?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Populist leaders mobilize supporters to accomplish the political transformations they seek to achieve. However, once they are in office, populist leaders also encounter mobilizations against them because of their exclusionary rhetoric as well as their attack on existing democratic norms. These populists’ practices represent an erosion of (or threat to) political rights and move oppositional groups into struggle. Therefore, an increase in mobilizations under a populist leader can be seen as resistance to populism. Based on panel data analysis across 18 Latin American countries between 1990-2018, we find that populist rhetoric triggers a higher level of pro-democratic protests when it is combined with a populist leader’s rejection of democratic norms. The findings are discussed in line with the political consequences of populism in contemporary Latin America.

Populism is a resilient feature of the Latin American political landscape. Since the classical era of Latin American populism that emerged out of the Great Depression of the 1930s, populist candidates have repeatedly gained substantial political prominence wherever they were allowed to run for office. In recent years, and following the longest uninterrupted period of democracy in the region, several countries have witnessed the electoral success of a diverse group of populist candidates, representing both left- and right-leaning political forces.

A growing body of literature has sought to explain the transformation of populism in the wake of the region’s transition to market reformsFootnote1 as well as the causes of the recent populist resurgence.Footnote2 These works associate populism with a crisis of political representation following the turn to market reforms.Footnote3 Research has also begun to explore the political consequences of populism. While engaging previously underrepresented voters and potentially revitalizing democracy,Footnote4 populist leaders are also viewed as a source of democratic erosion (or backsliding) because they lead to declines in executive-legislative checks and balances,Footnote5 strategic manipulations of elections,Footnote6 greater government controls of mass media,Footnote7 and poor protection of minority rights.Footnote8

Building on these contributions, we shift attention to the social consequences of populism by examining the relationship between populism and mobilization.Footnote9 To date, existing research focuses on how populist leaders increase electoral turnout among supporters and political opponents,Footnote10 yet there is a little discussion about how populist leaders once in office also incentivize non-electoral participation. In 2019, for instance, protests reached a new high, when people around the world took to the streets to respond to democratic backsliding.Footnote11 However, it is unclear why widespread this opposition to populism is as protests appear in some countries or periods, but not in others. It also remains unknown what aspects of populism are more or less conducive to this resistance. Is it populist rhetoric? Is it populist attack on democratic norms? Or both? More importantly, what are the implications of this resistance for democratic backsliding?

We argue that populist leaders engender mobilizations against them for two reasons. First, populist rulers promote a political rhetoric that is exclusionary in its treatment of particular societal groups and people outside of the populist movement, in turn, resist the populist leader to protect their interests. Second, to advance their populist projects, populist rulers embrace policy initiatives and reforms that undermine democracy, and opposition groups also mobilize to defend existing democratic norms. These populists’ practices represent an erosion of (or threat to) political rights and create an opportunity for mobilization against populist leaders. These mobilizations can thus be viewed as resistance to populism.

To test this core argument, we examine the consequences of populist leaders on the level of protest in 18 Latin American countries between 1990–2018. We draw on data from the V-Party datasetFootnote12 to capture different dimensions of populism. We use data from the Mass Mobilization DataFootnote13 to capture the number of protests that demand democratic reforms in a particular year. Our empirical results show that populist rhetoric triggers a higher level of pro-democratic protests when it is combined with a populist leader’s rejection of democratic norms.

In the following section, we review the literature on the factors associated with populist resurgence and the political consequences of populism. Then, we introduce our central argument of how populist leaders incentivize mobilizations against them. The empirical section examines the relationship between populist leaders and mobilization using panel data for Latin America. After discussing our results, the conclusion explains the broader implications of our main findings.

Populist resurgence and their impact on democracy

Populism is a highly contested concept, and it will be difficult to talk about Latin America politics without mentioning populism. As RobertsFootnote14 writes, the concept has been used to describe a “broad range of empirical phenomena, from political regimes to parties, leadership styles, economic policies, and mobilization patterns.” In this article, we define populism following the ideational approach, which presents populism as a set of ideas that divides politics and society as the struggle between “the people” and “the power block.”Footnote15 In this struggle, populist leaders claim to embody the unified will of the people and seek to restore popular sovereignty at all levels.Footnote16 Scholars following this ideational approach advance a similar understanding of populism, but tend to utilize various terms to describe the phenomenon, including a “political style,”Footnote17 a “discourse,”Footnote18 a “language,”Footnote19 an “appeal,”Footnote20 or a “thin ideology.”Footnote21 The emphasis is on ideas, rather than a set of actions.Footnote22 Research on populism based on this approach allows for cross-national comparisons, making contributions complementary and cumulative,Footnote23 rather than deterministic.Footnote24

Recent works have examined the factors that have contributed to the rise of populist leaders as well as political consequences of populism. Demand-side arguments about the rise of populism emphasize social discontent and focus on changing preferences and attitudes among voters. The social and economic costs of market policies were a threat to popular subjects, making voters more susceptible to embrace populist leaders who promised social justice.Footnote25 In contrast, supply-side arguments direct attention to the transformation of political actors and parties. The rise of populism in Latin America follows the convergence of mainstream parties towards the market model. This convergence created a deficit (or crisis) of political representation, which was occupied by political outsiders deploying radical political discourses.Footnote26

Some studies have emphasized the positive effects of populism on democracy. Populist leaders, for instance, may encourage the political engagement of previously underrepresented groups,Footnote27 as when they politicize grievances around inequality.Footnote28 In this article, we shift attention to a growing number of studies that suggest that populism may also undermine democracy.Footnote29 To elaborate, the antagonistic and irreconcilable nature of populist rhetoric (the people vs. the power block) is often directed against liberal democracy.Footnote30 Specifically, through the anchorage of populism in the imaginary concept of the ill-defined “the people,”Footnote31 populism excludes other parts of society that do not fit into the picture.Footnote32 By portraying “the people” as a homogeneous group, populist ideas also reject the social diversity inherent in liberal principles of democracy, including autonomous grassroots organizations. This inherent tension between populism and liberalism is the reason why populists are perceived to be a threat to democracy,Footnote33 and these threats are more acute in countries with weak democratic institutions.Footnote34

Scholars have further highlighted that populist ideas clash with another important principle of liberal democracy: horizontal accountability or executive-legislative checks and balances.Footnote35 In some countries, populist leaders face strong incentives to turn against established liberal democratic institutions, especially if these institutions hinder their political agenda to “refound the nation.”Footnote36 Described as “democratic backsliding,”Footnote37 populist leaders have led to a gradual erosion of democratic institutions, expanding executive power, and weakening checks and balances. Despite the growth of the literature examining the relationship between populism and democracy, the relationship between populism and mobilization warrants further scrutiny. The following section presents a novel argument portraying increasing mobilizations under populist leaders as resistance to populism.

