ABSTRACT

Between 2014 and 2017, no less than 10 different non-governmental organizations (NGOs) conducted maritime Search and Rescue (SAR) operations off the coast of Libya. By rescuing over 100,000 migrants in three years, these NGOs became the largest provider of SAR in the Mediterranean. The theory of institutionalism suggests that organizations conducting similar activities are likely to converge in a process of mimetic isomorphism, deliberately imitating one another to increase their effectiveness and cope with uncertainty. These 10 SAR NGOs, however, developed two different rescue models: While some rescued migrants and disembarked them in Italian ports, others only simply assisted those in distress until the arrival of another ship transporting them to land. They also cooperated with Italian and European authorities to different degrees. Why did SAR NGOs imitated many elements of existing non-governmental rescue models, but discarded some others? This article argues that differences in material capabilities and organizational role conceptions are crucial to explain why newer SAR NGOs have imitated most but not all of their predecessors’ policies, engaging in a process of “selective emulation.”

Since 2012, the large number of migrants dying at sea while trying to reach Italy has turned the Southern Mediterranean sea into the deadliest border worldwide (International Organization for Migration, Citation2016; UNHCR, Citation2016). Several non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have attempted to mitigate this humanitarian emergency by conducting maritime search and rescue (SAR) operations. Between 2014 and August 2017, no less than 10 NGOs conducted SAR missions off the coast of Libya, providing a crucial contribution to rescuing migrants at sea.

Institutionalist scholarship has long noted that organizations conducting the same types of activities are likely to converge in a homogenizing process, developing similar structures and patterns of behavior. This “constraining process that forces one unit in a population to resemble other units that face the same set of environmental conditions” is referred to as “institutional isomorphism” (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983, p. 149). DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) identified three mechanisms of isomorphic convergence: coercive, mimetic, and normative isomorphism. The notion of coercive isomorphism embraces the different factors compelling organizations to abide by a certain behavior, such as existing international and domestic legal obligations. Normative isomorphism stems from organizations members’ shared adherence to the same professional codes, ethical standards, and logics of appropriateness. Mimetic isomorphism is shaped by organizations’ tendency to deliberately emulate structures and procedures seen as appropriate and successful.

In order to ensure their organization’s survival, institutional entrepreneurs tend to emulate existing, off-the-shelf solutions to the problems they face, mimicking the strategies of those actors that have already successfully coped with such challenges to increase their effectiveness and enhance their legitimacy (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983; Scott, Citation1995; Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977). Consequently, emulation should be especially pronounced in novel fields characterized by tight time constraints, a high degree of uncertainty, and the presence of small, newly established organizations still lacking legitimacy, know-how, and institutional memory.

Consistent with these institutionalist hypotheses, several studies note that both large international NGOs and small local charities display strong isomorphic tendencies (Brass, Citation2016; Collinson, Citation2016; Donini, Citation2010; Barnett & Weiss, Citation2008; Barnett, Citation2005). As argued by Cooley and Ron (Citation2002), NGOs internalize the “goals, and methods of their institutional environment through imitation and isomorphism” (p. 13). Tight professional networks, personnel and information exchanges, reliance on the same pool of donors, a similar sense of mission, and the urgency of ongoing humanitarian emergencies provide strong incentives for humanitarian NGOs to adopt the solutions already proven effective by others (Collinson, 2016, p. 15; Barnett, Citation2005, pp. 729–730).

The tendency to adopt off-the-shelf templates and procedures should be even more pronounced in the case of non-governmental maritime rescue for a host of different reasons. The first is the newness and small size of most SAR NGOs, which could rely on very limited in-house resources and expertise. The second is the novelty of non-governmental SAR. Even large organizations with extensive experience in providing humanitarian relief on land such as Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) and Save the Children had no previous experience in conducting maritime rescue. As a novel activity, non-governmental SAR was shrouded in uncertainty, posing new logistical hurdles and legal risks such as being prosecuted for abetting illegal migration. Last, the shortage of SAR assets off the Libyan coast after the end of the Italian Navy operation Mare Nostrum prompted all SAR NGOs to deploy boats at sea as quickly as possible to prevent the loss of migrants’ lives. All these factors should provide especially strong incentives for newer SAR NGOs to adopt the solutions that had already been proven safe, lawful, and effective by their predecessors, thereby circumventing uncertainty and reducing the learning costs and preparation time required to devise new structures and procedures from scratch.

Still, in spite of such strong incentives to emulate each other, NGOs operating at sea did not converge in the adoption of identical rescuing models. Indeed, newer SAR NGOs adopted most but not all of their predecessors’ policies. Specifically, some organizations decided to not engage in the disembarkation of migrants on dry land, refused to accept European states’ funding, refrained from cooperating against human smugglers, and did not sign the code of conduct on maritime rescue drafted by the Italian government. Why did SAR NGOs imitated many elements of existing non-governmental rescue models, but discarded some others? This article explains this puzzle by arguing that SAR NGOs engaged in a process of “selective emulation.” Selective emulation, defined as organizations’ tendency to emulate some aspects of the models already developed by their predecessors but discard others, is primarily shaped by organizations’ varying material capabilities and their different role conceptions. Accordingly, organizations only tend to imitate those existing operational models that are both compatible with the financial and operational assets at their disposal and consistent with their understanding of the role they should perform.

Different factors explain the rapid proliferation of SAR NGOs. Since the launching of operation Mare Nostrum in October 2013, the Italian government accepted the disembarkation of all migrant rescued offshore Libya in its territory. As a result, non-governmental migrant rescue became a lawful, feasible, and financially viable activity for NGOs to perform (Cusumano, Citation2017, pp. 94–95). Only in late 2017 did Italian authorities turn increasingly critical of non-governmental SAR. In August 2017, the Ministry of Interior drafted a code of conduct for all maritime rescue charities, required to collaborate in the fight against human smugglers and accept the presence of law enforcement personnel on board (Cusumano, Citation2019). Hostility to SAR NGOs culminated in the summer of 2018, when Italy declared its ports closed to all foreign-flagged vessels (Cusumano & Gombeer, Citation2018, p. 1). Until August 2017, however, NGOs could rely on a more permissive legal and political environment to conduct SAR, which offered comparatively fewer logistical and security challenges than most crisis scenarios on land.

