?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In this article, we investigate how the political geography of local power and national-subnational alignment influences the distribution of conflict between election contests. We ask how consistently local intermediaries, such as members of parliament (MPs), can sustain their own support and that of their successful national candidate. The best measure for the ability of local elites to generate and keep support is candidate vote margins. These election results recast elites and areas as core, swing or costly regime investments, which in turn influences the streams of patronage and authority between election cycles. Based on the political geographies that result from subnational election data for 13 African countries, we find that in core areas where support for the leader is high, there is limited violence by state forces; state violence is significantly higher in areas costly to the national leader; and violence by non-state armed actors (e.g. militias) is most likely to occur in swing areas where the winning margin of the last legislative election is narrow for the local candidate. It is in these swing regions that competing political elites engage in violence to replace poorly performing local intermediaries.

The geography of regime support and political violence

In this article, we explore the political antecedents to subnational conflict risk across African states. We find that the geography of national-local political alignment and leverage is directly associated with conflict variance across regions. Leverage refers to how consistently local intermediaries and representatives, such as members of parliament (MPs), can sustain their own support and that of their successful national candidate during election contests; and alignment concerns whether the regime’s national and local support is coordinated. To gauge the ability of local elites to generate and keep support, we use candidate vote margins during the most recent election. Election results provide significant information to leaders, and pre-empt shifts in a regime’s political geography of support. These results also recast local elites and areas as core, swing or costly regime investments, which in turn influences the streams of patronage and authority. Core areas are where loyal local elites return high vote margins, or where leaders have unchallenged support; costly areas are where opposition candidates perform strongly relative to candidates of the ruling party in local or national elections; and swing areas are where local elites struggle to generate sufficiently strong support for themselves or the national election winner, with vote margins that are close between parties. “Swing” returns discredit regime elites as local “gatekeepers”, and harm continuing ties and patronage between regimes and communities.

For leaders of “competitive autocracies” or “violent democracies”, internal elite consolidation and coalition building is vital: a regime’s internal politics is often far more important than external and opposition competition. In these cases, “playing the margins” of elite politics is necessary to sustain their rule, and managing local level elite support is pivotal.Footnote1 For this reason, leaders seek sustained alignment with local intermediary “gatekeepers”, although gauging local support levels can be difficult. Presidential and legislative election results, even in the often distorted political environment where such contests occur, can provide leaders with an assessment of who and where has strong networks to support the regime, and who and where is of questionable support. In short, they return information about how the effectiveness of local intermediaries, the utility of clientalist practices, and the coordination between national and local powers.Footnote2 By acknowledging how leaders use election results to inform internal politics, and the direct effects on the “geography of regime support”, we conclude that the volatile political geography of states exposes core, swing and costly elites and regions for regimes.

We suggest that local and national support are vital for the sustained power of regimes, and the variance of regime and local support has direct effects on political violence rates. We confirm that the political geography of support shifts substantially during consecutive electoral cycles from thirteen African states for the past twenty years. Using the changing political geography of support that emerges between elections, we distinguish three distinct violence outcomes: in core areas where support for the leader is high, there is limited violence by state forces; state violence is significantly higher in areas costly to the national leader; and violence by non-state armed actors (e.g. political militias) is most likely to occur in swing areas where the winning margin of the last legislative election is narrow for the local candidate. It is in these swing regions that competing political elites engage in violence to sustain or replace local gatekeepers. Significant levels of political violence in competitive autocracies and transitioning democracies across Africa can be explained by this dynamic, which concentrates on intra-party competition,Footnote3 and volatile political geographies resulting from election results in the longer term.

Our inquiry concentrates on the links between political elite competition and new forms of non-state violence that persistently occur across developing states. Reflecting on the conflict rates and forms that dominate many African and developing states, we argue that violence is functioning as a local political corrective: it is not a failure of the system, but a feature of the political structure and reinforcement mechanisms like election performance. A key characteristic of non-state violent groups across these states is that they often do not engage state security forces, but are motivated by the competition of elites who are often within the same party. Militias are, in turn, paid for and supported by these respective elites. This violence results from the competitive politics of inclusion: to gain entry into the system, opportunities to remove local elites are seized by other contenders. Violence across communities or directed towards the support bases of politicians is a direct attempt to weaken local political authority, and propel other contenders into positions of “local gatekeeper” of regime authority. While significant attention has focused on electoral violence and the variations of conflict in and around elections, how election results recast a state’s political geography is under-researched. This study is not an inquiry into pre-or-post-election violence. Rather, we use election results as information for how regimes understand their territorial bases of support in the medium to longer term, and how violence rates are responsive to that new geography of leverage and alignment.

This article challenges perspectives which suggest that a state’s political geography, and the spatial variation of violence risk, is pre-determined by physical location, resource deposits, or ethnic homelands.Footnote4 It complements research which finds that several forms of co-occurring conflict are associated with variable centre-local government political alignment,Footnote5 and that results of legislative elections inform regimes about their local support in states where national results are often predetermined.Footnote6 Finally, we advance the notion of swing support in African and authoritarian systems: most research in Africa has presented voting as pre-determined, and corresponding to identity politics.Footnote7 But, the level and dynamics of local support varies, and so too does a leader’s calculations about subnational support and ties. In short, local politics causes conflict.

This article first reviews the literature on subnational support across authoritarian and hybrid regimes. It then discusses the resulting geography of local and national support and its relationship to election outcomes in developing states. From that vantage, the risk, form and frequency of conflict relating to local power dynamics is reviewed and hypotheses are presented. Our research design considers where reliable information on both presidential and legislative elections is available, and how we link those dynamics to local conflict event data. The following section presents the results of the empirical analysis. In the concluding section, we summarize by reflecting on how intra-party competition, political alignment and spatial variations in conflict risk tie together several distinct areas of African political research.

National and local alignment in authoritarian regimes

Many African regimes adopted select democratic institutions and features in their transition to “hybrid” or “competitive authoritarian” regimes.Footnote8 Yet many of those states retained dominant parties, preventing the alternation of political power.Footnote9 In transitions to democracies, shifts in alignment politics arguably allowed regimes to exert greater control on subnational elites through gauging their support and leverage at consistent junctures.Footnote10 Indeed, regimes in “competitive autocracies” continue to retain power through aligning subnational and national support, and sustaining those ties of loyalty and dependence with local political elites through patronage and ceded authority. Across “competitive autocracies”, and in established democracies (e.g. Ghana) or fledgling democracies (e.g. Sierra Leone), leaders depend on central and subnational support structures to secure and extend the regime’s authority across the state.Footnote11 Consequently, despite the adoption of formal “democratic” institutions, African leaders remain only as strong as the central and regional elite coalitions that support them. The ties within those coalitions, the composition of a regime’s support structure, and the stability of centre-local political linkages are fundamental features to modern African regimes.

