ABSTRACT

The free movement of people (FMP) has been a core principle of European Union (EU) integration since its beginnings, but it has recently become contested. This article traces the politicization of FMP, and the topics associated with it, over time and across countries. Rather than constituting a linear or uniform trend, we argue that the politicization of FMP is differentiated: it is driven by particular events such as Eastern enlargement, mitigated by restrictive domestic policies anticipating the expansion of EU free movement rights, and that FMP is salient, but not polarized, from an emigration country perspective. Combining structural topic modelling and qualitative text analysis, we compare three decades of news coverage of FMP in Austria, Germany, Poland and the UK.

Introduction

The free movement of people (FMP) has been a core principle since the beginnings of European integration, but it has become contested in recent years. At the individual level, attitudes towards FMP are ambivalent (Lutz, Citation2021): while most citizens value their own mobility rights highly as one of the greatest achievements of European integration, anti-immigrant attitudes are a major source of Euroscepticism. At the political level, the remaining 27 EU member states fought hard to protect the ‘integrity of the Single Market’, including FMP, during the Brexit process (Schimmelfennig, Citation2018, p. 1167), but British calls to make free movement ‘less free’ also resonated with demands from other member state capitals (Blauberger et al., Citation2020, p. 936f.), and a partial suspension of FMP was among the first political reflexes during the refugee crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic.

In this article, we aim to disentangle these seemingly contradictory observations by studying the public debate on FMP across time and space. How strongly has FMP become politicized in the EU and what topics has it become associated with? And why, and to what extent, does the politicization of FMP vary over time and across countries? To answer these questions, we analyse news articles about FMP in Austria, Germany, Poland and the United Kingdom dating from 1990, as far as available, until 2019.

Our main contributions are theoretical as well as empirical. As to theory, we embed our analysis in the broader literatures on EU politicization and migration to develop two sets of expectations regarding the differentiated politicization of FMP over time and across countries. First, we question the recurrent assumption present in the literature on FMP of a clear trend towards ever more politicization and point to more idiosyncratic developments driven by specific events and shifting substantive topics related to FMP. Secondly, we hypothesize that cross-country variation in the politicization of FMP may be related to different policy styles (anticipatory and consensus-oriented or reactive and impositional). Countries like Austria and Germany sought to anticipate a public backlash against FMP by negotiating transitional measures in the context of EU enlargement and witnessed an early salience peak at that time. This stands in striking contrast to the absence of any broader public debate about the immediate opening of the British labour market in 2004 and to the escalating politicization of FMP leading towards Brexit. Finally, we expect patterns of mobility (destination or emigration countries) to influence the politicization of FMP and, indeed, the Polish ‘debate’ on FMP differs greatly from that in the destination countries. However, in contrast to our expectations, we find hardly any polarized debate about FMP in Poland, instead mostly technical and practical topics, e.g., on how to find a job abroad. FMP is of practical importance and, hence, salient in Poland, but it has not (yet) become politicized.

Empirically, we base our analysis on a large, original dataset of news articles on FMP, which covers up to three decades of EU history and four European countries. Most previous studies analyse migration more generally (Eberl et al., Citation2018, p. 208; Boomgaarden & Vliegenthart, Citation2009; Caviedes, Citation2015; Grande et al., Citation2019) rather than FMP in particular, and those focusing on FMP typically study one or two countries and shorter time periods (Balabanova & Balch, Citation2010, Citation2016, Citation2017; Danaj & Wagner, Citation2021; Morrison, Citation2019; Roos, Citation2019), or EU actors (Roos & Westerveen, Citation2020). Calls have been made for long-term, comparative studies and for the inclusion of the perspective of emigration countries, e.g., from Eastern Europe (Eberl et al., Citation2018, p. 218). By combining a quantitative analysis of our data through structural topic modelling (Roberts et al., Citation2019) with a qualitative analysis of typical articles, we are able to provide a nuanced account of the differentiated politicization of FMP over time and across countries.

The article is structured as follows. In the next chapter, we discuss the state of the art on the politicization of migration in general, and FMP in particular, to develop expectations regarding its variation over time and across countries. Subsequently, we describe and justify our research design, case selection and method before discussing our empirical findings. The final chapter concludes and discusses the generalizability of our findings as well as potential future research.

Differentiated politicization of FMP: state of the art and expectations

The literature on FMP has grown rapidly in recent years and addressed the issue from manifold perspectives including EU citizenship rights (Bauböck, Citation2019), intra-EU mobility and its implications for national welfare states (Schmidt et al., Citation2018), public opinion on FMP (Lutz, Citation2021), anti-FMP attitudes as a source of Euroscepticism (Toshkov & Kortenska, Citation2015) and as a driving force of Brexit (Goodwin & Milazzo, Citation2017). One common theme in this diverse literature is the perception that FMP has become increasingly politicized across Europe (Roos & Westerveen, Citation2020, p. 63; Seubert, Citation2020, p. 49). In the following, we depart from the general literatures on EU politicization and migration to derive expectations as to when and where FMP is likely to become politicized.

Variation over time

The increasing politicization of European integration has become a major subject for EU research. Postfunctionalism, which has joined the canon of core theories of European integration, argues that the EU post-Maastricht is characterized by an unprecedented mobilization of public opinion and party politics, i.e., it has become politicized (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009). On closer inspection, however, this overall trend needs to be qualified: ‘There is neither a single uniform process of politicization nor is there a clear trend over time’ (Grande & Kriesi, Citation2016, p. 279). Instead, it has been argued that EU politicization is ‘differentiated’ (de Wilde et al., Citation2016) over time and across space. Even though EU politicization has clearly intensified over the last two decades, its occurrence has been ‘cyclical’ (de Wilde et al., Citation2016, p. 5) or ‘punctuated’ (Grande & Kriesi, Citation2016, p. 280). Most conceptualizations of politicization, e.g., by de Wilde et al. (Citation2016, p. 7) and Grande et al. (Citation2019, p. 1450), include at least two dimensions: salience, i.e., the public visibility of an issue and polarization, i.e., the intensity of conflict. We follow this conceptualization and consider an issue to be politicized when both salience and polarization are high. To put it differently, an issue which attracts great public attention, but does not involve significant controversy, does not qualify as politicized.

