ABSTRACT

Informal groupings have proliferated in EU foreign policy over the past decade, despite the enhanced role of the High Representative tasked with ensuring the coherence of this policy domain under the Lisbon Treaty. This article analyzes how the decision of select EU member states to act on certain policy issues through informal groupings, bypassing the EU framework, affects the High Representative’s room for maneuver. Drawing on the principal-agent model, the emergence of informal groupings is conceptualized as a manifestation of pathological delegation, which undermines High Representative’s role. The findings reveal two factors that may nevertheless increase the agent’s discretion in cases of delegation anomalies: the low heterogeneity of member state preferences toward the informal grouping and the interaction between agents in the same domain, facilitating agent’s performance. By examining agent's discretion when delegation anomalies arise, the article may be useful for scholars investigating delegation and agency in international organizations.

Despite the fact that foreign policy is among the core state powers, resulting in the reluctance of EU members to delegate decision-making in this area to supranational institutions (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2016), the numerous crises in the EU's neighborhood during the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s (such as the wars in the Western Balkans, Darfur, and Afghanistan, and the revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine) have demonstrated the need for the increased coordination of foreign policy actions.

Against this backdrop, the Lisbon Treaty (specifically the Treaty on European Union) introduced reforms within the governance structure of the EU's foreign policymaking, further centralizing this policy area (Chamon & Govaere, Citation2020). Most of the institutional changes relate to the position of the supranational agent, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. In a nutshell, while decision-making competence remained in the hands of the member states, the High Representative was given powers within the areas of agenda-setting, policy formulation and external representation in matters related to the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and was tasked with ensuring the coherence of the EU foreign policy (Wessel, Citation2022). In addition, the European External Action Service (EEAS), which includes some 140 EU Delegations around the globe, was created to support the High Representative in executing their mandate.

Simultaneously, despite these institutional developments, differentiated cooperation has proliferated within EU foreign policy during the last decade, particularly with regard to the EU response to conflict and crisis, a part of CFSP (Amadio Viceré & Sus, Citation2023). Among its most common formats are informal groupings, via which select member states engage in joint foreign policy actions outside the EU institutional framework (Alcaro, Citation2018; Alcaro & Siddi, Citation2021; Delreux & Keukeleire, Citation2017; Rieker, Citation2021b; Siddi et al., Citation2022; Amadio Viceré, Citation2023). It means that, despite their decision to strengthen the EU's governance structures and to delegate greater powers to the High Representative, member states in certain cases prefer to act via informal groupings. At the same time, some scholars perceive these differentiated cooperation formats, despite their informality, as part of the broader EU foreign policy (Alcaro, Citation2018; Delreux & Keukeleire, Citation2017; Tocci, Citation2017), the coherence of which member states have entrusted to the High Representative. This observation serves as the point of departure for this article, which explores how the decision of some EU countries to respond to certain conflicts and crises via informal groupings, bypassing the EU framework, affects the High Representative's role.

Despite the fast-growing literature on differentiated cooperation within EU foreign policy (Amadio Viceré & Sus, Citation2023), studies investigating EU agents’ available room for maneuver when member states decide to act via such groupings remain rare (Alcaro & Siddi, Citation2021; Bassiri Tabrizi & Kienzle, Citation2020; Grevi, Citation2020). To tackle the aforementioned question, this article applies a principal-agent model and conceptualizes member states as the collective principal, the High Representative as their supranational agent, and the agent's room to maneuver as their discretion. To explain how the launch of informal groupings affects the High Representativés discretion, this study considers anomalies within the act of the delegation that deviate from the basic principal-agent model (Menz, Citation2015; Sobol, Citation2016; Thompson, Citation2007). Drawing on the concept of “pathological delegation,” defined as a situation wherein the structure of the delegation itself provides incentives for members of the collective principal to engage in individual actions of control that hinder the agent's work (Sobol, Citation2016, pp. 338–339), this study conceptualizes informal groupings as a manifestation of pathological delegation. Recognizing the limited role of the High Representative when an informal grouping is triggered, the analysis will show that two environmental factors may have an enhancing impact on the High Representative's room for maneuver, providing them with the ability to link the informal grouping's activities to the EU's overall response to a given crisis. In this way, the agent is a position to fulfil its task of ensuring coherence of EU foreign policy. These two factors are: low heterogeneity of member state preferences toward the grouping and interactions between agents in the same policy domain that facilitate High Representative's performance. Furthermore, the agent itself, by embracing its inter-institutional position and using the broad mandate provided by the Lisbon Treaty, can also enhance its discretion with regard the examined occurrences of differentiated cooperation.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: the first part introduces the principal-agent model and applies it to the conceptualization of the informal groupings in the EU's response to conflict and crisis. Next, the article proposes a conceptual framework to explore how the scope of conditions for pathological delegation affect the agent´s discretion and introduces variables to explore the High Representative's room for maneuver in such cases. The article then moves on to the empirical evidence. Based on two case studies, the Contact Group on Libya (launched in 2011) and the Normandy Format (launched in 2014), it examines whether the scope conditions conducive to pathological delegation were present, and analyses which factors affected agent discretion in each case. The conclusion discusses the usefulness of conceptualizing informal groupings as a manifestation of pathological delegation for the study of agent's discretion and the value added this study offers to the scholarship on delegation and discretion patterns in international organizations (IOs).

The article reviews the secondary sources on delegation and supranational agency in IOs and engages in a systematic review of relevant primary sources produced by EU institutions (focusing on meeting documents such as agendas, conclusions, and decisions). In addition, five in-depth interviews were conducted with national and EU diplomats who observed the functioning of the informal groups explored in this article.

This article speaks to the micro level of analysis of differentiated cooperation (Amadio Viceré & Sus, Citation2023), by understanding its supply as the result of delegation complexities that arise from the institutional aspects of EU foreign policymaking. Moreover, by providing insights into the conditions for and implications of the “principal's pathological behavior” for the agent's discretion (Sobol, Citation2016, p. 335), this study is relevant to scholars interested in decision-making processes within various institutional settings, such as collective delegation from states to IO Secretariats, where delegation problems continue to be highly relevant (Dijkzeul & Salomons, Citation2021; Patz & Goetz, Citation2019). As pointed out by scholars, the ineffectiveness of IOs can arise not only from agency problems, but also from “principal problems” (Thompson, Citation2007) that affect the agent's discretion by hindering its work. Drawing on the literature on delegation problems arising from the collective nature of the principal and features of the principal-agent contracts in the UN (Thompson, Citation2007), World Bank (Gutner, Citation2005). and WTO (Elsig, Citation2011), this article proposes a conceptual framework for exploring the agent´s discretion when delegation anomalies arise. It can be applied to investigate the discretion of IO Secretariats in carrying out their tasks, contributing to a better understanding of the performance of this type of organization.

The principal-agent model and its application to informal differentiated cooperation

To explain how the decision of some EU member states to act via informal groupings in certain cases determines the agent's discretion, this study applies the principal-agent model. This section first briefly introduces the key concepts of this theoretical lens, and then it applies them to the conceptualization of informal groupings in the EU's response to conflict and crisis, where these differentiated cooperation occurrences are most prevalent.

