ABSTRACT

How to reform the EU in times of fundamental conflict over the future of European integration? Although Europe’s future is fiercely debated, we still know little about what kind of EU citizens want and how their reform preferences relate to the emerging transnational cleavage. We argue that there are two kinds of reform trajectories. First, any changes that touch upon the vertical and horizontal balance of power should be highly contested, as people’s EU reform preferences depend on their position in the conflict between Eurosceptics and Europhiles. Second, reforms that do not activate this fundamental conflict, such as reshaping the EU’s input, output, and throughput legitimacy dimensions, should be favored by citizens across the board. Analyzing original data from conjoint survey experiments with 12,000 respondents in six EU member states largely corroborates our arguments. These findings carry important implications for the political debate about reforming the EU.

1. Introduction

Since the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty, the European Union (EU) has faced a number of internal and external shocks that have seriously challenged its political legitimacy: the global financial crisis, the Eurozone crisis, the refugee crisis, Brexit, and the Coronavirus pandemic. EU institutions repeatedly failed to deliver effective and broadly-accepted policy responses, which sparked rises in public Euroscepticism exploited by Eurosceptic challenger parties. In consequence, the EU’s ‘polycrisis’ (Zeitlin et al., Citation2019) has led to an increased politicization of European integration (Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2019) and reinforced a ‘transnational cleavage’ between pro-European and Eurosceptic parts of society (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018). This ‘political conflict over Europe’ (Schäfer et al., Citation2021) has become intertwined with sociodemographic divides (Ford & Jennings, Citation2020) and an emerging center-periphery cleavage in EU politics (Treib, Citation2021). As a result, the EU is confronted with the question of how to reform European governance in a way that tackles the EU's ‘crisis of legitimacy’ (Schmidt, Citation2020) without further deepening the ‘transnational-national divide’ (Jackson & Jolly, Citation2021).

In light of this difficult challenge, we aim to understand what kind of reforms would be supported by EU citizens on both sides of the transnational cleavage and which reform avenues would be highly contested. Therefore, we investigate how key EU reform dimensions are related to people’s previous dispositions towards European integration.

We argue that there are two kinds of reform avenues that could be followed. First, there are reforms that tap into the key conflict between Eurosceptics and Europhiles. This conflict should be activated by reforms that touch upon the balance of power between the national and the European level as well as upon the relative benefits of European integration between EU member states – the two main bones of contention between Eurosceptics and Europhiles. Preferences in these ‘contested’ areas – e.g., regarding the questions of how much political authority is delegated and pooled at the transnational level or how benefits from integration are distributed among member states – should depend on people’s previously-held EU attitudes. We hypothesize that Eurosceptic citizens should prefer a highly differentiated Union with strong intergovernmental elements and large relative benefits for their own country, whereas Europhiles should demand a less differentiated EU with a supranational character that works for all countries similarly well.

Second, there are reforms that do not touch upon such fundamentally contested dimensions. This is true for reforms that relate to institutional legitimacy dimensions that are considered to be classical sources of public support: input, output, and throughput legitimacy (Scharpf, Citation1999; Schmidt, Citation2013), such as providing more participation opportunities for citizens (input), greater transparency of decision-making processes (throughput), and an enhanced effectiveness of EU policies (output). As these reforms do not affect the vertical power relations within the EU or the zero-sum distributive conflict between member states, preferences regarding these uncontested EU reform dimensions should be shared by citizens across the board. Therefore, we argue that people support reforms in these areas independently from their stance regarding the political conflict over Europe.

We empirically test our arguments by conducting an online survey in six different EU member states with 2,000 respondents in each country (Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Spain). Since traditional survey techniques used in EU attitudes research are often ill-equipped for capturing multi-dimensional attitudinal complexity and avoiding endogeneity, we use conjoint survey experiments (Hainmueller et al., Citation2014). In doing so, we contribute to the emerging literature on EU attitudes using experimental survey methods and conjoint analyses (see, e.g., Franchino & Segatti, Citation2019; Schneider, Citation2019; Nicoli et al., Citation2020). The insights gained by our analysis bear important implications for scholars of European integration and for policy-makers seeking to reform the EU, as they provide a more fine-grained understanding of the diverging effects that different types of reforms could exert on the EU’s public legitimacy. Importantly, they suggest that reforms which modify the existing power distribution between the supranational and the national level or the relative cost-benefit distribution between member states would be highly contested. In contrast, relatively broad reform coalitions among citizens should be achievable for reforms that increase the EU's input, output, and throughput legitimacy.

2. EU reform attitudes and the conflict over Europe

Despite a large corpus of research on attitudes towards the EU and European integration more generally (Dellmuth & Schlipphak, Citation2020), we still know little about what kind of EU citizens actually want and how future EU reform trajectories could collide with the societal conflict between pro-Europeans and Eurosceptics. This gap is surprising because the rise of Euroscepticism in the post-Maastricht period is often interpreted as a consequence of the EU’s rapid institutional development, the steady pooling of political authority, and the geographical enlargement (Eichenberg & Dalton, Citation2007; Van Elsas & Van Der Brug, Citation2015; Treib, Citation2021). During the last thirty years, European integration and the legitimacy of the Union became increasingly contested in the public domain. Classical forms of legitimization, especially the production of beneficial policy outcomes, were suddenly seen as insufficient for the newly acquired, extensive policy-making competencies of the EU.

The conventional wisdom in this research area is that EU attitudes are multi-dimensional (Weßels, Citation2007; Boomgaarden et al., Citation2011; De Vreese et al., Citation2019) and even potentially ambivalent (De Vries, Citation2013; Stoeckel, Citation2013; Van Ingelgom, Citation2014). Such multi-dimensional ambivalence is mirrored in studies on people's preferences towards EU future scenarios (Goldberg et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b), revealing that ‘citizens have a rather nuanced outlook on the EU, disliking specific aspects of integration while supporting others’ (Goldberg et al., Citation2021b, p. 17). Goldberg et al. (Citation2021a, Citation2021b) show that citizens possess heterogeneous attitudes towards a range of future EU scenarios. However, their future scenarios can be broadly situated on a ‘more vs. less EU integration’ continuum, which does not reflect the various reform avenues that the EU could take in the future.Footnote1 Moreover, previous research has shown that the debate about the EU's future should not be ‘reduced to a crude binary choice between ‘more’ or ‘less’ Europe’ (Raines et al., Citation2017, p. 40) and that studying preferences towards European governance needs to consider the EU’s institutional complexity and different reform trajectories.

