrounds: The Planning and Construction of Play Environments. London: Mitchell.

- Hill, M., and K. Tisdall. 2014. Children and Society. London: Routledge.

- Horton, J., and P. Krafti. 2009. “Small Acts, Kind Words and ‘Not Too Much Fuss’: Implicit Activisms.” Emotion, Space and Society 2 (1): 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2009.05.003.

- Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage.

- Jupp, E. 2017. “Home Space, Gender and Activism: The Visible and the Invisible in Austere Times.” Critical Social Policy 37 (3): 348–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018317693219.

- Jutras, S., P. Morin, R. E. Proulx, M. C. Vinay, E. Roy, and L. Routhier. 2003. “Conception of Wellness in Families with a Diabetic Child.” Journal of Health Psychology 8 (5): 573–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053030085008.

- Kinchin, J., and A. O’Connor. 2012. Century of the Child: Growing by Design, 1900–2000. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

- Kylin, M., and S. Bodelius. 2015. “A Lawful Space for Play: Conceptualizing Childhood in Light of Local Regulations.” Children, Youth, and Environment 25 (2): 86–106. https://doi.org/10.1353/cye.2015.0028.

- Kyttä, M. 2002. “Affordances of Children’s Environments in the Context of Cities, Small Towns, Suburbs and Rural Villages in Finland and Belarus.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 22 (1–2): 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0249.

- Kyttä, M. 2004. “The Extent of Children’s Independent Mobility and the Number of Actualized Affordances as Criteria for Child-Friendly Environments.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 24 (2): 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00073-2.

- Lefaivre, L. 2007. Ground-Up City: Play as a Design Tool. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

- Lefebvre, H. 2014. “The Production of Space (1991).” In The People, Place, and Space Reader , edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, William Mangold, Cindi Katz, Setha Low, and Susan Saegert. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315816852.

- Loebach, J., and A. Cox. 2020. “Tool for Observing Play Outdoors (TOPO): A New Typology for Capturing Children’s Play Behaviors in Outdoor Environments.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (15): 5611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155611.

- Mariani, I., and G. Enrico. 2014. “The Game as Social Activator, Between Design and Sociology: A Multidisciplinary Framework to Analyse and Improve the Ludic Experiences and Their Social Impact.” In A Matter of Design. Making Society Through Science and Technology, edited by C. Coletta, S. Colombo, P. Magaudda, A. Mattozzi, L. L. Parolin, and L. Rampino, 51–68. Bologna: STS Italia Publishing.

- Matthews, H. 1995. “Living on the Edge: Children as ‘Outsiders’.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 86 (5): 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.1995.tb01867.x.

- Matthews, H., M. Limb, and M. Taylor. 2004. Children’s Geographies; Street as Thirdspace, 54–68. London: Routledge.

- Maxey, I. 1999. “Playgrounds: From Oppressive Spaces to Sustainable Places?” Built Environmet 25 (1): 18–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23289139.

- McKendrick, J. H. 1999. “Playgrounds in the Built Environment.” Built Environment 25 (1): 5.

- McKendrick, J. H. 2000. “The Geography of Children: An Annotated Bibliography.” Childhood 7 (3): 359–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568200007003007.

- McNeish, D., and H. Roberts. 1995. Playing It Safe: Today’s Children at Play. Ilford: Barnardo’s.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. 2004. Visible and Invisible. Seoul: Dongmunsun.

- Moorcock, K. 1998. Swings and Roundabouts: The Danger of Safety in Outdoor Play Environments. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University Press.

- Moore, R. C. 1986. Childhood’s Domain: Play and Place in Child Development. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Moore, R. C. 1989. Public Places and Spaces: Playgrounds at the Crossroads, 83–120. New York: Springer.

- Moyles, J. R., L. Stoll, and D. Fink. 1989. Just Playing?: The Role and Status of Play in Early Childhood Education. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Nassauer, J. I. 2012. “Landscape as Medium and Method for Synthesis in Urban Ecological Design.” Landscape and Urban Planning 106 (3): 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.03.014.

