ABSTRACT

This article presents the state of democracy in the world in 2022 using the most recent Varieties of Democracy dataset (V13). There are four main findings. First, the level of democracy enjoyed by the average global citizen is down to 1986-levels and 72% of the world’s population live in autocracies. Second, the third wave of autocratization reaches a new height with 42 countries autocratizing. By contrast, only 14 countries are democratizing. Third, between 1992 and 2022, autocracies increased their share of the global economy and now account for 46% of world GDP when measured by purchasing power parity. Fourth, defying the global wave of autocratization, eight countries not only stopped but also reversed autocratization in the last 10 years, which we define as democratic U-turns. We find five elements that seem important across the identified cases: executive constraints, mass mobilization, alternation in power, unified opposition coalescing with civil society, and international democracy support. We analyze different combinations of these factors and discuss how they could be critical in stopping and reversing contemporary autocratization. This first analysis suggests that in-depth, comparative case studies of these eight cases and their counterfactuals would be an important area of future research.

Introduction

Based on this year’s release of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset version 13,Footnote1 we find that the third wave of autocratizationFootnote2 is reaching a new high in 2022. Core components of democracy such as freedom of expression and the media, freedom of association, and free and fair elections are all in decline across the world.

This article presents four primary findings. First, the global population-weighted average of democracy measured by the Liberal Democracy Index (LDI)Footnote3 is back to levels last seen in 1986. From the perspective of the average global citizen, democratic gains made over the last 35 years have been undone in the last decade. Many countries are better off today than in the mid-1980s but there are also those that are worse off, and almost 72% of the world’s population now live in autocracies, an increase from 46% in 2012.

Second, the worldwide wave of autocratization is intensifying and reached a new peak in 2022 with 42 autocratizing countries over the past decade, home to 43% of the world’s population. Meanwhile the 14 democratizing countries – a low not seen since 1973 – harbour only 2% of the world’s population.Footnote4

Third, autocracies are not only growing in numbers but also becoming more powerful economically. The share of world GDP generated by autocracies has been gradually increasing during the last decades and is now at 46% when measured by purchasing power parity, almost a doubling from 24% in 1992.

Fourth, and in defiance of the autocratization trend, we identify at least eight cases where autocratization was not only stopped but also reversed into substantial regains of democratic levels in the last 10 years: U-turns. Four of these cases (Slovenia, South Korea, Ecuador, and Moldova) managed to halt autocratization and regain the democratic losses incurred before democracy broke down, whereas the other four (North Macedonia, Bolivia, the Maldives, and Zambia) deteriorated into electoral autocracies before initiating a significant reversal back to democracy. We offer a novel analysis that identifies five elements that seem to have played important roles in the reversal across many or all the cases and their various contexts: constraints on the executive by an independent judiciary and sometimes the legislature, mass mobilization, alternation in power, unified opposition coalescing with civil society, and international democracy support and protection. Extending recent studies on democratic resilience,Footnote5 the analysis of these eight U-turn cases illustrates that contemporary autocratization can be stopped and reversed. The five elements identified by the analysis could be seen as prime suspects for stopping and reversing contemporary autocratization, but their causal impact would need to be corroborated in future research.

The first section below details the state of the world in 2022. This includes analysing changes in the LDI and the Regimes of the World (RoW)Footnote6 over time, as well as changes in the sub-indices and indicators making up the LDI, along with a novel examination of the share of world GDP across regime types. The second section focuses on democratization and autocratization, both in aggregate and with a focus on the top ten autocratizers and democratizers. In the third section, we introduce the eight U-turn cases and document elements that seem to have influenced the reversals and democratic resurgence. We conclude by discussing possible new research avenues on regime change.

Rolling back democracy to 1986

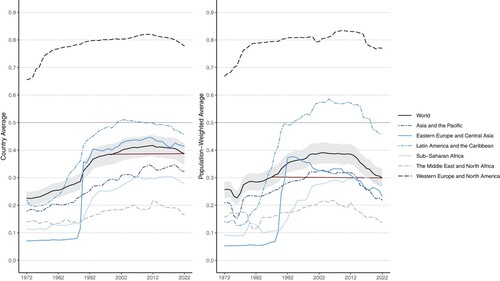

displays the world average as well as regional average levels of democracy based on the country averages (left panel) and the population-weighted averages (right panel). Both panels show the “third wave of democratization”Footnote7 peaking after the end of the Cold War, followed by a decline over the past ten to fifteen years. In 2022, the level of liberal democracy enjoyed by the average global citizen deteriorated to levels last seen in 1986, as shown by the black line in the right panel. The red line in the right panel traces the 2022 level of democracy back in time to show this. The left panel – based on country averages – shows that the global average level of democracy is back to the 1997-level. Since democracy is “rule by the people”, it arguably matters how many people are enjoying democratic rights and freedoms around the world. The population-weighted metric is therefore more indicative of the levels of democracy experienced by people worldwide than straight country averages. A country-average measure is also weighted – only giving equal weight to each government regardless of the size of its territory or the number of people. Both panels in show that the current wave of autocratization continues to deepen although substantial gains made during the third wave of democratization remain.

Figure 1. Liberal Democracy Index by country averages and population-weighted averages, 1972–2022.

Notes: The black lines represent global averages on the LDI with the grey area marking the confidence intervals. The left panel is based on conventional country averages. The right panel shows average levels of democracy weighted by population size.

also illustrates that the wave of autocratization spans all regions of the world, with the Asia-Pacific region affected the greatest in the population-weighted measure, not the least due to India’s steep decline on the LDI over the past ten years. The degree of liberal democracy enjoyed by the average citizen in that region is down to the 1978-level, even if a series of countries are much more democratic today than during the late 1970s (e.g. Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan). Levels of democracy continue to deteriorate in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia region, as well as in the Latin America and the Caribbean region and are now back to the levels last seen around 1990 in the population-weighted measures, although many countries are still better off today than 30 years ago – not the least in Eastern Europe.

Evenly divided between regimes but 72% of population in autocracies

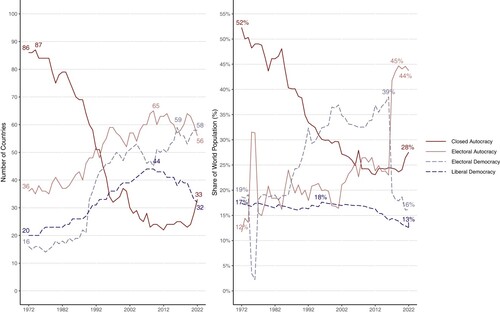

shows the continuing autocratization using the Regimes of the World (RoW) classification. RoW uses the same indicators that form the LDI to divide countries into four distinct regime types: closed autocracies, electoral autocracies, electoral democracies, and liberal democracies.Footnote8 The left panel depicts the number of countries, while the right panel presents the share of the world’s population by regime type, over the last five decades.

Figure 2. Regime types by number of countries and share of population, 1972–2022.

Notes: plots the number of countries (left panel) and the share of the world’s population (right panel) by regime type. Some uncertainty remains about regimes that exhibit similar degrees of authoritarian and democratic traits and thus are close to the threshold between democracy and autocracy. In 2022, uncertainty about countries scoring applied to 16 countries (notably, India is not among the 16 countries; it is unambiguously classified as an electoral autocracy since 2019). Thus, the number of autocracies in the world might range from 84 to 100 countries, with 89 being our best estimate based on the main RoW classification used for .

