ABSTRACT

The amount of information available to citizens due to global digitization and new technologies is unprecedented. However, in established democracies where access to alternative sources of information is guaranteed and educational levels are high, we witness a rise in attitudes and actions that threaten democratic foundations. Some citizens succumb to misinformation that has led them down the path of radicalization and violence; others withdraw completely from political life. How do we explain these developments? Building on democratic theory and the concepts of informational learned helplessness and selective exposure, we introduce a theoretical framework that connects digitization and digital technologies to attitudes and behaviour that threaten democracy even before democratic decay manifests. We argue that AI-assisted digital technologies expose societies to an abundance of contradictory information, limit citizens’ ability to assess their trustworthiness, and reinforce the tailored dissemination of misinformation. We present the US and Germany as empirical plausibility probes that show how these features drive some citizens towards informational agnosticism, which results in de-politicization and political apathy. Others might become misbelievers who display negative attitudes towards democracy and/or engage in anti-democratic actions. Our probe offers an initial empirical illustration that provides a basis for further systematic investigations of digital technology’s effects on democracy.

Digitization, information, and democratic decay

Democratic theory has long stressed the centrality of information for the proper functioning of democracy.Footnote1 When governments restrict access to information, citizens lack a fundemental requisite to meaningful participation and informed decision making. Free access to information has, therefore, been theorized to be conducive rather than detrimental to democracy.Footnote2 But while digitization and artificial intelligence (AI) have exponentially expanded access to varieties of information, they have also posed threats to democracy in different places.Footnote3 From the UK’s Brexit referendum to mob lynching in India, these developments have aggravated trends of what scholars have termed “democratic regression”, “erosion”, “backsliding”, “de-democratization”, or “authoritarianization”.Footnote4

We know that digital technologies and AI contribute to misinformed attitudes and anti-democratic behaviour. In this contribution, we propose an analytical framework that provides the hitherto missing link between digitization and AI on the one hand and such attitudes and behaviour on the socio-psychological level on the other. We suggest an integrated framework for analysing the origins of democratic decay that starts not with misinformation and anti-democratic behaviour, but with where these dispositions stem from. In doing so, we highlight political agnosticism and apathy as symptoms of the digital transformation that have important ramifications for democracy.

Digitization and AI-assisted technologies increase citizens’ costs of identifying reliable information which can cause states of selective exposureFootnote5 and informational learned helplessness (ILH).Footnote6 This induces citizens to either become misinformed or politically apathetic. We link misinformation and political apathy back to elements of democratic theory and political regime theory to explain why and how they pose dangers to democracy. To be sure, the variables that determine the resilience of any given democracy to such threats are manifold, and it is beyond the scope of this contribution to examine them in depth. While these variables determine whether only some modest decay or a full-fledged breakdown of democracy will occur, this is not our focus.Footnote7 Instead, we aim to complete the explanatory chain that links AI and digitization more broadly to the phenomena of democratic decay by showing how technology creates psychopolitical dispositions among citizens; these dispositions can, even if not immediately, become a manifest danger to democratic regimes up to the point of democratic breakdown.

While the breakdown of trust in the possibility that truth is knowable can lead to extremism,Footnote8 anti-democratic violence, and political disengagement,Footnote9 research does not holistically capture technology’s influence on the emergence of attitudes and behaviour that put democracy under stress. Scholars have also explored isolated instances (e.g. electoral processes and outcomes) in which misinformationFootnote10 harms specific democratic elements or procedures.Footnote11 However, these works remain concentrated on isolated aspects of technology and/or individual elements of democracy, thereby ignoring the larger causal chain. From a systemic perspective, digitally induced democratic decay cannot be reduced to the realms of elections, disinformation, or misbelief, despite the relevance of these realms for democracy. Others have used a “deliberative systems” approach to theorize and examine how disinformation threatens democracy by inducing “anti-deliberative effects”.Footnote12 We concur with these scholars that it is important to specify “which democratic goods are at risk from disinformation, and how they are put at risk”,Footnote13 and to consider systemic interactions.Footnote14 However, beyond specific narratives of misinformation and technical elements like social media algorithms, it is necessary to systematically link the numerous elements of the epiphenomenological level of digitization back to democratic theory and political regime theory to confidently assess whether threats to democracy emerge, and to determine whether they are systemic or ephemeral.

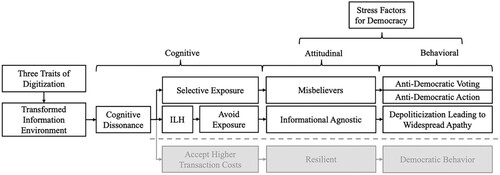

We identify three features inherent to digitized information production, dissemination, and consumption that have transformed citizens’ information environment. Section 2 shows how these traits cause a cognitive dissonance that can (1) make parts of the population agnostic about the very existence and relevance of “facts”, (2) predispose other parts of the population to become misinformed through selective exposure to information that fit their pre-existing ideas; others (3) bear the higher transaction costs of verifying information to resolve the dissonance.Footnote15 Section 3, then, explains how such attitudes and the resulting behaviour endanger democracy by linking them to democratic theory. Section 4 empirically validates our analytical framework through a plausibility probe into the 2021 US Capitol Hill riots and the 2020 anti-COVID protests at the German Reichstag. While such a probe is not a rigorous hypothesis test, it does provide anecdotal evidence and illustrates our claim about how digitization facilitates misbelief and, subsequently, anti-democratic behaviour, or agnosticism and political apathy. While our article suggests a novel and more comprehensive causal chain, only further research will be able to verify such claims through more rigorous empirical testing. Yet, in our view, it is high time that an integrated view and explanation of how democratic decay actually starts and comes about is proposed at all, so that it can be put under closer scrutiny by the scholarly community. A discussion of the implications of our findings for future research on how digital processes may cause decay or breakdown concludes this contribution, together with a call for establishing more fine-grained early-warning systems that alert us to threats to democracy we cannot measure adequately so far – precisely because we have been lacking an explanation that comprehensively links digitization to democratic decay.

How digitization transforms citizens’ information environment

Three features of digital technologies affect the nature of information and how citizens consume them: (1) abundance of contradictory information; (2) decreasing ability of consumers to assess its truthfulness; and (3) AI-assisted algorithmic targeting of users with personalized content. These developments occur because of lagging public oversight over the digital sphere that is amplified by political-economic dynamics by which commercial interests (ab)use the still largely unregulated digital space. Together, they transform the informational environment that can lead citizens to embrace misinformation or become doubtful of the existence of truth altogether.

First, digital technologies magnify the abundance by which contradictory information reaches citizens.Footnote16 While increasing the pervasiveness of information, they also diversify narratives by simultaneously turning information consumers into information producers. Users not only have a myriad of choices to express and share their preferences, but they are also able to alter the content of the information they disseminate, forward, or re-post.Footnote17 This results, first, in Chinese-whispers effects and, second, in the impossibility of identifying the original source of information. Consequently, unprecedented amounts of contradictory accounts of reality overwhelm citizens. Social media platforms’ strategies to generate ever more user data to target consumers with fine-tuned appealing narrativesFootnote18 exacerbate that trend.

Before the digital revolution, citizens were better able to identify the origin of information, which made it easier to evaluate its reliability and sincerity. By contrast, when information is created and disseminated by many users on numerous digital platforms, it becomes harder (and often impossible) for them to identify its sources. Furthermore, digital image and audio processing technology have immensely enhanced the sophistication of fabrications and, therefore, thwarted citizens’ abilities to distinguish reality from fabrication. Competitive market mechanisms incentivize tech companies to design cutting-edge products, which further enhances the technical possibilities of creating AI-assisted deep fakes that help legitimize fringe beliefs. It is, therefore, not surprising that Europeans state that “helping citizens to better identify disinformation” is the most important public measure authorities should take against the spread of falsehood.Footnote19 Digital technologies thus lower the costs of access to information, but counterintuitively, dramatically raise the transaction costs of being correctly informed; they subject wide segments of society to unprecedented difficulties in assessing the accuracy of contradictory information to which they are exposed.

