Abstract

This paper seeks to reclaim irony as more than a way of humorously pointing out that the times we live in are out of joint or coming to an end, instead emphasizing its potential as a productive force and method in both educational thinking and teaching practice. By interrogating the educative potential of irony as method and humorous experience in the Bildung-oriented Didaktik tradition, we argue that irony can reveal the tensions and dilemmas of didactic posturing in order to facilitate a productive decentring and self-alienating critique of our anthropocentric predicament in education. It can be difficult to tease out the inherent distance between educational content and its substance in times where educators are caught between crowded curricula and strict testing regimes, but this irony is rarely lost on either pupils or teachers. Irony, we argue, is more than a constant fissure in the efforts to streamline ideas about what constitutes the most efficient didactic approaches. Instead, it could be used as a method to make educative processes attentive to what didactic posturing might be missing and how self-alienation might be a premise of education as formation of the self.

Introduction

In this paper we explore how irony can be seen as a both necessary and constructive concept in environmental and sustainability education. Irony commonly refers to a use of words that are expressing something other than, and especially the opposite of, literal meaning. Moving beyond the semantic aspect, irony is also often perceived as humorous. In this paper, we use and refer to irony for the most part as one way to relate to the knowledge claims inherent in educational and didactic posturing. That is, we use irony, and appeal to irony, as a concept to tease out certain ontological and epistemological conditions of environmental education. What we hopefully are able to achieve here is to show how humor as an experience sensitizes us to how things are and what this might mean for knowledge claims and didactic posturing in environmental education. We primarily understand irony, then, as a method that de(con)structs the ontological concepts and appeals upon which the epistemic dimension of didactic posturing draws, either explicitly or implicitly (Heidegger Citation1967; Derrida Citation1978).Footnote1

We are inspired by a Socratic tradition of irony in philosophical discourse, where irony as method is brought into play in the examination and consequent dissolution of the knowledge claims of others (cf. Gooch Citation1987). Sarcasm, as a form of irony, targets such knowledge claims in order to demonstrate that one’s own position is superior or beyond critique. However, in line with Kierkegaard’s diagnosis, we see Socratic irony as an absolute negativity that establishes nothing (Kierkegaard Citation2013). That is to say, for us, irony relates to a collapse of knowledge and truth claims, where irony as method is deconstructive in the sense that it undermines the apparent claim of ontological access to ulterior motives, knowledge, and to the truth of didactic posturing. What we mean by didactic posturing is best captured in the colloquial English-language use of the term ‘didactic’ as an adjective qualifying an act as teaching that has an ulterior motive or as knowledge that is felt as deeply patronizing. This patronizing aspect of didactic posturing surfaces, for example, in the doom and gloom scenarios debated in environmental and sustainability education (Kelsey and Armstrong Citation2012), where irony as method can deconstruct the claim that we have access to the future, since such a claim operates on the epistemic foundation of the didactic posture.Footnote2

When undermining this claim of being able to access the future, irony as method, in our understanding, seeks to collapse these epistemic foundations of explicit or implicit truth or knowledge claims. However, in contrast to Kierkegaard (Citation2013), we see irony as partially productive and not as unravelling into an absolute negativity. As such, we believe irony is able to avoid lapsing into cynicism, which we understand as a form of destruction of epistemic foundations, primarily aimed at poking fun at the falsehood of understanding while at the same time claiming that embracing alternatives is futile or utopian. The educative potential of irony as method lies in its ability to amplify a tension between thought and feeling, or rather the feeling of thought (Morton Citation2010, 124f). The ironic resonance of humour as a feeling (experienced in the deconstruction of the epistemic foundation of thought) is an amorphous emotional resonance where the experience of humour can turn into the feeling of humorous seriousness once the destruction ‘hits home’ in the experience of negation or groundlessness of the experience of self and its existence. Yet, we do not see irony as the ultimate weapon of relativism (Rorty Citation1989), but as a promising method in educational thinking that helps us to move beyond, or rather deeper than, nihilism.

Following Nishitani’s (Citation1990, 7) analysis of European nihilism—which asserts that the ‘disclosure of nothingness at the deepest transcendent ground of history and the self makes a metaphysics of history from the standpoint of Existence possible”—we argue that irony as a method that deconstructs the ground of history and the human self can help education thought and educative practice relate to experiences that are not reducible to human history and the historicity of the self experiencing itself in the world. Accordingly, we see irony as an educative method that helps us engage with the effort in environmental and sustainability education research to move beyond anthropocentrism (Nakagawa and Payne Citation2019; Kopnina Citation2012; Affifi Citation2020a). Following Morton’s (Citation2010) reasoning, we see irony as the sense of coexistence and experience of having a relationship with other entities that we cannot fully ‘know’.

Acknowledging the diversity of historically embedded understandings of environmental and sustainability education (Gonzalez-Gaudiano and Buenfil-Burgos Citation2009), as well as the particular need to rethink the status of the subject, nature, and society within Western modernity (Le Grange Citation2012), we position our argumentation against the backdrop of the European tradition of curriculum and instruction theory and the praxis of Didaktik—a tradition within which we ourselves are enmeshed. This tradition can also be seen as having influenced environmental and sustainability education research. We aim to contribute to this contextually shaped strand of environmental and sustainability education research, as well as to introduce some of its key questions, for example concerning the status and educative substance of educational content, to a wider body of environmental and sustainability education research (Singer-Brodowski et al. Citation2019; Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010; Rauch Citation2000; Laessøe and Öhman Citation2010; Scheunpflug and Asbrand Citation2006; Seybold and Rieß Citation2006).

Furthermore, we see the tradition of Didaktik, at its core, as haunted by a tension between a primary focus on the individual’s development of self and its claim to simultaneous overall human development. In this paper, we explore this relation between the self as learner (as the key focus of the concept of Bildung as a process of self-formation) and the overarching educative project of human Bildung (formation) (Hopmann Citation2007; Masschelein and Ricken Citation2013)—as two processes of formation that are not reducible to one another –as a productive entry point for reconceiving the humanness of the learner as subject and its relation to the content of education.