Thanks to its feasibility and limited costs, maritime SAR proved financially viable even for small, newly established charities (Cusumano, Citation2017, p. 94). Humanitarianism at sea has benefitted from much less scholarly attention than its counterpart on land. Several studies have examined the discourses, visuality, and implications of European maritime border control and anti-smuggling operations (Garelli & Tazzioli, Citation2018; Dijstelbloem, Van Rekum, & Schinkel, Citation2017; Van Reekum, Citation2016). Some studies have specifically focused on the dilemmas of “humanitarian borderwork” (Pallister-Wilkins, Citation2017) and humanitarian action at sea specifically (Del Valle, Citation2016, Cusumano, Citation2019). Scholarship on maritime rescue NGOs has focused on the role of NGOs in “repoliticizing” the migration crisis (Cuttitta, Citation2017, pp. 650–651) and examined the discourses and political stance of the three NGOs operating in 2015 (Stierl, Citation2018). Theory-based studies seeking to explain the different approaches developed by all these NGOs operating at sea, however, remain missing.

By systematically examining the structure and behavior of the NGOs rescuing migrants off the coast of Libya through the lens of institutionalist theory, this article pursues two goals. Firstly, it contributes to the study of migrations across the Mediterranean and the role of NGOs in providing maritime human security. As NGOs have offered a key contribution to mitigating the loss of life at sea but also been increasingly criticized as a pull factor of migrations, a comprehensive study of maritime charities’ rescue models provides timely policy-relevant insights. Secondly, it offers new theoretical insights into the study of humanitarianism and institutional isomorphism in general by conceptualizing the behavior of SAR NGOs as a process of selective emulation and showing the importance of role conceptions in inhibiting or enabling collective actors’ propensity to imitate each other.

As a novel activity characterized by strong urgency and uncertainty, the non-governmental provision of SAR can be identified as a most likely case for mimetic isomorphism to take place. Assessing why even most likely cases do not entirely fulfill theoretical expectations allows for gauging the weaknesses of existing theories and identifying the omitted variables to be incorporated in order to increase their explanatory power, thereby offering an important contribution to theory development (Levy, Citation2008, p. 12; George & Bennett, Citation2005, p. 9). Differences and similarities between non-governmental providers of SAR are examined by conducting a structured, focused comparison (George & Bennett, Citation2005, pp. 67–73) of all the charities that conducted SAR operations in the Central Mediterranean between 2014 and August 2017. This study builds on evidence gathered through document analysis, quantitative data mining from the Italian Coast Guard headquarters in Rome, and 18 semi-structured interviews with spokespersons from all SAR NGOs and officers from the Italian Coast Guard and Navy, conducted between November 2015 and the end of 2017. Additional data was collected by participating in four workshops involving military, law enforcement, and humanitarian personnel and two meetings of all NGOs’ representatives in 2016 and 2017. Last, this study relies on fieldwork conducted in Malta and aboard Sea-Watch’s vessel in August 2016, when I spent two weeks at sea to directly observe non-governmental SAR operations.

The article is divided as follows. The first section introduces the concept of selective emulation as an analytical tool providing new insights into NGOs’ mimicking tendencies. The second examines all the charities that conducted SAR operations up to August 2017. The third section illustrates the existence of a process of selective emulation, identifying the key factors underlying newer SAR NGOs’ adoption of most but not all of their predecessors’ policies. The conclusions recap the findings of the article, acknowledge its limitations, and sketch avenues for future research.

Mimetic isomorphism as a selective process

Recent scholarship notes that isomorphism should not be understood as a deterministic process depriving organizations of agency in responding to environmental pressures, acknowledging that institutional complexity belies a deterministic understanding of isomorphic processes (Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin-Andersson, & Suddaby, Citation2013, pp. 6–7; Battilana & Lee, Citation2014; Beckert, Citation2010). Indeed, factors like cultures and tradition may play an important role in inhibiting the emulation of existing models (Jonsson, Citation2009). Scholarship on NGOs resonates with this argument, acknowledging the persistence of notable differences among charities providing the same type of activities (Kontinen & Onali, Citation2017; Schneiker, Citation2015; Stroup, Citation2012; Ramanath, Citation2009). While organization-specific factors may inhibit isomorphism, international relations scholars have not systematically examined the mechanisms underlying NGOs’ propensity to adopt some but not all of existing organizational models.

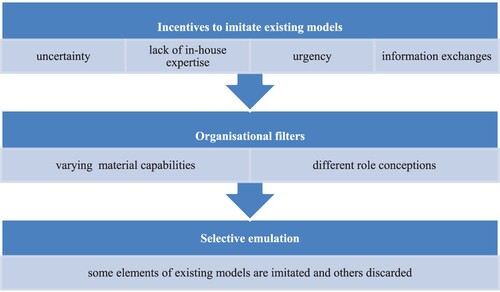

The concept of selective emulation provides an analytical tool that can account for the coexistence of strong mimetic tendencies and enduring differences across organizations, helping explain why certain elements of the solutions experimented successfully by other actors are imitated while some others are not. Emulation across military forces, for instance, is inhibited or enabled by organization-specific filters that inform which elements of existing doctrines are identified as suitable to emulate (Schmitt, Citation2016, p. 471; Dyson, Citation2010, pp. 23–27). Filters to emulation can be both material and ideational. Firstly, organizations seeking to imitate certain types of behavior need to possess the financial, material, and human resources that make such behavior feasible. Hence, selective emulation processes are informed by the availability of certain material capabilities. Organizations’ behavior, however, is not solely shaped by their material capabilities, but also informed by normative and cultural factors. Social identities establish “rule of membership and behavior” (Fearon & Laitin, Citation2000, p. 848), shaping organizations’ interpretation of different international norms (Legro, Citation1995, p. 33), and their varying understanding of their core mission (Schneiker, Citation2015; Kier, Citation1997). The notion of role conception, defined as the shared beliefs of the proper purpose of specific collective actors, is especially important in shaping organizations’ self-understanding of which tasks are appropriate for them to perform and which others should be discarded as peripheral or inappropriate (Cusumano, Citation2015, p. 223) ().

Role conceptions—already used to investigate a variety of actors ranging from states at large (Brummer & Thies, Citation2012; Holsti, Citation1970) to military organizations (Cusumano, Citation2015) and media outlets (Holton & Coddington, Citation2016)—can be fruitfully applied to NGOs too. Recent scholarship on humanitarianism has forcefully stressed the need to consider NGOs as “purposive actors with their own identities and interests” rather than “passive carriers of transnational norms” (Stroup, Citation2012, p. 7; Schneiker, Citation2015). Humanitarian NGOs constantly “debate about who they are and what practices are reflective of their identity” and, conversely, “who they believe they are not and the practices they deem illegitimate” (Barnett & Weiss, Citation2008, p. 5). NGOs’ organizational structures and actions are not solely informed by a logic of consequences aimed at minimizing human suffering, but also shaped by a logic of appropriateness (Stroup & Wong, Citation2013; Heyse, Citation2006).

