Abstract

Environmental education (EE) deals with environmental issues that involve diverse values and perspectives. Environmental issues need to be explored within an integrated framework while considering the aim of EE, which is to achieve a sustainable society and life. However, EE has overlooked the economic aspects of environmental issues and the subjectivity of learners. This study compared two frames (economic, using monetary units, and environmental, using biophysical units) and measured their effects on variables related to perceived environmental awareness, i.e. awareness of the issue and decision making. The results showed that the economic frame was more effective at increasing awareness of the issue, whereas the environmental frame was more effective at improving decision making. These findings suggest that the economic frame is needed for delivering information about environmental issues and enhancing the desired outcomes of EE.

Introduction

Environmental education (EE) has become even more critical over time: as environmental problems have become more severe, the need for environmental protection has increased. It is necessary to investigate ways to deal with environmental problems in order to identify appropriate problem-solving strategies. It is essential to understand that environmental problems are not “the problems of the environment” but “the problems of humans who deal with the environment” (Lee Citation2000b). Environmental problems have been mainly addressed through the natural sciences, and students’ understanding of them has heavily relied on a natural scientific approach. This has been the case even though EE should also help students gain a social scientific understanding of environmental issues (Lundholm Citation2011). Today’s environmental problems are embedded within societies that contain diverse values and perspectives. EE should consider the diversity of our lives and deal with environmental problems through both natural and social scientific approaches (Mappin and Johnson Citation2005). However, EE has been considered a subheading of science education even though it involves more than delivering scientific knowledge (Saylan and Blumstein Citation2011). Because environmental problems are related to mankind, all aspects of human lives are part of environmental problems. Therefore, the issues addressed in EE have been recognized as social dilemmas, which can generate conflict (Culen Citation1998; Lundholm Citation2011; Sternäng and Lundholm Citation2012).Footnote1

Environmental issues involve various values, such as economic growth and environmental conservation. Because environmental issues concern human lives, they cannot be fully understood without considering the learners in the education context. The process of educating people requires a balanced perspective, one that takes into account the relationship between issues and learners. Because learners have different backgrounds, they tend to understand environmental issues differently. It is difficult to decide which decisions are truly environmentally friendly in a given context without taking different values and perspectives into account. Which behaviors are environmentally friendly, and who decides that they are: experts, teachers, or students? (Uzzell Citation1999; Lee Citation2001) EE has not paid much attention to these questions because many EE programs emphasize only the environmental behavior itself without considering learners’ perspectives and the context. EE should focus on helping learners understand the environmental issues at hand and make decisions that align with their values (Hug Citation1980; Kolstø Citation2005; Sternäng and Lundholm Citation2012).

EE aims to foster sustainable society and life (Ministry of Education Citation2015; Kwon et al. Citation2016).Footnote2 To accomplish this goal, it is necessary to understand environmental issues within a framework that considers the environment, society, and the economy, because these are integrated aspects of our lives (Luke Citation2001; Kwon et al. Citation2016; Cincera et al. Citation2019). The environment includes natural and social contexts and the complex relationships within the social-ecological system. Even though these aspects are connected or overlapping, they have been addressed separately in EE (Giddings, Hopwood, and O’Brien Citation2002). EE has focused only on ecological reasons (Kim Citation2000) and treated the natural and social environments as if they were dichotomous (Schultz and Zelezny Citation2003). Ecological language that only focuses on ecological justifications overlooks the economic perspective and prevents us from understanding its relevance for the environment (Røpke Citation2004; Mappin and Johnson Citation2005; Lundholm Citation2011). As a result, the economic domain has been neglected in EE, and its role remains unclear for both teachers and students (Berglund and Gericke Citation2016).

The notion of responsible environmental behavior (REB) has been discussed, and it has been used as an important tool in EE. However, REB has been criticized for not being an educational instrument and for focusing on behaviors while neglecting the learner’s context and understanding (Mappin and Johnson Citation2005). Lee and Kim (Citation2002) highlighted these problems with REB and suggested focusing on subjective and responsible environmental behavior to capture learners’ awareness and intentions. Previous studies in social science and communication have concentrated on which interventions are effective, focusing only on the result (Asensio and Delmas Citation2015). However, from an educational perspective, awareness and intention are as important as the result. Thus, this study focuses on learners’ subjective awareness and intentions using the notion of perceived environmental awareness.

This study adds the neglected economic domain to EE and poses the question: Which information frame is useful for helping learners become aware of an environmental issue? In framing theory, an issue is interpreted differently from various perspectives, and it is assumed that the meaning can vary depending on the frame (Chong and Druckman Citation2007). This study used framing theory by comparing the environmental frame (biophysical units), which is commonly used in EE, with the economic frame (monetary units), which is often neglected. The effect of each frame was measured through seven dependent variables related to environmental awareness (awareness of the issue and decision making). The measurement tool was constructed to reflect the subjectivity of learners using the notion of perceived environmental awareness. This study addresses two research questions. First, what are the effects of using each frame to convey information about environmental costs on awareness of the issue? Second, what are the effects of each frame on decision making? Through exploring the effects of using different frames to present information, this study analyzed which information frame is more useful for helping learners raise their awareness of environmental issues and for encouraging them to participate in related activities.

Environmental cost information framing

This study assumes that information affects awareness. Many studies of messaging have shown that awareness varies based on how information is presented (Kahneman and Tversky Citation1979, Citation1984; Loroz Citation2007; Van de Velde et al. Citation2010; Bolderdijk et al. Citation2013; Spence et al. Citation2014). This study focuses on cost information. Cost is understood as opportunity cost, which implies the loss of benefits. Opportunity cost is a core economic concept that enables us to recognize the loss of benefits inherent in environmental issues. It can ease people’s understanding of relevant concepts, such as energy use (Ofgem Citation2011; Spence et al. Citation2014), and is also used for understanding socioeconomic phenomena (Davies and Lundholm Citation2012). Biasutti and Frate (Citation2017) noted that the role of the economic domain in sustainable development is to show impacts on the environment and society. Opportunity cost reveals the interrelationships involved in an issue, based on conflicts that occur between areas related to the environment. Cost information is presented to learners as a perceived trade-off among areas, providing critical insights and detailed consideration of the concept of sustainability (Corney Citation2001; Yamashita, Hayes, and Trexler Citation2017).

To deal with cost information, it is necessary to distinguish among environmental values. Hargrove (Citation1992) divided environmental values into anthropocentric and nonanthropocentric and further divided them into instrumental and intrinsic values (see ). The distinction between anthropocentric and nonanthropocentric values depends on the agents of evaluation, and the distinction between instrumental and intrinsic values is based on whether they provide useful value or have independent inherent value (Ahn et al. Citation2009). In economics, economic value is divided into use value and non-use value (see ) (Turner Citation1999). Use value is defined through the direct and indirect use of goods and services; option values available in the future are also classified as use values. Bequest value reflects availability to future generations, and existence value depends on the mere existence of a good, not the utility of using it (Kwak and Shin Citation2015).Footnote3

Table 1. Classification of environmental values (adapted from Hargrove Citation1992).

