ABSTRACT

Regulation is a prominent tool in what Kruck and Weiss call the Regulatory Security State. Safeguarding security entails shaping tech companies’ behaviour through arms-length rules, rather than wielding state capacity directly – a power shift away from state actors. As I argue, this dynamic also works in reverse: securitization of digital technology imposes security provision – a traditional state rationale – on regulatory domains hitherto dominated by commercial motivations. There is not only more regulation in security; there also is more security in regulation. This dynamic challenges the EU’s global regulatory entanglements. I use budding EU regulation of artificial intelligence (AI) to illustrate this struggle: do AI’s military implications weigh so heavily that its regulation should largely be seen through that lens? And should a transatlantic security alliance trump EU ambitions to craft its own AI governance approach? This fight is undecided yet. But given AI’s general-purpose character, its outcome will reverberate throughout society at large.

Introduction

Regulation has become a prominent tool in European security policy – so the premise Kruck and Weiss lay out in the introduction this special issue (Kruck & Weiss, 2023). As they and the other contributors to this joint effort demonstrate, multiple forces propel the rise of such a ‘regulatory security state’ (RSS) in the EU. Reflecting a general pattern in EU politics, member states have hesitated to transfer fiscal or military capabilities to the supranational level, leaving EU authorities with regulation as an alternative tool to positive state capacity in shaping political outcomes (Majone, Citation1994, Citation1996). In addition, rapid digital developments have fundamentally reshaped security landscapes, both domestically and in relations between states, as military equipment and operations feature more digital tech than ever before (Scharre, Citation2019). Largely digitized communication means that information gathering, too, relies on such technologies (Buchanan, Citation2020). And many domestic police forces have expanded their digital arsenal considerably.

This spread of proprietary digital tech is the central driver behind the rise of the RSS. The digitization of security means that safeguarding it entails shaping private companies’ behaviour through prescriptive rules, rather than wielding state capacity directly. The complexity of technologies involved demands tech knowledge to match, elevating the private actors developing them to prominent experts in the field.

Regulation as a tool of traditional security policy is a new departure, indeed, and one that deserves the kind of attention this special issue provides. That said, reflecting on the dynamics explored in it, two issues jump out that call for greater exploration. First, Kruck and Weiss (2023) highlight how the rise of the RSS stems from public actors’ increasing use of regulation in security matters – because they rely on (private) expertise, and because private actors control security-relevant resources, requiring arm’s length rules. In consequence, regulation invades the territory of the erstwhile ‘positive security state’ (PSS).Footnote1

The rise of the RSS has an additional root, however: security logics invading the domain of technology regulation. Over the past decades, digital infrastructures and technological developments have increasingly been securitized – constructed as security-relevant objects (Buzan et al., Citation1998; Wæver, Citation1995). Repeated cyber-attacks on digital infrastructures (Buchanan, Citation2020) have demonstrated the plausibility of such securitization, even if in principle objects’ security-relevance is never self-evident and itself subject to ideational struggles. The dynamics discussed in these pages, I argue, entail security usurping traditional regulatory terrain as much as regulation encroaching on security.

In that way, the rise of the RSS is a two-way road: it reflects the increasing dependence of state authorities on private actors in security provision – a power shift away from state actors. At the same time, it imposes security provision – a traditional state rationale – on regulatory domains hitherto dominated by other motivations. To fully capture the rise of the RSS we need to heed both the privatization of security-relevant practices and the securitization of regulation.

The second issue follows directly: securitization transforms not only domestic but also global regulatory politics. Domestically, security concerns can trump motivations that have traditionally animated regulation, including competitiveness, product safety, management of environmental impacts, and so on. The same is true internationally. Digital technologies were initially feted as exemplary manifestations of a borderless, globalized world. Now, they are integral to governments’ thinking about national power and vulnerabilities, vis-à-vis both domestic and foreign adversaries.

Much European regulation is embedded in global regulatory arrangements: shared technical standards, set for example by the International Organization for Standardization, or mutual recognition agreements, which facilitate cross-border trade where domestic standards differ. The impulse to rejig regulation from a security perspective can thus clash with the web of global regulatory entanglements of which the EU is part, including regulatory harmonization that had been agreed to raze behind-the-border barriers to smooth trade. The rise of the RSS changes global regulatory politics. But it is also conditioned by them because reneging on prior regulatory agreements may carry both a political and an economic cost. Such global dynamics are key dimensions of the rising RSS and deserve more attention than the contributions to this SI accord them.

