ABSTRACT

In liberal democracies, interest groups and political parties constitute the primary organizational carriers of citizens’ preferences into the decision-making of the executive and legislative institutions. While political science research has put extensive efforts into understanding both channels of representation, their combined effect for citizen representation has only recently come into focus. In particular, we lack knowledge of the ideological alignment of citizens, parties and interest groups on overarching economic Left-Right and socio-cultural dimensions. We address this gap via an original cross-national survey of interest groups, which includes the self-placement of groups on the Left-Right and Gal-Tan dimensions. The configuration of groups on these dimensions are compared with Chapel Hill Expert Survey data on parties, and information on the preferences of citizens from the European Election Studies. Our findings indicate that interest groups have the potential to supplement multidimensional gaps in representation between the political party system and citizen preferences.

Introduction

In liberal democracies, interest groups and political parties constitute the two primary organizational carriers of citizens’ preferences into the decision-making of the executive and legislative institutions. While political parties and interest groups are linked to each other in important ways (Heaney, Citation2010, p. 568), and while these links were highlighted in early studies in the field (Schattschneider, Citation1960; Truman, Citation1951), the connections between parties and groups received, for long, relatively limited attention. Recently, research on links between interest groups and parties has had a revival. This renewed interest has been directed mainly towards organizational links between parties and interest groups (Allern & Bale, Citation2017; Allern et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Otjes & Rasmussen, Citation2017) and to some extent interest group influence on parties (Røed, Citation2022).

Although political science research has put extensive efforts into understanding the functioning and legitimacy of both channels of representation, the combined effect of the two for the representation of citizens’ preferences has only recently come into focus (Flöthe & Rasmussen, Citation2019; Giger & Klüver, Citation2016; Klüver, Citation2020). More overlooked is the question of ideological alignment between parties and interest groups, and the implications for representation. To the extent that previous literature has considered ideological alignm ent between parties and interest groups it focused on the economic Left-Right dimension, such as the link between trade unions and Left-of-center parties (Allern & Bale, Citation2017) or how NGOs and business groups align with parties on Left-Right ideology (Beyers et al., Citation2015). Closer to the focus of this article, recent scholarship has begun to investigate the relationship between proximity in policy positions and the prevalence of party-interest group ‘lobby routines’ for specific policy domains, extending beyond left-right ideology (Allern et al., Citation2022). While this indicates a burgeoning focus on socio-cultural topics within the interest group literature, what we currently lack is knowledge of the ideological alignment of citizens, parties and interest groups on the overarching economic Left-Right and the socio-cultural dimensions.

This under-emphasis of the socio-cultural ideological dimension in the interest group literature stands in sharp contrast to the significant attention it has received within the party literature. The move within party research towards studying a two-dimensional ideological space has not only brought into light the increased salience of the socio-cultural dimension in European democracies (see, e.g., Hobolt & de Vries, Citation2015; Spoon et al., Citation2014; Van de Wardt et al., Citation2014); it has also revealed that a substantial proportion of voters in today’s European democracies are left without a party that is aligned with their preferences on both the economic and socio-cultural dimensions (Lefkofridi et al., Citation2014; Thomassen, Citation2012; Van der Brug & Van Spanje, Citation2009). This lack of voter-party alignment challenges normative models of political representation, since it makes it difficult for voters to select politicians that can be expected to represent their views in the legislative and executive institutions (see Mansbridge, Citation2009). However, political parties are not the only channels through which citizen views can be represented in the political system. This raises the question whether citizens that may not all be well represented by parties can rely on the second major organizational form for preference aggregation: interest groups. Yet, there has so far been little research done on whether the interest group system has the potential to ‘compensate’ for the gaps that exist in party-voter agreement in today’s European democracies (but see Flöthe & Rasmussen, Citation2019; Klüver, Citation2020; Rasmussen & Reher, Citation2019).

This study explores the question of whether the two channels of representation – political parties and interest groups – contain similar types of ideological gaps, thus amplifying the overall incongruence in ideological positions between citizens and interest aggregators, or whether the interest group system can compensate and moderate representational weaknesses in the party system. We do so by comparing the ideological positioning of citizens, parties and interest groups on the two major conflict dimensions in European politics: economic Left-Right and ‘Gal-Tan’ (‘green/alternative/libertarian’ versus ‘traditional/authoritarian/nationalist’) dimension (Hooghe et al., Citation2002), which deals more with cultural politics (Hobolt & De Vries, Citation2015; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018; Kriesi et al., Citation2008; Rohrschneider & Whitefield, Citation2012).Footnote1 Together, these dimensions form an attitude space that encompasses major political ideological preferences of West European voters (Kriesi et al., Citation2008; Van der Brug & Van Spanje, Citation2009).

We focus on an early step in the representational process, the question of agreement between the political preferences of citizens and the ideological positions adopted by political parties and interest groups. We do so for two reasons. First, examining the positions of interest groups in terms of broad dimensions of political ideology, rather than specific policy issues, is still a rare perspective in the literature. This is particularly true for the Gal-Tan dimension, and the salience of this dimension to interest groups remains an open question. Second, citizen-party and/or citizen-group ideological agreement is either a necessary component of realizing congruence on policy output, or at a minimum should be conducive to higher levels of agreement in the latter part of the representational chain.

The study is conducted in three steps. First, we examine to what extent the two ideological dimensions are important to interest groups in their lobbying activities. As we develop below, this is no obvious matter: there are reasons why interest groups might not want to put any emphasis on ideological dimensions (which is probably one reason why this is an understudied aspect of interest groups’ work) but information about the salience of these ideological dimensions for interest groups is important for understanding the potential of the interest group system to represent citizen preferences. The same is obviously true for information about group positions on these ideological dimensions; and that is the focus of the second step in our analysis, where we compare the positions that interest groups and parties take on the two ideological dimensions. The first two steps set the stage for the final and crucial part of the analysis, where we investigate whether interest groups can compensate for representational weaknesses in party systems, or if they rather reinforce existing biases.

We make use of an original cross-national survey of interest groups in Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, Lithuania and Slovenia, which includes questions on the self-placement of groups on the Left-Right and Gal-Tan dimensions. The configuration of groups on these ideological measures are matched and compared with Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) data on parties. To assess gaps in ideological representation, we link the positions of these two types of actors to the preferences of citizens in our five countries with data from the European Election Studies (EES).

The article makes several contributions. First, it offers an analysis of the ideological alignment between parties and interest groups in contemporary European societies on the two dominant dimensions of political competition. We know of few studies that have examined the positions of interest groups on both overarching Left-Right and socio-cultural dimensions (Grande & Kriesi, Citation2012; Allern et al., Citation2022); and to the best of our knowledge, none have done so for countries outside of Western Europe, and none have addressed dimensional salience. Our article offers unique data on how the interest group populations in Eastern and Western European democracies view the salience of, and take positions on, the economic Left-Right and the Gal-Tan ideological dimensions.

In doing so, we also offer a methodological contribution. While research on interest groups as representative agents has for the most part focused on descriptive representation (where inferences are made based on interest group type) we study substantive representation. Research on descriptive representation usually differentiates between NGOs and business groups; diffuse and specific interests; producers and consumers, etc. Such categories may, indirectly, capture positions on the traditional economic Left-Right dimension, but they are unlikely to capture the Gal-Tan dimension. To understand the interest groups’ positions on both ideological scales, and the salience they attach to them, we need to study more directly the values that the interest group system represents, which is the approach we take in this article.

Finally, we offer a much-needed analysis of whether the interest group system has the potential to compensate for the gaps that exist in party-voter ideological alignment in today’s European democracies. To date, we know little about the degree to which interest group lobbying corresponds with the substantive ideological preferences of citizens throughout society, and in particular with respect to the socio-cultural ideological dimension.