Table 2. Classification of economic values (adapted from Turner Citation1999).

These various categories make it difficult to estimate environmental values. For example, interpreting the total environmental value and the economic value as equal may result in an underestimation of the environmental value. Therefore, it is necessary to estimate the value according to the goal of the evaluation, e.g. economic efficiency or environmental health (Kwak and Shin Citation2015). This study used the results of previous studies that have calculated environmental values in the Korean context (Kim et al. Citation2009; Lee Citation2010; Lee et al. Citation2011; Chae et al. Citation2012). The environmental cost information used in this study included direct and indirect use values among the anthropocentric instrumental values, which were reflected in the information used in the experimental questionnaire.

The notion of frame has been defined in various ways. Tversky and Kahneman (Citation1981) defined frame as a concept related to decision-makers’ behaviors, results, and selections. Entman (Citation1993) used framing as a concept involving selection and salience in the communication of texts. Nisbet (Citation2009) considered it to be an interpretive concept related to what is problematic, who is responsible, and what to do in communication. The concept of frame can be summarized as a notion used to emphasize, select, or exclude the information that the provider intends to convey on an issue, such as a specific scope, subject, or interest. Framing changes attitudes and behavioral intentions toward issues (Loroz Citation2007; Van de Velde et al. Citation2010; Spence et al. Citation2014) and, as a result, framing effect has emerged as an important research concept. A seminal paper in the framing literature reported that the preferences of subjects changed based on whether loss or gain framing was used (Kahneman and Tversky Citation1979). Druckman (Citation2001) explained the framing effect by dividing it into equivalent and emphasis frames. Equivalency framing is focusing on the portrayal of positive and negative frames of the same information, and emphasis framing is focusing on a potential subset of relevant considerations (Druckman Citation2001). Framing effects focus on changes that result from qualitative differences in information that can affect an individual’s interest (Druckman Citation2004). This study noted that the costs associated with environmental issues can be described using either an environmental or economic frame (Pimentel, Zuniga, and Morrison Citation2005; Pimentel Citation2009; Bolderdijk et al. Citation2013; Spence et al. Citation2014). These two frames can be seen as emphasis frames, in which environmental and economic frames represent a subset of the same issue. The two frames were used as the independent variable in the experiment.

Environmental awareness

The Tbilisi Declaration defined the objectives of EE using five categories: awareness, knowledge, attitude, skills, and participation (UNESCO. Citation1977). The notion of awareness was introduced as: “to help social groups and individuals acquire an awareness of and sensitivity to the total environment and its allied problems” (UNESCO. Citation1977 p26). Awareness has been one of the objectives of EE. Environmental awareness can be seen as a process in which the recipient accepts and internalizes external information about environmental issues. Given that environmental issues involve stakeholders with varying priorities and objectives (Kiker et al. Citation2005), environmental awareness needs to be measured and addressed based on the situation and context at hand. Environmental awareness is subjective, embedded within situations and contexts, rather than objective information that is independent of the recipients. At the same time, EE should not just provide information; it should help individuals understand information (Wi and Chang Citation2019). Therefore, the concept of perceived factors needs to be emphasized. The term perceived in environmental awareness concerns the process of evaluating and constructing the stimuli provided by the environment. This idea suggests that the external environment loses its meaning unless the recipients of information perceive it (Meijer, Hekkert, and Koppenjan Citation2007). Decision making is also mentioned as one of the goals of EE, along with making a sustainable society and life. EE should help learners make prudent decisions when faced with environmental and social dilemmas (Lee Citation2000a; Lundholm Citation2011; Sternäng and Lundholm Citation2012; Ignell, Davies, and Lundholm Citation2019). Prudent decision making should account for awareness of the issue. This study used decision making as a concept related to this awareness. The two concepts have been researched in the environmental field as well as in marketing, economics, and others (Macdonald and Sharp Citation2000; Ofori and Kien Citation2004; Xu, Prybutok, and Blankson Citation2019). The two concepts are related, according to those studies, and this study chose the two concepts as dependent variables. Environmental awareness can be a relevant subjective attribute of learners (Lee and Kim Citation2002), and decision making that accounts for learners’ environmental awareness can be a meaningful variable (Hong and Lee Citation2008).

This study used seven subquestions to examine the two research questions. The first research question (what are the effects of using each frame to convey information about environmental costs on awareness of the issue?) inquires into awareness of the issue. Its four subquestions focus on perceived certainty, perceived tangibility, perceived danger, and perceived significance. For the second research question (what are the effects of each frame on decision making?), we proposed subquestions about willingness to participate, perceived decision difficulty, and perceived decision confidence.

Certainty and tangibility have been dealt with in some EE literature (Lee and Fortner Citation2000; Fortner et al. Citation2000; Lee and Fortner Citation2006). Certainty is related to what is contained or excluded in the information (Guenther, Froehlich, and Ruhrmann Citation2015). Incomplete information is considered the main source of uncertainty (Lipshitz and Strauss Citation1997). Uncertainty is one of the characteristics of environmental issues like climate change (Steffen Citation2011). Many environmental scientists try to overcome it. This is why certainty is vital as one of the awareness variables. Certainty was chosen as a dependent variable to show the effectiveness of each frame; that is, which frame is more helpful for becoming aware of the issue. Tangibility can be explained as an inherited characteristic of a phenomenon (Hellén and Gummerus Citation2013). An observer’s perception by their sensory organs is also defined as tangibility (Lee Citation2000a). Tangibility can be summarized as an aspect of the phenomenon itself and an attribute sensed by observers. It can be used as a criterion to compare the frames (Hellén and Gummerus Citation2013). Danger is about cognitive appraisal and emotional reaction (Herzog and Kutzli Citation2002). Certainty is associated with danger, and danger has a significant impact on awareness of an issue that contains uncertainty (Lipshitz and Strauss Citation1997). It can be hypothesized that the certainty, tangibility, and danger associated with the issues are linked to the significance of the issues (Lee Citation2000a).

Willingness to participate, which can be a proxy for decision making, is related to perceived decision difficulty and perceived decision confidence. Decision difficulty is influenced by information type and format (Broniarczyk and Griffin Citation2014) and is reinforced when comparing options (Goodman et al. Citation2013). It is related to an individual’s internal experience with making decisions and shows the difficulty of choosing among trade-offs in the decision process (Hanselmann and Tanner Citation2008). Decision confidence is related to information presentation (Phillips, Prybutok, and Peak Citation2014). People can achieve decision confidence when conflicts in decision making are low (De Neys, Cormheeke, and Osman Citation2011).