Third, AI-based, self-learning algorithms provide users on digital devices with targeted content. This aggravates both the likelihood of believing misinformation and, depending on the design and purpose of the algorithm, an abundance of contradictory information: Some algorithms promote controversial content, misinformation, and conspiracy beliefs that have led to political polarization and even calls for violence.Footnote20 Citizens thus experience a psychologically and emotionally challenging overkill of contradictory claims to “truth”. Other algorithms, however, rely on the “familiarity effect” and promote content consonant with worldviews that resonate in users’ close circles of family and friends – which ultimately contributes to an increase in (mis-)informationFootnote21 and facilitates the emergence of the so-called “filter bubbles”.

These three features inherent to digitized information environments are structurally reproduced as digital technologies become commodified products and services designed to generate profits.Footnote22 Social media platforms and websites generate revenue through donations, subscriptions, advertisements, and data mining – which all depend on traffic.Footnote23 To increase traffic, platforms routinely employ affirmative or polarizing algorithms, or a mix thereof – irrespective of adverse socio-political outcomes.Footnote24

Massive quantities of information, algorithmic targeting, and a reduced ability to assess truthfulness appear most prevalent on social media, where lies spread faster than truths. Footnote25 However, they pervade the entire digitized information environment,Footnote26 including devices like smartphones that use algorithms for data mining and usage maximization. These are designed to incentivize users to participate in the pluralized information environment by constantly producing and disseminating content. Thus, digitization profoundly changes how citizens are confronted with information. An AI-assisted targeting of individuals with abundant contradictory information of unclear origin can produce fundamental doubts about what is true, what can be trusted, and whether (objective) facts even exist.

Psychologically, constant exposure to contradictory information creates “cognitive dissonance”Footnote27 – a state where humans constantly experience cognitively (and often also emotionally) stressful contradictions. There are different possible reactions to this state: (1) Citizens succumb to ILH, i.e. they repeatedly experience an inability to access harmonious, non-contradictory information, which drives them to believe that all information are contested. To these citizens, truth appears not to be knowable or existent, which results in informational agnosticism. To resolve this dissonance, agnostics take the “exit option” and refrain from forming and expressing any opinions, or even from staying informed, which can result in apathy and ignorance.

Citizens can (2) attempt to harmonize dissonance by selectively exposing themselves to one version of discourse. Influenced by traffic-maximising machine-learning algorithms that filter available information based on user preferences, however, this group might fall prey to belief in misinformation and retreat into “echo chambers”: “Regardless of how obscure the information we are consuming, as long as it supports pre-existing ideas and does not challenge our beliefs, we are prone to accept it”.Footnote28 Lastly, individuals might (3) bear the higher transaction costs of verifying information to resolve the dissonance; this constitutes a third, residual category of “the resilient” which is, however, explicitly not the focus of this article.

Why informational agnostics and misbelievers endanger democracy

Deduced from our theoretical framework, we identify two groups whose sentiments and behaviour threaten democracy: (1) the informationally agnostic and (2) misbelievers. These psychological and attitudinal consequences of digitized information environments threaten democracy before democratic decay becomes visible.

As ILH has been documented to result in apathy,Footnote29 ignorance about political matters can be expected to facilitate de-politicization, turning citizens into informational agnostics: When confronted with overwhelming amounts of contradictory narratives, citizens who renounce from consuming (political) information altogether not only become agnostic on an attitudinal level but also display apathy as a form of political behaviour. While Bond and Messing lack the causal step of ILH in between that we have introduced, they have, like Nagel, “consistently found that exposure to disagreement [on one’s social network] depresses engagement and [political] participation”.Footnote30

Crucially, de-politicization and political apathy are one of four characteristics that Linz uses to define authoritarianism as a non-democratic regime.Footnote31 Some research has also found that they contribute to democratic decay.Footnote32 In fact, democratic theory highlights the centrality of citizens’ participation in the deliberation process to generate input legitimacy for a healthy democratic system,Footnote33 and informed decision-making as an integral element of democratic citizenship.Footnote34 Healthy democracies depend on citizens’ participation;Footnote35 even more so amid a global democratic decay in which safeguarding democratic norms and practices as is paramount.Footnote36

Consequently, informational agnostics as non-participants thereby not only undermine the potential of input legitimacy generation. They are also unlikely to defend democracy or mobilize against proponents of democracy-threatening narratives or actions, as they have concluded that they cannot know what is right. Unlike “misbelievers”, agnostics are not part of the polarized but have withdrawn from politics; they feel that neither what they do matters, nor can they change anything. While they might remain engaged with their personal and family lives, they share little interest in public and political affairs. Hence, informational agnostics tend no longer to have an opinion regarding the desirability of democracy. This decrease in diffuse public support for the democratic political system can endanger the system’s sustainability.Footnote37 While agnostics may return to become part of the informed citizenry in the mid- to long-run, digital technologies make it more likely that agnostics turn into misbelievers since digital media has made it more difficult to distinguish between inaccurate and accurate information.Footnote38

Citizens overwhelmed by the abundance of contradictory information might also embrace misinformation as their new truth. They resolve the stress of cognitive dissonance by embracing information that affirms preconceived worldviews and ignoring contradicting accounts – even if that entails embracing lies and ignoring facts.

While informational agnostics constitute a more silent threat to democracy, misbelievers pose a more direct one in several ways: While access to alternative sources of information is one institutional minimum for democratic rule,Footnote39 selective exposure to misinformation and counterfactual narratives subverts the reasoning behind democratic participation. Misbelievers are, therefore, likely to vote for anti-democratic parties and candidates based on inaccurate information. While their political participation might be procedurally democratic (e.g. voting), it defies the spirit of democratic participation that envisions participation based on accurate information regarding political choices, and it can produce an impetus for anti-democratic forces that ultimately aim to dismantle democratic institutions.

Second, misbelievers can develop a deep suspicion or even aggression towards dissonant information and its proponents whome they percieve as confounders who aggravate dissonance. This suspicion and aggression can result in misbelievers denying their political opponents’ legitimacy as fellow citizens, and in extreme cases, in their stylization as enemies of the state who had best be jailed or killed. Misbelievers thus harbour attitudes that can translate into anti-democratic insurgencies.Footnote40 This is aggravated by anti-democratic actors that tactically gear misinformation towards undermining democratic institutions and manipulate citizens to mistake democracy for dictatorship. Evidence from cases like Thailand, Germany, and the US show that citizens can be mobilized against democracy if they mis-perceive it be dictatorial, fraudulent, unresponsive, or corrupt; they ironically seek to “save” the “real” democracy by tryingto overthrow an elected democratic government.Footnote41 While anti-democratic attitudes need not per se lead to anti-democratic actions, scholars highlight the importance of pro-democratic attitudes for the functioning of democracies.Footnote42 If pro-democratic attitudes are important for democracy to flourish, then digital technologies’ role in the spread of anti-democratic attitudes has direct consequences for democracy.

Third, confirmation bias induced by online selective exposure jeopardizes social cohesion and exacerbates polarization.Footnote43 Additionally, through their algorithms, social media platforms (e.g. Youtube, Facebook, and Twitter) might also facilitate radicalization.Footnote44 Radical anti-democrats aggravate these radicalization processes by using mainstream social media to funnel their targets towards even less regulated websites and “alternative” social media platforms (e.g. BitChute, Gab, Minds, Parler or Telegram) to generate funds and followers and to circumvent public scrutiny.Footnote45 Ex-president Trump’s Truth Social, when released in 2022, immediately topped the US social media downloads in Google’s Playstore and Apple’s Appstore.Footnote46

Even seemingly apolitical misinformation profoundly affects the overall information environment of citizens. For instance, nearly half of Americans believe that dinosaurs still exist.Footnote47 Such misinformation contributes to what scholars have called the “post-truth era” where people believe in starkly different accounts of reality.Footnote48 This deepens epistemic divides that extend far beyond the political sphere while reinforcing existing political divides about societal challenges, the best solutions, and whether to trust scientific accounts. Thus, seemingly apolitical questions are politically relevant in processes preceding democratic decay,Footnote49 especially since misinformation continues to influence how people think even after they have been corrected.Footnote50

In divided societies, crises of democracy are more likely to emerge,Footnote51 and if polarization looms large, democracies are in danger.Footnote52 Scenarios like “gridlock and careening” or “democratic erosion or collapse” are then enabled.Footnote53 This is not only because new cleavages underlying polarization emergeFootnote54, which pushes the democratic party system toward the brink of “nonworkability”,Footnote55 but also because citizens’ orders of preferences transform as societal trust declines. Here, electoral choices come in again: Beyond making poor choices due to misinformation, high polarization prompts voters to “trade democratic principles for partisan interests”.Footnote56 Thus, when polarization and misinformation collectively induce citizens to perceive that the social fabric has broken down, they are more likely to support authoritarian leaders.Footnote57

We have now proposed a complete causal chain that links the effects of digital technologies to political attitudes and their associated behaviour, as well as their broader impacts to democratic decay, respectively; visualizes this causal chain. With the help of anecdotal evidence from two recent examples of anti-democratic protests that challenged two established democracies, we probe the plausibility of our theorized mechanisms.