- Nicholson, S. 1971. “How Not to Cheat Children, the Theory of Loose Parts.” Landscape Architecture 62 (1): 30–34.

- NPO Kinuta Tamagawa Play Village. 2017. Articles of incorporation.

- Ohnishi, K., and M. Yoshinaga. 2017. “Green and Blue Spaces and Psycho-Physiological Adaptation in Primary School Children: The Sotoasobi Project.” Paper presented at the International Play Association Conference, Calgary, September 2017.

- Olwig, K. F., and E. Gulløv. 2003. Children’s Places: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. New York: Routledge.

- Opie, I. A., and P. Opie. 1969. Children’s Games in Street and Playground: Chasing, Catching, Seeking, Hunting, Racing, Duelling, Exerting, Daring, Guessing, Acting, Pretending. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Park, S. 2019. “A Study of Child Play-Network as an Urban Design Method.” Doctoral dissertation, Seoul National University.

- PPSG (Playwork Principles Scrutiny Group). 2005. The Playwork Principles. http://playwales.org.uk/login/uploaded/documents/Playwork%20Principles/playwork%20principles.pdf.

- Rasmussen, K. 2004. “Places for Children–Children’s Places.” Childhood 11 (2): 155–173.

- Sakamoto, J. 2017. Investigative Research on Practices and Multi-Functionalization That Contribute to the Quality Improvement and Development of Local Child-Rearing Support Bases. Tokyo: NPO Corporation Child-rearing Hiroba National Liaison Council.

- Sarkar, S. 2014. “Environmental Philosophy: From Theory to Practice.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 45 (1): 89–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2013.10.010.

- Senda, M. 2016. Building Where People Gather: Environment X Design X Children’s Research. Tokyo: Kodansha.

- Setagaya Ward. 2015a. Outdoor Play Policy. Tokyo: Setagaya Ward.

- Setagaya Ward. 2015b. Setagaya Ward Children’s Plan (Phase 2). Tokyo: Setagaya Ward.

- Solomon, S. G. 2014. The Science of Play: How to Build Playgrounds That Enhance Children’s Development. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England.

- Stavrides, S. 2015. “Common Space as Threshold Space: Urban Commoning in Struggles to Re-Appropriate Public Space.” Footprint 16 (16): 9–19. https://doi.org/10.7480/footprint.9.1.896.

- Tayebi, A. 2013. “Planning Activism: Using Social Media to Claim Marginalized citizens’ Right to the City.” Cities 32 (32): 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.03.011.

- Thomson, S. 2003. “A Well-Equipped Hamster Cage: The Rationalisation of Primary School Playtime.” Education 31 (2): 54–59.

- Thomson, S. 2005. “‘Territorialising’the Primary School Playground: Deconstructing the Geography of Playtime.” Children’s Geographies 3 (1): 63–78.

- Thurmaier, K., and C. Wood. 2002. “Interlocal Agreements as Overlapping Social Networks: Picket-Fence Regionalism in Metropolitan Kansas City.” Public Administration Review 62 (5): 585–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00239.

- Tranter, P., and J. Doyle. 1996. “Reclaiming the Residential Street as Play Space.” International Play Journal 4 (1): 91–97.

- Voorhees, M. D., V. L. Walker, M. E. Snell, and C. G. Smith. 2013. “A Demonstration of Individualized Positive Behavior Support Interventions by Head Start Staff to Address Children’s Challenging Behavior.” Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 38 (3): 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/154079691303800304.

- Woolley, H. 2007. “Where Do the Children Play? How Policies Can Influence Practice.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Municipal Engineer 160 (2): 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1680/muen.2007.160.2.89.

- Woolley, H. 2008. “Watch This Space! Designing for Children’s Play in Public Open Spaces.” Geography Compass 2 (2): 495–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00077.x.

- Yoshinaga, M., I. Kinoshita, and Y. Terauchi. 2009. “Until the Creation of a Playground Map for Four Generations: Trajectory of the Four-Year Play and Town Study Group from 2005 to 2008.” Housing Research Foundation 10 (1): 79–82. http://jglobal.jst.go.jp/public/200902247832899400.