Key concepts of the principal-agent model

At the basic level, a principal-agent relationship occurs “when one party, the principal, enters into a contractual agreement with a second party, the agent, and delegates to the latter the responsibility for carrying out a function or set of tasks on the principal's behalf” (Kassim & Menon, Citation2003, p. 122). We can thus distinguish between individual principals, multiple principals—several principals with separate contracts with the same agent (Dür & Elsig, Citation2011)—and collective principals, namely principals “composed of more than one actor” who make decisions jointly (Nielson & Tierney, Citation2003, p. 247), and maintain a single contract with the agent. Principals delegate tasks to their agents to minimize transaction costs, to counter policymaking instability, or to improve policy effectiveness (Kassim & Menon, Citation2003; Niemann & Huigens, Citation2011; Pollack, Citation2003). The contract via which a principal delegates authority specifies the conditions under which the agent is allowed to act. In other words, while acting on behalf of the principal, agents enjoy a certain amount of discretion, which can be defined as “the room for maneuver the agent has in carrying out the delegated authority” (Delreux & Adriaensen, Citation2018, p. 267). The principal-agent model furthermore assumes that principals are able to control their agents in order to prevent agency losses—a situation wherein agents undermine their principals and pursue their own interests. To make sure that agents act in accordance with the interests of the principal, principals apply various ex ante and ex post control mechanisms (da Conceição-Heldt, Citation2011; Nielson & Tierney, Citation2003; Pollack, Citation1997, Citation2003). The former include administrative oversight through agency design, legal instruments, and procedures, whereas the latter encompass the monitoring or sanctioning of agents.

Within this outline of the principal–agent model, two elements which underpin the analysis require closer attention: the politics of delegation and the politics of discretion. At the heart of the politics of delegation lies the act of delegation itself, which regulates what specific competencies principals delegate to their agents. It can differ in terms of its formality, with the most formalized delegation occurring through legal means. As such, the delegation can also take on different forms, including two-stage delegation, which takes place by means of macro- and micro-delegation. The former is usually established via legal arrangements and provides general provisions for the agent to act upon, whereas the latter regulates agent's room for maneuver in particular cases (e.g. Dür & Elsig, Citation2011, p. 331). Moreover, as mentioned above, decisions to delegate can be motivated by various demands, with the quest for improved effectiveness as one of the most prominent ones. Simultaneously however, as Moravcsik (Citation1993) has noted, for certain politically sensitive issues, the relationship between the functional demands for delegation and larger concerns about national sovereignty can lead to delegation problems. Researchers have identified various delegation anomalies that deviate from the basic principal-agent model. Most often they involve collective principals, such as EU member states delegating to the European Commission (Menz, Citation2015; Sobol, Citation2016) or members of the UN Security Council delegating to the UN Special Commission (Thompson, Citation2007). Among concepts that describe such delegation anomalies are: non-exclusive delegation (Dijkstra, Citation2017), principal slippage (Menz, Citation2015), principal subversion (Thompson, Citation2007), antinomic delegation (Gutner, Citation2005), and pathological delegation (Sobol, Citation2016).

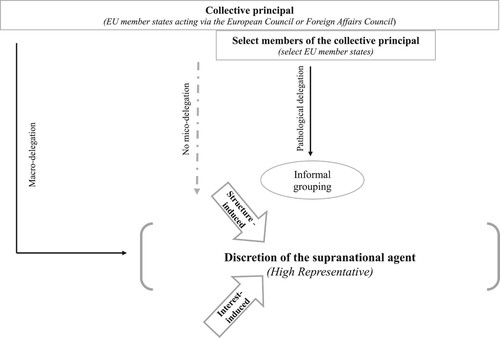

Conversely, the politics of discretion focuses on the room for maneuver the agent has in carrying out the delegated tasks. As scholars have observed, an “agent's discretion partly depends on how the principal acts and partly on how the agent plays the game” (Delreux & Adriaensen, Citation2018, p. 267). It indicates the presence of two facets of discretion: a “structure-induced” factor that for the most part stems from the external environment of the agent and an “interest-induced” factor which is the outcome of an agent's intentional actions to enhance their room for maneuver (Plank & Niemann, Citation2017; see also Delreux, Citation2010 and Helwig, Citation2014). With regard to the latter, agents can deliberately use certain strategies to expand their discretion (Hawkins & Jacoby, Citation2006). At the same time, an agent's ability to successfully pursue their own agenda can lead to agency slack, which is when an independent action undertaken by the agent is undesired by the principals (see also: da Conceição-Heldt, Citation2017). However, agency slack is only possible if both the agent has sufficient resources to act on their own and the principal's control mechanisms allow for this situation to occur (Tallberg, Citation2002, p. 29).

The principal-agent lens and informal groupings in EU's response to conflict and crisis

This article conceptualizes the member states acting via the European Council and the Foreign Affairs Council as the collective principal and the High Representative as their agent. The focus on the office of the High Representative is justified by its inter-institutional locus and its broad legal mandate regarding agenda-setting, policy formulation and external representation (Art 18, 21, 22, 27, 38, 42 TEU) that makes its officeholder responsible for the coordination of all EU foreign policy activities and for ensuring its coherence.Footnote1 This particular legal position makes it reasonable to assume that it is in the agent's interest to be involved in the functioning of informal groupings launched as a response to conflict and crisis, as they constitute a component of the EU foreign policy (Alcaro, Citation2018; Delreux & Keukeleire, Citation2017).

Furthermore, the delegation of authority from the principal to the agent in EU foreign policy follows the two-stage model mentioned above. The provisions of the Lisbon Treaty constitute macro-delegation, wherein certain powers are delegated from the principal to the agent, providing the institutional basis for the High Representative to act. Micro-delegation is then effected through a decision by the member states, in which the European Council or the Foreign Affairs Council give the High Representative a mandate to act on a specific matter (see also: Pollack, Citation2017). The agent's constant need to obtain a mandate from the principal to act on specific issues constitutes the major control mechanism in this dyad (da Conceição-Heldt, Citation2017, p. 208). In light of this two-step delegation, this article thus argues that informal groupings emerge when certain members of the collective principal choose not to delegate a specific task through micro-delegation to the agent, but instead trigger forms of intergovernmental cooperation outside the EU framework. At the same time, however, the agent still has certain powers and responsibilities delegated to it through macro-delegation. To explain how the launch of informal groupings affects the High Representative's discretion, this study, therefore, turns to the anomalies of delegation.

Among the previously mentioned models of such delegation, the concept of “pathological delegation” developed by Sobol (Citation2016) best captures the dynamics visible in the EU's response to conflict and crisis. He defined pathological delegation as a situation wherein the structure of the delegation itself and the features of the principal-agent contract provide incentives for certain actors within the collective principal to engage in individual actions of control that undermine the collective delegation effort as well as hinder the agent's work (pp. 338–339). Drawing on Sobol’s (Citation2016) concept and assuming that informal groupings are manifestations of pathological delegation, the section proposes a conceptual framework for exploring the agent's discretion in cases of pathological delegation.

The agent's discretion in cases of pathological delegation: Conceptual considerations

The article argues that, due to the design of the specific principal-agent contract between the member states and the agent, the discretion of the latter is affected when pathological delegation occurs and informal groupings are launched. Therefore, this section first investigates the scope conditions that make the examined principal-agent dyad prone to pathological delegation and then moves on to explore the specific variables that might affect the High Representative's room for maneuver in the case of informal groupings.

Scope conditions for pathological delegation in EU foreign policy

We can distinguish three conditions that make the principal-agent relationship prone to pathological delegation: the structure of the delegation act, an ill-designed contract, and the (geo)political salience of the issue at stake. The following paragraphs discuss these conditions and explore the extent to which they are met in the principal–agent relationship between the member states and the High Representative.