Against this background, we have reason to doubt the often-assumed trend towards ever greater politicization of FMP across Europe. Intra-EU mobility has increased steadily since Eastern enlargement (European Commission, Citation2021, p. 27; Recchi, Citation2008). Nevertheless, given what we know about the politicization of the EU and of migration in general, increasing intra-EU mobility as such is unlikely to translate into greater politicization of FMP. Studies on the media salience of immigration have found that press coverage reflects political input and particular events such as 9/11 (Boomgaarden & Vliegenthart, Citation2009, p. 527) rather than overall immigration trends (Eberl et al., Citation2018, p. 209). Accordingly, we expect temporal peaks of salience in the context of events with significant implications for FMP, and providing opportunities for politicization, such as the accession of new member states. In a similar vein, since FMP was a core issue in the British referendum in 2016 (Goodwin & Milazzo, Citation2017) and in subsequent Brexit negotiations (Schimmelfennig, Citation2018), this should also be reflected in media coverage of the issue in the UK and beyond. Moreover, if European elections have indeed developed into more than just second order elections, this should also be visible in terms of increased attention to genuine EU issues such as FMP.

Finally, apart from changes in overall salience, we might also observe shifting topics associated with FMP over time. Studies on the media coverage of migration have developed different categorizations of these broader topics, often also conceptualized as ‘frames’ (see e.g., Balabanova & Balch, Citation2010) or ‘narratives’ (see e.g., Caviedes, Citation2015). One common distinction is between economic, cultural and security considerations associated with migration (Eberl et al., Citation2018, p. 211). Within each category, some studies also distinguish between positive and negative positions (Eberl et al., Citation2018, p. 211), between ‘frames’ and ‘counter-frames’ (Danaj & Wagner, Citation2021) or between ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘communitarian’ arguments (Balabanova & Balch, Citation2010; Roos & Westerveen, Citation2020). Since our focus is on FMP, we do not expect all kinds of migration topics to be equally relevant. We anticipate fewer cultural and security topics which are more relevant in discussions of external migration from less secure and culturally less similar regions than other EU member states (cf. Balch & Balabanova, Citation2016, p. 29). By contrast, economic topics should feature prominently in public debate about FMP. EU membership entails exceptionally far-reaching economic rights (Ruhs, Citation2015), combining unrestricted labour mobility, including low-skilled workers (Blinder & Markaki, Citation2018, p. 9), and the principle of non-discrimination, which makes the issue of cross-border welfare access particularly contentious (Cappelen & Peters, Citation2018, p. 1339). While questions of labour market access had already been a major issue during accession negotiations and led to transitional arrangements, it took more time until questions of welfare access of EU citizens became the subject of expansive jurisprudence of the European Court of Justice (CJEU) on ‘social citizenship’ (Schmidt et al., Citation2018). This development might also be reflected in shifting topics associated with FMP in the public debate, e.g., from concerns about ‘social dumping’ to ‘welfare migration’.

Variation across countries

Research on EU politicization and immigration has identified a range of potential explanations for country-level variation, such as socio-economic conditions (Vasilopoulou & Talving, Citation2019), strategic party competition (Grande et al., Citation2019) or institutional misfit (Leupold, Citation2016). In the following, we propose two explanations which are tailored to the specific context of intra-EU mobility, while following the abstract distinction between politicization as resulting from ‘objective’ pressures or from political choices (Grande et al., Citation2019, p. 1454).

As regards ‘objective’ pressures, intra-EU mobility has risen steadily since Eastern enlargement, but mobility levels and dominant patterns of mobility differ considerably at the country-level. We may expect differences in the salience of FMP depending on different levels of cross-border mobility. Even more importantly, intra-EU mobility is highly asymmetric between member states with Western member states being predominantly destination countries and Eastern member states being predominantly emigration countries (Vasilopoulou & Talving, Citation2019, p. 810).

The implications of this asymmetry for politicization are not straightforward. At the individual level, FMP is likely to be evaluated largely positively in emigration countries, where it is broadly endorsed in terms of greater individual freedom, potential concerns for the working conditions of mobile EU citizens notwithstanding (Balabanova & Balch, Citation2010, p. 385). In destination countries, by contrast, FMP may be perceived as a threat by some parts of society (Lutz, Citation2021; Vasilopoulou & Talving, Citation2019). If these individual attitudes prevail, we should therefore expect greater and more critical public debate about FMP in Western destination countries. At the societal level, however, the costs and benefits of mobility are distributed very differently. Despite concerns about alleged ‘welfare migration’ (Blauberger & Schmidt, Citation2014), the fiscal impact of intra-EU mobility has been found to be clearly positive in destination countries (Dustmann & Frattini, Citation2013). By contrast, while emigration can relieve the domestic labour market, societal concerns about depopulation and a ‘brain drain’ from emigration countries have grown and have led to political calls for EU budgetary compensation for these costs of emigration (Bruzelius, Citation2021, p. 937). Hence, depending on whether individual or societal concerns dominate the public debate, we should see greater politicization in destination or emigration countries. In any case, we expect to encounter divergent topics associated with FMP in destination and emigration countries.

As regards political explanations, we consider different policy styles as another reason for cross-country variation of FMP politicization. The concept of ‘policy styles’ (Richardson et al., Citation1982) has a long tradition in policy studies and has attracted renewed interest in recent years (Howlett & Tosun, Citation2018). We draw on the basic notion of different policy styles – anticipatory or reactive, consensus-seeking or impositional – to account for cross-country differences in politicization. Whereas EU member state governments often share an interest in depoliticizing EU policies at home (Bressanelli et al., Citation2020), they may experience different trajectories of (de)politicization depending on different policy styles. At one end of the spectrum, member state governments may seek to proactively limit EU politicization by an anticipatory and consensus-seeking policy style. By contrast, at the other side of the spectrum, politicization may occur later, but ‘escape’ government control when a reactive and impositional policy style is adopted. In between these two types, one can also imagine combinations of anticipatory and impositional or reactive and consensus-seeking policy styles with less clear implications for (de)politicization.

An anticipatory policy style towards FMP is well described in a study on Dutch administrative adaptations to EU enlargement, acting ‘in anticipation of possible problem pressure stemming from the inflow of Union citizens (in order) to find “a real solution to a perceived problem”’ (Kramer et al., Citation2018). Against this background, we expect earlier, but less pronounced, politicization of FMP in those countries which introduced transitional arrangements restricting worker mobility from new EU member states, and which implemented EU rules on cross-border welfare access restrictively (Roos, Citation2019). In a similar vein, politicization of FMP is likely to be lower in countries which seek to actively ‘contain compliance’ (Conant, Citation2002) with the jurisprudence of the CJEU, i.e., finding creative ways to apply expansive case law in as minimalist a way as possible (Heindlmaier & Blauberger, Citation2017).

