Abstract

How to support young people’s agency is a key question of sustainability education. Action competence for sustainability is suggested covering the essential components of youth’s readiness to act both individually and collectively, but empirical tests of these associations are scarce. Therefore, this study explores the relationship between action competence and sustainability action among young people. We conducted a national survey of 15 to 29-year-old youths (N = 940) in Finland. Results of structural equation modeling show that self-perceived action competence for sustainability predicts private sphere behavior, but not sustainability action. Further analysis on the components of action competence reveals that high perceived knowledge and low outcome expectations predict low engagement in sustainability action. Knowledge and outcome expectations also affect behavior indirectly via willingness to act. We argue that actions and behaviors have different antecedents, and that the ability to recognize outcome uncertainty affects how young people’s sustainability agency is manifested.

Introduction

Transforming societies to align with sustainability visions requires fostering human agency and changing human action at many levels. On one hand, people need to attain a sufficient lifestyle that has minimal negative impact on the environment related, for example, to sustainable mobility (e.g. Boyes et al. Citation2014) and eating (e.g. Scott et al. Citation2022). Still, the impacts of adjusting personal behaviors on sustainability transformations have proved to be limited and the individual level achievements can tackle sustainability challenges only to certain degree. Thus, on the other hand, collective action that is directed on system-level change is needed to catalyze the wide-scale adoption of sustainable practices. In recent years, young people have been at the forefront of collective sustainability action. Since its inception, there has been more than 166 000 Fridays For Future -events worldwide, mobilizing some 18 000 000 predominantly young participantsFootnote1. However, it is not just strikes and demonstrations that should be paid attention to – young people express their agency and drive sustainability in diverse ways (O’Brien, Selboe, and Hayward Citation2018; Trott Citation2021; Tayne Citation2022).

To engage in action towards sustainability may require a variety of skills, knowledge, and attitudes. Frameworks that capture these sustainability competencies have been under intensive development during the last decade (Bianchi, Pisiotis, and Cabrera Giraldez Citation2022; Brundiers et al. Citation2021; Koskela and Paloniemi Citation2023; UNESCO Citation2017; Wiek, Withycombe, and Redman Citation2011, Willamo et al. Citation2018). Of particular interest has been action competence for sustainability, which has been defined as the overall will, confidence, and knowhow to bring about sustainability transformations (Sass et al. Citation2020). However, these is a lack of knowledge of how action competence – and especially its components – are related to actual sustainability promoting actions and behaviors.

In this article, we investigate the relationship between action competence and sustainability actions. Analyzing a survey sample of young people in Finland (N = 940), we ask how action competence for sustainability is related to both private sphere behavior and collective action that drive change. We pay particular attention to the differences between action and behavior as distinct holistic constructs and explore whether and how the components of action competence operate differently when predicting young people’s actions compared to behaviors.

Theory

Sustainability action and behavior

Sustainability calls for changing both individual and collective action and behavior. Changes can occur at the level of personal choices, in which an individual or a group decides to modify their everyday habits to reduce negative impacts on the environment. These are usually called private sphere pro-environmental behaviors (e.g. Kollmuss and Agyeman Citation2002; Stern Citation2000) or personal practices (Alisat and Riemer Citation2015), which consist of efforts such as waste sorting, buying eco-labelled products and switching to a plant-based diet. In addition, active efforts that are targeted on the behavior of others and a wider system-level change have been receiving increasing attention. Literature refers to these as environmental actions (Alisat and Riemer Citation2015) or actions for sustainability (Caniglia et al. Citation2020). Actions can range from low-level participatory civic actions, such as participating in a community event, to highly involved and political leadership actions, such as organizing a protest or boycott. Thus, actions combine elements of both activism and citizenship.

Previous research has identified several factors that distinguish actions from behaviors. Jensen and Schnack (Citation1997) highlight that actions are voluntary and targeted at bringing about change. However, Alisat and Riemer (Citation2015) remark that this description is not enough to differentiate actions from behaviors, since the latter can also be performed with high intention and environmentally focused motives. Instead, actions shift the emphasis from individuals’ lifestyle choices to changes at the societal level and address the systemic causes of socio-environmental problems (Alisat and Riemer Citation2015; Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010; Sass et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, actions involve a shared agency of multiple actors – individuals or collectives – which exercise their will in concerted ways (Caniglia et al. Citation2020). While behaviors can be performed collectively as well, in particular with immediate friends and family, they are usually confined within the private sphere. Thus, behaviors, once initiated, tend to evolve into more habitual, routinized, and household-centered practices (Alisat and Riemer Citation2015). To perform an action, however, it is essential to strive for a broader impact, which is ‘always a gamble in a certain way’ as one can struggle one’s whole life for such change without any tangible results (Kenis and Mathijs Citation2012). Caniglia et al. (Citation2020) argue further that actions for sustainability are embedded in complex and co-evolving socio-ecological systems in which interventions might have unpredictable consequences. This contextual realization requires actions to be flexible and constantly adapted to new evolving settings (Caniglia et al. Citation2020).

For young people, both actions and behaviors are relevant ways to express their sustainability agency and drive change. Despite the recent expressions of concern for the passive and disengaged attitude of young people towards politics (e.g. Gallant Citation2018) it is misleading to conclude that young people are inactive in society (Kallio Citation2018; Taft and Gordon Citation2013). Most actions and behaviors can be thought as a form of ‘off the radar’ democracy (Walsh and Black Citation2018) which emerges in various forms and places on young people’s own terms (Percy-Smith Citation2015). Young people’s readiness to act tends to become more visible in publicity-seeking events such as the 2019 global protests for a sustainable future (Wahlström et al. Citation2019). Moreover, as young people adjust their every-day life to align with the planetary boundaries, they hardly do it in isolation but socially and relationally through interactions with family and friends. This collective element in behaviors is key to allow youth to develop a sense of agency and to feel a part of the sustainability transformation (Trott Citation2021). However, while young people often perceive politicians to be the most responsible for tackling sustainability problems (Corner et al. Citation2015), they are expected to actively participate in finding solutions and changing the world but at the same time, the ways in which they participate are not always embraced in local communities (Kettunen Citation2021). This can cause frustration and diverse reactions – from disengagement to more radical actions – among youth (O’Brien, Selboe, and Hayward Citation2018).

Action competence for sustainability

Action competence refers to the will and ability to intentionally take part in democratic processes, to be ‘a qualified participant’ in society (Jensen and Schnack Citation1997). The concept is rooted in environmental and health education, yet it is nowadays linked closely to sustainability (Sass et al. Citation2020). Originally, action competence has been understood as an educational approach that highlights developing critical and reflective thinking and participation as opposed to behavior modifications (Breiting and Mogensen Citation1999; Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010). However, others have treated it as an educational outcome, an underlying latent capacity of individuals and groups (e.g. Olsson et al. Citation2020; Olsson, Gericke, and Boeve-de Pauw Citation2022). We will focus on the latter definition in this paper. Breiting and Mogensen (Citation1999) introduce that action competence has three components: knowledge of action possibilities, confidence in ones’ own influence and willingness to act. Thus, having more action competence means i) to know and build comprehensive and flexible knowledge around action possibilities, ii) to have self-efficacy and be empowered to take action and iii) to be passionate and willingly engage in sustainability transformations at different societal levels. These constructs are seen as essential in environmental and sustainability education in order not to rely on mere pre-determined behavior modifications, but to develop critical, reflective, and participatory skills by which young people can cope with wicked sustainability challenges (Breiting et al. Citation2009; Breiting and Mogensen Citation1999; Jensen and Schnack Citation1997; Sass et al. Citation2020).