When speaking of Didaktik, we refer to a Bildung-oriented Didaktik that engages with the philosophical and political project of German Enlightenment and translates it to the context of contemporary educational goals (Klafki Citation2011).Footnote3 The early considerations of Humboldt (Citation2010, 237), who saw Bildung as the process that makes the individual ‘reach beyond himself [sic] to the external object […] bringing the mass of objects closer to himself, impressing on his mind upon this matter, and creating more of a resemblance between the two’. Accordingly, it is this engagement with the world of external objects that puts in relation to another the diverse processes of individual Bildung into general/common Bildung (Allgemeinbildung), whereas in more recent Didaktik theory history replaces the integrating function of the world of object as the theory of the present epoch and can be seen as synthesising diverse individual Bildungs-processes in relation to such epochal key problems (Klafki Citation1994). It is this tension regarding the status of external objects and history as referents of a synthesizing function among diverse processes of Bildung in the tradition of Didaktik that we see as an opening for irony as method do engage with, where irony as method can undermine the didactic posture’s patronizing imposition of the idea of synthesis between the individual experience and that of humanity. In line with this reasoning and the Didaktik tradition’s focus on unique teaching situations, we engage with irony as method as an alternative to the ‘what works’ discourse in environmental and sustainability education discourse (cf. Monroe et al. Citation2019).

In this paper, we argue that irony is a productive educative method in the sense that the experience of humour establishes the possibility of alienation—both alienation from taken-for-granted knowledge claims and alienation that deconstructs the historicity of community that operates in the equalizing inclusion of what it means to be a learning human subject. Thus, irony as method has productive educational possibilities. On the one hand, it can deconstruct previously taken-for-granted epistemic foundations that operate within teaching practices or are seemingly at play in ambitions of education. On the other hand, irony can be also be utilized as a means of facilitating a strange experience of existence, or rather coexistence, that might break through the remaining projects of history in the absence of ground in nihilism.

By engaging with irony as method in environmental and sustainability education in line with a Didaktik tradition of focusing on content and the experience of that content, we also align ourselves with this special issue’s objective, which we see as to create a dialogue between environmental and sustainability education research and research on humour in education. As this paper focuses on providing examples of irony as method and exploring irony as method in a Didaktik-inspired approach to environmental and sustainability education, we will not engage directly with research on humour in education (Banas et al. Citation2011; Garner Citation2006; Gordon and Mayo Citation2014). However, we embrace such engagement with humour and see laughter not as a negative, exceptional reality of social life (Morreal Citation1983), but as something that sensitizes individuals to the strangeness and uncanniness of life. We see clear links to the groundbreaking work of Vlieghe, Simons and Masschelein (Citation2010) concerning the corporeal aspects of laughter in education, which can be seen as a complement to research with a more narrow focus on the cognitive aspects of humour in education and learning. As we will argue below, we see irony as involving a tension between bodily experienced feelings of humorous irony and accompanying thought.

In this paper, we present our arguments through examples of irony as method, and we explore and deconstruct the ‘didactic’ dimension of education—or rather instances of didactic posturing within education. We argue that this didactic dimension of educational thought and debate resembles the scenario involving the supercomputer Deep Thought in Douglas Adams’ (Citation1979) The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. After 7.5 million years of computation, Deep Thought arrives at the ‘Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, The Universe, and Everything’, which is (SPOILER ALERT!!!) ‘42’. A way of short-circuiting didactic processes would be to solely focus on the need to teach the answer ‘42’ to everyone, while suffering from the same issues as Deep Thought who lacks information about the initial question.

This example of irony as method illustrates how any didactic posture claiming to have access to ultimate knowledge or motive has potential for ironic engagement with its epistemological foundations. To give another example illustrating how irony can be utilized as method to engage with didactic posturing, picture a scenario where extra-terrestrial visitors arrive on earth following a nuclear apocalypse, with the last dateable artefact of human civilisation a half-burned PISA 2024 report summarizing progress towards teaching 21st century skills. The humorous feeling of irony in response to the didactic posturing of the PISA test relates to the possibility of a perspective that is still to come or that has already been, yet is neglected or implicitly excluded from the test’s epistemic foundation. The humorous feeling of irony seems to reverberate with a temporal and spatial residue that undermines the epistemic foundation of didactic posturing.

We see the humorous feeling of irony as related to an ‘outside’; that is, an external context or situation (spatial or temporal outside referring to temporal and spatial perspectives outside the inside of context or situation) that didactical posturing seeks to establish and which disrupts any attempt to determine a border or ‘inside’. We argue that this ‘outside’ is both a temporal and spatial surplus, which, as a quasi-outside of context or situation, undermines the epistemic foundation of didactic posturing that claims to be able to establish a border and an inside of the educational context or situation. Andreas Schleicher, director of the OECD Directorate of Education and Skills, might respond by ridiculing the case of extra-terrestrial visitors; however, we would argue that he, or we in general, might struggle to exclude the historical possibility (temporal residue) of nuclear annihilation. The potential of an almost has been as a form of open future seemingly avoided (e.g. the Cuban missile crisis) in this sense troubles the didactic posture that claims access to knowledge of what the future might hold. The possibility of a past that could have been different (temporal residue in the act of remembering) or a future that turns out differently (temporal residue of an open future) is, in our understanding, an illustration of the humorous feeling of irony in didactic posturing relating to the potential of an outside undermining the foundation of a posture that aims to establish and fixate the inside as situation or context.

The ambition of this paper is to apply the ironic method we have outlined to theoretically explore how the humorous feeling of irony can be amplified constructively to deconstruct didactic posturing in environmental and sustainability education. We turn here specifically to the Didaktik tradition to engage with how its inherent tension can be engaged with in order to use the humorous feeling of irony to attune to a temporal and spatial third perspective and to outline the possible implications for didactical ambitions and processes of environmental and sustainability education as informed by a Bildung perspective.

Irony in the Didaktik tradition

When we speak of interrogating the educational potential of irony as method, the paper positions itself, as previously mentioned, within the Continental European and Nordic tradition of Bildung-oriented Didaktik (e.g. Klafki Citation1985). Accordingly, our perspective focuses on the micro-level processes of teaching and students’ experiences when engaging with particular educational content. While the scope of this paper prevents us from exploring the details and nuances of how a Bildung-oriented Didaktik differs from Anglo-Saxon notions of curriculum and instruction, we will in the following emphasize some of the key differences to illustrate why questions relating to irony are at the forefront of this paper. In particular, we will highlight how Didaktik relates to a tension between individual and societal formation (Bildung meaning formation in German), outlining the key concepts of educative substance, educative significance and content of education.