Two other empirical studies have aimed to tap into this complexity by using conjoint survey experiments to study people’s multidimensional EU attitudes. First, De Vries and Hoffmann (Citation2015) show that citizens prefer an EU that focuses on peace and security (functional dimension), permits the use of referenda (institutional dimension), and has a size of 28 members (communal dimension). Second, Hahm et al. (Citation2020) concentrate on the policy-making process and find that people reject the Commission's exclusive right of legislative initiative, support the existing bicameral legislative structure, and prefer majority voting over unanimity. Taken together, people seem to have both a tendency towards the institutional status quo (e.g., with regards to the EU’s size or the bicameral system) and a preference for more democratic decision-making (e.g., introduction of referenda, majority voting in the Council). However, these previous studies do not account for the degree of authority pooling and people’s previous dispositions towards EU integration.

Hence, our analysis goes beyond the state of the art by specifically focusing on the interaction between these two factors. We explicitly integrate individual stances on the transnational cleavage into the equation and argue how they relate to people’s future EU preferences. Even more importantly, we then weigh ‘contested’ reform dimensions, which touch upon the vertical and horizontal balance of powers in the EU and should hence interact with individual positions on the transnational cleavage, against ‘uncontested’ reform dimensions, including more traditional sources of public support for political institutions: the degree of an institution’s input, output, and throughput legitimacy.

2.1. Contested dimensions of EU reform attitudes

The rift between Eurosceptics and Europhiles forms part of a wider societal cleavage between liberal, cosmopolitan supporters of globalization and open borders against authoritarian, communitarian defenders of national autonomy (Kriesi et al., Citation2006; Zürn & De Wilde, Citation2016; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018). This value-based ‘transnational cleavage’ (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018) emerged during recent decades as a consequence of various sociodemographic developments, such as educational expansion, mass migration, the aging of societies, and the urban-rural divide (Ford & Jennings, Citation2020). In Europe, the ‘transnational-national divide’ (Jackson & Jolly, Citation2021) has led to a significant ‘political conflict over Europe’ (Schäfer et al., Citation2021), in which the issue of European integration has become increasingly contested. Furthermore, the conflict is sometimes seen as a result of the continuing centralization of decision-making powers at the European level and the resistance against this new form of center-formation (Treib, Citation2021).

We argue that the increasing importance of the transnational cleavage plays a crucial role in shaping people’s EU reform attitudes. The focal point in the conflict between the pro-EU and the Eurosceptic camps are essential questions of national sovereignty and the relative benefits for one’s own nation. Therefore, reforms that touch upon these issues should be highly contested between Eurosceptics and Europhiles. Eurosceptics should reject reforms that diminish national sovereignty, and they should be critical of reforms that are expected to yield more benefits for other countries than their own. Europhiles, in contrast, should be in favor of reforms that strengthen EU authority and diminish member state autonomy, and they should support reforms that provide comparable benefits for all EU member states.

As we will spell out in more detail below, we expect three major dimensions of EU reform to be highly contested and thereby leading to fundamentally different reform preferences between Europhiles and Eurosceptics: differentiated integration, intergovernmental vs. supranational decision-making, and the distribution of benefits between member states. Eurosceptic citizens should, first, favor a more differentiated European integration in which EU legislation does not apply to all EU member states. Second, they should also prefer a lesser degree of authority pooling and, therefore, more intergovernmental decision-making processes compared to supranational modes. And, third, their reform attitudes should depend on the expected benefits for their own country compared to other EU member states. In contrast, Europhile citizens should find the EU more acceptable when there is less differentiation, more supranational decision-making (i.e., more authority pooling) and an equal distribution of benefits among all EU member states.

While we can think of further EU reforms that could lead to significant contestation between Europhiles and Eurosceptics, like the accession of additional member states or the types of sanctions to be applied to member states that fail to comply with EU law, we believe that the three dimensions mentioned here capture the most prominent and most general contested reforms in the current debate about the future of the European Union.

2.1.1. Differentiated integration

The first contested reform dimension relates to differentiated integration (DI). Differentiation has become an essential element of European integration since the 1990s, often attributed to the increased diversity in an enlarging and deepening EU (Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2020). It implies that individual member states enjoy opt-outs that free them from the obligations of membership – both regarding EU treaties and in secondary EU law (Duttle et al., Citation2017). In light of the fragmented Euro and Schengen areas, DI today represents ‘an increasingly normal feature of EU policy-making’ (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2016, p. 42). It accommodates the diversity of national structures and policy legacies, and it has the potential to overcome deadlocks in EU-level negotiations (Bellamy & Kröger, Citation2017).

DI touches upon the distribution of powers between central EU authority and national autonomy. As a consequence, we expect the question of striving for more or less differentiated integration to be contested between Eurosceptics and Europhiles. This expectation is supported by previous research. Although research on attitudes towards DI is still sparse, it has recently gained traction. While Leuffen et al. (Citation2020) demonstrate that support for DI can be explained by liberal values, De Blok and De Vries (Citation2020) find that Eurosceptic citizens are more supportive of national opt-outs than Europhiles. Schraff and Schimmelfennig (Citation2020) show that Eurosceptic voters in a 2015 Danish opt-out referendum – which they won – experienced an increase in the belief that their individual voice counts in EU politics. This suggests that stronger differentiation is favored among people who are critical towards the EU.

Building on these findings, we argue that the degree of differentiated integration should affect people’s EU reform preferences but that this effect is moderated by their previously held EU attitudes. While Eurosceptic citizens should prefer an EU with the possibility of national opt-outs, Europhile citizens should prefer an EU with legally binding legislation for all member states (hypothesis 1a).

2.1.2. Intergovernmentalism vs. supranationalism

The second contested dimension of EU reform relates to the pooling of decision-making powers and the balance of intergovernmental and supranational elements. Each EU institution operates on a dimension ranging from strictly intergovernmental to fully supranational. In the case of the Council, for example, the traditional intergovernmental mode of decision-making (unanimity rule) has been progressively replaced by a more supranational mode (qualified majority voting) in many policy areas. National rights to veto any policy decision were thus transformed into varying degrees of veto power and bargaining power in the Council (Slapin, Citation2011). The question of unanimous or majoritarian decision-making in the Council directly touches upon questions of national sovereignty.Footnote2 Therefore, Eurosceptics should favor unanimity as it grants each member state government veto power whereas Europhiles should support majority voting since it facilitates joint EU decisions.