While sharing the same commitment to alleviating suffering, humanitarian organizations differ considerably on which strategies they consider as appropriate to pursue this goal. Far from sharing a single, cohesive role conception, humanitarian NGOs are set apart by two main cleavages. Firstly, NGOs disagree on whether they should focus solely on addressing human suffering or whether their mission ultimately requires addressing the root causes of humanitarian crises (Scott-Smith, Citation2016; Rubenstein, Citation2015). Hence, while some organizations refrain from being too vocal in criticizing local authorities, others are more outspoken in acting as whistleblowers and engaging in naming and shaming. This varying commitment to advocacy implies that not all NGOs attach the same value to the humanitarian principles of neutrality, which prevents them from taking sides in political controversies. Secondly, and relatedly, NGOs differ in their relationship with political authorities: While some are more willing to cooperate with military and law enforcement organizations and other government agencies in exchange for access to crisis scenarios and greater effectiveness in delivering aid, others attach greater value to their independence from political actors.

According to Stoddard (Citation2003, pp. 1–2), two main roles can be identified. Dunantist organizations are more confrontational toward governments and keener on seeing humanitarian work as a platform for advocacy. Wilsonian organizations, by contrast, tend to develop a more cooperative relationship with state authorities in order to gain access to the humanitarian space. Consequently, they often embrace a narrower interpretation of humanitarianism, concentrating on addressing suffering effectively rather than denouncing its root causes. This divide between pragmatists and activists is also acknowledged by Barnett (Citation2009), who distinguishes between the salvational, transformative ethos of “alchemical humanitarianism” and the more pragmatic mindset of “emergency humanitarianism” (p. 39). According to Krause (Citation2014), these differences derive from how NGOs seek their legitimacy. Wilsonian organizations resort to state authorities as external providers of legitimacy and material resources. Dunantist NGOs, on the other hand, seek legitimacy by showing independence from those authorities. Organizational role conceptions thus play a key role in hindering isomorphic convergence across NGOs by, for instance, discouraging some organizations from using private security companies (Schneiker, Citation2015, pp. 38–40).

As the remainder of this article will show, differences in material capabilities and role conceptions are crucial to explain why SAR NGOs emulated most but not all of their predecessors’ policies. First, however, a brief overview of these organizations will be provided.

SAR NGOS under empirical analysis

As illustrated by the previous section, non-governmental maritime SAR is an organizational field displaying especially strong incentives for mimetic isomorphism. SAR NGOs, however, did not converge in the adoption of identical rescue policies. This section briefly compares the models developed by the 10 organizations operating off the coast of Libya between 2014 and August 2017.

The Migrant Offshore Assistance Station (MOAS)

The Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) is a philanthropic initiative headquartered in Malta. Its founders, the owners of a business intelligence firm, purchased a vessel, equipped it with drones and manned it with several personnel with a background in the Maltese Navy and Coast Guard. In 2015, MOAS expanded its operations by chartering a second ship and relying on the Italian Red Cross to provide medical support aboard for migrants. Since the summer of 2014, this Maltese charity has detected and rescued migrants in distress, disembarking them in an Italian port indicated by Rome’s Maritime Rescue Coordination (MRCC). MOAS obtained funds primarily through small donations largely obtained through crowd funding. The large costs faced, however, also prompted its funders to call for “the generous support of public donors to keep saving lives” (Migrant Offshore Aid Station, Citation2016).

As argued by Italian Coast Guard and Navy interviewees, the background of many MOAS personnel in the Maltese armed forces was key to rapidly establishing trust within Italian authorities, allowing this Maltese charity to present itself as a credible provider of maritime rescue. Moreover, MOAS willingly assisted Italian authorities in the conduct of law enforcement activities by, for instance, handing over drone footage to be used in court against suspect human smugglers (Cuttitta, Citation2017, p. 644). Accordingly, MOAS was the first NGO which signed the Italian government code of conduct on maritime migrant rescuing. In September 2017, MOAS decided to suspend its Mediterranean rescue operations, relocating to South Asia to assist Rohingya refugees escaping Mynamar. However, its model—which proved effective, viable, and (at least initially) supported by national governments and civil society alike—inspired several other NGOs to start their own SAR operations off the coast of Libya. Still, not all aspects of MOAS’ behavior were uncritically adopted by other NGOs.

Médecins sans Frontières

Unlike MOAS, a small organization established with the sole purpose of conducting maritime SAR, MSF is a large international medical NGO with an annual budget of over a billion euros (Médecins sans Frontières, Citation2016; Stroup, Citation2012). Although MSF has frequently provided humanitarian relief to migrants, it long remained wary of conducting SAR due to the uneasy compromises that such an activity imposes on humanitarian principles. It was precisely MSF’s unwillingness to engage in SAR operations during the Vietnamese boat people crisis in 1978–1979 that led Bernard Kouchner and others to leave the organization and found Medicins Du Monde (Del Valle, Citation2016, p. 35).

Starting in 2015, three different MSF operational branches became involved in Mediterranean migrant rescue. MSF Amsterdam decided to circumvent its lack of maritime expertise by partnering with other organizations. It therefore initially reached an agreement with MOAS and later started a partnership with another NGO, SOS-Méditerranée (see details below), providing medical personnel and covering part of SAR operations’ costs. Two other branches of the organization, by contrast, developed independent SAR capabilities. In April 2015, MSF Barcelona started operations from an own ship. A few weeks after, MSF Brussels too launched an independent rescue mission by chartering another one. Both vessels conducted their operations by approaching boats in distress upon MRCC authorization, transferring migrants on board and shuttling them into the ports indicated by Italian authorities. In August 2017, MSF refused to sign the code of conduct drafted by the Italian government, which was seen as infringing humanitarian principles. The main bone of contention was Italian authorities’ request to accept the presence of police officers on board of the vessels. This demand was considered an unacceptable violation of MSF’s policy of not allowing arms into any of their missions worldwide.

Sea-Watch

Sea-Watch is a German charity which started operating in May 2015 on an old, fishing vessel manned with a handful of volunteers. Unlike MOAS and MSF, Sea-Watch long refrained from disembarking migrants in Italian ports. Its Southern Mediterranean operations were only based on the patrolling of international waters off western Libyan shores. After receiving a distress call or detecting a boat, Sea-Watch personnel would approach migrants to provide them with life vests, drinking water and urgent medical treatment. When necessary, migrants would be temporarily hosted aboard until a bigger ship would dispatched by the Italian MRCC to shuttle migrants to an Italian port (Cusumano, Citation2017, pp. 96–97; Cuttitta, Citation2017, pp. 642–643). The limited costs of this specific rescue model and their effective fundraising campaigns allowed Sea-Watch to consolidate its financial base, purchase a newer boat, and start new missions. In the spring of 2017, for instance, Sea-Watch started operation Moonbird, relying on a tourist plane flying reconnaissance flights above the Libyan coast to both better spot migrants and document the disengagement of EU naval assets from the rescue zone.

