ABSTRACT

How do voters in consolidating democracies see electoral integrity? How does election affect the change in perception of electoral integrity among these voters? What role does winning play in seeing an election as free and fair? Building on the theory of the winner-loser gap, we answer these questions using original two-wave panel surveys we conducted before and after three parliamentary elections in Southeast Europe in 2018 and 2020. The article focuses on changes of perception of electoral integrity as a function of satisfaction with the electoral results in contexts where the quality of elections has always been at the centre of political conflict. We specifically explore the socialization effect of elections in environments with notoriously low trust in political institutions and high electoral stakes. The article goes beyond the “sore loser” hypothesis and examines voters’ both political preferences and personal characteristics potentially responsible for the change in perception of electoral integrity over the course of electoral cycle.

Introduction

Over the last 50 years elections have become an essential element in the process of consolidating power in various types of societies and political regimes.Footnote1 The change has happened together with rising awareness that electoral fairness and integrity is an integral part of a regime’s political legitimacy.Footnote2 Although most of the research concerning electoral integrity has focused on democratizing societies, where challenges of democratic transformation are most visible, recent difficulties in advanced democracies have highlighted the need for a more complex examination of electoral conduct and its acceptance by voters.Footnote3 The shift of agenda has shed light on a broader group of countries where democratic performance has been affected by advancing hybridization and rise of authoritarianism, putting many voters at odds with the authorities and elections they organize. Building on the theory of the winner-loser gap, this article focuses on changes of perception of electoral integrity as a function of satisfaction with the electoral results in contexts where the quality of elections has always been at the centre of political conflict. We specifically explore the socialization effect of elections in environments with notoriously low trust in political institutions and high electoral stakes. The article also goes beyond the “sore loser” hypothesis and examines voters’ both political preferences and personal characteristics potentially responsible for the change in perception of electoral integrity over the electoral cycle.

Although quality of elections has been in the scholarly spotlight for years, citizens’ perception of electoral integrity has started getting systematic attention only recently.Footnote4 This is the result of a still-dominant approach whereby the evaluations of international monitors and experts are valued more than those of the public.Footnote5 It is often argued that ordinary citizens lack the capacity to evaluate elections with any precision due to their insufficient knowledge, resulting in more skeptical and pessimistic assessments.Footnote6 We believe, however, that these evaluations should not be ignored as they represent important evidence on quality of democracy and electoral process.Footnote7 This is why our study draws attention to how citizens perceive the integrity of an election and how the occurrence of an election affects these perceptions.

To do so, we use data collected in two-wave panel surveys conducted before and after elections in three Southeast European states – Bosnia–Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia – to explore how subjective perceptions of electoral integrity evolve under elections that are dubbed less than perfect, taking into account the contextual specificities of Southeast Europe where political authorities often balance between democratic commitments and authoritarian tendencies.Footnote8 Acting as perfect examples of different developmental paths, elections in Southeast Europe embody multiple contextual characteristics relevant for both the post-communist context as well as for the more general paths of consolidation observed globally over the past decade. We specifically contribute to theory and empirical knowledge about the relationship between the perceptions of electoral integrity and its determinants on the level of individual voters.

The results of our analysis show that perception of electoral integrity in Bosnia–Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia is overwhelmingly negative, a finding that is neither surprising nor uncommon in the region of post-communist Europe. However, we also find that the mere experience of an election has a positive effect on the change of subjective perception of electoral integrity, potentially indicating an existence of a socialization effect identified in the literature predominantly focused on old democracies. We find this effect to be relevant for both voters and abstainers, with the effect among the former being significantly stronger. Our findings also show that people who report higher satisfaction with election results also evaluate electoral integrity more positively. Finally, we show that citizens do not become more trusting of elections by virtue of them being supporters of the incumbent candidates/parties. These findings are an important contribution to scholarship on elections in non-western contexts where electoral competition is traditionally seen as a source of political as well as civic frustration, yet cannot be called undemocratic.

Post-election perception of electoral integrity

Given that electoral fairness is important for the stability of a democratic regime, what factors affect its perception among voters? Mozaffar and SchedlerFootnote9 and PrzeworskiFootnote10 argue that procedural certainty is an important aspect of accepting uncertainty in outcomes, a prerequisite defining modern democracy. For that reason, maintaining the highest electoral integrity guarantees the indeterminacy of election outcomes while preserving the trust of the public in electoral institutions and, by extension, politics in general. Electoral integrity captures in this context the notion of international conventions and global norms, applying universally to all countries worldwide throughout the electoral cycle, including during the pre-electoral period, campaign, on polling day, and its aftermath.Footnote11 It refers to a perception of honesty and fairness of an election and it provides the legitimacy necessary to enable the elite to claim authority over a certain territory and period. Breaching electoral integrity causes a decline in feelings of trust in elected authorities, a lack of confidence in the fairness of electoral procedures and authorities, and skepticism about the honesty of the outcome.Footnote12 In other words, the macro-level of electoral integrity delimits the formal expectations about how elections should be conducted, while the micro-level of subjective perceptions of individuals tells us how the system meets these expectations. While electoral performance can be assessed using international standards, individual perception is highly subjective, often emotional, and prone to bias, yet highly insightful in terms of prevailing attitudes towards democracy and the electoral process.

The perception of an election’s fairness has been found to affect the levels of regime support and trust in governmentFootnote13 as well as the propensity to vote.Footnote14 A growing body of literature has also shown that election results can affect the ex-post assessment of the whole process,Footnote15 while certain personal predispositions might play an important role in the activation of tendencies for political distrust.Footnote16 The common denominator of these studies is that lack of trust in electoral institutions can erode citizens’ perceptions of the legitimacy of other political institutions and in some cases even spark civil unrest. NorrisFootnote17 argues that by reducing the feelings of political legitimacy, electoral malpractice exacerbates some of the underlying political grievances among losing parties, thereby fuelling popular protests that can turn into mass demonstrations.