As Kruck and Weiss (2023) highlight in their introduction, we witness a growing role for private expertise in public policy, including in the military domain, as digital technologies seep into more and more state functions. For the time being, it is hard to see what might reverse the ascendancy of the epistemic authority flowing from that. At the same time, the war against Ukraine has ushered in a reappreciation of more traditional geopolitical statecraft, to which digital security as well as offensive digital capabilities are once more tied. Political expediencies, and the politicians addressing them, have thus reasserted their authority in this domain. The result is more overt and immediate political intervention in technology policy where previously, arms-length principles had reigned – think of security-inspired procurement regimes for digital infrastructure technologies or tighter export restrictions.

In the same vein, the positive and the regulatory security state are not so much opposite ends of a continuum. As several of the contributions to this SI illustrate, both the EU and individual countries can and do use positive state capacity and regulatory policy simultaneously to make security policy. The key feature of the rising RSS, in that view, is the increasingly blurry boundary between regulatory and security policy – a blurriness that invites political struggles over the securitization across digital technologies (Dunn Cavelty, Citation2020).

In this contribution, I explore these dynamics in a new EU policy field: its budding regulation of artificial intelligence (AI). It is a fruitful case to illustrate what is at stake, given the ongoing struggles over the securitization of AI (cf. Bode & Huelss, Citation2023) and the competing conceptions of what that implies for global regulatory politics. Beyond that, as a general-purpose technology AI is spreading throughout sundry societal domains, such that its potential securitization, and the consequences for global regulatory politics, will reverberate throughout society at large. Because of its dual-use character (cf. Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023) and its uncertain future development, AI is particularly susceptible to the dynamics discussed in this special issue. As an extreme case, it illustrates well how research on the European RSS will have to heed both securitization and the global dynamics in which it is embedded.

Securitizing tech-regulation

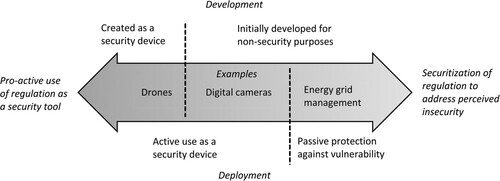

Security logics have encroached on the regulation of digital technologies from two directions: (1) through the enlisting of such technologies in security practices – and thus the pro-active use of regulation as a security tool – and (2) in response to the identification of digital technologies as vulnerabilities, so through the securitization of regulation to address perceived insecurity.

At the one end we find technologies specifically developed as security devices – weapon-carrying or reconnaissance drones, for example (Bode & Huelss, Citation2023). Many other technological developments discussed in this special issue also approach this end of the spectrum – for example Palantir’s Gotham software (Seidl & Obendiek, Citation2023) or much research financed through the European Defense Fund (Schilde, Citation2023; Hoeffler, Citation2023).

Then there are technologies that have not been created for security purposes but that can be used in this context, for example digital cameras. They also include infrastructures, for example payments networks (de Goede, Citation2012) or fibreoptic cables (Starosielski, Citation2015), access to which can be ‘weaponized’ in geopolitical conflict (Farrell & Newman, Citation2019). They also entail co-opting private company data gathering, for example of airline passengers or financial customers, from a security perspective (Bellanova & de Goede, Citation2022; Ulbricht, Citation2018).

At the other end of the spectrum are the vulnerabilities created by digital technologies, in particular the potential for the disruption of essential digital infrastructures such as energy grids or the work of ENISA (Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023). Here, regulation becomes a security-instrument because the domain it governs becomes security-relevant, like it or not.

These technologies differ in the degree to which they were actually developed as security devices or not, and whether they are actively deployed as security devices, or only regulated because they might constitute security vulnerabilities. depicts this continuum schematically.

The dominant framing of the RSS in this special issue emphasizes the left-hand side of : regulation is used to spur the development and govern the deployment and (non-)diffusion of technologies enlisted for security purposes. Equally important to the rise of the RSS, however, are the middle and right-hand segments of the figure, respectively: governments regulate technologies to co-opt their non-state operation and to leverage them for security policy – again, think of weaponized payments infrastructure – even though the security logics are not the only or even dominant ones structuring these operations. And they devise regulation to contain vulnerabilities, for example by forcing private operators of large IT systems to secure their systems.