Sea-Watch explicitly sought to find other imitators in civil society, supporting other organizations in starting their own rescue operations by disseminating information and allowing members of other NGOs, like Sea-Eye and Jugend Rettet, to join Sea-Watch’s crews in missions at sea (Sea-Watch, Citation2016). Like MSF, Sea-Watch refused to sign the code of conduct on migrant rescuing, seen as an infringement of humanitarian principles.

Patrolling and rescuing NGOs: Sea-Eye, Jugend Rettet, Lifeboat, BRF, and Proactiva

Nowhere is the process of emulation promoted by Sea-Watch personnel more evident than in the activities of Sea-Eye, Jugend Rettet, Lifeboat, and ProActiva Open Arms. Sea-Eye started operations in May 2016 by resorting to a reconverted fishing boat named after the organization, complemented in late 2017 by a second small vessel. The operational model and even the name of Sea-Eye closely follow Sea-Watch’s model. Like Sea-Watch, Sea-Eye decided to conduct two-week missions run by volunteers and consisting in spotting boats in distress and providing life vests, drinking water, and medical treatment to those in need until the arrival of a larger boat transferring migrants to dry land.

The same approach was followed by Jugend Rettet, a young adults Berlin-based organization which started operations in July 2016. Like Sea-Watch and See-Eye, Jugend Rettet ran two-week long maritime missions run primarily by volunteers and financed through crowd funding donations, which allowed for purchasing and reconverting a fishing vessel. As a newly arrived organization, Jugend Rettet sought the advice of previously established SAR NGOs before starting operations, adopting the same rescue procedures of its German predecessors Sea-Watch and Sea-Eye. Soon after refusing to sign the code of conduct, Jugend Rettet had to stop its activities as its ship was confiscated by Italian authorities. The investigation against the German NGO and some of its personnel, charged with abetting illegal immigration, is still ongoing at the time of writing (Cusumano, Citation2019, p. 113).

The LifeBoat project is another German NGO that started operations in the same period as Sea-Eye and Jugend Rettet from a small, chartered lifeguard vessel. Like Sea-Eye, the Lifeboat project relied on several personnel previously volunteering for Sea-Watch, capitalizing on their experience to rapidly start their rescuing operations. In protest against the tightening grip against non-governmental rescuers epitomized by the code of conduct and facing budgetary problems, the German charity suspended its activities in August 2017.

In the summer of 2016, the Netherlands-based Boat Refugee Foundation (BRF), previously operating in Lesbos—decided to start operations off the coast of Libya. In the months prior to its first operations, the BRF actively networked with the NGOs that were already active in the provision of SAR, seeking advice from Sea-Watch. BRF activities, based on assisting migrants without transporting them to land, were however short-lived. In November 2017, the organization suspended operations due to weather conditions, deciding not to restart a maritime rescue mission in 2017 due to insufficient funding.

Proactiva Open Arms was established as the not-for-profit branch of Proactiva, a firm from Barcelona providing lifeguard services on Spanish coasts. Initially operating in the Aegean, Proactiva relocated to the Central Mediterranean in June 2016, initially conducting SAR from the sailing yacht donated by an Italian millionaire and later chartering the vessel previously used by the BRF and purchasing another. Due to the small size of its vessel, the Spanish charity too refrained from shuttling migrants to Italian ports, limiting its activities to assisting those in danger of drowning. As the charitable spin-off of a maritime safety firm, developed a more pragmatic approach toward Italian authorities than its German counterparts. Accordingly, it was the third organization which signed the code of conduct, seen as crucial to preserve a smooth collaboration with Italian authorities.

Rescue and disembarkation NGOs: SOS Méditerranée and Save the Children

While Sea-Eye, Jugend Rettet, Lifeboat, the BRF and Proactiva all followed Sea-Watch’s model, refraining from transporting migrants to dry land, SOS Méditerranée and Save the Children replicated the approach initially developed by MOAS, conducting fully-fledged SAR operations. SOS Méditerranée is a network of three NGOs with headquarters in Germany, France, and Italy. It conducted maritime SAR operations from a large vessel capable of operating in all weather conditions and transporting up to 800 migrants to dry land. The crew consists of a rescue team composed of SOS Méditerranée’s own personnel and a medical unit provided by MSF Amsterdam, which would also cover part of the ship’s running costs. In exchange for this support, SOS Mediterranée accepted to refrain from accepting EU governments’ donations, seen by MSF as incompatible with their commitment to neutrality and their willingness to distance themselves from European authorities. After initially considering the code of conduct drafted by the Italian government as incompatible with humanitarian principles, SOS Méditerranée eventually accepted to sign the document. They did so, however, only after obtaining the attachment of a follow-up statement toning down some of the provisions of the code and specifying that police officers will not be allowed on board without a warrant.

In September 2016, the large number of minors crossing the Mediterranean also urged Save the Children to join SAR operations in the Central Mediterranean. Unlike all other SAR charities except for MSF, Save the Children is a large NGO with an annual budget of over $2 billion. After chartering a large ship, Save the Children started rescuing migrants off the coast of Libya and disembarking them in the ports indicated by the Italian MRCC. Like MOAS, Save the Children closely cooperated with Italian authorities, complying with their request to hand over evidence used by Italian courts to prosecute suspect smugglers. Consequently, Save the Children immediately accepted signing the code of conduct, accepting the presence of law enforcement authorities on board whenever necessary. Unlike other NGOs, Save the Children also relied on private security contractors from the Italian firm IMI Security Services, which provided both unarmed guards and professional rescuers. Information provided by IMI contractors, one of whom turned out to be an undercover Italian police agent, were used by Italian authorities to prosecute Jugend Rettet for abetting illegal immigration ().

Table 1. NGOs providing SAR off the coast Libya (August 2014–August 2017).

NGOs’ contribution to migrant rescuing

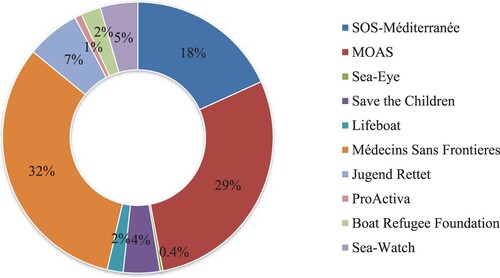

The charities briefly described above have provided a crucial contribution to mitigating the maritime humanitarian crisis off the coast of Libya. In 2016, NGOs became the largest provider of SAR, rescuing almost 47,000 migrants. As illustrated by the elaboration of Italian MRCC data below, however, not all charities contributed to rescuing operations to the same degree. As the chart shows, organizations with larger, faster vessels capable of operating in rough weather conditions proved capable of rescuing the safety of a much larger number of people. Moreover, the disembarkation of migrants on dry land arguably provided NGOs with more opportunities for media engagement and greater publicity and visibility. Why then did not all NGOs converge in the adoption of the rescue model first developed by MOAS? Conceptualizing the behavior of SAR NGOs as a process of selective emulation shaped by varying material capabilities and role conceptions helps explain this enduring divergence. This will be done in the next section ().

