ABSTRACT

Perceptions of an East–West divide in the European Union (EU) with regard to democracy have led to re-evaluations of EU eastern enlargement as a policy failure and militate against further enlargement. This article examines the accuracy of narratives of an intra-EU East–West divide on democracy, in which the western member states outperform the eastern members, and in which the former support, and the latter oppose, rule of law (RoL) interventions by the EU in member states engaged in democratic backsliding. The article considers two aspects of a potential democracy divide: the quality of democracy and attitudes towards RoL interventions. It draws on several quantitative indicators for a more comprehensive assessment of intra-EU democracy divides and uses set-theory to identify different in- and out-groups that demarcate such intra-EU divides. Although different indicators and different conceptions of set-membership reveal to varying extents East–West patterns, none fit with a clear regional divide. It is more fruitful to conceive of these differences as a continuum, with (currently) a small group of (western) member states at one end and a small group of (eastern) members at the other, and most member states in distinctive sub-groups in-between.

Introduction

Almost two decades after the eastern enlargement of the European Union (EU), an East–West divide among the member states appears ubiquitous (Volintiru et al., Citationforthcoming). Signs of the divide appear to extend well beyond EU policy, ranging from Covid-19 vaccination rates where ‘low vaccine take-up has exposed a deep east–west faultline’ (Henley, Citation2021, p. 1) to performances in the European football championship in summer 2021 (Wilson, Citation2021). Yet it is the issue area of democracy that commentators tend to identify most prominently as a manifestation of an East–West divide in the EU.

Commentators detect collective regional differences between western and eastern EU members in two distinctive dimensions of democracy. The first dimension concerns the quality of liberal democracy in the member states. For example, Anghel (Citation2020, p. 180) lists ‘rule-of-law consolidation’ as the first of three issues in which ‘East–west divides will continue to inhibit European integration’, or Volintiru et al. (Citation2021, p. 94) identify it as one of four major areas where ‘division is clearly recorded between East and West’. Indeed, studies of democratic backsliding have been at the forefront of framing the issue as a general ‘eastern’ problem in the EU. The narrative of an East–West democracy divide is – unwittingly – perpetuated by accounts that refer to democratic backsliding as a general problem of all the EU’s post-communist eastern member states. A typical example of such a generalisation is the title ‘Eastern Europe Goes South: Disappearing Democracy in the EU’s Newest Members’ (Mueller, Citation2014), even if the actual analysis focuses primarily on the specific case Hungary and emphasises that ‘not every new EU member has followed the same path’ (Citation2014, p. 16). The focus on a regional dimension of backsliding is then further perpetuated by studies that explicitly emphasise a low quality of democracy as a regional phenomenon ‘beyond Hungary and Poland’ (e.g., Cianetti et al., Citation2018). The notion of regional-specific problems with democratic consolidation also relates to a focus on common post-communist legacies (e.g., Pop-Eleches, Citation2015). A more recent strand of the backsliding literature also aligns with the notion of backsliding as a general problem of the EU’s eastern members by emphasising that the process of accession to the EU itself has a detrimental effect on democracy in all these newer EU member states (Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2019; Grzymala-Busse & Innes, Citation2003; Meyerrose, Citation2020; Slapin, Citation2015).

The other key dimension of an East–West divide on democracy has gained prominence more recently in the context of debates about whether and how the EU should respond to democratic backsliding in member states. Commentators suggest that eastern EU member states are much more reluctant than the western members to enforce the EU’s commitment to liberal democracy, and obstruct efforts by western members to use EU sanctions against backsliding member states. For example, the Financial Times has introduced the tag ‘EU eastern tensions’ for articles about backsliding in the member states and the EU’s instruments for rule of law (RoL) interventions. Ciobanu et al. (Citation2019) report that the proposal for a RoL budget conditionality has ‘further widened the East–West divide in the EU family’ (Citation2019, p. 2; see also Volintiru et al., Citation2021, p. 100). Likewise, Valášek (Citation2018, p. 1) suggests that ‘[EU] moves against Hungary and Poland have had a divisive effect. … Central and Western Europe are drifting apart’.

Some contributions to the literature have rejected the notion of an intra-EU East–West divide on democracy. Zielonka (Citation2019) and Lehne (Citation2019) consider it a ‘myth’, while Bohle and Greskovits (Citation2019, p. 4) suggest that it is based on misperceptions. Volintiru et al. (Citation2021, p. 93) argue that the real East–West divide in the EU is a persistent socio-economic divide that is ‘often narrated as a political divide’. However, rebuttals of this narrative are often limited in their analytical depth and breadth of evidence engaged.

Analyses that refute the notion of an East–West divide regarding the quality of democracy typically remain at a fairly general level. For example, Lehne (Citation2019) largely counters the ‘myth that the CEE countries suffer from endemic rule-of-law deficits’ by pointing out that we must not ‘conflate the behaviour of a few governments with the democratic and rule-of-law standards of the CEE as a group’, while Zielonka (Citation2019, pp. 1–2) suggests that many political fault lines that run across the EU rather than ‘one single fault line, between East and the West’. While these arguments are well taken, their persuasiveness would be strengthened if they were backed up by quantitative cross-country data on the quality of democracy. Yet to my knowledge, there has been no attempt to ascertain the extent to which there is a geographical democracy divide empirically in such a way. Some analyses of democracy in East Central Europe use quantitative indicators and challenge the notion of regional homogeneity by identifying different clusters of states, e.g., according to the extent to which they display different combinations of hollowing of democracy and backsliding (Greskovits, Citation2015) or democratic consolidation and decline (Stanley, Citation2019). However, by focusing on a single region, such studies cannot address the question whether intra-regional differences also undermine the cross-regional differences implied in an East–West divide.

Studies that challenge an East–West narrative concerning attitudes towards RoL interventions tend to be based on narrow empirical evidence. For example, Volintiru et al. (Citation2021, p. 100) draw on a coding of government preferences, or Valášek (Citation2018, p. 1) on national vote shares concerning one EP resolution. Although these indicators are certainly highly pertinent and well suited for a comparative analysis, these data only provide a partial picture of preferences towards RoL interventions across EU member states.