The dynamics in the mid- and right-hand sections of are forms of securitization. I consciously use ‘securitization’ in a loose sense compared to the multiple attempts to pin down more definitively how it should be defined and identified (originally in Buzan et al., Citation1998; critically of the original formulation Balzacq et al., Citation2016; McDonald, Citation2008; Stritzel, Citation2007). As used here, securitization denotes the degree to which a referent object is understood and potentially governed as security-relevant, because it is seen as a security vulnerability, a security threat, or as a tool to enhance security. It is thus about privileging a security perspective on a referent object over alternative ones, for example individual rights, economic gains, and so on. The key securitization insight for our purposes is that referent objects – such as particular infrastructures or technologies – do not have an inherent and fixed security relevance, but one that is socially and politically constructed and can thus change independent of technological developments themselves.

Securitization moves have been part of the cyber and digital policy fields since their inception (Dunn Cavelty, Citation2020), not least given the heavy funding for computing technology and infrastructures from both US American and Soviet defence departments from the very beginning. That said, because digital technologies are so varied in their applications, and the field thus so blurry around the edges, the scope of appropriate securitization has always remained highly contested (Deibert, Citation2018; Hansen & Nissenbaum, Citation2009) – as most recently in the case of Huawei’s 5G technology (Friis & Lysne, Citation2021).

The consequences of such securitization are diverse. On the one hand, they can entail a re-assertion of unilateral public control over regulation, and therefore less willingness to pursue regulatory integration at all cost, for example to facilitate market opening. On the other hand, securitization can also mean that public authorities are more eager than ever to seek multilateral agreement, for example because they worry about arms-race like dynamics that might unfold otherwise.

Security-inspired governance of technology is nothing new – in terms of encouraging its development, regulating its use, and constraining its diffusion, for example through export restrictions (Daniels & Krige, Citation2022). But digitization adds a particular force to securitization. First, more and more aspects of our daily lives are underpinned by digital infrastructures – payment, navigation and communication systems, logistics, energy generation, and so on. Digitization has created many new vulnerabilities, not least because digital systems are susceptible to disruption at a distance. Second, digital technologies are inherently more difficult to contain geographically than material objects. Harmful software, for example, can in principle be moved around the globe at the click of a button. Less than is true for more material technologies (say, advanced missile systems), possession of the relevant knowledge or code is decisive, rather than access to specific materials or production facilities. This is a difference of degree, to be sure – to deploy advanced software, one still needs hardware and the personnel capable of operating it. But some technologies are still more ‘tied down materially’, embedded in specific and hard-to-make objects, than others.

The ubiquity and transferability of digital technologies thus enormously expands the scope for the RSS: as more and more parts of our lives have digital dimensions, more and more of them are potential targets for securitization.

Budding AI regulation in the EU and the struggle over its securitization

Artificial intelligence is an exemplary case to illustrate these dynamics: the struggle over how dominant a security-perspective should be, and hence to what degree technology governance should become entangled in the budding regulatory security state.

Artificial intelligence is a contested social construct rather than an unambiguously demarcated field (Proudfoot & Copeland, Citation2012). And it blurs into other dimensions of digital technologies, both material – infrastructures for data transmission, computers, data centres (K. Crawford, Citation2021) – and immaterial, under headings such as algorithms, machine learning, Big Data, and so on (Mitchell, Citation2019). Current EU attempts to regulate ‘AI’ therefore entail sharp disagreements about what the object regulation should be in the first place: the EU Commission’s April 2021 proposal (European Commission, Citation2021) consciously cast the regulatory net widely, also covering algorithms without a clear machine learning component (Veale & Zuiderveen Borgesius, Citation2021).Footnote2

Even in the EU, the first mover in this policy field, the shape of regulation is still emerging. At the time of writing, the European Parliament and the European Council debate the 2021 Commission proposal for an ‘AI Act’. Beyond the EU’s borders, the transatlantic Trade and Technology Council, launched in September 2021, brings together US American and EU delegates to bolster and coordinate technology governance, including that of AI (European Council, Citation2021). And globally, multilateral initiatives such as the 2020 Global Partnership on AI continue to debate international AI standards (Gouvernement Française, Citation2020).

Central to our discussion are fights over how to think about and then address the security implications of AI development and deployment. It is here that the securitization dynamic is in full view. It plays out both in AI use in domestic law enforcement, as well as military applications of AI, including autonomous weapons systems (Bode & Huelss, Citation2022).

