A succession of major crises has tested the resilience of the European Union (EU), leading many observers to predict its imminent demise. The Eurozone crisis, the refugee crisis, Brexit, and rule-of-law backsliding have presented distinct threats to European integration. Yet, while these crises have battered the Union, they have also prompted reforms that have strengthened its authority in significant respects. The coronavirus pandemic is only the latest in a series of such challenges. Time and again during the pandemic, the European Union appeared to fumble, only to pull itself together to forge a common response; time and again, that European response has turned out to be more effective than critics might have imagined and yet less than proponents might have wished. Beneath the tempestuous surface, however, the EU’s authority continues to strengthen (Jones, Citation2020).

Scholarly reflection on the impact of this long decade of crises has led to a wave of important new works on integration theory. A number of scholars have revisited grand theories of integration – neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalism, and post-functionalism – to shed light on the impact of crises on the European project (e.g., Biermann et al., Citation2019 Hooghe & Marks, Citation2019; Schimmelfennig, Citation2018). Some crafted theories of European disintegration (Jones, Citation2018; Vollaard, Citation2014; Webber, Citation2019); others offered theories of integration through crisis (Biermann et al., Citation2019; Davis Cross, Citation2017; Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2018; Lefkofridi & Schmitter, Citation2015).

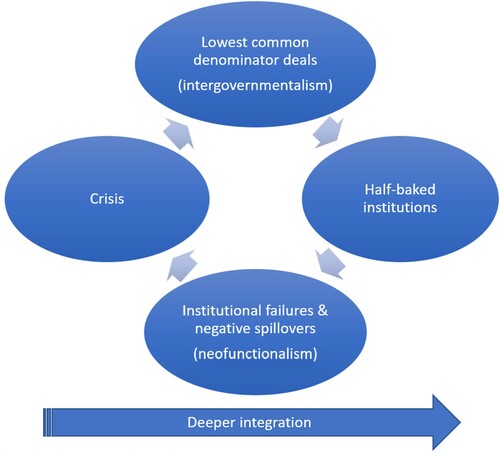

In our contribution to this new wave of integration theory (Jones et al., Citation2016), we bridged the liberal institutionalist and neo-functionalist traditions to argue that in some circumstances European integration proceeded through a pattern of failing forward: in an initial phase, lowest common denominator intergovernmental bargains led to the creation of incomplete institutions, which in turn sowed the seeds of future crises, which then propelled deeper integration through reformed but still incomplete institutions – thus setting the stage for the process to move integration forward.

This pattern is not the only way European integration takes place, but we suspect it is a common one. It might also be politically problematic. While these dynamics rooted in failure foster deeper integration, they also may undermine popular support and legitimacy for the European project. Hence it is important to explore just how common this pattern is. Our original article showed how failing forward could illuminate aspects of the Eurozone crisis and the development of the EU’s Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). Subsequently, a handful of scholars have identified the failing forward pattern in other policy sectors, such as EU migration policy (Scipioni, Citation2018) and the common asylum system (Lavenex, Citation2018). The next step is to look more systematically at the existence of this pattern across the range of European endeavors.

This Special Issue of the Journal of European Public Policy has two objectives. First, we clarify some ambiguities in the original formulation of the failing forward framework. Second, we analyze scope conditions under which we are likely to see failing forward. To achieve these objectives, we bring together articles that engage with the failing forward framework. Some contributions seek to refine the concepts and arguments, others challenge them outright. These pieces assess the applicability of the framework to a range of policy areas, from trade negotiations, competition policy and banking union through citizenship and the rule of law to pandemic response and defense and security policy, thus helping to identify the domains and conditions in which failing forward is likely to occur, and those in which it is not.

This introduction to the Special Issue begins by clarifying the original argument. We then refine the theoretical framework by specifying its scope conditions, introducing the individual contributions, and highlighting what they reveal about the strengths and limitations of failing forward as a pattern of European integration.

Clarifying the conceptual framework

The failing forward framework addresses both empirical and theoretical puzzles in European integration. The empirical puzzle we explored in our initial article concerned a particular pattern of integration we observed in the context of the eurozone crisis, which linked short-term actions and longer-term trends. What we found puzzling was that at different moments in that crisis, EU leaders adopted minimal, stopgap reforms to hold together the Eurozone, despite the fact that many of them recognized that these stopgaps would be unsustainable and that more comprehensive reforms would eventually be needed.

This initial assessment may seem judgmental given that Europe’s leaders were struggling with an unprecedented set of events. We did not mean for our characterization to sound overly negative. On the contrary, another part of the puzzle we sought to explore was that over the longer term these stopgap reforms consistently moved the EU in the direction of deeper integration. What looked incomplete or ineffective viewed in isolation appeared far more salutary when viewed from a longer term perspective. With hindsight, moments when the EU had appeared to fail turned out to be instances of failing forward.

