?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In contexts of democratic backsliding, citizens represent the last bulwark against the systematic dismantling of checks and balances by overbearing executives. And yet, they repeatedly fail to punish authoritarian-leaning leaders at the ballot box, allowing them to consolidate their grip on power. Why is that so? We leverage a conjoint survey experiment in Hungary to probe competing mechanisms of citizen tolerance towards democratic violations in a context of severe backsliding. Our main contribution consists of demonstrating empirically the presence of a composite effect, whereby authoritarian-leaning elites succeed in offering targeted compensations to different groups, ultimately building a mosaic of support among voters to secure enduring electoral backing. We pinpoint trade-offs notably related to cultural conservatism and economic benefits among different subgroups of the population. At the same time, our empirical findings indicate surprisingly high levels of condemnation of undemocratic positions by Hungarian respondents. We discuss how this unexpected pattern points to the limitations of conjoint designs as well as the overlooked supply side of democratic backsliding. Our study feeds into broader debates about the unfolding and entrenchment of democratic backsliding and how we study these processes.

Introduction

Democratic backsliding is among the gravest challenges facing contemporary democracies. From the United States to several countries in Central-Eastern Europe, the gradual erosion of democratic quality via the systematic dismantling of institutional checks and balances increasingly touches democracies previously hailed as consolidated.Footnote1 A particular puzzle in such contexts is why citizens, despite high levels of general support for democracy, lend electoral support to authoritarian-leaning leadersFootnote2, in other words: what drives citizens to tolerate political leaders who engage in democratic violations?

Three plausible explanations have been advanced to explain this puzzleFootnote3: citizens may overlook democratic backsliding because they a) fail to recognize democratic violations undertaken by a leader; b) prioritize alternative benefits promised by a leader over respect for democratic procedures; or c) hold competing conceptions of democracy that lead to divergent assessments of the democratic nature of a given leader’s actions. Studies to date typically zoom into a single explanation for voters’ behaviour in backsliding contexts, alternatively pinpointing partisan polarizationFootnote4, economic trade-offsFootnote5 or divergent democratic attitudesFootnote6 leading the electorate to overlook violations of democratic principles.

Rather than seeking to demonstrate a single overarching reason why voters tolerate democratic backsliding, this study theorizes and empirically probes the argument that support groups of authoritarian-leaning leaders are diverse and that different citizen groups tolerate democratic violations for different reasons. In doing so, we build on the insight that electoral coalitions always consist of a heterogeneous group of voters. Cas MuddeFootnote7 has qualified the assumption of a homogeneous electorate as one of the fundamental problems of empirical research on radical right support: the “stereotypical voter” of a populist radical right party in fact constitutes a minority of its electorate. Other studies similarly highlight the heterogeneity of electorates of specific politicians and populist right parties.Footnote8 Extending these findings to the context of democratic backsliding, we assume that voters will be attracted to different aspects of a leader’s programme and engage in distinct trade-offs between leaders’ undemocratic positions and other aspects of their profile. Ultimately, these distinct logics amount to a “mosaic” pattern of authoritarian support that enables an authoritarian-leaning leader to remain in power.

Our empirical analysis focuses on the case of Hungary as one of the most severe instances of contemporary democratic backsliding. Since his arrival in power in 2010, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has gradually expanded his powers by deliberately weakening a range of traditional democratic safeguards.Footnote9 Orbán’s remarkable ability to secure ongoing electoral support despite gradually chipping away at democratic achievements occurs against the backdrop of his earlier success in converting his Fidesz party from a smallish, liberal youth movement into a dominant centre-right party that unites a large section of the electorate behind itself.Footnote10 Enyedi has described the party’s transformation during the 1990s and 2000s as a conscious process of building a sustainable coalition by uniting agrarian, religious and national-conservative interests, eventually integrating separate segments of society to constitute a “mosaic cleavage party”Footnote11 that serves several core groups. By studying citizens’ responses to democratic backsliding in this specific context, we probe both how different constituencies respond to democratic violations and how the deepening of democratic erosion affects citizens’ ability to act as bulwarks against the dismantling of democratic safeguards.

We investigate these questions in a pre-registered, well-powered conjoint experiment that asks respondents to choose between two alternative leadership profiles containing information on competing leaders’ democratic views alongside other attributes. The experimental set-up deliberately excludes partisanship to focus instead on a range of economic, cultural, and attitudinal trade-offs that we assess at the aggregate level as well as for distinct subgroups. Our findings indicate on average a surprisingly high and consistent condemnation of democratic violations across all voter groups. Leaders expressing problematic positions regarding either judicial independence or their general conception of democracy are punished by all voter groups, with our democratic attributes showing the greatest effect size. Still, we find some variation with regards to subgroups: the rejection of non-democratic candidates is stronger among highly educated respondents and those of higher economic status. In turn, respondents with lower economic status are more open to buy-outs in the form of direct payments granted in a context of economic recovery, while religious respondents tend to value a leader’s cultural conservatism particularly highly. We thus find some evidence for our assumption of mosaic support, but also note a discrepancy between our experimental findings and the empirical reality of continued electoral support for Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party.

By examining the determinants of citizen tolerance for authoritarian-leaning leaders in a context of advanced democratic backsliding, our study makes two important contributions to our understanding of citizens’ responses to such processes. For one, we confirm that certain groups’ resolve to punish democratic violations by leaders is weakened by economic or cultural aspects, indicating an openness to trade-offs to which authoritarian-leaning leaders can actively pander. At the same time, we show that the defence of democracy remains a strong priority for the bulk of citizens in a previously reasonably consolidated democratic system. The fact that voters are unable to translate such democratic attitudes into electoral outcomes shifts attention to the supply side, where electoral manipulation and a lack of open advocacy for democratic violations by political leaders may explain the gap between our experimental results and electoral outcomes in Hungary. This interpretation has important implications both for future research seeking to explain the persistence and entrenchment of democratic backsliding and for practical approaches developed to resist the erosion of democracy.

The following section presents the theoretical rationale of our study, provides some contextual background on the Hungarian case, and introduces the hypotheses. We then outline our research design, explaining the experimental set-up and our analytical approach in line with our pre-analysis plan. The next section presents our empirical findings for the aggregate sample as well as distinct subgroups. In the following, we discuss the identified discrepancy between strong condemnation of democratic violations in the experimental setting and enduring electoral support for Orbán and Fidesz. The conclusion articulates the broader implications of our findings and spells out some promising research avenues to further explore the supply side of democratic backsliding.

Explaining citizen tolerance for democratic backsliding

Why citizens tolerate democratic violations and choose to re-elect leaders engaged in the dismantling of democratic safeguards represents a core puzzle in the literature on democratic backsliding.Footnote12 The case of Hungary is particularly intriguing in this regard: initially hailed as a frontrunner of post-Communist democratization, the country has experienced severe degradation of democratic standards under the Fidesz government and party leader Viktor Orbán since his return to power in 2010.Footnote13 According to both V-Dem and Freedom House, Hungary passed the threshold towards an electoral autocracy in 2019Footnote14, effectively transforming a fragile democracy into an outright undemocratic regime after a tortuous and ultimately unsuccessful process towards democratic consolidation.Footnote15

Orbán’s current period of rule is not his first stint in government. Between 1998 and 2002, Fidesz, as senior coalition partner, oversaw a significant strengthening of the Prime Minister’s powersFootnote16 that laid the groundwork for the subsequent process of executive expansion. His eventual return to power in 2010 was facilitated by a particularly fateful constellation of anti-incumbent voting following the loss of credibility of the ruling Socialist Party and the increasingly visible fallout of the global economic crisis for Hungary.Footnote17 Four years on, Fidesz succeeded in producing a “perfect storm”Footnote18 by securing a supermajority which, combined with a fragmented opposition and a European Commission hesitant to speak out against rule of law violations, allowed Orbán to cement his grip on power via repeated constitutional changes. At the same time, the gradual erosion of democratic quality in Hungary occurred against the backdrop of regular elections (albeit of declining quality, as we explain below), with Orbán securing his fourth consecutive mandate in the parliamentary elections of April 2022.Footnote19 Voters thus had regular opportunities to withdraw their support for Fidesz at the ballot box but failed to do so to an electorally meaningful extent.

