ABSTRACT

The Regulatory Security State (RSS) has far-reaching political consequences for the world beyond the EU, for EU priorities and its ability to realize them. We show this point through an analysis of how the extension of the RSS into the digital played into a constellation of factors that skewed politics towards the 2018 election of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil. We trace the connections from the General Data Protection Regulation through shifts in Facebook’s self-regulation to the Brazilian elections with the help of three conceptual tools: ‘infrastructures’, ‘regulatory design’ and ‘ripples’: the GDPR generated a regulatory redesign of infrastructures sending ripples travelling from the EU to Brazil, back and beyond. We contribute theoretically by developing concepts for contextualizing the RSS and empirically by demonstrating the political stakes of contextualizing the RSS. Both contributions have a bearing for analyzes of the RSS beyond the case we focus on.

Introduction

The EU has become increasingly concerned with and involved in digital security.Footnote1 The result is a wide range of regulations, directives, judgements and policies. The EU has branched out into digital security, creating a dense undergrowth of regulation. Many observers welcome this extension of the EU into the digital as securing a safe, open digital space.Footnote2 It charts a route avoiding both the Scylla of surveillance by invasive intelligence agencies and the Charybdis of market capture by the ever more powerful platforms or US based ‘GAFAM’ (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft). The EU justifies the extension of the Regulatory Security State (RSS) into the digital in ambitious and enthusiastic terms. It is securing an open digital space for the benefit not only for the EU and its citizens but more broadly for the rest of the world. According to the Commission press release launching Europe’s Digital Decade: ‘the EU will work to promote its positive and human-centered digital agenda within international organizations and through strong international digital partnerships’.Footnote3 As Margrethe Vestager enthusiastically explained:

[This] is the start of an inclusive process. Together with the European Parliament, the Member States and other stakeholders, we will work for Europe to become the prosperous, confident and open partner that we want to be in the world. And make sure that all of us fully benefit from the welfare brought by an inclusive digital society.Footnote4

Is the extension of the EU into digital living up to these ambitions? Does the EU deliver on ‘its well-intended plethora of promising policies’ (Irion et al., Citation2021, p. 5)? And what are the implications for the EU and the rest of the world of the way it is doing this?

This article explores these broader questions by asking how the extension of the European Regulatory Security State (RSS) into the digital is affecting the Global South. As the introduction posits, the ‘regulatory’ state differs from the ‘positive’ state by its reliance on indirect regulation, epistemic authority and expertise (Kruck & Weiss, Citation2023). In the field of digital security, this is particularly true. The digital operates largely through commercial platforms and networks, regulation works ‘indirectly’ through them, and epistemic authority and expertise lie with them (also Monsees et al., Citation2023; Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023). Our contribution will advance the discussion of the RSS in three directions. First, the discussion is dominated by a focus on the construction of regulation, expertise and authority associated with the emergence of the RSS. By contrast, we shift the weight of attention towards its political consequences. While the two are connected, this shift matters. We cannot assume that the presence of actors, institutions and ideas in the RSS translate into political consequences that mirror this presence and whatever we associate with it. Shifting the analytical emphasis from construction, formation or emergence to consequences is to acknowledge and probe this possible discrepancy. It is to ask what the RSS does rather than how it is constructed. Second, by connecting the RSS to the context beyond Europe; focussing on its consequences for democracy in the ‘Global South’. Third, by anchoring it materially in the digital infrastructures – the ‘internet’ – through which ‘indirect regulation’ operates and with which ‘epistemic authority’ and ‘expertise’ are entangled. We, in clear, connect the EU RSS: the ‘EU’ is connected to the Global South, ‘Regulatory’ to the codes and protocols of commercial platforms and the ‘Security State’ to socio-material infrastructures. Methodologically, we move from the small and detailed to the big and abstract observing ‘the world in a grain of sand’ (Strathern, Citation2018, p. 62). We focus on the connections between one measure adopted as part of the extension of the RSS into the digital and one specific political process in the Global South: those between the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Facebook’s place in the physically and symbolically violent 2018 presidential election process in Brazil. Our core claim is that the GDPR sent ‘ripples’ skewing the ‘digital infrastructuring’ of Brazilian democracy towards the (alt-)right as exemplified by the role of Facebook. We also point out that the ripples return. The developments in Brazil undermine the broader EU agenda to support an open and democratic digital space, moving that agenda beyond its reach.

As the reference to ‘ripples’ underscores, while there is a connection between the RSS and the rest of world, it is not straightforwardly causal. Rather, the GDPR played into a broader context pressuring social-media platforms generally and Facebook specifically to revise their data protection regulation. The resulting redesign skewed the 2018 Brazilian election process. The connection between the RSS as exemplified by the GDPR and political processes in the Global South exemplified by the 2018 Brazilian elections is non-linear. It is a ripple rather than a fixed connection. Ripples diffract as they run into other processes and interfere with them in ways difficult to predict. So do connections running from the RSS to Brazil. While blaming the EU and Facebook for the outcomes of the 2018 elections in Brazil therefore seems farfetched, the ripples recall the ethical import of tending to the effects of the RSS beyond the EU with care and concern. Focussing on the ‘ripples’ is a way to do this as it helps trace the non-linear complex scaling of regulatory initiatives more generally. In elaborating this claim, we connect and contribute to two on going debates beyond those surrounding the RSS. First, we address the scholarship on infrastructures in International Relations and beyond (e.g., Aradau, Citation2010; Peters, Citation2015; Leander, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Elbe, Citation2022; Star, Citation1999). We break with accounts downplaying the contextually differentiated and unequal qualities of infrastructuring processes by highlighting their ‘topological’ character (Fuller & Goffey, Citation2012) and its implications for how the redesigning of regulatory infrastructures connected to the GDPR played out in Brazil. We do so by shifting the vocabulary of infrastructural change from inscriptions (e.g., Akrich, Citation1992; Pelizza & Aradau, Citation2023) to ripples, thus emphasizing movements rather than events. Moreover, we engage the discussion about the role of social media – Facebook, specifically – in the 2018 Brazilian elections that generally neglects the world beyond the country and if/when it notices it, stresses almost exclusively platforms, markets and the US (e.g., Iglesias Keller, Citation2020). By emphasizing the significance of the RSS, we redress the general neglect of the transnational context, recall the significance of regulation and decentre the US by focusing on the EU.

We begin by laying out our theoretical approach to the effects of the expansion of the RSS into digital security, situating three core conceptual tools we work with: the ripples through which the RSS fashions the regulatory design of digital infrastructures. We then mobilize these theoretical tools to connect the extension of the RSS into the digital to the Brazilian 2018 presidential elections. We show that the GDPR sent ripples of regulatory redesign into digital infrastructures as Online Service Providers (OSPs) – we focus on Facebook – adjusted their activities. We further demonstrate that – in constellations with the other factors – these ripples and the related redesign skewed the digital infrastructuring of the presidential elections towards Jair Bolsonaro. We conclude by discussing the ‘return’ ripples from the Brazilian process to the RSS, the EU and digital infrastructures generally, underscoring that they undermine the EU aim of securing open democratic digital spaces. Instead, they enshrine and reinforce the centrality of OSPs for the regulation and security of digital spaces and the presence of anti-democratic movements within them.

Ripples in the regulatory design of infrastructures

To grapple with the question of whether the extension of the RSS into the digital can live up to its ambitions of securing an open and safe online environment for all, we need conceptual tools allowing us to trace the effects of the ERSS and compose an image of said effects. Picking from the toolbox of the extensive literature on digital processes and their regulation, we rely on the concepts of infrastructures and regulatory design. Then, we add a third one: ripples.