Our cases: US and Germany

Our theoretical sketch of these pathways is likely to apply in the context of a transformed informational environment at this level of abstraction, bearing in mind cross-country variations in specific structural and sub-structural conditions. Comparing the US and Germany is an important analytical exercise for several reasons. While both are established, wealthy, and representative federal democracies that have a highly educated citizenry that enjoys unfettered access to information, they are, within the universe of liberal democracies, different cases in terms of institutional arrangements, regulation of freedom of speech, digital platform regulations, and media gatekeeping mechanisms.

First, as far as democratic subtypes are concerned, majoritarian systems like those of the US are likely to foster the dominance of identity-based politics. In contrast, proportional representation systems that exist in Germany lead to more inclusive coalitions that temper partisan hostility.Footnote58 Second, while the American doctrine of free speech places immense faith in the ability of the individual to discern the truth where he sees it, the German approach necessitates interventions in fostering a tradition of civility and a polity of responsible citizens.Footnote59 Third, Germany’s digital regulatory framework compels social media companies to remove hate speech and other illegal content whereas American laws provide them with thorough protection from third-party liability, as well as a general allowance for platforms to take down content voluntarily.Footnote60 Fifth, Germany’s public media enjoys significantly more public funding than the US’ highly commerce-driven media landscape, which plays a key role in containing the spread of bias that aggravates ideological extremity and partisan conflict.Footnote61 Finally, and arguably due to the differences, both countries witnessed different degrees of democratic decay.Footnote62

Despite these critical differences, very similar mechanisms challenge democracy in both cases. Specifically, AI-assisted digital communication technologies fuelled doubtful attitudes and anti-democratic actions in both countries. In the US, protestors stormed Capitol Hill on January 6, 2021, over misinformation surrounding voter fraud. Similarly, Germans who opposed the government’s COVID policies stormed the Reichstag on August 29, 2020. While German anti-COVID protests were more diverse than Capitol riot protests, their common denominator is a growing portion of misinformed citizens who renounce “diffuse support” for democracy.Footnote63 In addition, both cases show signs of digitally aggravated apathy. In the US, one-third of eligible voters did not vote in the 2020 presidential elections.Footnote64 In Germany, noncompliance with the government’s public health measures was linked to people who gave up on consuming information about COVID.Footnote65

A plausibility probe helps establish whether our framework is valid based on the extent to which it accounts for apparent empirical phenomena.Footnote66 Using a plausibility probe, we seek to provide an initial, non-exhaustive empirical illustration of how features inherent to digitization aggravate selective exposure and ILH, which, in turn, influence beliefs and behaviour dangerous to democracies. Our probe, therefore, seeks to provide an initial, non-exhaustive empirical illustration of the socio-psychological impacts that digital technologies have at the attitudinal and behavioural level before decay or breakdown becomes visible at the political regime level. The outcomes at the focus of our analysis are anti-democratic insurgencies, negative attitudes towards democratic institutions, and political apathy.Footnote67

Concretely, we employ four qualitative indicators drawn from our framework to help guide our probe: (1) tailored dissemination of contradictory information to citizens with similar beliefs via recommendation algorithms; (2) the presence of self-organized users and groups on social media platforms who shape algorithmic processes by actively producing and disseminating misinformation; (3) the presence of citizens who selectively expose themselves to tailored online misinformation to gain subjective certainty. Their consumption of contradictory information are expressed via doubts towards official information in favour of dubious non-official sources of information that form a basis for subsequent engagements in anti-democratic actions (e.g. refusal to comply with decision-making processes and norms governing representative democracies and issuing threats of armed violence against elected officials and state representatives); and (4) the presence of citizens who express a sense of helplessness in navigating the abundance of contradictory information. In contrast to the misbelievers, helpless citizens disengage altogether from forming concretely defined beliefs.

From “Stop the Steal” to the steps of the Capitol

On January 6, 2021, a mob of 2,000-2,500 supporters of former US president Donald Trump stormed the Capitol building in Washington, DC as they sought to overturn President-elect Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 presidential elections. The rioters comprised of hyper-partisan pro-Trump activists, QAnon conspiracy theorists, the neo-fascist Proud Boys, unlawful militias (e.g. Oath Keepers), and ideological travellers of the far-right.Footnote68 This blatant physical violation of American democracy was not a spontaneous reaction to Trump’s call but an incremental process in which its origin bear traces to digital technologies that underpin the transformed informational environment. Specifically, the combination of an abundance of contradictory information about official election results, difficulties in identifying truthful accounts, and algorithmic targeting paved the way for a militant offline mass of misbelievers.

Facebook and the digital technologies that power its platform were central to the spread of misinformation. In 2016, the company’s internal studies revealed that its algorithms and prioritization of user engagement exacerbated political polarization, such as by recommending a user to join QAnon - a baseless online fringe-turned-mainstream conspiracy theory that proclaimed Trump’s divine role to save the world from an evil cabal of paedophiles.Footnote69 Despite warnings before the elections,Footnote70 Facebook's algorithms continued to recommend QAnon pages to old and new users.Footnote71 While Facebook eventually paused its recommendations engine, it started to lift some of these control measures following the elections.Footnote72

These algorithmic processes amplified what became the “Stop the Steal” narrative that consisted of three underlying arguments: (1) the expansion of mailed ballots created an opportunity for Democrats to engage in massive voter fraud; (2) Trump won the election and; (3) Trump was within his right to challenge the result and not concede, and even further, Republican legislatures and governors in states where Biden won should use their power to appoint pro-Trump electors.Footnote73 When Biden’s victory became clear on November 7, the narrative, coupled with the Trumpists’ Big Lie tale (a term that is borrowed directly from Hitler’s 1925 book Mein Kampf), grew in coordination with Trump’s failed legal efforts to “stop the count” of legitimate votes in various states.Footnote74

The escalations among various far-right movements that culminated in the Capitol riots were linked to these algorithmically-driven filter bubbles that sustained a groundswell of selective online engagements with the Stop the Steal narrative. These processes did not mitigate polarization but hardened the viewpoints of many Americans who had already embarked on a path to radicalization. Footnote75 One Facebook group started by Tea Party activists Amy and Kylie Kremer, which peddled unsubstantiated accusations that the Democrats made false copies of ballots and tricked Arizona Trump supporters into using sharpies to invalidate their votes, attracted more than 360,000 members just a day after the election.Footnote76 Initially, Facebook took “limited or no action” against election delegitimization movements and only began removing them once they already gained traction.Footnote77

Ultimately, these online dynamics facilitated anti-democratic protests notwithstanding the protesters’ professed intentions to “save” US democracy from a perceived corrupt political establishment. Even before January 6, smaller but provocative Stop the Steal rallies had already mushroomed around the country, mostly in states with contested election results.Footnote78 Moreover, Jacob Chansley (the “QAnon Shaman” who became the face of the riot) is an example of how digitized informational environments can exacerbate selective exposure tendencies that result in anti-democratic behaviour. On the day of the riot, he remarked,

I realized that doing my own research brought me more information than listening to the news ever could. Once I stopped allowing the news to make up my mind or my narrative for me, I grew exponentially … I was able to take the information that I was absorbing and apply it to my activist routine.Footnote79

