ABSTRACT

This article deals with the question of how communities relate to their heritage in Estonia by focusing on four case studies, two of which represent archaeological sites and two dark heritage sites, and the respective communities involved with these places. The main objective is to understand the dynamics of how heritage communities preserve, use and remember their heritage. Another aim is to explore contemporary community-based and participatory heritage management practices in Estonia and how they relate to the ideals described in the Faro Convention. We examine how the location, the contribution of researchers and personal connections to historic places motivate local people, enthusiasts and the state to care for the sites. It is demonstrated that community-based heritage management is most effective when people are emotionally attached to historic sites, have a sense of ownership and want others to engage with and experience them.

Introduction

The role of communities in the context of heritage is becoming increasingly important. This has been stimulated by international initiatives such as the Faro Convention (Council of Europe Citation2005), where cultural heritage is seen as a valuable resource for society, inextricably linked to people (Cerreta and Giovene di Girasole Citation2020; Mydland and Grahn Citation2012). Furthermore, numerous studies have been published that provide examples of the role of communities in preserving (e.g. Soininen Citation2017), presenting (e.g. Enqvist Citation2014) or engaging local heritage sites in the development of a region (e.g. Shipley and Snyder Citation2013). Communities and their relation to heritage in Estonia have been briefly analysed, but more from the perspectives of heritage politics (Bardone et al. Citation2020) and heritage management (Konsa Citation2019). Also, the years of occupation in the Baltics have left their mark on heritage; many shifts in politics as well as mindsets have often put heritage in an unfavourable position – it has not received enough care, has been neglected or even ignored (Vaeliverronen et al. Citation2017). This research offers a new perspective (in the Estonian context), focusing on how communities maintain, use and remember their heritage, with examples of community involvement at two very different types of heritage sites. In particular, the potential impact of locality, personal connection and interpretation of historic sites, and the role of stakeholders in the management of historic sites will be considered.

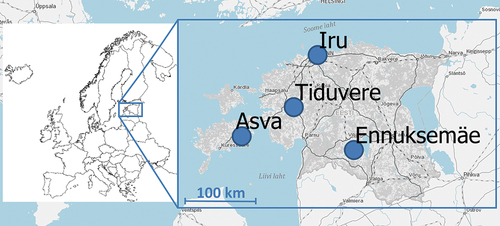

The chosen sites are two archaeological monuments, Bronze Age hill forts of Asva and Iru, and two so-called Forest Brother bunkers in Tiduvere and Ennuksemäe that were first built in the mid-20th century and serve as symbols of resistance against the Soviet rule in Estonia (). These two types of sites have equally significant roles in Estonian history, but are varied in all other respects. Such a broad perspective allows us to analyse how communities use diverse historic sites and what are the attitudes and connotations associated with them. It also gives a better idea of the role of communities in heritage preservation in Estonia and how close the contemporary practice is to the ideals described in the Faro Convention.

Figure 2. The analysed sites 1) Asva hill fort 2) Iru hill fort 3) Ennuksemäe underground bunker 4) Tiduvere above ground bunker. Source: Maili Roio (1–2) and authors (3–4).

First, however, it is necessary to outline the nature of the sites we are discussing. The archaeological monuments studied are among the oldest hill forts in Estonia, which were used in the Late Bronze Age (from about the middle of the 9th century BCE), with the last known historic usage from the end of the Viking Age (9th–11th century) (Tõnisson Citation2008b, 187–188; Tõnisson Citation2008a, 250–251; Lang Citation2020, 172). It is worth noting that these fortified settlements are regarded as some of the most prominent monuments in the whole Baltic region in the Bronze Age, and merely four are known from Estonia, providing a rich and diverse record of the Late Bronze Age environment (Lang Citation2007, 57). Although the Bronze Age itself is distant in terms of time and might be difficult for the general public to be interested in, archaeology is often perceived as a fascinating discipline. These aspects gave us the impetus to explore how these sites are regarded by different communities. Focusing on archaeological sites that are significant, but less known to the general public, provides a genuine picture of how communities engage with archaeological heritage and what is the potential for community-centred heritage management in Estonia.

Tiduvere and Ennuksemäe bunker sites represent another kind of heritage and memorial loci in Estonian history. During the Second World War and the first years of the Soviet occupation of Estonia, thousands of people hid in forests, bogs and elsewhere in nature, in the fear of killing or deportation to Siberia by the Soviet officials. They were known as the Forest Brothers and out of thousands of hiders only small groups participated actively in the guerrilla resistance against Soviet rule (see more in Kaasik et al. Citation2020; Mertelsmann Citation2020, 35–45). In order to survive in nature, bunkers and hideouts were built, which were rapidly replaced or abandoned in case of danger. The history of the sites associated with the Forest Brothers can be measured in decades, and many Estonians have a family connection or personal memories associated with the Forest Brothers (e.g. giving them shelter, food, or information).

More broadly, the legacy of the Forest Brothers can be placed in the context of ‘dark’ or ‘difficult’ heritage (see more in Macdonald Citation2015; Thomas et al. Citation2019), being linked to the occupation and the subsequent forced collectivisation, deportations, forced-labour camps and Russification policies (see more in Mertelsmann and Rahi-Tamm Citation2009; Rahi-Tamm Citation2017). Although the concept of dark heritage covers a wider range of topics and time periods, it has been used in this article to give a broader meaning to the tragic events of the twentieth century. Issues related to the Second World War and the Soviet occupation of Estonia have been studied mainly by historians, but more recently archaeologists have also contributed by conducting archaeological investigations at the bunker sites of the Forest Brothers (e.g. Kiudsoo, Andreller, and Kuusk Citation2015). The focus of the latter is primarily on understanding their everyday life and identifying individuals associated with specific bunker sites. A broader discussion of such places is still largely lacking in Estonia, even though these sites have become a part of the cultural and historical landscape. We focus on restored bunkers as the reconstruction, maintenance and organising events at the bunker sites require long-term commitment, which helps to gain a better understanding of the dynamics and motivation of the communities involved.