In an opposite setting, if elections are conducted in accordance with international standards, the actual experience of casting a vote can further boost the legitimacy of the electoral process and improve the overall perception of electoral integrity. In general, it is common to argue that procedural quality of elections contributes to democratic legitimacy.Footnote18 Moreover, in established democracies voters share a basic level of political socialization which encourages seeing electoral procedures as fair in and of themselves.Footnote19 In this context, regardless of winning or losing, as well as witnessing procedural faults or shortcomings on election day, socialization processes may cause voters to see elections as routine events and to accept the results as legitimate.Footnote20

We expect that a similar mechanism might also exist in regimes where elections generally follow international standards but their integrity is systematically undermined by attempts to influence the outcome. Elections in such countries are still expected to have a socializing effect, as experiencing the agency of voting might prove that, despite its flaws, the system works. Efforts by those in power notwithstanding, the unhindered casting of one’s vote during an election can thus improve the perception of electoral integrity. The first logical corollary of this expectation is that we should see a general increase in people’s belief that elections are fairer when we compare those beliefs before and after an election (H1a). The second corollary is that this increase in the perception of electoral integrity should be greater for people who actually voted than for those who abstained (H1b).

When it comes to literature on electoral integrity, existing theories identify three different types of arguments explaining the change in its perception: partisan, contextual, and institutional/logistic.Footnote21 While partisan and contextual dimensions primarily focus on individual characteristics of voters like partisanship, ideology, and interest in politics on the one hand as well as income, race, or education on the other, contextual/logistic factors concern predominantly environmental and circumstantial aspects of elections (e.g. electoral system, presence of electoral monitors, efficacy of electoral management bodies [EMB]). As institutional/logistic factors are more common in comparative studies with a larger number of cases, we further explore partisan factors explaining the change in individual perceptions of electoral integrity while controlling for numerous contextual factors potentially relevant in the region of Southeast Europe.

The partisan dimension of trust in the electoral process builds on the theory of the winner-loser gap. This theory explains how the electoral outcome affects attitudes towards the political system,Footnote22 with its main expectation being that supporters of a losing party or a candidate are more likely to become more distrustful about the electoral process. The most plausible explanation for this tendency is that this is a form of compensation or rationalization for the gap between their preferred result and the actual outcome. Political victory on the other hand should boost the confidence in political institutions that allowed it.Footnote23 In general, the gap is expected to materialize on the basis of potential benefits that winning bestows on voters.

While research on winning parties and their perceptions of satisfaction, fairness, and efficacy has received wider attention,Footnote24 the losers’ part of the equation is less explored. Cantú and García-PonceFootnote25 in the context of Mexico theorize that the mechanism is more apparent among radical voters supporting candidates who challenge the system and among those supporting parties with no winning experience. While the latter are more likely to express distrust of elections because they face more uncertainty, the attitudes of the former are fuelled by their opposition to political status quo.Footnote26 BeaulieuFootnote27 in a similar fashion shows that rather than partisan ideology, an individual’s concern for fraud is shaped by a desire for their preferred candidate to win. Edelson et al.Footnote28 in their study on conspiracy theories find that after the election, partisans on the losing side are more likely to suspect fraud because they feel cheated. In general, as electoral competition creates winners and losers, it generates ambivalent attitudes toward authorities on the part of the losers.Footnote29 Unfortunately, most of these studies focus on systems with a majoritarian electoral system, in which winning and losing is often derived directly from the election results. The mechanism is far more complicated in proportional electoral systems, where election outcomes can create all sorts of winners and losers. While we believe the theoretical expectations coming from the identified winner-loser gap still hold, the winner/loser distinction becomes much more subjective in proportional systems. In response, we shift to voters’ own assessments of the degree to which they are on the winning or losing side. In line with the winner-loser logic, we expect that satisfaction with the election outcome results in an increased trust in the fairness and integrity of the electoral process as a whole (H2).

Assuming that voters can subjectively identify either as winners or losers, it is common to believe that they develop systematically different political attitudes.Footnote30 A long line of research has shown that voters choosing a party that becomes part of government are more likely to expect that the government is responsive to their needs, to feel like their vote made an impact on the political process, and subsequently to be supportive of the way the system works.Footnote31 As a result, people who voted for the current government are more likely to trust those in power in general and, by logical extension, trust how they organize the elections. Not doing so would mean holding two incompatible and dissonance inducing attitudes.Footnote32 Consequently, we expect the increase in electoral trust to be greater among government supporters than it is among those who supported the opposition (H3). To summarize, the existing literature guides us towards the following expectations on how an election changes trust in the electoral process. First, we expect trust in the integrity of the electoral process to increase after an election in general, and particularly for those who actually cast their ballot. Second, this increase is predicted to be conditional on the satisfaction with the election result, with those less satisfied with the outcome becoming less trustful of the process. Third and final, supporters of the incumbent government are expected to become more trusting of elections.

Context, data, and methods

Quality of the electoral process in the countries under study differs in many aspects embodying internal challenges coming from both institutional as well as political settings. Based on the Electoral Integrity Worldwide Report from May 2019Footnote33 the highest scoring country among the three is Croatia with the PEI IndexFootnote34 being 65. Serbia’s is 49 and Bosnia-Herzegovina’s is 46 (highest overall score is achieved by Denmark [86] while top countries in the CEE region are Estonia [79], Lithuania [78], and Slovenia [77]).

The OSCE/ODHIR (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe/Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights) final report on the 2018 general election in Bosnia–Herzegovina stated that although the elections were genuinely competitive they were characterized by continuing segmentation along ethnic lines. Most of the electoral campaign focused more on personal attacks and fearmongering than on discussing political alternatives. Together with uneven and biased coverage of local media as well as instances of pressure on voters and allegations of fraud, this negatively affected the overall atmosphere of the election.Footnote35 Despite this, the results were no different from any of the previous elections organized in Bosnia–Herzegovina. The electoral contests took place mainly among political parties within the same ethnic community preserving the institutionalized ethnic divisions created by the post-Dayton settlement. The lack of political vision and limited intra- and inter-ethnic co-operation caused a political impasse further deepening the existing stalemate among Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs on the federal revel.Footnote36

On the other hand, both parliamentary elections organized in Croatia and Serbia in 2020 were heavily affected by the global COVID-19 pandemic, its impact, and overall handling by the national governments. While the Croatian government led by the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) allegedly announced an early election on 7 July in order to capitalize on its successful management of the crisis,Footnote37 Serbia had to postpone its election from 25 April to 21 June further deepening the tense situation around the boycott of the election by a significant part of the opposition.Footnote38 While in Croatia the government argued that if the parliament went to full term, an election in late autumn would probably be hampered by a possible “second wave” of infections, in Serbia, the danger of infection was the reason for postponement of election in the early spring. In both cases, however, governments purportedly used the momentum for political campaigning that exploited the extraordinary situation.