AI, and its potential securitization, is so controversial because of AI’s manifold applications – it is, effectively, a general purpose technology (Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid, Citation2021). And like for example nuclear power, it has both civilian and military or security-related uses. Governments use AI-powered facial recognition systems in law enforcement and to control populations, notoriously in North-Western China (Byler, Citation2021). Automatic target identification and engagement through for example AI-enabled drones creates new possibilities for terrorist attacks and strategies on the battlefield (Scharre, Citation2019).

Different from nuclear power, however, its applications are so varied that they are not easily pigeonholed in the desirable versus undesirable categories. In addition, the future uses of AI are still unclear, even while we expect that more applications will quickly emerge (Ford, Citation2018; Lee & Chen, Citation2021) – a contrast to nuclear power, the two main applications of which (as a power source and a weapon) have remained unchanged for decades.

In consequence, European policymakers and AI experts disagree about the degree to which fledging AI regulation should be seen through a security lens: should, for example, remote biometric identification be banned entirely in the name of privacy and as a bulwark against abuses? Or should exceptions be made for law enforcement, and under which conditions? Irrespective of what the outcome will be exactly, it is this struggle over AI’s securitization that will determine the eventual scope and shape of the RSS in this field.

As debates unfold, governments heavily depend on private sector expertise because AI is evolving so rapidly. For other forms of technology, governments can eventually acquire the relevant knowledge, even if they lag private sector developments. In AI, in contrast, an understanding of yesterday’s technological capabilities is insufficient to understand today’s possibilities. Obendiek and Seidl (Citation2023) cite Lewallen’s observation that ‘actors struggle to navigate new risks and opportunities, as technologies ‘emerge and change faster than institutions can develop a collective understanding of [them]’ (Lewallen, Citation2021, p. 1).’ With a technology that is quickly evolving, the knowledge advantage of the tech developers is permanent (cf. Taeihagh et al., Citation2021).

The evolving knowledge about AI’s capabilities allows experts to shape its overall framing. Bode and Huelss (Citation2023) argue that point for military applications of AI, underlining how the Global Tech Panel advising the EU heavily involves the American armaments industry. This dependence on external expertise equally extends to non-military applications of AI. It is particularly acute because the expertise gap on the government side is not only about mastering the application of a technology – say, how to build a satellite-based navigation system – but also about the potential implications – so the question what it would even be capable of. The scope for selling technologies to governments that the latter do not need, or for pushing regulations that are superfluous, becomes even wider.

Securitization is then not only driven by public actors’ knowing what private expertise they need, but also by their inability to gauge that expertise-requirement confidently. As long as narratives about security implications are plausible, scope for regulatory capture grows in sync with government uncertainty (Dal Bó, Citation2006; Stigler, Citation1971). Echoing the constructivist perspective emphasized by Kruck and Weiss (2023) in the special issue introduction, the rise of the RSS does not mirror objective and unambiguous technological developments, but the contested ways in which actors make sense of them.

Political authority as a source of legitimacy remains vulnerable to the private-sector charge that public officials simply do not understand the domain they try to govern. In principle, this dynamic is likely to persist unless governments build in-house expertise to match that of the private sector – and even the US Department of Defence, with its enormous budget, contracts out most of its AI work to private companies. That said, the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine has rekindled more traditional views of geopolitics and statecraft, rooted in political authority. To what degree that strengthens its sway at the expense of private expertise also in AI governance remains an open question.

Either way, the overall impact of securitization becomes bigger as the line between security-relevant and -irrelevant applications blurs. As a general-purpose technology, AI does not operate on its own, like a separate set of armaments. Instead, it can supercharge existing instruments and weapons, be they fighter jets, hacking attacks, surveillance and targeting, and so on. Many of AI systems’ abilities – navigation, breaking encryption, object identification, real-time monitoring of large amounts of data – have dual uses (Smith & Browne, Citation2019). They can be used in innocuous ways, but also for military ends. An ‘in case of doubt, securitize’-logic draws an extensive range of technologies and applications into the regulatory web of the RSS, with a reach far beyond the RSS as a mere substitute for the traditional positive security state.

Regulatory interdependence in the shadow of securitization

The European security state, regulatory or otherwise, is embedded in a global geopolitical and regulatory context; indeed, fear of EU-external sources of insecurity help legitimize the security state in the first place. So what does the shift from a PSS to an RSS imply for international politics, both viewed from a regulatory and from a security angle?

