Abstract

Unsustainable palm oil production is having a devastating impact on biodiversity in producing countries in Southeast Asia. Certification schemes for sustainable palm oil have the potential to reduce these impacts. The ubiquity of palm oil in processed foods found in supermarkets is a challenge that requires intervention at the policy level and with consumers through increasing public knowledge of the problem and awareness of sustainable alternatives. Zoos are increasingly demonstrating their role in increasing awareness of multifaceted conservation issues across a range of audiences. This paper describes the evaluation of a repeat-engagement outreach programme on palm oil delivered to 7–11 year old children in UK schools by zoo educators. We conducted a mixed-method study using before-after control-treatment surveys to examine the relationship between programme participation and participants’ knowledge of palm oil, sustainability, and awareness of sustainable alternatives. The analysis indicated improvements in participants’ understanding of palm oil as a conservation issue, and knowledge of how and where to identify sustainable palm oil in consumer products. The analysis also indicated a smaller improvement in participants’ understanding of sustainability. We discuss these findings in the context of zoo-led conservation education, and its potential role in Target-16 of the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.

Introduction

In 2022, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity met to ratify the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), outlining a new set of targets for the protection of global biodiversity (CBD Convention on Biological Diversity Citation2022). In the earlier Aichi Biodiversity Targets (CBD Citation2018) no mention was made of the challenges posed by unsustainable consumer choices. Although the GBF post-2020 targets are yet to be ratified, at the time of writing this paper, the following wording for Target 16 is included:

Ensure that people are encouraged and enabled to make sustainable consumption choices including by… improving education and access to relevant and accurate information and alternatives…

– Target 16 (abridged) Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. (Convention on Biological Diversity Citation2022)

Palm oil is valued for its versatility: possessing a distinct lack of flavour; existing in both liquid and solid form; and with a long shelf life relative to other vegetable oils (Dauvergne Citation2018). While these factors enable its use in products as varied as margarine, chocolate and shampoo, the primary advantage palm oil holds over other vegetable oils, is yield, with Oil Palms (Elaeis guineensis) suppling 35% of the world’s demand for vegetable oil from only 10% of the land allocated to oil crops (Meijaard et al. Citation2018). Such high yields result in lower cost for buyers and higher income-per-hectare for producers (Ayompe, Schaafsma, and Egoh Citation2021). These factors have contributed to, on average, an 8% annual growth rate in raw palm oil production since 1974 (Carter et al. Citation2007). The negative impact of the palm oil industry on biodiversity in producing countries in South East Asia is well-documented (Meijaard et al. Citation2020). The conversion of natural forest to plantation is reducing species richness and changing ecosystem community composition (Savilaakso et al. Citation2014). In Indonesia and Malaysia many animal species affected are currently listed as either Vulnerable, Endangered or Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List (IUCN Citation2022; Meijaard et al. Citation2018), most notably orangutans and tigers (Foster et al. Citation2011; Maddox Citation2007). With the global human population officially reaching 8 billion in 2022, demand for edible oils continues to rise, and an additional 35 million tonnes is expected to be required annually by 2050 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2022). As the most widely traded vegetable oil globally (Ayompe, Schaafsma, and Egoh Citation2021), the demand for palm oil is only going to increase over the coming decades, putting greater pressure on biodiversity in producing countries (Naidu and Moorthy Citation2021).

Seeking to increase sustainability in palm oil production while protecting biodiversity and livelihoods in producing countries, the non-governmental Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) promotes the adoption of sustainable practices within the industry (RSPO Citation2020). The RSPO developed a voluntary certification-scheme whereby all stakeholders within a supply chain must meet the social and environmental standards set for certification, and through recognisable product labelling, enable consumers to choose traceable products that meet these standards. Since its establishment in 2004, there has been increased demand for RSPO-certification, leading to the establishment of alternative certification schemes by producing countries and other NGOs (Abdul Majid et al. Citation2021). There remains some debate around the efficacy of such schemes due to the difficulty in monitoring the opaque palm oil industry, where complex land ownership and leasing arrangements are common, and long supply chains make it difficult to trace the exact origin of the product (Lang Citation2015; Morgans et al. Citation2018). Despite the ongoing debate, many countries and businesses support the RSPO certification scheme as the best option available for consumers wishing to reduce their environmental impact through changes to consumption choices (Sundaraja, Hine, and Lykins Citation2020; Wilcove and Koh Citation2010).

In 2012, Chester Zoo, UK, began a campaign to increase availability of SPO in the UK, and to improve both public awareness of, and demand for RSPO certified products. The campaign sought to influence policy at multiple levels by engaging with different stakeholder groups. This included working with policymakers in the UK and EU to garner governmental support for deforestation free commodities; working with UK manufacturers and suppliers, to ensure supply chains are RSPO compliant; and at a local level, working with businesses in the retail and hospitality industries to encourage the switch to sustainable sources of palm oil in stocked products. Alongside these efforts, the campaign sought to improve awareness of SPO amongst the public through education interventions on the zoo site, and amongst children through engaging local schools in the Sustainable Palm Oil (SPO) workshops. The SPO workshops are intended as a part of a continuum of experiences needed to help the next generation adapt and respond to the challenges associated with biodiversity, while they also aim to increase awareness of the sustainable consumer choices available now to UK children and their parents or guardians. Many products containing palm oil such as chocolate, cookies and breakfast cereals are marketed to and enjoyed by children making them an important consumer demographic to consider (Mba, Dumont, and Ngadi Citation2015).

In recent years, zoos and aquariums (zoos) have increasingly shared evidence of their expertise in improving public awareness of conservation issues (Kleespies et al. Citation2022; Mellish et al. Citation2019; Schilbert and Scheersoi Citation2023; Spooner et al. Citation2021; Thomas Citation2020). Previous zoo-led palm oil campaigns have demonstrated educational impact through a range of delivery methods, such as Melbourne Zoo’s ‘Don’t Palm Us Off’ campaign that utilised a range of on- and off-site communication tools to deliver long-term improvements in knowledge and behavioural intention around purchasing SPO (Pearson et al. Citation2014). Evaluation of an in-zoo campaign that used interpretation and interactive games to promote SPO in the UK reported improvements in knowledge and purchasing intentions; however, they found that engagement with a zoo ranger significantly improved learning yet only one quarter of visitors surveyed actually engaged with a ranger (Major and Smith Citation2023). Although focussed on a different conservation topic, Moss and Pavitt (Citation2019) demonstrated a similar effect where evidence of visitors’ learning from a walk-through exhibit reduced in the absence of engagement with a zoo ranger or knowledgeable volunteer. In a research review of factors influencing a range of learning outcomes of zoo visits, Godinez and Fernandez (Citation2019) found that repeat zoo visitation is one of the most significant determinants of conservation knowledge. As palm oil is a complex and multifaceted topic, it is possible that the repeat-engagement outreach format could encourage consolidation of learning through repetition and provide participants the opportunity to reinforce learning more than a one-off zoo visit (Borrello, Annunziata, and Vecchio Citation2019; Clayton et al. Citation2017; Joshi and Rahman Citation2015; Miller et al. Citation2013; Sundaraja, Hine, and Lykins Citation2021; Yalowitz Citation2004). This format can also potentially avoid the reported limitations of ‘unguided’ in-zoo learning through repeated, focussed engagement with zoo educators (Jensen Citation2014). Additionally, by delivering this programme in schools, it enables zoos to engage and educate children who might otherwise be limited by the economic or physical barriers to visiting the zoo itself.