The opposition in Croatia accused the HDZ-led government of capitalizing on the perceived successful management of the pandemic and of using the public appearances of key government officials strategically as part of the election campaign. For many parties the situation made it more difficult to convey their messages through regular face-to-face campaigning, relying mostly on social media and traditional broadcasting channels. Apart from traditional topics of Croatian politics (economy, corruption, civil rights, etc.), the campaign was particularly negative towards Croatia’s Serb minority which has increasingly become the target of inflammatory political rhetoric and hate speech fuelled by the right-wing nationalist Homeland Movement.

In Serbia, the campaign was dominated by President Aleksandar Vučić and his Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) who have been continuously criticized for an authoritarian style of governance and persistent breaches of parliamentary procedures, absence of a meaningful legislative debate, no oversight over the executive, and a tight grip over the election administration.Footnote39 Majority of opposition parties boycotting parliament sessions at least since early 2019, decided to continue with the boycott in the upcoming election calling for protests denouncing democratic backsliding and the opposition’s lack of access to the media. Political opposition sought to reframe the campaign and elections in general as a choice between granting and denying legitimacy to the process.Footnote40 The impact of peaceful protests on election results and their initial acceptance was minimal. Their legacy was however hampered by tension that escalated in the post-electoral period (July – August) with violent confrontation fuelled amid anger over the return of strict lockdown measures to tackle coronavirus.Footnote41

When it comes to results, both in Croatia and Serbia, the pandemic-affected elections were dominated by the incumbents. In Croatia, the HDZ managed to boost its popularity using the successful handling of the first wave of the pandemic and won the election with 37.22% of votes and 66 out of 151 seats. In Serbia, unsurprisingly, the coalition “For our Children” led by incumbent SNS won the election with 60.65% of votes and obtained 188 out of 250 seats totally dominating political landscape of the country. Both parties easily formed new governments, although Serbia, due to tensed situation, waited until late October for the official confirmation by the National Assembly. This is in stark contrast to the situation in Bosnia–Herzegovina where the new Chairman of the Council of Ministers (i.e. prime minister) was appointed after over a year of negotiations.

To assess the potential effects of these three elections on perceptions of election’s fairness, we analyse data from surveys we deployed in 2018 and 2020 via a dedicated mobile app and web platform.Footnote42 Respondents were surveyed twice, once before the elections, and once after election day ( summarizes the waves in the three countries). The goal was to cover the final stage of electoral campaigns as well as the immediate post-election dynamics when the salience of election-related issues is most prominent. Moreover, the moderate time window allows us to interpret the change in perception of electoral integrity as a function of election results while at least partially controlling for alternative societal explanations. Unfortunately, the survey in Serbia did not cover the July-August violent protests, which escalated after the survey was closed. Our data however show no indication of suspicious changes in perception of electoral integrity in the covered period supporting an interpretation that the unrest was fuelled amid anger over the return of strict lockdown measures to tackle coronavirus rather than purely election-driven frustration.Footnote43 In the end, data from a sample of 2285 respondents was collected: 760 from Bosnia–Herzegovina, 843 from Croatia, and 682 from Serbia.Footnote44 With the use of survey weights, the collected data are representative of their respective populations in terms of gender, age, and education.

Table 1. Summary of survey waves.

In this study, we rely on a quasi-experimental design in which the election and its outcome is the sole intervening variable effecting change in the attitudes of respondents towards electoral integrity. To support this assumption, we use Google trends for mapping the online environment to detect any alternative explanations tackling the potential observed changes in the second wave (see online Appendix, Figure A1). In each survey wave, respondents were asked on the Likert scale to which extent they agreed with nine statements on electoral integrity (see online Appendix, Table A1). A factor analysis revealed that eight of them relate to a single underlying concept.Footnote45 Therefore, after excluding the statement on journalists providing fair coverage of the election, and recoding the second, third, fourth, seventh, and eight statement (so that high values on all statements reflect high levels of trust), we take the sum of the responses to indicate respondents’ overall trust in the electoral process in each wave. The change in this trust is obtained by subtracting the trust in pre-electoral wave from the trust in the post-electoral wave. The result is a variable that is positive when people’s trust in elections grew over the course of the election, and negative when that trust declined. The change in trust is the key dependent variable in our analyses.

The first independent variable is Satisfaction with election outcome. This variable is derived directly from the survey via a question asking respondents how happy they were in general with results of the election on a 0–10 scale. We use this measure instead of alternative indicators such as the score of the party they voted for. First, proportional electoral systems used in the three countries often do not generate the clear winner/loser dichotomy we see in majoritarian systems.Footnote46 In addition, there are a myriad of reasons why people could be happy with an election result whereby the party they voted for did not win any additional seats or even lost a few. Furthermore, one’s satisfaction with the outcome is likely to be dependent on the performance of other parties as well. In short, we believe our approach to be the most encompassing measurement of election outcome satisfaction.Footnote47 The second main independent variable is Government supporter. This variable is based on a vote intention question in the pre-electoral wave of the survey. People who voted for a party that was part of the government at the time of the election are considered government supporters.Footnote48

In our analyses, we control first and foremost for the level of electoral trust in the pre-electoral wave. Obviously, the degree to which respondents’ trust in the electoral process could increase or decrease is dependent on how great that trust was to begin with. For instance, if a respondent was already completely trusting of the electoral process prior to the election, his or her increase in trust would be zero, regardless of the extent to which Hypothesis 1 holds. Controlling for pre-electoral trust in elections accounts for this instrumental variation in the dependent variable. The remaining control variables can be divided into two groups: political and socio-demographic covariates. In the former, political interest is the first, measured on a 0–10 self-placement scale. Karp et al.Footnote49 find that those with low levels of factual political knowledge are more likely to express doubts about the integrity of the system. As people more involved in politics should understand it better, we control for the fact that people with deeper interest in politics are better equipped to assess electoral integrity. The second and third political controls capture what we believe to be the two principal structuring policy dimensions in Southeast Europe. The first revolves around views on the role of the government in the economy and the redistribution of wealth, separating between liberals and socialists. The second is centred on the protection and cultivation of a national identity based on ethnic membership, and it separates cosmopolitans from nationalists.Footnote50 Both variables are measured by averaging respondents’ responses on five policy statements.