The first scope condition concerns the structure of the delegation act. The scholarship distinguishes two major characteristics of the collective principal that make it more prone to pathological patterns. The first feature, heterogeneity, stems from the reality of joint delegation. The collective principal, composed of several actors, must first solve a collective–action problem in order to decide what to delegate to the agent. The higher the number of actors involved within a collective principal, the more difficult the decision-making, especially if delegation's decision must be unanimous (Nielson & Tierney, Citation2003; Tallberg, Citation2002). Since the individual actors within the principal tend to vary greatly by size, economic strength, national identity and the like, such a principal is likely to be characterized by a heterogeneity that impacts its ability to delegate (see also: Reykers & Smeets, Citation2015). Heterogeneity can hinder delegation in two ways: The collective principal cannot agree on a joint policy direction and thus the delegation cannot occur; or the collective principal reaches a decision but individual members of the principal have divergent opinions as to whether it is beneficial for them to delegate the implementation of a given task to the agent (see also: Mügge, Citation2011). Under these conditions, disagreements among the collective principal can lead to individual members of the principal acting on their own (Menz, Citation2015, p. 318). The second feature of the collective principal that can further complicate the delegation is the power asymmetries among its members, which might also increase preference heterogeneity. As the literature demonstrates, asymmetries can provide particularly powerful members of the principal with instruments of individual control over the collective principal's actions and the agent they delegate to (Delreux & Adriaensen, Citation2017a, p. 16; Thompson, Citation2007, pp. 10–11).

Turning to the specific principal–agent relationship at the center of this article, the literature offers rich empirical evidence for the pathological-prone structure of the European Council's and Foreign Affairs Council's delegation to the High Representative. The 27 EU member states account for a highly complex and diverse collective principal characterized by a distinct heterogeneity of preferences in terms of foreign policy issues due to different geopolitical exposures, strategic cultures, and interests (see also: Schimmelfennig, Citation2019). In light of the unanimity required within decision-making procedures in the EÚs response to conflict and crisis, these differences are likely to hinder delegation. In addition, EU countries vary considerably in size and economic strength, which affects their political weight and results in power asymmetries within the principal. Although unanimity in decision-making can be perceived as a factor that limits the significance of such asymmetries, empirical evidence suggests that more powerful member states do leverage weaker states and persuade them to support their positions (Rieker, Citation2021a; Tömmel & Verdun, Citation2017). Furthermore, the delegation of authority from the principal to the agent takes place in a two-stage process. As presented in the previous section, the macro-delegation via the Lisbon Treaty gives the High Representative a distinctive role to play, yet their specific responsibilities remain ambiguous (Helwig & Rüger, Citation2014; Howorth, Citation2011). Thus, the micro-delegation that stems from providing the agent with an explicit mandate to act on a particular issue remains central to the agent's discretion. Moreover, the second step of the delegation may be hampered by the effects of the aforementioned characteristics of the collective principal. The literature offers numerous examples of how preference heterogeneity and power asymmetries among the 27 member states complicate the act of micro-delegation, leading to pathologies of delegation (Helwig, Citation2014, Citation2017; Koenig, Citation2014) and thus limiting the High Representative's discretion.

The second scope condition addresses the issue of an ill-designed contract between the principal and the agent. We can distinguish two characteristics of a contract that make a specific principal–agent relationship prone to pathological delegation: the distribution of resources between the principal and the agent, and the definition of the tasks for the agent to perform. The literature notes that when principals do not provide the agent with sufficient resources to perform the delegated tasks, pathological delegation is likely to occur (Sobol, Citation2016, pp. 342–343; see also: Pollack, Citation1997). Additionally, the principal's control over resources might be applied to “undermine the performance of well-meaning agents already engaged in productive behavior” (Thompson, Citation2007, p. 10). In terms of the definition of tasks, Gutner points to the possibility of pathological delegation when “delegation consists of conflicting or complex tasks that are difficult to institutionalize and implement” (Citation2005, p. 11).

There is ample evidence for both manifestations of an ill-designed contract in the case of the examined principal-agent dyad. Researchers observe a “contradiction between supranational leadership tasks for the High Representative on one hand and the unvaryingly intergovernmental control of resources on the other” (Major & Bail, Citation2011, p. 28), emphasizing the limited resources the agent has. On the one hand, the legal framework equips the High Representative with agenda-setting powers, policy formulation and external representation, as well as with coordination of CFSP and with providing the coherence of the overall EU foreign policy. On the other, the Lisbon Treaty makes the agent dependent upon the support of the principal which maintains both decision-making and budgetary authority. The agent is responsible for leading the response to conflict and crisis on the EU's behalf yet does not have the authority to enforce the compliance and cooperation of member states in this matter (Helwig, Citation2014, pp. 117–118). Regarding the definition of tasks to be performed by the High Representative, scholars argue that the Lisbon Treaty gave the agent “quite an extensive list of duties” (Wessel, Citation2022) and that the “concentration of responsibilities in a single post generates a huge and relentless workload for one person” (EEAS, Citation2013, p. 13). While a unique mix of competencies is essential for the position (Mogherini, Citation2020), the fact remains that the role is institutionally complex and encompasses a multitude of responsibilities (Amadio Vicere & Fabbrini, Citation2017; Blockmans & Hillion, Citation2013; Helwig, Citation2014). Combined with the limited resources at the agent's disposal, it makes the principal-agent relationship prone to pathological delegation.

Finally, while the two previous conditions for pathological delegation refer to features of the principal–agent contract, the third scope condition considers the policy area in which the delegation takes place and relates to the (geo)political salience of the issue at stake. Sobol argues that for issues of major political salience, members of the principal may be more prone to act independently, thus undermining the activities of both the collective principal and the agent (Citation2016, p. 347). This observation is shared by Menz (Citation2015), who claims that in the case of politically sensitive issues, preference heterogeneity is particularly evident, as it increases the inability of the collective principal to agree on a decision, thereby causing individual principals to break rank (p. 318). As stated in the introduction, EU foreign policy, and especially the EU's response to crisis and conflicts, belongs to the core state powers and is characterized by a high level of political importance and sensitivity, making it prone to pathological delegation.

Overall, the three scope conditions for pathological delegation seem to fall on fertile ground in the case of the principal–agent contract between the member states and the High Representative and their occurrence affects the discretion of the latter. By exploring the institutional complexities arising from the contract and of the agent's own performance, the next section introduces specific variables that affect the High Representative's room for maneuver in the case of informal groupings.

Discretion affecting-factors of a supranational agent in EU foreign policy

Assuming that select members of the collective principal engage in intergovernmental cooperation, undermining collective delegation and hindering the agent's work, pathological delegation clearly implies that the agent's discretion is limited from the outset. However, by increasing the competencies of the High Representative in terms of agenda-setting, policy formulation and external representation, the Lisbon Treaty also made the High Representative responsible for the coherence of overall EU foreign policy, including the EÚs response to conflict and crisis. Against this backdrop, this article follows an explorative approach and investigates factors that determine the High Representative‘s discretion in relation to informal groupings. In doing so, it draws on the discretion-affecting variables identified with regard to supranational agents in IOs (Delreux & Adriaensen, Citation2018; Elsig, Citation2010; Niemann & Huigens, Citation2011; Plank & Niemann, Citation2017). This section maintains the aforementioned definition of discretion, distinguishing between two facets of discretion, structure– and interest–induced (Plank & Niemann, Citation2017).

Among the explanatory factors for structure–induced discretion, which results from the environment the agent operates in, six determinants can be distinguished. Following the theoretical assumptions of the principal-agent model, the main determinants of structure–induced discretion stem from the act of delegation that determine the control mechanism in a specific principal–agent relationship (Tallberg, Citation2002, pp. 28–29). In terms of the delegation by member states via the European Council or the Foreign Affairs Council to the High Representative, the discretion of the agent is constrained by the heterogeneity within the collective principal, the two-step delegation (which limits the amount of delegated authority, keeping the agent under the strict control of the principal), and the limited resources at the High Representative's disposal. It remains to be explored however, how the level of preference heterogeneity among members of the collective principal regarding the specific issue addressed by the informal groupings affect the agent's discretion (see also: da Conceição-Heldt, Citation2017).