Cultural heritage and heritage communities

The concept of community has been defined in several ways since the 1960s (see more in Waterton and Smith Citation2010). In the context of cultural heritage, the definition of community is similarly difficult to establish and there are a number of conceptions with diverse implications. For instance, activities at the local level can mean individual contributions based on ownership, shared interests or activities administered by the local government. Moreover, contemporary heritage management is multi-layered and community involvement is becoming standard and the number of enthusiasts who want to contribute to local heritage via their community is increasing (Watson and Waterton Citation2010). In this way, such sites and places of cooperation provide an opportunity to strengthen social ties within a community between different stakeholders, thereby creating positive emotions (e.g. Crooke Citation2010) or supporting national or regional self-esteem. On the other hand, such sites can support the local business development (e.g. Grimwade and Carter Citation2000), become relevant for learning about history (e.g. Goulding and Domic Citation2009), or be important places for community gathering and activities (e.g. Mydland and Grahn Citation2012). In Estonia, heritage management has traditionally been site-oriented, which means that the focus of the entire management process lies on the object itself and the main modus operandi has been the top-down management. However, attitudes have been shifting slowly and heritage has become more value-based and more people besides professionals are involved in every stage of heritage management (see more in Konsa Citation2019).

In the Faro Convention, the notion of a heritage community is defined as people who value certain aspects of cultural heritage that they wish to preserve and transmit to future generations through a public network of activities (Council of Europe Citation2005: Article 2b). The term defines people who associate themselves with local heritage and value it, but also includes people who create or define heritage (Zagato Citation2015, 147). It is important to note that a person can be a member of several heritage communities simultaneously and that these communities would not exist without heritage, and do not require ethnic or national ties between the members of the community (Colomer Citation2021; Zagato Citation2015, 152, 159 and references therein;). The concept of a heritage community in the Faro Convention is quite heritage-centred, which has some limitations for current purposes. The definition of a heritage community does not provide enough insights from communities’ perspective, such as finding motivation, inspiration and tools to preserve and present heritage (Colomer Citation2021). The role of communities in interpreting history and linking the past with the present is universal, but the means and the dynamics depend on the region, its heritage, and the community itself. In order to gain a closer perspective on mediators, their attitudes and meanings of selected historical sites, we have differentiated the broader concept of heritage community into three levels based on opportunities for community members to participate in the management and use of heritage: the local people, the enthusiasts and the state (see below).

Background and methods

The sites were chosen based on the objects themselves, their management, and localities. Asva and Iru hill forts represent two different environments – Asva is a rural area far from larger cities on an island, but Iru is a site in the outskirts of the capital. Both reconstructed Forest Brothers bunkers are, as expected from the function, far from settlements and villages. The sites also differ in their age – the hill forts are archaeological and direct contact with the people who used the sites is long gone. Whereas Forest Brothers were parents, grandparents, close relatives of the people who live today and are still personally remembered.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in person and online, altogether 12 interview sessions and 25 interviewees. Our premise was that the key to understanding the current state and potential of community heritage in Estonia, it was crucial to find participants with an interest in heritage and some connection to the sites in question. Information about the study was distributed in local libraries, posted on social media sites (e.g. regional Facebook groups), visitor centres and among local activists. Participants were thus selected on the basis of their self-reported interest in the study.

The study was conducted in a manner that complied with ethical standards for research involving human subjects. The participants were provided with the purpose of the interviews and their consent was obtained prior to the interviews. No personal information was collected or asked and all interviews were anonymised and given pseudonyms.Footnote1 Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and responses qualitatively analysed. Respondents represented different genders and age groups (all adults). The interviews followed a pre-designed interview guide, which included a series of questions about the use, maintenance and significance of the heritage sites in question.

Based on the answers, the interviewees were identified as locals, enthusiasts or representatives of the state. In this paper, we will first refer to the local people who live close to the sites and encounter them in their activities. These are people who feel that historic places and heritage are important to themselves and the wider region and who are active members of the (heritage) community. As a result of their activities, they may recruit new members to their community and attract project-based funding.

We also consider as a community those who have a connection with the site and who, although they may not live close to the sites in question, contribute as much as they can to the upkeep and development of the site, as well as to the events that take place there. We refer to this group as the community of engagement or enthusiasts. They are often volunteers and do not receive any monetary compensation, but for some enthusiasts, heritage and its promotion is closely linked to their daily income, thinning the line between hobbies and work activities.

The role of the state, in the form of local governance should also be highlighted, as it differs from grassroots activities. Heritage is mainly reflected in development plans and spatial planning documents such as comprehensive spatial plans. The latter gives municipalities the opportunity to designate areas of environmental or cultural value by establishing certain rules for the conservation of buildings or landscapes. In cases where the sites are not protected by the state already, the local municipality may choose to note areas of special interest in their planning decisions, but can also support heritage management in other decision-making processes e.g. targeted support programmes. Heritage can be used as a resource in a sustainable way to promote economic, environmental or educational development.

The three types of communities described above have different priorities and motivations for dealing with heritage and it must be noted that some people may belong to several groups (e.g. based on their free time and work activities). For this study, the people were grouped based on their role that takes up the most time when interacting with the sites in question.

Sites of interest

Understanding how the places are perceived by various stakeholders is crucial for discussing the significance of the studied sites. From a cultural heritage perspective, objects and places can be divided into several value categories and dimensions. For example, Estonian legislation classifies cultural heritage into six classes of monuments: historical, archaeological, architectural, art and technical monuments, along with historical natural sacred sites (Heritage Conservation Act Citation2019). It should be noted that international or national importance does not always translate into communal, regional or personal interests. Some communities may wish to preserve sites as they are (e.g. Hester Citation1993). Other stakeholders may value places that have the potential to be reconstructed, which may help to promote tourism and bring economic benefits. The latter is the case even if the sites are associated with something negative, such as conquest, war or occupation (cf. Meskell Citation2002). In general, people have a stronger attachment to places that can be associated with personal or communal memories, legends, and stories (see also Wang Citation2023).

As mentioned above, the Faro Convention indicates that cultural heritage can be beneficial to communities (Florjanowicz Citation2016). The benefits of community involvement in heritage management can be seen, for example, in the museums of England and Australia where community engagement strategies emphasise learning in a visual, hands-on, and free-choice environment (Perkin Citation2010). However, institution-community cooperation must overcome the imbalance of power. The authority to interpret heritage should be shared equally between stakeholders, but in reality it remains largely under the control of the authorities (Perkin Citation2010, 108–110; Zhang Citation2022), and this is also the case in Estonia.