The fourth political control variable concerns exposure to news media. A significant body of literature focused on political distrust recognizes the relevance and quality of information channels as an important factor of receptiveness to reported electoral malpractice.Footnote51 To control for this possibility in Bosnia–Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia, we include a measure of news media exposure in our models. This measure is obtained by summing people’s responses on a 0–4 scale to five questions, which capture the degree to which they follow the news via newspapers, radio, television, information websites, and social media. The final political covariate captures whether a respondent voted or abstained in the election.

In terms of socio-demographics, we control for gender, age, income, employment status, being an ethnic minority, and level of education. Regarding the latter, we distinguish among three groups: lower educated voters only have an elementary school degree, middle educated voters are those who have finished their secondary education, and higher educated voters are those who have a graduate or university degree. The inclusion of these variables is necessitated by an extensive literature that finds trust in elections to be dependent on socio-economic factors. Dowling et al.Footnote52 find that poorer voters have lower trust in electoral process and are more prone to report violations concerning ballot secrecy. Alvarez et al.Footnote53 find significant difference in confidence existing along racial lines. Similar findings are presented by NorrisFootnote54 in the context of ethnic minorities and by Karpowitz et al.Footnote55 in the context of partisan minorities. In addition, because we pool data from the three countries in our analyses, we account for country-level differences by including country dummies. Finally, the models account for the time between the election and the participation in the post-electoral wave to control for differences induced by often rapidly evolving political events that follows an election. shows the descriptives of all variables.

Table 2. Descriptives of all variables.

Results

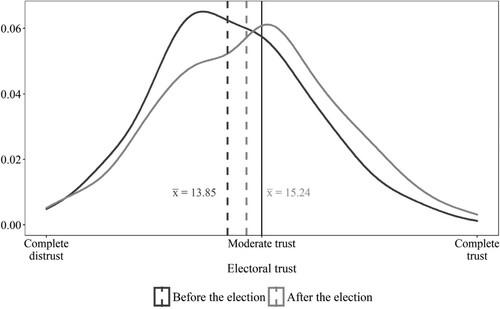

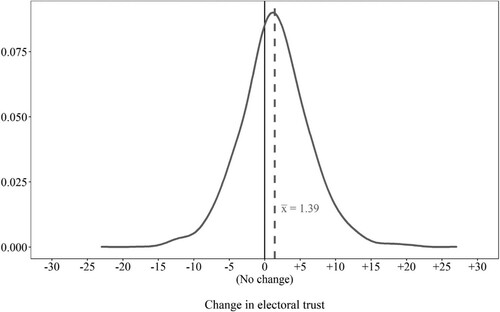

Before testing the effects of various explanatory variables in a multivariate model, we examine how trust in elections evolved between the pre- and post-electoral surveys in and . is a density plot that shows the aggregate distributions of electoral trust in both waves of the opinion survey. From the graph, it is clear that in the three Southeast European countries, a majority of the public is generally distrustful of the electoral process, a finding that is in line with the Electoral Integrity Worldwide Report as well as the opinion of scholars studying the region. However, the average level of trust in elections is higher after the elections. shows a density plot of the dependent variable, Change in electoral trust, giving an overview of the evolutions in trust on the individual level. It shows that, on average, respondents become 1.39 points (dashed line) more trusting of elections on a 0–32 scale. Though small, the difference is statistically significant from 0 (t(2285) = 13.44, p < 0.001).

shows the changes in electoral trust in the various measures that make up the dependent variable. While we find that respondents’ attitudes towards all but one measure became significantly more trusting, there are differences. We can roughly divide the eight indicators of electoral integrity into two groups, by magnitude of change. The first consists of indicators that showed little change between the pre- and post-electoral survey. These include perceptions of the ability of opposition candidates to run in elections, whether election officials are fair, and whether voters are threatened with violence. The second group comprises of measures that showed a greater amount of change. These are perceptions related to the fairness of the vote count, the bribing of voters, favouritism towards the ruling party in TV news, the ability of rich people to buy elections, and whether elections offer people a genuine choice. Taken together, we believe the evidence supports hypothesis H1a.

Table 3. Overview of the evolution of electoral perception beliefs.

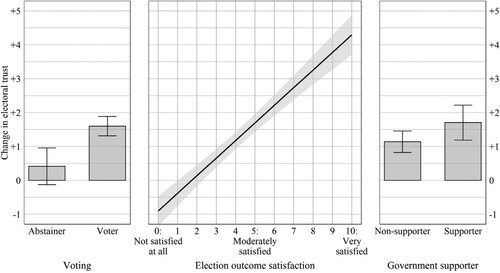

reports the multivariate models that seek to explain the degree to which people are becoming more or less trusting of elections. Model 1 includes only the key explanatory variables (voting in the election, satisfaction with election results, and government supporter) and controls solely for the most essential covariates: electoral trust before the election, country, and time between the election and the post-electoral wave of the survey. Models 2 and 3 test the robustness of Model 1 results by including the political and socio-demographic control variables, respectively. In other words, the models become increasingly stringent tests of hypotheses H1b, H2 and H3. All models show that voters differ significantly from abstainers when it comes to change in electoral trust. To make more sense of the positive coefficient, we plot the marginal effect in the left-hand panel of . Among those who went to the polling stations to cast their ballots, electoral trust increases by 1.6, while this is only 0.4 among those who did not go out to vote. In fact, the increase in electoral trust among abstainers is not significantly distinguishable from zero. Only when a respondent has actually gone through the steps of participating in the electoral process, do elections increase trust. The results thus support hypothesis H1b.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of the main explanatory variables change in electoral trust. Note: Predicted probabilities are based on the results of Model 3, Table 4; all other variables are kept at their mean value; the grey area represents the 95% confidence interval.

Table 4. Analyses of change in electoral trust.