Mirroring Orbán’s ability to deliberately aggregate different minor cleavages under a common ideological umbrella to establish Fidesz as a dominant political playerFootnote20, we expect voters’ willingness to tolerate democratic backsliding under his rule to result from a similar variety of trade-offs that draw different voter segments to his platform. Still, we assume voters in democracies on average to punish violations of basic liberal democratic norms where political leaders endorse such views. Where elites begin to weaken institutional constraints to concentrate executive power, citizens become the ultimate bulwarks to protect democracy against further erosion.Footnote21 The expectation that citizens with democratic experience are willing to live up to this role forms the baseline hypothesis from which we further theorize potential sources of citizen tolerance for democratic violations.

H1 (authoritarian punishment): Voters are less likely to choose a leader who endorses democratic violations.

The first trade-off we examine concerns a leader’s cultural orientations. A conservative backlash against multiculturalism and immigration has been shown to play a key role in the rise of authoritarian populism.Footnote22 In the post-communist context, there is a longstanding tension between nationalism and the liberal component of democracy that resurfaced at the critical juncture of the EU’s enlargement towards Central and Eastern Europe.Footnote23 Several recent studies highlight how authoritarian-leaning leaders rely upon “ethnopopulism”Footnote24 or “paternalist populism”Footnote25 as an electoral strategy, referring to the protection of traditional values or specific groups of citizens and “ways of life” to justify the erosion of democratic standards. More generally, evidence from cross-sectional surveys suggests that voters with a “protection-based attitude package” combining right-wing cultural and left-wing economic attitudes are more open to endorsing a political leader unconstrained by democratic rules due to their prioritization of social order and economic stability.Footnote26 In sum, certain citizens may prioritize a leader’s culturally conservative orientations over their adherence to established democratic norms. We thus hypothesize:

H2 (value-based priority): Voters tolerate democratic erosion because they value a leader’s degree of cultural conservatism more highly than their respect for democratic procedures.

H3 (economic priority): Voters tolerate democratic erosion because they value a leader’s economic positions more highly than their respect for democratic procedures.

H4 (democratic conceptions priority): Voters tolerate democratic erosion because they value a leader’s democratic priority more highly than their respect for democratic procedures.

First, we examine the relevance of voters’ place of residence. For Hungary specifically, an analysis of the most recent local elections shows a widening urban-rural divide in electoral preferences.Footnote35 More generally, the salience of urban-rural political conflict has grown in recent yearsFootnote36, with political geography becoming an increasingly important predictor of vote choice and a source of democratic vulnerability.Footnote37 Cities are typically thought to host more liberal, cosmopolitan inhabitants who tend to be better educated and economically more well-off than their rural counterparts, resulting in resentmentFootnote38 that can cause rural populations to be more open to authoritarian temptations and notably identity-based manipulation by elites.Footnote39 Accordingly, we expect to see a greater openness to tolerating democratic backsliding among rural citizens.

Second, we expect tolerance of democratic backsliding to vary with respondents’ level of education. Modernization theory views education as the crucial mechanism linking rising economic growth to better democratic outcomes as citizens become more aware of the benefits of democracy and more willing to demand institutional frameworks that enable their effective participation.Footnote40 Inversely, populist voting is disproportionately associated with low education levels.Footnote41 We therefore expect more highly educated citizens to be better able to recognize democratic violations by elected leaders and less susceptible to trading these off against alternative priorities.

Third, we probe the role of economic status when it comes to tolerating democratic violations. We anticipate two potential vulnerabilities: for one, voters of weak economic standing are likely to be more susceptible to targeted benefits in the form of welfare payments to which ruling populists frequently resort to cement their voter base.Footnote42 Moreover, their economic vulnerability may lead them to support a leader who privileges improving outcomes over respecting procedural standards of democracy.

Finally, we analyse the role of religiosity. Cultural conservatism has been shown to be a strong predictor for authoritarian support.Footnote43 Similarly, a nativist worldview that emphasizes ethnic homogeneity and a shared set of moral values often translates into scepticism towards minority rights and executive constraints that underpin liberal democracy.Footnote44 Notably the defence of Christian values promoted by backsliding leadersFootnote45 is thus likely to resonate with voters for whom religion plays an important role in their everyday lives, leading us to expect voters with higher degrees of religiosity to potentially overlook a candidate’s democratic views where they promise to safeguard traditional values.

In sum, we propose a mosaic approach that probes distinct logics determining whether citizens are able and willing to act as bulwarks against democratic backsliding: their capacity to recognize and willingness to punish democratic violations (H1), their preference for alternative positions endorsed by a leader (H2-H4), and the different likelihood of specific subgroups of the population to trade off a leader’s respect for democratic procedures against such alternative benefits (H5-H9, see appendix). To probe the relative weight of these different considerations when it comes to leadership preference, we developed a conjoint experiment which we outline in the following.

Research design and data

Our empirical analysis leverages a candidate choice conjoint experiment, a design often used to alleviate social desirability bias when probing respondents’ views on sensitive topics.Footnote46 We pre-registered the study design and received ethical approval by the ETH Zurich Ethics Commission. The conjoint experiment was embedded into an online survey fielded between 28 December 2021 and 14 January 2022 in Hungary by YouGov’s partner in Central-Eastern Europe, the Warsaw-based market research company Inquiry. Respondents answered general questions on Inquiry’s website and completed the conjoint portion in a survey programmed separately in Qualtrics. The full sample contained 2’004 respondents who were selected to be representative of the general Hungarian population regarding age, gender, residence, and vote choice at the last national election. Following the removal of speeders (fastest 10%), our final sample contained 1’829 respondents. We report sample descriptives and assess sample representativeness in the appendix (see Table A1).Footnote47

Conjoint design

Our conjoint experiment placed respondents not into the traditional scenario of hypothetical elections, but rather asked them to select between two competing profiles of political leaders. This design allows us to integrate broader system-level preferences that it would be less common to find in traditional candidate profiles, which tend to focus on specific policy preferences. displays the full attribute table, which we discuss in the following.

Table 1. Overview of attributes and levels used in conjoint.

Our principal attribute of interest concerns democratic violations, which we measure by providing respondents with three alternative views of judicial independence, a central element of democratic backsliding which others have referred to as “capturing the referees”.Footnote48 Since judicial independence represents a procedural element of democracy that not all respondents may intuitively identify as a democratic violation, this sets a comparatively high threshold for condemnation in comparison to more blatant violations such as electoral manipulation. Our distinct levels for this attribute present a liberal, a majoritarian, and an authoritarian understanding of judicial independence.

To capture alternative benefits respondents may prioritize over a leader’s position on democratic violations, we include three additional attributes. Our attribute on economic buyouts is framed in line with diverse means to achieve economic recovery. We propose direct payments to citizens as the most immediate form of economic benefits promised by a leader, public investments as a more general prospect of government investment, and a third level that proposes reducing bureaucracy as a form of intervention that does not entail direct financial implications for respondents. The attribute on cultural conservatism formulates distinct views regarding the need to protect traditional Hungarian culture and contains one highly conservative position (promoting traditional Hungarian culture), a more intermediary one related to protecting traditional values, and a culturally liberal view that probes openness to new influences. Finally, we include an attribute on democratic conceptions that presents three alternative views of the main priority a government should focus on regarding the broader democratic process. We include a liberal conception emphasizing equal rights for all peopleFootnote49, an egalitarian one that highlights improving living conditions for all citizens, and a majoritarian view that presents implementing the will of the majority as main objective for the government. We explore the empirical distribution of these measures at the beginning of our results section (see ). Besides these items, our conjoint design also includes leaders’ age and gender to offer a more complete profile.