Other misbelievers who developed anti-democratic attitudes but did not physically partake in the Capitol violence can also exacerbate processes that make democratic decay visible. While many Americans rejected the claims and propositions related to Stop the Steal, Republican voters supported all elements of the narrative in significant numbers.Footnote80 Furthermore, election misinformation can confuse citizens and place them at the crossroads of either becoming misbelievers or informationally agnostic citizens. Following the elections, 10% of Americans were unsure if Trump should publicly acknowledge Biden as the legitimate president.Footnote81

Beyond selective exposure, the effects of digital technologies can also influence ILH, which increases the risk of political apathy that quietly harm democracies: about 68% of US adults said the 2020 elections were a significant source of stress in their lives.Footnote82 Furthermore, there were indications of apathy as false claims of a stolen election became widespread. Lending initial support to our theorization that informationally agnostics retreat from information consumption to reduce costs associated with information verification, a Pew Research Center poll indicated that one-third of US respondents said that they heard “a little” about January 6.Footnote83

From COVID scepticism to the steps of the Reichstag

The COVID-19 pandemic is the first global health crisis that has played out in the digital era where online falsehoods can quickly go viral. The proportion of Germans who saw COVID misinformation several times a day rose from 9% in June 2020 to 17% in February 2021.Footnote84 While digital technologies and social media help keep people safe and informed, they also enable and amplify an “infodemic” where an abundance of contradictory information causes citizens to doubt their governments’ public health measures.Footnote85 The mainstreaming of major pandemic-related conspiracy theories that originated from fringes of the internet were, in fact, linked to digital and AI-assisted technologies that power social media platforms.Footnote86

One of the major COVID conspiracy narratives that managed to penetrate the European online sphere with the help of these technologies is “ID2020”. It accused Microsoft and Bill Gates of employing the pandemic as a pretext for implanting microchips to control citizens.Footnote87 Given that algorithms promote divisive content, high engagements by conspiracy users shaped these algorithms in ways that steered vulnerable users towards this narrative in the aftermath of the outbreak in late 2019.Footnote88 By May 2020, ID2020 became one of the key terms on Twitter.Footnote89 Though traces of ID2020 first emerged at anti-COVID protests in the US, they also trickled their way into the German context. Between March and July 2020, around a quarter of German adults believed that Gates had more power than the government and had bought the WHO.Footnote90 In May, a famous vegan chef claimed that the federal government tried to forcibly plant mind-control chips into its citizens at the behest of Gates.Footnote91 One doctor also accused Gates of striving for ““pharmacological” world domination”.Footnote92

As ID2020 made its round on Twitter, the core tenets of QAnon evolved into an umbrella conspiracy that started to embrace anti-COVID narratives. Here, algorithmic targeting continued to amplify narratives that appealed to anti-vaccination and anti-lockdown users.Footnote93 On Youtube, recommendation algorithms contributed to a “conspiracy boom” that included QAnon.Footnote94 These algorithmic processes facilitated the “trans-nationalization” of QAnon into the German online sphere, which attracts the second largest number of followers after the US despite stronger media gatekeeping mechanisms.Footnote95 A number of German users were able to adapt such alt-right themes and narratives to their context and, aided by recommendation algorithms, pushed the conspiracy theory downstream. After conspiracy ideologue Oliver Janich created the first major German-language video on QAnon in November 2017, the video reached 90,000 views.Footnote96 Though Youtube modified its algorithms in early 2019,Footnote97 another German-language QAnon YouTube channel, Qlobal-Change, amassed over 17 million views by September 2020.Footnote98

These effects consequentially shaped anti-democratic attitudes and, in extreme cases, mobilized anti-democratic actions against the German government. The protests that transpired on August 29 in front of the Reichstag were motley crew of Querdenker (“lateral thinkers” who are sceptical and oppose the government’s COVID measures), anti-vaxxers, Q-Anon conspiracy theorists, far-right extremists, and ordinary citizens.Footnote99 Around 300 of these protesters stormed the building before the police eventually dispersed them. Though the violators were a subset of the 30,000 people who attended the mostly non-violent demonstration that day, digitally induced cognitive dissonance was a key driver behind their anti-democratic behaviour.Footnote100 The presence of QAnon signs and a portrait of Trump during the rally, as well as images of protesters chanting and promoting anti-Gates slogans such as “Don’t give Gates a chance”,Footnote101 suggest that selective exposure to online misinformation about COVID, which was reinforced by algorithmic targeting of QAnon and ID2020 content on social media, induced a misguided belief amongst protesters and sceptics that their resistance was against a supposed “COVID dictatorship”.Footnote102

Although the storming of the Reichstag represented the most visible attack on German democracy and foreshadowed what was to come for the US several months later, digitally-induced cognitive dissonance also played a quieter role in shaping anti-democratic attitudes prior to the incident. Shortly after the first nation-wide lockdown in March 2020, over 25% of Germans believed there was something else behind the pandemic than what was officially announced.Footnote103 Moreover, one study highlighted a positive correlation between Germans who use social media to inform themselves and the rise in pandemic-related conspiratorial beliefs, which suggests the potential of algorithmic targeting to reinforce selective exposure to misinformation.Footnote104 Ten percent of Germans reportedly started to believe in a global conspiracy, mostly in connection to Gates.Footnote105 Separate from anti-democratic attitudes and actions, signs of apathy associated with ILH also surfaced. Many Germans found distinguishing between news and fake news on the virus difficult.Footnote106 As conspiratorial narratives continued to spread, a YouGov poll in September 2020 provided further empirical evidence for our probe: 11% of the respondents did not know what to think about them, suggesting a degree of detachment that is in line with our theorization that because they cannot know what is right, informationally agnostic citizens withdraw from information consumption to minimize cognitive dissonance.Footnote107

Conclusion

Global democracy indices such as Freedom House, Polity, or the Bertelsmann Transformation Index tell us that democracy is globally in retreat, but the jury remains out on at least two important questions: The first is about the concrete causal mechanisms that underlie democratic decay as a domestic process. The second is to understand the reasons behind variations in the extent and nature of decay in different contexts, i.e.: Why do some democracies crumble more quickly and substantially than others?

This article contributes to the first debate. We argue that three features inherent to digitization alter the information environment of citizens; we illustrate how this contributes to spreading attitudes and behaviour that put stress on, and thus constitute a threat to, democracy. While our case studies empirically illustrate that these characteristics of digitization leave citizens vulnerable to misinformation and apathy, we have also drawn on established knowledge in democratic theory to show how misbelief and apathy threaten the foundations of democracy. We thus provide a novel theoretical approach of how global digitization, widespread misinformation, and challenges to democratic rule are interconnected.

These causes we hypothesize and illustrate empirically usually precede the adverse effects on democracy as measured by existing democracy indices and are hardly captured by the latter. This means: The state of democracy as numerically measured by commonly used indicator systems might seem identical in two given cases; yet, immanent threats of the sort discussed previously may have built up in one case but not in another with identical values on “democracy” – because they are not made visible by existing indices. Thus, equal levels of stress or threats to democracy need not automatically result in similar levels of democratic decay. A diverse range of variables – apart from the ones discussed previously – can be assumed to contribute to the robustness or fragility of democratic regimes when faced with significant stress.Footnote108 Here again, the cases of the US and Germany might provide a helpful comparison to uncover the variables resulting in varying degrees of decay.

Yet, the paramount issue for scholars, but also for democratic policymakers, would be to pay attention to stress on, and threats to, democracy before existing indices can make them visible as a manifest decay or breakdown of democratic institutions and/or procedures. We call for the development of more fine-grained instruments to be able to better assess and potentially quantify such latent stress (and for democratic decision-makers to devise policies to safeguard democracy). This emergent research agenda would also benefit from two additional endeavours. First, because informationally agnostic citizens are far less visible than misbelievers, more research is required on the formers’ size, motivations, and on possible ways to turn them back into informed citizens despite the challenging information environment. Second, the analytical framework we proposed should be subjected to more systematic testing: While our plausibility probe does provide some preliminary empirical illustrations that seem to support our claims, it must not be mistaken for a rigorous effort at falsification.