To sustain the ties that hold their regimes, leaders engage in inclusive, transactional exchanges with a wide array of subnational elites. Individually, subnational elites such as MPs and cabinet members have variable, often consistently low, levels of independent power.Footnote12 Regime elites vary in identity, regional background, and are often members of “congress” parties that dominate many African states.Footnote13 Inclusivity is superficially arranged to reflect a state’s heterogeneous character, but the composition and consolidation of the leader’s elite coalition is – at its best – a reflection of where support is strongest.Footnote14 In practice, leaders build a subnational support structure by accommodating the right mix of elites from communities in the majority of regions. This involves assembling and sustaining a loyal elite coalition through transactional, volatile, and costly strategies.Footnote15

This logic of integration and “rent-sharing” is expanded upon by Gandhi and Przeworski, Acemoglu and Robinson, and Boix who note that the co-option and commitment of elites to the regime is accomplished through state appointments, opportunities to advance within the regime, rent streams, and access to economic resources.Footnote16 These constitute mutual “investments” in the ruler’s survival.Footnote17 In short, in exchange for political alignment, elites and their representative groups expect patronage and opportunities. The result is an implicit contract between leaders and local elites, such as members of parliament, governors, mayors or the like: leaders provides benefits to the local elites who are most likely to deliver consistent support based on clear evidence of their ability and credibility to do so. The relationship between elites is one of loyalty to the regime, and a co-dependence for political and electoral support. For leaders, high levels of “loyalty and dependence” is necessary for sustained survival and stability.

Subnational practices of alignment: gatekeeping, loyalty and dependence

The alignment between leaders and MPs or other representatives creates a “territorial politics” that rewards loyal elites who can mobilize reliable voters and ensure acquiescence at the local level.Footnote18 Patronage is exchanged for votes in a coordinated and hierarchical system of exchange.Footnote19 Relationships that underlie territorial politics are mediated through political parties, who co-opt local elites and build effective support structures as they ensure the provision of a willing pool of loyal supporters and the buy-in of local elites.Footnote20 Parties also provide a cost-sharing arrangement with subnational elites for mobilization, a mechanism to mitigate defections and challenges, and a means to gauge individual elites’ local popularity.Footnote21 Without established parties, leaders, MPs and other local elites must build and renegotiate those alliances in a costly cycle of transactions.

The role of subnational elites is to represent their community, acquire and distribute patronage, and secure their own leader’s support in a region. Fulfilling those roles is based on their own ability to leverage local networks and support for stronger relationships with national elites. Their successes make them “gatekeepers”, who can capture and control national resources to sustain their supporter-clients.Footnote22 Gatekeepers exercise power by controlling access between leaders and voters, and voters and patronage: they are intermediaries with local power. A successful gatekeeper uses their networks and position to align with regime demands, reinforce their local authority, limit competition, and generate profits for themselves and surrounding elites. These practices underlie the practices of, for example, tying disaster relief to political party membership: in Zimbabwe, ZANU-PF MPs and party authorities distribute food aid in villages according to the party roster, for which they are responsible for generating.

To sustain a gatekeeping role, elites suppress internal and external competition. Opposition politicians’ overtures to people must be curtailed, but threats to local elites also come from within their party. Gatekeepers face competition from other local elites for access to this lucrative position. To maintain power, gatekeepers limit the access of other elites by maximizing their own influence in local politics, through a suite of tactics called “boundary control”.Footnote23 These practices include removing challengers or opposition figures like mayors, packing city councils, denying funds to municipalities, or motivating arbitrary investigations, and the co-optation or division of other elite support groups. Such strategies have significant consequences for subverting democracy at the subnational level, allowing gatekeepers to exert control over other potential network leaders.

Gatekeepers intermittently gauge their local strength and control over their ethno-political networks. Local and national elections are periods where a gatekeeper’s loyalty to, and dependence on, the leader is assessed in terms of his/her return of support. These elections are referenda on whether gatekeepers have a dominant support network. Without the leverage of a wide and willing community of voters, gatekeepers fail to perform their end of the patronage-for-support transaction. A failure to return sufficient evidence of local loyalty nullifies their role and is insufficient to warrant support from national elites. In turn, this opens up competition for the gatekeeping role from other contenders.

Elections as loyalty and management exercises

Elections in competitive autocracies rarely lead to leadership change, and function less as a political competition than as an assessment of local alignment strategies. Results determine the geography of support, and shape decisions around the “churn” of elites: this involves identifying and possibly removing poorly performing subnational elites, and co-opting well performing members when they deliver votes and areas of support.Footnote24 Recast as an exercise for leader information rather than a public choice or democratic pursuit, election results underlie intra-elite management practicesFootnote25 and act as “most important device for the distribution of rents and promotions to important groups within the politically connected and party structures.”Footnote26 Leaders treat them as loyalty tests, as they provide considerable information about public support and elite leverage at the local levelFootnote27; and enormous majorities allow them to reassert their power relative to other elites, making the cost of defection ever higher.Footnote28

Legislative elections also provide considerable information about leverage and public support for MPs and other local elites: citizens may actively support their incumbent if they expect her to continue distributing privileges,Footnote29 or they may reduce or transfer their support – at a cost.Footnote30 Voters are less beholden to specific local elites, and can change which representative they believe will return sufficient benefits through their relationships with leaders. Legislative results provide an assessment of how well specific elites can sustain local support, and how well voters rally to demonstrate the strength of these networks.Footnote31 Marginal support indicates that a specific elite provides a poor return for communities’ investment. In this way, legislative elections are a competition for local gatekeeping, and a referendum on the local gatekeeper. Elections, therefore, have two functions above their overt purpose of political competition: for leaders, results allow for an assessment of loyalty and dependence levels in constituencies, and possible political recalibration in alignment. For local elites, voting results in their constituency is a measure of their local leverage.

A geography of political alignment emerges based on local performances: when winning national candidates and their associated intermediaries, such as MPs, receive strong support in an election, levels of “loyalty and dependence” are high, and the gatekeepers become more powerful as a result of their enhanced ability to access to and distribute valued resources. In safe seats, gatekeeping is reinforced with strong alignment, and these seats constitute part of the “political core” where the monopoly of the regime is sound.

Areas where voters support the opposition for national or local office are “costly”, and the price of voter loyalty is prohibitively expensive for regimes. In turn, the local alignment between the regime and subnational elites is weak, and a patronage relationship is nullified by disloyalty and limited dependence ties. As evidenced by the recent work on elections and violent conflict, leaders of competitive authoritarian regimes will be most likely to use paramilitary or armed forces to demobilize opposition supporters with violent intimidation,Footnote32 disturb the opponent’s territorial control,Footnote33 and/or punish disloyal elites in these costly areas. In short, “costly” areas are likely to be hot spots of state violence.Footnote34

When election results for either national or local elites are marginal, these areas are “swing” regions. Where there are narrow results, and no local candidate has a decisive lead, nor can the candidate secure substantial support for a national candidate, the gatekeeping role has not accomplished its function. Marginal and low support outcomes nullify local elites’ role as gatekeepers, and the associated appeal for patronage. These “swing” areas are a grave concern for regimes, as the impact of gatekeeping is heightened, and the support margins are small and actionable for both regimes and opposition parties. Meanwhile, a specific MP will be challenged by an alternative contender over the coming election cycle. Regimes will want to encourage alignment through an alternative representative in order to “correct” future election support and mitigate the likelihood of entrenching a marginal or opposition seat. It is in such swing areas that the risk to gatekeepers is highest and the seats most competitive.

All possible iterations of alignment from core, swing and costly support for national and legislative elections candidates are not equally likely. Support for leaders is rarely marginal,Footnote35 yet legislative election candidates have high rates of attrition and removal.Footnote36 Therefore the local effects of elections are evident, while the national aggregated result can obscure more volatile individual changes.

Election results show geographical shifts in alignment from one cycle to another. This suggests that core, swing and costly regions are in a state of flux, and even incumbent regimes can lose seats or need to fight for marginal districts, despite using a number of corrupt methods to secure an overall national result in their favour.Footnote37 Therefore, if a regime’s support and leverage is volatile, the distribution of power and authority resulting from electoral competitions is also in flux.

Political geography and violence: elite competition and election consequences

The political geography we suggest here is a dynamic representation of local and national alignment and leverage. We argue that conflict patterns are closely tied to the political competition that emerges from these variable political geographies. Rather than observing election violence, we specifically uncover violence patterns occurring in the years between contests in core, costly and swing areas. We suggest that the competition matrix is made and remade following elections, and there is a strong link between legislative election outcomes and the security of local, intermediary elites in the medium term.

Previous research has demonstrated that African states that regularly hold elections are still experiencing high rates of non-state violence driven by competing political elites and their associated militias. Boone and Herbst, for example, explain these patterns based on the “topography of governance”, and conclude that areas outside of the governing catchment were more likely to engage in violence against the state.Footnote38 Wig and Tollefsen find that districts with high-quality local government institutions are less likely to experience violence in an internal conflict than poorly governed districts.Footnote39 Raleigh confirms that politically excluded areas are more likely to experience civil war compared to integrated parts and communities, but crucially, politically integrated areas with open political competition have higher rates of political militia violence.Footnote40 The political violence common in these states is often performed by non-state groups like militias, who represent elites and is bound to specific geopolitical, subnational spaces.Footnote41 These studies complement findings that political violence by militias in response to local and regional political competition is growing across AfricaFootnote42 and is a direct result of democratic transitions and the dynamics of political inclusion.Footnote43

Rather than the typical parameters of election violence, which concentrates on the level of competition between regime and opposition candidates, the violence that occurs from swing alignment should be between elites competing for local authority, and often can be conducted between members and representatives of the same party. Competition to usurp seats is most fierce within incumbent parties across Africa, as demonstrated by the recent work concentrating on candidate nomination processes.Footnote44 Within an increasingly formal political system where inclusion is key to prospects of clientelistic relationship, poor performances by intermediaries at all scales of the political hierarchy should invite competition. We gauge how core, swing and costly seat alignment creates different incentives for violence, and results in variable violence rates by state and non-state actors. We hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1: High levels of violence are most likely to occur from competition in regions that return “swing” results for local candidates. Where the winning margin of the last legislative election is narrow for the candidate, high levels of non-state violence are expected. This violence is not intended to rebel or challenge the state or leader, but reflects the contest at the level of gatekeeper.

Hypothesis 2: In “costly” areas for winning presidential candidates, higher levels of state violence are expected. The two functions of this violence is to punish costly areas and to limit the appeal of opposition support elsewhere.

Research design

This study uses “region-years” as the unit of analysis. Each region enters the dataset in the year of the first election, either presidential or legislative, during the sample period of 1997-2018. The conflict data come from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED) whose political conflict data are distinguished by event characteristics and group(s) participating, with geographical location and date.Footnote45 We use ACLED to distinguish between four types of dependent variables: yearly numbers of (1) active non-state armed organizations; (2) violent events targeting civilians (hereafter anti-civilian violence); (3) violent events where state agents were actively involved (hereafter state violence); and (4) all reported political violence events within a particular region. The first two variables are used to test H1. That is, we expect to see higher numbers of active non-state actors in “swing” regions where local elites are most likely to use personal armies or militias for political competition. In addition, a majority of militia activities are directed towards civilians, as attacking unarmed people is relatively costless for militias with variable level of organization, training and supplies.Footnote46 Moreover, civilian groups are often tied to the patronage or authority of different elites: thus, attacking such communities undermines a political figure’s claim to protection and patronage. The third dependent variable tests H2, while the last one is intended to test both H1 and H2, or interaction of both types of electoral competition ─ legislative and presidential.

Election data for political geography

Data for legislative and presidential elections for 13 African countries came from a variety of sources, including the African Elections Project,Footnote47 the Psephos project,Footnote48 state election boards, local newspaper reports, the EISA’s African Democracy Encyclopedia Project,Footnote49 and other researcher sources.Footnote50 The collection and use of data on African elections posed three major challenges. First, voting data at the regional or constituency level vary considerably across time and countries since the size, name and formation of constituencies can change frequently.Footnote51 This required significant data management to match “correct” constituencies to their corresponding first-level administrative units, and to assure that the aggregated constituencies remain constant over twenty years of the sampling period.Footnote52 Yet, while first-level administrative divisions are the default unit, the variation across countries can be substantial: for example, Uganda has more than 120 first-level administrative districts, while South Sudan has far fewer. To get comparable levels of coverage, by population ratio or similar sized areas, we occasionally used second-level administrative units if sufficient data are available.

Second, these spatial disparities lead to another issue: how should we interpret the gatekeeper role? Localities can be associated with specific gatekeepers, but at every scale there are multiple potential gatekeepers, who are situated in a formal hierarchical structure. We take the administrative division in order to interpret the highest level of subnational alignment, where the combined effects of legislative candidates create a core, swing or costly region. As previously noted, individual MPs and other elites often have little authority; rather, the subnational character of the combined support (or challenges to support) is important to the regime. To demonstrate the cascading effect of the alignment from constituency to first-level administrative units, we support the results with an in-depth investigation. Third, subnational election results were not available for some cases such as, for example, legislative elections in Uganda (2001, 2006, 2011, 2016) and Nigeria (1999, 2003), and presidential elections in Kenya (1997, 2002, 2007), Tanzania (2010) and Ghana (2008). This leaves us with a total of 27 legislative elections in 12 countries, and 28 presidential elections in 12 countries.Footnote53

Despite these limitations, we believe, the dataset as a whole represents the spectrum of hybrid or competitive authoritarian regimes in Africa. These thirteen states are a cross-selection of African countries that have held consecutive elections in the past twenty years. They are transitioning democracies, from regressive and progressive, according to both Polity and Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) projects, but all have substantial opposition parties and coalitions.Footnote54 They are also states for which subnational election results were fully or at least partially available for successive contests, which is still relatively rare. The cases also vary in terms of the level of political violence they experience, and who commits that violence. In summary, these 13 states are appropriative examples and proxies for the remaining African states, and the common political calculations and strategies of rulers and local elites.

Explanatory variables

The number of contenders in each constituency is often very large, some of them unfamiliar even to voters. Long list of candidates/parties create difficulties in operationalizing electoral competition in legislative elections. To extract as much relevant information as possible from a large amount of data, we count the total number of votes received by candidate(s) of the “winning” president’s party (or ruling party) and compare it with that of the leading opposition party within each region. The same practice applies to presidential elections: for each region, the total number of votes received by national winner (or president-elect) is compared with that of the second-place candidate, regardless of incumbency.

Therefore, the first explanatory variable is the vote share of the ruling party’s candidate(s) in region i () from the last legislative election. This is given by:

(1)

(1) where

stands for the total votes received by the ruling party’s candidate and

is the total votes received by the leading opposition party’s candidate in region i. Similarly, the next explanatory variable is the vote share of president-elect in region i (

) from the last presidential election, which is given by:

(2)

(2) where

is the total number of votes for the winner and

is the total votes for the second-place contender in region i. If the two candidates went for the second round of the presidential elections, final results of the second round were used to calculate

.

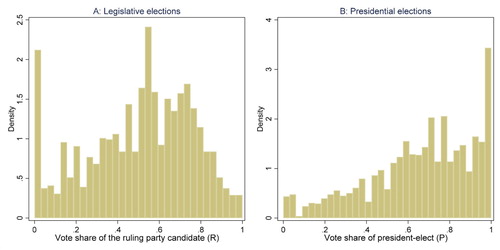

provides histograms of and

variables in the entire sample that pools all regions together. In legislative elections, the distribution of vote share received by the ruling parties is fairly symmetric, with about the same number of regions receiving more than 50% of the vote as those with less than 50% (see A). The peak at 0% is mainly driven by the 2007 general election in Kenya where President Mwai Kibaki's Party of National Unity (PNU) did not field candidates in some opposition strongholds. On the other hand, the distribution of vote share for president-elects is skewed towards 100% (see B): there are relatively few regions in which winning presidential candidates won less than 50% of the vote. Overall, these histograms illustrate that, in African general elections, races for seats in the legislature tend to be more competitive than those for the presidency.

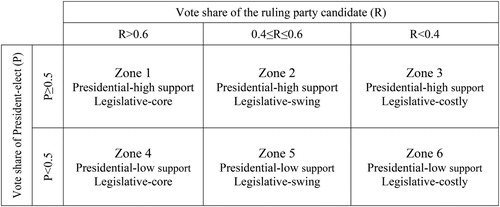

To further analyse the interaction between both types of electoral competition and its implications for political violence, we also create six dummy variables referring to specific zones of electoral competition. These variables indicate how elite competition at the local level is “aligned” with the national competition for the presidency. They are measured in the following manner: Zone 1 is coded 1 if >0.6 and

≥0.5; Zone 2 is coded 1 if 0.4≤

≤0.6 and

≥0.5; Zone 3 is coded 1 if

<0.4 and

≥0.5; Zone 4 is coded 1 if

>0.6 and

<0.5; Zone 5 is coded 1 if 0.4≤

≤0.6 and

<0.5; and Zone 6 is coded 1 if

<0.4 and

<0.5. These variables are 0 otherwise. The baseline category in the regressions is Zone 1, which represents the “modal” type of electoral competition comprising 34.3% of the observations. A Zone 5 dummy variable, which is of greater theoretical interest than others, comprise 5.4% of the observations (or 93 observations). Following our two hypotheses, we expect that highest levels of violence occur in this zone where the winning margin of the last legislative election was narrow and the president received less than 50% of the vote. The operationalization of dummy variables is visualized in .

Remaining model specifications

We include the following control variables to account for other factors that may influence conflicts through other channels. First, we control for the effects of “power shift” by identifying whether an opposition party came to power after winning the last election. New Power is a dichotomous variable that takes the value of 1 for the first term of the ruling political party, and 0 otherwise. Secondly, we use the Capital dummy variable to identify regions where the nation’s capital is located. We expect that proximity to the capital city promotes greater competition for state power and thus violent conflict. Next, we include the natural log of the region’s Population.Footnote55 All else equal, we expect that larger regions are more likely to experience conflicts. In order to control for the influence of past violence, we also include a Past Violence dummy variable which is equal to 1 if more than 100 violent events occurred within a particular region during the previous election cycle, and 0 otherwise.Footnote56 At the country level, we include a Democracy dummy variable which is coded 1 if a country’s Polity score is 6 or above, and 0 otherwise.Footnote57 While several mechanisms have been proposed on the effects of democracy, we expect that incumbents are more likely to punish costly areas in non-democratic contexts where they exercise greater power and control over opposition supporters.Footnote58 Furthermore, we control for the influence of dominant party and ethnic heterogeneity. A Party Control variable is V-Dem’s three-point index that measures the extent to which “a single party controls all or virtually all policymaking bodies across subnational units.” Here, “0” means “In almost all subnational units” and “2” “In few units.”Footnote59 When the ruling party has dominant control over local authorities and thus succession decisions for gatekeeper positions, intra-party competition in swing districts might be less violent.Footnote60 An index of Ethnic Heterogeneity captures the probability that two randomly selected individuals in a country will not belong to the same ethnic group.Footnote61 Lastly, for each election type, we create the variable Post-election Years, which counts how many years have passed since the last legislative or presidential election. These variables account for the duration dependence of election effects on political violence. provides a summary of statistics for all variables used in the analysis.

Table 1. Summary statistics for explanatory and control variables.

A Poisson model with regional random effects tests the hypotheses and accounts for the discrete nature of the dependent variables. Random effects at the regional level account for time-invariant, unobserved characteristics that are likely to influence the average level of conflict within a region, such as historical grievances, the presence of ethnic minorities, and geographic characteristics (e.g. mountainous terrain, natural resource endowments, etc.). All models are estimated with robust standard errors clustered by region.

Results

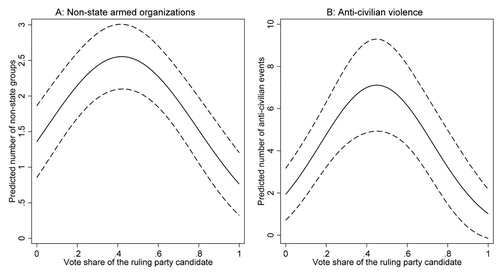

presents the results of statistical analysis on the impact of electoral support on four distinct types of violence. Models 1 and 2 include a combination of the linear and squared terms of to capture the logic of elite competition, according to which swing regions of the legislative election are most prone to violence by non-state armed actors. In model 1, there is a significant and positive coefficient on the linear term and a significant and negative coefficient on the squared term, suggesting that swing regions tend to have higher numbers of non-state armed organizations than core or costly regions. Model 2 shows very similar results as model 1: the estimates for

and

squared suggest an inverted U-shaped relationship between the vote share of the ruling party-endorsed candidates and violence against civilians. These results provide strong support for H1 that the risk of elite infighting is substantially higher for swing regions where competition for legislative seats (or gatekeeper positions) is most intense.

Table 2. Results of the poisson regression for african political violence.

(A), which is based on model 1, describes the predicted number of active non-state armed organizations as a function of , holding all other control variables at their median values. The curvilinear relationship between legislative support and non-state armed activity emerges clearly. The expected number of non-state armed groups is about 2.5 when the vote share received by the ruling party’s candidate is around 40-45%. This number drops to 1.5 or below when vote share is less than 5% or more than 80%. This result suggests that electoral competition between subnational elites gives rise to violent competition between non-state armed actors hired by elites. (B) also shows a curvilinear relationship between the ruling party candidate’s vote share and anti-civilian violence. The estimated inverted U-curve is almost symmetrical, with the apex at a 47% vote share (the swing zone), and regions that belong to “core” or “costly” zones are unlikely to experience anti-civilian violence.

Figure 3. Predicted numbers of non-state armed actors and anti-civilian events (with 95% confidence intervals) as a function of the ruling party’s vote share in legislative elections (Notes: All other variables are held at their median values. Random effects are set to zero.)

The analysis also supports our hypothesis on state violence, H2. According to our theory, state violence should be lowest in “core” areas by virtue of its patronage ties to the winning presidential candidate. Indeed, this is what we find. In model 3, the impact of is both negative and significant at the p=0.05 level. A unit increase in

is expected to decrease the number of state violence events by about 64.3%, holding all other factors constant.

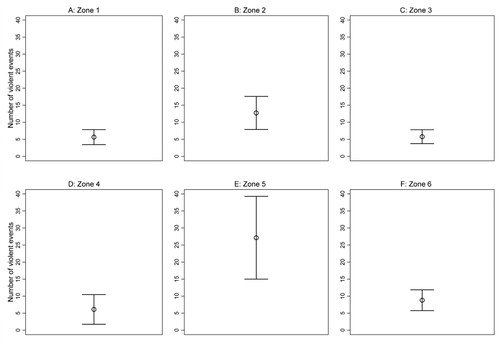

Finally, we test the effects of six zones of electoral support on the number of all reported violent events. In model 4, which include Zone 2–6 dummies as explanatory variables, the estimates for both Zone 2 and Zone 5 are positive and statistically distinguished from the baseline category (Zone 1), while Zone 5 demonstrates a stronger effect. , which is based on model 4, plots the predicted number of all violent events based on six electoral scenarios, holding all other variables at their median values. We observe a significant interaction between presidential and legislative election results at local levels: swing regions of the legislative election tend to have much higher numbers of violent incidents when support for the president was low. These results suggest that the effects of “swing” support for local candidates are especially pronounced in “costly” areas for the national winner, where state forces can be used to intimidate opposition supporters and/or punish poorly performing local intermediaries. Again, both of our hypotheses are powerfully confirmed.

Figure 4. Predicted number of all violent events (with 95% confidence intervals) as a function of six zones of regime support. (Notes: All other variables are held at their median values. Random effects are set to zero.)

Regarding the control variables, regions with larger Population tend to have higher numbers of violent acts across all event types. Past Violence has positive and significant effects on the number of non-state armed organizations and violence against civilians. The coefficient on Democracy has an unexpected positive sign and is significant in model 3. This may indicate that African leaders in young democracies are inclined to use violence to intimidate opposition groups.Footnote62 As expected, the impact of Party Control is both large and significant: all else equal, the less control a single party has over subnational authorities, the higher the risk of infighting within the party. In addition, Post-election Years after the last legislative election has significant, positive effects on the number of violent events. This suggests that competition between local intermediaries has a tendency to escalate over time during the inter-election period. Finally, Capital, New Power, Ethnic Heterogeneity and Post-election Years after the last presidential election do not exhibit significant or substantive effects on any type of violence.

Lastly, it is important to acknowledge that these results come with an important caveat. Our efforts to measure violent competition between local elites were conducted with event data on militia activities. Thus, while we argue that “swing” support begets more competition within the party, our research design cannot rule out the possibility that some of those militias were affiliated with opposition sides (e.g. opposition party, rebels, etc.). A limitation of this, and other studies of local violence, is that the affiliation of local militias can be quite obscure. Militias have variable identities and ties to political figures, including a shared local community, ethno-regional affiliation, political party, or party factions.Footnote63 Also, a prolific number of militias uncovered in swing districts are likely to be associated with their patron-politician first, and the political party second. We hope that future research will fill this gap by utilizing more detailed information on militia identities.

Conclusion and discussion

This article builds on the practical realities in competitive authoritarian states where leaders are dependent on local party elites to return sufficient evidence of their legitimacy, popularity and dominance. But how do leaders assess local alignment, and how do parties react to evidence of mal-alignment? Both presidential and legislative election results allow leaders to routinely assess how dependent and aligned local and regional intermediaries are. Regimes choose intermediaries as clients where access to exclusive patronage is exchanged for sustained support and votes. In turn, local intermediaries access patronage to continue their “gatekeeping” role. Election results demonstrate the effectiveness of this relationship, and recast a state’s political geography as composed of “core” zones where regime strength is positively aligned and the margins of support are high; “costly”, where neither national nor local support is in favour of the regime; or “swing” zones where local or regional support is marginal, or insufficiently loyal to secure a majority. The designation of these zones is pivotal to the functioning of authoritarian regimes: leaders are dependent on subnational support to secure national majorities, which both stabilizes and legitimizes their rule.

We further confirm that violence between elections is shaped by this political geography of national-subnational alignment. Our key finding is that swing areas of support are more likely to experience an increase of competitive non-state violence between election periods. Inconsistent and poor alignment with national election winners places local gatekeepers in a dangerous position as it nullifies their access to the centre and their claim to gatekeeping. In turn, this invites more competition from within the party to replace a poorly performing intermediary or representative.

There is a distinct logic to the political violence that occurs in competitive autocracies and hybrid states. Conflict in these states is rarely a contest between a group(s) challenging the authority of the state and a government, and much more often the work of political militias hired and directed by political elites to contest the terms of inclusion.Footnote64 The logic on conflict in these states is to use non-state groups to alter the political playing field to increase the competitiveness of select elites – it is not to replace or challenge the government.

This article also reinforces that we must focus on the political management practices inherent in leading a competitive autocracy.Footnote65 These practices are rarely predetermined based on identity,Footnote66 and instead are a function of the mutually beneficial clientelist relationship between leader and local intermediaries. A deeper investigation to the parameters of these relationships, and their volatility, is the basis for our reassessment of the political geography of competitive authoritarian states. This article serves as an initial counter to the presumed territorial politics of African states as determined by “ungoverned” territory. Instead, regimes’ use of local and subnational authorities to project state power is a common and widespread practice. Subnational elites work in conjunction with national regimes to enforce national agendas and sustain support for elites, and in return, these elites secure local monopolies and get patronage. However, local support can and does vary in response to political competition, clientelism and crisis: it does not appear to vary according to local grievance, political platforms or ideology. Consequently, we suggest that the dynamic geography of support as determined by previous election results explains significant levels of competitive political violence that repeatedly occurs across African states.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hyun Jin Choi

Hyun Jin Choi, PhD (Michigan State University, 2012), is an associate professor in the department of political science at Kyung Hee University, Seoul. Professor Choi's research interests fall within the field of civil war, Sub-Saharan Africa, and international development. His articles have been published in numerous refereed journals, including Global Environmental Change, International Studies Quarterly, Comparative Politics, and Journal of Conflict Resolution.

Clionadh Raleigh

Clionadh Raleigh PhD (University of Colorado, 2007), is a professor of political violence and geography in the School of Global Studies at Sussex University, UK. She is the executive director of the ACLED project. Professor Raleigh's research interests are political violence patterns and metrics, political elites and their use of violence, and regime politics across Sub-Saharan Africa.

Notes

1 Koter, “King Makers.”

2 See Magaloni et al., “Clientelism and Portfolio Diversification.”

3 See Seeberg et al., “Candidate Nomination”; Reeder and Seeberg, “Fighting Your Friends?”

4 See Cederman et al., Inequality, Grievances, and Civil War.

5 Raleigh, “Political Hierarchies and Landscapes.”

6 See Blaydes, Elections and Distributive Politics.

7 See Bangura and Kovacs, “Competition, Uncertainty, and Violence,” Chap. 5; Koter, “King Makers.”

8 Diamond, “Thinking about Hybrid Regimes”; Schedler, “Elections without Democracy.”

9 Magaloni and Kricheli, “Political Order and One-Party Rule.”

10 de Kadt and Larreguy, “Agents of the Regime?”

11 North, et al., Violence and Social Orders; Tilly and Tarrow, Contentious Politics.

12 Chernykh et al., “Measuring Legislative Power.”

13 Osei, “Elites and Democracy in Ghana.”

14 Raleigh and Wigmore-Shepherd, “Elite Coalitions and Power Balance.”

15 Ibid.

16 Gandhi and Przeworski, “Authoritarian Institutions”; Acemoglu and Robinson, “A Theory of Political Transitions”; Boix, Democracy and Redistribution.

17 Magaloni and Kricheli, “Political Order and One-Party Rule”; Wintrobe, The Political Economy of Dictatorship.

18 See Keating, “Thirty Years of Territorial Politics.”

19 Koter, “King Makers”; Magaloni et al., “Clientelism and Portfolio Diversification.”

20 Bleck and van de Walle, Electoral Politics in Africa.

21 Rakner and van de Walle, “Opposition Weakness in Africa”; LeBas, From Protest to Parties; Koter, “King Makers.”

22 Corra and Willer. “The Gatekeeper”; Sidel, Capital, Coercion, and Crime.

23 Gibson, Boundary Control.

24 Boone and Wahman, “Rural Bias in African Electoral Systems.”

25 Blaydes, Elections and Distributive Politics.

26 Magaloni, “Credible Power-Sharing,” 717.

27 See note 26 above.

28 Haber, “Authoritarian Government.”

29 Kricheli, “Information Aggregation and Electoral Autocracies.”

30 Diaz-Cayeros et al., “Tragic Brilliance.”

31 See note 26 above.

32 Rauschenbach and Paula, “Intimidating Voters.”

33 Wahman and Goldring, “Pre-election Violence.”

34 This logic can be applied to countries in civil war where incumbents strategically displace disloyal populations in costly areas supporting the insurgent-backed party. See Steele, “Electing Displacement.”

35 Wahman, “Democratization and Electoral Turnovers.”

36 Azevedo-Harman, “Parliaments in Africa.”

37 Birch, Electoral Malpractice.

38 Boone, Political Topographies of the African State; Herbst, States and Power in Africa.

39 Wig and Tollefsen, “Local Institutional Quality.”

40 Raleigh, “Pragmatic and Promiscuous”; Raleigh, “Political Hierarchies and Landscapes.”

41 See Choi and Raleigh, “Dominant Forms of Conflict.”

42 Raleigh, “Pragmatic and Promiscuous.”

43 Raleigh et al., “Inclusive Conflict.”

44 Seeberg et al., “Candidate Nomination”; and Reeder and Seeberg, “Fighting Your Friends?”

45 The ACLED provides the list of non-state armed organization, together with the date and location of their conflict activities. This allows us to identify the number of active non-state actors in a specific region and year. For more information, see Raleigh et al., “Introducing ACLED.”

46 According to Raleigh, about 60% of all militia activities are directed against civilians. See Raleigh, “Pragmatic and Promiscuous,” 290.

47 African Elections Project (accessed January 10, 2020). http://www.africanelections.org/

48 Psephos: Adam Carr’s Election Archive (accessed January 10, 2020). http://psephos.adam-carr.net/

49 African Democracy Encyclopedia Project (accessed January 10, 2020). https://www.eisa.org/wep/wepindex.htm

50 These thirteen countries include Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Nigeria, Malawi, Zambia, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, South Africa, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Zimbabwe.

51 Notable difficulties arose in Zambia, Sierra Leone, Malawi, and Uganda. Zambia, Sierra Leone, and Malawi required a custom built regional map to accommodate the variation in districts over time. For Uganda, the 2015 governmental regional aggregation scheme was applied, despite the subnational regional boundaries being in almost constant flux.

52 In the rare circumstances where election results are available by constituency, the representatives that win in those elections do not provide a unique analysis unit. Consider Uganda’s constituency representatives as a case: it has 135 districts, but 238 constituency representatives, 112 district woman representatives, ten People’s Defense Force representatives, five youth representatives, etc. This means that even getting constituency maps would not result in a single gatekeeper that we could track.

53 Note that South Africa, which has a parliamentary cabinet system, does not hold presidential elections, while Uganda provides no legislative election data at the subnational level. See Table A1 in the online appendix for a complete list of elections used in the analysis.

54 Out of 27 presidential elections in the dataset, the incumbents won 22 (81.5%).

55 Gridded Population of the World (ver. 4)

56 The threshold of 100 violent events was selected based on the Akaike Information Criterion.

57 Marshall et al., Polity IV Project.

58 We test whether this logic of punishment (H2) holds among the smaller set of democratic countries. See Table A2 of the online appendix.

59 Coppedge et al., Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

60 We thank an anonymous reviewer for this insight.

61 Drazanova, Historic Index of Ethnic Fractionalization Dataset (HIEF).

62 Rauschenbach and Paula, “Intimidating Voters.”

63 Raleigh and Kishi, “Hired Guns.”

64 Raleigh, “Political Hierarchies and Landscapes.”

65 Morse, “The Era of Electoral Authoritarianism.”

66 See Koter, “King Makers.”

Bibliography

- Acemoglu, Daron, and James A Robinson. “A Theory of Political Transitions.” American Economic Review 91, no. 4 (2001): 938–963. doi:10.1257/aer.91.4.938.

- African Democracy Encyclopedia Project. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.eisa.org/wep/wepindex.htm.

- African Elections Project. Accessed January 10, 2020. http://www.africanelections.org/.

- Azevedo-Harman, Elisabete. “Parliaments in Africa: Representative Institutions in the Land of the ‘Big Man’.” Journal of Legislative Studies 17, no. 1 (2011): 65–85. doi:10.1080/13572334.2011.545180.

- Seeberg, Merete Bech, Michael Wahman, and Svend-Erik Skaaning. “Candidate Nomination, Intra-Party Democracy, and Election Violence in Africa.” Democratization 25, no. 6 (2018): 959–977. doi:10.1080/13510347.2017.1420057.

- Bangura, Ibrahim, and Mimmi Söderberg Kovacs. “Competition, Uncertainty, and Violence in Sierra Leone’s Swing District.” In Violence in African Elections: Between Democracy and Big Man Politics, edited by Mimmi Söderberg Kovacs, and Jesper Bjarnesen, Chapter 5. London: Zed Books, 2018.

- Birch, Sarah. Electoral Malpractice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Blaydes, Lisa. Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Bleck, Jaimie, and Nicolas van de Walle. Electoral Politics in Africa Since 1990: Continuity in Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Boix, Carles. Democracy and Redistribution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Boone, Catherine. Political Topographies of the African State : Territorial Authority and Institutional Choice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Boone, Catherine, and Michael Wahman. “Rural Bias in African Electoral Systems: Legacies of Unequal Representation in African Democracies.” Electoral Studies 40 (2015): 335–346. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2015.10.004.

- Cederman, Lars Erik, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, and Halvard Buhaug. Inequality, Grievances, and Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Chernykh, Svitlana, David Doyle, and Timothy J. Power. “Measuring Legislative Power: An Expert Reweighting of the Fish-Kroenig Parliamentary Powers Index.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 42, no. 2 (2017): 295–320. doi:10.1111/lsq.12154.

- Choi, Hyun Jin, and Clionadh Raleigh. “Dominant Forms of Conflict in Changing Political Systems.” International Studies Quarterly 59, no. 1 (2015): 158–171. doi:10.1111/isqu.12157.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. “V-Dem Dataset v10”. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project ([dataset]. Accessed November 25, 2020. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20.

- Corra, Mamadi, and David Willer. “The Gatekeeper.” Sociological Theory 20, no. 2 (2002): 180–207. doi:10.1111/1467-9558.00158.

- de Kadt, Daniel, and Horacio A. Larreguy. “Agents of the Regime? Traditional Leaders and Electoral Politics in South Africa.” Journal of Politics 80, no. 2 (2018): 382–399. doi:10.1086/694540.

- Diamond, Larry. “Thinking About Hybrid Regimes.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 2 (2002): 21–35. doi:10.1353/jod.2002.0025.

- Diaz-Cayeros, Alberto, Beatriz Magaloni, and Barry Weingast. “Tragic Brilliance: Equilibrium Party Hegemony in Mexico.” Working Paper, Hoover Institution, Stanford University, 2008.

- Drazanova, Lenka. “Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalization Dataset (HIEF)”. Harvard Dataverse ([dataset]. Accessed November 25, 2020. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/4JQRCL.

- Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski. “Authoritarian Institutions and the Survival of Autocrats.” Comparative Political Studies 40, no. 11 (2007): 1279–1301. doi:10.1177/0010414007305817.

- Gibson, Edward L. Boundary Control. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Gridded Population of the World. (ver. 4) (database; Accessed January 15, 2020). https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/collection/gpw-v4/sets/browse.

- Haber, Stephen. “Authoritarian Government.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Economy, edited by Donald A. Wittman, and Barry R. Weingast, 693–707. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Herbst, Jeffrey Ira. States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Keating, Michael. “Thirty Years of Territorial Politics.” West European Politics 31, no. 1-2 (2008): 60–81. doi:10.1080/01402380701833723.

- Koter, Dominika. “King Makers: Local Leaders and Ethnic Politics in Africa.” World Politics 65, no. 2 (2013): 187–232. doi:10.1017/S004388711300004X.

- Kricheli, Ruth. “Information Aggregation and Electoral Autocracies: An Information-Based Theory of Authoritarian Leaders’ Use of Elections.” Working Paper. Palto Alto, CA: Stanford University, 2008.

- LeBas, Adrienne. From Protest to Parties: Party-Building and Democratization in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Magaloni, Beatriz. “Credible Power-Sharing and the Longevity of Authoritarian Rule.” Comparative Political Studies 41, no. 4–5 (2008): 715–741. doi:10.1177/0010414007313124.

- Magaloni, Beatriz, Alberto Diaz-Cayeros, and Federico Estévez. “Clientelism and Portfolio Diversification: A Model of Electoral Investment with Applications to Mexico.” In Patrons, Clients and Policies: Patterns of Democratic Accountability and Political Competition, edited by Herbert Kitschelt, and Steven Wilkinson, 182–205. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Magaloni, Beatriz, and Ruth Kricheli. “Political Order and One-Party Rule.” Annual Review of Political Science 13 (2010): 123–143. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.031908.220529.

- Marshall, Monty, Keith Jaggers, and Ted Robert Gurr. “Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2010.” Center for Systemic Peace ([dataset]; Accessed January 15, 2020). http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm.

- Morse, Yonatan L. “The Era of Electoral Authoritarianism.” World Politics 64, no. 1 (2012): 161–198. doi:10.2307/41428375.

- North, Douglass C, John Joseph Wallis, and Barry R Weingast. Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Osei, Anja. “Elites and Democracy in Ghana: A Social Network Approach.” African Affairs 114, no. 457 (2015): 529–554. doi:10.1093/afraf/adv036.

- Psephos: Adam Carr’s Election Archive. Accessed January 10, 2020. http://psephos.adam-carr.net/.

- Rakner, Lise, and Nicolas van de Walle. “Opposition Weakness in Africa.” Journal of Democracy 20, no. 3 (2009): 108–121. doi:10.1353/jod.0.0096.

- Raleigh, Clionadh. “Political Hierarchies and Landscapes of Conflict Across Africa.” Political Geography 42, no. 1 (2016): 92–103. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.07.002.

- Raleigh, Clionadh. “Pragmatic and Promiscuous: Political Militias Across African States.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 60, no. 2 (2016): 283–310. doi:10.1177/0022002714540472.

- Raleigh, Clionadh, and Roudabeh Kishi. “Hired Guns: Using Pro-Government Militias for Political Competition.” Terrorism and Political Violence 32, no. 3 (2020): 582–603. doi:10.1080/09546553.2017.1388793.

- Raleigh, Clionadh, and Daniel Wigmore-Shepherd. “Elite Coalitions and Power Balance Across African Regimes: Introducing the African Cabinet and Political Elite Data Project (ACPED).” Ethnopolitics (2020). doi:10.1080/17449057.2020.1771840.

- Raleigh, Clionadh, Hyun Jin Choi, and Daniel Wigmore-Shepherd. “Inclusive Conflict? Competitive Clientelism and the Rise of Political Violence.” Under Review, University of Sussex, 2020.

- Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen. “Introducing ACLED: Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 651–660. doi:10.2307/20798933.

- Rauschenbach, Mascha, and Katrin Paula. “Intimidating Voters with Violence and Mobilizing Them with Clientelism.” Journal of Peace Research 56, no. 5 (2019): 682–696. doi:10.1177/0022343318822709.

- Reeder, Bryce W., and Merete Bech Seeberg. “Fighting Your Friends? A Study of Intra-Party Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Democratization 25, no. 6 (2018): 1033–1051. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1441291.

- Schedler, Andreas. “Elections Without Democracy: The Menu of Manipulation.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 2 (2002): 36–50. doi:10.1353/jod.2002.0031.

- Sidel, John. Capital, Coercion, and Crime: Bossism in the Philippines. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999.

- Steele, Abbey. “Electing Displacement: Political Cleansing in Apartado, Colombia.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55, no. 3 (2011): 423–445. doi:10.1177/0022002711400975.

- Tilly, Charles, and Sidney Tarrow. Contentious Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Wahman, Michael. “Democratization and Electoral Turnovers in Sub-Saharan Africa and Beyond.” Democratization 21, no. 2 (2014): 220–243. doi:10.1080/13510347.2012.732572.

- Wahman, Michael, and Edward Goldring. “Pre-election Violence and Territorial Control: Political Dominance and Subnational Election Violence in Polarized African Electoral Systems.” Journal of Peace Research 57, no. 1 (2020): 93–110. doi:10.1177/0022343319884990.

- Wig, Tore, and Andreas Forø Tollefsen. “Local Institutional Quality and Conflict Violence in Africa.” Political Geography 53 (2016): 30–42. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.01.003.

- Wintrobe, Ronald. The Political Economy of Dictatorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.