Inevitably, the general tendency still leans towards a top-down model that does not encourage in-depth collaboration between communities and government-funded heritage organisations (Bardone et al. Citation2020, 257–258). An unwillingness to share authority can lead to a loss of community-specific cultural values, ownership, identity, and inclusion (Perkin Citation2010, 111). For example, the private owners of heritage objects in Estonia often see the National Heritage Board as an authority that restricts their rights to maintain their property (Bardone et al. Citation2020, 258). Simultaneously, good collaboration between communities and heritage agencies can help to identify the expectations of the stakeholders, contribute to a stronger sense of community, and improve accessibility and presentation of information (Fredheim Citation2019, 74). The sites analysed showed a mixture of evidence of both community-based and top-down approaches, which will be highlighted later in this paper. The hill forts studied are listed monuments and protected by the state, but the bunker sites are unlisted heritage and rely more on how stakeholders use, value and manage them.

Archaeological sites: Bronze Age hill forts

Hill forts are usually easily noticeable in the landscape: they have a recognisable shape (modified by human activities; traces of fortifications) and a cultural layer consisting of artefacts and ecofacts from the periods of use. Additional indications about archaeological monuments can be found in respective pieces of folklore or in place names.

The discovery of the Asva hill fort () dates back to the early 1930s, when Orest Reis, a local student, sought an explanation for a few stray finds and the toponym ‘Linnamäe põld’ (‘Hill fort field’), which he thought might refer to a hill fort and he carried out trial excavations there on his own. The findings confirmed his suspicions and the archaeology department of the University of Tartu started investigations in 1934, also clarifying the Late Bronze Age date of the hill fort (Indreko Citation1939, 17, 47).

Today, the Asva hill fort is located on the edge of the village, and the slopes have been used for winter sports and the icy areas as a skating rink by the local community for years. The site has become a tourist destination only in the last decade. The local community is proud of Asva’s heritage and is independent and active in promoting it () (Interviews 4, 22.12.2022; 5, 29.12.2022). The main tourist centre in Asva is not the hill fort itself, but a nearby Viking Age theme park. The idea of a theme park dates back to 2006 where the initial goal was to reconstruct the hill fort fortifications in the close vicinity of the site, but it did not receive the approval of the National Heritage Board. However, the local activist’s wish to showcase the local prehistory led to the construction of the Viking Village theme park in 2017, two kilometres from the hill fort. The existing tourist attraction is now seen as a much better realisation of the original idea: the site is easily accessible and there are no heritage-related restrictions for new development. (Interviews 4, 22.12.2022; 5, 29.12.2022).

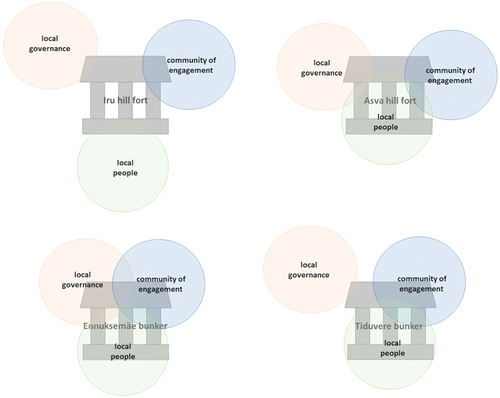

Figure 3. Analysed heritage communities and their involvement with the sites in question. Source: authors.

Archaeological research carried out over the last decade has also contributed to the Viking Village’s scientific programme and general knowledge about the site (Interviews 4, 22.12.2022; 5, 29.12.2022). A total of 7000–8000 people visit the Viking Village annually and there are several businesses in the surrounding area that also benefit economically from the promotion of the Viking Village (Interview 4, 22.12.2022). The local government officials are aware of larger projects and are pleased to see tourism on the island thriving, but the Asva hill fort is not among the main focus of the island tourism goals (Interview 3, 22.12.2022).

The Iru Linnapera hill fort () was discovered in the early 20th century, when Baltic-German schoolteacher Artur Spreckelsen, reading the national epic ‘Kalevipoeg’, noticed a story about the hill of Iru, which gave him the idea that it could be an ancient hill fort (Vassar Citation1939, 57). After a lecture and a newspaper article in 1922, the site became widely known as a hill fort. Many hill forts were excavated in the late 1930s and the need to research the Iru hill was also brought up (Vassar Citation1939, 57–58).

Iru village was originally a rural settlement of scattered farms, but it expanded in the 1970s when plots of land and housing were subdivided for the workers of the nearby Bird Factory. A common workplace brought the villagers together also during their free time. In the 1980s, there was an active community, which practised winter sports on the hill fort. However, maintenance of the hill fort has never been carried out on a community basis (Interview 11, 11.01.2023). Nowadays, the Iru village has become a suburban area of Tallinn and a new road network has dispersed the historical connections with other villages.

Unlike the other communities interviewed, Iru hill fort is not a place that attracts and connects locals, activists or the local government (). One explanation seems to be that Iru hill fort is now part of the territory of the capital city of Tallinn, and as the village has now suburbanised, the community there spends less time together. Nevertheless, children from nearby schools are still taken to the Iru hill fort as part of their history lessons (Interviews 11, 11.01.2023; 12, 13.01.2023). Interestingly, the people of Iru village associate themselves more with the Iru Ämm (Iru Mother-in-Law, also known from the national epic ‘Kalevipoeg’) landmark, which remains within the village borders. It was originally a landmark boulder that has now been destroyed, but replaced with a new sculpted one. It used to be a road sign where people who came to Tallinn had to give their blessing before crossing the Pirita River (Remmel Citation2005). In 2008, local activists founded the Iru Ämm Club, which organises the Iru Ämm Festival in the summer and invites historians to give presentations (Interview 11, 11.01.2023).

Dark heritage sites: restored bunkers of the forest brothers

Unlike the majority of hill forts, it is difficult to locate the bunker remains of the Forest Brothers as they were designed to be undetectable and blend in with the surroundings. The bunkers that were found during their period of use were often destroyed by the Soviet officials in a military operation against the Forest Brothers. The remains of the bunker sites can be found by using written sources (e.g. interrogation protocols), memories, and archaeological fieldwork methods. Bunker sites close to nature trails are sometimes marked with information boards, but are rarely reconstructed.