Building on these arguments, we assume that the intergovernmental-supranational antagonism matters for people’s EU reform attitudes, but that EU attitudes moderate the effect of the degree of national veto power in the Council. While Eurosceptic citizens should prefer intergovernmental decision-making (i.e., unanimity), Europhile citizens should prefer a supranational mode of operation (i.e., simple majority voting) (hypothesis 1b).

2.1.3 Relative national benefits

Not all EU member states benefit in the same way from EU policies. For example, countries with large agriculture sectors benefit more from the EU’s common agricultural policy. Having favorable preferences towards the EU because of the perceived benefits for one’s own country compared to other countries is in line with utilitarian approaches (Anderson & Kaltenthaler, Citation1996) and benchmark approaches of explaining EU attitudes (De De Vries, Citation2018). Perceptions of relative utility should be particularly important when people feel that they become disadvantaged, as people are loss-averse (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979) and in fear of relative deprivation (Crosby, Citation1976). Reforms that shift the relative distribution of integration benefits between member states, such as in the cases of fiscal solidarity measures, should therefore be highly contested.

However, the degree to which people tend towards ‘national self-interest’ should depend on their predispositions towards Europe. From studies on European solidarity, we know that a strong European identity yields a higher acceptance of transnational redistribution (Kuhn et al., Citation2018; Verhaegen, Citation2018; Nicoli et al., Citation2020). This might be due to the fact that people make consequential distinctions between members of their ‘in-group’ and those of ‘out-groups’ (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). Eurosceptic citizens might be more inclined to see people from other EU countries as out-group members and perceive a conflict about limited resources, whereas Europhiles could perceive fellow Europeans as members of their in-group, worthy of the same benefits that they receive themselves. Moreover, theories of ‘distributive justice’ (Adams, Citation1965) suggest that pro-Europeans should be averse to becoming unfairly advantaged over citizens from other member states.

Based on these arguments, we assume that relative national benefits matter for people’s EU reform attitudes, but that their EU dispositions condition the effects of relative benefits. While Eurosceptic citizens should prefer greater benefits for their own country, Europhile citizens should prefer a fair distribution between all member states (hypothesis 1c).

2.2. Uncontested dimensions of EU reform attitudes

There are EU reform dimensions that are less contested between the two sides of the transnational-national divide. In particular, this should be the case for changes regarding the ‘input and output legitimacy’ (Scharpf, Citation1999) of the Union. While the input dimension refers to an institution’s capability to efficiently incorporate popular demands into the policy-making process, the output dimension relates to the effectiveness and utility of policies for the majority of the people. In other words, while input legitimacy means that democratic systems can be considered legitimate when citizens have the chance to influence policy-making via equal participation mechanisms, output legitimacy is derived from positive outcomes of political decisions, even in cases where decisions emanate from procedures that do not conform to democratic ideals. More recently, Schmidt added the notion of throughput to the equation as a form of legitimacy relating purely to procedural mechanisms (Schmidt, Citation2013; Schmidt & Wood, Citation2019). Referring to the ‘black box’ between inputs and outputs, throughput legitimacy is ‘concerned with the quality of governance processes, as judged by the accountability of the policy-makers and the transparency, inclusiveness and openness of governance processes’ (Schmidt & Wood, Citation2019, p. 728).

We argue that the input, output, and throughput dimensions of the European Union are not connected to the core conflict between Eurosceptics and Europhiles – that is, questions of national autonomy and the distribution of benefits between countries. We assume that citizens in general are more supportive of an institution that provides more inclusive decision-making as well as transparent and effective policy-making compared to an institution that scores lower on these legitimacy dimensions, irrespective of the level of governance. Therefore, Eurosceptics and Europhiles alike should share a preference for modes of decision-making that are as accessible, inclusive, and effective as possible. Some may argue that Eurosceptics could prefer a less democratic, less transparent and less effective EU due to their own hostility towards the Union. However, we believe that people’s general preference for democratic decision-making on issues that affect their lives should override skepticism towards the EU.

2.2.1. Citizen participation (input)

Although direct elections to the European Parliament (EP) were already established in 1979 as first participatory instrument at the European level, citizen participation is still poorly developed in the EU. Not only did the EP remain a rather powerless institution until the introduction of the co-decision procedure, but EP elections are up to this day considered to be ‘second-order elections’ (Reif & Schmitt, Citation1980). To strengthen the EU’s input legitimacy beyond the representative model of democracy, we can turn to theories of deliberative or direct democracy.Footnote3 As a current example, the Conference on the Future of Europe represents an increasingly popular form of consultative, deliberative democracy and a democratic innovation at the European level, in which the EU puts great hope regarding its legitimizing function (Cengiz, Citation2018).

An even more direct opportunity for citizens to influence European integration could be through referendums. In particular, ‘EU policy referendums’ have been ‘the fastest growing category of EU referendums in recent years’ (Mendez & Mendez, Citation2017, p. 58), with votes on different policy issues, such as monetary policy or EU enlargement. Although there are currently no provisions for EU-wide referendums, many scholars argue that this might be an option for the future development of the Union (Habermas, Citation2001), especially since such direct democratic instruments have shown to increase empirical (input) legitimacy of political systems (Gherghina, Citation2016).

Taken together, we expect that more opportunities for participation should positively affect citizens’ EU reform attitudes. Citizens should prefer to have deliberative and direct democratic instruments at their disposal to influence EU policy-making, rather than being restricted to the existing electoral channel (hypothesis 2a).

2.2.2. Transparency (throughput)

A second legitimizing factor for a political system is the transparency of policy-making processes, which enhances the accountability of political decisions to the responsible actors.Footnote4 In the case of the EU, transparency refers to informative actions of EU institutions, i.e., when they inform the public about internal processes. These practices seem particularly important for the Council of the EU (Novak & Hillebrandt, Citation2020) and when it comes to the access of lobbying and interest groups (Bunea, Citation2018). Hence, providing greater transparency throughout the legislative process to increase public trust is a popular legitimation strategy of international institutions (Gronau & Schmidtke, Citation2016). Empirical studies underline that there are positive effects of transparency on citizen satisfaction (Cucciniello et al., Citation2017) and that people prefer transparency over closed-door negotiations in international cooperation (Bernauer et al., Citation2019).