As Hopmann (Citation2007) highlights, Didaktik, as a Continental approach to educational theory and reflexive practice that differs from the Anglo-Saxon focus on curriculum and instruction, must be understood as an educational tradition that emerged from at least two key historical formation processes. The first is the formation of schooling in the emergent state of Germany during the late 19th century when teachers had a significant amount of freedom in terms of teaching methods and lesson design in enacting the curriculum. In parallel, the development of didactical thought as a form of science of teaching in Germany, in contrast to the US, was not grounded primarily in educational psychology, but in a notion of Geisteswissenschaft (science of mind/spirit) that shares similarities with the humanities. Dilthey was the key figure in grounding Didaktik in this Geisteswissenschaft, where German Idealism, and especially the work of Hegel, was a source of inspiration (cf. Friesen Citation2020). The key implication is that instead of being based on abstract knowledge of the workings of a generalized mind or a learner as in curriculum and instruction theory, Didaktik is focused on the individuality and particularity of the phenomenology of lived experience (Erleben). Or, as Hopmann (Citation2007, 114) puts it, at the core of the Didaktik tradition is the notion of the pupil as ‘a natural learner and a born leader of his or her own idiosyncratic learning’. As Bildung (education as formation) primarily concerns the formation of the self, curricula and instructive interventions in the Bildung-oriented tradition must facilitate this process of self-formation. Hence, Hopmann (Citation2007) highlights how Didaktik involves an element of restraint by the teacher, as education is always primarily the unique processes of self-formation that are the core of Bildung. To restrain teaching is to provide space for the self to develop in accordance with its own unique nature, and hence teaching must not be instrumental or calculable based on abstract concepts of a generalized mind.

Yet, the act of teaching that is to foster Bildung is not completely individualized, but structured around the central concept of content of education (Menck Citation1986; Klafki Citation1985). Accordingly, the process of formation of the self is dependent on an engagement with something. This something, distinct from the self, is the content of education (Bildungsinhalt). It is also this engagement of the self with educational content that can be seen as aligning individual formation (Bildung) with the formation of humanity as a whole, as both self and humanity engage with certain key content, for example Klafki’s (Citation1994) epochal key problems. Accordingly, it is with regards to the content of education that there is a possibility of a partial alignment or synthesis of the process of Bildung at the micro and macro levels. Hence, the question of the content of education becomes central as teachers must ask themselves ‘what this object can and should signify for the student and how the student can experience this significance’ (Hopmann Citation2007, 116). The educative substance (Bildungsgehalt) of a particular content is therefore key; the didactic intervention is focused on enabling pupils to experience the generalizable educative substance of this content.

To explore the educative potential of irony as method, we discuss Didaktik’s grounding in the phenomenology of experience of the individual learner, as well as the focus on the content of education and its educative substance. We argue that irony as method is a way to engage with the feeling of coexistence with the content of education, where the humorous experience of irony reveals the difference between the experience of educative significance of this content and its educative substance. The experience of irony hereby highlights a tension or particularity of the epistemological foundation of didactic posturing that claims to encapsulate that substance. The phenomenologically experienced ‘patronizing’ aspect of someone else’s didactical posture highlights here the non-congruence between imposing a claim of educative substance and how it is experienced. The Bildung-oriented Didaktik tradition highlights a tension in the understanding of how the Bildung of the self aligns with the overall Bildung of humanity.

Deep Thought’s engagement with the answer to the ‘Ultimate Question of Life, The Universe, and Everything’ as potential content of environmental and sustainability education highlights a feeling of ironic tension between the potential to rationally derive an answer and the emotional experience of its significance for one’s self-formation. Educational content has both emotional and cognitive dimensions when engaged with from a first-person student perspective on learning. Potential dissonance between the two dimensions can be highlighted, for example when considering the personal significance of the ‘reasonable’ answer of ‘42’, the non-ironic examples in the lyrics of Alanis Morrisettes’s (Citation1996) ‘Ironic’, or the educative paradox of seeking greater understanding of climate change while simultaneously promoting climate anxiety (cf. Ojala Citation2016).

Hence, with our approach to irony as method, we hope to provide a foundation for understanding how the Didaktik tradition offers an entry point, allowing educational thought to grapple with the role of the content of education. The notion of Bildung at play in the Didaktik tradition highlights a tension between the didactically ascribed general educative significance of a given content and the personal experiences of a lack of significance. We use the concept of Bildungssignifikanz (educative significance) to highlight how any didactic gesture towards the educative substance of educational content is dependent on that content being experienced as personally significant. In addressing irony as the feeling of coexistence (Morton Citation2010, 125), we argue that irony as method can allow educational thinking to sensitize the learner towards coexistence, where that coexistence is felt when we are not able to exhaust the content of education in didactic posturing. In the following we will engage with a number of ironic interventions aimed at to illustrating how the feeling of irony relates to this tension between experienced educative significance and efforts to determine the educative substance of a content of education.

Irony and the temporal and spatial dimension of the substance of education

Irony as method enables exploration of another possible dissonance between the educative substance of content as ascribed through didactic posturing and personal experiences of that substance and its role in self-formation (Bildung). Such exploration requires engagement with the spatial and temporal aspects of the relationship between specific content of education and its educative substance. In the following, we engage with examples of irony as method in popular culture and cinematography to illustrate how spatial and temporal aspects can be used.

There is, for example, a history within theatre and cinematography of irony as method in the narrative portrayal on stage or screen through the spatial effect of an audience in the background who grasp the substance of what is happening or what is said while this substance is not apparent to the actors in the foreground. Think, for example, of the double audience as viewers watch the old man crossing the square and observing a car chase in the original Pink Panther movie (Edwards Citation1963) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nistdsACs3E). The humorous experience of irony is amplified by a tension arising from the spatial perspective (view of the square that the cars inevitably pass in their chase) that is offered to the audience as well as the old man, but withheld from the other characters in this scene. The possibility of engaging with this tension is provided by a dialectical relation between two interwoven yet opposing ambitions of the different characters (those trying to catch the thieves and those trying to get away). Irony as method is possible by actively engaging with the non-congruent yet interdependent positions that become apparent through the provision of a third spatial perspective on the two character-centred perspectives.

In a similar manner, instructional intervention that relies on irony as method might introduce the spatial dimension of a contrasting second or third perspective (i.e. a spatially different perspective) on the content of education that is able to undermine the stabilization of the substance of that content according to a first or second perspective. The learner’s humorous experience of irony in the contrasting tension between non-congruent perspectives on the content can be used to facilitate the possibility of reopening the question of educative substance, letting the learner ‘choose’ between perspectives on content and decide how to define its substance.

Similar to the spatial effect of irony as method used in cinematography to establish perspective, irony as method also can explore phenomenologically the temporal displacement of the substance of content. Such a temporal displacement through the experience of irony can help teaching reopen the relationship between a content of education and its substance. The temporal dimension of the non-congruence and tension between content and its substance is generally reduced to the past (cf. Bengtsson forthcoming); that is, an object of education is seen as ‘containing’ (see the meaning of ‘content’) or holding something in place that has already been unlocked by how the object has appeared through a previous manifestation. In simple terms, the educative substance of educational content is held in place by previous experiences of and engagement with this content by humans, including disciplinary study and everyday practice.