Our results show that groups can indeed compensate for representational gaps in the party system by providing a package of ideological positions in the direction of representational gaps between citizens and political parties. We also show, however, that this is by no means an inevitable result of interest group activity, and there are meaningful differences between the countries we study. By considering the combined effect of the party and interest group systems, our central findings suggest that interest groups see the Gal-Tan dimension as important; take a variety of positions along this ideological continuum; and therefore have the potential to act as important supplements of political parties when it comes to the representativeness of political systems. Ultimately, the two continue to serve crucial and complementary roles as the main aggregators of citizens’ preferences in European democracies.

Representation of citizen ideological positions by parties and interest groups

Like political parties, interest groups aggregate policy preferences and bring them to the political arena. They are active and influential throughout the policy making process, from the agenda setting stage to decision making, and may thus play an important role in policy representation (Klüver, Citation2020; Lax & Phillips, Citation2012; Rasmussen & Reher, Citation2019). Lacking the formal policy making role that parties enjoy, interest groups bring policy demands into the political process in other ways. Part of their representational role is, for example, to frame issues and transform vague complaints into concrete policy responses, so that policy makers ‘receive articulate demands rather than inarticulate grievances’ (Hansen, Citation1991, p. 229), and they influence policy makers’ perceptions about citizen preferences (Eichenberger et al., Citation2022). Importantly, the implications of interest group influence on policy making for representation are not obvious: interest groups can be either ‘a blessing or a curse’ for policy congruence between citizens and policy makers (De Bruycker & Rasmussen, Citation2021; see also Eichenberger et al., Citation2022).

For the question of ideological representation, these insights imply that for a given ideological distance between citizens and parties in terms of basic preferences, interest groups may have the ability to either pull them closer, or further apart. Whether and which they do, we argue, will depend on the ideological positions that interest groups themselves bring into the policy process, and how forcefully they do this. For interest groups to be capable of filling existing gaps in the party-citizen relationship they would, in other words, need to both take positions on the overarching dimensions that structure party-based representation in Europe, and attribute salience to these dimensions.

Yet, this is no obvious matter. Parties bundle positions on a variety of political issues in a way that form cohesive, overarching ideological dimensions for a variety of reasons, not least to cut down on information costs to citizens and mobilize the electorate to vote (Aldrich, Citation1995; Layman & Carsey, Citation2002). In contrast, the electoral incentives for dimensionally-based politics are less immediately apparent for interest groups. Groups are therefore thought to focus their lobbying efforts in more specific political issue areas, and less prone to mobilize on more abstract, ideological dimensions. We argue, however, that the lesser need for ideological dimensions for electoral purposes does not mean that we should assume that they are irrelevant to interest groups. Even for single-issue groups, their particular issue will often be firmly placed on one of the ideological dimensions, and we should not expect groups to be oblivious of that. Instead, we treat this as an empirical question that so far has not been investigated. In our analysis, we explicitly decouple interest group dimensional positions from dimensional salience. Given how little we know about how interest groups’ work map on to ideological dimensions, we start with the basic question about salience and ask: are broad ideological dimensions – Left-Right and Gal-Tan – important to interest groups in their advocacy work?Footnote2

After examining the salience of political dimensions to the interest groups of European democracies, we begin to more fully explore the possibility that the interest group system can compensate for existing ideological gaps in the party system. In order to do so, we first need to know: How do interest groups position themselves in the two-dimensional ideological space, and how do their positions compare to those of parties?

By two-dimensional ideological space, we mean specifically the positions that political parties and interest groups take as summarized in overarching measures of economic and cultural politics. We highlight two features of this approach. First, our measures of ideological placement differ from the actual legislative output produced by political parties once in government, as well as the policy outcomes that flow from this legislative output. The positions we measure for parties and interest groups are akin to their ideal points on the economic and cultural dimensions of politics prior to legislative bargaining. Second, our measures explicitly decompose a more general, overall measure of political ideology, which would include both economic and cultural features in a single estimate of a party or group’s ideological position. Here, we directly examine party and group positions on the economy, with more leftist positions corresponding to a preference for an active government role in managing the economy and more right positions tapping a preference for less government regulation of economic activity. On the cultural dimension, we estimate preferences for liberal as opposed to conservative/traditional approaches to organizing and regulating society. Together, this creates a two-by-two positional space in which political actors could be: left-liberal, left-conservative, right-liberal, or right-conservative.Footnote3 This decomposition of the general ideological space into its economic and cultural dimensions is now widely recognized in both the party politics and interest group scholarship.

There are theoretical reasons to expect that the party system and the interest group system reflect the two-dimensional distribution of citizen preferences in different ways. First, when it comes to the likelihood that new parties will emerge in response to citizen preferences, there are many constraints on the effective number of parties in any system. Duverger (Citation1954) famously argued that single-member, simple-plurality electoral systems will lead to only two parties, but also in PR systems the emergence of a large number of parties is normally prevented. In fact, due to the obstacles to both the emergence and the electoral success of new parties, it has been argued that ‘the genuinely puzzling thing is why new political parties emerge and gain support at all’ (Erlingsson, Citation2009, p. 113).

One could therefore expect that party systems would respond to changing citizen preferences not always with the emergence of new parties, but rather through the repositioning of old parties on issues of salience to the public. But parties also face important constraints in their flexibility when it comes to strategic repositioning (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018; Kollman et al., Citation1992). Established parties have positions on a large number of issues. When adapting their policy platforms, parties are normally limited both in terms of the number of issue positions they can change and the degree of change that they can make on any issue (Kollman et al., Citation1992).

For interest groups, there will often be fewer constraints with respect to both their initial emergence and their ability for quick repositioning. Interest groups do not seek office and are thus not dependent on generating support from a substantial share of the electorate in order to play a meaningful role. This is most obviously reflected in the difference in the sheer number of interest groups as compared to parties (Halpin & Jordan, Citation2009). Not only are overall numbers larger, but changes in the interest group population – the emergence and decline of groups – are also more common. For these reasons, we expect that interest groups will populate a larger part of the two dimensional ideological space than will political parties, reflecting the salience of both Left-Right and Gal-Tan in contemporary European societies.

The descriptions of salience and position set the stage for the final step in our analysis which is to investigate whether the interest group system mitigates or reinforces bias. Do interest groups compensate for or reinforce gaps that exist in the citizen-party representational relationship? Early scholars of interest groups saw the emergence of groups as a more or less automatic response to concerns in the public, suggesting that interest groups serve as transmission belts between public opinion and public policy (Easton, Citation1971; Truman, Citation1951). This pluralist view was criticized by, for example, Mancur Olson who showed that due to the obstacles to collective action, a concern shared by many people is not enough for a group to emerge (Olson, Citation1965). Critics of the pluralist perspective have argued that the interest group system instead breaks the link between citizen attitudes and the political process by drawing the attention of policy makers away from the general public, making them cater to the interests of well-organized groups (Olson, Citation1965; Schattschneider, Citation1960; Schlozman et al., Citation2012).

What are the implications of these classic debates for our expectations about the ability of interest groups to compensate or reinforce representational gaps in the party system? From a pluralist perspective, we would assume that interest groups will to some extent balance the lack of parties in any specific voter groups. A significant shift in citizen preferences that is not (yet) captured by the party system would generate mobilization and new groups emerging to voice these concerns. The higher ‘birth rates’ among interest groups than among parties indicates that it is easier for interest group systems to more swiftly fill a representational void than for party systems.

The critics of the pluralist view, on the other hand, would not expect any such a compensation effect. From an olsonian or schattschnederian view on mobilization and access to resources, interest groups are unlikely to represent citizens any better than political parties. Furthermore, the literature on political participation suggests that the same kind of bias probably occurs in both parties and interest groups, with well-educated resourceful citizens dominating the membership of both types of political organizations (Persson, Citation2015; Verba et al., Citation1995) In addition, Wüest et al. (Citation2012) find that in Western Europe, the interventionist-nationalist (Left-Tan) quadrant of the political space is underpopulated in relation to citizen demand, also when including interest groups in the analysis.