Based on these findings, we expect that enhancing the transparency of inter-institutional decision-making processes should positively affect citizens’ EU reform attitudes. Citizens should prefer that information about these processes is publicly available from an early stage on (hypothesis 2b).

2.2.3. Effectiveness (output)

As mentioned, output legitimacy is ‘derived from the capacity of a government or institution to solve collective problems and to meet the expectations of the governed citizens’ (Mayntz, Citation2010, p. 10). It can, thus, be said that the main aspect of the output dimension is effective problem-solving, especially in the case of European governance (Höreth, Citation1999; Lindgren & Persson, Citation2010). As long as the EU (and its predecessors) delivered effective policies, the integration process enjoyed the passive support of citizens – even though the transfer of competencies to the supranational level was insufficiently accompanied by institutional possibilities to affect policy-making. However, output failures such as the Eurozone crisis reveal that the EU’s legitimacy is nowadays quickly disputed among citizens when the Union fails to fulfill their performance expectations (Serrichio et al., Citation2013; Braun & Tausendpfund, Citation2014).

Based on these arguments, we hypothesize that the EU’s institutional performance should affect people’s reform attitudes. Citizens should prefer more effective EU policies (hypothesis 2c).

2.3. Summary of theoretical expectations

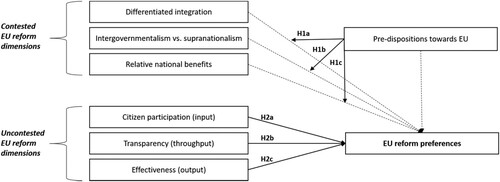

illustrates our theoretical model. We assume that the arrows in the figure represent causal mechanisms in which pre-existing dispositions towards the EU guide people’s cognitive responses to EU reform options and institutional designs. We hypothesize that three contested dimensions of EU reform (differentiated integration, intergovernmentalism vs. supranationalism, relative national benefits) affect people’s attitudes, but that their reform preferences are conditioned by previous dispositions towards the EU (hypotheses 1a-c). In contrast, changes on the three uncontested reform dimensions (citizen participation, transparency, effectiveness) are supported by most people in Europe – independent from their previous dispositions towards the EU (hypotheses 2a-c). We acknowledge that there is a certain conceptual overlap (e.g., between citizens participation and the supranational dimension of policy-making). However, the dimensions are still theoretically distinct and the overlap is only marginal, which is why we discuss them separately in the following.

3. Empirical analysis

In order to test the theoretical hypotheses, we conducted an online survey in the six EU member states Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Spain. The case selection reflects diversity in geography, population size, economic conditions, duration of EU membership, and level of democracy. In each country, 2,000 respondents were interviewed, yielding an overall sample size of 12,000. In order to improve the representativity of the sample and the generalizability of the results, we applied quotas for gender, age, and educational attainment. The quota sampling was conducted within an online access panel database provided by KANTAR.Footnote5 The interviews were conducted online between 11 September and 23 October 2020.

In the survey, we implemented a pre-registered conjoint survey experiment.Footnote6 Conjoint experiments have become increasingly popular in political science, especially after the introduction by Hainmueller and colleagues (Hainmueller et al., Citation2014). They address the restrictions of traditional survey tools used in cross-section observational studies, especially the difficulty to identify complex cause-effect relationships and endogeneity problems. Conjoint experiments allow researchers to identify causal effects exerted by various treatment components in surveys, which is particularly useful for our purposes given the EU’s complex institutional design and the multidimensionality of people’s attitudes. In a comprehensive literature review on public support for European integration, Hobolt and De Vries (Citation2016) thus demand that future research should ‘build on recent developments in this field and make greater use of conjoint analysis’ (Hobolt & De Vries, Citation2016, p. 426).

3.1. The experimental setting

Survey participants were confronted with eight hypothetical EU decisions in four pairs and asked to choose one decision profile over the other. Each profile consisted of six attributes, where each attribute varied randomly over three different levels (full randomization). Potentially, thus, the 18 single treatments (6 attributes*3 levels) add up to 729 different profiles, i.e., combinations of attribute levels. Importantly, the size of this profile universe is much smaller than the overall number of profiles that were evaluated, namely 96,000 profiles (12,000 respondents*8 profiles), which guarantees that all attribute level combinations were evaluated in numbers high enough for robust statistical estimations (full factorial design).

We undertook several steps to facilitate people’s judgement and make the evaluation tasks as graphic as possible. First, we engaged respondents with the hypothetical setting by asking them to choose a policy area in which they prefer most that the EU takes political decisions. Second, participants were told that the EU decisions ‘would have a substantial impact on people’s lives’, which was done in order to illustrate the significance of the task. Third, to guarantee respondents’ understanding of all institutional attributes, we presented short descriptions beforehand and during the evaluation tasks (see ). Our choice for the evaluation of concrete political decisions instead of abstract institutional designs is not only in line with our theoretical conception of EU legitimacy but also justified by our aim to increase the external validity of people’s decisions. Hence, we described each attribute in a way that is easily accessible and relates to a concrete EU decision.Footnote7

Table 1. Attributes, descriptions, and levels in the conjoint experiment.

3.2. Operationalization

To measure our dependent variable, people’s willingness to accept EU decisions, we asked respondents to perform a discrete choice task. People were requested to indicate which of the two randomly sampled EU policy decisions they would prefer over the other. This implies that for every single profile, we received a binary choice variable indicating whether the profile was chosen or not (0 = not chosen, 1 = chosen).Footnote8

The independent variables are operationalized via six experimental treatments (i.e., the profile attributes), each comprising three levels. They represent the two sets of legitimacy dimensions corresponding to our theoretical hypotheses (see ). First, to measure differentiated integration (H1a), we specified the degree to which member states are bound to comply with EU legislation. Second, the intergovernmental-supranational (H1b) dimension is operationalized via the extent to which member states possess veto power or can be outvoted. Third, the relative national benefits (H1c) dimension contains options that compare benefits for one’s own country to those of others. Fourth, the levels of citizen participation (H2a) contain elements of electoral, deliberative, and direct democracy. Fifth, transparency (H2b) is operationalized with degrees to which information about the decision-making process is publicly available. Sixth, the levels of effectiveness (H2c) consist in varying degrees to which the EU decisions would solve a policy problem.