Furthermore, the agent's discretion can be affected by the agent's information benefit, stemming from an agent's potential information surplus gained through the institutional memory of the environment in which the agent is embedded (Hawkins & Jacoby, Citation2006). In the case of the High Representative, an information benefit could come from the support of the EEAS and the resources that are at the High Representative's disposal in their role as the European Commission's Vice-President.

Also, as scholars have observed, the degree of preference overlap between the principal and the agent can also impact the agent's discretion (Dür & Elsig, Citation2011). With regard to the High Representative, member states decide to delegate certain tasks via micro-delegation to the agent when they are convinced of the preference overlap. It can thus enhance the agent's discretion. Next, a degree of urgency surrounding the policy issue at stake has been identified as a factor affecting an agent's discretion (Plank & Niemann, Citation2017, p. 142). The agent's discretion can increase if they are able to act swiftly on behalf of the principal in a crisis situation.

Related to the degree of urgency, the context of the policymaking is another possible determinant of an agent's discretion (Delreux, Citation2010), which includes aspects such as the participation of third parties and the context of the negotiations that can either enhance or limit an agent's discretion, depending on the context. Finally, an agent's discretion can be affected by the interaction between agents acting in the same arena. As Helwig (Citation2017a, p. 109–110) has argued, the behavior of one agent can have a significant impact on another agent's ability to exert influence on policies, thereby limiting or enhancing their individual discretion. This factor might be relevant for the High Representative, since there is a second agent of the member states working in the field of EU external action—the European Commission. It thus remains to be seen whether the interaction between the High Representative and the Commission plays a role in terms of informal groupings.

Conversely, an agent's interest-induced discretion, understood as an outcome of the agent's intentionally pursued action to enhance their room for maneuver, involves agent-related sources. Here, two factors stand out, and both can be interpreted as entrepreneurial strategies used by agents to exert their influence (Sus, Citation2021). The first is the strategic use of agenda-setting power. Tallberg (Citation2003, p. 8) perceived the possibility wherein an agent structures the agenda as “the true ‘power of the chair’ and a revenant form of political influence.” Since the High Representative sets the agenda and chairs the Foreign Affairs Council meetings, it might be a relevant factor affecting their discretion. The second factor results from a broad interpretation of the agent's own mandate. Instead of strictly sticking to their job description, an agent can actively pursue ways through which they can be more influential, namely during negotiations with third parties (Delreux, Citation2010; Elsig, Citation2007). With regard to the High Representative, due to the ambiguity of this position, scholars have pointed to different possible interpretations of the mandate, depending on the officeholder in question (Howorth, Citation2011, pp. 307–308). The following figure summarizes the conceptual underpinnings of the paper introduced above (see ).

The figure demonstrates a framework for investigating the agent's discretion in cases of pathological delegation. Informal groupings occur when the collective principal does not decide to give the agent a specific mandate to act but instead select members of the principal act outside of the EU framework. This affects the discretion of the agent, that despite not obtaining the specific mandate (micro-delegation), is still empowered by the principal to act according to the provisions of the Lisbon Treaty (macro-delegation). An exploration of the institutional complexities arising from the principal–agent contract (structure–induced discretion) and of the agent's own performance (interest–induced discretion) sheds light on the agent's room for maneuver in the case of informal groupings.

Informal groupings and the discretion of the High Representative: Case studies

Moving from the conceptual underpinnings, the article turns to its empirical research. The two case studies, the Contact Group on Libya (launched in 2011), and the Normandy Format (launched in 2014), show that while agent's discretion is limited when informal groupings are launched, there are environmental factors that might positively impact agent's discretion and enable them to link the grouping's actions to the overall EU response to a given crisis. Also, the agent itself is able to increase its room for maneuver by pursuing a broad interpretation of its own mandate.

Three aspects played a role in the criteria for the case study selection. First, as the article conceptualizes informal groupings as a manifestation of pathological delegation and seeks to explore the agent's discretion in such cases, the set of possible cases was limited to formats where no micro-delegation to the agent took place. Informal groupings into which member states decided to formally integrate the High Representative via some form of micro-delegation were outside the scope of this study such as the E3+3 group (France, Germany, the United Kingdom, China, Russia, and the United States) launched to negotiate an agreement concerning Iran's nuclear program (Alcaro, Citation2018). Second, as the article focuses on the discretion of the High Representative, whose position was strengthened by the Lisbon Treaty, the set of potential cases did not encompass those groupings established before 2009, such as the Contact Group on Somalia, the Balkan Contact Group, or the Contact Group on Afghanistan (Grevi et al., Citation2020; Keukeleire, Citation2006). Finally, to provide the most comprehensive insights possible, the cases had to differ in terms of the presence of the scope conditions such as the level of preference heterogeneity within the principal, and the discretion-affecting factors such as the policymaking context, the interaction between agents in the same field, and the High Representative officeholder. Among the five occurrences of differentiated cooperation that met the three criteria were the Libya Contact Group, Normandy Format, Friends of Syria, the Berlin Process, and the Anglo-German Initiative for Bosnia–Herzegovina (Siddi et al., Citation2022; Amadio Viceré, Citation2023). The first two initiatives met the three criteria to the greatest extent and were therefore selected as case studies.

The analysis of the case studies sheds light on how the decision of some EU countries to respond to certain conflicts and crises via informal groupings, affects the High Representative's room for maneuver. To answer this question, each case study begins by analyzing the occurrence of the scope conditions for pathological delegation (the structure of the delegation act, an ill-designed contract, the (geo) political salience of the issue) and then explores the determinants of the agent's discretion in relation to the grouping.

The Franco-British initiative and the Contact Group on Libya

The Contact Group on Libya, a multinational and multi-organizational endeavor formed by 21 countries as well as several IOs, was launched on the initiative of the United Kingdom in March 2011. At the time, Libya was in the midst of a civil war following an uprising against Muammar Gaddafi's rule, to which the regime responded with mass repression and violence. Immediately after the war broke out, Catherine Ashton, then the newly appointed High Representative, issued a declaration on the EU's behalf, condemning the violence committed by Gaddafi's regime (European Union, Citation2011). While the initial EU response was mostly focused on humanitarian assistance and sanctions, more was needed to end the violence. The war soon developed into the “most serious crisis in the neighborhood since the Balkan wars of the 1990s” (Brattberg, Citation2011, p. 1). The high (geo) political salience of this crisis resulted in growing pressure on member states to act. At the same time, the preference heterogeneity within the principal in terms of an adequate response became evident (interviews 3, 5). The major point of conflict was the support (or lack thereof) for a military intervention against the regime (Koenig, Citation2011, pp. 10–13; Marchi, Citation2017, pp. 3–6). Certain members of the principal were in favor of a large-scale military operation (Italy and France), some were only willing to support it if there was a UN Security Council mandate in place (Sweden and Ireland), and others were against it (Germany) (Lamoreaux, Citation2019; interviews 3, 5). This heterogeneity of preferences made any joint decision by the principal impossible, leaving the agent without a specific mandate to act. Furthermore, the agent was sidelined by France and the United Kingdom, which perceived Ashton's engagement in formulating an EU response as overstepping her mandate and thus instructed her “not to interfere in the military decision-making” (Watt, Citation2011; Marchi, Citation2017, p. 6). Conversely, other members of the principal criticized her lack of ambition and leadership (Traynor, Citation2011). The poor relationship between the agent and the principal resulted in a rejection of her request to increase the funding for the EEAS, which further limited her resources (Traynor, Citation2011). Disappointed by the EU's “powerlessness” and inability to act, France and the United Kingdom soon joined a U.S.-led coalition to launch military strikes against Libya (Koenig, Citation2014, p. 262; Obama et al., Citation2011).Footnote2 Moreover, the Franco-British duo exploited their diplomatic power over other members of the principal and established a Contact Group outside the EU framework (Fabbrini, Citation2014, p. 196). In short, all three conditions favorable for pathological delegation were present and contributed to the emergence of the Contact Group. Under the political leadership of France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, the group met three times (in April, May, and August 2011) (IISS Strategic Comment, Citation2011).