In essence, international regulatory politics is about managing regulatory interdependence (Lazer, Citation2001) – the domestic effects of other jurisdictions’ rules. Traditionally they have been viewed through an economic lens: aligned rules facilitate cross-border trade; incompatible rules obstruct system interoperability. Relatively lax rules can translate into a competitive advantage; onerous ones into a barrier to trade and regulatory protectionism. Potential races to the bottom (Tiebout, Citation1956) can induce insufficiently stringent rules. Powerful jurisdictions can then arm-twist others into applying higher standards, as well (Simmons, Citation2001; Singer, Citation2007) or simply use domestic market access to externalize domestic regimes (Damro, Citation2012; Vogel, Citation1995).

Once regulation is viewed through a security lens, this dynamic shifts. Traditional goals of international regulatory policy – for example to ensure smooth trade relations, or to create competitive advantage for domestic producers, are compromised. A relative gains logic, in which wins for some imply losses for other, gains at the expense of a win-win scenario. Technology and knowledge will be shared more reluctantly (Daniels & Krige, Citation2022), hampering overall innovation.

At their broadest, global security concerns can shift international economic cooperation overall into a competitive and essentially realist mode (cf. B. Crawford, Citation1995). In terms of traditional IR theorizing, relative gains become more important than absolute ones, limiting the scope for cooperation to those instances which do not upset pre-established power balances. Given uncertain future effects of for example knowledge sharing, risk-averse governments can be expected to restrict cooperation with potential adversaries significantly. Simultaneously, a securitization logic aligns regulatory cooperation with pre-existing alliances.

Consider for example the securitization of finance, first in the enlisting of banks as counter-terrorism actors (Bosma, Citation2022), and second, in the use of the SWIFT network as a lever to punish for example Russia and Iran. Regulatory interdependence can not only be a source of vulnerability, or potential economic losses when a security logic takes over; it can also be a weapon to be wielded (cf. Farrell & Newman, Citation2019).

The securitization of tech regulation thus empowers the EU vis-à-vis its member states in the security domain because its core competences – trade, and product and market regulation – are drawn into security politics. The net effect on Europe’s global position is less clear. On the one hand, Europe has successfully used internal market regulation to change market rules and policies more generally beyond its own borders (Damro, Citation2012). The EU traditionally has more clout as a regulatory power than as a military power, such that the rise of the RSS would seem to strengthen its hand. On the other hand, the securitization of regulation actually limits the autonomy the EU has to use it as a general-purpose political tool. If, for example, rules for accessing European tech markets are dictated by security considerations, selective market access can no longer freely be used to extract concessions from third countries in other domains. In any case, as the RSS further blurs the line between security and economic logics in global regulatory politics, the EU will find that other international organizations, for example NATO, will have more effective sway over questions where previously the European Commission could act largely unencumbered.

AI securitization and its global regulatory consequences

In EU AI regulation, securitization has come from two main angles. In the domestic context, AI’s ability to detect patterns in large data sets and to recognize people from images, sound or video have long been identified as potential law enforcement tools. While the proposal for a European AI Act (European Commission, Citation2021) suggests bans for most forms of public AI-powered remote biometric identification – such as facial recognition in public spaces – it makes exceptions for various forms of law enforcement, much to the horror of privacy advocates and members of the European Parliament. After all, such systems had invited widespread criticism, because of their discriminatory (cf. Benjamin, Citation2019; D’Ignazio & Klein, Citation2020) and oppressive potential (cf. Byler, Citation2021 for the Chinese case). No matter which way this debate eventually goes, the security relevance of AI means that regulation will be an important pillar of how this facet of the security assemblage will be governed. In this domain, the security state is by default a regulatory security state.

It is in the international context, however, that we most clearly see the wider ripples caused by securitization. In essence, the EU had been stylizing its own approach to AI as a ‘human-centric’ one, distinct from the relative corporate laissez-faire prevailing in the USA and government co-option of AI for surveillance and population control in China. Much debate, also by EU actors themselves (e.g., European Commission, Citation2018; European Data Protection Supervisor, Citation2016), has focused on the norms underpinning AI development and deployment; US discourse, in contract, has largely framed AI development as a central plank in the geostrategic competition between America and China (Atkinson, Citation2021; National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, Citation2021). In that narrative (skeptically Bryson & Malikova, Citation2021; affirmatively Lee, Citation2018), Europe is deluded in its ambition for a ‘third way’ on AI; instead, it has to join a US-led alliance of ‘like-minded countries’ in order to contain China’s technological rise. The regulatory interdependence that characterizes AI means that regulatory politics themselves become a wager in the struggle over AI’s securitization (Mügge, Citation2022).