Infrastructure has become a common trope for thinking about how the internet operates as it helpfully captures the materially entangled character of online activities. Its utility however is not limited to the internet. Rather it is pervasive to an extent that makes Peters (Citation2015, p. 35) claim that the social sciences are going through a period of ‘infrastructuralism’. In the context of thinking about online activities, infrastructure is helpful because it recalls the fundamental import of the basic material things such as the cables, servers, computers, pads, phones and screens through which the digital necessarily operates (Knorr-Cetina, Citation1997; Starosielski, Citation2015). Moreover, referring to infrastructures is to recall that digital activities and their regulation are inscribed in the networks afforded by these things. The scale and speed of online transactions are such that regulation is necessarily designed into the infrastructure. For example, programmes that detect or sense ‘anomalies’ in the form of specific spatial ‘dots’, temporal ‘spikes’ and topological ‘nodes’ regulate security online (Aradau & Blanke, Citation2018). Lessig’s (Citation2009) claim that ‘Law is Code and Code is Law’ was an early statement of the implications of infrastructural thinking in the sphere of the digital. His point is that rather the rules regulating the digital are the technical codes that define its operations. Algorithms, protocols and technical standards matter more than laws, decrees or treaties. Lessig’s early formulation overstates the regulatory implications, implying that ‘code’ has autonomous quasi-magic agency, exercising a form of ‘sorcery’ beyond human agency (Chun, Citation2008). However, his basic contention – that regulation operates through digital infrastructures – is fundamentally justified. Versions of it continue to occupy a central place in debates surrounding the regulation of the digital (e.g., Johns & Compton, Citation2022; Sullivan, Citation2022).

Following this, we conceptualize regulation as an infrastructural process and, therefore, see the extension of the RSS into the digital operating infrastructurally. In matters digital, regulation is not of but by infrastructures (DeNardis & Musiani, Citation2016). The steadily increasing concentration of the digital economy have given ‘infrastructural platforms’ a core place in this regulation and more broadly in fashioning meaning and values of our contemporary societies (Van Dijck et al., Citation2018). The platform image underlines an aspect of digital infrastructures well worth highlighting. It directs attention to the diverse heterogeneity of activities that they host and to the fact that these might change the nature of the platform itself. This image, however, downplays the extent to which the platforms also structure and define – infrastructure – the activities they host (Gillespie, Citation2018). The term platform also understates the extent to which entrepreneurial ‘changemakers’ are constantly redefining the foundations according to which they operate (Arvidsson, Citation2019). Digital infrastructures are far from fixed, uniform or singular. The analogy to a dam or road in that sense is misleading as it intimates the permanent and static. Digital infrastructures are dynamically evolving. A ‘stack’ may be a better analogy (Bratton, Citation2016). It recalls the heterogeneity of composition, the inequalities inscribed in its memory and operations. Yet ‘stack’ may also be too firm? The image of sticks and other material downplay the diffuse, ‘capillary’ processes of change at work in digital infrastructures. The overused and abused image of the ‘liquid’ may be more helpful here. Reflecting on the expansion of the RSS into the digital is, in other words, to reflect on how it connects to such fluid, complex infrastructures and the capillary processes of ongoing regulation and regulatory change in them.

To analytically explore the extension of the RSS, we need conceptual tools to denote the connection between it and infrastructural regulations. For this, we propose regulatory design. The concept directs attention to a regulation that operates via infrastructural ‘form’; that is via ‘design’. This is no longer simply a matter of the ‘regulatory’ role that codes and protocols play in the digital context. It is also a matter of regulators consciously requiring that regulation be technically encoded (Vertesi et al., Citation2016). The GDPR – which we focus on below – has been associated with such regulation by design: ‘An important legal novelty introduced by the GDPR is data protection by design, according to which fundamental rights become matters of engineering and design, hardcoding law into digital artefacts, infrastructures and data streams’ (Rommetveit & van Dijk, Citation2022, p. 1 emphasis added). The expression regulatory design denotes the specific contours and texture of a regulation taking place by infrastructure. It is not primarily highlighting the intentional and strategic design of regulation – that obviously exist and matter – but the ways in which the form of regulatory infrastructures design political possibilities. Focussing on regulatory design, it becomes possible to conceive of the regulatory agency as located in infrastructural processes, rather than with regulators. In our context, it shifts attention from the choices, decisions and discourses of EU regulators, institutions, courts, OSPs, etc. to the performativity of the codes, protocols and technical standards developed in response to these. Simply put, regulatory design shifts the locus of agency from the subject to the technical processes.

The technical literature on the subject mostly welcomes the increasing centrality of regulation by design. It explicitly centres the technical implication in regulation (Ribes & Vertesi, Citation2019). The implications are more problematic from a legal and regulatory perspective. The centring of technology has disturbing normative consequences. If regulatory agency is in technical infrastructural processes, does it make sense at all to think in terms of ‘agency’ at all? Do we not get caught in a pernicious determinism where ‘processes’ decide what will happen, conveniently exempting the powers of this world from their responsibility? Because of the discomfort such questions create, many scholars strive to relocate agency with subjects. One way of doing this is to follow Jane Bennett in theorizing the ‘agency of assemblages’ that ‘owes its agentic capacity to the vitality of the materialities that constitute it’ (Bennett, Citation2010, p. 34). It is a ‘congregational’ agency that depends on the combination of such vitalities (Bennett, Citation2010, p. 32). It is therefore also ‘distributed’ across multiple bodies, human and non-human (Bennett, Citation2010, p. 32). Such redefined agency is ‘messy’ (Bennett, Citation2010; Ziewitz, Citation2016). As Bennett argues, this undermines a politics of blame focussed on individual moral responsibility that is important in certain political situations (Bennett, Citation2010, p. 38). The alternative it opens is one that ‘acknowledges the distributive quality of agency to address the power of human-nonhuman assemblages’ (Bennett, Citation2010, p. 40). This is important in situations where separating moral judgement from an ethics of political action is the precondition for responsibly dealing with accountability of the materially entangled such as the regulatory design of digital infrastructures.

Working with the concept of regulatory design and the processes connected to the forms of infrastructures despite the discomforts entailed is, in clear, warranted because the analytical and normative price of not doing so is too high. Re-centring on more conventional subject-focussed notions of agency is to marginalize the material infrastructural aspects of agency from the analysis or perhaps to expel them entirely. With this, the leverage over the political and ethical challenges of the material and infrastructural weakens. Centrally, regulatory design counters the pervasive tendency to connect back to the familiar and firm grounds where fixed subjects play the core role. It helps counter the temptation to reintroduce the ‘human in the loop’ or the ‘algorithm’ as an atomistic locus of agency. While both obviously matter for regulation, their agency operates through ‘the assemblages’ of which they are part of. Isolating them, distracts from the processual connections through which they come to matter and from the shape shifting and evolving character of these connections. Focussing on design is to concentrate on the patterns connecting ‘value laden’ algorithms (Bode & Huelss, Citation2023, p. 8) and the priorities of Alex Karp CEO of Palantir (Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023) and the regulatory processes they generate. Translated to our context, working with regulatory design is a way of privileging the process and connections through which the extension of the RSS into the digital generates effects. It is a way of giving full attention to the ‘dispositional’, emergent and uncertain through which such regulation operates. The ‘architectural or design-based techniques of control’ are at the core of algorithmic regulation as Yeung insists (Citation2018, p. 509; also Zalnieriute & Milan, Citation2019). Regulation is an ‘active form’ accommodating and transforming through the emerging and uncertain (Easterling, Citation2012). Focussing on ‘regulatory design’ is to direct attention to such processes.

This leads to our third concept, ripples. Ripples or more technically ‘capillary waves’ are helpful to think about the processes though which regulatory designs spread, travel and scale across digital infrastructures. Unlike the two previous concepts, this one is not already widely used in the analysis of digital regulation. But perhaps it should be. First, because it attunes to variety and so to the capillary processes underpinning digital infrastructures. ‘A stone dropped into a pond produces a ripple pattern. Two stones dropped into the same pond produce two ripple patterns. Where the ripples intersect, a new and complex pattern emerges, reducible to neither one nor the other’ (Manning & Massumi, Citation2014, p. viii). In complex and heterogeneous digital infrastructures where regulation can come from many sources and take many forms, the image that regulation is generating its distinct ripples that engendering complex patterns as they intersect with other regulatory ripples marking digital infrastructure. The image of ripples also retains a sensitivity to the implications of the unevenness of the infrastructural topography for the influence of any regulatory initiative.