This empirical puzzle was linked to a theoretical one: the two phases we observed (the short-term bargaining leading to stopgap reforms and the longer-term pattern of institutional deepening) seemed to draw on causal mechanisms that established theoretical traditions usually treat as mutually exclusive. The short-term bargaining looked like liberal intergovernmentalism: the incremental reforms introduced during moments of crisis could best be explained by focusing on the type of interstate bargaining that a liberal intergovernmentalist perspective would lead one to expect. The longer-term evolution looked like neofunctionalism: the deepening over time that linked together moments of crisis bargaining could best be explained as a product of the forces of spillover and supranational activism. The analytical challenge was to build an explanatory framework within which both theoretical traditions could coexist.

illustrates the failing forward dynamic posited in our original study of EMU and observed in some of the other policy areas presented in this Special Issue.

The failing forward pattern is useful for students of European integration insofar as it reconciles the apparent tension between liberal intergovernmentalism and neofunctionalism. These causal theories are competing on a different level of analysis, but we argue that they operate in tandem, unfolding in different moments and at different paces. As we explained:

Intergovernmental bargaining involving states with divergent preferences leads to institutional incompleteness because it forces settlement on lowest common denominator solutions. Incompleteness then unleashes neo-functionalist forces that lead to crisis. Member states respond to this crisis by again settling on lowest common denominator solutions. Each individual bargain is partial and inadequate. As these negotiated solutions accumulate over time, they lay the foundations for further integration. (Jones et al., Citation2016, p. 1027)

Two further clarifications of the initial failing forward pattern are warranted here: what constitutes ‘failure’ and what constitutes ‘forward’. First, the meaning of ‘failing’ is ambiguous. It could mean to be unsuccessful at attaining a goal, when the objectives of the policy agreed by the actors themselves are not achieved: for example, if the goal of introducing a single supervisory mechanism for European banks in 2012 was to unlock the potential for the European Stability Mechanism to inject capital directly into troubled financial institutions, then that innovation failed insofar as direct capital injections were never used and indeed were taken off the table when the Cypriot banks got in trouble in 2013. It could also mean that a policy that seemed to be working breaks down: For instance, the introduction of Long-Term Refinancing Operations by the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) in December 2011 appeared to stabilize sovereign debt markets in Spain and Italy, but inadvertently tightened the doom loop between bank bailouts and sovereign finances that led to a crisis the following summer.

These two examples unfolded quickly in the context of a sovereign debt crisis that governments were still struggling to understand. That should not imply, however, that failing forward is something that happens only in the heat of a moment characterized by high uncertainty. As we suggested in our original failing forward framework, incomplete agreements can leave room for policy failure that may happen at some point in the distant future. Sometimes that failure results from dynamics unleashed by the policy itself; sometimes it results from a recurrence of problems that policymakers could have addressed in their initial agreement but chose not to because doing so would be too controversial. These are common sources of policy failure. The literature is replete with discussions of the sources of and responses to unintended consequences, the limits of collective action, and policy failures of various sorts (Bovens & ‘t Hart, Citation2016). What we contribute is an analysis of these dynamics in the EU context that combines causal mechanisms associated with grand theories of European integration to explain how the EU sometimes deepens through cycles of policy failure.

Second, we wish to clarify what we mean by forward. Moving forward in this context typically refers to deeper European integration through increased coordination of national policies, the transfer of authority to the EU level in new policy areas, or the strengthening of the EU’s authority in existing areas of competence (see Kelemen et al., Citation2014, p. 661). In another sense it refers to decision-makers attempting to bolster the ‘incomplete’ institutions they see as responsible for helping to cause the policy failure in question. While there may be no objective definition of what would constitute a ‘complete’ governance architecture for a given policy area, the crucial issue for our framework is that decision-makers come to believe that the existing architecture is lacking in some important respects and needs to be deepened. This ‘forward’ momentum towards deeper integration could coexist with the decentralization of enforcement responsibilities, as has been the case in competition policy (Dierx & Ilzkovitz, Citation2021). But forward could mean widening as well as deepening, as in the case of European enlargement (see Anghel & Jones, Citation2021). Or it could mean deepening in lieu of widening, as in the elaboration of the European neighborhood policy (Rabinovych, Citation2021). The transfer of authority is not the only measure of forward movement, but admittedly it is the most important.

