ABSTRACT

The World Heritage Site of Petra in Jordan is a large and complex site to manage with its multiple stakeholders, governance complexities, and competing local interests. It has been subjected to numerous management plans, none of which were fully implemented. In developing a new Integrated Management Plan one of the biggest challenges was to develop a methodology that would allow all voices to be heard, various interests brought together, and local ownership of the plan’s objectives achieved. This paper reflects on the practical experience of a novel approach to management planning at a cultural heritage site which draws on the theories and practices of participatory planning and natural environment management, and combines top-down and bottom-up approaches through collaboration with local entities and stakeholders. Utilising local institutional resources, in an approach that is locally driven and externally facilitated, the resulting Integrated Management Plan exemplifies a process of co-creation of management decisions.

Introduction

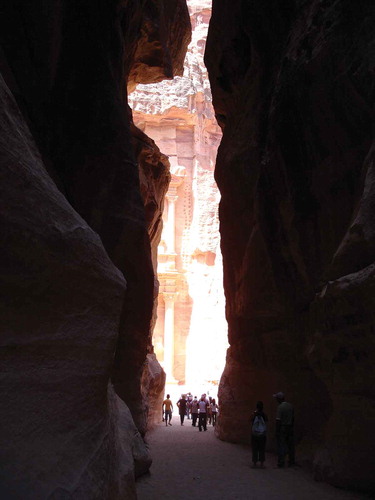

Petra, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1985, is a site of world renown and a globally recognised brand and destination. The site, however, is all too often epitomised in the glimpse of the Treasury building captured through a gap in the Siq, the passageway that leads most visitors (and Indiana Jones in the 1989 film) to the site (). This romantic vision continues to be played out in much of the travel literature alongside romanticised descriptions that use references like the ‘red rose’ or ‘lost’ city. It is this allure that is utmost in most visitors’ minds and explicitly drives the visitor experience.

In reality, Petra is a large and complex ecosystem of multiple historic layers ranging from the Palaeolithic to the later Islamic period, geographical formations, and biodiversity. It is one of the largest cultural World Heritage Sites at 264 square kilometres, and home to six different and distinct communities. Petra also plays an increasingly important role in defining Jordanian identity (Rababe’h Citation2010). It is of both universal and local significance, but also of national importance as it is the key attraction in Jordan’s largely cultural heritage-led tourism economy and therefore a major economic contributor. In a broader region that is politically volatile, this economic dependence on tourism also carries with it an element of precariousness, especially for the local communities that are increasingly dependent on it.

The ‘bucket list’ nature and the unarguable ‘wow’ factor of visiting Petra means that visitors are often all too happy to overlook much of its shortcomings as a visitor experience. This, however, does not diminish the need to significantly improve site management, not least to secure the future protection of the site. The combined threats of population growth and development pressure, potential impacts of climate change and rising visitor numbers add to this urgency. Other factors identified as high risk are frequent flash floods and associated landslides and rock falls (Paolini et al. Citation2012; Cesaro and Delmonaco Citation2017).

The foremost concern of the State Party and UNESCO are to secure the future of the World Heritage Site, by reducing risks and introducing sustainable management practices. In addition, UNESCO goals include adherence to the UN Sustainable Development Goals and a commitment to build local institutional capacity and ensure local commitment to the management plan and its implementation. Numerous studies on the site, from highly scientific hydrogeological studies and archaeological research to ethnographic studies with local communities, urban planning and tourism assessments provide a valuable resource of baseline data, but simultaneously present a challenge for integrating all the various types of data and value assessments. The purpose of this paper is to report on the management planning methodology that was trialled at Petra by the UNESCO Amman Office, place it in its interdisciplinary and theoretical context and finally reflect on the experience and the outcomes. The Integrated Management Plan was a joint initiative of the UNESCO Amman Office, the Department of Antiquities of Jordan and the Petra Development and Tourism Region Authority and was funded by UNESCO (UNESCO Amman Office Citation2019). Both authors acted as coordinators of the process from inception and methodological design through to implementation, approval and hand-over.

Petra World Heritage Site

Petra was inscribed as a World Heritage Site (WHS) in 1985 as an outstanding testimony to the Nabataean civilisation. The site is recognised for its significant corpus of rock-cut tombs, sophisticated water engineering and management systems including channels, dams, and cisterns; temples, churches and public buildings of the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Early Islamic periods, as well as archaeological remains of Neolithic and Iron Age settlements and evidence of copper mining (UNESCO Citation1994). The archaeological remains are set in a vast landscape, that is itself recognised for its biodiversity and rich ecology, including endemic species (UN Habitat Citation2014).

Following the recommendations of the 1994 Management Plan (UNESCO Citation1994), the Petra Archaeological Park (PAP) was established in 2007. In 2009, the Petra Development and Tourism Regional Authority (PDTRA) was formed as an independent authority covering the wider region around the site and incorporating the PAP within its management structure. The antiquities within the site are protected by Jordan’s Antiquities Law and overseen by the Department of Antiquities (DoA). The DoA is responsible for monitoring excavations and restoration projects. This double institutional structure can at times create instances of decision-making conflicts. Petra has been attracting tourists since the 1920s, but it is only since 2000 that numbers have grown significantly, exceeding a million visitors per year in bumper years. Consequently, the local economy has increasingly come to depend on tourism which is also the source of formal and informal employment for much of the local population. The high dependence on tourism and the general volatility of the region is another cause for concern.