This article addresses these shortcomings in empirical assessments of an EU democracy divide, first, by focusing on both the quality of democracy as well as attitudes towards RoL interventions, rather than treating them separately. Second, it uses quantitative comparative data and descriptive statistics to capture and evaluate relevant intra-EU divisions. Finally, it addresses the problem of narrow empirical indicators and the challenge of choosing among several plausible operationalisations. For both dimensions of a democracy divide, the article considers five different operationalisations, and contrasts the resulting patterns using set-theory.

The main goal of this article is thus empirically-descriptive (Gerring, Citation2012): I aim to establish how accurate narratives and perceptions of an intra-EU East–West divide on democracy are. The article is thus primarily a mapping exercise to provide a more solid empirical basis for the debate. In the following, I first discuss briefly why it matters whether the narrative of an East–West democracy divide in the EU is accurate, and why the perception that such a divide exists is politically consequential. The article then focuses in turn on different indicators of an intra-EU divide, first, for the quality of democracy in the member states, and second, for attitudes towards EU interventions to sanction RoL backsliding. For each of these dimensions, I use several indicators to establish individual sets of in-groups and out-groups demarcating an intra-EU divide. I use the language of set-theory, since the notion of a divide fits well with the concept of membership in two distinctive groups. In each dimension, these in-groups are formed by the democracy leaders and supporters of RoL interventions respectively, while in-group (or set) membership can vary depending on the indicators used. For each dimension, I then identify an overall in-group by drawing on set-membership for the individual indicators, and finally contrast the in- and out-groups for the two dimensions.

The article finds that while there are indeed certain East–West patterns with regard to democracy in the EU that should not be understated, it cautions against a narrative of a regional democracy divide, which wrongly suggests that eastern and western member states neatly fit on opposite sides of the pattern, and disregards the fluidity of some of the patterns. With regard to the quality of liberal democracy, an East–West element is undeniable in that – depending on the specific indicators used – most, or even all, of the western member states are among the leader-group, and certain eastern members are always outside. However, not all member states conform to these patterns. Again, depending on the operationalisation used, several eastern member states are in the in-group. An East–West pattern is also visible with regard to RoL interventions, but again, it does not conform to an East–West divide. The overall pattern, combining the quality of democracy and attitudes towards RoL interventions, suggests that the black and white picture of western leaders and eastern laggards suggested by the language of an East–West democracy divide is too simplistic. Intra-EU differences are better captured by distinguishing between several sub-groups of member states along a continuum.

Why it matters whether there is an intra-EU divide on democracy

Does it matter whether there is an East–West democracy divide in the EU? Arguably, current perceptions of the existence of such a divide have already political consequences. First, this perception shapes attitudes towards future eastern enlargements of the EU. As Valášek (Citation2018, p. 1) points out, ‘[t]he perception of an unbridgeable divide and an authoritarian creep is beginning to lead to a reevaluation of EU enlargements since 2004’. Similarly, Lehne (Citation2019, p. 1) suggests that due to this perception, ‘[w]hat used to be considered a historic achievement is now often viewed more critically. Many in Western Europe now think the EU was extended too far and too quickly … ’. There is no doubt that both public opinion and government policy in most western European member states have turned against further enlargement (see e.g., Sedelmeier, Citation2020, pp. 460–463), even if the EU has recognised Ukraine, Moldova, and Bosnia–Herzegovina as candidate countries after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Rupnik (Citation2019, p. 1) argues that there is a clear link between enlargement fatigue and the notion of an East–West democracy divide:

[The interpretation that there is] a break between the “old” and “new” EU Member States on … democracy and the rule of law … [is often] favoured in the media or in declarations of political figures on both sides of a newly restored dividing line [in the EU]. In the West of the continent, this is perceived as a threat to the European project and, in France in particular, a justification in hindsight of the reservations with regard to the very idea of enlarging the EU to the East … .

The other way in which perceptions of an East–West democracy divide can affect EU policy is with regard to the EU’s sanctioning of democratic backsliding. This narrative entails the risk of a certain determinism about democracy in the newer, post-communist member states. If the latter are perceived to be unable to achieve similar levels of democracy as the western members, then it may also be seen as inevitable that they will either backslide or at best merely maintain a low level of democracy once the incentives of pre-accession conditionality are gone. If cases of backsliding are considered lost causes, EU interventions would be pointless; they would be unnecessarily disruptive for cooperation in the EU or even counterproductive. In this way, the notion of an East–West democracy divide can predispose EU member states against using sanctions to enforce democracy internally.

In sum, a perception of an enduring East–West divide on democracy is detrimental to the EU’s ability to protect democracy in its member states, and to the prospect of further EU enlargement. In turn, the lack of a credible enlargement perspective limits the EU’s ability to promote democracy in candidate countries (Schimmelfennig & Sedelmeier, Citation2020). Establishing whether this perception is accurate is then not merely an academic exercise in semantics but has a clear political relevance.

The quality of democracy across EU member states

To assess the extent to which there is an East–West democracy divide in the EU, this section focuses on differences in the quality of democracy across the member states. Any assessment where individual member states are located in relation to an intra-EU democracy divide is obviously highly sensitive to the choice of method and operationalisation of such a divide. One key choice for quantitative comparative analyses concerns the selection of a specific dataset from among the leading democracy datasets. Although their measures of regime types are usually highly correlated, this is much less the case with regard to regime change and backsliding (Waldner & Lust, Citation2018). I use the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset (Coppedge et al., Citation2022), which is widely used for such purposes (e.g., Haggard & Kaufman, Citation2021; Meyerrose, Citation2020) and uses more nuanced scores than other indices such as Freedom House or Polity 4. Among the different indices used by V-Dem, I use the ‘liberal democracy index’ (LDI), which is particularly appropriate for assessing a possible East–West divide in the EU, as democratic backsliding in the EU has typically occurred through ‘executive aggrandizement’ (Bermeo, Citation2016). The LDI precisely focuses on the limits to the exercise of executive power, such as through constitutionally protected civil liberties, strong rule of law, an independent judiciary, and effective checks and balances (Coppedge et al., Citation2022, p. 44).