In terms of the agent's structure–induced discretion with regard to the Contact Group, it is evident that the heterogeneity of preferences among the members of the principal negatively affected the High Representative's discretion. French and British leaders emphasized, when referring to their actions within the informal group, that “Europe is now fully on board with this mission” (Cabinet Office, Citation2011) and portrayed it as a “European effort” (Obama et al., Citation2011). The establishment of the Contact Group was “welcomed” by the Council as part of the international effort to solve the Libyan crisis (Council of the European Union, Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2011c), yet its activities were not embedded in the EU framework. It was thus perceived instead as a situation in which “European countries are in the lead, but Europe is not” (Biscop, Citation2011, p. 4), with other member states describing the Franco-British initiative as a “directoire” (Fabbrini, Citation2014, p. 191). The low level of support for the Group within the principal limited the agent's discretion, as she was “trapped between warring capitals” (Vaisse & Kundnani, Citation2011, april). Additionally, the degree of preference overlap between the principal and the agent further limited Ashton's discretion, since she was critical of any military engagement by EU countries (Ashton, Citation2011; interview 5). Consequently, this divergence between her stance and those of the more powerful members of the principal, such as France or Italy, sidelined her from the outset (Fabbrini, Citation2014, interview 5).

With regard to the information benefit that could enhance an agent's discretion, there was none in this case. The inter-institutional office of the High Representative was new to the EU governance structure, as Ashton was the first High Representative under the Lisbon Treaty—as was the EEAS, which she was building up. Her opportunities to reach out for expertise were thus limited (Brattberg, Citation2011; Fabbrini, Citation2014), as was her own experience in external affairs (Howorth, Citation2011, pp. 306–307). Closely related to the information benefit, the interaction between agents in the same field did not enhance Ashton's discretion in terms of the functioning of the Contact Group. The transformed office of the High Representative and the EEAS were new to EU foreign policymaking, resulting in inter-institutional struggles over the division of competencies, especially with the European Commission (King, Citation2015; Spence, Citation2012). Relations were particularly strained between Ashton and the Directorate General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, which was responsible for humanitarian aid to Libya. Hence, Ashton's role in coordinating the overall EU response was limited (interview 5). Against this backdrop, the crisis's degree of urgency did not work in her favor either. Due to the many constraints on her discretion in shaping the response to the Libyan war, she was not able to engage in swift action. In turn, the picture is mixed in terms of the policymaking context. She participated in all meetings of the informal grouping (EU Delegation to Turkey, Citation2011; European Commission, Citation2011; interviews 3, 5), and her involvement was linked to the shape of the format. The grouping included representatives of IOs. Since the High Representative was tasked by the Council with coordinating crisis management between the EU and its partners (Council of the European Union, Citation2011a), she managed activities between the EU and the Contact Group. Yet, despite her formal participation, her role in handling the crisis was described as deferential to the leadership of France and the United Kingdom (Marchi, Citation2017, p. 7).

In terms of the first factor affecting the interest–induced discretion, the strategic use of agenda-setting power, Ashton's attempts to use her agenda-setting power ended in the above-described conflict with the members of the principal. The agent, recognizing her limited discretion within the CFSP due to the preference heterogeneity within the principal, focused on diplomatic endeavors such as the opening of an EU office in Libya under the auspices of the EEAS (Koenig, Citation2014; Stavridis, Citation2014; interview 3). Regarding the broad interpretation of her own mandate, the evidence points to the contrary. As she herself claimed, she saw her role instead as a coordinator who looks for a political common denominator among member states (Ashton, Citation2009, Citation2011), which is indeed how she acted during the war in Libya (IISS Strategic Comment, Citation2011). Moreover, the fact that she was uninterested in the military dimension of EU foreign policymaking (interviews 3, 5) and her conflict with the European Commission, did not enhance her role in coordinating the overall EU response.

The Franco-German duo within the Normandy Format

The Normandy Format was launched in June 2014 by Berlin and Paris, together with Moscow and Kyiv, to deescalate the conflict in the Donbas region. The Russian annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and Russian-backed conflict in the Donbas disrupted European security, and were considered matters of great geopolitical importance (see e.g., Haukkala, Citation2016). Russia's aggression was condemned by the principal, which responded by adopting a series of restrictive measures that have been expanded over time (European Council, Citation2022). Despite the long-standing preference heterogeneity among members of the collective principal in terms of their stance on Russia (Alcaro & Siddi, Citation2021; Sus, Citation2018; interviews 1, 2, 4), the aggression in Ukraine acted as a catalyst for greater unity (Schmidt-Felzmann, Citation2014): the principal reacted swiftly and imposed sanctions. It soon became clear, however, that the restrictive measures would not bring an end to the conflict. In response, differences within the principal started to re-appear, with Poland, the Baltic states, and Sweden in favor of more severe sanctions, and Italy, Cyprus, and Hungary remaining reluctant (Speck, Citation2016).

Yet, despite the growing fear of the costs of sanctions in many EU countries, the principal managed to maintain unanimity. At the same time, in April 2014, diplomatic efforts to deescalate the conflict were instigated by the so-called Geneva Group, consisting of the foreign ministers of Russia, Ukraine, and the United States, and (then-still) High Representative Ashton, but without success (Åtland, Citation2020). This, combined with the ineffectiveness of sanctions in the short term showed that “the EU had no real influence over Russia” with the instruments under its control (Schmidt-Felzmann, Citation2014, p. 52). Against this backdrop, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande decided to launch an informal grouping to facilitate negotiations between Ukraine and Russia (Alcaro & Siddi, Citation2021, p. 156; Tanner, Citation2015, p. 226). In conclusion, the conditions for pathological delegation were present, yet the picture is different than in case of the Contact Group on Libya. Russian aggression was of great (geo) political significance for EU member states, and advanced preference unity within the principal to the extent that the principal was able to adopt sanctions. The introduction of sanctions by the principal was based on a proposal by the High Representative (developed together with the Commission), so a form of micro-delegation to coordinate sanctions was present (e.g., European Council, Citation2014). However, sanctions, with their long-term effect, did not deescalate the conflict, and the EU was not capable of other effective diplomatic action in this regard (see also: Fischer, Citation2019). Hence, the launch of the informal grouping can be attributed less to the principal's preference heterogeneity, than the recognition by the members of the principal of their limited capacity to act within the EU framework. It can also be argued, that the ill-designed contract between the member states and the agent contributed to the EU's limited capacity, as the “High Representative has neither the powers nor the resources” to push for a powerful response (Schmidt-Felzmann, Citation2014, p. 53; interviews 1, 3, 4; see also: da Conceição-Heldt, Citation2017, p. 206). It was also one of the reasons why the High Representative was not invited to the negotiations. The agent was seen as playing an “important, albeit predominantly technical, role” (Suslov, Citation2015), and thus her presence would have been “not really decisive on the course of negotiations” (Litra et al., Citation2017, pp. 24–25).