The restored Ennuksemäe underground bunker () is situated on a forested plateau between two marshes. The main activists are locals and history enthusiasts, who live in nearby settlements. Despite the fact that the bunker was not mentioned publicly during the Soviet era, its history was known and the relatives of those killed in the bunker battle kept the place tidy and brought flowers for decades (Interview 1, 26.10.2022). The reconstruction and maintenance of the site was started by the local municipality in 2007. Several municipal officials are themselves keenly interested in the stories of the Forest Brothers and have heard stories from Ennuksemäe in their childhood, which motivated them to restore the bunker ().

However, 20th century history is difficult, which also manifests itself in how the importance of the Forest Brothers is perceived and not everyone feels that their legacy is positive or should be remembered. There are two cases of vandalism related to the process of reconstructing the Ennuksemäe bunker that illustrate this. First, the door of the Paistu Church was set on fire when the remains of the Forest Brothers, who died in the bunker during a battle in 1945, were reburied to the cemetery in 1993. Second, the bunker which was reconstructed in 2007 was set on fire in 2016 (Interviews 1 and 2, 26.10.2022; Haav Citation2016). There was a public discussion after the fire whether to restore the bunker once again or not. Some locals voiced the opinion that the municipality’s money should be invested elsewhere (e.g. Rauk Citation2020). But the idea also received strong support and the youngest discussant, a high school student, felt that the restoration is important because it is a symbolic object that helps Estonians understand the overall meaning and impact of the Soviet period (Talvik Citation2020). The bunker was restored more fire- and weatherproof than before and it has become an important tourist attraction. According to the visitors’ book there are several people visiting the bunker daily during the summer season (Interview 1, 26.10.2022). The bunker and its surroundings are used by smaller groups for mini-hikes and picnics and guided tours can be arranged by local guides on request (Interview 1, 26.10.2022) Every year, local enthusiasts organise an annual hike in Ennuksemäe to celebrate the anniversary of the Republic of Estonia, there are always many familiar faces as well as some newcomers (Interviews 1 and 2, 26.10.2022).

The Tiduvere Põrgupõhja bunker () is located in the forest, east of the village of Tiduvere. The forest is owned by the state, but the state and the local authorities are not involved in the development of the bunker (Interviews 8, 10.01.2023; 10, 15.01.2023). The reconstruction of the site was largely the work of the Museum of Occupations (now Vabamu), for whose exhibition the bunker was originally built. After the end of the exhibition, the bunker was moved to Tiduvere, where a similar building had once stood. The bunker was weatherproofed and can be used for free accommodation (see more in McKenzie Citation2020). The reconstruction and maintenance of the Tiduvere bunker has been carried out mainly in cooperation between locals and the enthusiasts. The latter are people who are researching the legacy of the Forest Brothers professionally or as a hobby () (Interviews 7, 6.01.2023; 8, 10.01.2023; 9, 11.01.2023; 10, 15.01.2023). It was pointed out that the main researcher of the site has become an important person in the local community, even though he has no family connection to the area; he has ‘grown close’ to the site and the locals over time (Interviews 7, 6.01.2023; 8, 10.01.2023; 9, 11.01.2023; 10, 15.01.2023).

Partly related to the bunker is the annual Põrgupõhja expedition, a military landscape game on the paths of the Forest Brothers. The organisers of the expedition have become a community that is closely associated with the site. Local people are also involved in the expedition and give a hand to the organisers where possible (Interviews 8, 10.01.2023; 9, 11.01.2023; 10, 15.01.2023). Interestingly, local and distant activists consider the role of the other stakeholder group to be the most important in initiating and managing bunker-related activities (Interviews 7, 6.01.2023; 8, 10.01.2023; 9, 11.01.2023 and 10, 15.01.2023). For commemoration they hold the anniversary of the battle of Põrgupõhja bunker on the last day of the year. People gather in the bunker, place a memorial wreath, and spend time together. The organisers are grateful that people of all ages are present and that there are new participants every year (Interviews 7, 6.01.2023; 8, 10.01.2023; 9, 11.01.2023; 10, 15.01.2023). In August, there is a concert organised by volunteers, with young musicians as the main performers. According to the bunker’s guestbook, the site is mainly visited during the warm season, with a few visitors every day (Interviews 7, 6.01.2023; 8, 10.01.2023; 9, 11.01.2023; 10, 15.01.2023).

Discussion: our past, our responsibility?

Heritage is often seen as something that communities value and want to preserve, as part of the expression of local identity, and sometimes as an economic resource (Bardone et al. Citation2020, 253). For instance, Fredheim (Citation2019, 66) summarised the aims of the projects in the Adopt a Monument Scotland programme and found that financial benefit/tourism, educational activities, self-development, participation, demonstration, conservation, research, interpretation were all mentioned as aims. Although the objectives of the heritage communities discussed in this study also reflect the above, we are more interested in the broader trends in Estonia, especially in relation to the ideals mentioned in the Faro Convention. The convention seeks to move away from a strict top-down model to one of heritage appreciation and protection, and intends to give communities a greater role in relation to their heritage, encouraging people to see heritage as a resource rather than a burden. Moreover, implementing the principles of community-based and participatory heritage conservation is a separate state-level objective in Estonia, which is reflected in the latest version of the Heritage Conservation Act (Kadakas Citation2020, 251).Footnote2

The sites and communities surveyed allow tentative conclusions to be drawn about Estonia. Three key criteria were defined from the interviews (maintenance together with preservation, site use and significance of the sites) and the results are discussed in terms of these criteria. The discussion shows that, even without formal and coordinated involvement, there are heritage communities that are committed to historic places and clearly see the sites in question as valuable resources. However, other communities (or sites) would benefit greatly from a participatory management model or top-down coordination.