To summarize, we examine three inter-related research questions related to the relationships between interest groups and political parties in the two dimensional policy space of contemporary European politics. First, we ask are the two dimensions, particularly the socio-cultural dimension, seen as important by interest groups? While groups tend to focus on more specific policy issues and interest groups have historically been most attentive to matters of economic policy-making, we expect that the rising prominence of socio-cultural topics in contemporary European societies means that many interest groups will find this dimension salient. Second, we ask what positions do interest groups take on both the Left-Right and socio-cultural Gal-Tan dimension and how do these compare with the positioning of political parties? Our expectation is that interest groups will take a fuller range of positions than do political parties. This leads directly to our third and final question, do interest groups offer the potential to reduce ideological gaps that exist between the positions of political parties and the preferences of public opinion? Here, our tentative expectation is that interest groups will through a broader coverage of the ideological space offer an alternative representational path that supplements the offering from political parties. We now turn to a description of our empirical approach to investigating these questions.

Data and methodology

When studying the representativeness of interest groups – i.e., the extent to which the interest group system represents the views of the general public – previous research has traditionally focused on the types of groups that dominate the interest group population and/or exercise influence. This corresponds to a descriptive representational perspective, where specific group types are seen as representatives of different segments of society. In contrast, scholars studying representative democracy through the electoral system have traditionally focused on the substantive representation of interests, values and opinions (see Boräng & Naurin, Citation2022). In this paper we focus on substantive representation. This means that rather than making inferences about interest representation from the prevalence of certain group types, we study directly which ideological positions interest groups and parties take, and compare their ideological ‘input’ to the political system with the views of the public.

We use the 2014 wave of the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) on party positioning in Europe to measure the positions of political parties on the economic Left-Right and Gal-Tan dimensions (Polk et al., Citation2017). Since 1999, CHES has asked political scientists specializing in party and/or European politics to place the political parties of their country of expertise on a variety of dimensions and policy issues related to economic Left-Right, socio-cultural, and European politics. These data have been subjected to extensive cross-validation exercises, combined in a single trend file covering six time points between 1999 and 2019, and are widely used in party politics research.Footnote4 We use data on the parties from 2014 in order to maximize temporal comparability with the survey of interest groups. See Appendix 2 for the wording of the questions in the expert survey.

While data on party ideology is available for all European countries, data on the ideological positions of interest groups is harder to come by. We use a recent, original cross-national survey of interest groups (Beyers et al., Citation2016, see http://www.cigsurvey.eu). The survey includes a broad range of questions about interest groups’ political activities and strategies, organizations structures, resources, etc. It also includes questions on the self-placement of groups on the Left-Right and Gal-Tan dimensions, as well as on the importance groups attach to these dimensions. The survey has been conducted in Belgium, the Netherlands, Lithuania, Slovenia and Sweden.

The fact that we have countries from both Western and Central and Eastern Europe is relevant since the relationship between the economic and the socio-cultural dimension differs between the East and the West (Marks et al., Citation2006) and although interest group research in the region is rapidly growing (see., e.g., Beyers et al., Citation2020; Dobbins & Riedel, Citation2021) we have no systematic analysis of the relationship between the ideological positioning of parties and interest groups in Eastern Europe. In addition to bridging the East/West division in studies of European politics, the party systems of these countries also feature a high effective number of parties, particularly the Western European countries. This is important because the rather large number of parties in these systems makes it more probable that they will cover a broad range of the two-dimensional ideological space compared to party systems with less parties such as the United Kingdom. This means that if we find some quadrant of a two dimensional ideological space less supplied by parties in these systems, it is also likely to be the case in other countries with a lower effective number of parties.

Our sample is a selection of small and medium-sized countries, all members of the European Union. These countries have not received the same amount of attention in interest group research compared to larger European countries. Slovenia and Lithuania have a post-communist legacy, which has been connected with comparatively weak civil society organizations (Howard, Citation2003; but see Ekiert & Kubik, Citation2017 for a less pessimistic view). Belgium, Netherlands and Sweden have traditionally been described as neo-corporatist countries with highly structured relationships between interest organizations and the state. We believe this variation increases the generalisability of our findings. However, we would caution against direct transfers of our findings to larger countries with a tradition of more pluralist (UK) or statist (France) state-interest groups relationships.

In all five countries that we include in our analysis, a comprehensive mapping of the interest group population at the national level was first conducted. For the most part, the sampling relied on bottom-up sources such as directories, registries or encyclopedias of organizations. These sources normally do not require any activity for groups to be included. In some cases, interest groups were identified by top-down sources such as government archives, for which some level of activity was necessary to be registered; however, the threshold for activity was very low (for example, sending an email to a government ministry). In all countries, the sources therefore allowed for an inclusive mapping of the interest group population, as compared to an approach where interest groups are identified through, for example, their active involvement in policy processes (Beyers et al., Citation2020). The sources used in each country are described in Appendix 1.

Interest groups are defined as non-governmental organized groups, who act with the purpose of influencing political decisions, although influencing politics does not have to be their primary purpose. This definition includes a range of groups, such as business organizations, professional associations, trade unions, idea based and identity-based NGOs. The survey was sent to all identified interest groups in each country. shows the size of the identified interest group populations and number of groups responding to the survey for each country.Footnote5

Table 1. Interest group populations and survey responses.

The questions used to measure Left-Right and Gal-Tan salience and positions for interest groups, were adapted from the CHES for use in the interest group survey. The exact question wordings can be found in Appendix 2. For the interest groups, salience was measured first in the survey. If the respondent indicated that the dimension was at least to some extent relevant to the organization the survey asked about its position.

While the questions in the party expert survey and the interest group survey were kept as similar as possible to maximize comparability, an important difference between the two is that experts provide the ideological position of parties, while the position of interest groups is based on answers from representatives of the groups themselves. While an identical coding procedure would have been ideal, expert coding of interest groups would have forced us to limit the number of groups so much that the populations would have been severely misrepresented. Moreover, we believe that the fact that interest groups are asked to reveal their own positions on these scales would, if anything, lead us to underestimate the salience of these ideological dimensions for interest groups, because of a potential desire to present themselves as non-ideological professionals willing to work across political blocs.

A key difference between political parties and interest groups is the directness with which political parties can represent the electorate in the political system. Political parties act as the primary agents of citizen principals in the chain of delegation built into parliamentary democracies (Strøm, Citation2000). Political parties in European parliamentary democracies are unique in their presence and relevance at every step this delegatory chain, from the organization and running of elections to the policy outputs flowing from the bureaucratic agencies (Müller, Citation2000). The interest group system constitutes the other main organizational carrier of citizens’ preferences into the decision-making of the executive and legislative institutions. Interest groups’ influence, however, is more indirect, and not all interest groups are equally powerful and capable of influencing policy output.

Even if we find interest groups in all four quadrants of the ideological space, this is no guarantee that groups are of sufficient size or strength to serve as meaningful aggregators of public preferences. Whether interest groups can be effective representatives or not is highly dependent on the amount of effort and resources they spend on lobbying. In our analysis, we therefore take into account the amount of lobbying activities performed by the groups, in order to assess how much each group brings into the political system. In order to create a measure of lobbying activity we asked the interest groups which lobbying tactics they were using, measuring both ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ lobbying activities, and how often they used them. We then used this information to calculate an overall measure of lobbying activity for each group. In Appendix 2, we describe the questions used to measure lobbying activity and how we calculate the overall activity measure.