Although classically defined by its connectivity, the internet is replete with power and closures. The internet ‘is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices’ – so Wikipedia – but that communication is selectively directed, deviated and disrupted. Regulatory designs therefore do not run across a smooth surface but a textured one. They run into obstacles. They get trapped in folds. Their spread is neither linear nor unidirectional. Rather, regulatory ripples diffract and generate novel patterns, transforming the marks left on situated digital infrastructures. Thinking in terms of ripples helpfully directs attention to such complex processes. Barad uses ripples as ‘a familiar example’ to explain ‘the diffraction or interference pattern that water waves make when they rush through an opening in a breakwater or when stones are dropped in a pond and the ripples overlap’ (Citation2007, p. 28). She insists on the place of discontinuity and disconnect in these diffraction patterns (Citation2014). She therefore points out that ‘ripple tanks’ are central for understanding wave phenomena in physics (Citation2007, p. 77). Although, we have no ripple tanks to observe the movement of regulatory designs across infrastructures, using ripples is a way of retaining attention to the diffraction of regulatory designs and the varied marks they therefore leave on digital infrastructures. As suggested in the context of migration politics, this helps displace the image of regulation associated with ‘the sure-footed, secure post-Westphalian nation-state’. Instead of ‘a system of clear hierarchies and often uni-directional processes with straightforward feedback loops as checks and balances’ we see regulation as ‘a world of transaction and exchange between ‘organisms’ [that] involves highly febrile ripples and folds’ (Tazreiter, Citation2015, p. 110).

The three concepts just introduced – infrastructures, regulatory designs and ripples – offer us the theoretical thinking tools needed to trace the extension of the RSS into the digital and assess its effects. Working with these concepts shifts the analysis of the RSS, attuning it to the materially entangled, the affective, atmospheric and the nonlinear movements through which the RSS generates unintended consequences well beyond the EU. It draws attention to the ripples of regulatory redesign sent through socio-material infrastructures. We refer to tools rather than ‘frameworks’ because tools are helpful in carving out and ‘composing’ representations situated in time and space. In the tradition of compositional methodology (Leander, Citation2020; Lury, Citation2020), we see no reason to assume that these representations should fit a single common ‘frame’. Rather, aspiring to ‘frame’ is potentially nefarious. It distorts and obliterates that which exceeds the frame. We therefore start with tools that are open about the compositions we make with them and allow us to frame them in different framings. More strongly, we have no reason to assume that this would be the only way of exploring the RSS and its implications beyond Europe. On the contrary, our tools could be modified, deployed differently or altogether different tools complement them. Altogether different tools might be deployed to problematize the RSS and its effects beyond the EU differently, e.g., in terms of ‘norm diffusion’ or ‘regime complexes’ (respectively Maurer, Citation2020; Nye, Citation2022). Our aim is not to disprove or discard the significance of such alternatives. Rather, it is to show − in the positive − that ripples of regulatory design running through infrastructures helps us understand and so better work with the specific problem posed by the political effect of the RSS beyond the EU.

In sum, we will work with the three conceptual tools just introduced (infrastructures, regulatory design and ripples) to trace the extension of the RSS into the digital, compose an image of how it operates and with what political consequences. We do not claim that this is the only way of ‘problematizing’ the extension of the RSS. The processes we focus on or the politics connected to them are not the only ones that matter. The arguments derived from our case are not empirically generalizable. Rather, our aims and claims are more modest. We show the political significance of the processes our tools help us problematize. We add a dimension of politics left aside by alternative tools and cut off by the sharp borders of theoretical frames. We connect European Studies – studies of the RSS specifically – and new materialism, media-studies and studies of democracy in the Global South. To realize this triple ambition, we will now focus on one situated instance of the extension of the RSS into the digital: the GDPR and one specific connection to political process in the Global South: the connection to the role of Facebook’s data protection regulation in the 2018 presidential elections in Brazil.

The GDPR extending the RSS to the digital

The EU has been extending and intensifying its regulatory reach into the digital through a range of measures. Even focusing narrowly on security related measures, discussing this extension in general and abstract terms would be impossible and misleading. We therefore look closely at just one specific and particularly significant instance of this extension: the development of EU regulation intended to secure and protect EU citizens from the misuse and abuse of their data. This extension began with the Data Protection Directive (1995), the 2000 E-commerce Directive, and a range of judgements interpreting these directives including centrally Google v Spain (2014) that posits the ‘right to be forgotten’. It culminates in the adoption of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2016. The GDPR entered into force on 24 May 2018, which sent ripples through digital infrastructures that ran into the October 2018 Brazilian presidential elections. We return to these connections below. However, first something about how the GDPR came to send ripples of redesign through digital infrastructures.

Elaborating the GDPR, the EU regulators were adopting a novel approach to regulation. They were shifting the focus ‘from policy to engineering’ as an ENISAFootnote5 paper outlining the approach informing the GDPR proposal explains:

The privacy-by-design approach, i.e., that data protection safeguards should be built into products and services from the earliest stage of development, has been addressed by the European Commission in their proposal for a General Data Protection Regulation. This proposal … would oblige those entities responsible for processing of personal data to implement appropriate technical and organizational measures and procedures both at the time of the determination of the means of processing and at the time of the processing itself. (ENISA, Citation2015, p. 5)

The General Data Protection Regulation aimed to cover a range of diverse privacy issues. It had become increasingly clear that they were all in different and partly interrelated ways connected to the design of digital infrastructures. Briefly, they were concerned with the protection of data stored that could be hacked, leaked or otherwise abused at the detriment of the EU citizens and that had been the core ambition of the 1995 Data Protection Directive regulating the processing of personal data in the EU. Second, regulators were also concerned with data generated. The clicking, viewing and posting provides data about preferences, networks and activities. Infrastructures organize these activities and the extraction of value from the ‘digital labour’ they entail (Fuchs, Citation2014; Van Dijck, Citation2009). They therefore also define the possibilities of (ab)using this data. The E-commerce Directive (adopted 2000) intended to facilitate the development of ‘information society services’ had been a stepping stone for regulation in this area. It focussed on ‘caching’, that is, on how data generated in online activities was processed. Finally, the GDPR integrated the focus on the storing, handling, generating and processing of data with a focus on data circulating. It provided regulators with a say over how personal data stored and generated in digital infrastructures fed into the digital circulation of information. It targeted advertising and the structuring of connections and relationships such as that involved when Google’s algorithms direct us, based on our previous searches, to specific pages or when Facebook’s algorithms feed us with advertising based on activities on the platform (Bucher, Citation2018). With the GDPR, EU regulators were aiming at all three aspects of data protection: its storage, processing and circulation.

The pervasive prompts to accept ‘cookies’ are the tangible demonstration of the extent to which this extension of the RSS worked and indeed achieved a redesign of infrastructures. The GDPR elicited what commentators have discussed as a ‘compliance-by-infrastructure’ (Spindler & Schmechel, Citation2016). EU regulators could not possibly have imposed or even negotiated the details of this GDPR-prompted redesign. Indeed, at the core of regulation by ‘design’ is the idea that in an environment that is not only exceedingly complex but also constantly shifting, it must be left to ‘privacy engineers’ to define the details of the regulation. As a consequence, the idea of ‘privacy by design’ informing the GDPR.

is neither a collection of mere general principles nor can it be reduced to the implementation of PETs [Privacy Enhancing Technologies]. In fact, it is a process involving various technological and organisational components, which implement privacy and data protection principles. These principles and requirements are often derived from law, even though they are often underspecified in the legal sources … the upcoming European General Data Protection Regulation provides useful indications with regard to objectives and evaluations of a privacy-by-design process, including data protection impact assessment, accountability and privacy seals. (ENISA, Citation2015, p. 7 emphasis added)

Consequently, the GDPR took the shape of five general, abstract, ‘principles’ to be adapted in context.Footnote6 These principles were elaborated in the 99 articles of the GDPR. The responsibility for implementing these principles and making them workable in context was with the organizations involved who were differentiated into two categories at the core of the GDPR: those controlling and those processing data. With GDPR came a radical increase in ‘intermediary liability’ (Keller, Citation2018).Footnote7 The GDPR was to cover data of EU citizens and their online activities generally (article 3). Regulation remained ambiguous regarding how far this would extend EU jurisdiction. However, it was potentially applicable everywhere on the internet (Ryngaert & Taylor, Citation2020; Safari, Citation2016). Fines of up to 4 per cent of global turnover were a good reason for Online Service Providers (OSP) to take that potential seriously.