By contrast, we expect a reactive and impositional policy style to allow for, or even spur, greater politicization of FMP at a later stage. Such a policy style builds on executive decision-making rather than broad public consensus-seeking and responds to problem-pressure rather than solving possible problems ex ante. As regards FMP, this implies an absence of transitional arrangements or other measures seeking to proactively protect domestic labour markets and welfare systems, e.g., by strictly enforcing high labour standards (Ruhs, Citation2015) or limiting cross-border welfare access. Once FMP has become politicized, however, reactive measures to limit worker mobility or to counter alleged ‘welfare migration’ may even reinforce politicization (Roos, Citation2019). Moreover, by faithfully implementing CJEU jurisprudence as policy, a reactive approach actually increases the impact of expansive case law and potentially also its politicization. Such a policy towards the CJEU was, for instance, identified in Denmark, traditionally characterized as ‘law-observant’, where only the strong politicization of cross-border access to social benefits led to restrictive measures (Kramer et al., Citation2018).

Research design, case selection and methods

To study the debate on FMP across time and space, we carried out an analysis of news articles in Austria, Germany, Poland and the UK. With this country selection, we can test the expectations raised in the theoretical section not only concerning variation over time, e.g., major events such as enlargements, but also concerning variation across countries. With regard to mobility patterns, we expect variation between Germany, Austria and the UK, as main countries of destination, and Poland, as one of the main countries of emigration and posting, in terms of intra-EU mobility (European Commission, Citation2021, p. 36). While Austria, Germany and the UK are similar with respect to mobility trends, their policy styles concerning FMP differ almost ideal-typically. Austria and Germany adopted an anticipatory and consensus-seeking policy style, following the demand of trade unions to introduce transitional periods for workers from new EU member states after 2004, as well as actively limiting the access of (non-active) EU citizens to its welfare systems (Heindlmaier & Blauberger, Citation2017; Roos, Citation2019). By contrast, the British decision to guarantee full free movement to workers without transitional arrangements in 2004 was based on expert advice rather than broad public debate, and was only revised in 2007 in light of an unanticipated inflow of mobile workers and rising opposition (Balch & Balabanova, Citation2016). We included Austria mainly as a control case with regard to the potential influence of strong radical right parties. If they drive the politicization of FMP, we should see similarities between Austria, with the long-standing presence and strength of the Freedom Party (FPÖ), and the UK (UKIP), and differences in the German debate, given that the Alternative for Germany (AfD) emerged more recently.

Since we are interested in the long-term trend since the time of the Treaty of Maastricht, which is often considered a crucial moment for the politicization of the EU (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009), we collected data from 1990 to 2019. Our analysis covers all national and regional, daily and weekly newspapers, as well as news magazines, which were available in the relevant national databases (for the databases and full list of sources, see Annex I). Whereas most Austrian, German and British sources were available from 1990, our earliest Polish source dates to 2001, allowing us to include the immediate period prior to EU accession in our analysis. By including both quality newspapers and magazines, and tabloids, our corpus is expected to reflect the whole spectrum of discussions in the four member states and to provide a good ‘indicator of the “public debate”’ (Balch & Balabanova, Citation2017, p. 237). A first step consisted of determining adequate search words to allow us to find the articles dealing with FMP via the national databases: these search words were neutral terms related to free movement, posting of work and labour mobility in the EU (see Annex II). We explicitly did not include the term migration to avoid articles dealing with migration in general, rather than intra-EU mobility in particular (see also Morrison, Citation2019, p. 600).

Having established our corpus of data, we combined the advantages of quantitative and qualitative media analysis (cf. Caviedes, Citation2015, p. 901) by employing structural topic models (STM, Roberts et al., Citation2019) as well as manual coding of sample articles. Topic models follow the idea that each document (here news article) belongs to a particular theme (topic). The most prominent topic model is Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) which assumes first, that each text document is a mixture of a priori unknown topics, and second, that the topics differ by the frequency with which specific sets of words appear (Blei et al., Citation2003). In what follows, we use STM (for a detailed description, see Roberts et al., Citation2016) which extend LDA in two ways: Firstly, they allow that the prevalence of topics in the documents might vary over time and secondly, that external covariates like author or newspaper might influence the distribution of words within a topic. Put differently, STM combine three ingredients: (1) a topic prevalence model which controls the appearance of topics depending on covariates, (2) a topical content model, which controls the frequency of the terms in each topic as a function of covariates and (3) the language model, which combines (1) and (2) and models the words in each document.

As concerns the critical task in STM of identifying the number of topics, we used the algorithm proposed by Lee and Mimno (Citation2014) to automatically detect the number of topics in our newspaper corpora by projecting the word-co-occurrence matrix into a lower dimensional space. We want to emphasize that there is no ‘true’ number of topics in automated text analysis (Roberts et al., Citation2019). After several pre-processing steps, in which we removed stop words and articles with a similarity above 98 per cent for Austria, Germany and the UK and, due to a larger share of quasi-duplicates, 90 per cent for Poland, we estimated an independent STM for each country in our sample. Afterwards, we interpreted the topics by human judgement in the following way: first, the topical content part was used to identify the main theme of each topic. Topics are illustrated as word clouds (see Annex III), which display the most frequent terms of each topic and provide information on their distribution over time and their proportion. For example, if a specific topic has the most frequent terms ‘EU citizens, benefits, welfare, … ’, it nourishes the hypothesis that this topic is about welfare access for EU citizens. We dropped topics which were obviously unrelated to our research object, e.g., word clouds clustering around the names of individual newspapers or the titles of newspaper sections, leaving us with 35 topics in total – 6 in Austria, 10 in Germany, 11 in Poland and 8 in the UK.Footnote1 Secondly, to allow for a deeper validation of our topics and for deepening our substantive understanding, we used the topic prevalence part of our model. For each document it returned a vector with the probabilities that a specific document belonged to a certain topic. We extracted a sample of 20 articles per topic with a high assignment-probability to the specific topic as the basis of our qualitative content analysis.

In our qualitative analysis, we coded this sample of 20 articles for each of the 35 topics, i.e., a total of 700 articles with MaxQDA according to a relatively simple scheme comprising four clusters of codes. Based on our expectation to mostly find economic topics associated with FMP, we derived two clusters of codes regarding labour markets and welfare access, both sub-divided into restrictive and permissive arguments (similar to the distinction between positive and negative frames discussed above). For example, arguments about mobile EU citizens constituting an unreasonable burden on national welfare systems were coded as ‘welfare access, restrictive’, whereas arguments about removing bureaucratic obstacles to the posting of workers were subsumed under ‘labour markets, permissive’. In addition, we developed two further clusters of codes inductively. Despite our narrow search for articles on FMP, we found a significant share of articles with statements related to migration more generally (mainly from the UK, see below) for which we developed a cluster of codes on migration with sub-codes on sovereignty, crime and security and refugees. Lastly, while we only coded statements related to political actors (cf. Grande et al., Citation2019, p. 1450) for the first three clusters of codes, we developed a fourth cluster of information codes, which we assigned to articles lacking any actor statements and principally reporting the practical and legal aspects of FMP (which we found mainly in Poland, see below).