According to the RoW classification, the world is almost evenly divided between 90 democracies and 89 autocracies at the end of 2022. Yet, closed and electoral autocracies together contain almost 72% of the world’s population, or 5.7 billion people (including India’s 1.4 billion) – up from 46% only ten years ago.Footnote9

The number of liberal democracies declined from its peak of 44 in 2009 to 32 countries in 2022, with 13% of the world’s population. Although electoral democracies were on the rise during the last years and count the highest in absolute number with 58 countries in 2022, they are home to only 16% of the world’s population. Notably, the recent rise of electoral democracies is largely due to liberal democracies undergoing autocratization rather than electoral autocracies democratizing.

By contrast, the number of closed autocracies increased from 22 in 2012 to 33 countries in 2022 and accounts for almost 28% of the world’s population. Meanwhile, electoral autocracies remain the world’s most populous regime type, hosting 44% of the world’s population, or 3.5 billion people.

Large regional differences

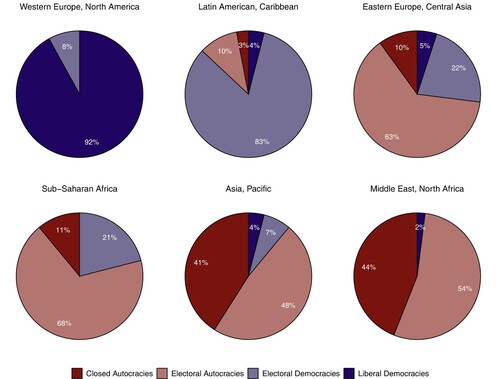

Democratic rights and freedoms are distributed unequally across citizens in the regions of the world, as depicted in . The most autocratic region is the Middle East and North Africa with 98% of the population residing in autocracies, and the remaining 2% living in Israel, which in early 2023 shows distinct signs of autocratization. Asia-Pacific, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Eastern Europe–Central Asia remain predominantly autocratic, with 89%, 79%, and 73% of these regions’ populations living in autocracies, respectively. In Latin America and the Caribbean there is a predominance of electoral democracy, hosting 83% of the region’s population. In Western Europe and North America, 92% of the population live in liberal democracies.

Drastic changes in the last decade

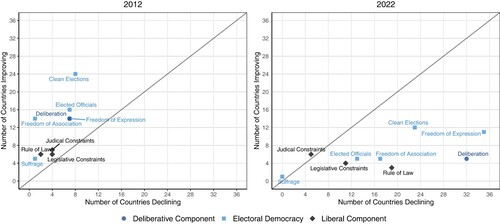

shows that most aspects of democracy have been negatively affected since 2012 compared to 2022. It displays the component-indices of the liberal, electoral, and deliberative democracy indices.Footnote10 The left panel demonstrates that more countries were improving, rather than declining, in every aspect of democracy in 2012. By 2022, there were more countries declining rather than improving in nearly all democratic aspects captured by the V-Dem liberal, electoral, and deliberative democracy indices (right panel).

Figure 4. Democratic aspects improving and declining, 2012 and 2022.

Notes: For indices measuring components of democracy, shows the number of countries improving and declining significantly (i.e. the confidence intervals do not overlap) and substantially (i.e. the difference is greater than 0.05). The left panel compares changes between 2012 and 2002, and the right panel compares changes between 2022 and 2012.

As shown in the right panel of , freedom of expression was the component of democracy in most decline, significantly worsening in 35 countries between 2012 and 2022, while improving in only 11. In comparison, the left panel shows that by 2012 there were only 7 countries in which this index had declined over the last ten years while in 14 it had improved. The deliberative component is the next worst affected, with substantial deteriorations in 32 countries in 2022, compared to 1 in 2012. The quality of elections and the rule of law also deteriorated in 23 and 19 countries, respectively, in contrast to 8 and 2 in 2012. For freedom of association, there were three times more countries declining (17) than advancing (5) by 2022.

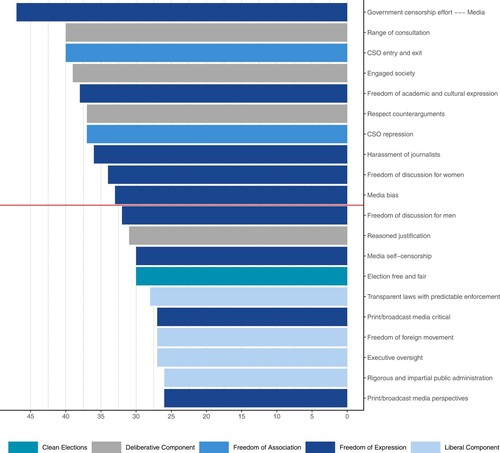

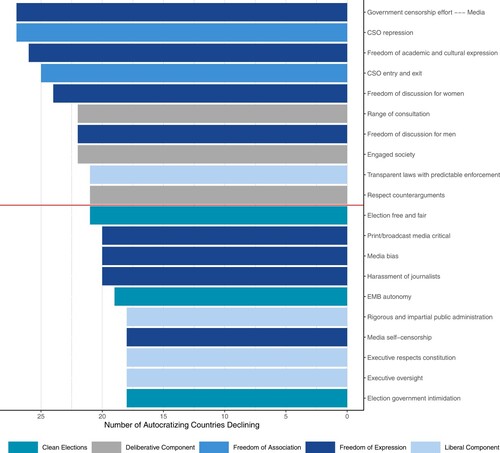

details which specific indicators of components declined in the largest number of countries between 2012 and 2022. Government censorship of the media got worse in 47 countries, harassment of journalists increased in 36 countries, and freedom of expression for women declined in 34 countries. Civil society was also under increasing pressure: the right to exist for civil society organizations (CSOs) declined in 40 countries, while repression of CSOs increased in 37 countries. More than 30 countries experienced substantial deterioration in the range of consultation by the government, the extent to which society is engaged in deliberation on policy, the level of respect for counterarguments, and the extent to which the government provides reasoned justification for their actions. Notably, there are many more countries that register declines on individual indicators than on the indices discussed above. This analysis thus hints at what aspects of democracy are often undermined first when countries start to autocratize.

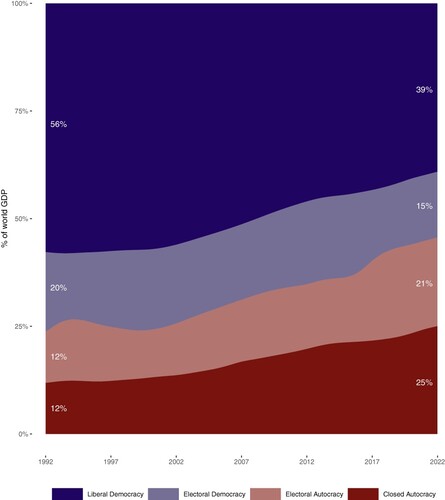

Autocracies account for a rising share of the world economy

shows that autocracies not only increased in numbers and in the share of the world’s population during the last decades but also became more powerful economically. By the end of the Cold War, democracies economically dominated the world, accounting for over 75% of global GDP/ppp.Footnote11 The Soviet Union – at the time the most economically powerful autocracy of the world – represented slightly above 10% of the world’s economy, while China accounted for about 4%. The remaining autocracies were barely visible statistically.