Environmental awareness and EE

The concept of perceived is an important factor when considering the learner’s perspective in EE and the process of awareness. Learners should perceive the meaning of the action by themselves and decide what to do based on it (Kim Citation2010), rather than following behavior that someone else suggests is desirable. Choosing the option provided by experts or teachers rather than one developed by students themselves could be the worst possible result of EE from an educational perspective (Lee Citation2001). EE should help learners make prudent decisions about environmental and social dilemmas, not propagate someone else’s decision (Lee Citation2000a; Lundholm Citation2011; Sternäng and Lundholm Citation2012; Ignell, Davies, and Lundholm Citation2019). EE needs to reduce uncertainty and help develop an awareness of the issues rather than focusing on ways to increase participation without encouraging awareness. In this context, EE must focus on the term perceived when exploring awareness of the issue and decision making.

The problem-solving perspective of EE ignores areas that are unrelated to the problem or emphasize only behavioral changes (Mappin and Johnson Citation2005). An emphasis on solving problems may not be able to capture the original meaning of EE, and one may criticize assertions that EE is cost-effective for problem solving (Kim Citation2013). The issues addressed in EE concern conflicts among two or more norms (or knowledge), and in many cases learners do not view the issue from an environmental perspective (Lee Citation2007). For prudent decision making, EE should cultivate an environmental viewpoint that allows people to approach a specific issue from an environmental perspective. Furthermore, Kang (Citation2019) asserted that a praxis that includes knowledge and practice should be desired in EE. EE should promote an environmental awareness that leads to developing an environmental perspective and should help shape the perspective the learner uses to recognize and make decisions about the issue, rather than focusing only on the decision result. This study sought to clarify which information frames help learners form their awareness.

Materials and methods

Research design

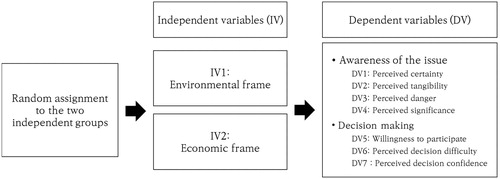

To measure the effects of environmental cost information frames on environmental awareness, we used a questionnaire and a factorial design with one independent variable. A factorial design with one independent variable measures the effects on a dependent variable under each condition of the independent variable. In this study, the environmental cost information was treated as the independent variable under two conditions, the environmental frame and the economic frame. The effect of each frame was measured through seven dependent environmental awareness variables that measure awareness of the issue and decision making after the experiment: perceived certainty, perceived tangibility, perceived danger, perceived significance, willingness to participate, perceived decision difficulty, and perceived decision confidence. Reliability was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha. The seven variables are divided among awareness of the issue and decision making. The coefficient alpha of the four variables under awareness of the issue is 0.722 and the coefficient alpha of the three variables under decision making is 0.757. The two coefficients are larger than .7, thus the reliability of the measurement tool is acceptable.

In this experiment, students were randomly assigned to either the environmental frame or the economic frame group. Random assignment was used to control variables other than the framing manipulation. The experiment was designed to explore the causal relationship between framing and awareness and to measure differences in the effects according to the frame used (see ). This study design can explain the issue and measure differences in environmental awareness in order to compare the two frames (environment and economy), according to Chong and Druckman (Citation2007).

Research hypotheses

This study measured seven dependent variables under different framings of environmental cost information. Learners have been taught to behave as homo economicus and are well-accustomed to the market-oriented system through their education and social atmosphere (Kim Citation2000). EE has focused on delivering an ecological language to students. This has caused a gap between the economic reality that they live in and the ecological lifestyle taught in the classroom (Kim Citation2000, Citation2002). EE has, however, overlooked the interrelationship between the economy and the environment because it has portrayed that relationship as dichotomous (Schultz and Zelezny Citation2003). For EE to achieve its goals of a sustainable society and life (Ministry of Education Citation2015; Kwon et al. Citation2016), it needs to adopt an integrated approach that overcomes the gap between the economy and the environment. We have not paid enough attention to economic aspects within the sustainability dialogue (Kim Citation2006). In this context, quantified economic information should play a key role in recognizing the importance of the environment (Lee Citation2005). Therefore, this study set forth one-way hypotheses that the economic frame will be more effective than the environmental frame in helping students be aware of environmental issues and make decisions (see and ).

Table 3. Four hypotheses for research question 1.

Table 4. Three hypotheses for research question 2.

Content validity confirmation

Two types of reviews were conducted, twice each, to assess the validity of the experimental tool: two face-to-face reviews with a professor specializing in EE and a PhD researcher specializing in EE and two group reviews that included three PhD students in EE and two high school teachers. Revisions made after the reviews were confirmed twice with two colleagues, a doctoral student and a master’s student in EE, to enhance content validity. The validity of each reading and the questions was checked, and the students’ understanding of the entire questionnaire was confirmed for validity. To this end, a pilot test was conducted, and the content of the questionnaire was modified accordingly.

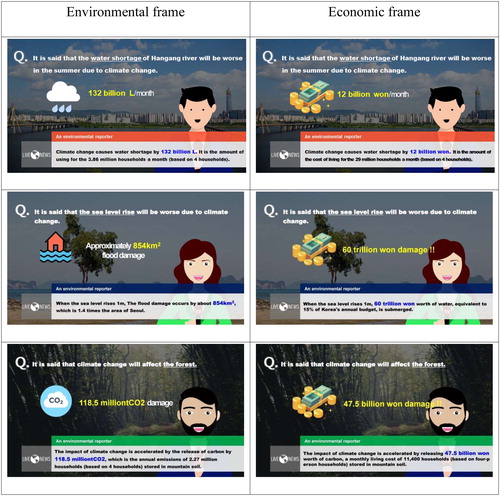

Among the themes included in the pilot test, damage to agricultural production was discarded because the distinction between the environment and economic frames was unclear. In the final experiment, cost information on water shortages, sea-level rise, and forest destruction from climate change was presented. The amount of donation that would indicate a willingness to participate was raised from KRW 5,000 to KRW 10,000, reflecting the students’ opinions that the pilot test’s burden was too small.

Experimental questionnaire

The experimental questionnaire consisted of readings about environmental cost information and questions that assessed the environmental awareness variables (awareness of the issue and decision making). The reading material provided monetary value information in the economic frame and biophysical unit information in the environmental frame. The cost information used in the readings was from Kim et al. (Citation2009), Lee (Citation2010), Lee et al. (Citation2011), and Chae et al. (Citation2012). To control the amount of information included in each frame, the material was presented in the same arrangement and configuration, other than the frame change (see ). The information content included the cost of water shortages, sea-level rise, and deforestation caused by climate change. Each group was provided three pieces of information related to environmental cost that were presented in either the environmental or economic frame. The information was designed in a news style to help learners accept the information easily.