Empirical analysis

In the following, we present our empirical results first with respect to variation over time and secondly in terms of cross-country variation.

Punctuated politicization and shifting topics associated with FMP

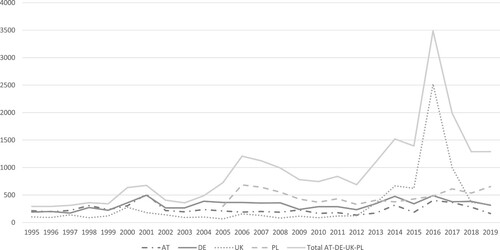

As regards overall salience, shows an overall increase in news coverage of FMP, but this finding has to be interpreted with caution, since we were only able to include most Polish news from 2005. More importantly, the observed trend towards greater politicization is not continuous, but punctuated. We identify four temporal peaks, partly driven only by some countries, in 2001, 2006, 2014 and 2016 which can be traced back to individual events:

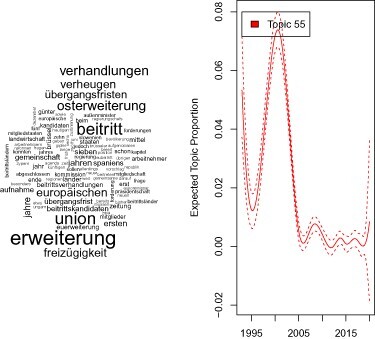

(1&2). Unsurprisingly, EU accession negotiations and the approaching Eastern enlargement of the EU gained particular attention in Germany and Austria in 2001 (Topics DE-55, AT-58). Articles refer to the EU-wide controversy during which Germany and Austria notably pushed for transitional arrangements. A second, closely related peak in salience of FMP around 2006 is largely driven by our data from Poland (Topic PL-55, Article PL-1). Soon after EU accession, the debate there was about countries that might suspend, loosen, or had already suspended the transitional arrangements, such as Spain, France and Sweden. What is striking is the absence of any notable increase in attention to FMP issues in the UK just before or after EU Eastern enlargement.

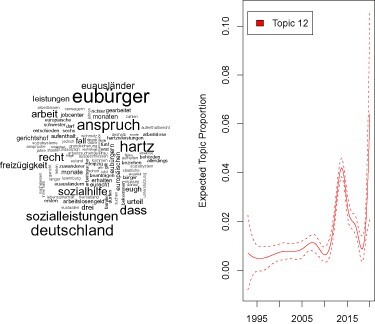

(3). The third peak is to be seen in the light of the elections to the European Parliament and the end of the transitional arrangements regarding the free movement of Romanians and Bulgarians in a range of member states in 2014. In Germany and Austria, we find topics related to ‘welfare migration’, i.e., discussions about access of (non-active) EU citizens to social benefits (Topics DE-18, AT-57). Prior to the EU election, for instance, the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU) fuelled the debate with fierce calls for restricting cross-border welfare access: ‘The CSU is not against the immigration of well-qualified workers. But there must be rules to protect against abuse and injustice … Germany is not the social repair shop of Europe’ (Article DE-1).

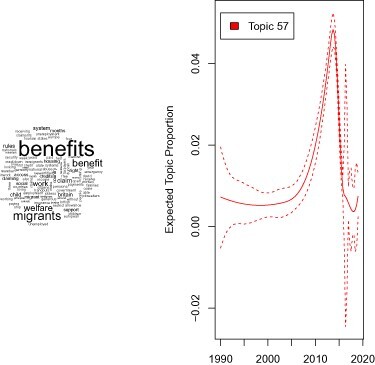

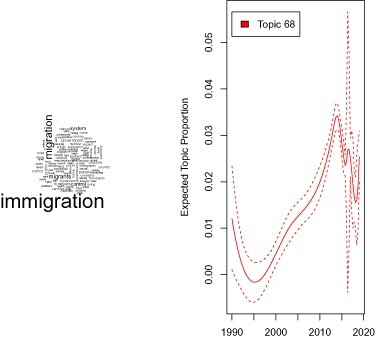

(4). In 2016, the Brexit referendum directed particular attention towards the issue of FMP, with 1112 articles related to FMP in just the top two national quality papers. Articles covered a whole range of interrelated topics on labour mobility, the single market and European citizenship (Topic UK-80), but often centred around reducing migration from the EU, as well as third countries more generally (Topic UK-68). Theresa May concluded ‘that the vote … on June 23 sent a very clear message about immigration; that people want control of free movement from the EU … We need to bring net migration down to sustainable levels’ (Article UK-1). Brexit attracted attention not only in the UK, but also in other member states (Topics DE-42, AT-63, PL-75).

Figure 1. Salience of free movement of people from 1995 to 2019, by number of relevant articles in available sources in the member states; data from Poland only since 2005 (see Annex I).

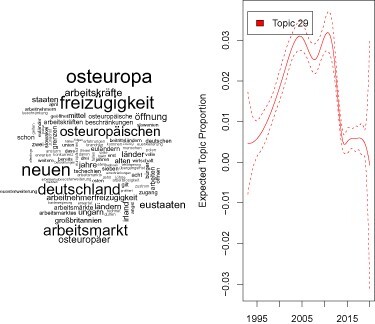

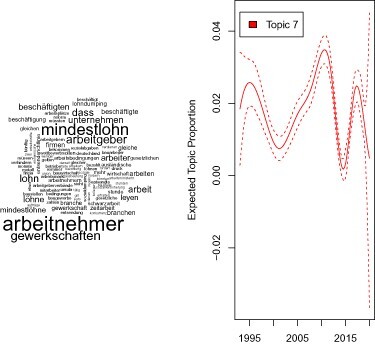

Apart from changes in overall salience, we observe shifting topics of FMP over time. If there was a debate around Eastern enlargement in member states of destination, topics discussing FMP in terms of its labour market effects dominated (see for Germany , Topic AT-58). Many articles discussed the threats and benefits of labour mobility to Germany as a consequence of Eastern enlargement. Besides worker mobility, freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services were also included in these debates, e.g., regarding the posting of workers 2006 (Topics DE-2, AT-43). By 2010, labour mobility in the EU was again increasingly subject to debate in Germany in terms of skills shortages, and the need for foreign workforce in the care, health and manufacturing sectors (Topic DE-10), as exemplified by this statement:

The rising immigration figures, especially from the Southern European crisis states, show that the EU freedom of movement is a success … Everyone benefits: Germany can reduce the shortage of skilled workers in certain sectors, EU citizens find work and ease the burden on the labour market in their home countries. (Article DE-2)

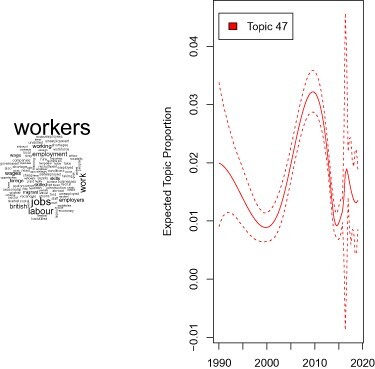

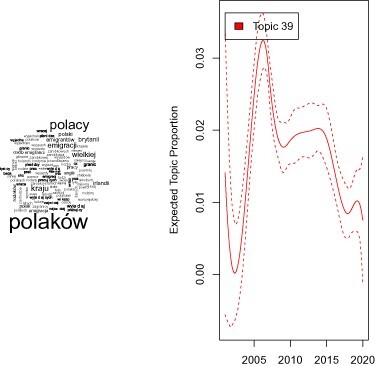

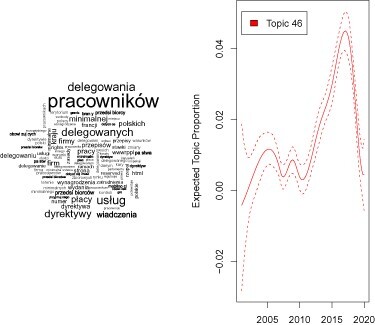

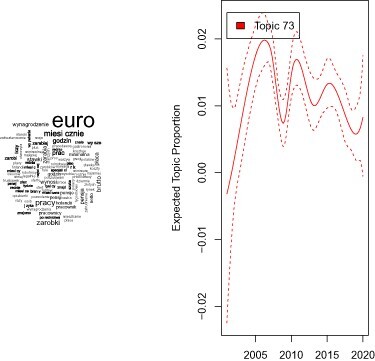

In the UK, labour market topics gained in importance some years later () and mainly revolved around job competition. A trade union representative formulated it as follows: ‘This is a fight for work. It is a fight for the right to work in our own country’ (Article UK-2). In Poland, the topic of emigration was especially salient around 2006, i.e., shortly after EU enlargement (). Articles associated with this topic reported the number of people trying to find work abroad as well as the main destination countries.

Topics discussing FMP in the context of welfare policies only occurred later in the three member states of destination (DE: , analogous AT-57, and UK: below), with a peak in 2014 related to discussions about ‘welfare migration’ or ‘benefit tourism’ (Blauberger & Schmidt, Citation2014). More recently, a similar topic concerning the export of child benefits attracted sudden and significant attention in Germany and Austria (Topics DE-49, AT-64). Restrictive arguments were shared across a wide political spectrum, as demonstrated by the initiative of Sigmar Gabriel, then leader of German Social Democrats, aiming ‘at unemployed Romanians and Bulgarians who are only lured to Germany for child benefits and are housed here in dilapidated houses. This is modern human trafficking, Gabriel said at a press conference in Berlin’ (Article DE-3). By contrast, the debate about ‘welfare migration’ was almost completely absent from our Polish data with no Polish topic on welfare access emerging from our quantitative analysis and a share of less than 3 per cent of Polish codings related to welfare access. Tellingly, we found the best quote on the Eastern European ‘debate’ on the indexation of child benefits in our Austrian text corpus:

The responsible ministers in Czechia and Slovakia also criticize the measure as violating EU law. However, the topic runs ‘far from the headlines’ and is of surprisingly little interest in the public debate, as Hungarian journalists confirm to the KURIER. (Article AT-1)

By contrast, if cross-border welfare issues were a subject in Poland at all, news articles provided practical information on the coordination of social security for Poles working abroad (Topic PL-2, for details on the technical character of the Polish debate see below).

Although labour market topics were largely superseded by welfare topics in Germany, Austria and the UK around 2014, they regained importance more recently, mainly in the context of the revision of the Posted Workers Directive, which was negotiated from 2016 to 2018 ( and ). In Germany and Austria, the debate about posted work was about ‘social dumping’ and how the reform could counter it, as the existing rules were ‘so full of holes that social standards are undermined and people are exploited in countries like Germany or France’ according to trade unions (Article DE-4). In contrast, Polish articles – apart from neutral reports – argued against the planned reform of the Directive (), e.g., by highlighting that ‘the directive will lead to increased legal ambiguity and higher costs for companies sending out workers’ (Article PL-2).

In sum, we find shifting topics associated with FMP in the public debate (from labour markets to welfare access) in the three Western member states included in our analysis. This development may partly be explained by the fact that cross-border access to national welfare systems became only incrementally established by the expansive jurisprudence of the CJEU. Topics related to the labour market returned in recent years, with a slightly different focus on posted work and political attempts to rebalance free movement and social protection.

Anticipatory de-politicization of FMP in Germany and Austria, reactive politicization in the UK

Despite similar mobility trends as main destination countries, both the timing and the scope of politicization differ greatly between Germany and Austria on the one hand, and the UK on the other hand ( above). In Germany and Austria, the potential effects of EU Eastern enlargement were discussed broadly prior to the accession of new member states and temporary restrictions of FMP were introduced. By contrast, FMP was hardly a topic in the UK before 2013, which is all the more striking since the UK experienced the consequences of EU enlargement much more immediately without transitional arrangements in 2004, and with public concerns only rising prior to the phasing-out of transitional arrangements for workers from Bulgaria and Romania in 2014 (for a detailed overview of the different approaches in Germany and the UK, see also Roos, Citation2019).

