ABSTRACT

The study investigates the impact of adopting mechanized processing of cassava on farmers’ production efficiency in Uganda. A stochastic production function, using translog functional form, was used to compare efficiency measures of farmers in mechanized cassava-processing villages compared with the farmers in nonmechanized cassava-processing villages in 2014. Given the specification of the translog production function, the mean technical efficiencies of the farmers were 0.69 and 0.52 in mechanized and nonmechanized villages, respectively. The significant determinants of technical inefficiency among the respondents are farming experience, education, membership of farmer association, access to markets, sale of cassava to processors and farmers who planted cassava as sole crop are all negative, which confirm to a priori expectations and significant at different levels. The policy implication of the study is that mechanization of cassava processing, particularly if done at the right scale, could create demand that can transform primary production for increased yields, higher incomes and production efficiency of smallholder farmers who constitute a significant proportion of Uganda’s agricultural sector.

I. Introduction

Cassava is an important rural food for communities in Uganda. It has tolerance to poor soils and resistance to drought, a cheap and reliable source of food that fits well into the food security strategy of smallholders (Nweke, Spencer, and Lynam Citation2004; FAO Citation2003). Cassava has, therefore, served many times as food of last resort to ameliorate the effect of food deficits which occur from erratic weather conditions and reduce the yields of cereals.

The main response to the shortage of food production in developing countries has been to invest in increased food production. Many years of investment in crop production technologies have generated a great number of innovative technologies for crop production and protection. However, the food crisis in Africa has persisted (Rusike et al. Citation2010).

In the last decade, the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture and national research institutions introduced and promoted an extensive range of processing technologies that allows farmers to harvest and process cassava into shelf-stable value-added products. The adoption of these simple, mechanized postharvest processing steps (such as grating, chipping and pressing) and technologies such as the production of high-quality cassava flour and cassava chips were expected to increase the demand for fresh cassava in the rural areas. In addition, they could enhance farmers’ willingness to adopt improved production technologies, particularly new varieties, fertilizer and improved farming practices, which can increase cassava productivity and expand production.

After 10 years of intervention in the region’s cassava subsector, this study was conducted to examine the impact of adoption of mechanized postharvest cassava-processing technologies as it affects smallholder farmers’ efficiency in cassava production in Uganda.

II. Study area and sample selection

The survey was carried out in 10 villages each where mechanical methods of cassava processing were introduced or used (mechanized-processing villages) and communities where mechanical methods of cassava processing were not used (nonmechanized-processing villages). The study villages were purposively selected based on whether or not mechanized processing of cassava was introduced. The nonmechanized villages served as counterfactuals. Records from the National Agricultural Research Organization of Uganda suggest that all the survey villages had received planting materials of high-yielding disease-resistant cassava varieties at various periods during the 1980s–2000s (MAAIF 2011).

A multistage sampling technique was used to select respondents for the study. For the villages where mechanical processing methods were introduced, 412 processors and 420 cassava farmers were randomly selected from both the mechanized- and nonmechanized-processing villages.

III. The stochastic frontier model for Uganda cassava farmers

The stochastic production frontier model by Parikh and Shah (Citation1994), which in turn derives from the composed error model of Aigner, Lovell, and Schmidt (Citation1977), Meeusen and van den Broeck (Citation1977) and Forsund, Knox Lovell, and Peter (Citation1980), was used to examine the impact of cassava-processing technologies on farmers’ efficiency in cassava production, following similar efficiency studies by Fakayode et al. (Citation2008), Ogundari, Amos, and Okoruwa (Citation2012) and Girei et al. Citation2014). This was done by comparing the efficiency measures of farmers that are located in mechanized-processing villages with farmers in nonmechanized villages.

The empirical stochastic frontier production model with translog functional form is specified as follows:

where ln represents logarithm to base e; subscripts ij refer to the jth observation of the ith farmer; Y is the gross margin from cassava production (valued in Uganda shillings) for the ith farmer; X1 represents farm size (in hectares); X2 represents cassava cuttings (in kilogram); X3 represents fertilizer used (in kilogram); X4 represents family labour used (in man days); X5 represents hired labour used (valued in Uganda shillings); X6 represents tractor services (valued in Uganda shillings).