Turning to the structure–induced discretion of the agent and focusing on Federica Mogherini, who served as High Representative from 2014 to 2019, there is empirical evidence that the aforementioned relatively low preference heterogeneity within the principal regarding Russia and the emergence of the grouping contributed to the High Representative's discretion. Despite initial criticism by some members of the principal regarding the exclusivity of the format (de Galbert, Citation2015; Litra et al., Citation2017; Sus, Citation2018), with time, the acceptance for this grouping grew (Siddi, Citation2018; interviews 1, 2). The Franco-German duo kept the other members of the principal and the agent informed on the progress of the negotiations (Council of the European Union, Citation2015; Mogherini, Citation2015c; Pomorska & Vanhoonacker, Citation2016; Siddi et al., Citation2022). The Chancellor's Office played a major role here. Christoph Heusgen, who managed the work within the Normandy Format, was former director of the policy unit under Javier Solana, the High Representative between 1999 and 2009 and he considered coordination at the EU level to be essential (Strack, Citation2022; interview 1). Moreover, the implementation of the Minsk agreements, which were facilitated by the Normandy Format and sought to end the war in the Donbas region (Åtland, Citation2020, pp. 122–123), was conditional to lifting EU sanctions. France and Germany therefore needed the backing of the EU institutions (Siddi et al., Citation2022, p. 12). The consistency between the Franco-German efforts and the policy adopted by the principal would have been impossible had there been a strong preference heterogeneity regarding Russia. In turn, the anchoring of the Normandy Format in the EU framework worked to favor the agent's discretion. In line with the macro-delegation via the Lisbon Treaty, she coordinated the overall EU response and was able to emphasize the coherence between the EU and the activities of the Franco-German duo (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, Citation2017; Mogherini, Citation2015b).

Conversely, the degree of preference overlap between the principal and the agent offers a more mixed picture. On one hand, due to a non-paper on Russia that then-High Representative Mogherini published in January 2015 (Citation2015a), certain members of the principal criticized her underestimation of the Russian threat (Raik, Citation2015; Liik, Citation2015; interview 4). On the other hand, she subsequently expressed her unconditional support for sanctions and pointed to a preference overlap with the principal (Mogherini, Citation2015b). In turn, the interaction between agents in the same field enhanced her discretion. Since the EEAS was fully operational and the working arrangements between the diplomatic service and the Commission were in place, Mogherini could reach out for expertise, including with regard to the development of the sanctions. Furthermore, she could better embrace her role as vice-president of the Commission, which helped her to coordinate the overall EU response. At the same time, there was no information benefit on her side. Once she was appointed to the office of High Representative, the Normandy Format was already in place, without the agent's involvement. In addition, due to their long-standing relations with Russian, German, and French diplomats have access to a greater depth of expertise than their EU colleagues. The crisis's degree of urgency also did not play a significant role in the agent's discretion. The negotiations within the Normandy Format were a long–term endeavor, and there was no room for swift reactions by the agent. Moreover, as already indicated, the role of the agent was mainly focused on the coordination of restrictive measures, and, as such, her actions were linked to member stateś decisions.

Finally, with regard to the policymaking context, two aspects stand out. First, the role of the third party—Russia—proved to be important. As demonstrated, Moscow preferred to deal with the leaders of the two powerful members of the principal, instead of an agent with limited resources (Socor, Citation2015; interview 4). Reportedly, Moscow would not have accepted negotiations with an EU official (Alcaro & Siddi, Citation2021, p. 157). Second, the level of the negotiations mattered. The informal grouping was set up at the level of heads of state, and despite consultations among foreign ministers, state secretaries and advisers (Tanner, Citation2015, p. 246), it only involved state actors. The High Representative, as an EU official, did not fit in.

Moving on to the factors affecting interest–induced discretion, there is no empirical evidence for Mogherini's strategic use of her agenda–setting power. Apart from one attempt to propose tools to monitor the Minsk II agreements, which was not picked up by the Council, the agent did not use her right to propose policy action (Euractiv, Citation2015). Regarding the broad interpretation of her own mandate, Mogherini made use of her roles as chair of the Foreign Affairs Council and as the Commission's vice–president to enhance her discretion. As demonstrated above, she coordinated sanctions and was also actively engaged in putting the Ukraine–EU Association Agreement into effect. In sum, Mogherini actively embraced her role in coordinating the overall EU response. She recognized the added value of the Normandy Format and pledged to take all appropriate measures to ensure the implementation of the Minsk agreements (Council of the European Union, Citation2018; EEAS, Citation2015; Mogherini, Citation2015b). Thus, as scholars have argued, “even if High RepreSentative Mogherini is not at the negotiation table, she has an important role in shaping the EU position on Ukraine within the European institutions” (Litra et al., Citation2017, p. 23).

Discussion

In both cases, empirical evidence for the occurrence of the conditions for pathological delegation was found. However, the case studies show differences concerning the implications of the structure of the delegation's action and the ill-designed contract on the agent's discretion. The formation of the Contact Group was mainly due to the high preference heterogeneity within the principal, which prevented it from making joint decisions. This goes in line with the assumption that the demand for differentiated integration in the EU stems from the need to overcome negotiation deadlock caused by the heterogeneity of preferences, dependencies, and capacities among the member states (Schimmelfennig, Citation2019). Furthermore, the distribution of resources within the principal-agent dyad, and the control mechanisms used by the members of the principal to control the agent, meant that the latter was sidelined from the start and could not effectively contribute to an effective EU response. In turn, France and Germany's decision to launch the Normandy Format was a result of the Union's inability to take effective diplomatic action. The informal grouping was better suited to mediate the negotiations. This may be attributed to several reasons, such as the protracted processes of decision-making in the EU, due to the unanimity rule and institutional complexity, or Russia's reluctance to negotiate with the EU.

In both cases, environmental factors played a greater role than those related to interest–induced discretion, which is in line with theoretical expectations for this particular agent. Three external factors proved to be of particular importance. As the analysis of the Normandy Format demonstrated, low preference heterogeneity within the principal regarding the activities of the informal grouping allowed for this format to link with decisions taken by the principal. It facilitated Mogherini's discretion, embracing the narrative about the embeddedness of the Normandy Format in EU foreign policy, highlighting the coherence of the overall EU response. The perception of a deliberate division of labor between the Franco-German-led negotiations and the activities of the agent (including the coordination of sanctions and the implementation of the Ukraine-EU Association Agreement emerged (e.g., Fischer, Citation2019, p. 33; interviews 1, 4). German diplomats played a pivotal role in keeping the other members of the principal and the agent informed and in ensuring consistency between the informal grouping and the EU level.

The situation in the case of the Contact Group differed. The high heterogeneity of preferences within the principal towards the response to the war and some members of the principals’ reluctance towards the Franco-British initiative did not allow for the Group's activity to be embedded into the EU framework. The agent's discretion was therefore limited to an administrative role, which was also due to disagreements with members of the principal who initiated the informal grouping. At the same time, it is worth noting, that as the literature has shown, preference heterogeneity within collective principals might also create the right conditions for agents to shirk, thereby increasing their discretion (Dür & Elsig, Citation2011; Niemann & Huigens, Citation2011). However, due to the High Representative's limited resources and the mechanisms the member states applied to control their agent (two–step delegation), the preference heterogeneity within the principal did not trigger the agent´s discretion.

Another factor that affected the agent's discretion was the interaction among agents in the foreign policy area. As demonstrated, it limited Ashtońs discretion and facilitated Mogherini's room for maneuver. This finding indicates that the EU foreign policy architecture developed by the Lisbon Treaty with the inter–institutional positioning of the High Representative, has started to bear fruit. It can however also be a function of personal relations between the High Representative, the President of the Commission, and the respective commissioners with external portfolios. To verify this assumption, a case involving the current incumbent of the High Representative office, Josep Borrell should be studied. Finally, the context of the policymaking mattered in both cases. In the case of the Normandy Format, both the role of a third party, namely Russia and the context of negotiations at the level of the representatives of the nation-states, proved to limit High Representative's discretion hindering her participation in the format. Ashton, in turn, took part in the Contact Group, alongside the representatives of the IOs and coordinated the activities of the Group at the international level, yet due to the other factors constraining her role in this crisis, her participation did not enhance her discretion (see also: Tocci, Citation2017, p. 79).