Moss et al. (Citation2017) showed that repeat-engagement conservation education delivered by zoo educators in a school-classroom setting could significantly improve children’s knowledge of rainforests and associated threats. While a similar study found the addition of a zoo visit alongside an in-school programme on native UK wildlife did not significantly improve participants learning around pro-nature behaviour when compared with children who only received the in-school component (Counsell et al. Citation2020). Both of these studies used pre and post-programme mixed-methods surveys to demonstrate the learning potential offered by repeat-engagement in-school education delivered by zoo-educators.

This study evaluates the efficacy of Chester Zoo’s SPO workshops delivered in UK schools to children aged 7 – 11 years. We surveyed participants on two occasions, prior to the first workshop and following the final workshop, to measure changes in knowledge around palm oil and awareness of SPO. We included control groups in the study in an attempt to isolate the effect of programme participation within a climate of increased palm oil messaging and higher levels of UK media coverage for palm oil and its associated issues (Butler and Sweney Citation2018; Iceland Foods Citation2018; Smith Citation2020; Van der Tak Citation2018). The inclusion of control groups is intended to avoid the lack of counterfactual identified as a limiting factor in other similar studies (Balmford et al. Citation2007; Counsell et al. Citation2020; Kuhar et al. Citation2010; Pearson et al. Citation2014). The four knowledge-based variables measured were: understanding of palm oil and associated conservation issues; ability to identify household products containing palm oil; conceptual understanding of sustainability; and ability to describe personal pro-nature behaviours.

Materials and methods

Chester zoo’s sustainable palm oil workshops

In this study, we sought to measure the efficacy of a series of zoo-led, in-school conservation education workshops on the topic of sustainable palm oil (SPO) by comparing pre-programme and post-programme responses to a series of knowledge-based survey questions. The focal programme consisted of four classroom-based workshops, each lasting approximately 50 min, and a daylong visit to the Chester Zoo site, which included a further taught workshop. Chester Zoo educators delivered the in-school workshops with class teachers present in the classroom. Content of workshops and trip (full details in appendix):

Introduction to palm oil: what it is; palm oil versus other oil crops; where and how it is used; the conservation issues associated with palm oil production.

Introduction to Indonesia: diversity of wildlife in Indonesia.

Sustainable palm oil: the concept of sustainability; how to identify sustainable palm oil on product labels; how consumer behaviour in the UK directly connects to a reduction in deforestation and fragmentation in Indonesia.

What have we learned: quiz; ‘sustainable palm oil pledge’.

Zoo trip: tour of the orang-utan exhibit ‘Realm of the Red Ape’; in-zoo education sessions that reinforce knowledge of conservation issues associated with palm oil production.

Participants

Chester Zoo offered the free SPO workshops to primary schools that met its project school criteria: schools where pupils might face economic barriers to accessing the zoo and fell within an approximate one-hour drive radius of the Chester Zoo site in the north west of England. We invited all schools receiving the SPO workshops to participate in this research. We recruited our control group from schools registered to receive the programme in the spring/summer term of 2019, allowing for approximately concurrent data collection alongside the programme recipients in the autumn/winter term of 2018.

Survey tool

We developed a mixed-method, repeated-measures survey to evaluate four knowledge-based variables: A) understanding of palm oil and associated conservation issues; B) ability to describe personal pro-nature behaviours; C) ability to identify palm oil containing household products; and D) conceptual understanding of sustainability. We designed the survey items to capture both direction and magnitude of change between survey stages. Using ordinal scales, we scored responses to items A, B and D for correctness and detail in a four-stage method (see Appendix). The ordinal scale used to assign a response score to items A and B ranged from zero (lowest quality response) to four (highest quality response), while the scale used to assign a score to responses to item D ranged from zero (lowest quality response) to three (highest quality response). Responses received a score of zero for one of three reasons: factually incorrect responses; responses including any variation on the phrase ‘I do not know’; and responses that lacked validity, including nonsensical or irrelevant statements. We discounted data from single item analyses where participants did not attempt to respond to that item. The full details of our scoring criteria are included in the appendix. We recorded responses to item C as two count variables: number of correctly identified household items; and number of incorrectly identified household items. To ascertain whether a response was correct or incorrect, we started with the list of example household items introduced in Workshop 1 and used inductive coding to expand the lists of correct and incorrect items, verifying each additional item via online searches of product ingredients. In addition to the quantitative analyses, we conducted deductive thematic coding on a subset (20%) of responses to item B. Finally, we asked participants to provide their academic school year [in lieu of age], gender, and whether or not they had previously visited Chester Zoo.

Procedure

Using the online tool Survey Monkey, we collected data in two stages between October 2018 and May 2019. To account for the staggered delivery of the SPO programme during this period, we collected data consistently relative to programme delivery: the first stage took place during the school-week prior to Workshop 1 to provide a baseline measure for each outcome variable; the second stage took place during the school-week following the participants’ completion of the workshops and zoo visit. Participants accessed the Survey Monkey on in-school computers and class teachers supervised them throughout completion of the survey. We instructed class teachers to provide necessary levels of technical assistance to ensure all participants could access and complete the survey, but we requested that they not provide any direct answers or prompts to the survey items. Control groups completed the pre-programme survey and post-programme survey at concurrent intervals to the programme recipients in the autumn of 2018.