Hence, when we talk about incomplete solutions or agreements, the measure of that incompleteness is related to the problem that the policy was meant to address and not to the European project as a whole. In our original formulation, we talked about ‘incompleteness’, which refers to gaps or design flaws in the initial delegation of competence to the EU level as a policy solution. In the failing forward dynamics, policy makers are faced, in a moment of crisis, with a binary choice: cut their losses by reverting back to addressing a particular policy issue at the national level (what scholars have come to call European disintegration) or move ‘forward’ by delegating more powers to the EU level in order to address whatever problem they face more effectively.

The point we want to underscore is that this meaning of forward is not teleological. We do not argue that every intergovernmental bargain has to result in deeper integration or that every agreement is doomed to fail. Rather, we argue that a large number of agreements do point toward deeper integration in ways that the policymakers who negotiate them recognize are likely to come up short – which leaves scope both for policy failure and also for supranational entrepreneurship. Neither is the failing forward argument normative: while it suggests that integration may deepen through a cycle of crisis and incremental reform, it does not presuppose that this deepening is necessarily desirable. Indeed, caution about the implications of deepening European integration is a large part of the reason why policymakers resist or constrain agreements. Just because Europe is moving ‘forward’ does not mean it is getting better.

Finally, while the choice to delegate more powers to the European level in order to solve vexing policy problems can propel integration, it also entails risks. As we noted in our original failing forward article, the practice of advancing integration by introducing stopgap reforms that plant the seeds of, or leave space for, future problems may ultimately prove self-undermining and unsustainable. We suggested that it might give the public the impression that ‘the EU is rudderless and in a perpetual state of crisis’ and hence undermine public support for European integration.

Indeed, the more European solutions appear to fail to address pressing problems, or worse, the more they appear to create problems for the future, the more quickly any permissive consensus is likely to evolve into a constraining dissensus on the European project (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009). This expectation of diminished public support was at least partially contradicted by the resurgence in public support for the EU (and the Euro) in the wake of the series of crises the EU faced over the past decade. However, the concern that a recurrent pattern of integration through crisis may be self-undermining in the long term remains, and has been brought to the fore once again by the public reaction to the EU’s initial stumbles in mounting a coordinated response to the coronavirus crisis and a widespread decline in trust in the European Court of Justice in the aftermath of elevated migration and expansive rulings on EU citizenship.

Scope conditions: delimiting failing forward

In his memoirs, Jean Monnet famously said that, ‘Europe will be forged in crises, and will be the sum of the solutions adopted for those crises.’ (Monnet, Citation1978, p. 417). That is not our argument. We do not believe that a pattern of integration through cycles of crisis is the only way European integration advances. Neither do we believe that all policy crises lead to the deepening of integration, nor do we assume that all European integration crises originate from the logic of failing forward. The disintegration theorists have a point; so do the new theorists of integration. Some policy failures may lead to disintegration, and some leaps forward in integration may not come in reaction to past failures (Parsons & Matthijs, Citation2015). That is why it is important we set out scope conditions to help suggest where this pattern is likely to be applicable and where it is not (Harris, Citation1997).

The three conditions that we believe to be most important relate to the intensity of the crisis, the existing competence of European institutions, and the costs of unwinding European arrangements in order to pursue national solutions. All things being equal, the failing forward dynamic is more likely to take place depending upon the extent of the policy crisis generated by the ‘failure’, the degree to which EU institutions already hold competence in the area in question (and so perceive the crisis as an opportunity to push integration ‘forward’), and the cost of unwinding the incomplete EU arrangements in question rather than moving ‘forward’ by granting them more authority.

These relationships – and the scope conditions they entail – are not strictly proportional. It takes a big crisis to push European leaders into action. EU institutions have a hard time breaking into new policy areas; they also see few opportunities to deepen integration where they already have exclusive competence. And the implications of unwinding existing institutions can differ dramatically from one policy area to the next: capital, goods, services, and labor can have more or less freedom of movement across the internal market, for example, but national currencies are either irrevocably fixed to one-another in a monetary union or they are not. We use the rest of this section to explore those relationships further and to introduce the contributions to this Special Issue.

Intensity of the crisis

Crisis is a key element in the failing forward dynamic. The shared perception of the existence of a major crisis motivates decision-makers to confront the shortcomings of their existing, incomplete institutional arrangements and to return to the bargaining table to consider reforms. The challenge lies in distinguishing between a ‘crisis’ in conventional speech and the kind of crisis that spurs European leaders into action.