For each ambiguity in the GDPR, there are clear incentives for OSPs to err on the side of protecting the requester's data protection rights, rather than other Internet users’ expression rights. A brief review of the GDPR will tell companies that they face fines as high as twenty million euros, easily dwarfing the risk from most legal takedown demands, including the Euro 130,000 ($150,000) potentially at stake for U.S. DMCA [Digital Millennium Copyright Act] copyright removals. (Keller, Citation2018, p. 321)

The OSPs did act. ‘Google spent over 8 million Euros lobbying the EU in 2018. Facebook spent over 3.5 million Euros (Amnesty International, Citation2019, p. 49). Their concerns were justified. The GDPR opened opportunities for ‘strategic litigation’ by internet activists. By way of example, Max Schrems announced four complaints against Facebook already on 25 May 2018, the day it became enforceable, and has continued to litigate since then (Lomas, Citation2018). Schrem’s organization NOYB – None Of Your Business – has continuously hired GDPR lawyers and is still doing so at the time of writing.Footnote8

The incentive ‘to err on the side of protecting’ led to a far-reaching adjustment of personal data protection practices. Opening a symposium in the American Journal of International Law, de Búrca comments:

It is rare that a lengthy and detailed piece of legislation [the GDPR] adopted in one jurisdiction becomes not only a law with powerful impact across multiple jurisdictions and continents, but also an acronym that trips readily off the tongue of laypeople and lawyers alike around the world. (de Búrca, Citation2020, p. 1)

Facebook, that we focus on below, had not made any ‘radical changes’ to comply with GDPR according to Mark Zuckerberg. However, he also assured that:

We have been rolling out the GDPR flows for a number of weeks now in order to make sure that we were doing this in a good way and that we could take into account everyone’s feedback before the May 25 [2018] deadline. (cited in Lomas, Citation2018)

The GDPR sent a decentralized capillary wave of regulatory redesign transforming digital infrastructures. This wave broke into and interfered with a specific context replete with pressures on OSPs to undertake broad overarching changes in their approaches to monitoring and regulating data. The GDPR became effective 24 May 2018, the US CLOUD Act [Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act] on 23 March 2018 (Daskal, Citation2018). It regulated the access of US authorities to personal data stored in ‘clouds’ (on servers abroad) and came with more general provisions about personal data management. Moreover, the Cambridge Analytica ‘data scandal’ broke out in early March 2018 (Hinds et al., Citation2020). At its core was the (mis-)handling of the personal data that was mined, misappropriated, brokered and analyzed for strategic communication in electoral processes clearly signalling that the standards of OSP data protection were too lose and that this was integral to their ‘business model’. Finally, it had become amply clear that the platforms were implicated with extremely problematic hate speech and disinformation as e.g., in the 2015 European Parliament Elections, the 2016 Brexit referendum, or the 2018 Rohingya massacres in Myanmar. The ripples of the GDPR were intensifying the already prevailing pressure on OSPs to give their treatment of personal data a major overhaul. In addition to ensuring compliance with specific provisions of the European regulation, OSPs were therefore elaborating explicit and transparent overarching strategies and practices for dealing with personal data.

Facebook proceeded to bolster its ‘Global Community Standards’. In April 2018, it made its ‘Internal Enforcement Guidelines’ public and created an ‘appeal process’ (Bickert, Citation2018). On 2 May 2018, Facebook added to this by announcing that it would be relying on ‘advances in technology, including in artificial intelligence, machine learning and computer vision’ to ‘remove bad content faster [and] get to more content’. According to Facebook none of this was radically new. It was merely a matter of ‘making public’ (Rosen, Citation2018). What Facebook was ‘making public’ though was, among other things, that it was accepting the spirit of a ‘right to explanation’ and the requirements of ‘due diligence’ required by the GDPR (Goodman & Flaxman, Citation2017).Footnote9 Facebook was adjusting to the regulatory responsibility intermediary liability bestowed on it, redesigning its practices of content moderation accordingly. Facebook’s ‘community standards’ were becoming part of a regulatory framework complete with deliberation, enforcement and complaint mechanisms. In November 2018, Facebook announced the creation of an Oversight Board to oversee the development and disputes related to this process that Mark Zuckerberg referred to as a ‘Supreme Court’ (cited in Douek, Citation2019, p. 3). These standards were applicable to the entire ‘community’. The regulation was designed into the platform infrastructure.

The redesign of Facebook’s regulatory infrastructure is situated and specific. However, the context in which it emerged was not. Other OSPs were also adjusting in ways that suited to their activities (Keller, Citation2018). The extension of the GDPR was intensifying the pressures generating situated redesigns of digital infrastructures through the intermediary liability it created. The ripples ran far and fast reinforcing other pressures to redesign regulatory infrastructures. The regulators’ affirmation of the EU, public, say over data to ensure the protection of EU citizens and their data was reconfiguring digital infrastructures globally. OSPs adjusted their activities to them, as did Facebook; each in their unique way. Whether or not the resulting regulatory redesign of infrastructures corresponded to the EU regulators’ wishes is uncertain. What is not, is that ‘intermediary liability’ placed the OSPs in charge of giving EU data protection ambition their practical shape as their ‘privacy engineers’ redesigned infrastructures to implement them. In the conclusion we return to the paradox that initiatives to affirm public EU authority by extending the RSS over the − mostly US based − commercial OSPs empowered these corporations. Before this, we will trace the ripples of redesign to consider their practical import for political processes and their digital infrastructuring. We will do so, focussing on the ripples Facebook’s regulatory redesign sent into the 2018 Brazilian presidential election.

Facebook securing political processes in the Global South/Brazil 2018

WhatsApp! WhatsApp! WhatsApp! Facebook! Facebook! Facebook!

These were the words Bolsonaro supporters shouted at a journalist from Globo, the largest traditional Brazilian media conglomerate, during the inauguration ceremony of the President-elect in January 2019.Footnote10 Their chanting resonates with the centrality that these two Platforms acquired in channelling and amplifying the anti-worker’s party sentiment that ushered in the election of Jair Bolsonaro (Davis & Straubhaar, Citation2020; Evangelista & Bruno, Citation2019). To contextualize, consider that many Brazilians follow politics mainly on the internet and mainly through the apps on their phones thanks to ‘zero rating’ policies that make usage of Facebook and other social media apps free (Oms et al., Citation2019). The platforms were associated with the creation of an atmosphere that normalized a split between the ‘upstanding citizen’ and the ‘criminal’. ‘Key mottos of bolsonarism’ were ‘a good bandit is a dead bandit’ and ‘the culture of human rights is over and now it is the turn of the good humans’ (Biehl et al., Citation2021, p. 156). Such slogans reinforced symbolic and structural state violence. Human rights activists and the ‘criminals’ they protect were prime targets as were left-wing intellectuals, school teachers, racial and sexual minorities, and the homeless poor (Manso, Citation2020; Moreno, Citation2019; Mattos, Citation2019, p. 39). Politics mediated by the platforms were normalizing a rhetoric replete with political incorrectness and hatred (Mello, Citation2020). The ‘WhatsApp! WhatsApp! WhatsApp! Facebook! Facebook!’ chanting was celebrating the platforms for contributing to this atmosphere and so the victory of their candidate. Clearly, the formation of this political atmosphere is as multifaceted and complex matter as is its connection to the electoral process and outcome. We focus only on how the redesign of Facebook’s regulatory infrastructures – prompted by pressures the ripples of GDPR intensified − played into it.