The new Integrated Management Plan (IMP) for Petra was coordinated by the UNESCO Amman Office on the behest of and in collaboration with the Jordan Department of Antiquities and the PDTRA, specifically to tackle a wide range of issues afflicting the site. For UNESCO, it was paramount that the methodological approach to preparing IMP had to establish ways in which the complex elements could be broken down into manageable components while maintaining relational links and generating opportunities for integration across areas of operation, different disciplines and at times conflicting priorities.

Petra as a Complex Site

Much of the reason behind seeking an alternative and more nuanced methodology for the IMP was the recognition of Petra as a complex site (Comer Citation2012). This complexity stems from its size, its mixed cultural and natural characteristics – although recognised by UNESCO as a cultural site – its multiple facets (social, economic, cultural, geologic, touristic) and the multiple players and interest groups that rely or benefit from the site. Recognising and understanding the full complexity of a site and the existing relationships among its various stakeholders needs to precede any plans for the future of the site (Borges et al. Citation2011, 11).

Complexity is already recognised as a key characteristic that needs to be addressed in natural environment management (Collins and Ison Citation2009) and urban planning (Healey Citation2007). In the case of urban planning, this complexity is borne out of the multiplicity and dynamic nature of relations, often rendering existing hierarchical models redundant (Healey Citation2007). In social sciences, social systems are commonly described as complex as the impacts or implications of actions are rarely predictable. In all fields, complexity is closely linked to conditions of uncertainty and fluidity. These are clearly evident at Petra through dependencies on a complex ecological system, regularly evolving governance structures and a fragile social environment (see for example Bienkowski Citation1985; Burtenshaw et al. Citation2019).

Ecologically, Petra is located at a crossing point of three zoogeographic zones which results in a unique and heterogeneous ecosystem (Akrawi Citation2000). Overlying this ecosystem is a multiple-centred decision-making and governance structure that includes regional territorial planning, tourism and associated infrastructure development, urban planning and investment-centred urban growth approaches, natural area protection, local social and economic development initiatives; competing demands for access to resources from local, national and international players and a national defence structure necessitated by the geopolitical position of Jordan and the site itself.

Not only is Petra a large archaeological zone/park but some of the greatest impacts on the World Heritage Site emanate from external factors beyond the boundaries of the site. Located in the base of a valley, the site is subject to regular flash flooding from a wide catchment area, including a watershed that falls outside of the administrative boundaries of PDTRA, the local authority (Al-Weshah and El-Khoury Citation1999). On the immediate boundaries of the site are six settlements, several of which are rapidly expanding. Two of the settlements, Wadi Musa and Umm Sayhoun are linked to access and exit routes to and from the site. Wadi Musa has expanded through growing numbers of tourism services, natural population growth, and demand for housing. Umm Sayhoun, originally constructed to house the B’dul community who were moved out of the site in the 1980s, is no longer fit for purpose for its rapidly increasing population and restrictions on expansion due to its close proximity to the WHS.

Petra is thus simultaneously mature and precarious. Many years of excavation and research have generated a substantial body of knowledge on the site, yet the daily management of the site is compromised by regular organisational change in administrative and decision-making structures. This is compounded by the site’s location on the geographical and political/administrative margins of mainstream and centralised decision-making bodies that are located in the capital Amman, and a limited pool of talent from which to attract a competent workforce to respond to the site’s wide-ranging needs.

Traditionally, archaeological park management has built on national park and nature conservation approaches (Pedersen Citation2002). A previous management plan for Petra for example was prepared by the US National Parks Service (2000) reflecting their own management model and subsequently leading to the establishment of a Petra Archaeological Park authority in 2009. In the case of the current IMP participatory planning methodologies adapted from urban planning were seen to be more appropriate tools in addressing the multiplicity of issues and complex network of players.

Rethinking Management Plan Methodologies

It is now commonly accepted that the care and management of the cultural heritage for the appreciation and benefit of all is best served through a management plan that integrates the wide range of concerns for the site (Feilden and Jokilehto Citation1993; Hall and McArthur Citation1998; Pearson and Sullivan Citation1999). A management plan is a practical operational guide for a cultural heritage site that will provide the means for establishing an appropriate balance between the needs of cultural and natural resources, conservation, tourism, access, sustainable economic development and the interests of the local community (Sullivan Citation1997). A management plan is also a policy framework that provides the necessary indicators to enable decision makers to efficiently and effectively respond to change (Ringbeck Citation2007). In the World Heritage Sites Operational Guidelines, UNESCO stipulates that each nominated property ‘should have an appropriate management plan or other documented management system which must specify how the Outstanding Universal Value of a property should be preserved’ (UNESCO Citation2017, 31). The Operational Guidelines further recommend that any management system is ‘integrated’ and preferably undertaken ‘through participatory means’ (UNESCO Citation2017).

However, in practice, a management plan can all too often be treated as an end product, a glossy published volume that is rarely acted upon. This has also been the experience for Petra with a legacy of management plans dating back to 1968. The shortcomings of the various management plans are succinctly summarised by Akrawi (Citation2000, Citation2002). None of the previous plans had been properly endorsed by the authorities responsible for their implementation; and tellingly in many cases key players had not been sufficiently engaged or been given the opportunity to provide input during the preparation of the plans. Implementation has also been hampered by overlapping responsibilities among key players, arms-length management from Amman and lack of staff and capacity to effectively manage the site on the ground (Akrawi Citation2000).

Through a preliminary phase of a ‘Road Map’ an overview of the current situation and an evaluation of previous management plans was undertaken and followed up with meetings and interviews with a wide range of stakeholders. These assisted in defining the need to establish a process and a methodology that could be carried through beyond the point of endorsement of a singular ‘bound-in-time’ management plan to one which is flexible and adaptable as needs change, problems are solved and others surface. The design of a participatory methodology to achieve the agreed aims emerged from this phase, which also identified five key principles that would guide the process:

Principle 1: Management planning would be treated as a process rather than a product.

Principle 2: The process would be participatory and based around engagement with a wide range of actors.

Principle 3: The management plan would be action oriented and environment/context specific.

Principle 4: The management plan would need to work across scales (governance and spatial).

Principle 5: Outcomes would be integrated so as to deliver joined up solutions that considered cultural, natural and social dimensions together.

In the following sections, we describe how a process centred approach (Principle 1) with participation at its heart (Principle 2) was designed and implemented.

Principle 1: Conceiving the Management Plan as a Process

The process of preparing a management plan is as important as the completed plan. This enables the multidisciplinary team to work together, benefit from one another’s experiences and negotiate conflicting issues or demands (Orbaşlı Citation2007). A sufficiently long interactive consultation period allows for decisions to be evaluated, responsibilities for implementation to be established and most significantly ensures that the management plan is established within the community of people who will be responsible for its implementation. Some of the major decisions taken during the planning process can begin to be implemented or acted on before the final version of the approved plan is published. In a study of management practices at six UK World Heritage Sites, Landorf (Citation2009) concluded that sustainable heritage practices were largely dependent on a long-term and holistic planning process which incorporates the participation of multiple stakeholders. In the case of Petra, the Road Map phase had clearly established the complexity of the physical and social relationships of the site and the various players engaged with it.

There has also been criticism of expert-led approaches in planning, regulation, policy, and management fields that pay scant attention to local ecologies and fail to properly understand a place and its communities (Smith Citation2015). Therefore, it was important to create an environment that allowed experts to work with the groups in the organisations responsible for the site and the local community to understand their concerns and capacities and to deliver tailored and appropriate solutions. It was also critical that institutional backing from the Petra Development and Tourism Regional Authority (PDTRA), the Department of Antiquities in Jordan (DoA), and the UNESCO Amman Office was secured, and a commitment made to participate in the management planning process and to support the implementation of the outcomes. The first step of the collaboration was the establishment of a core team (hereafter called the ‘technical team’) that would be instrumental to the delivery of the integrated management plan from the two partner institutions PDTRA and the DoA. The technical team, supported by UNESCO, were fully involved in managing an 18-month participatory process that led to the production and delivery of the Integrated Management Plan.

The resulting IMP is also seen as a framework which can be changed and adapted as conditions change. None of the stages of preparing a management plan are mutually exclusive and can be, in full or in part, repeated as site conditions change or new information becomes available. Review and re-evaluation need to be integral to each stage and also during implementation. This need for flexibility can however conflict with institutional structures and regulatory mechanism necessitating the formal approval process of a ‘signed-off’ management plan. Furthermore, the complexity of the approval process inevitably restricts revisions to set time intervals.

Principle 2: Designing and Implementing a Participatory Process

One of the first tasks of the technical team was the identification and mapping of the stakeholders. Stakeholder mapping practices are well established and were based on internationally recognised methodologies and tested practices in identifying and then categorising stakeholders (see for example Bryson Citation2004 and https://www.iap2.org/mpage/Home). Based on a matrix produced by Mendelow in 1981, these typically order stakeholders according to their influence or power on decisions regarding the site, and interest which refers to the impact the given party has through decision-making and actions on the site and/or is impacted (affected) by decisions concerning the site (Scholes Citation2001). Although the stakeholder analysis proved to be a useful tool in identifying stakeholders, in view of the complex and interdependent nature of the site and of the issues being faced, it became apparent that stakeholder mapping alone would not suffice in informing consultation and engagement practices. The stakeholders would also need to be consulted in ways that would enable them to genuinely participate in the process in an environment that was culturally and professionally appropriate.

The method of engagement therefore centred around the principles of social learning as it could be instrumental in guiding the convergence of goals and knowledge, co-creation of knowledge and change of behaviour as a result (Collins and Ison Citation2009). Social learning is promoted in environmental management as it is seen as a means of operating within the complexity of the field, and has the potential to stimulate collective action, or in the very least can generate outcomes such as acquiring new skills and knowledge, developing trust, and forging new relationships (Muro and Jeffrey Citation2008). Social learning in participatory planning is supported by the theory that engaging with others that are outside of an immediate circle (communities of practice) generates environments of learning whereby such interactions increase instances of learning. However, it is also recognised that participants may not have shared values or objectives (towards the environment) and that participation alone will not lead to the behavioural change that is being sought (Fainstein Citation2000).

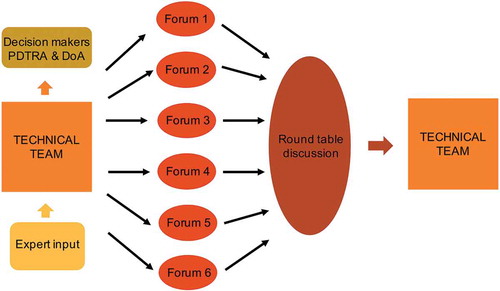

The stakeholder engagement model for the IMP was adapted from a stakeholder forum structure first pioneered in the Germany City of Ulm and Deutsche Bahn in 2011 around the redevelopment of its railway station. Serving as a ‘permanent interaction with stakeholders and local society’ the approach was hailed as being ‘instrumental in bringing new ideas into the planning process’ (Stein Citation2015). A simpler model of the methodology was adopted by the City of Regensburg in the preparation of the management plan for the World Heritage City (City of Regensburg Citation2012). This model facilitates consultation to become a process of collaboration and co-creation ().

Figure 2. The consultation process (adapted from a model developed by the City of Ulm and Deutsche Bahn in 2011) (source: redrawn from Petra WHS Integrated Management Plan)

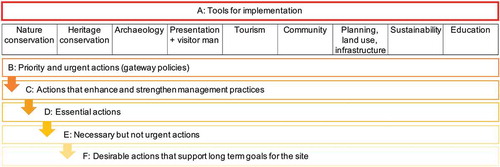

In order to reach as many stakeholders as possible, and to do so effectively, thematic groups, referred to as ‘forum’, were established to advise on various aspects of site management. Membership of the groups were from stakeholders identified as having some influence and notable impact on the site and/or those being impacted by developments concerning the site, alongside those drawn from wider interest groups. The thematic categories for the groups are given in .

Table 1. The thematic forum groups (source: Petra WHS Integrated Management Plan)

Each forum was initially formed on the basis of the stakeholder mapping exercise but was broadened during the process to respond to needs and recommendations. Where appropriate or informative, outside experts from the public, private, or NGO sector were included in a group or invited to a specific meeting to make a presentation and share experiences. By focusing on a specific subject area or interest group, each forum became a platform that enabled in-depth discussions around the subject through the input of multiple experts and representatives of interest groups. Small group meetings are also favoured in the context of social learning (Muro and Jeffrey Citation2008) and ‘it is in the process of participation that the nature of the policy issue is determined’ (Collins and Ison Citation2009, 362). The experience of the City of Ulm Railway project from which this methodology was adapted, was that an integrated perspective could be ensured ‘by engaging groups representing specific interests, operating as focused think tanks and channelling ideas, information (even critical feedback/objection) to the steering group’ (Stein Citation2015).

Although a European urban planning project provided the model for the framework, the forum structure and meeting environment and protocols were adapted to the Jordanian social and cultural contexts. Most notable was the varying nature of the different forum meetings held among professional groups, local business representatives or representatives of local community groups. While meetings with professionals might follow a largely universal format, building trust with other players, especially those traditionally excluded from governance mechanisms, required culturally sensitive approaches. For example, in the community forum, the presence or absence of key authority figures was carefully coordinated, with them attending meetings when assurances needed to be provided but absenting themselves to allow participants to voice thoughts and concerns more freely.

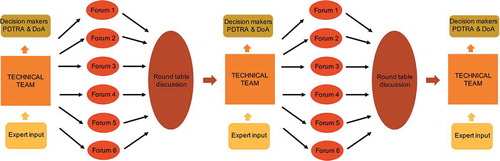

Through the process, forum members were invited to provide input to and critically evaluate information being produced by the coordinators and technical team; identify further sources of information and expertise that could be accessed; and where relevant, identify roles and responsibilities for their own organisations/communities. Each forum was chaired by an established practitioner or academic in the field, often with an arms-length involvement in the management of Petra. It was important that the chairperson could be trusted by all members of the forum and could effectively oversee discussions and assist the group in reaching a consensus at the end of a meeting where this became necessary (Richardson and Connelly Citation2005). Muro and Jeffrey (Citation2008) also emphasise the importance of facilitation and repeat meetings to improve and open up communication within a group ().

Figure 3. The process is repeated as many times as necessary and can also serve as an advisory mechanism when the management plan is being implemented (source: redrawn from Petra WHS Integrated Management Plan)

At each meeting participants were presented with specific tasks/questions to discuss and formulate responses to. The process was repeated seven times in total with several of the forums having additional meetings. The cyclical process helped to reaffirm decisions and commitments that were being made, while each meeting could be focused on a specific task. As the management plan developed these included:

A review of baseline data and identification of further sources of information concerning the subject focus of the group;

A reflection on the site’s values from a disciplinary and/or social perspective of the group;

An evaluation of what works at the site and ways in which initiatives can be built upon going forward;

A critical review of issues and constraints that hinder the effective management of the site and the protection of the Outstanding Universal Value;

Identification of key issues that have high-risk implications, and prioritisation (ranking) of issues related to their own area of expertise or interest;

Feedback on management policies and recommendations as they emerged in order of priority.

At the conclusion of each cycle of meetings, the chairpersons represented their forum at a round-table discussion. The round-table meeting, also attended by members of the Steering Committee, enabled different interest groups to discuss cross-cutting issues and reach a consensus. The outcomes of the round-table helped inform the next stage of the management plan, with any critical issues arising being discussed by the Steering Committee. The Steering Committee remained the ultimate decision-making body but was clearly informed by the advice received through the round-table discussions. This meeting structure also introduced a previously not experienced level of transparency to the decision-making process.

There are inevitable overlaps between the areas of interest of the groups and several individuals served on more than one forum. This, alongside the presence of the coordinating and technical team members attending all the meetings maintained lines of communication across the groups. Where there was a definite overlap of interests two or more groups held joint meetings, including site visits. For example, the archaeology and conservation groups undertook a joint site visit to view recent and ongoing projects, while the infrastructure, planning and hydrology and geology groups held a joint meeting around the issues of land use planning and flood controls, and the interpretation group held a visit to the site to analyse existing interpretation methodologies and advise on a comprehensive interpretation strategy for the site.

The process also intended to strengthen horizontal and vertical lines of communication that could be taken through to the implementation phase. Forum members were therefore encouraged to communicate emerging messages to their own communities of interest, thus broadening the debate to a wider group of participants and promoting transparency in the processes. Consultation with local communities was also absorbed into the process through a forum dedicated to community-based issues, alongside others such as education and tourism that also included strong representation from community groups. As a reflection of the breadth and depth of issues and so as to maximise representation, including by marginalised or under-representative groups, the community forum met more often than the other groups and was also supported by outreach activities and visits to community representatives and organisations by the technical team.

It is envisaged that the forum structures will be maintained in their advisory capacity during the implementation of the IMP and act as a useful sounding board at critical times in the course of future decision-making.

Principle 3: Action-Oriented Approaches/Outcomes

Management planning approaches have often advocated a vision-driven approach (see for example Feilden and Jokilehto Citation1993; Demas Citation2000). Planning theory, however, has been shifting towards more communicative approaches that take on ethical and inclusive stances, thus replacing the outcome-based positivist approaches which often-produced masterplans that worked towards an ideal that may never be realised (Fainstein Citation2000). Others have also noted that engagement practices, rather than a grand vision, are more likely to improve commitment to stewardship of heritage assets (Akerman Citation2014). Reverting to a problem-based approach more common in urban planning practice, underpinned the consultation model that enabled the management planning process to pursue an aim of reaching consensus on priorities and urgencies.

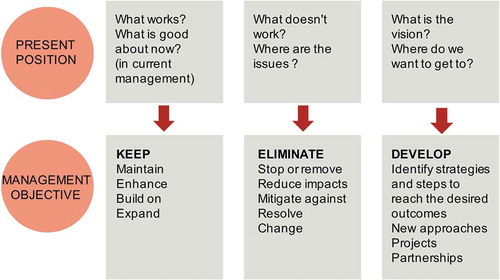

The management approach that was adopted therefore built on:

Establishing what was already working and identifying ways in which this could be built on and enhanced and/or inform other areas of operation.

Identifying what was not working or remains an issue in order to develop strategies to address the problem or reduce and mitigate its impacts ().

Figure 4. An action-led management approach (source: redrawn from Petra WHS Integrated Management Plan)

This approach shifted the process from being vision centred to focus more specifically on good practices, past achievements, and recurrent issues as its starting point of building up common ground. Only through a process of prioritisation did a shared vision for the site start to emerge among the stakeholders. One group of recommendations (Category C in ) most specifically focused on actions that would contribute to achieve these goals and aspirations and enhance the site’s values.

Principle 4: Working across Scales

Archaeological sites are rarely considered in isolation, as they are connected spatially to larger areas of physical influence and relationally through series of networks and connections. For a site, the size of Petra and the considerable external factors affecting it, management approaches needed to combine strategic frameworks (macro scale) with case/detail specific (micro scale) actions.

Spatially, to operate only within the confines of the WHS buffer zone would not suffice. In the case of World Heritage Sites, the purpose of a defined buffer zone is ‘an area surrounding the nominated property which has complementary legal and/or customary restrictions placed on its use and development to give an added layer of protection to the property’ (UNESCO Citation2017, clause 104). Many of the areas that impact on the site or have a direct influence on the site and its management are spatially beyond the buffer zone. These were considered as areas of influence and would also include areas that were influenced by the site (Turner Citation2007). The Operational Guidelines of the World Heritage Convention also emphasise that a management approach to a property has also to consider the:

broader setting, [which] may relate to the property’s topography, natural and built environment, and other elements such as infrastructure, land use patterns, spatial organization, and visual relationships. It may also include related social and cultural practices, economic processes and other intangible dimensions of heritage such as perceptions and associations. Management of the broader setting is related to its role in supporting the Outstanding Universal Value. (UNESCO Citation2017, clause 100)

In the case of Petra, many of the factors that affect the site lie outside of the site. Most notably these include population and urban growth, sprawl in the settlement areas surrounding the site, hotel and tourism development, including on the Scenic Road ridge that can be viewed from within the site, pressures on infrastructure and most importantly increasing occurrences of floods and their growing intensity. Flash floods during the rainy season are a serious risk to the safety of visitors and those working on the site and the risk factor is compounded by growing visitor numbers. Furthermore, the floods often carry debris, including construction waste that is then dumped in the site, and dislodge stones that can fall from high-level ridges and increase the presence of hazardous substances that damage the monuments.

These type of impacts by their very nature require spatially large areas of consideration including beyond the borders of the PDTRA jurisdiction, a multidisciplinary approach and strong commitments from a range of decision-making entities and agencies. It was therefore essential that these agencies were engaged in the management planning process. In many instances the purpose was to establish essential links of communication between local agencies and those operating at a larger scale, including regional and national level organisations. There is also a temporal dimension to scales linked to the time frame in which impacts will be felt and the management framework needed to consider potential long-term implications of planned actions such as the planning of urban expansion areas, new roads and infrastructure, planting and particularly the control of debris that can find their way into the site.

Principle 5: Integrated Outcomes Delivering Joined up Solutions

The integrated nature of the management plan was achieved by establishing cross-cutting issues from the start of the process and taking a trans-disciplinary approach to the process by bringing together academics and professionals from different disciplines to solve problems and creating a platform for partnership working between public organisations and NGOs. A number of cross-cutting issues, such as risk management, sustainability and education were evident from the start of the process and each addressed through a dedicated forum as well as across all the groups. For example, the risk management forum worked closely with Jordan Civil Defence and ICOMOS to develop a risk management plan, while the individual groups were made aware of risks in the context of their brief and discussed appropriate responses. This increased awareness has equipped a range of stakeholders to play a more proactive role in prevention and where appropriate more knowledgably support relief efforts in the event of catastrophic incidents. Other cross-cutting issues emerged from the process as issues were identified and prioritised in the various groups. The length of time allocated to the management planning process ensured that these issues could be addressed across disciplinary boundaries, brought to the attention of all the groups and opportunities created for joint meetings where the different disciplinary perspectives could be discussed with a view to making implementable recommendations.

Heritage is both cultural and natural and at many sites it is not possible to separate them (Kono Citation2014). The IMP clearly recognised that the vast and diverse landscape of Petra is a social ecological system and habitat, not simply a setting for antiquities; it is also a source of livelihood for some of the local communities. Building on approaches adapted for Cultural Landscape by the IUCN (Finke Citation2013), the IMP considered the cultural and natural values as plural values that are integral to one another rather than identifying a dichotomy that could lead to engaging in value trade-offs. Nonetheless, separated out protection systems, governance and laws for cultural and natural assets remains a challenge in Jordan, as it does elsewhere. The introduction of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) as guiding principles into the management framework supported cross-disciplinary approaches and proved to be a useful tool to shine a light on the work of a number of smaller NGOs and community initiatives. Cultural heritage management is integral to the delivery of the SDG and in the case of Petra, 15 of the 17 SDG were addressed through the policies and related actions of the IMP. References to the SDG also helped in maintaining a focus on systematic social inequalities that impact on site management. Sustainability, as a cross-cutting issue was considered by all the groups and is clearly reflected in the policies, including considerations of overlapping planning frameworks such as sustainable destination criteria (Global Sustainable Tourism Council Citation2017).

The Petra WHS IMP consists of a total of 94 policies grouped in and across disciplinary areas, and most notably in tiered categories based on urgency from Category A policies on management tools underpinning the implementation to the IMP, through to Category F policies supporting the future aspirations for the site. Policies are organised so as to cascade down, the resolution or implementation at each level making the implementation of the next level of policies possible. For example, Category B policies are priority actions necessary to overcome bottlenecks in the effective management of the site. These were also considered to be ‘gateway actions’, opening possibilities or generating a framework for other actions to be realised. Category C policies build on and enhance existing good practice; and Category D policies are largely concerned with improving the operational functionality of the site and its environs, once the gateway actions have been realised (). Each policy is further broken down into three to six action points linked to monitoring indicators and the identification of key risk factors arising from proposed actions, including institutional dependencies or legal barriers that could prevent actions being implemented.

The Steering Committee members were high-level decision makers who for their respective organisations were also responsible for endorsing and thereafter implementing the Integrated Management Plan. In order to enable the endorsement of the IMP, all Category A policies were actioned and ratified by the Steering Committee prior to the completion of the plan. The endorsement of the plan also required the approval of the Steering Committee and liaison with the relevant partners to implement the Category B level (gateway) policies with immediate effect. This ensured that all the legal and administrative tools pertinent to the implementation of the IMP were in place at the point of endorsement.

Evaluation and Conclusion

The Petra WHS IMP guides the PDTRA in decision-making at the site and planning future projects. To further advocate for the strategic approach of the IMP and ensure adherence to its policy framework, UNESCO Amman office implements initiatives that fall within the IMP strategic approach for the site (see current initiatives at https://en.unesco.org/fieldoffice/amman/projects). Notably, the IMP was also included as part of the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit (PMDU) tasked to support the entities among the Government of Jordan implement their strategies and short-midterm plans as outlined in the Jordan Vision 2025 (Government of Jordan Citation2014). The delivery of the IMP is also monitored by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre through periodic reporting cycles and State of Conservation reports produced by the State Party. The full impact of the IMP and its effectiveness, however, will only become apparent over time. What we can reflect on here are the tangible benefits that this process and participatory approach has delivered to date.

Foremost, it engendered collaboration among parties that had previously limited interaction, fostering new partnerships and initiatives beyond the project timeframe and remit. In participatory processes, alongside a process of learning from each other, there is also the experience of learning with each other (Muro and Jeffrey Citation2008). In Petra for some members of the groups this also included learning about participatory processes and how to interact in semi-structured group environments. However, more sustainable practices will require behavioural change which is more difficult to instigate, and social learning processes are unlikely to completely change viewpoints when there are so many (Muro and Jeffrey Citation2008). In the Petra case, individuals participated in the process for a range of different reasons (professional, personal, and institutional) and did not necessarily share a unified participation ‘goal’ or expectation of outcome. This is in itself a reflection of the complex relationship networks and interdependencies that exist among the various stakeholders.

As the process was conducted with predominantly local actors, the expertise gained over the course of the process remains in the country and those involved in the process are the same groups responsible for implementing the IMP and for training a new generation of site managers in both public sector institutions and universities. However, the isolated location of the site in relation to centres of national level decision-making or expertise (for example, the cluster of most active universities are in the north of Jordan) remains a challenge to attracting and maintaining high calibre staff and building up strong implementation teams at the site.

For some groups who often see themselves as being marginal to decision-making processes, it offered an opportunity to have a seat at the table and to be heard. As the process developed, an increasing confidence in participants also became evident. At the local level the process provided a voice to a number of groups that had not had their voice (and concerns) heard before, including local women, but also actors like local tourism businesses and providers. Their continued presence and participation at meetings also signalled a willingness to participate and demonstrated a strengthening of relations among different players. On the other end of the spectrum various national level players, such as the Jordan Green Building Council, were drawn into the process contributing fresh perspectives on sustainability as well as new partnership opportunities for specific actions and projects.

The project achieved commitment to the process from a wide range of players that can translate into commitment to delivery. Through a highly iterative process of problem evaluation it provided a level of transparency rarely seen in Jordan, and as a result increased accountability for the implementation bodies. As the process and the decision-making process that led to recommendations was shared with a large number of actors and institutions this increased their willingness to participate in the delivery.

Petra, however, remains a highly complex and fragile World Heritage Site and there are a number of challenges that cannot be resolved by a management plan alone. A site with such a long operational history also has a number of ingrained practices that are less easy to alter. Fainstein (Citation2000) notes that the communicative model in planning can often come up against existing power systems or the desire of certain groups to retain their power base when it comes to translating consensus into practice. Power structures and politics remain highly present within the PDTRA, and between the PDTRA and the various centralised authorities. Furthermore, in most situations, each player or institution, including those facilitating the process, inevitably continue to be influenced by their own drivers, mandate or priorities which can lead to the subjective interpretation of some issues (Fainstein Citation2000). What the participatory process has achieved, however, is to make a much wider group of stakeholders and actors aware of current issues, including of those beyond their own areas of interest, and generated a level of awareness that empowers these actors to hold the power base more accountable for their actions in the years to come.

Tourism and the immediate economic gratification it delivers continues to influence various stakeholders’ attitude to site management. At the start of the process in 2015, for example, there was a notable downturn in tourist numbers and a greater willingness to identify alternatives or ways in which the site as a destination could be improved and visitor complaints reduced. By the beginning of 2018, the market had picked up, many of the businesses were back in profit, including the PDTRA (whose income is derived from ticket returns) and more innovative approaches became of less interest to the decision makers and for stakeholders with an active interest in tourism.

Trust in the participatory process will only be gained as the recommendations within the IMP are implemented and there is clear evidence that forum and round-table discussions, or individual meetings with a range of stakeholders and community groups are reflected in decision-making. This will also influence future willingness to participate in similar processes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions to the process of Dr Monther Jamhawi, Director General for Antiquities of Jordan and Dr Emad Hijazeen, Commissioner for Tourism and the Petra Archaeological Park at the Petra Development and Tourism Region Authority (PDTRA) for instigating the process and for supporting it throughout, H.E. Mrs Majd Schweikeh and H.E. Ms Lina Annab, Ministers of Tourism and Antiquities at different mandates and Dr Suleiman Farajat, PDTRA Chief Commissioner, for leading the process until the formal endorsement of the plan and members of the technical team, in particular Ms Tahani Al Salhi (PDTRA) and Ms Hanadi Taher (DoA).

A copy of the Petra Integrated Management Plan can be downloaded from https://en.unesco.org/fieldoffice/amman/petra-management-plan

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aylin Orbaşlı

Aylin Orbaşlı is an independent consultant and international expert specialising in the protection, conservation, and management of cultural heritage sites. She is a Reader at Oxford Brookes University and has published widely on the subject.

Giorgia Cesaro

Giorgia Cesaro is a heritage conservation and management specialist working at the UNESCO office in Amman since 2010. She obtained her Advanced MSc in heritage conservation from KU Leuven.

References

- Akerman, L. 2014. “The Evolution of Heritage Management: Thinking beyond Site Boundaries and Buffer Zones.” Public Archaeology 13 (1–3): 113–122.

- Akrawi, A. 2000. “Petra, Jordan.” In Management Planning for Archaeological Sites, edited by J. M. Teutonico and G. Palumbo, 98–112. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Akrawi, A. 2002. “Forty-Four Years of Management Plans in Petra.” In Tourism and Archaeological Heritage Management at Petra, edited by D. C. Comer, 31–76, Springer Briefs in Archaeological Heritage Management.

- Al-Weshah, R., and F. El-Khoury. 1999. “Flood Analysis and Mitigation for Petra Area in Jordan.” Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 125 (3): 170–177.

- Bienkowski, P. 1985. “New Caves for Old: Beduin Architecture in Petra.” World Archaeology 17 (2): 149–160.

- Borges, M. A., G. Carbone, R. Bushell, and T. Jaeger. 2011. Sustainable Tourism and Natural World Heritage: Priorities for Action. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Bryson, J. M. 2004. “What to Do When Stakeholders Matter: Stakeholder Identification and Analysis Techniques.” Public Management Review 6 (1): 21–53.

- Burtenshaw, P., B. Finlayson, O. El-Abed, and C. Palmer. 2019. “The DEEPSAL Project: Using the past for Local Community Futures in Jordan.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 21 (2): 69–91.

- Cesaro, G., and G. Delmonaco. 2017. “Protecting the Cultural and Geological Heritage of Nabataean Petra: Managing Water Runoff and Mitigating Rockfall in the Siq of Petra.” In Precious Water: Paths of Jordanian Civilizations as Seen in the Italian Archaeological Excavations, edited by L. Nigro, 81–92. ROSAPAT 12, La Sapienza: University of Rome.

- City of Regensburg Planning and Building Division, 2012. “World Heritage-Management Plan for the Old Town of Regensburg with Stadtamhof”. Accessed Nov 2017. https://www.regensburg.de/sixcms/media.php/280/STADT_RGBG_MANAGEMENTPLAN_WELTERBE_GB_screen.pdf

- Collins, K., and R. Ison. 2009. “Jumping off Arnstein’s Ladder: Social Learning as a New Policy Paradigm for Climate Change Adaptation.” Environmental Policy and Governance 19 (6): 358–378.

- Comer, D. C., ed. 2012. Tourism and Archaeological Heritage Management at Petra. New York: Springer Briefs in Archaeological Heritage Management.

- Demas, M. 2000. “Planning for Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, A Values-Based Approach.” In Management Planning for Archaeological Sites, edited by J. M. Teutonico and G. Palumbo, 27–54. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Fainstein, S. S. 2000. “New Directions in Planning Theory.” Urban Affairs Review 35 (4): 451–478.

- Feilden, B. M., and J. Jokilehto. 1993. Management Guidelines for World Heritage Sites. Rome: ICCROM.

- Finke, G. 2013. Linking Landscapes. Exploring the Relationships between World Heritage Cultural Landscapes and IUCN Protected Areas. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Global Sustainable Tourism Council. 2017. “GSTC Destination Criteria”.Accessed Sept 2017. https://www.gstcouncil.org/gstc-criteria/gstc-destination-criteria/

- Government of Jordan. 2014. “Jordan Vision 2025”. Accessed April 2021. https://www.greengrowthknowledge.org/national-documents/jordan-2025-national-vision-and-strategy

- Hall, C. M., and S. McArthur. 1998. Integrated Heritage Management: Principles and Practice. London: Stationary Office.

- Healey, P. 2007. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies: Towards a Relational Planning for Our Times. London: Routledge.

- Kono, T. 2014. “Authenticity: Principles and Notions.” Change Over Time 4 (2): 436–460. doi:10.1353/cot.2014.0014.

- Landorf, C. 2009. “Managing for Sustainable Tourism: A Review of Six Cultural World Heritage Sites.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 17 (1): 53–70.

- Muro, M., and P. Jeffrey. 2008. “A Critical Review of the Theory and Application of Social Learning in Participatory Natural Resource Management Processes.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 51 (3): 325–344.

- Orbaşlı, A. 2007. Manual of Management Planning for Antiquities and Tourism Sites in Jordan. Unpublished report.

- Paolini, A., A. Vafadari, G. Cesaro, M. S. Quintero, K. Van Balen, and O. V. Pinilla. 2012. Risk Management at Heritage Sites: A Case Study of the Petra Word Heritage Site. Amman, Jordan: UNESCO Amman Office and University of Leuven.

- Pearson, M., and S. Sullivan. 1999. Looking After Heritage Places. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press.

- Pedersen, A. 2002. Managing Tourism at World Heritage Sites: A Practical Manual for World Heritage Site Managers. Paris: UNES.

- Rababe’h, S. 2010. “Nabataean Architectural Identity and Its Impact on Contemporary Architecture in Jordan.” Dirasat 37 (1): 22–52.

- Richardson, T., and S. Connelly. 2005. “Reinventing Public Participation: Planning in the Age of Consensus.” In Architecture & Participation, edited by P. Blundell-Jones, D. Petrescu, and J. Till, 77–104. London and New York: Spon Press.

- Ringbeck, B. 2007. “Management Plans for World Heritage Sites”. German Commission for UNESCO. Accessed April 2021. https://www.unesco.de/sites/default/files/2018-05/Management_Plan_for_Wold_Heritage_Sites.pdf

- Scholes, K. 2001. “Stakeholder Mapping: A Guide to Public Sector Managers.” In Exploring Public Sector Strategy, edited by G. Johnson and K. Scholes, 165–184. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Smith, J. 2015. “Civic Engagement Tools for Urban Conservation.” In Reconnecting the City: The Historic Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage, edited by F. Bandarin and R. Van Oers, 221–239. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Stein, P. 2015. “Railway Hubs: Changing Track in Stakeholder Engagement”. URBACT. Accessed September 2015. http://urbact.eu/railway-hubs-changing-track-stakeholder-engagement

- Sullivan, S. 1997. “A Planning Model for the Management of Archaeological Sites.” In The Conservation of Archaeological Sites in the Mediterranean Region, edited by M. De La Torre, 21–32. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Turner, M. 2007. “Prehistoric Sites in Regional Context: Management of the Setting and Cultural Landscapes.” In Management, Education & Prehistory: The Temper Project, edited by I. Hodder and L. Doughty, 21–33. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monograph.

- UN Habitat. 2014. Mainstreaming Biodiversity into Tourism Development in Jordan, Preliminary Phase Comprehensive Technical Final Report. Amman: UN Habitat.

- UNESCO. 1994. Petra National Park Management Plan. Paris: UNES.

- UNESCO. 2017. “The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention”. Accessed April 2021. http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/

- UNESCO Amman Office. 2019. “Petra World Heritage Site: Integrated Management Plan”. Accessed April 2021. https://en.unesco.org/fieldoffice/amman/petra-management-plan