Preserving and caring for place

The first step in embedding the use of historic sites and their importance in the collective memory is to preserve them. The regular maintenance of the sites analysed is the responsibility of many parties, and it depends mainly on who has taken the initiative. In the case of Ennuksemäe, the site is regularly maintained and an employee from the local government visits it every two weeks and if necessary cleans the area and provides firewood for campers. There are also occasional communal clean up days at site when more work is needed (Interviews 1 and 2, 26.10.2022). In the case of Tiduvere, the role of the local government is marginal and the bunker and its surroundings are maintained by volunteers. They organise communal clean up days in spring time and minor maintenance work is done over the year, but mostly before and after events that take place at the bunker site (Interviews 7, 06.01.2023; 8, 10.01.2023; 9 11.01.2013; 10 15.01.2023).

When it comes to hill forts, the strong connection of the local community with Asva hill fort was evident. The land under the hill fort belongs to a family that is actively involved in valuing the local heritage, and although it is difficult to reach the hill fort, the area is kept in good condition by the owners. Interviewed people had bright memories of the Iru hill fort from their youth, but the Iru Ämm boulder has become a more important landmark for the locals. The city maintains the area of the hill fort in cooperation with the Forest Management Centre, which is a part of their legal responsibilities.

Generally, the sites where community members of different ages care for the heritage tend to have fewer problems with site maintenance and vandalism (Grimwade and Carter Citation2000). The sites discussed also confirmed the importance of enthusiasts and local people. Interestingly, the role of local government in maintaining the sites was marginal, with the exception of the Ennuksemäe site, where the main enthusiasts and activists are also local government employees (). Finally, active communities organise events at these sites, they feel more responsible: they want visitors to have a pleasant experience and they ensure that the site looks clean and well maintained after the events. Therefore, an attentive and involved heritage community who has personal connection or memories of the site does more on a daily basis to maintain and preserve historic places than any official body. Affective engagement can create a strong connection with the site and the one experiencing it (Latham Citation2013; Tolia-Kelly, Waterton, and Watson Citation2017).

Activities and use of the sites

The use of sites and the activities held on them are directly linked to their modern functionality. The Iru hill fort has not been actively promoted by the local community and is mainly used for walks and other leisure activities. The more active heritage community of Asva is concentrated around the Viking Village theme park, and although it is a Viking village, it also showcases Bronze Age life. Locals have created educational programmes, including short animations, to convey the history of the site in a more exciting way (Interviews 4, 22.12.2022; 5, 29.12.2022). In contrast, Saaremaa parish officials saw mainly the tourism potential of the Viking Age heritage. This seems to be linked to the year of Vikings in 2021 when most cultural events on the island were organised according to this theme.Footnote3

The reconstructed bunkers of the Forest Brothers have several uses. On the one hand, they are dark heritage sites associated with crimes against humanity and bear a message of Estonian resistance to Soviet occupation. The life stories of the Forest Brothers (and often the people who helped them) are tragic, and commemoration events are one of the most important activities at the bunker sites. On the other hand, the reconstructed bunkers allow anyone interested to imagine the life of the Forest Brothers. Exploring the bunker, looking and touching the items in it creates a personal connection with the site and the life stories of the people who hid there (Interview 10, 15.01.2023). Furthermore, the locals take their guests to the bunkers in case they want to show them something in the area (Interviews 1, 26.10.2022; 10, 15.01.2023). Unlike many other dark heritage sites, the focus of the restored bunkers is not only on the tragic side of history and commemoration of the dead, creating therefore a rather special phenomenon, where places with a violent and tragic history have taken on new and lighter endeavours without forgetting the old.

Some of the sites concerned are frequently visited, but they have higher tourist potential to bring economic benefits to the region. Heritage communities expect informed tourists who know what the site is about and what opportunities are available in the area. There is a fear that if a historic site becomes too well known, it could be littered or plundered, some interviewees mentioned that the National Heritage Board has been noted of suspicion of illegal activities (Interviews 3, 22.12.2022; 6, 29.12.2022; 7, 6.01.2023; 10, 15.01.2023). It was pointed out that tourists might expect something more grandiose or interactive than a wooden hut or a relatively flat and bare hill fort (Interviews 5, 29.12.2022; 8, 10.01.2023). For all the sites it was suggested that a wider audience may want to experience and connect with the past through objects or reconstructions that they can touch, narrated history they can hear, or virtual reality that they can see (Interviews 3, 22.12.2022; 5, 29.12.2022; 6, 29.12.2022; 8, 10.01.2023).

The events organised by the active members of the heritage communities at the bunker sites have a clear message. Stakeholders believe that a variety of events encourage visitors to reflect on the twists and turns of local history and to appreciate life in freedom. In the case of archaeological monuments, heritage communities face different kinds of challenges – the Bronze Age is a distant and abstract period, making it difficult not only to understand and relate to it, but also to present and promote it to a wider audience. Despite the different historical and contextual natures of these sites, they share a common aspiration: to connect people with their history and, without being aware of it, active communities fulfil the ideal of the Faro Convention.

Importance and remembrance of the sites

Hill forts have been in the centre of attention since the 1930s and they have functioned as places for leisure and recreation. The connection with modern people is indirect – life on the hill forts was long enough ago that members of heritage communities do not associate themselves with Bronze Age or Viking Age people directly. But thousands of years of history contribute to the uniqueness of the site and to the local people’s attachment to it. In Asva, the deeds of a local student who discovered the hill fort almost a hundred years ago are still greatly appreciated. According to one interviewee when they passed the home of Orest Reis as a child, their parents always said that there lived the man who discovered the Asva hill fort (Interview 5, 29.12.2022).

Local people appreciate the role of archaeologists in interpreting the hill forts and introducing Estonian prehistory (Interviews 5, 29.12.2022; 12, 13.01.2023). The last archaeological fieldwork campaign has been ongoing in Asva since 2012 (Sperling et al. Citation2015), which gives locals the opportunity to get first-hand information about new discoveries and archaeology more generally. This, in turn, strengthens their bond with the site even more. The last long-term excavations at the Iru hill fort took place in the late 1980s followed by short-term surveys in 2006 and 2007 (Kraut and Tamla Citation2007, 22–23; Kraut and Tamla Citation2008: Table 1: 38). It is likely that the lack of (recent) fieldwork at the site has also had some effect on the locals and their appreciation of the hill fort besides the somewhat unfortunate location that is located across the river of the village. The example of the Iru Ämm landmark shows that the local community has interest in local history, but it can be expected that active presence of an archaeologist would stimulate their interest in the hill fort as well. As other examples show, presenting and promoting heritage is most effective when done in a collaborative way, and joint activities help to create an emotional and personal connection to the heritage.