To operationalize respondents’ previously held general EU attitudes, we included – prior to the conjoint experiment – a classical item often used to measure people’s ‘EU regime support’ (Hobolt & De Vries, Citation2016).Footnote9 It asks whether respondents think that their country’s EU membership is ‘a good thing, a bad thing, or neither good nor bad’. As a result, the variable obtained is categorial and allows us to distinguish between the camps of Eurosceptics (‘good thing’) and Europhiles (‘bad thing’).Footnote10

3.3. Results

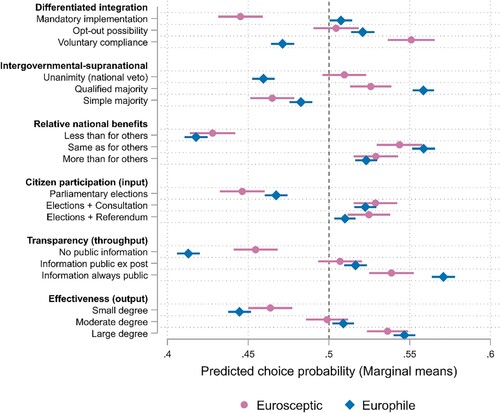

To assess the impact of the attributes and their respective levels, we estimated logistic regression models on the binary choice variable and conduct a sub-group analysis in which we compare the attribute effects for Eurosceptic and Europhile respondents with the help of marginal means following Leeper et al. (Citation2020). demonstrates the attribute effects expressed as marginal means, i.e., the predicted probability of choosing one profile over the other. The probabilities are based on separate logistic regression models for Eurosceptic and Europhile respondents, implying that we cannot make inferences about statistically significant differences between the two groups. Values below 0.5 mean that profiles including this attribute level are chosen significantly less often compared to the other profile displayed, whereas values above 0.5 imply that profiles with this attribute level are chosen relatively more often.

Figure 2. Effects of contested and uncontested legitimacy dimensions on the acceptance of EU decisions conditional on citizens’ general EU attitudes (predictive means).

Note: Displayed are marginal mean outcomes from a discrete choice experiment (see also Leeper et al., Citation2020), estimated separately for different types of respondents by their EU attitudes (Eurosceptic versus Europhile respondents); error bars reflect 95% confidence intervals, clustered by respondent (i.e., respondent-clustered standard errors) with each respondent completing four binary choice decision tasks (see also Appendix C); nEurosceptic=13,472 profiles (1,684 respondents), nEurophile=51,248 profiles (6,406 respondents).

Looking at the three contested EU legitimacy dimensions, the group-specific effects appear very distinct. First, regarding differentiated integration, Eurosceptics are very reluctant to the mandatory implementation of EU laws and prefer EU legislation that is based on voluntary compliance. The latter is the least acceptable option for Europhiles who display the strongest preference for opt-out possibilities (closely followed by mandatory implementation). Taken together, EU decisions with opt-outs are the only option that does not lead to a statistically significant aversion to choose the respective profile.

Second, the intergovernmental-supranational dimension yields diverging effects among the two groups. For Eurosceptics, simple majority voting is clearly the least preferred option, whereas Europhiles are most averse to unanimity. However, there seems to be common ground when it comes to qualified majority voting, which is the most preferred option for both pro-EU and anti-EU citizens (albeit on equal terms with unanimity for the latter group). This preference for the status quo compared to the other options across both sides on the transnational-national divide seems remarkable.

Third, the preference structure regarding relative national benefits is rather similar across the two groups. Yet, whereas Europhiles strongly prefer equal distribution for all member states, this option is on equal footing with the national self-interest option for the Eurosceptic camp. In sum, it can be concluded that both camps find common ground in preferring a European Union that produces similar benefits for all member states.

Taken together, hypotheses 1a-c are partially confirmed by the empirical data. It has been shown that people’s preferences for the EU reforms are moderated by their general EU attitudes when it comes to contested EU legitimacy dimensions. This is most strongly the case for the degree of differentiated integration, where the preference structure varies drastically between Europhiles and Eurosceptics. But it is also visible for the intergovernmental-supranational dimension, where the preference structure is notably different for the two camps. Although it is much lesser the case regarding the expected relative national benefits, here too we find a small moderation effect: while Europhiles have a strong preference for the ‘same’ benefits across countries, Eurosceptics have no clear first choice. However, it is also true that no single hypothesis is fully confirmed, as all three dimensions do not yield a diametrically opposed preference structure. A consequence from this finding is that Europhiles and Eurosceptics could agree on a European Union with the possibility of national opt-outs, qualified majority voting and similar benefits for all member states.

Across the three uncontested EU legitimacy dimensions, both camps display a very similar preference structure. First, more opportunities for citizen participation – whether they have a consultative or direct democratic nature – are clearly more preferred than the elections-only option. However, Eurosceptic citizens do not distinguish between the two other levels, whereas pro-EU respondents slightly prefer consultations over referendums. Second, the transparency effects are comparable for the two groups but remarkably more pronounced for Europhiles, indicating that transparency is a particularly important issue for this group. Third, the effects of effectiveness are not substantially different between the two camps, even though they are slightly more pronounced for Europhile citizens.

Again, our hypotheses 2a-c are largely confirmed. Independent from their general EU attitudes, citizens react positively to increases in input, throughput and output legitimacy. The differences between the preference structures on both sides of the transnational cleavage seem neglectable when it comes to future EU reform trajectories. Hence, reforming the EU regarding its input, throughout and output dimensions should lead to stronger legitimacy beliefs across large parts of the EU population.

Our empirical findings are supported by a series of additional model specifications and robustness checks. Besides the full regression results and further visualizations (Appendix C), the online appendix contains country-specific regression results (Appendix D), models with the profile rating as an alternative dependent variable (Appendix E), and regression models with a different measurement of general EU attitudes (Appendix F). It shows, for example, that the results are remarkably similar across the six EU member states (see Table D-1 and Figure D-2). Moreover, they also hold when estimating hierarchical linear regression on the interval-level rating variable (instead of the dichotomous choice variable), with which respondents were asked to evaluate every profile (see Table E-1, Figures E-2 and E-3). Lastly, when using respondents’ ‘EU policy support’, i.e., their support for the European integration process (Hobolt & De Vries, Citation2016) as a quasi-metric measure for their EU predispositions, we obtain remarkably similar results (see Table F-2 and Figure F-3).