To assess representativeness, we contrast the positions of parties and interest groups to those of voters in our five countries. Measuring the Gal-Tan preferences of citizens is complicated by the fact that we are not aware of any cross-national mass surveys that ask the Gal-Tan question in the same phrasing that has been used for political parties and interest groups. We therefore created an additive index from questions included in the 2014 round of the European Election Study (EES) Voter Study (Schmitt et al., Citation2015) that relate to the Gal-Tan dimension of political competition.Footnote6 These are the questions on same-sex marriage, civil liberties, and immigration. All three questions are on 11-point scales with lower values corresponding to more Gal attitudes and higher values indicating more Tan preferences.Footnote7 We created a similar additive index for economic Left-Right based on items related to: state intervention in the economy, redistribution of wealth, and the trade-off between taxes and public services. Again, all three questions are on an 11-point scale. Lower values indicate more Left-wing preferences and higher values correspond with more Right-wing attitudes.Footnote8

Findings

Before examining the research questions, we begin by examining the preferences of the public on the two main ideological dimensions.

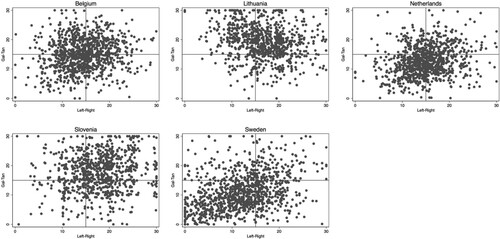

presents the constellation of Left-Right and Gal-Tan preferences for citizens in Belgium, Lithuania, Netherlands, Slovenia, and Sweden (lower values on the vertical axis represent more Gal preferences and lower values on the horizontal axis represent more Left-wing preferences). The figures reveal differences in public opinion across countries that lend some face validity to the data. For example, large numbers of Swedish and Dutch respondents (countries often associated with post-materialism) display Gal values relative to the other countries, with over 53 per cent of Swedes located in the Left-Gal quadrant. Lithuania, in particular, displays conspicuously ‘Tan’ public opinion, with well over 75 per cent of respondents in the Tan half of the two-dimensional space.Footnote9

Figure 1. Left-Right and Gal-Tan Public Opinion. Note: Self-reported Left-Right and Gal-Tan preferences of EES 2014 Voter Study respondents in Belgium, Lithuania, Netherlands, Slovenia, and Sweden. Left-Right and Gal-Tan are the additive indices of three policy questions related to each dimension described in the text.

Yet, despite differences across countries, the five panels of also clearly illustrate the presence of citizens in all four quadrants of the Left-Right, Gal-Tan preference box, which we show below stands in contrast to the positioning of political parties. For example, we find a number of survey respondents in the upper-left squares of each sub-panel, which indicate citizens with the ‘Left-authoritarian’ attitudes that previous research has found to be under-represented in the party systems of Europe (Lefkofridi et al., Citation2014; Thomassen, Citation2012; Van der Brug & Van Spanje, Citation2009). Even in the Netherlands and Sweden, over 11 per cent of respondents are within the Left-Tan quadrant, which illustrates the non-trivial number of citizens populating all four sections of the two-dimensional space.Footnote10 Next, we turn to investigating to what extent the positions of political parties and interest groups correspond to the citizen preferences.

Interest group salience and positions in the two-dimensional space

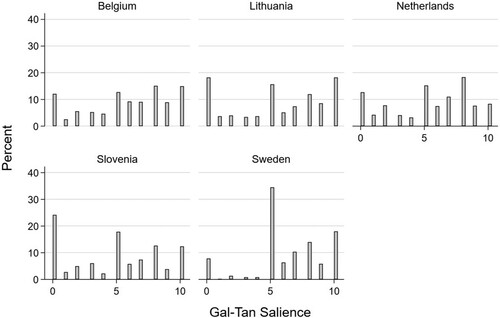

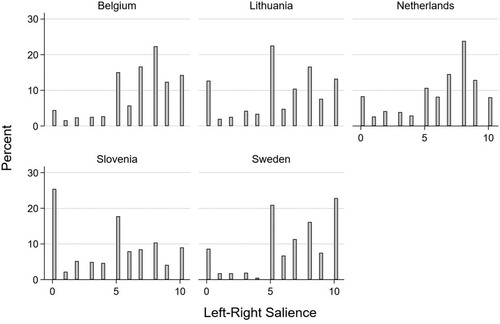

The extent to which the interest group system can represent ideological positions in their activities is dependent on groups attaching importance to the ideological dimensions we study. We therefore first need to establish whether these ideological dimensions are at all relevant to interest groups. displays, per country, the distribution of the salience that interest groups attach to the two ideological dimensions. As we can see, both dimensions are relevant for significant parts of the interest group populations in these countries. The dimensions are least salient to interest groups in Slovenia, where around 25 per cent of interest groups attach no importance (a zero on the scale from zero to ten) to both dimensions. Slovenia is also the only country in which interest groups, on average, attach more importance to the Gal-Tan dimension than the Left-Right dimension. In the other countries, a much smaller share of interest groups report that the ideological dimensions are of no importance to their advocacy work, and generally the importance they attach to both dimensions is rather high. In these four countries, the economic Left-Right dimension is seen as slightly more important to groups' advocacy work: in Sweden, over 20 per cent of groups report that the Left-Right dimension is ‘of great importance’ in their lobbying and advocacy activities. But the overall difference between the two ideological dimensions is rather small, and does not justify the relative lack of attention to the Gal-Tan dimension in interest groups research. More generally, the lack of attention to ideological dimensions in interest group research is not motivated by a lack of attention to these dimensions by interest groups themselves.

Figure 2. Salience of the ideological dimensions for interest groups. Note: ‘0’ = ‘of no importance’ and ‘10’ = ‘of great importance’.

Since shows the distribution of salience separately for the two dimensions, it is worth noting that the salience of the two dimensions is positively and significantly correlated in all five countries, with the strongest correlations in Slovenia (0.41), Lithuania (0.40) and the Netherlands (0.38) and somewhat weaker correlations in Sweden (0.27) and Belgium (0.25). For many groups, both ideological dimensions are important in their lobbying and advocacy activities (whereas negative correlations would have suggested that interest groups tend to specialize on one dimension while attaching very little significance to the other).

The groups that attached no importance at all to the ideological dimensions did not receive the questions about their position on the dimensions and are thus excluded from the analyzes that follow. Having concluded that these two ideological dimensions indeed are relevant to interest groups, we move to present a descriptive account of how parties and interest groups map onto the same two-dimensional ideological policy space. As we now move closer to the question about the representation potential of interest groups, and since their effectiveness as representative agents is highly dependent on how much advocacy work they actually do, interest groups are in the following weighted by their lobbying efforts, defined by their activity levels.

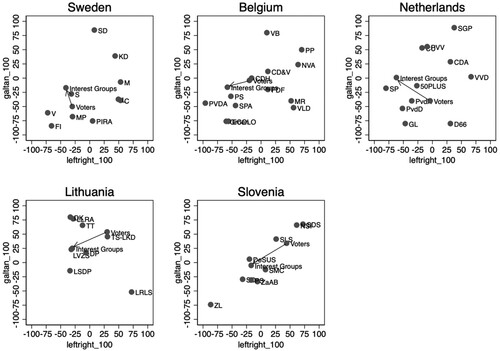

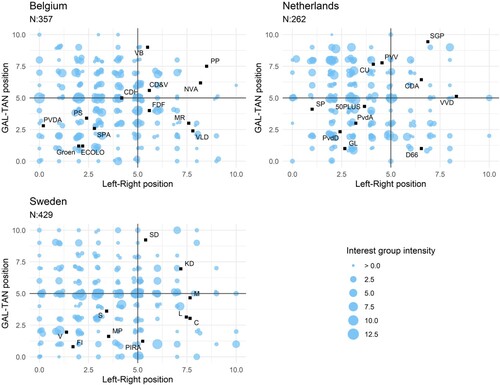

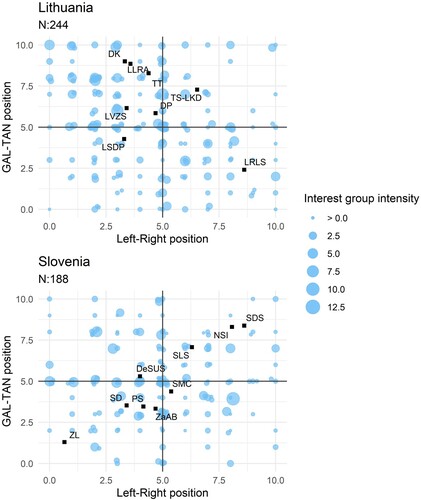

In , the parties are located in the two-dimensional space and depicted as squares, along with party name abbreviations, compared to the filled circles that represent interest groups and that vary in size depending on their number of activities per week, 12,5 being the highest observed value. A few interest groups (four to seven depending on the country) reported that they had no activity at all, and these groups are excluded from the graphs below. The scatterplots display the anticipated Left-Authoritarian gaps in the party space for the countries of Western Europe: Belgium, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Note that although two parties in the Netherlands are slightly in the Left-Authoritarian quadrant, the majority of this positional space remains unoccupied in the party systems of these countries. This stands in contrast to the distribution of the interest groups.