The theme of the Forest Brothers is part of the narratives of Estonianism to this day, but neutral information on the subject was lacking during the occupation due to the Soviet-era cultural and political context. If ordinary people were to take an interest in the issue, it could lead to increased scrutiny by the authorities, with potentially serious consequences (Virkkunen Citation1999, 86). Thus, topics that did not support ‘official’ narratives were discussed only with people who could be fully trusted (e.g. family members) and it was safer not to ask questions about the legacy of the Forest Brothers (Interviews 5, 29.12.2023; 10, 15.01.2023). There are still mixed emotions about the topic and some people think that places associated with death and suffering are inappropriate to visit (Interview 1, 26.10.2022). This opinion is not dominant, but should be mentioned because places of dark heritage have multiple connotations. Sometimes the views on how such places should be treated in the wider (national) narratives are dramatically different. A case in point is the communist labour and prison camp in Belene, Bulgaria, where the state does not encourage this issue to be raised, hampers the commemoration events, and tries to strip off the meaning bestowed on it by survivors (see more in Topouzova Citation2019).

In exploring the meaning and importance of bunker sites, the interviewees shared personal stories and a desire to contribute to remembering the history. Some respondents found it difficult to put into words what the site and associated themes mean to them. It was pointed out that a bunker site is a ‘sacred place’ and an ‘important place’ and if the place had no internal significance ‘I wouldn’t take my niece or nephew there’ (Interview 9, 10.01.2023). The restored bunker sites have a special meaning for the relatives of the fallen Forest Brothers: it is a place where they can pay their respects and remember their loved ones. One of the interviewees pointed out that although they are originally from a different part of Estonia, then Tiduvere has been a place to visit and think about the stories told by their mother about their uncle who was a Forest Brother (Interview 10, 15.01.2023).

As demonstrated above, heritage resonates with members of the heritage communities when there is a personal connection, when they value their locality and are generally interested in history. The appreciation of heritage is clearly linked to the community and there is a strong will to define what is important at the very local level. The valorisation of cultural heritage ensures that historic sites are actively used, well maintained, and, as such, become part of regional identity and memory.

Conclusions

Community engagement with heritage is multifaceted and depends on a wide range of aspects. Our study demonstrates that the location of historic sites, the contribution of researchers and the narratives associated with objects are among the most important factors influencing their meaning and use. The care for the sites, whether listed or not, begins with knowledge about them and their character, the appreciation of the heritage and usage of sites. At the same time, locals and other enthusiasts may perceive the importance of historic loci somewhat differently than researchers and focus on topics that seem more relevant or interesting for them (e.g. leisure activities, Viking heritage). This viewpoint gives such areas additional content, which helps to further strengthen the link with heritage at the local level.

In Estonia, the heritage protection is still mostly top-down model or, in the case of more active stakeholders, a mixed model, but the benefits of more participatory heritage management are not fully recognised. The added value of participation lies not only in preventing or avoiding planning errors, but above all making better use of the strengths of the place, thereby creating synergies for regional development (e.g. Asva). Community spirit is expressed in the choices that motivate local people to appreciate or reconstruct historic sites (e.g. Ennuksemäe and Tiduvere). The values that guide heritage communities are themselves part of their cultural legacy and the bottom-up approach opens up wider opportunities for heritage management, use and preservation. But not all heritage communities have the same level of activity and interest. Younger or dispersed communities, such as suburbs, may have less of a sense of belonging and their relationship with local heritage may be more distant (e.g. Iru). In such cases, the implementation of a top-down management model is essential. Without collaboration, contributions from researchers, and local engagement, cultural heritage can lose its resonance with stakeholders beyond the professional communities.

Lastly, when local people, enthusiasts and/or local authorities sense that they are part of a heritage community, they feel more responsible for the sites. Emotional attachment to a locus also creates a sense of ownership, which makes stakeholders act towards its preservation. Returning to the ideals stated in the Faro Convention, we can see a clear community input in the case of archaeological and dark heritage sites in Estonia. Although the role and involvement of communities varies, there are many people who are committed to caring for historic places. To quote one interviewee, the current state of community-based and participatory heritage management in Estonia could be summarised as follows: ‘no one is responsible, but in fact everyone is responsible’ (Interview 9, 11.01.2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all people who have contributed to the study taking part in the interviews. We would like to thank Tõnno Jonuks who has given us useful feedback on the paper, Aive Kaldra and Helena Kaldre who have helped with the interviews and data management. We would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on an earlier draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tuuli Kurisoo

Tuuli Kurisoo, PhD, is a researcher at Tallinn University, Estonia. Her research concerns the contribution of the metal detecting community to the archaeological heritage in Estonia. She has published several papers giving an overview of the recent detector finds and discussing the impact of this hobby on management and preservation of the archaeological heritage. She is also interested in promoting archaeology and participatory heritage management.

Anu Lillak

Anu Lillak is a PhD student at the University of Tartu, Estonia. Her PhD research is focused on Iron Age commingled and fragmented human remains. She currently also works at the National Heritage Board of Estonia and has published papers on heritage management. In her heritage related research she is interested in community archaeology, community-led heritage management and efficient methods for promoting heritage.

Andres Rõigas

Andres Rõigas is a researcher in cultural entrepreneurship at the University of Tartu’s Viljandi Culture Academy in Estonia. His research areas are business and economic development, cultural economics, and the development of rural communities. His earlier work experience is related to both state and local government institutions, allowing him to focus on public sector issues, project-based activities, and regional politics.

Küllike Tint

Küllike Tint is an archaeologist at Tallinn City Museum, working mainly on medieval and post-medieval finds. She is also interested in public and community archaeology, especially in finding new ways to present and promote archaeology.

Notes

1. All of the villages in question are sparsely populated (less than 100 inhabitants). Even though the communities consist of people from different settlements, describing them more in detail would have compromised their anonymity. Instead, we focused on their interests, motives, and relation to their heritage.

2. The Faro Convention was ratified in Estonia on 26 February 2021, with Government Order No. 92 https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/202032021004?fbclid=IwAR0HoRDiYt43rCQxAqJXPLjW4uZ8hIvzJfoR-_lAqNDg_vrbMZhSfg7sgw4.