This is also true within the Didaktik tradition, where Klafki (Citation1985) as one of its most prominent thinkers appeals to notions of the historical reality of educational content as unlocked by universal categories. An appeal is often made to notions of ‘nature’ as a stable ontological background (nature as an expression of universal categories) or a spiritual (Geist) reference point (e.g. the transcendental mind or the non-human world/planetary consciousness of eco-pedagogy) when considering the stability of the educative substance. However, through irony as method, we can tease out how access to educative substance is temporally distorted or illuminate the tension that is at play when trying to reduce educative substance to a generalized past that is the referent of past stability.

Consider, for example, the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick Citation1968). The monolith can be seen as the archetypal ‘content of education’ as it is purely instructional in the sense of teaching something. Recall the opening scene, ‘the dawn of man [sic]’, where our hairy ancestors touch the monolith and gain the notion of tools and technology. It is purely instructional in the sense that touching it teaches, while at the same time introducing the idea of manipulating and unlocking reality as (hairy) subjects. Here, we see irony as a humorous experience as echoing a tension in the idea of the content having an educative substance that can be located in the past. The monolith does not teach our human ancestors something that it already was, but utilizes them to become (hu)man in order to create technology and ultimately AI. Hence, the temporal dimension of irony emerges in the idea that the monolith has a substance that is in the future. We might ask ourselves: ‘Whose historical reality is the monolith as educative content containing and unlocking?’

The temporal dimension of the irony of the idea of ascribing educative substance to historical reality can be teased out in the monolith’s ability in the long term to teach us how to construct HAL 9000, i.e. artificial intelligence. Accordingly, the educative substance of the monolith as content for proto-humanity is not in the opening scene (‘the dawn of man’), but in a future that was still to come, that is the future where HAL 9000 was constructed. The educative substance in the case of the monolith was not ‘ours’ (that of the hairy subjects appropriating reality though the use of tools) and did not contain something that we formed ourselves through Bildung as formation of humanity, but might be interpreted by looking into the future as a substance of AI realizing the emergence of itself through humans (hairy subjects as tools to create AI) in the past. This example illustrates how irony can be used as a method to undermine the reduction of educative substance to the past/present (how a content has appeared/appears), reopening the tension between content and substance to the process of formation (Bildung). Bildung as self-formation might thus be possible when the individually experienced feeling of ironic humour undermines the didactic posture of ascribing universally valid educative substance to a content of education.

Our exploration of irony in the context of the Didaktik tradition seeks to highlight that the phenomenology of the experience of irony is educative. The experience of irony when engaging with a content of education, we argue, shows intuitively how educative substance of that content appears to us. The humorous feeling of irony illustrates in this sense the feel of thinking educative substance. By becoming aware of how substance reveals itself in the experience of irony, we can utilize this insight to theorize access to this educative substance in education thought. In the face of irony, the previously mentioned patronizing aspect of didactical posturing, claiming to have access to the educative substance of a content of education, can be seen as amplifying a tension between implied access to educative substance in thought and the feeling of experience of that implication being off. That is not to suggest that there is no such thing as a discernible educative substance or that the person who experiences irony has access to some true educative substance. In the case of the former, we acknowledge the dangers of nihilism, where irony might be employed as a means to illuminate a form of pure negativity at the epistemic foundation of didactic posturing. In the case of the latter, a particular spatial or temporal perspective would be able to fully account for the educative substance of a content of education. As such, the didactic posturing would be able to literally account for the epistemic foundation of its claim, but such literalism might result in a universe devoid of humour.

Hence, we are not arguing that irony as an experience of humour can direct thinking to the right or wrong perspective on a content of education that would account for its substance. Instead, we argue that the humorous experience of irony points towards or gives us the feeling for a third perspective on the educative substance of a content of education. This perspective highlights and moves beyond a tension between contrasting, and hence dualistic, positions. In this sense, we see it as compatible with the core paradox or tension in the Bildung tradition; that is, a tension between personal formation and that of society or humanity. In the following, we will expand on what we mean when we say that irony is educative in the sense that it points beyond a tension between existing perspectives.

Irony and a third perspective

When discussing the educative significance of a third perspective, please note that we refer to ‘a’ rather than ‘the’ third perspective. A third perspective, as the emotional response of humour tells us, is not reducible to a single determinable neglected perspective of thought that had not previously been taken into consideration (e.g. the often implicit third and true perspective evoked when outlining three positions in a scholarly paper). Instead, it relates to the failure of perspective of thought to fully account for the educative substance of content.

To illustrate this point using spatial irony as method, the humorous experience of irony that is facilitated by amplifying a tension between foreground and background perspectives can be seen as highlighting that there is no such attainable position from either view nor the often-applied transcendental/meta-perspective to be attained through reason. Irony as method that engages with the potential of a third perspective hereby suggests that it is impossible to access a view that is not caught up in a foreground, and vice versa. The transcendental or meta-perspective from the background turns out to be ironically caught up in the foreground—a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, there was a species stuck to one planet thinking it ‘got’ the universe, life and everything.

We argue that the educative significance of the humorous experience of irony that is created through a tension between two perspectives (either temporal or spatial) lies in the experience of irony making the didactic point (as a deconstruction of perspective) that any attained ‘perspective’ does not capture or contain educative substance. That is, the humorous feeling of the experience of irony points towards, or rather resonates from, this evasive position as a third perspective and its educative significance. Irony, in the experience of educative significance, does not point to a specific alternative (the third perspective), but is self-referential in the sense that it resonates and dislocates a third perspective in the tension between two perspectives. What we mean by self-referential irony is that the truth claim of a statement can be seen and, by applying reason, acknowledged as ‘absolute’ truth. At the same time, however, this claim also give us a humorous feeling of being not ‘false’ but somewhat ‘off’ in the sense that its binary construction and underlying logical framework is not really up to the task of accounting for ‘perspective’.

As an example of a form of irony that is self-referential, consider the Internet meme that ‘Everything in the world is either a potato or not a potato’ ().

In logical terms, it is a valid statement and we might acknowledge its truth claim, yet, in its overt simplicity, the humorous experience of its ironic tension in dividing the world into two categories draws attention to what we have called a third perspective. The meme pinpoints the flimsiness of the epistemic foundation of the didactic posture as the humorous experience of irony when applying its knowledge claims resonates with the educative significance of a third perspective that is evasive and cannot be expressed using the binary construction of the world in terms of potato/not-potato.