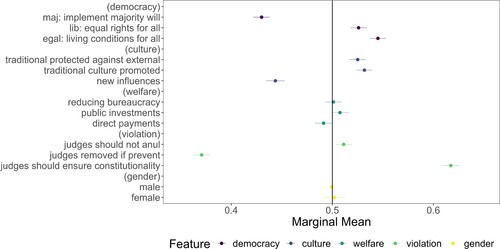

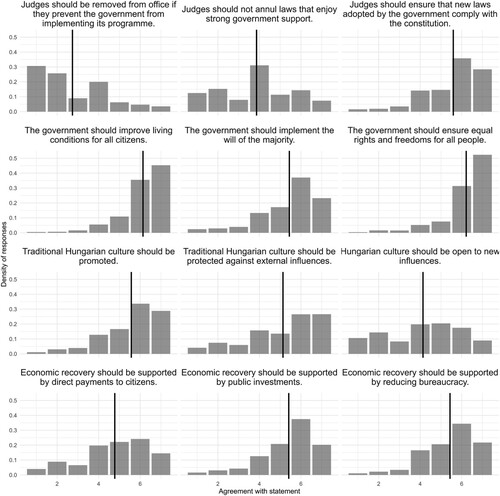

Figure 1. Benchmark questions evaluating attributes outside the conjoint setting.Footnote70

In designing our attribute table for leader profiles, we deliberately chose to omit information on leaders’ partisanship. Many studies focus on partisan polarization to explain why voters fail to punish co-partisans who disregard democratic limits on their power.Footnote50 Where partisan polarization is high, voters prefer to maintain their co-partisan in power rather than seeing the opposition win, preventing them from shifting support towards an alternative leader when their co-partisan violates democratic standards.Footnote51 In the Hungarian case, party-based polarization is rife, with a particularly marked divide between Fidesz supporters and those who back various opposition parties.Footnote52

At the same time, previous findings from conjoint experiments suggest that party labels can crowd out other informationFootnote53, potentially explaining the high salience of partisan polarization as an explanation for citizens’ tolerance towards backsliding that previous studies establish.Footnote54 By leaving out party labels in our conjoint design, we seek to probe how respondents evaluate the substantive elements that may make a leader appealing to citizens. In turn, we do include party preference as a relevant analytical category when it comes to evaluating response patterns among voters.

Our conjoint task prompted respondents to indicate which leader profile they would prefer (forced choice) as well as to rate each profile on a scale from 1 (strongly disapprove) to 7 (strongly approve). Our empirical analysis relies upon respondents’ forced choice between competing leader profiles. Respondents were invited to complete ten separate conjoint tasks. We compared overall choices across the ten choice tasks to those for only the first tasks and found no substantive differences (see Figure A1). Each profile was identified with a neutral label (“Leader A” vs. “Leader B”) and displayed randomized information on six distinct attributes with up to three levels, with the attribute order fully randomized anew for each choice task.

Conjoint analysis

We analyse the findings from our conjoint experiment in line with the specifications set out in our pre-analysis plan. Given the various critiques formulated towards the use of Average Marginal Component Effect (AMCE) to analyse conjoint resultsFootnote55, we report unadjusted marginal means (MM) to provide a descriptive summary of respondent preferences following Leeper et al.Footnote56 to assess our first hypothesis on aggregate patterns. In a second step, we estimate the average component interaction effect (ACIE), defined by Hainmueller et al.Footnote57 to assess whether the presence of certain alternative elements in a leader’s profile may lead respondents to overlook democratic violations more readily, as formulated in Hypotheses 2-4. For this variation, we estimate:

where T1 is a vector of dummy variables for the attribute on democratic violations, while T2 is a vector of dummy variables representing the other three attributes of interest. T1 * T2 is the vector of interactions between T1 and T2. β3 denotes the ACIE.

To test the specific interaction effects between feature levels and the subgroup identifier, we rely on the recommendations for subgroup analyses in conjoint designs developed by Leeper et al..Footnote58 Specifically, we estimate the conditional marginal means for different subgroups and assess the estimated differences between conditional marginal means. Our subgroups of interest are characterized by respondents’ origin (urban/rural), level of education, economic status, and their level of religiosity. Tables A3-A6 also report the differences between these groups in response to the attributes outside of the conjoint (“benchmark questions”) along with the size of each subgroup. We describe our selected cut-offs and report alternative solutions – which do not significantly affect our conclusions – in the appendix (see figures A5 to A7). All results are presented graphically with 95% confidence intervals.

Empirical findings

To probe the extent and reasons of citizen tolerance of democratic backsliding, we analyse the data from our survey experiment in three stages. First, we examine to what extent citizens recognize democratic violations and discuss how such awareness differs across voter groups. Second, we turn to our conjoint findings to evaluate whether endorsing democratic violations entails an electoral punishment of prospective leaders. Finally, we assess which characteristics – at both the leader and the voter level – make respondents more likely to tolerate democratic violations.

Recognizing democratic violations

The subtle and incremental nature of democratic backsliding is often seen as one of the main reasons why citizens fail to rise against political leaders who gradually expand their executive power by dismantling domestic checks and balances.Footnote59 We therefore begin our empirical analysis by exploring the response patterns for the survey questions asking respondents for their evaluation of the different attributes included in the leadership profiles outside of the conjoint setting (“benchmark questions”, see ). For the attribute on democratic violations, which we measure by proposing three distinct views of judicial independence, the aggregate pattern is very clear. On average, respondents evaluate a liberal view, whereby judges engage in constitutional review of new laws, significantly more positively (5.6 on a 1–7 scale) than alternative positions that expect judicial restraint in the case of laws enjoying strong government support (3.9) or endorse the removal of judges who hamper the implementation of the government programme (2.7). This pattern is consistent with only minor deviations across different socio-economic subgroups (see appendix tables A3-A6). We do find a substantial difference based on respondents’ party preference, however: Fidesz supporters tend to evaluate both the majoritarian and the authoritarian position on judicial independence a full point higher than supporters of left parties (see appendix Table A7). This pattern indicates that partisanship, and more specifically co-partisan incumbency, plays a role when it comes to recognizing democratic violations: respondents who favour the current ruling party are less likely to consider infringements by the executive upon judicial independence as problematic.

The picture is less clear-cut when it comes to general conceptions of democracy. On average, respondents rate the liberal and egalitarian view virtually identically (6.2 versus 6.1), with the majoritarian conception following closely (5.4). Again, differences across socio-economic subgroups are negligible and rather minor for party-based differences, with a somewhat higher rating of the liberal conception among left parties (6.4) than for the supporters of Fidesz (5.9) or Jobbik (6.1) (see appendix Table A7). These patterns indicate that at the level of general principles, preference for liberal democracy is much less well anchored in the population than one may expect in a formerly rather consolidated system. Instead, approval rates for both egalitarian and majoritation conceptions indicate certain vulnerabilities with regards to voters’ liberal democratic commitment that may point to alternative benefits they choose to value more highly than formal democratic standards, as we probe in the following.