Action competence can be seen as ‘a latent capacity to act before the action takes place’, and it can be hypothesized to be differentiated from and precede individual’s actual behavior (Olsson et al. Citation2020). Still, there have been only few research papers investigating the relationship between action competence and real-world sustainability efforts. While estimating the convergent validity of the self-perceived action competence for sustainability, Olsson et al. (Citation2020) conclude that action competence is highly correlated with self-reported sustainability behavior in their sample of Swedish 12–19-year-old students. Sass et al. (Citation2021) came to a similar conclusion while validating another instrument within early adolescents (aged 10–14) and call for further assessment of the connection between action competence and behavior. Both of the studies above used the behavior construct of the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire (Gericke et al. Citation2019), which mainly measures individual behaviors associated with the private sphere (e.g. ‘I recycle as much as I can’), paying less attention to collective and public sphere actions.

In another study, Finnegan (Citation2022) analyzed a sample of English students aged 16–18 and noted that higher levels of self-perceived action competence for sustainability were associated with higher frequencies of environmental action. However, environmental actions covered only participation in environmental protests and school sustainability efforts, such as eco-club, which might not fully account for the content of environmental action construct (Alisat and Riemer Citation2015). Moreover, Finnegan’s (Citation2022) analytic approach was limited; he only calculated the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the action competence -construct as a whole and the mean values of both environmental action items. Latent constructs with multiple indicators, such as action competence for sustainability, are more appropriately modelled in a latent variable system (e.g. McNeish and Wolf Citation2020).

The interconnections between knowledge, willingness, and outcome expectancy

Although previous studies show some evidence for a connection between action competence and sustainability actions, literature is scarce and has paid little attention to action competence’s – or its subconstructs’ – ability to predict different types of action. As we presented above, personal practices and collective actions for sustainability differ from each other in many ways. One essential difference relates to complexity and uncertainty, which are fundamentally part of sustainability challenges (e.g. Lönngren and Van Poeck Citation2021; Willamo et al. Citation2018). While the environmental impacts of behaviors are relatively easy to quantify and predict, tracing the legacies of collective action is a tedious task even for experts (Amenta et al. Citation2010; Nissen, Wong, and Carlton Citation2021). If one takes action against the prevailing system, one cannot truly know which efforts will produce the desired effects. Instead, actions emerge from a knowledge base that is always incomplete (Almers Citation2013). The notion of pluralism in action-oriented knowledge emphasizes that multiple kinds of knowledge and different ways of knowing are involved in actions that promote sustainability (Caniglia et al. Citation2020; Wals Citation2010). Therefore, reaching an end-goal of enough knowledge is not feasible when tackling wicked sustainability problems. Overall, this would suggest that the relationship between knowing how one should take action to reduce one’s negative environmental impacts might be more straightforward than the relationship between knowledge of action possibilities and actions targeted to change the system.

Nevertheless, sustainability-related knowledge is thought to be a prerequisite for successful action and an essential part of sustainability education (Frick, Kaiser, and Wilson Citation2004; Heimlich and Ardoin Citation2008; UNESCO Citation2017), although the effects and explanatory power of knowledge on actions and behaviors have been found to be modest at best (e.g. Geiger, Geiger, and Wilhelm Citation2019; Liobikienė and Poškus Citation2019; Otto and Pensini Citation2017; Paço and Lavrador 2017, Citation2017; Roczen et al. Citation2014). Conclusions about knowledge’s influence on sustainability efforts have been difficult to arrive at due to methodological deficits and variability of measures used in the literature (Geiger, Geiger, and Wilhelm Citation2019). Frick, Kaiser, and Wilson (Citation2004) outline that knowledge can be conceptualized in at least three forms. System knowledge comprises knowledge about the ecological systems and human-issued problems on them. Action-related knowledge encapsulates knowledge of behavioral options and possible courses of action (cf., ‘knowledge of action possibilities’ in action competence). Effectiveness knowledge enables comparisons between action possibilities, thus addressing the relative gains associated with specific behaviors and actions. The latter two have been argued to be stronger and more proximal determinants of environmental behaviors (Frick, Kaiser, and Wilson Citation2004; Roczen et al., Citation2014), yet the relationship is indistinct with public sphere actions (Liobikienė and Poškus Citation2019).

Some types of action-related knowledge may also be more readily available than others. Perceptions of how other people behave and what others might consider appropriate and inappropriate to do provide information about social norms influencing our behaviors also in the context of pro-environmental behaviors (Cialdini and Jacobson Citation2021; Farrow, Grolleau, and Ibanez Citation2017). In their limited yet important interview study, Kenis and Mathijs (Citation2012) observed that although young people may recognize the need for structural changes in society, they still consider actions for the climate first and foremost in terms of individual behavior change. Among young people, these behaviors are still much more prevalent and therefore more in line with social norms than collective strategies that address underlying causes of sustainability crisis. As we raised up above, some sustainability actions, such as blocking streets during demonstrations, can be considered even inappropriate (Kettunen Citation2021). These kinds of proscriptive social norms describing what is considered inappropriate to do can influence on behavior even more than prescriptive norms defining what is appropriate to do (Cialdini et al. Citation2006). In addition, even though young people adjust their personal practices, they may still feel that doing so has no real sustainability impact (Kenis and Mathijs Citation2012). This suggests that knowledge of behavior possibilities might be somewhat disconnected with the feeling of contributing to sustainability, and that it might not be necessary to have positive outcome expectations to engage in sustainability behaviors in the private sphere.

While the literature on action competence for sustainability treats the three dimensions – knowledge, confidence, and willingness – as subconstructs of action competence for sustainability, theories on predictors of individual behavior in different domains have proposed resemblant psychological constructs to be interlinked. The highly influential Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen Citation1991) posits intentions as the closest cognitive antecedent of actual behavior. Essentially, intentions capture motivational factors that influence behavior and thus indicate willingness to take action (cf. ‘willingness to act’ in action competence). The influence of intentions has been subsequently and thoroughly probed in the context of environmental behaviors and meta-analytic syntheses support its pivotal role in determining behavior (e.g. Bamberg and Möser Citation2007; Klöckner Citation2013).

Intentions, in turn, have been assumed to be affected by considerations of the likely consequences of behavior, including normative beliefs, perceived behavior control and outcome expectancy (Ajzen Citation1991). Outcome expectations, that is, beliefs that individual or collective efforts can produce desired sustainability outcomes (cf., ‘confidence in one’s own influence’ in action competence), have also been highlighted by social cognitive theory, which postulates that outcome expectations affect actions both directly and indirectly through interests and goal setting (Sawitri, Hadiyanto, and Hadi Citation2015). In addition, social identity approaches underline that it is the sense of collective efficacy, in addition to emotions, group identification and norms, that drives collective sustainability actions (Barth et al. Citation2021; Fritsche et al. Citation2018; Fritsche and Masson Citation2021). Empirically, goal-focused perceived efficacy has been found to be an important predictor of both private sphere behaviors and public sphere actions (e.g. Lee et al. Citation2014; Hamann and Reese Citation2020).

To sum up, although action competence and consequently its components are expected to be related to young people’s concrete efforts that advance sustainability, some competencies might be more predictive of certain types of action than of others. Especially the role of knowledge of action possibilities in determining sustainability efforts is in a need for clarification. To contribute to the previous research, in this article we ask how young people’s self-perceived action competence for sustainability is related to their self-rated sustainability actions and behaviors. We also ask whether action competence and its association with sustainability efforts is appropriately modelled via a higher-order construct. Finally, we ask whether confidence in one’s own influence and knowledge of action possibilities have indirect effects on sustainability actions and behaviors through willingness to act.

Materials and methods

Study context: young people, action competence and sustainability themes in Finland

The Finnish curricula have included sustainability themes for decades (Rokka Citation2011). For example, the current National core curriculum for basic education (POPS. Citation2014) highlights that ‘Pupils are guided towards a sustainable way of life and understanding the importance of sustainable development. The knowledge and skills as well as values, attitudes and will that promote these run throughout the whole curriculum’. Thus, elements of sustainability and action competence are present throughout the curriculum. Sustainability issues are also widely present in the public sphere. In 2021, the annual Finnish Youth Barometer examined young people’s views on sustainable development and climate issues and found out that the media and social media are the most important sources of environmental information for young people (Kiilakoski Citation2021).

Procedure, participants, and measures

We conducted a national survey study. The study design did not require an ethical review in Finland (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity Citation2019). Prior to collecting the data, the survey measures outlined below were translated following the approach discussed by Douglas and Craig (Citation2007), adapted to the Finnish context, and tested with four groups of young people. The details of the translation/adaptation process and the instruments used in this study are shown in Appendix A.

We requested a sample of 1000 Finnish speaking young people aged 15–29 from an online panel maintained by Kantar Media Finland Oy. The panel members are offered a small reward for filling our different questionnaires regularly. At the beginning of the survey, participants were informed about the purpose of the study. We also provided a short description of sustainability (see Appendix A) to ensure that the participants considered the questionnaire items from a similar perspective.

The data was collected during November–December 2021 until 1009 full responses were gathered, and since we did not include ‘I don’t know’ response option, we have no missing data. This might have implications on the quality of the data since full responses may include careless and/or dishonest response patterns. Therefore, we took extensive measures to detect low quality data, disclosed in detail in Appendix B. After screening the data, 940 participants were retained, of which 43% were male, 56% female, and 1% did not specify. 25% were aged between 15–19, 37% were aged between 20–24, and 38% were aged between 25–29 years old. Mean age was 22.8, with a standard deviation of 4.1. Compared to 2021 official statistics (Official Statistics of Finland, Citation2023), male participants and the youngest age group were slightly underrepresented in our sample (49% and 32% in official statistics, respectively).

Action competence was measured with a novel instrument of Self-Perceived Action Competence for Sustainability (Olsson et al. Citation2020). The instrument consists of 12 items covering the three subconstructs of action competence: knowledge of action possibilities (KAP), confidence in one’s own influence (COI) and willingness to act (WTA). The scale has a fully labelled 5-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neither agree nor disagree; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree). Since our sample includes respondents that currently do not attend a school, two items (KAP2 and WTA4) that deal specifically with school issues were not included in our analyses.

In this study, we treated sustainability action and behavior as separate latent constructs, which reflect individuals’ overall propensities to engage in them. The choice is in line with our aim to explore sustainability action and behavior from a more holistic view and supported by our empirical material, including strong correlations especially among sustainability action items (.54–.84) and the fit of the measurement model (see appendix C). The study builds on our previous analysis on the same data showing how sustainability actions and behaviors differed from one another empirically. Thus, sustainability action was measured with 16 items adapted from Alisat and Riemer (Citation2015) Environmental Action Scale, which taps into the diverse ways in which people take action for sustainability. These actions range from low-profile efforts, such as participating in an educational event and raising sustainability awareness in social media, to highly devoted activism, such as organizing a protest or a public event. Sustainability behavior was measured with eight items about different private sphere behaviors, such as preferring vegetarian meals, buying eco-labelled products, educating oneself and talking with others about sustainability. The selection of behavior items was inspired by previous literature on pro-environmental behaviors, and we especially considered items that might have a higher impact (Markle Citation2013). Both actions and behaviors were assessed on a 5-point scale (0 = never; 1 = rarely; 2 = sometimes; 3 = frequently; 4 = very frequently) according to the rate at which the respondent had performed them in the last six months.

Finally, we considered few demographic variables (age, sex) that are likely to have an impact on the measures described above and added them as covariates in our structural models.

Analytical strategy

We used the structural equation modeling (SEM) framework to explore our research questions. First, we evaluated each of the measuring instruments independently by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis on them and assessing the scales’ reliabilities (McDonald’s omega). Second, we specified a full measurement model, including all the measuring instruments, but with no path coefficients yet defined. By separating our model into its measurement and structural portions allows us to detect misspecifications in the former, if present, and aid in preventing nonconvergence problems further ahead of the analysis (e.g. Mueller & Hancock, Citation2008).

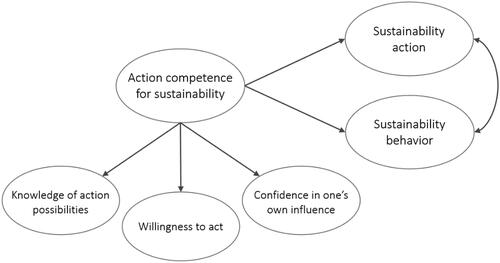

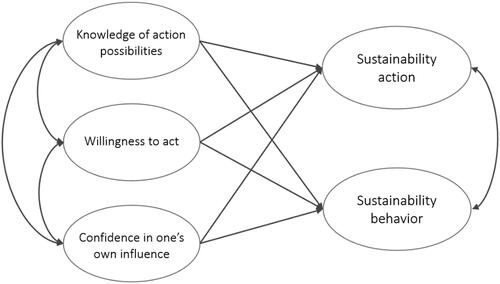

In model A, we estimated how action competence for sustainability as a higher order factor predicts sustainability action and behavior (). In model B, we disaggregated action competence in its sub-scales to see how they were associated with sustainability efforts (). In addition, in model B we specified direct associations from knowledge of action possibilities and confidence in one’s own influence on willingness to act, in order to estimate their indirect effects on sustainability action and behavior. We note that the structural portion of the latter model is just-identified, meaning that its fit is identical to the full measurement model if covariates were excluded. However, we found no theoretical reason to constrain any of the paths.

Figure 1. Model A, in which action competence is specified as a higher order construct directly predicting sustainability action and behavior.

Figure 2. Model B, in which action competence is disaggregated in its core parts, each directly predicting actions and behaviors. Also two factor correlations were specified as direct effects.

Along the phases we evaluated local and global fit of the models and the need for estimating additional error covariances that are also theoretically meaningful, besides the ones previously defined for environmental actions (Alisat and Riemer Citation2015). Thus, we inspected the correlation residual matrices, noting high absolute residuals (>.10) and the pattern of residuals as suggested by Kline (Citation2016, pp. 268–269, 278). We examined a set of fit statistics advised by Kline (Citation2016, p. 269), that is, model chi-square, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Following recent recommendations (McNeish, An, and Hancock Citation2018) we refrained from hanging onto firm cutoff criteria and evaluated the fit indices in the context of the scales’ measurement quality (standardized factor loadings and omega reliabilities).

All the models were run using the ‘lavaan’ package in R (version 4.0.2). We did not conduct any formal tests of normality, since these tests are highly overpowered in large samples, detecting even the slightest deviation from normality (e.g. Kline Citation2016, pp 74–77; Osborne, Citation2013, pp 96–98). Instead, to combat non-normality, we fit the models with two estimators: maximum likelihood with Satorra-Bentler scaling (MLM), which utilizes a scaling factor to better approximate chi square under non-normality, and weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV or robust DWLS), which treats the data as ordinal and uses polychoric correlations (Finney and DiStefano Citation2013). As the results pointed towards the same conclusions, only the results from MLM estimation are presented.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between the latent variables are shown in , global fit indices are reported in , while structural estimates are shown in . Evaluations of the measurement models and consequent model respecifications are disclosed in Appendix C.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, Reliability estimates and bivariate correlations between latent variables.

Table 2. Global fit statistics of the models.

Table 3. Path coefficient estimates, their associated standard errors, and p-values.

Considering model A, action competence for sustainability is strongly associated with sustainability behaviors, but the association is virtually zero with sustainability actions. The model explains 51% of the variance of sustainability behavior compared to only 9% of sustainability action. However, model A’s fit indices point out to some issues. For example, SRMR is approaching .10, which may indicate poor fit in terms of high mean absolute correlation residuals. Inspecting the correlation residuals and modification indices reveals that KAP-items and the whole construct of knowledge of action possibilities might be negatively associated with sustainability actions.

Accordingly, model B, in which action competence’s sub scales directly predict sustainability efforts, seems to fit better to the data (Δχ2 = 91.569, p < .000; AICmodel A > AICmodel B). In model B, knowledge of action possibilities is negatively related to sustainability actions, predicting that a one unit increase in self-perceived knowledge leads to .699 units decrease in propensity to engage in sustainability actions. Interestingly, while the zero-order correlation between KAP and sustainability behavior was positive, the direct effect of knowledge on behavior is nonexistent. A similar redundancy occurs with the effect of confidence in one’s own influence on sustainability behavior. Meanwhile, COI is the strongest positive predictor of sustainability action and, by contrast, willingness to act most strongly predicts sustainability behavior. Model B explains approximately 50% and 24% of the variance of sustainability behavior and action, respectively.

Finally, both KAP and COI are positively related to willingness to act, but the indirect effects are only significant on sustainability behavior. However, the indirect effect of knowledge on behavior is small in magnitude, and since the direct effect of knowledge on behavior is slightly negative, the total effect of knowledge on behavior is negligible. Furthermore, the indirect effect of COI on behavior heightens the overall effect of outcome expectancy on behavior.

Discussion

Action competence for sustainability has been assumed to be predictive of young people’s efforts to promote sustainability (Olsson et al. Citation2020). In this paper, we analyzed a nationally representative survey of young people in Finland to investigate the phenomenon and found that action competence as a higher order construct was positively related to personal practices, such as preferring a plant-based diet, but it didn’t predict collective actions that are targeted at a more profound system-level change, such as participating in or organizing sustainability-themed events and protests. This is unexpected, since the theory of action competence gives emphasis to the type of action that aims to solve the problems or change the conditions that created the problems in the first place (Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010). Furthermore, our analysis shed light on the sub-constructs of action competence, that is, knowledge of action possibilities, willingness to act and confidence in one’s own influence, and showed how they might be interrelated and operate differently in relation to action and behavior.

Interestingly, our results suggest that scoring high on knowledge of action possibilities is associated with less sustainability action, and that the relationship is nonexistent with private-sphere behavior. These rather unintuitive findings may have different explanations. First, it is crucial to note that the instrument of action competence for sustainability measures the level of perceived knowledge, not actual knowledge (cf., Geiger, Geiger, and Wilhelm Citation2019). Self-assessed knowledge may rather reflect individual’s confidence in one’s knowledge level (Koriat Citation2012). Respondents who score high on KAP-scale might thus represent young people who are more certain about their knowledge base. They feel that they know what should be done in various settings to promote sustainability and they feel that they know the different viewpoints that people have on sustainability issues. High confidence in one’s awareness speaks of a situation in which uncertainty and risks are not seen as essential features of sustainability. As the complexity of the sustainability problems becomes more apparent for youths turning late adolescence and early adulthood, young people may employ various coping strategies to deal with the ambivalence, such as believing that there’s nothing to worry about or trusting science to solve the issues (Ojala Citation2012). These mindsets obviate the need and motivation for taking risky actions with unforeseeable outcomes.

By contrast, respondents who score less on KAP-scale are not necessarily short of knowledge, but they may recognize their limits of knowing and deliberate more thoroughly on the proper actions to take. Scoring low on KAP-scale might mean that these respondents acknowledge the uncertainties and risks that are an inevitable part of sustainability, which is precisely why they have a greater urge to make sustainability efforts targeted at the system level. It is hard to know how one should act to achieve or even approach a sustainable future when, in fact, the future in unknown. Parallel to this, literature on eco-anxiety has underscored that collective action may arise from a need to cope with the uncertainties and feelings of helplessness caused by the sustainability crisis (Pihkala Citation2020). In a large cross-sectional design, Ogunbode et al. (Citation2022) showed that climate anxiety had a significant positive relationship with both pro-environmental behavior and participation in climate protests particularly in European countries, and the strongest associations were found in Finland.

Another potential explanation is related to social norms. It is possible that knowledge of action possibilities reflects social norms related to sustainability behaviors and actions. In our study, private sphere behaviors were much more prevalent than public sphere actions suggesting that youth might feel a normative pressure to engage in these behaviors whereas the social pressure to engage in sustainability actions is perceived lower and some actions might be considered even inappropriate (Kettunen Citation2021). We know from prior studies that Finnish youths perceive for example private consumption behavior as a more efficient way to influence environmental issues than collective actions such as climate strikes (Kiilakoski Citation2021). Thus, our respondents might have thought about the normative behaviors while responding to the questions about their knowledge what should be done in terms of sustainability. The Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen Citation1991) suggests that these kinds of normative beliefs influence behavior through behavioral intentions. In line with this, KAP was indeed indirectly related to sustainability behaviors via WTA, while the direct effect of KAP on behaviors was nonexistent. Social norms related interpretation of KAP-construct could also explain the low level of engagement in sustainability actions among those scoring high on KAP. However, it is less clear how social norms would explain the high level of engagement in sustainability actions amongst respondents who scored low on KAP.

Since engaging in sustainability actions rarely results in tangible sustainability outcomes, it is understandable that confidence in one’s own influence was the strongest predictor of sustainability action. Our results hence align with previous findings that highlight the role of goal-focused perceived efficacy in determining collective action (e.g. Fritsche et al. Citation2018; Fritsche and Masson Citation2021; Hamann and Reese Citation2020; Lee et al. Citation2014). For private sphere behaviors the direct effect of outcome expectancy was slightly weaker, yet their confidence intervals overlap. However, outcome expectancy also had an effect on behavior indirectly through willingness to act, supporting the results of previous studies on the mediating role of intentions in predicting pro-environmental behavior (Bamberg and Möser Citation2007; Klöckner Citation2013). Although Kenis and Mathijs (Citation2012) proposed that the choice for individual behavior change might not be a genuine strategy for change, our results indicate that young people’s confidence in the outcomes of their efforts is an important predictor of both action and behavior.

Our results and the discussion above underline a need for reconsidering how action competence for sustainability is appropriately measured and modelled. When used to predict different sustainability-related outcomes, treating action competence as a higher order construct may disguise some associations that are of high theoretical importance. In particular, special attention should be paid onto the knowledge component of action competence, which behaved in an unexpected way in this study. Although the theory behind the sub-scale rests upon the notion of adaptive and flexible knowledge, self-reflectiveness and critical thinking (Almers Citation2013; Mogensen Citation1997; Olsson et al. Citation2020; Sass et al. Citation2020), the operationalization seems not to fully capture that idea. ‘I know how one should take action…’ may be interpreted such that there is a set of correct actions to take in order to contribute to sustainability and that no critical reflection is needed. Mogensen (Citation1997) portrays critical thinking as a process of actively examining and questioning the world around oneself which must lead to a reasoned judgement. Evaluated against this, the KAP-items only reflect an outcome of a thinking process that has not been observed, a process that might not have included steps of critical evaluation and reflection. Thus, future work might explore whether individual understanding of knowledge-related uncertainty and tendency to critically evaluate one’s knowledge base could moderate the relationship between KAP and sustainability action. Future studies might also measure objective level of knowledge rather than perceived knowledge to further specify the actual role of knowledge of action possibilities. Finally, the content validity of the KAP sub-scale could be revisited considering our results and discussion to better incorporate the notions of critical thinking and flexible knowledge.

The results of our study have several implications for sustainability educational purposes. First, mere willingness to contribute to sustainability seems to be insufficient for collective actions to emerge. Instead, it is essential to strengthen young people’s beliefs that individual and collective efforts can produce desired sustainability outcomes. Second, relying on gaining more knowledge and eliminating the uncertainty that surrounds it might actually hinder young people from taking action. For decades, it has been highlighted that basic knowledge is necessary but not sufficient for sustainability education to achieve its goals (e.g. Cantell et al. Citation2019; Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010). Strong arguments have been made that sustainability education should support the development of thinking skills that help learners to embrace uncertainty, reflect on their values, appraise the adequacy of their knowledge base, and adjust their actions accordingly (Bianchi, Pisiotis, and Cabrera Giraldez Citation2022; Cantell et al. Citation2019; Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010; UNESCO Citation2017; Wiek, Withycombe, and Redman Citation2011). The concept of ‘resilience’ presumes that a key quality of an effective real-life learner is the ability to stay intelligently engaged with a complex and unpredictable situation (Masten and Obradovic Citation2008; Sterling Citation2010). Thus, to undermine uncertainty is to undermine the potential sustainability agency of young people.

Finally, we will discuss some of the limitations of this study. First, the study counts upon a cross-sectional design, which inhibits us from making any causal claims. Thus, any direct pathway in our models depends on the soundness of theory and the quality of previous studies. Second, the structural portion of our second model was just-identified, meaning that we did not formally test the existence of the specified structural paths. Third, our sample is based in Finland, so we cannot outright infer that our results would hold in other cultures and countries. However, we might assume generalizability to other high-income European or at least Scandinavian countries. Fourth, self-assessed behavior constructs always have their own limitations, since self-reported behavior may not fully correspond to actual behavior (e.g. Lange and Dewitte Citation2019). Especially the interpretation of sustainability action -items may not fully converge among survey respondents, since people have different notions of what is most important in sustainability. However, the focus of our study was not to compare single items – instead, we were interested in sustainability action as a latent construct, which reflects the propensity to engage in sustainability action. This construct, just as sustainability as a concept, is characterized by complexity, ambiguity, ongoing evolution, and tradeoffs between social and environmental goals.

Conclusions

Sustainability transformation is about changing both individual and collective action and behavior across all societal levels. It is vital to recognize the preconditions that allow for young people’s sustainability agency to emerge as concrete and impactful efforts based on their competences and knowledge. In our study, despite the emphasis in current key theories, action competence for sustainability as a higher order construct predicted private sphere behaviors rather than collective actions. More precisely, high perceived knowledge and low goal-focused perceived efficacy predicted low engagement in sustainability action. These findings are of key relevance for sustainability education and to understand youth engagement, since when young people have confidence in their own influence and recognize knowledge as always incomplete, they are more likely to act collectively for sustainability. The ability to embrace uncertainty plays a major role here, and education striving to support young people’s sustainability agency would do well to equip young people with the skills and mindsets to acknowledge and face uncertainties, complexities and ambiguities related to sustainability transformations they are engaging in.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Syke’s researchers Marianne Aulake and Terhi Arola for participating in the translation process of the survey instruments.

Disclosure statement of interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study will be openly available in the Finnish Social Science Data Archive at https://www.fsd.tuni.fi/en/ once the research project has ended by the end of 2023.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Iikka Oinonen

Iikka Oinonen, MSc, is a researcher at the Finnish Environment Institute. His main interests lie in studying action and behavior related to sustainability, and how to support young people’s sustainability agency.

Tuija Seppälä

Tuija Seppälä, PhD, is a social psychologist and a senior research scientist at the Finnish Environment Institute. Her current research interests include young people’s agency in sustainability transition.

Riikka Paloniemi

Riikka Paloniemi, PhD, is a unit director at the Finnish Environment Institute. In her research she aims to integrate the perspectives of people and the planet in order to encourage sustainability.

Notes

1 https://fridaysforfuture.org/what-we-do/strike-statistics/ [data updated at 2023-01-08]

References

- Ajzen, I. 1991. “The Theory of Planned Behavior.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50 (2): 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alisat, S., and M. Riemer. 2015. “The Environmental Action Scale: Development and Psychometric Evaluation.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 43: 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.05.006

- Almers, E. 2013. “Pathways to Action Competence for Sustainability—Six Themes.” The Journal of Environmental Education 44 (2): 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2012.719939

- Amenta, E., N. Caren, E. Chiarello, and Y. Su. 2010. “The Political Consequences of Social Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (1): 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120029

- Bamberg, S., and G. Möser. 2007. “Twenty Years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A New Meta-Analysis of Psycho-Social Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behaviour.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 27 (1): 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.12.002

- Barth, M., T. Masson, I. Fritsche, K. Fielding, and J. R. Smith. 2021. “Collective Responses to Global Challenges: The Social Psychology of Pro-Environmental Action.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 74: 101562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101562

- Bianchi, G., U. Pisiotis, and M. Cabrera Giraldez. 2022. GreenComp The European Sustainability Competence Framework. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/13286

- Boyes, E., M. Stanisstreet, K. Skamp, M. Rodriguez, G. Malandrakis, R. W. Fortner, A. Kilinc, et al. 2014. “An International Study of the Propensity of Students to Limit Their Use of Private Transport in Light of Their Understanding of the Causes of Global Warming.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 23 (2): 142–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2014.891425

- Breiting, S., K. Hedegaard, F. Mogensen, K. Nielsen, and K. Schnack. 2009. Action Competence, Conflicting Interests and Environmental Education – the MUVIN Programme. Copenhagen: Aarhus University.

- Breiting, S., and F. Mogensen. 1999. “Action Competence and Environmental Education.” Cambridge Journal of Education 29 (3): 349–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764990290305

- Brundiers, K., M. Barth, G. Cebrián, M. Cohen, L. Diaz, S. Doucette-Remington, W. Dripps, et al. 2021. “Key Competencies in Sustainability in Higher Education—toward an Agreed-upon Reference Framework.” Sustainability Science 16 (1): 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00838-2

- Caniglia, G., C. Luederitz, T. von Wirth, I. Fazey, B. Martin-López, K. Hondrila, A. König, et al. 2020. “A Pluralistic and Integrated Approach to Action-Oriented Knowledge for Sustainability.” Nature Sustainability 4 (2): 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00616-z

- Cantell, H., S. Tolppanen, E. Aarnio-Linnanvuori, and A. Lehtonen. 2019. “Bicycle Model on Climate Change Education: Presenting and Evaluating a Model.” Environmental Education Research 25 (5): 717–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1570487

- Cialdini, Robert B., Linda J. Demaine, Brad J. Sagarin, Daniel W. Barrett, Kelton Rhoads, and Patricia L. Winter. 2006. “Managing Social Norms for Persuasive Impact.” Social Influence 1 (1): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510500181459

- Cialdini, R. B., and R. P. Jacobson. 2021. “Influence of Social Norms on Climate Change-Related Behaviors.” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 42: 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.01.005

- Corner, A., O. Roberts, S. Chiari, S. Völler, E. S. Mayrhuber, S. Mandl, and K. Monson. 2015. “How Do Young People Engage with Climate Change? The Role of Knowledge, Values, Message Framing, and Trusted Communicators.” WIREs Climate Change 6 (5): 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.353

- Curran, P. G. 2016. “Methods for the Detection of Carelessly Invalid Responses in Survey Data.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 66: 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.07.006

- Douglas, S. P., and C. S. Craig. 2007. “Collaborative and Iterative Translation: An Alternative Approach to Back Translation.” Journal of International Marketing 15 (1): 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.15.1.030

- Dunn, A. M., E. D. Heggestad, L. R. Shanock, and N. Theilgard. 2018. “Intra-Individual Response Variability as an Indicator of Insufficient Effort Responding: Comparison to Other Indicators and Relationships with Individual Differences.” Journal of Business and Psychology 33 (1): 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9479-0

- Farrow, K., G. Grolleau, and L. Ibanez. 2017. “Social Norms and Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Review of the Evidence.” Ecological Economics 140: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.04.017

- Finnegan, W. 2022. “Educating for Hope and Action Competence: A Study of Secondary School Students and Teachers in England.” Environmental Education Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2120963

- Finney, S. J., and C. DiStefano. 2013. “Nonnormal and Categorical Data in Structural Equation Modeling.” In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, edited by G. R. Hancock & R. O. Mueller. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2120963

- Finnish National Board on Research Integrity. 2019. “The Ethical Principles of Research with Human Participants and Ethical Review in the Human Sciences in Finland. ” Finnish National Board on Research Integrity guidelines, 3/2019.

- Frick, J., F. G. Kaiser, and M. Wilson. 2004. “Environmental Knowledge and Conservation Behavior: Exploring Prevalence and Structure in a Representative Sample.” Personality and Individual Differences 37 (8): 1597–1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.02.015

- Fritsche, I., M. Barth, P. Jugert, T. Masson, and G. Reese. 2018. “A Social Identity Model of Pro-Environmental Action (SIMPEA).” Psychological Review 125 (2): 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000090

- Fritsche, I., and T. Masson. 2021. “Collective Climate Action: When Do People Turn into Collective Environmental Agents?” Current Opinion in Psychology 42: 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000090

- Gallant, N. 2018. “The ‘Good,’the ‘Bad’and the ‘Useless’: Young People’s Political Action Repertoires in Quebec.” In Young People Re-Generating Politics in Times of Crises, edited by S. Pickard & J. Bessant. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58250-4_5

- Geiger, S. M., M. Geiger, and O. Wilhelm. 2019. “Environment-Specific Vs. general Knowledge and Their Role in Pro-Environmental Behavior.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 718. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00718

- Gericke, N., J. Boeve-de Pauw, T. Berglund, and D. Olsson. 2019. “The Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire: The Theoretical Development and Empirical Validation of an Evaluation Instrument for Stakeholders Working with Sustainable Development.” Sustainable Development 27 (1): 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1859

- Hamann, K. R., and G. Reese. 2020. “My Influence on the World (of Others): Goal Efficacy Beliefs and Efficacy Affect Predict Private, Public, and Activist Pro-Environmental Behavior.” Journal of Social Issues 76 (1): 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12369

- Heimlich, J. E., and N. M. Ardoin. 2008. “Understanding Behavior to Understand Behavior Change: A Literature Review.” Environmental Education Research 14 (3): 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802148881

- Jensen, B. B., and K. Schnack. 1997. “The Action Competence Approach in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 3 (2): 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350462970030205

- Kallio, K. P. 2018. “Not in the Same World: Topological Youths, Topographical Policies.” Geographical Review 108 (4): 566–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/gere.12266

- Kenis, A., and E. Mathijs. 2012. “Beyond Individual Behaviour Change: The Role of Power, Knowledge and Strategy in Tackling Climate Change.” Environmental Education Research 18 (1): 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.576315

- Kettunen, M. 2021. “We Need to Make Our Voices Heard”: Claiming Space for Young People’s Everyday Environmental Politics in Northern Finland.” Nordia Geographical Publications 49 (5): 32–48. https://doi.org/10.30671/nordia.98115

- Kiilakoski, T. (ed.) 2021. Sustainability Youth Barometer 2021. Helsinki: Publications of the Finnish Youth Research Society/Finnish Youth Research Network 237.

- Kline, R. B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 4th ed. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Klöckner, C. A. 2013. “A Comprehensive Model of the Psychology of Environmental Behaviour—A Meta-Analysis.” Global Environmental Change 23 (5): 1028–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.014

- Kollmuss, A., and J. Agyeman. 2002. “Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behavior?” Environmental Education Research 8 (3): 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401

- Koriat, A. 2012. “The Subjective Confidence in One’s Knowledge and Judgments: Some Metatheoretical Considerations.”. In: M. Beran, J. L. Brandl, J. Perner & J. Proust (Eds.), The Foundations of Metacognition, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Koskela, I. M., and R. Paloniemi. 2023. “Learning and Agency for Sustainability Transformations: Building on Bandura’s Theory of Human Agency.” Environmental Education Research 29 (1): 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2102153

- Lange, F., and S. Dewitte. 2019. “Measuring Pro-Environmental Behavior: Review and Recommendations.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 63: 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.04.009

- Lee, Y. K., S. Kim, M. S. Kim, and J. G. Choi. 2014. “Antecedents and Interrelationships of Three Types of Pro-Environmental Behavior.” Journal of Business Research 67 (10): 2097–2105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.04.018

- Liobikienė, G., and M. S. Poškus. 2019. “The Importance of Environmental Knowledge for Private and Public Sphere Pro-Environmental Behavior: Modifying the Value-Belief-Norm Theory.” Sustainability 11 (12): 3324. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123324

- Lönngren, J., and K. Van Poeck. 2021. “Wicked Problems: A Mapping Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 28 (6): 481–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2020.1859415

- Markle, G. L. 2013. “Pro-Environmental Behavior: Does It Matter How It’s Measured? Development and Validation of the Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (PEBS).” Human Ecology 41 (6): 905–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-013-9614-8

- Masten, A. S., and J. Obradovic. 2008. “Disaster Preparation and Recovery: Lessons from Research on Resilience in Human Development.” Ecology and Society 13 (1): 9. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267914

- McNeish, D., J. An, and G. R. Hancock. 2018. “The Thorny Relation between Measurement Quality and Fit Index Cutoffs in Latent Variable Models.” Journal of Personality Assessment 100 (1): 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2017.1281286

- McNeish, D., and M. G. Wolf. 2020. “Thinking Twice about Sum Scores.” Behavior Research Methods 52 (6): 2287–2305. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01398-0

- Meade, A. W., and S. B. Craig. 2012. “Identifying Careless Responses in Survey Data.” Psychological Methods 17 (3): 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028085

- Mogensen, F. 1997. “Critical Thinking: A Central Element in Developing Action Competence in Health and Environmental Education.” Health Education Research 12 (4): 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/12.4.429

- Mogensen, F., and K. Schnack. 2010. “The Action Competence Approach and the ‘New’ Discourses of Education for Sustainable Development, Competence and Quality Criteria.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903504032

- Mueller, R. O., and G. R. Hancock. 2008. “Best Practices in Structural Equation Modeling.” In Best Practices in Quantitative Methods, edited by J. W. Osborne. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Nissen, S., J. H. Wong, and S. Carlton. 2021. “Children and Young People’s Climate Crisis Activism–a Perspective on Long-Term Effects.” Children’s Geographies 19 (3): 317–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2020.1812535

- O’Brien, K., E. Selboe, and B. M. Hayward. 2018. “Exploring Youth Activism on Climate Change: Dutiful, Disruptive, and Dangerous Dissent.” Ecology and Society 23 (3): 42. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10287-230342

- Ogunbode, C. A., R., Doran D. Hanss, M. Ojala, K. Salmela-Aro, K. L. Van Den Broek, N. Bhullar, et al. 2022. “Climate Anxiety, Wellbeing and Pro-Environmental Action: Correlates of Negative Emotional Responses to Climate Change in 32 Countries.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 84: 101887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101887.

- OSF (Official Statistics of Finland). 2023. “Population Structure [online publication]. ” ISSN = 1797-5395. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [Referenced: 23.5.2023]. https://stat.fi/en/statistics/vaerak#reference

- Ojala, M. 2012. “Regulating Worry, Promoting Hope: How Do Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Cope with Climate Change?” International Journal of Environmental and Science Education 7 (4): 537–561.

- Olsson, D., N. Gericke, and J. Boeve-de Pauw. 2022. “The Effectiveness of Education for Sustainable Development Revisited–a Longitudinal Study on Secondary Students’ Action Competence for Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 28 (3): 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2033170

- Olsson, D., N. Gericke, W. Sass, and J. Boeve-de Pauw. 2020. “Self-Perceived Action Competence for Sustainability: The Theoretical Grounding and Empirical Validation of a Novel Research Instrument.” Environmental Education Research 26 (5): 742–760. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1736991

- Osborne, J. 2013. Best Practices in Data Cleaning: A Complete Guide to Everything You Need to Do before and after Collecting Your Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Otto, S., and P. Pensini. 2017. “Nature-Based Environmental Education of Children: Environmental Knowledge and Connectedness to Nature, Together, Are Related to Ecological Behaviour.” Global Environmental Change 47: 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.09.009

- Paço, A., and T. Lavrador. 2017. “Environmental Knowledge and Attitudes and Behaviours towards Energy Consumption.” Journal of Environmental Management 197: 384–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.03.100

- Percy-Smith, B. 2015. “Negotiating Active Citizenship: Young People’s Participation in Everyday Spaces.”. In: Politics, Citizenship and Rights. Geographies of Children and Young People (7). London: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4585-94-1_26-1

- Pihkala, P. 2020. “Eco-Anxiety and Environmental Education.” Sustainability 12 (23): 10149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310149

- POPS. 2014. “ Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet 2014. ” Helsinki: Opetushallitus. [English overview https://www.oph.fi/en/education-and-qualifications/national-core-curriculum-basic-education]

- Roczen, N., F. G. Kaiser, F. X. Bogner, and M. Wilson. 2014. “A Competence Model for Environmental Education.” Environment and Behavior 46 (8): 972–992. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916513492416.

- Rokka, P. 2011. “Peruskoulun ja perusopetuksen vuosien 1985, 1994 ja 2004 opetussuunnitelmien perusteet poliittisen opetussuunnitelman teksteinä. ” Dissertation, Tampere University Press. https://urn.fi/urn:isbn:978-951-44-8456-8

- Sass, W., J. Boeve-De Pauw, S. De Maeyer, and P. Van Petegem. 2021. “Development and Validation of an Instrument for Measuring Action Competence in Sustainable Development within Early Adolescents: The Action Competence in Sustainable Development Questionnaire (ACiSD-Q).” Environmental Education Research 27 (9): 1284–1304.

- Sass, W., J. Boeve-de Pauw, D. Olsson, N. Gericke, S. De Maeyer, and P. Van Petegem. 2020. “Redefining Action Competence: The Case of Sustainable Development.” The Journal of Environmental Education 51 (4): 292–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2020.1765132

- Sawitri, D. R., H. Hadiyanto, and S. P. Hadi. 2015. “Pro-Environmental Behavior from a Social Cognitive Theory Perspective.” Procedia Environmental Sciences 23: 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2015.01.005

- Scott, S., S. Booth, P. Ward, R. Woodman, J. Coveney, and K. Mehta. 2022. “Understanding Engagement in Sustainable Eating and Education: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2021.2024931

- Sterling, S. 2010. “Learning for Resilience, or the Resilient Learner? Towards a Necessary Reconciliation in a Paradigm of Sustainable Education.” Environmental Education Research 16 (5-6): 511–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2010.505427

- Stern, P. C. 2000. “Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior.” Journal of Social Issues 56 (3): 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00175

- Taft, J. K., and H. R. Gordon. 2013. “Youth Activists, Youth Councils, and Constrained Democracy.” Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 8 (1): 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197913475765

- Tayne, K. 2022. “Buds of Collectivity: Student Collaborative and System-Oriented Action towards Greater Socioenvironmental Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 28 (2): 216–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.2012129

- Trott, C. D. 2021. “What Difference Does It Make? Exploring the Transformative Potential of Everyday Climate Crisis Activism by Children and Youth.” Children’s Geographies 19 (3): 300–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2020.1870663

- UNESCO. 2017. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. Paris: UNESCO publishing.

- Wahlström, M, Kocyba, P., De Vydt, M. & de Moor, J. (Eds.) 2019. “Protest for a Future: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays For Future Climate Protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European Cities. ” [https://protestinstitut.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/20190709_Protest-for-a-future_GCS-Descriptive-Report.pdf]

- Wals, A. E. 2010. “Between Knowing What is Right and Knowing That is It Wrong to Tell Others What is Right: On Relativism, Uncertainty and Democracy in Environmental and Sustainability Education.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903504099

- Walsh, L., and R. Black. 2018. “Off the Radar Democracy: Young People’s Alternative Acts of Citizenship in Australia.” In Young People Re-Generating Politics in Times of Crises, 217–232). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Wiek, A., L. Withycombe, and C. L. Redman. 2011. “Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development.” Sustainability Science 6 (2): 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6

- Willamo, R., L. Helenius, C. Holmström, L. Haapanen, V. Sandström, E. Huotari, K. Kaarre, et al. 2018. “Learning How to Understand Complexity and Deal with Sustainability Challenges–A Framework for a Comprehensive Approach and Its Application in University Education.” Ecological Modelling 370: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2017.12.011

Appendix A.

Adaptation process of the measuring instruments

To translate the measures, we followed the approach outlined by Douglas and Craig (Citation2007) which better acknowledges the issue of conceptual equivalence compared to direct back translation. Initially three independent researchers translated the items, after which reconciliation was done together with a fourth independent reviewer. Environmental actions (Alisat and Riemer Citation2015) were modified to address sustainability issues in general. Some of the items needed to be updated and adjusted to Finnish context. For example, since forests cover more than 75% of the land area of Finland and forests are mostly under commercial use, ‘planting trees’ (item 17 in the Environmental Action Scale) is probably more associated with forestry activities than nature conservation, and thus the item was rephrased.

Table A1. Self-Perceived Action competence for sustainability (Olsson et al. Citation2020) and Finnish translation.

Next, the translated instruments were tested with different young people, including pupils from a comprehensive school (n = 9, aged 14–15), upper secondary school students (n = 10, aged 16–18), young environmental activists (n = 25, age not specified) and members from an environmental NGO for youth (n = 7). Based on the testers’ feedback, the items were further developed and refined. The final versions of the measures are compiled in .

Table A2. Items for measuring sustainability actions, adapted from Alisat and Riemer (Citation2015) Environmental Action Scale.

Table A3. Items for measuring sustainability behaviors, or personal practices.

The following description of sustainability was provided to the participants at the beginning of the survey:

Sustainable development or sustainability refers to the shared goal of securing the prospects for a good life for both current and future generations. In 2015 the United Nations, including Finland, committed to common sustainable development goals. These included, for example, the goals of ending poverty, ensuring healthy lives for everyone, reducing inequalities, taking action to combat climate change, and protecting biodiversity both on land and water. Sustainable development acknowledges that all human activity has impacts on the wellbeing of both nature and society.

Appendix B.

Data screening

To detect careless and/or dishonest survey respondents, we followed the ‘multiple hurdles’ approach discussed by Curran (Citation2016), and utilized the ‘careless’ package in R. First, we calculated the standard deviation of responses across a set of consecutive item responses for each individual (Individual Response Variability Index; Dunn et al. Citation2018), and flagged respondents who scored less than two standard deviations below the mean index. Visually inspecting these cases (n = 31) revealed invariant response patterns throughout the survey (‘straightlining’ or minor deviations from it), and they were consequently removed.

Second, we calculated within-person correlations across positively correlated (>.50) item pairs and assigned items to the pair with the largest correlation (Meade and Craig Citation2012), resulting in 15 psychometric synonym pairs. Flagging participants with negative within person correlations (n = 65), we visually inspected them and removed cases with a difference of more than two units in a synonym pair (nremoved=32).

Third, we used Mahalanobis distance on a strict confidence level (.9999) to flag potential outliers (Curran Citation2016). 64 flagged cases were inspected carefully, and seven demonstrated unengaged, systematic response patterns (e.g. 5 − 4 − 3 − 2 – 3 – 4 – 5) which were consequently removed. All in all, 69 cases were defined as low quality respondents.

Appendix C.

Respecifying the measurement model

Along the process of testing measurement models, we made several re-specifications. Two behavior-items (WalkCycle and SortWaste) had relatively low factor loadings, and their correlation residuals with sustainability actions items were markedly negative, implying that the model highly overpredicts their relationship. We suspected that the reason for this was that cycling and waste sorting are already so common practice that they don’t discriminate environmentally oriented people from others. Indeed, these items had the highest means within the action and behavior constructs. Considering this, and because these items contributed a significant amount of badness of fit to the model, WalkCycle and SortWaste were dropped from further analysis.

In turn, item UrgeAvoid from sustainability action scale had several highly positive correlation residuals with behavior items and, accordingly, modifications indices suggested that this item should measure sustainability behaviors. Instead of specifying a complex indicator, we decided to drop this item as well. Furthermore, four additional error covariances were specified for item-pairs that were conceptually similar (ParRally–OrgRally; OrgRally–OrgEvent; ParGroup–ContactOffcl; Fix2ndHand–BuyLess).

Two items from action competence’s subscales were also suspected of misspecification. Item COI3 had negative correlation residuals with nearly all KAP and WTA items, and modification indices suggested that COI3 should be negatively associated with KAP and WTA scales. This seemed to contradict the theory of action competence, and thus we removed the item. In addition, item COI4 had positive correlations residuals with WTA items, implying that the model underpredicts their relationship. However, we found no theoretical reason to respecify these associations, and since global fit was acceptable, no further adjustments to these scales were made.

Global fit indices of the full measurement model are shown in , and standardized factor loadings are compiled in . Considering the large sample size and overall good measurement quality in terms of factor loadings and reliabilities, we interpret that the measurement model fits quite well to the data. The WLSMV estimator tends to produce higher factor loadings and stronger correlations amongst latent variables than MLM.

Table C1. Global fit statistics of the measurement model.

Table C2. Standardized loadings of the full measurement model (MLM | WLSMV).