Figure 6. Share of world GDP (adjusted for purchasing power parity) by regime type, 1992–2022.

Notes: The data on GDP/ppp come from the World Economic Outlook (WEO) database (the International Monetary Fund).

By 2022, closed autocracies alone generated 25% of global GDP/ppp, while another 21% was attributable to electoral autocracies. Thus, autocracies combined account for 46% of world GDP/ppp, almost a doubling from 24% in 1992.

The change is driven by both economic and political transformations. Of course, it in part reflects China’s economic rise. Its share of world GDP/ppp increased from 4.4% in 1992 to 18.5% in 2022. Yet, some other autocracies were also growing fast due to demographic trends and their “catching up” in terms of economic productivity. Among closed autocracies, Vietnam almost quadrupled its share of world GDP/ppp over the last 30 years, while Qatar more than doubled its share of global GDP/ppp. In addition, electoral autocracies, including Angola, Egypt, Malaysia, Singapore, and Pakistan, also substantially increased their share of the global economy.

The continuing third wave of autocratization further accelerated this trend. India, which recently transitioned into an electoral autocracy, more than doubled its share of the global economy from 1992 and now accounts for 7.2% of global GDP/ppp. Türkiye (another country that turned from electoral democracy to electoral autocracy over the same period) increased its share from 1.3% in 1992 to 2.1% in 2022.

Democratizers and autocratizers

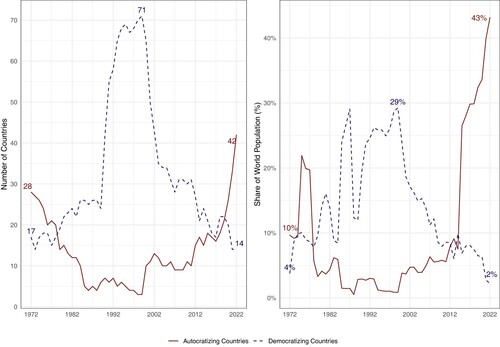

details patterns of democratization and autocratization over the last five decades. The left panel shows the number of countries in each category, while the right panel depicts their share of the world’s population. The number of democratizing countries declined from a peak of 71 with 29% of the world’s population in 1999 to 14 democratizing countries in 2022 – a low not seen since 1973. Notably, the 14 democratizing countries are small in population terms, with only 2% of the world’s population.

Figure 7. Autocratizing and democratizing countries, 1972–2022.

Notes: There is some uncertainty about the exact number of autocratizing and democratizing countries each year. In 2022, 8 countries were identified as borderline cases. The number of autocratizers could therefore range from 38 to 44, with 42 being our best estimate; and the number of democratizers could range from 14 to 16. See endnote 4 for details.

2022 registered a new record of 42 autocratizing countries, home to 43% of the world’s population. The upwards curve is indeed very steep over the last five years indicating an escalation of the autocratization wave.

It is notable that many of the world’s autocratizing countries are significant regional and global powers. Russia’s direct influence on the democratic aspirations in many of the former Soviet Republics, its invasion of Ukraine, and its weaponization of fossil fuel exports exemplify potential security implications resulting from autocratization. Brazil, India, Indonesia, Türkiye, and the United States of America are other populous, powerful, influential states among autocratizers over the past ten years.

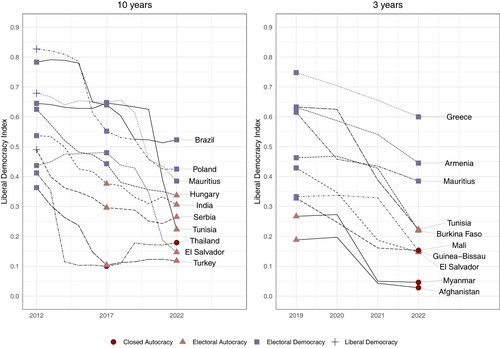

Major autocratizers

shows the top ten autocratizing countries over the last ten- and three-year periods, based on the magnitude of change.Footnote12 Democracy broke down in seven of the top ten autocratizing countries between 2012 and 2022 (left panel): El Salvador, Hungary, India, Serbia, Thailand, Tunisia, and Türkiye. Only three out of ten countries remained democracies in 2022: Brazil, Mauritius, and Poland. This indicates that almost 80% of democracies undergoing autocratization eventually lose their democratic status.Footnote13 Thus, the statistical probability that democracy will survive if a democratic country enters a period of autocratization, is very low.

Figure 8. Top 10 autocratizing countries (10 years vs. 3 years).

Notes: plots values of the LDI for the 10 countries with the greatest decreases in the last 10 years (left panel) and 3 years (right panel).

Notably, democracy also broke down in five out of ten countries in the shorter three-year perspective (right panel): Burkina Faso, El Salvador, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, and Tunisia.

Three countries – El Salvador, Mauritius, and Tunisia – appear as top autocratizers in both panels in . In Tunisia, the recent autocratization episode was substantial enough to be among the top ten even in the ten-year window. In El Salvador and Mauritius, the process of autocratization started some time ago but continued to a significant degree also in the last three years.

In seven out of ten countries in the ten-year perspective, the process of autocratization appears to have stalled or slowed down significantly. Two notable examples of this are Brazil and Poland, both of which halted the autocratization trend before democracy collapsed. The 2022 presidential election in Brazil led to the democratic removal of Jair Bolsonaro from office. In Poland, internal forces organized against autocratization, contemporaneous to the European Union pushing back on executive actions against the judiciary. Slowing down or stalling of autocratization is also noticeable in Hungary, India, Serbia, Thailand, and Türkiye, although the last three countries are at a very low level on the LDI and the extent to which further deterioration is possible was therefore limited.

Afghanistan, Armenia, Burkina Faso, Greece, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, and Myanmar are recent autocratizers and thus appear as top autocratizers only in the right panel of . In Armenia and Greece, the governments severely restrict press freedom and regularly prevent journalists from reporting on a number of issues. Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Myanmar suffered from serious human rights violations following the Taliban takeover and military coups.

It is notable that autocratization often goes beyond a deterioration of the quality of democracy in existing democracies, including Brazil, Greece, Poland, and the United States, and beyond a transition from electoral democracy to electoral autocracy in El Salvador, Hungary, and India. It also affects even already autocratic countries, such as Myanmar and Russia, which have become more repressively overt with a denial of even basic human rights.

Focusing on specific indicators of democracy that make up the indices above, we note further details about autocratization in . It shows that media censorship, repression of civil society, and academic freedom are the most frequent central focus of attacks by autocrats. These measures declined in over 25 autocratizing countries over the last decade. For example, government censorship of the media worsened significantly during this period in Afghanistan, El Salvador, Hong Kong, Mauritius, and Poland. Freedom of academic and cultural expression was severely weakened in Indonesia, Russia, and Uruguay, among many others. There were also significant deteriorations in the indicators for freedom of discussion for men and women, which declined in 22 and 24 countries, respectively. Two key indicators of deliberative democracy declined in 22 autocratizing countries. In Burundi, Myanmar, and Serbia, for instance, the range of actors invited to deliberate on policy changes declined significantly.

Figure 9. Top-20 declining indicators in autocratizing countries, 2012–2022.

Notes: plots the number of autocratizing countries declining significantly and substantially on the top 20 indicators. The red line marks the top 10 indicators. An indicator is declining substantially and significantly if its 2022 value is at least 0.5 points lower than its 2012 value on a scale ranging from 0 to 4 (for most variables) or 0 to 5 (for some variables), and the confidence intervals do not overlap.