The GDPR entered into force 24 May 2018. Recall the ripples this sent into digital infrastructures and the intensification of the pressures on platforms – including Facebook – to revise regulatory policies and redesign regulatory architectures. This was occurring coincidentally with the Brazilian 2018 presidential elections. The two rounds were scheduled for the 7 and 28 October 2018. Of direct significance in the Brazilian context were the decisions of Facebook to publicize ‘Global Community Standards’ and the complaint and accountability procedures associated with them in April 2018. Moreover, Facebook AI Research (FAIR) developed automated processes for recognizing violations of its community standards and deal with them more swiftly. Portuguese was the first language beyond English in which such tools were developed. In the Brazilian context, they were deployed for the first time during the Brazilian elections (Iosifidis & Nicoli, Citation2020; Rosen, Citation2018). This obviously risky experimentation was justified by the ambition to bolster and enshrine the general standards of the platform ‘even at the risk of antagonizing part of the political leaders and establishment in Brazil’ (Brandino Gonçalvez & Mota Resende, Citation2018). Facebook also deployed a range of ‘electoral tools’ including issue tabs on candidate pages, candidate info tools, vote planning tools and ad hoc fact checkers (Iosifidis & Nicoli, Citation2020). Finally, the Brazilian elections were one of the first occasions where Facebook experimented with what it termed a ‘war room’ to ‘defend democratic procedures’ (Iosifidis & Nicoli, Citation2020, p. 73). ‘Teams of experts from across the company – including from our threat intelligence, data science, software engineering, research, community operations and legal team’ joined forces to against groups self-defining as a ‘“virtual army” divided into “brigades”, “commands” and “battalions”’.Footnote11 A dashboard helped the team ‘to zero in on, say, a specific false news story in wide circulation or a spike in automated accounts being created’ to provide a ‘last line of defense’ of democratic procedure on the platform, as the Facebook responsible explained.Footnote12

This regulatory redesign resulted in a range of controversial interventions. For instance, relying on ‘automated processes’, Facebook removed a network of 196 pages and 87 files on 25 July 2018 (Facebook Serviços Online do Brasil Ltda, 2019). On 22 October 2018, it announced that it had ‘removed 68 Pages and 43 accounts associated with a Brazilian marketing group, Raposo Fernandes Associados/RFA (Facebook, Citation2018). RFA was ‘the main network of support for far-right presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro on the internet’.Footnote13 This was a forceful response reflecting Facebook’s deepening regulatory grip. However, it also reflected a lack of sensitivity to the tense Brazilian context and consequences of redesigning infrastructures and shifting practices in the midst of the elections. The risks of mistakes and manipulation of automated content removals, but especially of the rumours about them were scarcely addressed (Valente, Citation2018). Instead, Facebook consistently handled such controversy and the general critique of its implication in the Brazilian election campaign with reference to a regulatory architecture designed for a ‘global community’. The conclusion of a Facebook statement explaining the 22 October removal of pages reads:

We will continue to invest heavily in safety and security in order to keep bad actors off of our platform and ensure that people can continue to trust the connections they make on Facebook. (Facebook, Citation2018)

In the tense context, such generic references to investments in safety and security against ‘bad actors’ appeared a thin justification for taking down ‘millions of posts’ as journalists put it (Valente, Citation2018). Complaints came from the right and the altright but also from those opposing it. Beyond the political cleavages, there was concern with the partial and random way in which Facebook was handling the sensitive situation (Frenkel, Citation2018). The tension between the global design and the local context that came out in the controversy surrounding the take down of pages and closure of profiles was more general. Facebook’s regulatory redesign emerging through a pressure to improve data protection intensified by the GDPR ripples bore the imprint of this tension. Three sets of examples of this make this dynamic particularly clear.

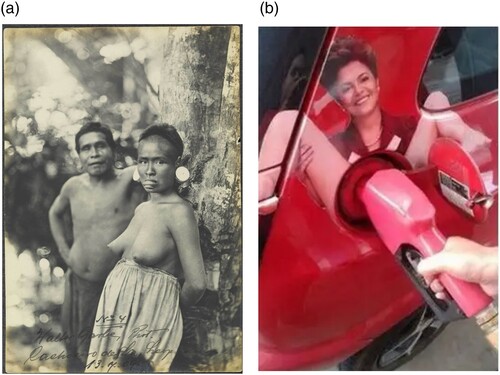

First, the issues and values prioritized by Facebook when designing an open and safe space for its ‘global community’ – and the way it interpreted them – jarred with what was significant and urgent in the Brazilian context. A good example is nudity. Facebook considers keeping nudity off the platform as essential for ensuring a safe and open online environment. In the Brazilian context, a blanket banning of nudity is highly problematic. Nudity is part of indigenous way of life and so of visualizing indigenous people and their concerns. The controversy surrounding a photo of a Botocudo Indian couple Facebook removed from the Brazilian Ministry of Culture’s page in 2015 gives a sense of the tensions this generates (). After originally arguing that the photo was not subject to Brazilian law but to Facebook community standards, Facebook shifted its position and reposted its image.Footnote14

Figure 1. Botocudo Nudity Removed/Dilma Rape Sticker Left Circulating. Botocudo Couple (1909), photographed by Walter Garbe and Image of Dilma Sticker circulating on Facebook (accessed 17 December 2022). Image assembled by Leander.

Inversely, in the election process intimations of sexual violence played a disturbing role endorsing symbolic violence and encouraging intimidation and attacks on the LGTBQI + activists, feminists, anti-racist, the left, ‘community’ activists as well as on ‘cultural Marxists’ generally. Yet, it played a limited role in Facebook’s efforts to secure a safe online environment. Logically, Facebook therefore did not remove the pictures of – and the advertising for – an obscene and violent sticker sexually abusing President Dilma to protest the ‘Lava Jato’ scandal and the rise of gasoline prices associated with it in public debate (). Despite repeated complaints, the picture still circulates on Facebook. Along similar lines, in August 2018, Bolsonaro's campaign was spreading the rumour that Fernando Haddad (Bolsonaro’s rival from the left) distributed a ‘kit gay’ teaching children homo-erotic sex in public schools when he was Minister of Education (2005-2012). This completely unfounded story became one of the most commonly shared stories (Mello, Citation2020: 176). Bolsonaro nonetheless mobilized it for his campaign promising to put an end to this (non-existing) practice. The posts and videos about the kit built on visual and verbal references to homosexuality rather than nudity (). Facebook therefore did not take action to remove any of this until the Superior Electoral Court (TSE) ordered it do so within 48 h.Footnote15

Figure 2. Post of Kit-Gay with commentary warning against Haddad. Image provided by Equipe Lupa – a ‘Hub Combatting Disinformation’ − on 19 November 2019 (accessed 17 December 2022). Screenshot by Leander.