Differences and similarities across SAR NGOs

A systematic analysis of NGOs involved in the provision of SAR shows the coexistence of strong, pervasive isomorphic tendencies and few but significant persisting differences. This section identifies the main analogies between SAR NGOs, showing the importance of emulation processes in explaining these glaring similarities. It then focuses on the limits of mimetic isomorphism at sea by outlining the few enduring differences across SAR NGOs. Last, this section conceptualizes SAR NGOs’ behavior as a process of selective emulation, using the evidence collected to identify the organizational filters explaining SAR NGOs’ tendency to imitate some of their predecessors’ policies but not others.

Isomorphic convergence across SAR NGOs

The possibility for newer organizations to emulate existing non-governmental rescue models eased the proliferation of SAR NGOs. As noted by the spokespersons of all the organizations which started operations in 2016, MOAS first and then MSF and Sea-Watch provided an “inspiration,” showing the feasibility of non-governmental SAR. Hence, the very proliferation of SAR NGOs can be partly conceptualized as the outcome of an emulation process. Similarities in the policies of SAR NGOs also abound. The charities involved in maritime rescue developed almost identical fundraising campaigns, based on advertising the number of migrants saved and using similar pictures and almost identical catchphrases, such as “no one deserves to die at sea” (MOAS), “don’t forget them at sea” (Sea-Watch), “everyone in maritime emergencies deserves rescue” (Jugend Rettet).

Moreover, all SAR NGOs conducted their operations under the coordination of the Italian MRCC in Rome. It was often the MRCC which directed the closest vessel to the rescuing of a migrant boat. In other cases, migrants were directly spotted by NGOs. All organizations, however, waited for Italian Coast Guard authorization before taking migrants aboard. This standard operating procedure was justified by the need to maintain a smooth working relationship with Italian authorities and minimize the risk of prosecution for abetting illegal immigration. All NGOs also spontaneously followed MRCC advice on where to deploy their assets, patrolling international waters off the Western coast of Libya. Only in exceptional circumstances such as the presence of a sinking boat did SAR NGOs entered in Libyan territorial waters or acted without explicit MRCC authorization (Cusumano, Citation2019).

Security concerns also prompted SAR NGOs to develop similar security policies. Until August 2016, most charities had no meaningful security arrangements in place. However, the August 17, 2016 attack against MSF’s Bourbon Argos, which was repeatedly shot against and then boarded by a group of armed Libyans, required SAR NGOs to engage in a collective discussion on security policies. Accordingly, all charities standardized their protective protocols by installing armored panic rooms and purchasing alarm systems alerting the European Union's (EU) military mission EUNAVFOR Med “Sophia” and the Italian Navy's operation Mare Sicuro of ongoing attacks.

Furthermore, the staffing of NGOs’ crews and their command structures also reveal remarkable similarities. All NGOs equipped their maritime missions with three different types of expertise, ensuring a combination of nautical know-how, medical experience, and media skills. To that end, all charities welcomed the presence of professional photographers, newspaper journalists, and tv crews on board. Unforeseeable exceptions aside, the time spent at sea by all charities’ crews was two weeks. Moreover, all NGOs developed similar command structures based on the coexistence of a ship masterresponsible for all matters concerning governing the vessel—and a head of mission—focusing on the provision of humanitarian relief.

Mechanisms of mimetic isomorphism are key to explaining these similarities. Indeed, evidence from interviews and document analysis provides ample evidence that SAR NGOs consistently and deliberately mimicked one another. The novelty of the problems faced, the need to start operations quickly, and the small size of most organizations all created strong incentives for adopting solutions proven effective by the charities already operating at sea. All interviewees from NGOs noted the important role played by emulation, and six of them explicitly acknowledged that their own organization imitated their predecessors. For instance, Sea-Eye’s emulation of Sea-Watch is—as admitted by two interviewees—apparent from its very name. One spokesperson from SOS-Méditerranée explicitly defined his organization as the outcome of a “healthy process of emulation.”

The propensity to imitate solutions effectively experimented by their predecessors was eased by regular communications between activists and the eagerness of the first NGOs to share their experience with newcomers. Sea-Watch, for instance, had the explicit goal of finding imitators, encouraging “other people to start acting themselves” and providing “advice based on our experience” (Sea-Watch, Citation2016). NGO crews were in touch via radio communications between ships and a WhatsApp group. The frequent contacts of NGO personnel both at sea and at the directing level—thanks to the “Shade Med” and “Una Vis” stakeholder meetings organized by the Italian Navy and Coast guard—facilitated the exchange of information and best practices. On many occasions, personnel were handed over from one organization to another to ensure a swift transfer of existing know-how. Several volunteers from Sea-Eye, Jugend Rettet, and the BRF, for instance, acquired their first SAR experience by participating in Sea-Watch’s missions.

The limits of isomorphism: differences between SAR NGOs

Consistent with institutionalist expectations, mimetic isomorphism was pervasive among SAR NGOs. Newer charities, however, emulated most but not all of the previously developed by their predecessors. Specifically, the organizations continued to display two types of persisting differences: They developed two models of rescue policies, and they cooperated to different degrees with Italian and European authorities.

To begin with, SAR NGOs developed two different rescue models: the MOAS model and the Sea-Watch model (Cusumano, Citation2017, p. 96). The first NGO conducting SAR operations (MOAS) did so by disembarking migrants in the ports indicated by Italian authorities. Among the NGOs which subsequently started conducting SAR, however, only MSF, SOS Méditerranée, and Save the Children decided to follow MOAS’ approach. Sea-Watch, Sea-Eye, Pro-Activa, Jugend Rettet, and the BRF, by contrast, conducted operations consisted primarily in patrolling, waiting for another ship to disembark migrants ashore.