Major democratizers

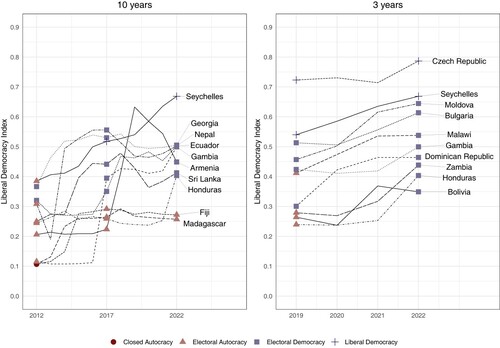

shows the top ten democratizing countries over the last ten- and three-year periods -countries that are defying the wave of autocratization. Eight out of the top ten democratizing countries in the last ten years (left panel) were autocracies in 2012. Only Georgia and Ecuador were democracies and have continued to improve further over the last ten years. By 2022 the situation is reversed: eight out of these ten are democracies. The Seychelles made a transition from electoral autocracy to liberal democracy and continues its upward trajectory. Armenia, The Gambia, Honduras, Nepal, and Sri Lanka progressed from the status of electoral autocracies to electoral democracies. Fiji and Madagascar improved substantially and significantly on the LDI but remain electoral autocracies.

Figure 10. Top 10 democratizing countries (10 years vs. 3 years).

Notes: plots values of the LDI for the 10 countries with the greatest increases in the last 10 years (left panel) and 3 years (right panel).

The right panel of focuses on the shorter three-year perspective. Notably, seven out of the top ten democratizers in the last three years are new: Bolivia, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, the Dominican Republic, Malawi, Moldova, and Zambia. Four out of the ten transitioned from electoral autocracy to electoral democracy in the last three years: Bolivia, Honduras, Malawi, and Zambia.

Nonetheless, most of the current democratizers are countries with small populations and limited global influence. This fact notwithstanding, there is some evidence that some European countries are now moving in a democratic direction: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, and Moldova are among the top ten democratizing countries in the last three years. Second, with transitions back to electoral democracy in two cases and one U-turn before democratic breakdown, Bolivia, Moldova, and Zambia joined an exclusive group of democracies showing defiance in the face of the global wave of autocratization. Below, we discuss eight cases of such democratic resurgence.

U-turns: at least eight democracies bouncing backFootnote14

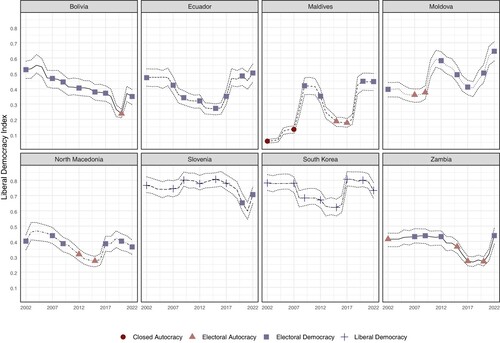

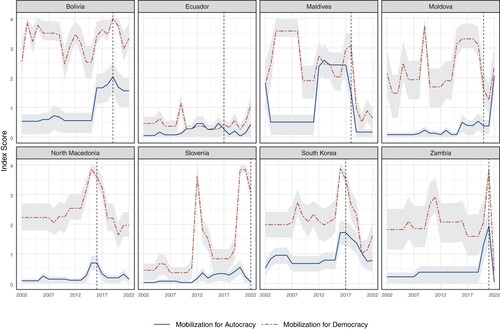

During the last decade, there were at least eight autocratizing countries that successfully halted autocratization and reversed the process: Bolivia, Ecuador, the Maldives, Moldova, North Macedonia, Slovenia, South Korea, and Zambia.Footnote15 These countries were democracies at some point in the last twenty years, registered a period of significant and substantial autocratization that was halted and was followed by a period of significant and substantial democratization at some point in the last ten years largely restoring the level of democracy, and they remain democracies as of 2022.Footnote16 renders the trajectories of the eight U-turn countries.

Figure 11. U-turns: Countries that halted autocratization and reverted to democracy, 2002–2022.

Notes: plots countries that were democracies at some point in the last 20 years, registered a period of significant and substantial autocratization that was halted and was followed by a period of significant and substantial democratization in the last 10 years largely restoring the level of democracy, and they remain democracies as of 2022.

These U-turn cases arguably have unique potential in suggesting how current autocratization processes can be reversed. Our analysis is not definitive but at a minimum is suggestive about which elements may help both to stop autocratization and reverse it. Though generalizability may be limited,Footnote17 we identify patterns across these eight most recent U-turns which point to new possible streams of research to systematically study democratic resurgence amid contemporary autocratization, its causes over time, and consequences for democratic resilience.

While all these countries lack “onset resilience”, Ecuador, Moldova, Slovenia, and South Korea show “breakdown resilience” (i.e. the ability to avert democratic breakdown once an autocratization episode has started).Footnote18 In the four remaining countries, democracy broke down before being re-instated. The cases reveal that there is a third type of resilience unanticipated by Boese et al., where autocratization leads to breakdown but pro-democratic elements still endeavour to successfully bring democracy back within a short time. Notably, in all the eight countries democratic procedures and institutions were undermined gradually, albeit at different paces and to varying degrees. Moreover, these eight countries are scattered over four world regions, have very different levels of socio-economic development, types of dominating religion, degrees of statehood, and differ substantially in their initial levels of democracy. These cases can potentially highlight broader lessons about how to halt and reverse autocratization.

In many of the U-turn countries, anti-pluralist leaders and parties drove autocratization.Footnote19 Until 2019, during the tenure of President Evo Morales, Bolivia was on a slow path of autocratization. In Ecuador, institutions were severely undermined under President Rafael Correa’s leadership (2007–2017) but the most recent 2021 presidential elections were largely seen as free and fair, enabling a peaceful transfer of power. The Maldives autocratized substantially under the rule of President Abdulla Yameen in power from 2013. Similarly, North Macedonia began to autocratize in 2007 under Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski. Starting in 2020, former Prime Minister Janez Janša in Slovenia seemed to mimic Hungary’s Viktor Orbán by undermining press freedoms.Footnote20 After its change of government, however, Slovenia regained democratic freedoms and became the first east European country to recognize same-sex marriage. Although South Korea remained a liberal democracy over the last 20 years, it went through an episode of autocratization between 2008 and 2016 that intensified under President Park Geun-hye’s tenure from 2013 to 2017. Zambia’s autocratization began with the electoral success of former President Edgar Lungu from the Patriotic Front (PF) in 2014. Only Moldova lacked a single autocratizing leader and deterioration was instead the product of widespread corruption and oligarchic control over politics.Footnote21 Zambia also exemplifies that in the breakdown cases, substantial improvements followed re-democratization such as the 2022 court ruling that the closure of the major Zambian newspaper The Post was illegal, signaling an improved media environment.Footnote22

Below we elaborate on five elements that seem critical in the eight U-turn cases: executive constraints, mass mobilization, alternation in power, unified opposition coalescing with civil society, and international democracy support and protection. We show that there are substantial commonalities, although alternation in power is the only element present in all cases. Moreover, we demonstrate that combinations of elements seem to have mattered in all countries, rather than a single development or event.