In Germany and Austria, we find early but moderate politicization of FMP precisely when transition periods were discussed (; Topic AT-58). News articles discuss both fears about being flooded with cheap labour, as well as hopes that the country would benefit from mobility due to its own aging population. The German government anticipated potentially negative consequences to the labour market of Eastern enlargement, especially because of the country’s proximity to Poland and the Czech Republic. In 1998, the Minister for Employment at that time, Norbert Blüm, warned of a ‘mass migration’ of 340,000–680,000 Eastern Europeans per year to the ‘old’ member states if Germany did not introduce transitional arrangements (Article DE-5). While it was later clarified that this interpretation was incorrect, the threat of EU enlargement without restrictions remained in the heads of Germans. For instance, Commissioner Günter Verheugen asked for understanding of Germans’ concerns in the Polish newspaper Rzeczpospolita: ‘Please imagine the fears of the Germans who think that the day after Poland's EU accession five million job-seeking Poles will cross the border to Germany’ (Article DE-6). The transition phase did not only limit the negative effects of EU enlargement on the country’s labour market, but also restrained politicization in Germany. Similarly, the Austrian decision to require transition periods was motivated by a broad consensus to avoid a public backlash against FMP:

The general secretary of the Federation of Austrian Industries admits that companies would prefer not to have a transition period. However, ‘in order to allay citizens’ fears and to promote acceptance for enlargement, we are in favour of transition periods. (Article AT-2)

In contrast, the UK largely fits the pattern of impositional and, arguably, reactive policy making, at least regarding broader public concerns beyond the economic benefits of FMP. The British decision to refrain from transitional arrangements in 2004 was part of Labour’s strategy of ‘managed migration’ (Somerville, Citation2007, p. 29, 34). It was not the result of a broader public debate about the consequences of opening the labour market to workers from Central and Eastern Europe, but drew mainly on expert advice meant to ‘neutralise a topic that had previously been politically and electorally toxic’ by a ‘technocratic turn’ (Balch & Balabanova, Citation2016, p. 21). If transition periods in other EU member states were an issue at all, they were broadly repudiated, as the following quote from the Tory Spokesman in the European Parliament illustrates: ‘Old Europe's reluctance to open its labour market to new EU states is symbolic of its failure to adapt to the globalised world’ (Article UK-3).

However, the British government underestimated the number of people coming to the UK as well as public backlash (see also Toshkov & Kortenska, Citation2015), and changed its policy before the EU accession of Bulgaria and Romania in 2007. When transitional arrangements for workers from these two countries were phased out in 2014, this served as a catalyst for an intense debate with wide-ranging politicization, eventually escalating around the time of the Brexit referendum. The lack of transitional arrangements in 2004 was considered a failure, e.g., by the Tory Minister of State for Immigration Damian Green: ‘That was the huge mistake in 2004 and it was compounded by the fact that very few other countries made that mistake’ (Article UK-4). Since this negative assessment was widely shared, Labour had to partly renounce its own policy while in government (Balch & Balabanova, Citation2016, p. 22).

The British debate on ‘benefit tourism’ () is similar to concerns about alleged ‘welfare migration’ in Germany () and Austria, but was more lopsided, and articles related to this topic often include heavily discriminatory language (Article UK-5). Permissive welfare codes made up only a share of around 9 per cent of all welfare codes in the UK corpus, in contrast to around 40 per cent in Austria and Germany. The restrictive turn was also noted abroad, e.g., with flagrant self-praise by the Austrian Minister of Social Affairs, claiming that ‘Austria's regulation for access to social benefits is considered best practice throughout the EU. A few days ago, a British governmental official visited the ministry as they wanted to copy the rules for England’ (Article AT-3).

Even more strikingly, despite our narrow search for articles on FMP, and in contrast to our other country cases (with only some reference to security themes in topics AT-42 and DE-22), the analysis of our British text corpus yields several topics revolving around general questions of migration (e.g., ), and mixes up intra-EU mobility with third country migration, including ‘illegal migration’ (Topic UK-35). In our qualitative analysis of UK articles, migration codes made up a share of almost 40 per cent, compared to 8 per cent in Germany and 6 per cent in Austria. This points to the issue-linkage of intra-EU mobility and migration (Roos, Citation2019) and to the great importance of reducing net migration in the context of Brexit (Goodwin & Milazzo, Citation2017). At the core of the debates were often security- and sovereignty-related arguments about ‘taking back control’ over migration (Article UK-6) and over national welfare systems (Article UK-7; see also ), which could only be achieved outside the EU (Article UK-8). This ‘conflation’ (Morrison, Citation2019, p. 596) or even ‘conflagration’ (Balch & Balabanova, Citation2017, p. 238) of FMP and general migration issues is well exemplified by a citation from Dominic Raab shortly before the Brexit referendum:

This is yet more evidence of how EU membership makes us less safe. Free movement of people allows unelected judges in the rogue European court to decide who we can and can’t deport. This puts British families at risk (…). Outside the EU, we can take back control of our borders, deport more dangerous criminals, and strengthen public protection. (Article UK-9)

While UKIP played a role in the escalation of politicization in the UK, the presence of a strong radical right party cannot solely account for the politicization, as the comparison with Austria and Germany demonstrates. Contrary to what one might expect from a party politics perspective, the salience of FMP and the topics associated with FMP were largely identical in Austria and Germany – despite the absence of a strong radical right party in Germany until recently and the long-established presence of the Freedom Party (FPÖ) in Austria. Even though the FPÖ also mobilized the issue (Topic AT-61), Austria still succeeded in de-politicizing FMP. This further corroborates our explanation regarding policy styles, and also fits with similar findings on how public debates on alleged ‘welfare migration’ resulted in a re-establishment of the legitimacy of FMP in Germany, but escalated into a fundamental critique of the EU in the UK (Danaj & Wagner, Citation2021, p. 22).

A distinct emigration perspective from Poland

Finally, we compare the politicization of FMP in destination countries to the public debate in Poland, a major emigration country in terms of intra-EU mobility.