The varying willingness to disembark migrants in Italy, however, was not the only major difference between SAR NGOs. Migrant rescue charities also diverged in their relationship with European state authorities in two key respects: their varying propensity to accept public funding and their varying willingness to cooperate with military and law enforcement organizations. Even organizations sharing the same rescue model like MOAS, MSF, SOS Méditerranée and Save the Children differ widely in this regard. Simultaneously operating two vessels equipped with drones proved very demanding for a small organization like MOAS, which proactively called for public funds to continue its SAR operations. NGOs’ willingness to accept public funding too, however, was not solely shaped by the size of the organization. Indeed, even a much larger INGO like Save the Children proactively looked for government donations, securing an agreement with the United Kingdom Department for International Development to partly fund their maritime rescue operations. By contrast, much smaller charities like Sea-Watch and Jugend Rettet declared their unwillingness to accept funding from European governments and the EU at large, considered responsible for migrants’ plight. This position is shared by MSF, which—consistent with its vocal criticism of EU migration and asylum policies—refused EU funding for projects associated with the migration crisis in early 2016. SOS Méditerranée too renounced EU funding in order for its cooperation with MSF to continue.

Differences in NGOs’ commitment to distance themselves from European governments are epitomized by their varying willingness to cooperate with Italian authorities and EU agencies in combatting human smuggling. In May 2015, for instance, a suspect smuggler was identified and prosecuted thanks to MOAS’ drones footage. Save the Children too openly shared information with Italian authorities in several occasions. MSF, by contrast, considered disclosing information that could be used as court evidence as incompatible with humanitarian principles, deliberately refraining from using surveillance assets like drones and taking videos and pictures that could potentially contribute to identifying suspect smugglers. MOAS’ willingness to cooperate closely with Italian authorities informed its personnel policies too. The fact that MOAS staffed its crew with former Maltese military personnel who were already known to Italian authorities was key to gaining the trust of the MRCC in Rome (Cusumano, Citation2017). This strategy, however, was discarded as inappropriate by other NGOs, which even criticized MOAS as a “paramilitary organization.”

SAR NGOs’ different approaches to collaborating with Italian authorities are clearly illustrated by their different response to the request to sign the code of conduct. MOAS and Save the Children immediately accepted signing the code, soon followed by Proactiva Open Arms. Sea-Eye too eventually decided to sign, albeit reluctantly. SOS Méditerranée followed only after they successfully obtained the drafting of an additional document which toned down some of the code’s requests. By contrast, MSF, Sea-Watch, Jugend Rettet, and Lifeboat did not sign the document. The obligations for NGOs to cooperate in anti-smuggling activities by retrieving engines and makeshift boats and accept the presence of police personnel on board, seen as a violation of the principles of neutrality and independence, are especially important bones of contention between Italian authorities and non-signatory organizations (Cusumano, Citation2019).

Explaining selective emulation

An analysis of SAR NGOs operating off the coast of Libya shows the coexistence of pervasive emulation tendencies and a few enduring differences. Why were many elements of existing models emulated but others were not? This section sheds light on the factors underlying NGOs’ tendency to selectively emulate many but not all of existing non-governmental rescuing policies.

Consistent with the selective emulation mechanisms developed above, the empirical overview of SAR NGOs conducted shows that two factors played a key role in informing charities’ varying propensity to imitate their predecessors: material capabilities and organizational role conceptions. Since SAR in the Mediterranean is performed by both large and small NGOs, large differences in material capabilities are important to explain variance in non-governmental rescue procedures. As small organizations, Sea-Watch, Sea-Eye, Pro-Activa, Jugend Rettet and the BRF lacked the financial base to acquire large boats and face the high fuel costs arising from transferring migrants to ports located in Sicily or mainland Italy. Due to the slow speed of their vessels, these locations could only be reached after days of navigation. By contrast, large NGOs such as MSF and Save the Children could afford chartering, manning, and maintaining larger and faster boats.

The adoption of different rescue models, however, was not solely a matter of material capabilities. Indeed, relatively small, newly formed organizations like MOAS and SOS Méditerranée willingly accepted to disembark migrants in Italy regardless of the costs this would entail. Sea-Watch, by contrast, maintained an approach based on not shuttling migrants to Italy even after acquiring larger financial resources, which they used to fund an air patrol mission instead. The reason underlying their choice is that Sea-Watch considered SAR as an activity to be carried out by governments. Consequently, they feared that fully-fledged non-governmental SAR operations could prompt states to abdicate their responsibility and provide a justification for their inaction. For this reason, Sea-Watch developed an alternative model simultaneously seeking to mitigate the loss of life and force governments to intervene and transport migrants to dry land. The example set by Sea-Watch prompted like-minded organizations demanding EU states to conduct large-scale SAR such as Sea-Eye and Jugend Rettet to adopt the same rescue model.

Material capabilities alone also fail to account for NGOs’ varying willingness to accept public funding and cooperate with Italian and European authorities in combatting human smuggling. Understanding these differences requires an analysis of NGOs’ role conceptions, which are especially crucial to capture different charities’ interpretation of humanitarian principles and positioning vis-à-vis state authorities. As a philanthropic initiative launched by a U.S. entrepreneur and staffed by former military personnel, MOAS can be clearly identified as a Wilsonian organization dedicated to mitigating suffering by cooperating with government authorities rather than addressing its root causes. An analysis of MOAS documents perfectly illustrates the role conception of the Maltese charity, epitomized by statements like “Save lives first. Sort out the politics later” and “MOAS is not a political action group, nor do we take a side in the various debates about the influx of refugees to places of safety and opportunity. All MOAS does is help rescue humans who would otherwise drown if help was not available” (MOAS, Citation2016).

As noted by Cuttitta (Citation2017, p. 9), MOAS always privileged a prudent, non-confrontational attitude. Consequently, its workers willingly cooperated with state authorities by not only carefully complying with MRCC instructions, but also sharing information on suspect human smugglers with law enforcement agencies and proactively looking for public funding. A willingness to disembark migrants on dry land and openness to public funding also characterized the activities of Save the Children, another organization with a long history of cooperation with Western governments (Stroup & Wong, Citation2013, p. 179; Stoddard, Citation2003, p. 3). Save the Children’s pragmatic approach was further epitomized by their decision to hire private security contractors. As the guards operating on Save the Children’s vessel handed over information was used to prosecute Jugend Rettet, the decision to have private security contractor aboard a rescue boat was heavily criticized by other NGOs as not only unnecessary, but also incompatible with humanitarian principles.

MSF, by contrast, is a quintessentially Dunantist organization, whose much stronger commitment to independence from political actors prevented them from accepting state funding and cooperating too closely with Italian authorities. This mindset is clearly explained by MSF’ mission, which is not limited to the provision of relief, but also embraces the effort to denounce and address the root causes of suffering by means of temoignage, or advocacy (Del Valle, Citation2016; Stroup, Citation2012). Indeed, MSF saw the launching of SAR operations not only as an opportunity to relieve the suffering of migrants at sea, but also “spread a more humanized image of migration … alternative to the stereotypical picture of an invasion” and promote a “radical re-think of migration policy” based on the establishment of a legal and safe passage to Europe (Cuttitta, Citation2017, p. 644). As they considered EU migration policies responsible for casualties at sea, MSF did not only stay aloof from accepting European states funding, but also refrained from handing over any information on suspect smugglers to the European Border and Coast Guard (still widely known as Frontex) and Italian authorities, a form of behavior they considered incompatible with the humanitarian principles of neutrality, impartiality, and independence.

