ABSTRACT

Trade policy and negotiations have lain at the heart of the Brexit process. Initial UK trade policy has been characterised by: (1) the need to limit the impact of changes in trading relations (mainly with the EU) to minimise challenges for businesses and the possibility of economic losses; (2) a strong ideological commitment to free trade, and related to that; (3) symbolic and ‘placebo’ actions designed to show that the UK can enact an independent trade policy. Negotiation of free trade agreements (FTAs), thus, became a priority of trade policy. This article explores how approaches to FTAs have evolved, focusing specifically on post-Brexit FTAs with Australasia. Overall, the desire to complete speedy agreements has at times trumped business and societal interests, and precluded the development of a coherent long-term UK FTA vision, revealing the symbolic motivation of being seen as ‘delivering Brexit’ behind the initial years of post-Brexit trade policy.

Brexit formally occurred on 31 January 2020, and was followed by a transition year during which trade and economic relations between the UK and EU continued to operate as if the UK remained in the single market, whilst the terms of the future economic relationship were finalised in the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). Underlying the Brexit process lay the irony of a government espousing free trade ideals, casting itself as ‘Global Britain’ open for business, whilst simultaneously leaving the largest trading bloc and integrated market. Brexit dovetailed in time with broader changes in the international trade environment; US President Trump’s disregard for WTO rules, the covid-19 pandemic of 2020 and the supply chain chaos it generated and ensuing economic contractions, that cast doubts as to the long-term viability and feasibility of the UK’s liberalising free trade policy ambitions.

Against this unfavourable backdrop, the UK has developed the institutional framework to enact an independent trade policy. UK trade policy in the first years of Brexit has been characterised by three key factors: (1) the need to limit the impact of changes in trading relations (mainly with the EU) to minimise challenges for businesses and the possibility of economic losses; (2) a strong ideological commitment to free trade, and related to that; (3) symbolic and ‘placebo’ actions designed to show that the UK could follow an independent trade policy. Unsurprisingly, pragmatism was the order of the day. Thus, the practical negotiation of free trade agreements (FTAs), first with the EU and with other states which had privileged trade relations with the UK through EU FTAs, (and later with other states around the globe for more symbolic reasons) became key priorities of UK trade policy.

Choices in the negotiations with the EU, including the departure from the EU Single Market to have independence of action over migration, trade and regulation, and the subsequent selection of new FTA partners, did not reflect the views of organised business interests (Rollo & Holmes, Citation2020). Neither did they reflect the preferences expressed by large parts of the population, devolved administrations and regional and local business communities across the country, who favoured maintaining EU regulations and close economic integration with the EU (Committee for Exiting the EU, Citation2017; UK Government, Citation2019). Even within Government, there were divergent preferences, with Treasury advocating greater integration with the EU market than Cabinet (Siles-Brügge, Citation2019). Extant literature posits that Theresa May’s Government’s reliance on Brexiteer’s interpretations of ‘sovereignty’, and the prioritisation of this, led to the subordination of the UK’s economic interest in the negotiations for withdrawal from the EU, as reflected in the decision to leave the Single Market and customs union (Trommer, Citation2017; Rollo & Holmes, Citation2020; Siles-Brügge, Citation2019). This was the only option able to satisfy the Government’s ‘red lines’ of ensuring UK control over migration, and avoiding the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice.Footnote1 In subsequent independent trade policy, particularly with new FTAs, key concerns from devolved administrations and certain economic and social groups have also been ignored in favour of rather symbolic actions designed to exhibit sovereignty and independence, and the enactment of a particular vision of Brexit supported by ‘hyperglobalists’ within the Brexit camp (Rosamond, Citation2019). This article draws on public policy literature highlighting the significance of symbolic and ‘placebo’ policies, produced significantly ‘for show’, and to demonstrate ‘action’ in the face of intractable or ‘wicked’ policy problems (Gustafsson & Richardson, Citation1979; Gustafsson, Citation1983; McEwen, Citation2021). My central argument is that the early years of UK post-Brexit trade policy can be explained by the importance for the Government of appearing to, somehow, demonstrate that the UK could have a t a new independent trade policy and could demonstrate positive ‘action’ under Brexit.

My analysis tracks key aims in UK post-Brexit trade policy, and the institutions and practices that have evolved, as well as new FTAs, all of which can reveal priorities of the Government’s trade policy. I focus specifically on UK priorities in new PTAs, which given their recent nature, have yet to be scrutinised by the literature, thus far dominated by econometric projections of trade against the backdrop of Brexit uncertainty (Crowley et al., Citation2018; Graziano et al., Citation2018; Steinberg, Citation2019), explanations of damaging economic Brexit choices centred around the government’s prioritisation of particular concepts of sovereignty (Trommer, Citation2017; Rollo & Holmes, Citation2020), options and challenges around negotiations with the EU (Hestermeyer & Ortino, Citation2016; Baetens, Citation2018), political challenges in Northern Ireland (Kelly & Tannam, Citation2023) and legal complexities of the Northern Ireland Protocol (Gasiorek & Jerzewska, Citation2020; Murphy, Citation2021; Murphy & Evershed, Citation2022; Weatherill, Citation2020).

Drawing on publicly accessible government documents, position papers on trade policy and FTA negotiations, Parliamentary enquiries, it is possible to to identify the priorities of UK trade policy. Comparing these new agreements with existing EU agreements, reveals a clear shift towards more flexible approaches to FTAs. The content of the agreements also provides hints as to the economic sectors the UK Government wishes to support, namely the service sector, especially digital services, and of how far the Government is willing to run counter to the wishes of domestic interest groups in other sectors as well as the preferences of devolved administrations. The analysis suggests a strong political need to show that an independent trade policy, albeit often via symbolic actions and via placebo policies and agreements, is possible. Put simply, the UK Government’s desire to demonstrate the world’s desire to interact with ‘Global Britain’ has been a key driving force behind these FTAs, more so than specific economic gains, or developing a longer-term consensus around future trade policy.

The rest of the article is organised as follows. Section two explains the characteristics of symbolic and ‘placebo’ policies’ (McConnell, Citation2020) and how this is applicable to UK post-Brexit trade policy. Section three briefly considers some of the traditions of a pro-liberalisation trade policy ethos in the UK prior to Brexit. Section four describes the creation of an independent trade policy focusing on institutional arrangements and their implications for trade agreements. Section five outlines the immediate post-Brexit trade policy priorities of the UK, and Section six follows through with an examination of these priorities within the UK’s new FTAs, in particular the ones with Australia and New Zealand. A final section highlights the importance of symbolism in the initial years of UK trade policy.

The importance of symbolic action in policy

Symbols are important in societies, and they are also important for Governments. Indeed, public policy research considering policies as symbols is not novel (Edelman, Citation1971). It has been applied to education policies (Hy, Citation1978), aid policies (Barrett & Tsui, Citation1999), environmental policies (Böhringer & Vogt, Citation2004; Cass, Citation2008), health (Fotaki, Citation2010), anti-crime policies (Marion, Citation1997), but surprisingly less in the area of trade policy, despite recent examples of political leaders declaring the symbolic value of new FTAs.Footnote2 At the conclusion of UK-Australia FTA negotiations, then UK Secretary of State for Trade Anne-Marie Trevelyan declared ‘today we demonstrate what the UK can achieve as an agile, independent sovereign trading nation’ (DIT, Citation2021).

Symbolic policies have been explained by the increasing complexity of problems governments face, and the rise in diffuse multi-level governance across agencies and territorial units, that encourage governments to put in place symbolic or pseudo-policies not genuinely intended to have full effects (Gustafsson, Citation1983). As Gustafsson and Richardson (Citation1979) explain, politicians need to be seen as following the will of the people and governing in their interest. The election slogan ‘Get Brexit done’ was, indeed, a very specific pledge to implement the will of the people which could not simply be forgotten. However complex ‘Get Brexit done’ is in reality, the political imperative is ‘do something!’ Thus,when ‘faced with a particularly challenging problem, politicians cannot address the public to say they have to accept the situation, instead they may enact ‘cynical or placebo’ policies to give the appearance of doing something’ (Gustafsson & Richardson, Citation1979, p. 417). Allan McConnell (Citation2020, p. 958) further refines this by developing a typology of types of policy problamtiques that increase the likelihood of symbolic placebo policies. These are: complex wicked problems, sudden emergence of media firestorms, scandals, crises, public sector underperformance and the appointment of tzars to tackle policy areas.

Brexit trade policy displays these characteristics: the complexity of Brexit and trade policy at a time of increased trade policy contestation and more challenging geopolitical environment where trade interacts with numerous other policies, can be considered as a wicked problem; Brexit unleashed a crisis about future economic relations and performance and, of course, was highly mediatised. McConnell (Citation2020, p. 962) argues that issues with high public visibility, high complexity, high degree of urgency, and where public expectations are that the Government will act, but where the capacity to address the issue is low create ‘policy traps’ where Governments must act but are limited in their capacity to act. In these cases policies will lean towards ‘placebo’ symbolic policies. Brexit meets all these characteristics. As a subset of post-Brexit UK trade policy, the Northern Ireland Protocol issue particularly displays all these characteristics (see Kelly & Tannam, Citation2023). Whilst other post-Brexit trade negotiations do not share all the characteristics of a policy trap: they have been less visible in the media, there was no economic urgency to negotiate FTAs with Australia and New Zealand for example, and the Government had capacity of action, there was, nonetheless, an expectation, particularly amongst Brexiteer factions within the Conservative Parliamentary Party, that the Government would implement Brexit and make it a success. As subsequent sections will demonstrate, producing examples of success becomes an incentive for the Government to engage in policies whose main aim is to symbolically enact Brexit.

Liberalising tradition of UK trade policy

Since the Brexit referendum, Prime Ministers and Secretaries for Trade have vaunted the UK’s free trading traditions. Secretary of State for Trade Liam Fox claimed free trade was in the UK’s ‘DNA’ (Fox, Citation2017) and with its ‘history as a great trading nation’ would ‘forge a new global role’ ‘carry[ing] the banner for free trade’ (Fox, Citation2016). Prime Minister Theresa May’s launch of ‘Global Britain’ as a foreign policy strategy embedded these ideas. ‘Global Britain’ emphasised that the UK ‘continue[d] to be open, inclusive and outward facing; free trading’ (FCO, Citation2018, p. 7). This creates a potent ‘imaginary – one that capitalizes on a collective narrative of mercantilism (Britain as a great trading nation) […] in which political sovereignty and economic power coincide in making Britain great and will enable the country to regain its ‘proper place’ in the world’ (Clarke, Citation2020, p. 143). However, the narrative disguises both the degree of internal contestation of this agenda and exaggerations around the historical myth of the UK as free-trading nation (Reilly, Citation2020). Brexit unleashed a myriad of emotive imaginaries regarding Britishness and Britain’s role in the world (Sykes, Citation2018; Clarke, Citation2020; Rosamond, Citation2019). Even amongst Brexit proponents, nativists’Footnote3 more protectionist visions competed with hyperliberals’ for whom the return of sovereignty to the UK would help to propel the UK’s greater insertion into global capital markets (Rosamond, Citation2019, p. 415). Within Government, too, competing visions for Brexit battled for supremacy, from Treasury’s appeals for a ‘softer’ Brexit predicated on greater ease of trade with close spatial neighbours, to Cabinet’s emotive appeals to free the UK from ‘over-regulation’ and bring its economy closer to its ‘kith and kin’ in the Anglosphere, deepening the UK business model, and abandoning what they perceived as EU over-regulation (Siles-Brügge, Citation2019, p. 422). Although more liberal global imaginaries eventually crystallised, as subsequent sections show, there is no overwhelming consensus in the country regarding trade policy, and it is the institutional architecture for trade policy, privileging the executive branch that has enabled the pursuit of a trade policy based on a ‘hyperliberal’ imaginary of the UK.

As an EU member, the UK was considered as part of a core group of like-minded member states (Nordic states, Netherlands, UK) supporting free trade (Young & Peterson, Citation2014, p. 35). The liberalising ethos embedded in EU trade policy meant the UK agreed with broad policy lines and was less likely to be outvoted in trade policy than other areas (Hix et al., Citation2016). The UK supported EU trade policy and was able to upload its preferences in trade to the EU level. The House of Common’s European Scrutiny Committee had the right since 2010 to challenge European Commission negotiation mandates, but it did not use it, even in the case of the controversial Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations with the USA (Zimmermann, Citation2019, pp. 37-38).Footnote4 David Cameron’s renegotiated conditions for UK’s membership of the EU prior to the referendum actually included energising negotiations with the US (European Council, Citation2016, p. 10). Given these precedents, it is not surprising that post-Brexit FTA policies display some degree of continuity with Conservative Government’s liberalising preferences on trade whilst in the EU, especially as the lack of prominence of future trade policy in Brexit referendum debates (Garcia, Citation2020, p. 353) left trade policy undefined. Early post-referendum trade policy has been shaped by the decision to leave the EU’s single market to recapture a particular understanding of sovereignty (freedom of EU regulation and legislative control) that united both ‘nativist’ and ‘hyperglobalist’ Brexiteers.Footnote5 In a sense initial ‘trade policy’ was as much about holding together the Brexiteer factions as it was about trade.

Post Brexit Trade policy priorities

Trade policy directions since the referendum have been determined, as explained above, by capture from a particular Brexit imaginary. However, the immediate enactment of this ideologically-driven policy has been tempered by pragmatic considerations regarding the management of the fall-out from Brexit. Initial priorities related to the legal requirements for independent action at the WTO, the re-organisation of the relationship with the EU, and minimising disruption to other privileged trade relation governed by EU trade agreements. These imperatives and creating the institutional capacity to manage these were at the forefront of the Department of International Trade (DIT’s) agenda as it was established in 2016, alongside a Secretary of State for Trade. It is beyond the scope of this article to flesh out the social and institutional dynamics that were generated through the creation of a UK trade policy. However, it is important to delineate briefly some of the key milestones in its evolution, and to recall that as with Brexit, where no one option was universally favoured nor viewed as legitimate (Hobolt et al., Citation2022) so it was with future trade and FTAs.

The 2017 White Paper on Future UK Trade Policy promised an inclusive trade policy where devolved administrations, stakeholders and Parliament would contribute to trade policy and future negotiations. It emphasised the importance of UK trade policy contributing to sustainable development, high standards and respecting values (UK Government, Citation2017). This dovetailed in time with a detailed proposal from businesses (including CBI), trade unions and civil society (Trade Governance Model that Works for Everyone) published in response to Government consultations, which united groups often on opposite sides of trade policy debates (Trade Justice Movement, Citation2018). This model advocated for a trade policy that ensures consensus-building (through stakeholder participation at all stages), transparency, scrutiny (in Parliament, with votes), and a holistic approach to trade (including credible mitigation plans, and labour and environmental objectives) (Trade Justice Movement, Citation2018). By contrast, the White Paper was vague on how participation and scrutiny would occur. The Trade Act was more concerned with creating the institutional structures for trade policy to be enacted (Trade Remedies Authority to interact with the WTO), than dramatically altering UK policy-making traditions or the Westminster model.Footnote6 From an institutional perspective, rather than innovating, existing policy practices were perpetuated. Participation of stakeholders was included through the traditional system of Department consultations, and Parliamentary Select Committee enquiries (in the case of trade, of the new International Trade Committee in the House of Commons, and for FTAs also the International Agreements Committee of the House of Lords). DIT’s Strategic Trade Advisory Group (STAG) comprising business, trade union and civil society representatives, and a series of complementary Expert Trade Advisory Groups (ETAGs) providing advice on specific sector and thematic issues afforded additional opportunities for stakeholder involvement, although their membership has been criticised for a dominance of industry representatives (van Schalkwyk et al., Citation2021, p. 7).

The role of Parliament and devolved administrations in scrutinising trade policy and FTAs is governed by the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act (CRaG). Whilst this ensures Parliamentary scrutiny, Parliament has no powers to veto a FTA, only to delay it. To a degree, therefore, granting Parliaments scrutiny power has more than a tinge of placebo about it. Indeed, Parliament has complained about timeframes, and delays from DIT stymieing its scrutiny processes, and has secured agreement from Ministers to better facilitate scrutiny, but concerns remain over the ability to fully scrutinise Government trade policy and FTAs, especially in the absence of meaningful votes on the matter (ITCa, Citation2022, pp. 24–25). This is all the more remarkable as other Parliaments, including the European Parliament, have genuine ratification powers and vetoes over FTAs. Devolved administrations have also voiced concerns over trade policy. CRaG clarifies that certain policies (agriculture, fisheries, labour) are the jurisdiction of devolved administrations. Given how trade policy and FTAs interact with these policies, devolved administration involvement in trade policy is necessary. Whilst they can participate in inquiries, and make their views known to the central Government through the Joint Ministerial Committees (JMC), they have no right to participate negotiations, nor a role in ratification processes (van Schalkwyk et al., Citation2021, p. 6). Their attempts to grow their influence have been thwarted by the weakness of these institutional arrangements and Government’s desire to maintain control (Eiser et al., Citation2021). Other Government departments, are also involved in trade policy (e.g., Agriculture, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office). DIT coordinates cross-departmental collaboration, especially with the FCDO in relation to negotiation of FTAs, which serve to operationalise ‘Global Britain’, and in relations with developing states through the Joint FCDO/DIT Unit on Trade and Development (DIT, Citation2022a). As occurs in the trade policies of all states, different Departments, regions, and groups have different priorities. In the UK, the particular architecture that has been established guarantees a pre-eminent role for the executive in trade policy, the ability of stakeholders to make their views known notwithstanding. As mentioned earlier, within the executive there were also divergent position on Brexit priorities. However, once a decision was made to proceed with departure from the EU Single Market, and commit to the ‘Global Britain’ agenda, the concentration of executive power in trade policy facilitated the permeation into trade policy of the pro-free trade agenda of ‘hyperglobalist’ Brexiteers and the apparent pursuit of independent trade policy.Footnote7

An initial action operationalising UK trade policy was the UK’s Global Tariff published in May 2020. This signalled to the world a more liberal approach from the UK (Gasiorek & Magntorn Garrett, Citation2020), in line with ‘Global Britain’. Agricultural tariffs remained similar to the EU’s, in part due to pressures from domestic producers (AHDB, Citation2020). Government’s agreement to support agriculture, and the pragmatic need to retain some incentive for future FTA partners to negotiate with the UK, explain this limitation on the free-trade agenda. Indeed, responding to lower tariffs in an earlier draft, Canada suspended negotiations to ‘roll-over’ their trade agreement claiming there would be little merit if the same minimal tariffs were on offer to all states already (Lowe, Citation2022). The Global Tariff initiative can be seen as a symbol of independent trade policy and the Brexit ‘hyperliberal’ vision for trade policy, that is then tempered by the realities of international trade negotiations and positions of partners.

FTAs became a key priority for DIT. The Brexiter wing of Government had made FTAs a potent symbol of the benefits of Brexit, to counter appeals by those favouring a ‘softer’ Brexit, and who were pointing to trading losses. Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson extolled the virtues of ‘be[ing] able to do new free trade deals with countries around the world’ emphasising countries ‘[were] already queuing up’ (Politico, Citation2017). Initial UK FTAs did not, however, represent that independence. Brexit meant the end of application of FTAs with third parties that the UK had subscribed as an EU member. To prevent additional business disruptions, DIT set about negotiating so- called ‘rolled-over’ agreements. To expedite matters, existing EU agreement texts were retained with minor changes to reference UK institutions and agencies and to replace EU tariff rate quotas with some more appropriate to the size of the UK market, and adapt rules of origin to qualify UK content in products.Footnote8 Facing time constraints, a pragmatic approach was adopted eschewing opportunities to imprint a UK approach. Johnson’s vivid symbolism of countries ‘queuing up’ was a far cry from pragmatic realities. Indeed, other states took advantage of the situation to extract additional concessions from the UK. Japan, for instance, wanted to renegotiate aspects of the existing agreement with the EU and managed to gain improved access to the UK for vehicles, as well as mutually agreed improvements on e-commerce and financial services (Morita-Jaeger, Citation2020), and Chile obtained a more generous quota for sheep meat exports. Although these states also wished to avoid disruptions for their business trading with the UK, they felt less pressured than the UK, as the UK was facing disruptions to business with over fifty partners, not just one. Entering the world of international trade negotiations, the UK was discovering that other states were willing to take advantage of the time pressures the UK faced.

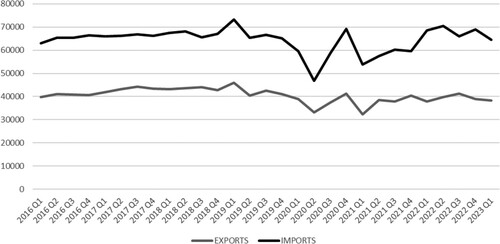

The negotiation of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU, tied to the Withdrawal agreement,Footnote9 was an immediate priority for DIT, to minimise harm to the economic relation. As shows, even with a TCA, UK-EU trade in goods, contracted immediately after the end of the transition period in January 2021. Although both imports and exports have recovered since then, trade remains lower than pre-Brexit and EU imports into the UK have bounced back better than UK exports to the EU, as the UK has been the slowest G20 economy to recover from pandemic trade contraction of 2020 due to the impact of Brexit (UKICE, Citation2023). In terms of services the relationship with the EU has also suffered, but to a lesser extent, given the absence of customs procedures, and UK competitiveness in exports. In 2020 UK service exports to the EU dropped to €166 billion from €179 in 2019, but rose to €175 in 2021 (European Commission, Citation2022a).

Figure 1. UK-EU Trade in Goods (in £10,000,000). Source: ONS (Citation2023) series JIM7 & JIM8.

The drop in UK-EU trade due to the new relationship has been analysed elsewhere (Fusacchia et al., Citation2022; Freeman et al., Citation2022; Bailey et al., Citation2023) as has fallout from disruptions on the UK economy (Office for Budget Responsibility, Citation2022). What is relevant for this article is how the challenge of this relationship was animated by the ideological desire to perform Brexit. In leaving the Single Market and Customs Union, to be able to enact the independent trade policy and FTAs with third parties that had become integral to the Government’s Brexit vision, the UK prioritised this aim, over economic interests (Rollo & Holmes, Citation2020) and the challenges that this choice would entail for Northern Ireland’s delicate governance arrangements (see Kelly & Tannam, Citation2023). This created a ‘Brexit trilemma’ (Kelemen, cited in Dooley, Citation2023, p. 807), where Government had to reach an agreement that would see the UK leave the Single Market and Customs Union, while avoiding either a ‘hard border’ in Ireland or down the Irish sea. Theresa May’s initial version of the Northern Ireland backstop, which would have created a temporary customs union between the UK and EU, until technologies were in place to permit border and customs controls between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland without a need to erect a physical border,Footnote10 did not prosper in a divided Parliament, given Brexiteer opposition as this would curtail the vaunted UK trade independence and future FTAs.

Boris Johnson’s version, the Northern Ireland Protocol, enabled the UK to subscribe independent FTAs. However, to prevent a border on the Irish isle, it created an ambiguous situation where Northern Ireland was simultaneously part of the EU and UK markets, and where EU regulations relating to products continued to apply there (Barnard, Citation2021). This enabled Northern Ireland to benefit from future UK FTAs, however, to avoid this becoming a backdoor to the EU market, goods coming into Northern Ireland from Great Britain or elsewhere (except the EU) would have to identified and duties collected for these, and safety checks for agri-food products would be required, de facto creating a border between Northern Ireland and Great Britain to comply with EU single market rules. Complications, and delays instigated by these new measures led to wide-spread rejection of the Protocol in Northern Ireland, especially amongst unionists, and in the UK Government (Marshall & Sargeant, Citation2022). This visible fragmentation of the UK, and regulatory constraints on UK action, ran counter to the Brexiteer narratives of regaining control and sovereignty, and was deeply resented. David Frost, the UK’s chief Brexit negotiator, tried to shift blame over the fallout from implementation, by claiming this was signed ‘under duress’ without full British independence (O’Toole, Citation2022).

Contesting the Protocol, the UK Government published a Command Paper in July 2021 calling for a renegotiation of the Protocol having previously breached some of its terms by unilaterally extending the grace period of non-application of checks, leading the EU to start infringement procedures against the UK. Lack of progress in bilateral talks, given the unresolved challenges presented by the ‘Brexit trilemma’, the EU’s need to protect the legal integrity of its market, and the UK’s Government exercise of a particular type of sovereignty, understood as independence from constraints (see Gammage & Syrpis, Citation2022) did not encourage successful negotiations on how to resolve the technical difficulties arising from the implementation of the Protocol (see UKICE, Citation2022; Neville et al., Citation2022). In June 2022 the UK Government proposed a Northern Ireland Bill to unilaterally change the terms of the Protocol, eliminating some of the EU imposed constraints (inter alia removing European Court of Justice involvement in dispute, extending UK tax regime to Northern Ireland, allowing firms to choose if they apply EU or UK standards, and green and red lines at customs to facilitate movement of goods) (UK Government, Citation2022a). Responding to this, and to the UK’s failure to provide the relevant data to the EU of goods entering Northern Ireland, the European Commission resumed legal infringement proceedings against the UK (European Commission, Citation2022b). The start of Rishi Sunak’s premiership in October 2022 moderated the UK’s tone. ‘Following Liz Truss’s short and turbulent premiership, Sunak had concluded that he could not risk a trade war with the EU amid a cost-of-living crisis’ (Murray & Robb, Citation2023), and concluded a revised agreement with the EU known as the Windsor Framework. The Framework tackles the technical problems arising from the implementation of the Protocol. It creates green lanes for products staying in Northern Ireland, red lanes for those that might later enter the EU, facilitates customs-procedures for trusted traders, allows UK VAT and excise duties to apply in Northern Ireland, allows pet travel, and loosens some of the requirements around agri-food. It also permits medicines with UK authorisation to be distributed in Northern Ireland. The Framework also introduces a ‘Stormont brake’ in an attempt to tackle the challenges that may arise in the future as greater regulatory divergence between the EU and UK gradually occurs, both as a result of potential UK changes to regulations inherited from the EU, or as a result of passive divergence where the EU modifies its regulations and the UK does not. The Stormont brake enables forty Legislative Assembly members ‘to stop the application of amended or replacing legal provisions that may have a significant and lasting impact on everyday lives of communities in Northern Ireland’ (UK Government, Citation2023, p. 22). Although it remains unclear how exactly this will work and whether the agreement will resolve the governability problems of Northern Ireland (where the DUP have refused to engage in the power-sharing arrangements over the Protocol) (see Tonge, Citation2022), ‘progress comes in the form of process’ and the ‘commitment to managing challenging through the Withdrawal Agreement’s technocratic committee systems’ (Murray & Robb, Citation2023, p. 22), rather than the belligerent approach adopted by Johnson’s Government.

The Northern Ireland challenge in Brexit displayed the characteristics of policy traps that encourage symbolic or placebo policies. It was a complex problem, had visibility, was highly politicised, and an urgent problem that required action. Within the international legal regime established by the Withdrawal Agreement, UK government action was limited, as any change of procedures would need to be agreed with the EU within the joint committee of the Agreement. In pursuit of Johnson’s Government’s particular understanding of sovereignty, the Government choose to act unilaterally, and risk worsening relations with the EU as well as further economic damage. The aim was, of course, to force the EU to renegotiate the Protocol, so it cannot be said that this policy was completely a placebo policy not intended to have any effect at all. However, it does show (as during the Brexit negotiations) a willingness to sacrifice economic interests, to pursue and perform a particular vision of Brexit. The suggested Northern Ireland Protocol Bill was a clear act of symbolic enactment of Brexit and UK independence, especially as it defied the EU.

The relationship with the EU and ‘rolled-over’ FTAs, were immediate consequences of Brexit. However, the symbolic cornerstone of post-Brexit trade policy has been the negotiation of completely new FTAs, not incremental changes. The much-vaunted FTA with the USA, the only one that could generate economic gains to offset some Brexit losses, does not feature in the near-term horizon. President Trump’s administration published objectives that did not match UK needs. For example, US objectives included provisions to facilitate GMO products exports (eliminating labelling requirements and particular scientific approaches to risk assessment) (USTR, Citation2019, p. 2), but the UK has a more restrictive regime, and Scotland is opposed to cultivation of GMOs (Scottish Government, Citation2022). US objectives also include US approaches to intellectual property including in relation to geographic indications (GIs) for agricultural products, which would run counter to the UK’s own regime, and commitments with the EU under the TCA, and in the area of medicine patents could potentially contradict the UK’s own objectives, specifically the commitment to not increasing prices for the NHS and preserving UK standards (DIT, Citation2020, p. 11). Unsurprisingly, little progress has been made in negotiations since 2020, beyond replicating sectoral agreements that already existed with the EU (e.g., Agreement on wines, Mutual Recognition Agreement for technical products). President Biden, for his part, has adopted a minimalist US trade policy, avoiding FTAs that require Congressional support, and prior to the Windsor Framework clarified that the US would not negotiate with the UK if it breached its international legal commitment in Northern Ireland (Politico, Citation2022). With little prospects for a PTA with the US, the UK looked to other countries, focusing initial efforts in agreements of little economic significance with Australia and New Zealand, from which we can start to glean future UK trade policy priorities.

FTAs with Australia and New Zealand: placebo policies in action?

The agreements with Australia and New Zealand are significant test cases for UK trade policy. An analysis of their content can reveal how far the UK is willing to deviate from EU standards and practices, which sectors the UK government seeks to benefit through FTAs, and which it is less supportive of. It also enables an exploration of how the government operationalises the ideals outlined in the White Paper on the Future of UK Trade Policy and the Trade Act.

These FTAs are interesting because even DIT’s own impact assessments suggested extremely limited economic gains from the agreements. The impact assessment for the agreement with New Zealand projected growth in GDP by 0.03 percent by 2035 and admitted this was subject to great variation (DIT, Citation2022b, p. 6), and the impact assessment for the Australia FTA projected GDP growth of 0.08 percent (DIT, Citation2021, p. 24). They also acknowledged the likelihood of losses for the UK’s agricultural sector (DIT, Citation2022b, p. 32; DIT, Citation2021, p. 30). Limited scope for economic welfare gains suggests that the value of the agreements lay in the symbolism of performing independent trade policy.

The first striking feature of both agreements is that the length, language use and chapter headings deviate from the EU’s standard model, which is retained in the EU-UK TCA, and UK ‘rolled-over’ agreements. However, rather than a UK model, what transpires is that they are formatted in the way that these South Pacific states usually format their own PTAs. EU PTAs deal with matters related to labour and environmental matters in chapters titled Trade and Sustainable Development. In new UK agreements these matters appear as separate Labour Chapters, Environment Chapters. These chapters include the usual non-regression clauses and references to ILO conventions and environmental agreements to which the contracting parties are already parties, rather than demanding ratification as EU agreements do. In contrast to EU PTAs, labour and environmental chapters are legally-binding and subject to the general dispute settlement mechanism of the trade agreement.Footnote11 Nonetheless, the provisions on labour have been considered ‘minimalist’ and a ‘missed opportunity’ to craft the ambitious high standards and democratic rules heralded in ‘Global Britain’ documents (Katsaroumpas, Citation2023, p. 3), suggesting the predominance of speed and symbolism over and opportunity to craft a considered UK approach to FTA design.

Trade in goods is an area where substantial differences appear in these FTAs with respect to the EU’s approach. The tariff schedules are liberalising, eliminating most tariffs, including in agriculture. Even for sensitive products like beef and lamb, the UK agrees to reduce and eliminate duties within a fifteen year period (UK Government, Citation2022b, p. 2A-8). By contrast, the EU’s FTA with New Zealand retains tariff rate quotas indefinitely (European Commission, Citation2022b, pp. 3–4). UK agreements reflect Australasian offensive objectives in negotiations. Within the UK, the National Farmers’ Union has voiced concerns that tariff rate quotas have been set at levels that are too generous and exceed past trade (Webb, Citation2022, p. 52), and even the Government’s own impact assessment have revealed that British agriculture is expected to be worse off under the agreement (DIT, Citation2021; DIT, Citation2022b). This has also led former Environment Minister, George Eustice to savage the agreement with Australia and former Secretary for Trade Liz Truss’s role in negotiating it at the House of Commons debate on the FTA in November 2022, claiming the UK gave away far too much for too little (BBC, Citation2022). The Scottish Government also sent a scathing letter to the Trade Secretary criticising agricultural concessions made to New Zealand and demanding the Government pay attention to its own impact assessments and mitigate losses of communities that are disadvantaged by UK Government trade deals (McKee & Gougeon, Citation2022). Brexit has led to some erosion of perceptions that agriculture requires special treatment (Greer & Grant, Citation2023, p. 19), but it was the eagerness to complete a PTA and perform an independent trade policy, combined with the reality of being a middle power and less attractive market outside of the EU, account for the lacklustre gains for the UK – at least in agriculture. These agreements, therefore, are certainly not transformative in terms of UK trade policy and at worst might be seen as somewhat costly placebos in that the specific interests of domestic and, more importantly, regional groups were set aside in the interests of demonstrating the viability of Brexit independent trade policy.

Other key differences are reflected in the Rules of Origin (RoOs). These agreements have far simpler RoOs and procedures for calculating these, that based on Australasian practices. It is important to note, that in the UK’s Global Tariff which simplifies inherited EU schedules, DIT showed a willingness to minimise traditional barriers in trade of goods and agreeing to simpler RoOs happily marries Australasian and UK interests within the ‘hyeprliberal’ Brexit camp that dominated the early years of post-Brexit policy and the desire to demonstrate UK distancing from the EU.

In areas where controversy was likely to arise given discrepancies between UK procedures (inherited from the EU) and Australasian approaches, such as Geographic Indicators (GI), the UK has not persuaded its partners to alter their approach. Rather than prolong negotiations, in order to reach an agreement, the UK prioritised speed and the conclusion of an agreement that would serve as a symbol of its capacity for independent trade policy. Instead of pursuing accommodation of the UK GI system, the agreement delays negotiations on GIs until five years after the implementation, and even includes a paragraph expecting the differences to be resolved within the agreements that Australia and New Zealand were negotiating with the EU (UK Government, Citation2021, Art. 15.32; UK Government, Citation2022b, Art. 17.33).

Digital services is perhaps the most interesting aspect of UK new PTAs, and one with a high degree of symbolism in terms of enacting the distancing from the EU advocated by the Brexiteer ‘hyperglobalist’ camp. Along with specific digital trade agreements signed with Singapore and Japan, these FTAs reveal deviation from the EU’s model of digital trade governance. This shows the Government’s willingness to depart from the EU’s template and embrace US-style approaches with the aim of acceding to CPTPP, which contains Digital commitments similar to those enacted with CPTPP members, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Japan, and signals to others UK trade independence.

These agreements commit the parties to maintaining open digital markets, reducing red tape, work towards mutual recognition of digital signatures and electronic authentication, working on single window systems for businesses to interact with government, ban unjustified restriction on data flows, ban the introduction of new unjustified data localisation requirements, allow the free flow of financial data, prevent the forced transfer of intellectual property, source code and cryptographic algorithms. They also encourage cooperation between the parties on emerging technologies in the digital economy including fintech, regtech, and in the DEA with Singapore, for the first time, cooperation in lawtech in legal services is also included.

Increasingly, FTAs include provisions for the parties to ensure that they maintain ‘adequate levels of data privacy protection’. UK agreements include this wording. However, new UK PTAs do not go as far as EU agreements, where in recent years, the EU has been pioneering an approach asking parties to take account of international standards in their domestic data privacy regulations (Fahey, Citation2021, p. 3). Following the adoption of a clearer regime based on the protection of data privacy through the GDPR, the EU has taken a cautious approach to data flow provisions in PTAs. The Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with Canada has no data flow provisions, and the EU also expressed concerns over other parts of the agreement and their potential to impact data flows (e.g., subjecting data sharing pertaining to temporarily transferred employees to the parties’ domestic data and privacy protection laws) (Fahey, Citation2021, p. 6).

The UK’s more liberal approach in digital trade is significant and responds to the ‘hyperglobalist’ visions of Brexit, with flexible approaches to regulation. As a services-based economy, with ambitions to become a global hub for new digital services, especially finance, freer data flows, fewer data localisation restrictions and applying UK privacy rules to service foreign markets can be beneficial to UK businesses. It may also facilitates them finding new post-Brexit markets, something potentially easier for services operating in the digital space, than for businesses operating in trade in goods, where transport and distance matter. The approach for this sector aligns longer-term UK economic growth aims and sectoral support with UK trade policy. In terms of broader post-Brexit policy, the shift sends powerful signals to partners, in particular CPTPP members and the US. It signals the UK is willing to accept CPTPP provisions, many of which were modelled on US preferences (see Dent, Citation2023). It also signals to the US, that in any potential future negotiation the UK (at least under the Brexiteer Conservative Governments) would be willing to consider US approaches to digital trade, and potentially other areas as well. Indeed, these agreements were considered ‘stepping stones’ to accession to CPTPP, and many chapters (technical barriers to trade, labour, transparency and anti-corruption, on state-owned enterprises and monopolies, and large parts of the environment chapter) are identical to the text in CPTPP. The key criterium for accession to CPTPP is demonstrating compliance with its standards and rules (Art.30.4 CPTPP, Citation2019), and with these FTAs the UK signalled that. In February 2021 the UK applied to join CPTPP and successfully concluded negotiations in March 2023. Ideologically, this liberal approach fits in well with the post-Brexit position of the UK as a global free-trading nation that is open for business as declared in the FCDO’s ‘Global Britain’ memorandum, and coalesces with the ‘hyperglobalist’ vision of Brexit rejecting EU rules and advocating for low tax and deregulated ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ economy.Footnote12 However, this is a contested vision within the UK. Whilst there was general support for these agreements and CPTPP, submissions to inquiries (from business, devolved administrations and civil society) all highlighted, first and foremost, the need to resolve the relationship with the EU, in a way that ensured as much trade continuity as possible (i.e., a softer Brexit than what eventuated). Submissions also warned of the potential of jeopardising trade with the EU through CPTPP accession, in particular exposing the UK to losing the EU’s adequacy decision permitting data flows and enabling digital trade, and fears over losing European patent recognition, or through acceptance of lower standards (House of Lords, Citation2021). Whilst it is possible to be in CPTPP and have data privacy adequacy decisions from the EU (like Japan), the UK will have to navigate future independent regulatory changes carefully to ensure that they simultaneously meet commitments in CPTPP and the TCA, given that the EU remains the UK’s top economic partner. Rushing to accede to CPTPP, on others’ terms, and to conclude FTAs with Australia and New Zealand, without crafting a thought-through UK trade policy and potentially jeopardising other trade and business interests (e.g., with the EU), demonstrates the Government’s impulse to be seen as delivering on Brexit. These agreements with states that could not be further form Europe serve as a potent symbol of post-Brexit independence.

Above all, the agreements with Australia and New Zealand, and accession to CPTPP, which whilst having more economic potential remains limited (Gasiorek et al., Citation2021) given that only 7% of UK trade is with these states (Rollo and Holmes, Citation2020, p. 536), serve to symbolically perform Brexit, and signal the UK’s ability to enact an independent trade policy. The content of the agreements demonstrates greater flexibility in the UK’s trade policy and the absence of a FTA template, as compared to the EU, as was expected given the preferences of the Government. The content, and concessions made on agriculture also reflect the direction UK trade policy will take, and the Government’s choice of sectors to support through trade policy (finance, technology, digital, services sectors), and willingness to act without seeking a broader consensus on trade policy within the country.

In the case of these new FTAs, there was no urgency, no specific public demand that required action, or visibility of these matters. In and of themselves, these new FTAs do not explicitly display the characteristics of a policy trap. However, if we take them within the broader matter of Brexit, post-Brexit trade, and economic decline, which was complex, urgent and highly visible, and not easily resolvable through any Government action, we can see the characteristics of a policy trap. In this case, FTAs of minimal economic gain, but achievable, can be interpreted as symbolic and even placebo policies intended to demonstrate Government capacity and decisive action in the face of sceptics and changing public attitudes to Brexit with polls suggesting a majority believing Brexit was a mistake (The Guardian, Citation2023).

Conclusion

Initial post-Brexit UK trade policy has become a locus for the Government to perform a particular vision of Brexit supported by hyperglobalists in the Brexit camp. The enactment of an independent trade policy carried important symbolism for this group. As this article has shown, the early years of Brexit displayed characteristics of a policy trap, given the extreme complexity of negotiating Brexit, dealing with the economic fallout, the complicated Northern Ireland Protocol issue, the urgency and visibility of these matters, the expectation that the Government would act, and the limited capacity for action given the challenges and need to negotiate with others. In this context, the approach to post-Brexit negotiations and new FTAs, can be explained as a symbolic or placebo policy (McConnell, Citation2020) as a way of escaping the trap, and symbolically performing Brexit and independence, even at the cost of economic self-interest (Rollo & Holmes, Citation2020), and failing to create a consensual longer-term vision for UK trade policy.

Early years of UK trade policy have been characterised first, by the complicated relationship with the EU through the negotiation of Brexit, the subsequent TCA, and the convoluted path to resolving the practical complications arising from the Northern Ireland Protocol and the challenges it posed to trade between Northern Ireland and Great Britain. The Windsor Framework of 2023 should ease these practical problems through innovative solutions (separation of goods destined only to Northern Ireland, permissibility of goods applying UK standards), and above all through a commitment to resolving frictions within the joint committees created by the TCA. Secondly, the need to ‘roll-over’ pre-existing FTAs to which the UK was a party. Thirdly, the presentation of an independent approach through new FTAs with Australia and New Zealand, and accession to CPTPP. The latter, however, do not reflect key priorities of UK businesses, society or devolved administrations. These groups were far more concerned with achieving a softer Brexit guaranteeing continued market access to the EU, and ensuring that no future FTAs jeopardise the relationship with the EU through the implementation of incompatible regulations. In these new agreements, the UK has shown its willingness to depart from EU FTA models, exhibiting its independence, but it has not presented a UK model. Rather than seek to create a national consensus and strategy around future trade policy, the Government has prioritised the demonstration of its capacity to enter into new agreements. Despite internal contestation of aspects of trade policy, the specific institutional arrangements that have been put in place concentrate trade responsibilities within the Executive, facilitating the Government’s ability to negotiate and enact trade policy. As promised in the 2017 White Paper, extensive consultation with devolved administration, Parliament and stakeholders occurs. However, eschewing examples from other jurisdictions where sub-national governments participate in trade policy (Paquin et al., Citation2021), and where Parliaments can vote and veto FTAs, devolved administrations and Parliament are in practice denied strong roles in decision-making on FTAs. This was particularly important to the Conservative Government as a way of demonstrating its post-Brexit effectiveness, and of performing the mission of ‘Global Britain’. It is also critical symbolically to demonstrate Britain’s desirability and discursively provide business with alternatives to the EU market in an attempt to distract attention from well-documented Brexit economic losses (Latorre et al., Citation2019; Portes, Citation2022). Nonetheless, the absence of a consensus could complicate the implementation of FTAs and create domestic frictions within the UK market and polity, especially as new FTAs indicate the Government’s willingness to side-line concerns from agricultural producers (often concentrated in particular regions), leading Scottish Ministers to express their intense dissatisfaction with these (McKee & Gougeon, Citation2022).

New FTAs reveal that the UK government lacks a particular consistent FTA model. In its desire to demonstrate the independence from the EU, the UK has sought, thus far, to conclude negotiations at haste, selecting partners, not on the basis of economic welfare gains, but on likelihood of success. New FTAs do contain interesting innovations (e.g., chapters on animal welfare with New Zealand), and a slight shift in digital chapters towards provisions to enhance cross-border digital trade. Although the provisions are similar to those in other recent agreements (including EU ones), there is a departure from the EU’s strong concerns over privacy. This matters, both in terms of aligning trade policy with aims to bolster the digital economy, supporting financial and legal services industries in the UK, as well as signalling that the UK is ‘open for business’ as Global Britain discourses claim, and willing to come closer to other regulatory approaches than the EU has been. It is not a surprising development given the weight that 'hyperglobalist' Brexiteer factions in the Government placed on freedom from the perceived over-regulation of the EU. The longer-term challenge for the UK will be to balance regulatory commitments in different FTAs, with regulation changes in the UK and their impact on trade and economic relations with the EU within the TCA. States around the globe routinely do this, but it reinforces the reality that trade relations, even within FTAs, are subject to continued negotiation. Under Rishi Sunak, the UK Government is taking a less aggressive stance towards the EU, as testified by the Windsor Framework, and has even decided to replace the sunset clause in the EU Retained Law Bill that would see thousands of pieces of legislation and regulations the UK inherited from the EU revoked at the end of 2023, with a list of 600 laws that the Government wishes to amend (BBC, Citation2023). It is too soon to know the impact those legislative changes will have, but the more restraint approach signals that a normalisation of relations with the EU and new FTA partners may be possible.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the anonymous reviewers and editors for their constructive criticism and very helpful comments. Special thanks to Jeremy Richardson for his valuable suggestions and feedback on earlier versions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maria J. Garcia

Maria Garcia is senior lecturer and head in the Department of Politics, Languages and International Studies at the University of Bath.

Notes

1 On the various Brexit options available see Hix, Citation2018; Doherty et al., Citation2017; Fossum & Graver, Citation2018. On Brexit negotiations see Figueira & Martill, Citation2021; Schnapper, Citation2021; McGowan, Citation2017.

2 Former EU Trade Commissioner noted on conclusion of the EU-Vietnam FTA in 2019 the FTA ‘sends a very powerful signal that says ‘we believe in trade’ (Euractiv, Citation2019).

3 Rosamond uses nativists to refer to groups within the Brexit camp whose main concern was limitation of migration, and retuning to a more closed UK, with industrial policies in support of development in more deprived parts of the country. Hyperglobalists refers to the groups for whom the EU represented a constrain against enabling pro-business and pro-capital regulatory changes in the UK to further its role in global capitalism. Rosamond (Citation2019) argues it was the temporary coalition of these groups that delivered the Brexit referendum success.

4 TTIP negotiations generated concerns amongst civil society groups who feared that the inclusion of investor-state dispute mechanisms in these agreements would facilitate multinational suing EU states over health and environment regulations (see Duina, Citation2019; De Bièvre et al., Citation2020).

5 Zappettini (Citation2019) shows how ‘Global Britain’ was discursively used as a way of trying to create some unifying (if diffuse) meaning of Brexit that would be acceptable to various factions with Prime Minister May’s Government.

6 Diamond (Citation2023) shows how the UK’s Westminster model, whilst already challenged prior Brexit, has perdured, and ‘muddled through’ even if Brexit has generated even more tensions within it.

7 Conservative Party factions’ influence on other aspects of foreign policy like security cooperation with the EU has also been notable (see Martill, Citation2023).

8 For more on the legal intricacies of modifications in the rolled-over agreements see Deepak, Citation2021.

9 On how the Withdrawal Agreement affected the subsequent TCA see Polak, Citation2021.

10 On the interaction between the Good Friday Belfast Agreement of 1998 and Northern Ireland trilemma see Murphy, Citation2021.

11 In the EU’s PTA concluded with New Zealand (July 2022), the trade and sustainable development chapter is, for the first time, subject to the agreement’s general dispute settlement.

12 In 2017, before triggering Article 50, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Hamond sparked the idea of ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ when he suggested that if there were no deal with the EU, the UK would have to look to low taxes and deregulation to offset Brexit losses (Rutter, Citation2020). In practice, not only is the concept a misnomer, as Singapore’s economy is regulated and its success has come mostly from being the trading hub for Asia (Teja Citation2021), but the UK Government has not followed that path. The UK has committed to not regressing from existing environmental and labour regulations, not least in the TCA with the EU and other FTAs (Rutter, Citation2020). Liz Truss’s Government (Sept.-Oct. 2022) came undone when, following a dramatic loss of trust from markets and sharp drop in the value of the pound and increase in interest rates, it had to backtrack from announced tax cuts (which were not accompanied by calculations from the Office for Budgetary Responsibility on how cuts would be offset) (Time, Citation2022).

References

- AHDB. (2020). UK and EU Import Tariffs, https://ahdb.org.uk/uk-and-eu-import-tariffs-under-no-deal-brexit

- Baetens, F. (2018). #147;No deal is better than a bad deal#148;? The fallacy of the WTO fall-back option as a post-Brexit safety net. Common Market Law Review, 55(Special Issue), 133–174. http://doi.org/10.54648/COLA2018062

- Bailey, D., De Propris, L., De Ruyter, A., Hearne, D., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2023). Brexit, trade and UK advanced manufacturing sectors: A midlands’ perspective. Contemporary Social Science, 18(2), 250–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2023.2192700

- Barnard, C. (2021). Protection of the UK Internal Market: Article 6 of the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol. Brexit Institute Working Paper Series No 1/2022, http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3986200

- Barrett, D., & Tsui, A. O. (1999). Policy as symbolic statement: International response to national population policies. Social Forces, 78(1), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/78.1.213

- BBC. (2022). Australia free trade deal a failure for UK, says George Eustice, 15 November 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-63627801

- BBC. (2023). Brexit: Ministers to ditch deadline to scrap retained EU laws. 11 May 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-65546319

- Böhringer, C., & Vogt, C. (2004). The dismantling of a breakthrough: The Kyoto protocol as symbolic policy. European Journal of Political Economy, 20(3), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2004.02.004

- Cass, L. R. (2008). A climate of obstinacy: Symbolic politics in Australian and Canadian policy. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 21(4), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557570802452763

- Clarke, J. (2020). Re-imagining space, scale and sovereignty: The United Kingdom and “Brexit”. In D. M. Nonini, & I. Susser (Eds.), The tumultuous politics of scale: Unsettled states, migrants, movements in flux (pp. 138–150). Routledge.

- Committee on Leaving the European Union House of Commons. (2017). First Report, Inquiry into UK’s negotiating objectives for withdrawal from the European Union, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmexeu/815/81502.htm

- CPTPP. (2019). Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/tpp-11-treaty-text.pdf

- Crowley, M., Exton, O., & Han, L. (2018). Renegotiation of trade agreements and firm exporting decisions: evidence from the impact of Brexit on UK exports. In Society of International Economic Law (SIEL), Sixth Biennial Global Conference. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/280300/cwpe1839.pdf?sequence = 1

- De Bièvre, D., Garcia-Duran, P., Eliasson, L. J., & Costa, O. (2020). Politicization of EU trade policy across time and space. Politics and Governance, 8(1), 239–242. https://doi.org/10.17645/PAG.V8I1.3055

- Deepak, G. (2021). Brexit-The legal intricacies in rolling over EU PTAs. Georgetown Journal of International Law, 52(3), 679–691. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/geojintl52&div=25&id=&page=

- Dent, C. M. (2023). The UK’s new free trade agreements in the Asia-pacific: How closely is it adopting US trade regulation? The Pacific Review, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2023.2181862

- Diamond, P. (2023). Post-Brexit challenges to the UK machinery of government in an ‘Age of Fiasco’: The dangers of muddling through? Journal of European Public Policy, DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2023.2225562

- DIT. (2020). UK-US Trade Agreement. UK Approach to Negotiations. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-uks-approach-to-trade-negotiations-with-the-us

- DIT. (2021). Impact assessment of the Free Trade Agreement between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Australia, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1073969/impact-assessment-of-the-free-trade-agreement-between-the-united-kingdom-of-great-britain-and-northern-ireland-and-australia.pdf

- DIT. (2022a). Submission to ITC Inquiry: Trade and Foreign Policy, https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/106925/html/

- DIT. (2022b). Impact assessment of the Free Trade Agreement between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and New Zealand https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1057311/uk-new-zealand-free-trade-agreement-impact-assessment.pdf

- Doherty, B., Temple Lang, J., McCrudden, C., McGowan, L., Phinnemore, D., & Schiek, D. (2017). Northern Ireland and ‘Brexit’: The European Economic Area Option. U of Michigan Law & Economic Research Paper, (16-038), 2018-01.

- Dooley, N. (2023). Frustrating Brexit? Ireland and the UK’s conflicting approaches to Brexit negotiations. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(5), 807–827. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2050780

- Duina, F. (2019). Why the excitement? Values, identities, and the politicization of EU trade policy with North America. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(12), 1866–1882. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1678056

- Edelman, M. J. (1971). Politics as symbolic action: Mass arousal and quiescence. Academie Press.

- Eiser, D., McEwen, N., & Roy, G. (2021). The trade policies of Brexit Britain: The influence of and impacts on the devolved nations. European Review of International Studies, 8(1), 22–48. https://doi.org/10.1163/21967415-bja10034

- Euractiv. (2019). Vietnam and EU sign ‘milestone’ free trade agreement. 01.07.2019 https://www.euractiv.com/section/asean/news/vietnam-and-eu-sign-milestone-free-trade-agreement/

- European Commission. (2022a). Q&A. Commission launches four new infringement procedures against the UK, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_22_4664

- European Commission. (2022b). EU-New Zealand Trade Agreement. Agriculture. https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/09242a36-a438-40fd-a7af-fe32e36cbd0e/library/5eaa0c52-b4ea-4da8-ae62-800492babd4b/details

- European Council. (2016). European Council Meeting (18 and 19 February 2016) – Conclusions, The United Kingdom and the European Union, EUCO 1/16, http://docs.dpaq.de/10395-0216-euco-conclusions.pdf

- Fahey, E. (2021). The European Union as a digital trade actor: The challenge of being a global leader in standard-setting. International Trade Law and Regulation. International Trade Law and Regulation, 27(2), 155–166. https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/26428/8/

- FCO. (2018). Global Britain Memorandum from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmfaff/780/78008.htm#_idTextAnchor035

- Figueira, F., & Martill, B. (2021). Bounded rationality and the Brexit negotiations: Why Britain failed to understand the EU. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(12), 1871–1889. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1810103

- Fossum, J. E., & Graver, H. P. (2018). Squaring the circle on Brexit: Could the Norway model work? Policy Press.

- Fotaki, M. (2010). Why do public policies fail so often? Exploring health policy-making as an imaginary and symbolic construction. Organization, 17(6), 703–720. DOI: 10.1177/1350508410366321

- Fox, L. (2016). Launch of the World Trade Report 2016- Speech to WTO, 27 September 2016, https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/launch-of-the-world-trade-report-2016-inclusive-trade-and-smes

- Fox, L. (2017). Free Trade is in our national DNA-Speech at Launch of Institute for Free Trade, 27 September 2017, https://ifreetrade.org/article/liam_fox_free_trade_is_in_our_national_dna

- Freeman, R., Manova, K., Prayer, T., & Sampson, T. (2022). UK trade in the wake of Brexit. Centre for Economic Performance Paper No. 1847. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/117855/1/dp1847.pdf

- Fusacchia, I., Salvatici, L., & Winters, A. (2022). The consequences of the trade and cooperation agreement for the UK’s international trade. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 38(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grab052

- Gammage, C., & Syrpis, P. (2022). Sovereignty fictions in the United Kingdom's trade agenda. International & Comparative Law Quarterly, 71(3), 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020589322000173

- García, M. (2020). Slow rise of trade politicisation in the UK and Brexit. Politics and Governance, 8(1), 348–359. http://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i1.2737

- Gasiorek, M., & Jerzewska, A. (2020). The unresolved difficulties of the Northern Ireland protocol. UK Trade Policy Observatory, Briefing Paper. https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/files/2020/06/BP-41-final.pdf

- Gasiorek, M., Larbarestier, G., & Tamberi, N. (2021). The value of the CPTPP for the UK. UKTPO Blog, 3 February 2021, https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2021/02/03/the-value-of-the-cptpp-for-the-uk/

- Gasiorek, M., & Magntorn Garrett, J. (2020). Reflections on the UK Global Tariff: good in principle, but perhaps not for relations with the EU, UKTPO Blog, 21 May 2020, https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2020/05/21/reflections-on-the-uk-global-tariff-good-in-principle-but-perhaps-not-for-relations-with-the-eu/

- Graziano, A., Handley, K., & Limao, N. (2018). Brexit uncertainty and trade disintegration (No. w25334). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25334/w25334.pdf

- Greer, A., & Grant, W. (2023). Divergence and continuity after Brexit in agriculture. Journal of European Public Policy, DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2023.2204118

- The Guardian. (2023). Changing attitudes to Brexit three years on. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/ng-interactive/2023/jan/30/changing-attitudes-to-brexit-three-years-on

- Gustafsson, G. (1983). Symbolic and pseudo policies as responses to diffusion of power. Policy Sciences, 15(3), 269-287. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007BF00136828

- Gustafsson, G., & Richardson, J. J. (1979). Concepts of rationality and the policy process. European Journal of Political Research, 7(4), 415–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1979.tb00916.x

- Hestermeyer, H., & Ortino, F. (2016). Towards a UK trade policy post-Brexit: The beginning of a complex journey. Kings Law Journal, 27(3), 452–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/09615768.2016.1254416

- Hix, S. (2018). Brexit: Where is the EU-UK relationship heading? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(S1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12766

- Hix, S., Hagemann, S., & Frantescu, D. (2016). Would Brexit matter? The UK’s voting record in the Council and the European Parliament. VoteWatch Europe, Brussels. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/66261/1/Hix_Brexit%20matter_2016.pdf

- Hobolt, S. B., Tilley, J., & Leeper, T. J. (2022). Policy preferences and policy legitimacy after referendums: Evidence from the Brexit negotiations. Political Behavior, 44, 839–858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09639-w

- House of Lords International Agreements Committee. (2021). 10th Report 2021-22, UK Accession to CPTPP: Scrutinising Government’s Negotiation Objectives, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/7859/documents/81612/default/

- Hy, R. (1978). Some aspects of symbolic education policy: A research note. The Educational Forum, 42(2), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131727809336302

- ITC International Trade Committee House of Commons. (2022a). UK trade negotiations: Parliamentary scrutiny of free trade agreements, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/30492/documents/175947/default/

- Katsaroumpas, I. (2023). Different shades of minimalism: The multilateral construction of labour clauses in UK-Australia and UK-New Zealand FTAs. King’s Law Journal, 34(1), 71–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/09615768.2023.2199467

- Kelly, C. J., & Tannam, E. (2023). The UK Government’s Northern Ireland policy after Brexit: A retreat to unilateralism and muscular unionism. Journal of European Public Policy, DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2023.2210186

- Latorre, M. C., Olekseyuk, Z., Yonezawa, H., & Robinson, S. (2019). Brexit: Everyone loses, but Britain loses the most. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper, (19-5). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id = 3345244

- Lowe, S. (2022). Most-favoured nation: Trade policy in the metaverse. Most Favoured Nation, 25 March 2022, https://mostfavourednation.substack.com/p/most-favoured-nation-trade-policy

- Marion, N. E. (1997). Symbolic policies in Clinton's crime control agenda. Buffalo Criminal Law Review, 1(1), 67–108. https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.1997.1.1.67

- Marshall, J., & Sargeant, J. (2022). Northern Ireland Protocol: Ongoing UK-EU Disagreements. Institute for Government, 26 January 2022, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/northern-ireland-protocol-disagreements

- Martill, B. (2023). Withdrawal symptoms: Party factions, political change and British foreign policy post-brexit. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2198578

- McConnell, A. (2020). The use of placebo policies to escape from policy traps. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(7), 957–976. http://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1662827

- McEwen, N. (2021). Negotiating brexit: Power dynamics in British intergovernmental relations. Regional Studies, 55(9), 1538–1549. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1735000

- McGowan, L. (2017). Preparing for Brexit: Actors, negotiations and consequences. Springer.

- McKee, I., & Gougeon, M. (2022). New Zealand Trade Agreement. A letter from the Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs and Islands and the Minister for Business, Trade, Tourism and Enterprise to the UK Minister for Trade Policy. 21 August 2022. https://www.gov.scot/publications/new-zealand-trade-agreement-letter-to-the-uk-government/

- Morita-Jaeger, M. (2020). Japan-UK Free Trade Agreement –What is missing?, UKTPO Blog, https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2020/10/22/japan-uk-fta-what-is-missing/

- Murphy, M. (2021). Northern Ireland and Brexit: Where sovereignty and stability collide? Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 29(3), 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2021.1891027

- Murphy, M., & Evershed, J. (2022). Contesting sovereignty and borders: Northern Ireland, devolution and the union. Territory, Politics, Governance, 10(5), 661–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.1892518

- Murray, C. R. G., & Robb, N. (2023). From the protocol to the Windsor framework. Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4382498

- Neville, A., Hallak, I., & Mazzur, S. (2022). Implementation of the UK Withdrawal Agreement: Financial provisions, citizens’ rights and the Northern Ireland Protocol. | European Parliamentary Research Service, PE 698.884, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2022/698884/EPRS_IDA(2022)698884_EN.pdf

- Office for Budget Responsibility. (2022). Economic and Fiscal Outlook-March 2022. https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-march-2022/

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2023). https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/balanceofpayments/timeseries/jim7/mret https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/balanceofpayments/timeseries/jim8/mret

- O’Toole, F. (2022). Britain’s attack on its own protocol is one more exercise in Brexit gaslighting. The Guardian, 15 June 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/jun/15/britain-ni-protocol-brexit-ministers-deal

- Paquin, S., Rioux, X. H., Eiser, D., Roy, G., & Wooton, I. (2021). Quebec, Scotland, and substate governments’ roles in Canadian and British trade policy: Lessons to be learned. International Journal, 76(1), 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020702021992856

- Polak, P. R. (2021). Who had their cake and ate it? Lessons from the UK’s withdrawal process and Its impact on the post-Brexit trade talks. German Law Journal, 22(6), 983–998. https://doi.org/10.1017/glj.2021.54

- Politico. (2017). Boris Johnson: Countries ‘queuing up’ for post-Brexit trade deals, 18 January 2017, https://www.politico.eu/article/boris-johnson-countries-queuing-up-for-post-brexit-trade-deals/

- Politico. (2022). Joe Biden could ghost Boris Johnson over Northern Ireland Brexit row, 19 May 2022. https://www.politico.eu/article/us-president-joe-biden-could-ghost-boris-johnson-in-brexit-row/

- Portes, J. (2022). The Economics of Brexit: What Have We Learned?, CEPR Press, https://cepr.org/publications/books-and-reports/economics-brexit-what-have-we-learned

- Reilly, M. (2020). The great free trade myth. British foreign policy and east Asia since 1980. Routledge.

- Rollo, J., & Holmes, P. (2020). EU-UK post-Brexit trade relations: Prosperity versus sovereignty? European Foreign Affairs Review, 25(4), 523–550. https://doi.org/10.54648/eerr2020037

- Rosamond, B. (2019). Brexit and the politics of UK growth models. New Political Economy, 24(3), 408–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1484721

- Rutter, J. (2020). ‘Singapore on Thames is dead. Long live Singapore on Thames’ UKICE Commentary, https://ukandeu.ac.uk/singapore-on-thames-is-dead-long-live-singapore-on-thames/

- Schnapper, P. (2021). Theresa May, the Brexit negotiations and the two-level game, 2017–2019. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 29(3), 368–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2020.1753665

- Scottish Government. (2022). Agriculture and the Environment. Government Website, https://www.gov.scot/policies/agriculture-and-the-environment/gm-crops/

- Siles-Brügge, G. (2019). Bound by gravity or living in a ‘post geography trading world’? Expert knowledge and affective spatial imaginaries in the construction of the UK’s post-Brexit trade policy. New Political Economy, 24(3), 422–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1484722

- Steinberg, J. B. (2019). Brexit and the macroeconomic impact of trade policy uncertainty. Journal of International Economics, 117, 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2019.01.009

- Sykes, O. (2018). Post-geography worlds, new dominions, left behind regions, and ‘other’ places: Unpacking some spatial imaginaries of the UK’s ‘Brexit’ debate. Space and Polity, 22(2), 137–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2018.1531699

- Teja, N. (2021). ‘Opinion: Singapore-on- Thames is a post-Brexit fantasy’ International Financial Law Review, 25 March 2021, https://www.iflr.com/article/2a6466axp6qvytzvdg6ww/opinion-singapore-on-thames-model-is-a-post-brexit-fantasy

- Time. (2022). ‘Liz Truss has resigned. Here’s how she lost control.’ 20 October 2022, https://time.com/6223365/why-liz-truss-resigned/

- Tonge, J. (2022). The 2022 Northern Ireland Assembly elections: Polling, power-sharing, protocol. Political Insight, 13(2), 10–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041905822110877

- Trade Justice Movement. (2018). A trade model that works for everyone. Trade Justice Movement. https://www.tjm.org.uk/resources/briefings/a-trade-governance-model-that-works-for-everyone

- Trommer, S. (2017). Post-Brexit trade policy autonomy as pyrrhic victory: Being a middle power in a contested trade regime. Globalizations, 14(6), 810–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2017.1330986