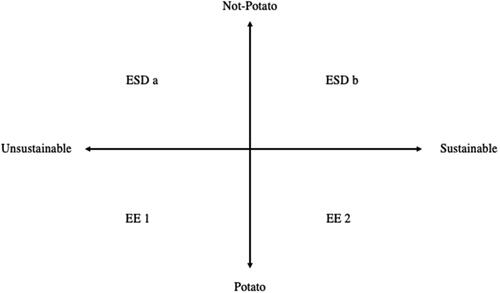

This binary construction of the world, in terms of its potatoness/non-potatoness, relates also to a projection of self onto that world. We will here use the saying of there being two classes of people in the world as cleverly suggested by the mysterious, yet positively inclined, Reviewer 3 of this paper. According to the saying attributed to Robert Benchley (https://quoteinvestigator.com/2014/02/07/two-classes/): ‘There are two kinds of people in the world: Those who divide everybody into two kinds of people, and those who don’t’. In a similar fashion to the potato meme, the classification of people into two classes highlights the irony at play in a self-referential projection of view of the self onto the world. Hence, with a nod to the seemingly never-ending schism between those people touting Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and those touting Environmental Education (EE), we might be tempted to use irony as method to position different educational approaches and normative positions according to such a twofold structure of things in the world, categorizing them according to their sustainability and their potatoness (see ).

Figure 2. Positioning education approaches according to their alignment with sustainability and potatoness.

Against this deep-rooted enjoyment of such two- and four-fold categorizations in environmental and sustainability education research (references intentionally omitted), their related normative ground and the didactic posture of ascribing educative significance of one in relation to a ‘dimension’ of the world (potatoness) as well as the entailing account for the ultimate question of environmental and sustainability education, we argue for the educative significance of evoking a third perspective by creating ironic tensions in educational as well as research settings. As we will argue below, the humorous experience of an epistemological foundation collapsing in the face of irony is educative in the sense that it attunes us to the experience of the educative substance of a third perspective.

Furthermore, we see irony as method as having an important potential for environmental and sustainability education research as it not only helps us to problematize the idea of the borders of perspectives, for example anthropocentric perspectives (Kopnina Citation2016), but can also be used to undermine the epistemic foundation of appeals that use binary logics such as nature/culture to establish such borders (e.g. Affifi Citation2020a; Russell Citation2005). We regard irony’s ability to attune us to a third perspective as educative—not as a means for overcom(b)ing anthropocentrism, but as a method that can help us to point out the anthropocentrism of perspectives attained by the human learner/researcher.Footnote4 It does so by showing how the notion of ascribing educative substance in the didactic gesture is rooted in a perspective defined by human access to spatiality and temporality.

We might here refer to the novella, ‘Story of Your Life’ by Ted Chiang (Citation2002) that later was transformed into the movie Arrival (Villeneuve Citation2016) to illustrate our point. After the arrival of alien spaceships on earth, commanded by a species referred to as ‘Heptapods’, humans engage with these Heptapods in order to establish a shared language of communication. As the story shows, human language is defined by causality and limited human access to the dimension of time, while Heptapod language is based on teleology since Heptapods are able to experience all events (past, present and future) simultaneously. The temporal dimension of irony surfaces in the case of the educative effort by humans to teach Heptapods human language, as they are already able to understand it. Irony in this case exposes the human inability to understand teleological language. Hence, this irony points towards the anthropocentrism of the didactic posture of trying to teach non-humans something about humans that they already know.

Accordingly, the humorous experience of irony does not grant access to a perspective beyond anthropocentrism (i.e. understanding teleological language as used by Heptapods), but reveals to us humans the anthropocentrism of the didactic intervention or gesture (i.e. we thought Heptapods did not understand us, but in fact, it is was us who did not understand them). We might here comment that the didactic posture claims to have access to educative substance of a content is posing as being able to have access to all events (even future ones as they would already be accessible to Heptapods), instead of inferences based on limited human access to the dimension of time and spatiality.

Another example where irony can be utilized as method to point out the educative substance in the third perspective involves teasing out the potential anthropocentrism of critiques of anthropocentrism in environmental and sustainability education research (Kopnina Citation2016; Weldemariam Citation2020; Rautio Citation2013; Spannring Citation2017; Lundmark Citation2007). For example, when arguing to speak for tigers large and small in a critique of anthropocentrism, we might ask ourselves with Kopnina (Citation2016, 147): ‘Why do we discriminate against every other species on earth, including future generations of big tigers and little tigers? How can this be morally justified’?

Tigers such as Hobbes from the comic Calvin and Hobbes (please click on the link to see the specific one we have in mind: https://www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes/1989/04/09) might already have the answer to these questions: ‘… the ends justify the means’ (Watterson Citation1989). Hobbes’ response in the cartoon illustrates a potential relapse into epistemological solipsism when answering Kopnina’s question because the question can be seen to turn back towards a human audience and not towards tigers and the moral systems of belief and justification they might hold. Thus, the ironic contrast we have facilitated between Kopnina’s critique of anthropocentrism, which questions the moral foundation for human discrimination against tigers, and Hobbes the tiger’s response highlights the potential anthropocentrism of critiques of anthropocentrism, i.e. a human audience that is to provide or challenge this moral foundation. Yet, at the same time, the anthropomorphized tiger Hobbes’ utilitarian answer ‘embodies’ that other species. The tension of the status of Hobbes, being both tiger and non-tiger, hints at a potentially significant perspective that might be hiding in the non-tiger/tiger contradiction.

Hence, the ironic experience of humour suggests that the didactic posture of pointing out the educative substance of, for example, little tigers or their neglect is neither wrong nor right. However, in the moment of experiencing the feeling of humour, the didactic gesture is undermined by a third perspective that subverts both alternatives as constitutive of thought and makes its significance immanent to thinking about the educative substance of the content. Hence, the educative substance of tigers could be ascribed to the content, but we argue that it can be seen as both in the content (i.e. educative substance in the tiger) and for the environmental educator (i.e. the educative substance of the tiger for the educator).

The ironic experience of humour points out the difference between what constitutes the educative substance for the environmental educator (the idealized and anthropomorphized tiger through thinking) and what it is in the content of education (a substance that is not equivalent to the educator’s conception in thought). As such, we argue that irony does not necessarily lead to nihilism even though it can potentially unravel the absolute negativity at the ground of an epistemological foundation. Instead, we see the experience of irony as revealing that there is something beyond absolute negativity as it would not be possible for the educator/learner to deconstruct the educative substance of the content without the primary experience of something having educative significance. Yet, thinking that something will automatically be the educative substance of that content for the learner/educator falls short.