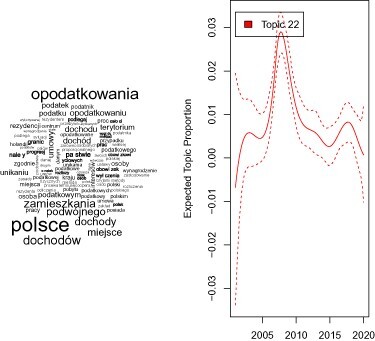

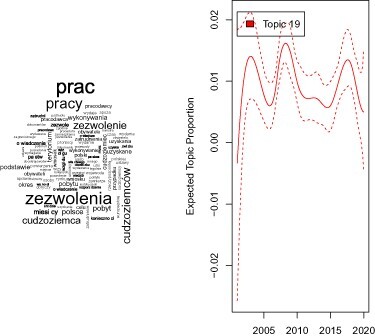

We identified two larger groups of topics that were only relevant in the Polish debate about FMP, but hardly mattered in Western Europe. One set concerns practical issues (rather than polarized political debates) for mobile workers. Whereas 47 per cent of Polish codes concern practical and legal advice, this was only the case for 5 per cent of codes in Austria and 2 per cent in Germany. We find topics related to information and practical advice for job searches abroad and about the necessity of language skills for working or studying purposes. For example, one word cloud on labour and earnings () contains articles – mainly dating back to Polish EU accession or to the phasing out of transition arrangements – that discuss work opportunities and job portals in Western and Northern EU member states and average wages for certain occupations, e.g., harvest work or transport (see Article PL-3). Another set of practical issues only discussed in Polish news about FMP are matters of the taxation of mobile EU citizens (). Several word clouds draw on articles dealing with the taxation of Polish residents working abroad and giving detailed advice about obligations and double taxation treaties, e.g., for workers returning to Poland after working in Ireland aiming to avoid double taxation (Article PL-4). Another topic concerns the coordination of child benefits between member states, but from a technical point of view and against the background of the reform of Polish child benefits in 2016 (Topic PL-26). For example, articles inter alia explain that an eligibility assessment for families that applied for Polish child benefits may take longer if the father or mother works abroad due to the rules on coordination of social security, and ministerial representatives responded to illustrative individual readers’ cases in a question-answer column (Article PL-5). Hence, our analysis of Polish news articles clearly shows a greater interest in the individual opportunities and challenges associated with FMP from an emigration perspective.

As a counterpart to the discussion about individual opportunities and practical issues abroad, we identified a second set of topics only relevant in Poland, which address the challenges of (mass) emigration – yet to a lesser degree than expected, and from a rather neutral perspective. Articles deal with the careers of mobile Polish workers, e.g., becoming successful managers abroad, but facing difficulties in finding an adequate job when planning to return to Poland (Topic PL-67). Another word cloud on health and doctors mainly comprises articles on the ‘alarming … outflow of specialists with professional experience’ leading to a lack of staff in the Polish health sector (Article PL-6, Topic PL-30). Furthermore, intra-EU emigration from Poland is also linked to (the need for) an incoming labour force from Poland’s Eastern neighbours. Several word clouds revolve around labour force and foreigners, in particular Ukrainians (for example ), and these word clouds reflect the discussion about the consequence of Polish emigration, shortages of labour, and the resulting need for foreign workers. Articles also contain practical advice on how to employ people from the Ukraine, Belarus, or Russia. The discussion was particularly intense after 2006, when Poland made it easier for foreigners to enter its labour market with the Declaration of intent to employ foreigners, and regained attention around 2018, when the system was reformed.

The only political debate in Poland, which is closer to the topics in the destination countries, concerns the reform of the Posted Workers Directive. While posted work is salient in both destination and emigration countries, its critical connotation differs between a debate about ‘social dumping’ in Germany and Austria and about potential restrictions to free movement in Poland. To illustrate, we find that 62 per cent of the Polish codes concerning the European labour market favour the reduction of bureaucratic hurdles and easier access.

To sum up, mobility trends matter and topics in emigration and destination countries differ. As expected, the debate in destination countries mostly revolved around questions of welfare distribution and job competition, hence containing both individual and societal concerns, yet also the need for skilled workers. In contrast, we identify a Polish debate that largely emphasizes the ‘better life’ abroad, hence the individual perspective. Unexpectedly, the Polish debate was not so much about a ‘brain drain’ or further consequences of EU enlargement for Poland. This could be the case because third country nationals, particularly from Ukraine, compensated for Polish emigration to a certain degree. Another explanation might lie in the focus on the short-term benefits and challenges of emigration, with long-term consequences regarding pension systems or possible labour shortages gaining prominence in the societal discourse more slowly. This also fits with the findings of Vasilopoulou and Talving (Citation2019) that individual attitudes in richer member states are more divided into pro and contra FMP, and hence more polarized, in contrast to more coherently positive attitudes in poorer member states.

Conclusion

Politicization of FMP is differentiated: salience, polarization and topics vary across time and between the countries. Events with significant implications for FMP, such as EU enlargement or the phasing out of transitional arrangements, attracted particular attention and accounted for punctuated salience across countries. Strikingly, in contrast to the UK with its reactive and impositional policy style regarding FMP, there was an earlier, yet moderate, politicization of FMP in Germany and Austria, which had anticipated EU enlargement and had sought to establish broad consensus by introducing transition arrangements. From 2013 on, the British discussion escalated, with FMP being a core issue, largely framed in more general terms of (limiting) migration, both in the run-up to the Brexit referendum and during the UK’s negotiations about leaving the EU. While UKIP heavily mobilized the issue, the presence of a strong radical right party alone cannot account for politicization of FMP, as demonstrated by the Austrian case. Our findings confirm that policy styles matter.

We considered both salience and polarization to be necessary elements of politicization, and our analysis of the Polish cases showed why this matters. While FMP was salient from the Polish emigration perspective, the public ‘debate’ was hardly polarized. Many articles dealt with technical issues and practical information, e.g., on taxes or language skills. This lack of polarization came partly as a surprise and we only have tentative explanations. One the one hand, many of the societal costs of large-scale emigration will only become visible in the longer run and, therefore, might preoccupy some experts and policy-makers rather than the broader public. On the other hand, third country immigration to Poland may have partly compensated for the outflow of Polish citizens since EU accession. This illustrates again the need for further research which adopts an emigration perspective (Bruzelius, Citation2021).

Our careful case selection, including Austria as a control case regarding the role of strong radical right parties, and the combination of quantitative and qualitative methods were meant to ensure the generalizability of our findings, but further research will certainly be required. For instance, while the media was not the focus of our study, our data reveals differences between newspapers, suggesting that FMP is especially salient in conservative quality newspapers. Finally, while we selected typical cases with regard to mobility trends and policy styles, further research could probe our arguments by analysing the debate in extreme cases such as Romania, which had high levels of net emigration without comparable third country immigration as in Poland, or less typical, ambivalent cases, e.g., Sweden, which also did not introduce transition arrangements in 2004, yet had much stricter labour regulation and enforcement than the UK (Ruhs, Citation2015, p. 18), or Italy, which can be classified as both a country of destination and of intra-EU emigration.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (1.7 MB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank JEPP’s anonymous reviewers and Cecilia Bruzelius, Andreas Dür, Markus Gastinger, Leila Hadj-Abdou and Susanne K. Schmidt for their very helpful comments. Funding for this article by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) is gratefully acknowledged [grant number I 4064].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Blauberger

Michael Blauberger is Professor for Politics of the European Union at the University of Salzburg.

Anita Heindlmaier

Anita Heindlmaier is Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Salzburg.

Paul Hofmarcher

Paul Hofmarcher is Assistant Professor in Economics at the University of Salzburg.

Josephine Assmus

Josephine Assmus is Doctoral Researcher at the University of Bremen.

Birgit Mitter

Birgit Mitter is Doctoral Researcher at the University of Salzburg.