Regarding the factors affecting interest–induced discretion, the broad interpretation of the agent´s mandate seemed to play a role and can be attributed to the personal preferences and skills of a respective office's incumbent. Mogherini embraced her inter–institutional role and actively coordinated the overall EU response toward Russia. Partially due to her difficult relations with the Commission and partially due to her limited desire to deal with the military dimension of the EU foreign policy toolbox, Ashton interpreted her mandate as a coordinating role among the member states concerning the soft power instruments. Again, more case studies would be necessary to generalize these findings.

Conclusion

This article analyzed how the decision of select EU member states to act on certain foreign policy issues through informal groupings, bypassing the EU framework, affects the discretion of their supranational agent, the High Representative. To this end, the article has drawn on advances of the principal–agent approach and operationalized the informal groupings as manifestations of pathological delegation characteristic of collective principals and examined factors affecting agent's discretion in cases of delegation anomalies.

Recognizing the limited role of the agent has in such cases, the article demonstrated that the discretion of the High Representative depends primarily on structure–induced factors. The analysis showed that the low heterogeneity of preferences within the collective principal for the actions of an informal grouping, which allows its activities to be embedded within the EU, increases the agent's room for maneuver. In such cases, the actions of the informal grouping become part of the overall EU response to a given crisis. A certain division of labor emerges between the activities of the informal grouping and those of the supranational agent, who is then enabled to fulfil their mandate and contribute to the coherence of the overall EU foreign policy. Furthermore, the interactions among agents in the same policy field have proven to decisively affect the agent´s discretion, either enhancing or limiting the agent's discretion depending on the context of a specific informal grouping. The findings however suggest that the changes introduced by the Lisbon Treaty regarding the role of the High Representative in the EU's governance structure and their inter–institutional positioning have taken root. This infers the expectation that the interaction between agents in the same field—above all between the High Representative and the European Commission—is likely to be a factor which will enhance the agent's discretion in cases of future informal groupings. Regarding interest-induced discretion, the analysis showed that the supranational agent can increase its room for maneuver by embracing all competences given them by the inter-institutional position and making use of the broad mandate provided by the Lisbon Treaty.

This article's contribution is threefold. First, it has offered empirical insights into how the structure of the delegation act from the member states shapes the discretion of their supranational agent in the EU foreign policy, focusing on the cases where no micro–delegation takes place. By doing so, this study went beyond previous research on informal groupings as occurrences of differentiated cooperation in foreign policy and exploring them as them through the scope conditions of a pathological delegation, it has provided findings on the so far underexplored question of the High Representative's discretion when such delegation occurs. Secondly, the study has shown the analytical value of conceptualizing the informal groupings as manifestations of pathological delegation patterns. The scope conditions for this type of delegation and its implications for the agent´s discretion provide an avenue to examine how delegation structure that relies on a collective principal shapes agent's discretion. Therefore, the study may be relevant for scholars who study collective delegation and its implication on agency within different institutional settings. Specifically, it can assist in analyzing the discretion of IOs secretariats. The principal–agent contracts in IOs commonly involve collective principals with heterogeneous preferences (see e.g., Elsig, Citation2011), ill–designed contracts that do not equip agents with enough resources to act effectively (see e.g., Thompson, Citation2007), and major (geo) political salience of the issues at stake. These features make them prone to delegation anomalies that affect the agent´s discretion which the conceptual framework proposed in this article, with variables affecting both structure– and interest–induced discretion, can assist in exploring.

Finally, the article as a part of the special issue on differentiation in EU foreign policy has contributed to the better understanding of the supply for differentiated cooperation as the result of delegation complexities from the collective principal—the EU member states. Hence, it has also offered policy–oriented insights on the implications of informal groupings within the EU's response to conflict and crisis. The empirical evidence suggests that such formats can be complementary to EU foreign policy, provided that they are anchored within the EU's overall response (see also: Martill & Gebhard, Citation2023).

Meanwhile, further studies considering the relationship between delegation structure and agents’ discretion in EU foreign policy are needed, including research on informal groupings that were established before the Lisbon Treaty and on these where micro–delegation (even if limited) takes place. Specifically, insights could be gained from examining the case of the E3+3 group launched for the negotiations with Iran, since this informal grouping is the only one where the agent has an official role, and which singularly allows for the discretion of the four different incumbents of the High Representative office to be examined.

List of interviews

Interview (1) with a German diplomat, 14 July 2022 (via phone)

Interview (2) with a Polish diplomat, 20 July 2022 (via Zoom)

Interview (3) with a former official of the General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union, 19 July 2022 (via Zoom)

Interview (4) with a French diplomat, 21 July 2022 (via phone)

Interview (5) with a former senior official in the European External Action Service, currently a senior official in the European Commission, 26 July 2022 (via Webex)

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank two anonymous reviewers, the CSP editors, as all participants of the workshop at the Robert Schuman Center for Advances Studies (October 20–21, 2021) for their helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. The article was also presented at the European Union Studies Association’s Conference (EUSA) (May 19–21, 2022) and at the Conference of the Standing Group on the European Union of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR, SGEU) (June 8–10, 2022), where they were fruitfully discussed by Benjamin Leruth and Sophie Vanhoonacker respectively.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Monika Sus

Monika Sus is associate professor in the Institute of Political Studies at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw and visiting professor at the Center for International Security at the Hertie School in Berlin where she leads the Horizon 2020 project “Envisioning a New Governance Architecture for a Global Europe” (ENGAGE). She is also affiliated with the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence as visiting fellow. Her research interests lie primarily in international relations, particularly in the study of European Union's foreign and security policy. Her papers appeared in International Affairs, Journal of Common Market Studies, Contemporary Security Policy, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Journal of European Integration, Global Policy, (and elsewhere).

Notes

1 The TEU also empowers another supranational agent, the president of the European Council, with external competencies, namely the external representation of the EU in matters related to the CFSP. However, the president exercises these external competencies without prejudice to the powers of the High Representative (Art 15).

2 Further EU member states joined the operation at the later stage (for more on the operation, see: IISS Strategic Comment, Citation2011).

References

- Alcaro, R. (2018). Europe and Iran’s nuclear crisis: Lead groups and EU foreign policy-making. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Alcaro, R., & Siddi, M. (2021). Lead groups in EU foreign policy: The cases of Iran and Ukraine. European Review of International Studies, 8(2), 143–165. https://doi.org/10.1163/21967415-08020016

- Amadio Viceré, M. G. (2023). Informal groupings as types of differentiated cooperation in EU foreign policy: The cases of Kosovo, Libya and Syria. Contemporary Security Policy, 44(1), 35–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2022.2144372

- Amadio Viceré, M. G., & Sus, M. (2023). Differentiated cooperation as the mode of governance in EU foreign policy: Emergence, modes and implications. Contemporary Security Policy, 44(1), 4–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2023.2168854

- Ashton, C. (2009). Written Statement, Based on remarks to the foreign affairs committee of the European Parliament. https://www.astrid-online.it/static/upload/protected/Asht/Ashton_Foreign-Affairs-Committee-writtenstatement-02.12.09.pdf.

- Ashton, C. (2011, February). A World Built on Co-Operation, Sovereignty, Democracy And Stability. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_11_126.