Failing forward is more likely to take place the more the crisis European leaders face has the following characteristics: (1) encompassing, which means the crisis affects many member states; (2) unfamiliar, which means it should push European leaders out of their conventional ways of understanding problems and into the realm of Knightian uncertainty; and (3) existential, which means it is widely perceived as a threat to the survival of existing institutional arrangements in a given domain, or even the survival of the EU itself. Each of these characteristics implies a high threshold for action. We expect to see failing forward dynamics play out the more a crisis has these attributes. The case study of the global financial crisis that we explored in our original paper involved all three.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic was also an encompassing, unfamiliar, and potentially existential crisis. Martin Rhodes (Citation2021) believes this combination of factors was sufficient to push European leaders beyond ‘failing forward’ and toward something more fundamentally creative. Rhodes’ contribution asks why the EU, which has been pilloried for its lack of capacity in the face of major crises, has performed better in managing the early COVID-19 pandemic than a raft of recent literature on the EU’s failings would have us believe – and at least as well as, if not better in certain respects, than the US. His argument is not that the EU’s response was problem-free, but that EU leaders rose well beyond what we might consider the ‘least common denominator’ in negotiations and achieved results that were impressive relative to responses undertaken elsewhere. Rhodes uses his comparative study of the EU and US to critique, and then build upon, the original failing forward framework.

There is merit to that argument. Again, we never meant to imply that all European crisis response efforts are doomed to failure or that failing forward is the only way that European integration progresses. Failing forward is one pattern among many. What struck us at the time, and what still strikes us, is the extent to which European leaders introduce measures that they know will be inadequate due to the reluctance of member states to sign up to stronger or more effective arrangements – and this despite considerable warnings among academics, policy advisors, and even powerful member state governments that such incompleteness could come back to haunt the European project. This is the point Howarth and Quaglia (Citation2021) make in their more narrowly focused analysis of the fiscal dimension of the EU’s pandemic response. They argue that the pandemic gave Europe’s leaders the best chance they have ever had to redress the institutional imbalance in the euro area by adding a serious fiscal component to pair with the single currency. And they highlight that once again Europe’s leaders have inched toward a common fiscal capacity only to settle for something that is macroeconomically underpowered, not linked specifically to addressing EMU asymmetries, and – at least officially – only temporary.

Shawn Donnelly (Citation2021) shares the more pessimistic version of Europe’s response to the crisis offered by Howarth and Quaglia. He also emphasizes that the incrementalism involved is a feature and not a bug. His point is not to deny that the new financial arrangement constitutes a significant leap forward in the European project; there is a clear sense in which European integration is deeper as a result. Rather, his goal is to underscore that the innovation falls short of what many politicians and policymakers acknowledge to be a comprehensive solution. Donnelly highlights the extent to which Europe’s strongest Member States have a habit of insisting on shaping any agreement along their own policy preferences. When they cannot achieve their ambitions within the Treaty framework, they are willing to work outside European institutions to retain their room for maneuver. Donnelly uses the European Stability Mechanism to illustrate this dynamic. He also points out that if the purpose of creating the ESM was to resolve the problem of bailing out member states in crisis, then the negotiation of Next Generation EU shows the political constraints that operate on that arrangement.

Of course, not every crisis is as intense as the recent pandemic, even if sometimes they might feel that way. As Mai’a Cross (Citation2017) has noted, the EU is plagued by episodes of ‘integration panic’, in which the media and many political actors exaggerate the extent to which various policy crises threaten the very survival of the Union. In reality, the intensity of crises the EU has faced varies significantly. Financial crises (Howarth and Quaglia, Donnelly), pandemics (Rhodes), and military actions (Bergmann & Mueller, Citation2021) are examples of urgent crises that demand immediate responses. By contrast other crises – such as the erosion of rule of law (Emmons & Pavone, Citation2021), political disorder in those countries that border on the European Union (Rabinovych, Citation2021), or Brexit (Conant, Citation2021) – may be equally severe but slower burning or more vulnerable to the rhetorical strategies of those who seek to discount their severity. Finally, some crises may not be as urgent or severe, but still have significant long term implications, such as the failure to ratify trade agreements (Freudlsperger, Citation2021) and the risk of unfair competition in the single market (Dierx & Ilzkovitz, Citation2021).

Supranational competences

Policy failures and ensuing crises do not automatically lead policy-makers to respond with deeper integration. As scholars of crisis politics have emphasized, crises lead to ‘framing contests’ (Boin et al., Citation2009) in which rival political actors compete to interpret the crises in ways that suit their preferred policy agenda (see also Emmons & Pavone, Citation2021). As we explained in our original article, supranational political entrepreneurs can play an important role applying pressure during EU policy crises in order to promote deeper integration. However, we were less clear about the conditions that might affect this dynamic. The ability of supranational actors to play this catalytic role will depend on their existing degree of policy competence in the policy area in question at the time the policy failure emerges (Tsebelis & Garrett, Citation2001).