All models also agree that satisfaction with the election outcome significantly affects one’s change in electoral trust. The coefficient is positive and highly significant, indicating that the greater one’s satisfaction with the election outcome, the greater one’s increase in trust in elections. Specifically, one standard deviation increase in election outcome satisfaction (3.49) results in a positive change of 1.81 in electoral trust (also see middle panel in ). This provides strong support for our second hypothesis (H2). The third hypothesis predicted that supporters of the government would become more trusting of elections due to the overall trust they have in the incumbent. The coefficient in all three models is positive, with government supporters becoming 1.7 points more trusting and non-supporters 1.14 points, but only statistically distinguishable from zero at p<0.10. Given the large sample size (n = 2285), we do not consider the evidence to sufficiently support H3, which we subsequently reject.

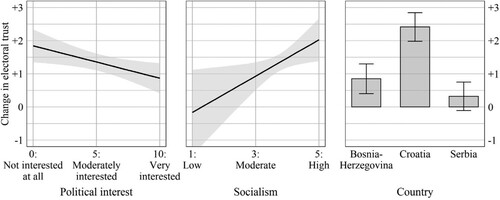

Looking at the control variables, Models 2 and 3 shows that political interest is negatively related to change in electoral trust. From the left-hand panel in , we see that politically uninterested respondents do not become more trusting of elections, in contrast to their more politically interested counterparts. While the effect reported for politically interested citizens is in line with the existing literature on political awareness, for others it might be a way of rationalization of why they did not cast their ballots. Socialist policy views are related to a greater increase in electoral trust (see middle panel in ). The change might be explained again by the socialization effect of election that might especially resonate among left-leaning voters. As the political left has a long tradition of support for the public sector and a strong state, people leaning left may trust the public administration more than those on the right do. In this context, left–right ideological dimension has been proven to act as an important factor in understanding attitudes towards public sector institutions among which the institute of election by extension belongs.Footnote56 As the agency of voting is virtually a manifestation of authorities’ ability to conduct elections, the experience of casting a ballot might activate the propensity to trust electoral integrity in the post-election period more than before election, hence affecting the overall positive change.

Figure 4. Marginal effects of the control variables on change in electoral trust. Note: Predicted probabilities are based on the results of Model 3, Table 4; all other variables are kept at their mean value; the grey area represents the 95% confidence interval.

Finally, the results suggest different levels of electoral trust change in the three countries (plotted in the right-hand panel in ). The largest (positive) change is observed in Croatia, whose respondents become almost 2.5 points more trusting of elections. By contrast, the increase in trust is a lot smaller in Bosnia–Herzegovina (0.84) and Serbia (0.32). In the latter case, this change is not even significantly different from zero. The most likely explanation is that Croatia is a more consolidated democracy than the other two countries, and the non-effect in Serbia is most likely due to the opposition boycott of its 2020 elections.

We must draw attention, however, to country-level heterogeneity in the effects of the key independent variables. When the analyses are repeated for each country separately (see Table A4 in online Appendix), we find that the effect of election outcome satisfaction is found in all three countries, though its effect is noticeably weaker in Croatia. The effect of having voted in the election, however, is corroborated only in Bosnia–Herzegovina and Serbia. This too might be a result from the fact that Croatia is a more consolidated democracy than the other two countries. This might have resulted in electoral trust being more resistant to electoral participation, and election result satisfaction. While we do not believe that these additional analyses undermine the mechanism behind electoral trust suggested here, they do indicate that there is country-level variation that needs to be explored. However, with only three countries here, this is an avenue we must let future research pursue.

Conclusion

Our motivation to study the perception of electoral integrity in Southeast Europe is driven by a disturbing global trend of growing distrust towards the electoral conduct in established democracies. The dynamics we observed in the United States 2020 presidential election have proven that perception of electoral integrity, no matter if biased or not, has a significant effect on the stability of a democratic system and its performance. If this is a serious challenge for the oldest democracy in the world, and we believe it is, what about countries that have a more complicated past? Most of the states of former Yugoslavia have been criticized for continuing authoritarization and rise of populism and extremism. Although the trend can be observed globally, recent history of major conflict makes it more severe in the region where elections embody the inherently conflicting winner-loser logic.

The findings we present in this article are enlightening in terms of better understanding of electoral process in Southeast Europe as well as similar contexts in general. We confirm (unsurprisingly) that voters in Bosnia–Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia are negative when it comes to the evaluation of electoral conduct. A more positive finding is the potential socializing effect of casting ballots on the perception of electoral integrity. In other words, we find that experiencing elections itself improves a generally poor assessment of electoral integrity which is an effect mostly discussed in the context of old democracies. It means that the socialization effect identified in old democracies is also relevant in countries with a comparatively short history of democratic elections and records of election misconduct. In addition, being a government supporter does not affect the propensity to change the election assessment to be more positive after the election. This means that incumbents’ supporters are well aware of the actual state of affairs in their countries regarding election, and that their judgement is not driven by their political preference but by the subjective evaluation of being on either the winning or losing side.

We believe these findings both develop the existing theoretical arguments on electoral integrity as well as broaden the empirical basis of comparative assessments. Although the paper does not make a claim that these results are simply transposable to all consolidating democracies, we believe that countries with similar transition paths might operate under the same mechanisms when it comes to changes of perception of electoral integrity over the course of election. In this context, Southeast Europe represents an interesting region with dynamic political arenas that are symptomatic of many polities in Europe as well as globally. In the near future, we can expect that individual perceptions of electoral integrity will become even more relevant and that they will be affecting the political stability in a wide range of political regimes. Understanding how perceptions of electoral integrity are formed and how they evolve is crucial for restoring general trust in the most fundamental institute on which modern democracies are based, especially in countries where quality of elections is inherently linked to quality of politics in general.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michal Mochtak

Michal Mochtak is a Post-doctoral Research Associate at the Institute of Political Science, University of Luxembourg. He focuses on the existing challenges to democracy in Central and Eastern Europe with a special emphasis on election-related conflicts, political violence, and modern forms of authoritarian rule. He is the author of “Electoral Violence in the Western Balkans: From Voting to Fighting and Back” (Abingdon, New York: Routledge). See more at www.mochtak.com.