Notes

1 For reasons of space, we only include some topics as word cloud figures in this text and refer to additional topics included in Annex III. Similarly, we can only quote from a selection of news articles, listed in Annex IV.

References

- Balabanova, E., & Balch, A. (2010). Sending and receiving: The ethical framing of intra-EU migration in the European press. European Journal of Communication, 25(4), 382–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323110381005

- Balch, A., & Balabanova, E. (2016). Ethics, politics and migration: Public debates on the free movement of Romanians and Bulgarians in the UK, 2006–2013. Politics, 36(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12082

- Balch, A., & Balabanova, E. (2017). A deadly cocktail? The fusion of Europe and immigration in the UK press. Critical Discourse Studies, 14(3), 236–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2017.1284687

- Bauböck, R. (2019). Debating European Citizenship. Springer.

- Blauberger, M., Heindlmaier, A., & Kobler, C. (2020). Free movement of workers under challenge: The indexation of family benefits. Comparative European Politics, 18(6), 925–943. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-020-00216-3

- Blauberger, M., & Schmidt, S. K. (2014). Welfare migration? Free movement of EU citizens and access to social benefits. Research & Politics, 1(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168014563879

- Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993–1022. https://doi.org/10.5555/944919.944937

- Blinder, S., & Markaki, Y. (2018). Public attitudes toward EU mobility and non-EU immigration: A distinction with little difference, Oxford: Reminder Working Paper.

- Boomgaarden, H. G., & Vliegenthart, R. (2009). How news content influences anti-immigration attitudes: Germany, 1993–2005. European Journal of Political Research, 48(4), 516–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01831.x

- Bressanelli, E., Koop, C., & Reh, C. (2020). EU actors under pressure: Politicisation and depoliticisation as strategic responses. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1713193

- Bruzelius, C. (2021). Taking emigration seriously: A new agenda for research on free movement and welfare. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(6), 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1768280

- Cappelen, C., & Peters, Y. (2018). Diversity and welfare state legitimacy in Europe. The challenge of intra-EU migration. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(9), 1336–1356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1314534

- Caviedes, A. (2015). An emerging ‘European’ news portrayal of immigration? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(6), 897–917. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.1002199

- Conant, L. (2002). Justice contained: Law and politics in the European Union. Cornell University Press.

- Danaj, S., & Wagner, I. (2021). Beware of the “poverty migrant”: media discourses on EU labour migration and the welfare state in Germany and the UK. Zeitschrift für Sozialreform, 67(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1515/zsr-2021-0001

- de Wilde, P., Leupold, A., & Schmidtke, H. (2016). Introduction: The differentiated politicisation of European governance. West European Politics, 39(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1081505

- Dustmann, C., & Frattini, T. (2013). The Fiscal effects of immigration to the UK. University College.

- Eberl, J.-M., Meltzer, C. E., Heidenreich, T., Herrero, B., Theorien, N., Lind, F., Berganza, R., Boomgaarden, H. G., Schemer, C., & Strömbäck, J. (2018). The European media discourse on immigration and its effects: A literature review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 42(3), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2018.1497452

- European Commission. (2021). Annual Report on intra-EU labour mobility 2020, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Goodwin, M., & Milazzo, C. (2017). Taking back control? Investigating the role of immigration in the 2016 vote for Brexit. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(3), 450–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117710799

- Grande, E., & Kriesi, H. (2016). Conclusions: The postfunctionalists were (almost) right. In S. Hutter, E. Grande, & H. Kriesi (Eds.), Politicising Europe (pp. 279–300). Cambridge University Press.

- Grande, E., Schwarzbözl, T., & Fatke, M. (2019). Politicizing immigration in Western Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(10), 1444–1463. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1531909

- Heindlmaier, A., & Blauberger, M. (2017). Enter at your own risk: Free movement of EU citizens in practice. West European Politics, 40(6), 1198–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1294383

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Howlett, M., & Tosun, J. (2018). Policy styles and policy-making: Exploring the linkages. Routledge.

- Kramer, D., Sampson Thierry, J., & van Hooren, F. (2018). Responding to free movement: Quarantining mobile union citizens in European welfare states. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(10), 1501–1521. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1488882

- Lee, M., & Mimno, D. (2014). Low-dimensional embeddings for interpretable anchor-based topic inference. In A. Moschitti, B. Pang, & W. Daelemans (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) (pp. 1319–1328). Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Leupold, A. (2016). A structural approach to politicisation in the Euro crisis. West European Politics, 39(1), 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1081510

- Lutz, P. (2021). ‘Loved and feared: Citizens’ ambivalence towards free movement in the European Union’. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(2), 268–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1720782

- Morrison, J. (2019). Re-framing free movement in the countdown to Brexit? Shifting UK press portrayals of EU migrants in the wake of the referendum. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 21(3), 594–611. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148119851385

- Recchi, E. (2008). Cross-state mobility in the EU. European Societies, 10(2), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616690701835287

- Richardson, J., Gustafsson, G., & Jordan, G. (1982). The concept of policy style. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Policy styles in Western Europe (pp. 1–16). Allen & Unwin.

- Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Airoldi, E. M. (2016). A model of text for experimentation in the social sciences. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 111(515), 988–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2016.1141684

- Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Tingley, D. (2019). Stm: An R package for structural topic models. Journal of Statistical Software, 91(2), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v091.i02

- Roos, C. (2019). The (de-) politicization of EU freedom of movement: Political parties, opportunities, and policy framing in Germany and the UK. Comparative European Politics, 17(5), 631–650. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-018-0118-1

- Roos, C., & Westerveen, L. (2020). The conditionality of EU freedom of movement: Normative change in the discourse of EU institutions. Journal of European Social Policy, 30(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928719855299

- Ruhs, M. (2015). Is unrestricted immigration compatible with inclusive welfare states? The (Un)sustainability of EU exceptionalism. University of Oxford, Centre on Migration Policy and Society: Working Paper No. 125.

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2018). Brexit: Differentiated disintegration in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(8), 1154–1173. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1467954

- Schmidt, S. K., Blauberger, M., & Martinsen, D. S. (2018). Free movement and equal treatment in an unequal union. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(10), 1391–1402. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1488887

- Seubert, S. (2020). Shifting boundaries of membership: The politicisation of free movement as a challenge for EU citizenship. European Law Journal, 26(1–2), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12346

- Somerville, W. (2007). Immigration under new labour. Policy Press.

- Toshkov, D., & Kortenska, E. (2015). Does immigration undermine public support for integration in the European Union? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(4), 910–925. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12230

- Vasilopoulou, S., & Talving, L. (2019). Opportunity or threat? Public attitudes towards EU freedom of movement. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(6), 805–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1497075