Punishing democratic violations

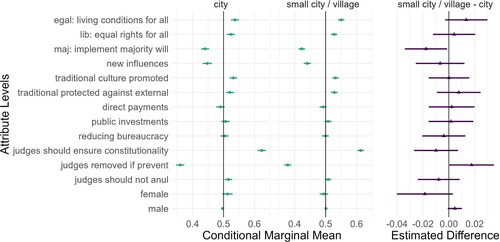

We have established that respondents disapprove of violations of democratic procedures in principle. But do they also punish political leaders for endorsing such violations, preferring leaders who espouse liberal democratic views on judicial independence over those advocating alternative positions? Our first hypothesis concerned respondents’ willingness to withhold support from political leaders who endorse undemocratic positions. Our data confirm this hypothesis: shows the unadjusted marginal means across the full sample. In contrast to the mixed patterns we describe for the ratings of our two democratic attributes in the previous sections, both these attributes play a strong role when it comes to respondent preferences for alternative leader profiles. For democratic violations, respondents are 25 per cent more likely to select a leader who strongly endorses judicial independence than they are to give preference to a leader who favours the removal of judges. All else equal, their preference for a liberal approach towards judges is also 11 per cent higher than for leaders who approve the view that judges should not annul laws that enjoy strong government support.

We find less stark, but still sizeable differences for the attribute on general conceptions of democracy: respondents are 8 per cent less likely to choose leaders holding majoritarian positions compared to those endorsing a liberal view according to which the government should ensure equal rights for all people. Interestingly, leader profiles containing an egalitarian view of democracy – that the government should improve the living conditions for all citizens – fare even better than the liberal level, with a 1.5 per cent higher preference than profiles with liberal views. This slight preference for outcomes – in terms of government performance – over the procedural item focused on rights does not translate, however, into strong variation for our attribute relating to economic benefits, where observed differences between the distinct levels are minimal and none appears statistically significant. Finally, cultural conservatism also seems to play an important role for citizens’ evaluations of political leaders: leaders who express openness to new influences are 7, respectively 7.5 per cent less likely to be selected compared to those who express a strong or moderate willingness to protect traditional values.

Overall, the high condemnation of democratic violations at the aggregate level contrasts with enduring electoral support for Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party during real-life electoral contests in Hungary. Although all opposition parties managed to rally around a single candidate, Péter Márki-Zay, in the latest elections in April 2022, they eventually failed to muster sufficient voter support to replace Orbán at the helm of the government. We therefore turn to a more fine-grained analysis of the characteristics that may lead certain voter groups to choose to overlook democratic violations, distinguishing two levels of analysis: on the one hand, we examine the impact of alternative items contained in a prospective leader”. profile; on the other, we assess how characteristics at the voter level shape evaluations of competing leader profiles.

Who tolerates democratic violations?

To probe alternative priorities respondents might value over a leader’s respect for democratic standards, we estimate the interaction between our attribute on democratic violations and the three other substantive attributes we expect may affect respondents’ evaluations of alternative leader profiles. This means that we test to what extent the punishment of democratic violations depends on which level of the other attributes is present in a given choice task. Interestingly, we note no significant impact for either of the three alternative priorities at the aggregate level (see Figures A2 to A4 in the appendix).

Against the backdrop of our null findings on alternative priorities at the level of the full sample, we proceed to examine possible differences at the subgroup level. Here, we probe more directly the presence of our theorized composite effect of mosaic support, whereby different parts of the population focus on distinct elements of a leader’s profile when choosing to overlook democratic violations. Our expectation is that if we do not find evidence of alternative priorities leading voters to tolerate democratic backsliding across the population, there may be subsections with such preferences that jointly amount to building sufficient electoral support for an authoritarian-leaning leader to arrive – and possibly remain – in power.

Regarding an urban-rural divide, we find only very minor differences between respondents from large towns and cities in comparison to those living in small towns and rural regions (see ). The only statistically significant differences concern the two democratic attributes, with rural respondents slightly more critical of majoritarian positions than urban respondents and slightly more open to the removal of judges (2 per cent difference in each case).Footnote60 The absence of a strong differentiation between the two groups contrasts with the increasing salience attributed to urban-rural divides when it to comes to explaining a range of political behaviours.Footnote61

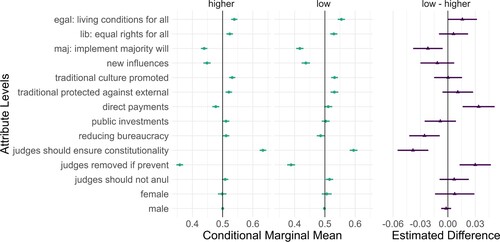

Second, we expected differing education levels to translate into a differential willingness to tolerate democratic violations by political leaders. displays the choice patterns for the two different groups in two separate panels and, in a third panel, shows the estimated difference in marginal means between the two groups. Again, the main difference concerns our democratic attributes: while both groups punish leaders who advocate a removal of judges that prevent the government from implementing its programme, we find that respondents holding at least an A-level degree do so more strongly (plus 4 per cent) than less educated respondents. Inversely, and again as predicted, highly educated respondents value the liberal level of our democratic violations attribute 3 per cent more highly than do less educated ones (see ). Besides, we find a slightly negative view towards direct payments – our measurement of economic buy-outs – among highly educated respondents, whereas less educated respondents view this item more positively, with an estimated difference of 3 per cent between the two groups. An alternative operationalization of levels of education distinguishing respondents with a university degree from those without yields very similar findings (see appendix Figure A6).

One of the central interactions we expected to find was between the economic benefits promised by a leader and their democratic credentials. Whereas we do not find evidence for such openness to economic buyouts for the overall population, our subgroup analysis does suggest that citizens of low economic status are more likely to tolerate democratic violations by political leaders. As before, compares the two different subgroups and displays the estimated differences between them in a third panel. Regarding conceptions of democracy, we find that respondents with a lower economic status are 3 per cent more likely to prefer leader profiles who endorse an egalitarian conception than their counterparts of higher economic standing. This preference is mirrored by a six per cent difference between the two groups when it comes to preference for leaders proposing direct payments vs. more general public investments, with respondents of low economic status showing a clear preference for direct pay-outs compared to respondents of high economic status. We find a similar difference when it comes to democratic violations: although both subgroups disapprove of the removal of judges and prefer leaders who endorse judicial independence, respondents with high economic status punish the former by 3 per cent while being 3 per cent more likely to select liberally minded leaders compared to those of lower economic standing.

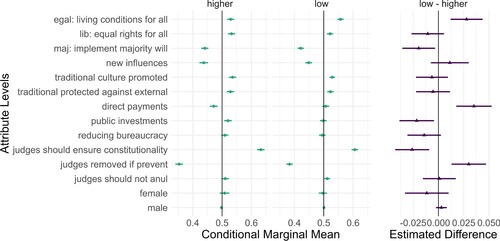

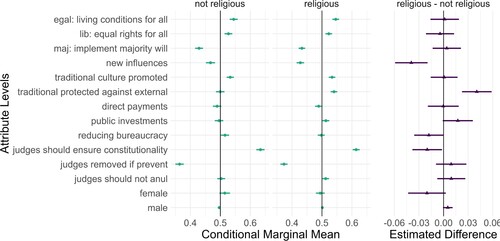

Finally, we further probe our expectation regarding A value-based priority, which did not hold for the overall sample, by comparing response patterns of a subgroup indicating any degree of religiosity to those claiming to be “not religious at all.” shows the ratings for the two subgroups separately and then displays the estimated differences between the two in a third panel. While there are no significant differences between the two groups when it comes to their choice of leaders embracing different conceptions of democracy, we do find that non-religious respondents are two per cent more likely to choose leaders who support a liberal view of judicial independence than their religious counterparts. The starkest difference between these two subgroups, however, concerns their responses to leaders’ different levels of cultural conservatism: while both groups reject openness to new cultural influences and reward a leader’s intention to protect traditional values against external influences, religious respondents are 4 per cent less likely to choose leaders who endorse openness and 4 per cent more likely to prefer a leader who advocates for the protection of traditional values, thereby showing a much stronger preference for cultural conservatism than non-religious ones.