The questions about awareness of issues and decision making were adapted from Lee (Citation2000a, Citation2000b). The concepts of the perceived variables were extracted from Lee (Citation2000b) and the detailed questions were adapted from Lee (Citation2000a). Lee (Citation2000a) used various concepts related to environmental awareness in his survey, including certainty and tangibility. This study selected the variables from among them and matched the concepts to the questions. The response options were displayed on a 6-point scale to prevent median answers. Detailed questions were structured (see ).

Table 5. Dependent variables and questionnaires.

Participants and issue subject

The participants were recruited based on suitability. Lee (Citation2001) suggested that teaching decision making involving complex social dilemmas would be appropriate for junior high school students and high school students. Choi et al. (Citation2007) supported this claim for high school students in Korea after considering their cognitive level. Therefore, this study selected first-year high school students (15–16 years of age) as participants.

Environmental awareness was measured through a hypothetical situation designed to prevent climate change damage. Climate change is a representative environmental issue that leads to irreversible outcomes (Rockström et al. Citation2009). It involves uncertainty and intangibility in people’s awareness, which produces ambiguity and misconceptions (Lee Citation2000a; Lee and Fortner Citation2000). It is also considered a collective action problem, one typically understood as a dilemma (Jagers et al. Citation2020). Therefore, diverse stakeholders including scientists, administrators, and citizens are involved in this topic (Corney Citation2001). For these reasons, we selected climate change as the issue that the experiment would address.

Data collection and analysis

The sample size for each group was set at 70 after considering the errors and standard deviations of the pilot test. The pilot test was conducted with a small sample at H high school in Gyeonggi Province (18 students). The same procedure was followed in the main experiment to obtain reliable results. After the pilot test, some parts of the questionnaire were modified, as mentioned above, including the amount of the donation. A total of 206 students participated in the main experiment from C high school in Gyeonggi Province (82 students, male = 32, female = 50) and Seoul M high school (124 students, all females) from September 29 to October 13, 2017. Data collection considered the error rate and missing values.

C high school in Gyeonggi Province is a general public high school that has slightly lower achievement than the national average. Seoul M high school is also a general high school; it has a higher level of achievement than the national average. The experiment was conducted through the teacher in charge of the subject, who was given relevant guidance. To control for external variables such as school characteristics, two experimental groups were randomly assigned to the environmental and the economic frames. Of the 206 responses, 13 cases were excluded because of missing responses. Therefore, 193 (93.69%) of the cases were included in the final sample for the analysis using the environmental frame (n = 79) and the economic frame (n = 114).

The experiment was conducted using a self-reported survey. We provided the reading materials and questionnaire; there was no other intervention. The questionnaire asked students about their understanding through a manipulation check on the reading material.Footnote4 The manipulation of independent variables was confirmed to be appropriate: 77.22% (61 students) of the respondents answered that the environmental frame reading used that frame, and 71.05% (81 students) responded that the economic frame reading used that frame. An independent sample t-test was used to test the mean difference between groups, and a one-tailed test was used to analyze the one-way hypotheses based on the literature review.

Results

Research question 1

The first research question was “What are the effects of using each frame to convey information about environmental costs on awareness of the issue?” Four hypotheses were developed (see ). The study examined the descriptive statistics before conducting the statistical tests for each hypothesis.

For perceived certainty, the mean of the economic group (M = 5.01) was higher than the mean of the environmental group (M = 4.71). For perceived tangibility, the mean of the economic group (M = 4.51) was also higher than the mean of the environmental group (M = 4.30). For perceived danger and perceived significance, the means of the economic group (M = 5.11; M = 5.43, respectively) were also higher than those of the environmental group (M = 4.84; M = 5.22, respectively). To determine whether these differences were statistically significant, an independent sample t-test (one-tailed test) was conducted on the group differences in each variable. The results are shown in .

Table 6. The results of the t-test for research question 1.

The descriptive statistics showed the directions of the effects for the four hypotheses. To determine whether the results were statistically significant, t-tests were conducted at the significance level of p < .05. Perceived certainty was statistically significant (tdf = 191 = −2.423, p = .008), so the null hypothesis was rejected and the economic frame was found to be more effective than the environmental frame. Perceived tangibility showed a difference in the descriptive statistics, but this difference was not statistically significant (tdf = 191 = −1.214, p = .113). Therefore, the effect of framing on perceived tangibility was not significantly different for the two groups. There was a statistically significant difference in perceived danger (tdf = 191 = −1.953, p = .026), so the economic frame was found to be more effective than the environmental frame. Perceived significance also showed statistically significant differences (tdf = 191 = −1.751, p = .041), so the null hypothesis was rejected and the economic frame was found to have a more significant effect on perceived significance.

To sum up, these results show that the economic frame was more effective than the environmental frame for three of the four variables. The economic frame and the environmental frame had the same effect on perceived tangibility.

Research question 2

Research Question 2 was “What are the effects of each frame on decision making?” Three hypotheses were developed (see ).

For willingness to participate, the mean of the environmental group (M = 4.58) was higher than the mean of the economic group (M = 4.25). For decision difficulty, which was related to willingness to participate, the mean of the economic group (M = 2.59) was lower than that of the environmental group (M = 2.81). For decision confidence, the mean of the economic group (M = 4.48) was higher than the mean of the environmental group (M = 4.27). To examine the statistical differences, an independent sample t-test (one-sided test) was conducted. The results are shown in .

Table 7. The results of the t-test for research question 2.

Statistical tests were conducted at a significance level of p < .05. For willingness to participate, there was a mean difference of 0.33 between the two groups, but it was in the opposite direction of the hypothesis. Therefore, the null hypothesis was supported (tdf = 189.951 = 1.741, p = .958). However, by setting the direction of the one-tailed test in the opposite direction, the hypothesis could be rephrased as “willingness to participate is higher in the environmental frame group than in the economic frame group.” After doing this, there was a significant statistical difference between the two frames (tdf = 189.951 = 1.741, p = .042). This result suggests that the environmental frame has a greater effect on willingness to participate than the economic frame, although this does not support the original hypothesis. There were no statistically significant differences in decision difficulty (tdf = 191 = 1.042, p = .149) or decision confidence (tdf = 191 = −1.123, p = .131). The results show that the environmental frame and the economic frame had the same effect on decision difficulty and decision confidence.

Discussion

This study explored how we can use the economic domain in EE to pursue the goal of achieving sustainable society and life (Ministry of Education Citation2015; Kwon et al. Citation2016). This study investigated the effects of manipulating the framing for presenting environmental cost information on environmental awareness. The purpose was to extract useful information about the presentation form based on the subjective perceptions of the learners.