The experience of non-congruence between the educative substance in the content and for the educator/learner is facilitated by the humorous experience of irony. The humorous experience of irony simply echoes the non-congruence between the experience of educative significance and the ascription of educative substance. Hence, while the educative substance in the content can be seen as elusive (given that thinking it might be proven work according to another temporal or spatial perspective and the experience thereof), the humorous experience of irony highlights that something might have educative substance and that it might have significance for us.

We argue here that the humorous experience of irony does not deconstruct that something and show a pure form of negativity (no-thing, not-potato) but requires the existence of something of educative significance. It is here that the fruitful tension between formation of self and humanity in the Bildung tradition can be seen resurfacing and we argue that individual humorous experiences of irony can foster the formation (Bildung) of humanity by reminding of its humanness. Below, we explore how irony can be seen as fostering humanness as a form of method that engages with the anthropocentrism of environmental and sustainability education.

Irony as educative contamination of the learner by the content

When returning to the discussion of anthropocentrism, we might argue that irony as method can provide entry points for engaging with humanness that is not strictly speaking anthropocentric. Drawing on the work of Le Grange (Citation2012) related to environmental and sustainability education and his discussion of ubuntu (humanness) and ukama (relatedness) in contemporary African educational thought, we might argue in the context of the Didaktik tradition that irony as a method has the potential to foster humanness. As Le Grange (Citation2012, 65) notes: ‘Ubuntu helps us to appreciate that to be human means to care for self, the other and nature—that the learner is inextricably bound up in relations with the other and the biophysical world.’ What the humorous experience of irony can be seen to highlight, as it emerges in the experience of incongruence between educative substance for the learner/educator and in content of education, is this humanness of which LeGrange speaks. It shatters solipsism (the reduction of educative substance in the content to the idealized educative substance for the learner/educator) and at the same time points out to learners/educators that they are themselves enmeshed within the content of education.

Connecting the discussion of humanness to the recent engagement with uncanny and dark aspects of environmental and sustainability education research (Lysgaard Andreasen Citation2018; Ojala Citation2016; Saari and Mullen Citation2020; Affifi Citation2020b), we see humanness as entangled with or contaminated by the other referred to by LeGrange. We argue that the dark uneasy side of the humorous experience of irony (uneasy or nervous laughter) highlights that the experience of relatedness to, or educative significance of, the content of education does not lead to the construction of one’s self or the teacher. Our experience that a content of education has significance for us is uncanny in the sense that we ourselves experience that we are entangled with something that we did not decide to be entangled with.

Accordingly, we see a third perspective, as highlighted by the humorous experience of irony, as providing an opening to rethink the ontological relation between learner, teacher and content in environmental and sustainability education as well as the Didaktik tradition. Thus, the humorous experience of irony when engaging with a content that is significant to the learner as self highlights the bound-up-ness of that self and content (the relatedness that Le Grange (Citation2012) speaks of). The strangeness or uneasiness of that experience of irony points out the quality of what is at stake for the conception of the learner’s self and the content’s identity.

Recalling the ironic dimension of the reduction of the world into binaries (e.g. that everything in the world is either a potato or a non-potato) highlights something about the ontological register that aims to encapsulate identity in binary logics. What we are referring to is the logics by which the self and its relation to the content is conceived (Bengtsson Citation2019). The uneasiness of the experience of irony highlights to the self how it is caught up with the content of education. Further, we argue that the strangeness of this experience relates to the inability of classical laws of identity in logic (i.e. the law of non-contradiction and the law of excluded middle) to account in thought for the substance of both learner and content of education. The strangeness of the humorous experience of irony attunes us to the sensation that educative substance refuses to conform to the laws of non-contradiction and excluded middle.

As suggested by weird fiction writer Jeff VanderMeer (Citation2015): ‘Fiction is the contamination of the writer by something that is foreign to the self, if lucky, and yet intimate to it’. We argue that education, or rather Bildung, is the process of attentive contamination of the learner ‘by something that is foreign to the self, if lucky, and yet intimate to it.’ The humorous experience of irony, in its uneasiness and strangeness, is in the Didaktik tradition able to demonstrate this contamination to the learner as self; that is, it shows human learners how they are contaminated by the substance in the content of education that does not allow itself to be kept at bay as an idealized substance for an uncontaminated learner. Accordingly, in our encounter with the educative significance of a substance in the content that we aimed to keep at bay as a substance for us, we become aware of our contamination.

Meanwhile, we see the strangeness of the humorous experience of irony as signalling that we do not have access through rational thought (i.e. thought relying on the classical laws of identity) to that educative substance in the content that contaminates us. By acknowledging this contamination of the learner by the content when regarding the strangeness of humorous experience of irony as educative, we are suggesting that environmental and sustainability educational thought and the Didaktik tradition should break with the logic of non-contradiction when constituting the identity of the learner as self as they (intentional plural to signify a singular) are both the self and not the self. Thus, we are proposing to environmental and sustainability education thought that there is a Kopnina/Tiger. The learner as they, or the Kopnina/Tiger, are not reducible to relationally (wink wink: danger of anthropocentrism) as asymmetric contaminations of the self by other non-selves (the substance in the content of education) is the premise for our process of self-formation (Bildung).

As a result, we propose a reconceptualization of the understanding of the role or position of the content of education in environmental and sustainability education as something that contaminates the leaner as self in its inextricable significance for the self. We propose that irony as method’s engagement with the content of education might be approached as facilitating a contamination where the learner becomes aware that they are both the self and not the self. Our amendment to an outlook on environmental and sustainability education that builds on the Didaktik tradition acknowledges that the educative substance of that content forms us as human learners (Bildung meaning formation in German), yet, it is also not-us. As we have sought to highlight in this paper, we see the humorous experience of irony as pointing to the ontological dimension of a third perspective, where educative substance might not even be apparent to the content of education. Accordingly, even a tiger or a potato might have something as akin to an existential crisis, experiencing that they are not what they thought they were.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have argued that irony as method in environmental and sustainability education should be seen as a central practice that can facilitate experiences of ironic tension between the essence in educational content and its relevance for the process of self-formation that aims to render it into an essence for the self. Through the facilitation of this experience of tension, a third position can be established where it is possible to de(con)struct epistemological foundations that can be seen as maintaining or reproducing borders and contexts, especially problematic ones that perpetuate a distance between human subjects in education and the objects, things and contents that are addressed.