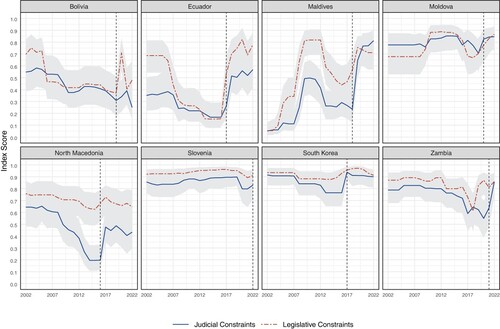

Executive constraints

Research suggests that executives’ power concentration – sometimes called “executive aggrandizement”Footnote23 or weakening of horizontal accountabilityFootnote24 – is one of the main threats to democracy.Footnote25 Elected officials weaken checks on executive power through a series of institutional changes that undermine the possibilities to constrain the executive. Halting or resisting autocratizers’ attempts to wield unconstrained power include independent controls by the judiciary and other independent institutions, and legislative oversight.

below highlights that aspiring autocrats were confronted with different levels of judicial and legislative constraints that may have ramifications on how successfully they could drive autocratization. We find that the strength of executive constraints seems to have been critical in enabling a turn-around in cases with high initial levels of democracy. In South Korea, for instance, public prosecutors were able to expose that President Park was engaged in corruption, ultimately leading to the legislature impeaching her, with the constitutional court subsequently upholding the conviction.Footnote26 In Slovenia, the opposition made active use of parliamentary statutes to hold the executive accountable and in 2020, members of parliament posed a total of 1,857 questions to the government and ministers, all of which had to be answered.Footnote27 Although several independent supervisory bodies such as the Court of Audit were under immense political pressure, the Janša government was ultimately not able to subsume it under political interests.Footnote28

Figure 12. Executive constraints in eight U-turn cases, 2002–2022.

Notes: The y-axis exhibits the scores of the indices for the judicial and legislative constraints. High scores indicate high levels of constraints on the executive. The vertical line shows the timing of a critical turnover of the head of government and/or the head of state.

Executive constraints also played a critical role in some countries with lower levels of democracy. In North Macedonia, the constitutional court in 2016 suspended elections that would have seen a full-blown victory for the government after the opposition announced a boycott.Footnote29 The re-scheduled elections resulted in the overthrow of Gruevski’s government and marked a turn-around. In Ecuador, the term limit that Correa abolished with the approval of the legislature and the Constitutional Court as part of his weakening of independent checks on the executive, ironically led to his downfall. Since it should have been phased out from 2021, Correa planned to transfer power to his ally and Vice-President Lenin Moreno for the 2017 Presidential elections. Yet, Moreno defected from the autocratizing path and reversed many of Correa’s decisions and policies, highlighting the importance of term limits and elite splits in ruling coalitions.Footnote30

A strong and independent judiciary can also be instrumental. In Moldova, the Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) controlled the presidency in 2021, while the legislature was still under oligarchic influence. After a failure to form a new government, the constitutional court ruled that snap elections should be held. Believing that this would lead to massive gains for PAS in the legislature, parliament attempted to block the elections by initiating a Covid-19 state of emergency and by replacing one of the judges of the constitutional court.Footnote31 Both actions were deemed unconstitutional and ultimately failed. With the court ruling and following the elections, Moldova continued its democratic progress.

Finally, in three countries executive constraints played a minor role perhaps since institutions and constraints had already been severely eroded in the process of autocratization.Footnote32 In the Maldives, President Yameen faced a political crisis when the supreme court in 2018 overruled terrorism convictions against members of parliament and previous President Mohammed Nasheen, and reinstated 12 members of the parliament that would enable parliament to impeach the president. In response, Yameen called for a state of emergency, sent troops to parliament, and arrested two justices of the supreme court.Footnote33 The president was ousted in the presidential election later the same year and opposition leader Ibrahim Soli won. In Bolivia, the electoral management body was unwilling or unable to thoroughly investigate allegations of electoral fraud. Instead, Bolivia’s return to democracy was marked by mass mobilization, splits within the ruling elite, and Morales’ loss of the army’s support. Zambia’s return to democracy was rooted in a robust and dense network of civil society actors organizing mobilization for democracy and actively resisting Lungu’s attempts for constitutional amendments. This resulted in electoral victory of the opposition leader from the United Party for National Development (UPND), Hakainde Hichilema, in 2021.Footnote34

Mass mobilization

Mobilization is another element seen in many of the U-turn countries, often discussed in the literature on democratic resilience.Footnote35 On the one hand, mobilization for democracy is typically important for democratization.Footnote36 Political pressure from below may create an opportunity for the democratic opposition to win elections,Footnote37 and to prevent the ruling party from implementing further autocratic reforms.Footnote38 Thus, we may expect that mass mobilization can play a critical role in halting and reverting autocratization. On the other hand, authoritarian-leaning governments also mobilize support to shield themselvesFootnote39 and to demonstrate their popularity and legitimacy.Footnote40

displays the patterns of mobilization for democracy and for autocracy in the U-turn cases. Mobilization for democracy tends to be especially high in proximity to critical turnovers of the heads of government and/or heads of state. In most of the cases, mass mobilization was triggered by a critical event, such as corruption scandals in Moldova and South Korea, or anti-democratic reforms or attempts at them, for example in the Maldives and North Macedonia. This aligns with previous research: once rulers initiate policy initiatives and reforms that undermine democracy, opposition groups mobilize to defend democratic norms.Footnote41 In Slovenia, for instance, massive anti-government protests occurred in 2021 following civil society’s mobilization to oppose Janza’s autocratizing reforms.Footnote42 In the Maldives, opposition groups protested intensively in 2018 against President Yameen.Footnote43 In North Macedonia, autocratization initiated by Prime Minister Gruevski prompted the opposition to coordinate massive protests a year prior to the 2016 elections.Footnote44 These examples suggest that civil society played an influential role in reversing autocratization.

Figure 13. Mobilizations for democracy and autocracy in U-turn cases, 2002–2022.

Notes: The y-axis exhibits the scores of the mobilization indicators. High scores indicate high levels of mobilization. The vertical line shows the timing of a critical turnover of the head of government and/or the head of state.

Some of the cases exhibit the importance of long-term mobilization against an autocratizing government. In Bolivia, for example, the opposition movement and popular mobilization against Morales grew over time. After Bolivia’s constitutional court annulled the results of a referendum, in which 51 percent of Bolivians had rejected a constitutional draft that would have allowed Morales to seek another term, nationwide protests erupted. Protesters in the streets, united under the slogans of “February 21” and “No means no”, questioned the legitimacy of the court by casting null votes in 2017 judicial elections. These movements served as platforms for the 2019 electoral protests, putting immense pressure on Morales to resign.Footnote45 Such sustainable resistance may also be a key for democratic resurgence.

In addition to strong mobilization for democracy, most of the cases discussed here show relatively low levels of mobilization for autocracy throughout the autocratization episodes (). The absence of strong mobilization for autocracy should make it easier for a democratic opposition to oust a regime and may be an important factor facilitating democratic resurgence. In Bolivia, the Maldives, North Macedonia, South Korea, and Zambia, levels of mobilization for autocracy increased significantly at some point but remained below the levels of mobilization for democracy most of the time.