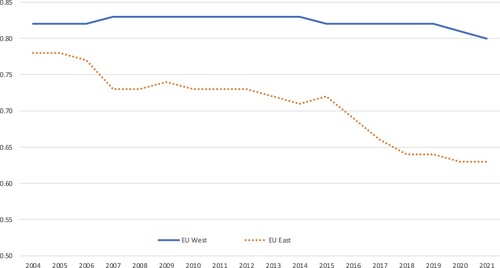

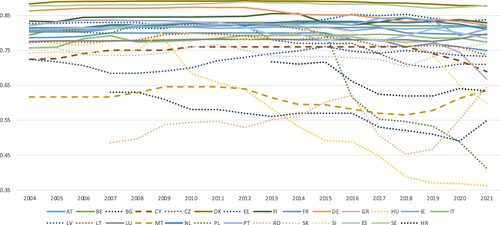

Yet even with the same dataset, different methods can be used to draw the line of an intra-EU divide. Comparing regional means of the LDI scores is a deceptively straightforward method to establish whether there is an East–West divide. Such a comparison of regional averages of democracy is highly suggestive of an East–West divide. shows that, on aggregate, the eastern members not only continue to lag behind the western membersFootnote1 (see also Börzel & Schimmelfennig, Citation2017), but that the gap is widening. However, such regional aggregate scores mask considerable variation across the EU’s eastern members (see ), as they are highly sensitive to the extreme cases within the region.

Figure 1. Average liberal democracy scores by region. Note: V-Dem Liberal Democracy index (1 highest, 0 lowest).

Figure 2. Liberal democracy scores by EU member states. Note: V-Dem Liberal Democracy index (0–1). Dotted lines indicate eastern EU member states, solid lines western member states (Malta and Cyprus in dashed lines).

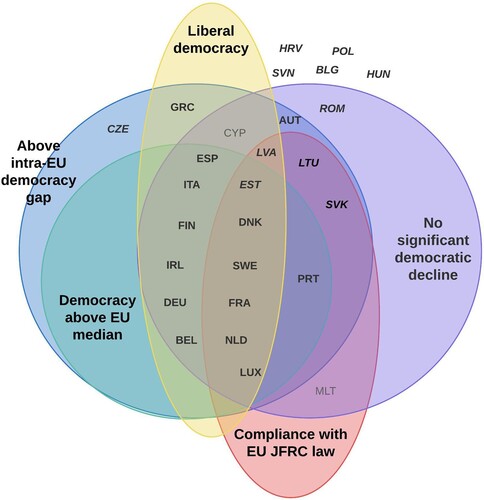

There are several ways to provide a more nuanced account of individual member states’ positions relative to an intra-EU divide on democracy, and each way leads to somewhat different compositions of the groups of countries on the two sides of the divide. I draw on five different operationalisations that can be plausibly used for this purpose. These operationalisations are certainly not exhaustive, but my selection should provide a reasonably comprehensive picture. For each of these operationalisations, I identify the resulting intra-EU divide between an in-group and an out-group. While different indicators may suggest different labels for in- and out-group, I use ‘democracy leaders’ for the set of countries forming the in-group, while the out-group are the ‘democracy laggards’. After establishing the results for each of the five indicators, I will compare these results by capturing the five sets of partly overlapping in-groups in a Venn diagram (Figure ).

Country positions relative to the EU’s central tendency

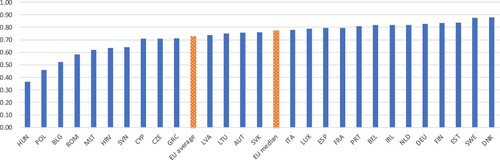

First, we can compare the democracy scores of individual member states to those of other member states. This method has the advantage of providing a clear sense of the member states’ relative position within the EU. I first establish whether a member state’s LDI score is higher or lower than the EU’s mean score. I calculate a weighted average of the last 3 years (2019–21). This allows us to capture recent trends, rather than providing only a snapshot of the most recent year, while putting greater weight on the most recent years.Footnote2 However, to assess where a member state is located with regard to an EU divide defined in relation to the central tendency for the liberal democracy score in the EU, I use the median score for the EU. While this is a more demanding threshold, the presence of extreme cases like Hungary and Poland makes this arguably a more appropriate measure. presents the results.

Figure 3. Liberal democracy scores compared to EU average and median. Note: V-Dem Liberal Democracy index (0–1).

reflects certain East–West differences, but not a clear East–West divide. Almost all western members are above the EU average (0.726), but so are several eastern members – Estonia (0.836), Lithuania (0.749), Latvia (0.736), and Slovakia (0.759) – while Greece is not (0.711).Footnote3 A comparison with the EU median rather than the mean results in Estonia remaining the only eastern member state above the EU median (0.772), while two western members are below: Austria (0.756) alongside Greece.

Country positions relative to a gap in member state democracy scores

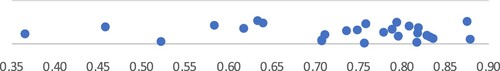

The above comparison of individual member states to the EU’s central tendency is indicative of leader/laggard dynamics in the EU. But since individual countries may be narrowly above or below the mean (or median), measures of the central tendency may not be good indicators of an actual intra-EU divide, in the sense of two clearly separate clusters of member states. The second method I use therefore seeks to identify two distinctive clusters of member states according to their LDI scores.Footnote4 presents the same data for the member states as , but makes it easier to identify clusters across the scores. Among the gaps across the scores, the clearest indication of an intra-EU divide is a gap between those states scoring 0.708 and above, and those scoring 0.639 or less.Footnote5 Using this gap as a reference point, all western states are part of the in-group of democracy leaders, but a larger number of eastern members are too: the Czech Republic (0.708) in addition to those four eastern members that are also above the EU average (Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Estonia).

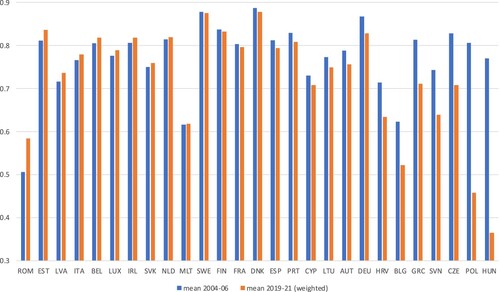

Decline (and improvement) of democracy across member states

Third, when assessing the intra-EU democracy divide, we may be not only interested in countries’ relative positions within the EU, but in the extent to which they experienced a decline in democracy. The concern about ‘democratic backsliding’ in the EU is precisely about a trend of democratic regression, rather than simply about lower (initial) levels of democracy in the eastern members. Again, quantitative analyses differ in how they establish backsliding. For example, among analyses using the LDI, Haggard and Kaufman (Citation2021) focus on cases in which there has been a statistically significant decline from the peak score.Footnote6 Meyerrose (Citation2020) compares scores at 5-year intervals and calculates whether in a given year there has been a decline compared to a country’s score at t-5.Footnote7 The V-Dem Annual Report for 2021 establishes whether there has been a ‘substantial and significant’ decline in LDI scores in the 10-year interval between 2010 and 2020 (Alizada et al., Citation2021).Footnote8

I compare the most recent LDI scores with the scores when the eastern member states joined the EU.Footnote9 According to this calculation, shows that the great majority of member states experienced a deterioration of democracy (17 of the 27), as did both the eastern and western members on average. Although in seven eastern members democracy declined (including the four member states with the greatest decline), in Romania, Estonia, Latvia, and Slovakia it improved (with the former three recording the greatest improvements in the EU). Conversely, the LDI score decreased in nine of the 14 West European members (Greece, Germany, Austria, Portugal, Spain, Denmark, France, Finland, and Sweden).