The policy competences of supranational actors vary across issue areas – from those where they have no competence at all, to those in which they have exclusive competence. Where supranational actors have no competence, they may not be in the position to exploit a crisis to push for deeper integration. Where they have exclusive competence, they are more likely to be blamed for policy failures but can be more flexible in moving forward (see Dierx & Ilzkovitz, Citation2021)

It is actually in the middle of the competence spectrum, where the EU already has some established role and institutions, that we are most likely to observe failing forward. In such situations, the policy failures can easily be attributed to the incompleteness of EU institutions and supranational actors such as the Commission and the European Parliament, are already in the position to play a strong agenda setting role or otherwise steer member governments to respond to the policy failure by deepening integration. When European leaders were debating which institution should issue common debt during the initial weeks of the pandemic, for example, the European Commission benefited from the fact that it had some capacity to borrow on the markets, and from its ability to gain support for doing so in a limited fashion to backstop national employment protection and unemployment schemes via the SURE program.

Where the Commission’s competence is already exclusive, such deepening is harder to bring about. Trade policy, which was at the heart of the creation of the Common Market in the 1957 Treaty of Rome, has been one of the most integrated policy areas in the EU (Meunier, Citation2005). Nevertheless, it has taken several decades to settle the issue of institutional competence (some issues remaining still unsettled today) because the nature of the international trade agenda kept changing as globalization itself changed from trade in goods to trade in services (Meunier & Nicolaïdis, Citation1999), to behind-the-border issues (Young & Peterson, Citation2006), to foreign direct investment (Meunier, Citation2017).

Christian Freudlsperger (Citation2021) shows that a series of successive crises over the scope of EU competence in trade and investment have complicated international agreements and increased non-ratification but also acted as a catalyst for deepening. Due to the highly institutionalized role of traditional supranational actors such as the Commission and the Court in the internal market and its external dimension, failing forward occurs somewhat differently in this policy area and does not necessarily require full-blown systemic crisis. The Union also fails in the market, but it tends to do so without unleashing existential crises, while supranational entrepreneurs are more able to lead the way.

Similarly, the evolution of competition policy takes place in a policy domain falling under exclusive competence (Dierx & Ilzkovitz, Citation2021). Adriaan Dierx and Fabienne Ilzkovitz contrast policy development in the areas of antitrust and State aid versus merger control, for which the Commission was given responsibility only in 1990, analyzing differences as a result of successive crises resulting from capacity constraints, Court judgments and spillovers from the single market.

What Dierx and Ilzkovitz reveal is that even exclusive competence does not equate ‘completeness’ in the failing forward context. Giving the Commission too much responsibility can lead to institutional overload, for example. Unlike in commercial policy, characterized by increased delegation to the central authorities over time, integration in competition policy has gone hand in hand with a decentralization of enforcement responsibilities to the national level. Dierx and Ilzkovitz’s contribution refines the failing forward framework by adjusting the concepts of incompleteness and forward momentum to a policy area under exclusive EU competence.

At the other end of the continuum, in areas where the EU has very little or no competence such as defense and security or neighborhood policy, while supranational actors may seek to leverage the crisis to press for a greater EU role, they may not be in the position to exercise much leverage over national decision-makers. In their study of the integration of EU crisis management under the Common Security and Defense Policy, Bergmann and Müller (Citation2021) propose a conceptual refinement through the extension of neofunctionalist failing forward dynamics to political spillover mechanisms and the role of experiential learning.

Experiential learning from sub-optimal policy outcomes may lead to a situation in which incomplete institutions create policy feedback effects that are then incorporated into subsequent reform efforts. This finding is an important reminder that ‘spillover’ and other neofunctionalist processes can be positive and not just negative – a point also emphasized by Rhodes. Bergmann and Müller demonstrate how institutionalized policy feedback loops and experiential learning informed incremental reforms, culminating in the Civilian CSDP Compact and the European Peace Facility. Their contribution argues that a failing forward lens helps to understand the limits that intergovernmental bargains may set for supranational entrepreneurship in CSDP.

Maryna Rabinovych (Citation2021) investigates the applicability of the failing forward framework to the Eastern dimension of the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP). She shows that the ENP’s Eastern dimension is stuck in limbo between the neo-functionalist-driven deepening of integration and the absence of an intergovernmental consensus as to the ultimate ambitions of the ENP. She finds that the failing forward framework yields insight into policy development of ENP in terms of both developments at critical junctures and everyday decision-making and related functional pressures. However, she argues that because the concept of ‘incompleteness’ is ambiguous in the domain of foreign policy and because the crises characteristic of this policy area stem from exogenous causes there are limits to the framework’s explanatory power. Clearly, in this field, the limited competence of supranational actors made it more difficult for them to exploit crises in order to push for significant policy deepening.