While much smaller, Sea-Watch—founded by Berlin and Hamburg-based activists with a background in the German left and conservation NGOs such as Greenpeace and its more radical counterpart Sea Shepherd—also displays a strong commitment to advocacy and whistleblowing. Their willingness to document European authorities’ disengagement from SAR operations forcefully illustrates the confrontational nature of their mission and advocacy campaigns. Sea-Watch’s role conception does not only account for their unwillingness to accept public funding and work too closely with military organizations, but also explain why they devised a rescue model seeking to prevent states from offloading their responsibilities onto civil society. By simultaneously acting as a watchdog and rescuing migrants without disembarking them to a place of safety, Sea-Watch deliberately sought to both mitigate the loss of life at sea and compel military and law enforcement assets in the area to intervene. Like-minded organizations such as Sea-Eye, the Lifeboat Project, and Jugend Rettet chose Sea-Watch’s approach as a model that was not only cheaper and more feasible, but also more appropriate for NGOs to perform.

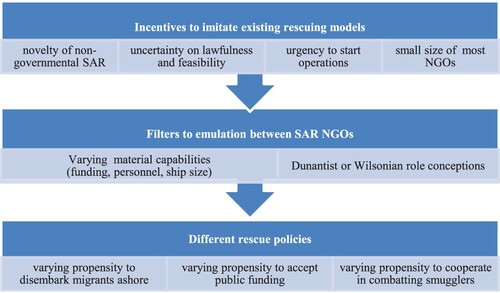

In sum, SAR NGOs’ emulation processes were enabled or inhibited by two filters: material resources and organizational role conceptions. As summarized by chart 4 below, introducing these factors into the analysis of non-governmental SAR provides key insights into why newer maritime rescuing NGOs adopted many but not all elements of the model initially developed by MOAS, engaging in a process of selective emulation ().

Conclusion

Consistent with institutionalist expectations, the organizations providing SAR offshore Libya display strong and pervasive mimetic isomorphic tendencies. The novelty of non-governmental maritime rescue, its perceived urgency, the uncertainty over its lawfulness and feasibility and the small size of most organizations all incentivized SAR NGOs’ tendency to emulate one another. Emulation eased the rapid proliferation of maritime rescue charities by reducing learning costs and allowing small organizations to start operations quickly.

Newer NGOs, however, adopted most but not all of the rescue policies developed by their predecessors. Non-governmental SAR can therefore be best described as a process of selective emulation shaped by differences in material capabilities and organizational role conceptions. Limits in financial resources, personnel and available vessels led smaller charities to refrain from imitating procedures that were deemed too demanding and costly, such as disembarking migrants to Italian ports. Moreover, varying organizational role conceptions—and consequently NGOs’ varying interpretations of humanitarian principles—led some charities to discard those policies deemed inappropriate, such as welcoming European states’ funding, cooperating in anti-smuggling activities, and accepting the presence of police personnel on board required by the Italian government code of conduct. These findings resonate with and complement recent institutionalist scholarships on non-governmental organizations, which stress the importance of identities, cultures, and role conceptions in enabling or inhibiting the imitation of certain operational models.

Although this article focuses on non-governmental migrant rescue up to August 2017, it should be noted that the evolution of SAR NGOs’ behavior in late 2017 and early 2018 confirms the importance of material capabilities and identities in shaping organizational change. In September 2017, Sea-Watch and Proactiva started to disembark migrants to dry land. This decision was made for two reasons. First, the funding collected in the previous years allowed both organizations to bear the higher costs of shuttling migrants to Italy. Second, activists grew concerned that stationing at sea while waiting for a larger ship would eventually oblige them to hand over migrants to the newly-formed Libyan coast guard, which would then take them back to Libya. As migrants in Libya face widespread abuse, Sea-Watch and Proactiva considered handing over migrants to the Libyan coast guard as incompatible with humanitarian principles.

More recent evidence also shows that selective emulation mechanisms can not only be found among migrant rescue NGOs, but even characterize civil society organizations with diametrically opposite goals. In August 2017, the right-wing organization Defend Europe, created to protect European identity from the threats allegedly posed by irregular migrants from Africa and the Middle East, endeavored to stop NGOs from disembarking rescuing migrants in Italy, chartering a boat to act as a watchdog of SAR NGOs and assist Tripoli’s Coast Guard in rescuing migrants and taking them back to Libya. As acknowledged by its activists, Defend Europe deliberately imitated the organizations it seeks to oppose, relying on strategies previously adopted successful by maritime rescue charities.

Assessing how emulation travels across organizations with radically different goals and role conceptions can shed new light into mimetic isomorphic processes. Moreover, examining whether humanitarian NGOs operating in other crisis scenarios and other types of NGOs engage in the same type of selective emulation processes would also be important to address the limitations of this study. By examining the relatively small population of NGOs conducting maritime rescue off the coast Libya in the three years between 2014 and 2017, this article could only provide a plausibility probe for the argument that humanitarian NGOs engage in selective emulation processes. Research on a broader population of charities and the evolution of their activities over a longer timeframe would corroborate the findings presented above, helping assess whether selective emulation is unique to the challenges arising from maritime rescue operations or consistently take place on land too.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript builds on the previous article entitled “Emptying the Sea with a Spoon? Non-governmental providers of migrant search and rescue in the Mediterranean,” published on Marine Policy, 75 (2017).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Eugenio Cusumano is an assistant professor in International Relations and European Union studies at the University of Leiden, the Netherlands. He obtained his PhD from the European University Institute in 2012. His research concentrates on the study of non-state actors’ involvement in crisis management both on land and at sea, with a focus on the activities of private military and security companies (PMSCs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). His work has been published in various international relations and security studies journals, such as the Journal of Strategic Studies, Armed Forces & Society, Cooperation and Conflict, International Relations, and Mediterranean Politics. He is frequently cited in international media, including The Guardian, The Independent, Die Zeit, Le Parisien, and France24.