Mobilization for autocracy can nonetheless be a significant feature of autocratization episodes.Footnote46 In the eight cases analysed here, mobilization typically increases towards the end of autocratizing leaders’ tenure. Some rally their supporters more intensively to exhibit legitimacy, including in Bolivia, the Maldives, South Korea, and Zambia. In South Korea, many of President Park’s supporters took part in anti-impeachment rallies in response to protests directed at the president in 2016.Footnote47 In Bolivia, Morales’s supporters counter-reacted mass mobilization after the 2019 presidential election, leading to street clashes between pro- and anti-government protesters.Footnote48 Mobilization for autocracy raises questions about the long-term democratic stability in these countries.

Government turnover, democratic opposition, and international support for democracy

While executive constraints and mass mobilization are common elements in most or all of our U-turn cases, our analysis also points to additional elements. Aspects that seem to have influenced the reversal in several of the cases include: removal of autocratizing leaders, successful opposition unity and effective strategies, and international democracy support and protection.

Removing autocratizing leaders and parties from power is a critical aspect of reversing autocratization. Elections are a natural tool for replacing incumbents but one that may not always be possible once autocratization has taken hold. Elections seem to have played an important role in at least five of the eight cases: the Maldives, Moldova, North Macedonia, Slovenia, and Zambia. Elections led to a majority for pro-democratic parties, removing autocratizing incumbents, crucial for initiating or continuing renewed democratization. Notably, elections not only played this role in countries that were still democratic – Moldova and Slovenia – but in three countries where democracy had already broken down. The removals of President Yameen in the Maldives, Prime Minister Gruevski in North Macedonia, and President Lungu in Zambia happened through elections in an autocratic context favouring the incumbents. In line with some of the earlier literature, this points to the importance of elections in the democratization of autocracies.Footnote49

In three additional cases, U-turns were facilitated by other critical events filling as similar function. In South Korea, Park was ousted by impeachment. In Ecuador, Correa was replaced by his vice-president Moreno due to term-limits, with Moreno subsequently abandoning Correa’s autocratizing project. In Bolivia, Morales resigned as the outcome of multiple pressures toward his unpopular rule. Thus, while elections may serve as important focal points around which opposition may unite to oust autocratizing leaders, these cases demonstrate that this is not the only viable path to remove autocratizing incumbents. The seemingly critical role of removing anti-pluralist leaders to stop and turn autocratization around, corroborate recent findings showing the central role of anti-pluralist leaders in contemporary autocratization processes.Footnote50

A unified opposition coalescing with civil society pursuing peaceful, legal strategies also seems to have been important in seven of the U-turn cases. For example, in Zambia, civil society groups, including the Zambian Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Council of Churches of Zambia, advanced peaceful mass mobilization for democracy which resulted in opposition leader Hakainde Hichilema’s electoral victory in 2021.Footnote51 In Moldova, an embezzlement scandal exposed the extensive political corruption in 2014, which led to widespread protests during 2015–2016.Footnote52 Opposition parties, including the PAS, grew by capturing popular discontent during this protest.Footnote53 Similarly in Slovenia, civil society and non-governmental organizations joined forces in the fight against Janza’s rule. Galvanizing growing public discontent, mobilization for democracy helped Robert Golob come to power in 2022.Footnote54

Not unexpectedly, there is an overlap between countries where a unified opposition coalesced with civil society and instances where incumbents were replaced through elections. Yet, also in South Korea broad segments of a largely unified opposition and civil society coalesced and mounted pressure for impeachment, demonstrating the wider potential of coalition-building in ousting autocratizers. Thus, in seven of the eight cases, coalescing different pro-democratic actors and creating a joint resistance to autocratization seem to have been important elements for halting and reversing autocratization. This conclusion also aligns with previous findings.Footnote55

The strategies adopted by opposition actors also seem important. The cases of Bolivia and Ecuador show that peaceful protests and challenging the incumbent government through parliamentary and legal means, can keep the door open for government turnover and democratic resurgence. This finding echoes those in recent research pointing towards the dangers of irregular attempts to remove incumbents from office.Footnote56 Unlawful actions may backfire and rather embolden leaders with autocratic tendencies to clamp down harder on opposition and civil society. Türkiye and Venezuela are illustrations of this.Footnote57

Finally, international democracy support and protection can contribute to halting and reversing autocratization, a factor also suggested elsewhere.Footnote58 In at least five of our featured cases, it seems that international democracy promotion efforts were important: Bolivia, Ecuador, North Macedonia, Slovenia, and Zambia. In Ecuador, for example, some media corporations and civil society organizations appealed against domestic legal decisions to international institutions, including the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The European Union put pressure on autocratizers in Slovenia, while facilitating negotiations between polarized political parties in North Macedonia. These examples possibly point to good news for the international support and protection community, and to a need to study this aspect of the processes in more depth.

Summary of the findings from the eight U-turn cases and looking forward

summarizes the analysis of the five elements that seem to be important in halting and reversing autocratization in the eight U-turn cases. While alternation of power cuts across all cases, perhaps the most important conclusion is that no single factor alone was decisive, with several working in tandem. Similar to Lührmann and Laebens, we find that different combinations were important in different settings.Footnote59 In South Korea, for instance, the legislature and judiciary responded only when popular pressure was too great to ignore. In North Macedonia, international efforts to organize negotiations enabled elections that were ultimately responsible for the ousting of Gruevski. In the Maldives, Slovenia, and Zambia, widespread mobilization for democracy ahead of elections ensured a substantial opposition turnout and support, tipping the electoral scales in favour of the democratic opposition. These are but a few examples of how combinations of elements contributed to removing autocratizers from power and putting countries back on a democratic path.

Table 1. Five important elements across the U-turn cases.

The analysis here of eight U-turns should be informative of how contemporary autocratization can be halted and reversed, but causal impact of the factors need to be corroborated in further research. The descriptive analysis can be read as providing insights on potential causal factors that can guide future scholarship on understanding both U-turns and why autocratization in other cases resulted in entrenched autocratic rule. Our first attempt at understanding how these countries managed to reverse autocratization can serve as a useful starting point for assessing determinants of continued autocratization and reversals.

Finally, can we be optimistic that countries experiencing U-turns will not revert to autocratization? We do not know. One observation may shed some light on the question: demobilization seems central. While most of the eight cases register a sharp decline in mobilization after the restoration of democracy, mobilization against the democratic government in Moldova has intensified since 2022.Footnote60 Violent protests also erupted in Bolivia when an anti-Morales opposition leader, Luis Fernando Camacho, was arrested in 2022.Footnote61 Democratic long-term stability may face significant challenges in these two cases.Footnote62 Thus, reducing mobilization for autocracy may be one key ingredient for further democratic stability of the country reversing autocratization, something that other studies have also pointed to.Footnote63

Conclusion

This article documents a deepening of the third wave of autocratization. The global average of the LDI is back to 1986-levels by population weighted-averages, and to 1997-levels by country-averages. A record of 42 countries are autocratizing, hosting 43% of the world’s population. Autocracies are home to almost 72% of the world’s population and generate 46% of global GDP/ppp.

Yet, we also report on eight cases of defiance in the face of the global wave of autocratization. A novel analysis of these eight U-turns demonstrates that executive constraints, mass mobilization, alternation in power, a unified opposition coalescing with civil society, and international democracy support and protection seem to have played an important role in the reversals. Extending existing literature, our analysis illustrates conditions under which contemporary autocratization can be stopped and reversed. These findings may serve as a useful starting point for causal analyses of stopping and reversing contemporary autocratization as well as failures to do so.