Beyond complementing ongoing debates on digital technologies and democratic decay by providing much-needed theory-building and proposing concrete causal mechanisms at play, this contribution thus also offers a potentially fruitful outlook for policy-makers and academics to further discuss strategies and policies to promote societal resilience to anti-democratic trends in the digital age – politically by, e.g. enhancing information literacy or regulatory oversight over algorithmic targeting; academically by further testing our proposed mechanisms and by operationalizing the link between digitization and anti-democratic attitudes and behaviour through the development of more fine-grained tools for measurement than the ones currently available.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jelena Cupac, Hendrik Schopmans, and Irem Tuncer-Ebetürk from the Berlin Social Science Center for their helpful comments. The authors would also like to thank Žilvinas Švedkauskas, research assistant Victoria Wang, and all participants of the Chair's research colloquium.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmed Maati

Ahmed Maati is a postdoctoral researcher at the Technical University of Munich’s Hochschule für Politik. He has completed his Ph.D. in political science at the Eberhard-Karls University of Tuebingen. His research focuses on digital authoritarianism, governance of new Technologies, AI and sustainable development goals, the regulation of digital technologies in democracies, comparative authoritarianism, and theories of the state.

Mirjam Edel

Mirjam Edel is a Political Science lecturer at the University of Tuebingen, Germany. Her PhD and publications focus on state repression in the Middle East and North Africa. Other main areas of expertise are authoritarian regimes and state-society relations. She recently works on how digitalization affects political systems.

Koray Saglam

Koray Saglam is a research associate, junior lecturer, and Ph.D. candidate with the Research Group for Middle East and Comparative Politics at the Institute of Political Science at the Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen. As part of the Trajectories of Change program, he is also a Bucerius Ph.D. Fellow of the ZEIT-Stiftung Ebelin und Gerd Bucerius. He studied Comparative Middle East Politics and Society (M.A.), and International Economics (B.Sc.) at Tübingen University, the California State University Chico, as well as the American University in Cairo.

Oliver Schlumberger

Oliver Schlumberger is a Professor of Comparative Politics at Tübingen and specializes in comparative democratization, autocratisation and authoritarianism. He has published numerous books and articles in such journals as Democratization, Government & Opposition, the International Political Science Review, New Political Economy or the Review of International Political Economy. His latest publications include “Authoritarianism and Authoritarianization” in the Handbook of Political Science (2020 Sage, with Tasha Schedler) and The Puzzle of Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa (2021, DIE).

Chonlawit Sirikupt

Chonlawit Sirikupt is a PhD candidate in political science at the Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen. His research focuses on use of the Internet and digital information technology and their implications for democratic and authoritarian rule.

Notes

1 Dahl, Polyarchy, 3.

2 Delli Carpini and Keeter, “The Internet and an Informed Citizenry,” 131.

3 Tucker et al., “Social Media, Political Polarization, and Political Disinformation.”

4 A plethora of terms has been invented to refer to this phenomenon. While aware of these debates, we do not seek to settle them here; rather, we agree with Gerschewski that all these terms are “broadly defined as a loss in democratic quality,” all the while acknowledging that measurement of such decay is, again, debated (cf., i.a., Diamond and Morlino (eds), Assessing the quality of democracy for an overview of discussions on this topic). In the following, we refer to the said phenomenon as democratic decay.

5 Stavrositu, “Selective Exposure”; Stroud, “Media Use and Political Predispositions.” In short, “selective exposure” refers to individuals choosing information sources consonant with their worldview.

6 Nisbet and Kamenchuk, “Russian News Media, Digital Media … ” In contrast to the Russian case they study, however, reference to ILH in democracies refers to citizens’ unavoidable exposure to contradictory information.

7 We do not seek to explain regime-level outcomes that may (and empirically do) differ quite dramatically between cases such as Russia, Hungary or Turkey (where democracy was abolished altogether during the past two decades), or Poland, the US or Brazil (where a tangible erosion of democratic quality is undisputed despite the fact that these cases may still qualify as democracies), and, third, cases such as France, Germany, or Sweden (where we identify “stress factors” such as significant parts of the populace falling prey to misinformation or political apathy even though a decline in the quality of democracy cannot (yet) be measured). By contrast, we seek to establish a more comprehensive causal argument which, because of its comprehensiveness, will allow us to identify dangers and threats to democracy way before current measurement systems of democratic quality would detect them.

8 Gowen, “As Mob Lynchings Fueled by WhatsApp Messages Sweep India … ”;

9 Wardle and Derakshan, “Information Disorder,” 10; Wenzel, “To Verify or to Disengage,” 1987-1988.

10 cf. Fallis, “What is Disinformation.” While misinformation and disinformation both refer to false or misleading information, disinformation is characterized as “nonaccidentally misleading information” intended to deceive people. Misinformed citizens can further share such information without having the intent to deceive.

11 Švedkauskas, Sirikupt, and Salzer, “Russia’s Disinformation Campaigns Are Targeting African Americans”; Allcot and Genztkow, “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election”; Tucker et al. “Social Media, Political Polarization … ”; Benkler, Faris, and Roberts, Network Propaganda, 341–9.

12 McKay and Tenove, “Disinformation as a Threat to Deliberative Democracy.”

13 Ibid.

14 Pond, Complexity, Digital Media and Post Truth Politics.

15 We do not intend to provide a universal definition of, or engage with philosophical debates about, “truth” and “falsehood.” This would merit discussions that go beyond our scope. Our goal is rather to theorize and show the link between digitization, misinformation, and democratic decay. To illustrate this link, we examine obvious cases of misinformation and falsehoods.

16 Feldstein, The Rise of Digital Repression, 3–4.

17 Ibid., 4.

18 cf. Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

19 Vaccari and Chadwick, “Deepfakes and Disinformation”; European Commission, The Impact of Digitization on Daily Lives, 54.

20 Dean, “The Facebook Files”; Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic, “Exposure to Ideologically Diverse News and Opinion on Facebook”; Arguedass, “Echo Chambers, Filter Bubbles, and Polarisation.”

21 Swire, Ecker, and Lewandowsky, “The Role of Familiarity in Correcting Inaccurate Information,” 1948–1949.

22 cf. Saglam, “The Digital Blender.”

23 Traffic includes frequency, interaction intensity, and a number of interactions with online content. More traffic means more data to collect and sell, more precise targeting, greater ad-revenues, and a greater likelihood that users will subscribe or donate; Kenney and Zysman, “The Rise of the Platform Economy”; Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

24 Dean, “The Facebook Files.”

25 Vosoughi, Roy, and Aral, “The Spread of True and False News Online,” 1147.

26 cf. Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Non-social media platforms like Spotify or Netflix use similar techniques to increase user traffic, commodify data, and share it with third parties.

27 Festinger, Leon. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.

28 Meyer and Böswald, Mapping the Tools, Tactics and Narratives … , 13.

29 Nagel, “Constructing Apathy.”

30 Bond and Messing, “Quantifying Social Media’s Political Space,” 75.

31 Linz, Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes, 264.

32 Berelson, Paul, and McPhee, Voting, 314; Huntington, “The United States,” 114.

33 Dahl, Polyarchy.

34 Dahl, Dilemmas of Pluralist Democracy, 10-11; Dahl, Democracy and its Critics, 108-114.

35 Neubauer, “Some Conditions of Democracy,” 1002.

36 cf. Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die.

37 Easton, “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support”; for a recent empirical confirmation of the argument see Claassen, “Does Public Support Help Democracy Survive?”.

38 Nisbet and Kamenchuk, “Russian News Media, Digital Media … ,” 576.

39 Dahl, Dilemmas of Pluralist Democracy, 10–11; Dahl, Democracy and its Critics, 108–14.

40 c.f. Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die, 23.

41 Sinpeng, Opposing Democracy in the Digital Age, 165-166; Volk, “Political Performances of Control During COVID-19,” 13; DFR Lab, “#StopTheSteal”; Leuker et al., “Misinformation in Germany During the COVID-19 Pandemic.”

42 Teorell and Hadenius, “Democracy without Democratic Values”; cf. Welzel and Inglehart, “Political Culture, Mass Beliefs … ,” 126.

43 Lawrence, Sides, and Farrell, “Self-Segregation or Deliberation?”

44 cf. Camargo, “YouTube’s Algorithms Might Radicalise People.”