Figure 3. Belgian, Dutch, and Swedish Interest Groups and Political Parties. Full party names: Belgium: PS – Socialist Party, SPA – Socialist Party Different, ECOLO – Ecolo, Groen – Green, MR – Reformist Movement, VLD – Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats, CDH – Humanist Democratic Center, CD&V – Christian Democratic and Flemish, NVA – New Flemish Alliance, FDF – Francophone Democratic Federalists, VB – Flemish Interest, PVDA – Workers’ Party of Belgium, PP – People’s Party. Netherlands: CDA – Christian Democratic Appeal, PvdA – Labor Party, VVD – People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, D66 – Democrats 66, GL – GreenLeft, SGP – Political Reformed Party, SP – Socialist Party, CU – Christian Union, PVV – Party for Freedom, PvdD – Party for the Animals, 50PLUS – 50PLUS. Sweden: V – Left Party, S – Swedish Social Democratic Party, C – Center Party, L – Liberal People’s Party, M – Moderate Party, KD – Christian Democrats, MP – Environment Party – The Greens, SD – Sweden Democrats, PIRA – Pirate Party, FI – Feminist Initative.

In all three Western European countries, interest groups populate all four quadrants of two-dimensional space. Taking the Left-Tan quadrant as an example, in Belgium 21 per cent of the interest groups are located in the Left-Tan space that is unoccupied by political parties but populated by 26 per cent of Belgian EES respondents. In the Netherlands, the Left-Tan quadrant is actually overrepresented by groups relative to citizens, with 22 per cent of groups in the Left-Tan area compared to 11 per cent of citizens. Finally, in Sweden, nearly 15 per cent of groups are in the Left-Tan portion of the two-dimensional space, which is again even more than the 11 per cent of Swedish citizens. It should be recalled that these figures are based on the interest groups that answered the survey: we do not know how non-responding groups would position themselves on the two ideological dimensions and thus if their inclusion would have added more to some quadrants than others. Still, these patterns in the distribution of interest groups provide preliminary evidence that interest groups have the potential to fill representational gaps in the party systems of Western Europe. These findings are also consistent with our theoretical expectation that interest groups will more thoroughly populate the two-dimensional ideological space than political parties.

presents the two Central and Eastern European countries in our sample and shows that Lithuania and Slovenia display diverging patterns of party positioning in the two-dimensional space. Slovenia, strikingly, shows a ‘Western’ pattern in party positioning. While Left parties tend to be more Tan in many post-communist party systems (Marks et al., Citation2006), Slovenia’s parties are distributed across an almost 45-degree line from Left-Liberal to Right-Authoritarian positions. The parties align along this axis even more closely than many party systems in Western Europe (see, e.g., ), and much like those countries, also leave the Left-authoritarian quadrant empty. A slim majority of Slovenian survey respondents (just over 50 per cent) locate themselves within the Right-Tan area of the two-dimensional space, an ideological combination that is shared by three political parties. But for the nearly 17 per cent of Slovenian Left-Tan citizens, there is substantially less representation from political parties in comparison to the 11 per cent of interest groups in the Left-Tan block.

Figure 4. Lithuanian and Slovenian Interest Groups and Political Parties. Full party names: Lithuania: LSDP – Social Democratic Party of Lithuania, TS-LKD – Homeland Union – Lithuanian Christian Democrats, LVZS – Lithuanian Peasant and Greens Union, LLRA – Electoral Action of Lithuania’s Poles, TT – Order and Justice, DP – Labor Party, LRLS – Liberal Movement, DK – The Way of Courage. Slovenia: SDS – Slovenian Democratic Party, SD – Social Democrats, SLS – Slovenian People’s Party, NSI – New Slovenia-Christian People’s Party, DeSUS – Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia, SMC – Party of Miro Cerar, ZL – United Left, ZaAB – Alliance of Alenka Bratušek, PS – Positive Slovenia.

Turning to Lithuania, there are several parties in the Left-Authoritarian section of the policy space, which deviates from the patterns we note for the other countries in our analysis. However, the presence of political parties in the Left-Authoritarian quadrant is indicative of party-voter congruence and structured political spaces in Lithuania (e.g., Rohrschneider & Whitefield, Citation2012; Rovny & Polk, Citation2017). Recall that in Lithuanian citizens showed conspicuously more Tan preferences and a substantial number of respondents located themselves in the Left-Authoritarian square. It appears from the left panel of that the political parties in the country are congruent with Lithuanian voters on these matters.

It would be unwise to generalize from such a limited number of cases, but nor should the divergence between Slovenia and Lithuania come as a surprise. In the early years of Central and Eastern European countries transitions from single party communist systems, ideological leftness was strongly associated with cultural authoritarianism because of the top-down, party-led communist legacy (Marks et al., Citation2006). Yet this initial pattern of party competition in post-communist Europe, an inverse of Western Europe, with Left-Authoritarian and Right-Liberal parties, has evolved into a more complex and varied relationship between economic and cultural party positioning in these countries (Bakker et al., Citation2012; Rovny & Edwards, Citation2012). While this less uniform dimensional relationship in contemporary post-communist Europe is apparent in the differences between Slovenia and Lithuania depicted in , the cross-sectional nature of our interest group data precludes a deeper examination of over time dynamics.

With respect to the interest groups, as noted there is no shortage of groups in the Left-Authoritarian quadrant of the policy space in any of the five countries in our sample. In Western Europe, it is rather the economic right half of the policy space that is rather sparsely populated. In Belgium, the Netherlands, and Sweden, no more than 21 per cent of the group population is to the right of the Left-Right midpoint.Footnote11 Not surprisingly, there are fewer interest groups overall in Lithuania and Slovenia than there are in the EU-15 countries. Yet, the interest groups that exist cover a wide range of positions in the two-dimensional policy spaces of the newer EU member states.Footnote12

Do interest groups compensate for or reinforce gaps that exist in the citizen-party representational relationship?

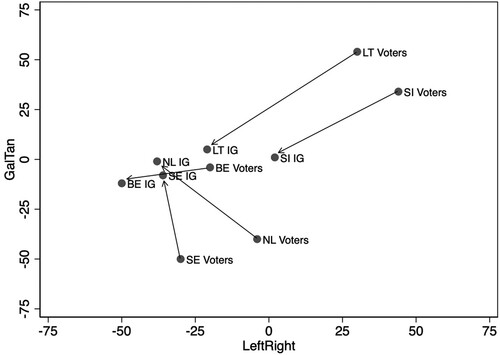

The fact that there are interest groups in all four quadrants of the ideological space in all five countries suggests that the views of citizens in all corners of the ideological spectrum are being heard at least sometimes. However, to assess the representational bias of interest groups, and compare it with the representational bias of the party system, we need to look more closely at to what extent the overall weight of lobbying activities pulls more in some directions within the two-dimensional space than in others, in relation to where citizens are placed. provides this information.