The independent variable was the framing of the environmental cost information. Environmental cost information contains opportunity costs and makes students consider sustainability through recognizing trade-offs with other areas (Corney Citation2001; Yamashita, Hayes, and Trexler Citation2017). The information was framed to emphasize environmental and economic domains. The experiment was designed to measure causal differences in the dependent variables based on the framing. Four dependent variables were related to the awareness of the issue (perceived certainty, perceived tangibility, perceived danger, and perceived significance) and three were related to decision making (willingness to participate, decision difficulty, and decision confidence). Environmental awareness is a relevant subjective attribute of learners (Lee and Kim Citation2002). Furthermore, participation is a meaningful variable for considering environmental decision making, including learners’ awareness (Hong and Lee Citation2008). The selected independent and dependent variables were used in experiments that were designed using a one-way factorial method. The experiment was conducted with 206 high school students, a number that took the characteristics of the experiment into consideration.

Based on the experiment’s results, this study confirmed the existence of the framing effect, which asserts that issues can be understood differently and their meanings can differ according to viewpoints (Chong and Druckman Citation2007). Previous studies showed that attitude or behavioral intentions changed according to the framing (Kahneman and Tversky Citation1979, Citation1984; Loroz Citation2007; Van de Velde et al. Citation2010; Bolderdijk et al. Citation2013; Spence et al. Citation2014). Given the assumption that the information affects the dependent variables, both frames are useful for environmental awareness (awareness of the issue and decision making). Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the variables where there is a statistically significant difference between the two frames.

The effect of the economic frame on perceived certainty was significantly greater than that of the environmental frame. Perceived certainty can be defined as the ability of an individual to predict the issue (Milliken Citation1987). It also has been closely related to the causes, consequences, and principles of environmental issues (Fortner et al. Citation2000). Therefore, we can interpret this result as indicating that the economic frame reveals the environmental issue better than the environmental frame and allows the learner to better predict the issue. Perceived danger asked how serious the issue was. Perceived danger is concerned with the damage caused by the issue, cognitive appraisal, and emotional reactions (Herzog and Kutzli Citation2002). The economic frame helps learners recognize the damage of climate change better than the environmental frame. The result can be attributed to the influence of the monetary information presented in the economic frame (rational language), which is more accessible for learners than ecological language (Kim Citation2000, Citation2002). Perceived significance is assumed to be a function of certainty, tangibility, and danger (Lee Citation2000a). In this context, the economic frame that increased perceived certainty and perceived danger also had more influence on perceived significance. However, there was no significant difference between the two frames with respect to perceived tangibility. Perceived tangibility is the possibility of direct experience and observation (Lee Citation2000a) and is considered to be derived from the characteristics of a phenomenon (Hellén and Gummerus Citation2013). The reason differences were not detected between the two frames is that tangibility is related to the issue itself (climate change) rather than to framing.

The effect of the environmental frame on the learners’ willingness to participate was significantly higher than that of the economic frame. We found that the environmental frame was more appealing for the learners and encouraged them to make a hypothetical donation to prevent climate change. This result contradicts the hypothesis we set before the empirical test. This result can be interpreted with the following two points. First, the rational consciousness of economic thinking erodes social rationality, in other words, community participation and responsibility. The literature shows that people tend to behave according to social values rather than economic values in a social context (Choi and Ma Citation2008; Bolderdijk et al. Citation2013; Spence et al. Citation2014). Second, previous studies have shown that gain frames are useful with specific messages and loss frames are effective with uncertain messages (Kim and Kim Citation2017). The information presented in the experiment can be viewed as a loss frame, given that it concerns cost in both the environmental and economic frames. Because the certainty of the environmental frame was significantly lower, students might have perceived it as a more uncertain message. The results can be interpreted as that an uncertain and loss-framed environmental message that is related to social rationality had more impact on willingness to participate, which is consistent with previous research. There was no difference in decision difficulty and decision confidence, which are related to psychological and internal factors. Thus, we can infer that there was no difference in perceptions or psychological effects between the environmental frame and the economic frame.

Implications

This study selected two frames, environmental and economic. The experiment showed that framing had different effects on the environmental awareness variables (awareness of the issue and decision making). The implications for EE can be summarized as follows.

First, this study shows that the economic frame is useful for achieving EE’s goals. Framing focuses on certain elements while ignoring others. Framing leads to different definitions of the same issue and different choices for the same problem (Jachtenfuchs Citation1997). Information presented in different frames affects awareness and changes judgments and behaviors. In EE, it is necessary to use frames to achieve different educational goals. EE aims at prudent decision making that reduces uncertainty and conflict to ensure a sustainable society (Lee Citation2000a; Sternäng and Lundholm Citation2012). The economic frame exhibited a significant effect on perceived certainty, perceived danger, and perceived significance. Thus, the economic frame was shown to be useful for achieving EE’s awareness goal.

Second, the possibility of using monetary information in EE was confirmed. There have been attempts to link environmental and socioeconomic issues in EE (Lundholm Citation2011; Kim et al. Citation2012; Davies and Lundholm Citation2012). The economy has been connected with environmental and socioeconomic issues through subjects like recognition of limitations, possibility of economic growth, and poverty reduction (Berglund and Gericke Citation2016; Biasutti and Frate Citation2017). The economic aspect of EE has dealt with economic subjects rather than the use of monetary information, until now. The results of this study confirmed the possibility of using monetary information. This study shows that a rational viewpoint, such as economic thinking, is needed when dealing with awareness and decision making in EE and that monetary information can be presented in a meaningful educational context.

Third, the economic frame can provide a connection between the natural system and the social system. Recently, EE has focused more on the socioecological system. One approach for understanding the natural system and the social system in an integrated way is to treat the environment as a socioecological system (Kwon et al. Citation2016). Lee (Citation2016) connected the two systems through the unit of event, whereas Russ (Citation2015) connected the two by using the notion of urban to represent the socioecological system. The environmental cost information frame adopts a socioeconomic perspective for recognizing environmental issues. It involves monetary valuation that interprets the natural system in a social system context. Therefore, the economic frame can connect the two systems, and this study shows the effect of its use. The economic frame can be understood as a connection between the natural and social systems in the context of the socioecological system in EE.

Limitations

This study has limitations even though it had valid results. The experiment was conducted on average Korean high school students. However, generalization of the results should take into account the instruments, the units used in the reading material, and improving the experimental design. The results of this study should be interpreted with the understanding that its purpose was exploratory. First, the instruments this study chose are part of awareness and decision making. The range and depth of variables are limited. The seven variables are important for confirming the usefulness of comparing two frames, but they cannot tell all about awareness. Second, the number of units used to explain environmental cost information in the frames was different. The environmental frame used three units (L, km2, tCO2), and the economic frame used one unit (won). Equalizing the number of units used could improve the research’s reliability. Third, this experiment was conducted by comparing two experimental groups directly without a control group, following previous research (Chong and Druckman Citation2007). Having a control group would improve the results of this study. These suggestions could be considered when planning further studies. In summary: further studies are needed to explain why the differences occurred and which frames have more educational effects for learners.

