Abstract

Objective: To investigate the presence of oxidative stress (OS) in pregnant women with Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) in the first trimester by evaluating thiol/disulphide homeostasis.

Study design: A total of 31 pregnant women with a diagnosis of FMF, between 110 and 136 weeks of gestation, were compared with 51 healthy pregnant controls at the same gestational weeks. A recently defined method was used to measure plasma native thiol, total thiol and disulphide levels.

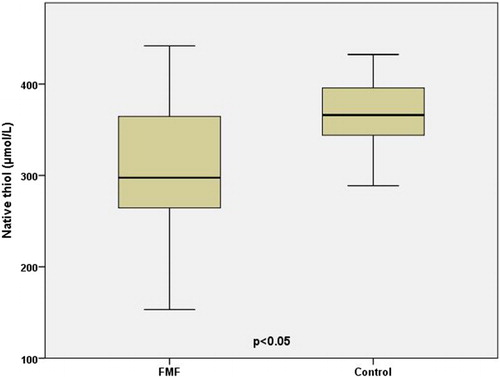

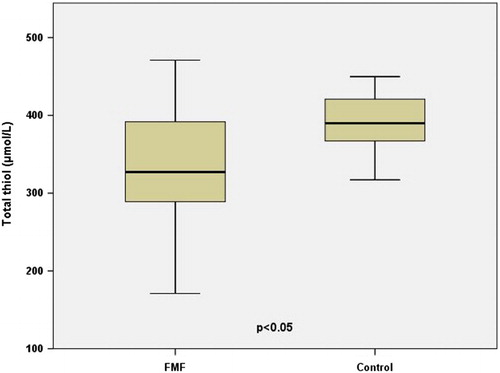

Results: There were no differences between groups in terms of maternal age, body mass index and numbers of gravida and parity. Antenatal complications (45.2% vs. 9.8%, P = 0.001) and primary caesarean section (22.6% vs. 5.9%, P = 0.037) were higher in the FMF group. Pregnant women with FMF had significantly lower first trimester serum levels of native thiol (297.5 μmol/l (153.2–441.8) vs. 366.1 μmol/l (288.7–432.4), P = 0.000), total thiol (327.2 μmol/l (171.0–471.0) vs. 389.9 μmol/l (317.1–449.8), P = 0.000) and higher levels of disulphide (14.2 ± 4.5 μmol/l vs. 12.4 ± 3.4 μmol/l, P = 0.045). No differences were found in these parameters among FMF patients with and without antenatal complications.

Conclusions: The main outcome demonstrates a relation between OS and pregnant women with FMF in the first trimester of gestation. OS in the first trimester may be a major aetiological factor of unfavourable pregancy outcomes in this group of patients.

Introduction

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an autoimmune disease characterized by acute recurrent fever attacks, inflammatory peritonitis, pleuritis and arthritis.Citation1 It is regarded as a systemic disease clinically affecting the kidneys, heart, liver, thyroid and adrenal glands.Citation2 Some unfavourable effects of FMF on gestational outcomes were formerly reported.Citation3

Human cells are embellished with enzymatic and nonenzymatic systems for maintaining redox balance, which is mandatory for growth and survival.Citation4 The term oxidative stress (OS) indicates an imbalance between the production and removal of reactive oxygen species that results in the accumulation of oxidative damage. OS is reported to be involved in many diseases and syndromes.Citation5–Citation7 Nonetheless, until recently in trials aimed at evaluating OS, usually quite complicated methods like high-sensitivity fluorometric high-performance liquid chromatography,Citation8 capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detectionCitation9 and enzymatic recycling,Citation10 and substances such as 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB)Citation11 and dithiodipyridine (4-DPS)Citation12 were used.

Thiols are organic molecules comprising a sulfhydryl group that play important roles in redox homeostasis through oxidation and reduction reactions. In the presence of oxygen, thiol groups are reversibly oxidized to form disulphide linkages. In other words, interconversions between thiols (the reduced state) and disulphide groups (the oxidized state) maintain oxidative balance.Citation13 However, for the analysis of OS, only the thiol side of the balance could be measured, and quantification of the disulphide side could not be performed thus far. In 2014, Erel and Neselioglu defined a novel, simple and practical technique that enables the detection of both sides of the the balance in a practical way.Citation14 We performed this study in order to investigate OS in pregnant women with FMF by evaluating thiol/disulphide homeostasis via the technique recently defined.