Resistance to populism

Populist leaders mobilize people along grievances that divide society between “the people” and “the power block.”Footnote38 In Latin America, these grievances were closely associated with the implementation of market reforms in the 1990s.Footnote39 The reforms left various “social deficits”Footnote40 and contributed to the emergence of anti-austerity movements as well as the rise of oppositional party systems. In these contexts, populist rhetoric provided a considerable mobilizing potential by working as a collective action frame,Footnote41 encouraging both electoral and non-electoral forms of political participation.Footnote42 Once in office, and to gain political legitimacy, populist leaders encourage their supporters to mobilize through more direct channels including protests. Populists ultimately weaponize mobilization depending on the level of elite opposition to their populist projects.Footnote43

While previous studies focus on electoral turnout among supporters and political opponents of populist leaders,Footnote44 this article focuses on non-electoral participation. In keeping with the primary drivers of collective action,Footnote45 just as economic threats offer a powerful mobilizing force for populist leaders, their exclusionary rhetoric and attacks on existing democratic norms could be perceived as an erosion of (or threat to) political rights that move oppositional groups into struggle. We elaborate on these losses with examples from the region, and we draw on this information to formulate two central hypotheses.

First, populists actively organize supporters within their movements, but these organizations are based on insularity, as they do not promote solidarity with similar organizations in civil society.Footnote46 Populists do not value pluralism because they embrace the idea of the popular as a homogenous fusion of “the people.”Footnote47 Hence, populist leaders only allow groups to organize under organizations that are perceived as loyal to them. They exclude and repress the civil society groups that are in conflict with their own supporting movements. Thus, the exclusionary rhetoric and practices inherent in populist rhetoric would accelerate a division between pro-government (supporters of the populist leader) and anti-government (those who are excluded and oppose the populist leader) groups. This division represents a political threat and creates an opportunity for mobilization.

President Rafael Correa (2007–2017) of Ecuador is an illustrative example of this type of exclusionary rhetoric and practice. Correa used several strategies to tame the power of social movements conflicting with his government,Footnote48 and these efforts became more pronounced starting in 2014 when his third presidential term began.Footnote49 First, the government used the legal system to limit the civil and political rights of autonomous, grassroots social movements. To regulate civil society and NGOs, the government created legislation requiring all civil society organizations to register with the state. The government also targeted several peasant-indigenous activists, including the leaders representing the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), accusing them of terrorism for opposing the government’s policies over mineral extraction. Second, the government sought to isolate social movement leaders from their rank-and-file. Correa created parallel pro-government social organizations from the top-down. For instance, the Secretariat for the Peoples funded the Council for Afro-Ecuadorian Unity and this organization staged demonstrations supporting Correa in exchange for jobs.Footnote50 Competing anti- and pro-government organizations are examples of the mobilization and counter-mobilization trends under populist leaders, and emerge as a consequence of the exclusionary rhetoric and practices of populist leaders. Hence, our first hypothesis reads:

H1: The populist rhetoric used by the government increases the level of pro-democratic protests.

Returning to Ecuador, various civil society organizations, including indigenous groups, environmental movements, unions and students, orchestrated mass protests. In 2012, during the march for “water, life and the dignity of peoples,” thousands of people across the country challenged the government’s mineral extraction plans.Footnote54 In 2015, mobilizations intensified again when Correa proposed a new law related to inheritance; a law was widely perceived as a means for wealth redistribution.Footnote55 Protests changed from the rejection of specific policies to political claims related to “democracy,” “freedom of expression,” and “rejection of authoritarianism,” eventually forcing Correa to abandon his plans to stand for (his fourth) re-election in 2017.

A similar mobilization pattern can be found in Peru. In 1990, Peruvians elected Alberto Fujimori, a political outsider, to the presidency. Shortly after staging a self-coup in April 1992, Alberto Fujimori convoked a constitutional assembly to rewrite the country’s constitution. The new constitution centralized executive authority and also enabled Fujimori to run for reelection. In 1997, Fujimori’s party dismantled the Constitutional Tribunal because it opposed his plans to seek a second reelection. This event marked the beginning of a long-run and widespread political opposition to Fujimori. Between June and May of that year, students, labor unions, and opposition political parties organized demonstrations to defend the rule of law and express their disapproval of this measure. Like Ecuador, the early demands against re-election also transitioned to broad political claims: the defense of democratic values, the respect of the rule of law, and finally, a wholesale rejection of his regime – demonstrators began to label the government as a dictatorship.

The literature brands Correa as a radical populist and Fujimori as a neoliberal populist,Footnote56 yet both went to great lengths to reassert their mandates, while undermining liberal democratic principles of horizontal accountability. The counterreactions to these presidents are examples of resistance to populism. To be clear, not all populists attack existing democratic norms. Brazil’s former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, for instance, is often categorized as a populist,Footnote57 yet while in office, the Worker’s Party promoted greater civil society participation,Footnote58 elections were very competitive,Footnote59 and major violations of the rule of law were absent.

Thus, we hypothesize that populists who reject democratic norms engender a greater level of mobilization in defense of democracy. Hence, our second hypothesis reads:

H2: The populist rhetoric combined with the rejection of democratic norms by the government increases the level of pro-democratic protests.

Research design

Our article examines the variation in pro-democratic protests in relation to populism in the government.Footnote60 We rely on statistical evidence using cross-national time-series data from 18 Latin American countries between 1990–2018. Our sample includes neoliberal populists like Peru’s Alberto Fujimori and Argentina’s Carlos Menem, as well as radical populists like Ecuador’s Rafael Correa, Bolivia’s Evo Morales and Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez. The sample allows us to examine how the new wave of populist leaders after the region’s turn to market policies affects mobilization.