We see irony as method as a way to reconceive of (environmental) education (Bildung) as something that can engage with the overcom(b)ing of anthropocentrism and relapses into it by reopening a third perspective. However, as we pointed out, irony as method has an uncanny and dark side. In the best case scenario, it facilitates an engagement with a unified humanness as a form of self-alienation—an experience that can lead to a sense of discomfort. When using irony as method, environmental and sustainability education might lead to a sense of loss of essence (‘once upon a time, I was a potato’) but we argue that this should not render education a ‘safe zone of schooling’, a form of comfort food of self-idealization.

To reiterate, Bildung, as the equivalent to the idea of education, refers to self-formation, where formation requires an abandonment of self rather than a development that maintains, builds on or celebrates the self as it was. We highlighted this with the notion of contamination by the content of education, where the formation of the humanness of the self can be seen as requiring a contamination of the self by that it was not. There would be no overcom(b)ing of anthropocentrism without the tiger in its uncanniness and strangeness. With regard to the use of irony in environmental education as a tool we would here suggest refraining from sarcasm, that is to undermine knowledge claims in order to demonstrate that onés own position is superior or beyond critique. Further, irony as requiring an abandonment requires a certain form of openness or willingness to engage with what is at stake for oneself. Our initial recommendation for experimentation is to engage with irony that is close to what one holds dear as the humorous aspect can easily get lost when turned to a group or social beliefs that one and others might not identify with. When turned against such beliefs and positions irony might easily lead to resentment given that others might not be as willing to engage with the formation of the self.

As this paper’s argument for considering irony as method in environmental and sustainability education is targeted at a research audience, we think that a key question for future research is the possible applications of irony as method in educational settings. Moreover, given our limited abilities as armchair academics to actually embody a humorous experience in this paper, we see a need for cooperation between comedians as educators, educators as comedians, and researchers to explore how irony as method could be developed and under what conditions it operates in order to maximize the tension between thought and feeling.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 By ontological and ontology we refer to how things are. Ontology, as an area of philosophy of knowledge and metaphysics, relates to two central questions concerning the being and existence of things. The first relates to “what” is (e.g. that some things are and others are not). We do not engage with this question as we see it as a trap because answering this question from a specific perspective (e.g. human) would not exhaust what still might remain hidden in its being. The second, relates to “how” things are. In this paper we argue that a somewhat hidden, or twilight status, of how things are relates to irony that becomes both a possibility and necessity when making truth/knowledge claims.

2 By epistemic foundation we refer to the basis or axiomatic ground of making truth claims.

Epistemology as an area of philosophy relates to knowledge and the premises of knowledge and knowledge claims. An epistemic foundation of, for example, an argument entails in this sense also an ontological assumption. Accordingly, a truth claim or a claim of knowledge about something relates to assumptions about how things are and, depending on the claim, also claims of what is.

3 Please note that “Didaktik” refers in this paper to a historically specific approach to curriculum and instruction theory and praxis, whereas we use “didactic” to highlight the patronizing aspect of didactic posturing, whether within or outside education, which claims to have access to absolute knowledge or truth.

4 We introduce the terminology of “overcom(b)ing anthropocentrism” to highlight the potential or danger of relapse into anthropocentrism in efforts to overcome it. Like middle-aged men (perhaps including the authors of this paper) seeking to salvage their damaged pride and idealized self-image by adjusting their hairstyle, over-com(b)ing anthropocentrism can be seen as a committed effort to alter the perception of reality, like turning a head half-empty of hair into a head half-full of it.

References

- Adams, Douglas. 1979. The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy. London: Pan Books.

- Affifi, Ramsey. 2020a. “Anthropocentrism’s Fluid Binary.” Environmental Education Research 26 (9–10): 1435–1452. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1707484.

- Affifi, Ramsey. 2020b. “Beauty in the Darkness: Aesthetic Education in the Ecological Crisis.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 54 (4): 1126–1138 doi:10.1111/1467-9752.12475.

- Banas, John A., Norah Dunbar, Dariela Rodriguez, and Shr-Jie Liu. 2011. “A Review of Humor in Educational Settings: Four Decades of Research.” Communication Education 60 (1): 115–144. doi:10.1080/03634523.2010.496867.

- Bengtsson, Stefan L. 2019. “A Pedagogy of Vulnerability.” In Dark Pedagogy: Education, Horror and the Anthropocene, edited by Jonas Lysgaard Andreasen, Stefan L. Bengtsson, and Martin Hauberg-Lund Laugesen, 143–158. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bengtsson, Stefan L. forthcoming. "Didaktiken efter idealismen: Undervisningsobjektets återkomst i antropocen.

- Chiang, Ted. 2002. Stories of Your Life and Others. New York: Vintage Books.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1978. Writing and Difference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Edwards, Blake. 1963. The Pink Panther [Movie]. Los Angeles: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc.

- Friesen, Norm. 2020. “Education as a Geisteswissenschaft:’ an Introduction to Human Science Pedagogy.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 52 (3): 307–316. doi:10.1080/00220272.2019.1705917.

- Garner, R. L. 2006. “Humor in Pedagogy: How Ha-Ha Can Lead to Aha!.” College Teaching 54 (1): 177–180. doi:10.3200/CTCH.54.1.177-180.

- Gonzalez-Gaudiano, E, and R. Buenfil-Burgos. 2009. “The Impossible Identity of Environmental Education.” In Fields of Green. Restorying Culture, Environment, and Education, 97–108. Creskil NJ: Hampton Press.

- Gooch, P. W. 1987. “Socratic Irony and Aristotle’s ‘Eiron’: Some Puzzles.” Phoenix 41 (2): 95–104. doi:10.2307/1088738.

- Gordon, Mordechai, and Cris Mayo. 2014. “Special Issue on Humor, Laughter, and Philosophy of Education: Introduction.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 46 (2): 115–119. doi:10.1080/00131857.2012.728091.

- Grange, Lesley Le. 2012. “Ubuntu, Ukama and the Healing of Nature.” Self and Society.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 44 (2): 56–67. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2011.00795.x.

- Heidegger, Martin. 1967. Sein Und Zeit. 1967th ed. Tübingen: Max Niewmeyer Verlag.

- Hopmann, Stefan T. 2007. “Restrained Teaching: The Common Core of Didaktik.” European Educational Research Journal 6 (2): 109–124. doi:10.2304/eerj.2007.6.2.109.

- Humboldt, Willhelm von. 2010. “Theorie Der Bildung Des Menschen.” In Wilhelm Von Humboldt. Werke in Fünf Bänden. Band I., edited by A. Filtner and K. Giel, 234–240. . Washington DC: Wbg.