We should not generalize from the study of a few cases selected on the dependent variable without counterfactuals. We thus encourage scholars to analyse these cases and their counterfactuals more thoroughly, including the ways U-turns differ from cases where autocratization was successful. That would improve our understanding of both autocratization and its reversal. Yet, given that the five elements seem to have been important across many of the eight U-turn cases that otherwise differ substantially and are disbursed across world regions, the elements pointed to in our analysis at a minimum have the potential to travel across contexts.

In terms of the state of the world in 2022, the autocratizing trend far outweighs that of the U-turns. We do not find evidence suggesting that the wave of autocratization is slowing down, or that the influence of autocratic countries is declining – quite the opposite. However, the U-turn cases demonstrate defiance in the face of the predominant autocratization trend that we have seen little of before.

Acknowledgements

We thank Evie Papada, Lisa Gastaldi, Tamara Köhler, and Natalia Natsika for their contributions to the Democracy Report 2023.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Felix Wiebrecht

Felix Wiebrecht is a postdoctoral research fellow at the V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg. His research focuses on authoritarian politics and institutions as well as democratization and autocratization processes.

Yuko Sato

Yuko Sato is a postdoctoral research fellow at the V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg. Her research focuses on popular protests, voting behavior, democratization, and autocratization, with a regional focus on Latin America. Her previous research appeared in Electoral Studies, Policy Studies Journal, and Democratization.

Marina Nord

Marina Nord is a postdoctoral research fellow at the V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg. Her research focuses on the interaction of political and economic systems around the world, with a focus on economic sources of regime (in)stability.

Martin Lundstedt

Martin Lundstedt is an assistant researcher at the V-Dem Institute, Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg.

Fabio Angiolillo

Fabio Angiolillo is a postdoctoral research fellow at the V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg. His research focuses on comparative politics, political institutions, authoritarian regimes, and political behavior.

Staffan I. Lindberg

Staffan I. Lindberg is Professor of Political Science and Director of the university-wide research infrastructure at the V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg, founding Principal Investigator of Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem), founding Director of the national research infrastructure DEMSCORE, Wallenberg Academy Fellow, author/editor of several books, and 60+ articles on democracy, elections, democratization, autocratization, accountability, clientelism, sequence analysis methods, women's representation, and voting behavior in journals such as APSR, AJPS, Political Analysis, Democratization, World Development, World Politics, etc.

Notes

1 Coppedge et al., V-Dem Country-Year Dataset v13.

2 Lührmann and Lindberg, “The Third Wave of Autocratization.”

3 We focus mostly on changes in V-Dem’s Liberal Democracy Index (LDI) in this article. It captures both electoral and liberal aspects of democracy and goes from the lowest (0) to the highest (1) levels of democracy. The electoral component is measured by the Electoral Democracy Index (EDI) that captures the extent to which all elements of Robert Dahl’s famous articulation of “polyarchy” are present, including the quality of elections, universal suffrage, freedoms of expression and association, and an independent media capable of presenting alternative views. The Liberal Component Index (LCI) captures the liberal aspects including checks and balances on the executive, respect for civil liberties and individual rights, the rule of law, and the independence of the legislature and the judiciary. Dahl, Polyarchy.

4 The exact calculation of these numbers is associated with some amount of uncertainty that is inherent in the data. For each variable in the V-Dem dataset, estimates and confidence intervals are calculated from 900 random draws from the full posterior distribution. Recalculations done in the process of data curation each time involve a new set of 900 random draws that affect both point estimates and confidence intervals up to, typically, their third decimal. Borderline cases, which are very close to thresholds for whether confidence intervals are overlapping or not, can be affected by randomness in draws. There are eight borderline cases this year where differences in random draws between the first rendition of the v13 dataset (which we used for the Democracy Report 2023) and the final version (posted on the V-Dem website) could have led to changes: Chile, Ghana, Mozambique, the United States, Mexico, Portugal, Kosovo, and Kenya. For consistency reasons, we continue using the first rendition of the v13 dataset in this article and thus keep the classification used in the Democracy Report 2023. Chile, Ghana, Mozambique, and the United States are thus classified in this article as autocratizers while Mexico and Portugal are not; Kenya and Kosovo could have been classified as democratizers but are not. We nevertheless stress that a degree of caution is advisable when interpreting classification of the borderline cases.

5 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail;” Gamboa, Resisting backsliding; Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?”; Tomini, Gibril, and Bochev, “Standing up Against Autocratization.”

6 Lührmann et al., “Regimes of the World (RoW).”

7 Huntington, The Third Wave.

8 Lührmann et al., “Regimes of the World (RoW).”

9 Percentages are rounded throughout the article. The 72% mentioned here builds aggregating rounded figures for closed and electoral autocracies on . Population data come from the World Bank included in v.13 of the V-Dem dataset.

10 On the LDI and the Electoral Democracy Index (EDI), see endnote 3. The Deliberative Component Index (DCI) captures to what extent the deliberative principle of democracy is achieved. It assesses the deliberative process by which decisions are made in a polity.

11 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is estimated in local currency unites. GDP adjusted for purchasing power parity (ppp) is GDP converted to international dollars using purchasing power parity of different currencies.

12 There is a slight change in this figure from the version published in the Democracy Report 2023: A difference between the first rendition of the v13 dataset used for the analysis here and the final version led to the inclusion of Guinea-Bissau in the graph above and the exclusion of Guatemala. See footnote 4 for the explanation.

13 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail.”

14 In this section, we elaborate on the analysis in V-Dem’s Democracy Report 2023 and connect it with broader academic literature and debates.

15 In the final stages of preparing this article, we found three more potential cases of U-turns over the last 10 years that could have been included in the analysis: Lesotho, Nepal, and Romania. Future studies should consider including them in the analysis.

16 We define that the difference is statistically significant if confidence intervals do not overlap and substantial if the difference is greater than 0.05.

17 Geddes, “How the Cases You Choose Affect the Answers You Get.”

18 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail.”

19 Medzihorsky and Lindberg,”Walking the Talk.”

23 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding”; Lührmann and Lindberg, “The Third Wave of Autocratization.”

24 O'Donnell, “Horizontal Accountability in New Democracies.”

25 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail”; Tomini, Gibril, and Bochev, “Standing up Against Autocratization”; Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?”

26 Shin and Moon, “South Korea after Impeachment.”

28 Ibid.

29 Tomini, Gibril, and Bochev, “Standing up Against Autocratization.”

30 Meng, “Constraining dictatorship”; Rio, “Strategic Uncertainty.”

32 Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?”; Tomini, Gibril, and Bochev, “Standing up Against Autocratization.”

35 Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?”

36 E.g. Teorell, Determinants of Democratization; Brancati, Democracy Protests.

37 Sato and Wahman, “Elite Coordination and Popular Protest.”

38 Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?”

39 Pérez-Liñán, “A Two-Level Theory of Presidential Instability.”

40 Hellmeier and Weidmann, “Pulling the Strings?”

41 Sato and Arce, “Resistance to Populism.”

42 https://balkaninsight.com/2021/04/27/slovenian-protesters-rally-against-degradation-of-democracy/.