Data analysis

We assessed the ordinal dependent variables: knowledge of palm oil and its associated conservation issues; understanding of the term ‘sustainability’; and knowledge of personal pro-nature actions, using Cumulative Link Mixed Models (CLMMs) with Brant test of parallel regression assumption. We used Nagelkerke pseudo R2 to estimate model fit. We assessed knowledge of household items containing palm oil using Generalised Linear Mixed Effects Models (GLMMs) fit with quasi-Poisson distribution to account of over-dispersion, using Bootstrap confidence intervals. For three of our four dependent variables, we produced a full model including survey stage (pre- and post-programme) and experimental condition (control vs recipient) as fixed effects with interaction terms, the fourth model included the same fixed effects structure, with no interaction term. We included school as a random effect to account for the potential confounding effects of differences between schools such as ratings and location. To assess the potential impact of participant demographics, we initially constructed either CLMMs or GLMMs for each dependent variable including gender; academic year group [in lieu of age]; and whether or not the participant had previously visited Chester Zoo, as fixed effects. We dropped non-significant effects from the model, and confirmed model selection using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC); as a result, we omitted these demographic variables from the final models.

We conducted data analysis in R Studio 2022.07.2 Build 576 (R Core Team Citation2022), using the ordinal (Christensen Citation2019) and lme4 (Bates et al. Citation2014) packages.

Ethics

We sought gatekeeper consent from class teachers for all participants. Participation was voluntary with personal consent obtained prior to the completion of both survey stages. Participants in the control groups received the full SPO programme following completion of the research. All survey responses were anonymous. Chester Zoo’s independent ethical review committee reviewed and approved this research.

Results

The pre-programme dataset contained 2364 students from 21 schools; however, following a steep drop-off in post-programme survey completion (35%), we omitted all surveys from schools where <50% of post-programme surveys were completed, leaving data from 14 schools; 12 of which received the programme, the remaining two were control schools. Our final data set contained 2099 surveys; 1254 pre-programme and 845 post-programme ().

Table 1. Number of respondents at both survey stages in each academic year.

Understanding of palm oil and associated conservation issues

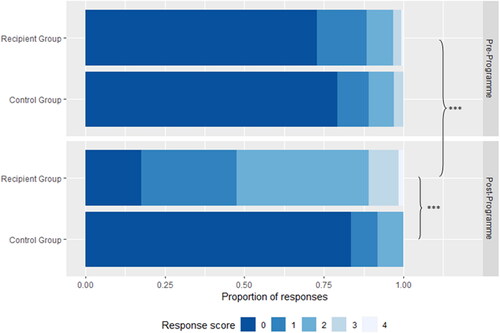

At the pre-programme stage, 13.5% of respondents in the recipient group did not attempt to answer this item, this number dropped to 1.7% post-programme. Of those who did respond in the pre-programme survey, 76.6% received a score of zero, a combined 21.4% received a score of one to two, with the remaining 2.1% of responses receiving a score of three or four. At the post-programme stage, 18.0% of responses received a score of zero, 71.9% scored either a one or a two, and 10.2% of responses received a score of three to four. When investigating knowledge of palm oil and its associated conservation issues, the final-model included experimental condition and survey stage as fixed effects, school was included as a random effect. This model (χ2 = 545.56, df = 3, p < .001) was a significantly better fit than the null model. The interaction of fixed effects showed significant influence on response score, while there was no difference between experimental conditions in the pre-programme responses, recipients of the programme were more likely to provide a higher scoring answer in the post-programme survey by a factor 2.76 (95% CI: 2.17 − 3.35, p < .001) versus those in the control group (). The model achieved pseudo-R2 estimate of .28, meaning that the model explained 28% of the variance in respondents’ knowledge of palm oil and its associated conservation issues.

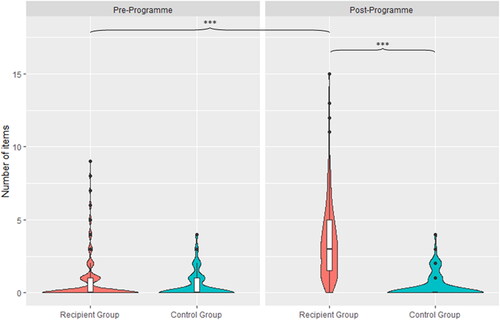

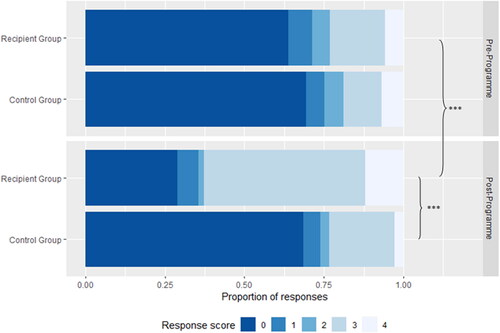

Ability to describe personal pro-nature behaviours

This item received the lowest response rate of our four variables, with only 50.1% of respondents in the recipient group attempting to answer this survey item at the pre-programme stage, while in the post-programme, 64.2% attempted to respond. Of those who did respond in the pre-programme survey, 62.8% received a score of zero; a combined 15.0% received a score of one to two; and a combined 22.2% received a score of three or four. In the post-programme stage, the number of responses scoring a zero dropped to 28.9%, a combined 9.0% scored either a one or a two, while 62.0% received a score of three or four. Using the same effects structure as the previous model, we analysed the relative impact of programme participation on knowledge of actions to help protect nature. This model was a significantly better fit (χ2 = 154.13, df = 3, p < .001) than the null model. Once again, we found no difference between the experimental conditions in the pre-programme surveys and significant influence of interaction of fixed effects on post-programme responses, with those in the recipient group significantly more likely to provide a higher scoring answer by a factor 1.76 (95% CI: 1.08 − 2.44, p < .001) versus those in the control group (). A pseudo-R2 of 0.14 showed that this model explained 14% of the variance in responses.

Figure 2. Respondents’ ability to describe and describe personal pro-nature behaviours presented as stacked bar charts, indicating the relative proportion of each response score aggregated at levels of survey stage and experimental condition. Significance is based on CLMMs, see text (***p < 0.001).