3. The Viking Age theme was inspired by the archaeological discovery of the Salme ship burials (Peets et al. Citation2013) and respective research (Saaremaa, Citationn.d.) resulting in a Viking exhibition in Saaremaa Museum in 2021.

References

- Bardone, E., K. Grünberg, M. Kõivupuu, H. Kästik, and H. Sooväli-Sepping. 2020. “The Role of Communities in the Politics of Cultural Heritage: Examples from Estonia.” In Approaches to Culture Theory, edited by A. Kannike, K. Kuutma, and K. Lindström. and A. Riistan, 252–278. Tartu: Tartu University Press.

- Cerreta, M., and E. Giovene di Girasole. 2020. “Towards Heritage Community Assessment: Indicators Proposal for the Self-Evaluation in Faro Convention Network Process.” Sustainability 12 (23): 9862. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239862.

- Colomer, L.2021. “Exploring Participatory Heritage Governance After the EU Faro Convention.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development

- Council of Europe. 2005. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society [“The Faro Convention”], European Treaty Series 199. Strasbourg. https://rm.coe.int/1680083746.

- Crooke, E. 2010. “The Politics of Community Heritage: Motivations, Authority and Control.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441705.

- Enqvist, J. 2014. “The New Heritage: A Missing Link Between Finnish Archaeology and Contemporary Society?” Fennoscandia Archaeologica 31:101–123.

- Florjanowicz, P. 2016. “From Valletta to Faro with a Stopover in Brussels. International Legal and Policy Background for Archaeology or Simply the Understanding of Heritage at the European Level.” In When Valletta Meets Faro. The Reality of European Archaeology in the 21st Century, edited by P. Florjanowicz, 25–32. Vol. 11. Hungary: Europae Archaeologia Consilium (EAC), Association Internationale sans But Lucratif (AISBL).

- Fredheim, L. H. 2019. “Sustaining public agency in caring for heritage: critical perspectives on participation through co-design.” PhD diss., University of York.

- Goulding, C., and D. Domic. 2009. “Heritage, Identity and Ideological Manipulation: The Case of Croatia.” Annals of Tourism Research 33 (1): 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.10.004.

- Grimwade, G., and B. Carter. 2000. “Managing Small Heritage Sites with Interpretation and Community Involvement.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 6 (1): 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/135272500363724.

- Haav, M. 2016. “Metsavendade punker hävis taas tuleleekides [The forest brothers’ bunker was destroyed again in flames].” Sakala, October 31. Accessed June 16, 2023. https://sakala.postimees.ee/3892341/metsavendade-punker-havis-taas-tuleleekides.

- Heritage Conservation Act 2019, “Signed 20 February 2019. Riigi Teataja I, 2019 No. 13.” https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/504062019001/consolide.

- Hester, R. 1993. “Sacred Spaces and Everyday Life: A Return to Manteo, North Carolina.” In Dwelling, Seeing and Designing: Toward a Phenomenological Ecology, edited by D. Seamon, 271–297. NY: State University of New York Press.

- Indreko, R. 1939. “Asva linnus-asula [Asva hill fort-settlement].” In Muistse Eesti Linnused, edited by H. Moora, 17–52. Tartu: Õpetatud Eesti Selts.

- Kaasik, P., M. Kiudsoo, P. Kuusk, M. Herem, and Ü. Kurik. 2020. Metsavennad. Arheoloogid ja ajaloolased metsavendade jälgedel [Forest Brothers. Archaeologists and Historians on the Footsteps of the Forest Brothers]. Tallinn: OÜ Äripäev.

- Kadakas, U. 2020. “Archaeological Heritage and the New Heritage Conservation Act: A Short Overview About the Development of Government Regulation.” Archaeological Fieldwork in Estonia 2019:243–252.

- Kiudsoo, M., M. Andreller, and P. Kuusk. 2015. “Preliminary Results of Archaeological Investigations of the Bunker of the Forest Brothers in Harju County.” Archaeological Fieldwork in Estonia 2014:211–214.

- Konsa, K. 2019. “Developments in Approaches to Heritage in Estonia: Monuments, Values, and People.” Baltic Journal of Art History 18 (1): 181–208. https://doi.org/10.12697/BJAH.2019.18.05.

- Kraut, A., and Ü. Tamla. 2007. “2006. aasta arheoloogiliste välitööde tulemusi. [Results of archaeological fieldwork in 2006].” Archaeological Fieldwork in Estonia 2006:7–30.

- Kraut, A., and Ü. Tamla. 2008. “2007. Aasta Arheoloogiliste Välitööde Olulisemad Tulemused. [Major Results of Archaeological Fieldwork in 2007].” Archaeological Fieldwork in Estonia 2007:5–26.

- Lang, V.2007. “The Bronze and Early Iron Ages in Estonia.” In Estonian Archaeology. Vol. 3. Tartu: Tartu University Press.

- Lang, V. 2020. “Pronksiaeg ja eelrooma rauaaeg (1750 eKr–50 pKr).” In [Bronze Age and Pre-Roman Iron Age (1750 BC–50 AD)]. In Eesti Ajalugu I, edited by V. Lang, 155–230. Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli ajaloo ja arheoloogia instituut.

- Latham, K. F. 2013. “Numinous Experiences With Museum Objects.” Visitor Studies 16 (1): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10645578.2013.767728.

- Macdonald, S. 2015. “Is ‘Difficult Heritage’still ‘Difficult’? Why Public Acknowledgment of Past Perpetration May No Longer Be so Unsettling to Collective Identities.” Museum International 67 (1–4): 6–22.

- McKenzie, B. 2020. “Heritage Defined and Maintained Through Conflict Re-Enactments: The Estonian Museum of Occupations and the Forest Brothers Bunker.” In Creating Heritage for Tourism, edited by C. Palmer and J. Tivers, 39–49. London: Routledge.

- Mertelsmann, O. 2020. “The Armed Anti-Soviet Resistance in Estonia After 1944.” In Violent Resistance. From the Baltics to Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe 1944-1956, edited by M. Gehler and D. Schriffl, 28–51. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh.