Even as it is undecided as of yet, the regulatory stakes in this debate are enormous: successful securitization of AI – a security-inspired EU-US alliance on AI – would imply far-reaching Transatlantic regulatory cooperation to create an integrated regulatory space and to join AI forces, as it were. At the same time, it would argue against global regulatory cooperation that would facilitate the indiscriminate cross-border flow of knowledge and technology. And it would smother an EU attempt to carve out a regulatory space much different than the US American one.

Pecking orders shift, too. The size of Europe’s internal market as a power lever over international regulation loses in importance relative to security or military capabilities. Even before the war in Ukraine, Russian cyber capacities had become a serious consideration even though as a market for or supplier of digital tech, Russia is not particularly relevant.

This struggle over the securitization of AI regulation unfolds even though the European Commission – with few competences in the external security field (cf. Bode & Huelss, Citation2023) – had consciously excluded military AI applications from its proposed regulation. To no avail, it seems: the dual use character of AI and the putative need for more encompassing tech alliances has allowed securitization dynamics to seep into a regulatory domain that had tried to keep them at bay.

Admittedly, the geostrategic dimension of economic regulation may have been more prominent in both China and the USA all along. Technology-sharing provisions in joint ventures, for example, have contributed to rapid high-tech development in China, which by now also bolsters its military capacities. And certainly in US cross-border technology sharing policies, security considerations have figured throughout the decades (Daniels & Krige, Citation2022). Leveraging putatively economic instruments with an eye to geostrategic competition is thus less novel than it may seem from a European vantage point. In any case, it is clear that research on the European RSS needs to take seriously the global and securitized politics of digital tech innovation.

Conclusion

Most contributions to this special issue highlight that RSS elements exists next to PSS ones. The rise of the RSS, I have argued, stems not only from private technologies’ co-optation into security policies; it equally flows from the (plausible) perception that regulated technologies are increasingly security relevant, if only as points of societal vulnerability. Securitization of regulation is a central driver of the RSS, next to the growing use of regulation in domains hitherto dominated by positive state capacity.

Going a step further, Dunn Cavelty and Smeets (Citation2023) suggest that maybe, we should not conceptualize the PSS and the RSS as a continuum, but as two separate axes of security governance. The current European military build-up in response to the war in Ukraine demonstrates how positive state capacity is everything but yesterday’s thing. Instead, as that war has shattered hopes that military confrontation in Europe had become unthinkable, both the positive and the regulatory security states are now being expanded. Even then, the pace with which especially digital technologies evolve solidifies public actors’ dependence on the expertise of private tech developers. This source of regulation, rather than positive state capacity, as a plank of security policy is likely to stay with us.

The fledging regulation of AI allows us to observe these dynamics in real-time. Different actors struggle to define how and when security considerations should take precedence over values such as individual privacy or autonomy, and whether geo-political alliances should trump the EU’s ambition to position itself as an alternative to both Chinese and American models of AI regulation. The AI case shows, above all, that securitization itself is contested, and that the extent of an RSS in this field is not exogenously determined by technological developments, but itself an artefact of political and discursive struggles as well as domain-specific global contexts. Both deserve explicit attention from future scholars of the RSS, whatever domain they investigate.

The growing securitization of tech regulation reverberates far beyond the security domain itself: it substitutes a sceptical friend-or-foe mindset for an economically motivated take on regulatory cooperation. Digital technologies were never quite as untethered from territorially bound politics as their early prophets hoped and proclaimed; nevertheless, current trends tie them back into geo-political dynamics even more than was true just some years ago. Instead of being a tool for managed globalization, selective regulatory cooperation may in many fields become a plank of geopolitics. For a polity that has emphasized regulation as a tool as heavily as the European Union has, this is all the more reason to heed the rise of the RSS and the momentous changes it may usher in.