Overall, our subgroup analysis shows only weak evidence for an urban-rural divide when it comes to tolerance for democratic backsliding. We do however find stronger support for our hypotheses regarding the three remaining subgroups, with a greater openness to tolerating democratic backsliding among less educated and less economically privileged respondents, and indications of a value-based trade-off among more religious ones. Although the condemnation of democratic violations is universal, these differential patterns for different subgroups provide support for our expected “mosaic” pattern of support for authoritarian-leaning leaders.

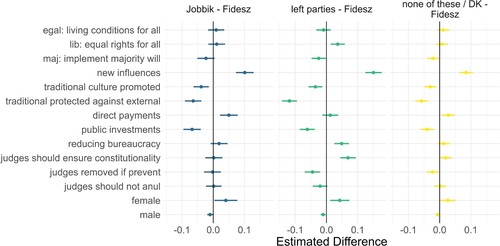

Finally, we explore the impact of partisan dynamics at the respondent level. We had deliberately excluded party labels from our leadership profiles on the assumption that these may dominate respondents’ choices in conjoint tasks while ultimately masking substantive motivations driving their vote choice. We therefore conduct our conjoint analysis based on respondents’ party preference. We report in the subgroup findings based on prospective vote choice in an upcoming election. Fidesz supporters feel particularly strongly about leaders’ cultural orientations: they are 18 per cent less likely to prefer a leader who embraces new cultural influences compared to one who wants to promote traditional culture, and 20 per cent less likely to prefer such a culturally liberal leader to one who wants to protect traditional culture against external threats. Similarly, Fidesz supporters are less likely to punish authoritarian views of judicial independence and less likely to reward liberal positions, although this difference is significant only in comparison to supporters of left parties (see appendix Figure A7). Finally, Fidesz voters reward leaders who promise public investments, a position that receives no support or a slight punishment from respondents favouring other parties. These patterns align with an alternative specification of party preference based on respondents’ reported vote choice during the last parliamentary elections in 2019 (see appendix Figure A8 and A9).

Discussion and conclusion

Our study aimed to tease out the reasons underpinning citizens’ leadership preferences in contexts of democratic backsliding. Going beyond the widespread focus on partisan dynamics, we sought to examine a set of competing explanations in parallel, probing both citizens’ resolve to punish prospective leaders who openly advocate democratic violations as well as a set of alternative benefits voters may choose to prioritize when they decide whether to tolerate democratic backsliding. Focusing on the Hungarian case, our study examines the enduring relevance of the “mosaic cleavage party”Footnote62 coined to describe Fidesz'. earlier transformation into a dominant political force uniting diverse voter groups under a common umbrella. Transferring this concept to the context of democratic backsliding, we probe the more general idea of a composite effect explaining voter tolerance of democratic violations, with different sets of voters being drawn to distinct dimensions of a leader’s profile and potentially trading these off against democratic violations.

Our empirical analysis delivers mixed findings on this question. Perhaps reassuringly, our strongest finding concerns the rejection of leaders who endorse democratic violations, which we confirm in all our analyses. Hungarian respondents clearly punish political leaders who advocate for a weakening of judicial violence and, on average, are not willing to prioritize alternative benefits such as a leader’s culturally conservative views, economic buyouts, or general views of democracy over their respect for basic procedural constraints. This leads us to reject all three of our hypotheses on interaction effects. In turn, our subgroup analysis does produce some evidence of a composition effect that chimes in with previous findings on the importance of clientelismFootnote63 and appeals to traditional valuesFootnote64 that underpin the electoral success of authoritarian populists. Economic buyouts appear somewhat relevant for economically weaker as well as the less educated respondents, who also punish democratic violations less harshly than their respective counterparts. A leader’s cultural orientation is highly important for religious respondents, who also display a slightly weaker preference for candidates holding liberal democratic views of judicial independence.

Overall, our findings thus provide empirical confirmation for previous contentions that Fidesz dominance resulted precisely from its ability to unite a heterogeneous coalition of voters behind it.Footnote65 At the same time, the discrepancy between the strong condemnation of democratic violations found in our experimental patterns and the enduring support Viktor Orbán has been able to garner time and again in real-life electoral contests in Hungary points to the crucial interplay between supply and demand side in contexts of democratic backsliding and notably the deteriorating quality of electoral contests in backsliding countries. In Hungary specifically, Orbán has gradually consolidated his grip on power and tilted the electoral playing field ever more in his favour. Legal scholar Kim Lane Scheppele has described this process as “autocratic legalism”Footnote66 that enables the eventual emergence of a “Frankenstate”Footnote67 in which seemingly minor individual reforms eventually amount to a thoroughly transformed – and considerably less democratic – political system. Specifically with regards to elections, repeated reforms of the electoral process have progressively limited the ability of the opposition to make inroads, with the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE-ODIHR) raising significant concerns and qualifying both the 2014 and 2018 national elections as “free but not fair”.Footnote68 Hence, the apparent contradiction between our experimental patterns and real-life enduring electoral support for Orbán may capture precisely the gap between voters’ democratic preferences and the systemic hurdles they face in translating them into electoral outcomes: where democratic backsliding has become entrenched, overturning authoritarian-leaning leadership at the ballot box may become increasingly unlikely. Accounting for the degree of electoral freedom in a given country – possibly by comparing different cases where free and fair elections are present to divergent extents – may help make sense of how survey-based responses relate to real-life constraints on citizens’ ability to hold backsliding governments to account.

Besides, our findings also point to certain methodological limitations in the ways we study voter behaviour in backsliding contexts. The prominent use of experimental research can only incompletely reflect actual electoral decisions in that, by virtue of necessity, it presents democratic violations in much starker terms than voters may expect to be confronted with in the real world. In practice, the incremental nature of democratic backsliding is likely to be too subtle for voters to fully grasp what is happening until it is too late. Besides, backsliding leaders generally do not tend to engage in open advocacy of democratic violations, possibly leading part of the electorate to simply fail to recognize such intentions which we lay bare in a very direct way in our conjoint experiment. While Orbán did openly embrace the concept of “illiberal democracy” initially, he never advocated directly for a dismantling of democratic safeguards, but instead took care to justify his reforms by reference to similar arrangements in other countries. Such justifications – both democratically grounded and openly undemocratic ones – could be integrated into future experimental research to assess how they affect voters’ tolerance for the proposed measures. Efforts in this direction would do well to incorporate a range of possible elite justifications for democratic violations. These should probe not only trade-offs between cultural conservatism and the respect for democratic procedures, but also examine whether culturally liberal-minded voters are willing to overlook democratic transgressions where a candidate pledges to serve their political agenda, for instance with regards to minority protection or the adoption of progressive family policies.