Materials and methods

The protocol for this prospective case control study was approved by the institutional review board for human studies of Zekai Tahir Burak Women's Health Care, Training and Research Hospital and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Between March 2014 and March 2015, a total of 31 pregnant women who were referred to our perinatology department with a diagnosis of FMF according to the Tel-Hashomer criteriaCitation15 were compared with 51 healthy pregnant women. The exclusion criteria for the study and control groups were the presence of multiple pregnancies, any systemic diseases other than FMF, any gestational complications such as gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorder, preterm labour, etc. in the previous or the current pregnancy, alcohol or smoking addiction and any chronic drug use other than for FMF (e.g. colchicine).

All venous blood samples of 10 cc were collected in tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) just after ultrasonographic measurement of crown-rump length and nuchal translucency in the first trimester (between 110 and 136 weeks). Plasma samples were separated from cells by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 10 minutes. The samples were run immediately or stored at −80°C.

A new and fully automated method developed by Erel and Neselioglu was used for the measurement of plasma native thiol, total thiol and disulphide levels.Citation14 The method was based on the reduction of dynamic disulphide bonds to functional thiol groups by sodium borohydride (NaBH4). Formaldehyde was used to remove all of the unused NaBH4, in order to prevent extra reduction of 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) and further reduction of disulphide bonds formed after the DTNB reaction. Total thiol content of the sample was measured using modified Ellman's reagent. Native thiol content was subtracted from total thiol content and half of the obtained difference gave the disulphide bond amount. In addition, disulphide/thiol, disulphide/total thiol and thiol/total thiol ratios were calculated automatically at the same time.

Measured values were examined and reported as mean ± standard deviation, median (min–max) and number, % using the SPSS 21.0 statistical program. The normality of the distribution of groups was determined with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Parametric data were analysed by independent two-sample t test and non-parametric data were compared using Mann Whitney-U test. Chi-square test was used for the comparison of percentages. A P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

There were no significant differences between groups in terms of maternal age, body mass index and numbers of gravida and parity (Table ). The rates of antenatal complications (45.2% vs. 9.8%, P = 0.001) and primary caesarean section (22.6% vs. 5.9%, P = 0.037) were higher in the study group (Table ). Characteristics of pregnant women with FMF are shown in Table . Pregnant women with FMF had significantly lower first trimester serum levels of native thiol (297.5 μmol/l (153.2–441.8) vs. 366.1 μmol/l (288.7–432.4), P = 0.000) (Fig. ), total thiol (327.2 μmol/l (171.0–471.0) vs. 389.9 μmol/l (317.1–449.8), P = 0.000) (Fig. ) and higher levels of disulphide (14.2 ± 4.5 μmol/l vs. 12.4 ± 3.4 μmol/l, P = 0.045). In addition, disulphide/native thiol and disulphide/total thiol ratios were higher and native thiol/total thiol were lower in pregnant women suffering from FMF. No differences were measured in serum albumin, total protein, creatinine and blood urea levels (Table ). Comparison of native thiol, total thiol and disulphide levels, ratios and biochemical results among FMF patients with and without antenatal complications did not reveal any significant difference (Table ).

Table 1 Comparison of patient characteristics, antenatal complications and pregnancy outcomes

Table 2 Characteristics of pregnant women with Familial Mediterranean fever (n = 31).

Table 3 Comparison of disulphide levels, ratios and biochemical results

Table 4 Comparison of native thiol, total thiol and disulphide levels, ratios and biochemical results among FMF patients with and without antenatal complications

Discussion and conclusions

FMF is assumed to be an ethnic specific disease with an estimated prevalence of 1/250–1000 in non-Ashkenazi Jews, 1/73 000 in Ashkenazi Jews, 1/500 in Armenians and 1/3000 in Turkish population.Citation16–Citation18 Furthermore, new cases in unexpected communities (e.g Japanese, Korean) have been recently reported with improvements in diagnostic genetics.Citation19–Citation21 Up to now, very limited data about the interactions between FMF and pregnancy have been defined. Thus, new studies of pregnant women with FMF may put forward novel findings with an expanded population and their perinatal characteristics.

OS ensues from a disproportion among the systemic manifestations of reactive oxygen species and the detoxification processes. OS has been evaluated as an aetiological factor in many disorders, including FMF. Karaguezyan et al.Citation22 showed patterns of differences in membrane phospholipid composition that were consistent with increased OS in patients with FMF. Sarkisian et al.Citation23 demonstrated OS in FMF by evaluating clastogenic plasma factors in neutrophils. In addition, Karakurt Ariturk et al.Citation24 showed lower paraoxonase-1 activity, pointing to OS in FMF patients. And recently in a study by Savran et al.,Citation25 FMF seemed to be associated with increased concentrations of macrophage migration inhibitory factor that were significantly correlated with OS. In our view, the results of these studies provide convincing evidence to form a conclusion about the relationship between FMF and OS. However, a careful look at the methods of OS analysis performed in these studies indicates that these procedures cannot easily be integrated into daily clinical practice.

In 2014, Erel and Neselioglu disclosed a new method to establish the dynamic thiol/disulphide homeostasis.Citation14 According to the authors, this technique was less expensive, less time-consuming and less complex than other methods. In our opinion, it is a valuable alternative, particularly with the escalating interest in OS and thiol/disulphide balance, and for studies aiming to understand unknown aspects of the aetiology of disease.

In our study, there was an altered thiol/disulphide balance in pregnant women with FMF, which was previously reported to be an indicator of OS.Citation26 The ratios (disulphide to native thiol × 100 and disulphide to total thiol × 100) that were used to show the overall status of the balance more precisely indicated there was OS in the study group. However, further studies should be conducted in order to clarify the issue of whether OS in pregnant women with FMF is a primary aetiological factor of the disease or secondary to the FMF itself. Previous data, confirming a drop in the ratio of thiol/disulphide as an indicator of cellular apoptosis,Citation27 which is a similar finding to our study, may also suggest that apoptosis is a cause of the unfavourable antenatal complications in pregnant women with FMF. In our opinion, the insignificant differences in OS markers among our FMF patients with and without antenatal complications may be due to the small numbers of participants. Besides supplementation of a thiol donor, such as N-acetylcysteine, may have positive effects on gestational outcomes by boosting the levels of native thiols and protein adjustment, the benefit of which has been proven previously.Citation28,Citation29

In this study, the levels of disulphide were significantly higher in pregnant women with FMF compared to controls. Similar (higher) levels versus controls were reported in patients with degenerative disorders such as diabetes, pneumonia, obesity and smoking.Citation14 Based on this observation, future trials exploring the similarities between FMF and degenerative disorders may reveal more conclusive data about the aetiology of FMF.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations of our study. The drawbacks can be addressed by performing new studies that evaluate other OS markers in addition to thiols and disulphides, that include a relatively larger number of participants, and that have a prospective cohort design targeting more concrete conclusions about the relation between OS and FMF in the gestational period. Moreover, serum analysis during attacks may also provide further data on this issue. Thiol/disulphide examination in all three trimesters, as a longitudinal study design, might manifest not only the alterations of OS markers during gestation but also the percentile ranks for the gestational weeks.

In conclusion, the main outcome of our study demonstrates a relation between OS and pregnant women with FMF in the first trimester of gestation. OS may be a major aetiological factor of unfavourable pregancy outcomes in this group of patients. The method used in our study seems to be a promising, practical and daily applicable test for evaluating thiol/disulphide homeostasis in pregnant women with FMF.

Disclaimer statement

Contributors All authors contributed equally.

Funding None.

Conflict of interest The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval The protocol of this prospective case control study was approved by the institutional review board for human studies of Zekai Tahir Burak Women's Health Care Training and Research Hospital.

References

- Tuglular S, Yalcinkaya F, Paydas S, Oner A, Utas C, Bozfakioglu S, et al. A retrospective analysis for aetiology and clinical findings of 287 secondary amyloidosis cases in Turkey. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;17(11):2003–5. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.11.2003

- Gharabaghi MA, Behdadnia A, Gharabaghi MA, Abtahi H. Hypoadrenal syndrome in a patient with amyloidosis secondary to familial Mediterranean fever. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 Jan 29;2013. pii: bcr2012007991.

- Ofir D, Levy A, Wiznitzer A, Mazor M, Sheiner E. Familial Mediterranean fever during pregnancy: an independent risk factor for preterm delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;141(2):115–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.07.025

- Trachootham D, Lu W, Ogasawara MA, Nilsa RD, Huang P. Redox regulation of cell survival. Antioxid Redox Signal 2008;10(8):1343–74. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1957

- Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and cancer: have we moved forward? Biochem J 2007;401(1):1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061131

- Yilmaz S, Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Demirtas C, Ozturk G, Erkaya S, Uygur D. The oxidative stress index increases among patients with hyperemesis gravidarum but not in normal pregnancies. Redox Rep 2015;20(3):97–102. doi: 10.1179/1351000214Y.0000000110

- Cohen JM, Kramer MS, Platt RW, Basso O, Evans RW, Kahn SR. The association between maternal antioxidant levels in midpregnancy and preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213(5):695.e1–695.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.027

- Dizdar N, Kagedal B, Smeds S, Arstrand K. A high-sensitivity fluorometric high-performance liquid chromatographic method for determination of glutathione and other thiols in cultured melanoma cells, microdialysis samples from melanoma tissue, and blood plasma. Melanoma Res 1991;1(1):33–42. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199104000-00005

- Hart JJ, Welch RM, Norvell WA, Kochian LV. Measurement of thiol-containing amino acids and phytochelatin (PC2) via capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detection. Electrophoresis 2002;23(1):81–7. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200201)23:1<81::AID-ELPS81>3.0.CO;2-V

- Rahman I, Kode A, Biswas SK. Assay for quantitative determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide levels using enzymatic recycling method. Nat Protoc 2006;1(6):3159–65. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.378

- Jovanovic VB, Penezic-Romanjuk AZ, Pavicevic ID, Acimovic JM, Mandic LM. Improving the reliability of human serum albumin-thiol group determination. Anal Biochem 2013;439(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.03.033

- Andersson A, Isaksson A, Brattström L, Hultberg B. Homocysteine and other thiols determined in plasma by HPLC and thiol-specific postcolumn derivatization. Clin Chem 1993;39(8):1590–7.

- Nagy P. Kinetics and mechanisms of thiol-disulfide exchange covering direct substitution and thiol oxidation-mediated pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013;18(13):1623–41. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4973

- Erel O, Neselioglu S. A novel and automated assay for thiol/disulphide homeostasis. Clin Biochem 2014;47(18):326–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.09.026

- Livneh A, Langevitz P, Zemer D, Zaks N, Kees S, Lidar T, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40(10):1879–85. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401023

- Cattan D, Notarnicola C, Molinari N, Touitou I. Inflammatory bowel disease in non-Ashkenazi Jews with familial Mediterranean fever. Lancet 2000;355(9201):378–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02134-0

- Gershoni-Baruch R, Brik R, Shinawi M, Livneh A. The differential contribution of MEFV mutant alleles to the clinical profile of familial Mediterranean fever. Eur J Hum Genet 2002;10(2):145–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200776

- Cobankara V, Fidan G, Türk T, Zencir M, Colakoglu M, Ozen S. The prevalence of familial Mediterranean fever in the Turkish province of Denizli: a field study with a zero patient design. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2004;22(4 Suppl. 34):S27–30.

- Tomiyama N, Higashiuesato Y, Oda T, Baba E, Harada M, Azuma M, et al. MEFV mutation analysis of familial Mediterranean fever in Japan. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2008;26(1):13–7.

- Lee CG, Lim YJ, Kang HW, Kim JH, Lee JK, Koh M-S, et al. A case of recurrent abdominal pain with fever and urticarial eruption. Korean J Gastroenterol 2014;64(1):40–4. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2014.64.1.40

- Kim KT, Jang HJ, Lee JE, Kim MK, Yoo JJ, Lee GY, et al. Familial Mediterranean Fever With Complete Symptomatic Remission During Pregnancy. Intest Res 2015;13(3):287–90. doi: 10.5217/ir.2015.13.3.287

- Karaguezyan KG, Haroutjunian VM, Mamiconyan RS, Hakobian GS, Nazaretian EE, Hovsepyan LM, et al. Evidence of oxidative stress in erythrocyte phospholipid composition in the pathogenesis of familial Mediterranean fever (periodical disease). J Clin Pathol 1996;49(6):453–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.6.453

- Sarkisian T, Emerit I, Arutyunyan R, Levy A, Cernjavski L, Filipe P. Familial Mediterranean fever: clastogenic plasma factors correlated with increased O2(-) – production by neutrophils. Hum Genet 1997;101(2):238–42. doi: 10.1007/s004390050623

- Karakurt Arıtürk Ö, Üreten K, Sarı M, Yazıhan N, Ermiş E, Ergüder İ. Relationship of paraoxonase-1, malondialdehyde and mean platelet volume with markers of atherosclerosis in familial Mediterranean fever: an observational study. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2013;13(4):357–62.

- Savran Y, Sari I, Kozaci DL, Gunay N, Onen F, Akar S. Increased levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in patients with familial mediterranean Fever. Int J Med Sci 2013;10(7):836–9. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6116

- Kundi H, Ates I, Kiziltunc E, Cetin M, Cicekcioglu H, Neselioglu S, et al. A novel oxidative stress marker in acute myocardial infarction; thiol/disulphide homeostasis. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33(11):1567–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.06.016

- Nkabyo YS, Ziegler TR, Gu LH, Watson WH, Jones DP. Glutathione and thioredoxin redox during differentiation in human colon epithelial (Caco-2) cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002;283(6):G1352–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00183.2002

- Suzuki S, Fujita N, Hosogane N, Watanabe K, Ishii K, Toyama Y, et al. Excessive reactive oxygen species are therapeutic targets for intervertebral disc degeneration. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:316. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0834-8

- Avezov K, Reznick AZ, Aizenbud D. Time and dose effects of cigarette smoke and acrolein on protein carbonyl formation in HaCaT keratinocytes. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015;849:57–64. doi: 10.1007/5584_2014_91