4. Discussion and conclusion

In this article, we investigated what kind of EU citizens want and how their EU reform attitudes interact with the general political conflict over European integration. We argued that people’s position on the transnational cleavage shapes their reform preferences, but only with regard to the dimensions that touch upon questions at the heart of the conflict over Europe. These crucial dimensions primarily concern the distribution of power between the member states and the supranational level or the horizontal distribution of costs and benefits between member states. Hence, reforms that change the vertical distribution of power or the horizontal distribution of costs and benefits should be contested between Eurosceptics and Europhiles. At the same time, there are also relatively uncontested reform trajectories, which leave the vertical distribution of power or horizontal distributive conflicts untouched. These include reforms that increase the input, output, and throughput legitimacy of EU governance.

The empirical results of our conjoint survey experiments in six diverse EU member states largely corroborate our expectations. On the one hand, Eurosceptics and Europhiles show widely-diverging preferences regarding the extent to which EU legislation should apply to all member states and whether the EU should move into a more intergovernmental or supranational direction. On the other hand, both Eurosceptics and Europhiles support more citizen participation, more transparency, and EU decisions that are able to solve the underlying policy problems.

However, individual results also ran counter to our theoretical expectations. First, even Europhile citizens prefer national opt-outs over the mandatory implementation of EU legislation. Second, people on both sides of the transnational cleavage show a preference for status quo options when it comes to the intergovernmental-supranational dimension, illustrated by qualified majority voting being the most preferred option across both groups. Third, Eurosceptic citizens do not show the degree of national chauvinism that we expected. Rather, they favor distributive equity. We assume that this finding may be explained by collectively-shared norms of distributive fairness (see, for example, Adams, Citation1965; Kahneman et al., Citation1986).

Our findings have important implications for both the literature on public opinion about EU reforms and for the political debate about how to improve the EU’s public legitimacy. There have been relatively few studies on citizens’ attitudes towards EU reforms (De De Vries & Hoffmann, Citation2015; Hahm et al., Citation2020; Goldberg et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b), and our analysis goes beyond the insights gained by these studies in at least three respects. First, we studied people’s reform preferences by letting respondents choose EU decisions that they are willing to accept and, thus, connected the analysis of EU reform attitudes to people’s legitimacy beliefs. Second, we explicitly demonstrated how people’s reform preferences are shaped by the fundamental political conflict between Eurosceptics and Europhiles. And, third, we showed that the conflict over Europe affects only some types of reforms, which are at the heart of the pro-/anti-EU cleavage, whereas others remain rather unaffected by this conflict.

With a view to political debates about reforming the EU, as they have been conducted in forums such as the Conference on the Future of Europe, our findings suggest that different types of reforms are likely to elicit very different forms of political conflict among EU citizens. Hence, policy-makers should be aware that changes to the current balance of powers between the supranational and the national levels of governance in the EU is likely to founder on fundamental disagreement between Eurosceptics and Europhiles. An even deeper rift between the two sides of the transnational cleavage might be a result of such reforms. The institutional status quo seems to be the best that can be achieved without sparking fierce conflict between proponents and opponents of deeper European integration.

Reforms that do not shift the vertical distribution of power, however, should be much more acceptable to a broad range of citizens. Increasing citizen participation, rendering EU decision-making more transparent, and striving for policy solutions that actually ‘deliver’ – all of these reforms are likely to find widespread support from both Eurosceptics and Europhiles, which might eventually contribute to a depolarization of the conflict over Europe. Moreover, we conclude that reform proposals that are perceived as having similar benefits for all member states should be supported by large parts of the EU population. Yet, precaution is recommended: if national political elites were to convince their citizens that the EU provides more benefits for other countries than for their own, there is great potential to discredit European integration and delegitimize the EU. Policy-makers, therefore, need to deliver fair policies and reforms that benefit all member states alike, and they should be more effective in communicating common advantages. If they succeed, there is a high likelihood that citizens will regard EU decisions as legitimate, eventually resulting in a higher public legitimacy – even, and perhaps in particular, in times of increasing conflicts over Europe.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1,005.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Isabel Hoffmann, Luisa Kunze, Elena Otto-Erley, Maike Pollmann and Simon Vöhringer for competent research assistance at various stages of putting together the dataset and the manuscript. Moreover, we thank the participants of the workshop on ‘Institutional Reform and Public Legitimacy’ which we hosted in Münster in January 2020 in order to discuss the design of the conjoint experiments on which this article is based. Lastly, we are also grateful to the three anonymous referees and the editors for their insightful comments, which have helped to improve the manuscript.

Data availability statement

Supporting data and materials for this article can be accessed on the Taylor & Francis website, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2102670. The data for this article can be accessed at the Austrian Social Science Data Archive, https://doi.org/10.11587/D3PZEA (data access requires registration).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Constantin Schäfer

Constantin Schäfer works as consultant and project manager for citizen participation at ifok GmbH, Germany, and he is an affiliated researcher at KU Leuven, Belgium.

Oliver Treib

Oliver Treib is professor of comparative policy analysis and research methods at the University of Münster, Germany.

Bernd Schlipphak

Bernd Schlipphak is professor of research methods at the University of Münster, Germany.

Notes

1 See, for example, the European Commission’s “White Paper on the Future of Europe” (2017) for a range of different future scenarios: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/white_paper_on_the_future_of_europe_en.pdf.

2 One could also argue that majority rules stand in conflict with the “consensus model” of democracy that exists in the EU (Lijphart Citation2012: 40-45; see also Treib, Citation2021). A majoritarian approach to decision-making might therefore create a lack of legitimacy in the eyes of citizens (Heisenberg Citation2005: 82), especially when they are already skeptical toward the EU.

3 One could also hypothesize that strengthening the representative model of EU democracy (e.g., with the institutionalization of the Spitzenkandidaten process or with reforms of European electoral laws) could improve input legitimacy. However, since we believe that citizens would have had a hard time understanding electoral reforms, we restricted ourselves to key features of different democracy models.