45 Andrews and Pym, “The Websites Sustaining Britain’s Far-Right Influencers.”

46 Palmer, “Fact Check”

47 SWNS Staff, “Nearly Half of Americans Convinced … ”

48 Suiter, “Post-Truth Politics.”

49 Lipset, Political Man, 83; Mouffe, “Deliberative Democracy or Agnostic Pluralism.”

50 Ecker et al., “The Psychological Drivers of Misinformation Beliefs … ” The impact this has on contentious political issues can hardly be overestimated (e.g., whether the 2020 elections were “stolen” is a claim that more than half of Republican Party members still believe two years later).

51 Linz, The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes, 28.

52 Dahl, Polyarchy, 105; Sartori, Parties and Party Systems, 132–44.

53 McCoy, Rahman, and Somer, “Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy.”

54 Ibid.

55 Sartori, Parties and Party Systems, 144.

56 Svolik, “Polarization versus Democracy.”

57 Crimston, Selvanathan, and Jetten, “Moral Polarization Predicts Support … ”

58 Lijphart, Patterns of Democracy, 275.

59 Kommers, “The Jurisprudence of Free Speech … ,” 685.

60 Scheurman, “Comparing Social Media Content in the US and the EU,” 418.

61 Benkler, Faris, and Roberts, “Network Propaganda,” 22.

62 International IDEA. “The Global State of Democracy Indices.”

63 Easton, “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support,” 444–7.

64 Chamie, “Who’s Not Voting in America?”

65 Siebenhaar, Köther, and Alpers, “Dealing With the COVID-19 Infodemic,” 4–6.

66 A plausibility probe is an intermediary step between hypothesis generation and hypothesis testing that allows scholars to explore the suitability of a particular case(s) as a vehicle for theory development; Levy, “Case Studies,” 3.

67 We used primary and secondary sources in English and German to support our probe. These include archives of digital media and statements by protesters, news reports, and scholarly works. We also used opinion surveys about citizens’ perceptions of the 2020 US presidential elections and belief in COVID-related conspiracy theories in Germany.

68 DFR Lab, “#StopTheSteal.”

69 Zadrozny, “‘Carol’s Journey.’”

70 Martin, Recommending an Insurrection, 230.

71 Frenkel, “Facebook Removes 790 QAnon Groups … ”

72 Timberg, Dwoskin, and Albergotti, “Inside Facebook, Jan. 6 Violence Fueled Anger … ”

73 Drutman, “Theft Perception.”

74 DFR Lab, “#StopTheSteal.”

75 Ibid.

76 Tolan, “The Operative”; Mak, “How ‘Stop the Steal’ Exploded on Facebook and Twitter.”

77 Mac and Frenkel, “Internal Alarm, Public Shrugs”

78 Ibid.

79 Channel 4 News, “Meet the ‘QAnon Shaman’ … ”

80 Drutman, “Theft Perception.”

81 Griffin and Quasem, “Crisis of Confidence,” 6.

82 Safai, “Managing the Psychological Effects of the 2020 Election.”

83 Gramlich, “A Look Back at Americans’ Reactions … ”

84 Leuker et al., “Misinformation in Germany During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” 11.

85 World Health Organization, “Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic.”

86 Dwoskin, “Misinformation About the Coronavirus … ”

87 Thomas and Zhang, “ID2020, Bill Gates and the Mark of the Beast,” 2.

88 Ibid., 6.

89 Ibid., 12.

90 Friedrich Naumann Stiftung, “Globale Studie.”

91 Kirschbaum, “Coronavirus Conspiracy Theories About Mind Control Chips … ”

92 Das Versteckspiel, “Feindbild Bill Gates/‘Gib Gates Keine Chance.’”

93 Wong, “Down the Rabbit Hole.”

94 Faddoul, Chaslot, and Farid. “A Longitudinal Analysis of YouTube’s Promotion of Conspiracy Videos.”

95 Barker, “Germany Is Losing the Fight Against QAnon.”

96 Holnburger, Tort, and Lamberty, “Q VADIS? The Spread of QAnon in the German-Speaking World,” 15.

97 Dwoskin, “YouTube is Changing its Algorithms to Stop Recommending Conspiracies.”

98 Barker, “Germany Is Losing the Fight Against QAnon.”

99 Brady, “Thousands Turn out in Berlin to Protest Coronavirus Measures.”

100 Ibid.

101 Euronews, “‘Sturm auf Reichstag’.”

102 Brady, “Thousands Turn out in Berlin to Protest Coronavirus Measures.”; Forsa Institute, “Befragung von Nicht Geimpften Personen … ,” 4.

103 Maas, Was Hat Bill Gates mit Corona zu Tun?, 27–8.

104 Ibid., 29.

105 Ibid., 28.

106 Friedrich Naumann Stiftung, “Globale Studie.”

107 Suhr, “Das Halten die Deutschen von Verschwörungsmythen. ”

108 Some of which may likely be found in the literature on democratic consolidation such as in, e.g., Merkel, “Embedded and Defective Democracies.”

Bibliography

- Allcott, Hunt, and Matthew Gentzkow. “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31, no. 2 (2017): 211–236. doi:10.1257/jep.31.2.211.

- Andrews, Frank, and Ambrose Pym. “The Websites Sustaining Britain’s Far-Right Influencers”. Bellingcat, February 24, 2021. https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2021/02/24/the-websites-sustaining-britains-far-right-influencers/.

- Bakshy, Eytan, Solomon Messing, and Lada A. Adamic. “Exposure to Ideologically Diverse News and Opinion on Facebook.” Science 348, no. 6239 (2015): 1130–1132. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1160.

- Barker, Tyson. “Germany is Losing the Fight Against QAnon.” Foreign Policy, September 2, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/02/germany-is-losing-the-fight-against-qanon/.

- Benkler, Yochai, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Berelson, Bernard R., Paul F. Lazarsfeld, and William N. McPhee. Voting: A Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Campaign. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954.

- Bond, Robert, and Solomon Messing. “Quantifying Social Media’s Political Space: Estimating Ideology from Publicly Revealed Preferences on Facebook.” American Political Science Review 109, no. 1 (2015): 62–78. doi:10.1017/S0003055414000525.

- Brady, Kate. “Thousands Turn out in Berlin to Protest Coronavirus Measures.” Deutsche Welle, August 28, 2020. https://www.dw.com/en/thousands-turn-out-in-berlin-to-protest-coronavirus-measures/a-54756290.

- Camargo, Chico Q. “YouTube’s Algorithms Might Radicalise People – but the Real Problem is We’ve no Idea How They Work”. The Conversation, January 21, 2020. https://www.theconversation.com/youtubes-algorithms-might-radicalise-people-but-the-real-problem-is-weve-no-idea-how-they-work-129955.

- Chamie, Joseph. “Who’s Not Voting in America?” The Hill, July 7, 2021. https://thehill.com/opinion/campaign/561886-whos-not-voting-in-america/.

- Channel 4 News. “Meet the ‘QAnon Shaman’ Behind the Horns at the Capitol Insurrection.” YouTube. January 21, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=trB06rINhKI&ab_channel=Channel4News.

- Claassen, Christopher. “Does Public Support Help Democracy Survive?” American Journal of Political Science 64, no. 1 (2020): 118–134. doi:10.1111/ajps.12452.

- Crimston, Charlie R., Hema Preya Selvanathan, and Jolanda Jetten. “Moral Polarization Predicts Support for Authoritarian and Progressive Strong Leaders via the Perceived Breakdown of Society.” Political Psychology 43, no. 4 (2022): 671–691. doi:10.1111/pops.12787.

- Dahl, Robert A. Democracy and its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

- Dahl, Robert A. Dilemmas of Pluralist Democracy: Autonomy vs. Control. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

- Dahl, Robert A. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971.

- Das Versteckspiel. “Feindbild Bill Gates / ‘Gib Gates Keine Chance.’” [“Enemy Image Bill Gates / ‘Give Bill Gates No Chance’”] Das Versteckspiel. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://dasversteckspiel.de/die-symbolwelt/verschwoerungsmythen/feindbild-bill-gates-gib-gates-keine-chance-343.html.

- Dean, Jason. “The Facebook Files.” Wall Street Journal, October 1, 2021. https://www.wsjplus.com/offers/facebook-files-ebook.

- Carpini, Delli, X. Michael, and Scott Keeter. “The Internet and an Informed Citizenry.” In The Civic Web, edited by David Anderson, and Michael Cornfield, 129–153. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002.