Christophe Lesschaeve

Christophe Lesschaeve is a Post-doctoral Research Associate at the Institute of Political Science, University of Luxembourg. His research interests focus primarily on representation, issue congruence between voters and political elites, and voter behaviour. His most recent work focusses on how voters’ experiences of war and conflict affect their electoral behaviour and choices.

Josip Glaurdić

Josip Glaurdić is an Associate Professor of Political Science and Head of the Institute of Political Science at the University of Luxembourg. He is also Principal Investigator on the project Electoral Legacies of War (ELWar) funded by the European Research Council Starting Grant. He earned his PhD in political science (with distinction) from Yale University in 2009.

Notes

1 Posada Carbó, Elections before Democracy.

2 Norris, Why Electoral Integrity Matters; Birch, “Perceptions of Electoral Fairness and Voter Turnout.”

3 James, Elite Statecraft and Election Administration; Foley, Ballot Battles.

4 Coffé, “Citizens’ Media Use and the Accuracy of Their Perceptions of Electoral Integrity”; Flesken and Hartl, “Party Support, Values, and Perceptions of Electoral Integrity.”

5 Fisher and Sällberg, “Electoral Integrity – The Winner Takes It All? Evidence from Three British General Elections,” 405; Clark, “Identifying the Determinants of Electoral Integrity and Administration in Advanced Democracies,” 480; van Ham “Getting Elections Right?”.

6 Norris, Garnett, and Grömping, “Roswell, Grassy Knolls, and Voter Fraud Explaining Erroneous Perceptions of Electoral Malpractices,” 22.

7 Coffé, “Citizens’ Media Use and the Accuracy of Their Perceptions of Electoral Integrity,” 2; Norris, Garnett, and Grömping, “The Paranoid Style of American Elections.”

8 Bieber, “Patterns of Competitive Authoritarianism in the Western Balkans”; Bochsler and Juon, “Authoritarian Footprints in Central and Eastern Europe.”

9 Mozaffar and Schedler, “The Comparative Study of Electoral Governance - Introduction.”

10 Przeworski, “Democracy as the Contingent Outcome of Conflicts.”

11 Norris, Why Electoral Integrity Matters.

12 Birch, Electoral Malpractice; Daxecker, “The Cost of Exposing Cheating.”

13 Anderson and Tverdova, “Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes toward Government in Contemporary Democracies”; Bowler and Karp, “Politicians, Scandals, and Trust in Government”; Seligson, “The Impact of Corruption on Regime Legitimacy.”

14 Finkel, “Reciprocal Effects of Participation and Political Efficacy”; Karp and Banducci, “Political Efficacy and Participation in Twenty-Seven Democracies”; Norris, Democratic Phoenix.

15 Anderson et al., Losers’ Consent Elections Democ; Baron and Hershey, “Outcome Bias in Decision Evaluation.”

16 Alvarez, Hall, and Llewellyn, “Are Americans Confident Their Ballots Are Counted?”; Hooghe, Marien, and Pauwels, “Where Do Distrusting Voters Turn If There Is No Viable Exit or Voice Option?.”

17 Norris, Why Electoral Integrity Matters.

18 Birch, “Electoral Institutions and Popular Confidence in Electoral Processes.”

19 Bowler et al., “Election Administration and Perceptions of Fair Elections.”

20 Mozaffar and Schedler, “The Comparative Study of Electoral Governance - Introduction.”

21 Cantú and García-Ponce, “Partisan Losers’ Effects: Perceptions of Electoral Integrity in Mexico”; Kerr, “Popular Evaluations of Election Quality in Africa.”

22 Anderson et al., Losers’ Consent.

23 Anderson et al., 73–75.

24 Singh, Karakoç, and Blais, “Differentiating Winners: How Elections Affect Satisfaction with Democracy”; Moehler, “Critical Citizens and Submissive Subjects”; Anderson and Tverdova, “Winners, Losers, and Attitudes about Government in Contemporary Democracies.”

25 Cantú and García-Ponce, “Partisan Losers’ Effects.”

26 Magaloni, Voting for Autocracy; Anderson et al., Losers’ Consent.

27 Beaulieu, “From Voter ID to Party ID”

28 Edelson et al., “The Effect of Conspiratorial Thinking and Motivated Reasoning on Belief in Election Fraud.”

29 Kaase and Newton, Beliefs in Government; Nadeau and Blais, “Accepting the Election Outcome.”

30 Anderson and Tverdova, “Winners, Losers, and Attitudes about Government in Contemporary Democracies.”

31 Citrin and Green, “Presidential Leadership and the Resurgence of Trust in Government”; Kornberg and Clarke, “Beliefs About Democracy and Satisfaction with Democratic Government”; Nadeau and Blais, “Accepting the Election Outcome.”

32 Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.

33 Norris and Grömping, “Electoral Integrity Worldwide (PEI 7.0).”

34 Perception of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index is a cumulative indicator measuring international standards of electoral integrity. It is based on an expert survey that includes 49 key indicators clustered into 11 stages of the electoral cycle. The PEI index is standardized to 100 points. Norris, Frank, and Martínez i Coma, “Measuring Electoral Integrity around the World.”

35 OSCE, “Bosnia and Herzegovina, General Elections, 7 October 2018: Final Report.”

36 OSCE, 4–5, 14.

37 OSCE, “Croatia, Parliamentary Elections, 5 July 2020: Final Report.”

38 OSCE, “Special Election Assessment Mission in Serbia, 21 June 2020: Final Report.”

39 OSCE, “Special Election Assessment Mission in Serbia, 21 June 2020: Final Report.” 4–5.

40 OSCE, 12.

41 Dragojlo, “Serbia Rocked by Violent Clashes Around Parliament.”

42 We recruited survey participants using quota sampling through Facebook Marketing API. We identified 238 strata in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 252 in Croatia, and 350 in Serbia according to several demographic characteristics (gender, age, education, and region/county). Zhang et al., “Quota Sampling Using Facebook Advertisements.”

43 This interpretation can be supported also by the fact that the violent clashes are not mentioned in the OSCE monitoring report either. OSCE, “Special Election Assessment Mission in Serbia, 21 June 2020: Final Report.”

44 This sample was obtained after excluding 552 respondents who had given false answers, not responded to all questions, or filled in the survey too fast.

