ABSTRACT

An emerging literature in political economy focuses on democratic enclaves or pockets of quasi-democratic decision-making embedded in non-democracies. This article first explores the factors that may lead to the emergence of such institutional checks and balances in autocratic politics. I use the comparative analysis of courts in Morocco and Tunisia, and argue that interest group mobilization and the centrality of legalism in political development have been essential for the existence of “governance” enclaves. Second, I explore whether such checks effectively contain everyday rent-seeking, as well as the theoretical channels through which this may occur. Findings from firm-level surveys conducted in Morocco and Tunisia in 2013 indicate that higher general trust in courts, even in modest relative terms, rendered businesses significantly less vulnerable to tax corruption in Tunisia, in sharp contrast to the Moroccan case.

Introduction

Under what conditions does governance improve in non-democratic settings? Why do some authoritarian contexts develop forms of institutional checks and balances while others do not? How do pockets of governance shape the actors’ calculus of voice? The article tackles these questions by examining the historical emergence of relative trust in courts and its current effect on bureaucratic discretion in two Middle East and North Africa countries, Morocco and Tunisia, contexts otherwise characterized by systemic corruption. I argue that the relative perceptions of courts as institutions where taxpayers could appeal administrative discretion with some hope of redress, preempts bureaucrats from monopolizing direct rents.

The argument is motivated by a striking empirical puzzle. Business-state relations are a centrepiece of autocratic rule, and taxation is the undisputed intersection of bureaucratic discretion, political control of important taxpayers, and interventionist policies, serving as both stick and carrot for key economic actors. However, despite the government capture of profitable firms in both countries, ordinary Tunisian businesses have been 20 times more likely to solve tax disputes in court rather than through informal negotiations with the tax administration, a corruption-inducing strategy often adopted by their Moroccan counterparts. Why are courts as venues of appeal of bureaucratic decisions more trusted in Tunisia than in Morocco despite the notoriety of Ben Ali's daily interference with the work of the judiciary? Has this type of governance enclave reduced taxation-related rent-seeking on the margin?

First, the article explores the conditions that led to the paradoxical emergence of relatively functional courts in Tunisia, a country where systemic corruption triggered the Arab Spring. The article suggests that the historical resilience of a “dual” developmental system that accommodated a Weberian legal order and patronage, coupled with the centrality of legalism across different stages of political development carved special spaces of supply and demand for islands of “rule of law” in Tunisia, but not in Morocco – a “monistic” and prebendal system of governance that survived various waves of liberalization.

Second, the article tests empirically whether such historically grounded perceptions of courts have concrete effects on the daily interaction between firms and the tax administration. Despite theoretical foundations and country studies on the existence of good governance enclaves in non-democracies, systematic evidence of their overall impact on meaningful outcomes remains scarce for several reasons. In general, it is difficult to provide accounts of autocratic “checks and balances” that survive beyond short-lived oppositional moments and establish themselves as systematic repositories of decisions guided by good governance considerations only. Moreover, the well-known obstacles to credible responses on sensitive political issues stand in the way of robust inference of individual behaviour in non-democracies. In order to circumvent these problems, the article uses the first reliable nationally representative surveys of 900 firms in the two countries, triangulated with administrative data, and finds that the very existence of minimally functional venues of appeal limits the discretion that tax inspectors exercise during out-of-court settlements. The explanation proposed here refers to relative perceptions and expectations regarding two different institutions at the heart of the state: the judiciary and the tax office.

The first section reviews the mechanics of “good governance” in authoritarian settings. The following section provides an outline of parallel historical developments within the judiciary and tax administrations in Morocco and Tunisia. The third part presents the statistical analysis aiming at testing the precise micro-mechanism that contains corruption. Finally, the article concludes with takeaways and limitations.

Governance enclaves in autocracies

The article joins a family of studies that explore variations within non-democratic regimes in order to uncover the roots of good governance outcomes. The usual analytical focus has been on policies that are either unexpected given regime characteristics, or that run against the core logic of the executive. This literature covers economic and political governance outcomes separately, and poses puzzles often based on a few outliers. Why does the bureaucracy of Singapore top corruption control rankings when our knowledge of non-democratic politics leads us to believe that rent-seeking goes hand in hand with the logic of a small winning coalition?Footnote1 Why has China exceeded expectations of economic growth and poverty reduction despite its lack of inclusive political institutions?Footnote2

Variation in economic governance in non-democracies is not surprising.Footnote3 Historically, some autocratic leaders were able to ignore societal demands and boost growth. Sustainable economic performance or lack thereof depended on the credible commitment mechanisms that non-democrats fostered.Footnote4 Similarly, the existence of “pockets of efficiency” within the bureaucracy cultivated administrative competence in settings where all other institutions were politically colonized.Footnote5

In contrast, variation of political governance processes is more sporadic in autocracies since any potential modification of the “rules of the game” can pose an existential threat to the regime itself. Nevertheless, autocratic polities often host surprising spaces of deliberation and participation that function in otherwise dire political circumstances.Footnote6 Democratic enclaves are “(…) institutional or regulatory spaces where dominant regime values are held at bay”.Footnote7 Parliaments, ombudsmen, tolerated segments of free media and civil society, courts, or bar associations are just a few of such sites that performed as “walled gardens of democracy” within non-democracies.Footnote8

Governance enclaves such as the judiciary have been particularly instrumental in insuring that decision-making is not entirely monopolized by the incumbent. Previous accounts of the role of the judiciary in authoritarian contexts portray a context-specific picture. The Supreme Court of Mexico fulfilled an autocratic role during the democratic transition, whereas other constitutional courts in Latin America tuned rulings according to the anticipated response of powerful executives.Footnote9 In several instances, supreme courts were able to display meaningful resistance against government oppression. The long liberal legacy of the Egyptian judiciary proved resilient in its relationship with both Nasser and Mubarak, creating a reputation for challenging pro-government legislation.

What makes judiciaries become active enclaves in some autocratic contexts but not in others? If oppositional, do they systematically improve daily governance, beyond occasionally providing safe harbour for regime dissidents? Previous answers to the first question emphasize elite cleavages between regime hard-liners and soft-liners that map onto autocratic institutions.Footnote10 In cases where regime soft-liners controlled supreme courts, the judiciary became a politically disputed territory. In 2004, the Malaysian Federal Court protected Anwar Ibrahim from prosecution. In 2007, Pakistan's Supreme Court openly opposed the military, to the point that Musharaf dismissed its Chief Justice and placed judges under house arrest.

I argue that that whereas the literature focuses primarily on Supreme Courts, the role of ordinary tribunals, judges, and lawyers is equally, if not more, important for everyday bureaucratic corruption in autocracies. Courts act as monitoring mechanisms, collect and transmit information to the ruler on the ruled, allow bargains between the state and citizens, and maintain the semblance of procedural legitimacy.Footnote11 In cases of litigation against the state, they may become sites of bureaucratic accountability at the micro-level, thus containing corruption and strategically contributing to the resilience of the system. In Indonesia, Suharto created the administrative court as a check on bureaucratic corruption. Similarly, in China, Vietnam and Singapore, ordinary tribunals have simultaneously fulfilled surveillance and efficiency enhancing functions for reform minded political leaders.Footnote12

Such autonomous spaces of judicial contestation, carved by deliberate design or not, need societal buy-in in order to perform their intended role. When the judiciary was more trusted than other branches of the state, and/or when judges and lawyers articulated real governance demands, relative institutional trust emerged and reduced administrative corruption. In Taiwan's political transition, impartial ordinary courts became credible mechanisms of commitment for the political leadership with respect to businesses.Footnote13 In China, during the late 2000s, lawyers defended activists and ordinary citizens against government abuses. This study suggests that the capacity of the judiciary to reduce bureaucratic corruption is the joint product of will from above and trust from below.