4 Naturally, there are more dimensions of throughput legitimacy than transparency (e.g., the inclusion of scientific expertise in the policy-making process). However, we assume that transparency is the most straightforward and easy-to-understand factor for ordinary citizens.

5 See Appendix G for the survey demographics and a comparison with population data from Eurostat.

6 Note that this paper diverges from the pre-registration plan in two aspects (PAP available under: https://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=pc4gk6): First, the distinction between contested and uncontested reform dimensions is less explicit in the original PAP. Second, the interaction effects that depend upon EU attitudes are phrased in a more exploratory manner. An analysis that closely follows the original PAP, seeking to establish the relative strength of the effects of the analyzed dimensions, is under review at another outlet. However, the PAP already states that the moderating effect of attitudes towards European integration will be tested and will, therefore, be addressed in a second, different paper.

7 Appendix A provides further information on the conjoint experiment and illustrates an example from the German language version (see Figure A-1). In order to secure the highest possible data quality, we intentionally oversampled and then excluded 1,586 respondents on the basis of different quality criteria (e.g., IP and identity verification, interview length and number of missing values, honesty and other “survey health” checks). For example, we checked the time that it took survey respondents to click through the conjoint module, and we excluded so-called “speedsters” (i.e. respondents who clicked through the experiment faster than 40% of the median time). Moreover, an initial pre-test in all six countries (with the possibility to provide feedback on the wording of the questions) as well as a double-check with national language experts was conducted prior to the fieldwork, in order to achieve the highest possible comprehensibility of the questions and quality of the translations.

8 We additionally asked participants how much they would be “in favor of or opposed to each EU policy decision” on an 11-point interval scale ranging from “totally opposed” (-5) to “totally in favor” (+5). We use the resulting rating variable for robustness checks (see Appendix E).

9 See Appendix F for an alternative measurement based on the concept of “EU policy support” (Hobolt & De Vries, Citation2016) revealing similar results.

10 The residual third group, which might be called EU-Ambivalents (“neither a good nor a bad thing”), is not used in the following analysis. But see Appendix B for the distribution of EU attitudes, demonstrating that we find a similar share of Eurosceptics as recent Eurobarometer data, but relatively less Europhiles and more EU-Ambivalents for the six countries surveyed (EB 94.2, EP 2020). The effects sizes for EU-Ambivalents are, as it might be expected, somewhat in the middle between Eurosceptics and Europhiles (displayed, for example, in Tables C-4, E-2, E-3). However, since our theoretical arguments focus on the conflict between the two opposing camps, since the results of EU-Ambivalents do not provide crucial additional insights, and since the empirical results (and visualizations) are clearer and more readable, we left this “middle group” out in the main text (but see online appendix).

References

- Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60108-2

- Anderson, C. J., & Kaltenthaler, K. C. (1996). The dynamics of public opinion toward European integration, 1973-93. European Journal of International Relations, 2(2), 175–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066196002002002

- Bellamy, R., & Kröger, S. (2017). A demoicratic justification of differentiated integration in a heterogeneous EU. Journal of European Integration, 39(5), 625–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2017.1332058

- Bernauer, T., Mohrenberg, S., & Koubi, V. (2019). Do citizens evaluate international cooperation based on information about procedural and outcome quality? The Review of International Organizations, 15(2), 505–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09354-0

- Boomgaarden, H. G., Schuck, A. R. T., Elenbaas, M., & De Vreese, C. H. (2011). Mapping EU attitudes: Conceptual and empirical dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU support. European Union Politics, 12(2), 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116510395411

- Braun, D., & Tausendpfund, M. (2014). The impact of the Euro crisis on citizens’ support for the European Union. Journal of European Integration, 36(3), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.885751

- Bunea, A. (2018). Legitimacy through targeted transparency? Regulatory effectiveness and sustainability of lobbying regulation in the European Union. European Journal of Political Research, 57(2), 378–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12231

- Cengiz, F. (2018). Bringing the citizen back into EU democracy: Against the input-output model and why deliberative democracy might be the answer. European Politics and Society, 19(5), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2018.1469236

- Crosby, F. (1976). A model of egoistical relative deprivation. Psychological Review, 83(2), 85–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.83.2.85

- Cucciniello, M., Grimmelikhuijsen, S., & Porumbescu, G. (2017). 25 years of transparency research: Evidence and future directions. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12685

- De Blok, L., & De Vries, C. E. (2020). A blessing and a curse? Examining public preferences for differentiated integration. Deliverable D3.2, InDivEU project (unpublished manuscript, 28/09/2020).

- Dellmuth, L. M., & Schlipphak, B. (2020). Legitimacy beliefs towards global governance institutions: A research agenda. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(6), 931–943. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1604788

- De Vreese, C. H., Azrout, R., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2019). One size fits all? Testing the dimensional structure of EU attitudes in 21 countries. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 31(2), 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edy003

- De Vries, C. E. (2013). Ambivalent Europeans? Public support for European integration in East and West. Government and Opposition, 48(3), 434–461. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2013.15

- De Vries, C. E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford University Press.

- De Vries, C. E., & Hoffmann, I. (2015). What do the people want? Opinions, moods and preferences of European Citizens. Europinions 1/2015, Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Duttle, T., Holzinger, K., Malang, T., Schäubli, T., Schimmelfennig, F., & Winzen, T. (2017). Opting out from European Union legislation: The differentiation of secondary law. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(3), 406–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1149206

- Eichenberg, R. C., & Dalton, R. J. (2007). Post-Maastricht blues: The transformation of citizen support for European integration, 1973-2004. Acta Politica, 42(2-3), 128–152. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500182

- Ford, R., & Jennings, W. (2020). The changing cleavage politics of Western Europe. Annual Review of Political Science, 23(1), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-052217-104957

- Franchino, F., & Segatti, P. (2019). Public opinion on the Eurozone fiscal union: Evidence from survey experiments in Italy. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(1), 126–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1400087

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2016). More integration, less federation: The European integration of core state powers. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1055782

- Gherghina, S. (2016). Direct democracy and subjective regime legitimacy in Europe. Democratization, 24(4), 613–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2016.1196355

- Goldberg, A. C., Van Elsas, E. J., & De Vreese, C. H. (2021a). Eurovisions: An exploration and explanation of public preferences for future EU scenarios. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59(2), 222–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13057

- Goldberg, A. C., Van Elsas, E. J., & De Vreese, C. H. (2021b). One union, different futures? Public preferences for the EU's future and their explanations in 10 EU countries. European Union Politics, 22(4), 721–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165211034150

- Gronau, J., & Schmidtke, H. (2016). The quest for legitimacy in world politics – international institutions’ legitimation strategies. Review of International Studies, 42(3), 535–557. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210515000492

- Habermas, J. (2001). Why Europe needs a constitution. New Left Review, 42(11).