- Mertelsmann, O., and A. Rahi-Tamm. 2009. “Soviet mass violence in Estonia revisited.” Journal of Genocide Research 11 (2–3): 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520903119001.

- Meskell, L. 2002. “Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology.” Anthropological Quarterly 75 (3): 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2002.0050.

- Mydland, L., and W. Grahn. 2012. “Identifying Heritage Values in Local Communities.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 18 (6): 564–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.619554.

- Peets, J., R. Allmäe, L. Maldre, R. Saage, T. Tomek, and L. Lõugas. 2013. “Research Results of the Salme Ship Burials in 2011–2012.” Archaeological Fieldwork in Estonia 2012:43–60.

- Perkin, C. 2010. “Beyond the Rhetoric: Negotiating the Politics and Realising the Potential of Community-Driven Heritage Engagement.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 107–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441812.

- Rahi-Tamm, A. 2017. “Stalinist Repression in Estonia: State of the Research and Open Questions.” Croatian Political Science Review 54 (1−2): 32–51.

- Rauk, A. 2020. “’Raha matmine punkrisse’ [Burying money in a bunker].” Sakala, January 9. Accessed June 16, 2023. https://sakala.postimees.ee/6867553/raha-matmine-punkrisse.

- Remmel, M.-A. 2005. “Iru Ämm ja Linda kivi.” Eesti Loodus 2005 (6): 38–40.

- Saaremaa, V. n.d. “’Why was 2021 year of the Vikings?’ Visit Saaremaa.” Accessed June 16, 2023. https://visitsaaremaa.ee/en/year-of-vikings-2021/.

- Shipley, R., and M. Snyder. 2013. “The Role of Heritage Conservation Districts in Achieving Community Economic Development Goals.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 19 (3): 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2012.660886.

- Soininen, T.-L. 2017. “Adopt-A-Monument: Preserving Archaeological Heritage for the People, with the People.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 4 (2): 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2017.1293926.

- Sperling, U., V. Lang, K. Paavel, and A. Kimber. 2015. “Neue Ausgrabungen in der Bronzezeitsiedlung von Asva - vorläufiger Untersuchungsstand und weitere Ergebnisse.” Archeological Fieldwork in Estonia 2014:51–64.

- Talvik, J. 2020. “Punker aitas ajalugu tunnetada [Bunker helped experiencing the history].” Sakala, January 16. Accessed June 16, 2023. https://sakala.postimees.ee/6873477/punker-aitaks-ajalugu-tunnetada.

- Thomas, S., V.-P. Herva, O. Seitsonen, and E. Koskinen-Kivisto. 2019. “Dark Heritage.” In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by C. Smith, 1–11. New York: Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_3197-1.

- Tolia-Kelly, D. P., E. Waterton, and S. Watson. 2017. Introduction: Heritage, Affect and Emotion. In Heritage, Affect and Emotion, edited by D. P. Tolia-Kelly, E. Waterton and S. Watson. 1–11. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Tõnisson, E. 2008a. “Asva Linnamäe põld.” In Eesti Muinaslinnad [Prehistoric strongholds of Estonia]. Muinasaja Teadus 20, edited by A. Mäesalu and H. Valk, 250–251. Tartu–Tallinn: Greif OÜ.

- Tõnisson, E. 2008b. “Iru Linnapära.” In Eesti Muinaslinnad [Prehistoric strongholds of Estonia]. Muinasaja Teadus 20, edited by A. Mäesalu and H. Valk, 187–189. Tartu–Tallinn: Greif OÜ.

- Topouzova, L. 2019. “Remembering Belene Island: Commemorating a Site of Violence.” In The Routledge Handbook of Memory and Place, edited by S. De Nardi, H. Orange, S. High, and E. Koskinen-Koivisto, 77–88. New York: Routledge.

- Vaeliverronen, L., Z. Kruzmetra, A. Livina, and I. Grinfilde. 2017. “Engagement of Local Communities in Conservation of Cultural Heritage in Depopulated Rural Areas in Latvia.” International Journal of Cultural Heritage 2:13–21.

- Vassar, A. 1939. “Iru Linnapära.” In Muistse Eesti Linnused, edited by H. Moora, 53–100. Tartu: Õpetatud Eesti Selts.

- Virkkunen, J. 1999. “The Politics of Identity: Ethnicity, Minority and Nationalism in Soviet Estonia.” GeoJournal 48 (2): 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007099905702.

- Wang, Y. 2023. “Exploring Multiple Dimensions of Attachment to Historic Urban Places, a Case Study of Edinburgh, Scotland.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 29 (5): 428–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2023.2193817.

- Waterton, E., and L. Smith. 2010. “The Recognition and Misrecognition of Community Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441671.

- Watson, S., and E. Waterton. 2010. “Heritage and community engagement.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441655.

- Zagato, L. 2015. “The Notion of “Heritage Community” in the Council of Europe’s Faro Convention. Its Impact on the European Legal Framework.” In Between Imagined Communities of Practice: Participation, Territory and the Making of Heritage, edited by N. Adell, R. F. Bendix, C. Bortolotto, and M. Tauschek, 141–168. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press.

- Zhang, L. 2022. “Towards a Better Approach: A Critical Analysis of Heritage Preservation Practices.” Open Journal of Social Sciences 10 (05): 43–54. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2022.105005

Interviews

- Interview 1. Ennuksemäe, Community of Engagement and Local People, Group Interview, October 26, 2022a.

- Interview 2. Ennuksemäe, Tarvastu Former Local Governance, Group Interview, October 26, 2022b.

- Interview 3. Asva, Saare local governance, group interview, December 22, 2022c.

- Interview 4. Asva, Community of Engagement, December 22, 2022d.

- Interview 5. Asva, Local People, Group Interview, December 29, 2022e.

- Interview 6. Asva, Saaremaa Museum, December 29, 2022f.

- Interview 7. Tiduvere, Community of Engagement, January 6, 2023a.

- Interview 8. Tiduvere, community of engagement, group interview, January 10, 2023b.

- Interview 9. Tiduvere, Community of Engagement, January 11, 2023c.

- Interview 10. Tiduvere, Local People, Group Interview, January 15, 2023d.

- Interview 11. Iru Ämm Club, local people, group interview, January 11, 2023e.

- Interview 12. Iru local, January 13, 2023f.