Figure 5. Decline and improvement of democracy across EU member states. Note: V-Dem Liberal Democracy index; for weighted mean (2019–21), see footnote 9.

However, in most cases, the decrease is fairly small (and in some cases from a very high starting point). I, therefore, use a more demanding measure for a deterioration of democracy as a decrease in the LDI score of 10 per cent or more from the reference period.Footnote10 With this threshold, the East–West pattern becomes more pronounced: among the western members, only Greece experienced such a decline. Yet the picture is still far from a clear fit: the in-group of EU member states without a significant decline includes five of the eleven eastern members:Footnote11 Romania, Estonia, Latvia, and Slovakia, which experienced no decline, and Lithuania, where the decline is below the threshold.

Regime types across member states

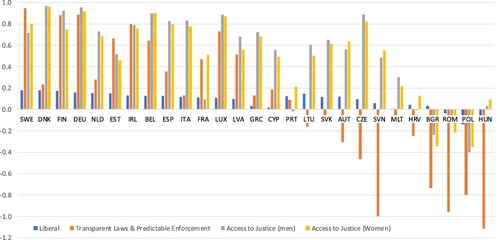

Fourth, it might not only matter whether democracy has deteriorated as such, but whether the deterioration has undermined a country’s status as a democracy. More generally, we might want to assess the quality of democracy in the EU member states not merely in reference to other EU member states, but with regard to an external anchor or measure of regime type. Unlike other datasets, such as Freedom House, the V-Dem LDI score does not directly identify a threshold score for democracies. Instead, V-Dem identifies key aspects of liberal democracy to distinguish liberal democracies from electoral democracies (Lührmann et al., Citation2018, p. 65). These criteria require certain minimum scores with regard to transparent laws and predictable law enforcement, effective access to justice (for men and for women), as well as with regard to liberal principles overall. depicts the extent to which each member state meets the minimum requirements for the four separate categories.Footnote12 Positive scores indicate that a country exceeds the minimum score for a criterion; a negative score indicates that a country falls short. A country must meet the minimum requirements for each criterion to be considered a liberal democracy.

Figure 6. Exceeding/falling short of minimum scores for V-Dem liberal democracy (2021). Note: Liberal: V-Dem Liberal component index (0–1, minimum score 0.8); Transparent laws with predictable enforcement, Access to Justice (0–4, minimum score 3); see footnote 11

The distinction between liberal and electoral democracies in the EU displays strong East–West dynamics, but again, not all countries follow the pattern. Most eastern member states do not meet the conditions for liberal democracies. Hungary does not even qualify as an electoral democracy; it is only an electoral autocracy. Among the other eastern member states, Poland and Romania fail all the criteria, while Bulgaria and Croatia fail the criteria for transparent laws and predictable enforcement and access to justice. The Czech Republic, Slovenia, Lithuania, and Slovakia only fall short of the transparent law and enforcement criterion, and in the latter two cases, come fairly close to meeting it. The only eastern member states that qualify as liberal democracies are Estonia and Latvia, while two western member states are only electoral democracies: Austria fails on transparent laws and enforcement, while Portugal falls narrowly short of the criterion regarding access to justice for men.

Compliance with EU law in the area of justice, fundamental rights and citizenship

The final method I use to assess democracy across the member states focuses on infringements of EU law in the issue area ‘Justice, Fundamental Rights and Citizenship’ (JFRC). While such infringement cases must not be confused with breaches of Article 2 of the EU treaty, which commits member states to liberal democratic values, infringements of EU legislation on JFRC could be indicative of deficiencies of liberal democracy.

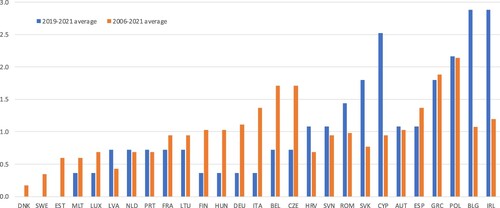

depicts both the more recent infringement record of the member states in the JFRC issue area and for the entire period since eastern enlargement.Footnote13 The leader group for JFRC compliance are all member states with annual infringements below the EU annual average both for the overall period 2006–21, and for the more recent years (2019–21), i.e., a score below 1 for both annual averages in . Only 10 of the 27 member states are part of the leader group according to this method. While there are some similarities in in-group membership with those derived from the other methods used in this article, here the East–West pattern is least pronounced. The in-group includes six western member states (Denmark, Sweden, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, and France) as well as three eastern members (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania).

Comparing intra-EU divides on the quality of democracy

The Venn diagram in depicts the position of the member states regarding the different sets of leader groups, or in-groups, resulting from these different indicators of intra-EU divisions with regard to the quality of democracy. We can use states’ membership in the different sets to identify a narrow, a broad, and an intermediate conception of distinguishing between an overall in-group and out-group for an intra-EU divide regarding this dimension of democracy.

Figure 8. Different intra-EU divides on the quality of democracy. Note: For the definition of group membership, see the discussions for above.

A narrow conception of an overall in-group requires a country to be a member of all of the five sets of in-groups. The resulting set of six member states includes one eastern member – Estonia – and five western members – Denmark, Sweden, Netherland, Luxembourg, and France. At the other extreme, a broad conception of the overall in-group with regard to the quality of democracy only requires a state to be a member of at least one of the sets. In this broad conception, only five EU member states are in the out-group, and all are eastern members: Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Slovenia, and Croatia. Finally, an intermediate conception requires countries to belong to at least to a majority of the different in-groups (three of the five sets) in order to qualify for the overall in-group. In this intermediate conception, the overall in-group includes almost all western member states (but not Greece and Austria) and four of the eleven eastern members (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Slovakia).

These different conceptions of an intra-EU democracy divide on the quality of democracy reflect certain East–West patterns in the set membership, but it is far from a perfect fit for a clear East–West divide. Although the out-groups are composed mostly or even exclusively of eastern members (except for the narrow conception), and the in-groups tend to be dominated by western members, the in-groups always include eastern members too: one for the narrow conception, four for the intermediate, and six for the broad conception.

Attitudes toward rule of law interventions by the EU

To assess the extent to which there is an East–West democracy divide in the EU, this section complements the analysis of the quality of democracy in the previous section with an examination of differences across the member states with regard to their position on enforcing the RoL by EU institutions. The two issues are obviously not unrelated: member states with a poor democracy record are likely to oppose RoL interventions, since they are their likely targets. However, as the following discussion shows, attitudes towards RoL enforcement do not simply mirror democracy levels, especially when considering different indicators.

To compare these attitudes, this article considers five issues that capture different aspects of member states’ preferences and behaviour: (i) government preferences on RoL interventions by EU institutions; (ii) government preferences on the creation of new EU instruments for such interventions; (iii) the support of national MEPs for European Parliament (EP) resolutions on using Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU); (iv) the debate among the member parties of the European People’s Party (EPP) about the expulsion of Fidesz; and (v) the joint letter by some heads of state and government to the presidents of the Council and Commission condemning Hungarian legislation discriminating against the LGBTQ + community in 2021. As these various cases do not only relate to government preferences, but also include the positions of national member parties of the EPP, or of national MEPs from different parties, they represent a broader range of national preferences.

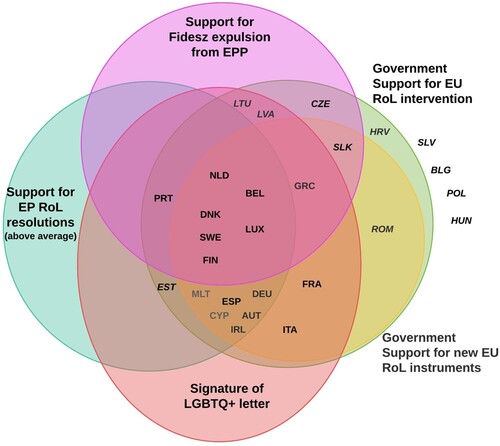

In the following, I discuss these issues in turn, and identify for each of them the resulting memberships in the set of states that support RoL interventions. I depict and summarise the resulting in- and out-groups that characterise the various intra-EU divides on RoL interventions derived from these different issues in the Venn diagram in .

To compare government preferences on RoL interventions, I draw on the European Council on Foreign Relation’s ‘Policy Intentions Mapping’ (Busse et al., Citation2020), which examines the preferred policies of the member state governments across 20 policy areas, including the approach of EU institutions to the rule of law. For RoL interventions, the mapping distinguishes between four preferred outcomes, but the main divide is between governments that are in favour of EU interventions to protect the RoL and those who are not. There is a certain East–West pattern to this divide. Those governments that are opposed to EU interventions are all eastern members (Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, and Slovenia),Footnote14 while all western members support interventions. However, seven eastern member states also support interventions: Romania, Slovakia, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia.

I use the mapping to identify an additional division regarding government attitudes on RoL interventions. Among those governments with a preference for EU interventions to protect the RoL, Busse et al. (Citation2020) further distinguish between those who prefer the EU to do so using only existing tools, and those who also support the development of new tools.Footnote15 The set of governments that support new tools is thus a subset of those who support EU RoL interventions, and the in-group is accordingly smaller. It includes only two eastern members (Romania and Slovakia) but also excludes one western member state (Portugal).

Votes on EP resolutions that support the use of, or the threat to use, Article 7 TEU typically show strong cohesion within the EP’s political groups rather than voting along national lines (Avdagic & Sedelmeier, Citation2018; Sedelmeier, Citation2014, p. 111). At the same time, it is possible to establish the extent to which national MEPs support or oppose such resolutions. Adding up all votes on the ten relevant EP resolutions between 2013 and 2019,Footnote16 in only two member states did MEPs vote more frequently against than in favour: Poland and Hungary (as well as the UK). Since the great majority of national MEPs typically voted in favour of the resolutions,Footnote17 simply comparing states according to whether their national MEPs overall supported or opposed the EP resolutions does not reveal much variation across member states. A more nuanced picture of the relative support across the member states is whether the support among national MEPs was above the average for all member states. According to this divide, which then sets a very high bar for the in-group of states in support of RoL interventions, only one eastern member state (Estonia) is in the set of states with above-average support, while three western member states are not (Greece, France, Italy).

The drawn-out debate in the EPP about whether to expel Fidesz gained momentum through letters from several national member parties demanding its expulsion. In March 2019, 11 parties signed such letters, and in April 2020, 13 parties did.Footnote18 I include a country in the set of member states supporting expulsion if a national EPP member of the country demanded the expulsion on at least one of these occasions. EPP members from Belgium, Finland, Greece, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Sweden did so on both occasions, while in Portugal they did so only in March 2019, and in the Czech Republic, Denmark, Slovakia, and the Netherlands only in April 2020. The group of member states in which an EPP member party supported the expulsion thus includes a clear majority from the EU’s western members (eight states). However, it also includes three eastern members (Lithuania, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia), while it excludes six western member states. The divide is therefore far from a neat East–West cleavage.

Finally, in June 2021, the heads of state and government of 18 member states took the unusual step of publicly criticising Hungarian legislation prohibiting portrayals of homosexuality or transgender people in content shown to minors. In a joint letter to the presidents of the Commission and the European Council, they condemned a ‘flagrant discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation, identity, and expression’ and demanded from the Commission to use ‘all available instruments’. The signatories included all of the western member states, but also three eastern members: Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia.Footnote19

The Venn diagram in depicts the various intra-EU divisions regarding these five issues that reflect differences in positions across the member states on RoL enforcement. Again, we can derive from states’ membership in these overlapping sets of in-groups a narrow, broad, and intermediate conception of an overall in-group and an out-group for an intra-EU divide on RoL interventions.

The narrow conception of the intra-EU divide (which includes only those states that are members of all of the sets) and the broad conception (which includes all those that are members of at least one of the sets) both display certain East–West patterns. For the former, the in-group is a small subset of western European countries: the Benelux countries and the Nordic countries. For the latter, the outgroup is exclusively composed of eastern members: Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, and Bulgaria. Yet for both conceptions the other side of the divide includes a mix of eastern and western member states. The notion of an East–West divide is least tenable for intermediate conception, which includes in the overall in-group all states that are members in at least three of the five sets: although the in-group includes all of the EU’s western members, it also includes four of the 11 eastern members: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Slovakia.

Intra-EU divisions on democracy: combining quality of democracy and attitudes towards RoL interventions

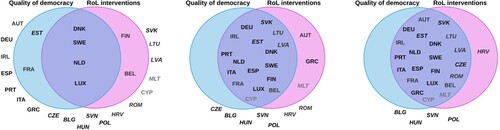

We can obtain a more comprehensive picture on the extent to which there is an intra-EU divide on democracy by contrasting the Venn diagrams in , which captures intra-EU divides regarding the quality of democracy, and , which depicts the intra-EU divides on RoL interventions. By contrasting the overall in-groups – the set of democracy leaders and the set of supporters of RoL interventions – for each of the narrow, intermediate, and broad conception of these in-groups leads to three different conception of an intra-EU democracy divide that combines both dimensions (the quality of democracy and attitudes towards RoL interventions). depicts the sets of in- and out-groups for the two dimensions in three separate Venn diagrams for the narrow, intermediate, and broad conception of a democracy divide. For each conception, one side of the divide includes those EU member states that are members of both sets of in-groups, i.e are located at the intersection of the sets for quality of democracy and for RoL interventions. In each of the conceptions, there are also some states that are partially in, as they are members of one of these sets, but not both.

In the narrow conception of a democracy divide (on the left of ), in-group membership requires membership in all the sets for both quality of democracy and RoL interventions. The intermediate conception (middle of ) requires membership in at least three of the five sets for each dimension. In-group membership for the broad conception (right side of ) requires membership in at least one set for both dimensions. The narrowly conceived in-group includes only four states; all of them are western members (Denmark, Sweden, Netherlands, Luxembourg). The intermediate conception includes four eastern members in the in-group (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia), while two western members (Greece and Austria, plus Malta) are not included. For the broad conception, only Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Slovenia, and Croatia are in the out-group.

The different conceptions of intra-EU divides display elements of an East–West pattern, in that the in-group for the narrow conception includes exclusively western member states, and in the broad conception, the out-group includes exclusively eastern members. Yet the patterns certainly do not conform to a clear East–West divide: for any of the conceptions, at least one side of the divide includes both eastern and western member states, and in the case of the intermediate conception, which is arguably the most nuanced description of divisions in the EU, both sides of the divide do. If anything, the patterns resulting from different operationalisations of a democracy divide strongly suggest that when analysing variation in the quality of democracy and attitudes towards RoL interventions, the very notion of a ‘divide’, with its connotation of two distinctive groups, each of which shows strong similarities, is not particularly useful. Instead, we see member states spread along a continuum.

We can use the set-membership in to distinguish several subgroups within the EU (). These sub-groups range from the member states most committed to democracy and its defence, to those least committed, with five separate sub-groups in-between. Group 1 at one end of the spectrum includes those countries that are in the in-group for any of the methods used to identify democracy divisions: Denmark, Sweden, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Group 7, at the other end, is composed of four countries that are always in the out-group: Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Slovenia. All other member states are in-between, and while some are closer to one end, their positions are fairly fluid. Groups 2 and 3 both include eastern members and Group 4 only includes western members. Groups 5–7 are all composed of eastern member states, but the differences between these groups should not be neglected. At the same time, it is important to recognise that provides only a snapshot, and that countries’ membership in the various sub-groups is highly changeable over time.

Table 1. Snapshot of sub-groups of EU member states with regard to democracy.

Conclusions

This article has examined the accuracy of narratives of an intra-EU East–West divide with regard to democracy, in which the western member states outperform the eastern members, and in which the former support, and the latter oppose, interventions by the EU to enforce the rule of law in its member states. The article goes beyond existing analyses, first, by combining analyses of two dimensions of a potential democracy divide that are usually discussed separately: the quality of democracy and attitudes towards RoL interventions. Second, it draws on quantitative indicators for a descriptive comparative assessment across the member states. Third, rather than relying on a single indicator for an assessment with regard to the two issues, the paper combines a range of plausible operationalisations for a more comprehensive assessment of intra-EU democracy divides. It then drew on set-theory to identify different in- and out-groups that constitute intra-EU divides, distinguishing between a narrow, intermediate, and broad conception of the in-groups.

The use of different operationalisations of intra-EU divisions on democracy and the RoL suggests that the results are highly sensitive to the choice of indicators. At the same time, while different operationalisations, and different conceptions of identifying relevant in-groups, reveal to varying extents certain East–West patterns, none fit with a clear regional divide. There are noticeable East–West patterns as the various in-groups of democracy leaders and supporters of RoL interventions are predominantly or exclusively composed of western members and the majority, or even all of the states in the out-groups are eastern members. The narrow conception of the overall in-group, combining both the quality of democracy and support for RoL interventions, includes exclusively western member states, and for the broad conception, the out-group includes exclusively eastern members. These patterns are a reminder that EU membership is certainly no guarantee against democratic backsliding, let alone for an improvement of democracy. Yet these East–West differences notwithstanding, the empirical pattern clearly does not conform to the notion of an East–West divide in which eastern and western members are firmly on different sides of a divide. As indicates, regardless of the conception used to define in-groups, at least one side of the divide includes states from both eastern and western Europe, and in the case of the intermediate conception, which is arguably most representative for intra-EU divisions, both sides of the divide do. Rather than a divide, intra-EU differences on democracy are best seen as a continuum, with several distinctive sub-groups of member states depending on their set-membership according to different conceptions of intra-EU divisions (see ).

To analyse democracy in the EU and preferences towards RoL interventions, a simplistic notion of an East–West divide is therefore unhelpful, and a more nuanced analysis is required. While it is important to acknowledge the existence of East–West patterns in order to analyse which post-communist similarities can create unfavourable conditions for liberal democracy, it is equally important to remain sensitive to intra-regional differences as well as cross-regional similarities. On the one hand, western member states are certainly not immune to backsliding, as not least the cases of Greece or Austria indicate. On the other hand, a failure of democratisation in the eastern member states is clearly not inevitable and it would be wrong to use the notion of an East–West democracy divide to re-evaluate EU eastern enlargement as a policy failure and to caution against further enlargement. Some eastern members are often found among the stronger democracies: Estonia stands out for having attained a level of democracy that is better than most western European member states. Slovakia and Latvia have both made progress after temporary setbacks, even if they have not (fully) regained the peaks that they had achieved after their EU accession. Lithuania maintains a fairly strong position despite a deterioration over the last decade.

Moreover, while it is more fruitful to conceive of intra-EU differences in terms of several subgroups of member states along a continuum, we should also not overstate the extent to which the composition of subgroups is fixed. At one end of the continuum of intra-EU democracy differences is a group of eastern members where democracy is under the most serious threat. It includes not only Hungary and Poland, which tend to be the main focus of the debate, but also Bulgaria, where democracy has steadily declined since EU accession, and Slovenia, where backsliding resulted from more recent government policies. But for other eastern member states, the situation is more fluid. Recent political changes in the Czech Republic, following the parliamentary election in 2021 and the presidential election in 2023, may give reasons for optimism. Similarly, Slovenia may be able to reverse the sharp decline in democracy following the heavy electoral defeat of Janez Janša in the parliamentary elections in April 2022. There were also hopes that Bulgaria may turn a corner following the end of the 12 years in office of Boyko Borisov in 2021. However, the formation of a reformist, yet unstable, government coalition was followed by a succession of snap elections and protracted political crisis.

In sum, rather than a clear-cut divide, it is more helpful to consider intra-EU differences on democracy as a continuum, with a small group of western members at one end and some eastern members at the other, but most member states are in distinctive sub-groups in-between, with fairly fluid positions.

Acknowledgements

For valuable comments, I would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers and Tanja Börzel, Rachel Epstein, and Milada Vachudova.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ulrich Sedelmeier

Ulrich Sedelmeier is Associate Professor (Reader) in International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Notes

1 Of course the terms ‘eastern’ and ‘western’ EU member states are geographically imprecise, but I use them as convenient shorthand that is in line with the language of an East-West divide.

2 I use the following formula: (2021 score x 3 + 2020 score x 2 + 2019 score x 1)/6. The results, i.e. which countries are above or below the EU mean, remain the same when using either exclusively the 2021 score, or the average of the last two, or three, available years.

3 I include Malta and Cyprus in the calculation of the EU average, but report them neither as ‘East’ nor ‘West’ (since they are new members but not post-communist countries). Narratives of an EU East-West divide are curiously silent about whether these two countries are considered ‘East’ or ‘West’. Both countries are below the EU average.

4 I use the same weighted average for 2019–21 as above (see footnote 2).

5 There is an even larger gap in the data between 0.458 and 0.365, but arguably this gap is less indicative of a divide between member states with a good LDI score and those with a poor score, but between those with a very poor score and the rest (which would combine member states with very good scores and fairly poor scores). Arguably, while the distribution of the data suggests that identifying a gap in the scores may be a better indicator of a divide within the EU membership than using a measure of the central tendency, the absence of two fairly homogenous clusters should also caution against the very notion of a ‘divide’.

6 Haggard and Kaufman (Citation2021) also eliminate cases that two of three alternative datasets (Freedom House, Polity, Economic Intelligence Unit) did not code as having experienced democratic regress. They identify sixteen cases of backsliding between 1974 and 2019 globally, including three EU member states: Hungary, Poland, and Greece.

7 While Meyerrose (Citation2020) focuses specifically on new members of international organisations, her measure would also find a decline for most western EU member states.

8 Among the EU member states, they identify Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia as having experienced such a decline.

9 I use three-year average scores (2019–21 and 2004–06, adjusted to their later accession dates for Romania, Bulgaria, and Croatia) in order to capture trends during those periods and to avoid possible distortions through snapshots of two individual years. Moreover, for the 2019–21 average, I weigh the more recent years more heavily to capture better the recent trends (see footnote 2). The results are largely the same as using either an unweighted 3-year mean, or just the single years 2004 and 2021. (The differences are that with an unweighted mean for 2019–21, there is a decline in Malta, and if comparing only 2004 and 2021, then there is a decline in the Netherlands, but not in Sweden).

10 The results are identical for a 5% threshold; if we use a decrease of 4% or more, Germany and Austria drop out of the in-group.

11 This finding also resonates with studies that find significant variation in backsliding across the eastern member states (see e.g. Bakke & Sitter, Citation2022; Bustikova, Citation2019 Dimitrova, Citation2018; Enyedi, Citation2020; Greskovits, Citation2015; Rovny, Citation2023; Vachudova, Citation2020; Vachudova et al., Citation2023).

12 For the liberal component of democracy, the minimum requirement is a score of 0.8 (on a scale from 0 to 1), while for the other three categories, the minimum score is 3 on a scale from 0 to 4.

13 I use the number of annual Reasoned Opinions (ROs) and referrals to the Court of Justice, expressed as a share of the EU mean. The year 2006 as the starting point (i.e. the second full year of membership for the countries that joined in May 2004, with corresponding adjustments for Bulgaria, Romania, and Croatia) ensures that the time lag in processing infringement cases after accession does not bias the data in favour of the newer member states.

14 Busse et al. (Citation2020) further distinguish two positions within the opposition to EU intervention: whether the EU should accept distinct models of RoL albeit within core limits (preferred by the governments of Bulgaria and Slovenia) or whether the EU should fully leave it to the member states to determine how they protect the RoL (preferred by Hungary and Poland).

15 The Policy Intentions Mapping is based on research conducted between March and May 2020 and predates the negotiations of the EU’s RoL Budget Conditionality in December 2020.

16 The voting data on the relevant resolutions is taken from Avdagic and Sedelmeier (Citation2018), which draws on VoteWatchEU.

17 For the combined total of 4334 votes that were either for or against a resolution (excluding abstentions), the mean (and median) of votes in favour is 68% (Avdagic & Sedelmeier, Citation2018).

18 In some countries, two EPP member parties signed the letter (Belgium, Portugal, and Sweden); a Norwegian EPP member also signed.

19 Some member states (Austria, Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Portugal) asked to be included after the letter was released. The text of the declaration published by the Belgian Foreign Minister, Sophie Wilmès, includes 18 signatories, while Politico reports 17 signatories which include Malta but not Cyprus and Lithuania (Eder & Darmanin, Citation2021).

References

- Alizada, N., Cole, R., Gastaldi, L., Grahn, S., Hellmeier, S., Kolvani, P., Lachapelle, J., Lührmann, A., Maerz, S. F., Pillai, S., & Lindberg, S. I. (2021). Autocratization turns viral. Democracy report 2021, University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute.

- Anghel, V. (2020). Together or apart? The European Union’s East–West divide. Survival, 62(3), 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2020.1763621

- Avdagic, S., & Sedelmeier, U. (2018). Voting for punishment: The party politics of sanctioning democratic backsliding in parliamentary assemblies of Regional IOs. Paper presented at the International Studies Association Annual Convention, 4-7 April, San Francisco.

- Bakke, E., & Sitter, N. (2022). The EU’s enfants terribles: Democratic backsliding in Central Europe since 2010. Perspectives on Politics, 20(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720001292

- Bermeo, N. (2016). On democratic backsliding. Journal of Democracy, 27(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0012

- Bohle, D., & Greskovits, B. (2019, August 29). Staring through the mocking glass: Three misperceptions of the East-West divide since 1989. Eurozine.

- Börzel, T. A., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2017). ‘Coming together or drifting apart? The EU’s political integration capacity in Eastern Europe’. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(2), 278–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1265574

- Busse, C., et al. (2020, July 8). Policy intentions mapping. European Council on Foreign Relations.

- Bustikova, L. (2019). Extreme reactions: Radical right mobilization in Eastern Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Cianetti, L., Dawson, J., & Hanley, S. (2018). Rethinking “democratic backsliding” in central and Eastern Europe–looking beyond Hungary and Poland. East European Politics, 34(3), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2018.1491401

- Ciobanu, C., et al. (2019, November 13). Money talks: EU budget negotiations widen East-West divide, Balkan Insight.

- Coppedge, M., et al. (2022). Varieties of democracy dataset v12.

- Dimitrova, A. (2018). The uncertain road to sustainable democracy: Elite coalitions, citizen protests and the prospects of democracy in central and Eastern Europe. East European Politics, 34(3), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2018.1491840

- Eder, F., & Darmanin, J. (2021, June 24). 17 EU leaders sign LGBTQ+ rights letter in response to Hungarian anti-gay law. Politico.

- Enyedi, Z. (2020). Right-wing authoritarian innovations in central and Eastern Europe. East European Politics, 36(3), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1787162

- Gerring, J. (2012). Mere description. British Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 721–746. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000130

- Greskovits, B. (2015). The hollowing and backsliding of democracy in east central Europe. Global Policy, 6(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12225

- Grzymala-Busse, A., & Innes, A. (2003). Great expectations: The EU and domestic political competition in east central Europe. East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures, 17(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325402239684

- Haggard, S., & Kaufman, R. (2021). The anatomy of democratic backsliding. Journal of Democracy, 32(4), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2021.0050

- Henley, J. (2021, November 11). Morgues fill up in Romania and Bulgaria amid low Covid vaccine uptake. The Guardian.

- Lehne, S. (2019, April 11). Europe’s East-West divide: Myth or reality? Carnegie Europe.

- Lührmann, A., Tannenberg, M., & Lindberg, S. I. (2018). Regimes of the world (RoW): Opening new avenues for the comparative study of political regimes. Politics and Governance, 6(1), 60–77. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i1.1214

- Meyerrose, A. M. (2020). The unintended consequences of democracy promotion: International organizations and democratic backsliding. Comparative Political Studies, 53(10-11), 1547–1581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019897689

- Mueller, J.-W. (2014). Eastern Europe goes south: Disappearing democracy in the EU’s newest members. Foreign Affairs, 93(2), 14–19.

- Pop-Eleches, G. (2015). Pre-communist and communist developmental legacies. East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures, 29(2), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325414555761

- Rovny, J. (2023). Antidote to backsliding: Ethnic politics and democratic resilience. American Political Science Review (online first). https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542200140X.1-19

- Rupnik, J. (2019, March 29). East-West: Reality and relativity of a divide. Notre Europe Policy Brief, Jacques Delors Institute.

- Schimmelfennig, F., & Sedelmeier, U. (2020). The Europeanization of Eastern Europe: The external incentives model revisited. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(6), 814–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1617333

- Sedelmeier, U. (2014). Anchoring democracy from above? The European Union and democratic backsliding in Hungary and Romania after accession. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(1), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12082

- Sedelmeier, U. (2020). Enlargement: Widening membership, transforming would-be members? In H. Wallace, M. A. Pollack, C. Roederer-Rynning, & A. R. Young (Eds.), Policy-making in the European Union (8th ed., pp. 440–468). Oxford University Press.

- Slapin, J. B. (2015). How European Union membership can undermine the rule of law in emerging democracies. West European Politics, 38(3), 627–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.996378

- Stanley, B. (2019). Backsliding away? The quality of democracy in central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 15(4), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v15i4.1122

- Vachudova, M. A. (2020). Ethnopopulism and democratic backsliding in central Europe. East European Politics, 36(3), 318–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1787163

- Vachudova, M. A., Dolenec, D., Fagan, A., & Wunsch, N. (2023). Civic mobilization against democratic backsliding in postcommunist Europe. unpublished paper.

- Valášek, T. (2018, September 20). Halting the drift between Central and Western Europe. Carnegie Europe.

- Volintiru, C., Bârgăoanu, A., Stefan, G., & Durach, F. (2021). East-West divide in the European Union: Legacy or developmental failure? Romanian Journal of European Affairs, 21(1), 93–118.

- Volintiru, C., Epstein, R., Fagan, A., & Surubaru, C. (forthcoming). The East-West divide: Assessing tensions within the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy.

- Waldner, D., & Lust, E. (2018). Unwelcome change: Coming to terms with democratic backsliding. Annual Review of Political Science, 21(1), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-114628

- Wilson, J. (2021, June 14). Early signs point to Euro 2020 being a fresh triumph for West v East. The Guardian.

- Zielonka, J. (2019, March 5). The mythology of the East-West divide. Eurozine.