Figure 5. Overall placement of citizens and interest groups in the two-dimensional space (based on activities).

may be read as follows: the placement of the voters of each country on the Left-Right dimension denotes the difference between the share of citizens whose ideological positioning is to the right and to the left of the mid-point on the scale. For example, 60 per cent of the Belgian citizens placed themselves to the left of center while 40 per cent placed themselves to the right of center. The position of the Belgian citizens on the Left-Right scale, therefore, is −20 (40–60). On the Gal-Tan scale, on the other hand, 52 per cent of the Belgian citizens indicated a placement closer to Gal than to Tan on the scale, while 48 per cent indicated a position further towards tan. The placement of the Belgian citizens on the Gal-Tan scale therefore is −4 (48–52). The same logic applies to the interest groups’ placement which is based on the total number of lobbying activities. The further to the left in the larger the share of lobbying activities of interest groups that placed themselves to the left of center. The further ‘up’ in the picture the larger the share of activities of groups that indicated that they represented values towards Tan more than Gal.

The direction of the arrows shows which citizens benefit from the interest group system in terms of representation in relation to their overall numbers. Overrepresentation in one direction (Left, Right, Gal, Tan) means that there is a larger share of interest groups’ activities than citizens in that part of the two-dimensional ideological space. Underrepresentation in one direction means that there is a smaller share of interest groups’ activities than citizens in that part of the two-dimensional space. For example, the Belgian interest groups are situated to the left and (slightly) below the Belgian citizens in the figure. That means that the Belgian interest groups overall are promoting values that are more Left-wing, and (slightly) more green-alternative-libertarian, than what the share of citizens that hold such views would suggest.

, in combination with and , helps us compare the representativeness of the interest group system with that of the party system in the five countries.Footnote13 Recall that in all countries except Lithuania, the party system failed to represent one group of voters in particular – those situated in the Left-Tan part of the ideological space. demonstrates that in two countries, Sweden and the Netherlands, the interest groups seem to compensate precisely that group of citizens. The interest groups in those two countries are placed further towards Tan and further to the Left (although only slightly so for Sweden) compared to the citizens, thus overrepresenting citizens in that direction. Furthermore, in Lithuania the representational weakness of the party system pertained to the Left-Gal part of the ideological space. This is also precisely the direction in which the interest group system is overrepresenting Lithuanian citizens.

In Belgium and Slovenia, on the other hand, no compensation for the party systems’ lack of representation of Left-Tan citizens seems to be at work. Both the Belgian and (in particular) the Slovenian interest groups pull towards Left-Gal, where there are already several political parties, as seen in and . showed that Slovenia also had a relative dearth of parties representing a significant group of voters with Right-Gal attitudes. Although the interest groups compensate that group of citizens on the Gal-dimension, at the same time they pull to the left rather than to the right.

Overall, the findings indicate that the interest group system can indeed compensate for representational biases in the party system. In three of the five countries – Sweden, the Netherlands and Lithuania – we find that this is the case. However, such compensation is by no means automatic. In Belgium and Slovenia, the overall weight of the interest group activities go in different directions than those preferred by citizens who lack access to parties in their section of the ideological space.

also shows that interest groups are placed to the left of the citizens in all five countries. The overall Left-wing tendency is striking given the common image of interest groups as contributing to an ‘upper-class bias’ (Schattschneider, Citation1960). The similarity between the two Eastern European countries in terms of the representativeness of the interest groups is also noteworthy. Both of these countries have citizens with a much stronger tendency towards Right-Tan than the Western European countries. The interest groups, on the other hand, seem to have their political compasses more attuned to ‘Western’ Left-Gal attitudes.

Conclusions

This article provides evidence that interest groups could potentially fill party-voter representative gaps that arise from certain combinations of economic Left-Right and Gal-Tan preferences within the electorate. Party-voter representation gaps stand in stark contrast to the policy preferences put forward by the interest groups in all five countries of our analysis. In the political systems of both eastern and western Europe, interest groups populated all four quadrants of the Left-Right/Gal-Tan two-dimensional space. Moreover, interest groups recognize the Gal-Tan dimension as important, and a variety of interest groups occupy a full range of positions on the Gal-Tan scale, showing its relevance to the party-group system and the potential of interest groups for representing citizen preferences. In three of the five countries of our analysis, the configuration of interest groups in the two-dimensional space was such that it compensates for the party-citizen gaps by creating a lobbying environment that is more in line with citizens under-supplied by party positions. Our analysis thus shows that interest groups have the potential to supplement the representational role of political parties in contemporary European societies, rather than amplifying any gaps that exist in the citizen-party representational relationship.

At the same time, our findings show that this dynamic is far from given, and thus lead to new questions and offer a productive avenue for future research on the relationship between political parties, interest groups, and the political preferences of citizens in European democracies. Although we find interest group compensation for party-voter representational gaps in three of the five countries we study, there is no clear compensation in the two other countries, Belgium and Slovenia. This would seem to caution against the application of the pluralist compensation mechanism as a general theory. Yet we find it equally, perhaps even more unlikely that the compensation taking place in the other three countries is rather random. In nearly all countries, political parties have left ideological space open for interest groups to fill. Future work should focus on why interest group compensation takes place in some countries but not others.

Our article also has ramifications for the broader question of how to evaluate the representativeness of political systems. The fact that interest groups identify the two ideological dimensions as salient and take positions throughout the full range of these scales indicates that any evaluation of the ideological representativeness of political systems should take both types of actors into account (Rasmussen & Reher, Citation2019). The results have additional implications for our understanding of any ‘crisis of party democracy’ (Invernizzi-Accetti & Wolkenstein, Citation2017, p. 97). Could interest groups emerge as competitors for participatory engagement based on ideology? The question is made all the more intriguing by the fact that the interest groups are Left-leaning in all five countries of our study, and particularly so in countries with a Right-leaning electorate.

We see studies on public perceptions of democratic legitimacy with both interest group and political party policy-making involvement and dynamic, over-time analysis as productive avenues for additional research flowing from our findings. Although public opinion surveys rarely ask individuals about both interest group activity in politics and democratic legitimacy, recent cross-national experimental evidence indicates that citizens in Europe and the USA see interest group participation, particularly equal participation from a variety of groups, as beneficial to the policy-making process (Rasmussen & Reher, Citation2023). We see this as encouraging evidence in favor of our argument that groups can help address representational gaps in party systems. An additional welcome extension would be a study with multiple time points to address aspects of party (and group) responsiveness to public opinion that we could not cover with our cross-sectional design (see, e.g., Ibenskas & Polk, Citation2022). This would allow future research to focus even more clearly on the role of civil society in representing minority views in such contexts.

Acknowledgements

Authors are ordered alphabetically, all authors contributed equally. Earlier versions of this research were presented at the 2017 ECPR General Conference, the 2018 Midwest Political Science Association Annual Conference, and the 2018 Swedish Network for European Studies in Political Science Spring Conference. We thank discussants: Vibeke Hansen, Beth Leech, Carl Dahlström, and other conference participants for helpful comments. Scott Ainsworth, Ryan Bakker, Andreas Hofmann, Raimondas Ibenskas, and Anne Rasmussen also provided valuable feedback on our work. We thank Natalia Alvarado Pachon for excellent research assistance. Frida Boräng and Daniel Naurin acknowledge support from the Swedish Research Council grant 2011-06652 and the Swedish Agency for Youth and Civil Society grant 0940/13. Jonathan Polk acknowledges the support of Swedish Research Council grant 2016-01810.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Not all of these authors use the Gal-Tan terminology and many have somewhat different conceptions of the socio-cultural dimension. While we acknowledge the importance of these differences and debates, since the survey question posed to interest groups was designed to be compatible with the Gal-Tan concept developed by Hooghe and Marks, we use this terminology throughout the paper.