- Åtland, K. (2020). Destined for deadlock? Russia, Ukraine, and the unfulfilled Minsk agreements. Post-Soviet Affairs, 36(2), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2020.1720443

- Bassiri Tabrizi, A., & Kienzle, B. (2020). The High Representative and directoires in European foreign policy: The case of the nuclear negotiations with Iran. European Security, 29(3), 320–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2020.1798407

- Biscop, S. (2011). Mayhem in the Mediterranean: Three strategic lessons for Europe. (Security Policy Brief, 5). Egmont.

- Blockmans, S., & Hillion, C. (2013). EEAS 2.0. A legal commentary on council decision 2010/427/EU establishing the organisation and functioning of the European External Action Service. Centre for European Policy Studies.

- Brattberg, E. (2011). Opportunities lost, opportunities seized: The Libya crisis as Europe’s perfect storm. (Policy Brief). European Policy Center.

- Cabinet Office. (2011, March). Statement on Libya/European Council. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/statement-on-libyaeuropean-council.

- Chamon, M., & Govaere, I. (2020). EU external relations post-Lisbon. Brill.

- Council of the European Union. (2011a). Council conclusions on Libya, 12 April 2011. Brussels. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/121499.pdf.

- Council of the European Union. (2011b). Council conclusions on Libya, 21 March 2011. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/120084.pdf.

- Council of the European Union. (2011c). Council conclusions on Libya, 23 May 2011. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/F_R_52.pdf.

- Council of the European Union. (2015). Outcome of the 3389nd Council Meeting. Foreign Affairs Council. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/23345/st08966en15.pdf.

- Council of the European Union. (2018). Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the EU on the “elections” planned in the so-called “Luhansk People's Republic” and “Donetsk People's Republic for 11 November 2018. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/11/10/declaration-of-the-high-representative-on-behalf-of-the-eu-on-the-elections-planned-in-the-so-called-luhansk-people-s-republic-and-donetsk-people-s-republic-for-11-november-2018/.

- da Conceição-Heldt, E. (2011). Variation in EU member states' preferences and the Commission's discretion in the Doha round. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(3), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.551078

- da Conceição-Heldt, E. (2017). Multiple principals’ preferences, types of control mechanisms and agent’s discretion in trade negotiations. In T. Delreux, & J. Adriaensen (Eds.), The principal agent model and the European Union (pp. 203–226). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55137-1_9

- de Galbert, S. (2015). The impact of the Normandy format on the conflict in Ukraine: Four leaders, three cease-fires, and Two summits. (Commentary). Center for Strategic and International Security.

- Delreux, T. (2010). Measuring and explaining discretion. The case of the EU as international environmental negotiator. Paper presented at the Politicologenetmaal 2010. Leuven.

- Delreux, T., & Adriaensen, J. (2017). Introduction. Use and limitations of the principal–agent model in studying the European Union. In T. Delreux, & J. Adriaensen (Eds.), The principal agent model and the European Union (pp. 1–35). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Delreux, T., & Adriaensen, J. (2018). Twenty years of principal-agent research in EU politics: How to cope with complexity? European Political Science, 17(2), 258–275. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0129-4

- Delreux, T., & Keukeleire, S. (2017). Informal division of labour in EU foreign policy-making. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(10), 1471–1490. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1216151

- Dijkstra, H. (2017). Non-exclusive delegation to the European External Action Service. In T. Delreux, & J. Adriaensen (Eds.), The principal agent model and the European Union (pp. 55–82). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dijkzeul, D., & Salomons, D. (2021). International organizations revisited: Agency and pathology in a multipolar world. Berghahn Books.

- Dür, A., & Elsig, M. (2011). Principals, agents, and the European Union's foreign economic policies. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(3), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.551066

- EEAS. (2013). European external action service. Review. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-7-2013-0278_EN.html.

- EEAS. (2015). Remarks by High Representative/Vice-President Federica Mogherini following the extraordinary foreign affairs council on ukraine. https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage_hy/6194/Remarks by High Representative/Vice-President Federica Mogherini following the extraordinary Foreign Affairs Council on Ukraine.

- Elsig, M. (2007). The EU’s choice of regulatory venues for trade negotiations: A tale of agency power? Journal of Common Market Studies, 45(4), 927–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00754.x

- Elsig, M. (2010). European Union trade policy after enlargement: Larger crowds, shifting priorities and informal decision-making. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(6), 781–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2010.486975

- Elsig, M. (2011). Principal-agent theory and the World Trade Organization: Complex agency and “missing delegation.” European Journal of International Relations, 17(3), 495–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066109351078

- EU Delegation to Turkey. (2011). Remarks by EU High Representative Catherine Ashton at the Cairo conference on Libya. https://www.avrupa.info.tr/en/eeas-news/remarks-eu-high-representative-catherine-ashton-cairo-conference-libya-3858.

- Euractiv. (2015). At summit, Ukraine to press EU for peacekeepers. Euractiv. https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/news/at-summit-ukraine-to-press-eu-for-peacekeepers/.

- European Commission. (2011). Statement by the high representative, Catherine Ashton, following the meeting of the Contact Group on Libya Istanbul, 15 July 2011. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/123891.pdf.

- European Council. (2014). European Council conclusions on external relations (Ukraine and Gaza). https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/143990.pdf.

- European Council. (2022). EU restrictive measures against Russia over Ukraine (since 2014). https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/restrictive-measures-against-russia-over-ukraine/.

- European Union. (2011). Declaration by the high representative, Catherine Ashton, on behalf of the European Union on events in Libya. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/cfsp/119397.pdf.

- Fabbrini, S. (2014). The European Union and the Libyan crisis. International Politics, 51(2), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1057/ip.2014.2

- Fischer, S. (2019). The donbas conflict. (SWP Research Paper, 5). Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2016). More integration, less federation: The European integration of core state powers. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1055782

- Grevi, G. (2020). EU foreign policy needs “embedded” differentiation. (commentary). European Policy Center.

- Grevi, G., Morillas, P., Soler i Lecha, E., & Zeiss, M. (2020). Differentiated cooperation in European Foreign Policy: The Challenge of Coherence. (EU IDEA Policy Papers, 5).

- Gutner, T. (2005). Explaining the gaps between Mandate and Performance: Agency theory and World Bank environmental reform. Global Environmental Politics, 5(2), 10–37. https://doi.org/10.1162/1526380054127727

- Haukkala, H. (2016). A perfect storm; Or what went wrong and what went right for the EU in Ukraine. Europe-Asia Studies, 68(4), 653–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2016.1156055

- Hawkins, D. G., & Jacoby, W. (2006). How agents matter? In D. G. Hawkins, D. A. Lake, & D. L. Nielson (Eds.), Delegation and agency in international organizations (pp. 199–228). Cambridge University Press.

- Helwig, N. (2014). The High Representative of the Union: The agent of Europe’s foreign policy [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University Cologne.

- Helwig, N. (2017). Agent interaction as a source of discretion for the EU High Representative. In T. Delreux, & J. Adriaensen (Eds.), The principal agent model and the European Union (pp. 105–130). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Helwig, N., & Rüger, C. (2014). In search of a role for the High Representative: The legacy of Catherine Ashton. The International Spectator, 49(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2014.956423

- Howorth, J. (2011). The “New Faces” of Lisbon: Assessing the performance of Catherine Ashton and Herman van Rompuy on the global stage. European Foreign Affairs Review, 16(Issue 3), 303–323. https://doi.org/10.54648/EERR2011022

- IISS Strategic Comment. (2011). War in Libya: Europe’s confused response. IISS Strategic Comments, 17(4), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/13567888.2011.596314

- Kassim, H., & Menon, A. (2003). The principal-agent approach and the study of the European Union: Promise unfulfilled? Journal of European Public Policy, 10(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176032000046976

- Keukeleire, S. (2006). EU core groups specialisation and division of labour in EU Foreign Policy. (CEPS Working Document, 252). Center for European Policy Studies.