Variables and data

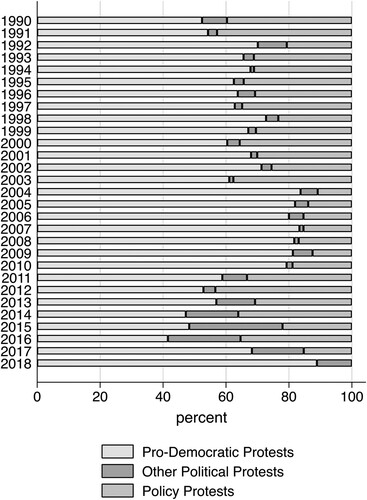

Our dependent variable is Protest, which consists of event counts representing the annual number of politically motivated anti-government (or anti-state) protests in a particular year. These anti-government protests come from organized opposition groups, such as labor unions, indigenous organizations, and opposition political parties. Thus, we see resistance to populism as functional to aggregate group responses, not individual behavior. The data are taken from the Mass Mobilization Data (MMD),Footnote61 which relies on news reports from international and national sources.Footnote62 MMD identifies several types of protests based on demands. Our dependent variable focuses on demands related to political behavior or processes (e.g., the political process that determines who rules and how, who can participate in elections or decisions), and we use these demands as a proxy for pro-democratic protests. We aggregate other types of protests for the purposes of secondary analysis. For instance, we consider policy protests based on demands related to (1) labor disputes, (2) land tenure or farm issues, and (3) price increases or tax policy. We also consider political protests associated with demands related to (1) police brutalities, (2) the removal of a corrupt politician, and (3) social restrictions in addition to (4) pro-democratic protests. presents the distribution of types of protests observed in Latin America between 1990–2018, showing that pro-democratic protests – our dependent variable – make up the bulk of protests in the region (ranging from 40% to 90%).

Figure 1. Protest Demands in Latin America (1990–2018). Note: Other political protests include protests against police brutalities, social restrictions, and corrupt politicians, but not pro-democratic protests. Policy protests indicate protests demanding specific policy changes.

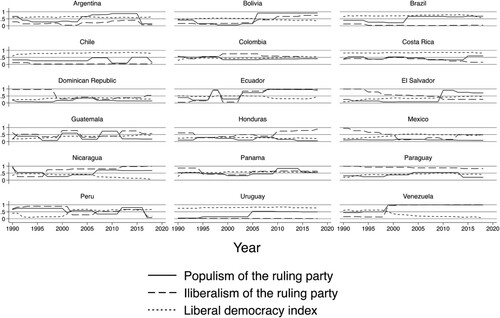

Our main independent variables seek to identify the dimensions of populism that are more (or less) conducive to mobilization. We draw on two indicators coded by country experts from the V-Party dataset: populism and illiberalism.Footnote63 Both indices are appropriate indicators for the characteristics of ruling parties across time and space. Populism index captures the extent to which the ruling party of the country-year draws on populist rhetoric (i.e., leaders refer to the “people” to describe ordinary citizens, and use anti-elite rhetoric as an important part of their party’s agenda), and this index is converted to a scale of 0–1. Hereafter, we call this variable Populist Rhetoric. Illiberalism records the extent to which ruling parties lack a commitment to democratic norms and this index is also converted to a scale of 0–1.Footnote64 As robustness check, and to go beyond the rejection of democratic norms, we consider a government’s implementation of illiberal policies. We use an inverse score of yearly change in the liberal democracy score from the V-Dem’s democracy index.Footnote65 Change in Illiberal Democracy captures the extent to which the country declined in liberal democracy, such as protecting individual rights against the tyranny of the state, compared to the previous year. We expect that a government that exhibits both high levels of Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism (or Change in Illiberal Democracy) will engender greater levels of mobilization. reveals considerable variation in these indices cross-nationally and within the country over time.

As shown by Brazil’s Lula, Illiberalism is not a unique or definitive characteristic of populism, as not all populists attack existing democratic norms.Footnote66 Following our central argument, the threat to political rights under a non-populist leader is also likely to encourage pro-democratic protests. Unfortunately, our sample of Latin America between 1990–2018 does not have enough cases of non-populist illiberal leaders to estimate their effects on protests. The 1990s was a period of growing democratization in Latin America. The recent declines in democracy can be traced to 2006, a period that more or less overlaps with the resurgence of populism in the region.

Our models take into account a number of control variables that may be important confounding factors in the relationship between populism and mobilization. First, we account for the ideological orientation (Left-Right) of the political party to which the head of the government belongs. We utilize the data from the V-Party dataset, measuring the party’s ideological stance on economic issues between -3.5 (far-left) to 3.5 (far-right).Footnote67 This is the ideology of the political party in office, not the ideology of the populist leader. Based on prior research,Footnote68 we expect that leftist parties are likely to mobilize when they are in opposition, but demobilize when they are in office. As such, mobilization will be higher when a right-wing party is in charge of the government.Footnote69

Second, we control for the other major driver of mobilization – opportunities – by taking into account several variables related to political processes.Footnote70 We first consider the level of Electoral Democracy. We use the V-Dem’s electoral democracy index, which measures the quality of electoral democracy, converted to a scale of 0–1.Footnote71 The electoral democracy index measures to what extent is electoral democracy achieved. We use this variable to control for the opportunity of mobilization, particularly when elections have irregularities.Footnote72 This variable helps us to separate the effects of populism from its political consequences.

We also consider a number of institutional explanations, such as party fragmentation and the electoral cycle. We first utilize the effective number of parties (ENP), a commonly used indicator of party fragmentation.Footnote73 Higher levels of fragmentation indicate smaller and weaker parties, and this low quality of party representation is likely to be associated with greater mobilization. In addition, we control for the electoral cycle as populists typically engage in “permanent political campaigns.”Footnote74 Since we are interested in the effect of populist leaders on mobilization, we control for years since the last presidential elections (Years after Election). As a robustness check, we include dummy variables indicating Election Year, Year before Election, and Election after Year, instead of this time trend variable.

Third, we consider various socio-economic control variables as research associates threats related to market reforms with an increase in mobilizationFootnote75 and support for populists.Footnote76 GDP per capita is a proxy for income wealth and is measured as the natural log of GDP per capita in constant US$ 2010 dollars. GDP growth rate is an indicator of economic performance calculated as the annual percentage change in GDP. Unemployment rate is another indicator of short-term economic performance. We expect that protest will rise during periods of downward turns and high unemployment. Because countries with larger populations may be more protest prone, we include the variable Population, which is the natural log of the total population. Each variable is lagged one year and comes from WDI.Footnote77

Lastly, we account for the potential spatial dependence of protest activity. Protests follow a cyclical pattern in which waves of protests spread rapidly across regions and then recede in the same manner.Footnote78 To control the spatial dependence of protests, we include the variable Level of Regional Protests, the mean level of protests throughout the sample in a given year.

In the Appendix, Table A1 provides descriptive statistics of our variables. Table A2 shows the list of ruling parties between 1990–2018 and their average indices of the V-party’s populist rhetoric and illiberalism.