ORCID

Eugenio Cusumano http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7349-6639

Reference list

- Barnett, M. (2005). Humanitarianism transformed. Perspectives on Politics, 3, 723–740. doi: 10.1017/S1537592705050401

- Barnett, M. (2009). Empire of humanity. A history of humanitarianism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Barnett, M., & Weiss, T. (2008). Humanitarianism in question. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Battilana, J., & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing – insights from the study of social enterprises. Academy of Management Annals, 8, 397–441. doi:10.1080/19416520.2014.893615 doi: 10.5465/19416520.2014.893615

- Beckert, J. (2010). Institutional isomorphism revisited: Convergence and divergence in institutional change. Sociological Theory, 28(2), 150–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01369.x

- Brass, J. (2016). Allies or adversaries. NGOs and the state in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brummer, K., & Thies, C. (2012). The contested selection of national role conceptions. Foreign Policy Analysis, 11, 273–293. doi: 10.1111/fpa.12045

- Collinson, S. (2016, July). Constructive deconstruction: making sense of the international humanitarian system. HPG Working Paper. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Cooley, A., & Ron, J. (2002). The NGO scramble: Organizational insecurity and the political economy of transnational action. International Security, 27(1), 5–39. doi: 10.1162/016228802320231217

- Cusumano, E. (2015). The scope of military privatisation: Military role conceptions and contractor support in the United States and the United Kingdom. International Relations, 29, 219–241. doi: 10.1177/0047117814552142

- Cusumano, E. (2017). Emptying the sea with a spoon? Non-governmental providers of migrants’ search and rescue in the Mediterranean. Marine Policy, 75, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.10.008

- Cusumano, E. (2019). Straightjacketing migrant rescuers? The code of conduct on maritime NGOs. Mediterranean Politics, 24, 106–114. doi: 10.1080/13629395.2017.1381400

- Cusumano, E., & Gombeer, K. (2018). In deep waters: The legal humanitarian and political implications of closing Italian ports to migrant rescuers. Mediterranean Politics. doi: 10.1080/13629395.2018.1532145

- Cuttitta, P. (2017). Repoliticization through search and rescue? Humanitarian NGOs and migration management in the Central Mediterranean. Geopolitics. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1344834

- Del Valle, H. (2016). Search and rescue in the Mediterranean sea: Negotiating political differences. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 35(2), 22–40. doi: 10.1093/rsq/hdw002

- Dijstelbloem, H., van Reekum, R., & Schinkel, W. (2017). Surveillance at sea: The transactional politics of border control in the Aegean. Security Dialogue, 48, 224–240. doi: 10.1177/0967010617695714

- Di Maggio, P., & Power, W. (1983). The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective Rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48, 147–160. doi: 10.2307/2095101

- Donini, A. O. (2010). The far side: The meta functions of humanitarianism in a globalised world. Disasters, 34, S220–S237. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01155.x

- Dyson, T. (2010). Neoclassical realism and defence reform in Post-Cold War Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Garelli, G., & Tazzioli, M. (2018). The humanitarian war against migrant smugglers at sea. Antipode, 50, 685–703. doi: 10.1111/anti.12375

- George, A., & Bennett, A. (2005). Case studies and theory development in The social sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Greenwood, R., Oliver, C., Sahlin-Andersson, K., & Suddaby, R. (2013). Introduction. In R. Greenwood, K. Sahlin-Andersson, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), Sage Handbook of organizational institutionalism (2nd ed., pp. 1–43). London: Sage.

- Fearon, J., & Latin, D. (2000). Violence and the social construction of ethnic identity. International Organization, 54, 845–77. doi: 10.1162/002081800551398

- Heyse, L. (2006). Choosing the lesser evil: Understanding decision making in humanitarian Aid NGOs. London: Routledge.

- Holsti, K. (1970). National role conceptions in the study of foreign policy. International Studies Quarterly, 14, 233–309. doi: 10.2307/3013584

- Holton, L., Lewis, S. C., & Coddington, M. (2016). Interacting with audiences. Journalism Studies, 17, 849–859. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1165139

- International Organization of Migration. (2016). Missing migrants project. Retrieved from https://missingmigrants.iom.int/

- Jonsson, S. (2009). Refraining from imitation: Professional resistance and limited diffusion in a financial market. Organization Science, 20, 172–186. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1080.0370

- Kier, E. (1997). Imagining war French and British military doctrine between the wars. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Kontinen, T., & Onali, A. (2017). Strengthening institutional isomorphism in development NGOs? Program mechanisms in an Organisational Intervention. Sage Open. doi: 10.1177/2158244016688725

- Krause, M. (2014). The good project: Humanitarian relief NGOs and the fragmentation of reason. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Legro, J. (1995). Military culture and inadvertent escalation in World War II. International Security, 18(4), 108–142. doi: 10.2307/2539179

- Levy, J. (2008). Case studies: Types, designs, and logics of inference. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 25, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/07388940701860318

- Meyer, J., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83, 340–363. doi: 10.1086/226550

- Médecins sans Frontières. (2016). International financial report 2015. Retrieved from http://www.msf.org/sites/msf.org/files/msf_financial_report_2015_final_0.pdf

- Migrant Offshore Aid Station. (2016). MOAS launch 2016 Mediterranean mission with two ships, two drones patrolling the “dead zone”.

- Pallister-Wilkins, P. (2017). Humanitarian rescue/sovereign capture and the policing of possible responses to violent borders. Global Policy, 8, 19–24. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12401

- Ramanath, R. (2009). Limits to institutional isomorphism. Non-profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38, 51–76. doi: 10.1177/0899764008315181

- Rubenstein, J. C. (2015). Between Samaritans and states: The political ethics of humanitarian INGOS. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Save the Children. (2016). Our finances and annual review. Retrieved from https://www.savethechildren.net/about-us/our-finances

- Schmitt, O. (2016). French military adaptation in the Afghan War: Looking Inward or Outward? Journal of Strategic Studies. doi: 10.1080/01402390.2016.1220369

- Schneiker, A. (2015). Humanitarian NGOs, (In)security and identity. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Scott, R. W. (1995). Institutions and organisations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Scott-Smith, T. (2016). Humanitarian dilemmas in a mobile world. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 35(2), 1–21. doi: 10.1093/rsq/hdw001

- Sea-Watch. (2016). Aims. Retrieved from http://sea-watch.org/en/

- Stierl, M. (2018). A fleet of Mediterranean border humanitarians. Antipode, 50, 704–724. doi: 10.1111/anti.12320

- Stoddard, A. (2003). Humanitarian NGOs: Challenges and trends. HPG Briefing, 12. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Stroup, S. (2012). Borders among activists. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Stroup, S., & Wong, W. (2013). Come together? Different pathways to international NGO Centralization. International Studies Review, 15, 163–184. doi: 10.1111/misr.12022

- UNHCR. (2016). Refugees/migrants emergency response – Mediterranean. Retrieved from http://data.unhcr.org/mediterranean/regional.php.

- Van Reekum, R. (2016). The mediterranean: Migration corridor, border spectacle, ethical landscape. Mediterranean Politics, 21, 336–341. doi: 10.1080/13629395.2016.1145828