Apart from areas like trade and competition, where EU authority is very extensive, and areas like defense and foreign policy, where it is minimal, most other policy domains the EU is engaged with – from Economic and Monetary Union, to most regulatory policies – fall into the middle of the spectrum where policy competences are shared between the EU and the Member States. It is in this middle terrain where we expect failing forward to be most prevalent. The examples provided by Rhodes, Howarth and Quaglia, and Donnelly are good illustrations – even if Rhodes would probably object to the characterization of progress made during the pandemic as any kind of a ‘failure’. Enlargement is a good illustration as well (Anghel & Jones, Citation2021).

What makes Rabinovych’s story about European neighborhood policy so interesting in this context is the fact that the Member States chose to hold the neighborhood countries outside the accession process and to treat them within the context of foreign and security policy instead. The reason for this decision is that a membership prospect is difficult to withdraw once it has been offered. Frank Schimmelfennig (Citation2003) made this point in the context of NATO as well as the European Union. What Anghel and Jones (Citation2021) reveal is how powerfully such commitments influenced the process of EU enlargement.

Costs of going backwards

A lock-in effect represents our third major condition. As any driver who has been stranded in the middle of an intersection knows, the more difficult it is to back up, the more likely you will try to escape an oncoming vehicle by moving forward. Similarly, when EU policy makers confront a crisis caused by an institutional failure and must determine how to respond, the more costly it is to unwind the EU institutions in question, the more likely it is they will respond instead by transferring more authority to those institutions. Two illustrations might be Cyprus in 2013 and Greece in 2010, 2012, and 2015. What is interesting is not just that both countries chose to accept painful reforms and grinding austerity measures rather than abandon the euro. It is that even very skeptical Member States agreed that it would be better to keep both countries in the single currency than to run the risks associated with pushing them out of Europe’s monetary union. This is the sort of context where we expect to find ‘failing forward’.

That said, the ‘failing forward’ pattern is hardly ubiquitous. At least part of the reason is that the strength of such lock-in effects is not the same across different domains or areas of integration. As historical institutionalists have shown, institutions with particular features (i.e., those involving large fixed costs, learning effects, coordination effects, and adaptive expectations) are more prone to produce positive feedback, lock-in, and path dependence making the costs of reversal very high (Arthur, Citation1994 Pierson, Citation2000;). Another factor that can influence the cost of going backwards is whether the institutional arrangement in question can be temporarily suspended – rather than needing to be permanently dismantled – at moments of crisis. For both Cyprus and Greece, for example, it was easier to impose temporary capital controls – and so suspend one of the ‘four freedoms’ essential to Europe’s internal market – to stave off a banking crisis, than to look for ways to exit the single currency. Similarly, member states have temporarily suspended freedom of movement for people either to gain better control over cross-border migration or to slow the spread of the pandemic.

Even the presence of strong commitments or high costs is not enough to prevent disintegration; sometimes paying a high price to leave may be preferable to the alternative of remaining. This is the point made by Lisa Conant (Citation2021) in her juxtaposition of citizenship policy and Britain’s choice to leave the European Union (or Brexit). Conant shows how failing forward and moving backward can both occur on different dimensions of the same policy area – and that in fact they may be interlinked. She demonstrates that the incompleteness of EU citizenship rights generated policy failures, which in turn triggered litigation and provided European courts the opportunity to push the meaning of EU citizenship forward – all in keeping with the failing forward framework. However, she demonstrates at the same time that backlash against these dynamics fed into the domestic policy debate in Britain in ways that supported the Leave campaign. Moreover, she emphasizes that the incompleteness of EU citizenship rights in the UK enabled the British government to limit the franchise of millions (including EU nationals resident in the UK, and Britons residing long term in other EU countries) in ways that helped the Leave campaign win and thus facilitated ‘failing backwards’ in the form of the UK’s exit from the EU.

Conant’s story about citizenship rights and Brexit is not the only illustration of how failing forward can wind up looking more like ‘failure’ than progress. Emmons and Pavone focus attention on another policy area where the jury is still out as to whether the direction of travel is really ‘forward’ in the sense of promoting deeper integration. Specifically, they explore the EU’s failure to respond effectively to what some view as its most existential crisis – the systematic attacks on democracy and the rule of law in Hungary and Poland.