Empirical strategy

To test the hypotheses, we first estimate the following model:

(1)

(1) Where i indexes country and t indexes time (year of the sample). Populism is a main independent variable capturing different dimensions of populism: Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism. Xi,t-i is a vector of time-by-country factors. To estimate the relationship between populism and mobilization, we utilize a negative binomial event count model. Event count models use maximum likelihood estimation to assess the probability of event occurrences. As event counts always take on nonnegative integer values, the distribution of events is skewed and discrete, producing errors that are not normally distributed or homoscedastic.Footnote79 Overdispersion and goodness-of-fit tests indicated that a negative binomial model is the best estimation method for our data.Footnote80 Since we use panel data, we have taken a number of measures to account for different forms of estimation error. First, we use robust standard errors clustered by presidencies to account for heteroskedasticity as well as autocorrelation. We also account for estimated unobservable unit-specific effects by using the country random effects model.Footnote81 Finally, to control for the temporal dependence of protest activity, we include the lagged dependent variable protestt-1.Footnote82

To test the second hypothesis, we examine the joint effects of populist rhetoric and illiberalism. We interact Populist Rhetoric with Illiberalism to test if their effects are inter-dependent. We estimate the following model:

(2)

(2) Where i indexes country and t indexes time. Xi,t-i is a vector of time-by-country factors. We expect that

to be positive, as we hypothesize that Populist Rhetoric increases pro-democratic protests when it is combined with Illiberalism.

Results

presents our main results. Models 1–3 show the individual effects of Populist Rhetoric (Models 1–2) and Illiberalism (Models 3–4) on pro-democratic protests. The effect of Populist Rhetoric on protests is negative, but not statistically significant in Model 1 (Random Effects, RE) or Model 2 (Lagged Dependent Variable, LDV). The effect of Illiberalism is positive, but also not statistically significant in Model 3 (RE) or Model 4 (LDV). Thus, the results indicate that neither Populist Rhetoric nor Illiberalism have an independent effect on pro-democratic protests.

Table 1. The effects of populism on protests.

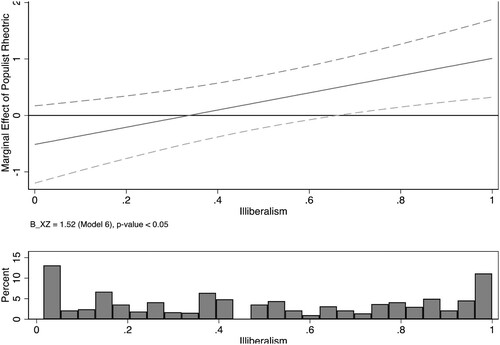

Models 5–6 present the joint effects of Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism. The results are consistent in Model 5 (RE) and Model 6 (LDV) as the interaction term between Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism is positive and statistically significant at high confidence levels in both models. The constituent term for Populist Rhetoric is negative but only statistically significant in Model 6 (LDV). Thus, the effect of Populist Rhetoric on protests when Illiberalism is 0 is inconclusive. In addition, the constituent term for Illiberalism is not statistically significant in both models. Thus, Populist Rhetoric does not affect the level of pro-democratic protests when political leaders do not draw on Illiberalism and vice versa. However, Illiberalism and Populist Rhetoric jointly engender pro-democratic protests. Footnote83

Next, we present how the marginal effect of Populist Rhetoric varies with the level of Illiberalism (). The marginal effect of Populist Rhetoric on pro-democratic protests becomes positive when the level of Illiberalism becomes higher than 0.6 on a 0–1 scale. Since the confidence intervals do not overlap each other, the difference is statistically significant at the 90% confidence level. Thus, populist rhetoric positively associates with pro-democratic protests only with higher levels of Illiberalism. To get a more intuitive understanding of the results, we use the statistical results of Model 6 to calculate the predicted number of pro-democratic protests. A high level of populist rhetoric (0.88) combined with a low level of illiberalism (0.03) predicts 1.25 pro-democratic protests per country-year. When a high level of populist rhetoric (0.88) is combined with a high level of illiberalism (0.93), however, we observe 2.64 pro-democratic protests. The difference of 1.39 is important.

Figure 3. Marginal Effect of Populist Rhetoric across Illiberalism. Note: Lines show the marginal effect of Populist Rhetoric contingent on the level of the Illiberalism (Model 6). Outer boundaries display the 90% confidence interval.

In sum, we did not find empirical support for the first hypothesis. We found more robust empirical support for the second hypothesis: pro-democratic protest increases when political leaders utilize both populist rhetoric and a clear rejection of democratic norms. The use of populist rhetoric or Illiberalism alone does not appear to increase or decrease protests.

Robustness check

In the Appendix, we ran several robustness tests to check the sensitivity of our results. These robustness tests add confidence to our results, while also indicating important scope conditions to the relationship between populism and protests.

First, we aggregate other types of protests as alternative dependent variables (Table A3). Models 1–2 shows the results of Political Protests. Although the interaction term between Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism is positive, it is statistically significant only in Model 2 (LDV). Thus, the joint effects of these two variables are more robust when we restrict our dependent variable to only pro-democratic protests (Models 5–6 of ). Models 3–4 consider Policy Protests. Across the models, the joint effect of Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism on policy protests is not statistically significant. The results are consistent with our central argument – an increase in mobilization is best understood as resistance to populism, not resistance to specific policies.

Second, we consider alternative measurements of populism and illiberalism (Tables A4 and A5). We use the data from the Global Populism Dataset (GPD) created by Hawkins et al. (2019). Hawkins et al. (2019) measure populism as the populist discourse utilized by political leaders (i.e., the head of the state). The GPD uses textual analysis of speeches of political leaders to assess the level of populist discourse.Footnote84 We operationalize the government’s level of populist discourse by averaging populism grades for each leader per term. Although Populist Discourse is positive in both models (Models 5–6 of Table A4), it is only statistically significant in Model 6 (LDV). The less robust finding from the models with the GPD measurement may be because the indicator does not distinguish different dimensions of populism: Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism.Footnote85 As the main models in indicate, populism only increases pro-democratic protests when both high levels of Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism are present.

Instead of using the ruling party’s scores, we employ the average values of populist scores for the parties in the government coalition (Table A5).Footnote86 In both Models 7 and 8, the interaction term between Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism is positive and statistically significant and the coefficients for the average scores for the government coalition are slightly larger than those of the main models (Models 5–6 of ). The results indicate a government coalition with greater capacity to shape illiberal policies, yielding a more substantial effect on pro-democratic protests.

We also considered the Implementation of Illiberal Policies in lieu of the ruling party’s scores. The interaction term between Populist Rhetoric and Change in Illiberal Democracy is positive in both Models 9 (RE) and 10 (LDV) of Table A6, but becomes statistically significant only in Model 9. This suggests that the combination of higher levels of populist rhetoric and Llliberal Democracy increases pro-democratic protests, and while better data are warranted to capture the actual Implementation of Illiberal Policies, these results are in line with our main findings (Models 5–6 of ).