Conclusions

This study explored the effects of using different frames to present the same information. The different frames were selected based on the educational purpose. This study shows that environmental awareness needs to reflect the subjective attributes of the learners, focusing not only on the behavioral result but also on the process of creating an educational meaning for EE. Economic aspects have been overlooked in EE and remain undetermined for both teachers and students (Berglund and Gericke Citation2016). This study shows that the economic frame is equal to or even more effective at creating environmental awareness. Therefore, EE should use the economic frame. Furthermore, the two frames should be merged in the sense that EE must deal with diverse dimensions when designing the contents of EE for effective education.

This study can be considered an exploratory effort to find the difference between the two frames. It confirmed the need to use the economic domain. Future studies are needed to determine whether the result is general by checking each limitation. We cannot confirm whether the same results would have been obtained in context other than Korea. We leave these issues for further studies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Woomi Choi and Mr. Jongmin Park, who are high school teachers, for helping us carry out the survey for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest is reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jinyoung Kang

Jinyoung Kang is a PhD student in the Interdisciplinary Program in Environmental Education at Seoul National University. He is interested in environmental education as pedagogy and policy for environmental education.

Jong Ho Hong

Jong Ho Hong* is a professor in the Graduate School of Environmental Studies at Seoul National University. His main research focuses on environmental and energy economics, benefit-cost analysis, and sustainable development policies. He currently serves as president of the Asian Association of Environmental and Resource Economics.

Notes

1 EE has been dealing with many environmental issues. Climate change and biodiversity stand out. These issues can generate social conflict while trying to prevent or solve them.

2 The Korean Ministry of Education stated this in its formal EE curriculum. Achieving a sustainable society and life can be understood as the main goal of EE in Korea, but it can also be understood as one of the general goals of EE worldwide.

3 You can see the detailed explanation of the value classification on Turner (Citation1999) and Hargrove (Citation1992).

4 This is the manipulation checking question: What do you think is a summary of the reading material? 1) environmental loss occurs because of climate change, 2) economic loss occurs because of climate change

References

- Ahn, S., E., J., Y. Kim, C., H. Lee, and D., H. Bae. 2009. Integration of Environmental Values in Developing Policy Evaluation Techniques I. Seoul: Korea Environmental Institute. [in Korean]

- Asensio, O. I., and M. A. Delmas. 2015. “Nonprice Incentives and Energy Conservation.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (6): E510–E515. doi:10.1073/pnas.1401880112.

- Berglund, T., and N. Gericke. 2016. “Separated and Integrated Perspectives on Environmental, Economic, and Social Dimensions–an Investigation of Student Views on Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 22 (8): 1115–1138. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1063589.

- Biasutti, M., and S. Frate. 2017. “A Validity and Reliability Study of the Attitudes toward Sustainable Development Scale.” Environmental Education Research 23 (2): 214–230. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1146660.

- Bolderdijk, J. W., L. Steg, E. S. Geller, P. K. Lehman, and T. Postmes. 2013. “Comparing the Effectiveness of Monetary versus Moral Motives in Environmental Campaigning.” Nature Climate Change 3 (4): 413–416. doi:10.1038/nclimate1767.

- Broniarczyk, S. M., and J. G. Griffin. 2014. “Decision Difficulty in the Age of Consumer Empowerment.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 24 (4): 608–625. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2014.05.003.

- Chae, Y. R., Y. G. Kim, G. W. Jo, H. J. Jo, and S. Y. Choi. 2012. Economic Analysis of Climate Change in Korea (III). Seoul: Korea Environment Institute. [in Korean]

- Choi, Minsik, and Haeyoung Ma. 2008. “Do Those Who Have More Economic Knowledge Really Make Rational Economic Decisions?: Focusing on Economic Education in Korea.” Korean Social Studies Association 47 (3): 5–34. [in Korean]

- Choi, D. H., Y. A. Son, M. O. Lee, and S. H. Lee. 2007. Environmental Education Teaching and Learning. Seoul: Kyoyookbook. [in Korean]

- Chong, D., and J. N. Druckman. 2007. “Framing Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 10 (1): 103–126. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054.

- Cincera, J., J. Boeve-de Pauw, D. Goldman, and P. Simonova. 2019. “Emancipatory or Instrumental? Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions of the Implementation of the EcoSchool Program.” Environmental Education Research 25 (7): 1083–1104. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1506911.

- Corney, J. R. 2001. “Influence of Textual Hedging and Framing Variations on Decision Making Choices Pertaining to the Climate Change Issue.” PhD diss., The Ohio State University.

- Culen, G. R. 1998. “The Status of Environmental Education with Respect to the Goal of Responsible Citizenship Behavior.” In Essential Readings in Environmental Education, edited by Harold R. Hungerford, 37–46. Champaign, IL: Stipes Pub Llc.

- Davies, P., and C. Lundholm. 2012. “Students’ Understanding of Socio-Economic Phenomena: Conceptions about the Free Provision of Goods and Services.” Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (1): 79–89. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2011.08.003.

- De Neys, W., S. Cromheeke, and M. Osman. 2011. “Biased but in Doubt: Conflict and Decision Confidence.” PloS One 6 (2): 1–10. doi:10.1371/annotation/1ebd8050-5513-426f-8399-201773755683.

- Druckman, J. N. 2001. “The Implications of Framing Effects for Citizen Competence.” Political Behavior 23 (3): 225–256. doi:10.1023/A:1015006907312.

- Druckman, J. N. 2004. “Political Preference Formation: Competition, Deliberation, and the (ir) Relevance of Framing Effects.” American Political Science Review 98 (4): 671–686. doi:10.1017/S0003055404041413.

- Entman, R. M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

- Fortner, R. W., J. Y. Lee, J. R. Corney, S. Romanello, J. Bonnell, B. Luthy, C. Figuerido, and N. Ntsiko. 2000. “Public Understanding of Climate Change: Certainty and Willingness to Act.” Environmental Education Research 6 (2): 127–141. doi:10.1080/713664673.

- Giddings, B., B. Hopwood, and G. O’brien. 2002. “Environment, Economy and Society: Fitting Them Together into Sustainable Development.” Sustainable Development 10 (4): 187–196. doi:10.1002/sd.199.

- Goodman, J. K., S. M. Broniarczyk, J. G. Griffin, and L. McAlister. 2013. “Help or Hinder? When Recommendation Signage Expands Consideration Sets and Heightens Decision Difficulty.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 23 (2): 165–174. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2012.06.003.

- Guenther, L., K. Froehlich, and G. Ruhrmann. 2015. “(Un)Certainty in the News: Journalists’ Decisions on Communicating the Scientific Evidence of Nanotechnology.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 92 (1): 199–220. doi:10.1177/1077699014559500.

- Hanselmann, M., and C. Tanner. 2008. “Taboos and Conflicts in Decision Making: Sacred Values, Decision Difficulty, and Emotions.” Judgment and Decision Making 3 (1): 51–63.