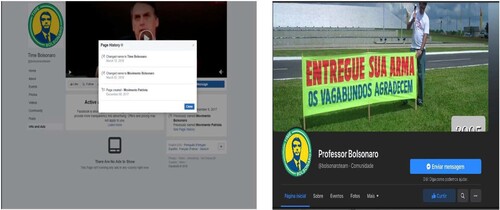

Second, when designing a safe online environment, Facebook did surprisingly little to engage with the contextual (ab-)use of the technical affordances of the platform. In spite of its ‘war-room’, the specifically developed dashboard for monitoring information and the roll out of ‘electoral technologies’ Facebook often failed to counter obvious abuse of the platform even when it was in clear breach of the community standards ruling it. In March 2018 e.g., O Globo published an article suggesting that a key right-wing group supporting Bolsonaro’s Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL) was circumventing Facebook community rules through the Application Programming Interface (API) ‘Voxer’. Voxer allowed the group to post in the accounts of other users without being identified as spamming. Facebook deactivated Voxer only after journalists sought official statements about the case. It did not remove the MBL profile entirely, but only parts of it (Shalders, Citation2018). Analogously, Facebook acted slowly – or not at all – on the many manipulations of pages and profiles that played a role in attracting supporters and spreading misinformation. For instance, with more than 350,000 likes, the page ‘Presidente Jair Bolsonaro’ was created in February 2017 as ‘Papo Lava Jato TV’, it was then renamed ‘Presidente João Doria’ and, finally given its current name. Thousands of users who had showed sympathy for Lava Jato and anti-corruption became – without prior notice – friends of Jair Bolsonaro. Facebook eventually removed this page. It left many others. Some examples: a page with 75.000 likes created in September 2013 under the name ‘Alvinegro da Vila’, a name associated to a soccer team from Rio de Janeiro is now called ‘Bolsomito Extremo’. Another profile with 66.000 likes created as ‘Zumbi Walker São Paulo’ in June 2013 is now ‘Bolsomito’. Finally, the ‘Movimento Patriota’ page set up in 2017 became ‘Team Bolsonaro’ in March of 2021 ().

Figure 3. The Movimento Patriota Morphed from Moviemento Bolsonoaro to Team Bolsonaro. Screenprints assembled by Gonzales.

Third, the redesign of the regulatory infrastructure was inspired by and premised on overarching liberal assumptions about the political and political processes that provided only a weak grip on the polarizing, illiberal, violent processes permeating the 2018 Brazilian presidential elections. Facebook sought to redesign its platform and gearing its regulatory grip to enhance and support liberal, individualistic, politics of tolerance and openness. Its community standards were designed accordingly. This meant that they were ill attuned to the issues related to the structural bias of the platform itself. It also left Facebook ill prepared to tackle the challenge of the illiberal/violent to liberalism. Its reluctance to deal with Orkut is one expression of this. Orkut started as a Google platform gathering sympathizers of the alt-right. These comprised mainly students from public universities critical of the dominance of left-wing groups and professors there. The network eventually became a hub for the most radical and violent fringes of the right in Brazil. In 2014, when Google closed Orkut, many of its communities migrated to Facebook, something Facebook seems to have tolerated to increase its penetration in developing countries including Brazil (Choudhry, Citation2018). In Brazil, these networks openly reject Facebook’s ‘real name’ policy and encourages anonymity (Severo et al., Citation2019). Their content is aggressive, violent, replete with acid humour transnationally informed and connected. In the 2018 elections, groups originating from Orkut stood for the most aggressive and violent messages that extended into physical attacks that were political, racial and homophobic in nature (de Araújo et al., Citation2021. Facebook refrained from closing down the network of pages and profiles of these radical groups with reference to its community standards. On 9 August 2018, Facebook director of policy explained that while the platform was firm in refusing ‘content that could physically endanger people’ or ‘that intimidates them through hateful language’, it would tend to err on the side of caution when facing ‘hard questions’ regarding freedom of speech. In his words:

every policy we have is grounded in three core principles: giving people a voice, keeping people safe, and treating people equitably. The frustrations we hear about our policies – outside and internally as well – come from the inevitable tension between these three principles. (Allan, Citation2018)

In the Brazilian context, the global answers given by Facebook to the ‘hard questions’ and the regulatory designs derived from them were inadequate consider the silencing, violence and inequities many associated with the platform. The flourishing of alt-right groups originating from Orkut on Facebook, the manipulation of profile names, the abuse of APIs and the sense of disjuncture between local issues of concern and a globally defined prioritization of values made regulation by the platform seem misguided at best.

The ripples generated by the GDRP in digital infrastructures were intensifying the pressures to better protect data. We have discussed the connection between the resulting regulatory architectures and political processes in the Global South by looking closely at Facebook’s implication in the 2018 Brazilian presidential elections. As our discussion has underscored, this implication bore marks of a tension between global overarching regulatory designs on the one hand and local processes on the other that made them not only ineffective and misguided but de facto also operating to skew the platform towards the alt-right. Clarifying, why exactly Facebook was not more sensitive to the context in redesigning its regulation is not the focus of this article. The reasons are no doubt composite and complex. Perhaps, as other platforms, Facebook considered Brazil ‘insignificant’ and used it as a ‘laboratory’? (respectively Couldry & Mejias, Citation2019; Fejerskov, Citation2017). Perhaps it shares the general inclination of platforms to neglect that context matters and that codes and standards need adjusting accordingly? Perhaps Facebook Brazil employees – many of whom have US degrees and share a liberal culture and politics – have no say over general polices or hesitate draw attention to their inadequacies as they care for promotions or are ‘brainwashed into the company culture’ (Interview, Citation2021)? Be this as it may. Our focus has been on the ripples connecting these problematic regulatory designs and the GDPR via the intensified contextual pressure to regulate.

Conclusion: return ripples

We have drawn the connection from the RSS extending into the digital to the WhatsApp! WhatsApp! Facebook! Facebook!’ chanting of the victorious Brazilian alt-right in 2018. We have traced the ripples the GDPR sent into regulatory infrastructures and the diffraction and interference through which they intensified pressures on platforms to better protect data. We argued that this pressure forms the context both of Facebook’s redesign of regulatory architectures and for the tension between global design and local context that marked its implication in the victory of Jair Bolsonaro. Beyond our specific claims about the connections between the GDPR and the 2018 Brazilian elections, this article has pursued a general argument, namely that the way the RSS develops has implications beyond the EU that are ill-understood through a focus on the interests, intentions and strategies of EU regulators. Instead, we have anchored our exploration of the RSS in approaches focussing on relational processes, materiality, infrastructures and the power imbued in them and used this anchoring to underscore the pertinence of such approaches for problematizing and analyzing the RSS. Contributing to such approaches in the specific area regulating data security, we also proposed three conceptual tools – infrastructures, regulatory design and ripples – for exploring the connections between the RSS and the rest of the world. Thus, even if our argument has demonstrated the significance of such politics in a very specific case, its theoretical and conceptual purchase is wider.

If the RSS is connected to processes beyond the EU, what are the implications for the EU? The ripples running from the RSS to Brazil return. The ripples of the GDPR played into the Brazilian context in a manner that undermines the ambitions and intentions not only of Facebook but also of the EU. It undercuts the ‘positive and human-centered digital agenda’ Margrethe Vestager locates at the core of EU’s digital decade and the democratic, progressive, ambitions that EU defends more generally. The ripples also return from Brazil to the EU in slightly more complicated ways. Alt-right strategies for manipulating and repurposing platform affordances and circumventing their regulations in Brazil spread and are imitated elsewhere. They send ‘return ripples’ to EU and beyond. So do the inflections such alt-right strategies give regulatory infrastructural designs. The critique of Facebook’s implication in the Brazilian elections has played into the revisiting and reworking of existing regulatory designs. It also plays into emerging regulatory practices such as those connected to the ‘oversight board’ founded 1 July 2018 (Douek, Citation2019). Ironically, the extension of the RSS into the digital, aimed at affirming EU regulatory authority affirmed the centrality of market actors and their role in designing regulatory priorities. Exploring the RSS in context is therefore crucial not only for those concerned with its implications elsewhere (e.g., Brazil) or for those who care about the EU and its political priorities but also for those who wish to grasp the role and implications of the RSS narrowly and specifically defined as it is in this special issue.

Finally, at the core of our argument is the claim that the connections between the RSS and the Global South are practical: epistemic and material at the same time. The connections are designed into infrastructures operated by corporations such as Facebook. They emerge and scale as part of intensifying pressures and forces. They are non-linear and complex. They exceed the strategies and control of RSS regulators. Assigning individualized moral responsibility to EU regulators and demanding accountability therefore makes little sense. However, at the same time the connections are uneven and hierarchical and of considerable political significance. Therefore, it is important that we continue probing them critically. It is also reasonable to expect those involved ─ EU regulators, Facebook and internet activists ─ to pursue ethical strategies that not only acknowledge the connections but demonstrate enough care and concern to work with them to limit their inequity and violence.