Beyond alternative measures of protest, populism and illiberalism, we examined whether or not our results are driven by a handful of extreme cases (Table A7). We excluded cases categorized as radical populism (e.g., Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia) (Models 11–12), controlled for the square term of the ideology score (Models 13–14),Footnote87 and considered the effects of our variables by jackknifing each populist presidency (Models 15–16). The interaction term between Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism is positive and statistically significant in five of the six models,Footnote88 and support the generalizability of our results beyond these extreme cases.

We considered alternative ideological scales (Models 17–18 of Table A8). We used the left-right ideology scale of the government based on Arana Araya, Hughes, and Pérez-Liñán (2020). The measure is an average score of political parties’ ideology in Latin America, ranging from 1 (left) to 5 (right). Moreover, instead of controlling for the electoral cycle of presidential elections, we considered different operationalizations of election periods (Table A9), such as legislative elections (Models 19–20) and a dummy variable for the year after and year before the presidential elections (Models 21–22). Our main findings were robust to different operationalizations of ideology and election periods.

Finally, since a government’s strength to face popular resistance may affect the level of pro-democratic protests,Footnote89 we proxied government’s strength by taking into account the seats share of the government party (Models 23–24 of Table A10) and the seats share of government coalition (Models 25–26).Footnote90 These results were also supportive of our main findings.Footnote91

Conclusion

Populism is a resilient feature of the Latin American political landscape. In the past decade, several countries have witnessed the resurgence of politicians exhibiting the style, discourse, and mobilization strategies associated with the region’s enduring populist tradition. In this article, we have argued that while populist leaders mobilize their supporters to win office, once they are in power, groups outside the populist movement often counter-mobilize against them. Their exclusionary rhetoric against specific groups and lacking commitment to democratic norms are seen as an erosion of (or threat to) political rights, provoking resistance to populism. Our statistical results show that populist rhetoric engenders greater levels of mobilization only when it is combined with the rejection of democratic norms by the government.

A number of additional observations can be drawn from the present study. First, our findings have broad implications for studies of populism and democracyFootnote92 and discussions of preventing democratic decay under populism.Footnote93 Our empirical findings suggest that as populist leaders threaten democratic norms, civil society “talks back” in response to those threats. Pro-democracy protests, in particular, challenge populist’s attacks on democracy. This counterreaction to populism may help to stall democratic backsliding, but mobilizations may be insufficient to contain some of the heavy-handed strategies of populist leaders,Footnote94 as the Venezuelan experience shows. Electoral contestation remains equally important, and, if open and fair elections can be guaranteed, they too can help block populists’ ambitions.

Second, studies following the discourse approach to populism center on ideas or populist rhetoric, rather than a set of concrete actions.Footnote95 However, our study shows that research may need to go beyond populist ideas to adequately explore its larger political consequences. Illiberalism (or the rejection of democratic norms) is not a defining characteristic of populism, but the existing literature has increasingly acknowledged a tension between populism and liberalism,Footnote96 and this tension can be quite pronounced in democracies with weak institutions.Footnote97 Thus, to better capture the political consequences of populism, future research needs to pay closer attention to both what populists say and do while in office. Populist rhetoric may be easy, but populist actions can have far reaching political consequences on democratic norms and practices.

Future research should consider alternative sources of information to capture greater variation in the main variables of interest. In our analysis, the degree of populism and illiberalism are fixed by presidential terms and provide limited variation. This limitation makes it difficult to examine the varying political consequences of populist governments. Future research should also examine the relationship between populism and protests outside Latin America. Similar counterreaction trends can be found in Eastern Europe, including Poland and Hungary, where mass mobilization has increased under far-right populist ruling parties. The ideational approach to populism allows for these broad comparisons, and notwithstanding its limitations, it provides a starting point to study these political phenomena outside the land of populism—Latin America.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (88.4 KB)Acknowledgment

A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2021 Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association Conference, and research seminars at V-Dem and the Center for Inter-American Policy and Research (CIPR), Tulane University. The authors are thankful for the invaluable comments received on these occasions. The authors also would like to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful recommendations and suggestions.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yuko Sato

Yuko Sato is a postdoctoral fellow at the V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg. Her research focuses on popular protests, voting behavior, democratization, and autocratization, with a regional focus on Latin America. Her previous research has appeared in Electoral Studies and Democratization.

Moisés Arce

Moisés Arce is the Scott and Marjorie Cowen Chair in Latin American Social Sciences and Professor in the Department of Political Science at Tulane University. He specializes in conflict processes, state-society relations, and the politics of social and economic development. He is the author of Market Reform in Society (Penn State 2005), Resource Extraction and Protest in Peru (Pittsburgh 2014), and numerous journal articles and book chapters.

Notes

1 Roberts, “Neoliberalism and the Transformation of Populism in Latin America”; Weyland, “Neoliberal Populism in Latin America and Eastern Europe.”

2 Roberts “Populism, Political Mobilizations, and Crises of Political Representation”; Rovira Kaltwasser “Explaining the Emergence of Populism in Europe and the Americas”; Barr, The Resurgence of Populism in Latin America.

3 Roberts, “Latin America’s Populist Revival”; Roberts, “Populism, Political Mobilizations, and Crises of Political Representation”

4 E.g., Huber and Ruth, “Mind the Gap!”; Huber and Schimpf, “Friend or Foe?”; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Populism.

5 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding”; Diamond, “Democratic Regression in Comparative Perspective”; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser; “Populism and (liberal) Democracy”; Rovira Kaltwasser, “The Ambivalence of Populism”; Ruth, “Populism and the Erosion of Horizontal Accountability in Latin America.”

6 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding.”

7 Kenny, “The Enemy of the People.”

8 Roberts, “Populism, Democracy, and Resistance.”

9 The terms protest and mobilization are used interchangeably.

10 Rhodes-Purdy, Regime Support Beyond the Balance Sheet; Leininger and Meijers, “Do Populist Parties Increase Voter Turnout?”; Huber and Ruth, “Mind the Gap!”

11 Maerz et al., “State of the World 2019.”

12 Lührmann et al., “Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-Party) Dataset V1.”

13 Clark and Regan, “Mass Mobilization Protest Data.”

14 Roberts, “Latin America’s Populist revival,” 5.

15 de la Torre, “Populism in Latin America,” 2. For a critique of this approach, see Weyland, “A Political-Strategic Approach.”