- DFR Lab. “#StopTheSteal: Timeline of Social Media and Extremist Activities Leading to 1/6 Insurrection.” Just Security. February 10, 2021. https://www.justsecurity.org/74622/stopthesteal-timeline-of-social-media-and-extremist-activities-leading-to-1-6-insurrection/.

- Diamond, Larry, and Leonardo Morlino. In Assessing the Quality of Democracy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005.

- Drutman, Lee. “Theft Perception.” Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, June 3, 2021. https://www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/theft-perception.

- Dwoskin, Elizabeth. “Misinformation About the Coronavirus Is Thwarting Facebook’s Best Efforts to Catch It.” The Washington Post, August 19, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/08/19/facebook-misinformation-coronavirus-avaaz/.

- Dwoskin, Elizabeth. “YouTube Is Changing Its Algorithms to Stop Recommending Conspiracies.” The Washington Post, January 19, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/01/25/youtube-is-changing-its-algorithms-stop-recommending-conspiracies/.

- Easton, David. “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5, no. 4 (1975): 435–457. doi:10.1017/s0007123400008309.

- Ecker, Ullrich K. H., Stephan Lewandowsky, John Cook, Philipp Schmid, Lisa K. Fazio, Nadia Brashier, Panayiota Kendeou, Emily K. Vraga, and Michelle A. Amazeen. “The Psychological Drivers of Misinformation Belief and its Resistance to Correction.” Nature Reviews Psychology 1, no. 1 (2022): 13–29. doi:10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y.

- Euronews. “‘Sturm auf Reichstag’: Nazi-Flaggen und QAnon-Anhänger in Berlin. [Attack on the Reichstag: Nazi Flags and QAnon Supporters in Berlin]”. Euronews, August 30, 2020. https://de.euronews.com/2020/08/30/nazi-flaggen-und-qanon-anhanger-bei-corona-protesten-in-berlin.

- European Commission. “Attitudes towards the Impact of Digitalisation on Daily Lives”. Brussels: European Union, March 2020. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2228.

- Faddoul, Mark, Guillaume Chaslot, and Hany Farid. “A Longitudinal Analysis of YouTube’s Promotion of Conspiracy Videos.” March 6, 2020. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2003.03318.pdf.

- Fallis, Don. “What is Disinformation?” Library Trends 63, no. 3 (2015): 401–426. doi:10.1353/lib.2015.0014.

- Feldstein, Steven. The Rise of Digital Repression: How Technology Is Reshaping Power, Politics, and Resistance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Festinger, Leon. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1957.

- Forsa Institute. Befragung von Nicht Geimpften Personen zu den Gründen für die Fehlende Inanspruchnahme der Corona-Schutzimpfung [Survey of Non-Vaccinated Persons About the Reasons for the Lacking Claim of the Corona-Protection Vaccination]. Berlin: Forsa Institute, 2021. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/C/Coronavirus/Befragung_Nichtgeimpfte_-_Forsa-Umfrage_Okt_21.pdf.

- Frenkel, Sheera. “Facebook Removes 790 QAnon Groups to Fight Conspiracy Theory.” The New York Times, August 19, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/19/technology/facebook-qanon-groups-takedown.html.

- Friedrich Naumann Stiftung. Globale Studie: Desinformationen Durchdringen Gesellschaften Weltweit [Global Study: Disinformation Pervades Societies All Over The World]. Berlin: Friedrich Naumann Stiftung, 2020. https://www.freiheit.org/de/globale-studie-desinformationen-durchdringen-gesellschaften-weltweit.

- Gerschewski, Johannes. “Erosion or Decay? Conceptualizing Causes and Mechanisms of Democratic Regression.” Democratization 28, no. 1 (2021): 43–62.

- Gowen, Annie. “As Mob Lynchings Fueled by WhatsApp Messages Sweep India, Authorities Struggle to Combat Fake News.” The Washington Post, June 2, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/as-mob-lynchings-fueled-by-whatsapp-sweep-india-authorities-struggle-to-combat-fake-news/2018/07/02/683a1578-7bba-11e8-ac4e-421ef7165923_story.html.

- Gramlich, John. “A Look Back at Americans’ Reactions to the Jan. 6 Riot at the USS Capitol.” Pew Research Center. January 4, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/01/04/a-look-back-at-americans-reactions-to-the-jan-6-riot-at-the-u-s-capitol/.

- Griffin, Robert, and Mayesha Quasem. “Crisis of Confidence.” Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, June 24, 2021. https://www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/crisis-of-confidence.

- Holnburger, Josef, Maheba G. Tort, and Pia Lamberty. Q VADIS? The Spread of QAnon in the German-Speaking World. Berlin: Center for Monitoring, Analysis and Strategy, 2022. https://cemas.io/en/publikationen/q-vadis-the-spread-of-qanon-in-the-german-speaking-world/CeMAS_Q_Vadis_The_Spread_of_QAnon_in_the_German-Speaking_World.pdf.

- Huntington, Samuel P. “The United States.” In The Crisis of Democracy: On the Governability of Democracies, edited by Michel Crozier, Samuel P. Huntington, and Joji Watanuki, 59–118. New York: New York University Press, 1975.

- International IDEA. “The Global State of Democracy Indices.” International IDEA. December 31, 2021. https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices/democracy-indices.

- Jenkins, Joy, and Lucas Graves. United States. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2021. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2021/united-states.

- Kenney, Martin, and John Zysman. “The Rise of the Platform Economy.” Issues in Science and Technology 32, no. 3 (2016), 61–69. https://issues.org/the-rise-of-the-platform-economy/.

- Kirschbaum, Erik. “Coronavirus Conspiracy Theories About Mind Control Chips, Bill Gates and Face Masks Fuel Lockdown Protests in Germany.” South China Morning Post, May 13, 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/world/europe/article/3084165/coronavirus-conspiracy-theories-about-mind-control-chips-bill.

- Kommers, Donald P. “The Jurisprudence of Free Speech in the United States and the Federal Republic of Germany.” Southern California Law Review 53, no. 2 (1980): 657–696.

- Lawrence, Eric, John Sides, and Henry Farrell. “Self-Segregation or Deliberation? Blog Readership, Participation, and Polarization in American Politics.” Perspectives on Politics 8, no. 1 (2010): 141–157. doi:10.1017/S1537592709992714.

- Leuker, Christina, Lukas Maximilian Eggeling, Nadine Fleischhut, John Gubernath, Ksenija Gumenik, Shahar Hechtlinger, Anastasia Kozyreva, Larissa Samaan, and Ralph Hertwig. “Misinformation in Germany During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey on Citizens’ Perceptions and Individual Differences in the Belief in False Information.” European Journal of Health Communication 3, no. 2 (2022): 13–39.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown, 2018.

- Levy, Jack. “Case Studies: Types, Designs, and Logics of Inference.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 25 (2008): 1–18.

- Lijphart, Arend. Patterns of Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Linz, Juan J. The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Crisis, Breakdown and Reequilibration. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978.

- Linz, Juan. “Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes.” In Handbook of Political Science, edited by Nelson W. Polsby, and Fred I. Greenstein, 175–328. Reading: Addison-Wesley, 1975.

- Lipset, Seymour M. Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics. Garden City: Doubleday, 1959.

- Maas, Rüdiger. Was Hat Bill Gates mit Corona zu Tun? Ein Buch über die Entstehung von Verschwörungstheorien und den Umgang mit Ihnen. [What Does Bill Gates Have to Do with Corona? A Book About the Emergence of Conspiracy Theories and Dealing with Them]. Norderstedt: Books on Demand, 2020.

- Mac, Ryan, and Sheera Frenkel. “Internal Alarm, Public Shrugs: Facebook’s Employees Dissect Its Election Role.” The New York Times, October 22, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/22/technology/facebook-election-misinformation.html.

- Mak, Aaron. “How ‘Stop the Steal’ Exploded on Facebook and Twitter.” Slate, November 5, 2020. https://slate.com/technology/2020/11/how-stop-the-steal-exploded-on-facebook-and-twitter.html.

- Martin, Kirsten. Recommending an Insurrection: Facebook and Recommendation Algorithms. New York: Auerbach Publications, 2022.