2 We note that groups may have incentives to downplay the importance of ideological dimensions, to appear more nonpolitical than they are. If so, this would lead us to underestimate the importance of ideological dimensions. Thus, if there is any bias in the responses of the interest group population, it should be in the direction of less salience of political dimensions, making this a more challenging test for the salience of ideological dimensions to interest groups.

3 Exact question wording for both political parties and interest groups is included in the appendix.

4 More specifically, several measures included in the CHES data have been cross-validated against party position estimates derived from manifestos, elite surveys, and measures derived from public opinion. These cross-validation exercises have also taken place across several waves of the survey data. Details are available in, for example, Bakker et al., Citation2015.

5 As noted above, very little activity is required for an interest group to be included in the population. To the extent that non-active groups are less likely to respond to surveys, the share of active groups would be higher in our sample than in the overall interest group population. The response rates among active groups may thus be higher than those reported here.

6 While we could create similar additive indices for the parties via sub-dimensional policy questions in the CHES data, these types of questions are not present in the interest group survey. We thus opt for maximizing comparability between the interest groups and political parties by using the Left-Right and Gal-Tan dimension questions.

7 The original EES coding of the immigration variable (QPP17.6) runs from restrictive to open immigration preferences. We reverse this coding so that it is in line with the other two components of the Gal-Tan index, running from Gal (low values) to Tan preferences (high values).

8 Our indices consist of similar items to those used by other research teams working with public opinion data to create multidimensional preference estimates (Van der Brug & Van Spanje, Citation2009; Lefkofridi et al., Citation2014). As a robustness check, we also created factors (rather than additive indices) from the same sets of three variables. The two-dimensional space recovered from these factors are substantively similar to the indices that we present in the main text.

9 High opposition to same-sex marriage among EES respondents in this country drives this finding.

10 Additional descriptive statistics from the 2014 EES data for these five countries also highlight this point. 51% of respondents in these countries are left of the mid-point on redistribution and 41% are below the mid-point (restrictive) on immigration policy. Again, this demonstrates substantial variation in the two-dimensional preference structure of the public.

11 Although the number of Right-leaning interest groups in the Western European countries is small, particularly in Belgium and Sweden, a substantial number place themselves at the midpoint on the Left-Right scale.

12 It is worth noting that the general patterns in and remain also if we weigh the groups by ‘inside’ activities instead of total activities, although, naturally, the interest group intensity is reduced and a few groups that only perform outside activities are dropped.

13 The appendix includes a version of , , Appendix 3, for each country that also includes the positions of political parties in each party system.

14 The case selection and data collection in the Netherlands has been coordinated by Joost Berkhout and Marcel Hanegraaff of the University of Amsterdam, and Caelesta Braun of the University of Leiden, assisted by Jens van der Ploeg.

15 The Lithuanian project is coordinated by Algis Krupavičius and Ligita Šarkutė of Kaunas University of Technology, assisted by Vitalija Simonaitytė and Vaida Jankauskaitė. Šarkutė, L., Krupavičius, A., Jankauskaitė, V., Simonaitytė, V. (2017). Sampling Procedure of Lithuanian Interest Groups Survey. Kaunas: Institute of Public Policy and Administration.

16 Fink-Hafner, D., Hafner-Fink, M., Novak, M.,Kronegger, L. and Lajh, D. (2015) Protocol on Defining Population Of National Interest Groups in Slovenia, Ljubljana: Centre for Political Science Research.

17 The Belgian interest group project is coordinated by Jan Beyers and Frederik Heylen.

18 A major annual political event with speeches, seminars and other political activities, including hundreds of interest groups.

19 The Swedish interest group survey has been conducted by Frida Boräng and Daniel Naurin, as part of the projects ‘Who are the lobbyists? A population study of interest groups in Sweden’, funded by the Swedish Research Council (VR), and ‘The mobilization of attitudinal bias? Attitudinal representativeness of organized interests’, funded by the Swedish Agency for Youth and Civil Society (MUCF).

References

- Aldrich, J. H. (1995). Why parties?: The origin and transformation of political parties in America. University of Chicago Press.

- Allern, E. H., & Bale, T. (2017). Left-of-centre parties and trade unions in the twenty-first century. Oxford University Press.

- Allern, E. H., Hansen, V. W., Marshall, D., Rasmussen, A., & Webb, P. D. (2021a). Competition and interaction: Party ties to interest groups in a multidimensional policy space. European Journal of Political Research, 60(2), 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12403

- Allern, E. H., Hansen, V. W., Otjes, S., Rasmussen, A., Røed, M., & Bale, T. (2021b). All about the money? A cross-national study of parties’ relations with trade unions in 12 western democracies. Party Politics, 27(3), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819862143

- Allern, E. H., Kluever, H., Marshall, D., Otjes, S., Rasmussen, A., & Witko, C. (2022). Policy positions, power and interest group-party lobby routines. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(7), 1029–1048. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1912148

- Bakker, R., De Vries, C., Edwards, E., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. A. (2015). Measuring party positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999–2010. Party Politics, 21(1), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068812462931

- Bakker, R., Jolly, S., & Polk, J. (2012). Complexity in the European party space: Exploring dimensionality with experts. European Union Politics, 13(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512436995

- Beyers, J., Bernhagen, P., Borang, F., Braun, C., Fink-Hafner, D., Heylen, F., Maloney, W., Naurin, D., & Pakull, D. (2016). Comparative interest group survey questionnaire. University of Antwerp.

- Beyers, J., De Bruycker, I., & Baller, I. (2015). The alignment of parties and interest groups in EU legislative politics. A tale of two different worlds? Journal of European Public Policy, 22(4), 534–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1008551

- Beyers, J., Fink-Hafner, D., Maloney, W. A., Novak, M., & Heylen, F. (2020). The comparative interest group-survey project: Design, practical lessons, and data sets. Interest Groups & Advocacy, 9(3), 272–289. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-020-00082-0

- Boräng, F., & Naurin, D. (2022). Political equality and substantive representation by interest groups. British Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 1447–1454. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000041

- De Bruycker, I., & Rasmussen, A. (2021). Blessing or curse for congruence? How interest mobilization affects congruence between citizens and elected representatives. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59(4), 909–928. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13146

- Dobbins, M., & Riedel, R. (2021). Exploring organized interests in post-communist policy-making: The" missing link" (p. 338). Taylor & Francis.

- Duverger, M. (1954). Political parties: Their organization and activity in the modem state. Wiley.

- Easton, D. (1971). Political system. An inquiry into the state of political science (2nd ed). Alfred A. Knopf.

- Eichenberger, S., Varone, F., & Helfer, L. (2022). Do interest groups bias MPs’ perception of party voters’ preferences? Party Politics, 28(3), 567–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068821997079

- Ekiert, G., & Kubik, J. (2017). Civil society in postcommunist Europe: Poland in a comparative perspective. Civil society revisited. Lessons from Poland (pp. 39–62).

- Erlingsson, G. Ó. (2009). Why do party systems tend to be so stable? A review of rationalists’ contributions. Bifröst Journal of Social Science, 3, 113–123. https://doi.org/10.12742/bjss.2009.6

- Flöthe, L., & Rasmussen, A. (2019). Public voices in the heavenly chorus? Group type bias and opinion representation. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(6), 824–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1489418

- Giger, N., & Klüver, H. (2016). Voting against your constituents? How lobbying affects representation. American Journal of Political Science, 60(1), 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12183

- Grande, E., & Kriesi, H.. (2012). The transformative power of globalization and the structure of political conflict in Western Europe. In H. Kriesi, E. Grande, M. Dolezal, M. Helbling, D. Höglinger, S. Hutter, & B. Wüest (Eds.), Political conflict in Western Europe (pp. 3–35). Cambridge University Press.