Finally, our study points to an important practical implication when it comes to preventing the deepening and ultimate entrenchment of democratic backsliding. The gradual deepening and eventual entrenchment of democratic backsliding in Hungary suggest that it is important to intervene early to counter political leaders’ efforts to dismantle checks and balances. Where unchecked autocratisation increases the hurdles for citizens to act as effective bulwarks for democracy, efforts to dismantle democratic safeguards may continue to unfold until the very electoral process itself as the core of the democratic system is no longer reflective of voters’ democratic preferences. Ultimately, one plausible interpretation of our findings is that citizens may not be unwilling, but structurally unable to overturn authoritarian-leading leadership due to manipulations of the electoral process. At the same time, interventions to counter backsliding trends need to be carefully calibrated, with a comparative study finding moderate attempts to push back against executive aggrandizement to be considerably more successful than opposition efforts to irregularly remove incumbents from office.Footnote69 Where domestic opposition players and international actors can join forces to call out autocratisation at an early stage, such contestation may prevent the process of democratic erosion from reaching a point where a return to democracy by regular electoral means becomes increasingly elusive.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for comments received on previous versions of this manuscript by participants of the University of Zurich pre-publication seminar and the ECPR Joint Sessions workshop “Domestic Responses to Democratic Backsliding: Citizens, Civil Society, and Parties.” We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Natasha Wunsch

Natasha Wunsch is Professor of European Studies at the University of Fribourg and Senior Research at ETH Zurich.

Theresa Gessler

Theresa Gessler is Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics at the European University Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder).

Notes

1 Greskovits, “The Hollowing and Backsliding of Democracy in East Central Europe”; McCoy, Rahman and Somer, “Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy”; Carey et al., “Searching for Bright Lines in the Trump Presidency”.

2 Ahlquist et al., “How do voters perceive changes to the rules of the game? Evidence from the 2014 Hungarian elections”; Mazepus and Toshkov, “Standing up for democracy? Explaining citizens’ support for democratic checks and balances”; Wunsch, Jacob and Derksen, “The Demand Side of Democratic Backsliding”.

3 Schedler, “What Do We Know about Resistance to Democratic Subversion?,” 8.

4 Graham and Svolik, “Democracy in America? Partisanship, Polarization, and the Robustness of Support for Democracy in the United States”; Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay, “Democratic Hypocrisy”; Gidengil, Stolle and Bergeron-Boutin, “The Partisan Nature of Support for Democratic Backsliding”.

5 Svolik, “Polarization versus Democracy”.

6 Grossman et al., “The Majoritarian Threat to Liberal Democracy”; Wunsch, Jacob and Derksen, “The Demand Side of Democratic Backsliding”.

7 Mudde, Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe, 225.

8 Halikiopoulou and Vlandas, “When economic and cultural interests align”; Damhuis, Roads to the radical right.

9 Scheppele, “The Rule of Law and the Frankenstate”.

10 Vegetti, “The Political Nature of Ideological Polarization”; Fowler, “Concentrated orange”.

11 Enyedi, “The role of agency in cleavage formation,” 701.

12 Aspinall et al., “Elites, masses, and democratic decline in Indonesia”; Fossati, Muhtadi and Warburton, “Why democrats abandon democracy”; Ireneusz P. Karolewski, “Towards a Political Theory of Democratic Backsliding? Generalising the East Central European Experience”.

13 Ágh, “The Decline of Democracy in East-Central Europe”; Bogaards, “De-democratization in Hungary”; Bozóki and Hegedűs, “An externally constrained hybrid regime”.

14 Freedom House, “Freedom in the World”; Maerz et al., “State of the world 2019”.

15 Székely-Doby, “Rent creation, clientelism and the emergence of semi-democracies,” 392.

16 Renata Uitz, “Hungary”.

17 Batory, “Populists in government? Hungary's “system of national cooperation”; Gessler and Kyriazi, “Hungary – A Hungarian Crisis or Just a Crisis in Hungary?”.

18 Bakke and Sitter, “The EU”s Enfants Terribles,” 12.

19 Priebus and Végh, “Hungary after the General Elections. Down the Road of Autocratisation?”.

20 Enyedi, “The role of agency in cleavage formation”.

21 Weingast, “The Political Foundations of Democracy and the Rule of the Law”; Karolewski, “Towards a Political Theory of Democratic Backsliding? Generalising the East Central European Experience”.

22 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash.

23 Hloušek and Fiala, “The future of Europe and the role of Eastern Europe in its past, present, and future 2. A new critical juncture? Central Europe and the impact of European integration”.

24 Vachudova, “Ethnopopulism and democratic backsliding in Central Europe”.

25 Enyedi, “Right-wing authoritarian innovations in Central and Eastern Europe”.

26 Malka et al., “Who Is Open to Authoritarian Governance within Western Democracies?,” 2.

27 Singer, “Delegating Away Democracy”; Landwehr and Leininger, “Instrumental or procedural democrats? The evolution of procedural preferences after democratization”.

28 Mazepus and Toshkov, “Standing up for democracy? Explaining citizens’ support for democratic checks and balances”.

29 Mares and Young, Conditionality and coercion; Székely-Doby, “Rent creation, clientelism and the emergence of semi-democracies”.

30 Szikra and Öktem, “An illiberal welfare state emerging? Welfare efforts and trajectories under democratic backsliding in Hungary and Turkey”.

31 Schedler and Sarsfield, “Democrats with adjectives”; Canache, “Citizens’ Conceptualizations of Democracy”.

32 Grossman et al., “The Majoritarian Threat to Liberal Democracy”; Wunsch, Jacob and Derksen, “The Demand Side of Democratic Backsliding”.

33 Landwehr and Leininger, “Instrumental or procedural democrats? The evolution of procedural preferences after democratization”.

34 See also Ferrín and Kriesi, How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. On social democratic conception of democracy.

35 Collini, “The Hungarian Local Elections of 2019”.

36 Rodden, Why cities lose.

37 Mettler and Brown, “The Growing Rural-Urban Political Divide and Democratic Vulnerability”.

38 Foa and Wilmot, “The West Has a Resentment Epidemic”.

39 Diamond, “Breaking Out of the Democratic Slump,” 39–40; Huijsmans et al., “Are cities ever more cosmopolitan? Studying trends in urban-rural divergence of cultural attitudes”.

40 Lipset, “Some Social Requisites of Democracy”; Welzel and Inglehart, “The role of ordinary people in democratization”.

41 Kaltwasser and Hauwaert, “The populist citizen”; Markowski, “Plurality support for democratic decay”.

42 Kim, “Because the homeland cannot be in opposition”; Markowski, “Plurality support for democratic decay”.

43 Malka et al., “Who Is Open to Authoritarian Governance within Western Democracies?”.

44 Kokkonen and Linde, “Nativist attitudes and opportunistic support for democracy”.

45 Bill and Stanley, “Whose Poland is it to be? PiS and the struggle between monism and pluralism”; Krekó and Enyedi, “Orbán’s Laboratory of Illiberalism”.

46 Horiuchi, Markovich and Yamamoto, “Does Conjoint Analysis Mitigate Social Desirability Bias?”.

47 There is a slight underrepresentation of older respondents in our sample that is most likely due to the online nature of our survey and in line with other surveys relying on the Internet. See full overview in supplementary material.

48 Levitsky and Ziblatt, How democracies die.

49 We choose the formulation “people” (ember) rather than “citizens” (polgár) to emphasize that equal rights should not only apply to the narrow group of Hungarian nationals.

50 Graham and Svolik, “Democracy in America? Partisanship, Polarization, and the Robustness of Support for Democracy in the United States”; Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay, “Democratic Hypocrisy”; Svolik, “When Polarization Trumps Civic Virtue”.

51 McCoy and Somer, “Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarization and How It Harms Democracies”.

52 Gessler and Wunsch, A new regime divide? Partisan affect and attitudes towards democratic backsliding.

53 Kirkland and Coppock, “Candidate Choice Without Party Labels”.

54 Gidengil, Stolle and Bergeron-Boutin, “The Partisan Nature of Support for Democratic Backsliding”; Graham and Svolik, “Democracy in America? Partisanship, Polarization, and the Robustness of Support for Democracy in the United States”; Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay, “Democratic Hypocrisy”.

55 Ganter, “Identification of Preferences in Forced-Choice Conjoint Experiments”; Zhirkov, “Estimating and Using Individual Marginal Component Effects from Conjoint Experiments”.