- Hahm, H., Hilpert, D., & König, T. (2020). Institutional reform and public attitudes toward EU decision making. European Journal of Political Research, 59(3), 599–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12361

- Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt024

- Heisenberg, D. 2005. The institution of ‘Consensus’ in the European union: Formal versus informal decision-making in the council. European Journal of Political Research, 44 (1): 65–90.

- Hobolt, S. B., & De Vries, C. E. (2016). Public support for European integration. Annual Review of Political Science, 19(1), 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042214-044157

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Höreth, M. (1999). No way out for the beast? The unsolved legitimacy problem of European governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 6(2), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/135017699343702

- Hutter, S., & Kriesi, H. (2019). Politicizing Europe in times of crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 996–1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619801

- Jackson, D., & Jolly, S. (2021). A new divide? Assessing the transnational-nationalist dimension among political parties and the public across the EU. European Union Politics, 22(2), 316–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520988915

- Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1986). Fairness and the assumptions of economics. The Journal of Business, 59(S4), S285–300. https://doi.org/10.1086/296367

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2006). Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research, 45(6), 921–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00644.x

- Kuhn, T., Solaz, H., & Van Elsas, E. J. (2018). Practising what you preach: How cosmopolitanism promotes willingness to redistribute across the European union. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(12), 1759–1778. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1370005

- Leeper, T. J., Hobolt, S. B., & Tilley, J. (2020). Measuring subgroup preferences in conjoint experiments. Political Analysis, 28(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.30

- Leuffen, D., Schuessler, J., & Gómez Díaz, J. (2020). Public support for differentiated integration: Individual liberal values and concerns about member state discrimination. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(2), 218–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1829005

- Lijphart, A. (2012). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Lindgren, K., & Persson, T. (2010). Input and output legitimacy: Synergy or trade-off? Empirical evidence from an EU survey. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(4), 449–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501761003673591

- Mayntz, R. (2010). Legitimacy and Compliance in Transnational Governance. MPIfG Working Paper 10/5, https://www.mpifg.de/pu/workpap/wp10-5.pdf.

- Mendez, F., & Mendez, M. (2017). The promise and perils of direct democracy for the European Union. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 19, 48–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/cel.2017.7

- Nicoli, F., Kuhn, T., & Burgoon, B. (2020). Collective identities, European solidarity: Identification patterns and preferences for European social insurance. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(1), 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12977

- Novak, S., & Hillebrandt, M. (2020). Analysing the trade-off between transparency and efficiency in the Council of the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(1), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1578814

- Raines, T., Goodwin, M. & Cutts, D. (2017). The Future of Europe: Comparing Public and Elite Attitudes. Chatham House Research Paper, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2017-06-19-future-europe-attitudes-embargoed.pdf.

- Reif, K., & Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine second-order national elections – a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results. European Journal of Political Research, 8(1), 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x

- Schäfer, C., Popa, S. A., Braun, D., & Schmitt, H. (2021). The reshaping of political conflict over Europe: From pre-Maastricht to post-‘Euro crisis’. West European Politics, 44(3), 531–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1709754

- Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing in Europe. Effective and Democratic? Oxford University Press.

- Schimmelfennig, F., & Winzen, T. (2020). Ever Looser Union? Differentiated European integration. Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2013). Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: Input, output and ‘throughput’. Political Studies, 61(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x

- Schmidt, V. A. (2020). Europe’s Crisis of Legitimacy: Governing by Rules and Ruling by Numbers in the Eurozone. Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, V. A., & Wood, M. (2019). Conceptualizing throughput legitimacy: Procedural mechanisms of accountability, transparency, inclusiveness and openness in EU governance. Public Administration, 97(4), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12615

- Schneider, C. J. (2019). Euroscepticism and government accountability in the European union. The Review of International Organizations, 14(2), 217–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09358-w

- Schraff, D. & Schimmelfennig, F. (2020). Does differentiated integration strengthen the democratic legitimacy of the EU? Evidence from the 2015 Danish opt-out referendum. EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2020/11, http://diana-n.iue.it:8080/bitstream/handle/1814/66164/RSCAS%202020_11.pdf.

- Serrichio, F., Tsakatika, M., & Quaglia, L. (2013). Euroscepticism and the global financial crisis. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 51(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02299.x

- Slapin, J. B. (2011). Veto Power: Institutional Design in the European Union. University of Michigan Press.

- Stoeckel, F. (2013). Ambivalent or indifferent? Reconsidering the structure of EU public opinion. European Union Politics, 14(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512460736

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole Publishing.

- Treib, O. (2021). Euroscepticism is here to stay: What cleavage theory can teach us about the 2019 European Parliament elections. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(2), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1737881

- Van Elsas, E., & Van Der Brug, W. (2015). The changing relationship between left–right ideology and euroscepticism, 1973–2010. European Union Politics, 16(2), 194–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116514562918

- Van Ingelgom, V. (2014). Integrating Indifference: A Comparative, Qualitative and Quantitative Approach to the Legitimacy of European Integration. ECPR Press.

- Verhaegen, S. (2018). What to expect from European identity? Explaining support for solidarity in times of crisis. Comparative European Politics, 16(5), 871–904. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-017-0106-x

- Weßels, B. (2007). Discontent and European identity: Three types of euroscepticism. Acta Politica, 42(2-3), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500188

- Zeitlin, J., Nicoli, F., & Laffan, B. (2019). Introduction: The European Union beyond the polycrisis? Integration and politicization in an age of shifting cleavages. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 963–976. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619803

- Zürn, M., & De Wilde, P. (2016). Debating globalization: Cosmopolitanism and communitarianism as political ideologies. Journal of Political Ideologies, 21(3), 280–301. doi:10.1080/13569317.2016.1207741