45 The factor analysis on the pooled sample was largely corroborated when performed on each country separately. Table A2 in online Appendix provides an overview of all factor analyses. In addition, Table A3 in online Appendix shows the results with all nine statements included. These results are highly similar to the ones reported below. Inevitably, there is variation between countries in how well each statements loads on the latent concept. However, a repetition of the analyses with only the five statements that have loadings higher than 0.4 in all countries, and in both waves, reported in Table A5 in online Appendix, showed no substantial difference in the results.

46 Anderson et al., Losers’ Consent; Cantú and García-Ponce, “Partisan Losers’ Effects: Perceptions of Electoral Integrity in Mexico.”

47 As a robustness check, we did conduct the analyses with a winner/loser dichotomy, whereby the winners are respondents who voted for future government parties, and losers are respondents who voted for future opposition parties. These results, which can be found in Table A6 in online Appendix, are in line with our hypothesis that satisfaction with the election outcome results in an increased trust in the fairness and integrity of the electoral process. It needs to be noted however, that the majoritarian logic is just an imperfect approximation of preferences, as voters in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia did not know which parties would form the government in the immediate post-election period, i.e. when we conducted the survey.

48 We acknowledge that the complexity of the Bosnia-Herzegovina political system and the fluid nature of some parties in Serbia offer alternative scientific venues that can be explored from different perspectives. However, in order to remain grounded in the comparativist tradition, we opt for the classical definition of incumbency and its implications. Armingeon et al. “Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2018.”

49 Karp, Nai, and Norris, “Dial F for Fraud.”

50 Massey, Hodson, and Sekulic, “Nationalism, Liberalism and Liberal Nationalism in Post-War Croatia.”

51 Fogarty et al., “News Attention to Voter Fraud in the 2008 and 2012 US Elections”; Karp, Nai, and Norris, “Dial F for Fraud”; Coffé, “Citizens’ Media Use and the Accuracy of Their Perceptions of Electoral Integrity.”

52 Dowling et al., “The Voting Experience and Beliefs about Ballot Secrecy.”

53 Alvarez, Hall, and Llewellyn, “Are Americans Confident Their Ballots Are Counted?”

54 Norris, Electoral Engineering.

55 Karpowitz et al., “Political Norms and the Private Act of Voting.”

56 Christensen and Lægreid, “Trust in Government”.

Bibliography

- Alvarez, R. Michael, Thad E. Hall, and Morgan H. Llewellyn. “Are Americans Confident Their Ballots Are Counted?” Journal of Politics 70, no. 3 (2008): 754–766.

- Anderson, Christopher J., André Blais, Shaun Bowler, Todd Donovan, and Ola Listhaug. Losers’ Consent: Elections and Democratic Legitimacy. Losers’ Consent: Elections and Democratic Legitimacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Yuliya V. Tverdova. “Winners, Losers, and Attitudes About Government in Contemporary Democracies.” International Political Science Review 22, no. 4 (2001): 321–338.

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Yuliya V. Tverdova. “Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes Toward Government in Contemporary Democracies.” American Journal of Political Science 47, no. 1 (2003): 91–109.

- Armingeon, Klaus, Sarah Engler, Lucas Leemann, et al. Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2018. Zurich: Institute of Political Science, University of Zurich, 2020.

- Baron, Jonathan, and John C. Hershey. “Outcome Bias in Decision Evaluation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54, no. 4 (1988): 569–579.

- Beaulieu, Emily. “From Voter ID to Party ID: How Political Parties Affect Perceptions of Election Fraud in the U.S.” Electoral Studies 35 (2014): 24–32.

- Bieber, Florian. “Patterns of Competitive Authoritarianism in the Western Balkans.” East European Politics 34, no. 3 (2018): 337–354.

- Birch, Sarah. “Electoral Institutions and Popular Confidence in Electoral Processes: A Cross-National Analysis.” Electoral Studies 27, no. 2 (January 2008): 305–320.

- Birch, Sarah. “Perceptions of Electoral Fairness and Voter Turnout.” Comparative Political Studies 43, no. 12 (2010): 1601–1622.

- Birch, Sarah. Electoral Malpractice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Bochsler, Daniel, and Andreas Juon. “Authoritarian Footprints in Central and Eastern Europe.” East European Politics 36, no. 2 (2020): 167–187.

- Bowler, Shaun, Thomas Brunell, Todd Donovan, and Paul Gronke. “Election Administration and Perceptions of Fair Elections.” Electoral Studies 38 (2015, June 1): 1–9.

- Bowler, Shaun, and Jeffrey A. Karp. “Politicians, Scandals, and Trust in Government.” Political Behavior 26, no. 3 (2004): 271–287.

- Cantú, Francisco, and Omar García-Ponce. “Partisan Losers’ Effects: Perceptions of Electoral Integrity in Mexico.” Electoral Studies 39 (2015): 1–14.

- Christensen, Tom, and Per Lægreid. “Trust in Government: The Relative Importance of Service Satisfaction, Political Factors, and Demography.” Public Performance & Management Review 28, no. 4 (2005): 487–511.

- Citrin, Jack, and Donald Philip Green. “Presidential Leadership and the Resurgence of Trust in Government.” British Journal of Political Science 16, no. 4 (1986): 431–453.

- Clark, Alistair. “Identifying the Determinants of Electoral Integrity and Administration in Advanced Democracies: The Case of Britain.” European Political Science Review 9, no. 3 (2017): 471–492.

- Coffé, Hilde. “Citizens’ Media Use and the Accuracy of Their Perceptions of Electoral Integrity.” International Political Science Review 38, no. 3 (2017): 281–297.

- Daxecker, Ursula E. “The Cost of Exposing Cheating.” Journal of Peace Research 49, no. 4 (2012, July 10): 503–516.

- Dowling, Conor M., David Doherty, Seth J. Hill, Alan S. Gerber, and Gregory A. Huber. “The Voting Experience and Beliefs About Ballot Secrecy.” Edited by Gregg R. Murray. PLOS ONE 14, no. 1 (2019): 1–14.

- Dragojlo, Sasa. “Serbia Rocked by Violent Clashes Around Parliament,” 2020. https://balkaninsight.com/2020/07/08/serbia-rocked-by-violent-clashes-around-parliament/.