Acknowledgements

I am enormously grateful to the editors of this special issue, the participants of the workshops supporting it, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their enormously helpful comments. I thankfully acknowledge funding for that workshop by the Fritz-Thyssen-Stiftung.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniel Mügge

Daniel Mügge is Professor of Political Arithmetic at the University of Amsterdam. He researchers the EU's regulation of artificial intelligence and how that is shaped by global political and economic dynamics.

Notes

1 To be sure, as Hoeffler (Citation2023) shows in this SI, this trend is no one-way road. Unintended consequences of privatized security, or simply disappointment with it, have repeatedly pushed public authorities to fold activities back into the more traditional ‘positive’ security state. The RSS is thus not understood here as a replacement for a previous PSS, but as a mode of security governance that has grown in importance, and that exists alongside traditional, positive state capacity in security provision. In this issue, Schilde (Citation2023) too argues that regulatory instruments have been part of the security governance toolbox all along.

2 For the purpose of this contribution, I stick to a pragmatic AI definition from an earlier Commission communication: ‘systems that display intelligent behaviour by analysing their environment and taking actions – with some degree of autonomy – to achieve specific goals’ (European Commission, Citation2018, p. 2).

References

- Atkinson, R. (2021). A U.S. grand strategy for the global digital economy. https://itif.org/publications/2021/01/19/us-grand-strategy-global-digital-economy.

- Balzacq, T., Léonard, S., & Ruzicka, J. (2016). ‘Securitization’ revisited: theory and cases. International Relations, 30(4), 494–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117815596590

- Bellanova, R., & de Goede, M. (2022). The algorithmic regulation of security: An infrastructural perspective. Regulation & Governance, 16(1), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12338

- Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology. Polity Press.

- Bode, I., & Huelss, H. (2022). Autonomous weapons systems and international norms. McGill University Press.

- Bode, I., & Huelss, H. (2023). Constructing expertise: The front- and back-door regulation of AI’s military applications in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1230–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174169

- Bosma, E. (2022). Banks as security actors. Countering terrorist financing at the human-technology interface [University of Amsterdam]. https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=e6e51a1c-f4b0-4aff-80a2-3ae47ace21dd.

- Bryson, J. J., & Malikova, H. (2021). Is there an AI cold War? Global Perspectives, 2(1), https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2021.24803

- Buchanan, B. (2020). The hacker and the state. Cyber attacks and the new normal of geopolitics. Harvard University Press.

- Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & De Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Byler, D. (2021). In the camps. China’s high-tech penal colony. Columbia Global Reports.

- Council, E. (2021). EU-US summit joint statement: “Towards a renewed Transatlantic partnership. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2021/06/15/eu-us-summit-statement-towards-a-renewed-transatlantic-partnership/.

- Crawford, B. (1995). Hawks, doves, but no owls: International economic interdependence and construction of the new security dilemma. In R. Lipschutz (Ed.), On security (pp. 149–186). Columbia University Press.

- Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI. Yale University Press.

- Dal Bó, E. (2006). Regulatory capture: A review. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 22(2), 203–225. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grj013

- Damro, C. (2012). Market power Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(5), 682–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.646779

- Daniels, M., & Krige, J. (2022). Knowledge regulation and national security in postwar America. Chicago University Press.

- de Goede, M. (2012). The SWIFT affair and the global politics of European security. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 50(2), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02219.x

- Deibert, R. (2018). Trajectories for future cybersecurity research. In A. Gheciu, & W. C. Wohlforth (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of international security (pp. 531–546). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198777854.013.35.

- D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. (2020). Data feminism. MIT Press.

- Dunn Cavelty, M. (2020). Cybersecurity between hypersecuritization and technologial routine. In E. Tikk, & M. Kerttunen (Eds.), Routledge handbook of international cybersecurity (pp. 11–21). Routledge.

- Dunn Cavelty, M., & Smeets, M. (2023). Regulatory cybersecurity governance in the making: The formation of ENISA and its struggle for epistemic authority. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1330–1352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2173274

- European Commission. (2018). Artificial Intelligence for Europe [COM(2018) 237 final].

- European Commission. (2021). Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the council laying down harmonized rules on artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and Amending Certain Legislative Acts [COM(2021) 206 final].

- European Data Protection Supervisor. (2016). Artificial intelligence, robotics, privacy and data protection. https://edps.europa.eu/sites/edp/files/publication/16-10-19_marrakesh_ai_paper_en.pdf.