- Halpin, D., & Jordan, G. (2009). Interpreting environments: Interest group response to population ecology pressures. British Journal of Political Science, 39(2), 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000537

- Hansen, J. M. (1991). Gaining access: Congress and the farm lobby, 1919-1981. University of Chicago Press.

- Heaney, M. T. (2010). Linking political parties and interest groups. In L. S. Maisel, & J. M. Berry (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of American political parties and interest groups (pp. 568–587). Oxford University Press.

- Hobolt, S. B., & De Vries, C. E. (2015). Issue entrepreneurship and multiparty competition. Comparative Political Studies, 48(9), 1159–1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015575030

- Hobolt, S. B., & de Vries, C. E. (2015). Issue entrepreneurship and multiparty competition. Comparative Political Studies, 48(9), 1159–1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015575030

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Wilson, C. J. (2002). Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative Political Studies, 35(8), 965–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236310

- Howard, M. M. (2003). The weakness of civil society in post-communist Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Ibenskas, R., & Polk, J. (2022). Congruence and party responsiveness in Western Europe in the 21st century. West European Politics, 45(2), 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1859756

- Invernizzi-Accetti, C., & Wolkenstein, F. (2017). The crisis of party democracy, cognitive mobilization, and the case for making parties more deliberative. American Political Science Review, 111(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000526

- Klüver, H. (2020). Setting the party agenda: Interest groups, voters and issue attention. British Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 979–1000. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000078

- Kollman, K., Miller, J. H., & Page, S. E. (1992). Adaptive parties in spatial elections. American Political Science Review, 86(4), 929–937. https://doi.org/10.2307/1964345

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge University Press.

- Lax, J. R., & Phillips, J. H. (2012). The democratic deficit in the states. American Journal of Political Science, 56(1), 148–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00537.x

- Layman, G. C., & Carsey, T. M. (2002). Party polarization and" conflict extension" in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 46(4), 786–802. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088434

- Lefkofridi, Z., Wagner, M., & Willmann, J. E. (2014). Left-authoritarians and policy representation in Western Europe: Electoral choice across ideological dimensions. West European Politics, 37(1), 65–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2013.818354

- Mansbridge, J. (2009). A “selection model” of political representation. Journal of Political Philosophy, 17(4), 369–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00337.x

- Marks, G., Hooghe, L., Nelson, M., & Edwards, E. (2006). Party competition and European integration in the east and west: Different structure, same causality. Comparative Political Studies, 39(2), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414005281932

- Müller, W. C. (2000). Political parties in parliamentary democracies: Making delegation and accountability work. European Journal of Political Research, 37(3), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00515

- Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press.

- Otjes, S., & Rasmussen, A. (2017). The collaboration between interest groups and political parties in multi-party democracies. Party Politics, 23(2), 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068814568046

- Persson, M. (2015). Education and political participation. British Journal of Political Science, 45(3), 689–703. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000409

- Polk, J., Rovny, J., Bakker, R., Edwards, E., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Koedam, J., Kostelka, F., Marks, G., Schumacher, G., Steenbergen, M., Vachudova, M., & Zilovic, M. (2017). Explaining the salience of anti-elitism and reducing political corruption for political parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill expert survey data. Research & Politics, 4(1), 2053168016686915. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168016686915

- Rasmussen, A., & Reher, S. (2019). Civil society engagement and policy representation in Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 52(11), 1648–1676. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019830724

- Rasmussen, A., & Reher, S. (2023). (Inequality in) interest group involvement and the legitimacy of policy making. British Journal of Political Science, 53(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000242

- Røed, M. (2022). Party goals and interest group influence on parties. West European Politics, 45(5), 953–978. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1921496

- Rohrschneider, R., & Whitefield, S. (2012). The strain of representation: How parties represent diverse voters in western and Eastern Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Rovny, J., & Edwards, E. E. (2012). Struggle over dimensionality: Party competition in Western and Eastern Europe. East European Politics and Societies, 26(1), 56–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325410387635

- Rovny, J., & Polk, J. (2017). Stepping in the same river twice: Stability amidst change in Eastern European party competition. European Journal of Political Research, 56(1), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12163

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The semisovereign people. A realist’s view of democracy in America. The Dryden Press.

- Schlozman, K. L., Verba, S., & Brady, H. E. (2012). The unheavenly chorus: Unequal political voice and the broken promise of American democracy. Princeton University Press.

- Schmitt, H., Hobolt, S. B., Popa, S. A., & Teperoglou, E. (2015). European Parliament Election Study 2014, Voter Study.

- Spoon, J. J., Hobolt, S. B., & De Vries, C. E. (2014). Going green: Explaining issue competition on the environment. European Journal of Political Research, 53(2), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12032

- Strøm, K. (2000). Delegation and accountability in parliamentary democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 37(3), 261–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00513

- Thomassen, J. (2012). The blind corner of political representation. Representation, 48(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2012.653229

- Truman, D. B. (1951). The governmental process. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Van der Brug, W., & Van Spanje, J. (2009). Immigration, Europe and the ‘new’cultural dimension. European Journal of Political Research, 48(3), 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.00841.x

- Van de Wardt, M., De Vries, C. E., & Hobolt, S. B. (2014). Exploiting the cracks: Wedge issues in multiparty competition. The Journal of Politics, 76(4), 986–999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381614000565

- Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press.

- Wüest, B., Helbling, M., & Höglinger, D. (2012). Actor configurations in the public debates on globalization. In H. Kriesi, E. Grande, M. Dolezal, M. Helbling, D. Höglinger, S. Hutter, & B. Wüest (Eds.), Political conflict in Western Europe (pp. 254–273). Cambridge University Press.

Appendices

Appendix 1: sampling procedure

In the Netherlands, The Dutch sample includes 2479 organizations, selected from attendance lists of public hearings of the Dutch House of Representatives between 2012 and 2014 (Hoorzittingen en Ronde Tafel Gesprekken van (commissies van) de Tweede Kamer), supplemented with a sample of the Dutch Pyttersen’s Almanak 2013 (containing both politically inactive and active organizations). The response rate was 38 per cent, thus including a total of 937 groups.Footnote14

In Lithuania, the sampling frame includes active Lithuanian interest groups operating at the national level, selected from the major Lithuanian business information directory (www.rekvizitai.lt). The population was subsequently supplemented with lists of interest organizations provided by Lithuanian ministries and government agencies. The total population amounted to 905 organizations.Footnote15 The response rate is 40 per cent, 365 groups.

The main source for defining the interest group population in Slovenia is the Agency of the Republic of Slovenia for Public Legal Records and Related Services (AJPES), which is the primary source of public information on business entities in Slovenia. The total population amounted to 1203 organizations. The response rate was 36 per cent, which means that 439 groups answered the survey.Footnote16

The mapping of the Belgian population is based primarily on the Kruispuntbank directory of organizations (KBO). The Belgian interest group population consists of 1691 organizations, of which 693 (41 per cent) answered the survey.Footnote17

The population of interest groups in Sweden was identified through three sources: (1) All incoming letters and e-mail to the Government Offices during 2011 from organized interests (excluding, for example, communications from individuals, public authorities and local government authorities). (2) All responses to proposals referred for consideration by the government (remisser) during 2011. These lists include organizations that the government has selected as ‘interested parties’, which have been approached and asked for their views on particular policy issues, and organizations that have provided their views without having been contacted. (3) Lists of all organizations that organized events during Almedalsveckan 2011.Footnote18 In total, 1534 groups were identified. 650 of these answered the survey (a response rate of 42 per cent).Footnote19

Appendix 2: survey question wording

Measuring ideological dimensions, parties

The question used to measure Left-Right position for the parties was the following:

‘Parties can be classified in terms of their stance on economic issues. Parties on the economic left want government to play an active role in the economy. Parties on the economic right emphasize a reduced economic role for government: privatization, lower taxes, less regulation, less government spending, and a leaner welfare state.’ Respondents were asked to place the parties from 0 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right).

The question used to measure Gal-Tan position for the parties was the following: