ABSTRACT

In Bangladesh, participation discourse has officially become part of the objectives of the government and international agencies for water management projects since the mid-1990s. At the same historical timeframe, originating from indigenous knowledges Tidal River Management (TRM) has been formalized as a less structural and more natural management intervention to prevent the severe water-logging in the South-west region in the Bangladesh delta. It theoretically constituted a form of participation in the delta management system involving local community groups with government and management authorities. However, multi-stakeholder participation is still very challenging in practices. Even community management approaches are not sustained in delta management practices in Bangladesh. In this research, a socio-technical transformation is defined through a participatory research in the south-west coastal area having both qualitative and quantitative evaluation of changes in the delta management system brought about by TRM practices. This article also analyses the current problems besetting organized community participation in existing management practices and suggests the ways of developing effective multi-stakeholder processes (MSPs) with respect to sustainable management goal in deltas.

Introduction

In Bangladesh socio-economic development is essentially linked with water and the water ecosystem because of its location within the largest delta of the world, encompassing the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna river systems (Jakobsen et al. Citation2005; Mutahara et al. Citation2016; Gain et al. Citation2017a). Shifting from a traditional approach, formal water resources management engineering was introduced in the Bangladesh delta in the 1960s (that time called East-Pakistan), inspired by a global discourse on mega-structural engineering in flood protection and agricultural development particularly by following the Dutch dyke system (Dewan et al. Citation2015; Mutahara et al. Citation2017). Dykes/polders in tidal river catchments under the Coastal Embankment Project (CEP) prevented silt from being flowed on the river floodplains. It caused severe sedimentation in the riverbeds and raised water levels in the rivers higher than the polders leading to a permanent waterlogging problem in the South-west part of Bangladesh delta (Sarker Citation2004; Amir et al. Citation2013).

Although flooding is a recurring phenomenon in this delta, waterlogging and drainage congestion had not been severe anywhere before the 1980s (Nowreen et al. Citation2014). Waterlogging as a kind of slow flooding has become an ever-growing problem and causes severe socio-economic disruptions in the South-western delta in Bangladesh. Consequently, the management approach was changed again and Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) officially introduced Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) approach in the mid-1990s (Rouillard et al. Citation2014; Gain et al. Citation2017b). In the meantime, local community had introduced Tidal River Management (TRM) process to resolve waterlogging, re-store the tidal rivers, and develop agricultural system in the south-west Bangladesh delta (Tutu Citation2005; Mutahara et al. Citation2017). According to reviewed literatures, TRM is the concept of a local-knowledge based, ‘soft’, delta management technique (Wesselink et al. Citation2015) highlighting multiple aspects of a delta resource system like environmental conservation (e.g. water and ecology), participatory interventions (e.g. institutions and technology), and agricultural development process (e.g. water, land, and society) (Mutahara et al. Citation2017; Masud et al. Citation2018; Seijger et al. Citation2019; Gain et al. Citation2019b). Our present research focuses on TRM as one of the promising transitions in water management system in a particular part of Bangladesh delta.

The delta is itself a complex system however the inter-relationships between social, ecological, and technological resources evolve more dynamics in delta management system transformation (Mutahara et al. Citation2016; Van Staveren et al. Citation2017). In Bangladesh delta, water management interventions are rare to sustain due to multiple conflicts and complexities in social interaction and stakeholder relationships (Haque et al. Citation2015; Mutahara et al. Citation2019). This research argues that the success of participatory management has been limited over the last two decades, the sustainable adaptation of delta management system has become deeply uncertain in this area (Nowreen et al. Citation2014; Mutahara et al. Citation2017). Even community-based management system does not sustain in the coastal management system. It is still challenging that how the participatory management discourse works in practice and the extent to which it enables community participation in a multi-stakeholder context. We have focused on TRM practices in regional water management system in the south-western Bangladesh delta which indeed requires effective participation and stakeholder co-ordination to manage the obstacles with transformative changes in social, ecological, and technical contexts in the delta system. Based on the above discussion, the main research questions in this paper are: How does socio-eco-technical transformation occur in the delta system due to new management approach such as the application of TRM? And what are the current problems besetting organized Multi-stakeholder participation process in changing management practices?

The background studies show that several reports related to IWRM and TRM in the Southwest Bangladesh Delta had been published from government agencies and some NGOs before 2010. However, scientific academic researches on TRM practices have appeared in recent years. While Dewan et al. (Citation2015) examined the evolution of participatory water management system in Bangladesh emphasizing policies and institutions in a timeframe, our research focuses to step further to understand the transformations in such a multi-disciplinary system inter-relationship. In this connection, the major change assessment researches on coastal management and TRM system we studied include changes in social and hydro-ecological systems (Roy et al. Citation2017) and socio-ecological system changes (Gain et al. Citation2019a). However, our present research investigates the system transformation within a conceptual framework of three (social, ecological and technical) inter-relationships in a delta system defining as bio-physical changes (e.g. delta management practice impacts the water system), socio-institutional changes (e.g. delta management practice involves social actors), and socio-economic changes (e.g. a delta social system depends on the water system) due to practicing TRM. The outcome also aims at contributing to better understanding and leaning on multiple management system dynamics in a complex multi-stakeholder process in managing deltas. For this study we have focuses on the practiced and practicing TRMs in the Khulna-Jessore Drainage Rehabilitation Project (KJDRP) area in Khulna and Jessore Districts in South-west Bangladesh delta.

Tidal river management (TRM) as a regional delta management system

Originating in indigenous knowledge, TRM was intended as a more natural and less structural delta management intervention in tidal basin area to reduce siltation in the riverbed and to prevent waterlogging (Amir et al. Citation2013; Khadim et al. Citation2013; Mutahara et al. Citation2017). Technically, TRM would allow the natural movement of sediment-borne tidal water into an embanked tidal basin or beel (wetland/depressed landforms in river floodplain) at high tide and allow the deposition of sediment inside the beel. At ebb tide, the outgoing silt-free water would scour the riverbed at high velocity and increase its drainage capacity (Shampa and Pramanik MIM Citation2012; Amir et al. Citation2013; Paul et al. Citation2013, Masud et al. Citation2018). During TRM the concerned beel was exposed to free tidal movement for a certain number of years. This eventually led to sedimentation and raising of the land level within the embanked beel area. In addition to relieving water-logging, TRM created an opportunity for increased crop production and habitation on higher flood-free lands (CEGIS Citation2003; Nowreen et al. Citation2014; Gain et al. Citation2017b).

We have focused to KJDRP for this research because firstly people of this area had been suffering much due to waterlogging since the 1980s and finally most of the informal (referred to as a ‘public cut’ in beel Dakatia and beel Bhaina) and formal (beel Kedaria and beel Khuksia) TRM practices are located in that project area (Mutahara et al. Citation2017). The project KJDRP covers an area of approximately 100,600 ha having about 800,000 people in Khulna and Jessore Districts. This regional water management project includes 27 beels within three main tidal river catchments such as the Upper Bhadra system, Mukteswari-Hari system, and South-eastern/Sholmari system (CEGIS Citation2003; Amir et al. Citation2013).

Conceptual framework

The challenges and uncertainties associated with delta water management practices are transformed through concerted actions by multi-level actors and their institutions within a complex system relationship (Ison and Watson Citation2007). With this concept, the present research reviewed Multi-stakeholder processes (MSPs) as a means to support the invention of participatory water management (Woodhill Citation2004; Pahl-Wostl Citation2006; Warner Citation2006) and improve actor interactions in a transformative delta management system (Geels and Kemp Citation2007). So, in present research key ideas and useful research elements were studied as:

Multi-stakeholder participation in a delta water management and

Transformation in a delta water management system trajectory includes changes in social, ecological, and technological relations.

Multi-stakeholder participation

Multi-stakeholder processes have played a crucial role in implementing sustainable development-related goals ever since the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg (Pattberg and Widerberg Citation2016). The ‘partnership’ approach in integrated management has also been promoted worldwide as a promising means of dealing with challenges and making decisions in natural resources management (Malena Citation2004; Warner Citation2006). Furthermore, the concept of multi-stakeholder participation is capturing the imagination of the international water sector in its attempt to respond to an increasing demand for participatory governance, stakeholder engagement, and interactive policy-making for sustainable development (Pahl-Wostl Citation2007; Hajer et al. Citation2015). In this article, we have conceptualized ‘Multi-stakeholder Partnership’ concerning the improvement of participation as a collaborative and interactive approach for managing changes, improving community capacity and promoting sustainable management in a river delta system (Warner Citation2010; Brouwer et al. Citation2015). In a participatory multi-stakeholder process, interactions between stakeholders and their constituencies, facilitate innovation and foster a pathway for positive transitions in a multi-dimensional system (Tukker and Butter Citation2007; Cundill Citation2010). Furthermore, interactions and collaborations may improve with the generation of new knowledge and learning in multi-actor innovation networks (Pekkarinen and Harmaakorpi Citation2006) where, for instance, farmers, scientists, students, NGOs and policymakers together can find answers to existing social, economic and ecological issues (Sol and Wals Citation2015). In management system, the multi-actor network is defined at three levels: Mico, meso and macro. In the present research, our focus goes to the micro-level multi-stakeholder collaboration in which representatives from different stakeholder groups interact at local and regional levels regarding practical issues and changes within a complex system relationship (Ison and Watson Citation2007).

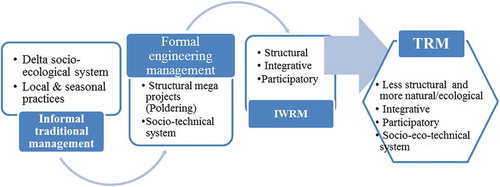

Participatory approaches in environmental development and water management are the focus of attention in Bangladesh since the 1990s (Ahammed and Harvey Citation2004). In the policy level, the Bangladesh National Water Policy (Citation1999) highlights the importance of stakeholder participation in water management. The previous studies showed the overall changes in delta management approach in the South-west region of Bangladesh had moved away from traditional small-scale, temporary poldering to the current, formal TRM process. gives a systematic diagram of water management transitions in that area. Since TRM is originally a community-initiated management process, local people have been actively involved in practicing it, ‘informally’ (EGIS I. Citation2001). While government authorities have taken the lead in implementing TRM, they stress the importance of multiple stakeholder participation (CEGIS Citation2003). But that is basically on paper; in practice, such participation does not sustain and remains very much perplexing, particularly at the community level (de Die Citation2013; Haque et al. Citation2015; Mutahara et al. Citation2017).

Transition and transformations in a delta system: interrelations and changes

Theoretically, transitions refer to change in a dynamic equilibrium from one state of equilibrium to another. Geels and Kemp (Citation2007) distinguished between ‘transformation’ and ‘transition’. Transformation in their view refers to a change in the direction of trajectories, related to an alteration in the rules that guide innovation. It is widely expected that science and technology should contribute to environmental management and policymaking (Bukowski Citation2016). So, we could think that the use of a new technology or significant changes in an existing technology in a delta system may trigger the management transformation in the total system.

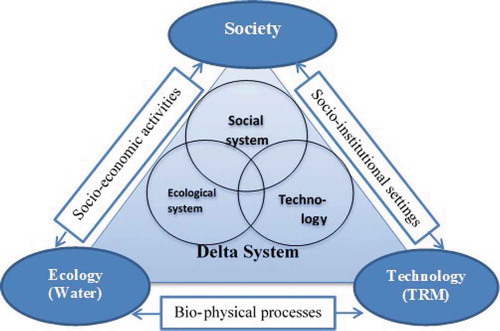

From a broader perspective of keen interaction between human actors and environmental processes, the largest deltas in the world are now being considered a socio-ecological system (referred to as Delta-SES) (Berkes et al. Citation2002; Renaud et al. Citation2013; Van Staveren and van Tatenhove Citation2016). Most of the delta studies of Bangladesh were also inspired by this SES concept and analysed it as a rural society that mostly depending on a floodplain agro-ecological system (Nawreen et al. Citation2014) and also vulnerable to tidal flooding, excessive salinity intrusion, and frequent cyclone and storm-surge hazards (Islam and Gnauck Citation2008; Mutahara et al. Citation2016). However, water management is subject to technical intervention to modify the spatial or temporal process in a water system by managing natural hazards (Young et al. Citation2006). Delta water management may also be defined as a socio-technical system (Wester and Bron Citation1996) in which physical and social processes are closely connected to coastal hazards and risk reduction. In the present research, the idea of a delta management system is defined based on the relationship between the environmental processes, societal activities, and management technology (or tools), which previously had been used in a socio-technical approach in irrigation system analyses (Kloezen and Mollinga Citation1992; Vincent Citation1997; Mollinga Citation2003). In the case of the south-west Bangladesh, Amir et al. (Citation2013) also argued that TRM is an eco-technological approach with the potential of solving the waterlogging problem and improving agro-ecological development. Identifying various combinations of social, ecological, and technological aspects in delta water management literature, our study suggests a combination of those three components in a triangular (Δ) arrangement: a Socio-Eco-Technical (S-E-T) system – for better understanding of and learning about the dynamic changes in delta management ().

Figure 2. Triangular management system approach: Transformation pathways in the Socio-eco-technical system in a dynamic delta.

As delta management transition is not a simple shifting of management technology or techniques, the delta management researchers are broadening their change analysis approaches as part of a shift towards a ‘complexity paradigm’ in environmental research (Manson Citation2001; Manson and O’Sullivan Citation2006). Therefore, we have conceptualized that environmental management systems are increasingly complicated (due to the inclusion of social, economic and physical factors), complex and uncertain (due to the nonlinear relations between environment, society and technological domains), and as a result, increasingly contested (by a public less willingness to surrender power to traditional experts). There has also been a widespread scope of transdisciplinary as well as interdisciplinary research on system transition in delta management by integrating natural and social sciences (Uyarra et al. Citation2017; Gain et al. Citation2017a).

Transformations in a dynamic management system appear that the technology is mediating not only with the changes in people’s actions to bio-physical domain but also shaping or being shaped by a relationship between society, ecosystem, and management policy and technology (Van Staveren et al. Citation2017). Central to this theory is evolved here on how mutual interaction between the social system and the delta ecosystem takes shape and transforms as a result of changes in delta management technology over time (Geels and Kemp Citation2007). This concerns both historical timescales (how past practices influenced and have directed present practices) and a present timescale (how present practices affect the delta system and influence social processes). In this study, while anthropological studies give us an idea of how communities cope with adverse challenges (Duyne Citation1998), there is little knowledge about socio-technical systems' resilience and local-central links. The interaction between communities and management groups in Bangladesh has often been tense, especially where local practices are seen by outsiders as ‘deviant’ and backward (Warner Citation2010). So, the gaps in interaction and management co-ordination force local stakeholders to be self-reliant, but result in weak links with support systems, especially for the more vulnerable groups of stakes (Mutahara et al. Citation2017).

Methodology

A mixed-method approach was used in which both qualitative and quantitative data were collected from secondary and primary sources in the KJDRP project. Preliminary investigation and literature reviews helped articulate the research background and develop the main hypothesis and concepts for analysis.

The bio-physical change analysis was designed using hydro-morphological data, relevant images, and physical model data (historical and recent) from published reports and research findings in KJDRP project studies conducted by government and non-government organizations as also from research institutes.Footnote1 The field study followed principles of Rapid Water Management Appraisal (RWMA) (Wester and Bron Citation1996; Chambers Citation2002), which is an adaptation of Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) techniques [http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/w2352e/W2352E03.htm]

Formal and informal participatory tools were used in the study area during the field investigation from 2012 to 2017. In the beginning, several informal community meetings and 15 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted with local farmers and fisher groups as well as school teachers, business groups, and others. Elderly people were encouraged to talk about the history of water management in their areas including traditional and current practices. A timeline on current water management initiatives was drawn in the field to express the transition of water management in local perception. For the socio-economic and socio-institutional change analysis, semi-structured interviews (SIs) were conducted during 2013–2016, mostly in beel surrounding villages. The sample villagesFootnote2 were randomly selected observing their location in the periphery of beels with TRM and based on their maximum dependency on the beel system according to community perception. Respondents were mainly landowners, landless farmers, fisher folks, day labourers, shopkeepers, and housewives. Those interviews provided data on their agricultural systems, land use and productions, livelihoods, income changes, and the like. Interviews were also conducted with teachers, social workers, and political and community leaders. Representatives of relevant government and non-government organizations such as Local Government Institutions (LGIs) and upazilla level offices of the BWDB, Department of Fisheries, and Department of agriculture were interviewed to cross-check and clarify synthesized results of the community-based investigation in the TRM areas of study.

To integrate and synthesize findings from the field research, three large-scale Public Consultation Meetings (PCMs) were conducted in the study area during 2015–16 with participants from different local-level stakeholder groups. We have defined those meeting as Local Stakeholder Meetings (LSMs). These meetings provided an opportunity to move away from a purely dialogue-based approach and encouraged stakeholder involvement in collective action and participatory evaluation (Wates Citation2000; Chambers Citation2002). In these sessions, the Socio-eco-technical (S-E-T) approach for delta system analysis was defined and stakeholders’ feedback on it was invited. The majority of stakeholders supported this analytical approach and contributed to the transformation assessment, which the authors had made with respect to system relationships and components of changes in a dynamic delta.

Research findings

In view of indestructible inter-relationships in a delta Socio-eco-technical system, transformations happen with changes in natural or biophysical processes, socio-economic activities, and socio-institutional settings. In this section participatory assessment of significant changes and consequences was presented, both qualitatively and quantitatively, in the context of social, ecological, and technical system relationships in the southwest delta following TRM implementation timeframe ().

Table 1. Time scale for analysing delta system transformation in KJDRP area.

Transformations in natural tidal system occurred due to practicing TRM

The historical review showed that Coastal Embankment Project (CEP) had caused major barriers to tidal river systems in the South-west (CEGIS Citation2003; Nowreen et al. Citation2014; Roy et al. Citation2017), in particular, construction of a large 21-vent regulator in Bhabodah (done in 1964–1965) had been obstructing the Teka-Hari-Mukteswari river flow since the late 1980s (IWM Citation2007; Mutahara et al. Citation2017).

Major changes in tidal river system

According to secondary data from modelling studies of the BWDB conducted by the Institute of Water Modeling (IWM Citation2007, Citation2014), the tidal volume has increased in September 1996, though, on account of some major river excavation as part of rehabilitation activities. As can be seen in , a significant change in tidal flow has also been found after informal and formal TRM implementations in Beel Bhaina and Beel Kedaria (after Citation2005).

Figure 3. Tidal volume before, during, and after TRM in Hari River (at Ranai point)(IWM Citation2007; Citation2014).

During TRM in Beel Khuksia, the tidal volume of the Hari River was over 5 million cubic metres in May 2007, which was 6 times more than pre-TRM. This tidal volume has become even 17 times higher (from less than 1 to almost 16 million cubic metres) during TRM in Beel Khuksia in 2012. The river cross-section at Ranai point (measurement station of the Teka-Hari system in the Project) significantly improved between 2007 and 2011. It was calculated as −9.25 m PWD in January 2013, just before closing the beel Khuksia TRM (last monitoring report of IWM was in Citation2014). Within 8 months after the closing of the TRM in September 2013, a 5.5 m deep siltation was measured downstream of the Bhabodah regulator in the Hari system (field observation 2013; Institute of Water Modelling (IWM) Citation2014).

Public consultation reports and information from local NGOs gave a brief statistical view of waterlogging extent in Hari river catchment over the last decades. Before implementing TRM (1986–1990), waterlogging was extended about 7300 ha. During and just after beel Dakatia TRM (1991–1995) it became 1200 ha. However after implementation of TRM in Beel Bhaina (1997–2001), waterlogging was significantly reduced in the Hari catchment and also from total KJDRP area. It was validated by latest monitoring report of KJDRP institutional data as a change in open water area (extent of waterlogging) was reduced by almost 7% in the total KJDRP area from 2002 to 2012 (CEGIS Citation2007, Citation2014).

Changes in land cover

The implementation of TRM causes major changes in land cover in the KJDRP area as shown in . According to numerical data from secondary sources (CEGIS Citation2007; Citation2014), open water areas have significantly decreased from 1997 to 2012 and, as a result, these areas are replaced by increasing agricultural land and settlement. Agriculture land has increased by about 24% from 1997 to 2013 in the total KJDRP area.

Table 2. Land cover changes in KJDRP area.

Salinity level

Most of the KJDRP area experienced regular tidal action twice a day. Due to TRM in Beel Bhaina, tidal action was restored in the Teka-Hari-Mukteshwari system, while in the dry season (March–April) the salinity level in the river and surrounding beel area was at an average of 10–15 ppt in 2000–2001 (EGIS I, Citation2001). After that TRM was being implemented in 2002–2013 in Beel Kedaria and Beel Khuksia with some time gap. The salinity level became higher in the TRM beel areas, while it was lower by an average of 2–5 ppt in the rest of the area. In contrast, during 2012–2012 the salinity level in river and beel area was within 3–8 ppt (CEGIS, Citation2014). The main cause of salinity fluctuation in beel water is caused by a huge practice of salt water shrimp culture. Although one of the major goals of implementing TRM was to increase rice production, the shrimp culture has become dominant in recent years which is not exactly environment friendly in a delta system.

Changes in socio-economic activities

In a rural coastal area of Bangladesh like the KJDRP area, society as well as life and livelihoods are mainly dependent on land-use practices, specifically agriculture and production. So the transformation was analysed here in the context of socio-economic changes in areas surrounding TRM beels in the KJDRP area.

Changes in production pattern

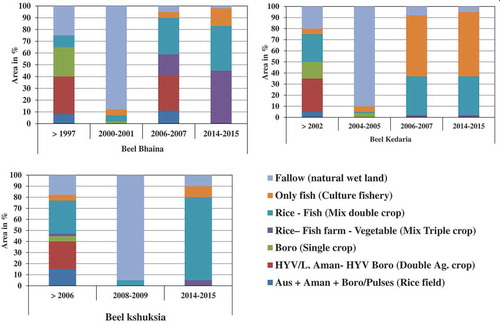

Historically, in Bangladesh two distinct agro-cropping seasons in a year: one is the Kharif season: Kharif-1 (March–June) and Kharif-II (July–October), mainly represented by the production of Aus rice and Aman rice. The other is the Rabi season (November – February), in which dry-season rice, vegetable, and pulses are grown. In our study area, one-third of the beel grew only Aman rice due to low land-level and long-term waterlogging. Community perceptions and records of LGIs show a new dimension in the cropping pattern in the study area on account of shrimp farming since 1990s. It was not significant in the KJDRP area in 1996; now, apparently, the intensity of shrimp culture (both saline and fresh water) is increasing. After the introduction of formal TRM, a new agro-fishery mixed production pattern is showing up in the study area. shows the present production pattern (on a 100% scale) in the relevant beels.

In the current analysis, an agriculture and fisheries mixed (double and triple) cropping pattern is found in most of the beels. In beel Bhaina, an incredible growth of vegetable production appeared with a mixed culture of rice and fisheries. The recently developed land area in beel Khuksia has been used mostly for rice and shrimp culture. The changes in cropping pattern and intensity have caused great change in the livelihoods in these localities.

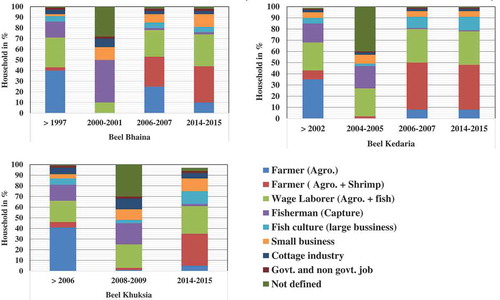

Major changes in livelihood system in KJDRP area

Before implementation of the TRM, income generation was mainly driven by crop cultivation and capturing fish in the beel area. While coastal shrimp culture had been prominently extended since the 1990s, it was not practiced extensively in the KJDRP area. Our research identified a significant change in livelihood within the last one-and-half decade, after the introduction of TRM in the area. shows changes in livelihood systems with water management situations in areas surrounding the beels.

Figure 5. Livelihood system changes in Hari river catchment area in KJDRP (Field survey, 2013–2016).

In each case, small farmers and day labourers were suffering most. Small and medium farmers had very limited opportunities and needed to seek alternatives. Small farmers in some cases worked as day labourers or turned to fishing in beels and rivers. Women from farmer families had to go also for daily labour and fishing in the beel. Particularly those who had no land and were dependent on wages from agricultural work in the beels had completely lost their sources of income. However, after TRM, a big shift was found in livelihoods. Most of the farmer community had turned to crop farming-cum-fish culture. Large shrimp businesses were started with external investment. Some people became involved in small businesses related to fried shrimp supply and fish-feed industry. Another new market opportunity was developed, thanks to an increasing production of vegetables in the beel area.

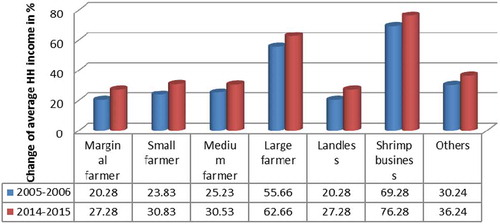

Changes in income situations

TRM also resulted in changes in living standards, triggering a generation of more income opportunities on account of new production systems in the area, thus opening up ways to better livelihoods and income as well as secure food for today and tomorrow. Household incomes and food security levels in the area have undergone major changes from 1995 to 2015. At present, farmers grow more than one crop every year. Single-crop lands occupy around 4-14% of the entire study area, whereas double-crop and triple-crop lands occupy about 50-98% in the three main TRM beels (Field survey, 2013–2015). Based on landownership, production system, and new livelihood opportunities, a participatory assessment was conducted in the study area to find the trend of household income levels for 2007–08 and 2014–15 considering the base year of 1995–96 ().

Figure 6. Trend of average household income in the study area (base year 1995–96) (Field survey, 2013–2016).

Local people explained their higher incomes because of using alternative varieties of products like high-yielding varieties of rice and vegetables as also fish farming, especially brackish/salt water shrimp. They thought that the food security level in the study area had also increased, this too, because of change in income and increase the rate of production. The income of marginal and medium farmers has been increasing and 60% of them now have scope to use their lands for rice cultivation at least once a year.

Changes in socio-institutional arrangement

Management transition is closely linked with actors and their actions. Community acceptance is one of the crucial variables in the use of management techniques and technology that may change or introduce formal and informal institutions in the delta system.

Participation and development of formal community organizations

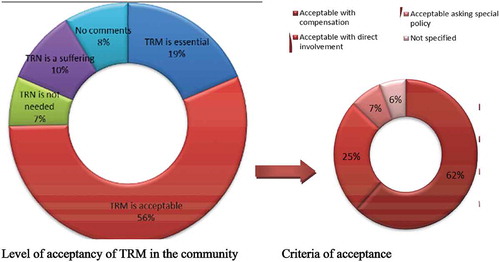

In KJDRP, government and some non-government as well as donor organizations ran a number of community consultation programmes during the TRM intervention in 2000–2001. Afterward, local, community-based, water management organizations (WMOs) were developed in nine zonal (zone A – zone I) areas in KJDRP. Following the IWRM approach, several Water Management Groups (WMGs) were established by the BWDB in each zone of KJDRP. A Water Management Association (zonal level) and Water Management Federation (KJDRP area) were also formed to have a proper communication with management authorities. However, it was not sustainably functional and during our field study (2012–2016) we did not find any formal WMO in action. During our research (2012–2016), most people put forward that TRM has the potential to prevent waterlogging and protect the tidal river in their localities. However due to lack of practicing participatory processes (compensation and social management initiatives, active community groups and organizations, etc.), after about two decades of TRM intervention still there are mixed impressions and conflicts in perception within the stakeholders (see ).

shows that about 10% of the population, who were mostly landless and small land-owners, thought TRM a disaster because they lost their source of income during TRM. Some 19% were strong proponents of TRM. While 56% were interested, they were concerned about a proper timeframe and compensation. Local knowledge groups (including teachers, journalists, NGO researchers, and social activists) also asked for a special policy and even a new water law for sustainable TRM in the coastal area.

Compensation and project affected people

During informal TRM, landowners allowed their land to be taken losing crop yields in the bargain. They were sacrificing their production for the broader benefit of their locality. However, when TRM was formalized as a government and donor-funded project, landowners and project-affected people were, logically, expecting compensation. Then, the BWDB had to change their way of land acquisition for infrastructure construction and formed a new land requisition strategy for the TRM intervention period (CEGIS Citation2008). The Water Board declared crop compensation for landowners during the beel Khuksia TRM intervention at the end of 2007. They proposed it for 2 years, even though a TRM intervention was running for about 7 years in such a beel. In the case of TRM in beel Kapalia (proposed in Citation2012), the compensation programme was started before the implementation of TRM and had gone well enough as compared to beel Khuksia. But TRM in beel Kapalia has not started yet. gives an overview of compensation activities.

Table 3. Compensation activities due to TRM in KJDRP area.

As the application procedure and the payment process had not been clearly defined at community level, the majority had been struggling to apply for compensation due to their limited knowledge about legal papers, unclear land recording system, and other bureaucratic issues. There are no initiatives for socio-economic support to the landless, who are actually most affected.

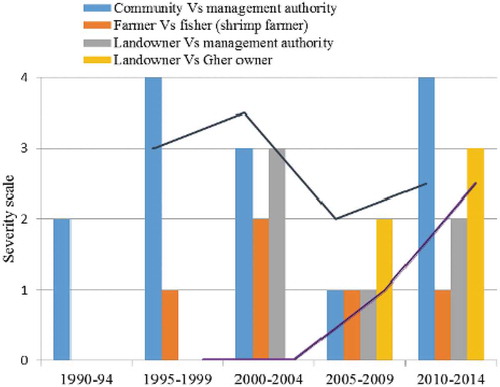

Conflicts in water management

Before and early 1990s conflicts erupted because of non-functioning larger structures issue and the beel Dakatia embankment cut by community people in protest against the activities of the authority. It was the first recorded attempt of TRM in KJDRP area which caused conflict between communities and BWDB. In the meantime, shrimp culture was entered in the southwest area and new conflicts between agro-farmer and shrimp farmer (mainly shrimp business holder) took place regarding the use of saline water in crop fields. From 1997 to 2012, two major categories of conflict are identified such as community vs management authority and within the community (Mutahara et al. Citation2019). The study on sources, nature and intensity of conflicts in relevant to TRM was found in detail in reviewing literature as Mutahara et al. (Citation2019). Therefore, in the present study, we tried to present the severity of observed conflicts in the KJDRP area over time, based on stakeholders’ perceptions. In a field survey, a 5-point (0–4) ordinal, severity scale was used with a ranking of ‘most severe’, ‘severe’, ‘moderately severe’, ‘not severe’, and ‘nothing’, based on socio-economic sufferings of local people in conflicting situations (). From the Bhabodah incident (in 1986) to the Beel Kapalia fight (2012), local people, whether directly involved in the conflict or neutral, faced legal harassment every time. The BWDB has taken several legal steps to indict community people as suspected, whether as a group or individually. People have lost money as well as social dignity. These conflicts have created a durable, adverse impact on the community’s livelihood system.

Migration due to TRM

In the study area, two types of migration related to water management practices were observed closely. In the 1990s migration took place because of severe waterlogging in the South-west. Particularly lower-income people migrated, when the area adjacent to beel Dakatia was waterlogged for a long time. After 2000, people migrated internally during the beel Bhaina TRM because of tidal over-flow in adjacent villages. Besides, the right bank of the Hari downstream became eroded during TRM in this beel forcing landless people who were living on the river bank, to migrate. In our study, respondents could identify only a few out-migrated families in the beel Khuksia area with an average of five to eight (5–8) per year in 2008–2011. From 2013, labour out-migration increased due to the less labour-intensive shrimp farming activities and use of technology in agriculture like tractor, pump, and crop harvesting instruments.

Discussion

This research discussed that the evolution and formalization of Tidal River Management (TRM) have provided the recent technological change discourse in regional and local delta management. Transformation in a delta system has been triggered by TRM, improving river capacity, reducing waterlogging, and increasing agricultural land. It is not simply that the improved river capacity and developed landforms in the beels have brought about great changes in the socio-ecological system (van Staveren et al. Citation2016), but the changes in socio-institutional arrangement and activities (Gain et al. Citation2019a) have also introduced more challenges and complexities in a very rural delta management system. The findings expressed that existing uncertainties in formal TRM actions and stakeholders’ relations represent a serious barrier to effective participation.

(i) Inequality in stakeholders and their power relation

BWDB was the main implementing authority of delta management under the Ministry of Water Resources (MoWR) which controls all pertinent planning and construction activities as seen as the supreme power within the stakeholder network. But socially and financially, empowered local groups are active at micro level and they also wield at least some power. For instance, the large shrimp business holders have the capacity to influence the local administrative authority as well as BWDB (Mutahara et al. Citation2017). In the rural setting, however, marginalized community people are not financially empowered and have high levels of illiteracy. Their voices do not tend to get through to BWDB or top governance levels. They mainly depend on local government organizations and political leaders as well as NGOs. This creates difficulties in developing consistent and efficient multi-layered interaction in management networks.

(ii) Political influence

Although political parties are not explicitly involved in water management, invisible politics are everywhere, especially in participatory events like public consultations and meetings. In construction activities and compensation distribution, political influence determines to a large degree who gets what and how much, as elected members of local government and society leaders tend to belong to political parties. BWDB’s construction activities require the hiring of construction companies that have political ties or try to bribe decision-makers. Corruption at local and regional organization levels is very common in regional management.

(iii) Poor time management

Due to lack of integration in management activities as well as due to poor communication and co-operation between different stakeholder groups, the period of implementing an intervention always failed to conform to the planning schedule. Another issue is the timing of initiating a TRM, which is closely linked to local weather conditions. Community members always ask BWDB to avoid the monsoon season for large-scale construction and mud work. But the agency gets its budget during June in the middle of the monsoon. The infelicitous timing for planning and implementation also creates tension in the compensation process, which was one of the main complications in beel Khuksia TRM.

(iv) Knowledge gap

Most community stakeholders did not have and still do not have a clear understanding of the formal mechanism of community stake-holding. The current land requisition and compensation process related to TRM is not clearly understood by the poor, semi-literate, and illiterate marginal communities due to lack of capacity-building (e.g. lack of education), lack of incentives and awareness, and limited access to higher level actors.

(v) Financial complexities

Since affected people never receive proper financial back-up during TRM, they will not be committed to co-operate further. On the other hand, money needs to be invested to operate activities of local-level community WMGs, especially in communication, meeting arrangements and awareness-raising programmes. During the KJDRP project, registered community organizations received some financial support from social research agencies like CEGIS which covered the expenditure (as a token financial contribution to voluntary support to the institutions, mostly for communication and logistic purposes) (CEGIS Citation2003). However, in the post-project stage, there was no financial support to conduct meetings and advocacy programmes. Therefore, the WMGs became ineffective.

Bearing in mind the above limitations, we have tried to explore a way to overcome these barriers and develop a functional Multi-stakeholder process (MSP) for regional delta management in Bangladesh. The suggestions are not only from researcher but also a result of collective participation of different stakeholder groups, including government and non-government organizations, communities and academic experts during field research. Here are specific recommendations distilled from the participants’ assessments of the significance of the participatory outputs:

Proper identification of micro-level stakeholders and their prioritization (based on livelihood security) should be the first step towards an MSP in a sensitive delta management system;

Leadership skills need to be improved at both community and government agency levels, and a mindset change to get collaboration should be facilitated for developing a multi-stakeholder network;

To realize systemic changes in planning and practice, local values and voices should not be ignored in negotiation and in developing collective interest and dealing with changes and challenges successfully;

Strong motivation and advocacy are required in the grass-root level to recognize common and priority interests to the interventions. Local reputed NGOs and civil society organizations need to be involved to deal with conflicts and social values.

Regular interaction between different level of stakeholders and development of local stakeholder platforms can restore trust between local communities and organizations.

A compensation and rehabilitation policy should be revised bearing in mind the lessons learnt from the transformation in local social and financial systems. For example, in the case of TRM, the compensation policy could be modified for more effective use following the local land leasing mechanism.

Local administrative agencies, NGOs, and CSOs can spread a joint persuasive narrative about the importance of co-operation and knowledge co-creation between the three levels as long as there is a clear vision of a sustainable management process.

The effectiveness of practices, efficiency of institutions, and the benefits of a healthy socio-ecological system should be assessed by ensuring regular technical, social, and environmental monitoring in participatory approaches.

Conclusion

Transformation in delta management in Bangladesh has been identified with time-line changes in management approaches and practices. Shifts could be noted: 1) from government management to a community participatory approach; 2) from an individual water-control goal to an integrated management goal; and finally 3) from a hard-core, hydraulic engineering to a local-knowledge based, combined (less structural-more natural) management system. We have found that tidal river management is a process causing the current transition in delta management systems in the southwest coastal Bangladesh, which emphasizes ecological conservation equitably with physical, social and institutional processes. Our research defined a new assessment approach that of a Socio-eco-technical (S-E-T) system to identify a dynamic delta system properly. This could be considered as a conceptual shifting in systems research that will facilitate sustainable management planning in a complex environmental setting over the world.

This study found the socio-economic changes as various positive manors however institutional limitations and stakeholder conflicts are highlighted as major complexities in the current delta management transformation. These need to be addressed in national water management planning in a proper way. Government authorities should be alert to promote sustainable institutional and social management in local and regional levels. Simplification of the compensation procedure and a more active, community-based, institutional support is required for sustainable TRM. TRM has introduced a multi-stakeholder participatory approach instead of a top-down, imposed practice in water management in rural coastal areas. Though the multi-stakeholder participation as a process (MSP) is appeared in the delta management system in Bangladesh, its effectiveness remains limited and its potential largely untapped due to technical, socio-political, and institutional boundaries. It seems that successful participation can happen only when consistent interactions and follow-ups between stakeholders pay attention to a wide range of factors including; the quality of social relations between actors, the positive utilization of differences and even conflicts between actors, and, lastly, creating a more reflexive environment to practice MSPs. This finding also recommends that facilitation of MSPs within and across a multiple-resources based management system is certainly an important mechanism for learning to dealing with management concerns in which various actors with different perceptions and interests have a stake in how the problems are defined and dealt with.

The multi-relational, transformative, system analysis following the Socio-eco-technical system approach will influence future interdisciplinary delta management research and facilitate MSPs in Bangladesh. The participatory research methodology that has been used in this research is also highly appreciated at the community level in the study area and the findings should contribute to increase communication and co-ordination within and in between the delta communities and the government authorities. Our research pointed out the limitations of the participatory approach in re-orienting TRM towards a more integrative socio-eco-technical approach that seems to be more generative in moving towards sustainable delta management at regional level to national level. The suggestions that present study proposed are important for implementing integrated management actions and action research relevant to multi-actor processes in similar deltas. The learning from approached MSP in the defined multi-dimensional transformation framework may create not only possibilities but also a space for changing policy and planning towards sustainable water management goals in Bangladesh and other similar deltas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services (CEGIS), Institute of Water Modelling (IWM), Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB), and Institute of Water and Flood management (IWFM). Demographic and other required information was found from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), National Water Resource Database (NWRD), PDO-Integrated Coastal Zone Management office (WARPO), Asian Development Bank, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), some local NGOs, and relevant websites.

2. The sample villages were Arua, Santala, Kismat Santala, Moynapur, Kalicharanpur, Agorhati, Bhorot Bhaina (Keshobpur Upazilla, Jessore), Kapalia, Manoharpur, Nehalpur, Balidaha, Pachakuri (Monirampur Upazilla, Jessore).

References

- Ahammed R, Harvey N. 2004. Evaluation of environmental impact assessment procedures and practice in Bangladesh. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 22(1):63–78.

- Amir MSI, Khan MSA, Khan MMK, Rasul MG, Akram F. 2013. Tidal river sediment management: a case study in Southwestern Bangladesh. Int J Civil Sci Eng World Acad Sci Eng Technol. 7(3):861–871.

- Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C. 2002. Navigating social-ecological systems: building resilience for complexity and change. Ecol Soc. 21(1):1–15.

- Brouwer H, Woodhill J, Hemmati M, Verhoosel K, van Vugt S. 2015. The MSP guide; How to design and facilitate multi-stakeholder partnerships, Centre for development innovation. The Netherlands: Wageningen University.

- Bukowski J. 2016. A “new water culture” on the Iberian Peninsula? Evaluating epistemic community impact on water resources management policy. Environ Plann C. 35(2):239–264. doi:10.1177/0263774X16648333.

- CEGIS. 2003. Monitoring and integration of the environmental and socio-economic impacts of implementing the tidal river management option to solve the problem of drainage congestion in KJDRP area. Dhaka:BWDB.

- CEGIS. 2007. Environmental and social impact assessment of the proposed project ‘Removal of drainage congestion from the beels adjacent to Bhabadaha area under Jessore District (phase-1). Dhaka:Bangladesh Water Development Board.

- CEGIS. 2008. Compensation mechanism for a tidal basin during operation of tidal river management (TRM) in KJDRP. Dhaka:Bangladesh Water Development Board.

- Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services (CEGIS). 2014. Monitoring and evaluation of the environmental, social and institutional development for drainage improvement of KJDRP under South West area integrated water resources planning and management project (SWAIWRPMP). Dhaka:Bangladesh Water development Board (BWDB).

- Chambers JK. 2002. Dynamics of dialect convergence. J Sociolinguistics. 6(1):117–130. doi:10.1111/1467-9481.00180.

- Cundill G. 2010. Monitoring social learning processes in adaptive co-management: three case studies from South Africa. Ecol Soc. 15(3):28.

- de Die L 2013. Tidal river management: temporary depoldering to mitigate drainage congestion in the southwest delta of Bangladesh. MSc Thesis. Water Resources Management group, Wageningen University, Netherlands.

- Dewan C, Mukherji A, Buisson MC. 2015. Evolution of water management in coastal Bangladesh: from temporary earthen embankments to depoliticized community-managed polders. Water Int. 40(3):401–416.

- Duyne JE. 1998. Local initiatives: people’s water management practices in rural Bangladesh. Dev Policy Rev. 16(3):265–280. doi:10.1111/1467-7679.00064.

- EGIS I. 2001. Environmental and social management plan for Khulna Jessore drainage rehabilitation project (Hari river system). Dhaka: Ministry of Water Resource.

- Gain AK, Ashik-Ur-Rahman M, Vafeidis A. 2019a. Exploring human-nature interaction on the coastal floodplain in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta through the lens of Ostrom’s social-ecological systems framework. Environ Res Commun. 1:051003. doi:10.1088/2515-7620/ab2407

- Gain AK, Benson D, Rahman R, Datta DK, Rouillard JJ. 2017a. Tidal river management in the South West Ganges-Brahmaputra delta: moving towards a transdisciplinary approach? Environ Sci Policy. (75):111–120. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.05.020.

- Gain AK, Mondal MS, Rahman R. 2017b. From flood control to water management: a journey of Bangladesh towards integrated water resources management. Water. 9(1):55. doi:10.3390/w9010055.

- Gain AK, Rahman MAU, Benson D. 2019b. Exploring institutional structures for tidal river management in the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta in Bangladesh. DIE ERDE. 150(3):184–195. doi:10.12854/erde-2019-434.

- Geels FW, Kemp R. 2007. Dynamics in socio-technical systems: typology of change processes and contrasting case studies. Technol Soc. 29:441–455.

- Hajer M, Nilsson M, Raworth K, Bakker P, Berkhout F, de Boer Y, Rockström J, Ludwig K. 2015. Beyond cockpit-ism: four insights to enhance the transformative potential of the sustainable development goals. Sustainability. 7:1651–1660.

- Haque KNH, Chowdhury FA, Khatun KR. 2015. Participatory environmental governance and climate change adaptation: mainstreaming of Tidal River management in South-west Bangladesh. In: Ha H, editor. Land and disaster management strategies in Asia. Vol. 3; p. 189–208. doi:1007/978-81-322-1976-7_13.

- Institute of Water Modelling (IWM). 2014. Monitoring and evaluation of the hydrological and conditions of rivers and drainage problems of beels in the KJDRP area for the planning of drainage improvement measures. Final Report. Dhaka (Bangladesh): BWDB.

- Islam SN, Gnauck A. 2008. Mangrove wetland ecosystems in Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta in Bangladesh. Front Earth Sci China. 2:439–448. doi:10.1007/s11707-008-0049-2

- Ison R, Watson D. 2007. Illuminating the possibilities for social learning in the management of Scotland’s water. Ecol Soc. 12(1):21. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss1/art21/

- IWM. 2005. Monitoring of hydrological and hydraulic parameters on tidal river management under KJDRP area. Final Report. Dhaka. Bangladesh: BWBD.

- IWM. 2007. Monitoring the effects of beel khuksia TRM basin and dredging of hari river for drainage improvement of Bhabodah Area. Dhaka (Bangladesh):BWDB.

- Jakobsen F, Haque AKMZ, Paudyal GN, Bhuiyan MS. 2005. Evaluation of the short-term processes forcing the monsoon river floods in Bangladesh. Water Int. 30(3):389–399.

- Khadim FK, Kar KK, Halder PK, Rahman M, Morshed M. 2013. Integrated water resources management (IWRM) impacts in South West Coastal Zone of Bangladesh and Fact-Finding on Tidal River Management (TRM). J Water Resour Prot. 5:953–961.

- Kloezen WH, Mollinga PP. 1992. Opening closed gates: recognizing the social nature of irrigation artifacts. In: Diemer G, Slabbers J, editors. Irrigators and engineers. Amsterdam: Thesis Publishers; p. 53–64.

- Malena C. 2004. Strategic partnership: challenges and best practices in the management and governance of multi-stakeholder partnerships involving UN and civil society actors, background paper for the multi-stakeholder workshop on partnerships and UN-civil society relations. Pocantico (NY), www.unece.org.

- Manson S, O’Sullivan D. 2006. Complexity Theory in the Study of Space and Place. Environ Plann A. 38(4):677–692.

- Manson SM. 2001. Simplifying complexity: A review of complexity theory. Geo-forum. 32:405–414.