56 Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley, “Measuring Subgroup Preferences in Conjoint Experiments”.

57 Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto, “Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis”.

58 Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley, “Measuring Subgroup Preferences in Conjoint Experiments”.

59 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding”; Waldner and Lust, “Unwelcome Change”.

60 See appendix Figure A5 for an alternative specification that yields no statistically significant differences between the two groups.

61 Mettler and Brown, “The Growing Rural-Urban Political Divide and Democratic Vulnerability”; Broz, Frieden and Weymouth, “Populism in Place”; Huijsmans et al., “Are cities ever more cosmopolitan? Studying trends in urban-rural divergence of cultural attitudes”.

62 Enyedi, “The role of agency in cleavage formation”.

63 Mares and Young, Conditionality and coercion; Székely-Doby, “Rent creation, clientelism and the emergence of semi-democracies”.

64 Enyedi, “Right-wing authoritarian innovations in Central and Eastern Europe”.

65 Fowler, “Concentrated orange”; Enyedi, “The role of agency in cleavage formation”.

66 Scheppele, “Autocratic Legalism”.

67 Scheppele, “The Rule of Law and the Frankenstate”.

68 Hegedűs and Levine, “Hungary monitors not enough to stop first ‘rigged’ election in EU”.

69 Cleary and Öztürk, “When Does Backsliding Lead to Breakdown? Uncertainty and Opposition Strategies in Democracies at Risk”.

70 The precise question wording was “To what extent do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements?” See also average ratings in Table A2 in supplementary material.

Bibliography

- Ahlquist, John S., Nahomi Ichino, Jason Wittenberg, and Daniel Ziblatt. “How do voters perceive changes to the rules of the game? Evidence from the 2014 Hungarian Elections.” Journal of Comparative Economics 46, no. 4 (2018): 906–919.

- Aspinall, Edward, Diego Fossati, Burhanuddin Muhtadi, and Eve Warburton. “Elites, masses, and democratic decline in Indonesia.” Democratization 27, no. 4 (2020): 505–526.

- Ágh, Attila. “The Decline of Democracy in East-Central Europe.” Problems of Post-Communism 63, no. 5-6 (2016): 277–287.

- Bakke, Elisabeth, and Nick Sitter. “The EU’s Enfants Terribles: Democratic Backsliding in Central Europe since 2010.” Perspectives on Politics (2022): 1–16.

- Batory, Agnes. “Populists in Government? Hungary's “System of National Cooperation”.” Democratization 23, no. 2 (2016): 283–303.

- Bermeo, Nancy. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27, no. 1 (2016): 5–19.

- Bill, Stanley, and Ben Stanley. “Whose Poland is it to be? PiS and the struggle between monism and pluralism.” East European Politics 36, no. 3 (2020): 378–394.

- Bogaards, Matthijs. “De-democratization in Hungary: Diffusely Defective democracy.” Democratization 25, no. 8 (2018): 1481–1499.

- Bozóki, András, and Dániel Hegedűs. “An externally constrained hybrid regime: Hungary in the European Union.” Democratization 25, no. 7 (2018): 1173–1189.

- Broz, J. L., Jeffry Frieden, and Stephen Weymouth. “Populism in Place: The Economic Geography of the Globalization Backlash.” International Organization 75, no. 2 (2021): 464–494.

- Canache, Damarys. “Citizens’ Conceptualizations of Democracy.” Comparative Political Studies 45, no. 9 (2012): 1132–1158.

- Carey, John M., Gretchen Helmke, Brendan Nyhan, Mitchell Sanders, and Susan Stokes. “Searching for Bright Lines in the Trump Presidency.” Perspectives on Politics 17, no. 3 (2019): 699–718.

- Cleary, Matthew R., and Aykut Öztürk. “When Does Backsliding Lead to Breakdown? Uncertainty and Opposition Strategies in Democracies at Risk.” Perspectives on Politics 20, no. 1 (2022): 205–221.

- Collini, Mattia. “The Hungarian Local Elections of 2019: Unity Makes Strength.” Romanian Political Science Review 21, no. 1 (2021): 193–209.

- Damhuis, Koen. Roads to the radical right: Understanding different forms of electoral support for radical right-wing parties in France and the Netherlands. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Diamond, Larry. “Breaking Out of the Democratic Slump.” Journal of Democracy 31, no. 1 (2020): 36–50.

- Diamond, Larry J., and Marc F. Plattner, eds. How People View Democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

- Enyedi, Zsolt. “The role of agency in cleavage formation.” European Journal of Political Research 44, no. 5 (2005): 697–720.

- Enyedi, Zsolt. “Right-wing Authoritarian Innovations in Central and Eastern Europe.” East European Politics 36, no. 3 (2020): 363–377.

- Ferrín, Mónica, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Foa, Roberto S., and Jonathan Wilmot. “The West Has a Resentment Epidemic.” Foreign Policy (September 18, 2019.

- Fossati, Diego, Burhanuddin Muhtadi, and Eve Warburton. “Why Democrats Abandon Democracy: Evidence from Four Survey Experiments.” Party Politics (2021).

- Fowler, Brigid. “Concentrated orange: Fidesz and the remaking of the Hungarian centre-right, 1994–2002.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 20, no. 3 (2004): 80–114.

- Freedom House. “Freedom in the World: A Leaderless Struggle for Democracy”. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/FIW_2020_REPORT_BOOKLET_Final.pdf (accessed March 13, 2020).

- Ganter, Flavien. “Identification of Preferences in Forced-Choice Conjoint Experiments: Reassessing the Quantity of Interest.” Political Analysis (2021): 1–15.

- Gessler, Theresa, and Anna Kyriazi. “Hungary – A Hungarian Crisis or Just a Crisis in Hungary?” In European Party Politics in Times of Crisis, edited by Swen Hutter, and Hanspeter Kriesi, 167–188. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Gessler, Theresa, and Natasha Wunsch. A new regime divide? Partisan affect and attitudes towards democratic backsliding. 2023. https://osf.io/nbwmj/.

- Gidengil, Elisabeth, Dietlind Stolle, and Olivier Bergeron-Boutin. “The Partisan Nature of Support for Democratic Backsliding: A Comparative Perspective.” European Journal of Political Research 61, no. 4 (2022): 901–929.

- Graham, Matthew H., and Milan W. Svolik. “Democracy in America? Partisanship, Polarization, and the Robustness of Support for Democracy in the United States.” American Political Science Review 114, no. 2 (2020): 392–409.

- Greskovits, Béla. “The Hollowing and Backsliding of Democracy in East Central Europe.” Global Policy 6, no. Suppl.1 (2015): 28–37.

- Grossman, Guy, Dorothy Kronick, Matthew Levendusky, and Marc Meredith. “The Majoritarian Threat to Liberal Democracy.” Journal of Experimental Political Science (2021): 1–10.

- Hainmueller, Jens, Daniel J. Hopkins, and Teppei Yamamoto. “Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis: Understanding Multidimensional Choices via Stated Preference Experiments.” Political Analysis 22, no. 1 (2014): 1–30.

- Halikiopoulou, Daphne, and Tim Vlandas. “When economic and cultural Interests align: the anti-immigration voter coalitions driving far right party success in Europe.” European Political Science Review 12, no. 4 (2020): 427–448.

- Hegedűs, Dániel, and David Levine. “Hungary Monitors not Enough to Stop First ‘Rigged’ Election in EU”. EU Observer, February 16, 2022. https://euobserver.com/opinion/154355.

- Hloušek, Vít, and Petr Fiala. “The Future of Europe and the role of Eastern Europe in its past, present, and future 2. A New critical juncture? Central Europe and the impact of European integration.” European Political Science 20, no. 2 (2021): 243–253.