- Edelson, Jack, Alexander Alduncin, Christopher Krewson, James A. Sieja, and Joseph E. Uscinski. “The MEffect of Conspiratorial Thinking and Motivated Reasoning on Belief in Election Fraud.” Political Research Quarterly 70, no. 4 (2017): 933–946.

- Festinger, Leon. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009.

- Finkel, Steven E. “Reciprocal Effects of Participation and Political Efficacy: A Panel Analysis.” American Journal of Political Science 29, no. 4 (1985): 913.

- Fisher, Justin, and Yohanna Sällberg. “Electoral Integrity – The Winner Takes It All? Evidence from Three British General Elections.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 22, no. 3 (2020): 404–420.

- Flesken, Anaïd, and Jakob Hartl. “Party Support, Values, and Perceptions of Electoral Integrity.” Political Psychology 39, no. 3 (2018): 707–724.

- Fogarty, Brian J, Jessica Curtis, Patricia Frances Gouzien, David C Kimball, and Eric C Vorst. “News Attention to Voter Fraud in the 2008 and 2012 US Elections.” Research & Politics 2, no. 2 (2015): 1–8.

- Foley, Edward. Ballot Battles: The History of Disputed Elections in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- van Ham, Carolien. “Getting Elections Right? Measuring Electoral Integrity.” Democratization 22, no. 4 (2015): 714–737.

- Hooghe, Marc, Sofie Marien, and Teun Pauwels. “Where Do Distrusting Voters Turn If There Is No Viable Exit or Voice Option? The Impact of Political Trust on Electoral Behaviour in the Belgian Regional Elections of June 2009.” Government and Opposition 46, no. 2 (2011): 245–273.

- James, Toby S. Elite Statecraft and Election Administration: Bending the Rules of the Game? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Kaase, Max, and Kenneth Newton, eds. Beliefs in Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Karp, Jeffrey A., and Susan A. Banducci. “Political Efficacy and Participation in Twenty-Seven Democracies: How Electoral Systems Shape Political Behaviour.” British Journal of Political Science 38, no. 2 (2008): 311–334.

- Karp, Jeffrey A., Alessandro Nai, and Pippa Norris. “Dial F for Fraud: Explaining Citizens Suspicions About Elections.” Electoral Studies 53 (2018): 11–19.

- Karpowitz, Christopher F., J. Quin Monson, Lindsay Nielson, Kelly D. Patterson, and Steven A. Snell. “Political Norms and the Private Act of Voting.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75, no. 4 (2011, January): 659–685.

- Kerr, Nicholas. “Popular Evaluations of Election Quality in Africa: Evidence from Nigeria.” Electoral Studies 32, no. 4 (2013): 819–837.

- Kornberg, Allan, and Harold D. Clarke. “Beliefs About Democracy and Satisfaction with Democratic Government: The Canadian Case.” Political Research Quarterly 47, no. 3 (1994): 537–563.

- Magaloni, Beatriz. Voting for Autocracy. Voting for Autocracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Massey, Garth, Randy Hodson, and Duško Sekulic. “Nationalism, Liberalism and Liberal Nationalism in Post-War Croatia.” Nations and Nationalism 9, no. 1 (2003): 55–82.

- Moehler, Devra C. “Critical Citizens and Submissive Subjects: Election Losers and Winners in Africa.” British Journal of Political Science 39, no. 2 (2009): 345–366.

- Mozaffar, Shaheen, and Andreas Schedler. “The Comparative Study of Electoral Governance - Introduction.” International Political Science Review 23, no. 1 (2002): 5–27.

- Nadeau, Richard, and André Blais. “Accepting the Election Outcome: The Effect of Participation on Losers’ Consent.” British Journal of Political Science 23, no. 4 (1993): 553–563.

- Norris, Pippa. Democratic Phoenix. Reinventing Political Activism. Democratic Phoenix. Cambdrige, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Norris, Pippa. Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Norris, Pippa. Why Electoral Integrity Matters. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Norris, Pippa, and Richard W. Frank and Ferran Martínez i Coma. “Measuring Electoral Integrity Around the World: A New Dataset.” PS - Political Science and Politics 47, no. 4 (2014): 789–798.

- Norris, Pippa, Holly Ann Garnett, and Max Grömping. “ Roswell, Grassy Knolls, and Voter Fraud. Explaining erroneous perceptions of electoral malpractices.” Paper presented at the Electoral Integrity Project Workshop ‘Protecting electoral security & voting rights: The 2016 U.S. elections in comparative perspective’, 1–44. San Francisco, CA, 30 August (2017).

- Norris, Pippa, Holly Ann Garnett, and Max Grömping. “The Paranoid Style of American Elections: Explaining Perceptions of Electoral Integrity in an Age of Populism.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 30, no. 1 (2020): 105–125.

- Norris, Pippa, and Max Grömping. “Electoral Integrity Worldwide (PEI 7.0).” Sydney, 2019.

- OSCE. “Bosnia and Herzegovina, General Elections, 7 October 2018: Final Report, “ 2019. https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/bih/409905.

- OSCE. “Croatia, Parliamentary Elections, 5 July 2020: Final Report,” 2020. https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/croatia/455209.

- OSCE. “Special Election Assessment Mission in Serbia, 21 June 2020: Final Report,” 2020. https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/serbia/parliamentary-elections-2020.

- Posada Carbó, Eduardo. Elections Before Democracy: The History of Elections in Europe and Latin America. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1996.

- Przeworski, Adam. “Democracy as the Contingent Outcome of Conflicts.” In Constitutionalism and Democracy, edited by Jon Elster, and Rune Slagstad, 59–80. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Seligson, Mitchell A. “The Impact of Corruption on Regime Legitimacy: A Comparative Study of Four Latin American Countries.” The Journal of Politics 64, no. 2 (2002): 408–433.

- Singh, Shane P., Ekrem Karakoç, and André Blais. “Differentiating Winners: How Elections Affect Satisfaction with Democracy.” Electoral Studies 31, no. 1 (2012): 201–211.

- Zhang, Baobao, Matto Mildenberger, Peter D. Howe, Jennifer Marlon, Seth A. Rosenthal, and Anthony Leiserowitz. “Quota Sampling Using Facebook Advertisements.” Political Science Research and Methods 8, no. 3 (2020): 558–564.