Acknowledgements

We owe gratitude to the guest-editors of this Special Issue for their constructive and careful engagement through this process. Thanks also to three anonymous reviewers and to Kaija Schilde for their close reading and constructive comments on earlier versions. We also wish to acknowledge the enthusiasm and motivation we have gained through our longstanding collaboration with Deval Desai and Florian Hoffmann on the project Infrastructuring Democracy: The Regulatory Politics of Digital Code, Content, and Circulation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As reflected in this special issue (see Bode & Huelss, Citation2023; Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Mügge, Citation2023; Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023).

2 Many prominent scholars have high hopes regarding European intervention and regulation including Stiegler (Citation2019), van Dijck (Citation2019) or Floridi (Citation2018). The contributions to this special cited in the previous note all complicate this enthusiasm by emphasizing the problematic implications of the ways in which the EU and its institutions are constituting its expertise and regulation.

3 https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_983 accessed 17 August 2021.

4 https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_983 accessed 17 August 2021 (emphasis added),

5 For a more detailed discussion of the role of ENISA in the RSS (see Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023),

6 They lawfulness, fairness and transparency; purpose limitation; data minimisation; accuracy; storage limitation; integrity and confidentiality (security) as summarized in article 5 of the directive (https://gdpr-info.eu/art-5-gdpr/).

7 The GDPR distinguishes between those ‘controlling’ and those ‘processing’ data but makes the controller responsible for only relying on processors who live up to the standards.

8 https://noyb.eu/en/noyb-hiring-gdpr-lawyers-and-full-stack-developers (accessed 25 September 2021),

9 Article 71 deals with the right to explanation and the centrality of due diligence pervasive and captured by the 32 mentions of ‘due’ and ‘undue’ in the regulation text.

11 (Evangelista & Bruno, Citation2019) and https://about.fb.com/news/2018/10/war-room/. We thank one of our reviewers for suggesting that we discuss the war rooms.

References

- Akrich, M. (1992). The de-scription of technical objects. In W. Bijker, & J. Law (Eds.), Shaping technology/building society: Studies in sociotechnical change (pp. 205–224). The MIT Press.

- Allan, R. (2018). Hard questions: Where do we draw the line on free expression? Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2018/08/hard-questions-free-expression/.

- Aradau, C. (2010). Security that matters: Critical infrastructure and objects of protection. Security Dialogue, 41(5), 491–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010610382687

- Aradau, C., & Blanke, T. (2018). Governing others: Anomaly and the algorithmic subject of security. European Journal of International Security, 3(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2017.14

- Arvidsson, A. (2019). Changemakers: The industrious future of the digital economy. Wiley.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe half-way: Quantum physics and the entangelment of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. (2014). Diffracting diffraction: Cutting together-apart. Parallax, 20(3), 168–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2014.927623

- Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

- Bickert, M. (2018, April 24). Publishing Our Internal Enforcement Guidelines and Expanding Our Appeals Process. About Facebook.

- Biehl, J., Prates, L E, & Amon, J. J. (2021). Supreme Court V. necropolitics: The chaotic judicialization of covid-19 in Brazil. Health and Human Rights, 23(1), 151.

- Bode, I., & Huelss, H. (2023). Constructing expertise: The front- and back-door regulation of AI’s military applications in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1230–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174169

- Brandino Gonçalvez, G., & Mota Resende, S. (2018). Facebook Retira Rede De Páginas E Perfis Do Ar E Atinge MBL. Folha de Sao Paulo.

- Bratton, B. (2016). The stack: On software and sovereignty. MIT press.

- Bucher, T. (2018). If … then: Algorithmic power and politics. Oxford University Press.

- Choudhury, N. (2018). The globalization of Facebook: Facebook’s penetration in developed and developing countries. In Media and Power in International Contexts: Perspectives on Agency and Identity. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Chun, W. (2008). On "sourcery," or code as fetish. Configurations, 16(3), 299–324. https://doi.org/10.1353/con.0.0064

- Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. (2019). Data colonialism: Rethinking big data’s relation to the contemporary subject. Television & New Media, 20(4), 336–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476418796632

- Daskal, J. (2018). Microsoft Ireland, the CLOUD Act, and international lawmaking 2.0. Stanford Law Review Online, 71, 9. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page? handle=hein.journals/slro71&div=3&g_sent=1&casa_token=Gl_ngZfkxIIAAAAA:cfg_lqxcAXLBamnHuT59g1c0kkhYxoBq5eBzfmqAbI06bg7PZdAEf3ECxxW7LKreyw53UjQSXg&collection=journals

- Davis, S., & Straubhaar, J. (2020). Producing antipetismo: Media activism and the rise of the radical, nationalist right in contemporary Brazil. International Communication Gazette, 82(1), 82–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048519880731

- De Araújo, M., Rocha, E., De Oliveira, J., De Araújo, K., Da Silva, M., De Ponte, N., De Oliveira, T., Barbosa, D., Alves, P., & De Santos, J. (2021). Fake news knowledge profile in Brazil during the covid-19 pandemic. Research, Society and Development, 10(14), e292101422085.

- de Búrca, G. (2020). Introduction to the symposium on the GDPR and international Law. American Journal of International Law, 114(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1017/ajil.2019.70

- DeNardis, L., & Musiani, F. (2016). Governance by infrastructure. In F. Musiani, D. L. Cogburn, L. DeNardis, & N. S. Levinson (Eds.), The turn to infrastructure in internet governance (pp. 3–24). Springer.

- Douek, E. (2019). Facebook's oversight board: Move fast with stable infrastructure and humility. North Carolina Journal Of Law & Technology, 21(1), 1–78. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/ncjl21&div=5&g_sent=1&casa_token=wSuij7fJh9UAAAAA:gUQvUjWjy6fCHLn0KeFpCqz22Sb3323oxkP_RlnQxtC8604ZiG_S-Sxr9P4xkg-SFHUk6evBkQ&collection=journals

- Dunn Cavelty, M., & Smeets, M. (2023). Regulatory cybersecurity governance in the making: The formation of ENISA and its struggle for epistemic authority. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1330–1352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2173274

- Easterling, K. (2012). We will be making active form. Architectural Design, 82(5), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1461

- Elbe, S. (2022, March 10). Viral infrastructures: emergency operations centres, site ontology and prefigurative power. Colloquium in International Relations and Political Science.

- ENISA. (2015). Privacy and data protection by design – from policy to engineering. https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/privacy-and-data-protection-by-design.

- Evangelista, R., & Bruno, F. (2019). Whatsapp and political instability in Brazil: Targeted messages and political radicalisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1434

- Facebook. (2018). Removing spam and inauthentic activity from Facebook in Brazil. About Facebook.

- Facebook. (2019, October 9). Statement addressed to Mixed Parliamentary Commission.

- Fejerskov, A. M. (2017). The new technopolitics of development and the global south as a laboratory of technological experimentation. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 42(5), 947–968. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243917709934

- Floridi, L. (2018). Soft ethics and the governance of the digital. Philosophy & Technology, 31(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-018-0303-9

- Frenkel, S. (2018, May 15). Facebook says it deleted 865 million posts, mostly spam. The New York Times.

- Fuchs, C. (2014). Theorising and analysing digital labour: From global value chains to modes of production. The Political Economy of Communication, 1(2), 3–27. http://www.polecom.org/index.php/polecom/article/view/19/175

- Fuller, M., & Goffey, A. (2012). Digital infrastructures and the machinery of topological abstraction. Theory, Culture & Society, 29(4-5), 311–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276412450466

- Gillespie, T. (2018). Platforms are not intermediaries. Georgetown Law Technology Review, 2, 198–216. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/gtltr2&div=19&g_sent=1&casa_token=&collection=journals

- Goodman, B., & Flaxman, S. (2017). European union regulations on algorithmic decision-making and a “right to explanation”. AI Magazine, 38(3), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v38i3.2741

- Hinds, J., Williams, E. J., & Joinson, A. N. (2020). “It wouldn't happen to me”: Privacy concerns and perspectives following the Cambridge analytica scandal. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 143, 102498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102498

- Iglesias Keller, C. (2020). Policy by judicialisation: The institutional framework for intermediary liability in brazil. International Review of Law, Computers and Technology, 1–19.