45 Guachalla, et al., “Latin America Erupts.”

46 Ekiert et al., “Ruling by Other Means”; Hellmeier and Weidmann, “Pulling the Strings?”

47 Chang and Park, “A Heterogeneous Rally Effect for a Corrupt President.”

48 Lehoucq, “Bolivia’s Citizen Revolt.”

49 E.g. Lindberg, Democracy and Elections in Africa; Edgell et al., “When and Where Do Elections Matter?”; Donno, “Elections and Democratization in Authoritarian Regimes.”

50 E.g. Medzihorsky and Lindberg, “Walking the Talk”; Haggard, S., and Kaufman, Backsliding.

51 Resnick, “How Zambia’s Opposition Won.”

52 https://freedomhouse.org/country/moldova/nations-transit/2016; https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/30/world/europe/moldova-parliament-dismisses-government-amid-bank-scandal.html.

55 Sato and Wahman, “Elite Coordination and Popular Protest;” Tomini, Gibril, and Bochev, “Standing up Against Autocratization.”

56 Cleary and Öztürk, “When Does Backsliding Lead to Breakdown?”; Gamboa, Resisting backsliding.

57 Ibid.

58 Leininger, “International Democracy Promotion in Times of Autocratization.”

59 Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?”

62 There is also a growing concern about mobilization supporting the previous autocratizing regime in South Korea. Yang, “Defending ‘Liberal Democracy’?” Yet, our data indicates that the intensity of mobilization for autocracy did not rise substantially since the democratic comeback.

63 E.g., Hellmeier and Bernhard, “Regime Transformation from Below.”

Bibliography

- Bermeo, N. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27, no. 1 (2016): 5–19.

- Boese, V. A., A. Edgell, S. Hellmeier, S. F. Maerz, and S. I. Lindberg. “How Democracies Prevail: Democratic Resilience as a Two-Stage Process.” Democratization 28, no. 5 (2021): 885–907.

- Boese, V. A., M. Lundstedt, K. Morrison, Y. Sato, and S. I. Lindberg. “State of the World 2021: Autocratization Changing Its Nature?” Democratization 29, no. 6 (2022): 983–1013.

- Brancati, D. Democracy Protests: Origins, Features and Significance. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Chang, K., and J. Park. “A Heterogeneous Rally Effect for a Corrupt President: Partisanship, Regional Sentiment, and Anxiety Against a Corruption Scandal.” Democratization 27, no. 8 (2020): 1354–1375.

- Cleary, M. R., and A. Öztürk. “When Does Backsliding Lead to Breakdown? Uncertainty and Opposition Strategies in Democracies at Risk.” Perspectives on Politics 20, no. 1 (2022): 205–221.

- Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, C. H. Knutsen, S. I. Lindberg, J. Teorell, D. Altman, M. Bernhard, et al. V-Dem Country-Year Dataset v13 (2023).

- Dahl, R. A. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971.

- Donno, D. “Elections and Democratization in Authoritarian Regimes.” American Journal of Political Science 57, no. 3 (2013): 703–716.

- Edgell, A. B., V. Mechkova, D. Altman, M. Bernhard, and S. I. Lindberg. “When and Where Do Elections Matter? A Global Test of the Democratization by Elections Hypothesis, 1900–2010.” Democratization 25, no. 3 (2018): 422–444.

- Ekiert, G., E. J. Perry, and X. Yan, eds. Ruling by Other Means: State-Mobilized Movements, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Gamboa, L. Resisting Backsliding: Opposition Strategies Against the Erosion of Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Geddes, B. “How the Cases You Choose Affect the Answers You Get: Selection Bias in Comparative Politics.” Political Analysis 2 (1990): 131–150.

- Guachalla, V. X. V., C. Hummel, S. Handlin, and A. E. Smith. “Latin America Erupts: When Does Competitive Authoritarianism Take Root?” Journal of Democracy 32, no. 3 (2021): 63–77.

- Haggard, S., and R. Kaufman. Backsliding: Democratic Regress in the Contemporary World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Hellmeier, S., and M. Bernhard. “Regime Transformation from Below: Mobilization for Democracy and Autocracy from 1900 to 2021.” Comparative Political Studies, no. 0(0) (2023): 1–33. doi:10.1177/00104140231152793

- Hellmeier, S., N. B, and N. B. Weidmann. “Pulling the Strings? The Strategic Use of Pro-Government Mobilization in Authoritarian Regimes.” Comparative Political Studies 53, no. 1 (2020): 71–108.

- Huntington, S. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.

- Laebens, M. G., and A. Lührmann. “What Halts Democratic Erosion? The Changing Role of Accountability.” Democratization 28, no. 5 (2021): 908–928.

- Lehoucq, F. “Bolivia’s Citizen Revolt.” Journal of Democracy 31, no. 3 (2020): 130–144.

- Leininger, J. “International Democracy Promotion in Times of Autocratization.” From Supporting to Protecting Democracy (No. 21/2022). IDOS Discussion Paper (2022).

- Lindberg, S. I. Democracy and Elections in Africa. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Lührmann, A., and S. I. Lindberg. “A Third Wave of Autocratization is Here: What is New about It?” Democratization 26, no. 7 (2019): 1095–1113.

- Lührmann, A., M. Tannenberg, and S. I. Lindberg. “Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes.” Politics and Governance 6, no. 1 (2018): 60–77.

- Medzihorsky, J., and S. I. Lindberg. “Walking the Talk: How to Identify Anti-Pluralist Parties.” Party Politics (Forthcoming).

- Meng, A. Constraining Dictatorship: From Personalized Rule to Institutionalized Regimes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- O'Donnell, G. A. “Horizontal Accountability in New Democracies.” Journal of Democracy 9, no. 3 (1998): 112–126.

- Papada, E., D. Altman, F. Angiolillo, L. Gastaldi, T. Köhler, M. Lundstedt, N. Natsika, M. Nord, Y. Sato, F. Wiebrecht, and S. I. Lindberg. Defiance in the Face of Autocratization. Democracy Report 2023. Gothenburg, University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem Institute), 2023.

- Pérez-Liñán, A. “A Two-Level Theory of Presidential Instability.” Latin American Politics and Society 56, no. 1 (2014): 34–54.

- Resnick, D. “How Zambia’s Opposition Won.” Journal of Democracy 33, no. 1 (2022): 70–84.

- Río, A. D. “Strategic Uncertainty and Elite Defections in Electoral Autocracies: A Cross-National Analysis.” Comparative Political Studies 55, no. 13 (2022): 2250–2282.

- Sato, Y., and M. Arce. “Resistance to Populism.” Democratization 29, no. 6 (2022): 1137–1156.

- Sato, Y., and M. Wahman. “Elite Coordination and Popular Protest: The Joint Effect on Democratic Change.” Democratization 26, no. 8 (2019): 1419–1438.

- Shin, G.-W., and R. Moon. “South Korea after Impeachment.” Journal of Democracy 28, no. 4 (2017): 117–131.

- Teorell, J. Determinants of Democratization: Explaining Regime Change in the World, 1972–2006. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Tomini, L., S. Gibril, and V. Bochev. “Standing up Against Autocratization Across Political Regimes: A Comparative Analysis of Resistance Actors and Strategies.” Democratization 30, no. 1 (2023): 119–138.

- Yang, M. “Defending ‘Liberal Democracy’? Why Older South Koreans Took to the Streets against the 2016–2017 Candlelight Protests.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 25, no. 3 (2020): 365–382.