16 Mudde, “The Populist Zeitgeist”; Mudde, Cas and Rovira Kaltwasser. Populism.

17 Knight, “Populism and Neo-Populism in Latin America, Especially Mexico.”

18 de la Torre, Populist Seduction in Latin America; Laclau, On Populist Reason.

19 Kazin, The Populist Persuasion.

20 Canovan, “Trust the People!”

21 Mudde, “The Populist Zeitgeist.”

22 Hawkins, “Is Chávez Populist?

23 Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, “Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective.”

24 Two other approaches defining populism include “political strategy” and “sociocultural,” Rovira Kaltwasser, “Populism and the Question of How to Respond to It.” Political strategy defines populism as an approach employed by a charismatic leader who seeks to govern based on unmediated support from their followers, e.g., Weyland, “A Political-Strategic Approach.” The sociocultural approach conceives populism as the folkloric style of politics used by leaders, breaking taboos to build a connection with the electorate, e.g., Ostiguy, “A Socio-Cultural Approach.” The approaches highlight specific features that might be relevant for some populists, and not others. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, “Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective.”

25 de la Torre, Populist Seduction in Latin America.

26 Doyle, “The Legitimacy of Political Institutions”; Roberts, Changing Course in Latin America; Lupu, Party Brands in Crisis.

27 See note 4 above.

28 Piñeiro, Rhodes-Purdy, and Rosenblatt, “The Engagement Curve.”

29 See note 5 above.

30 Liberal democracy is usually understood in terms of the rule of the majority, as expressed through free, fair, and competitive elections following Dahl’s “procedural minimal” or “polyarchy.” Dahl, Polyarchy. For a regime to be considered democratic today, however, it also must guarantee the rights of individuals and minorities through a written constitution. Thus, democracy is often called constitutional or liberal democracy. Plattner, “Democracy’s Past and Future”; Plattner, Democracy Without Borders? This latter tradition entails institutionalized competition across separate institutions mutually restraining and accountable to constituencies. In this article, we consider populists’ illiberalism as violations of three components of liberal democracy: (1) fair contestation or election, (2) protection of minority rights, and (3) institutional checks and balances.

31 See note 14 above.

32 de la Torre, “Populism in Latin America”; Rooduijn, “The Nucleus of Populism.”

33 Plattner, “Democracy’s Past and Future.”

34 Weyland, “Populism’s Threat to Democracy.”

35 See note 5 above.

36 de la Torre, Carlos. “Populism in Latin America,” 8.

37 See note 6 above.

38 Laclau, On Populist Reason.

39 Roberts, “Latin America’s Populist Revival.”

40 Bellinger and Arce, “Protest and Democracy in Latin America's Market Era.”

41 Mudde and Rovia Kaltwasser, “Populism and (Liberal) Democracy.”

42 Anduiza, Guinjoan, and Rico, “Populism, Participation, and Political Equality.”

43 Roberts, “Latin America’s Populist Revival.”; Rhodes-Purdy, Regime Support Beyond the Balance Sheet.

44 Leininger and Meijers, “Do Populist Parties Increase Voter Turnout?”; Huber and Ruth, “Mind the Gap!”

45 Tilly, From Mobilization to Revolution; Goldstone and Tilly, “Threat (and Opportunity).”

46 de la Torre, “Populism in Latin America.”

47 Avritzer, Democracy and the Public Space in Latin America.

48 de la Torre and Lemos, “Populist Polarization and the Slow Death of Democracy in Ecuador.”

49 Ortiz n.d., “El ciclo de protesta, 2007-2017.”

50 de la Torre and Sanchez, “The Afro-Ecuadorian Social Movement.”

51 de la Torre, “Populism in Latin America”; Roberts, “Populism, Democracy, and Resistance.”

52 de la Torre, “Populism in Latin America,” 8.

53 Previous studies have shown that fraudulent and undemocratic elections incentivize opposition groups to mobilize against the government. E.g., Brancati, Democracy Protests; Tucker, “Enough!” This is an example of the erosion of political rights that creates an incentive for mobilization.

54 See note 48 above.

55 Ibid.

56 See note 46 above.

57 E.g., Grigera, “Populism in Latin America.”

58 Hunter, The Transformation of the Workers’ Party in Brazil.

59 Power, “Brazilian Democracy as a Late Bloomer.”

60 Pro-regime (or pro-populist) mobilizations are not included in the dataset. Policy protests capture populist mobilization around economic inequality (or the so-called “engagement curve”). Piñeiro, Rhodes-Purdy, and Rosenblatt, “The Engagement Curve.”

61 See note 13 above.

62 The data relies on four primary sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Christian Science Monitor, and Times of London. It includes regional and other sources when international sources do not provide sufficient information.

63 See note 12 above.

64 The illiberalism index enables us to separate the “illiberal” aspect of political parties from other characteristics of parties, such as their radical ideology or use of populist rhetoric. The index also enables us to distinguish the characteristics of the government from their actual implementation of anti-democratic policies. The variable consists of questions in the expert survey that capture the four dimensions of party’s illiberalism: party leaders’ (1) lack of commitment to democratic process, (2) disrespect for fundamental minority rights, (3) demonization of opponents, and (4) acceptance of political violence. Among these four questions, two of them ask about the party’s commitment to democratic norms prior to elections. One possible concern is that the ruling party’s behavior after the election may change. However, a recent study demonstrated that a lack of commitment to democratic norms before the party reaches office is strongly correlated with its autocratic behavior after being elected. Lührmann, Medzihorsky, and Lindberg, “Walking the Talk.” The information about the government party reflects the ruling party on January 1 every year and are remain constant over their term in office.

65 Coppedge et al., “V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v11.1.”

66 The weak correlation between Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism (r=0.34) in our sample indicates that not all populists have an illiberal component in their discourses.

67 See note 12 above.

68 Arce and Mangonnet, “Competitiveness, Partisanship, and Subnational Protest in Argentina.”

69 Based on previous studies concerning the mediation effects of populist’s ideological orientation on political participation, we interacted populism indices with the ideology (Left-Right) of the ruling parties. E.g., Huber and Ruth, “Mind the Gap!” However, the interaction terms were not statistically significant, suggesting that the effect of populism on pro-democratic protest is not depending on populist’s ideology.

70 See note 45 above.

71 See note 65 above.

72 E.g., Brancati, Democracy Protests, Tucker, “Enough!”

73 The variable comes from the Quality of Government Institute. Teorell et al., The Quality of Government Standard Dataset.

74 de la Torre. “Populism in Latin America,” 8.

75 Brancati, “Pocketbook Protests.”

76 Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere.