The next section compares the divergent historical paths of the Tunisian and Moroccan judiciaries. Despite partaking in a culture of everyday corruption during autocratic times, Tunisian courts established a relatively higher level of trust among firms and individuals by regional standards, and offered an institutional venue of appeal against bureaucratic abuse. In line with previous findings, even minor variations in the social legitimacy of judiciaries have large multiplier effects.Footnote14 In Morocco, courts never fulfilled this role, being widely perceived as cumbersome sites of corruption and underperformance. After the Arab Spring, these perceptions somewhat reversed, suggesting that the validity of the argument might be confined to the dynamics of autocratic politics only, and apply less well to regime transitions when trust in institutions deteriorates rapidly because of unfulfilled societal expectations.

Morocco and Tunisia: diverging trajectories

Historically, Morocco's political economy has evolved around the Makhzen, a web of power relations connecting the monarchy, the administration, military and rural notables. Earlier analyses of this phenomenon documented the remarkable continuity of a neo-patrimonial system that relied on endemic corruption and survived institutional changes within the Palace, as well as several phases of liberalization.Footnote15 Other interpretations take a dynamic view of power by emphasizing profound shifts occurring within a fluid Makhzen that is simultaneously reconfigured by the monarchy itself and challenged by assertive actors.Footnote16 In 2011, the Arab Spring and its domestic manifestation – the February 20 Movement – led to a constitutional reform, building up expectations of better governance. Nevertheless, despite various phases of reforms that led to marginal improvements, corruption and patronage remain pervasive and are considered primary deterrents of justice and growth.Footnote17 Business-state relations are essential capillaries of informal transactions between the bureaucracy and economic actors, as well as sites where political loyalty and market privileges are routinely exchanged.Footnote18

Before the Arab Spring, Tunisia was mistakenly considered an “economic miracle” because of its dual system that insulated foreign investors from the harsher realities experienced by domestic actors.Footnote19 In 2011, the revolution brought to the forefront the dark side of corruption, rapidly dispelling the myth of Tunisia's good governance-induced miracle. President Ben Ali's regime operated a complex scheme of rent capture, and controlled the most profitable segments of the economy.Footnote20

Politically, both countries had autocratic trajectories. In 2011, Polity IV assigned Tunisia and Morocco an equal score of −4. Their low middle income status and geographical location, as well as significant regional disparities, render these cases comparable. Despite important reserves of petroleum and phosphates, neither Morocco nor Tunisia depend on non-tax revenues. Therefore, taxation became essential for rent allocation and public goods. Rather than boosting capacity, the two systems cultivated exemptions and unequal enforcement. The lack of trust in the state, the perceived injustice of a system that taxes the poor and the middle class but not the politically connected, coupled with corrupt officials lowered the tax morale.Footnote21 Fiscal files also fulfilled an important political role, as accusations against vocal regime opponents were often couched in the language of tax evasion.Footnote22

Yet, notwithstanding corruption as a common everyday reality, in relative terms, there is a striking contrast across indicators of bureaucratic rent seeking experienced in the two cases.Footnote23 According to most measures Morocco lags behind.Footnote24

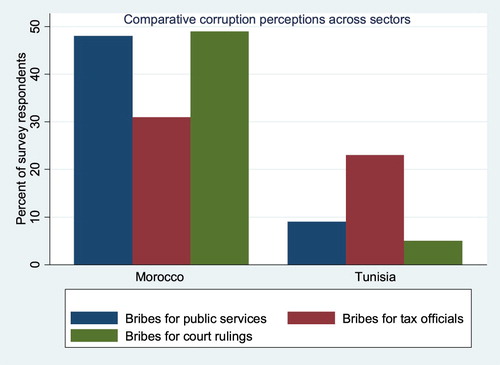

also confirms these significant differences in bureaucratic discretion experienced by firms in the two contexts, suggesting, that in absolute terms, economic actors believe that the fiscal environment and courts are more efficient and fair in Tunisia than in Morocco. also illustrates the relative ratio of trust, by highlighting the significant differences in terms of bribes exchanged by citizens with public sector officials, tax inspectors, and magistrates: in Tunisia, courts are seen as less corrupt than the tax administration, the opposite of Morocco, as a result of parting trajectories.

Table 1. Statistical differences between Moroccan and Tunisian firms’ perceptions (2013).

Figure 1. Comparative citizen perceptions of corruption (2016).Footnote69

The following subsections trace the parallel historical processes that led to the development of tax and legal institutional ecosystems in the two cases in order to address the root causes of divergence in outcomes. The argument emphasizes two longue durée factors at the origins of the relative perception of courts as potential venues of appeal in Tunisia: (a) the historical continuity of a “dual” developmental system resting upon the co-existence of a modern bureaucracy with patrimonial patronage, of “rule-of-law” carved from above and political corruption and (b) the key role and inter-generational mobilization capacity of legal professionals – lawyers and magistrates. In contrast, in Morocco, the monarchy perpetuated a neo-patrimonial system based on patronage revolving around the palace.Footnote25 The Makhzen as a resilient system of rule inherited from pre-colonial times, entangled even the functional segments of the bureaucracy and of the judiciary in a web of personalistic privileges and political loyalty that allowed petty corruption to thrive. Its remarkable durability left little space for efficiency and autonomous social groups within the civil service and the judiciary until recently.

Two caveats are in order regarding the limitations of the argument. First, the claim might appear counterintuitive given the fact that before the Arab Spring, the Tunisian presidential family directly controlled an entangled web of political corruption. In absolute terms, courts have faced severe obstacles during both autocratic and post-autocratic periods, making it impossible to emphasize their effectiveness and independence by global standards.Footnote26 This article simply suggests that even in cases where one key institution such as the judiciary is only marginally more trusted than the bureaucracy, administrative corruption may be contained. Second, any attempt to trace the origins of trust in courts requires an extensive investigation. This process tracing exercise only presents a highly stylized version of bureaucratic and judicial transformations in historical perspective.

Tunisia: developmental “duality” and the centrality of legalism

The Tunisian state formation process starting in pre-colonial times cultivated the co-existence of two antagonistic trends: the creation of a modern bureaucracy in urban centres, on the one hand, and the political co-optation of important landowners from specific rural regions through traditional patronage ties, on the other hand.Footnote27 The early process of bureaucratization mirrored the central administration's imperative to collect revenues from the provinces. Nevertheless, despite a social contract that de jure institutionalized equal rights for the provinces, the urban-rural divide started to take shape. In 1861, a short-lived constitution, co-designed by the French consul and the Tunisian Bey, established mixed tribunals meant to defend the equality of individuals before the taxation and military service laws. De facto, however, a positive outcome in court depended on connections and had an urban bias.Footnote28

The French Protectorate pursued bureaucratic modernization, but marginalized domestic state administrators and the countryside. One of its unintended consequences was the centrality of lawyers and middle class professionals from the provinces who became the main brokers of social and economic relations between rural Tunisians and the colonial administration.Footnote29 This class had the advantage of a Western-style education, the ability to navigate a colonial bureaucracy that was incomprehensible to many notables and ordinary citizens of the provinces, coupled with strong social ties to the rural patrimonial order. The crucial positionality of this emerging class and its ability to translate claims and intermediate relations between a modern colonial bureaucratic apparatus and traditional rural strongholds, allowed the functioning of a “dual” system that combined Weberianism and patrimonialism. The political importance of this group of intermediaries played a key role in the independence movement, as lawyers from the provinces became instrumental for the Neo-Destour party's mobilization strategies, with Habib Bourguiba being its prominent representative.

In 1956, on the eve of independence, Tunisia inherited a modern bureaucracy with high capacity co-existing with patronage ties that the Neo-Destour party brokered in rural areas as a strategy of mobilization during nationalist struggles. Post-independence, Bourguiba continued this hybrid trajectory of development as a strategy of political survival. With respect to the judiciary, the nationalization of habus lands and the integration of shari’ah courts into a secular legal system achieved both modernization and the elimination of his political opponents with religious bases. A nucleus of left-wing lawyers actively pursuing the independence cause and concentrated in the capital also became the catalysts of an inter-generational pro-opposition ethos. Many years later, this organizational legacy and transmission of a vibrant mobilization culture over time and cohorts, contributed to lawyers being the only professional group openly dissenting from Ben Ali's regime.Footnote30

With respect to business-state relations, during the 1970s, following a brief socialist experiment, Prime Minister Hedi Nouira's economic liberalization programme shifted developmental priorities towards the private enterprise, a trend to be continued by subsequent administrations. In 1987, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali became Bourguiba's successor and consolidated power through the Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD). Paradoxically, the two trends of developmental “duality” and the centrality of legalism continued to shape both the supply and demand of relative trust in the judiciary compared to the bureaucracy, albeit in a reconfigured form. Economically, Ben Ali's regime institutionalized a “dual” model of production that de facto segregated firms in offshore and onshore ecosystems, preventing spillover effects. The offshore sector attracted foreign investors, benefited from favourable regulations, experienced little corruption and was able to enforce property rights in courts. This segment cultivated the false myth of the Tunisian “economic miracle.”Footnote31 Within this confined universe, courts performed indeed as tolerated “rule of law” enclaves, fulfilling what Béatrice Hibou eloquently calls “a functional justice” whose function is to “protect a certain order of society” since rulings had a pro-enterprise bias.Footnote32 Observers of judicial performance converge on relatively positive evaluations of court efficiency in autocratic Tunisia.

Simultaneously, Ben Ali and his wife, Leila Trabelsi fostered extensive onshore nepotistic networks involving 662 profitable firms confiscated during the Jasmine Revolution.Footnote33 Capturing the resilient “duality” of Tunisian politics, the RCD party cells also reactivated patronage ties in rural areas in parallel with the presidential family's expansion of land ownership in the provinces. In taxation, the legal ambiguity made non-compliance widespread. This lack of clarity played important roles, allowing both economic and political intervention. Numerous concessions were made to important sectors, whereas audits were used to persecute political opponents. The role of lawyers in fiscal litigation became increasingly constrained and settlements often involved negotiations between the taxpayer and the top echelon of the administration.Footnote34

The role of the Tunisian judiciary has been mixed. On the one hand, most magistrates and prominent lawyers were politically controlled by the RCD. On the other hand, courts gained credibility as spaces to exercise some rights in a repressive regime that otherwise allowed little contestation.Footnote35 In the 2000s, one in three citizens had a pending litigation case. For firms in particular, the professionalized nature of the judiciary and its pro-business bias rendered courts a viable “voice” option.

Politically, some magistrates and a large number of lawyers with collective action potential became the main anti-regime dissidents before the Arab Spring. In 2001, Moktar Yahhyaoui, an influential judge, wrote a highly publicized open letter to the president, condemning the lack of separation of powers. This reaction was itself triggered by a court verdict regarding taxation.Footnote36 During Ben Ali's rule that stifled dissent, the Tunisian Bar Association (ONA) arguably carved the only “enclave” where political and professional demands could be expressed to a certain degree. Its members were lawyers, prosecutors, and retired judges. Whereas in the early 1990s, its head, Bâtonnier Abdelwahab el Behi lobbied for professional rents only, political loyalty started to wane towards the end of the decade.Footnote37 In 2001, Bechir Essid, a former magistrate who opposed Ben Ali became the Bar leader despite the explicit disapproval from the top, including the president's refusal to receive him according to the established protocol.Footnote38 Even during periods of organizational compromise, members of the Bar often mobilized to protest police intimidation and organized sit-ins and strikes.Footnote39

While lawyers are frequent catalysts of anti-regime claims under authoritarianism, judges are more likely to be politically coopted. Tunisia complicates this narrative, as magistrates collectively joined overt opposition both in 1985 under Bourguiba and in 2005 during Ben Ali. Compared to Morocco's longstanding ban on associations of judges, in Tunisia vibrant mobilization took place. The Association of Young Tunisian Magistrates (AJMT) openly demanded independence for the judiciary, organized its first strike in 1985, and as a result, was shut down by the regime. Following this episode, the Association of Tunisian Magistrates (AMT), operational since 1990, took over the professional representation of magistrates and incorporated some of the activist members of AJMT. From this point onwards, the mobilizational life of the judiciary became a story of competing factions, as AMT has been highly contested between pro and anti-regime factions in 2004 and in 2005, following the arrest of a dissident lawyer. In 2005, the regime intervened, closed its headquarters and transferred dissenting judges to remote locations.Footnote40

In 2010, the mobilization capacity of lawyers was unmatched by any other organized group in pre-Arab Spring Tunisia and had deep roots in the historical centrality of the profession. On the eve of the Jasmine revolution, a large number of young lawyers from low and middle socio-economic backgrounds became vocal against the lack of professional opportunities confined to an elite circle with political connections to RCD. This skewed composition of the Bar led to significant discontent. The claims brought together a generation of older activist lawyers socialized during the Bourguiba period and younger members, and resulted in “trans-generational” reactions to the regime, thus carrying the historical legacy of collective action over time.Footnote41 In 2015, the Bar Association won the Nobel Prize for its key role in the political transition.

In contrast to lawyers and sporadic judges, during the Arab Spring, a large majority of magistrates were supporters of the status quo. This divergence of positions with deep roots in the autocratic past and surfacing in the early revolutionary moments eventually led to fierce competition for power within the judiciary that took the public form of mutual accusations of corruption and tainted association with the ancien régime. In 2011, the political status of lawyers boosted by strong revolutionary credentials translated into attempts to expand the institutional power of the Bar, and triggered protests from judges. Between 2012 and 2015, the clashes between the two groups became highly mediatized. These back and forth confrontations included corruption allegations brought by Kasserine lawyers against many judges, strikes on both sides, and the mobilization of judges against the recruitment of 533 lawyers to the magistrature.Footnote42

As a result, after the Jasmine Revolution, public trust in the judiciary dropped dramatically, and perceptions of its corruption have been on the rise. According to the Arab Barometer survey, 2013 has been an inflection point for citizens’ trust that paved the way for a downward spiral. Courts suffer from material shortages and low efficiency of judicial processes. Transitional justice challenges, intense media coverage of corruption scandals and of the revolutionary/counter-revolutionary cleavages among judges and lawyers steadily eroded general trust in courts.Footnote43 This trend is in line with previous studies showing that increased institutional competition coupled with media freedom and a higher level of political awareness lead to lower public confidence in the state and the judiciary in transitional contexts.Footnote44

Morocco: prebendal “monism”

Historically, unlike the Tunisian judiciary that hosted heterogeneous attitudes towards the autocratic regime and gained some credibility, the Moroccan tax administration and courts were both integrated into a system of personalistic rents and privileges that directly tied access to spoils for civil servants and judges to their loyalty to the palace. After independence, King Mohamed V, followed by King Hassan II, consolidated a monarchy relying on a patrimonial system that favoured the countryside.Footnote45 In 1999, Mohamed VI, initiated a process of political liberalization and signalled a departure from its traditional rent system. Despite improvements, the palace remained the political hegemon. The judiciary is often considered to be “the single greatest impediment to progress on the anti-corruption front,” and post-Arab Spring revelations regarding the magnitude of individual bribes paint a picture of a systemic “justice for sale” to the highest bidder and “telephone justice”.Footnote46 In contrast to Tunisia, there is no relative difference in institutional trust between the Moroccan bureaucracy and courts, and both rank at the top of citizens’ corruption perception which closed the space for alternative “voice” mechanisms. Pervasive perceptions of an inefficient and politically dependent judiciary shaped the reluctance of the public to even go to court at all.Footnote47

Taxation in Morocco has been characterized by low capacity, opaqueness, and a prevailing perception of unfairness.Footnote48 Since 1980s, agriculture has not been taxed, whereas other sectors benefited from numerous exemptions. Perceptions of an unfair fiscal contract led to a low tax morale and distrust that widened the space for bureaucratic discretion. Tax collection became personalized via individual settlements and amnesties with arbitrary targets.Footnote49 Direct negotiations between the administration and the taxpayer rendered both parties complicit. The administration had leverage over taxpayers. This bureaucratic power often took the form of corruption or undue political influence in case of the files of regime opponents. Simultaneously (and selectively), businesses were able to settle for less taxes or bypassed audit.

Until recently, discretion was procedurally tolerated. Despite efforts to narrow the legal space for it, the most controversial form of administrative interference survived as everyday practice. A special procedure gave tax inspectors the power to re-assess the financial standing of a firm based on subjective criteria.Footnote50 This allowed bureaucrats to re-estimate profits without evidence that would stand in court.Footnote51 Surveys identified the tax administration as the most corrupt branch of the bureaucracy.Footnote52

A 2011 Taxpayer Chart defined the venues of appeal for parties involved in a fiscal dispute. Notwithstanding legal safeguards, reports on appeals suggest that more than 90% of cases never go through such procedures, being instead settled through a direct agreement between the administration and taxpayers. This type of settlement is almost always preferred because of a general “lack of trust in the administrative and judiciary procedures”.Footnote53

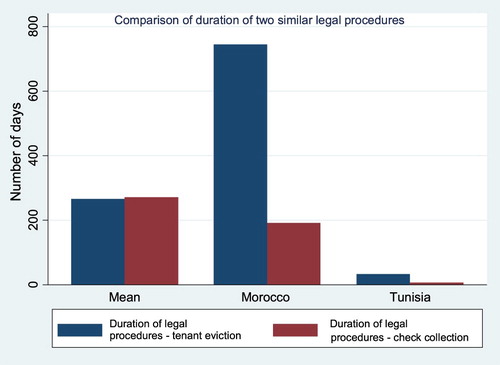

This lack of trust in the Moroccan judiciary stems from a combination of widespread corruption, severe capacity shortcomings and lack of political independence. A recent study found that 82% of respondents in a nationally representative sample believe that wasta (or informal connections) lead to favourable rulings, and as a consequence, have lower trust in courts.Footnote54 Capacity wise, the judiciary has faced shortages in the number of magistrates, professional training and material resources.Footnote55 Formal procedures are lengthy and costly, prohibitive for most businesses, and the competence of many judges is questionable. The courts are in general perceived as not being able to enforce decisions even in cases when a positive verdict is reached.Footnote56 shows contrasting examples of duration in court proceedings in Morocco and Tunisia before 2003, providing evidence that striking objective differences of performance were fully observable during a stable autocratic period, and is not an artifact of recent transition data.

Figure 2. Duration of legal procedures.Footnote70

Politically, members of the Moroccan judiciary have rarely engaged in collective action to assert independence from the Palace since the very position of magistrate has been historically viewed as a royal privilege that opened access to prebendal rents. Seventeen bar associations splintered the mobilization potential of lawyers, while magistrates have not been allowed to unionize prior to the 2011. The few judges who challenged the lack of autonomy of Moroccan courts have been punished.Footnote57 Until 2011, the appointments and careers of judges were entirely dependent on the King and the Minister of Justice who also headed the High Judicial Council, a controversial body of judicial oversight.Footnote58 The 2011 Constitution spearheaded by the Arab Spring for the first time included an article (art. 111) that explicitly allows professional mobilization, and institutionalizes safeguards for judicial independence. Despite reforms, key appointments still need the direct approval of the monarch. Administrative courts are heavily influenced by the executive, and legal exemptions limit the de facto capacity of magistrates to act collectively. All factors considered, the high level of corruption in the judiciary, combined with capacity shortages and a lack of independence have cultivated significant public distrust. Tellingly, even the Judicial Agency that represents the fiscal interests of the state lacks access to courts and does not trust them.Footnote59 The tax administration itself participates in less than 9% of all litigation cases initiated by the state.Footnote60 This process led to the individualization of the relationship between the bureaucracy and firms and bred wide discretion.

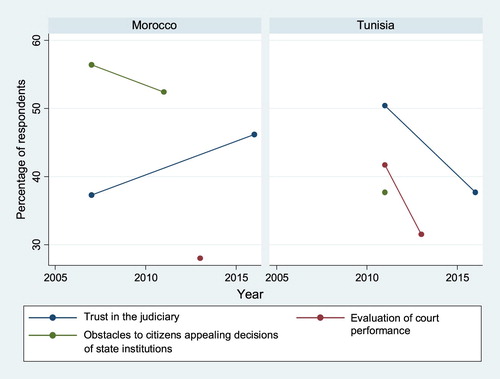

One of the noteworthy developments occurring after 2011 is the increased political assertiveness of members of the judiciary. Between 2012 and 2014, a majority of Moroccan judges participated in some of the largest national-scale protests organized by the Judges’ Club, a post-Arab Spring association demanding judicial reforms. In 2014, the protest was banned and the riot police called in. Contrary to the Tunisian case, the public trust in the judiciary has been on the rise after 2011, capturing a reaction to emerging mobilization from below, in addition to performance-enhancing reforms of the judiciary from above, and in the absence of competition between transitional factions that might have accompanied a more comprehensive political transition ().

Figure 3. Evaluations of public trust and performance of courts.Footnote71

The impact of “governance” enclaves on everyday bureaucratic discretion

The previous section argued that generalized perceptions of courts as “governance” sites emerged in Tunisia for historical reasons. But what is the micro-logic that translates them into lower bureaucratic corruption?

Albert O. Hirschman famously posited the dilemma of two alternatives an organization faces in an unfavourable climate, exiting the country or exercising voice, enabled by loyalty, through governance demands.Footnote61 This choice is determined by the relative cost to benefits of each option. Whereas this logic applies well to capital flight for large firms with a global outlook, in non-democratic regimes, ordinary non-connected economic actors cannot exercise “exit” in their relationship with the state. Does this non-option induce “voice” as Hirschman's theory posits?

In taxation, in the absence of exit, I argue that there is also a less discussed option of “passive” or “do-nothing” loyalty that entails complying with unfair tax assessments or bribe demands, and stands in stark contrast to Hirschman's pro-active loyalty that leads to real “voice” by challenging the practices of bureaucrats. If judges are expected to be even more corrupt than tax inspectors, then recourse to court with the risk of paying a higher bribe is unnecessarily costly and entirely irrational. Only the general perception of courts as a viable “voice” channel (more able, less corrupt) makes economic actors less likely to be trapped in a situation of “do-nothing” loyalty to a discretionary bureaucracy.

I depart from Hirschman (1970) in two ways. First, in the absence of exit, “do-nothing loyalty” becomes a cheaper alternative to costly “voice”, as opposed to being “a key concept in the battle between exit and voice” in Hirschman's original conceptualization.Footnote62 Second, I argue that the perceived costs and benefits matter for choosing voice and curbing discretion. The general perception of viable “voice” may lead to an equilibrium whereby economic actors are more likely to challenge the administration in courts when facing discretion, and officials to exercise restraint ex-ante, aware of the anticipated effectiveness of such venues of appeal. Based on this micro-level theoretical prediction along with the historical insights into the diverging trust systems in the two contexts, we should observe the following:

H1a: Firms are likely to update their individual evaluations of courts based on the general perceptions of the judiciary as a venue of appeal when they experience bureaucratic discretion. This expectation implies that Tunisian firms should be likely to see courts as more trustworthy venues when facing tax problems compared to normal times, whereas in contrast, Moroccan respondents are likely to downgrade their perception of courts, anticipating a low chance of appeal success for a higher bribe.

H1b: Subsequently, the higher relative trust in courts should lead to more judicial appeals in Tunisia and reduce bureaucratic discretion ex-ante, as tax inspectors have to comply with higher standards of evidence accepted in court.

Normatively, this theory does not imply that corruption is a one way transaction that benefits bureaucrats while victimizing firms. Revenue constraints render tax collection efforts necessary, while profit incentives place many taxpayers in non-compliance, with negative consequences for procedural fairness and public good production. In this sense, courts, if functional, also serve as appeal venues for the state itself when trying to combat evasion.

Empirical analysis

This section searches for systematic evidence that macro-historical differences between the two contexts affect current micro-behaviour and, to this purpose, uses World Bank's 2013 Enterprise Surveys of the first nationally representative samples for Morocco and Tunisia collected immediately after the Arab Spring.Footnote63 The two questionnaires are identical and contain detailed questions regarding the legal system. This unique feature allows precision in testing the theoretical mechanism. If, indeed, the context-driven evaluation of courts matters, one should observe significant differences in firms’ reactions towards tax related problems between Morocco and Tunisia.

A valid concern stems from the fact that the perceptions captured by the survey in 2013 may tap into transition related trends rather than reflecting the dynamics of autocratic polities. In the absence of pre-2011 reliable hard data on this topic, there are several sources of reassuring evidence that the identified pattern indeed carries a non-democratic legacy. First, even as public trust in judiciary starts changing course in the two contexts after 2013 as post-transition pessimism settles in, Tunisians’ evaluations of judicial performance and of the possibility of appealing state decisions still outpace the Moroccan perceptions significantly and corroborate anecdotal pre-transition accounts ().

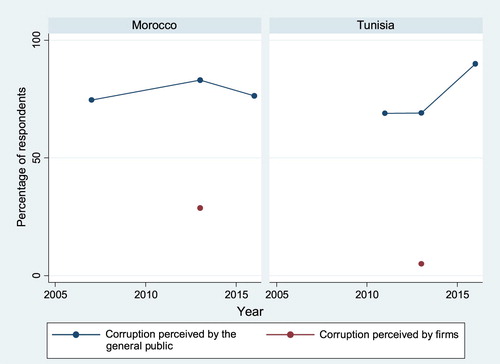

Second, both authoritative qualitative information and the divergence of corruption perceptions between firms and the general public in Tunisia and Morocco give us solid reasons to believe that business-state relations involving tax authorities and the judiciary have been more resilient and stable compared to general trust in institutions even during the post-Arab Spring transition ().

Figure 4. Evaluations of corruption by the general public and businesses.Footnote72

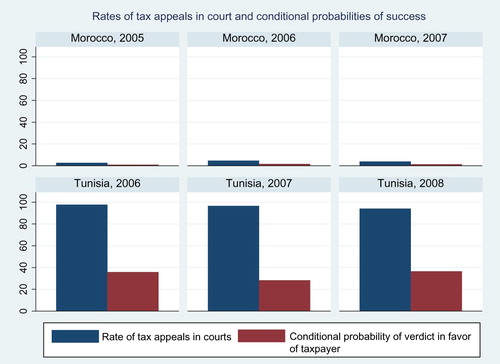

Third, these trends corroborate the fragmentary comparative data collected by international organizations prior to the Arab Spring. shows the contrast between court procedures in Morocco and Tunisia in the early 2000s, and suggests that rates of court appeals and success differ considerably between the two countries during stable autocracy, based on data collected between 2005 and 2008.

In this sense, the choice of 2013 for these empirics qualifies as a “least–likely crucial case” analysis,Footnote64 or as the strictest non-experimental test that can be performed: even when public perceptions of the judiciary are reversing in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, Tunisian firms and citizens still place a credibility premium on courts vis-à-vis the bureaucracy compared to their Moroccan counterparts. Data after 2013 suggest that the trend has been reversing ().

The joint sample includes over 900 firms. of Appendix contains summary statistics. The analysis works with both objective and perception based data. Whereas the former paints a stark contrast in appeal outcomes between the two contexts, firms’ divergent perceptions of relative trust in institutions offer the only evidence that allows distinguishing between different theoretical channels that might lead to the same observable outcomes. For instance, it could be the case that the individual experience with the justice system or the procedural differences between the venues of appeal in the two contexts rather than the relative trust in institutions shaped by the historical processes traced in the previous section lead to the gap in outcomes.

Hypothesis 1a searches for a “hope for appeal” mechanism through which firms update individual perceptions of courts in cases of bureaucratic harassment. Therefore, the ideal statistical test should verify whether respondents’ perceptions of courts in the two contexts change in times of tax hardship or not. Indeed, whereas upgraded or downgraded perceptions in troubled times may not automatically translate into actual voice for an economic actor, I argue that they capture institutional hope for redress or lack thereof. To compensate for testing subjective perceptions, Hypothesis 1b and the objective data used for it show that actual court appeals match the subjective test.

Dependent variable

Courts’ ability to enforce decisions is a four-point Likert scale variable that ranges from 1, indicating that the respondent firm did not evaluate courts as being effective enforcement venues, to a maximum value of 4 that indicates high capacity. Whereas all the other court evaluation dimensions are significantly higher for Tunisian respondents in line with history-grounded expectations, this variable has the advantage of being the only dimension of the legal system with a similar mean in both contexts (). The online appendix also conducts robustness tests using Court fairness/lack of corruption as an alternative dependent variable.

Independent variables

The most important regressor for this analysis is Tax administrative constraints, a 0–4 ordinal variable whose higher values imply bureaucratic harassment or other forms of obstacles. If Hypothesis 1a is correct and the general trust in courts shapes the hope for appeal, one should be able to observe respondents modifying their a priori beliefs when faced with hardship compared to normal times. To rule endogeneity out, I use two instrumental variables capturing crucial tax events in the life of a firm that temporally precede the perception variable gauging tax constraints. Tax audit is a dichotomous measure that takes values of 1 if the respondent has been audited during the previous year and 0 otherwise. Competitors’ tax practices is a dummy variables taking values of 1 if the firm's main competitors are perceived as not having paid taxes. Both instruments are theoretically informed by many studies that conceptualize fiscal contracts as entailing both an individual experience dimension (audit) and a procedural equity assessment (unfair practices of other taxpayers condoned by the administration).Footnote65

As controls, Court experience records whether the firm has faced litigation in tribunals recently, anticipating this objective measure to counterbalance the abstract effect of generalized trust in courts. The analysis also includes important respondent-level characteristics such as age, size, location and sector. The online supplementary material provides a detailed protocol for all variables.

Findings

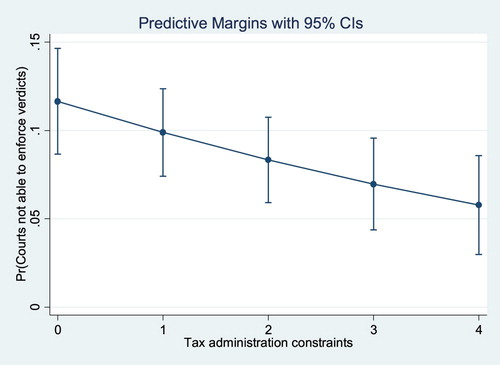

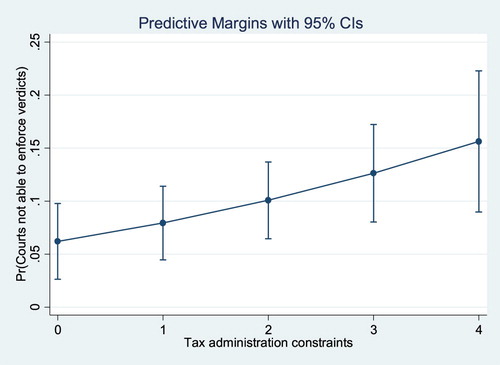

The comparative analysis below demonstrates the mechanism of updating individual beliefs about courts when firms feel threatened by the discretion of tax officials. shows diverging paths in the two environments. The statistical model offers a quasi-experiment since, despite almost equal country-level means in general evaluations of the enforcement capacity of the courts across the two contexts, actual exposure to administrative obstacles triggers contrasting responses. In Morocco, businesses that perceive significant constraints posed by tax inspectors to their daily activity are 8% less likely to see courts as effective. In contrast, Tunisian firms are around 10% more likely to update positively their perceptions in cases of administrative harassment, improving their baseline beliefs. The more firms are dissatisfied with tax inspectors, the more likely respondents are to upgrade their beliefs that courts are able to enforce decisions.

Table 2. Updating beliefs in courts’ ability to enforce verdicts.

and show the predictive margins for the two contexts.

Figure 5. Predictive margins (Morocco, all controls).Footnote73

This finding supports the argument that Moroccan firms have even less hope of redress in courts in the event of a tax dispute than they would have in normal times, whereas Tunisian firms upgrade their evaluation of court performance when experiencing bureaucratic hardship. The results are robust to OLS and Ordered Probit, as well as to various specifications (Online Appendix).Footnote66

As an identification strategy, Models 3–6 use Tax audit and Competitors’ tax practices as joint exogenous instruments for Tax administration constraints. The exclusion restriction requires the two instruments to have an effect on trust only via administrative constraints, the endogenous regressor. Two pieces of evidence suggest that this is indeed the case. First, temporally the instruments precede the perception measure of harassment, and theoretically there is no reason to believe that previous audits and assessment of fiscal enforcement justice would have an independent effect on court perceptions through another channel. In fact, they are strongly significant in the first stage, but not in the second (Online Appendix). Second, both the F-tests that exceed the cutoff value of 10 in all models, and the overidentification tests (Sargan/C) for joint instrumentation suggest that the two instruments are both exogenous and strong (). Models 5 and 6 capture an interesting nuance as they exclude firms with prior court experience. For respondents who rely on general trust only (and not on direct exposure to courts), problematic tax encounters have a much larger and significant effect on their subjective evaluations of courts in the expected direction – negative for Morocco and positive for Tunisia.

Hypothesis 1b requires objective “voice” proxies rather than perception based evidence that when economic actors experience significant obstacles because of tax officials, their reactions fit the theoretical expectations, namely that Morocco should have lower rates of recourse to courts compared to Tunisia. Reliable comparative data for the autocratic period (2005-2008) show the systematic discrepancy between the two contexts ().Footnote67

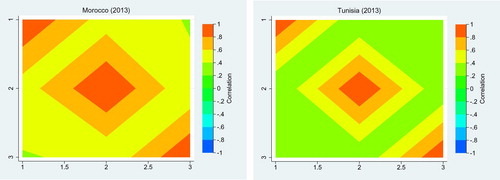

In terms of overall corruption assessments, Tunisia outperforms Morocco ( and ). also shows the correlation heat maps. For Moroccan firms, corruption, tax administration constraints and negative perceptions of courts go together. In Tunisia, the significantly lower correlation of these three dimensions captured by colour differences (Y axis), signals important variations across the three areas, suggesting the mechanism of relative perception of institutions at work.

Conclusion

Why do courts act as “governance” enclaves in some autocratic regimes? How do they impact bureaucratic discretion? The answers come from both historical and individual-level explanations.

The article first tackled the historically-rooted divergence of generalized trust in courts in Morocco and Tunisia. In Tunisia, unlike in Morocco, a resilient developmental “dualism” that combined Weberian bureaucracy with patronage and cronyism carved pockets of rule of law from above, and allowed spaces for legal professionals to mobilize against the state since the colonial period. The Moroccan judiciary, with sporadic exceptions, has never reached the same level of autonomous behaviour and mobilization, being an integral part of the rent system. The post-Arab Spring evolution is reversing the trends.

On a micro-level, the analysis traced step-by-step the effect of trust in courts on curbing the abuses of tax inspectors. Taxation is an area of particular importance in non-democratic regimes because it fulfils both economic and political functions of punishment and reward. By exploiting identical nationally representative surveys of firms in the two contexts with contrasting processes of state development, I found that the relative perceptions of judicial processes as venues for expressing “voice” are essential for limiting administrative discretion. Because of a higher general level of trust in courts due to historical circumstances, Tunisian firms are likely to view appeal more favourably than Moroccan businesses. Anticipating the path of “voice” as opposed to “do-nothing loyalty,” tax officials reduce discretion ex-ante.

Theoretically, the article also aims to make a contribution to our understanding of business-state relations under autocracy, as well as to the “exit, voice, loyalty” framework. First, in the case of taxation, “do-nothing” loyalty leads to collusion in the absence of hope for redress, contrary to Hirschman's conceptualization of loyalty as an enabler of voice. Second, general perceptions of checks and balances might be the most important factor in the individual decision of “voice,” deterring discretion ex-ante by holding bureaucrats to higher procedural standards.

This theory highlights the contrast between the development of checks and balances in the two countries, and should not be read as endorsing the Tunisian case as best practice. Indeed, corruption, collusion, and transitional justice challenges are serious and have been severely eroding public trust in courts in post-Jasmine Revolution Tunisia.Footnote68 In relative terms, however, the micro-level data and the trajectory of its judiciary show that even modest perceptions of “governance” enclaves may curb bureaucratic discretion on the margin.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Barbara Geddes, Navid Hassanpour, Jeff Haynes, the participants at the American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, 2017, and two anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cristina Corduneanu-Huci

Cristina Corduneanu-Huci is an Assistant Professor at the School of Public Policy of the Central European University, Budapest, Hungary. Her work has appeared in Business and Politics, Comparative Sociology, World Politics, and several edited volumes. She is the co-author of two books on the politics of economic development.

Notes

1. Bueno de Mesquita et al., Political Survival.

2. Acemoglu and Robinson, Why Nations Fail?

3. Przeworski et al., Democracy and Development.

4. Gehlbach and Keefer, “Investment without Democracy”; Wright, “Do Authoritarian Institutions Constrain?”

5. Geddes, Politician’s Dilemma.

6. Wedeen, “The Politics of Deliberation”.

7. Gilley, “Democratic Enclaves,” 407.

8. Ibid., 391; Gandhi, Political Institutions under Dictatorship; Wright, “Do Authoritarian Institutions Constrain?”

9. Helmke and Julio Ríos-Figuero eds., Courts in Latin America; Magaloni, Voting for Autocracy.

10. Przeworski. Democracy and the Market.

11. Ríos-Figueroa and Aguilar, “Justice Institutions in Autocracies”.

12. Moustafa, “Law and Courts” ; Peerenboom, Judicial Independence.

13. Ma, “Judicial Independence”.

14. Gloppen, “The Accountability Function of the Courts”.

15. Waterbury, “Endemic and Planned Corruption”.

16. Catusse, Le Temps Des Entrepreneurs?

17. Denoeux, “Corruption in Morocco”.

18. Catusse, Le Temps Des Entrepreneurs?

19. Hibou, La Force de L'Obéissance.

20. Rijkers, Freund and Nucifora, “All in the Family”.

21. In MENA, 45% of respondents paid a bribe to tax officials (GCB 2016).

22. Cammett, Globalization and Business Politics; Catusse, Le Temps Des Entrepreneurs?; Hibou, La Force de L'Obéissance.

23. Hibou, La Force de L'Obéissance.

24. The 2016 Transparency International CPI ranks Tunisia at the 75th position and Morocco at the 90th with scores of 41, and 37.

25. Anderson, The State and Social Transformation; Waterbury, “Endemic and Planned Corruption”.

26. Hibou, La Force de L'Obéissance, 117.

27. Anderson, The State and Social Transformation.

28. Ibid., 82–3.

29. Ibid., 139.

30. Gobe, “Lawyers Mobilizing,” 8–9.

31. Cavatorta and Haugbølle, “The End of Authoritarian Rule”; Hibou, La Force de L'Obéissance, 162–3.

32. Hibou, Ibidem, 119.

33. Rijkers, Freund and Nucifora, “All in the Family”.

34. Hibou, La Force de L'Obéissance.

35. Ibidem, 117–8.

36. Ibid., 145.

37. Gobe, “The Tunisian Bar”.

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid.

40. Gobe, “Penser les Relations”.

41. Gobe, “Lawyers Mobilizing,” 8–9.

42. Gobe, “Penser les Relations”.

43. Sultany, Law and Revolution, 170.

44. Çakır and Şekercioğlu, “Public Confidence in the Judiciary”; Sharafutdinova, “What Explains Corruption Perceptions?”.

45. Leveau, Le Fellah Marocain; Waterbury, “Endemic and Planned Corruption”.

46. Denoueux, “Corruption in Morocco,” 144.

47. Greene, “Rule of Law in Morocco”.

48. Akesbi, “Une Fiscalité Complexe”; Al-Andaloussi, “Rapport de Diagnostic”; Al-Dahdah et al., Rules on Paper, 45–70.

49. Berrada, “Politique Fiscale”.

50. EESF. Elbacha, Les Procédures de Taxation.

51. Cour des Comptes, Rapport Annuel.

52. Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism; Transparency Maroc (TAM), “La Transparence”.

53. Al-Andaloussi, “Rapport de Diagnostic,” 23.

54. Buehler. “Do You Have "Connections"?”.

55. National Integrity System. “2015 Report: Morocco,” 52–4.

56. World Bank. “Morocco”.

57. The founder of Amdim (the Moroccan Association for the Defense of Judiciary Independence).

58. International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), “Reforming the Judiciary”.

59. Cour des Comptes, Rapport Annuel, 11.

60. Ibid., 5.

61. Hirschman, Exit, Voice and Loyalty.

62. Ibid., 82.

63. World Bank. Enterprise Survey.

64. Gerring, “Is There a (Viable)”.

65. Levi, Of Rule and Revenue.

66. The online supplementary material shows several robustness tests.

67. PEFA, “Performance de la Gestion,” 54.

68. GAN Business Anti-corruption Portal, “2017 Tunisia”.

69. Global Corruption Barometer (GCB), “People and Corruption”.

70. Data from Djankov et al., “Courts”.

71. All available Arab Barometer waves (2007–2016).

72. Ibid.

73. See Online Appendix for computation.

Bibliography

- Acemoglu, Daron, and James Robinson. Why Nations Fail? The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York: Crown Publishing, 2012.

- Akesbi, Najib. “Une Fiscalité Complexe, Incoherente et Injuste.” Études et Sondages. La Revue Economia 73, no. 3 (2008): 92.

- Al-Andaloussi, Driss. Rapport de Diagnostic: Transparence et Gestion Fiscale au Maroc. Rabat: Oxfam, 2015.

- Al-Dahdah, Edouard, Cristina Corduneanu-Huci, Gael Raballand, Ernest Sergenti, and Myriam Abbassa. Rules on Paper, Rules in Practice: Enforcing Laws and Policies in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2016.

- Anderson, Lisa. The State and Social Transformation in Tunisia and Lybia, 1830–1980. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Arab Barometer Survey Data Waves I-IV (2006-2016).

- Berrada, Abdelkader. “Politique Fiscale et Déficit Persistant de Transparence et de Performance.” REMA. Revue Marocaine d’Audit et de Développement 33 (2012): 273–298.

- Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson, and James D. Morrow. The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

- Buehler, Matt. “Do You Have ‘Connections’ at the Courthouse? An Original Survey on Informal Influence and Judicial Rulings in Morocco.” Political Research Quarterly 69, no. 4 (2016): 760–772. doi: 10.1177/1065912916662358

- Çakır, Aylin Aydın, and Eser Şekercioğlu. “Public Confidence in the Judiciary: the Interaction Between Political Awareness and Level of Democracy.” Democratization 23, no. 4 (2016): 634–656. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2014.1000874

- Cammett, Melani. Globalization and Business Politics in Arab North Africa. A Comparative Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Catusse, Myriam. Le Temps Des Entrepreneurs? Politique et Transformations Du Capitalisme Au Maroc. Institut de Recherche sur le Maghreb Contemporain. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose, 2008.

- Cavatorta, Francesco, and Rikke Hostrup Haugbølle. “The End of Authoritarian Rule and the Mythology of Tunisia Under Ben Ali.” Mediterranean Politics 17 2 (2012): 179–195. doi: 10.1080/13629395.2012.694043

- Cour des Comptes. Rapport Annuel de la Cour des Comptes, Rabat, 2015, 2013/2015.

- Denoeux, Guilain P. “Corruption in Morocco: Old Forces, New Dynamics and a Way Forward.” Middle East Policy XIV, no. 4 (2007): 134–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4967.2007.00329.x

- Djankov, Simeon, Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. “Courts.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118, no. 2 (2003): 453–517. doi: 10.1162/003355303321675437

- Elbacha, Farid. Les Procédures de Taxation et de Vérifications Fiscales. Quelles Garanties pour les Contribuables? Rabat: Centre Marocain des Études Juridiques, 2006.

- GAN Business Anti-corruption Portal. “2017 Tunisia Corruption Report.” Accessed June 3, 2017. http://www.business-anti-corruption.com/country-profiles/tunisia.

- Gandhi, Jennifer. Political Institutions Under Dictatorship. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Geddes, Barbara. Politician’s Dilemma: Building State Capacity in Latin America. Vol. 25. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

- Gehlbach, Scott, and Philip Keefer. “Investment Without Democracy: Ruling-Party Institutionalization and Credible Commitment in Autocracies.” Journal of Comparative Economics 39, no. 2 (2011): 123–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jce.2011.04.002

- Gerring, John. “Is There a (Viable) Crucial-Case Method?” Comparative Political Studies 40, no. 3 (2007): 231–253. doi: 10.1177/0010414006290784

- Gilley, Bruce. “Democratic Enclaves in Authoritarian Regimes.” Democratization 17, no. 3 (2010): 389–415. doi: 10.1080/13510341003700196

- Gloppen, Siri. “The Accountability Function of the Courts in Tanzania and Zambia.” Democratization 10, no. 4 (2003): 112–136. doi: 10.1080/13510340312331294057

- Gobe, Éric. “The Tunisian Bar to the Test of Authoritarianism: Professional and Political Movements in Ben Ali’s Tunisia (1990–2007).” The Journal of North African Studies 15, no. 3 (2010): 333–347. doi: 10.1080/13629380903251478

- Gobe, Éric. “Penser les Relations Avocats-Magistrats dans la Tunisie Indépendante: Conflictualité Professionnelle et Dynamique Politique.” Politique Africaine 138, no. 2 (2015): 115–134. doi: 10.3917/polaf.138.0115

- Gobe, Éric. “Lawyers Mobilizing in the Tunisian Uprising: A Matter of ‘Generations?’” HAL –Archives Ouvertes (2017).

- Global Corruption Barometer (GCB). “People and Corruption: Middle East and North Africa Survey 2016.” Transparency International (2016).

- Greene, Norman L. “Rule of Law in Morocco: A Journey Towards a Better Judiciary Through the Implementation of the 2011 Constitutional Reforms.” ILSA J. Int’l & Comp. L. 18, no. 455 (2012): 458–513.

- Hirschman, Albert O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Vol. 25. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970.

- Helmke, Gretchen, and Julio Ríos-Figueroa. Courts in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Hibou, Béatrice. La Force de L’Obéissance: Économie Politique de la Répression en Tunisie. Paris: Éditions la Découverte, 2006.

- International Commission of Jurists (ICJ). Reforming the Judiciary in Morocco. Geneva: ICJ, 2013.

- Leveau, Rémy. Le Fellah Marocain, Defenseur du Trône. Paris: Presses de la Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques, 1985.

- Levi, Margaret. Of Rule and Revenue. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan Way. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Ma, David K. “Judicial Independence and State-Business Relations: The Case of Taiwan’s Ordinary Courts.” Democratization 24, no. 6 (2017): 889–905. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2016.1242580

- Magaloni, Beatriz. Voting For Autocracy: Hegemonic Party Survival And Its Demise In Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Mersch, Sara. “Judicial Reforms in Tunisia.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. April 10, 2015.

- Moustafa, Tamir. “Law and Courts in Authoritarian Regimes.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 10 (2014): 281–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110413-030532

- Peerenboom, Randall. Judicial Independence in China. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- PEFA. Maroc – Rapport sur la Performance de la Gestion des Finances Publiques. Evaluation des Systèmes, des Processus et des Institutions de Gestion des Finances Publiques du Maroc. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2009.

- PEFA. “Performance de la Gestion des Finances Publiques en Tunisie.” European Union, World Bank and African Development Bank, 2010.

- Przeworski, Adam, Michael Alvarez, José Antonio Cheibub, and Fernando Limongi. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950-1990. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Rijkers, Bob, Caroline Freund, and Antonio Nucifora. “All in the Family: State Capture in Tunisia.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6810. (March 1, 2014).

- Ríos-Figueroa, Julio, and Paloma Aguilar. “Justice Institutions in Autocracies: a Framework for Analysis.” Democratization 25, no. 1 (2018): 1–18. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2017.1304379

- Sharafutdinova, Gulnaz. “What Explains Corruption Perceptions? The Dark Side of Political Competition in Russia’s Regions.” Comparative Politics 42, no. 2 (2010): 147–166. doi: 10.5129/001041510X12911363509431

- Sultany, Nimer. Law and Revolution: Constitutionalism After the Arab Spring. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Transparency Maroc (TAM). “La Transparence dans la Gestion des Recettes Fiscales.” Transparency News, no. 8 (2009): 6–16.

- Transparency International. Morocco: National Integrity System Assessment 2015 (27 January 2017).

- Waterbury, John. “Endemic and Planned Corruption in a Monarchical Regime.” World Politics 25, no. 4 (1973): 533–555. doi: 10.2307/2009951

- Wedeen, Lisa. “The Politics of Deliberation: Qat Chews as Public Spheres in Yemen.” Public Culture 19, no. 1 (2007): 59–84. doi: 10.1215/08992363-2006-025

- World Bank. “Morocco. Legal and Judicial Sector Assessment.” Washington, DC, 2003.

- World Bank. Enterprise Survey (Morocco and Tunisia). Washington, DC, 2013.

- Wright, Joseph. “Do Authoritarian Institutions Constrain? How Legislatures Affect Economic Growth and Investment.” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 2 (2008): 322–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00315.x

- Yadav, Vineeta, and Bumba Mukherjee. The Politics of Corruption in Dictatorships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.