- Masud MMA, Moni NN, Azadi H, Van Passel S. 2018. Sustainability impacts of tidal river management: towards a conceptual framework. Ecol Indic. 85:451–467. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.10.022

- Mollinga P. 2003. On the Waterfront: water distribution, technology and agrarian change in a South Indian canal irrigation system. Hyderabad (India): Wageningen University Water Resources series 5 Orient Longman.

- Mutahara M, Haque A, Khan MSA, Warner JF, Wester P. 2016. Development of a sustainable livelihood security model for storm-surge hazard in the coastal areas of Bangladesh. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment. (30):1301–1315. doi:10.1007/s00477-016-1232-8.

- Mutahara M, Warner J, Khan MSA. 2019. Analyzing the coexistence of conflict and cooperation in a regional delta management system: Tidal river management (TRM) in the Bangladesh delta. Environ Policy Governance. doi:10.1002/eet.1863

- Mutahara M, Warner JF, Wals AEJ, Khan MSA, Wester P. 2017. Social learning for adaptive delta management: Tidal river management in the Bangladesh Delta. Int J Water Resour Dev. doi:10.1080/07900627.2017.1326880

- Nowreen S, Jalal MR, Khan MSA. 2014. Historical analysis of rationalizing South West coastal polders of Bangladesh. Water Policy. IWA Publishing. 16:264–279.

- Pahl-Wostl C. 2006. The importance of social learning in restoring the multi-functionality of rivers and floodplains. Ecol Soc. 11(1):10. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art10/

- Pahl-Wostl C. 2007. The implications of complexity for integrated resources management. Environ Model Software. 22:561–569.

- Pattberg P, Widerberg O. 2016. Transnational multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: conditions for success. Ambio. 45:42–51. doi:10.1007/s13280-015-0684-2

- Paul A, Nath B, Abbas MR. 2013. Tidal river management (TRM) and its implication in disaster management: A geospatial study on Hari-Teka river basin, Jessore, Bangladesh. Int J Geomatics Geoscii. 4(1):125–135.

- Pekkarinen S, Harmaakorpi V. 2006. Building regional innovation networks: the definition of an age business core process in a regional innovation system. Reg Stud. 40(4):401–413.

- Renaud FG, Syvitski JPM, Sebesvari Z, Werners SE, Kremer H, Kuenzer C, Ramesh R, Jeuken A, Friedrich J. 2013. Tipping from the Holocene to the Anthropocene: how threatened are major world deltas? Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 5:644–654. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2013.11.007

- Rouillard JJ, Benson D, Gain AK. 2014. Evaluating IWRM implementation success: are water policies in Bangladesh enhancing adaptive capacity to climate change impacts? Int J Water Resour Dev. 30(3):515–527.

- Roy K, Gain AK, Mallick B, Vogt J. 2017. An assessment of social, hydro-ecological and climatic changes in the South-West coastal region of Bangladesh. Reg Environ Change. 17(7):1895–1906. doi:10.1007/s10113-017-1158-9.

- Sarker MH. 2004. Impact of upstream human interventions in the morphology of Ganges Garai System; The Ganges Water Diversion: environmental effect and implications. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; p. 49–80.

- Seijger C, Datta DK, Douven W, van Halsema G, Khan MF. 2019. Rethinking sediments, tidal rivers and delta livelihoods: tidal river management as a strategic innovation in Bangladesh. Water Policy. 21:108–126. doi:10.2166/wp.2018.212

- Shampa and Pramanik MIM. 2012. Tidal river management (TRM) for selected coastal area of Bangladesh to Mitigate Drainage Congestion. Intl J Sci Technol Res. 1(5):1–6.

- Sol J, Wals AEJ. 2015. Strengthening ecological mindfulness through hybrid learning in vital coalitions. Cult Stud Sci Educ. 10(1):203–214. doi:10.1007/s11422-014-9586z.

- Tukker A, Butter M. 2007. Governance of sustainable transitions; about the 4 (0)ways to change the world. J Clean Prod. 15:94–103.

- Tutu AUA. 2005. River Management in Bangladesh: a people’s initiative to solve waterlogging. Special issue: Society and poverty reduction, participatory learning and action. Vol. 51. International Institute of Environment and Development (IIED), Endsleigh street, London WC1H ODD,UK.

- Uyarra E, Flanagan K, UK Edurne Magro E, Wilson JR, Sotarauta M. 2017. Understanding regional innovation policy dynamics: actors, agency and learning. Environ Plann C. 35(4):559–568. journals.sagepub.com/home/epc. doi:10.1177/2399654417705914.

- Van Staveren MF, van Tatenhove JPM. 2016. Hydraulic engineering in the social-ecological delta: understanding the interplay between social, ecological, and technological systems in the Dutch delta by means of ‘delta trajectories’. Ecol Soc. 21(1):8.

- Van Staveren MF, Warner JF, Khan MSA. 2017. Bringing in the tides. From closing down to opening up delta polders via Tidal river management in the southwest delta of Bangladesh. Water Policy. 19(1):147–164. doi:10.2166/wp.2016.029.

- Vincent LF. 1997. Irrigation as a technology, irrigation as a resource: A Socio-technical Approach to irrigation. Inaugural lecture, Wageningen (agriculture) University, Wageningen, Netherland.

- Warner J. 2006. Multi-Stakeholder platforms for integrated catchment management – more sustainable participation? Int J Water Resour Dev. 22(1):15–35.

- Warner J. 2010. Integration through compartmentalization? Pitfalls of poldering in Bangladesh. Nat Culture. 5(1):65–83.

- Wates N. 2000. The community planning handbook: how people can shape their cities, towns & villages in any part of the world. London: Earthscan. http://www.earthscan.co.uk

- Wesselink A, Warner J, Syed MA, Chan F, Tran DD, Huq H, Huthoff F, Le Thuy N, Pinter N, Van Staveren M, et al. 2015. Trends in flood risk management in deltas around the world: are we going ‘soft’? Int J Water Governance. 4:25–46.

- Wester P, Bron J 1996. Coping with water: water management in flood control and drainage systems in Bangladesh. [accessed 2012 October 10]. edepot.wur.nl/78392.

- Wood GD. 1999. Contesting water in Bangladesh: knowledge, right and governance. J Int Dev. 11(5):731–754.

- Woodhill AJ. 2004. Dialogue and trans-boundary water resources management: towards a framework for facilitating social learning. In: Langaas S, Timmerman JG, editors. The role and use of information in european transboundary river basin management. London: IWA Publishing; p. 44–59.

- Young OR, Berkhout F, Gallopín GC, Janssen MA, Ostrom E, van der Leeuw S. 2006. The globalization of socio-ecological systems: an agenda for scientific research. Global Environ Change. 16(3):304–316.