As well as scoring the responses for use in quantitative analysis, we also conducted deductive thematic analysis of pro-nature behaviours identified by a subset (20%) of the recipient group. We found that at the pre-programme stage, 86.4% of responses described general pro-nature behaviours, for example, ‘Clean up the environment’, ‘Give money to charity’, while 3.8% described a behaviour relating to palm oil, for example, ‘don’t use palm oil’, ‘cut the palm oil from the trees’. Only one respondent directly stated ‘buy sustainable palm oil’ as a pro-nature behaviour at the pre-programme stage. The remaining respondents stated either that they did not know (0.8%) or provided an invalid response (9.1%). At the post-programme stage, 55.7% of responses made direct reference to programme-specific learning outcomes, for example, ‘buy things with sustainable palm oil’, ‘be sustainable and read the label’, ‘join the RSPO’; while a further 9.3% made general references to palm oil, for example ‘Eat less palm oil’. Of the remaining responses, 17.5% described general pro-nature behaviours, 15.5% were invalid answers, and 2.1% stated that they did not know of a behaviour.

Ability to identify palm oil containing household products

At the pre-programme stage, 78.5% of the respondents in the recipient group attempted to answer this survey item, this increased to 97.8% post-programme. Amongst the workshop recipients who responded at the pre-programme stage, 71.5% were unable to identify a single item containing palm oil, and 20.4% could name a maximum of two correct items. While 5.5% could name between three and four items, only 2.6% were able to identify more than five items. At the post-programme stage, the number of respondents unable to identify any items reduced to 4.3%. The post-programme data also revealed 35.3% of recipients were able to name up to two correct items, 34.0% were able to name between three and four, and 26.4% were able to identify over five items. To model the influence of survey stage and experimental condition on knowledge of which household items contain palm oil, we continued with the same fixed and random effects structure as the previous analyses. This model (χ2 = 421.09, df = 3, p < .001) was a significantly better fit than the null model. As with our two previous dependent variables, finding no difference between the experimental conditions in the pre-programme surveys, we identified significant differences between the conditions post-programme. Those receiving the programme were more likely to identify a greater number of household items containing palm oil in the post-programme survey by a factor 2.067 (95% CI: 1.51 − 2.60, p < .001) verses those in the control group (). This model achieved a marginal R2 of .367, and a conditional R2 of .451. When we modelled the number of incorrect items listed, we did not find any difference between either surveys stages or experimental conditions. Removing outliers did not significantly alter either result.

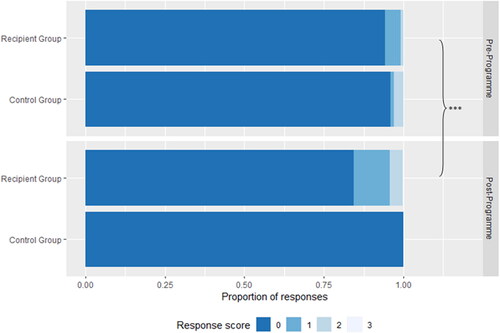

Conceptual understanding of sustainability

At the pre-programme stage, 82.6% of those in the recipient group attempted to respond to this survey item, this number increased to 98.0% at the post-programme stage. Of those who responded at the pre-programme stage, 94.1% received a score of zero, 4.5% received a score of one, and a combined 1.1% of responses scored a two or a three. At the post-programme stage, the number receiving a zero dropped to 86.4%, an additional 10.7% received the score one, and the remaining 2.9% received a score of either two or three. When modelling respondents’ understanding of the term ‘sustainability’, there was no difference between experimental conditions in the pre-programme responses. Our model included survey stage and experimental condition as fixed effects, with school included as a random effect. This model was a significantly better fit than the null model (χ2 = 17.012, df = 2, p < .001). Responses provided in the post-programme surveys were more likely to be higher scoring, versus those provided in the pre-programme survey, by a factor 0.82 (95% CI: 0.43 − 1.23, p < .001) (). Only 2% of the variation in responses was explained by the model (pseudo-R2 = 0.02). We could not model the interaction between survey stage and experimental condition due to singularity in the control group responses at the post-programme stage.

Discussion

The need to support the next generation in acquiring the necessary knowledge and motivation to meet the challenges facing biodiversity is recognised at the highest levels of national and international policy (CBD Citation2022; UK Department for Education 2022). This study sought to measure the efficacy of a conservation education outreach programme delivered by zoo educators on the critical conservation issue of palm oil by comparing pre-programme and post-programme responses to a series of knowledge-based survey questions. Our results showed an improvement in four key learning outcomes, and those participating in the workshops demonstrated higher post-programme levels of learning versus our control groups in three variables.

Understanding of palm oil and associated conservation issues, and ability to identify palm oil containing household products

In a study measuring knowledge of palm oil following engagement with rangers, interpretation and interactives, Major and Smith (Citation2023) identified the need to capture visitors’ prior knowledge to better understand the impact of their in-zoo campaign, our before-after control-treatment design provides this opportunity. The two variables that captured the greatest degree of post-programme knowledge change were those measuring ability to recall facts about palm oil and issues surrounding its use, and the ability to identify household products likely to contain palm oil. In both instances, baseline knowledge was very low, with over 75% of our respondents scoring zero in their response to the former item, and 71% scoring zero in the later. Low levels of pre-programme knowledge were expected from our young demographic, and align with the broader trends of palm oil awareness within the public (Borrello, Annunziata, and Vecchio Citation2019; Sundaraja, Hine, and Lykins Citation2021). These low baselines provided a high ceiling for knowledge acquisition, which was reflected in the improved responses to both items at the post-programme stage. This learning is consistent with the results of two other survey-based evaluations that reported similar proportions of UK primary school children demonstrating improved knowledge of complex conservation topics following repeat-engagement outreach programmes (Counsell et al. Citation2020; Moss et al. Citation2017). It is difficult to meaningfully compare the effectiveness of our approach with that of other zoo-led palm oil campaigns since most of these are aimed at the public and zoo visitors rather than primary aged children in schools (Herrera Citation2020; Kelly Citation2018; Major and Smith Citation2023; Pearson et al. Citation2014). The evaluation of these campaigns also focuses primarily on self-reported behavioural intentions and proxy or direct measures of behaviour that are not directly comparable to our knowledge and awareness measures. Rather than attempt such comparison, we consider the relative merit of the repeat-engagement outreach approach when compared with that of an educator-guided zoo visit, where a lower percentage (41%) of children demonstrated evidence of learning than we found in these two knowledge-based variables ( and ) (Jensen Citation2014). When conducted alongside other types of conservation education in school curriculums or in free choice learning environments, such as zoos or museums, these findings suggest that our approach can potentially help to equip the next generation with accurate and relevant conservation knowledge (Ballantyne and Packer Citation2005; Falk, Dierking, and Adams Citation2006; Heimlich and Falk Citation2009).

Ability to describe personal pro-nature behaviours

We found respondents’ pre-programme awareness of pro-nature behaviours to be very low: only half of the respondents attempted to describe a behaviour. Of those who did respond, over 60% received a pre-programme score of zero. Content analysis on a subset of pre-programme data revealed that awareness of behaviours related to palm oil was, expectedly, even lower, with a single respondent specifying ‘buying sustainable palm oil’ as a possible action, and an additional 3.8% making general mentions of palm oil. Both quantitative and qualitative analyses revealed marked difference in recipients’ post-programme awareness of pro-nature behaviours, and content analysis revealed a 61.2% increase in the number of responses relating to palm oil such as ‘buying SPO’ or ‘checking food labels’. While these findings are positive, we recognise the limitation that as consumers our 7 – 11 year old demographic are likely to have reduced autonomy around purchasing SPO when compared with adults and young adults. However, as a large number of products containing palm oil are marketed to children, there is the opportunity to influence the consumer choices of their caretakers (Mba, Dumont, and Ngadi Citation2015). There is some evidence to support the idea of children as agents for change in areas such as sustainable development, urban design and disaster risk reduction (Malone Citation2013; Mitchell, Tanner, and Haynes Citation2009; Percy-Smith and Burns Citation2013), although we could not find any empirical research exploring this effect in relation to sustainable consumer choices. We will seek to address this evidence gap in a follow up study. The evidence of low baseline awareness of pro-nature behaviours reported here highlights the need to improve awareness of sustainable choices identified in the GBF Target 16 (CBD Citation2022). The evidence of low levels of awareness of any other pro-nature behaviours is another concerning result, yet the post-programme learning reported here suggests there may be an important role for zoos in supporting the education sector in delivering its sustainability strategy (UK Department for Education 2022).

While a significant majority of our respondents did gain awareness of pro-nature behaviours, we did encounter some limitations with this survey item. Our analysis showed that there were fewer zero-scoring responses at the post-programme stage, yet content analysis of these zero-scoring responses revealed that a higher percentage of these respondents said, ‘I don’t know’ or provided an invalid, or nonsense response rather than attempting to describe a pro-nature behaviour. Overall, 7.7% of those who completed the four workshops, plus the zoo trip, were either less able or less motivated to describe a pro-nature behaviour at the post-programme stage. To maintain anonymity, we did not pair data at the level of the individual, and were unable to track the learning journey of a single respondent in our dataset; this prevented us from investigating this phenomenon any further within the current study. We will seek to explore this further in future research.

Conceptual understanding of sustainability

When measuring conceptual understanding of sustainability, 100% of responses provided by the control group at the post-programme stage received a score of zero, preventing any statistical comparison with the treatment group due to singularity. In the treatment group, pre-programme response rate was high, yet understanding was very low with over 94% of responses scoring zero, while evidence of understanding was only marginally higher at the post-programme stage. This result is not surprising given the age of our respondents and the relatively short time available to teach this complex topic. The concept of sustainability does not feature fully in the UK national curriculum until KS3 (11 – 14 years) so it is likely that the third workshop of the SPO programme is the first time many of our respondents will have encountered this concept (UK Department for Education 2022). Two studies suggested primary school children benefit from approaching sustainability themes through ‘softer’ areas, encouraging greater connection with nature rather than the more complex or controversial issues, such as palm oil (Hunt and Cara Citation2015; Pointon Citation2014). There is also evidence that some teachers feel less comfortable or able to teach concepts such as sustainably to primary school children (Green and Somerville Citation2015; Mundy and Manion Citation2008; Robinson and Sebba Citation2010; Summers et al. Citation2003). Rather than approaching this topic as a measurable learning outcome, evaluation of future zoo-led education with primary schools might consider the introduction of sustainability as a ‘building block’ of concepts and language that will support and inform children as they mature into young adults who are better able to understand the challenges facing biodiversity.

UK education sector and global biodiversity targets

Zoos exist within a sphere of influence that encompasses the local to the global (Spooner et al. Citation2023). Membership with organisation such as the British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums (BIAZA) and the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA), means that zoos can share lessons learned from the evaluation of education interventions such as this one, and collaborate with local, regional or global partners. WAZA Nature Connect is one example of this ‘scaled up’ approach, where 30 zoos across five continents delivered a campaign to connect individuals with nature (WAZA Citation2023). We recognise that the repeat-engagement outreach approach presented here will only be possible to replicate where resources allow, but we have demonstrated how this approach can potentially deliver measurable learning towards the sustainability goals in the UK education sector. Additionally, this opportunity for sharing and collaboration within national and international zoo networks means a repeat-engagement outreach approach could be scaled up to national, regional or global levels to make measurable contribution to GBF Target 16.

In conclusion, this research demonstrates the potential role for zoo educators to increase children’s access to relevant and accurate information away from zoo-sites, allowing for repeated and more in-depth engagement with a complex, multifaceted conservation topic while increasing access to a wider socioeconomic bracket than would be possible from zoo-site visits alone. Further work is needed to better understand the potential role of this younger demographic in influencing the sustainable consumer choices of their caretakers, and the small effect size of our sustainability variable suggests that future evaluation might expand beyond measuring knowledge to capture evidence of other change. Finally, our survey tool and use of control groups provides a simple and replicable method with a counterfactual for educators at zoos, aquariums, museums, and heritage or science centres, seeking to measure the effectiveness of interventions while controlling for the potential impact of outside messaging.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Charlotte Smith, Anya Moon and Chester Zoo’s Safari Rangers, who designed and delivered the SPO programme that participants of this study were recipients of, and for their help in facilitating data collection. We would also like to thank all the participants and the teachers at participating schools. We are grateful to Lucy Settle and Kimberley Russell for contributions during coding of responses. Finally, we would like to thank Dr Andrew Moss for contributions to protocol and survey design.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Funding

All research conducted using Chester Zoo core funding.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gregory Counsell

Gregory Counsell is a conservation scientist working within the science directorate at Chester Zoo, UK. His research focusses on human dimensions of wildlife conservation and intervention evaluation.

Gemma Edney

Gemma Edney was the social science intern at Chester Zoo at the time of this research and currently an undergraduate student at the University of York, UK.

Sean Dick

Sean Dick is the Learning Operations Manager at Chester Zoo, UK.

References

- Abdul Majid, N., Z. Ramli, S. Md Sum, and A. H. Awang. 2021. “Sustainable Palm Oil Certification Scheme Frameworks and Impacts: A Systematic Literature Review.” Sustainability 13 (6): 3263. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063263

- Ayompe, L. M., M. Schaafsma, and B. N. Egoh. 2021. “Towards Sustainable Palm Oil Production: The Positive and Negative Impacts on Ecosystem Services and Human Wellbeing.” Journal of Cleaner Production 278: 123914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123914

- Ballantyne, R., and J. Packer. 2005. “Promoting Environmentally Sustainable Attitudes and Behaviour through Free-Choice Learning Experiences: What is the State of the Game?” Environmental Education Research 11 (3): 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620500081145

- Balmford, A., N. Leader-Williams, G. M. Mace, A. Manica, O. Walter, C. West, and A. Zimmermann. 2007. “Message Received? Quantifying the Impact of Informal Conservation Education on Adults Visiting UK Zoos.” In Catalysts for Conservation: A Direction for Zoos in the 21st Century, London, UK, 19–20 February, 2004. 120–136.

- Bates, D., M. Mächler, B. Bolker, and S. Walker. 2014. “Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4.” arXiv:1406.5823v1. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1406.5823

- Borrello, M., A. Annunziata, and R. Vecchio. 2019. “Sustainability of Palm Oil: Drivers of Consumers’ Preferences.” Sustainability 11 (18): 4818. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184818

- Butler, S., and M. Sweney. 2018. Iceland’s Christmas TV advert rejected for being political. The Guardian. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/nov/09/iceland-christmas-tv-ad-banned-political-greenpeace-orangutan

- Carter, C., W. Finley, J. Fry, D. Jackson, and L. Willis. 2007. “Palm Oil Markets and Future Supply.” European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 109 (4): 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.200600256

- Christensen, R. H. B. 2019. Ordinal—Regression Models for Ordinal Data. R Package Version 2019.12-10. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal

- Clayton, S., A. C. Prévot, L. Germain, and M. Saint-Jalme. 2017. “Public Support for Biodiversity after a Zoo Visit: Environmental Concern, Conservation Knowledge, and Self-Efficacy.” Curator: The Museum Journal 60 (1): 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12188

- Convention on Biological Diversity. 2018. Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/

- Convention on Biological Diversity. 2022. Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. CBD/WG2020/5/L.2. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/409e/19ae/369752b245f05e88f760aeb3/wg2020-05-l-02-en.pdf

- Counsell, G., A. Moon, C. Littlehales, H. Brooks, E. Bridges, and A. Moss. 2020. “Evaluating an in-School Zoo Education Programme: An Analysis of Attitudes and Learning: Evaluation of Zoo Education.” Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research 8 (2): 99–106.

- Dauvergne, P. 2018. “The Global Politics of the Business of “Sustainable” Palm Oil.” Global Environmental Politics 18 (2): 34–52. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00455

- Falk, J. H., L. D. Dierking, and M. Adams. 2006. “Living in a Learning Society: Museums and Free-Choice Learning.” A Companion to Museum Studies 1: 323–339.

- Foster, William A., Jake L. Snaddon, Edgar C. Turner, Tom M. Fayle, Timothy D. Cockerill, M. D. Farnon Ellwood, Gavin R. Broad, et al. 2011. “Establishing the Evidence Base for Maintaining Biodiversity and Ecosystem Function in the Oil Palm Landscapes of South East Asia.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 366 (1582): 3277–3291. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0041

- Godinez, A. M., and E. J. Fernandez. 2019. “What is the Zoo Experience? How Zoos Impact a Visitor’s Behaviors, Perceptions, and Conservation Efforts.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1746. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01746

- Green, M., and M. Somerville. 2015. “Sustainability Education: Researching Practice in Primary Schools.” Environmental Education Research 21 (6): 832–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.923382

- Heimlich, J. E., and J. H. Falk. 2009. “Free-Choice Learning and the Environment.” In Free Choice Learning and the Environment, edited by J. H. Falk, J. E. Heimlich, and S. Foutz, 11–22. Lanham, MD: Altamira.

- Herrera, E. 2020. “The Influence of Messages on Behavioural Intentions and Attitudes towards Palm Oil Production.” Doctoral diss., Deakin University.

- Hunt, F., and O. Cara. 2015. “Global Learning in England: Baseline Analysis of the Global Learning Programme Whole School Audit 2013–14.”

- Iceland Foods. 2018. Iceland’s Banned TV Christmas Advert… Say hello to Rang-tan [Video]. YouTube. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://youtube.com/watch?v=JdpspllWI2o

- IUCN. 2022. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2022-1. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://www.iucnredlist.org

- Jensen, E. 2014. “Evaluating Children’s Conservation Biology Learning at the Zoo.” Conservation Biology : The Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology 28 (4): 1004–1011. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12263

- Joshi, Y., and Z. Rahman. 2015. “Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions.” International Strategic Management Review 3 (1-2): 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ism.2015.04.001

- Kelly, A. 2018. “Inspiring Pro-Conservation Behavior through Innovations in Zoo Exhibit and Campaign Design.” Doctoral diss.

- Kleespies, M. W., V. Feucht, M. Becker, and P. W. Dierkes. 2022. “Environmental Education in Zoos—Exploring the Impact of Guided Zoo Tours on Connection to Nature and Attitudes towards Species Conservation.” Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens 3 (1): 56–68. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg3010005

- Kuhar, C. W., T. L. Bettinger, K. Lehnhardt, O. Tracy, and D. Cox. 2010. “Evaluating for Long-Term Impact of an Environmental Education Program at the Kalinzu Forest Reserve, Uganda.” American Journal of Primatology 72 (5): 407–413. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20726

- Landis, J. R., and G. G. Koch. 1977. “The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data.” Biometrics 33 (1): 159. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20726

- Lang, C. 2015. “Who Watches the Watchmen? RSPO’s Greenwashing and Fraudulent Reports Exposed.” Redd-monitor.org. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://redd-monitor.org/2015/11/17/who-watches-the-watchmen-rspos-greenwashing-and-fraudulent-reports/

- Maddox, T. 2007. The Conservation of Tigers and Other Wildlife in Oil Palm Plantations: Jambi Province, Sumatra, Indonesia. Zoological Society of London.

- Major, K., and D. Smith. 2023. “Measuring the Effectiveness of Using Rangers to Deliver a Behavior Change Campaign on Sustainable Palm Oil in a UK Zoo.” Zoo Biology 42 (1): 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21697

- Malone, K. 2013. “The Future Lies in Our Hands”: Children as Researchers and Environmental Change Agents in Designing a Child-Friendly Neighbourhood.” Local Environment 18 (3): 372–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.719020

- Mba, O. I., M. J. Dumont, and M. Ngadi. 2015. “Palm Oil: Processing, Characterization and Utilization in the Food Industry–a Review.” Food Bioscience 10: 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2015.01.003

- Meijaard, E., et al. (eds.). 2018. Oil Palm and Biodiversity. A Situation Analysis by the IUCN Oil Palm Task Force. Switzerland: IUCN Oil Palm Task Force Gland.

- Meijaard, Erik, Thomas M. Brooks, Kimberly M. Carlson, Eleanor M. Slade, John Garcia-Ulloa, David L. A. Gaveau, Janice Ser Huay Lee, et al. 2020. “The Environmental Impacts of Palm Oil in Context.” Nature Plants 6 (12): 1418–1426. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-020-00813-w

- Mellish, S., J. C. Ryan, E. L. Pearson, and M. R. Tuckey. 2019. “Research Methods and Reporting Practices in Zoo and Aquarium Conservation-Education Evaluation.” Conservation Biology : The Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology 33 (1): 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13177

- Miller, L. J., V. Zeigler-Hill, J. Mellen, J. Koeppel, T. Greer, and S. Kuczaj. 2013. “Dolphin Shows and Interaction Programs: Benefits for Conservation Education?” Zoo Biology 32 (1): 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21016

- Mitchell, T., T. Tanner, and K. Haynes. 2009. “Children as Agents of Change for Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from El Salvador and the Philippines.” Children in a Changing Climate Research Working Paper no. 1. Institute of Development Studies: Brighton.

- Morgans, C. L., E. Meijaard, T. Santika, E. Law, S. Budiharta, M. Ancrenaz, and K. A. Wilson. 2018. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Palm Oil Certification in Delivering Multiple Sustainability Objectives.” Environmental Research Letters 13 (6): 064032. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aac6f4

- Moss, A. G., C. Littlehales, A. Moon, C. Smith, and C. Sainsbury. 2017. “Measuring the Impact of an in-School Zoo Education Programme.” Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research 5 (1): 33–37.

- Moss, A. G., and B. Pavitt. 2019. “Assessing the Effect of Zoo Exhibit Design on Visitor Engagement and Attitudes towards Conservation.” Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research 7 (4): 186–194.

- Mundy, K., and C. Manion. 2008. “Global Education in Canadian Elementary Schools: An Exploratory Study.” Canadian Journal of Education 31 (4): 941–974.

- Naidu, L., and R. Moorthy. 2021. “A Review of Key Sustainability Issues in Malaysian Palm Oil Industry.” Sustainability 13 (19): 10839. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910839

- Pearson, E. L., R. Lowry, J. Dorrian, and C. A. Litchfield. 2014. “Evaluating the Conservation Impact of an Innovative Zoo-Based Educational Campaign:’Don’t Palm Us Off’for Orang-Utan Conservation.” Zoo Biology 33 (3): 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21120

- Percy-Smith, B., and D. Burns. 2013. “Exploring the Role of Children and Young People as Agents of Change in Sustainable Community Development.” Local Environment 18 (3): 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.729565

- Pointon, P. 2014. “The City Snuffs out Nature’: Young People’s Conceptions of and Relationship with Nature.” Environmental Education Research 20 (6): 776–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.833595

- R Core Team. 2022. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: https://www.R-project.org/

- Robinson, C. and Sebba, J. 2010. Evaluation of UNICEF UK’s Rights respecting Schools Award. UK: UNICEF.

- RSPO. 2020. RSPO Supply Chain Certification Standard. RSPO-STD-T05-001. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://rspo.org/wpcontent/uploads/RSPO_Supply_Chain_Certification_Standard_2020-English.pdf

- Savilaakso, Sini, Claude Garcia, John Garcia-Ulloa, Jaboury Ghazoul, Martha Groom, Manuel R. Guariguata, Yves Laumonier, et al. 2014. “Systematic Review of Effects on Biodiversity from Oil Palm Production.” Environmental Evidence 3 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-2382-3-4

- Schilbert, J., and A. Scheersoi. 2023. “Learning Outcomes Measured in Zoo and Aquaria Conservation Education.” Conservation Biology 37 (1): e13891. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13891

- Smith, K. 2020. Iceland’s Banned Palm Oil Ad was the Most ‘Effective’ Commercial of 2018. Live Kindly. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://www.livekindly.com/icelands-banned-palm-oil-ad-was-the-most-effective-commercial-of-2018/

- Spooner, S. L., E. A. Jensen, L. Tracey, and A. R. Marshall. 2021. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Live Animal Shows at Delivering Information to Zoo Audiences.” International Journal of Science Education, Part B 11 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2020.1851424

- Spooner, S. L., S. L. Walker, S. Dowell, and A. Moss. 2023. “The Value of Zoos for Species and Society: The Need for a New Model.” Biological Conservation 279: 109925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.109925

- Summers, M., G. Corney, and A. Childs. 2003. “Teaching Sustainable Development in Primary Schools: An Empirical Study of Issues for Teachers.” Environmental Education Research 9 (3): 327–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620303458

- Sundaraja, C. S., D. W. Hine, and A. D. Lykins. 2021. “Palm Oil: Understanding Barriers to Sustainable Consumption.” PloS One 16 (8): e0254897. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254897

- Sundaraja, C. S., D. W. Hine, and A. Lykins. 2020. “Confronting the Palm Oil Crisis: Identifying Behaviours for Targeted Interventions.” Environmental Science & Policy 103: 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.08.004

- Thomas, S. 2020. Social Change for Conservation: The World Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Education Strategy. Barcelona, Spain: WAZA Executive Office. 89. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://www.waza.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/10.06_WZACES_spreads_20mbFINAL.pdf.

- United Kingdom, Department for Education. 2022. Sustainability and Climate Change: A Strategy for the Education and Children’s Services Systems. Policy paper. Accessed 16 January 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sustainability-and-climate-change-strategy/sustainability-and-climate-change-a-strategy-for-the-education-and-childrens-services-systems

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2022. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. UN DESA/POP/2022/TR/NO. 3. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/World-Population-Prospects-2022

- Van der Tak, C. 2018. Timeline Greenpeace Palm Oil Campaign 2007 – 2018. Greenpeace. Accessed 5 January 2023. https://www.greenpeace.org/nl/natuur/11405/timeline-greenpeace-palm-oil-campaign-2007-2018/

- Wilcove, D. S., and L. P. Koh. 2010. “Addressing the Threats to Biodiversity from Oil-Palm Agriculture.” Biodiversity and Conservation 19 (4): 999–1007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9760-x

- World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. 2023. WAZA Nature Connect Programme. Accessed 25 March 2023. https://www.waza.org/priorities/community-conservation/waza-nature-connect-programme/

- Yalowitz, S. S. 2004. “Evaluating Visitor Conservation Research at the Monterey Bay Aquarium.” Curator: The Museum Journal 47 (3): 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2004.tb00126.x

Appendix

Details of SPO workshop content

Timing: Each workshop was 50 min

Number of sessions: Four ‘in-school’, classroom-based workshops, with an additional zoo trip and in-zoo workshop.

Order of sessions:

Workshop 1: Introduction to palm oil, what is it, have you eaten it, define sustainable, play top trump oil game to show palm oil is most efficient oil, introduce problems with palm oil and RSPO logo and shopping list

Workshop 2: Introduce Indonesia and Malaysia, diversity of wildlife in Indonesia, what work is Chester Zoo doing in Indonesia

Workshop 3: Sustainable palm oil and tote bag creation: Play a game to demonstrate how we can chose to buy sustainable products when food shopping and how by doing this we can make sure the rainforest isn’t chopped down (board game, shows fragmentation and habitat disappearing when we buy unsustainable palm oil). Students all pledge to look for sustainable palm oil by drawing their faces and we later add these all to a tote bag (each child receives a bag with SPO shopping reminders ‘e.g. check the logo!’ for when they go food shopping).

Workshop 4: Quiz and creative session for students to share the message (make pledges, do a drama, dance, news article, comic, poster etc.)

Zoo trip: Tour of orang-utans habitat with facts to reinforce that these animals are losing their homes due to palm oil and reiterate sustainable palm oil. Hornbill game to show interesting behaviour of hornbill nesting and reinforce that these animals are losing their homes due to palm oil and reiterate sustainable palm oil.

Survey tool

What is the name of your school? [Open text field]

What year group are you in? [3 | 4 | 5 | 6]

What is your gender? [Boy | Girl | Other | I prefer not to say]

Have you visited Chester Zoo before? [Yes | No | Maybe | I don’t know]

What is palm oil? [Open text field]

Please write the names of anything found in your home that has palm oil in [Open text field]

What do you think the word sustainable means? [Open text field]

Do you think that YOU can help to protect endangered species?[Yes | No | Maybe | I don’t know] If yes, what could you do to help? [Open text field]

Open response scoring protocol

Initially, three researchers independently coded the same randomly selected subset (10%) of the responses to the four survey items, after which they compared their scores and discussed discrepancies until reaching a consistent interpretation of the scoring criteria. Next, one researcher scored the remaining dataset based on the agreed interpretation. Finally, one of the other initial researchers coded a second subset (10%) of the responses; we used a Cohen’s kappa statistic of inter-coder reliability to confirm agreement between the scores in this subset and the full dataset, finding that there was ‘almost perfect’ agreement (Landis and Koch Citation1977).

Scoring criteria for responses to our four knowledge-based survey items

Understanding of palm oil and associated conservation issues

Instruction for coder: For this question, it is worth remembering that the respondents are primary school aged children (7 – 11 years). The purpose of the question is to assess evidence of knowledge; their vocabulary might limit their capacity to communicate the ideas or facts, so we are looking for evidence of understanding rather than a ‘perfect answer’.

NA = no answer

0 = ‘I don’t know’, irrelevant/nonsensical answer, or incorrect explanation of palm oil

1 = vague response about it being an oil from a plant/palm – e.g. ‘it is oil from a palm tree’

2 = specific response about it being oil from the fruit of a palm and some mention of its importance - e.g. ‘it is oil from the fruit of a palm that is used in lot of products’

3 = very specific understanding of the oil, its uses and the related conservation threats – ‘it is oil from the fruit of a palm that is used in chocolates and shampoos and other products, farming it is killing orang-utans’

4 = very specific understanding of the topic and the issues surrounding it – e.g. ‘it is an oil from the fruit of an oil palm, there is high demand for it in many products leading to unsustainable farming and deforestation which are causing the loss of habitats for many species in Borneo and Sumatra’

Ability to describe personal pro-nature behaviours

Instruction for coder: For this question, it is worth remembering that the respondents are primary school aged children (7 – 11 years). The purpose of the question is to assess evidence of awareness of potential pro-nature actions/behaviours/choices; their vocabulary might limit their capacity to communicate what they know, so we are looking for evidence of awareness rather than a ‘perfect answer’.

NA = no answer

0 = ‘I don’t know’, nonsensical answer, or behaviour identified is not relevant to nature conservation

1 = vague platitudes about need for change, no specific behaviour mentioned – e.g. ‘save forests’, ‘protect animals’

2 = specific identification of pro-nature behaviour, but is at a general level, not feasible to address as an individual – e.g. ‘stop hunting’, ‘Don’t cut forests’

3 = identification of pro-nature behaviour, that is feasible to address as an individual – e.g. ‘staging campaign’, ‘buying sustainable palm oil’, ‘give money to conservation charity’

4 = very specific identification of an individually achievable pro-nature behaviour, and references the conservation issue addressed by the action/behaviour– e.g. ‘I will buy sustainable palm oil to help to protect orang-utans’

Ability to identify palm oil containing household products

Instruction for coder: Responses do not need to be specific to the brand level. Considering the age of the respondents, we do not expect distinction between different types of, for example, shampoo. The purpose of the question is to examine the understanding of palm oil used, to know what to look at when shopping. Knowing that some shampoo contains palm oil is enough. Answers with incorrect spelling should count only when it is clear what item the respondent is trying to write. If you can make an easy assessment of the meaning of a particular spelling then score it as if it were correctly spelled.

Count data, scored in separate columns.

1 column = number of correct answers

1 column = number of incorrect answers

Conceptual understanding of sustainability

Instruction for coder: For this question, it is worth remembering that the respondents are primary school aged children (7 – 11 years). The purpose of the question is to assess evidence of comprehension of a concept; their vocabulary might limit their capacity to communicate the concept, so we are looking for evidence of understanding rather than a ‘perfect answer’.

NA = no answer

0 = ‘I don’t know’, nonsensical/irrelevant answer, incorrect understanding of sustainability

1 = vague comprehension of the term, e.g. ‘something that is better to use’, ‘you can use it again’

2 = correct understanding of the concept, e.g. ‘something that can be used and replaced’

3 = evidenced understanding linked to real world example, e.g. ‘You can use something and replace it without damaging the environment’