- Hargrove, E. C. 1992. “Weak Anthropocentric Intrinsic Value.” The Monist 75 (2): 183–207.

- Hellén, K., and J. Gummerus. 2013. “Re‐Investigating the Nature of Tangibility/Intangibility and Its Influence on Consumer Experiences.” Journal of Service Management 24 (2): 130–150. doi:10.1108/09564231311323935.

- Herzog, T. R., and G. E. Kutzli. 2002. “Preference and Perceived Danger in Field/Forest Settings.” Environment and Behavior 34 (6): 819–835. doi:10.1177/001391602237250.

- Hong, Sang-Mi, and Jae-Young Lee. 2008. “Effects of Pro-Con Discussion on Students’ Decisions in a Class Introducing Environmental Issues.” Korean Journal of Environmental Education 21 (1): 16–30. [in Korean]

- Hug, J. 1980. “Two Hats.” Science Activities: Classroom Projects and Curriculum Ideas 17 (2): 24–24. doi:10.1080/00368121.1980.9957880.

- Ignell, C., P. Davies, and C. Lundholm. 2019. “A Longitudinal Study of Upper Secondary School Students’ Values and Beliefs regarding Policy Responses to Climate Change.” Environmental Education Research 25 (5): 615–632. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1523369.

- Jachtenfuchs, M. 1997. “Conceptualizing European Governance.” In Reflective Approaches to European Governance, edited by Knud Erik Jørgensen, 39–50. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Jagers, S. C., N. Harring, Å. Löfgren, M. Sjöstedt, F. Alpizar, B. Brülde, D. Langlet, et al. 2020. “On the Preconditions for Large-Scale Collective Action.” Ambio 49: 1282–1296.

- Kang, Jinyoung. 2019. “Environmental Education as an Educational Practice: Focus on Aristotles Phronesis.” Korean Journal of Environmental Education 32 (2): 127–138. [in Korean]

- Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1979. “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk.” Econometrica 47 (2): 263–291. doi:10.2307/1914185.

- Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1984. “Choices, Values, and Frames.” American Psychologist 39 (4): 341–350. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.39.4.341.

- Kiker, G. A., T. S. Bridges, A. Varghese, T. P. Seager, and I. Linkov. 2005. “Application of Multicriteria Decision Analysis in Environmental Decision Making.” Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 1 (2): 95–108. doi:10.1897/IEAM_2004a-015.1.

- Kim, Chankook. 2010. “Development Plan of Energy Climate Change Education.” Journal of Energy and Climate Change Education preliminary issue: 1–5. [in Korean]

- Kim, C., Lee, Sun-Kyung, K., Nam-soo, J., Hyung Son, J., Meejeong, K., Hye-Seon. 2012. “Elementary and Secondary Teachers’ Perception on Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and Formal ESD Cases in Korea.” Korean Journal of Environmental Education 25 (3): 358–373. [in Korean]

- Kim, Chankook. 2013. “Ozone Layer Depletion and Roles of Environmental Education: A Conceptual Inquiry and Practice.” Korean Journal of Environmental Education 26 (1): 94–110. [in Korean]

- Kim, Tae-Kyung. 2000. “An Alternative Approach for Environmental Education to Overcome Free Rider Egoism Based on the Perspectives of Prisoner’s Dilemma Situation.” Korean Journal of Environmental Education 13 (2): 38–50. [in Korean]

- Kim, Tae-Kyung. 2002. “A Theoretical Approach to Oriental Ecological Philosophy for Orthodoxy Korean Thought -Based Environmental Education-Regional Communality and Restoration of People’s Real Life.” Korean Journal of Environmental Education 15 (2): 30–48. [in Korean]

- Kim, Tae-Kyung. 2006. “ESD (Education for Sustainable Development) and ESE (Education for Sustainability & Its Economy) - EE and Its Boundary for Co-Conceptional Approach to Sustainability.” Korean Journal of Environmental Education 19 (3): 67–79. [in Korean]

- Kim, Y. G., Y. R. Chae, G. B. Jang, S. Y. Lee, S. W. Jeon, G. W. Jo, S. E. Ahn, et al. 2009. Economic Analysis of Climate Change in Korea (I). Seoul: Korea Environment Institute. [in Korean]

- Kim, Kyungjin, and Yungwook Kim. 2017. “The Effects of Message Framing and Uncertainty on the Preventive Behavioral Intention: A Focus on Climate Change.” Advertising Research 112: 154–198. [in Korean] doi:10.16914/ar.2017.112.154.

- Kolstø, S. D. 2005. “Assessing the Science Dimension of Environmental Issues through Environmental Education.” In Environmental Education and Advocacy, edited by E. A. Johnson and M. J. Mappin, 207–224. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kwak, S. Y., and J. W. Shin. 2015. Mid-Term Research Plans for the Environmental Valuation. Sejong: Korea Environment Institute. [in Korean]

- Kwon, Youngrak, Jaeyoung Lee, Chankook Kim, JaeJung Ahn, EunJung Seo, Yunhee Nam, Eunwha Park, Soyoung Choi, and Yumin Ahn. 2016. “The 2015 Revised National Curriculum for "Environment" Subject: Major Changes in Contents and Approaches.” Korean Journal of Environmental Education 29 (4): 363–383. [in Korean]

- Lee, Choong-Ki. 2005. “Valuation of Eco-Tourism Resources for DMZ Using a Contingent Valuation Method: International Comparison of Values.” Journal of Tourism and Leisure Research 17 (4): 65–81. [in Korean]

- Lee, D. G. 2007. “Environmental Education and Curriculum Contents.” Proceedings of Korean Society for Environmental Education Conference, June, 146–162. [in Korean]

- Lee, J. H. 2010. “Economics of Extreme Weather Event.” SERI Economy Focus 278: 4–11. [in Korean]

- Lee, J. Y. 2001. “Teaching and Learning Methods of Environmental Decision-Making Education.” Proceedings of Korean Society for Environmental Education Conference, December, 7–15. [in Korean]

- Lee, Jae-Young. 2000b. “Subjectivity in Perception of Environmental Issues and Its Implications for Environmental Education.” Korean Journal of Environmental Education 13 (2): 14–23. [in Korean]

- Lee, Jae-Young. 2016. The Event Centered Environment Exploring. Gongju: Gongju National University Press. [in Korean]

- Lee, H. S., Y. R. Chae, Y. G. Kim, G. W. Jo, Y. Lee, Y. J. Kim, Y. N. Yeom, et al. 2011. Economic Analysis of Climate Change in Korea (II). Seoul: Korea Environment Institute. [in Korean]

- Lee, H. Y., and R. W. Fortner. 2006. “Elementary Students’ Perceptions of Earth Systems and Environmental Issues.” Journal of the Korean Earth Science Society 27 (7): 705–714.