- Kelsey, Elin, and Carly Armstrong. 2012. “Finding Hope in a World of Environmental Catastrophe.” In Learning for Sustainability in Times of Accelerating Change, edited by Arjen E.J. Wals and Peter Blaze Corcoran, 187–200. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Kierkegaard, Søren. 2013. “Kierkegaard’s Writings.” Vol. II. The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates/Notes of Schelling’s Berlin Lectures. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Klafki, Wolfgang. 1985. Neue Studien Zur Bildungstheorie Und Didaktik: Zeitgemässe Allgemeinbildung Und Kritisch-Konstruktive Didaktik. Weinheim: Beltz Verlag.

- Klafki, Wolfgang. 1994. “Grundzüge Eines Neuen Allgemeinbildungskonzeptes. Im Zentrum: Epochaltypische Schlüsselprobleme.” In Neue Studien Zur Bildungstheorie Und Didaktik, edited by Wolfgang Klafki, 43–82. Weinheim: Beltz Verlag.

- Klafki, Wolfgang. 2011. “Die Bildungstheoretische Didaktik Im Rahmen Kritisch-Konstruktiver Erziehungswissenschaft.” In Didaktische Theorien, edited by Wolfgang Klafki, Herbert Gudjons and Rainer Winkel, 13–34, Hamburg: Bergmann & Helbig.

- Kopnina, Helen. 2012. “Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): the Turn Away from ‘Environment’ in Environmental Education?” Environmental Education Research 18 (5): 699–717. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.658028.

- Kopnina, Helen. 2016. “Of Big Hegemonies and Little Tigers: Ecocentrism and Environmental Justice.” The Journal of Environmental Education 47 (2): 139–150. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1048502.

- Kubrick, Stanley. 1968. A Space Odyssey. Los Angeles: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc.

- Laessøe, Jeppe., and Johan Öhman. 2010. “Learning as Democratic Action and Communication: Framing Danish and Swedish Environmental and Sustainability Education.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1080/13504620903504008.

- Lundmark, Carina. 2007. “The New Ecological Paradigm Revisited: Anchoring the NEP Scale in Environmental Ethics.” Environmental Education Research 13 (3): 329–347. doi:10.1080/13504620701430448.

- Lysgaard Andreasen, Jonas. 2018. Learning from Bad Practice in Environmental and Sustainability Education. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Masschelein, Jan., and Norbert Ricken. 2013. “Do We (Still) Need the Concept of Bildung?” 1857. doi:10.1111/1469-5812.00015.

- Menck, Peter. 1986. “Unterrichtsinhalt Oder Ein Versuch Über Die Konstruktion Der Wirklichkeit Im Unterricht.” Frankfurt am Main & New York. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Mogensen, Finn, and Karsten Schnack. 2010. “The Action Competence Approach and the ‘New’ Discourses of Education for Sustainable Development, Competence and Quality Criteria.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 59–74. doi:10.1080/13504620903504032.

- Monroe, Martha C., Richard R. Plate, Annie Oxarart, Alison Bowers, and Willandia A. Chaves. 2019. “Identifying Effective Climate Change Education Strategies: A Systematic Review of the Research.” Environmental Education Research 25 (6): 791–812. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842.

- Morreal, John. 1983. Taking Laughter Seriously. Albany: University of New York Press.

- Morrisette, Alanis. 1996. Ironic on “Jagged Little Pill.” [Album]. Los Angeles: Warner Bros.

- Morton, Timothy. 2010. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nakagawa, Yoshifumi., and Phillip G. Payne. 2019. “Postcritical Knowledge Ecology in the Anthropocene.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 51 (6): 559–571. doi:10.1080/00131857.2018.1485565.

- Nishitani, Keiji. 1990. The Self-Overcoming of Nihilism. New York: SUNY Press.

- Ojala, Maria. 2016. “Facing Anxiety in Climate Change Education: From Therapeutic Practice to Hopeful Transgressive Learning.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 21: 41–56. https://unco.idm.oclc.org/login?url= http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eue&AN=124824549&site=ehost-live.

- Rauch, Franz. 2000. “Schools: A Place of Ecological Learning.” Environmental Education Research 6 (3): 245–258. doi:10.1080/713664679.

- Rautio, Pauliina. 2013. “Being Nature: Interspecies Articulation as a Species-Specific Practice of Relating to Environment.” Environmental Education Research 19 (4): 445–457. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.700698.

- Rorty, Richard. 1989. “Contingency.” Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Russell, Constance L. 2005. “Whoever Does Not Write is Written’: The Role of ‘Nature’ in Post‐Post Approaches to Environmental Education Research.” Environmental Education Research 11 (4): 433–443. doi:10.1080/13504620500169569.

- Saari, Antti, and John Mullen. 2020. “Dark Places: Environmental Education Research in a World of Hyperobjects.” Environmental Education Research 26 (9-10): 1466–1478. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1522618.

- Scheunpflug, Annette., and Barbara. Asbrand. 2006. “Global Education and Education for Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 12 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1080/13504620500526446.

- Seybold, Hansjörg, and Werner Rieß. 2006. “Research in Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development in Germany: The State of the Art.” Environmental Education Research 12 (1): 47–63. doi:10.1080/13504620500526487.

- Singer-Brodowski, Mandy, Antje Brock, Nadine Etzkorn, and Insa Otte. 2019. “Monitoring of Education for Sustainable Development in Germany—Insights from Early Childhood Education, School and Higher Education.” Environmental Education Research 25 (4): 416–492. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1440380.

- Spannring, Reingard. 2017. “Animals in Environmental Education Research.” Environmental Education Research 23 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1188058.

- VanderMeer, Jeff. 2015. “AREA X: The Fictive Imagination in the Dusk of the Anthropocene.” Sonic Arts Festival - The Geologic Imagination. 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJ6aUBLL8z4.

- Villeneuve, Dennis. 2016. Arrival. Los Angeles: Lava Bear Films.

- Vlieghe, Joris, Maarten Simons, and Jan Masschelein. 2010. “The Educational Meaning of Communal Laughter: On the Experience of Corporeal Democracy.” Educational Theory 60 (6): 719–734. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5446.2010.00386.x.

- Watterson, Bill. 1989. “Calvin and Hobbes April 09.” https://www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes/1989/04/09.

- Weldemariam, Kassahun. 2020. “Reconfiguring Environmental Sustainability in Early Childhood Education: A Post-Anthropocentric Approach.” Environmental Education Research 26 (12): 1789–1789. doi:10.1080/13504622.2020.1854690.