- McCoy, Jennifer, Tahmina Rahman, and Murat Somer. “Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy: Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities.” American Behavioral Scientist 62, no. 1 (2018): 16–42. doi:10.1177/0002764218759576.

- McKay, Spencer, and Chris Tenove. “Disinformation as a Threat to Deliberative Democracy.” Political Research Quarterly 74, no. 3 (2021): 703–717. doi:10.1177/1065912920938143.

- Merkel, Wolfgang. “Embedded and Defective Democracy.” Democratization 11, no. 5 (2007): 33–58. doi:10.1080/13510340412331304598.

- Meyer, Jan Nicola, and Jana-Maria Böswald. Mapping the Tools, Tactics and Narratives of Tomorrow’s Disinformation Environment. Berlin: Democracy Reporting International, 2022. https://democracyreporting.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/images/62c8333ec3aea.pdf.

- Mouffe, Chantal. “Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism.” Social Research 66, no. 3 (1999): 745–758. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40971349#metadata_info_tab_contents.

- Nagel, Michael. “Constructing Apathy: How Environmentalism and Environmental Education May Be Fostering ‘Learned Hopelessness’ in Children.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 21 (2005): 71–80.

- Neubauer, Deane E. “Some Conditions of Democracy.” American Political Science Review 61, no. 4 (1967): 1002–1009. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1953402#metadata_info_tab_contents.

- Kamenchuk, Nisbet and. “Russian News Media, Digital Media, Informational Learned Helplessness, and Belief in COVID-19 Misinformation.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 33, no. 3 (2021): 571–590. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edab011.

- Palmer, Eqan. “Fact Check: Did Donald Trump Truth Social App Top Google Play Store Chart?” Newsweek. October 19, 2022. https://www.newsweek.com/trump-truth-social-app-google-play-store-1753210.

- Pond, Philip. Complexity, Digital Media and Post Truth Politics: A Theory of Interactive Systems. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

- Ross, Amy Arguedass, Craig T. Robertson, Richard Fletcher, and Rasmus K. Nielsen. Echo Chambers, Filter Bubbles, and Polarisation: A Literature Review. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2022. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/echo-chambers-filter-bubbles-and-polarisation-literature-review.

- Safai, Yalda. “Managing the Psychological Effects of the 2020 Election.” ABC News, November 3, 2020. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/managing-psychological-effects-2020-election/story?id=73933000.

- Saglam, Koray. “The Digital Blender: Conceptualizing the Political Economic Nexus of Digital Technologies and Authoritarian Practices.” Globalizations (2022). doi:10.1080/14747731.2022.2131235.

- Sartori, Giovanni. Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Schaeffer, Carol. “How Covid-19 spread QAnon in Germany.” Coda, June 19, 2020. https://www.codastory.com/disinformation/qanon-covid19-germany/.

- Scheurman, Trent. “Comparing Social Media Content Regulation in the US and the EU: How the US Can Move Forward with Section 230 to Bolster Social Media Users’ Freedom of Expression.” San Diego International Law Journal 23, no. 2 (2022): 413–456.

- Siebenhaar, Katharina, Anja Köther, and Georg Alpers. “Dealing with the COVID-19 Infodemic.” Frontiers in Psychology 11 (2020): 1–11.

- Sinpeng, Aim. Opposing Democracy in the Digital Age: The Yellow Shirts in Thailand. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021.

- Suhr, Frauke. “Das Halten die Deutschen von Verschwörungsmythen” [This Is What the Germans Think of Conspiracy Myths]. Statista, September 14, 2020. https://de.statista.com/infografik/22882/anteil-der-befragten-dazu-was-sie-von-verschwoerungsmythen-halten/.

- Suiter, Jane. “Post-Truth Politics.” Political Insight 7, no. 3 (2016): 25–27. doi:10.1177/2041905816680417.

- Stavrositu, Carmen. “Selective Exposure.” In Encyclopedia of Social Media and Politics, edited by Kerric Harvey, 1117–1119. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 2014.

- Stroud, Natalie Jomini. “Media Use and Political Predispositions: Revisiting the Concept of Selective Exposure.” Political Behavior 30, no. 3 (2008): 341–366. doi:10.1007/s11109-007-9050-9.

- Stroud, Natalie Jomini. “Polarization and Partisan Selective Exposure.” Journal of Communication 60, no. 3 (2010): 556–576. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01497.x.

- Švedkauskas, Žilvinas, Chonlawit Sirikupt, and Michel Salzer. “Russia’s Disinformation Campaigns Are Targeting African Americans.” The Washington Post, July 24, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/07/24/russias-disinformation-campaigns-are-targeting-african-americans/.

- Svolik, Milan W. “Polarization versus Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 30, no. 3 (2019): 20–32. doi:10.1353/jod.2019.0039.

- Swire, Briony, Ullrich K. H. Ecker, and Stephan Lewandowsky. “The Role of Familiarity in Correcting Inaccurate Information.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 43, no. 12 (2017): 1948–1961. doi:10.1037/xlm0000422.

- SWNS Staff. “Nearly Half of Americans Convinced Dinosaurs Still Exist in a Remote Corner of the World.” SWNS Digital, September 6, 2021. https://uk.news.yahoo.com/nearly-half-americans-convinced-dinosaurs-151600448.html.

- Tech Transparency Project. “Capitol Attack Was Months in the Making on Facebook.” Tech Transparency Project, January 19, 2021. https://www.techtransparencyproject.org/articles/capitol-attack-was-months-making-facebook.

- Teorell, Jan, and Axel Hadenius. “Democracy Without Democratic Values: A Rejoinder to Welzel and Inglehart.” Studies in Comparative International Development 41, no. 3 (2006): 95–111. doi:10.1007/BF02686238.

- Thomas, Elise, and Albert Zhang. ID2020, Bill Gates and the Mark of the Beast: How Covid-19 Catalyses Existing Online Conspiracy Movements. Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep25082#metadata_info_tab_contents.

- Timberg, Craig, Elizabeth Dwoskin, and Reed Albergotti. “Inside Facebook, Jan. 6 Violence Fueled Anger, Regret over Missed Warning Signs.” The Washington Post, October 22, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/10/22/jan-6-capitol-riot-facebook/.

- Tolan, Casey. “The Operative.” CNN, 2021. https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2021/06/us/capitol-riot-paths-to-insurrection/amy-kremer.html.

- Tucker, Joshua, Andrew Guess, Pablo Barberá, Cristian Vaccari, Alexandra Siegel, Sergey Sanovich, Denis Stukal, and Brendan Nyhan. Social Media, Political Polarization, and Political Disinformation: A Review of the Scientific Literature. 2018. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3144139.

- Vaccari, Cristian, and Andrew Chadwick. “Deepfakes and Disinformation: Exploring the Impact of Synthetic Political Video on Deception, Uncertainty, and Trust in News.” Social Media & Society 6, no. 1 (2020). doi:10.1177/2056305120903408.

- Volk, Sabine. “Political Performances of Control During COVID-19: Controlling and Contesting Democracy in Germany.” Frontiers in Political Science 3 (2021): 1–16.

- Vosoughi, Soroush, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral. “The Spread of True and False News Online.” Science 359, no. 6380 (2018): 1146–1151. doi:10.1126/science.aap9559.

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2017. https://rm.coe.int/information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-researc/168076277c.

- Welzel, Christian, and Ronald Inglehart. “Political Culture, Mass Beliefs, and Value Change.” In Democratization, edited by Christian Haerpfer, and Patrick Bernhagen, 126–144. commiOxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Wenzel, Andreas. “To Verify or to Disengage: Coping with “Fake News” and Ambiguity.” International Journal of Communication 13 (2019): 1977–1995. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/10025/2636.

- Wong, Julia Carrie. “Down the Rabbit Hole: How QAnon Conspiracies Thrive on Facebook.” The Guardian, June 25, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/jun/25/qanon-facebook-conspiracy-theories-algorithm.

- World Health Organization. “Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Promoting Healthy Behaviours and Mitigating the Harm from Misinformation and Disinformation.” World Health Organization, September 23, 2020. https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-covid-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation.

- Zadrozny, Brandy. “‘Carol’s Journey’: What Facebook Knew About How It Radicalized Users.” NBC News, October 23, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/facebook-knew-radicalized-users-rcna3581.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile books, 2019.