- Lee, J. Y., and R. W. Fortner. 2000. “Classification of Environmental Issues by Perceived Certainty and Tangibility.” Environmental Education and Information 19 (1): 11–20.

- Lee, Jae-Young, and In-Ho Kim. 2002. “A New Measure in Environmental Education Research: Subjectively Responsible Environmental Behavior (SREB).” Korean Journal of Environmental Education 15 (2): 61–75. [in Korean]

- Lee, J. Y. 2000a. “A Cross-Cultural Investigation of College Students’ Environmental Decision-Making Behavior: Interactions among Cultural, Environmental, Decisional, and Personal Factors.” PhD diss., The Ohio State University.

- Lipshitz, R., and O. Strauss. 1997. “Coping with Uncertainty: A Naturalistic Decision-Making Analysis.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 69 (2): 149–163. doi:10.1006/obhd.1997.2679.

- Loroz, P. S. 2007. “The Interaction of Message Frames and Reference Points in Prosocial Persuasive Appeals.” Psychology and Marketing 24 (11): 1001–1023. doi:10.1002/mar.20193.

- Luke, T. W. 2001. “Education, Environment and Sustainability: What Are the Issues, Where to Intervene, What Must Be Done?” Educational Philosophy and Theory 33 (2): 187–202. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2001.tb00262.x.

- Lundholm, C. 2011. “Society’s Response to Environmental Challenges: Citizenship and the Role of Knowledge.” Factis Pax 5 (1): 80–96.

- Macdonald, E. K., and B. M. Sharp. 2000. “Brand Awareness Effects on Consumer Decision Making for a Common, Repeat Purchase Product: A Replication.” Journal of Business Research 48 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(98)00070-8.

- Mappin, M. J., and E. A. Johnson. 2005. “Changing Perspectives of Ecology and Education in Environmental Education.” In Environmental Education and Advocacy, edited by E. A. Johnson and M. J. Mappin, 1–28. Cambridge University Press.

- Meijer, I. S., M. P. Hekkert, and J. F. Koppenjan. 2007. “The Influence of Perceived Uncertainty on Entrepreneurial Action in Emerging Renewable Energy Technology; Biomass Gasification Projects in The Netherlands.” Energy Policy 35 (11): 5836–5854. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2007.07.009.

- Milliken, F. J. 1987. “Three Types of Perceived Uncertainty about the Environment: State, Effect, and Response Uncertainty.” Academy of Management Review 12 (1): 133–143. doi:10.5465/amr.1987.4306502.

- Ministry of Education. 2015. Ministry of Education Notice No. 2015-74 [Separate 19] High School Curriculum Curriculum. Sejong: Ministry of Education. [in Korean]

- Nisbet, M. C. 2009. “Communicating Climate Change: Why Frames Matter for Public Engagement.” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 51 (2): 12–23. doi:10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23.

- Ofgem. 2011. Smart Metering Implementation Programme: Response to Prospectus Consultation Supporting Document 3 of 5 e Design Requirements. UK: HM Gov.

- Ofori, G., and H. L. Kien. 2004. “Translating Singapore Architects’ Environmental Awareness into Decision Making.” Building Research & Information 32 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1080/09613210210132928.

- Phillips, B., V. R. Prybutok, and D. A. Peak. 2014. “Decision Confidence, Information Usefulness, and Information Seeking Intention in the Presence of Disconfirming Information.” Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 17: 001–025. doi:10.28945/1932.

- Pimentel, D. 2009. “Environmental and Economic Costs of the Application of Pesticides Primarily in the United States.” In Integrated Pest Management: Innovation-Development Process, edited by D. Pimentel, 89–111. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Pimentel, D., R. Zuniga, and D. Morrison. 2005. “Update on the Environmental and Economic Costs Associated with Alien-Invasive Species in the United States.” Ecological Economics 52 (3): 273–288. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.10.002.

- Rockström, J., W. Steffen, K. Noone, Å. Persson, F. S. Chapin, E. F. Lambin, T. M. Lenton, et al. 2009. “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity.” Nature 461 (7263): 472–475. doi:10.1038/461472a.

- Røpke, I. 2004. “The Early History of Modern Ecological Economics.” Ecological Economics 50 (3–4): 293–314. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.02.012.

- Russ, A., ed. 2015. Urban Environmental Education. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Civic Ecology Lab, NAAEE and EECapacity.

- Saylan, C., and D. Blumstein. 2011. The Failure of Environmental Education (And How We Can Fix It). Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Schultz, P. W., and L. Zelezny. 2003. “Reframing Environmental Messages to Be Congruent with American Values.” Human Ecology Review 10 (2): 126–136.

- Soper, D. S. 2017. “p-Value Calculator for a Student t-Test [Software].” http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc

- Spence, A., C. Leygue, B. Bedwell, and C. O’Malley. 2014. “Engaging with Energy Reduction: Does a Climate Change Frame Have the Potential for Achieving Broader Sustainable Behavior?” Journal of Environmental Psychology 38: 17–28. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.12.006.

- Steffen, W. 2011. “A Truly Complex and Diabolical Policy Problem.” In The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society, edited by John S. Dryzek, Richard B. Norgaard, and David Schlosberg, 21–37. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sternäng, L., and C. Lundholm. 2012. “Climate Change and Costs: Investigating Students’ Reasoning on Nature and Economic Development.” Environmental Education Research 18 (3): 417–436. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.630532.

- Turner, R. K. 1999. “The Place of Economic Values in Environmental Valuation.” In Valuing Environmental Preferences: Theory and Practice of the Contingent Valuation Method in the US, EU, and Developing Countries, edited by I. J. Bateman and K. G. Willis, 17–41. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1981. “The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice.” Science 211 (4481): 453–458. doi:10.1126/science.7455683.

- UNESCO. 1977. First Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education Final Report. Tbilisi, USSR, Paris: UNESCO.

- Uzzell, D. 1999. “Education for Environmental Action in the Community: New Roles and Relationships.” Cambridge Journal of Education 29 (3): 397–413. doi:10.1080/0305764990290309.

- Van de Velde, L., W. Verbeke, M. Popp, and G. Van Huylenbroeck. 2010. “The Importance of Message Framing for Providing Information about Sustainability and Environmental Aspects of Energy.” Energy Policy 38 (10): 5541–5549. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.04.053.

- Wi, A., and C. H. Chang. 2019. “Promoting Pro-Environmental Behaviour in a Community in Singapore–from Raising Awareness to Behavioural Change.” Environmental Education Research 25 (7): 1019–1037. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1528496.

- Xu, L., V. Prybutok, and C. Blankson. 2019. “An Environmental Awareness Purchasing Intention Model.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 119 (2)367–381. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1074662.

- Yamashita, L., K. Hayes, and C. J. Trexler, 2017. “How Pre-Service Teachers Navigate Trade-Offs of Food Systems across Time Scales: A Lens for Exploring Understandings of Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 23 (3): 365–397.