It is assumed that the technical inefficiency effects are independently distributed and υij arises by truncation at zero at normal distribution with mean υij and variances σ2 where υij is defined by Equation (2):

where υij represents the technical efficiency of the ith farmer; Z1 denotes years of farming experience of the ith farmers; Z2 denotes years of formal education; Z3 is a dummy variable scored 1 if farmer belongs to farmers’ association and zero otherwise; Z4 is a dummy variable scored 1 if farmer uses improved cassava cutting and zero otherwise; Z5 is a dummy variable scored 1 if farmer has access to markets and zero otherwise; Z6 is a dummy variable scored 1 if farmer uses mechanized cassava-processing technology and zero otherwise; Z7 is dummy variable score 1 if farmer has access to credit and zero otherwise, Z8 is a dummy variable scored 1 if farmer has off-farm income and zero otherwise; Z9 is a dummy variable scored 1 if farmer sells cassava to processors and zero otherwise and Z10 is a dummy variable scored 1 if farmer plants cassava as a sole crop and zero otherwise. The maximum likelihood of the estimates of β and δ coefficients in Equations (1) and (2), respectively, are estimated simultaneously using the computer program FRONTIER 4.1c in which the variance parameters are expressed in terms of and

(Coelli Citation1996).

IV. Empirical results and discussions

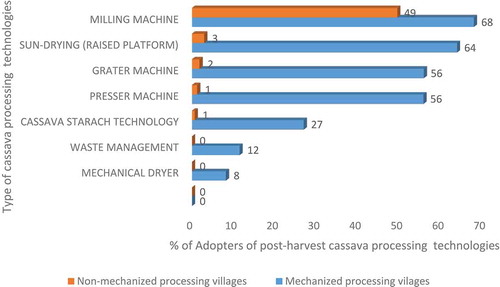

Adoption rates of mechanized-processing technologies

The proportion of processors that adopted the respective postharvest cassava-processing technologies in mechanized and nonmechanized villages is presented in . Most of the adopters of the different processing technologies are located in the mechanized-processing (or intervention) villages. The technology that was adopted most was the mechanical milling with 68% and 49% mean adoption rates in mechanized- and nonmechanized-processing villages, respectively. Others are sun drying of cassava on raised platform with 68% and 3% mean adoption rates in mechanized- and nonmechanized-processing villages, respectively; mechanical graters and pressers were each adopted by 56% of the processors in mechanized-processing villages; cassava starch technology, waste management technique and mechanical dryer were 27%, 12% and 8%, respectively, in the mechanized-processing villages.

Determinants of farmers’ production efficiency

Given the specification of the translog production function, the mean technical efficiencies of the farmers were 0.69 and 0.52 for farmers in mechanized and nonmechanized villages, respectively. The tranlog maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) estimates and inefficiency effects results are presented in .

Table 1. Translog MLE estimates and inefficiency effect.

Given the specification of the translog model, the estimate of the sigma-squared (σ2) is statistically significant at 1%, thus indicating a good fit and correctness of the specified assumptions of the composite error term. The variance output (γ) is estimated to be 0.88, suggesting that more than 80% of the variation in output among farms is due to differences in technical efficiency.

The generalized likelihood ratio is significant at 0.01 level, suggesting the presence of the one-sided error component. This means technical efficiency is significant and a classical regression model of production function based on ordinary least square estimation technique would be an inadequate representation of the data. Thus, the results of the diagnostic statistics confirm the relevance of stochastic frontier production function using maximum likelihood estimator.

The estimated coefficient for farm size is positive, which conform to a priori expectation, and significant at 1%. The magnitude of the coefficient of land, which is 1.18, indicates that margin in cassava production is elastic to changes in the level of cultivated land area. This suggests that land is a significant factor associated with changes in cassava output.

The production elasticity with respect to fertilizer is positive as expected and statistically significant at 10% level. The magnitude of the coefficient of fertilizer, which is 0.56, indicates that farm gross margin in cassava production is inelastic to changes in the level of chemical fertilizer used. Thus, 1% increase in inorganic fertilizer use would induce an increase of 0.56% in the farm gross margin and vice versa. The significance of the fertilizer variable derives from the fact that fertilizer is a major land-augmenting input in the sense that it improves the productivity of existing land by increasing crop yields per hectare.

The production elasticity with respect to hired labour and tractor services is negative and statistically significant at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively. This suggests that a 1% increase in hired labour and use of tractor services each would, respectively, cause a decrease of 0.56% and 0.29%in the cassava gross margin and vice versa. This negative sign, though unexpected, is plausible given the fact that the farmers cultivated small land area, mostly less than 2 ha, which makes it economically unviable to engage the services of hired labour and tractor services.

The sources of inefficiency are examined by using the estimated δ-coefficients associated with the variables in Equation (2). The estimated coefficients of farming experience, education, membership of farmer association, access to markets, sale of cassava to processors and farmers who planted cassava as sole crop are all negative, which confirm to a priori expectations and significant at different levels. This implies that farming experience, education, membership of farmer association, access to markets, sale of cassava to processors and planting cassava as sole crop are significant determinants of technical inefficiency among the respondents. The negative coefficients of these variables imply that an increase in any of or all of these variables would lead to decline in the level of technical inefficiency, suggesting that these variables have positive influences on technical efficiency in cassava production among the respondents. In other words, cassava farmers with better education and farming experience belong to farmers’ association and who relatively had access to markets, sold cassava to processors and who planted cassava as sole crop achieved higher levels of technical efficiency in cassava production in Uganda.

V. Conclusion

The mechanized cassava-processing activities motivated efficient management of resource utilization in cassava production among farmers in the intervention villages by facilitating improvement in their production efficiency through greater access to markets and sales of cassava roots to mechanized processors. This has enhanced the efficiency of resource utilization in cassava production among the farmers. Consequently, many of the cassava farmers in the mechanized-processing villages were brought closer to their production frontier, thereby greatly enhancing profit.

The study recommends that there should be an increased promotion of postharvest technologies that can help processors engage in mechanical processing of crops, especially highly perishable crops such as cassava. The adoption of postharvest technologies stimulates increased demand for fresh cassava roots for processing, which in turn had positive impact on farmers’ production efficiency through increased access to markets.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aigner, D., C. A. K. Lovell, and P. Schmidt. 1977. “Formulation and Estimation of Stochastic Frontier Production Models.” Journal of Econometrics 6: 21–37. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(77)90052-5.

- Coelli, T. J.; A guide to FRONTIER version 4.1c. 1996. A Computer Program for Stochastic Frontier Production and Cost Function Estimation. Armidale, Australia: working paper in the Department of Econometrics, University of New England.

- Fakayode, S. B., R. O. Babatunde, and A. Rasheed. 2008. “Productivity Analysis of Cassava-Based Systems in the Guinea Savannah: Case-Study of Kwara State Nigeria.” American-Eurasian Journal of Scientific Research 3 (1): 33–39. www.idosi.org/aejsr/3(1)08/7.pdf

- FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization). 2003. Food and Agricultural Organization: Agriculture, Food and Nutrition for Africa: A Resource Book for Teachers of Agriculture, 202–207. Rome: Publishing Management Group, FAO information Division, FAO of the United Nations.

- Forsund, R., C. A. Knox Lovell, and S. Peter. 1980. “A Survey of Frontier Production Functions and of their Relationship to Efficiency Measurement.” Journal of Econometrics 13 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(80)90040-8.

- Girei, A. A., B. Dire, R. M. Yuguda, and M. Salihu. 2014. “Analysis of Productivity and Technical Efficiency of Cassava Production in Ardo-Kola and Gassol Local Government Areas of Taraba State, Nigeria.” Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 3 (1): 1–5. doi:10.11648/j.aff.20140301.11.

- Meeusen, W., and J. van den Broeck. 1977. “Efficiency Estimation from Cobb-Douglas Production Functions with Composed Error.” International Economic Review 18: 435–444. doi:10.2307/2525757.

- Ministry of Agriculture Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF) Uganda Agriculture Sector Performance Report. Accessed 10 August 2015. http://www.agriculture.go.ug/userfiles/Agriculture Sector Performance FY202011-12

- Nweke, F. I., D. S. C. Spencer, and J. K. Lynam. 2004. The Cassava Transformation: Africa’s Best-Kept Secret. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

- Ogundari, K., T. T. Amos, and V. O. Okoruwa. 2012. “A Review of Nigerian Agricultural Production Efficiency Literature, 1999–2011: What Does One Learn from Frontier Studies?” African Development Review 24 (1): 93–106. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8268.2011.00307.x.

- Parikh, A., and K. Shah. 1994. “Measurement of Technical Efficiency in the Northwest Frontier Province of Pakistan”.” Journal of Agricultural Economics 45 (1): 132–138. doi:10.1111/jage.1994.45.issue-1.

- Rusike, J., N. M. Mahungu, S. Jumbo, V. S. Sandifolo, and G. Malindi. 2010. “Estimating Impact of Cassava Research for Development Approach on Productivity, Uptake and Food Security in Malawi.” Food Policy 35: 98–111. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2009.10.004.