- Interview. (2021, December 6). Anna Leander interviewing professor of law with specialization in internet regulation. Zoom.

- Iosifidis, P., & Nicoli, N. (2020). The battle to end fake news: A qualitative content analysis of Facebook announcements on how it combats disinformation. International Communication Gazette, 82(1), 60–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048519880729

- Irion, K., Burri, M., Kolk, A., & Milan, S. (2021). Governing “European values” inside data flows: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Internet Policy Review, 10(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.14763/2021.3.1582

- Johns, F., & Compton, C. (2022). Data jurisdictions and rival regimes of algorithmic regulation. Regulation & Governance, 16(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12296

- Keller, D. (2018). The right tools: Europe's intermediary liability laws and the EU 2016 general data protection regulation. Berkeley Tech. LJ, 33(2), 287–364. https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38639K53J.

- Knorr-Cetina, K. (1997). Sociality with objects: Social relations in postsocial knoweldge societies. Theory, Culture & Society, 14(4), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327697014004001

- Kruck, A., & Weiss, M. (2023). The regulatory security state in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1205–1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2172061

- Leander, A. (2020). Composing collaborationist collages about commercial security. Political Anthropological Research on International Social Sciences, 1(1), 73–109. https://doi.org/10.1163/25903276-bja10004

- Leander, A. (2021a). Locating (new) materialist characters and processes in a theory global governance. International Theory, 13(1), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175297192000041X

- Leander, A. (2021b). Parsing pegasus: An infrastructural approach to the relationship between technology and Swiss security politics. Swiss Political Science Review, 27(1), 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12441

- Lessig, L. (2009). Code: And other laws of cyberspace. ReadHowYouWant.com.

- Lomas, N. (2018). Facebook, Google face first GDPR complaints over ‘forced consent’. Tech Crunch..

- Lury, C. (2020). Problem spaces: How and why methodology matters. Wiley.

- Manning, E., & Massumi, B. (2014). Thought in the act: Passages in the ecology of experience. University of Minnesota Press.

- Manso, B. (2020). República das milícias: Dos esquadrões da morte à era Bolsonaro. Todavia.

- Mattos, R. (2019). A mobilização política através de vídeos do youtube e facebook: uma análise do Movimento Brasil Livre. Universidade Federal Fluminense.

- Maurer, T. (2020). A dose of realism: The contestation and politics of cyber norms. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 12(2), 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40803-019-00129-8

- Mello, P. C. (2020). A Máquina Do Ódio: Notas De Uma Repórter Sobre Fake News E Violência Digital. Companhia das Letras.

- Monsees, L., Liebetrau, T., Austin, J., Burgess, P., Leander, A., & Srivastava, S. (2023). Transversal politics of big tech. International Political Sociology, 17(1). https://academic.oup.com/ips/article/17/1/olac020/6969127

- Moreno, T. C. (2019). Uma análise da mobilização do movimento brasil livre no Facebook contra as agências de fact-checking lupa, aos fatos e o truco. Universidade do Porto.

- Mügge, D. (2023). The securitization of the EU’s digital tech regulation. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1431–1446. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2171090

- Nye, J. J. (2022). The end of cyber-anarchy?: How to build a new digital order. Foreign Affairs (council. on Foreign Relations), 101(1), 32–42.

- Obendiek, A., & Seidl, T. (2023). The (False) promise of solutionism: Ideational business power and the construction of epistemic authority in digital security governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1305–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2172060

- Oms, J., Moyses, D., Torres, L., & Simão, B. (2019). Acesso móvel à internet: franquia de dados e bloqueio do acesso dos consumidores. Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa do Consumidor.

- Pelizza, A., & Aradau, C. (2023). The scripts of security: Agential boundaries, power asymmetries, obduracy. Science Technology & Human Values.

- Peters, J. D. (2015). The marvelous clouds: Toward a philosophy of elemental media. University of Chicago Press.

- Ribes, D., & Vertesi, J. (2019). Digitalsts: A field guide for science and technology studies. Princeton University Press.

- Rommetveit, K., & van Dijk, N. (2022). Privacy engineering and the techno-regulatory imaginary. Social Studies of Science, 56, 853–877. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063127221119424.

- Rosen, G. (2018, February 5). Using Technology to Remove the Bad Stuff Before It's Even Reported. About Facebook.

- Ryngaert, C., & Taylor, M. (2020). The GDPR as global data protection regulation? AJIL Unbound, 114, 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/aju.2019.80

- Safari, B. A. (2016). Intangible privacy rights: How Europe's GDPR will set a new global standard for personal data protection. Seton Hall Law Review, 47(3), 809–848.

- Severo, R. G., Gonçalves, S. d. R. V., & Estrada, R. D. (2019). The diffusion network of the school without party project on Facebook and Instagram: Conservatism and reactionarism in the Brazilian conjuncture. Educação & Realidade, 44(3), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-623684073.

- Shalders, A. (2018, July 25). Após Remoção Do Facebook, Cúpula Do Mbl Troca Whatsapp Por Telegram E Prepara Ofensiva. BBC News Brasil.

- Spindler, G., & Schmechel, P. (2016). Personal data and encryption in the European general data protection regulation. Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology & Electronic Commerce Law, 7, 163–177. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/jipitec7&div=18&g_sent=1&casa_token=&collection=journals

- Star, S. L. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(3), 377–391.

- Starosielski, N. (2015). Fixed flow: Undersea cables as media infrastructure. In C. R. Acland, P. Dourish, S. Harris, J. Holt, S. Mattern, T. Miller, C. Sandvig, J. Sterne, H. Tawil-Souri, & P. Vonderau (Eds.), Signal traffic: Critical studies of media infrastructures (pp. 53–70). University of Illinois Press.

- Stiegler, B. (2019). The age of disruption: Technology and madness in computational capitalism. Polity.

- Strathern, M. (2018). Infrastructures in and of ethnography. Anuac, 7(2), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.7340/anuac2239-625X-3519.

- Sullivan, G. (2022). Law, technology, and data-driven security: Infra-legalities as method assemblage. Journal of Law and Society, 49(S1), S31–S50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jols.12352.

- Tazreiter, C. (2015). Lifeboat politics in the pacific: Affect and the ripples and shimmers of a migrant saturated future. Emotion, Space & Society, 16, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2015.04.002

- Valente, J. (2018). Facebook remove 2,5 milhões de posts com discurso de ódio em 6 meses. Agência Brasil.

- Van Dijck, J. (2009). Users like you? Theorizing agency in user-generated content. Media, Culture & Society, 31(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443708098245

- van Dijck, J. (2019). Guarding public values in a connective world: Challenges for Europe. In O. Boyd-Barrett, & T. Mirrlees (Eds.), Media imperialism: Continuity and change (pp. 175–186). Rowmann & Littlefield.

- Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & De Waal, M. (2018). The platform society: Public values in a connective world. Oxford University Press.

- Vertesi, J., Ribes, D., Forlano, L., Loukissas, Y., & Cohn, M. L. (2016). Engaging, designing, and making digital systems. In The handbook of science and technology studies (pp. 169–194). MIT Press.

- Yeung, K. (2018). Algorithmic regulation: A critical interrogation. Regulation & Governance, 12(4), 505–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12158

- Zalnieriute, M., & Milan, S. (2019). Internet architecture and human rights: Beyond the human rights gap. Wiley Online Library.

- Ziewitz, M. (2016). Governing algorithms: Myth, mess, and methods. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 41(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915608948