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. L. (2019). Weaponized interdependence: How global economic networks shape StateCoercion. International Security, 44(1), 42–79. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00351

- Ford, M. (2018). Architects of Intelligence. The truth about AI from the people building it. Packt Publishers.

- Friis, K., & Lysne, O. (2021). Huawei, 5G and security: Technological limitations and political responses. Development and Change, 52(5), 1174–1195. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12680

- Gouvernement Française. (2020). Launch of the global partnership on artificial intelligence. https://www.gouvernement.fr/en/launch-of-the-global-partnership-on-artificial-intelligence.

- Hansen, L., & Nissenbaum, H. (2009). Digital disaster, cyber security, and the Copenhagen school. International Studies Quarterly, 53(4), 1155–1175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00572.x

- Hoeffler, C. (2023). Beyond the regulatory state? The European Defence Fund and national military capacities. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1281–1304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174581

- Lazer, D. (2001). Regulatory interdependence and international governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 8(3), 474–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760110056077

- Lee, K.-F. (2018). Ai superpowers. China, silicon valley, and the new world order. Houghton Mifflin.

- Lee, K.-F., & Chen, Q. (2021). AI 2041. Currency.

- Lewallen, J. (2021). Emerging technologies and problem definition uncertainty: The case of cybersecurity. Regulation & Governance, 15(4), 1035–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12341

- Majone, G. (1994). The rise of the regulatory state in Europe. West European Politics, 17(3), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389408425031

- Majone, G. (1996). Regulating Europe. Routledge.

- McDonald, M. (2008). Securitization and the construction of security. European Journal of International Relations, 14(4), 563–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066108097553

- Mitchell, M. (2019). Artificial intelligence. A guide for thinking humans. Pelican Books.

- Mügge, D. (2022). Regulatory Interdependence in Artificial Intelligence. https://www.ippi.org.il/regulatory-interdependence-in-artificial-intelligence/.

- National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence. (2021). Final Report.

- Obendiek, A., & Seidl, T. (2023). The (False) promise of solutionism: Ideational business power and the construction of epistemic authority in digital security governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1305–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2172060

- Proudfoot, D., & Copeland, J. (2012). Artificial intelligence. In E. Margolis, R. Samuels, & S. Stich (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of philosophy of cognitive science (pp. 147–182). Oxford University Press.

- Scharre, P. (2019). Army of none: Autonomous weapons and the future of War. W.W. Norton.

- Schilde, K. (2023). Weaponising Europe? Rule-makers and rule-takers in in the EU security state. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1255–1280. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174582

- Simmons, B. (2001). The international politics of harmonization: The case of capital market regulation. International Organization, 55(3), 589–620. https://doi.org/10.1162/00208180152507560

- Singer, D. (2007). Regulating capital. Setting standards for the international financial system. Cornell University Press.

- Sivan-Sevilla, I. (2023). Supranational security states for national security problems: Governing by rules and capacities in technology-driven European security spaces. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1353–1378. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2172063

- Smith, B., & Browne, C. A. (2019). Tools and weapons. The promise and peril of the digital Age. Penguin.

- Starosielski, N. (2015). The undersea network. Duke University Press.

- Stigler, G. (1971). The theory of economic regulation. Bell Journal of Economics, 2(1), 113–121.

- Stritzel, H. (2007). Towards a theory of securitization: Copenhagen and beyond. European Journal of International Relations, 13(3), 357–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066107080128

- Taeihagh, A., Ramesh, M., & Howlett, M. (2021). Assessing the regulatory challenges of emerging disruptive technologies. Regulation & Governance, 15(4), 1009–1019. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12392

- Tiebout, C. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64(5), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.1086/257839

- Ulbricht, L. (2018). When big data meet securitization. Algorithmic regulation with passenger name records. European Journal for Security Research, 3(2), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41125-018-0030-3

- Veale, M., & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. (2021). Demystifying the Draft EU Artificial Intelligence Act — Analysing the good, the bad, and the unclear elements of the proposed approach. Computer Law Review International, 22(4), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.9785/cri-2021-220402

- Vogel, D. (1995). Trading up. Consumer and environmental regulation in a global economy. Harvard University Press.

- Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid. (2021). Opgave AI. De nieuwe systeemtechnologie. WRR.

- Wæver, O. (1995). Securitization and desecuritization. In R. Lipschutz (Ed.), On security (pp. 46–86). Columbia University Press.