Emmons and Pavone argue that the EU ‘failed to fail forward’ in reaction to the rule of law crisis because member state governments and EU officials who, for various reasons, opposed more robust protection of the rule of law, deployed effective rhetorical strategies – what Emmons and Pavone call ‘rhetorics of inaction’ – to justify the EU’s failure to use its existing tools or to develop and deploy new tools in the defense of democratic norms. Their contribution underscores the role that agency can play in blocking the failing forward dynamic: even in the face of functional pressures one might expect to trigger a failing forward dynamic, actors who oppose institutional deepening may act strategically – including through the use of rhetorical strategies – to block this from occurring.

The tragedy in both Emmons and Pavone’s and Conant’s argument is that the costs of failure are likely to be far higher than many suspect. What looks like a temporary aberration in a limited geographic space tends to have lasting if not irreversible consequences for the union as a whole. Kelemen (Citation2019, p. 249) compares it to creating a toilet section in a swimming pool. Rhetorical strategies may obscure these consequences, but they cannot prevent them. Having high costs for going backward may make failing forward more likely, but that is no guarantee that the EU will not ‘fail to fail forward’ (Emmons & Pavone, Citation2021).

Conclusion: limitations and extensions of the failing forward framework

The articles in this Special Issue critically engage with the failing forward framework, refining and challenging the applicability of the argument across a range of policy areas. These papers do more than simply assess the range of application of the framework; some contributors add nuances to the argument or substantially amend it, others question whether failing forward is distinctive to the process of European integration or is simply a manifestation of more generic dynamics of institutional change, while some directly challenge the framework itself.

Taken together, the articles suggest that European policymakers are more likely to fail forward when they have to work together in an improvised manner under extreme time constraints to solve an unfamiliar problem (Rhodes). They are also more likely to fail forward when the justification for working together is already well-established in terms of the distribution of competences across European institutions – although, we should probably note here that the direction of travel may be toward less central involvement when European competence over a policy area is complete (Dierx and Ilzkovitz, Freudlesperger). And they are likely to fail forward when the only way to act independently is to unwind an arrangement at great cost, like Europe’s economic and monetary union (Howarth and Quaglia).

By contrast, when governments face a challenge that is important but not self-evidently and immediately life-threatening, that is familiar or looks familiar, that falls squarely within their competence, and where they can act freely without impinging on their European commitments, we do not expect them to reach for lowest common denominator bargains that unleash neofunctionalist spillovers. Much of what we describe as European integration falls in this space. It is the routine business of the European Union. We do not deny the significance of such action; it simply is not the focus for our analysis.

Of course there is a lot of grey area between the two extremes. Sometimes Europe fails forward in this in-between space; sometimes not. That is more observation than judgment. As Laurens Hemminga put it in the context of European investment policy toward China:

‘The EU has often worked like this: a half-measure today leads to a (more) full measure in the future. This may seem far from ideal, but then, for 27 countries to coordinate policies on important issues is no trivial challenge and it’s not clear that there is a better model available’ (Hemminga, Citation2021).

There are also interesting cases where some criteria that suggest failing forward would apply and others do not. The papers in this collection do not offer every conceivable combination, but they do illustrate a wide range of possibilities. These papers also challenge us to use existing theories to ask new questions about the patterns we see across different areas of integration, the strengths and limitations of diversity within the integration process, and the prospects for more formal differentiation in what constitutes Europe. These are all issues that are attracting attention in debates about the future of Europe.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the participants to the workshop ‘Failing Forward of Falling Backwards? Crises and Patterns of European Integration’ held at Princeton University on 13 September 2019. Thanks to the European Union Program at Princeton (EUPP) and the Princeton Institute on International and Regional Studies (PIIRS) for funding. A heartfelt thank you to the many reviewers who were mobilized for this Special Issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Erik Jones

Erik Jones is Professor of European Studies and International Political Economy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies; from 1 September 2021, he will be Director of the Robert Schuman Centre at the European University Institute.

R. Daniel Kelemen

R. Daniel Kelemen is Professor of Political Science and Law at Rutgers University.

Sophie Meunier

Sophie Meunier is Senior Research Scholar at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, and Co-Director of the EU Program at Princeton.

References

- Anghel, V., & Jones, E. (2021). Failing forward in Eastern enlargement: Problem solving through problem making. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–20. online first: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1927155

- Arthur, W. (1994). Increasing returns and path dependence in the economy. University of Michigan Press.