77 World Bank, WDI.

78 Tarrow, Power in Movement.

79 Long, Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables.

80 Although one might expect that the zero-inflated negative binomial would be an ideal model, our dataset includes a dependent variable with non-zero values for 50% of observations. With this significant level of variation in the dependent variable, a negative binomial model is preferable.

81 Our independent variables, Populist Rhetoric and Illiberalism, contain limited variation across countries since they are coded based on the average populism scores for each ruling party per term. We use models with country random effects but not with country fixed effects, because the latter may wash out the effect of populist discourse.

82 Since including a lagged dependent variable in the random effects model is a violation of strict or contemporaneous exogeneity assumption, we include them in a separate model. Wooldridge, Introductory Econometric.

83 Our results are robust when we lag our main independent variables. The lag suggests that populism increases protests, and not the other way around. Our main findings do not change when including year fixed effects to account for time specific effects.

84 Hawkins et al., Global Populism Database.

85 GPD data includes the speech that justifies “nondemocratic means.” Hawkins, “Is Cávez Populist?,” 1064. By definition, GPD data contains the illiberalism dimension of populism.

86 To identify the parties in the government coalition, we used the V-Party’s Government Support variable. We included parties to which the head of government and one or more cabinet ministers belong as the parties within the government coalition.

87 The square term of the ideology score accounts for the possibility that the relationship between the ideology and protests is nonlinear, whereby radical ideologies lead to greater protest.

88 The interaction term for Model 15 (RE) is statistically insignificant. Because jackknifing methods work best for large-N data, this mixed finding may be explained by the limited variation in our variables over 111 presidencies.

89 E.g., Brancati, Democracy Protests.

90 The executive institutional strength represents stronger repression capacity. Pérez-Liñán, Schmidt, and Vairo, “Presidential Hegemony and Democratic Backsliding in Latin America.” The data of the government parties’ seat share was extracted from the V-Party dataset. We have interacted our main variables with their power in the legislature to see if the effects of Populism and Illiberalism on protests depend on executive institutional strength. We did not find any interactive effects. This null finding may be explained by the limited variation in our main variables over 111 presidencies. The varying effect of populists based on their executive institutional strength is worth investigating in future research with alternative data.

91 The interaction term for Model 25 (RE) is marginally statistically insignificant (p=0.19). This finding may be due to the limited variation of our key independent variables. Taking out more country specific effects make it difficult to find statistically significant effects.

92 See note 4 and 5 above.

93 E.g., Lührmann, “Disrupting the Autocratization Sequence”; Merkel and Lührmann, “Resilience of Democracies.”

94 On the ability of civil society to prevent democratic backsliding, see Mietzner, “Sources of Resistance to Democratic Decline.”

95 See note 22 above.

96 See note 5 above.

97 See note 34 above.

Bibliography

- Anduiza, Eva, Marc Guinjoan, and Guilem Rico. “Populism, Participation, and Political Equality.” European Political Science Review 11, no. 1 (2019): 109–124.

- Arana Araya, Ignacio, Melanie M. Hughes, and Aníbal Pérez-Liñán. “Judicial Reshuffles and Women Justices in Latin America.” American Journal of Political Science 65, no. no.,2 (2020): 373–388.

- Arce, Moisés, and Jorge Mangonnet. “Competitiveness, Partisanship, and Subnational Protest in Argentina.” Comparative Political Studies 46, no. 8 (2013): 895–919.

- Avritzer, Leonardo. Democracy and the Public Space in Latin America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Barr, Robert R. The Resurgence of Populism in Latin America. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2017.

- Bellinger, Paul T. and Moisés, Arce “Protest and Democracy in Latin America's Market Era.” Political Research Quarterly 64, no. 3 (2011): 688–704.

- Bermeo, Nancy. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27, no. 1 (2016): 5–19.

- Brancati, Dawn. “Pocketbook Protests.” Comparative Political Studies 47, no. 11 (2014): 1503–1530.

- Brancati, Dawn. Democracy Protests: Origins, Features and Significance. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Canovan, Margaret. “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47, no. 1 (1999): 2–16.

- Clark, David, and Patrick Regan. Mass Mobilization Protest Data. Harvard Dataverse: Cambridge, 2020.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, et al. “V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v11.1.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. 2021.

- Dahl, Robert A. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971.

- de la Torre, Carlos, and Andŕes Ortiz Lemos. “Populist Polarization and the Slow Death of Democracy in Ecuador.” Democratization 23, no. 2 (2016): 221–241.

- de la Torre, Carlos, Paul Taggart, and Pierre Ostiguy. “Populism in Latin America.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Crist'obal Rovira Kaltwasser, 195–213. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- de la Torre, Carlos. Populist Seduction in Latin America. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010.

- de la Torre, Carlos, and Jhon Antón Sánchez. “The Afro-Ecuadorian Social Movement.” In Black Social Movements in Latin America, edited by Jean Muteba Rahier, 135–150. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Diamond, Larry. “Democratic regression in comparative perspective: scope, methods, and causes.” Democratization 28, no. 1 (2021): 22–42.

- Doyle, David. “The Legitimacy of Political Institutions.” Comparative Political Studies 44, no. 11 (2011): 1447–1473.

- Goldstone, Jack, and Charles Tilly. “Threat (and Opportunity): Popular Action and State Response in the Dynamic of Contentious Action.” In Silence and Voice in the Study of Contentious Politics, edited by R. Aminzade, J. Goldstone, D. McAdam, E. Perry, W. Sewell, S. Tarrow, and C. Tilly, 179–194. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Goodhart, David. The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and The Future of Politics. London: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Grigera, Juan. “Populism in Latin America: Old and new populisms in Argentina and Brazil.” International Political Science Review 38, no. 4 (2017): 441–455.

- Hawkins, Kirk A. “Is Chávez Populist?.” Comparative Political Studies 42, no. 8 (2009): 1040–1067.

- Hawkins, Kirk A., Rosario Aguilar, Bruno Castanho Silva, Erin K. Jenne, Bojana Kocijan, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. Global Populism Database, v1. Harvard Dataverse: Cambridge, 2019.

- Robert, Huber A., and Christian H. Schimpf. “Friend or Foe? Testing the Influence of Populism on Democratic Quality in Latin America.” Political Studies 64, no. 4 (2016): 872–889.

- Robert, Huber, A., and Saskia P. Ruth. “Mind the Gap! Populism, Participation and Representation in Europe.” Swiss Political Science Review 23, no. 4 (2017): 462–484.

- Hunter, Wendy. The Transformation of the Workers’ Party in Brazil, 1989–2009. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Kazin, Michael. The Populist Persuasion: An American History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998.