- Horiuchi, Yusaku, Zachary Markovich, and Teppei Yamamoto. “Does Conjoint Analysis Mitigate Social Desirability Bias?” Political Analysis (2021): 1–15.

- Huijsmans, Twan, Eelco Harteveld, Wouter van der Brug, and Bram Lancee. “Are cities ever more cosmopolitan? Studying Trends in Urban-Rural Divergence of Cultural Attitudes.” Political Geography 86 (2021): 102353.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. European Party Politics in Times of Crisis. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Karolewski, Ireneusz P. “Towards a Political Theory of Democratic Backsliding? Generalising the East Central European Experience.” In Illiberal Trends and Anti-EU Politics in East Central Europe, edited by Astrid Lorenz, and Lisa H. Anders. Palgrave Studies in European Union Politics, 301–321. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021.

- Kim, Seongcheol. “ … Because the Homeland Cannot be in Opposition: Analysing the Discourses of Fidesz and Law and Justice (PiS) from Opposition to Power.” East European Politics 37, no. 2 (2021): 332–351.

- Kirkland, Patricia A., and Alexander Coppock. “Candidate Choice Without Party Labels.” Political Behavior 40, no. 3 (2018): 571–591.

- Kokkonen, Andrej, and Jonas Linde. “Nativist Attitudes and Opportunistic Support for Democracy.” West European Politics (2021): 1–24.

- Krekó, Péter, and Zsolt Enyedi. “Orbán's Laboratory of Illiberalism.” Journal of Democracy 29, no. 3 (2018): 39–51.

- Landwehr, Claudia, and Arndt Leininger. “Instrumental or procedural democrats? The evolution of procedural preferences after democratization.” Political Research Exchange 1, no. 1 (2019): 1–19.

- Leeper, Thomas J., Sara B. Hobolt, and James Tilley. “Measuring Subgroup Preferences in Conjoint Experiments.” Political Analysis 28, no. 2 (2020): 207–221.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies die. New York: Crown, 2018.

- Lipset, Seymour M. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” American Political Science Review 53, no. 1 (1959): 69–105.

- Lorenz, Astrid, and Lisa H. Anders, eds. Illiberal Trends and Anti-EU Politics in East Central Europe. Palgrave Studies in European Union Politics. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021.

- Maerz, Seraphine F., Anna Lührmann, Sebastian Hellmeier, Sandra Grahn, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “State of the world 2019: autocratization surges – resistance grows.” Democratization (2020): 1–19.

- Malka, Ariel, Yphtach Lelkes, Bert N. Bakker, and Eliyahu Spivack. “Who Is Open to Authoritarian Governance within Western Democracies?” Perspectives on Politics (2020): 1–20.

- Mares, Isabela, and Lauren E. Young. Conditionality and Coercion: Electoral Clientelism in Eastern Europe. First Edition. Oxford Studies in Democratization. Oxford United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Markowski, Radoslaw. “Plurality support for democratic decay: the 2019 Polish parliamentary election.” West European Politics 43, no. 7 (2020): 1513–1525.

- Mazepus, Honorata, and Dimiter Toshkov. “Standing up for democracy? Explaining citizens' support for democratic checks and balances.” Comparative Political Studies 55, no. 8 (2022): 1271–1297.

- McCoy, Jennifer, Tahmina Rahman, and Murat Somer. “Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy: Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities.” American Behavioral Scientist 62, no. 1 (2018): 16–42.

- McCoy, Jennifer, and Murat Somer. “Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarization and How It Harms Democracies: Comparative Evidence and Possible Remedies.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681, no. 1 (2019): 234–271.

- Mettler, Suzanne, and Trevor Brown. “The Growing Rural-Urban Political Divide and Democratic Vulnerability.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 699, no. 1 (2022): 130–142.

- Morlino, Leonardo, and Wojciech Sadurski, eds. Democratization and the European Union: Comparing Central and Eastern European Post-Communist Countries. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Mudde, Cas. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Priebus, Sonja, and Zsuzsanna Végh. “Hungary after the General Elections. Down the Road of Autocratisation?” Südosteuropa Mitteilungen 62, no. 3 (2022.

- Rodden, Jonathan. Why Cities Lose: The Deep Roots of the Urban-Rural Political Divide. New York: Basic Books, 2019.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal, and Steven M. van Hauwaert. “The Populist Citizen: Empirical Evidence from Europe and Latin America.” European Political Science Review 12, no. 1 (2020): 1–18.

- Schedler, Andreas. “What Do We Know about Resistance to Democratic Subversion?” Annals of Comparative Democratization 17, no. 1 (2019): 4–8.

- Schedler, Andreas, and Rodolfo Sarsfield. “Democrats with adjectives: Linking direct and indirect measures of democratic support.” European Journal of Political Research 46, no. 5 (2007): 637–659.

- Scheppele, Kim L. “The Rule of Law and the Frankenstate: Why Governance Checklists Do Not Work.” Governance 26, no. 4 (2013): 559–562.

- Scheppele, Kim L. “Autocratic Legalism.” University of Chicago Law Review 85, no. 2 (2018.

- Simonovits, Gabor, Jennifer McCoy, and Levente Littvay. “Democratic Hypocrisy and Out-Group Threat: Explaining Citizen Support for Democratic Erosion.” The Journal of Politics 84, no. 3 (2022): 1806–1811.

- Singer, Matthew. “Delegating Away Democracy: How Good Representation and Policy Successes Can Undermine Democratic Legitimacy.” Comparative Political Studies 51, no. 13 (2018): 1754–1788.

- Svolik, Milan W. “Polarization versus Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 30, no. 3 (2019): 20–32.

- Svolik, Milan W. “When Polarization Trumps Civic Virtue: Partisan Conflict and the Subversion of Democracy by Incumbents.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 15, no. 1 (2020): 3–31.

- Székely-Doby, András. “Rent creation, clientelism and the emergence of semi-democracies: the case of Hungary.” East European Politics 37, no. 2 (2021): 379–399.

- Szikra, Dorottya, and Kerem G. Öktem. “An illiberal welfare state emerging? Welfare efforts and trajectories under democratic backsliding in Hungary and Turkey.” Journal of European Social Policy (2022): 095892872211413.

- Uitz, Renata. “Hungary: High Hopes Revisited.” In Democratization and the European Union: Comparing Central and Eastern European Post-Communist Countries, edited by Leonardo Morlino, and Wojciech Sadurski, 45–69. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Vachudova, Milada A. “Ethnopopulism and democratic backsliding in Central Europe.” East European Politics 36, no. 3 (2020): 318–340.

- Vegetti, Federico. “The Political Nature of Ideological Polarization: The Case of Hungary.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681, no. 1 (2019): 78–96.

- Waldner, David, and Ellen Lust. “Unwelcome Change: Coming to Terms with Democratic Backsliding.” Annual Review of Political Science 21, no. 5 (2018): 93–113.

- Weingast, Barry R. “The Political Foundations of Democracy and the Rule of the Law.” American Political Science Review 91, no. 2 (1997): 245–263.

- Welzel, Christian, and Ronald Inglehart. “The Role of Ordinary People in democratization.” In How People View Democracy, edited by Larry J. Diamond, and Marc F. Plattner, 16–30. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

- Wunsch, Natasha, Marc S. Jacob, and Laurenz Derksen. “The Demand Side of Democratic Backsliding: How Divergent Understandings of Democracy Shape Political Choice” (2022). https://osf.io/c64gf/.

- Zhirkov, Kirill. “Estimating and Using Individual Marginal Component Effects from Conjoint Experiments.” Political Analysis 30, no. 2 (2022): 236–249.