- Bergmann, J., & Mueller, P. (2021). Failing forward in the EU’s Common Security and Defense Policy: The integration of EU crisis management. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1669–1687. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954064

- Biermann, F., Guérin, N., Jagdhuber, S., Rittberger, B., & Weiss, M. (2019). Political (non-)reform in the euro crisis and the refugee crisis: A liberal intergovernmentalist explanation. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(2), 246–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1408670

- Boin, A., ‘t Hart, P., & McConnell, A. (2009). Crisis exploitation: Political and policy impacts of framing contests. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(1), 81–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802453221

- Bovens, M., & ‘t Hart, P. (2016). Revisiting the study of policy failures. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(5), 653–666. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1127273

- Conant, L. (2021). Failing backward? EU citizenship, the Court of Justice, and Brexit. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1592–1610. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954061

- Davis Cross, M. (2017). The politics of crisis in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Dierx, A., & Ilzkovitz, F. (2021). EU Competition Policy: An application of the Failing Forward framework. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1630–1649. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954063

- Donnelly, S. (2021). Failing outward: Power politics, regime complexity, and Failing Forward under deadlock. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1573–1591. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954062

- Emmons, C., & Pavone, T. (2021). The Rhetoric of inaction: Failing to fail forward in the EU’s Rule of Law crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1611–1629. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954065

- Freudlsperger, C. (2021). Failing Forward in the Common Commercial Policy? Deep trade and the perennial question of EU competence. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1650–1668. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954059

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2018). From market integration to core state powers: The Eurozone crisis, the refugee crisis and integration theory. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(1), 178–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12654

- Harris, W. A. (1997). On “scope conditions” in sociological theories. Social and Economic Studies, 46(4), 123–127.

- Hemminga, L. (2021, April 24). “Think the EU isn’t acting on China? Look closer.” The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2021/04/think-the-eu-isnt-acting-on-china-look-closer/.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2019). Grand theories of European integration in the twenty-first century. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1113–1133. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1569711

- Howarth, D., & Quaglia, L. (2021). Failing Forward in Economic and Monetary Union: Explaining weak Eurozone financial support mechanisms. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1555–1572. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954060

- Jones, E. (2018). Towards a theory of disintegration. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(3), 440–451. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1411381

- Jones, E. (2020). COVID-19 and the EU economy: Try again, fail better. Survival, 62(4), 81–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2020.1792124

- Jones, E., Kelemen, R. D., & Meunier, S. (2016). Failing forward? The Euro crisis and the incomplete nature of European integration. Comparative Political Studies, 49(7), 1010–1034. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015617966

- Kelemen, R. D. (2019). Is differentiation possible in rule of law? Comparative European Politics, 17(2), 246–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00162-9

- Kelemen, R. D., Menon, A., & Slapin, J. (2014). Wider and deeper? Enlargement and integration in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(5), 647–663. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.897745

- Lavenex, S. (2018). ‘Failing forward’ towards which Europe? Organized hypocrisy in the common European asylum system. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(5), 1195–1212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.v56.5

- Lefkofridi, Z., & Schmitter, P. C. (2015). Transcending or descending? European integration in times of crisis. European Political Science Review, 7(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773914000046

- Mai'a Cross. (2017). The politics of crisis in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Meunier, S. (2005). Trading Voices: The European Union in International Commercial Negotiations. Princeton University Press.

- Meunier, S. (2017). Integration by stealth: How the European Union gained competence over foreign direct investment. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(3), 593–610. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12528

- Meunier, S., & Nicolaïdis, K. (1999). Who speaks for Europe? The delegation of trade authority in the EU. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 37(3), 477–501. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00174

- Monnet, J. (1978). Memoirs (R. Mayne, Trans.). Doubleday and Company.

- Parsons, C., & Matthijs, M. (2015). European integration past, present and future: Moving forward through crisis?. In M. Matthijs & M. Blyth (Eds.), The Future of the Euro? (pp. 210–232). Oxford University Press.

- Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. The American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251–267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2586011

- Rabinovych, M. (2021). Failing Forward and EU foreign policy: The dynamics of 'integration without membership' in the Eastern neighborhood. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1688–1705. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954066

- Rhodes, M. (2021). ‘Failing Forward’: A critique in light of Covid-19. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1537–1554. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954067

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2003). The EU, NATO and the Integration of Europe: Rules and Rhetoric. Cambridge University Press.

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2018). European integration (theory) in times of crisis. A comparison of the euro and schengen crises. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(7), 969–989. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1421252

- Scipioni, M. (2018). Failing forward in EU migration policy? EU integration after the 2015 asylum and migration crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(9), 1357–1375. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1325920

- Tsebelis, G., & Garrett, G. (2001). The institutional foundations of intergovernmentalism and supranationalism in the European Union. International Organization, 55(2), 357–390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/00208180151140603

- Vollaard, H. (2014). Explaining European disintegration. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(5), 1142–1159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12132

- Webber, D. (2019). Trends in European political (dis)integration. An analysis of postfunctionalist and other explanations. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1134–1152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1576760

- Young, A. R., & Peterson, J. (2006). The EU and the new trade politics. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(6), 795–814. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760600837104