- Kenny, Paul D. ““The Enemy of the People”: Populists and Press Freedom.” Political Research Quarterly 73, no. no.2 (2020): 261–275.

- Knight, Alan. “Populism and Neo-populism in Latin America, especially Mexico.” Journal of Latin American Studies 30, no. 2 (1998): 223–248.

- Laclau, Ernesto. On Populist Reason. London: Verso, 2005.

- Leininger, Arndt, and Maurits J. Meijers. “Do Populist Parties Increase Voter Turnout? Evidence From Over 40 Years of Electoral History in 31 European Democracies.” Political Studies 69, no. 3 (2021): 665–685.

- Long, J. Scott. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1997.

- Lührmann, Anna. “Disrupting the Autocratization Sequence: Towards Democratic Resilience.” Democratization 28, no. 5 (2021): 1017–1039.

- Lührmann, Anna, Juraj Medzihorsky, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “Walking the Talk: How to Identify Anti-Pluralist Parties.” V-Dem Working Paper 116 (2021.

- Lührmann, Anna, Nils Düpont, Masaaki Higashijima, et al. “Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-Party) Dataset v1.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project (2020.

- Lupu, Noam. Party Brands in Crisis: Partisanship, Brand Dilution, and the Breakdown of Political Parties in Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Maerz, Seraphine F, Anna Lührmann, Sebastian Hellmeier, Sandra Grahn, and Staffan I Lindberg. “State of the world 2019: autocratization surges – resistance grows.” Democratization 27, no. 6 (2020): 909–927.

- Merkel, Wolfgang, and Anna Lührmann. “Resilience of Democracies: Responses to Illiberal and Authoritarian Challenges.” Democratization 28, no. 5 (2021): 869–884.

- Mietzner, Marcus. “Sources of Resistance to Democratic Decline: Indonesian Civil Society and Its Trials.” Democratization 28, no. 1 (2021): 161–178.

- Mudde, Cas, and Crist'obal Rovira Kaltwasser. “Populism and (Liberal) Democracy: A Framework for Analysis.” In Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy?, edited by Cas Mudde, and Kaltwasser Crist'obal Rovira, 1–27. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Mudde, Cas, and Crist'obal Rovira Kaltwasser. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Mudde, Cas, and Crist'obal Rovira Kaltwasser. “Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective: Reflections on the Contemporary and Future Research Agenda.” Comparative Political Studies 51, no. 13 (2018): 1667–1693.

- Mudde, Cas. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39, no. 4 (2004): 541–563.

- Ortiz, Santiago. El ciclo de protesta, 2007-2017: Actores sociales y la Revolución Ciudadana en Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador: FLACSO, n.d.

- Ostiguy, Pierre. “A Socio-Cultural Approach.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by Paulina Ochoa Espejo, Crist'obal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, and Pierre Ostiguy, 73–97. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Pérez-Liñán, Aníbal, and Nicolás Schmidt and Daniela Vairo (2019) Presidential Hegemony and Democratic Backsliding in Latin America, 1925–2016, Democratization 26, no.4 (2019), 606-625. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1566321

- Piñeiro, Rafael, Matthew Rhodes-Purdy, and Fernando Rosenblatt. “The Engagement Curve: Populism and Political Engagement in Latin America.” Latin American Research Review 51, no. 4 (2016): 3–23.

- Plattner, Marc F. Democracy Without Borders? Global Challenges to Liberal Democracy. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2008.

- Plattner, Marc F. “Populism, Pluralism, and Liberal Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 21, no. 1 (2009): 81–92.

- Power, Timothy J. “Brazilian Democracy as a Late Bloomer: Reevaluating the Regime in the Cardoso-Lula Era.” Latin American Research Review 45 (2010): 218–247.

- Rhodes-Purdy, Matthew. Regime Support Beyond the Balance Sheet: Participation and Policy Performance in Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Roberts, Kenneth M. “Latin America’s Populist Revival.” SAIS Review of International Affairs 27, no. 1 (2007): 3–15.

- Roberts, Kenneth M. “Populism, Democracy, and Resistance.” In The Resistance: The Dawn of the Anti-Trump Opposition Movement, edited by David S. Meyer, and Sidney Tarrow, 54–72. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Roberts, Kenneth M. “Populism, Political Mobilizations, and Crises of Political Representation.” In The Promise and Perils of Populism: Global Perspectives, edited by Carlos de la Torre, 140–158. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2015.

- Roberts, Kenneth M. Changing Course in Latin America: Party Systems in the Neoliberal Era. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Roberts, Kenneth M. “Neoliberalism and the Transformation of Populism in Latin America: The Peruvian Case.” World politics 48, no. no.1 (1995): 82–116.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs. “The Nucleus of Populism: In Search of the Lowest Common Denominator.” Government and Opposition 49, no. 4 (2014): 573–599.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Crist'obal. “Explaining the Emergence of Populism in Europe and the Americas.” In The Promise and Perils of Populism: Global Perspectives, edited by Carlos de la Torre, 189–227. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2015.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Crist'obal. “The Ambivalence of Populism: Threat and Corrective for Democracy.” Democratization 19, no. 2 (2012): 184–208.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Crist'obal. “Populism and the Question of How to Respond to It.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by Paulina Ochoa Espejo Crist'obal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, and Pierre Ostiguy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Ruth, Saskia Pauline. “Populism and the Erosion of Horizontal Accountability in Latin America.” Political Studies 66, no. 2 (2018): 356–375.

- Tarrow, Sidney. Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Teorell, Jan, Aksel Sundström, Sören Holmberg, Bo Rothstein, and Natalia Alvarado Pachon adn Cem Mert Dalli. The Quality of Government Standard Dataset, version Jan20. The Quality of Government Institute, 2020.

- Tilly, Charles. From Mobilization to Revolution. Reading. Reading: Addison-Wesley, 1978.

- Joshua, Tucker A. “Enough! Electoral Fraud, Collective Action Problems, and Post-Communist Colored Revolutions.” Perspectives on Politics 5 (2007): 535–551.

- Weyland, Kurt. “A Political-Strategic Approach.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by Paulina Ochoa Espejo Crist'obal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, and Pierre Ostiguy, 48–73. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Weyland, Kurt. “Neoliberal Populism in Latin America and Eastern Europe.” Comparative Politics 31, no. 4 (1999): 379–401.

- Weyland, Kurt. “Populism’s Threat to Democracy: Comparative lessons for the United States.” Perspectives on Politics 18, no. 2 (2020): 389–406.

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. Boston: Cengage Learning, 2015.

- World Bank. WDI (World Development Indicators). Washington, DC: World Bank, 2020.